Abstract

The olfactory system is responsible for the reception, integration and interpretation of odors. However, in the last years, it has been discovered that the olfactory perception of food can rapidly modulate the activity of hypothalamic neurons involved in the regulation of energy balance. Conversely, the hormonal signals derived from changes in the metabolic status of the body can also change the sensitivity of the olfactory system, suggesting that the bidirectional relationship established between the olfactory and the hypothalamic systems is key for the maintenance of metabolic homeostasis. In the first part of this review, we describe the possible mechanisms and anatomical pathways involved in the modulation of energy balance regulated by the olfactory system. Hence, we propose a model to explain its implication in the maintenance of the metabolic homeostasis of the organism. In the second part, we discuss how the olfactory system could be involved in the development of metabolic diseases such as obesity and type two diabetes and, finally, we propose the use of intranasal therapies aimed to regulate and improve the activity of the olfactory system that in turn will be able to control the neuronal activity of hypothalamic centers to prevent or ameliorate metabolic diseases.

Keywords: Olfactory system, Metabolism, Hypothalamus, Obesity, Diabetes and intranasal therapies

Introduction

Odor reception is an omnipresent primitive sensory mechanism in animals that allows the perception of volatile chemicals known as odorants. This system conveys information regarding the presence of familiar and unknown odors, conspecifics, potential mates, mother–offspring recognition, food sources, predators, and prey (Laska and Hudson 1993).

The central odor processing is achieved through a complex neuroanatomical network that includes the olfactory receptors in the nose, olfactory regions in the brain, higher integration cortexes and several hypothalamic nuclei (Nausbaum 1999; Klingler 2017; Meissner-Bernard et al. 2019; Nagayama et al. 2014).

In this review we describe how up-stream olfactory inputs affect hypothalamic activity and the regulatory mechanisms aimed to maintain energetic homeostasis. First, we discuss the neuroanatomy of the olfactory system to understand how odor information is processed and how it is able to reach the hypothalamus. Next, we analyze how the metabolic status of the body modulates olfaction, describing that the integration of humoral metabolic signals can also takes place in the olfactory system to adjust its olfactory capacity.

In the second part, we describe the influence of the olfactory system on hypothalamic activity, mentioning that the activation of the olfactory system promotes neuronal responses in several nuclei of the hypothalamus. Also, we describe the olfactory alterations found in metabolic diseases like obesity and type two diabetes highlighting the relevance of the olfactory system for the maintenance of metabolic balance. Finally, we discuss how the olfactory-hypothalamic relationship constitutes a potential target of study to develop noninvasive therapies obesity and diabetes, hence, enlisting the remaining questions that this research should answer to completely understand the exact mechanisms involved in the olfactory regulation of hypothalamic activity and to use this information for the development of therapies that target the interaction between both circuits.

Brief Neuroanatomy of the Olfactory System

There are important variations in the chemical structure, concentrations, and combinations of the odors able to activate specific mechanisms underlying odor detection and discrimination, which means that every element in nature has its own odorant stamp (Zou et al. 2009; Croy et al. 2015).

In mammals, the nose is the main olfactory organ, it consists of multiple olfactory subsystems including the main olfactory epithelium (OE) and the vomeronasal organ (VNO) (Trotier 2011). The OE has two types of cells: the microvillar cells and the olfactory sensory neurons (OSN), which express more than 1000 G-protein-coupled odor receptors arranged in a topological map (Nagayama et al. 2014). Each OSN responds to a single type of odorant because they only express one type of odorant receptor. Thus, complex odors, composed of more than two odorant molecules activate more than one olfactory neuron.

Olfactory neurons project to the olfactory bulb (OB), which integrates information from the OE and transmits it to other regions in the brain. The OB is organized into strict multiple layers of distinct cell types: juxtaglomerular (JG) cells that include the periglomerular (PG) cells, external tufted (ET) cells and superficial short-axon (sSA) cells, mitral cells, tufted cells, and granule cells (Tan et al. 2010; Kikuta et al. 2013). Both the OE and the OB are the primary olfactory regions.

In the OB, the first synapsis from the OE is established in the glomerular cell layer (GCL), which latter propagates to the cell bodies of tufted cells in the external plexiform layer (EPL) and mitral cells in the mitral cell layer (MCL), then horizontally back-propagates through the secondary dendrites in the EPL (Tan et al. 2010; Kikuta et al. 2013).

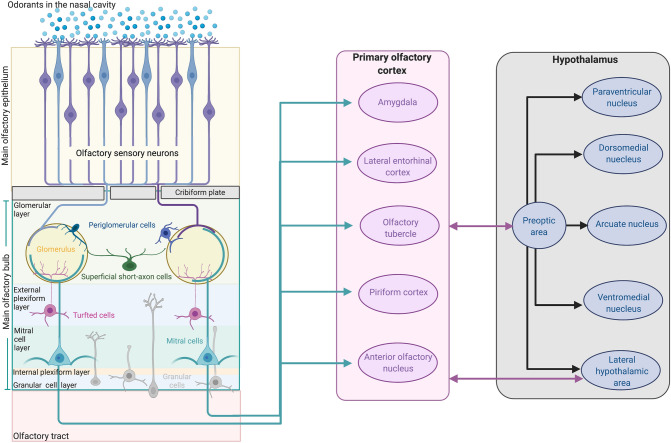

Finally, neurons in the EPL and the MCL send excitatory projections to the different areas of the olfactory cortex via the lateral olfactory tract where olfactory information is integrated (Nagayama et al. 2014; Zhou et al. 2019) (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Neuroanatomy of the olfactory system. Volatile chemicals (odorants) enter the nasal cavity and are detected by olfactory sensory neurons (microvillar cells, blue, and olfactory sensory neurons, purple) in the main olfactory epithelium. Olfactory sensory axons enter the cribriform plate into the glomerular layer of the olfactory bulb where they synapse with periglomerular cells. The signal is propagated to the cell bodies of tufted cells in the external plexiform layer and mitral cells in the mitral cell layer. Finally, the neurons in the external plexiform and mitral layer send excitatory projections to the different areas of the primary olfactory cortex (Amygdala, Lateral entorhinal cortex, Olfactory tubercle, Piriform cortex, Anterior olfactory nucleus), via the lateral olfactory tract where the integration of olfactory information takes place. The system is mainly connected with the hypothalamus via poly-synaptic pathways from the olfactory bulb to the preoptic area of the hypothalamus. Other poly-synaptic pathways connecting the olfactory system with the paraventricular nucleus, dorsomedial nucleus, ventromedial nucleus and lateral hypothalamic area have also been described (see the text). Created with BioRender.com

The integration and organization of the olfactory information is quite complex and it implies different integration levels that have already been described in detail (Nausbaum 1999; Klingler 2017; Meissner-Bernard et al. 2019; Nagayama et al. 2014). In the next sections we will discuss the link between the olfactory and the hypothalamic system and its implication for the regulation of energy balance.

Metabolic Status Directly Modulates Olfactory Sensitivity

There is a fair amount of literature stating that the olfactory system is controlled by the metabolic status of the body (Price et al. 1991). The most clear example is that food deprivation can increase the firing rate of the neurons in the OB, increasing its response to food-related odors; this increase in activity is immediately damped after food intake (Apelbaum and Chaput 2003; Badonnel et al. 2012; Palouzier-Paulignan et al. 2012).

Many neuropeptides and metabolic hormones such as Gonadotropin-Releasing Hormone (GnRH), Neuronal Peptide Y (NPY), insulin, leptin, adiponectin and orexins are known to modulate the sensitivity of olfactory sensory neurons in different species (Martin et al. 2009).

Both the OE and OB express leptin (Ob-R), insulin (IR), ghrelin and adiponectin receptors (Baskin et al. 1983; Elmquist et al. 1998; Hass et al. 2008; Miranda-Martínez et al. 2017), suggesting that hormonal signals not only regulate energy balance by signaling into hypothalamic regions but may also control metabolism through direct modulation of olfactory perception (Riera and Dillin 2016).

On the other hand, insulin also modulates most steps of odor detection; at the level of the olfactory mucosa, and the increase of insulin levels in the OB reduces food odor-induced sniffing behavior in rats and olfactory sensitivity in humans (Aimé et al. 2012; Brünner et al. 2013).

The OB has the highest concentrations of insulin and insulin receptors (IR) in the brain (Edwin Thanarajah et al. 2019; Kleinridders et al. 2014). The loss of one allele of IR was reported to modify the electrical phenotype of mitral cells, without changing olfactory ability (Das et al. 2005). Ablation of the insulin like growth factor receptor (IGF1R) in OSNs enhances olfactory performance and increases adiposity (Riera et al. 2017). Demonstrating that insulin reduces olfactory function.

Another peptide crucial for energetic homeostasis is leptin. This hormone is produced by adipocytes in proportion to the fat content (Houseknecht et al. 1998; Mantzoros 1999; Friedman 2002; Pinto et al. 2004), and has a role in various physiological functions, including food intake, body weight regulation, reproduction, bone formation, and angiogenesis; these actions appear to be mediated through signaling into hypothalamic regions (Coppari et al. 2005; Pandit et al. 2017; Kwon et al. 2016).

Leptin exerts its metabolic actions through the leptin Ob-R receptor (Meister 2000; Meister and Håkansson 2001; Gorska et al. 2010; Liu et al. 2007). As previously mentioned the olfactory system expression of these receptors have been reported in the olfactory mucosa, OB, piriform cortex and entorhinal cortex, and there is also local synthesis of leptin in the olfactory mucosa (Caillol et al. 2003; Baly et al. 2007; Shioda et al. 1998). Similar to insulin, leptin has an inhibitory role in olfactory perception. Leptin administration in the CNS reduces food odor exploration (Prud’homme et al. 2009) and decreased the performance in odor discrimination tasks associated with decreased mitral/tufted cells firing (Sun et al. 2019). Savigner et al., demonstrated that leptin induces changes in olfactory sensitivity (Savigner et al. 2009), since ob/ob leptin deficient mice are hyper-osmic and obese, and leptin replacement in these animals decreases olfactory perception and food intake (Getchell et al. 2006).

Adiponectin is an adipokine almost exclusively secreted by the white adipose tissue. This hormone has several pleiotropic effects, it regulates lipid and glucose metabolism, increases insulin sensitivity, modulates immune activation in different immune cells and it has antioxidant properties. Adiponectin secretion is inversely correlated with BMI meaning that obese and diabetic patients with increased adiposity present hypoadiponectinemia (Mojiminiyi et al. 2005). The effects of adiponectin are mediated by the adiponectin receptors 1 and 2 (AdipoR1 and AipoR2) and are generally expressed simultaneously, these receptors are highly expressed in the brain (Yamauchi et al. 2007). There is a third cell surface molecule that binds to adiponectin, T-cadherin that is mainly expressed in endothelial cells (Akingbemi 2013).

AdipoR1 and AdipoR2 are expressed in the sensory neurons of the OE and in the OB (Hass et al. 2008; Miranda-Martínez et al. 2017). Furthermore, AdipoR1 is expressed in the OE (Prud’homme et al. 2009) and the septal organ, but not in the vomeronasal organ, which specializes the perception of social odors, suggesting that adiponectin signaling in the olfactory system is mainly involved in the perception of food odors (Hass et al. 2008). In mice, adiponectin increases the activation of juxtaglomerular interneurons and enhances the electrical response in the olfactory epithelium to odor stimulation (Loch et al. 2013); although the exact effects in olfactory perception of this adipokine are unknown.

On the other hand, ghrelin receptors (GHSR-1a) are also expressed in the glomerular, mitral and granular cell layers in the OB; intraperitoneal (i.p.) administration of ghrelin increases the olfactory detection of food and exploratory sniffing in both rodents and humans (Loch et al. 2015; Tong et al. 2011).

Interestingly, there is evidence that in the postprandial phase an important elimination of new cells in the granular cell layer of the OB takes place (Yamaguchi et al. 2013; Yokoyama et al. 2011; Komano-Inoue et al. 2014), suggesting that the metabolic status might not only be involved in the modulation of neuronal excitability but also has a direct influence in the organization of the olfactory neuronal circuits and in olfactory sensitivity.

Glucose and lipids are also sensed in the olfactory circuits, changes in hepatoportal glucose levels result in the neuronal activation of several areas in the brain including the OB (Delaere et al. 2013). Similar to other tissues, the OE and the OB express glucose transporters GLUT-1 and GLUT-2 (Hichami et al. 2007; Leloup et al. 1994) and GLUT-1 expression levels in the OB are determined by both metabolic status and the performance of olfactory tasks (Hichami et al. 2007; Soria-Gomez et al. 2014). Furthermore, sodium-coupled glucose transporters 1 (SGLT1) and insulin dependent glucose transporters 4 (GLUT4) are also expressed in the OB (Aimé et al. 2014; El Messari et al. 1998).

Furthermore, mitral cells in the OB increase their firing rate in response to changes in glucose concentrations (Tucker et al. 2013), suggesting that this region might have glucose sensor properties. In contrast, the lack of glucose and lipid sensing mice null for the voltage-gated potassium channel Kv1.3 leads to hyper-osmia, suggesting that sensing low reservoirs levels enhance the olfactory perception, and that this is interpreted as a signal to seek for food sources. Although this data should be taken with great reserve since Fadool et al., also reports structural changes in the glomerular portion of the OB in the KO-Kv1.3 mice (Fadool et al. 2011).

Besides from the evidence demonstrating that the metabolic status of the body modulates olfactory responses to odors, this is not a one-way street, and olfactory activation can also promote neuronal responses in the hypothalamus.

The Olfactory System Modulates Neuronal Hypothalamic Activity

One of the under-studied aspects of olfactory systems is the control of hypothalamic outputs. The most studied neuroanatomical connection between the olfactory system and the hypothalamus is the connection of the olfactory cortex with the hypothalamic preoptic area. Via this pathway, olfactory cues like pheromones can control sexual behavior, female ovulation inter-male aggression, among other behaviors (Yoon et al. 2005; Gascuel et al. 2012; Edwards et al. 1993; Guillot and Chapouthier 1996).

In addition, the autonomic functions that regulate energy expenditure are also modulated by olfactory signals. For example, a series of experiments using grapefruit oil, which induces olfactory stimulation, significantly increases the sympathetic output to the brown interscapular and white epididymal adipose tissue, elevates renal sympathetic nerve activity and blood pressure (Niijima and Nagai 2003; Shen et al. 2005; Tanida et al. 2005), suggesting that the olfactory areas of the brain modulate the activity of hypothalamic nuclei involved in energy balance.

Different poly-synaptic pathways connect the olfactory system with the hypothalamus. Tracing studies performed by injecting the multi-synaptic neuronal tracer wheat germ agglutinin-horseradish peroxidase (WGA-HRP) in the lateral hypothalamus (LH), showed labeled cells in the anterior olfactory nucleus, the piriform cortex, the olfactory tubercle, and the anterior cortical nucleus of the amygdala. Furthermore electrical stimulation of the OB or the olfactory cortex induces neuronal responses of the LH (Gascuel et al. 2012; Velozo and Almli 1992; Anand and Brobeck 1951; Price et al. 1991).

A study by Murata et al., demonstrated that GABAergic neurons in the olfactory peduncle project to the LH, suggesting that this pathway could be inhibiting processes like food intake and alertness (Murata et al. 2019). In addition, Kondon et al., observed that CRH neurons in the paraventricular nucleus (PVN) receive innervation from multiple olfactory cortical areas, and that this neuroanatomical connection regulates CRH production in response to predator odors (Kondoh et al. 2016).

One of the most convincing evidence regarding the influence of the olfactory system in hypothalamic neuronal activity was performed by Chen et al., who demonstrated that the olfactory detection of food rapidly modulates the neuronal activity of the hypothalamic arcuate nucleus (ARC) (Chen et al. 2015), a nucleus that senses blood borne metabolic cues (Cone et al. 2001). In this study the sole olfactory perception of food significantly increased the firing rate in the proopiomelanocortin (POMC) neurons, a neuronal population known to inhibit food intake and increase energy expenditure thought the mobilization of metabolic reservoirs and activation of brown adipose tissue thermogenesis (Coll et al. 2004). In contrast, decreased the neuronal firing rate of the orexigenic neurons expressing agouti related peptide (AgRP) in the ARC, which are antagonists to POMC (Chen et al. 2015). These data suggest that the communication between the olfactory system can modulate the neuronal activity in the hypothalamus involved in food intake and energy expenditure.

Olfactory perception can also modulate metabolic health, since anosmic mice without either OE receptor cells or OB are resistant to diet-induced obesity and exhibit lower body weight gain, decreased blood glucose levels, increased locomotor activity, heart rate and body temperature (Getchell et al. 2006; Chen et al. 2015; Riera et al. 2017). These data suggest that the olfactory system can regulate the hypothalamic neurons controlling endocrine and autonomic functions not only involved in food intake but also in energy expenditure.

In the next section we discuss how olfactory function becomes altered in metabolic diseases, to further suggest the possibility of intervening this system to ameliorate the metabolic impairments observed in diseases like obesity and diabetes.

Olfactory Sensitivity in Obesity and Diabetes

Altered odor sensitivity has been reported in disorders such as anorexia, bulimia, obesity and diabetes (Enck et al. 2014). As previously mentioned, there is compelling evidence demonstrating a bidirectional relationship between the olfactory and the metabolic system and that this interaction regulates the metabolic balance of the body (Julliard et al. 2017; Soria-Gomez et al. 2014).

The relationship between olfactory sensitivity and body mass index (BMI) is controversial, as both negative and positive associations have been reported (Peng et al. 2019). For example, a study comparing the BMI scores in patients with olfactory dysfunction shows a significant decrease in the olfactory function of subjects with high BMI (Patel et al. 2015). Furthermore, a gene methylation analysis of 474 individuals showed that BMI and waist circumference were associated with 13 CpG sites at olfactory genes including the olfactory receptors OR4D2, OR51A7, OR2T34 and ORDY1, and downstream signaling molecules that regulate odor detection such as SLC8A1, ANO2 and CAMK2D (Ramos-Lopez et al. 2019), demonstrating that obesity induces epigenetic changes in olfactory related genes, that could impair olfactory reception in the OE. Other studies have also determined that obese individuals present poor olfactory identification and discrimination (Fernandez-Garcia et al. 2017; Skrandies and Zschieschang 2015; Pastor et al. 2016).

In contrast, Jacobson et al., showed a positive correlation between greater BMIs and the activation of the primary olfactory regions (Jacobson et al. 2019). Another study demonstrated that obese patients presented increased levels of sensitivity and preference for odors associated with palatable and highly caloric food (Stafford and Whittle 2015). In addition, the hippocampus of obese individuals is significantly more activated after the exposure to food-related odors, suggesting that processing of feeding related odors differs in these subjects and may be part of what causes overeating (Stafford and Whittle 2015). Interestingly, Fardone et al., demonstrated a differential neuronal activation in the juxtaglomerular cells in mice fed a HFD (Fardone et al. 2019), suggesting that only a particular set of neurons are activated by food-related odors, if these glomerular cells are those responding to odorants from energy dense foods remains unknown.

In animal models, obesity-prone rats present decrease odor thresholds, meaning higher olfactory sensitivity, but poor olfactory memory and learning (Lacroix et al. 2015). Furthermore, ob/ob and db/db mice, as well as Zucker rats, present a better performance in olfactory tests and increased food‐seeking behaviors in response to food-related cues (Thanos et al. 2013; Badonnel et al. 2014; Getchell et al. 2006); this is related to hyperactivation of the OB, since its gamma range waves present higher frequencies and the beta activity was longer and stronger in ob/ob mice (Chelminski et al. 2017).

The hypothesis that metabolic health is determined by the OB is supported by bulbectomy studies in rodents showing an increase in the total amount of food intake and meal frequency (Meguid et al. 1993; Miro et al. 1980, 1982). Furthermore, mice with selective ablation of mature sensory neurons (OSN) are resistant to DIO (Fadool et al. 2011; Chelminski et al. 2017; Riera et al. 2017).

These studies suggest that initially a HFD might increase olfactory perception, without being able to inhibit food intake (Fig. 2a). The main complication with human studies and its interpretation, is that many obese patients also present other comorbidities such as vascular diseases and type 2 diabetes (T2D).

Fig. 2.

Olfactory-hypothalamic axis role in metabolic balance. a Food odors are perceived through the sensory neurons in the olfactory epithelium (OE) which project to the olfactory bulb (OB). Here the mitral (black) and tufted (pink) cells send their projections to the anterior olfactory nucleus (AON), the olfactory tubercle (OT) and piriform cortex (PC), and to other parts of the olfactory cortex, in this region the olfactory information is processed for odor detection, discrimination, learning and recalling, these processes also include other cortexes and the hippocampus (not shown here). In a separated pathway, many regions in the olfactory cortex (see text) send axonal projections to the preoptic (POA) and the lateral (LH) areas of the hypothalamus, that in turn establish connections with nuclei involved in the regulation of food intake and energy balance, like the dorsomedial hypothalamus, the paraventricular nucleus, the ventromedial hypothalamus and the arcuate nucleus (ARC). Hypothetically, olfactory information could reach the ARC, where food perception activates the POMC anorexigenic neurons to reduce food intake and increase energy expenditure, and at the same time the olfactory pathway would also inhibit the orexigenic AgRP/NPY neurons. Peripheral hormones like insulin and leptin, are known signals that activate POMC neurons in hypothalamus thus inhibiting food intake and increasing energy expenditure, and in the olfactory system it is known that these hormones are able to suppress olfactory sensitivity. The pathway activated when the individuals have a normal weight is represented in blue and its alteration in obesity is represented in faded red, in which hormones like insulin and leptin do not exert its actions nor in the olfactory system neither in the ARC thus the olfactory perception remains hyperactivated and the ARC circuits are unable to suppress food nor to elicit energy expenditure. b Hypothetical model of how the “olfactory-hypothalamic axis” could be intervened intranasally through the direct activation or desensitization of the olfactory system to induce the activation of neurons in the ARC that inhibit food intake and promote the activation of the autonomic mechanisms involved in the increase of energy expenditure. Created with BioRender.com

The relationship between T2D and olfactory dysfunction has also been described. Diabetic patients show low scores in odor identification and discrimination related with both macro and microvascular impairments in the olfactory system (Weinstock et al. 1993; Zaghloul et al. 2018; Hassing et al. 2004; Watson and Craft 2004). In a cross-sectional study, insulin dependent diabetic subjects presented higher prevalence of perceiving phantom odors, in addition the patients with more aggressive treatments were also hyposmic or anosmic (Chan et al. 2017).

Impaired olfactory ability in diabetic subjects has been associated with neuropathic pain and retinopathy, suggesting that the olfactory screening can be an early predictor of microvascular complications of diabetes (Brady et al. 2013; Gouveri et al. 2014). However, other studies did not find olfactory impairment in diabetic individuals with or without micro and macroangiopathy (Naka et al. 2010).

In T2D rodent models, olfactory performance is impaired and is associated with decreased IRS phosphorylation in the main olfactory bulb and piriform cortex (Rivière et al. 2016; Lietzau et al. 2018).

The proposed mechanisms involved in the olfactory dysfunction in T2D include macro and microvascular causes, olfactory nerve damage, central insulin resistance and low-grade inflammation may play a key role in olfactory modulation (Zaghloul et al. 2018). Recently, our group demonstrated that T2D rats present olfactory dysfunction associated with IL-1β and miR-146a overexpression in the OB, suggesting the upregulation of inflammatory mechanisms (Jiménez et al. 2020).

IR is also expressed in the OE (Lacroix et al. 2008; Marks et al. 2009), and its expression is decreased in the olfactory mucosa and OB of obese rats (Lacroix et al. 2015). Furthermore, olfactory dysfunction was associated with insulin resistance in humans (Palouzier-Paulignan et al. 2012; Min and Min 2018).

The previous information highlights the relevance of the olfactory system in the metabolic balance and metabolic diseases, therefore, the development of strategies aimed to modulate the olfactory function should be considered to improve the treatment of diseases such as obesity and diabetes.

Central Insulin and Leptin Resistance

We have summarized how the olfactory-hypothalamic bidirectional interactions may contribute to the regulation of energy intake and expenditure, and that the olfactory system is a key player for the development of metabolic diseases. This suggests that the modulation of the olfactory-hypothalamic axis might be an important new target area to develop noninvasive therapies aimed to prevent/revert the metabolic impairments resulting from obesity or diabetes.

One of the main characteristics of obesity and T2D are insulin and leptin resistance, which involve an impairment in the capacity of these two hormones to exert their biological effects.

Insulin resistance is a state in which insulin dependent tissues increase their response threshold, thus they require increased concentrations of this hormone to achieve the biological effects normally elicited by lower concentrations.

Impairments in the IR intracellular cascade are believed to be the origin of peripheral insulin resistance. The IR is part of the tyrosine kinase superfamily, following activation its kinase phosphorylates tyrosine residues creating binding sites for signaling protein partners. For more detailed reviews see refs (Taniguchi et al. 2006; White 2003). Most of the physiological effects of the IR are mediated through the activation of IRS-1 and IRS-2 dependent pathways, linking the signaling cascades of the InsR to other pathways such as the cytokine receptors and TNF-α receptors, whose intracellular pathways are well known negative regulators of IRS (Greene et al. 2010).

The metabolic impairments involved in insulin resistance are not exclusive to peripheral organs, this is also observed in the brain. There are two hypotheses regarding the mechanisms of insulin resistance in the brain. The first one being due to an impaired transport into the brain (Banks et al. 2012; Chen et al. 2017; Urayama and Banks 2008) and the other includes decreased basal activation of IR due to reduced insulin binding (Rivera et al. 2005), increased serine phosphorylation of IRS-1 and reduced levels of PI3K (Talbot et al. 2012; Moloney et al. 2010; Liu et al. 2011) both mechanisms imply that the effects of insulin in the CNS including the hypothalamus are damped.

Obese individuals present hyperleptinaemia and a diminished response to leptin, condition known as leptin resistance (Mazor et al. 2018). The Ob-R is part of the cytokine receptors associated with the Janus kinase 2 (JAK2) (Ihle and Kerr 1995). Upon binding, the Ob-R undergoes a conformational change that activates JAK2, thus phosphorylating tyrosine residues that in turn phosphorylates the signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 (STAT3) promoting its translocation into the nucleus and the transcription of several target genes, including the suppressor of cytokine signaling 3 (SOCS3), that inhibits the Ob-R–JAK2 signaling (Couturier and Jockers 2003).

Importantly, in most cases the impairment in leptin signaling is not related to genetic modifications of this hormone or its receptors, instead, similar to insulin there is an impaired transport into the brain, thus preventing the activation of its corresponding signaling pathways (Banks 2001). Restoring leptin signaling in the brain via intracerebroventricular administration (i.c.v.) reduces food intake, enhances energy expenditure and improves glycemic indexes (Fliedner et al. 2006; Van Heek et al. 1997; Halaas et al. 1997).

In addition, central leptin resistance has been related to the overactivation of Ob-R through the increased activation of SOCS-3 resulting from hyperleptinemia and the mild inflammation caused by obesity (Engin 2017).

On the other hand, there is a direct relationship between hypoadiponectinemia and the development of insulin resistance and diabetes (Mojiminiyi et al. 2005).The intracellular domain of AdipoR1 and AdipoR2 binds an adaptor protein containing pleckstrin homology domain, phosphotyrosine binding domain and leucine zipper motif (APPL1). This adaptor protein mediates the downstream effects of adiponectin via AMPK activation (Zhou et al. 2009; Wen et al. 2010).

There is an important crosstalk between insulin and adiponectin pathways, APPL1 forms a complex with IRS1/2 under basal conditions, thus facilitating its union with the insulin receptor (Ryu et al. 2014). Upon stimulation with either insulin or adiponectin the complex APPL1/IRS1/2 is recruited to the insulin receptor therefore increasing insulin sensitivity (Yamauchi et al. 2007) (Combs et al. 2001; Berg et al. 2001).

I.c.v. adiponectin administration enhances both insulin and leptin intracellular signaling pathways, reduces food intake, and increases the expression of IRS1/2, JAK2 and STAT, furthermore adiponectin depolarizes Ob-R expressing POMC neurons and even potentiates its response to leptin (Sun et al. 2016). Furthermore, in genetically and diet-induced obese mice i.c.v adiponectin enhances glucose tolerance (Koch et al. 2014). It has also been suggested that in obesity adiponectin transport into the brain is also impaired (Kos et al. 2007).

One common trait of the hormonal resistances in the brain is that if administered into the CNS, their biological actions are restored (El-Haschimi et al. 2000; Woods et al. 1979; Brown et al. 2006). This might be because the access of these hormones into the brain is a saturable process, therefore, conditions like hyperinsulinemia and hyperleptinemia impair this mechanism reducing the access into the entire brain (Rhea et al. 2018; Banks 2004; Kos et al. 2007; Banks et al. 1996). In agreement, it has been demonstrated that dextrans of various molecular weights administered intravenously do not access the hypothalamus in mice fed a high fat diet (Dodd et al. 2019).

The fact that i.c.v. administration of insulin or leptin in obesity animal models is able to reduce food intake, and improve blood glycaemia suggests that therapies should aim to restore central levels of these hormones or to mimic their effects (Arase et al. 1988; Rahmouni et al. 2002; Heni et al. 2014).

The Intranasal Pathway and Its Therapeutic Potential

The intranasal pathway (i.n.) is a noninvasive method of drug delivery into the CNS (Hanson et al. 2013). This administration route offers the bypassing of the blood–brain barrier (BBB) and extends drug bioavailability, thus offering a reliable and promising pathway to deliver a wide range of therapeutic agents including small and large molecules, including peptides (Scheibe et al. 2008).

The i.n. administration of drugs allows for a rapidly access into brain tissue via two routes: 1) through direct delivery to regions of the peripheral olfactory system that connect the nasal conduits with the OB and 2) associated with the peripheral trigeminal system which connect to the brainstem and spinal cord (Thorne et al. 2004).

The OB glomerular layer is a highly irrigated network (Chaigneau et al. 2007; Yang et al. 1998) with the presence of fenestrated blood vessels (Ueno et al. 1996). Thus, i.n. administration should represent a good conduit for increasing OB activity and modulating hypothalamic functions (Fig. 2b).

The use of intranasal administrations of hormones has shown metabolic benefits in obese and diabetic patients, and animal models. Obese rats administered intranasally with leptin show decreased food intake and body weight loss (Schulz et al. 2012). These effects are similar to those observed in leptin i.c.v. administrations (El-Haschimi et al. 2000). Importantly, Fliedner et al. showed that i.n. leptin enters several areas in the brain even in hyperleptinemic rats (Fliedner et al. 2006). In addition it significantly attenuates sleep-disordered breathing, improves glucose impairments and decreases bodyweight gain in obese rats (Khafagy et al. 2020; Yuan et al. 2017; Santiago and Hallschmid 2019; Reger and Craft 2006; Schulz et al. 2012; Berger et al. 2019), suggesting that i.n. leptin is metabolically effective in obese animals, This suggests that using the nose-to-brain route bypasses defective leptin transport through the BBB that has been observed in metabolic diseases, thus restoring the central effects of leptin without the need of invasive intracerebral procedures.

Similarly, i.n. insulin administrations have also demonstrated promising therapeutic effects in obese and diabetic patients, decreasing food intake and body weight (Hallschmid et al. 2004; Jauch-Chara et al. 2012; Khafagy et al. 2020; Yuan et al. 2017; Santiago and Hallschmid 2019; Reger and Craft 2006), increasing postprandial energy expenditure and decreasing insulin secretion (Benedict et al. 2011). These effects are similar to those observed with i.c.v. administrations in obese rodents and primates (Woods et al. 1979; Brown et al. 2006).

The improvements in metabolism observed after i.n. administration of hormones could have two possible mechanistic explanations: (1) The direct increase of these hormones in the brain parenchyma including the hypothalamus allows them to access their target areas. (2) Because the OB contains many of the hormone receptors and has the highest transport rate across the blood–brain barrier (BBB) (Banks et al. 1999), signaling to this area activates neurons connecting with the hypothalamus. Even if the hypothalamus presents a certain degree of hormonal resistance, this pathway would be able to activate it because it constitutes a neuronal and not a humoral connection.

As mentioned before there is an important lack of information regarding receptor expression in the olfactory system in obese and diabetic patients. In Table 1, we summarize some of the studies with data regarding the expression of IR and Ob-R, most of which are unchanged, except for the olfactory epithelium that presents a downregulation of the insulin receptor. Interestingly, most of the reports in the hypothalamus show a marked down regulation of the receptors, suggesting that there is a selective resistance to insulin and leptin in this area and that the olfactory areas are not as affected.

Table 1.

Leptin and insulin receptor expression in the brain in obesity models

| Receptor | Species | Tissue | Metabolic condition | Expression | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IR | Sprague–Dawley rats | Olfactory Bulb | Diet-induced obesity | Unchanged | Lacroix et al. (2015) |

| Zucker rat | Hippocampus | Obesity genetic model | Unchanged | Livingston et al. (1993) | |

| Zucker rat | Piriform cortex | Obesity genetic model | Unchanged | Gisslinger et al. (1993) | |

| Zucker rat | Olfactory bulb | Obesity genetic model | Unchanged | McFarlane et al. (1993) | |

| Zucker rat | Brain | Obesity genetic model | Unchanged | Livingston et al. (1993) | |

| Sprague–Dawley rats | Olfactory mucosa and Olfactory bulb | Diet-induced obesity | Down regulated | Lacroix et al. (2015) | |

| Neuroblastoma cell line | Differentiated human neuroblastoma | Leptin pre-treatment | Down regulated | Benomar et al. (2005) | |

| Ob-R | Sprague–Dawley rats | Olfactory bulb Olfactory mucosa | Obesity genetic model | Unchanged | Lacroix et al. (2015) |

| New Zealand Obese mice | Isolated cerebral microvessels | Obesity genetic model | Unchanged | Hileman et al. (2002) | |

| Diet-induced obese mice | Isolated cerebral microvessels | Diet-induced obesity | Unchanged | Hileman et al. (2002) | |

| Long-Evans rats | Hypothalamus | Chronic leptin administration | Down regulated | Martin et al. (2000) | |

| Brown Norway rats | Hypothalamus | Diet-induced Obesity | Down regulated | Wilsey and Scarpace (2004) | |

| Mice | Hypothalamus | Diet-induced Obesity | Down regulated | Zhai et al. (2018) | |

| ob/ob mice | Hypothalamus | Obesity genetic model | Up regulated | Huang et al. (1997) | |

| ob/ob mice | Piriform cortex | Obesity genetic model | Up regulated | Hassall and Hoyle (1997) | |

| ob/ob mice | Olfactory cortex | Obesity genetic model | Up regulated | Huang et al. (1997) | |

| Agouti viable yellow (Avy) mice | Hypothalamic microvessels and astrocytes | Obesity genetic model | Up regulated | Pan et al. (2008) | |

| B6 mice | Hypothalamic microvessels | Diet-induced Obesity | Up regulated | Pan et al. (2008) |

In this sense the effects of intranasal therapies observed on metabolism may imply the stimulation of the olfactory-hypothalamic axis. Therefore, since insulin and leptin decrease olfactory sensitivity this stimulation will ultimately activate an until now unknown pathway that will increase POMC and decrease AgRP neuronal activity. This hypothesis is based on the fact that many of the i.n. administrations of insulin and leptin show decreased food intake, enhancements in postprandial thermogenesis, reduced glucose production and improved insulin sensitivity, all of these functions are modulated by several neuronal types in the ARC especially the POMC and AgRP/NPY, that in obesity and diabetes present a certain degree of insulin and leptin insensitivity, thus these autonomic effects might be promoted by the olfactory system.

As previously mentioned the other possible mechanism through which hormones like insulin and leptin do not exert a biological effect is the downregulation or desensitization of their receptors in different areas of the brain (Chen et al. 2017; Yarchoan and Arnold 2014; De Felice and Ferreira 2014; Zemva and Schubert 2014; Bomfim et al. 2012) suggesting that if the underlying cause of the resistance is due to impairments in the receptors (Table 1), then the use of intranasal hormonal therapies might not show as much benefit as expected, therefore the employment of other peptides or drugs capable to mimic or improve receptor sensitivity could be an alternative option.

A study conducted by Seelke et al., showed that chronic intranasal oxytocin administration reduce fat mass in voles without altering lean mass, (Seelke et al. 2018), this hormone has demonstrated a beneficial effect in olfactory memory and sensitivity (Oettl et al. 2016; Oettl and Kelsch 2018).

On the other hand, the human fibroblast growth factor 1 (FGF1) is a peptide secreted by adipose-derived microvascular endothelial cells (MVECs) with insulin sensitization properties, this peptide has been used to prevent the progression of neurodegenerative diseases in rodents (Lou et al. 2012) the brain damage in stroke models (Cheng et al. 2011; Fan et al. 2019) and its central and peripheral administration confers notable improvements in diabetic mice (Gasser et al. 2017).

The thiazolidinedione (TZD), pioglitazone, is an insulin sensitizing molecule for the management of insulin resistance. Its enhances peripheral insulin sensitivity, and increases plasma adiponectin concentrations (Miyazaki et al. 2004; Miyazaki et al. 2001; Kemnitz et al. 1994; Tozzo et al. 2015) this molecule has also been used intranasally in Alzheimer’s disease (AD) patients, a neurodegenerative disorder associated with impaired brain insulin signaling proving a notable improvement in cognitive function (Jojo et al. 2019; Wong et al. 2020).

These studies suggest that the intranasal use of other molecules in which their receptors do not undergo insensitivity or downregulation in metabolic diseases might be a possible option therapies to enhance hypothalamic activity through modulation of the olfactory-hypothalamic pathway.

Future Directions

Definitely more studies are needed to determine if there is a mechanism that could allow the use of intranasal therapies to ameliorate the metabolic impairments caused by metabolic diseases like obesity and diabetes that nowadays are the most common diseases in industrialized countries.

Metabolic diseases like obesity and T2D are known to impair both the olfactory and hypothalamic systems. There is no doubt of the existence of the “olfactory-hypothalamic axis”, moreover it is clear that the bidirectional relationship is able to control metabolic processes like food intake, autonomic activity of tissues and more, thus modulating metabolic balance.

In addition, there is also compelling evidence that the olfactory system is a major player for the development of metabolic diseases. The current review proposes that intervening the olfactory system could enhance the activity of the hypothalamus through its multi-synaptic connections. We propose a noninvasive approach as the i.n. administration of drugs to improve the metabolic impairments in obese and diabetic patients.

Although there are some important questions to be answered before betting for the olfactory system as a conduit to improve hypothalamic activity: (1) there are no reports describing the neuronal and genetic profiles of the olfactory regions in postmortem brains, therefore, the mechanisms underlying the olfactory impairments observed in these diseases remain unknown (2) Although there is evidence indicating that the activity of the olfactory system can change blood glucose levels, enhance lipid oxidation in the adipose tissue and other metabolic functions, there is no evidence that this effects are carried out through a direct input to hypothalamic neurons. The only evidence of this was provided by Chen et al., but this study did not demonstrate that the sensory activation of the ARC has an implication in metabolism. Therefore, future studies should demonstrate that the stimulation of the primary olfactory regions can in fact modulate insulin sensitivity, glucose metabolism, lipid oxidation, through a hypothalamic pathway.

Conclusion

The possible anatomic pathways involved in the modulation of energy balance regulated by the activity of the olfactory system have been reported. Evidence also suggests that the olfactory system could be involved in the development of metabolic diseases such as obesity and type two diabetes. Here we propose a model to explain its implication for the maintenance of the metabolic homeostasis of the organism. The use of alternative therapies such as the intranasal administration of drugs, aimed to regulate and improve the activity of the olfactory system that in turn will be able to control the neuronal activity of hypothalamic centers, could represent a suitable approach to deliver drugs and prevent/ameliorate the metabolic impairments observed in obese and diabetic patients.

Acknowledgements

Doctor Mara Alaide Guzmán-Ruiz is part of the Subprograma de Incorporación de Jóvenes Académicos de Carrera (SIJA), UNAM. The authors would like to thank María Josefina Bolado Garza, Head of the Translation Department of the Research Division, Facultad de Medicina, UNAM and Rebeca Mendez Hernández for proof-reading and Drs Octavio Fabián Mercado-Gómez and Virginia Arriaga-Ávila for their technical support.

Funding

This study was supported by grants DGAPA-PAPIIT IN215716 and IN221819 to RGG and IA204121 to MAGR.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Mara Alaide Guzmán-Ruiz, Email: marda1808@gmail.com.

Rosalinda Guevara-Guzmán, Email: rguevara@unam.mx.

References

- Aimé P, Hegoburu C, Jaillard T, Degletagne C, Garcia S, Messaoudi B, Thevenet M, Lorsignol A, Duchamp C, Am M, Ak J (2012) A Physiological increase of insulin in the olfactory bulb decreases detection of a learned aversive odor and abolishes food odor-induced sniffing behavior in rats. PLoS One 7(12):E51227. 10.1371/Journal.Pone.0051227 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aimé P, Palouzier-Paulignan B, Salem R, Al Koborssy D, Garcia S, Duchamp C, Romestaing C, Ak J (2014) Modulation Of olfactory sensitivity and glucose-sensing by the feeding state in obese Zucker Rats. Front Behav Neurosci 8:326. 10.3389/Fnbeh.2014.00326 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akingbemi BT (2013) Adiponectin receptors in energy homeostasis and obesity pathogenesis. Prog Mol Biol Trans Sci 114:317–342. 10.1016/B978-0-12-386933-3.00009-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anand BK, Brobeck JR (1951) Localization of a “feeding center” in the hypothalamus of the rat. Proc Soc Expt Biol Med Soc Expt Biol Med 77(2):323–324. 10.3181/00379727-77-18766 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Apelbaum AF, Chaput MA (2003) Rats habituated to chronic feeding restriction show a smaller increase in olfactory bulb reactivity compared to newly fasted rats. Chem Senses 28(5):389–395. 10.1093/Chemse/28.5.389 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arase K, Fisler JS, Shargill NS, York DA, Bray GA (1988) Intracerebroventricular infusions of 3-Ohb and insulin in a rat model of dietary obesity. Am J Physiol 255(6 Pt 2):R974-981. 10.1152/Ajpregu.1988.255.6.R974 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Badonnel K, Mc L, Durieux D, Monnerie R, Caillol M, Baly C (2014) Rat strains with different metabolic statuses differ in food olfactory-driven behavior. Behav Brain Res 270:228–239. 10.1016/J.Bbr.2014.05.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Badonnel K, Mc L, Monnerie R, Durieux D, Caillol M, Baly C (2012) Chronic restricted access to food leading to undernutrition affects rat neuroendocrine status and olfactory-driven behaviors. Horm Behav 62(2):120–127. 10.1016/J.Yhbeh.2012.05.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baly C, Aioun J, Badonnel K, Mc L, Durieux D, Schlegel C, Salesse R, Caillol M (2007) Leptin and its receptors are present in the rat olfactory mucosa and modulated by the nutritional status. Brain Res 1129(1):130–141. 10.1016/J.Brainres.2006.10.030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banks WA (2001) Leptin transport across the blood-brain barrier: implications for the cause and treatment of obesity. Curr Pharm Des 7(2):125–133. 10.2174/1381612013398310 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banks WA (2004) The source of cerebral insulin. Eur J Pharmacol 490(1–3):5–12. 10.1016/J.Ejphar.2004.02.040 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banks WA, Kastin AJ, Huang W, Jaspan JB, Lm Maness (1996) Leptin enters the brain by a saturable system independent of insulin. Peptides 17(2):305–311. 10.1016/0196-9781(96)00025-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banks WA, Kastin AJ, Pan W (1999) Uptake and degradation of blood-borne insulin by the olfactory bulb. Peptides 20(3):373–378. 10.1016/S0196-9781(99)00045-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banks WA, Owen JB, Erickson MA (2012) Insulin in the brain: there and back again. Pharmacol Ther 136(1):82–93. 10.1016/J.Pharmthera.2012.07.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baskin DG, Woods SC, West DB, Van Houten M, Posner BI, Dorsa DM, Porte D (1983) Immunocytochemical detection of insulin in rat hypothalamus and its possible uptake from cerebrospinal fluid. Endocrinology 113(5):1818–1825. 10.1210/Endo-113-5-1818 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benedict C, Brede S, Hb S, Lehnert H, Schultes B, Born J, Hallschmid M (2011) Intranasal insulin enhances postprandial thermogenesis and lowers postprandial serum insulin levels in healthy men. Diabetes 60(1):114–118. 10.2337/Db10-0329 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benomar Y, Roy AF, Aubourg A, Djiane J, Taouis M (2005) Cross down-regulation of leptin and insulin receptor expression and signalling in a human neuronal cell line. Biochem J 388(Pt3):929–939. 10.1042/bj20041621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berg Ah, Combs Tp DuX, Brownlee M, Pe S (2001) The adipocyte-secreted protein Acrp30 enhances hepatic insulin action. Nat Med 7(8):947–953. 10.1038/90992 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berger S, Pho H, Fleury-Curado T, Bevans-Fonti S, Younas H, Mk S, Jc J, Anokye-Danso F, Rs A, Lw E, Mendelowitz D, Ar S, Vy P (2019) Intranasal leptin relieves sleep-disordered breathing in mice with diet-induced obesity. Am J Respiratory Crit Care Med 199(6):773–783. 10.1164/Rccm.201805-0879oc [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bomfim TR, Forny-Germano L, Lb S, Brito-Moreira J, Jc H, Decker H, Ma S, Kazi H, Hm M, Pl M, Holscher C, Se A, Talbot K, Wl K, Dp M, St F, Fg DF (2012) An anti-diabetes agent protects the mouse brain from defective insulin signaling caused by alzheimer’s disease- associated Aβ oligomers. J Clin Investig 122(4):1339–1353. 10.1172/Jci57256 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brady S, Lalli P, Midha N, Chan A, Garven A, Chan C, Toth C (2013) Presence of neuropathic pain may explain poor performances on olfactory testing in diabetes mellitus patients. Chem Senses 38(6):497–507. 10.1093/Chemse/Bjt013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown LM, Clegg DJ, Benoit SC, Woods SC (2006) Intraventricular insulin and leptin reduce food intake and body weight in C57bl/6j mice. Physiol Behav 89(5):687–691. 10.1016/J.Physbeh.2006.08.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brünner YF, Benedict C, Freiherr J (2013) Intranasal insulin reduces olfactory sensitivity in normosmic humans. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 98(10):E1626-1630. 10.1210/Jc.2013-2061 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caillol M, Aïoun J, Baly C, Ma P, Salesse R (2003) Localization of orexins and their receptors in the rat olfactory system: possible modulation of olfactory perception by a neuropeptide synthetized centrally or locally. Brain Res 960(1–2):48–61. 10.1016/S0006-8993(02)03755-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaigneau E, Tiret P, Lecoq J, Ducros M, Knöpfel T, Charpak S (2007) The relationship between blood flow and neuronal activity in the rodent olfactory bulb. J Neurosci Off J Soc Neurosci 27(24):6452–6460. 10.1523/Jneurosci.3141-06.2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan JYK, García-Esquinas E, Ko Oh, Mcf T, Sy L (2017) The association between diabetes and olfactory function in adults. Chem Senses 43(1):59–64. 10.1093/Chemse/Bjx070 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chelminski Y, Magnan C, Luquet Sh, Everard A, Meunier N, Gurden H, Martin C (2017) Odor-induced neuronal rhythms in the olfactory bulb are profoundly modified in Ob/Ob obese mice. Front Physiol 8:2. 10.3389/Fphys.2017.00002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen W, Balland E, Ma C (2017) Hypothalamic insulin resistance in obesity: effects on glucose homeostasis. Neuroendocrinology 104(4):364–381. 10.1159/000455865 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y, Yc L, Tw K, Za K (2015) Sensory detection of food rapidly modulates arcuate feeding circuits. Cell 160(5):829–841. 10.1016/J.Cell.2015.01.033 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng X, Wang Z, Yang J, Ma M, Lu T, Xu G, Liu X (2011) Acidic fibroblast growth factor delivered intranasally induces neurogenesis and angiogenesis in rats after ischemic stroke. Neurol Res 33(7):675–680. 10.1179/1743132810y.0000000004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coll AP, Farooqi IS, Challis BG, Yeo GS, O’rahilly S (2004) Proopiomelanocortin and energy balance: insights from human and murine genetics. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 89(6):2557–2562. 10.1210/Jc.2004-0428 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Combs TP, Berg AH, Obici S, Scherer PE, Rossetti L (2001) Endogenous glucose production is inhibited by the adipose-derived protein Acrp30. J Clin Invest 108(12):1875–1881. 10.1172/Jci14120 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cone RD, Ma C, Aa B, Fan W, Dl M, Mj L (2001) The arcuate nucleus as a conduit for diverse signals relevant to energy homeostasis. Int J Obes Related Metab Disorder J Int Assoc Study Obes 25(Suppl 5):S63-67. 10.1038/Sj.Ijo.0801913 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coppari R, Ichinose M, Lee CE, Pullen AE, Kenny CD, Mcgovern RA, Tang V, Liu SM, Ludwig T, Chua SC, Lowell BB, Elmquist JK (2005) The hypothalamic arcuate nucleus: a key site for mediating leptin’s effects on glucose homeostasis and locomotor activity. Cell Metab 1(1):63–72. 10.1016/J.Cmet.2004.12.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Couturier C, Jockers R (2003) Activation of the leptin receptor by a ligand-induced conformational change of constitutive receptor dimers. J Biol Chem 278(29):26604–26611. 10.1074/Jbc.M302002200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Croy I, Krone F, Walker S, Hummel T (2015) Olfactory processing: detection of rapid changes. Chem Senses 40(5):351–355. 10.1093/Chemse/Bjv020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Das P, Parsons AD, Scarborough J, Hoffman J, Wilson J, Rn T, Jm O, Da F (2005) Electrophysiological and behavioral phenotype of insulin receptor defective mice. Physiol Behav 86(3):287–296. 10.1016/J.Physbeh.2005.08.024 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Felice FG, Ferreira ST (2014) Inflammation, defective insulin signaling, and mitochondrial dysfunction as common molecular denominators connecting type 2 diabetes to Alzheimer disease. Diabetes 63(7):2262–2272. 10.2337/Db13-1954 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delaere F, Akaoka H, De Vadder F, Duchampt A, Mithieux G (2013) Portal glucose influences the sensory, cortical and reward systems in rats. Eur J Neurosci 38(10):3476–3486. 10.1111/Ejn.12354 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dodd GT, Xirouchaki CE, Eramo M, Mitchell CA, Andrews ZB, Henry BA, Cowley MA, Tiganis T (2019) Intranasal targeting of hypothalamic ptp1b and tcptp reinstates leptin and insulin sensitivity and promotes weight loss in obesity. Cell Reports 28(11):2905. 10.1016/J.Celrep.2019.08.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards DA, Nahai FR, Wright P (1993) Pathways linking the olfactory bulbs with the medial preoptic anterior hypothalamus are important for intermale aggression in mice. Physiol Behav 53(3):611–615. 10.1016/0031-9384(93)90162-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edwin Thanarajah S, Iglesias S, Kuzmanovic B, Rigoux L, Ke S, Jc B, Tittgemeyer M (2019) Modulation of midbrain neurocircuitry by intranasal insulin. Neuroimage 194:120–127. 10.1016/J.Neuroimage.2019.03.050 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El Messari S, Leloup C, Quignon M, Mj B, Penicaud L, Arluison M (1998) Immunocytochemical localization of the insulin-responsive glucose transporter 4 (Glut4) in the rat central nervous system. J Comp Neurol 399(4):492–512 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El-Haschimi K, Pierroz DD, Hileman SM, Bjørbaek C, Flier JS (2000) Two defects contribute to hypothalamic leptin resistance in mice with diet-induced obesity. J Clin Investig 105(12):1827–1832. 10.1172/Jci9842 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elmquist JK, Maratos-Flier E, Saper CB, Flier JS (1998) Unraveling the central nervous system pathways underlying responses to leptin. Nat Neurosci 1(6):445–450 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Enck PRN, Sauer H, Klosterhalfen S, Mack I, Zipfel S, Teufel M (2014) Almost nothing-not even bariatric surgery for obesity-chances olfactory sensitivity. J Res Obes. 10.5171/2014.491890 [Google Scholar]

- Engin A (2017) Diet-induced obesity and the mechanism of leptin resistance. Adv Expt Med Biol 960:381–397. 10.1007/978-3-319-48382-5_16 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fadool DA, Tucker K, Pedarzani P (2011) Mitral cells of the olfactory bulb perform metabolic sensing and are disrupted by obesity at the level of the Kv1.3 ion channel. Plos One 6(9):e24921. 10.1371/Journal.Pone.0024921 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fan L, Ding L, Lan J, Niu J, He Y, Song L (2019) Fibroblast growth factor-1 improves insulin resistance via repression of Jnk-mediated inflammation. Front Pharmacol 10:1478. 10.3389/Fphar.2019.01478 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fardone E, Celen AB, Schreiter NA, Thiebaud N, Cooper MI, Fadool DA (2019) Loss of odor-induced C-fos expression of juxtaglomerular activity following maintenance of mice on fatty diets. J Bioenerg Biomembranes 51(1):3–13. 10.1007/S10863-018-9769-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernandez-Garcia JC, Alcaide J, Santiago-Fernandez C, Mm R-R, Aguera Z, Baños R, Botella C, De La Torre R, Jm F-R, Fruhbeck G, Gomez-Ambrosi J, Jimenez-Murcia S, Menchon JM, Casanueva FF, Fernandez-Aranda F, Tinahones FJ, Garrido-Sanchez L (2017) Correction: an increase in visceral fat is associated with a decrease in the taste and olfactory capacity. PLoS One 12(3):E0173588. 10.1371/Journal.Pone.0173588 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fliedner S, Schulz C, Lehnert H (2006) Brain uptake of intranasally applied radioiodinated leptin in wistar rats. Endocrinology 147(5):2088–2094. 10.1210/En.2005-1016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedman JM (2002) The function of leptin in nutrition, weight, and physiology. Nutr Rev. 10.1301/002966402320634878 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gascuel J, Lemoine A, Rigault C, Datiche F, Benani A, Penicaud L, Lopez-Mascaraque L (2012) Hypothalamus-olfactory system crosstalk: orexin a immunostaining in mice. Front Neuroanat 6:44. 10.3389/Fnana.2012.00044 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gasser E, Moutos CP, Downes M, Evans RM (2017) Fgf1 - a new weapon to control type 2 diabetes mellitus. Nat Rev Endocrinol 13(10):599–609. 10.1038/Nrendo.2017.78 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Getchell TV, Kwong K, Saunders CP, Stromberg AJ, Getchell ML (2006) Leptin regulates olfactory-mediated behavior in Ob/Ob mice. Physiol Behav 87(5):848–856. 10.1016/J.Physbeh.2005.11.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gisslinger H, Svoboda T, Clodi M, Gilly B, Ludwig H, Havelec L, Luger A (1993) Interferon-alpha stimulates the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis in vivo and in vitro. Neuroendocrinology 57(3):489–495. 10.1159/000126396 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gorska E, Popko K, Stelmaszczyk-Emmel A, Ciepiela O, Kucharska A, Wasik M (2010) Leptin receptors. Eur J Med Res 15:50–54. 10.1186/2047-783x-15-S2-50 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gouveri E, Katotomichelakis M, Gouveris H, Danielides V, Maltezos E, Papanas N (2014) Olfactory dysfunction in type 2 diabetes mellitus: an additional manifestation of microvascular disease? Angiology 65(10):869–876. 10.1177/0003319714520956 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greene MW, Ruhoff MS, Burrington CM, Garofalo RS, Oreña SJ (2010) Tnfalpha activation of Pkcdelta, mediated by Nfkappab and Er stress, cross-talks with the insulin signaling cascade. Cell Signal 22(2):274–284. 10.1016/J.Cellsig.2009.09.029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guillot G, Chapouthier G (1996) Olfaction, gabaergic neurotransmission in the olfactory bulb, and intermale aggression in mice: modulation by steroids. Behav Genet 26(5):497–504. 10.1007/Bf02359754 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halaas JL, Boozer C, Blair-West J, Fidahusein N, Da D, Jm F (1997) Physiological response to long-term peripheral and central leptin infusion in lean and obese mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 94(16):8878–8883. 10.1073/Pnas.94.16.8878 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hallschmid M, Benedict C, Schultes B, Hl F, Born J, Kern W (2004) Intranasal insulin reduces body fat in men but not in women. Diabetes 53(11):3024–3029. 10.2337/Diabetes.53.11.3024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanson LR, Fine JM, Svitak AL, Faltesek KA (2013) Intranasal administration of Cns therapeutics to awake mice. JOVE. 10.3791/4440 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hass N, Haub H, Stevens R, Breer H, Schwarzenbacher K (2008) Expression of adiponectin receptor 1 in olfactory mucosa of mice. Cell Tissue Res 334(2):187–197. 10.1007/S00441-008-0677-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hassall CJ, Hoyle CH (1997) Heme oxygenase-2 and nitric oxide synthase in guinea-pig intracardiac neurones. Neuroreport 8(4):1043–1046. 10.1097/00001756-199703030-00045 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hassing LB, Grant MD, Hofer SM, Pedersen NL, Nilsson SE, Berg S, Mcclearn G, Johansson B (2004) Type 2 diabetes mellitus contributes to cognitive decline in old age: a longitudinal population-based study. J Int Neuropsychol Soc 10(4):599–607. 10.1017/S1355617704104165 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heni M, Wagner R, Kullmann S, Veit R, Mat Husin H, Linder K, Benkendorff C, Peter A, Stefan N, Häring Hu, Preissl H, Fritsche A (2014) Central insulin administration improves whole-body insulin sensitivity via hypothalamus and parasympathetic outputs in men. Diabetes 63(12):4083–4088. 10.2337/Db14-0477 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hichami A, Datiche F, Ullah S, Liénard F, Jm C, Cattarelli M, Na K (2007) olfactory discrimination ability and brain expression of C-Fos, Gir And Glut1 Mrna are altered in N-3 fatty acid-depleted rats. Behav Brain Res 184(1):1–10. 10.1016/J.Bbr.2007.06.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hileman SM, Pierroz DD, Masuzaki H, Bjørbaek C, El-Haschimi K, Banks WA, Flier JS (2002) Characterizaton of short isoforms of the leptin receptor in rat cerebral microvessels and of brain uptake of leptin in mouse models of obesity. Endocrinology 143(3):775–783. 10.1210/endo.143.3.8669 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Houseknecht KL, Baile CA, Matteri RL, Spurlock ME (1998) The biology of leptin: a review. J Anim Sci 76(5):1405–1420. 10.2527/1998.7651405x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ihle JN, Kerr IM (1995) Jaks And Stats in signaling by the cytokine receptor superfamily. Trend Gene 11(2):69–74. 10.1016/S0168-9525(00)89000-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang XF, Lin S, Zhang R (1997) Upregulation of leptin receptor mRNA expression in obese mouse brain. Neuroreport 8(4):1035–1038. 10.1097/00001756-199703030-00043 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobson A, Green E, Haase L, Szajer J, Murphy C (2019) Differential effects of BMI on brain response to odor in olfactory, reward and memory regions: evidence from Fmri. Nutrients. 10.3390/Nu11040926 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jauch-Chara K, Friedrich A, Rezmer M, Melchert Uh, Gs-E H, Hallschmid M, Km O (2012) Intranasal insulin suppresses food intake via enhancement of brain energy levels in humans. Diabetes 61(9):2261–2268. 10.2337/Db12-0025 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiménez A, Organista-Juárez D, Torres-Castro A, Ma G-R, Estudillo E, Guevara-Guzmán R (2020) Olfactory dysfunction in diabetic rats is associated with Mir-146a overexpression and inflammation. Neurochem Res 45(8):1781–1790. 10.1007/S11064-020-03041-Y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jojo JM, Kuppusamy G, De A, Karri V (2019) Formulation and optimization of intranasal nanolipid carriers of pioglitazone for the repurposing in alzheimer’s disease using Box-Behnken design. Drug Dev Indust Pharm 45(7):1061–1072. 10.1080/03639045.2019.1593439 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jilliard AK, Al Koborssy D, Fadool DA, Palouzier-Paulignan B (2017) Nutrient sensing: another chemosensitivity of the olfactory system. Front Physiol 8:468. 10.3389/Fphys.2017.00468 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kemnitz JW, Elson DF, Roecker EB, Baum ST, Bergman RN, Meglasson MD (1994) Pioglitazone increases insulin sensitivity, reduces blood glucose, insulin, and lipid levels, and lowers blood pressure, in obese insulin-resistant rhesus monkeys. Diabetes 43(2):204–211. 10.2337/Diab.43.2.204 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khafagy ES, Kamei N, Fujiwara Y, Okumura H, Yuasa T, Kato M, Arime K, Nonomura A, Ogino H, Hirano S, Sugano S, Takeda-Morishita M (2020) Systemic and brain delivery of leptin via intranasal coadministration with cell-penetrating peptides and its therapeutic potential for obesity. J Control Release Soc 319:397–406. 10.1016/J.Jconrel.2020.01.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kikuta S, Ml F, Homma R, Yamasoba T, Nagayama S (2013) Odorant response properties of individual neurons in an olfactory glomerular module. Neuron 77(6):1122–1135. 10.1016/J.Neuron.2013.01.022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kleinridders A, Ferris HA, Cai W, Kahn CR (2014) Insulin action in brain regulates systemic metabolism and brain function. Diabetes 63(7):2232–2243. 10.2337/Db14-0568 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klingler E (2017) Development and organization of the evolutionarily conserved three-layered olfactory cortex. Eneuro. 10.1523/Eneuro.0193-16.2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koch CE, Lowe C, Legler K, Benzler J, Boucsein A, Böttiger G, Grattan DR, Williams LM, Tups A (2014) Central adiponectin acutely improves glucose tolerance in male mice. Endocrinology 155(5):1806–1816. 10.1210/En.2013-1734 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Komano-Inoue S, Manabe H, Ota M, Kusumoto-Yoshida I, Tk Y, Mori K, Yamaguchi M (2014) Top-down inputs from the olfactory cortex in the postprandial period promote elimination of granule cells in the olfactory bulb. Eur J Neurosci 40(5):2724–2733. 10.1111/Ejn.12679 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kondoh K, Lu Z, Ye X, Olson DP, Lowell BP, Buck LB (2016) A specific area of olfactory cortex involved in stress hormone responses to predator odours. Nature 532(7597):103–106. 10.1038/Nature17156 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kos K, Harte AL, Da Silva NF, Tonchev A, Chaldakov G, James S, Snead DR, Hoggart B, Ohare JP, Mcternan PG, Kumar S (2007) Adiponectin and resistin in human cerebrospinal fluid and expression of adiponectin receptors in the human hypothalamus. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 92(3):1129–1136. 10.1210/Jc.2006-1841 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwon O, Kim KW, Kim MS (2016) Leptin signalling pathways in hypothalamic neurons. Cell Mol Life Sci 73(7):1457–1477. 10.1007/S00018-016-2133-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lacroix MC, Badonnel K, Meunier N, Tan F, Schlegel-Le Poupon C, Durieux D, Monnerie R, Baly C, Congar P, Salesse R, Caillol M (2008) Expression of insulin system in the olfactory epithelium: first approaches to its role and regulation. J Neuroendocrinol 20(10):1176–1190. 10.1111/J.1365-2826.2008.01777.X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lacroix MC, Caillol M, Durieux D, Monnerie R, Grebert D, Pellerin L, Repond C, Tolle V, Zizzari P, Baly C (2015) Long-lasting metabolic imbalance related to obesity alters olfactory tissue homeostasis and impairs olfactory-driven behaviors. Chem Senses 40(8):537–556. 10.1093/Chemse/Bjv039 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laska M, Hudson R (1993) Assessing olfactory performance in a new world primate. Saimiri Sciureus Physiol Behav 53(1):89–95. 10.1016/0031-9384(93)90015-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leloup C, Arluison M, Lepetit N, Cartier N, Marfaing-Jallat P, Ferré P, Pénicaud L (1994) Glucose transporter 2 (Glut 2): expression in specific brain nuclei. Brain Res 638(1–2):221–226. 10.1016/0006-8993(94)90653-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lietzau G, Davidsson W, Cg Ö, Chiazza F, Nathanson D, Pintana H, Skogsberg J, Klein T, Nyström T, Darsalia V, Patrone C (2018) Type 2 diabetes impairs odour detection, olfactory memory and olfactory neuroplasticity; effects partly reversed by the Dpp-4 inhibitor linagliptin. Acta Neuropathol Commun 6(1):14. 10.1186/S40478-018-0517-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y, Liu F, Grundke-Iqbal I, Iqbal K, Cx G (2011) Deficient brain insulin signalling pathway in Alzheimer’s disease and diabetes. J Pathol 225(1):54–62. 10.1002/Path.2912 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu ZJ, Bian J, Liu J, Endoh A (2007) Obesity reduced the gene expressions of leptin receptors in hypothalamus and liver. Horm Metab Res 39(7):489–494. 10.1055/S-2007-981680 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Livingston JN, Unger JW, Moxley RT, Moss A (1993) Phosphotyrosine-containing proteins in the CNS of obese Zucker rats are decreased in the absence of changes in the insulin receptor. Neuroendocrinology 57(3):481–488. 10.1159/000126395 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loch D, Breer H, Strotmann J (2015) Endocrine modulation of olfactory responsiveness: effects of the orexigenic hormone ghrelin. Chem Senses 40(7):469–479. 10.1093/Chemse/Bjv028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loch D, Heidel C, Breer H, Strotmann J (2013) Adiponectin enhances the responsiveness of the olfactory system. PLoS One 8(10):E75716. 10.1371/Journal.Pone.0075716 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lou G, Zhang Q, Xiao F, Xiang Q, Su Z, Zhang L, Yang P, Yang Y, Zheng Q, Huang Y (2012) Intranasal Administration of Tat-Hafgf(14-154) attenuates disease progression in a mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. Neuroscience 223:225–237. 10.1016/J.Neuroscience.2012.08.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mantzoros CS (1999) The role of leptin in human obesity and disease: a review of current evidence. Ann Intern Med 130(8):671–680. 10.7326/0003-4819-130-8-199904200-00014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marks DR, Tucker K, Cavallin MA, Mast TG, Fadool DA (2009) Awake intranasal insulin delivery modifies protein complexes and alters memory, anxiety, and olfactory behaviors. J Neurosci Off J Soc Neurosci 29(20):6734–6751. 10.1523/Jneurosci.1350-09.2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin B, Maudsley S, White CM, Egan JM (2009) Hormones in the naso-oropharynx: endocrine modulation of taste and smell. Trends Endocrinol Metab Tem 20(4):163–170. 10.1016/J.Tem.2009.01.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin RL, Perez E, He YJ, Dawson R, Jr., Millard WJ (2000) Leptin resistance is associated with hypothalamic leptin receptor mRNA and protein downregulation. Metab Clin Exp 49(11):1479–1484. 10.1053/meta.2000.17695 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Mazor R, Friedmann-Morvinski D, Alsaigh T, Kleifeld O, Kistler EB, Rousso-Noori L, Huang C, Li JB, Verma IM, Schmid-Schönbein GW (2018) Cleavage of the leptin receptor by matrix metalloproteinase-2 promotes leptin resistance and obesity in mice. Sci Trans Med. 10.1126/Scitranslmed.Aah6324 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McFarlane MB, Bruhn TO, Jackson IM (1993) Postsomatostatin hypersecretion of growth hormone from perifused rat anterior pituitary cells is dependent on calcium influx. Neuroendocrinology 57(3):496–502. 10.1159/000126397 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meguid MM, Gleason JR, Yang ZJ (1993) Olfactory bulbectomy in rats modulates feeding pattern but not total food intake. Physiol Behav 54(3):471–475. 10.1016/0031-9384(93)90238-B [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meissner-Bernard C, Dembitskaya Y, Venance L, Fleischmann A (2019) encoding of odor fear memories in the mouse olfactory cortex. Current. 10.1016/J.Cub.2018.12.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meister B (2000) Control of food intake via leptin receptors in the hypothalamus. Vitam Horm 59:265–304. 10.1016/S0083-6729(00)59010-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meister B, Håkansson ML (2001) Leptin receptors in hypothalamus and circumventricular organs. Clin Expt Pharmacol Physiol 28(7):610–617. 10.1046/J.1440-1681.2001.03493.X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Min JY, Min KB (2018) Insulin resistance and the increased risk for smell dysfunction in us adults. Laryngoscope 128(9):1992–1996. 10.1002/Lary.27093 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miranda-Martínez A, Of M-G, Arriaga-Ávila V, Guevara-Guzmán R (2017) Distribution of adiponectin receptors 1 and 2 in the rat olfactory bulb and the effect of adiponectin injection on insulin receptor expression. Int J Endocrinol 2017:4892609. 10.1155/2017/4892609 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miro JI, Canguilhem B, Schmitt P (1980) Effects of bulbectomy on hibernation, food intake and body weight in the European Hamster. Cricetus Cricetus Physiol Behav 24(5):859–862. 10.1016/0031-9384(80)90141-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miro JL, Canguilhem B, Schmitt P, Koch A (1982) Hyperphagia and obesity after olfactory bulbectomy performed at different times of the year in the European Hamster. Physiol Behav 29(4):681–685. 10.1016/0031-9384(82)90238-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyazaki Y, Mahankali A, Matsuda M, Glass L, Mahankali S, Ferrannini E, Cusi K, Mandarino LJ, Defronzo RA (2001) Improved glycemic control and enhanced insulin sensitivity in type 2 diabetic subjects treated with pioglitazone. Diabetes Care 24(4):710–719. 10.2337/Diacare.24.4.710 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyazaki Y, Mahankali A, Wajcberg E, Bajaj M, Mandarino LJ, Defronzo RA (2004) Effect of pioglitazone on circulating adipocytokine levels and insulin sensitivity in type 2 diabetic patients. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 89(9):4312–4319. 10.1210/Jc.2004-0190 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mojiminiyi OA, Abdella NA, Al Arouj M, Ben Nakhi A (2005) Adiponectin, insulin resistance and clinical expression of the metabolic syndrome in patients with type 2 diabetes. Int J Obes 31(2):213–220. 10.1038/Sj.Ijo.0803355 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moloney AM, Griffin RJ, Timmons S, O’connor R, Ravid R, O’neill C (2010) Defects In Igf-1 receptor, insulin receptor and Irs-1/2 in Alzheimer’s disease indicate possible resistance to Igf-1 and insulin signalling. Neurobiol Aging 31(2):224–243. 10.1016/J.Neurobiolaging.2008.04.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murata K, Kinoshita T, Fukazawa Y, Kobayashi K, Kobayashi K, Miyamichi K, Okuno H, Bito H, Sakurai Y, Yamaguchi M, Mori K, Manabe H (2019) Gabaergic neurons in the olfactory cortex projecting to the lateral hypothalamus in mice. Sci Rep 9(1):7132. 10.1038/S41598-019-43580-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagayama S, Homma R, Imamura F (2014) Neuronal organization of olfactory bulb circuits. Front Neural Circuit 8:98. 10.3389/Fncir.2014.00098 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naka A, Riedl M, Luger A, Hummel T, Mueller CA (2010) Clinical significance of smell and taste disorders in patients with diabetes mellitus. Eur Arch Oto-Rhino-Laryngol 267(4):547–550. 10.1007/S00405-009-1123-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niijima A, Nagai K (2003) Effect of olfactory stimulation with flavor of grapefruit oil and lemon oil on the activity of sympathetic branch in the white adipose tissue of the epididymis. Expt Biol Med 228(10):1190–1192. 10.1177/153537020322801014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nusbaum N (1999) Aging and sensory senescence. South Med J 92(3):267–275. 10.1097/00007611-199903000-00002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oettl LL, Kelsch W (2018) Oxytocin and olfaction. Curr Top Behav Neurosci 35:55–75. 10.1007/7854_2017_8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oettl LL, Ravi N, Schneider M, Mf S, Schneider P, Mitre M, Da Silva GM, Froemke RC, Chao MV, Young WS, Meyer-Lindenberg A, Grinevich V, Shusterman R, Kelsch W (2016) Oxytocin enhances social recognition by modulating cortical control of early olfactory processing. Neuron 90(3):609–621. 10.1016/J.Neuron.2016.03.033 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palouzier-Paulignan B, Lacroix MC, Aimé P, Baly C, Caillol M, Congar P, Julliard AK, Tucker K, Fadool DA (2012) Olfaction under metabolic influences. Chem Senses 37(9):769–797. 10.1093/Chemse/Bjs059 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pan W, Hsuchou H, He Y, Sakharkar A, Cain C, Yu C, Kastin AJ (2008) Astrocyte leptin receptor (ObR) and leptin transport in adult-onset obese mice. Endocrinology 149(6):2798–2806. 10.1210/en.2007-1673 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pandit R, Beerens S, Rah A (2017) Role of leptin in energy expenditure: the hypothalamic perspective. Am J Physiol Reg Integr Comp Physiol 312(6):R938–R947. 10.1152/Ajpregu.00045.2016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pastor A, Fernández-Aranda F, Fitó M, Jiménez-Murcia S, Botella C, Jm F-R, Frühbeck G, Tinahones FJ, Fagundo AB, Rodriguez J, Agüera Z, Langohr K, Casanueva FF, De La Torre R (2016) A lower olfactory capacity is related to higher circulating concentrations of endocannabinoid 2-arachidonoylglycerol and higher body mass index in women. PLoS One 11(2):E0148734. 10.1371/Journal.Pone.0148734 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]