Abstract

My purpose in this paper is to help you experience for yourself the potential of poetry to heal by feeling its power through your own voice. Many people have an intuitive sense that voice in general and poetry in particular can be healing. We have all experienced the comfort of soothing words. Finding the words to articulate a traumatic experience can bring relief. A letter between friends who are fighting can heal a relational wound. People are frequently moved to write a poem in times of extremity. In mainstream culture there are subjects that are not talked about. They are taboo. For example, each of us is going to die, but we do not talk about dying. We are all in the dialogue of illness, death and dying, whether or not we are talking about it. Poetry gives us ways to talk about it. Multiple ways of utilizing poetry for healing, growth and transformation will be presented including the Poetry and Brain Cancer project at UCLA. Particular attention will be given to issues of Palliative care. The reader will be directed to the scientific evidence of the efficacy of utilizing expressive writing. The developing professional field of Poetry Therapy, and The National Association for Poetry Therapy will be discussed.

Keywords: poetry therapy, poetry and healing, voice and healing, poetry and medicine

Introduction

My purpose in this paper is to help you experience for yourself the potential of poetry to heal by experiencing the power of poetry through your own voice.

In the United States many people are scared of poetry. They have had bad experiences with it in school. People often believe that poetry is difficult or inaccessible or not relevant to them.

Modern poetry is based on voice, and must be passed through our ears. This is where the sense is made. So, when you read this article and you see poetry

Read it aloud

pass it through your ears

enjoy the

ride, and

know

the difference between poetry and prose

is that poetry is broken

into lines—

that is all.

When we speak, we use pauses and phrasing. When we speak, we breathe. When we write poetry, we have punctuation and line breaks. The line breaks are there to help the reader find the natural flow of poetry based on voice.

As you read poetry aloud

do it so that you are breathing

comfortably.

Let the sense of the poetry emerge

from your response to the rhythms

and tonal variations of the sound

as well as the meaning of the words.

The passage below is derived from a conversation I had with poet Li-Young Lee on the relationship between poetry and breath and life and death. When you read the passage, pause after each line and take a breath in. Feel for yourself the emergent meaning.

All of language is spoken on the out breath

All of life begins on the in

All of death is spoken on the out breath

All of life begins on the in

Poetry as a Natural Healing Practice

Many people have an intuitive sense that voice in general and poetry in particular can be healing. We have all had the experience of the comfort of soothing words. Finding the words to articulate a traumatic experience can bring relief. A letter between friends who are fighting can heal a relational wound. Poetry can spring from us naturally in times of need. People are frequently moved to write a poem in times of extremity.

In the aftermath of the World Trade Center attacks on September 11, 2001, poetry sprang up everywhere. A New York Times article on October 1, 2001, documented the phenomenon: “In the weeks since the terrorist attacks, people have been consoling themselves—and one another—with poetry in an almost unprecedented way … Improvised memorials often conceived around poems sprang up all over the city, in store windows, at bus stops, in Washington Square Park, Brooklyn Heights, and elsewhere. …”

Some catastrophes are so large, they seem to overwhelm ordinary language. Immediately after the recent tsunami disaster in Southeast Asia, the Los Angeles Times reported the witnesses were literally dumbstruck. Words failed them. They had lost their voices.

In mainstream culture, there are subjects we do not talk about. They are taboo. For example, even though each of us is going to die, we don't talk about dying. Instead, we avoid it. Even physicians are reluctant to talk with terminally ill patients about the patient's experience, however,

We are all in the dialogue

of illness

death

and dying

whether or not we are talking about it.

Poetry gives us ways to talk about it. My job as a poetry therapist is to use poetry and voice to help people get access to the wisdom they already have but cannot experience because they cannot find the words in ordinary language.

William Carlos Williams was a poet and a physician. He is credited with making voice the basis of modern poetry. He wrote in his poem Asphodel, That Greeny Flower (1)

It is difficult

to get the news from poems

yet men die miserably every day

for lack

of what is found there.

Two years ago, I was asked to pair poets with brain cancer patients at UCLA in the Department of Neuro-Oncology, so that the poets could help the patients find the words to articulate their experiences. One patient reported his dilemma following brain surgery to remove his cancer,

I felt I lost my edge

and then I lost my place

but the tragedy is

I have so much to say.

Although illness is usually discussed in terms of a patient's symptoms, deficit, or impairment, it is also about how people respond when faced with extreme circumstances and what they have to tell and teach us. One of the poems that came out of the poetry and brain cancer project was “Amazing Change” (2).

Amazing Change

We can go through amazing changes

when we are faced with knowing

we have limited time.

After one woman got brain cancer

she decided what she wanted

was to go to Africa

to see the gorillas.

She and her husband and the guides

began the long trek through the jungle

up the mountains, but the woman was

having trouble. The guides tried

to convince her to go back, but

she wouldn't.

She struggled and struggled.

Eventually she won the guides over

and everyone was rooting for her

but there came a point when

she couldn't go on, so

she laid down on the grass

and when she did, the gorillas

came out of the jungle

to her.

If you didn't read this poem aloud, do so now. What is your experience of reading this poem? How is it relevant to you? Do you identify with the woman or, perhaps, the husband or the guides or even the gorillas? Can you visualize the images, see the people trekking along, then lying down in the grass? What sounds can you hear? What is the smell of the jungle? What physical sensations do you feel in your body as the poem unfolds? What happens to your breathing when you read the last lines? How did the transformation that happened at the end of the poem affect you? Did you have any associations to the poem about a situation in your own life?

Whatever your experiences of reading this poem, they are examples of the ways that poetry works. It gets into us and plays through our psycho/neuro/immuno-sensory selves.

In other words

poetry has ways of working

that get under our skin,

which is to say

it has ways

to get in.

All of my professional life, I have used language embodied in voice as part of my medicine. Whether it was an attempt to talk someone through a traumatic experience or to help them understand the implications of their diagnosis or to aid them in finding the words to write their own stories and poetry, I have encouraged patients to speak and write their truths. At the same time, I have learned from them. One of the privileges of being clinicians is that we have a place in our patients' lives as they live through experiences that we may have yet to face ourselves.

It is becoming more and more common for people dealing with serious illnesses to write and publish their stories and poems as their own healing practice (3–11). Many physicians and other health care providers have joined in writing their own personal experiences with illness, death and dying (12–19).

So, it may be difficult

to get the news

from poems,

but it is becoming

more and more

common

Poetry and Therapy

In my private practice of family psychiatry, I often ask whether my patients do any writing and for what purpose. In my work with them, I support their writing and encourage its use whether it is through poetry, journals or personal letters. I encourage bringing the writing in as material for discussion, and I may make suggestions. For example, Writing in the third person gives distance to your voice, so try writing in the first person. I also sometimes gives assignments. For example, write what you are having difficulty saying, or bring in a poem which is particularly meaningful to you. This can then become a springboard for discussion and exploration. The poem “I Can't” by Carlene Shaff represents a turning point in her treatment, facilitated by using poetry therapy, and documented in her poem “I Can't.”

I Can't

I can't. I just can't. I can't do it all.

I can't be all things to all people

At all times and under all circumstances.

I can't be the one to always change my plans to suit another's.

I can't be the one to pick up after others all the time.

I can't work all day and stop at the grocery and cook dinner

And have it ready by 6:30.

I can't carry the weight of the world on my shoulders.

I need some support, too, and a rest.

I can't; can't, can't cantaloupe, can't canticle, can't cantilever,

Cantina, cantata, cantankerous, cannon,

Canape, canard, candelabra, can… can…,

Can I? Can I just do it? Can I do it all?

Can I ration my time to allow for my priorities?

Can I ask others to share the burdens?

Can I refuse this role of superwoman?

Can I just ‘say no?’

I can. I can just say no. I can just say,

“I'm out of the business of doing it all.”

I can take time for myself to breathe

And dream or just sit quietly.

And I will!

Did you experience the change that Carlene went through? Poetry therapy is not only used with individuals. It is frequently used in groups. Shahin Sakhi, a psychiatrist who attended a poetry therapy seminar, told me he had never previously written a poem or any other type of expressive writing. The first words he wrote were (19):

I am tired.

I have died so many times in so many ways.

I am tired of dying, dying again and again… .

The first death I remember is the beheading

of my pet pigeon

By my father

In the basement.

It was the first time he had shared this experience. Finding the words to express it was a deeply healing experience for Shahin, and his relief was palpable.

If the group's focus is on a particular theme, for example, cancer, I might use poems that relate directly to the illness. My poem “Eileen” is an account of an incident related to me by a friend that occurred between a mother and her daughter.

Eileen

Eileen has breast cancer.

The lump was removed last year.

It was chemotherapy and radiation

for the next six months.

Eileen lost weight.

Her skin burned.

She vomited every day.

Her hair fell out—

First wisps, then tufts,

then clumps.

Her daughter couldn't stand it—

She was only thirteen—

Seeing her mother

pull out her hair.

“I don't care!”

Yelled her daughter,

“I don't care.”

“Want to pull?” Said Eileen.

“Want to pull out some hair?”

At first she couldn't do it,

But her mother cupped her face with her hands.

“I need you baby. Help me. Take a pull.”

So the daughter grabbed a strand,

and it came out easy.

So she grabbed another

and another

then a clump

and out it came.

Then they put on music

and danced

and grabbed hair.

They played Chaplin

and burlesque.

Hitler had a funny moustache.

They put sideburns on Jews.

Eileen became a billy-goat.

They bayed at the moon.

When Eileen became bald,

they laughed, then they wept.

Then the daughter

pasted patches in her armpits

and a tuft between her legs.

“Look Mom.

I'm a woman now!”

She said.

Up and down

the women jumped and screamed

until they were exhausted

and Eileen's scalp turned red.

Then they laughed

and hugged

and went to bed.

In “Eileen” I wanted to capture the experience of a healing transformation and ritual passage between a mother and her daughter. Could you see the images and feel the experience of witnessing the transformation?

“Being the Stone,” is written from the point of view of the ritual object and is about how it is imbued with its power. Be sure to read “Being the Stone” aloud and feel the experience of actually being the stone and carrying this power to heal.

Being the Stone

I want to be the stone

and tell

how she held me

in the palm of her hand

rolled me between her fingers

slipped me into her mouth

tasted my salt

tumbled me around.

Then she ran her tongue along my edge

and rubbed my cool body across the scar

of her breast

put me in her pocket

took me home

gave me to her daughter—

a special gift.

When poems such as “Eileen” and “Being the Stone” are read to a group, people experience a resonance with their own stories in ways they may have never been put into words before. The poems need not be about illness specifically, but might otherwise embody themes that confronts the patients.

Twelve years ago, I myself was going through personally difficult times. One of my patients, a 32 year-old woman who was a wife and mother of a 2-year old daughter, died. At the same time my father was beginning his terminal decline from diabetic multisystem failure, and a friend of mine was dying from a cancer that had metastasized to her brain. In addition, I had recently had reconstructive knee surgery to repair torn ligaments, following which I was disabled for months.

I had never written much before except a few poems in earlier times of crisis. I developed ways of writing as my own healing practice, and I listened to the voices of other poets and writers doing the same (20).

Our voices are saturated with who we are, embodied in the rhythms, tonal variations, associations, images and other somato-sensory metaphors in addition to the content meaning of the words. Our voices are embodiments of ourselves, whether written or spoken. It is in times of extremity that we long to find words or hear another human voice letting us know we are not alone.

The poems “MeFather,” “What Waiting Is,” and “The Family Plot” were all written during this period (8,21). They represent a progression of my experience: from a dreamed awareness of my father's death as he began his terminal decline, through the realization of what the three year process had meant to me, to overwhelming grief in the aftermath of losing both my father and my friend, and, finally, an attempt to come to some resolution.

MeFather

I rose in his wake.

A dream crossed my eyes—

My father lying still in his tub.

I throw my arms around him yelling

Daddy, wake up!

Bubbles are bursting everywhere.

What Waiting Is

We sit on the bench in the hospital corridor

next to the cafeteria, and we wait.

You know what waiting is.

If you know anything, you know what waiting is.

It's not about you.

This is about

illness and hospitals and life and death.

This is about the smell of the disinfectant

that hits you in the head.

In the bathroom you look in the mirror.

What do you see?

Your father's sad face?

Your mother's eyes?

You catch the water cupped

in your thickened hands, splash it on your face,

and hope against hope you can wash it away—

the aging brown spots, the bags,

the swelling truth of waiting—

So you go back to that bench.

Maybe your mother is there or your wife

who is waiting for your father who is waiting

for the news from the surgeon

or the morphine for the pain

or the nurse who cleans bedpans

who is waiting for her shift to change

while another man's hand clamps white as a claw

to a clutch of bed sheets, and you wait.

So you hear the news,

and you take the long trip back from LA or Detroit—

wherever you're from—

and you see the faces of the drivers

as they approach you out of the fog,

and you see this one:

a woman hunched over the wheel like your mother,

and you think, It is my mother.

and you want to tell her everything,

how waiting kills and what it does to your life,

that fifty years of marriage is an eyelash blink,

but she's past you now and headed in the wrong direction,

so you wait.

Then, out of the corner of your eye,

you see your father's face in the driver's seat

of a '49 powder blue Pontiac sedan.

The thin sliver of his moonlit profile's smiling,

but the nose is too long and it's not really him,

and besides he'd never understand anyway—

this impatience, this anger, this rage, this love,

this fog on the windshield,

this never even knowing if it's inside or out—

because his whole life was waiting,

and what does a fish know of the water

or a bird of the air?

So you push the leaden accelerator down

and act like you're headed to some small emergency,

and you don't give a damn about the cop waiting

behind the billboard or death over your left shoulder,

and you think you might want to pray,

and you do pray, but you don't know what for,

and, anyway, you're driving, so you go back

to the endless lines of headlights and traffic

and exit signs until you get home to see the light

flash on your answering machine,

but you don't pick it up.

Instead, you go to the bathroom,

take a shower, take a piss,

pull out a carton of leftover food—anything—

but you can't swallow it.

So you push the button,

and it's your sister's voice,

but it's choked,

and she can't speak.

That's how I learned that the waiting was over,

that my life changed forever,

that this end was a beginning,

but I didn't know for what.

I used to think it was death I was waiting for,

but that's not what this is. This is life.

So you show up and do the work

and love who you love, and you learn to wait,

and if you're lucky, you learn what waiting is

and what you have to give.

The Family Plot

I dig the earth with my hands,

claw stones with my nails,

sift ash through my fingers—

bone and tooth fragments

burned out by morning

spread on the ground.

The rain washes down

the smoldering mass below.

Our human flesh

the caustic ash

now together

turn to soap.

When I was asked by the minister of a local congregation if I would read my poetry on illness, death and dying as part of their Sunday service, I viewed it as an opportunity to facilitate a community's healing. The congregation had recently sustained a number of deaths, and the minister wanted to facilitate a dialogue among the congregants who were having difficulty talking about the losses. After reading “MeFather, What Waiting Is,” “The Family Plot,” and others (21), the congregation responded with testament of their own. Below in the poem “We All Sat Around in a Circle” I tried to capture the voices of the congregants.

We All Sat Around in a Circle

After the reading, twenty stayed.

A woman in a navy-blue suit spoke first:

“I remember”, she said, “when my mother died.

It was six months after we first found the lump.

Between the breast surgeries and the metastases

and the strokes, she was gone.

I yelled, “Do it now, Ma! Die now!”

but it took another month.”

Then a man:

“Sometimes they need to know it's O.K. to go.

My Dad was in coma for weeks.

He got agitated and made sounds,

but he couldn't talk.

The doctors said there wasn't much they could do.

‘He's terminal’, they said.

‘We'll just give him morphine

and make him comfortable.’

But my brother said, ‘No, not yet.’

And he and my sister and I got together and agreed

it was time for Dad to go…

so I was chosen.

I sat on the edge of the bed and held his hand.

I said, ‘Dad, It's O.K. We'll be O.K. without you.

If you want to go, it's all right,’

and I said it again and again,

and I swear he heard me

because in thirty minutes,

he was gone.”

Then a woman in her sixties:

“It's been nine years since my son died.

I was so passive…

When the doctors told us to leave the room

because they had to change the dressings,

I didn't say, ‘No, I'll stay.’

I just went…like they said.

I couldn't do him any good like that.

Then, when I was out of the room,

his heart stopped, and I wasn't there.

Nine years it's been.

I don't think I'll ever forgive myself.’

A man in his forties:

“My brother…he's paralyzed.

He's in a wheelchair…a gunshot wound

when he was sixteen.

He takes care of our Mom.

He does it all.

He washes for her.

He cooks.

He cuts watermelon.

He's a blessing, he is.

I just can't do it.

He blames me, but what can I do?

Some people just aren't cut out for it.”

Then another man about my age:

“I'm a little scared to say this,

but I have no story.

I don't cry.

When they're gone, they're gone…

nothing more.

I work in the movie business.

People come and go.

We can be close for six months,

work together every day,

then it's on to the next project.

I may never see them again.

That's what it was like

when my friend Ernie died…

like he's out there somewhere,

too involved with another project to call.

That's nothing unusual for Ernie.

Time just passes.

People say there's something wrong with me.

I don't know.

Sometimes I wonder.”

A man in his thirties:

“I've thought about it,

been in therapy over it,

processed it till I'm blue,

but in the end,

I still can't accept it.

In the end, she's still gone,

no matter how I work it out.

We were fifteen.

I've got children now.

I love my wife,

but my sister…

She was all of our heroes…

tall with dark red hair.

She drowned going after a ball.

I saw her go out, and I heard her yell.

When she went under,

I saw her.”

A silver-haired woman near fifty:

“The strange part for me

is thinking about the future.

My cancer was removed ten years ago.

Between the surgeries and the chemo

and the complications,

it was all I could do

to live day-to-day.

Now it's been ten years.

I'm beginning to believe

I have a future.

I've lost a lot of friends along the way,

but we were there for each other.”

and so it went—

around and around—

until we were done.

Then we hugged

and we touched.

Then we left.

For more on the ways in which poetry is employed as a therapeutic tool, you can refer to the following references (23–29).

A Note On Healing

In Chinese, the written character for poem is composed of two characters, one means word and the other means temple. Together they mean poem. The wisdom of poetry is in the combination of the sacred and the word as illustrated by the character in Chinese.

Healing is frequently thought of as taking place at the level of the individual. But if healing is viewed as a process that brings us back to wholeness, then in addition to happening within the individual patient, healing can also take place between patient and family members, between patient and the larger community of which they are a part, and even at the level of the community as a whole. In fact healing is often necessary on many of these levels simultaneously.

In many indigenous cultures, illness is viewed as the individual falling into disharmony with the community, so that in order to heal the individual, their place in the larger order must also be restored. In many West African indigenous cultures, proverbs are told in the oral tradition of poetry. Kykosa Kajangu from the Congo has collected these proverbs and integrated them into what he terms Wisdom Poetry (personal communication).

In one African tribe, when a woman is pregnant, the women of the community assemble in the forest and listen for the new child's song. When they hear it, they bring it back to the community and sing it in public. When the child is born, the song is sung again. When the child goes through ceremonial rites of puberty and marriage, it is sung again. And, when the child grows old and is dying, it is sung again. But, it is also sung when the child has broken with the community, committed a crime, or otherwise fallen out of harmony. The people tell themselves and each other who they are in the order of things, and can thereby bring themselves back into harmony with the world.

Poetry and Palliative Care

The healing concerns of palliative care do not reside only with the patients. The need to give voice to experiences at the end of life is shared by patients, families, caregivers and health care professionals, as well as the larger community, as illustrated in “We All Sat Around in a Circle.”

In 1996, during my father's terminal illness, a friend of mine contracted a nasal sinus cancer, which was thought to be benign. After several surgeries, all of which were too-little-too-late, the tumor spread into her skull and invaded her brain. The following set of poems includes “The Proof in the Pudding,” “The End Game,” and “The i in Poetry.” I was attempting to capture the experience of my friend's terminal illness and engage her in a dialogue of poetry (22).

The Proof in the Pudding

When last I left my friend Ruth Ellen,

the surgery to remove the frontal bone

left her with a step on her forehead.

When we went out, she wore hats.

Today I'll visit her in her room.

The tumor is no longer

benign.

In her head

in her eye

in what now appears to be

the end of her life

is my life.

The end game.

What a relief to know

all that is left is to live.

Time becomes pudding,

pudding air,

thick and everywhere.

These are the best times of our lives,

these pudding days of grace

when gardens are our guide.

They finally took her eye.

Don't mind.

They finally took her eye.

When I arrived at the house,

her daughter Molly gave me a hug.

She'd gone slightly stiff.

I walked in and looked out the back window.

The garden was beautiful and overgrown,

wet with new rain.

I almost missed her in her chair

at the table,

sitting there

eating avocado,

sliced and laid out flat.

She looked cute

in her bonnet and patch.

“Well”, she said,

“except for the eye

and the headaches

and there are still decisions to be made,

I'm fine.”

And it was her all over again

fine in the face of it

crabgrass roots deep

fine in her chair

a bonnet and patch

white like cotton

not hospital white

not bleached white

milky white like her

as we settled into our love

for one another.

Oh carry me wind

for I am air;

she's gonna lose her hair

I fear

she's gonna lose her hair

and hibiscus's blooms

and hummingbirds' wings

and deep dark earth held our future

as we shared the last bite of avocado.

Ruth Ellen rose

then retired to bed.

Her black cat waited

under the covers

after licking Ruth's plate.

I read them poetry.

We all tempted fate.

“What's that beeping?”

Her daughter appeared out of habit

and unkinked the IV.

“You and Susan and Josh,” Ruth said,

“all wonderful, all full,

all richly gifted.

I am gifted too,

but unrealized.

I always wanted to write,

I always wanted to paint,

I always wanted…”

“A friend brought me a journal.

I don't know if I'll write.

I don't know if I can.

Whenever I try,

it seems distant or removed.”

“You can”, I said.

“We will write poetry together.

You must start with your own spoken voice,

which is alive, not distant, here and now:

your house, your garden, the crabgrass, a bloom

the light playing through the leaves

the mud that kept you company in the living room.

You remember the last bite of avocado

creamy and green

a friend

your bonnet,

the beeping IV

Molly, kinked by your arm,

the cat black and close—

everything rich

and scented with you.

This is your poetry.

This is your life.”

The End Game

“I'm slipping Robert.”

Her voice trailed off my machine

just before the beep.

I went to the house to her room.

Her face looked like a pumpkin

swollen red and round as a plate.

Her left eye was gone.

She didn't wear a vanity patch anymore.

I kissed her on the cheek.

“I'm closing down,” she said,

“Getting ready to die.

Sometimes it scares me.

I'm shedding, like wings.

Sometimes I come out whole;

sometimes it's an onion.

Maybe I'm emerging.

Sometimes I feel it.”

“No, those are the wrong words.

It's not nothing.

It's something else.

You know me, Robert,

I don't get all mystical,

but something's happening.

I'm shedding from the inside.

It's all falling away—

beliefs, relationships—

all falling.”

“I know you're there if I need you,

but mostly I just want to sleep.

It's good you've come.

Dying's no big thing anymore,

It's a way to go.”

The i in Poetry

When I sat at my friend's side

while she was dying

and we wrote words like snow

and shed wings,

I was witness and scribe.

We wrote poetry together,

She and I.

We wrote poetry.

The poem “The End Game” was particularly meaningful to my father while he was dying. The poem “Cherish” tells this story.

Cherish

My father is scheduled for surgery tomorrow.

They're replacing the clogged artery in his leg

with a vein graft, also from his leg.

The incision will run from his groin

to his foot.

If they don't replace the artery,

the toe will turn gangrenous,

and he could die from infection.

If they cut off the toe,

the stump may not heal

from the lack of circulation,

so they have to replace the artery first,

and the artery in the other leg, well,

that can wait for now,

but it will need replacement too,

if he lives.

My father called the other day.

He told me a story from his childhood

about a man who owned a one horse shay.

The axle broke so

he took it to the blacksmith

to have it repaired.

The blacksmith told him it would cost as much

to repair the axle as it would to buy

a whole new wagon, to which the man replied,

“Well, if that's the case,

then they should build them

so all the parts break at once.”

“That's what's happening to me,”

said my father, and I knew

he was looking at his life straight

and he could feel his death coming.

“Yes,” he said, “I feel things closing down

and falling away,

and I wonder if it means I'm dying…

that this is what dying is…

things falling away.”

I read him the poem “The End Game”,

when Ruth Ellen tells me she's

“closing down…getting ready to die…

I'm shedding like wings…

beliefs, relationships…

all falling.”

“Yes,” he said,

“maybe it's the same.”

“The Legacy” came out of the poetry and brain cancer project discussed earlier. In it, a wife of 25 years speaks of her role as caregiver (2).

The Legacy

I felt frozen at first.

As things went worse for his body

there was a kind of condensation—

like distilling our future into a very tiny space.

Everything became condensed into moments

of closeness.

I became a better person.

I stretched.

Sometimes I wanted to sleep.

Sometimes I wanted to hide.

I was overwhelmed.

I was envious of people.

The humor we shared wasn't about jokes.

It was about being silly.

You can't be silly with just anyone.

It's a real loss.

I knew the minute he died.

It was like he shrunk into his body.

The soul may linger for a while,

But it didn't linger in that body.

What was left was left in our hearts,

not in the bed.

I came up with this amazing idea

That everything now is surreal,

And the surreal is the new reality.

I just thought of something wonderful.

No matter how long we were together,

There was always more.

I wrote a poem.

Here are a few lines.

Nothing of love is ever lost.

You take each other in.

Where you're molded and remolded

And become yourself again.

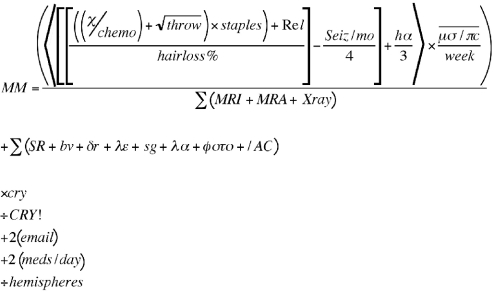

The poetry and brain cancer project also produced poetry that presented a different sort of perspective. “Median Mortality” by Toby Estler is an example of the humor and courage displayed by people faced with terminal illness (2).

Median Mortality

The first question most brain cancer patients ask is,

How long do I have to live?

I'll tell you how to Figure it out.

First, think of a number. Any number.

Divide that by the number of your scheduled chemo

treatments.

Add that to the square root of the amount of times

you throw up each week.

Multiply by the number of staples required

to reattach your skull.

Now, this is where it gets a little tricky …

Add the number of your surviving relatives

(Immediate family only please. Cousins skew

the results.)

Divide by your estimated percentage hair loss.

If you anticipate wearing a wig—

I'm sorry, cranial prosthesis— please disregard this

section of the equation.

Subtract one quarter of the number of seizures per month.

Add a third of the headaches (cluster headaches

are not considered eligible.)

Multiply by the average amount of mood swings

and/or personality changes in a week.

Divide by the total number of MRI's, MRA's, and X-rays;

add this to the combined sum of skin rashes,

episodes of blurred vision, drowsiness,

lost erections, swollen gums, lost appetite,

photosensitivity, and/or abdominal cramps.

Multiply by the amount of times you cry.

Divide by the amount of times you want to cry.

Add the number of people in your email support group.

Add twice the number of medications taken daily.

Divide by the number of hemispheres in your brain

(if uncertain, use 2).

There you have it.

An accurate and realistic assessment of your life expectancy.

We call it median mortality.

And don't worry if you don't understand it—

math can be a real killer.

In a soon-to-be published paper, Jack Coulehan and Patrick Clary, Journal of Palliative Medicine in press write about the need for professionals who work in palliative care to be able to process their own experience, specifically using poetry. John Fox writes of this need amongst hospice care givers to find their own voices in the work they do (23,24). Gregory Gross discusses the need to deconstruct death from his Scientific Medicalization to a more poetic remystification of the process of dying (30). The Man With a Hole in His Face (31) by Jack Coulehan is a dramatic example of a physician trying to come to grips with his own reactions to the reality of this patient.

The Man With a Hole in His Face

He has the lower part,

a crescent of face

on the right, and an eye

that sits precipitously

beside the moist hole

where the rest of his face was.

The hole is stuffed

with curls of gauze.

His nurse comes before dawn,

at the moment

the eye fears for its balance,

and fills the wound,

sculpting a tortured landscape

of pack ice.

The man's eye does not close

because any blink

is death,

nor does the eye rest

in mine

when I ask the questions

he is weary of answering.

While I wait here quietly

in arctic waste,

the pack ice cracks

with terrifying songs

and over the moist hole

where the rest of his face was,

he rises.

This man is the man in the moon.

The Experimental Evidence

Most of the experimental evidence as to the efficacy of Poetry Therapy comes through the literature on expressive writing. The seminal researcher in the field of the therapeutic uses of expressive writing is James Pennebaker (32,33). Pennebaker has shown that the use of expressive writing for as little as 15 min over 4 days has positive health effects as measured by visits to physicians and a diminution of symptom complaints. His original work deals with the use of expressive writing to heal wounds from traumatic stressful events.

Pennebaker's argument and the evidence for the efficacy of expressive writing is well stated in his most recent book Writing to Heal: A Guided Journal for Recovering from Trauma and Emotional Upheaval (33). In it he summarizes his argument for the therapeutic effects of expressive writing on the immune system (34); medical health markers with asthma, cancer, and arthritis patients (35); and decreased physiological stress indicators in the form of lower muscle tension, drops in perspiration levels, and lower blood pressure and heart rate levels. (36) He also summarizes the evidence for the psychological benefits of expressive writing in terms of positive short and long-term mood changes (37) and behavioral effects in the form of school and work performance. (38,39,40)

Findings from numerous experiments have suggested that writing exercises can give a whole array of health benefits including reductions in emotional and physical health complaints (37,41,42), and enhanced social relationships and role functioning (43).

On the other hand not all investigators have found positive effects using writing, and not all people who wrote showed positive benefits (35). Some writers have shown skepticism (44).

In 2002, Lepore and Smyth published The Writing Cure: How Expressive Writing Promotes Health and Well-Being (34), which is the most comprehensive review to date on the research into the efficacy of expressive writing. It presents cutting edge theory and research, and points students and scientist to new avenues of investigation. It also presents how clinicians are beginning to translate basic research into practical applications. The book is divided into four sections: 1. an overview; 2. the therapeutic effects of expressive writing and adjustment to life stressors (including work with cancer patients, expressive writing and blood pressure, working with children and alexithymia); 3. emotional, cognitive and biological processes; and 4. new directions and clinical applications.

Overall, the research on poetry therapy in general and expressive writing in particular is promising. Recognizing the need for additional research, the National Association for Poetry Therapy (NAPT) and Lapidus (the Association for the Literary Art in Personal Development) located in London are planning a multi-center research study on the efficacy of Poetry Therapy with cancer patients. Also, NAPT is embarking on a multi-center clinical research study attempting to assess the efficacy of Poetry Therapy on post-traumatic stress disorder in war veterans (see NAPT below).

In Conclusion

I hope you've enjoyed the ride. If you've gotten this far, you've certainly had some kind of experience. You may or may not understand it, but ask yourself whether you have a better sense of being in the dialogue on illness, death and dying. How do you already use your capacities for poetic expression in working through these questions? If on the other hand, you just skipped directly to this conclusion, here's something for you too.

The first fiddle in the Philharmonic

Was late for a concert, so

He hailed a cab.

“Tell me sir”, he said,

“What's the best way to get to

Carnegie Hall?” to which the cabbie replied,

“Practice, practice, practice.”

And so it is.

Whether it's the practice of medicine

or the practice of yoga

or the practice of using

the healing powers of poetry,

it is a practice that must be done

again and again and again.

I'll close with a quote from Yogi Berra,

The difference between

Theory and practice

Is that in theory

They are the same,

But in practice

They are not.

Afterword

What I want is not words

But where words come from

The space within breath

That calls out our tongue.

Resources: The National Association for Poetry Therapy

According to the NAPT, the definition of Poetry Therapy is the intentional use of the written and spoken word to facilitate healing, growth and transformation. The NAPT has been in existence since 1982. It's predecessor was The National Association for Bibliotherapy. A survey of the membership reveals an interesting 25% split. Twenty-five percent of the members are mental health providers (psychologists, social workers, family counselors, etc.), 25% are medically trained physicians, nurses, etc., 25% are educators, and the last 25% are an assortment of artists, writers, building contractors and race car drivers, etc., who also share an interest in the healing power of poetry. NAPT has a training program in poetry therapy and an academic journal, Journal of Poetry Therapy. Please refer to the web site for details. www.poetrytherapy.org.

Figure 1.

Median mortality equation.

References

- 1.Williams WC. The Collected Poems of William Carlos Williams, Vol. II (1939–1962) New York: New Directions Books; 2001. Asphodel, That Greeny Flower. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Carroll R, editor. The Art of the Brain: Twelve Portraits. Los Angeles, CA: Bombshelter Press; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Metzger D. Writing for Your Life. San Francisco, CA: Harper Collins; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Metzger D. Tree. Berkeley, CA: North Atlantic Books; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Metzger D. Entering the Ghost River. Topanga, CA: Hand to Hand; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wagner S. The Andrew Poems. Lubbock, TX: Texas Tech University Press; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Silver A. Bare Root: a Poets Journey with Breast Cancer. Los Angeles, CA: Terrapin Press; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Carroll R. What Waiting Is. Los Angeles, CA: InCorpus Press; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gaetzman S. Blood Sugar. Los Angeles, CA: Last Leg Publishing; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kaufman J. Passion and Shadow, the Lights of Brain Cancer. Los Angeles, CA: Bombshelter Press; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Writing as a Healing Art (special section) Poets and Writers Magazine. 2001. May–June. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Spann C, editor. Poet Healer: Contemporary Poems for Health and Healing. Sacramento, CA: Sutter's Lamp; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Charach R, editor. The Naked Physician: Poems about the Lives of Patients and Doctors. Kingston, Ontario, Canada: Quarry Press; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Belli A, Coulehan J., editors. Blood and Bone: Poems by Physicians. Iowa City, Iowa: University of Iowa Press; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Campo R. The Healing Art: A Doctor's Black Bag of Poetry. New York, N.Y.: W.W. Norton & Co.; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Campo R. The Poetry of Healing: A Doctor's Education in Empathy, Identity and Desire. New York, N.Y.: W.W. Norton & Co.; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Campo R. What the Body Told. Durham, N.C.: Duke University Press; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Coulehan J. Medicine Stone. Santa Barbara, CA: Fithian Press; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sakhi S. I AM Both. Westwood, CA: Crow Press; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Alvarez A. The Writer's Voice. New York, N.Y.: W.W. Norton & Co.; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Carroll R. Cherish. Los Angeles, CA: InCorpus Press; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Adams K. Journal to the Self. New York, N.Y.: Warner Books; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fox J. Finding What You Didn't Lose: Expressing Your Truth and Creativity Through Poem-Making. New York, N.Y.: Jeremy P. Tarcher/Putnam; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fox J. Poetic Medicine: The Healing Art of Poem-Making. New York, N.Y.: Jeremy P. Tarcher/Putnam; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mazza N. Poetry Therapy Theory and Practice. New York, N.Y.: Brunner-Routledge; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Integrative Medicine Packet. 2004. The National Association for Poetry Therapy web site www.poetrytherapy.org (click on What's New)

- 27.Chavis G, Weisberger L, editors. The Healing Fountain: Poetry Therapy for Life's Journey. St. Cloud, MN: North Star Press of St. Cloud, Inc.; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 28.van Meenen K, Rossiter C. Giving Sorrow Words: Poems of Strength and Solice. Des Moines, Iowa: National Association for Poetry Therapy Foundation; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Leedy J, editor. Poetry as Healer: Mending the Troubled Mind. New York, N.Y.: The Vanguard Press; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gross G. Deconstructing Death. Journal of Poetry Therapy. 2003;16(2):71–81. June. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Coulehan J. First Photographs of Heaven. Troy, Maine: Nightshade Press; 1991. The Man With a Hole In His Face. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pennebaker JW. Opening Up: The Healing Power of Expressing Emotions. New York, N. Y.: Guilford Press; 1997. Revised Edition. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pennebaker JW. A Guided Journal for Recovering from Trauma and Emotional Upheaval. Oakland, CA: New Harbinger Publications, Inc.; 2004. Writing to Heal: [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lepore S, Smyth J. The Writing Cure: How Expressive Writing Promotes Health and Emotional Well-Being. Washington, D.C: American Psychological Association; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Smyth JM, Stone AA, Hurewitz A, Kaell A. Effects of writing about stressful experiences on symptom reduction in patients with asthma or rheumatoid arthritis: A randomized trial. JAMA: Journal of the American Medical Association. 1999;281:1304–1309. doi: 10.1001/jama.281.14.1304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pennebaker JW, Hughes CF, O'Heeron RC. The psycho-physiology of confession: Linking inhibitory and psychosomatic processes. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1987;52:781–793. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.52.4.781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lepore SJ. Expressive writing moderates the relation between intrusive thoughts and depressive symptoms. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1997;73:1030–1037. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.73.5.1030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cameron LD, Nicholls G. Expression of stressful experiences through writing: Effects of a self-regulation manipulation for pessimists and optimists. Health Psychology. 1998;17:84–92. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.17.1.84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lumley MA, Provenzano KM. Stress management through emotional disclosure improves academic performance among college students with physical symptoms. Journal of Educational Psychology. 2003;95:641–649. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Klein K, Boals A. Expressive writing can increase working memory capacity. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General. 2001;130:520–533. doi: 10.1037//0096-3445.130.3.520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Greenberg MA, Stone AA, Wortman CB. Health and psychological effects of emotional disclosure: A test of the inhibition-confrontation approach. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1996;71:588–602. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.71.3.588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Pennebaker JW, Colder M, Sharp LK. Accelerating the coping process. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1990;58:528–537. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.58.3.528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Spera SP, Buhrfeind ED, Pennebaker JW. Expressive writing and coping with job loss. Academy of Management Journal. 1994;37:722–733. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Greenlaugh T. Writing as therapy. British Medical Journal. 1999;319:270–271. [Google Scholar]