Abstract

Background

Patients with suspected mpox presented to different venues for evaluation during the 2022 outbreak. We hypothesized that practice patterns may differ across venue of care.

Methods

We conducted an observational study of patients undergoing mpox testing between 1 June 2022 and 15 December 2022. We assessed concomitant sexually transmitted infection (STI) testing, sexual history, and anogenital examination and a composite outcome of all 3, stratified by site. Venue of care was defined as ED (emergency department or urgent care), ID (infectious disease clinic), or PCP (primary care or other outpatient clinic).

Results

Of 276 patients included, more than half (62.7%) were evaluated in the ED. Sexual history, anogenital examination, and STI testing were documented as performed at a higher rate in ID clinic compared to ED or PCP settings. STIs were diagnosed in 20.4% of patients diagnosed with mpox; syphilis was the most common STI among patients diagnosed with mpox (17.5%). Patients evaluated in an ID clinic had higher odds ratio of completing all 3 measures (adjusted odds ratio, 3.6 [95% confidence interval, 1.4–9.3]) compared to PCP setting adjusted for age, gender, and men who have sex with men status. Cisgender men who have sex with men, transgender males, and transgender females had higher odds ratio of completing all 3 measures compared to cisgender females (adjusted odds ratio, 4.0 [95% confidence interval, 1.9–8.4]) adjusted for age and venue of care.

Conclusions

Care varied across clinical sites. ID clinics performed a more thorough evaluation than other venues. Rates of STI coinfection were high. Syphilis was the most common STI. Efforts to standardize care are important to ensure optimal outcomes for patients.

Keywords: Coinfection, mpox, orthopoxvirus, quality of care, sexually transmitted infections

Evaluation of patients with suspected mpox differed by care site. Coinfection with STI was common among patients tested for mpox and syphilis was the most frequent STI diagnosed. MSM status was associated with completion of guideline concordant care.

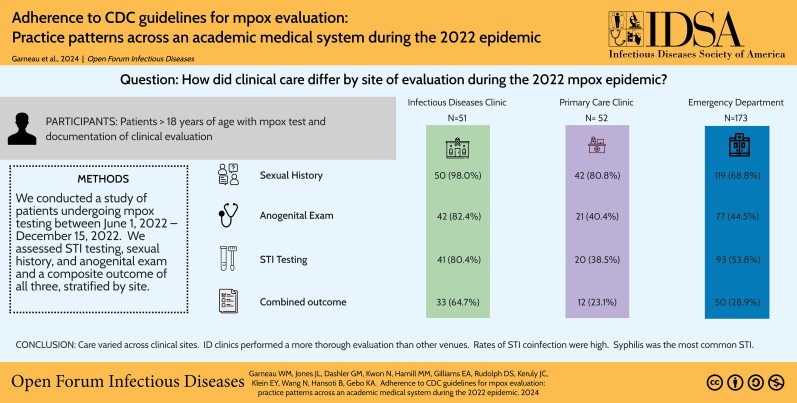

Graphical Abstract

Graphical Abstract.

In 2022, a worldwide outbreak of mpox virus occurred in which tens of thousands of persons were infected with the virus [1]. This was declared a Public Health Emergency of International Concern by the World Health Organization [2]. Previously known as monkeypox, mpox is a pox virus related to smallpox and is endemic to areas of central and west Africa, typically resulting in limited outbreaks [3]. During the 2022 worldwide outbreak transmission of the virus predominantly occurred through sexual contact among men who have sex with men (MSM) and approximately 40% of mpox diagnoses occurred in people with HIV (PWH) [4–6]. Concomitant sexually transmitted infections (STIs) were diagnosed at high rates and the majority of patients presented with anogenital lesions [5, 7]. Given this association with sexual activity, the Centers For Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recommendations for evaluation of suspected mpox includes obtaining a sexual history, performing a physical examination, and undertaking diagnostic testing for STIs [8]. Similar recommendations are made by the Infectious Diseases Society of America [9]. However, clinicians may not always obtain a detailed sexual history or perform a genitourinary examination and providers may not be aware of the importance of testing for concomitant STIs [10–12]. Additionally, patients may be reluctant to discuss sensitive topics or consent to be examined, leading to gaps in care [13].

During the 2022 outbreak, patients with suspected mpox infection presented for evaluation in a variety of clinical contexts including emergency departments, primary care clinics, and sexual health and infectious diseases (ID) clinics. Prior work has recognized differences in clinical practice patterns among specialists in evaluating various medical conditions including STIs [14] and inconsistent testing for STIs among patients with suspected mpox [15]. We hypothesized that the care patterns for people presenting with possible mpox may differ depending on the location of patient presentation. This study sought to characterize the clinical evaluation of mpox across clinical care venues in a single academic health system.

METHODS

We performed a retrospective observational cohort study of patients visiting the Johns Hopkins Health System (JHHS) between 1 June 2022 and 15 December 2022. The JHHS includes 5 hospitals in the Baltimore/Washington, DC, metropolitan area and more than 40 outpatient clinical sites, serving a diverse community of patients in the Mid-Atlantic region of the United States. The study was reviewed by the Johns Hopkins School of Medicine institutional review board and approved under a waiver of consent (IRB00347138).

Inclusion criteria were patients ≥ 18 years of age, documented mpox test with results reported within JHHS, and available documentation of the clinical encounter. Patients with mpox testing but without accessible clinical documentation through the JHHS electronic medical record were not included. The beginning and end dates for the study represent when the earliest cases were reported and when testing became infrequent (<10 tests/month). The venue of clinical evaluation was obtained via chart review and defined as sexual health clinic, emergency department, urgent care, primary care, obstetrics and gynecology, dermatology, ID clinic, pediatrics clinic, and other ambulatory care. Venues were combined for purposes of analysis as follows: ID or sexual health clinic (ID), adult internal medicine, pediatrics, obstetrics and gynecology, dermatology clinic, or other ambulatory care (primary care provider [PCP]), and urgent care or emergency department (ED).

The primary, composite, outcome was documentation of the CDC recommendations [16] for mpox evaluation including (1) an anogenital examination, (2) sexual history, and (3) comprehensive STI testing. Anogenital examination and sexual history were defined complete if performed at index visit or visit when symptoms started. Sexual history was documented completed if at least 1 of the following were completed: sexual partners within the last month, gender of sex partners, sexual protection used, or type of sex were documented. STI testing was defined as nucleic acid amplification testing for gonorrhea and chlamydia; syphilis screening; and/or HIV screening (if not a PWH) performed within 7 days before or 30 days following mpox evaluation. Secondary outcomes included individual completion of the 3 items listed previously.

Data on patient demographics and visits were bulk extracted from the Infectious Disease Precision Medicine Center of Excellence: a Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act–compliant clinical data warehouse of electronic medical record information by experienced data scientists (N.K., E.K.). Data were validated through clinical chart review (J.L.J., G.M.D., W.M.G.).

Demographics including age at time of evaluation, sex at birth, race, and ethnicity were obtained from the electronic health record. Gender identity, sexual orientation, location of clinical examination, documentation of anogenital examination, sexual history, and insurance status were manually abstracted by chart review (J.L.J., G.M.D., D.S.R., M.M.H., E.A.G., J.C.K., B.H., W.M.G.). Procedure codes were used to identify completed mpox and STI testing.

Documentation of anogenital examination was considered completed if either anal or genital examination was documented in the note associated with the encounter where mpox testing was conducted. Sexual history was defined as completed if sexual orientation and/or gender of sex partners within the last month were reported and marked as incomplete if both these features were not present. Procedure codes were used to electronically identify gonorrhea, chlamydia, syphilis, and HIV tests completed within the JHHS. Mpox samples were processed using polymerase chain reaction (PCR; sample dates 1 June 2022–31 July 2022; Johns Hopkins Department of Pathology Laboratory Developed Test, Applied Biosystems 7500 PCR, Waltham, MA, USA; sample dates 1 August 2022–15 December 2022 NeuMoDx, Ann Arbor, MI, USA). Gonorrhea and chlamydia testing used nucleic acid amplification testing from oropharyngeal, rectal, urine, and/or cervicovaginal samples (Cobas 6800, Roche, Indianapolis, IN, USA). Testing for syphilis was performed via reverse sequence serological testing comprising chemiluminescence assay (Diasorin, Saluggia, Italy), reflexed to Rapid Plasma Reagin (Sure-Vue, Thermo Fisher, Waltham, MA, USA), and treponema pallidum particle agglutination (Serodia, Tokyo, Japan) as a tiebreaker. HIV screening was conducted via serologic antigen/antibody HIV tests (Elecsys HIV Duo, Roche, Indianapolis, IN) and/or viral load testing by PCR (cobas 6800, Roche). All samples were processed as part of routine clinical care. Available results were automatically captured by electronic query. Charts were reviewed for all patient tests with rapid plasma reagin (RPR) of ≥ 1:4 and a new diagnosis was determined by a new positive serological test result or a 4-fold increase in RPR titer. Only laboratory testing completed within the JHHS was included. Data were provisioned as a comma-separated value file and imported into REDCap [17, 18]. Statistical analysis was performed in Stata (Stata Statistical Software: Release 18, StataCorp LLC, College Station, TX, USA).

Sex at birth, gender identity, race, ethnicity, sexual orientation, insurance status, and HIV status were described as categorical variables and age was described as a continuous variable. Categorical variables were compared using Pearson χ2 and Fisher exact tests as appropriate. To explore the effect of age on the combined outcome, we performed locally weighted scatterplot smoothing. Guided by this exploratory finding, we used linear spline with a knot at age 30 years to model the relationship between age and the combined outcome in logistic regression.

We tested the association of venue of care and anogenital examination, sexual history, and STI testing using univariable and multivariable logistic regression. We analyzed age, sex at birth, race, HIV status, and MSM status for association with the primary outcome. Covariates identified as associated with the combined outcome were included in the multivariable logistic regression model to determine the association of venue of care with completion of the combined outcome. We used Likelihood Ratio Test and the Akaike Information Criterion to assess goodness of fit of various models. A 2-sided alpha level of 0.05 was used for assessing the significance of statistical tests.

RESULTS

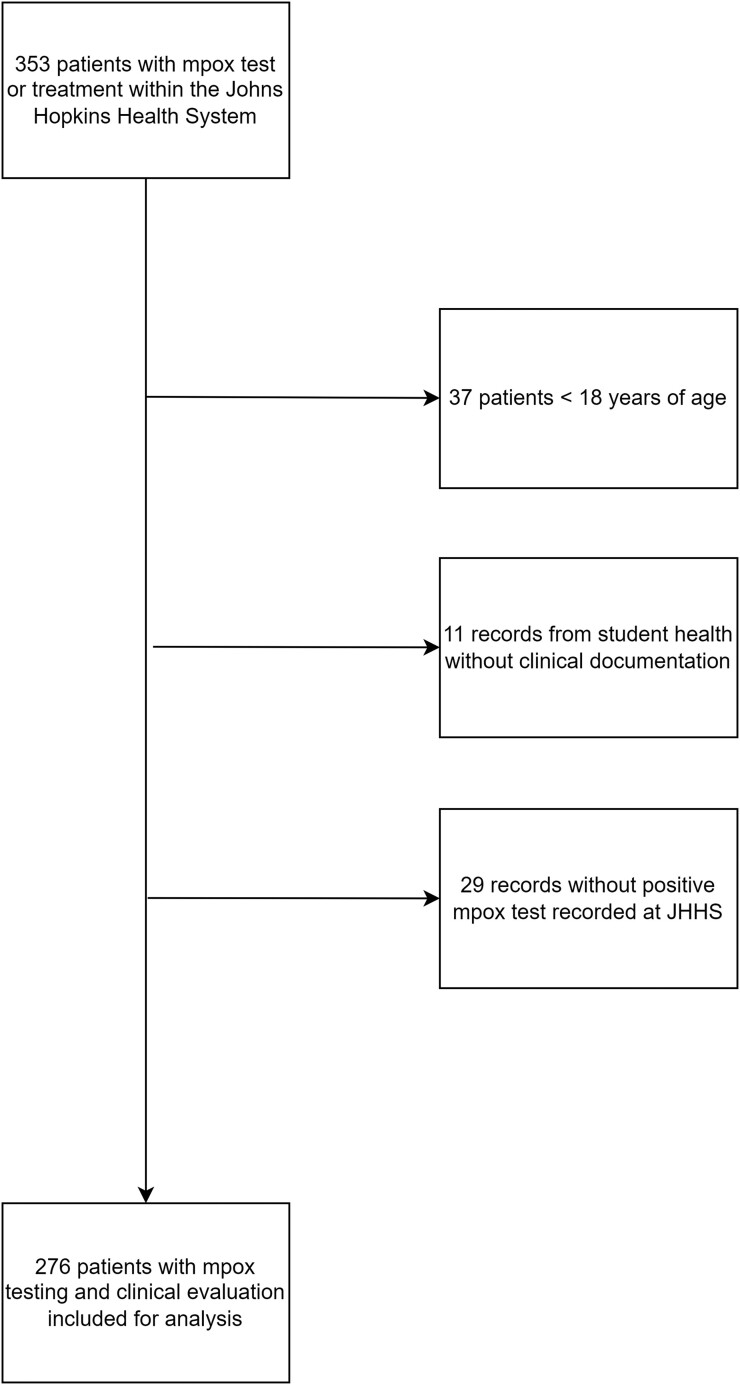

A total of 353 patient records were identified by electronic query with testing or treatment for mpox. Twenty-nine patients were excluded because there was no mpox test recorded in the Infectious Disease Precision Medicine Center of Excellence, 37 persons were excluded because of being age < 18 years, and 11 patients from student health were excluded because no clinical records were available. After exclusions, 276 patients met inclusion criteria and were analyzed (Figure 1). The mean age was 41.2 years (range, 18.1–93.7) and two thirds (66.3%) were male at birth (Table 1). Approximately half of the patients were Black (49.6%) and a minority (8.0%) identified as Hispanic or Latino. A total of 50.7% identified as heterosexual, 29.7% as gay, and 7.2% as bisexual. More than one third of patients had private insurance (37.3%) or Medicaid (35.9%). Most (62.7%) were evaluated in the ED setting, whereas 18.8% were evaluated in a PCP clinic and 18.5% in ID setting. Approximately one quarter of patients (23.9%) were living with HIV; however, 88.2% of those evaluated in the ID clinic were PWH. Approximately one quarter of mpox tests performed were positive (26.4%), with the highest positivity in the ID setting (51.0%).

Figure 1.

Identification of patients with mpox test and clinical evaluation within the Johns Hopkins Health System 1 June 2022—15 December 2022.

Table 1.

Demographics and Clinical Characteristics of Patients Evaluated for mpox by Site

| Diagnosis Site | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | ID | PCP | ED | Test | |

| N | 276 | 51 (18.5%) | 52 (18.8%) | 173 (62.7%) | |

| Age (mean) | 41.2 | 40.8 | 42.4 | 40.9 | .649 |

| Sex at birth | |||||

| Female | 93 (33.7%) | 3 (5.9%) | 31 (59.6%) | 59 (34.1%) | <.001 |

| Male | 183 (66.3%) | 48 (94.1%) | 21 (40.4%) | 114 (65.9%) | |

| Gender identity | |||||

| Cis-gender female | 91 (33%) | 3 (5.9%) | 29 (55.8%) | 59 (34.1%) | <.001 |

| Cis-gender male | 179 (64.9%) | 47 (92.2%) | 19 (36.5%) | 113 (65.3%) | |

| Transgender female | 4 (1.4%) | 1 (2.0%) | 2 (3.8%) | 1 (0.6%) | |

| Transgender male | 1 (0.4%) | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (1.9%) | 0 (0.0%) | |

| Other | 1 (0.4%) | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (1.9%) | 0 (0.0%) | |

| Race | |||||

| Black or African American | 137 (49.6%) | 29 (56.9%) | 28 (53.8%) | 80 (46.2%) | .120 |

| Asian | 12 (4.3%) | 1 (2.0%) | 1 (1.9%) | 10 (5.8%) | |

| White | 92 (33.3%) | 11 (21.6%) | 19 (36.5%) | 62 (35.8%) | |

| American Indian or Alaska Native | 1 (0.4%) | 1 (2.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | |

| Other | 30 (10.9%) | 7 (13.7%) | 3 (5.8%) | 20 (11.6%) | |

| Choose not to disclose | 4 (1.4%) | 2 (3.9%) | 1 (1.9%) | 1 (0.6%) | |

| Ethnicity | |||||

| Hispanic or Latino | 22 (8.0%) | 4 (7.8%) | 1 (1.9%) | 17 (9.8%) | .018 |

| Not Hispanic or Latino | 247 (89.5%) | 44 (86.3%) | 48 (92.3%) | 155 (89.6%) | |

| Unknown | 7 (2.5%) | 3 (5.9%) | 3 (5.8%) | 1 (0.6%) | |

| Sexual orientation | |||||

| Heterosexual | 140 (50.7%) | 9 (17.6%) | 33 (63.5%) | 98 (56.6%) | <.001 |

| Bisexual | 20 (7.2%) | 7 (13.7%) | 3 (5.8%) | 10 (5.8%) | |

| Gay | 82 (29.7%) | 33 (64.7%) | 11 (21.2%) | 38 (22.0%) | |

| Lesbian | 2 (0.7%) | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (1.9%) | 1 (0.6%) | |

| Queer | 1 (0.4%) | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (1.9%) | 0 (0.0%) | |

| Choose not to disclose | 2 (0.7%) | 1 (2.0%) | 1 (1.9%) | 0 (0.0%) | |

| Unknown | 29 (10.5%) | 1 (2.0%) | 2 (3.8%) | 26 (15.0%) | |

| Insurance status | |||||

| Uninsured | 28 (10.1%) | 4 (7.8%) | 1 (1.9%) | 23 (13.3%) | .015 |

| Medicare | 34 (12.3%) | 2 (3.9%) | 9 (17.3%) | 23 (13.3%) | |

| Medicaid | 99 (35.9%) | 17 (33.3%) | 17 (32.7%) | 65 (37.6%) | |

| Private insurance | 103 (37.3%) | 27 (52.9%) | 24 (46.2%) | 52 (30.1%) | |

| Unknown | 12 (4.3%) | 1 (2.0%) | 1 (1.9%) | 10 (5.8%) | |

| Persons with HIV | |||||

| Yes | 66 (23.9%) | 45 (88.2%) | 3 (5.8%) | 18 (10.4%) | <.001 |

| No | 206 (74.6%) | 6 (11.8%) | 49 (94.2%) | 151 (87.3%) | |

| Unknown | 4 (1.4%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 4 (2.3%) | |

| Positive MPX | |||||

| Yes | 73 (26.4%) | 26 (51.0%) | 8 (15.4%) | 39 (22.5%) | <0.001 |

| No | 203 (73.6%) | 25 (49.0%) | 44 (84.6%) | 134 (77.5%) | |

Abbreviations: ED, emergency department; ID, infectious diseases; MPX, mpox; PCP, primary care provider.

Analysis by venue demonstrated differences in completion of sexual health metrics (Table 2). Sexual history was documented in 98.0% of ID encounters compared to 80.8% in PCP encounters and 68.8% of ED encounters (P value <.001). Anogenital examination was documented in 82.4% of ID visits, 40.4% of PCP visits, and 44.5% of ED visits (P <.001) (Table 2). STI testing was performed in 80.4% of ID clinic visits compared to 38.5% of PCP visits and 53.8% of ED visits (P <.001). Similar trends were demonstrated for ID clinics, ED, and PCP clinics for gonorrhea testing (72.5% vs 23.1% vs 32.4%; P <.001), and chlamydia testing (70.6% vs 23.1% vs 32.9%; P <.001), syphilis testing (51.0% vs 23.1% vs 41.6%; P = .01), extragenital gonorrhea test (66.7% vs 11.5% vs 6.9%; P <.001), and extragenital chlamydia test (64.7% vs 11.5% vs 7.5%; P <.001). Among patients who tested positive for mpox, extragenital gonorrhea was tested in 69.2% of ID clinic visits compared to 37.5% of ED visits and 17.9% of PCP visits (P <.001) and extragenital chlamydia was tested in 69.2% of ID clinic visits compared to 37.5% of ED visits and 20.5% of PCP visits (P <.001). All other sexual health metrics were completed at a similar rate by venue among patients who tested positive for mpox.

Table 2.

Elements of Care Performed as Part of mpox Evaluation by Clinical Site

| All Patients | Patients With Positive mpox Test | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Diagnosis Site | Diagnosis Site | |||||||||

| Total | ID | PCP | ED | P value | Total | ID | PCP | ED | P value | |

| N | 276 | 51 (18.5%) | 52 (18.8%) | 173 (62.7%) | 73 | 26 (35.6%) | 8 (11.0%) | 39 (53.4%) | ||

| Sexual history performed | <.001 | .091 | ||||||||

| Yes | 211 (76.4%) | 50 (98.0%) | 42 (80.8%) | 119 (68.8%) | 66 (90.4%) | 26 (100.0%) | 7 (87.5%) | 33 (84.6%) | ||

| No | 65 (23.6%) | 1 (2.0%) | 10 (19.2%) | 54 (31.2%) | 7 (9.6%) | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (12.5%) | 6 (15.4%) | ||

| Anogenital examination performeda | <.001 | .136 | ||||||||

| Yes | 140 (50.7%) | 42 (82.4%) | 21 (40.4%) | 77 (44.5%) | 55 (75.3%) | 22 (84.6%) | 4 (50.0%) | 29 (74.4%) | ||

| No | 136 (49.3%) | 9 (17.6%) | 31 (59.6%) | 96 (55.5%) | 18 (24.7%) | 4 (15.4%) | 4 (50.0%) | 10 (25.6%) | ||

| Any STI test performedb | <.001 | .716 | ||||||||

| Yes | 154 (55.8%) | 41 (80.4%) | 20 (38.5%) | 93 (53.8%) | 54 (74.0%) | 20 (76.9%) | 5 (62.5%) | 29 (74.4%) | ||

| No | 122 (44.2%) | 10 (19.6%) | 32 (61.5%) | 80 (46.2%) | 19 (26.0%) | 6 (23.1%) | 3 (37.5%) | 10 (25.6%) | ||

| Any gonorrhea test | <.001 | .223 | ||||||||

| Yes | 105 (38.0%) | 37 (72.5%) | 12 (23.1%) | 56 (32.4%) | 47 (64.4%) | 20 (76.9%) | 4 (50.0%) | 23 (59.0%) | ||

| No | 171 (62.0%) | 14 (27.5%) | 40 (76.9%) | 117 (67.6%) | 26 (35.6%) | 6 (23.1%) | 4 (50.0%) | 16 (41.0%) | ||

| Any chlamydia test | <.001 | .268 | ||||||||

| Yes | 105 (38.0%) | 36 (70.6%) | 12 (23.1%) | 57 (32.9%) | 48 (65.8%) | 20 (76.9%) | 4 (50.0%) | 24 (61.5%) | ||

| No | 171 (62.0%) | 15 (29.4%) | 40 (76.9%) | 116 (67.1%) | 25 (34.2%) | 6 (23.1%) | 4 (50.0%) | 15 (38.5%) | ||

| Extragenital gonorrhea test | <.001 | <.001 | ||||||||

| Yes | 52 (18.8%) | 34 (66.7%) | 6 (11.5%) | 12 (6.9%) | 28 (38.4%) | 18 (69.2%) | 3 (37.5%) | 7 (17.9%) | ||

| No | 224 (81.2%) | 17 (33.3%) | 46 (88.5%) | 161 (93.1%) | 45 (61.6%) | 8 (30.8%) | 5 (62.5%) | 32 (82.1%) | ||

| Extragenital chlamydia test | <.001 | <.001 | ||||||||

| Yes | 52 (18.8%) | 33 (64.7%) | 6 (11.5%) | 13 (7.5%) | 29 (39.7%) | 18 (69.2%) | 3 (37.5%) | 8 (20.5%) | ||

| No | 224 (81.2%) | 18 (35.3%) | 46 (88.5%) | 160 (92.5%) | 44 (60.3%) | 8 (30.8%) | 5 (62.5%) | 31 (79.5%) | ||

| Syphilis testing performed | .011 | .107 | ||||||||

| Yes | 110 (39.9%) | 26 (51.0%) | 12 (23.1%) | 72 (41.6%) | 40 (54.8%) | 13 (50.0%) | 2 (25.0%) | 25 (64.1%) | ||

| No | 166 (60.1%) | 25 (49.0%) | 40 (76.9%) | 101 (58.4%) | 33 (45.2%) | 13 (50.0%) | 6 (75.0%) | 14 (35.9%) | ||

| HIV test performedc | .208 | .966 | ||||||||

| Yes | 77 (36.7%) | 4 (66.7%) | 15 (30.6%) | 58 (37.4%) | 17 (47.2%) | 1 (50.0%) | 3 (42.9%) | 13 (48.1%) | ||

| No | 133 (63.3%) | 2 (33.3%) | 34 (69.4%) | 97 (62.6%) | 19 (52.8%) | 1 (50.0%) | 4 (57.1%) | 14 (51.9%) | ||

| Combined outcomed | <.001 | .038 | ||||||||

| Yes | 95 (34.4%) | 33 (64.7%) | 12 (23.1%) | 50 (28.9%) | 40 (54.8%) | 16 (61.5%) | 1 (12.5%) | 23 (59.0%) | ||

| No | 181 (65.6%) | 18 (35.3%) | 40 (76.9%) | 123 (71.1%) | 33 (45.2%) | 10 (38.5%) | 7 (87.5%) | 16 (41.0%) | ||

Abbreviations: ED, emergency department; ID, infectious diseases; PCP, primary care provider; STI, sexually transmitted infection.

aExamination performed at index visit or immediately before index visit.

bIncludes any person with at least 1 gonorrhea, chlamydia, syphilis, or HIV test.

cAmong persons not known to have HIV infection.

dEvalution included sexual history, anogenital examination, ≥ 1 additional STI test.

Among all patients tested for mpox, 12.3% (19/154) had a positive STI result (Table 3). Among patients with positive mpox tests, the prevalence of STI coinfection was 20.4% (11/54) (Table 4). The most common coinfection among patients with mpox was syphilis: new diagnoses occurred in almost 1 in 5 patients (7/40). The range of RPR titers in those with a new diagnosis of syphilis was 1:4–1:256 with a mode of 1:4. There were no new HIV cases identified.

Table 3.

STI Infection Among all Patients Undergoing mpox Testing by Site

| Diagnosis Site | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | ID | PCP | ED | P value | |

| Any positive STI (n = 154)a | .080 | ||||

| Yes | 19 (12.3%) | 8 (19.5%) | 0 (0.0%) | 11 (11.8%) | |

| No | 135 (87.7%) | 33 (80.5%) | 20 (100.0%) | 82 (88.2%) | |

| Positive HIV (n = 77)b | - | ||||

| Yes | 0 (0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | |

| No | 77 (100%) | 4 (100.0%) | 15 (100.0%) | 58 (100.0%) | |

| Positive gonorrhea (n = 105) | .413 | ||||

| Yes | 5 (4.8%) | 3 (8.1%) | 0 (0.0%) | 2 (3.6%) | |

| No | 100 (95.2%) | 34 (91.9%) | 12 (100.0%) | 54 (96.4%) | |

| Positive chlamydia (n = 105) | .780 | ||||

| Yes | 4 (3.8%) | 2 (5.6%) | 0 (0.0%) | 2 (3.5%) | |

| No | 101 (96.2%) | 34 (94.4%) | 12 (100.0%) | 55 (96.5%) | |

| Positive extragenital gonorrhea (n = 52) | .695 | ||||

| Yes | 3 (5.8%) | 3 (8.8%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0%) | |

| No | 49 (94.2%) | 31 (91.2%) | 6 (100%) | 12 (100%) | |

| Positive extragenital chlamydia (n = 52) | 1.000 | ||||

| Yes | 2 (3.8%) | 2 (6.1%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | |

| No | 50 (96.2%) | 31 (93.9%) | 6 (100.0%) | 13 (100.0%) | |

| New syphilis diagnosis (n = 110) | .504 | ||||

| Yes | 14 (12.7%) | 4 (15.4%) | 0 (0.0%) | 10 (13.9%) | |

| No | 96 (87.3%) | 22 (84.6%) | 12 (100.0%) | 62 (86.1%) | |

Abbreviations: ED, emergency department; ID, infectious diseases; PCP, primary care provider; STI, sexually transmitted infection.

aAny positive STI (gonorrhea, chlamydia, syphilis or HIV) excluding mpox.

bExcluding patients with known HIV positive status.

Table 4.

STI Coinfections Among Patients With Positive mpox Test by Site

| Diagnosis Site | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | ID | PCP | ED | P value | |

| Any other STI coinfection (n = 54) | .691 | ||||

| Yes | 11 (20.4%) | 4 (20.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 7 (24.1%) | |

| No | 43 (79.6%) | 16 (80.0%) | 5 (100.0%) | 22 (75.9%) | |

| HIV coinfection (n = 17) | - | ||||

| Yes | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | |

| No | 17 (100%) | 1 (100.0%) | 3 (100.0%) | 13 (100.0%) | |

| Gonorrhea coinfection (n = 47) | .688 | ||||

| Yes | 3 (6.4%) | 2 (10.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (4.3%) | |

| No | 44 (93.6%) | 18 (90.0%) | 4 (100.0%) | 22 (95.7%) | |

| Chlamydia coinfection (n = 48) | 1.000 | ||||

| Yes | 2 (4.2%) | 1 (5.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (4.2%) | |

| No | 46 (95.8%) | 19 (95.0%) | 4 (100.0%) | 23 (95.8%) | |

| Syphilis coinfection (n = 40) | .584 | ||||

| Yes | 7 (17.5%) | 1 (7.7%) | 0 (0.0%) | 6 (24.0%) | |

| No | 33 (82.5%) | 12 (92.3%) | 2 (100.0%) | 19 (76.0%) | |

Abbreviations: ED, emergency department; ID, infectious diseases; PCP, primary care provider; STI, sexually transmitted infection.

A composite marker of high quality of sexual health care including anogenital examination, sexual history, and STI testing was analyzed by venue of testing and patient characteristics. Age was not associated with the combined outcome for adults aged 18–30 years old (odds ratio [OR], 0.98; 95% confidence interval [CI], .91–1.06). For adults >30 years, each additional year of age was associated with a decreased odds of the combined outcome (OR, 0.97 [95% CI, .95–.99]). Cisgender male MSM, transgender males, and transgender females as a group were associated with greater odds of completing the composite outcome (aOR, 4.03 [95% CI, 1.94–8.37]) compared to cisgender females adjusted for venue and age. This association was not present among non-MSM cisgender males (aOR, 1.22 [95% CI, .57–2.65]). Patients evaluated in an ID setting had a higher OR of completion of all three measures (OR, 6.11 [95% CI, 2.58–14.50]) compared to PCP setting; however, this association was not significant in ED setting (OR, 1.36 [95% CI, .66–2.80]) compared to PCP setting. These findings were attenuated after adjusting for age and MSM status: ID versus PCP (aOR, 3.60 [95% CI, 1.39–9.30]) and ED versus PCP setting (aOR, 1.36 [95% CI, .62–2.99]) (Table 5).

Table 5.

Odds Ratio of Completion of Composite Outcome by Demographics and Clinical Site

| Odds Ratio | 95% CI | Adjusted Odds Ratio | 95% CI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PCPa,b | REF | REF | REF | REF |

| EDb,c | 1.36 | [.66–2.80] | 1.36 | [.62–2.99] |

| IDb,d | 6.11 | [2.58–14.50] | 3.60 | [1.39–9.30] |

| Age ≤30 yb | 0.98 | [.91–1.06] | 0.99 | [.90–1.09] |

| Age >30 yb | 0.97 | [.95–.99] | 0.98 | [.95–1.00] |

| Black race | 1.28 | [.78–2.11] | ||

| PWH | 1.00 | [.98–1.02] | - | - |

| Cisgender femaleb | REF | REF | REF | REF |

| Cisgender male non-MSMb,e | 1.41 | [.67–2.98] | 1.22 | [.57–2.65] |

| Cisgender male MSM, transgender male, transgender female and otherb,e | 6.54 | [3.36–12.74] | 4.03 | [1.94–8.37] |

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; ED, emergency department; ID, infectious diseases; MSM, men who have sex with men; PCP, primary care provider; PWH, persons with HIV;STI, sexually transmitted infection .

aPCP includes primary care, obstetrics and gynecology, dermatology, and pediatrics.

bIncluded in multivariable analysis.

cED includes emergency department and urgent care.

dID includes infectious disease clinic.

eMSM status defined as cisgender males who reported being gay or bisexual.

DISCUSSION

We report several novel findings among patients evaluated for mpox during 2022. First, we found provider patterns for mpox evaluation were different by venue and there were low rates of adherence to CDC guidelines. These differences persisted after adjusting for differential patient characteristics across venues. Second, there was a high prevalence of STI coinfections among patients tested for mpox, and syphilis was the most common coinfection among patients tested for mpox. Finally, we found that providers were more likely to perform guideline adherent care with MSM males and transgender persons.

Prior work has demonstrated gaps in STI testing, counseling, and sexual history taken in emergency medicine and primary care settings, and higher rates of STI testing in ID clinics [14, 19–21]. In our study, sexual history was most reliably recorded, followed by anogenital examination and STI testing. Adherence to CDC guidelines was highest in ID clinics followed by EDs and PCP clinics. There are a variety of barriers to provision of comprehensive sexual health care across clinical venues including competing priorities, time constraints, access to test collection kits, knowledge, and inability to follow up on results [22]. These factors may have contributed to our findings; however, given the novelty of the mpox outbreak, there were additional unique barriers such as infection control processes and lack of familiarity with mpox disease and testing procedures. Further work to examine barriers to comprehensive evaluation in ambulatory and urgent care/ED settings is needed to identify factors such as education and training deficits, access to testing materials, and other barriers contributing to gaps in care. The advent of home-based sampling for mpox, STI, and HIV testing has the potential to increase individual autonomy, increase choice, and decrease the need for in-person assessment [23–25].

STI coinfections were common among patients with confirmed mpox (20.4%). This rate is higher than a study of 225 persons tested for mpox within the Duke University Health System, who reported coinfection in 15% [15%] and 17% reported among a cohort of 181 persons diagnosed with mpox in Spain [4]. A STI coinfection rate of 31.5% was reported in a study of 187 patients in London; however, the most common STI was gonorrhea and syphilis was uncommon [26]. In our health system, only half of patients with suspected mpox were tested for other STIs. These findings underscore a missed opportunity for expanding the differential diagnosis of ulcer disease, and concomitant STI testing—a gap previously highlighted among sexual and gender minority groups [27, 28].

Syphilis was the most common bacterial STI coinfection in patients with mpox [4, 5, 15]. Syphilis was the most common bacterial STI despite higher rates of gonorrhea and chlamydia screening in the ID and PCP settings, perhaps reflecting ease of obtaining blood samples compared to swabs. This is consistent with the increased rates of syphilis reported in the United States [29, 30]. In contrast, a study of patients with mpox in London reported higher coinfection with gonorrhea, chlamydia, and herpes simplex, which may reflect regional patterns [26]. We found a high absolute number of new syphilis diagnoses in the ED, which may reflect the role of the ED in serving persons with vulnerabilities for STIs who otherwise cannot access care [29, 31]. Prior work has advocated for universal screening of at-risk persons in the ED for syphilis [31], and our results could support targeted syphilis screening in this setting for those with a compatible risk profile.

We found MSM and transgender persons were more likely to receive guideline concurrent care for mpox. There are few data analyzing STI testing stratified by MSM status among studies of patients evaluated for mpox; however, STI coinfection is well-described among MSM and PWH, which may inform provider behavior [32, 33]. We found a trend that advanced patient age was negatively associated with completion of the composite outcome of guideline concordant care. This suggests that provider behavior in assessment of mpox reflects trends in the general population of decreased attention to sexual health assessment with advancing age [34, 35] and echoes prior work highlighting missed opportunities in the recognition of HIV infection in the elderly [36, 37].

This study has several limitations. The study catchment includes 1 large urban health center in the United States with a tertiary referral network and may not be generalizable to other clinical settings. There was likely underestimation of the total number of cases, as some mild or self-limited cases may not have presented for medical attention or that patients presented with symptoms but mpox was not considered in the provider's differential diagnosis. It is also possible that providers did take a sexual history and/or complete an anogenital examination and simply did not document it in the record. Although testing was collected comprehensively and downloaded from our laboratory system, any patients who underwent mpox or STI testing evaluation at sites outside of JHHS would not be captured. And, finally, it is possible that individuals tested for mpox in the ED and PCP had a lower risk for sexually associated infections, which contributed to lower rates of comprehensive sexual health evaluations. This is supported by the lower rates of positive mpox test results in these settings.

Our results findings highlight an unmet need caring for an at-risk population across diverse health care venues. Quality of care indicators for mpox evaluation were highest in clinics where sexual health assessment was routine and less common in ED and primary care settings. Further work is needed to facilitate sexual health evaluations in all settings, with a particular focus on ED and PCP venues, to ensure appropriate diagnosis, treatment, and prevention of sexually associated infections. Strategies that address barriers to comprehensive sexual health care should be explored, such as educating providers on standards of care for evaluation of suspected mpox and other STIs, audio-computer–assisted patient report of sexual history, and patient self-collection of STI testing specimens. Although home-based sampling for mpox may increase testing uptake, mpox swab collection outside of a clinical setting poses additional challenges including lack of access to rapid start HIV preexposure prophylaxis or doxycycline postexposure prophylaxis, and false-negative results resulting from inadequate sample collection or improper technique.

Future studies should assess ways to increase STI testing among at-risk populations and using STI testing as an opportunity to discuss HIV/STI prevention measures including pre- and postexposure prophylaxis and provision of immunization against vaccine-preventable STIs including mpox.

Note

Acknowledgments. Substantial contributions to the conception or design of the work: W.M.G., J.L.J., K.A.G., and B.H. Substantial contributions to the acquisition or analysis of data for the work: W.M.G., J.L.J., D.S.R., G.M.D., N.K., M.M.H., E.A.G., J.C.K., E.Y.K., N.W., BH., and K.A.G. Substantial contributions to the interpretation of data for the work: W.M.G., J.L.J., K.A.G., N.W., and B.H. Drafting the work or revising it critically for important intellectual content: W.M.G., J.L.J., and K.A.G. Senior author: K.A.G. Final approval of the version to be published: all authors. Agreement to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved: W.M.G.

The authors gratefully acknowledge the study participants who generously gave of their time and biological specimens and the passionate study personnel who facilitated these studies.

Financial support. This study was funded principally by the Center for AIDS Research, Johns Hopkins University (P30AI094189), the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (NCATS) KL2TR003099, the Institute for Clinical and Translational Research (1UL1TR001079–01) as well as the Clinical Characterization Protocol for Severe Emerging Infection (CCPSEI) grant funded by the Johns Hopkins University. E.Y.K. is supported by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (U01CK000589). The study sponsors did not contribute to the study design, the collection, analysis, and interpretation of data, or the decision to submit this manuscript for publication.

Disclaimer. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the funders.

Contributor Information

William M Garneau, Department of Medicine/Division of Hospital Medicine, Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, Baltimore, Maryland, USA.

Joyce L Jones, Departent of Medicine/Division of Infectious Diseases, Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, Baltimore, Maryland, USA.

Gabriella M Dashler, Department of Emergency Medicine, Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, Baltimore, Maryland, USA.

Nathan Kwon, Department of Emergency Medicine, Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, Baltimore, Maryland, USA.

Matthew M Hamill, Departent of Medicine/Division of Infectious Diseases, Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, Baltimore, Maryland, USA.

Elizabeth A Gilliams, Departent of Medicine/Division of Infectious Diseases, Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, Baltimore, Maryland, USA.

David S Rudolph, Department of Emergency Medicine, Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, Baltimore, Maryland, USA.

Jeanne C Keruly, Departent of Medicine/Division of Infectious Diseases, Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, Baltimore, Maryland, USA.

Eili Y Klein, Department of Emergency Medicine, Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, Baltimore, Maryland, USA.

Nae-Yuh Wang, Department of Medicine/Division of General Internal Medicine, Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, Baltimore, Maryland, USA.

Bhakti Hansoti, Department of Emergency Medicine, Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, Baltimore, Maryland, USA.

Kelly A Gebo, Departent of Medicine/Division of Infectious Diseases, Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, Baltimore, Maryland, USA.

References

- 1. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention . 2022 Outbreak Cases and Data. March 5, 2024. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/poxvirus/mpox/response/2022/index.html. Accessed 9 May 2024

- 2. World Health Organization . Disease Outbreak News; multi-country monkeypox outbreak in non-endemic countries: Update. June 17, 2022. Available at: https://www.who.int/emergencies/disease-outbreak-news/item/2022-DON393

- 3. Lum FM, Torres-Ruesta A, Tay MZ, et al. Monkeypox: disease epidemiology, host immunity and clinical interventions. Nat Rev Immunol 2022; 22:597–613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Tarín-Vicente EJ, Alemany A, Agud-Dios M, et al. Clinical presentation and virological assessment of confirmed human monkeypox virus cases in Spain: a prospective observational cohort study. Lancet 2022; 400:661–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Thornhill JP, Barkati S, Walmsley S, et al. Monkeypox virus infection in humans across 16 countries—April–June 2022. N Engl J Med 2022; 387:679–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Thornhill JP, Palich R, Ghosn J, et al. Human monkeypox virus infection in women and non-binary individuals during the 2022 outbreaks: a global case series. Lancet Lond Engl 2022; 400:1953–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Philpott D, Hughes CM, Alroy KA, et al. Epidemiologic and clinical characteristics of monkeypox cases—United States, May 17–July 22, 2022. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2022; 71:1018–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention . Clinical Quick Reference for Mpox. January 10, 2024. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/poxvirus/mpox/clinicians/clinical-guidance-quick-reference.html. Accessed 30 January 2024

- 9. Infectious Diseases Society of America/Centers for Disease Control . IDSA/CDC Clinician Call—Monkeypox: Updates on Testing, Vaccination & Treatment Slide Deck. Available at: https://www.idsociety.org/globalassets/idsa/multimedia/clinician-call-slides–qa/7-23-22-clinician-call.pdf. Accessed 20 May 2024

- 10. Braybrook D, Bristowe K, Timmins L, et al. Communication about sexual orientation and gender between clinicians, LGBT+ people facing serious illness and their significant others: a qualitative interview study of experiences, preferences and recommendations. BMJ Qual Saf 2023; 32:109–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. An official position statement of the Association of Women's Health, Obstetric and Neonatal Nurses . The use of chaperones during sensitive examinations and treatments. J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs 2022; 51:e1–2. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Stryker MA, Patel RD, Khaled DT, et al. Factors affecting the completion of genitourinary physical examinations prior to urologic consultation. Ochsner J 2018; 18:72–5. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Dichter ME, Ogden SN. The challenges presented around collection of patient sexual orientation and gender identity information for reduction of health disparities. Med Care 2019; 57:945–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Kushner M, Solorio MR. The STI and HIV testing practices of primary care providers. J Natl Med Assoc 2007; 99:258–63. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Mourad A, Alavian N, Woodhouse EW, et al. Concurrent sexually transmitted infection testing among patients tested for mpox at a tertiary healthcare system. Open Forum Infect Dis 2023; 10:ofad381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention . Treatment Information for Healthcare Professionals. July 10, 2023. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/poxvirus/mpox/clinicians/treatment.html. Accessed 21 July 2023

- 17. Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, Payne J, Gonzalez N, Conde JG. Research electronic data capture (REDCap)—a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform 2009; 42:377–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Harris PA, Taylor R, Minor BL, et al. The REDCap consortium: building an international community of software platform partners. J Biomed Inform 2019; 95:103208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Evans EM, Goyke TE, Cohrac SA, et al. Compliance with centers for disease control guidelines for ED patients with sexually transmitted diseases. Am J Emerg Med 2016; 34:1727–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Palaiodimos L, Herman HS, Wood E, et al. Practices and barriers in sexual history taking: a cross-sectional study in a public adult primary care clinic. J Sex Med 2020; 17:1509–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Sequeira S, Morgan JR, Fagan M, Hsu KK, Drainoni ML. Evaluating quality of care for sexually transmitted infections in different clinical settings. Sex Transm Dis 2015; 42:717–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Zucker J, Carnevale C, Theodore DA, et al. Attitudes and perceived barriers to sexually transmitted infection screening among graduate medical trainees. Sex Transm Dis 2021; 48:e149–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Food and Drug Administration . Emergency use authorization (EUA) summary for the LABCORP monkeypox PCR test home collection kit. March 22, 2024. Available at: https://www.fda.gov/media/177286/download. Accessed 28 April 2024

- 24. Melendez JH, Hamill MM, Armington GS, Gaydos CA, Manabe YC. Home-based testing for sexually transmitted infections: leveraging online resources during the COVID-19 pandemic. Sex Transm Dis 2021; 48:e8–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Norelli J, Zlotorzynska M, Sanchez T, Sullivan PS. Scaling up CareKit: lessons learned from expansion of a centralized home HIV and sexually transmitted infection testing program. Sex Transm Dis 2021; 48(8S):S66–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Patel A, Bilinska J, Tam JCH, et al. Clinical features and novel presentations of human monkeypox in a central London centre during the 2022 outbreak: descriptive case series. BMJ 2022; 378:e072410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Zucker J, Patterson B, Ellman T, et al. Missed opportunities for engagement in the prevention continuum in a predominantly Black and Latino community in New York city. AIDS Patient Care STDs 2018; 32:432–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Kutner BA, Zucker J, López-Rios J, Lentz C, Dolezal C, Balán IC. Infrequent STI testing in New York city among high risk sexual and gender minority individuals interested in self- and partner-testing. AIDS Behav 2022; 26:1153–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Berzkalns A, Ramchandani MS, Cannon CA, Kerani RP, Dombrowski JC, Golden MR. The syphilis epidemic among heterosexuals is accelerating: evidence from King County, Washington. Open Forum Infect Dis 2023; 10:ofad481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention . National Overview of STIs, 2022. January 30, 2024. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/std/statistics/2022/overview.htm#Syphilis. Accessed 15 April 2024

- 31. Stanford KA, Hazra A, Friedman E, et al. Opt-out, routine emergency department syphilis screening as a novel intervention in at-risk populations. Sex Transm Dis 2021; 48:347–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Chung SL, Wong NS, Ho KM, Lee SS. Coinfection and repeat bacterial sexually transmitted infections (STI)—retrospective study on male attendees of public STI clinics in an Asia Pacific city. Epidemiol Infect 2023; 151:e101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Braun DL, Marzel A, Steffens D, et al. High rates of subsequent asymptomatic sexually transmitted infections and risky sexual behavior in patients initially presenting with primary human immunodeficiency virus-1 infection. Clin Infect Dis 2018; 66:735–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Ports KA, Barnack-Tavlaris JL, Syme ML, Perera RA, Lafata JE. Sexual health discussions with older adult patients during periodic health exams. J Sex Med 2014; 11:901–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Foley S. Older adults and sexual health: a review of current literature. Curr Sex Health Rep 2015; 7:70–9. [Google Scholar]

- 36. El-Sadr W, Gettler J. Unrecognized human immunodeficiency virus infection in the elderly. Arch Intern Med 1995; 155:184–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Levy I, Maor Y, Mahroum N, et al. Missed opportunities for earlier diagnosis of HIV in patients who presented with advanced HIV disease: a retrospective cohort study. BMJ Open 2016; 6:e012721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]