Abstract

Hepatitis B is one of the most common infectious diseases globally. It has been estimated that there are 350 million chronic hepatitis B virus (HBV) carriers worldwide. The prevalence of chronic HBV infection varies geographically, from high (>8%), intermediate (2-7%) to low (<2%) prevalence. HBeAg-negative chronic hepatitis B (e-CHB) and occult HBV infection are two special clinical entities, and the prevalence and clinical implications remain to be explored. The predominant routes of transmission vary according to the endemicity of the HBV infection. In areas with high HBV endemicity, perinatal transmission is the main route of transmission, whereas in areas with low HBV endemicity, sexual contact amongst high-risk adults is the predominant route. HBV has been classified into 7 genotypes, i.e. A to G, based on the divergence of entire genome sequence and HBV genotypes have distinct geographical distributions. Three main strategies have been approved to be effective in preventing HBV infection. They are behavior modification, passive immunoprophylaxis, and active immunization. The implement of mass HBV immunization program is recommended by the WHO since 1991, and has dramatically decreased the prevalence of HBV infection and HCC in many countries.

Keywords: Hepatitis B infection, Epidemiology, Prevention, HBV immunization

1. Introduction

Hepatitis B virus (HBV) is a serious public health problem worldwide and major cause of chronic hepatitis, cirrhosis, and hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC). It was estimated that approximately 2 billion people have serological evidence of past or present HBV infection. More than 350 million are chronic carriers of HBV 1. Approximately 75% of chronic carriers live in Asia and the Western Pacific 2. It was reported that 15-40% of HBV infected patients would develop cirrhosis, liver failure, or HCC 3, and 500, 000 to 1.2 million people die of HBV infection annually 4,5. Because of the high HBV-related morbidity and mortality, the global disease burden of HB is substantial.

2. Epidemiology

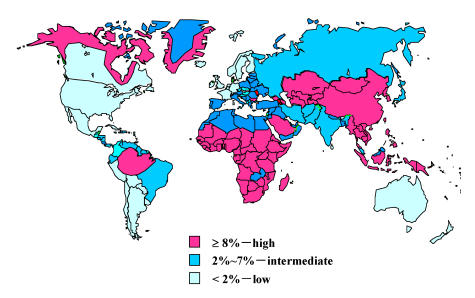

The prevalence of chronic HBV infection varies greatly in different part of the world (Figure 1). The prevalence of chronic HBV infection worldwide could be categorized as high, intermediate and low endimicity. The age at the time of infection is associated with the endemicity of HBV infection (Table 1).

Figure 1.

Geographic distribution of chronic hepatitis B infection, shown as HBsAg prevalence. Source of Figure: available on request from D. Lavanchy, World Health Organization, Communicable Diseases Surveillance and Response (CSR).

Table 1.

Characteristics of endemic patterns of hepatitis B virus infection. Source: adapted from Ref.7.

| Characteristic | Endemicity of infection | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Low (%) | Intermediate (%) | High (%) | |

| Chronic infection prevalence | 0.5-2 | 2-7 | ≥8 |

| Past infection prevalence | 5-7 | 10-60 | 70-95 |

| Perinatal infection | Rare | Uncommon | Common |

| (<10) | (10-60) | (>20) | |

| Early childhood infection | Rare | Common | Very ommon |

| (<10) | (10-60) | (>60) | |

| Adolescent/adult infection | Very common | Common | Uncommon |

| (70-90) | (20-50) | (10-20) | |

High Endemicity

The prevalence of HBV infection varies markedly throughout regions of the world 6. Hepatitis B is highly endemic in developing regions with large population such as South East Asia, China, sub-Saharan Africa and the Amazon Basin, where at least 8% of the population are HBV chronic carrier. In these areas, 70–95% of the population shows past or present serological evidence of HBV infection. Most infections occur during infancy or childhood. Since most infections in children are asymptomatic, there is little evidence of acute disease related to HBV, but the rates of chronic liver disease and liver cancer in adults are high 7.

Intermediate Endemicity

Hepatitis B is moderately endemic in part of Eastern and Southern Europe, the Middle East, Japan, and part of South America. Between 10–60% of the population have evidence of infection, and 2-7% are chronic carriers. Acute disease related to HBV is common in these areas because many infections occur in adolescents and adults; however, the high rates of chronic infection are maintained mostly by infections occurring in infants and children 8. In these areas, mixed patterns of transmission exist, including infant, early childhood and adult transmission.

Low Endemicity

The endemicity of HBV is low in most developed areas, such as North America, Northern and Western Europe and Australia. In these regions, HBV infects 5–7% of the population, and only 0.5–2% of the population are chronic carriers 9. In these areas, most HBV infections occur in adolescents and young adults in relatively well-defined high-risk groups, including injection drug user, homosexual males, health care workers, patients who require regular blood transfusion or hemodialysis.

3. HBV Transmission

HBV is spread through contact with infected body fluids and the only natural host is human. Blood is the most important vehicle for transmission, but other body fluids have also been implicated, including semen and saliva 10,11. Currently, three modes of HBV transmission have been recognized: perinatal, sexual and parenteral/percutaneous transmission. There is no reliable evidence that airborne infections occur and feces are not a source of infection. HBV is not transmitted by contaminated food or water, insects or other vectors.

Perinatal Transmission

Transmission of HBV from carrier mothers to their babies can occur during the perinatal period, and appears to be the most important factor in determining the prevalence of the infection in high endemicity areas, particularly in China and Southeast Asia. Before HBV vaccine was integrated into the routine immunization program, the proportion of babies that become HBV carriers is about 10-30% for mothers who are HBsAg-positive but HBeAg-negative. However, the incidence of perinatal infection is even greater, around 70-90%, when the mother is both HBsAg-positive and HBeAg-positive 12,13. There are three possible routes of transmission of HBV from infected mothers to infants: transplacental transmission of HBV in utero; natal transmission during delivery; or postnatal transmission during care or through breast milk. Since transplacental transmission occurs antenatally, hepatitis B vaccine and HBIG cannot block this route. Epidemiological studies on HBV intrauterine infection in China showed that intrauterine infection occurs in 3.7-9.9% pregnancy women with positive HBsAg and in 9.8-17.39% with positive HBsAg/HBeAg 14-21 and it was suggested that a mother with positive HBeAg (OR = 17. 07) and a history of threatened premature labor (OR = 5. 44) are the main risk factors for intrauterine infection. The studies on transplacental transmission of HBV suggested two possible mechanisms (1) hemagenous route: a certain of factors, such as threaten abortion, can make the placental microvascular broken, thus the high-titer HBV maternal blood leak into fetus' circulation 20,22; (2) cellular transfer: the placental tissue is infected by high-titer of HBV in maternal blood from mother's side to fetus' step by step, and finally, HBV reach fetus' circulation through the villous capillary endothelial cells 14-18.

For neonates and children younger than 1 year who acquire HBV infection perinatally, the risk of the infection becoming chronic is 90% 23, presumably because neonates have an immature immune system. One of the possible reasons for the high rate of chronicity is that transplacental passage of HBeAg may induce immunological tolerance to HBV in fetus.

Sexual Transmission

Sexual transmission of hepatitis B is a major source of infection in all areas of the world, especially in the low endemic areas, such as North America. Hepatitis B is considered to be a sexually transmitted disease (STD). For a long time, homosexual men have been considered to be at the highest risk of infection due to sexual contact (70% of homosexual men were infected after 5 years of sexual activity) 24. However, heterosexual transmission accounts for an increasing proportion of HBV infections. In heterosexuals, factors associated with increased risk of HBV infection include duration of sexual activity, number of sexual partners, history of sexual transmitted disease, and positive serology for syphilis. Sexual partners of injection drug users, prostitutes, and clients of prostitutes are at particularly high risk for infection 25.

Parenteral/percutaneous Transmission

The parenteral transmission includes injection drug use, transfusions and dialysis, acupuncture, working in a health-care setting, tattooing and household contact. In the United States and Western Europe, injection drug use remains a very important mode of HBV transmission (23% of all patients) 6. Risk of acquiring infection increases with duration of injection drug use. Although the risk for transfusion-associate HBV infection has been greatly reduced since the screening of blood for HBV markers and the exclusion of donors who engage in high-risk activities, the transmission is still possible when the blood donors are asymptomatic carrier with HBsAg negative 26. Obvious sources of infection include HBV-contaminated blood and blood products, with contaminated surgical instruments and utensils being other possible hazards. Parenteral/percutaneous transmission can occur during surgery, after needle-stick injuries, intravenous drug use, and following procedures such as ear piercing, tattooing, acupuncture, circumcision and scarification. The nosocomial spread of HBV infection in the hospital, particularly in dialysis units, as well as in dental units, has been well described 6, even when infection control practices are followed. As with other modes of transmission, high vial titers have been related to an increased risk of transmission. People at high-risk of infection include those requiring frequent transfusions or hemodialysis, physicians, dentists, nurses and other healthcare workers, laboratory technicians, intravenous drug users, police, firemen, laundry workers and others who are likely to come into contact with potentially infected blood and blood products.

The risk of chronicity is low (less than 5%) for transmission through sexual contact, intravenous drug use, acupuncture, and transfusion 23. Individuals at risk for these transmission modes usually acquire HBV infection during adolescence or adulthood without immune tolerance. Instead, the disease progresses directly to the immune clearance phase and is of short duration, which probably accounts for high spontaneous recovery.

4. HBV Genotype and Its Clinical Significance

Based on an intergroup divergence of 8% or more of the complete genomes, HBV can be classified in to 7 genotypes, i.e. A-G 27-30. Genotype H was recently identified in central America 31. It is well known that HBV genotypes have distinct geographical distributions. The geographical distributions of HBV genotypes are summarized in Table 2. The prevalent HBV strains in China are genotype B and C 32, but the two genotypes distribute unevenly in China. We studied 1096 Chinese chronic HBV carriers from 9 provinces in Mainland China. Four major genotypes A, B, C and D were found and their prevalence were 1.2%, 41%, 52.5% and 4.3%, respectively. In northern China, genotype C is predominant (85.1%), while in southern China, genotype B is predominant (55.0%) [Hou, et al., unpublished data]. Genotypes A and D are also found in other areas of China. However, the genotypes E-H have not been reported in China. Recently, genotype C/D hybrid was identified in Tibet 33 and genotype B was found recombinated with preC/C region of genotype C in China 34. Accumulated data suggest the importance of genotype, subgroup and recombination that may influence the biological characteristics of virus and clinical outcome of HBV infection. Several studies reported a correlation of HBV genotypes with HBeAg clearance, liver damage, and the response to IFN treatment. It was reported that HBeAg carrier status tends to be longer and the prevalence of HBeAg appears higher in patients with genotype C than with genotype B 35,36. HBV carriers with genotype B have lower histologic activity scores 37, and genotype C is more prevalence in patients with cirrhosis 38,39. Furthermore, a retrospective study showed that HBV genotype B is associated with a higher rate of IFN-induced HBeAg clearance compared with genotype C 40. However, whether patients with genotype B differ from those with genotype C in development of hepatocellular carcinoma remains controversial. The response of different HBV genotypes to interferon-alfa treatment is of increasing interest because the benefit of interferon-alfa or its pegylated form in combination with other antiviral agents is being explored in the treatment of chronic hepatitis B. In a homogeneous group of prospectively followed patients from Europe, a recent study demonstrates that genotype A responds better than other HBV genotypes to standard interferon therapy and represents an independent predictor of a therapeutic success, with a greater impact than other pre-treatment characteristics, such as HBV DNA or ALT levels 41.

Table 2.

Geographic Distribution of HBV Genotypes

| Genotypes | Distributions |

|---|---|

| A (Aa, Ae) | White Caucasians in Europe, Black Americans in US (Ae), Black Africans, South Africa (Aa), Asia (Aa), India |

| B (Ba, Bj) | Southern China (Ba), Taiwan (Ba), Vietnam (Ba), Asians in the USA, Japan (Bj) |

| C | China (Mainland and Taiwan), Japan, Thailand, Asians in the USA |

| D | White Caucasians (Southern Europe), Arabs (North Africa and the Middle East), India |

| E | West Africa |

| F | Central and South America |

| G | United States, France |

| H | Central America |

5. Occult Hepatitis B

Occult hepatitis B is defined by the presence of HBV DNA in serum or liver in the absence of HBsAg 42,43. Serum HBV level is usually less than 104 copies/ml. Although occult HBV infection has been identified in patients with chronic liver disease two decades ago 44, its precise prevalence remains to be defined. Occult HBV infection has been found in patients with HCC, past HBV infection, or chronic hepatitis C, and individuals without HBV serological markers. The frequency of the diagnosis depends on the relative sensitivity of HBV DNA assays and the prevalence of HBV infection in the population. Collectively, around 30% to 35% of HBsAg-negative subjects with chronic hepatitis with or without HCC have positive serum HBV DNA (range from 5% to 55%). The prevalence of HBV DNA is higher in anti-HBc-positive, but anti-HBs-negative patients, ranging from 7% to 60% in populations highly exposed to HBV 45. HBV DNA is much less frequently identified in HBsAg-negative patients with acute, and particularly fulminant hepatitis at around 10% and 7% in serum and liver samples 45. Viral DNA persistence is not, however, restricted to patients with liver disease and may be observed in subjects with normal liver parameters, including blood and/or organ donors. Overall, occult HBV infection is seen in 7%-13% of anti-HBc-positive and/or anti-HBs-positive subjects, and in 0% to 17% of blood donors.

The clinical significance of occult HBV infection remains unclear. Occult HBV infection represents a potential transmission source of HBV via blood transfusion or organ transplantation. In addition, occult HBV infection has been associated with cryptogenic chronic hepatitis and hepatocellular carcinoma. Furthermore, some studies suggested that occult hepatitis B might affect responsiveness of chronic hepatitis C to interferon therapy and disease progress.

6. HBeAg-negative CHB

HBeAg-negative chronic hepatitis B (e-CHB), characterized by HBV DNA levels detectable by nonamplified assays and continued necroinflammation in the liver, has been reported worldwide, but is more common in Mediterranean countries and Asia. The prevalence of e-CHB is 33% in the Mediterranean, 15% in Asia Pacific, and 14% in the United States and Northern Europe 46. Although the presence of e-CHB is more common in the Mediterranean, its clinical impact appears greatest in China where a prevalence of 15% among HBsAg carriers equals to approximately 15 million cases of e-CHB. It is expected that the prevalence of e-CHB tends to increase. This is supported by data from a few studies in South-east Asia. Of the 743 successive patients with CHB in our Liver Unit, 267 (35.9%) were HBeAg-negative 47. A cross-sectional study performed in Hong Kong showed that e-CHB might be present in up to 17% of HBeAg-negative patients 48. Another study conducted in Korea found that among the 413 consecutive HBeAg-negative patients, 17.7% of HBeAg-negative patients had e-CHB 49.

Most patients with e-CHB harbor HBV variants in the precore or core promoter region. The most common precore mutation, G1896A, creates a premature stop codon in the precore region thus abolishing production of HBeAg 50. The variant is commonly found in association with HBV genotype D, which is prevalence in the Mediterranean area and is rarely detected in the United States and North-West Europe 51,52. The most common core promoter mutations, A1762T+G1764A, decrease transcription of precore messenger RNA and production of HBeAg 53. There are also clinical differences between HBeAg-positive and HBeAg-negative chronic hepatitis B 54. Patients with e-CHB tends to have lower serum HBV DNA levels and are more likely to have a fluctuating course characterized by persistently elevated or fluctuating ALT levels 54,55. Although there has been a great deal of interest in these HBV variants, the clinical significance of these mutant viruses, particularly those described in association with severe liver disease, remains controversial.

7. HBV and Hepatocellular Carcinoma

Epidemiologic studies have demonstrated that there is a consistent and specific causal association between HBV infection and HCC 56-58. In patients with persistent HBV infection, the risk of HCC was 100 times higher than in non-infected individuals 56. The global distribution of hepatocellular carcinoma correlates with the geographic prevalence of chronic carriers of HBV, who number 400 million worldwide. The highest rates are in Southeast Asia and sub-Saharan Africa, with the HCC incidence >50/100, 000 population 59.

Virological factors in the pathogenesis of hepatocellular carcinoma have recently been defined. Both retrospective and prospective studies strongly supported the relation between positive HBeAg and the risk of HCC 60-62. A prospective study in Taiwan 62 showed that relative risk of HCC among men who were positive for both HBsAg and HBeAg (RR=60.2) were much higher than that among men who were positive for HBsAg alone (RR=9.6). HBV DNA was identified as the most important predictor of the development of hepatocellular carcinoma in HBsAg-positive patients with different clinical conditions 63-65. Therefore, efforts at eradicating or reducing the viral load may reduce the risk for HCC. Additionally, HBV genotype might play a role in the development of HCC. The data from Taiwan showed that genotype C is associated with more severe liver disease including cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), whereas genotype B is associated with the development of HCC in young noncirrhotic patients.

8. Prevention of HBV Infection

Three main strategies are available for the prevention of HBV infection: (1) behavior modification to prevent disease transmission, (2) passive immunoprophylaxis, and (3) active immunization.

Behavior Modification

Changes in sexual practice and improved screening measures of blood products have reduced the risk of transfusion-associated hepatitis. Behavior modification is thought be more beneficial in developed countries than in developing countries, where neonates and children in early childhood are at the greatest risk of acquiring infection. In these group, immunoprophylaxis, both passive and active, will be more effective.

Passive Immunoprophylaxis

Hepatitis B Immune Globulin (HBIG) is a sterile solution of ready-made antibodies against hepatitis B. HBIG is prepared from human blood from selected donors who already have a high level of antibodies to hepatitis B and used in passive immunoprophylaxis. Passive immunoprophylaxis is used in four situations (1) newborns of mothers infected with hepatitis B; (2) after needlestick exposure, (3) after sexual exposure, and (4) after liver transplantation. Immunoprophylaxis is recommended for all infants born to HBsAg positive mothers. Current dosing recommendations are 0.13ml/kg HBIG immediately after delivery or within 12 hours after birth in combination with recombinant vaccine. The combination results in a higher-than-90% level of protection against perinatal acquisition of HBV 66. Between 3.7% to 9.9% of infants still acquire HBV infection perinatally from HBV-infection mothers, despite immunoprophylaxis 14-21. Failure of passive and active immunoprophyxis in this setting may be the result of in utero transmission of HBV infection, perinatal transmission related to a high inoculum, and/or the presence of surface gene escape mutants. To study the interruptive effect of HBIG before delivery in attempt to prevent intrauterine transmission of HBV, a large-scale, random-control study was conducted in China 67. In this study, nine hundred and eighty HBsAg carrier pregnant women were randomly divided into HBIG group and control group. Each subject in the HBIG group received 200 IU or 400 IU of HBIG intramuscularly at 3, 2 and 1 month before delivery, in addition to newborns receiving HBIG intramuscularly. By this way, the rate of intrauterine transmission in this group fall to 5.7%, compared to 14.3% in control group. (P < 0.001). However, the preventive effect of HBIG administration before delivery needs to be confirmed by more study in the future.

Hepatitis B immune globulin remains a central component of prophylaxis in HBV-infected patients undergoing liver transplantation. HBIG monotherapy given at a high dosage can prevent recurrence in 65% to 80% of patients. Because the cost of long-term prophylaxis with high-dose HBIG is extremely high and combination therapy using HBIG with a nucleoside analog is more uniformly effective, the current protocol is combination HBIG with a nucleoside analog after liver transplantation. These combination protocols have reduced the rate of virologic breakthrough to 10% or less 68.

Active Immunization

Prevention of primary infection by vaccination is an important strategy to decrease the risk of chronic HBV infection and its subsequent complications. The first-generation hepatitis B vaccine, an inactive plasma-derived vaccine, became available in 1982. Consequently, the second generation of HB vaccine, a DNA recombinant HB vaccine was also available for general use in 1986. Both of the vaccines were proven to be safe and efficacious in preventing HBV infection. In 1991, the World Health Organization (WHO) recommended that hepatitis B vaccination should be included in national immunization system in all countries with a hepatitis B carrier prevalence (HBsAg) of 8% or greater by 1995 and in all countries by 1997. By May 2002, 154 countries had routine infant immunization with hepatitis B vaccine 69.

The world's first universal vaccination program for HBV infection was launched in 1984 in Taiwan 70-73. During the first 2 years of the program, coverage was provided mainly for infants whose mothers were carriers of HBsAg. Vaccination was subsequently extended, first to all newborns and then to unvaccinated preschool-age and elementary school-age children. Since 1991, catch-up vaccinations have been given to children in the first grade. This program reduced the overall HBsAg prevalence rate from 9.8% in 1984 to 1.3% in 1994 among children <15 years of age. The HBV carrier population was further reduced through improved maternal screening 71. In 1999, vaccination rates were 80–86% for young children and higher than 90% for older children; the prevalence of HBsAg was reduced to 0.7% for children younger than 15 years of age 70. To evaluate the long-term efficacy of hepatitis B (HB) vaccination in newborns, one of the longest HB vaccine follow-up studies in the world was conducted in Shanghai, China 74. Children who were born in 1986 and immunized with hepatitis B vaccine at birth were followed up at least once a year. Serum HBsAg, anti-HBc and anti-HBs were tested. The positive rates of HBsAg in the vaccine group with the period of 16 years were 0.46%-0.97%, the average being 0.61%, which was much lower than those of baseline before vaccination and external control. The long-term efficacy of newborn vaccination was 85.42%. In countries such as Italy and the United States, the incidence of acute hepatitis B has declined dramatically during the past decade after vaccination program for HBV infection, particularly among persons in younger age group 75,76.

Universal HB vaccination was proven to be effective in the prevention of HCC in several large cohort studies in Southeast Asia. Chang et al 77 reported that the average annual incidence of HCC in children 6 to 14 years of age declined from 0.70 per 100,000 children between 1981 and 1986 to 0.57 between 1986 and 1990, and to 0.36 between 1990 and 1994 (P<0.01) in the first vaccinated cohort in Taiwan. The corresponding rates of mortality from hepatocellular carcinoma also decreased. After universal vaccination against HB in 1987 in Long'an, Guang Xi, a highly endemic area in Southern China, a birth cohort study was used to evaluate the efficacy of hepatitis B vaccination. The incidence of HCC dropped from 3.27/10,000 to 0.17/10,000, a 94.8% decrease, in the group of 0-19 year-olds. The average incidence of HCC in general population for the period from 1996 to 2002 dropped to 27.86/100, 000 from 48.18 for the period from 1969 to 1988 78. The protective effect of HBV vaccination against liver cancer in adults was investigated in a cohort study in Korea. This study suggested that the immunization with HB vaccine, even in adulthood, could reduce the risk of liver cancer 79. The decrease in the rate of HCC after universal vaccination against hepatitis B provides further evidence that HBV is a cause of HCC.

Considering anti-HBs may disappear in a substantial proportion of vaccinee after initially successful vaccination, a booster dose of vaccine, following the administration of the primary course, is recommended by most national bodies. However, is it necessary to boost after initially successful vaccination? The results of long-term follow-up studies, together with assessment of the role of immunological memory among vaccinees, now question the necessity of providing booster doses following a successful course of primary immunization. In China, a long-term follow up study on HB vaccine immune efficacy showed that within the period of 16 years, the positive rate for HBsAg of the children born in 1986 ranged between 0.46 %~0.97 % with the average being 0.61 %, which was much lower than those of the background group before vaccination, despite the rate of HBsAg positive and the geometric mean titer declined 74. It was suggested that the newborns who had been vaccinated completely by HBV vaccine at their birth are unnecessary to take the booster again within 16 years. The studies in other countries also show that protection is still maintained among vaccinees, even in HBV endemic countries, despite waning or undetectable anti-HBs levels 80-82. Long-term B-cell memory has been confirmed by demonstrating either the presence of anamnestic anti-HBs responses, or the presence of circulating B cells to produce anti-HBs by a spot-enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) 83. The accumulated data indicate that protection is dependent on immune memory, rather than declining anti-HBs responses. European Consensus Group on hepatitis B immunity recommend that following a complete course of vaccination, booster doses are unnecessary in immunocompetent persons 84.

The effectiveness of routine infant hepatitis B immunization in significantly reducing or eliminating the prevalence of chronic HBV infection has been demonstrated in a variety of countries and settings. However, there are still many challenges to achieve the goal of universal childhood immunization against hepatitis B, such as poor immunization delivery infrastructure, low coverage and lack of financial sustainability. Therefore, to continue to promote access to hepatitis B vaccines worldwide, great efforts are needed to support countries to ensure sustained funding for immunization programs.

9. Research Direction

On epidemiology of HBV, additional research using population based samples of adequate size on a consensus definition of e-CHB and using standard HBV DNA assays is needed to estimate the true prevalence of e-CHB and its associated HBV variants and the precise prevalence of occult HBV infection remains to be defined. The conventional three-dose HBV vaccine schedule is not optimal in terms of ease of implementation, record keeping, and compliance. A more immunogenic HBV vaccine that could be used in a single dose or abbreviated schedule would be a major advance and might prove useful in reducing nonresponsiveness in immunosuppressed individuals. Additionally, because the current vaccine must be given by injection, the development of an effective and safe oral HBV vaccine would be advantageous.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by a grant for the Major State Basic Research (973) Program of the People's Republic of China (No.G1999054106), the National Natural Science Foundation of China and the National Science Fund for Distinguished Young Scholars.

Biographies

Jinlin Hou, MD, is Director and Professor of Hepatology Unit and Department of Infectious Diseases, Nanfang Hospital, Southern Medical University. Dr. Hou joined the University Department of Medicine of Nanfang Hospital since July 1984. Between 1993 and 1994, he received training in HBV molecular virology in St. Mary Hospital Medical School in London, UK. Between 2000 and 2001, he was as a visiting fellow at Institute of Hepatology, London. He has been invited to deliver talks in both national and international liver conferences for his expertise in viral hepatitis. His current researches include clinical management of viral hepatitis, and molecular virology and immunology of HBV infection.

Zhihua Liu, PhD, is lecturer of Hepatology Unit and Department of Infectious Diseases. His research focuses on immune response of HBV infection and gene mutation of HBV. He has published work in international journals such as Journal Viral Hepatitis, Journal of Medical Virology, etc.

References

- 1.Hepatitis B: World Health Organization Fact Sheet 204. World Health Organization; [2000]. http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs204/en/ [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gust ID. Epidemiology of hepatitis B infection in the Western Pacific and South East Asia. Gut. 1996;38(suppl 2):S18–S23. doi: 10.1136/gut.38.suppl_2.s18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lok AS. Chronic hepatitis B. N Engl J Med. 2002;346:1682–1683. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200205303462202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mahoney FJ. Update on diagnosis, management, and prevention of hepatitis B virus infection. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1999;12:351–366. doi: 10.1128/cmr.12.2.351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lee WM. Hepatitis B infection. N Engl J Med. 1997;337:1733–1745. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199712113372406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Margolis HS, Alter MJ, Hadler SC. Hepatitis B: evolving epidemiology and implications for control. Semin Liver Dis. 1991;11:84–92. doi: 10.1055/s-2008-1040427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Alter M. Epidemiology of hepatitis B in Europe and worldwide. J Hepatol. 2003;39:S64–S69. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8278(03)00141-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Toukan A. Strategy for the control of hepatitis B virus infection in the Middle East and North Africa. Vaccine. 1990;8(suppl):S117–S121. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.McQuillan GM, Townsend TR, Fields HA, Carroll M, Leahy M, Polk BF. Seroepidemiology of hepatitis B virus infection in the United States. Am J Med. 1989;87(suppl 3A):5S–10S. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(89)90523-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Scott RM, Snitbhan R, Bancroft WH, Alter HJ, Tingpalapong M. Experimental transmission of hepatitis B virus by semen and saliva. J Infect Dis. 1980;142:67–71. doi: 10.1093/infdis/142.1.67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bancroft WH, Snitbhan R, Scott RM, Tingpalapong M, Watson WT, Tanticharoenyos P. et al. Transmission of hepatitis B virus to gibbons by exposure to human saliva containing hepatitis B surface antigen. J Infect Dis. 1977;135:79–85. doi: 10.1093/infdis/135.1.79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sevens CE, Neurath RA, Beasly RP, Szmuness W. HBeAg and anti-HBe detection by radioimmunoassay. Correlation with vertical transmission of hepatitis B virus in Taiwan. J Med Virol. 1979;3:237–241. doi: 10.1002/jmv.1890030310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Xu ZY, Liu CB, Francis DP, Purcell RH, Gun ZL, Duan SC. et al. Prevention of perinatal acquisition of hepatitis B virus carriage using vaccine: preliminary report of a random double-blind placebo-controlled and comparative trail. Pediatrics. 1985;76:713–718. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Xu D, Yan Y, Xu J, Wang W, Men K, Zhang J, Liu B. et al. A molecular epidemiology study on risk factors and mechanism of HBV intrauterine transmission. Natl J Med China. 1999;79:24–27. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yan Y, Xu D, Wang W, Liu B, Liu Z, Men K. et al. The role of placenta in hepatitis B virus intrauterine transmission. Chin J Obstet Gynecol. 1999;34:392–395. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Xu D, Yan Y, Choi BC, Xu J, Men K, Zhang J. et al. Risk factors and mechanism of transplacental transmission of hepatitis B virus: a case-control study. J Med Virol. 2002;67:20–26. doi: 10.1002/jmv.2187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Xu D, Yan Y, Zou S, Choi BC, Wang S, Liu P. et al. Role of placental tissues in the intrauterine transmission of hepatitis B virus. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2001;185:981–987. doi: 10.1067/mob.2001.117968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Xu D, Yan Y, Xu J, Men K, Liu Z, Zhang J. et al. A molecular epidemiologic study on the mechanism of intrauterine transmission of hepatitis B virus. Chin J Epidemiol. 1998;19:131–133. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wang S, Xu D, Yan Y, Shi M, Zhang J, Ma J. et al. An investigation on the risk factors of the intrauterine transmission of hepatitis B virus. Chin J Public Health. 1999;18:251–252. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lin H, Lee T, Chen D, Sung JL, Ohto H, Etoh T. et al. Transplacental leakage of HBeAg positive maternal blood as the most likely route in causing intrauterine infection with hepatitis B virus. J Pediatr. 1987;111:877–881. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(87)80210-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wang Z, Zhang J, Yang H, Li X, Wen S, Guo Y. et al. Quantitative analysis of HBV DNA level and HBeAg titer in hepatitis B surface antigen positive mothers and their babies: HBeAg passage through the placenta and the rate of decay in babies. J Med Virol. 2003;71:360–366. doi: 10.1002/jmv.10493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ohto H, Lin H, Kawana T, Etoh T, Tohysma H. Intrauterine transmission of hepatitis B virus is closely related to placental leakage. J Med Virol. 1987;21:1–6. doi: 10.1002/jmv.1890210102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hyams KC. Risks of chronicity following acute hepatitis B virus infection: a review. Clin Infect Dis. 1995;20:992–1000. doi: 10.1093/clinids/20.4.992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Alter MJ. Epidemiology and prevention of hepatitis B. Semin Liver Dis. 2003;23:39–46. doi: 10.1055/s-2003-37583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Alter M, Mast E. The epidemiology of viral hepatitis in the United States. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 1994;23:437–440. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Luo KX, Liang ZS, Yang SC, Zhou R, Meng QH, Zhu YW. et al. Etiological investigation of acute post-transfusion non-A, non-B hepatitis in China. J Med Virol. 1993;39:219–223. doi: 10.1002/jmv.1890390308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Okamoto H, Tsuda F, Sakugawa H, Sastrosoewinjo RI, Imai M, Miyakawa Y. et al. Typing hepatitis B virus by homology in nucleotide sequence: comparison of surface antigen subtypes. J Gen Virol. 1988;69:2575–2583. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-69-10-2575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Norder H, Hammas B, Lofdahl S, Courouce A-M, Magnius LO. Comparison of the amino acid sequences of nine different serotypes of hepatitis B surface antigen and genomic classification of the corresponding hepatitis B virus strains. J Gen Virol. 1992;73:1201–1208. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-73-5-1201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Naumann H, Schaefer S, Yoshida CFT, Gaspar AMC, Repp R, Gerlich WH. Identification of a new hepatitis B virus (HBV) genotype from Brazil that expresses HBV surface antigen subtype adw4. J Gen Virol. 1993;74:1627–1632. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-74-8-1627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Stuyver L, De Gendt S, Van Geyt C, Zoulim F, Fried M, Schinazi RF, Rossau R. A new genotype of hepatitis B virus: complete genome and phylogenetic relatedness. J Gen Virol. 2000;81:67–74. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-81-1-67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Arauz-Ruiz P, Norder H, Robertson BH, Magnius LO. Genotype H: a new Amerindian genotype of hepatitis B virus revealed in Central America. J Gen Virol. 2002;83:2059–2073. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-83-8-2059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zhu B, Luo KX, Hu ZQ. Establishment of a method for classification of HBV genome and it's application. Chin J Exp Clin Virol. 1999;13:309–313. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cui C, Shi J, Hui L, Xi H. et al. The dominant hepatitis B virus genotype identified in Tibet is a C/D hybrid. J Gen Virol. 2002;83:2773–2777. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-83-11-2773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Luo K, Liu Z, He H, Peng J, Liang W, Dai W. et al. The putative recombination of hepatitis B virus genotype B with pre-c/c region of genotype C. Virus Genes. 2004;29:31–41. doi: 10.1023/B:VIRU.0000032787.77837.09. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Orito E, Mizokami M, Sakugawa H, Michitaka K, Ishikawa K, Ichida T. et al. A case-control study for clinical and molecular biological differences between hepatitis B viruses of genotype B and C. Hepatology. 2001;33:218–223. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2001.20532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chu CJ, Hussain M, Lok AS. Hepatitis B virus genotype B is associated with earlier HBeAg seroconversion compared to hepatotos B genotype C. Gastroenterology. 2002;122:1756–1762. doi: 10.1053/gast.2002.33588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lindh M, Hannoun C, Dhillon AP, Norkrans G, Horal P. Core promoter mutations and genotypes in relation to viral replication and liver damage in East Asian hepatitis B virus carriers. J Infect Dis. 1999;179:775–782. doi: 10.1086/314688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ding X, Mizokami M, Yao G, Xu B, Orito E, Ueda R. et al. Hepatitis B virus genotype distribution among chronic hepatitis B virus carriers in Shanghai, China. Intervirology. 2001;44:43–47. doi: 10.1159/000050029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kao JH, Chen PJ, Lai MY, Chen DS. Hepatitis B genotypes correlate with clinical outcomes in patients with chronic hepatitis B. Gastroenterology. 2000;118:554–559. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(00)70261-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kao JH, Wu NH, Chen PJ, Lai MY, Chen DS. Hepatitis B genotypes and the response to interferon therapy. J Hepatol. 2000;33:998–1002. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8278(00)80135-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hou J, Schilling R, Janssen HLA, Luo K, Liu D, Heijtink R. et al. Genetic characteristics of hepatitis B virus and response to interferon-alfa treatment. Hepatology. submitted. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hou J, Wang Z, Cheng J, Lin Y, Lau GK, Sun J. et al. Prevalence of naturally occurring surface gene variants of hepatitis B virus in non-immunized surface antigen-negative Chinese carriers. Hepatology. 2001;34:1027–1034. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2001.28708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hu KQ. Occult hepatitis B virus infection and its clinical implications. J Viral Hepat. 2002;9:243–257. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2893.2002.00344.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Brechot C, Degos F, Luggassy C, Thiers H, Zafrani S, Franco D. et al. Hepatitis B virus DNA in patients with chronic liver disease and negative tests for hepatitis B surface antigen. N Engl J Med. 1985;312:270. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198501313120503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Brechot C, Thiers V, Kremsdorf D, Nalpas B, Pol S, Paterlini-Brechot P. Persistent hepatitis B virus infection in subjects without hepatitis B surface antigen: clinically significant or purely "occult"? Hepatology. 2001;34:194–203. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2001.25172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Funk ML, Rosenberg DM, Lok ASF. World-wide epidemiology of HBeAg-negative chronic hepatitis B and associated precore and core promoter variants. J Viral Hepat. 2002;9:52–61. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2893.2002.00304.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Peng J, Luo K, Zhu Y, Guo Y, Zhang L, Hou J. Clinical and histological characteristics of chronic hepatitis B with negative hepatitis B e-antigen. Chin Med J (Engl) 2003;116:1312–1317. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Chan HL, Leung NW, Hussain M, Wong ML, Lok AS. Hepatitis B e antigen-negative chronic hepatitis B in Hong Kong. Hepatology. 2000;31:763–768. doi: 10.1002/hep.510310330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Yoo BC, Park JW, Kim HJ, Lee DH, Cha YJ, Park SM. Precore and core promoter mutations of hepatitis B virus and hepatitis B e antigen-negative chronic hepatitis B in Korea. J Hepatol. 2003;38:98–103. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8278(02)00349-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Carman WF, Jacyna MR, Hadziyannis S, Karayiannis P, McGarvey MJ, Makris A. et al. Mutation preventing formation of hepatitis B e antigen in patients with chronic hepatitis B infection. Lancet. 1989;8663:588–591. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(89)90713-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lindh M, Anderson AS, Gusdal A. Genotypes, nt1858, and geographic origin of hepatitis B virus-large-scale analysis using a new genotyping method. J Infect Dis. 1997;175:1285–1293. doi: 10.1086/516458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Magnius LO, Norder H. Subtypes, genotypes and molecular epidemiology of the hepatitis B virus as reflected by sequence variability of the S-gene. Intervirology. 1995;38:24–34. doi: 10.1159/000150411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Buckwold VE, Xu Z, Chen M, Yen TS, Ou JH. Effects of a naturally occurring mutation in the hepatitis B virus basal core promoter on precore gene expression and viral replication. J Virol. 1996;70:5845–5851. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.9.5845-5851.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Zarski JP, Marcellin P, Cohard M, Lutz JM, Bouche C, Rais A. Comparison of anti-HBe-positive and HBe-antigen-positive chronic hepatitis B in France. French Multicentre Group. J Hepatol. 1994;20:636–640. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8278(05)80352-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Hadziyannis S. hepatitis B e antigen negative chronic hepatitis B:from clinical recognition to pathogenesis and treatment. Viral Hepatitis Rev. 1995;1:7–36. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Beasley RP, Hwang LY, Lin CC, Chien CS. Hepatocellular carcinoma and hepatitis B virus: a prospective study of 22 707 men in Taiwan. Lancet. 1981;2:1129–1133. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(81)90585-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Popper H, Gerber MA, Thung SN. The relation of hepatocellular carcinoma to infection with hepatitis B and related viruses in man and animals. Hepatology. 1982;2(Suppl):1S–9S. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Chen CJ, Yu MW, Liaw YF. Epidemiological characteristics and risk factors of hepatocellular carcinoma. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 1997;12:S294–S308. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.1997.tb00513.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Bosch FX, Ribes J, Borras J. Epidemiology of primary liver cancer. Semin Liver Dis. 1999;19:271–285. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-1007117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Lin TM, Chen CJ, Lu SN, Chang AS, Chang YC, Hsu ST. et al. Hepatitis B virus e antigen and primary hepatocellular carcinoma. Anticancer Res. 1991;11:2063–2065. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Tsai JF, Jeng JE, Ho MS, Chang WY, Hsieh MY, Lin ZY. et al. Additive effect modification of hepatitis B surface antigen and e antigen on the development of hepatocellular carcinoma. Br J Cancer. 1996;73:1498–1502. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1996.283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Yang HI, Lu SN, Liaw YF, You SL, Sun CA, Wang LY. et al. Hepatitis B e Antigen and the Risk of Hepatocellular Carcinoma. New Engl J Med. 2002;347:168–174. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa013215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Ishikawa T, Ichida T, Yamagiwa S, Sugahara S, Uehara K, Okoshi S. et al. High viral loads, serum alanine aminotransferase and gender are predictive factors for the development of hepatocellular carcinoma from viral compensated liver cirrhosis. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2001;16:1274–1281. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1746.2001.02616.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Ikeda K, Arase Y, Kobayashi M, Someya T, Saitoh S, Suzuki Y. et al. Consistently low hepatitis B virus DNA saves patients from hepatocellular carcinogenesis in HBV-related cirrhosis. A nested case-control study using 96 untreated patients. Intervirology. 2003;46:96–104. doi: 10.1159/000069744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Ohata K, Hamasaki K, Toriyama K, Ishikawa H, Nakao K, Eguchi K. High viral load is a risk factor for hepatocellular carcinoma in patients with chronic hepatitis B virus infection. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2004;19:670–675. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2004.03360.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Stevens CE, Taylor PE, Tong MJ. Yeast-recombinant hepatitis B vaccine: Efficacy with hepatitis B immune globulin in prevention of perinatal hepatitis B virus transmission. JAMA. 1987;257:2612–2616. doi: 10.1001/jama.257.19.2612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Zhu Q, Yu G, Yu H, Lu Q, Gu X, Dong Z. et al. A randomized control trial on interruption of HBV transmission in uterus. Chin Med J (Engl) 2003;116:685–687. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Terrault NA, Vyas G. Hepatitis B immune globulin preparations and use in liver transplantation. Clin Liver Dis. 2003;7:537–550. doi: 10.1016/s1089-3261(03)00045-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Lavanchy D. Hepatitis B virus epidemiology, disease burden, treatment, and current and emerging prevention and control measures. J Viral Hepat. 2004;11:97–107. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2893.2003.00487.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Ni YH, Chang MH, Huang LM, Chen HL, Hsu HY, Chiu TY. et al. Hepatitis B virus infection in children and adolescents in a hyperendemic area: 15 years after mass hepatitis B vaccination. Ann Intern Med. 2001;135:796–800. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-135-9-200111060-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Chen HL, Chang MH, Ni YH, Hsu HY, Lee PI, Lee CY. et al. Seroepidemiology of hepatitis B virus infection in children: Ten years of mass vaccination in Taiwan. JAMA. 1996;276:906–908. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Chen DS, Hsu NH, Sung JL, Hsu TC, Hsu ST, Kuo YT. et al. A mass vaccination program in Taiwan against hepatitis B virus infection in infants of hepatitis B surface antigen-carrier mothers. JAMA. 1987;257:2597–2603. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Hsu HM, Chen DS, Chuang CH, Lu JC, Jwo DM, Lee CC. et al. Efficacy of a mass hepatitis B vaccination program in Taiwan. Studies on 3464 infants of hepatitis B surface antigen-carrier mothers. JAMA. 1988;260:2231–2235. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Zhou JJ, Wu WS, Sun CM, Dai HQ, Zhou N, Liu CB. et al. Long - term evaluation of immune efficacy among newborns 16 Years after HBV vaccination. Chinese Journal of Vaccines and Immunization. 2003;9:129–133. [Google Scholar]

- 75.Goldstein ST, Alter MJ, Williams IT, Moyer LA, Judson FN, Mottram K. Incedence and risk factors for acute hepatitis B in the United States,1982-1998: implications for vaccination programs. J Infect Dis. 2002;185:713–719. doi: 10.1086/339192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Da Villa G. Rationale for the infant and adolescent vaccinatin programmes in Italy. Vaccine. 2000;18:S31–S34. doi: 10.1016/s0264-410x(99)00459-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Chang MH, Chen CJ, cLai MS. Universal hepatitis B vaccination in Taiwan and the incidence of hepatocellular carcinoma in children. Taiwan Childhood Hepatoma Study Group. N Engl J Med. 1997;336:1855–1859. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199706263362602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Li R, Yang J, Gong J, Li Y, Huang Z, Fang K. et al. Efficacy of hepatitis B vaccination on hepatitis B prevention and on hepatocellular carcinoma. Chin J Epidemiol. 2004;25:385–387. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Lee MS, Kim DH, Kim H, Lee HS, Kim CY, Park TS. et al. Hepatitis B vaccination and reduced risk of primary liver cancer among male adults: a cohort study in Korea. Int J Epidemiol. 1998;27:316–319. doi: 10.1093/ije/27.2.316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Lee PI, Lee CY, Huang LM, Chang MH. Long term efficacy of recombinant hepatitis B vaccine and risk of infection in infants borne to mothers with hepatitis B e antigen. Pediatrics. 1995;126:716–721. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(95)70398-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Wainwright RB, Bulkow LR, Parkinson AJ, Zanis C, McMahon BJ. Protection provided by hepatitis B vaccine in a Yupik Eskimo population: results of a 10-year study. J Infect Dis. 1997;175:674–677. doi: 10.1093/infdis/175.3.674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Ayerbe MC, Pe´rez-Rivilla A, ICOVAHB Group. Assessment of long-term efficacy of hepatitis B vaccine. Eur J Epidemiol. 2001;17:151–156. doi: 10.1023/a:1017922302854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Wismans P, van Hattum J, de Gast GC. et al. A prospective study of in vitro anti-HBs producing B cells (spot-ELISA) following primary and supplementary vaccination with recombinant hepatitis B vaccine in insulin-dependent diabetic patients and matched controls. J Med Virol. 1991;35:216–222. doi: 10.1002/jmv.1890350313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.European Consensus Group on Hepatitis B Immunity. Are booster immunisations needen for lifelong hepatitis B immunity? Lancet. 2000;355:561–565. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]