Abstract

Introduction

The safety and efficacy of upadacitinib 15 mg (UPA15) through week 216 was evaluated in patients with rheumatoid arthritis (RA) from the long-term extension (LTE) of the phase 3 SELECT-CHOICE study.

Methods

Patients with RA refractory to biologic disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (bDMARDs) were randomized to UPA15 or abatacept (ABA) for 24 weeks. During the open-label LTE, patients on ABA switched to UPA15 at week 24, and those on UPA15 continued treatment. The safety and efficacy of continuous UPA15, and ABA to UPA15, are summarized through week 216.

Results

The LTE was comprised of 91.4% (n = 277/303) of patients that initially received UPA15, and 89.6% (n = 277/309) that initially received ABA. Of patients on UPA15 in the LTE (n = 547), 28.3% (n = 155/547) discontinued the study drug by week 216. Relative to other adverse events of special interest, and largely consistent with previous findings at week 24, higher rates of serious infection, COVID-19, herpes zoster, and elevated creatine phosphokinase were reported, while rates of malignancy excluding nonmelanoma skin cancer (NMSC), NMSC, major adverse cardiovascular event (MACE), and venous thromboembolism (VTE) were low. Long-term safety data with UPA through week 216 aligned with previous observations and no new safety risks were identified, including in patients who switched from ABA to UPA15. Proportions of patients achieving 28-joint disease activity score based on C-reactive protein (DAS28[CRP]) < 2.6/ ≤ 3.2, clinical disease activity index (CDAI) and simple disease activity index (SDAI) low disease activity/remission, ≥ 20%/50%/70% improvement in the American College of Rheumatology (ACR20/50/70) response criteria, and Boolean remission were maintained or improved with UPA15 through week 216. Improvements in the Health Assessment Questionnaire-Disability Index (HAQ-DI), patient’s assessment of pain, and Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy-Fatigue (FACIT-F) were also maintained or improved with UPA15 through week 216. Across all efficacy endpoints, similar results were observed in patients who switched from ABA to UPA15 versus continuous UPA15. Patients with an inadequate response to ≥ 1 prior tumor necrosis factor (TNF) inhibitor (UPA15: n = 263/303, 86.8%; ABA to UPA15: n = 273/309, 88.3%) showed similar responses to the total population.

Conclusions

The long-term safety profile of UPA was consistent with previous findings and the broader RA clinical program. Compared to the primary analyses at week 24, efficacy responses were maintained or further improved with UPA15 through week 216 in patients with RA.

Trial registration, ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT03086343.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s40744-024-00694-x.

Keywords: Abatacept, Biologic disease-modifying antirheumatic drug inadequate response (bDMARD-IR), Efficacy, Janus kinase (JAK) inhibitor, Patient-reported outcomes (PROs), Rheumatoid arthritis (RA), Safety, SELECT-CHOICE, Upadacitinib

Plain Language Summary

A long-term study looked at a drug named upadacitinib to treat people with rheumatoid arthritis (RA), a disease that causes joint pain and damage. The study included patients whose RA was not improved by other injectable medicines. The study compared upadacitinib with another drug called abatacept. After 24 weeks, patients who were taking abatacept switched to upadacitinib, and patients taking upadacitinib continued on upadacitinib treatment for over 4 years. The researchers looked at how well the treatments worked over the long-term and if there were any side effects. The side effects with upadacitinib treatment in this long-term study were similar to side effects reported in previous studies with upadacitinib. The researchers also found that upadacitinib helped to lessen the symptoms of RA over time and helped patients complete their daily activities and reduced their pain and tiredness. This was true for patients who switched from abatacept to upadacitinib after 24 weeks and for patients who took upadacitinib from the start of the study. Patients who had not responded to other medicines also had similar improvements with upadacitinib. In conclusion, upadacitinib can help people with RA over the long term and no new safety risks were found.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s40744-024-00694-x.

Key Summary Points

| Why carry out this study? |

| To evaluate the long-term safety and efficacy of upadacitinib 15 mg, including in patients who switched from abatacept to upadacitinib 15 mg at week 24, through week 216 in patients with rheumatoid arthritis (RA) refractory to biologic disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs from the long-term extension of the phase 3 SELECT-CHOICE study. |

| What was learned from the study? |

| No new safety risks were identified with long-term exposure to upadacitinib 15 mg, including in those who switched from abatacept to upadacitinib 15 mg to at week 24, in patients with RA through week 216 in this study. |

| Compared to the primary analysis at week 24, improvements in the signs and symptoms of RA, as well as maintenance of efficacy for pain and function, were observed with upadacitinib 15 mg treatment through week 216 in this refractory RA population. |

| Across the efficacy endpoints assessed, similar results were observed in patients who switched from abatacept to upadacitinib 15 mg at week 24 compared to those treated continuously with upadacitinib 15 mg, as well as in patients with an inadequate response or intolerance to ≥ 1 prior tumor necrosis factor inhibitor compared to the total patient population. |

Introduction

Treatments for rheumatoid arthritis (RA) should aim to reach a target of sustained remission or low disease activity (LDA) per guidance from the American College of Rheumatology (ACR) and the European Alliance of Associations for Rheumatology (EULAR; formerly the European League Against Rheumatism) [2, 3]. Conventional synthetic disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (csDMARDs), such as methotrexate and others, are typical first-line therapies for patients with RA [2, 3]. However, the success of these first-line therapies is limited. Biologic DMARDs (bDMARDs) have been shown to be effective at treating the signs and symptoms of RA, including clinical, functional, and radiographic outcomes [4–6]; however, some patients have an inadequate response or intolerance to bDMARD therapy or have an initial positive response, which is lost over time [7–9]. Despite recent advances, there remains an unmet need for additional therapies that help patients with RA achieve their treatment goals. Janus kinase (JAK) inhibitors, a class of targeted synthetic DMARDs (tsDMARDs), have been shown to be an effective alternative for patients who have failed previous csDMARD or bDMARD therapies [10–12].

Upadacitinib, an oral and selective JAK inhibitor, has been evaluated for the treatment of RA in the SELECT phase 3 clinical program across six trials, totaling approximately 4800 patients [13–18]. In the SELECT-CHOICE trial, treatment with upadacitinib resulted in significant improvements in clinical, functional, and patient-reported outcomes (PROs) versus abatacept, a T-cell co-stimulation modulator, in patients with RA refractory to bDMARDs [18]. A better understanding of the long-term impacts of upadacitinib treatment in patients with RA may help inform treatment decisions to improve patient care. The objective of this analysis was to evaluate the long-term safety and efficacy of upadacitinib 15 mg through week 216 in patients with RA from the long-term extension (LTE) of the SELECT-CHOICE study.

Methods

Patients and Study Design

Full methodological details for the SELECT-CHOICE study (NCT03086343), including study sites and dates, methods for randomization and blinding, a complete list of inclusion and exclusion criteria, as well as the primary and secondary endpoints assessed, have been published previously [18]. In brief, adults (≥ 18 years old) with a diagnosis of RA for ≥ 3 months who met the 2010 ACR-EULAR classification criteria for RA and also had moderate-to-severe active disease (tender joint count [TJC] ≥ 6 of 68 and swollen joint count [SJC] ≥ 6 of 66, along with a high-sensitivity C-reactive protein [hs-CRP] level of ≥ 3 mg per liter) despite treatment for ≥ 3 months with ≥ 1 bDMARD (excluding abatacept) or intolerance to ≥ 1 bDMARD, were included in this study. Prior to entering the study, patients were required to have received csDMARDs for ≥ 3 months, as well as a stable dose of up to two csDMARDs for ≥ 4 weeks. Patients were excluded from the study if they had previous exposure to a JAK inhibitor or abatacept, or had a history of inflammatory joint disease other than RA.

In period 1, patients were randomized 1:1 to receive blinded oral upadacitinib 15 mg once daily or intravenous (IV) abatacept (at day 1 and weeks 2, 4, 8, 12, 16, and 20 at 500 mg in patients with a body weight < 60 kg, 750 mg in patients 60–100 kg, and 1000 mg in patients > 100 kg) up to week 24 of the study. At week 24, patients initially randomized to abatacept were switched to upadacitinib 15 mg, and those initially randomized to upadacitinib 15 mg continued on the same treatment, for up to 216 weeks (over 4 years) during the open-label LTE (period 2). Initial randomization to once daily upadacitinib 30 mg was planned at the start of the study. Due to results from other phase 3 trials of upadacitinib in RA that showed minimal incremental benefit with the higher 30 mg dose of upadacitinib, the protocol was amended to assess only the upadacitinib 15 mg dose [18]. The efficacy and safety results from the small number of patients who switched from upadacitinib 30 mg to upadacitinib 15 mg (n = 24) are not included in this analysis.

Prior to receiving the first dose of study drug, discontinuation of bDMARDs using a protocol-specified washout period was required and biologic therapies were prohibited during the trial. The switch from abatacept to upadacitinib 15 mg at week 24 of the study did not require a washout period. Stable background therapies, including csDMARDs, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, acetaminophen, or glucocorticoids, were allowed. Starting at week 12 in period 1 and at week 28 in period 2, patients who did not achieve ≥ 20% decrease in both TJC and SJC compared to baseline at two consecutive visits were permitted to change or initiate background medication(s), including protocol-specified stable background csDMARDs, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, acetaminophen, or oral or inhaled glucocorticoids [18].

This study was conducted in accordance with the International Council for Harmonisation of Technical Requirements for Pharmaceuticals for Human Use (ICH) guidelines, applicable regulations governing clinical trial conduct, and the Declaration of Helsinki 1964 and its later amendments. The trial protocol was approved by an independent ethics committee (IEC)/institutional review board (IRB) at each study site per Good Clinical Practice (GCP). The list of study investigators for SELECT-CHOICE has been published previously [18]. All patients provided written informed consent prior to screening.

Outcomes

Treatment-emergent adverse events (TEAEs) and adverse events (AEs) of special interest, were assessed through week 216, including a 30-day follow-up period. AEs of special interest included any infection, serious infection, opportunistic infection (excluding tuberculosis and herpes zoster), herpes zoster, COVID-19, COVID-19 related AE, active tuberculosis, adjudicated gastrointestinal (GI) perforation, hepatic disorder, anemia, neutropenia, lymphopenia, creatine phosphokinase (CPK) elevation, malignancy excluding nonmelanoma skin cancer (NMSC), lymphoma, NMSC, major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE; defined as non-fatal myocardial infarction, non-fatal stroke, and cardiovascular death), and venous thromboembolism (VTE; including deep vein thrombosis [DVT] and pulmonary embolism [PE]). TEAEs were defined as an AE with onset on or after the first dose of study drug and ≤ 30 days after the last dose of upadacitinib 15 mg. TEAEs were coded according to the Medical Dictionary for Regulatory Activities (MedDRA; version 22.0). All TEAEs, including laboratory-related TEAEs, were reported and graded based on the investigator’s expertise using the Rheumatology Common Toxicity Criteria (version 2.0) [19], which is consistent across the RA SELECT trials. GI perforations were adjudicated by an independent internal committee of experts to review potential events of GI perforation and adjudicate against a prespecified case definition. Any suspected cardiovascular (CV) events (including MACE and VTE) and any deaths were adjudicated by an independent, external, blinded cardiovascular adjudication committee using prespecified definitions. The standardized mortality ratio (SMR) with upadacitinib 15 mg treatment was determined with and without inclusion of COVID-19 deaths.

Laboratory parameters, including the proportion of patients meeting the criteria for potentially clinically significant laboratory changes (grade 3 or 4) based on worsening in grade at any time during the treatment period (including a single isolated incident), were evaluated. Grading of laboratory changes was based on the Rheumatology Common Toxicity Criteria (version 2.0), except for CPK and creatinine, which were graded using the Common Toxicity Criteria developed by the National Cancer Institute.

To evaluate the long-term efficacy of upadacitinib in patients with RA, indicators of disease activity and PROs were assessed through week 216. The proportions of patients achieving 28-joint disease activity score based on C-reactive protein (DAS28[CRP]) < 2.6 and ≤ 3.2 [20, 21], clinical disease activity index (CDAI) and simple disease activity index (SDAI) LDA and remission (CDAI LDA defined as ≤ 10.0 and remission as ≤ 2.8; SDAI LDA defined as ≤ 11.0 and SDAI remission as ≤ 3.3) [22], ACR-EULAR Boolean-based remission [23, 24], ≥ 20%/50%/70% improvement in the ACR response criteria (ACR20/50/70) [25, 26], and minimal clinically important difference (MCID; defined as ≤ − 0.22 and ≤ − 0.3) in the Health Assessment Questionnaire-Disability Index (HAQ-DI) [27] were assessed. In addition, mean change from baseline in the HAQ-DI (range 0–3, with a greater decrease from baseline indicating reduced disability/physical impairment) [28], the patient’s assessment of pain (visual analog scale [VAS], range 0–100 mm, with a greater decrease from baseline indicating reduced pain), and the Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy-Fatigue (FACIT-F) (range 0–52, with a greater increase from baseline indicating improved quality of life and less fatigue) [29] were also assessed.

Statistical Analysis

For this analysis, data are summarized for all randomized patients who received ≥ 1 dose of study drug and entered the LTE, with data gathered through week 216. TEAEs with upadacitinib 15 mg exposure through week 216 are summarized for patients treated with upadacitinib 15 mg continuously, for patients initially randomized to abatacept who switched to upadacitinib 15 mg at week 24 (only TEAEs during upadacitinib exposure are reported), and for patients with any upadacitinib 15 mg exposure (including those initially randomized to abatacept who switched to upadacitinib). TEAEs are reported as exposure-adjusted event rates (EAER; events per 100 patient-years [E/100 PY]), or as exposure-adjusted incidence rates (EAIR; n/100 PY) in the supplemental materials, with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) calculated using the exact method for the Poisson mean. The SMRs were estimated for the general population and calculated using the most recent World Health Organization country-age-gender-specific mortality rates through 2016; rates from China were used for Hong Kong and Taiwan and rates for Singapore were used for Malaysia. The 95% CIs for the SMRs were calculated using Byar’s approximation.

Efficacy outcomes were assessed for patients treated with upadacitinib 15 mg continuously, as well as those initially randomized to abatacept who switched to upadacitinib 15 mg at week 24 of the study. In addition to the total patient population, all efficacy outcomes were also examined in patients with a prior inadequate response or intolerance to ≥ 1 prior TNF inhibitor (TNF-IR) through week 216. Binary efficacy endpoints were analyzed using as observed (AO) and non-responder imputation (NRI), while continuous efficacy endpoints were analyzed using descriptive statistics based on AO and mixed-effect model repeated measures (MMRM).

Results

Patient Disposition

In the SELECT-CHOICE study, 303 patients received upadacitinib 15 mg treatment and 309 patients received abatacept treatment. Patient baseline demographics and clinical characteristics have been reported previously [18] and were balanced across treatment groups, including patients with prior exposure to TNF inhibitor(s). The majority of patients in this study were White (upadacitinib 15 mg: 92.2%; abatacept: 95.0%), female (upadacitinib 15 mg: 81.9%; abatacept: 82.2%), and were on average approximately 55 years of age (upadacitinib 15 mg: 55.3 years; abatacept: 55.8 years; median age for upadacitinib 15 mg and abatacept: 57.0 years). Of the total patient population, 86.8% (n = 263/303) of those treated with upadacitinib 15 mg and 88.3% (n = 273/309) of those treated with abatacept were identified as TNF-IR.

Of the patients that received upadacitinib 15 mg during the first 24 weeks of the study (period 1), 91.4% (n = 277/303) entered the LTE (period 2), while 89.6% (n = 277/309) of those that initially received abatacept entered the LTE. As reported previously [18], the most common primary reason that patients discontinued study drug prior to the LTE was due to an AE, which was slightly higher with upadacitinib 15 mg than abatacept. Of the patients who entered the LTE on upadacitinib 15 mg treatment (n = 547), 28.3% (n = 155/547) discontinued study drug by week 216, with the most common primary reason being due to an AE (9.1%; n = 50/547), followed by withdrawal of consent (5.5%; n = 30/547), lack/loss of efficacy (3.1%; n = 17/547), lost to follow-up (2.9%; n = 16/547), or other reasons (6.6%; n = 36/547) (a full list of reasons is provided in Supplementary Table 1).

Safety

In the LTE of SELECT-CHOICE, a total of 579 patients were treated with upadacitinib 15 mg, totaling 1855.0 PYs of exposure. Event rates (EAERs) and incidence rates (EAIRs) for TEAEs and AEs of special interest were generally similar among patients with any upadacitinib 15 mg exposure (n = 579; as reported below) compared to patients initially randomized to abatacept who switched to upadacitinib 15 mg at week 24 (n = 276) and patients randomized to upadacitinib 15 mg and treated continuously throughout the study (n = 303) (EAERs: Table 1; EAIRs: Supplementary Table 3). Through week 216, the EAER for overall TEAEs with any upadacitinib 15 mg exposure was 228.5 E/100 PY; urinary tract infection, COVID-19, and upper respiratory tract infection were the most frequently reported TEAEs. The rate of serious AEs was 12.8 E/100 PY and AEs leading to discontinuation of study drug was 4.2 E/100 PY.

Table 1.

Event rates per 100 patient-years for TEAEs and AEs of special interest with upadacitinib 15 mg exposure through week 216

| EAERa | Any UPA 15 mg QDb n = 579 PYs = 1855.0 |

UPA 15 QD n = 303 PYs = 987.8 |

UPA 15 mg QD Switched from ABA n = 276 PYs = 867.2 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Overall TEAEs | |||

| Any AE | 228.5 (221.6, 235.4) [4238] | 243.8 (234.1, 253.7) [2408] | 211.0 (201.5, 220.9) [1830] |

| Any serious AE | 12.8 (11.3, 14.6) [238] | 13.4 (11.2, 15.8) [132] | 12.2 (10.0, 14.8) [106] |

| Any AE leading to discontinuation of study drug | 4.2 (3.3, 5.2) [78] | 5.6 (4.2, 7.2) [55] | 2.7 (1.7, 4.0) [23] |

| All deathsc | 1.3 (0.9, 2.0) [25] | 1.8 (1.1, 2.9) [18] | 0.8 (0.3, 1.7) [7] |

| ≤ 30 days after last dose of study drug | 0.9 (0.5, 1.5) [17] | 1.3 (0.7, 2.3) [13] | 0.5 (0.1, 1.2) [4] |

| > 30 days after last dose of study drug | 0.4 (0.2, 0.8) [8] | 0.5 (0.2, 1.2) [5] | 0.3 (0.1, 1.0) [3] |

| All deaths excluding COVID-19c | 0.8 (0.5, 1.3) [15] | 1.1 (0.6, 2.0) [11] | 0.5 (0.1, 1.2) [4] |

| ≤ 30 days after last dose of study drug | 0.4 (0.2, 0.8) [8] | 0.6 (0.2, 1.3) [6] | 0.2 (0.0, 0.8) [2] |

| > 30 days after last dose of study drug | 0.4 (0.2, 0.8) [7] | 0.5 (0.2, 1.2) [5] | 0.2 (0.0, 0.8) [2] |

| TEAEs and AEs of special interest | |||

| Any infection | 73.6 (69.8, 77.7) [1366] | 77.6 (72.2, 83.3) [767] | 69.1 (63.7, 74.8) [599] |

| Serious infection | 3.6 (2.8, 4.5) [66] | 3.3 (2.3, 4.7) [33] | 3.8 (2.6, 5.3) [33] |

| Opportunistic infectiond | 0.2 (0.0, 0.5) [3] | 0.2 (0.0, 0.7) [2] | 0.1 (0.0, 0.6) [1] |

| Herpes zoster | 4.0 (3.1, 5.0) [74] | 3.4 (2.4, 4.8) [34] | 4.6 (3.3, 6.3) [40] |

| COVID-19 | 8.9 (7.6, 10.4) [165] | 9.5 (7.7, 11.6) [94] | 8.2 (6.4, 10.3) [71] |

| COVID-19-related AE | 9.8 (8.4, 11.3) [182] | 10.7 (8.8, 13.0) [106] | 8.8 (6.9, 11.0) [76] |

| Active tuberculosis | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| GI perforation (adjudicated) | < 0.1 (0.0, 0.3) [1] | 0.1 (0.0, 0.6) [1] | 0 |

| Hepatic disorder | 10.9 (9.4, 12.5) [202] | 11.7 (9.7, 14.1) [116] | 9.9 (7.9, 12.2) [86] |

| Anemia | 3.3 (2.6, 4.3) [62] | 3.8 (2.7, 5.3) [38] | 2.8 (1.8, 4.1) [24] |

| Neutropenia | 2.7 (2.0, 3.6) [51] | 2.4 (1.6, 3.6) [24] | 3.1 (2.1, 4.5) [27] |

| Lymphopenia | 1.1 (0.7, 1.7) [20] | 1.5 (0.8, 2.5) [15] | 0.6 (0.2, 1.3) [5] |

| CPK elevation | 4.5 (3.6, 5.5) [83] | 3.5 (2.5, 4.9) [35] | 5.5 (4.1, 7.3) [48] |

| Malignancy (excluding NMSC) | 0.9 (0.5, 1.4) [16] | 1.1 (0.6, 2.0) [11] | 0.6 (0.2, 1.3) [5] |

| Lymphoma | < 0.1 (0.0, 0.3) [1] | 0 | 0.1 (0.0, 0.6) [1] |

| NMSC | 0.4 (0.2, 0.8) [7] | 0.5 (0.2, 1.2) [5] | 0.2 (0.0, 0.8) [2] |

| MACE (adjudicated)e | 0.3 (0.1, 0.7) [6] | 0.5 (0.2, 1.2) [5] | 0.1 (0.0, 0.6) [1] |

| VTE (adjudicated)f | 0.4 (0.2, 0.8) [7] | 0.5 (0.2, 1.2) [5] | 0.2 (0.0, 0.8) [2] |

ABA abatacept, AE adverse event, CI confidence interval, CPK creatine phosphokinase, EAER exposure-adjusted event rate, GI gastrointestinal, MACE major adverse cardiovascular event, NMSC nonmelanoma skin cancer, PY patient-year, QD once daily, TEAE treatment-emergent adverse event, UPA upadacitinib, VTE venous thromboembolism

aData are presented as EAERs, defined as E/100 PYs (95% CI) [number of events]

bIncludes patients on continuous UPA 15 mg treatment and patients who were initially randomized to ABA who switched to UPA 15 mg at week 24

cDeaths occurring ≤ 30 days after last dose of study drug were considered treatment-emergent; deaths > 30 days after last dose of study drug were considered nontreatment emergent

dExcludes tuberculous and herpes zoster infections

eMACE defined as non-fatal myocardial infarction, non-fatal stroke, and cardiovascular death

fVTE includes deep vein thrombosis (DVT) and pulmonary embolism (PE)

AEs of special interest with upadacitinib exposure through week 216 are shown in Table 1 (EAERs) and Supplementary Table 3 (EAIRs). The EAER for malignancy excluding NMSC was 0.9 E/100 PY, with squamous cell carcinoma being the most frequently reported. The rate of NMSC was 0.4 E/100 PY, with basal cell carcinoma being the most frequently reported. Overall, 13 events of malignancy were considered serious (malignancy excluding NMSC, n = 12/16; NMSC, n = 1/7), and nine events of malignancy led to discontinuation of study drug (malignancy excluding NMSC, n = 8/16; NMSC, n = 1/7). The rates of adjudicated MACE (0.3 E/100 PY) and adjudicated VTE (0.4 E/100 PY) were relatively low with upadacitinib 15 mg exposure. MACE included three cardiovascular deaths (two sudden cardiac deaths and one fatal stroke) and three events of non-fatal stroke. Four events of MACE were considered serious and one event led to discontinuation of study drug. All VTEs were non-fatal and included one event of DVT, five events of PE, and one event of concurrent DVT and PE. Five events of VTE were considered serious and two events led to discontinuation of study drug. All patients who reported CV events had at least one CV risk factor (e.g., hypertension, diabetes mellitus, current or former tobacco/nicotine use) at baseline.

The EAER for serious infection (including COVID-19) was 3.6 E/100 PY, opportunistic infection was 0.2 E/100 PY, and herpes zoster was 4.0 E/100 PY. The majority of herpes zoster events were nonserious (98.6%; n = 73/74) and involved a single dermatome (82.8%; n = 53/64, of those with extent of involvement data). Two events of herpes zoster had ophthalmic involvement, one of which was considered serious and led to hospitalization. Of all herpes zoster events, 39.2% (n = 29/74) the dose of study drug was not changed, 55.4% (n = 41/74) study drug was interrupted, and 5.4% (n = 4/74) study drug was withdrawn. The rate of COVID-19 was 8.9 E/100 PY, while the rate of COVID-19 related AEs was 9.8 E/100 PY. For patients with treatment-emergent COVID-19 infection with any upadacitinib 15 mg exposure, 17.4% had a serious COVID-19 infection, 17.4% had a COVID-19 infection that led to hospitalization, and 6.9% had a COVID-19 infection that was fatal. However, most patients had a mild (39.6%) or moderate (43.8%) case of COVID-19 infection, which did not lead to interruption of study drug (69.4%) and study drug was rarely withdrawn (3.5%) (Supplementary Table 2). The most frequently reported serious infections after COVID-19 pneumonia and COVID-19 were pneumonia followed by urinary tract infection. The rate of elevated CPK was 4.5 E/100 PY; most events were mild to moderate in severity, asymptomatic, and transient. There were no cases of rhabdomyolysis or discontinuation of upadacitinib treatment owing to an increase in CPK. One event of adjudicated GI perforation was reported (< 0.1 E/100 PY), which was due to diverticular perforation.

In total, there were 25 deaths reported with any upadacitinib 15 mg exposure (EAERs: Table 1; EAIRs: Supplementary Table 3). Of the 17 treatment-emergent deaths (occurring ≤ 30 days after the last dose of study drug), nine were related to COVID-19; the other eight deaths were sudden cardiac death (1), cardiac failure (1), atrioventricular block (1), lung cancer (1), natural causes (1), multiple events (including septic shock, multiorgan failure, and staphylococcal bacteremia; 1), and unknown cause (2). Of the eight deaths that were nontreatment emergent (occurring > 30 days after the last dose of study drug), one was related to COVID-19; the other seven deaths were abdominal aortic aneurysm (1), brain hemorrhage (1), septic shock due to lumbar abscess (1), and unknown cause (4). For the COVID-19-related deaths (n = 10), patients were on average 65 years old, 60% of patients (n = 6/10) reported being former smokers, and 90% of patients (n = 9/10) had no record of previous COVID-19 vaccination. For patients exposed to upadacitinib 15 mg (n = 579), the SMR including COVID-19 deaths was 0.93 (95% CI: 0.54, 1.48) and the SMR excluding COVID-19 deaths was 0.44 (0.19, 0.86).

Grade 3/4 laboratory abnormalities, including hematology, clinical chemistry, and urinalysis, continued to be observed through week 216 with any upadacitinib 15 mg treatment (Table 2). The most commonly observed laboratory abnormalities were for the hematologic variables—lymphocytes (grade 3: 39.0% of patients; grade 4: 3.6%) and hemoglobin (grade 3: 12.3%; grade 4: 7.3%). Most patients with potentially clinically significant hemoglobin or lymphocyte values experienced multiple (occurring at > 1 time point) grade 3 or 4 events. Abnormalities (grade 3 and 4) for variables related to clinical chemistry and liver function were less commonly observed in patients treated with upadacitinib 15 mg (neutrophils: ≤ 1.7% of patients; ALT: ≤ 6.0%; AST: ≤ 4.8%; CPK: ≤ 2.1%; creatinine: ≤ 0.2%). Most patients with potentially clinically significant neutrophils, AST, CPK, or creatinine values experienced isolated grade 3 or 4 events (occurring at one time point), while most patients with potentially clinically significant ALT values experienced multiple events. One patient met the biochemical criteria for Hy’s law; however, it was not a confirmed case of Hy’s law given the alternate etiology (isoniazid hepatotoxicity).

Table 2.

Grade 3/4 laboratory abnormalities through week 216a

| Parameter, n (%) | Any UPA 15 mg QD n = 579 |

|

|---|---|---|

| Hemoglobin (g/L) | Grade 3 (70.0 to < 80.0 or decreased 21.0 to < 30.0) | 71 (12.3) |

| Grade 4 (< 70.0 or decreased ≥ 30.0) | 42 (7.3) | |

| Lymphocytes (10^9/L) | Grade 3 (0.5 to < 1.0) | 226 (39.0) |

| Grade 4 (< 0.5) | 21 (3.6) | |

| Neutrophils (10^9/L) | Grade 3 (0.5 to < 1.0) | 10 (1.7) |

| Grade 4 (< 0.5) | 3 (0.5) | |

| ALT (U/L) | Grade 3 (3.0 to < 8.0 × ULN) | 35 (6.0) |

| Grade 4 (> 8.0 × ULN) | 4 (0.7) | |

| AST (U/L) | Grade 3 (3.0 to < 8.0 × ULN) | 28 (4.8) |

| Grade 4 (> 8.0 × ULN) | 4 (0.7) | |

| Creatine phosphokinase (U/L) | Grade 3 (> 5.0 to 10.0 × ULN) | 12 (2.1) |

| Grade 4 (> 10.0 × ULN) | 7 (1.2) | |

| Creatinine (μMol/L) | Grade 3 (> 3.0 to 6.0 × ULN) | 0 |

| Grade 4 (> 6.0 × ULN) | 1 (0.2) |

ALT alanine aminotransferase, AST aspartate aminotransferase, QD once daily, ULN upper limit of normal, UPA upadacitinib

aData for patients with worsening in grade severity compared to baseline. Grading of laboratory changes was based on the Rheumatology Common Toxicity Criteria (version 2.0), except for creatine phosphokinase and creatinine, which were graded using the Common Toxicity Criteria developed by the National Cancer Institute

Efficacy in the Total Patient Population

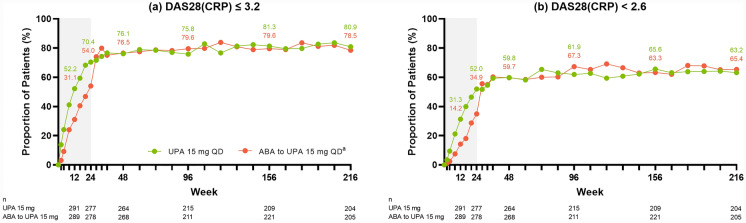

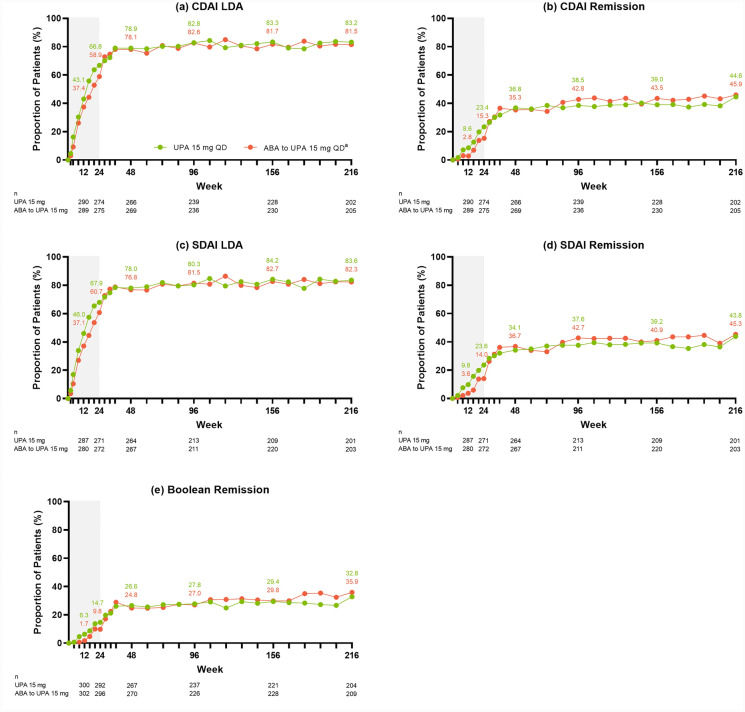

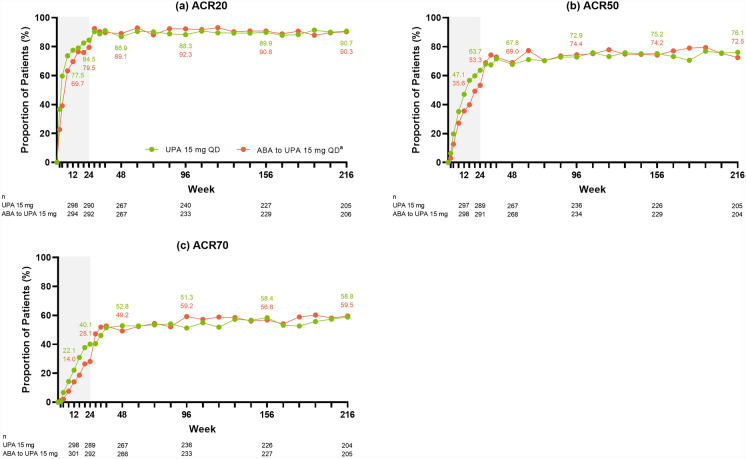

Across the efficacy endpoints assessed, improvements were observed at week 24 in patients treated with upadacitinib 15 mg (as published previously [18]), which were maintained or further improved through week 216 of the study. Specifically, of patients treated with continuous upadacitinib 15 mg, 80.9% achieved DAS28(CRP) ≤ 3.2 (AO: Fig. 1a) and 63.2% achieved DAS28(CRP) < 2.6 (AO: Fig. 1b) by week 216. Approximately 83% of patients achieved CDAI LDA (AO: Fig. 2a) and nearly 45% achieved remission (AO: Fig. 2b) at week 216; similar results were observed for SDAI LDA (AO: Fig. 2c) and remission (AO: Fig. 2d). Boolean remission was achieved by 32.8% of patients at week 216 (AO) (Fig. 2e), and a more conservative estimate using NRI showed a similar result (20.8%) (Supplementary Fig. 2e). The proportion of patients achieving ACR20/50/70 responses were maintained or further improved over time, with 90.7% of patients achieving ACR20 (AO: Fig. 3a), 76.1% achieving ACR50 (AO: Fig. 3b), and 58.8% achieving ACR70 (AO: Fig. 3c) at week 216.

Fig. 1.

Proportions of patients achieving DAS28(CRP) ≤ 3.2 or < 2.6 through week 216 (AO). aPatients randomized to ABA were switched to UPA 15 mg QD at week 24; shading indicates treatment with ABA. ABA abatacept, AO as observed, DAS28(CRP) 28-joint disease activity score based on C-reactive protein, QD once daily, UPA upadacitinib

Fig. 2.

Proportions of patients achieving CDAI LDA or remission, SDAI LDA or remission, or Boolean remission through week 216 (AO). aPatients randomized to ABA were switched to UPA 15 mg QD at week 24; shading indicates treatment with ABA. CDAI LDA defined as ≤ 10.0; CDAI remission defined as ≤ 2.8. SDAI LDA defined as ≤ 11.0; SDAI remission defined as ≤ 3.3. ABA abatacept, AO as observed, CDAI clinical disease activity index, LDA low disease activity, QD once daily, SDAI simple disease activity index, UPA upadacitinib

Fig. 3.

Proportions of patients achieving ACR20/50/70 responses through week 216 (AO). aPatients randomized to ABA were switched to UPA 15 mg QD at week 24; shading indicates treatment with ABA. ABA abatacept, ACR20/50/70 ≥ 20%/50%/70% improvement in American College of Rheumatology response criteria, AO as observed, QD once daily, UPA upadacitinib

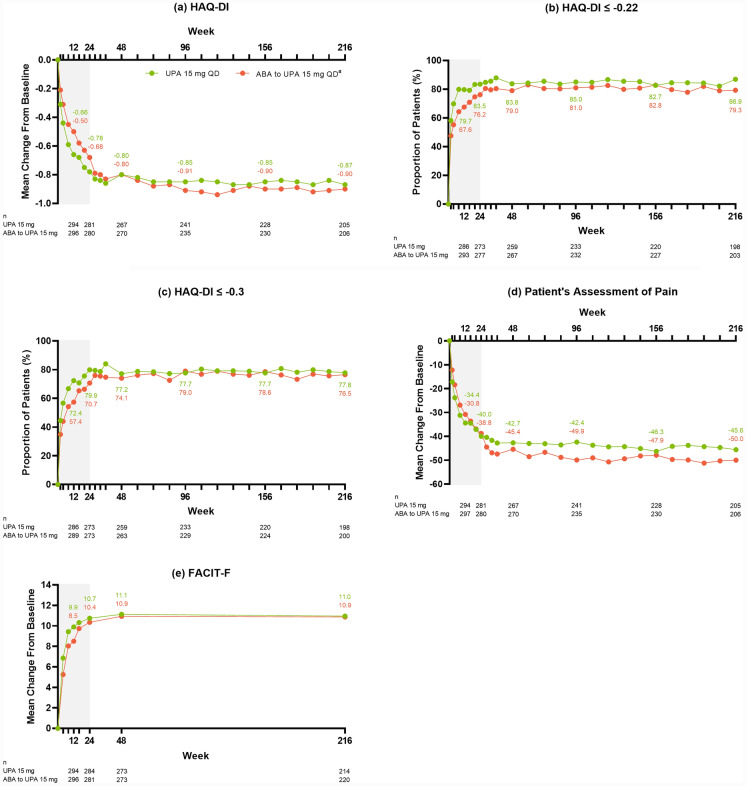

Improvements in PROs were also observed in patients with RA treated with upadacitinib 15 mg. Sustained reductions in HAQ-DI were observed following upadacitinib 15 mg treatment, demonstrating a greater reduction in disability, with a mean change from baseline of – 0.87 at week 216 (AO: Fig. 4a). The proportion of patients achieving MCID in HAQ-DI was maintained or further improved over time, with 86.9% of patients achieving ≤ - 0.22 (AO: Fig. 4b) and 77.8% achieving ≤ – 0.3 (AO: Fig. 4c) at week 216. Similarly, sustained reductions in the patient’s assessment of pain (AO: Fig. 4d) were also observed, as well as an improvement in the mean FACIT-F (AO: Fig. 4e), indicating improved quality of life and reduced fatigue, following upadacitinib 15 mg treatment.

Fig. 4.

Patient-reported outcomes through week 216 (AO). aPatients randomized to ABA were switched to UPA 15 mg QD at week 24; shading indicates treatment with ABA. ABA abatacept, AO as observed, FACIT-F Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy-Fatigue, HAQ-DI Health Assessment Questionnaire-Disability Index, QD once daily, UPA upadacitinib

For all efficacy endpoints, more conservative estimates using NRI or MMRM showed similar trends to those reported above using AO analyses (Supplementary Figs. 1–4). Furthermore, in patients initially treated with abatacept, efficacy responses quickly improved, as early as the next visit, after being switched to upadacitinib 15 mg at week 24 in the LTE (AO: Figs. 1, 2, 3, 4; NRI or MMRM: Supplementary Figs. 1–4). Across all efficacy endpoints, including the PROs of MCID in HAQ-DI and the patient’s assessment of pain, similar results were observed at week 216 in patients who were initially randomized to abatacept and switched to upadacitinib 15 mg at week 24 of the study compared to those that were treated with upadacitinib 15 mg continuously (AO: Figs. 1, 2, 3, 4; NRI or MMRM: Supplementary Figs. 1–4).

Efficacy in the TNF-IR Patient Population

Similar to the total patient population, a high proportion of TNF-IR patients (upadacitinib 15 mg: n = 263/303, 86.8%; abatacept to upadacitinib 15 mg: n = 273/309, 88.3%) treated with continuous upadacitinib 15 mg achieved DAS28(CRP) (AO and NRI: Supplementary Fig. 5a and Supplementary Fig. 5b), CDAI (AO and NRI: Supplementary Fig. 6a and Supplementary Fig. 6b), and SDAI (AO and NRI: Supplementary Fig. 6c and Supplementary Fig. 6d) endpoints. Boolean remission was achieved by 32.4% of TNF-IR patients using AO and 20.2% patients using NRI at week 216 (AO and NRI: Supplementary Fig. 6e). ACR20 (AO and NRI: Supplementary Fig. 7a), ACR50 (AO and NRI: Supplementary Fig. 7b), and ACR70 (AO and NRI: Supplementary Fig. 7c) responses were similar in the TNF-IR population compared to the total patient population, with 89.2%/75.6%/58.9% of TNF-IR patients achieving ACR20/50/70 responses at week 216 (AO). Improvements in HAQ-DI (AO, NRI, and MMRM: Supplementary Fig. 8a– 8c), as well as reductions in the patient’s assessment of pain (AO and MMRM: Supplementary Fig. 8d) and FACIT-F (AO and MMRM: Supplementary Fig. 8e) were also observed in TNF-IR patients. In alignment with the total patient population, similar results at week 216 were observed in TNF-IR patients who were initially randomized to abatacept who switched to upadacitinib 15 mg at week 24 compared to those that were treated with upadacitinib 15 mg continuously.

Discussion

The SELECT-CHOICE study evaluated the safety and efficacy of upadacitinib, an oral and selective JAK inhibitor, in patients with RA refractory to bDMARD therapy [18]. In this open-label LTE of SELECT-CHOICE, long-term safety data with continued upadacitinib 15 mg treatment through week 216 in this refractory RA population were consistent with previous short-term safety findings at week 24, as well as broader upadacitinib safety findings from across different RA populations. Additionally, efficacy outcomes, including those related to clinical, functional, and PROs, were maintained or further improved in patients treated with upadacitinib 15 mg over 4 years (216 weeks).

The long-term safety profile of upadacitinib from this study through week 216 was similar to other LTEs from the RA SELECT clinical program [30] and previously published integrated safety analyses [31, 32]. Higher rates of herpes zoster, elevated CPK, and serious infection were reported with upadacitinib relative to other AEs, which align with reports from other JAK inhibitors [33–35]. Most cases of herpes zoster were non-serious, involved a single dermatome, and rarely led to study drug being withdrawn. Of note, the upadacitinib label recommends that all patients receive herpes zoster vaccination prior to initiating therapy. Most events of elevated CPK were mild to moderate in severity, asymptomatic, and transient. The most frequently reported serious infection with any upadacitinib 15 mg exposure was COVID-19-related (i.e., COVID-19 pneumonia or COVID-19); most cases were mild to moderate in severity and rarely led to the study drug being withdrawn. However, of patients with COVID-19 infection, approximately 17% had a serious case and 7% were fatal.

Relatively low rates of malignancy excluding NMSC and NMSC were reported in this study through week 216 with upadacitinib 15 mg treatment. The findings from this study are generally similar to those reported in recent publications describing malignancy across the broader RA SELECT clinical program [31, 36]. The most frequently reported events of malignancy were basal cell carcinoma and squamous cell carcinoma with upadacitinib 15 mg exposure. JAK inhibitors, including tofacitinib and ruxolitinib, have been associated with an increased risk of NMSC in patients with immune-mediated inflammatory diseases [37–39]. Although there was no active comparator during the LTE of this study, higher rates of NMSC with upadacitinib versus comparators have been reported previously [31]. Periodic skin examinations are recommended for patients treated with JAK inhibitors, especially in those at increased risk (e.g., due to geographic location or presence of risk factors) [40]. In alignment with previous reports on the safety profile of upadacitinib in RA [31, 41], similar rates of MACE and VTE were reported in this study with upadacitinib 15 mg exposure. All patients who reported CV events had at least one CV risk factor at baseline.

In SELECT-CHOICE, there were a total of 25 deaths, of which ten were related to COVID-19. For the COVID-19 related deaths, patients were on average 65 years old, 60% of patients reported being former smokers, and 90% of patients had no record of previous COVID-19 vaccination. SMR analysis using the WHO country-age-gender-specific death data for the general population resulted in an SMR estimate for the treatment-emergent deaths of 0.93 (95% CI: 0.54, 1.48) with upadacitinib 15 mg in this study. When COVID-19 deaths were excluded, the SMR estimate was 0.44 (95% CI: 0.19, 0.86) with upadacitinib 15 mg in this study. Therefore, there is no evidence to suggest that the number of deaths in patients with RA exposed to upadacitinib 15 mg from this study was higher than would be expected in the general population. Grade 3/4 laboratory abnormalities were observed at week 24 of the SELECT-CHOICE study with upadacitinib 15 mg [18], and continued to be observed during the LTE at week 216, with abnormalities in lymphocytes and hemoglobin being the most common.

Patients treated with upadacitinib 15 mg, including those initially randomized to upadacitinib or switched from abatacept at week 24 of the study, demonstrated improvements across the efficacy endpoints assessed, which were maintained or further improved through week 216. At week 216, approximately 80% of patients achieved DAS28(CRP) < 3.2 and approximately 60% achieved DAS28(CRP) ≤ 2.6. High responses were also observed for CDAI and SDAI, with over 80% of patients achieving LDA and 40% achieving remission. Boolean remission was achieved by over 30% of patients at week 216. ACR20/50/70 responses were maintained over time, and even further improved for ACR70, over the course of the study.

A previous publication from the SELECT-CHOICE study reported significant improvement in several PROs, including Patient Global Assessment of Disease Activity (PtGA), HAQ-DI, patient’s assessment of pain, morning stiffness severity, the 36-Item Short Form Health Survey (SF-36), among others, at weeks 12 and 24 in patients with RA treated with upadacitinib 15 mg versus abatacept [42]. In this analysis of SELECT-CHOICE, improvements in physical function, as assessed using HAQ-DI, as well as a reduction in the patient’s assessment of pain were observed through week 216 of the LTE. Similar improvements in HAQ-DI and pain were also observed with upadacitinib treatment in the LTE of the SELECT-COMPARE study in RA patients who had an inadequate response to methotrexate [30]. Fatigue, as measured using FACIT-F, was also reduced with upadacitinib treatment, with these improvements maintained through week 216 of the study. This finding provides important information on the long-term (week 216) efficacy of upadacitinib on fatigue in patients, as previous SELECT studies from the RA clinical program have not measured FACIT-F through completion of the LTE. Altogether, results from this analysis of SELECT-CHOICE demonstrate that treatment with upadacitinib 15 mg resulted in sustained improvements over time across several PROs in patients with RA. A better understanding of the patient’s experience through the measurement of PROs, including those related to physical function and quality of life, can provide important information to the clinician to inform treatment decisions [43].

During the first 24 weeks of the study, patients initially randomized to upadacitinib 15 mg showed higher efficacy responses across the endpoints assessed compared to patients randomized to abatacept, as previously reported [18]. However, when patients initially treated with abatacept switched to upadacitinib 15 mg at week 24, efficacy responses quickly improved, as early as the next visit, and were comparable to the responses observed in patients initially randomized to upadacitinib 15 mg. Additionally, across all efficacy endpoints assessed, patients that were TNF-IR showed similar improvements to those observed in the total patient population, which is expected, given that nearly 90% of the total patient population was TNF-IR. Although efficacy responses were lower using NRI estimates compared to AO, the same general trends were observed using this more conservative method.

A limitation of the SELECT-CHOICE study is the lack of placebo control, as well as the lack of an active comparator beyond 24 weeks when patients initially randomized to abatacept were switched to upadacitinib 15 mg therapy. In addition, structural damage was not evaluated in this study. Furthermore, as is common to LTE studies, patients who respond well to treatment or can tolerate the study drug with minimal side effects are more likely to remain in the study [44]. Therefore, AO data may overestimate treatment efficacy, especially at later time points. To counter the inherent bias of reporting LTE data, more conservative estimates based on NRI for all efficacy endpoints are also provided in the supplemental materials. Finally, patients enrolled in this study were predominately White (> 90%) and female (> 80%), which does not necessarily reflect the diversity of the real-world RA population.

Conclusions

In the open-label LTE of the SELECT-CHOICE study, no new safety risks were identified with long-term exposure to upadacitinib 15 mg. The safety profile of upadacitinib 15 mg through week 216 is consistent with previous findings and the broader RA clinical program. Compared to the primary analysis at week 24, improvements in the signs and symptoms of RA, as well as maintenance of efficacy for pain and function were observed with upadacitinib 15 mg treatment through week 216 in this refractory RA population. These data support the long-term safety and efficacy of upadacitinib for the treatment of patients with RA. A better understanding of the long-term impacts of upadacitinib treatment on patients with RA can help inform treatment decisions to improve patient care.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

AbbVie and the authors thank the patients, study sites, and investigators who participated in this clinical trial.

Medical Writing, Editorial, and Other Assistance

Medical writing support was provided by Monica R.P. Elmore, PhD of AbbVie. Editorial support was provided by Angela T. Hadsell of AbbVie. During the preparation of this manuscript, the authors and/or medical writer used AbbVie’s Generative Artificial Intelligence to create the first draft of the Plain Language Summary (PLS). After using this tool/service, the authors and/or medical writer reviewed and edited the PLS, as needed, and take full responsibility for the content of the publication

Author Contributions

Andrea Rubbert-Roth, Koji Kato, and Heidi S. Camp participated in the design of the study. Andrea Rubbert-Roth, Boulos Haraoui, Maureen Rischmueller, and Ricardo Xavier participated in the acquisition of data. Yanxi Liu and Koji Kato participated in the analysis of data. All authors (Andrea Rubbert-Roth, Koji Kato, Boulos Haraoui, Maureen Rischmueller, Yanxi Liu, Nasser Khan, Heidi S. Camp, and Ricardo Xavier) participated in the interpretation of data and contributed to the drafting and critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content. All authors meet the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) criteria for authorship for this article, take responsibility for the integrity of the work as a whole, and have given their approval for this version to be published. No honoraria or payments were made for authorship.

Funding

AbbVie funded this trial (NCT03086343) and participated in the study design, research, analysis, data collection, interpretation of data, reviewing, and approval of the publication. AbbVie funded the journal’s Rapid Service Fee.

Data Availability

AbbVie is committed to responsible data sharing regarding the clinical trials we sponsor. This includes access to anonymized, individual, and trial-level data (analysis data sets), as well as other information (e.g., protocols, clinical study reports, or analysis plans), as long as the trials are not part of an ongoing or planned regulatory submission. This includes requests for clinical trial data for unlicensed products and indications. These clinical trial data can be requested by any qualified researchers who engage in rigorous, independent, scientific research, and will be provided following review and approval of a research proposal, Statistical Analysis Plan (SAP), and execution of a Data Sharing Agreement (DSA). Data requests can be submitted at any time after approval in the US and Europe and after acceptance of this manuscript for publication. The data will be accessible for 12 months, with possible extensions considered. For more information on the process or to submit a request, visit the following link: https://vivli.org/ourmember/abbvie/ then select “Home”.

Declarations

Conflict of Interest

Financial arrangements of the authors with companies whose products may be related to the present manuscript are listed, as declared by the authors. Andrea Rubbert-Roth has received honoraria for lectures and consulting from AbbVie, Amgen, BMS, Eli Lilly, Gilead, Janssen, Novartis, Pfizer, Roche, and Sanofi. Koji Kato is an employee of AbbVie and may hold stock or options. Boulos Haraoui has received speaker and/or consulting fees, and/or research grants, from AbbVie, Amgen, BMS, Celgene, Eli Lilly, Janssen, Merck, Novartis, Pfizer, and UCB. Maureen Rischmueller has received grant/research support from AbbVie, BMS, GSK, Janssen Global Services, Eli Lilly, Novartis, Servier, and UCB Biosciences, and consultant/speaker fees from AbbVie, Amgen, Boehringer Ingelheim, Janssen Global Services, Novartis, and Pfizer. Yanxi Liu is an employee of AbbVie and may hold stock or options. Nasser Khan is a former employee of AbbVie and may hold stock or options. Heidi S. Camp is an employee of AbbVie and may hold stock or options. Ricardo M. Xavier has received research grants from AbbVie, Eli Lilly, Janssen, UCB and Pfizer, and consultant/speaker fees from AbbVie, Sandoz, Janssen, Novartis, Pfizer, and UCB.

Ethical Approval

This study was conducted in accordance with the International Council for Harmonisation of Technical Requirements for Pharmaceuticals for Human Use (ICH) guidelines, applicable regulations governing clinical trial conduct, and the Declaration of Helsinki 1964 and its later amendments. The trial protocol was approved by an independent ethics committee (IEC)/institutional review board (IRB) at each site per Good Clinical Practice (GCP). The list of study investigators for SELECT-CHOICE has been published previously [18]. All patients provided written informed consent prior to screening.

Footnotes

Prior Publication: Week 204 data from the SELECT-CHOICE study were originally presented at the American College of Rheumatology (ACR) Convergence 2023 (San Diego, CA, USA; November 10–15, 2023) [1].

References

- 1.Rubbert-Roth A, Kato K, Haraoui B, Rischmueller M, Liu Y, Khan N, et al. Safety and efficacy of upadacitinib in patients with rheumatoid arthritis refractory to biologic DMARDs: results through week 204 from the SELECT-CHOICE study. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2023;75(suppl 9):2513–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Smolen JS, Landewé RBM, Bergstra SA, Kerschbaumer A, Sepriano A, Aletaha D, et al. EULAR recommendations for the management of rheumatoid arthritis with synthetic and biological disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs: 2022 update. Ann Rheum Dis. 2023;82:3–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fraenkel L, Bathon JM, England BR, StClair EW, Arayssi T, Carandang K, et al. 2021 American College of Rheumatology guideline for the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2021;73:1108–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lin YJ, Anzaghe M, Schulke S. Update on the pathomechanism, diagnosis, and treatment options for rheumatoid arthritis. Cells. 2020;9:880. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nam JL, Ramiro S, Gaujoux-Viala C, Takase K, Leon-Garcia M, Emery P, et al. Efficacy of biological disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs: a systematic literature review informing the 2013 update of the EULAR recommendations for the management of rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2014;73:516–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Curtis JR, Singh JA. Use of biologics in rheumatoid arthritis: current and emerging paradigms of care. Clin Ther. 2011;33:679–707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kalden JR, Schulze-Koops H. Immunogenicity and loss of response to TNF inhibitors: implications for rheumatoid arthritis treatment. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2017;13:707–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Listing J, Strangfeld A, Rau R, Kekow J, Gromnica-Ihle E, Klopsch T, et al. Clinical and functional remission: even though biologics are superior to conventional DMARDs overall success rates remain low—results from RABBIT, the German biologics register. Arthritis Res Ther. 2006;8:R66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rendas-Baum R, Wallenstein GV, Koncz T, Kosinski M, Yang M, Bradley J, et al. Evaluating the efficacy of sequential biologic therapies for rheumatoid arthritis patients with an inadequate response to tumor necrosis factor-α inhibitors. Arthritis Res Ther. 2011;13:R25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wang F, Tang X, Zhu M, Mao H, Wan H, Luo F. Efficacy and safety of JAK inhibitors for rheumatoid arthritis: a meta-analysis. J Clin Medicine. 2022;11:4459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Taylor PC. Clinical efficacy of launched JAK inhibitors in rheumatoid arthritis. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2019;58:i17-26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Venetsanopoulou AI, Voulgari PV, Drosos AA. us kinase versus TNF inhibitors: where we stand today in rheumatoid arthritis. Expert Rev Clin Immunol. 2022;18:485–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.van Vollenhoven R, Takeuchi T, Pangan AL, Friedman A, Mohamed MF, Chen S, et al. Efficacy and safety of upadacitinib monotherapy in methotrexate-naive patients with moderately-to-severely active rheumatoid arthritis (SELECT-EARLY): a multicenter, multi-country, randomized, double-blind, active comparator-controlled trial. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2020;72:1607–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Burmester GR, Kremer JM, Van den Bosch F, Kivitz A, Bessette L, Li Y, et al. Safety and efficacy of upadacitinib in patients with rheumatoid arthritis and inadequate response to conventional synthetic disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drugs (SELECT-NEXT): a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2018;391:2503–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fleischmann R, Pangan AL, Song IH, Mysler E, Bessette L, Peterfy C, et al. Upadacitinib versus placebo or adalimumab in patients with rheumatoid arthritis and an inadequate response to methotrexate: results of a phase III, double-blind, randomized controlled trial. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2019;71:1788–800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Smolen JS, Pangan AL, Emery P, Rigby W, Tanaka Y, Vargas JI, et al. Upadacitinib as monotherapy in patients with active rheumatoid arthritis and inadequate response to methotrexate (SELECT-MONOTHERAPY): a randomised, placebo-controlled, double-blind phase 3 study. Lancet. 2019;393:2303–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Genovese MC, Fleischmann R, Combe B, Hall S, Rubbert-Roth A, Zhang Y, et al. Safety and efficacy of upadacitinib in patients with active rheumatoid arthritis refractory to biologic disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drugs (SELECT-BEYOND): a double-blind, randomised controlled phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2018;391:2513–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rubbert-Roth A, Enejosa J, Pangan AL, Haraoui B, Rischmueller M, Khan N, et al. Trial of upadacitinib or abatacept in rheumatoid arthritis. N Engl J Med. 2020;383:1511–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Woodworth T, Furst DE, Alten R, Bingham CO, Bingham C, Yocum D, et al. Standardizing assessment and reporting of adverse effects in rheumatology clinical trials II: the rheumatology common toxicity criteria v.2.0. J Rheumatol. 2007;34:1401–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Prevoo MLL, van’t Hof MA, Kuper HH, van Leeuwen MA, van de Putte LBA, van Riel PLCM. Modified disease activity scores that include twenty-eight-joint counts development and validation in a prospective longitudinal study of patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 1995;38:44–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wells G, Becker J-C, Teng J, Dougados M, Schiff M, Smolen J, et al. Validation of the 28-joint disease activity score (DAS28) and European League against rheumatism response criteria based on C-reactive protein against disease progression in patients with rheumatoid arthritis, and comparison with the DAS28 based on erythrocyte sedimentation rate. Ann Rheum Dis. 2009;68:954–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Aletaha D, Smolen J. The simplified disease activity index (SDAI) and the clinical disease activity index (CDAI): a review of their usefulness and validity in rheumatoid arthritis. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2005;23:S100–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bykerk VP, Massarotti EM. The new ACR/EULAR remission criteria: rationale for developing new criteria for remission. Rheumatology. 2012;51:vi16–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Felson DT, Smolen JS, Wells G, Zhang B, van Tuyl LHD, Funovits J, et al. American College of Rheumatology/European league against rheumatism provisional definition of remission in rheumatoid arthritis for clinical trials. Ann Rheum Dis. 2011;70:404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Felson DT, Anderson JJ, Boers M, Bombardier C, Furst D, Goldsmith C, et al. American college of rheumatology preliminary definition of improvement in rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 1995;38:727–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Konzett V, Kerschbaumer A, Smolen JS, Aletaha D. Determination of the most appropriate ACR response definition for contemporary drug approval trials in rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2024;83(1):58–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Strand V, Boers M, Idzerda L, Kirwan JR, Kvien TK, Tugwell PS, et al. It’s good to feel better but it’s better to feel good and even better to feel good as soon as possible for as long as possible. Response criteria and the importance of change at OMERACT 10. J Rheumatol. 2011;38:1720–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kirwan JR, Reeback JS. Stanford health assessment questionnaire modified to assess disability in British patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Rheumatology. 1986;25:206–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cella D, Yount S, Sorensen M, Chartash E, Sengupta N, Grober J. Validation of the functional assessment of chronic illness therapy fatigue scale relative to other instrumentation in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. J Rheumatol. 2005;32:811–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fleischmann R, Mysler E, Bessette L, Peterfy CG, Durez P, Tanaka Y, et al. Long-term safety and efficacy of upadacitinib or adalimumab in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: results through 3 years from the SELECT-COMPARE study. RMD Open. 2022;8: e002012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Burmester GR, Cohen SB, Winthrop KL, Nash P, Irvine AD, Deodhar A, et al. Safety profile of upadacitinib over 15 000 patient-years across rheumatoid arthritis, psoriatic arthritis, ankylosing spondylitis and atopic dermatitis. RMD Open. 2023;9: e002735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cohen SB, van Vollenhoven RF, Winthrop KL, Zerbini CAF, Tanaka Y, Bessette L, et al. Safety profile of upadacitinib in rheumatoid arthritis: integrated analysis from the SELECT phase III clinical programme. Ann Rheum Dis. 2021;3:304–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Clarke B, Yates M, Adas M, Bechman K, Galloway J. The safety of JAK-1 inhibitors. Rheumatology. 2021;60:ii24–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Harigai M. Growing evidence of the safety of JAK inhibitors in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2019;58:i34-42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sunzini F, McInnes I, Siebert S. JAK inhibitors and infections risk: focus on herpes zoster. Ther Adv Musculoskelet Dis. 2020. 10.1177/1759720X20936059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rubbert-Roth A, Kakehasi AM, Takeuchi T, Schmalzing M, Palac H, Coombs D, et al. Malignancy in the upadacitinib clinical trials for rheumatoid arthritis, psoriatic arthritis, ankylosing spondylitis, and non-radiographic axial spondyloarthritis. Rheumatol Ther. 2023;11:97–112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wang J, Yin W, Zhou L, Zhou G, Liu K, Hu C, et al. Risk of non-melanoma skin cancer for rheumatoid arthritis patients receiving TNF antagonist: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Rheumatol. 2020;39:769–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Liu R, Wan Q, Zhao R, Xiao H, Cen Y, Xu X. Risk of non-melanoma skin cancer with biological therapy in common inflammatory diseases: a systemic review and meta-analysis. Cancer Cell Int. 2021;21:614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Jalles C, Lepelley M, Mouret S, Charles J, Leccia M-T, Trabelsi S. Skin cancers under Janus kinase inhibitors: a World Health Organization drug safety database analysis. Therapies. 2022;77:649–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Nash P, Kerschbaumer A, Dörner T, Dougados M, Fleischmann RM, Geissler K, et al. Points to consider for the treatment of immune-mediated inflammatory diseases with Janus kinase inhibitors: a consensus statement. Ann Rheum Dis. 2021;80:71–87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Charles-Schoeman C, Choy E, McInnes IB, Mysler E, Nash P, Yamaoka K, et al. MACE and VTE across upadacitinib clinical trial programmes in rheumatoid arthritis, psoriatic arthritis and ankylosing spondylitis. RMD Open. 2023;9: e003392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bergman M, Tundia N, Martin N, Suboticki JL, Patel J, Goldschmidt D, et al. Patient-reported outcomes of upadacitinib versus abatacept in patients with rheumatoid arthritis and an inadequate response to biologic disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs: 12- and 24-week results of a phase 3 trial. Arthritis Res Ther. 2022;24:155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bartlett SJ, Leon ED, Orbai A-M, Haque UJ, Manno RL, Ruffing V, et al. Patient-reported outcomes in RA care improve patient communication, decision-making, satisfaction and confidence: qualitative results. Rheumatology. 2019;59:1662–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Strangfeld A, Eveslage M, Schneider M, Bergerhausen HJ, Klopsch T, Zink A, et al. Treatment benefit or survival of the fittest: what drives the time-dependent decrease in serious infection rates under TNF inhibition and what does this imply for the individual patient? Ann Rheum Dis. 2011;70:1914. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

AbbVie is committed to responsible data sharing regarding the clinical trials we sponsor. This includes access to anonymized, individual, and trial-level data (analysis data sets), as well as other information (e.g., protocols, clinical study reports, or analysis plans), as long as the trials are not part of an ongoing or planned regulatory submission. This includes requests for clinical trial data for unlicensed products and indications. These clinical trial data can be requested by any qualified researchers who engage in rigorous, independent, scientific research, and will be provided following review and approval of a research proposal, Statistical Analysis Plan (SAP), and execution of a Data Sharing Agreement (DSA). Data requests can be submitted at any time after approval in the US and Europe and after acceptance of this manuscript for publication. The data will be accessible for 12 months, with possible extensions considered. For more information on the process or to submit a request, visit the following link: https://vivli.org/ourmember/abbvie/ then select “Home”.