Abstract

Introduction

Real-world data on ixekizumab utilization in axial spondyloarthritis (axSpA) are limited. We evaluated ixekizumab treatment patterns and health care resource utilization (HCRU) in patients with axSpA using United States Merative L.P. MarketScan® Claims Databases.

Methods

This retrospective cohort study included adults with axSpA who initiated ixekizumab during the index period (September 2019–December 2021). Index date was the date of the first ixekizumab claim. All patients had continuous medical and pharmacy enrollment during the 12-month pre-index and follow-up periods. Descriptive statistics were used to assess patient demographics (index date); clinical characteristics (pre-index period); treatment patterns (12-month follow-up period); and HCRU (pre-index and 12-month follow-up periods).

Results

The study included 177 patients (mean age 45.8 years; females 54.8%) with axSpA who initiated ixekizumab. Overall, 79.1% of patients reported prior biologic use; of these, 70.7% received tumor necrosis factor-alpha inhibitors (TNFi) and 49% received secukinumab. The mean (standard deviation [SD]) Charlson Comorbidity Index score was 1.1 (1.3) and ~ 27% of patients reported ≥2 comorbidities. The median (inter-quartile range [IQR]) number of ixekizumab prescription refills was 7 (4–11). The mean (SD) Proportion of Days Covered (PDC) for ixekizumab was 0.6 (0.3) and adherence (PDC ≥80%) was 34.5% (N = 61). Overall, 26.6% (N = 47) of patients switched to a non-index medication and 54.2% (N = 96) of patients discontinued ixekizumab. Among the patients who discontinued ixekizumab (N = 96), 19.8% (N = 19) restarted ixekizumab and 49.0% (N = 47) switched to a non-index medication. The median (IQR) ixekizumab persistence was 268 (120–366) days. Mean axSpA-related outpatient, inpatient, and emergency room visits were similar between the pre-index and follow-up periods. Treatment patterns were largely similar between biologic-experienced patients (N = 140; 79.1%) and the overall population.

Conclusions

Despite high comorbidity burden and majority of the patients being biologic-experienced, patients initiating ixekizumab for axSpA showed favorable persistence profiles during the 12-month follow-up period.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s40744-024-00710-0.

Keywords: Axial spondyloarthritis, Ixekizumab, Treatment patterns, Health Care Resource Utilization

Plain Language Summary

Axial spondyloarthritis (axSpA) affects the patients’ ability to perform daily activities and can have a major impact on their quality of life. Ixekizumab is approved in the United States for the treatment of axSpA. However, real-world data on utilization of ixekizumab are limited. We used administrative claims databases to evaluate real-world treatment patterns and health care resource utilization in adult patients with axSpA who were receiving ixekizumab in the United States. The study showed that more than a quarter of the patients receiving ixekizumab had at least two comorbidities. A majority of the patients (79%) reported that they had received at least one biologic before initiating ixekizumab. Even with the high comorbidity burden and the previous exposure to biologics, patients showed favorable persistence to ixekizumab. Of the patients who discontinued ixekizumab, subsequently, 20% re-initiated ixekizumab and approximately half of the patients switched to an alternative medication. There was no increase in axSpA-related health care resource utilization following ixekizumab treatment. The study findings suggest that ixekizumab is an effective treatment option for patients with axSpA.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s40744-024-00710-0.

Key Summary Points

| Why carry out this study? |

| Ixekizumab was approved in the United States (US) for ankylosing spondylitis (AS) in August 2019 and for non-radiographic axial spondyloarthritis (nr-axSpA) in June 2020. |

| While ixekizumab has demonstrated sustained efficacy versus placebo in AS and nr-axSpA phase 3 clinical trials, real-world data on utilization of ixekizumab in axial spondyloarthritis (axSpA; includes subtypes AS and nr-axSpA) are limited. |

| We conducted a retrospective cohort study using Merative L.P. MarketScan® Claims Databases to evaluate real-world treatment patterns and health care resource utilization (HCRU) in patients with axSpA initiating ixekizumab in the US. |

| What was learned from the study? |

| The study showed that patients receiving ixekizumab had high comorbidity burden. The majority of the patients reported use of ≥ 1 biologic, mainly tumor necrosis factor-alpha inhibitors (TNFi), before initiating ixekizumab. |

| Despite the comorbidity burden and prior biologic use, ixekizumab had favorable persistence profile during the 12-month follow-up period. Treatment patterns were largely similar between the overall population and biologic-experienced patients receiving ixekizumab. |

| The real-world data support the use of ixekizumab as an effective treatment option for the management of axSpA. |

Introduction

Axial spondyloarthritis (axSpA) is a chronic inflammatory disease affecting the spine and sacroiliac joints [1]. The estimated prevalence of axSpA in the United States (US) adult population ranges between 0.9% and 1.4% [2, 3]. The chronic inflammation in axSpA is associated with restricted spinal mobility, functional disability, and structural damage to the axial skeleton [1]. This affects the patients’ ability to perform daily activities and has a profound impact on their psychosocial well-being and quality of life [4, 5]. Functional impairment is also associated with increased health care resource utilization (HCRU) and total health care costs [6, 7].

Depending on the presence of definite radiographic sacroiliitis, axSpA is divided into two subtypes: radiographic axial spondyloarthritis (ankylosing spondylitis [AS]) and non-radiographic axial spondyloarthritis (nr-axSpA) [8, 9]. AS and nr-axSpA constitute the same disease spectrum with similar clinical presentation, disease burden, and treatment response; thus, underscoring the idea of treating axSpA as one disease [10, 11].

According to the 2022 update of the Assessment of SpondyloArthritis international Society (ASAS)-European Alliance of Associations for Rheumatology (EULAR) recommendations, the primary goal for management of axSpA is to “maximize long-term health-related quality of life through control of symptoms and inflammation, prevention of progressive structural damage, and preservation/normalization of function and social participation” [12]. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) are recommended as the first line of therapy in axSpA by both the American College of Rheumatology (ACR)/Spondylitis Association of America (SAA)/Spondyloarthritis Research and Treatment Network (SPARTAN) (2019 update) [13] and the ASAS-EULAR (2022 update) [12]. The 2019 ACR/SAA/SPARTAN update recommended tumor necrosis factor‐alpha inhibitors (TNFi) as the second line of therapy in patients with insufficient response or intolerance to NSAIDs, and interleukin-17 inhibitors (IL-17i; secukinumab or ixekizumab) as the third line of therapy in patients with primary nonresponse to the first TNFi [13]. The recent 2022 ASAS-EULAR update suggests use of TNFi, IL-17i, or Janus kinase inhibitors in patients with NSAID failure [12].

Ixekizumab, a high-affinity monoclonal antibody that selectively targets interleukin (IL)-17A, was approved in the US for AS in August 2019 and for nr-axSpA in June 2020 [14, 15]. In two phase 3 studies of ixekizumab in patients with active AS who were biological disease-modifying antirheumatic drug (bDMARD)-naïve (COAST-V) or TNFi-experienced (COAST-W), ixekizumab demonstrated sustained significant improvements in clinical disease activity, physical function, and quality of life versus placebo up to Week 52 [16]. In the phase 3 study in patients with nr-axSpA who had an inadequate response or were intolerant to NSAID therapy (COAST-X), ixekizumab was superior to placebo in improving signs and symptoms at Weeks 16 and 52 [17]. In the 2-year extension COAST-Y study following patients from COAST-V, COAST-W, and COAST-X studies, ixekizumab demonstrated sustained long-term efficacy for AS and nr-axSpA up to Week 116 [18]. While there is abundant clinical evidence on the efficacy of ixekizumab from these phase 3 studies, real-world data on utilization of ixekizumab in axSpA are limited. Here, we describe baseline characteristics, treatment patterns, and HCRU among patients with axSpA who initiated ixekizumab using claims databases in the US.

Methods

Study Design and Population

This retrospective cohort study was conducted between September 1, 2018 and December 31, 2022, using US Merative L.P. (formerly IBM®) MarketScan® Claims Databases (Commercial and Medicare Supplemental). Study variables were identified using enrollment records; service dates; International Classification of Diseases, 9th and 10th Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9/10-CM) codes; Current Procedural Technology 4th edition (CPT-4®) codes; Healthcare Common Procedure Coding System (HCPCS) codes; and National Drug Codes (NDCs), as needed.

The study included adult patients who initiated ixekizumab (index medication) between September 1, 2019 and December 31, 2021 (index period) with at least two claims (with at least one claim in the pre-index period) for AS (ICD 10–M45.x, ICD 9–720) or nr-axSpA (ICD 10–M46.8x) diagnosis. Since the ICD-10-CM code for diagnosis of nr-axSpA became available in October 2020, only a few patients with documented nr-axSpA were receiving ixekizumab in the current study. It is assumed that all patients with axSpA received a diagnosis of AS before October 2020. Therefore, patients with AS and nr-axSpA were pooled into one single axSpA group for the current analyses.

Index date was the date of the first ixekizumab prescription claim during the index period. Patients were required to have continuous medical and pharmacy enrollment in the pre-index (12 months preceding the index date and excluding the index date) and follow-up (12 months following the index date) periods. Patients were excluded if they had an ixekizumab claim during the pre-index period and had one or more diagnoses of psoriatic arthritis between the latest date of either AS or nr-axSpA diagnosis in pre-index period and the index date.

Ethical Approval

As this observational study used de-identified Merative L.P. MarketScan databases, a formal Consent to Release Information form and Ethical Review Board approval or waiver were not required. This study was conducted in accordance with the ethical principles that have their origin in the Declaration of Helsinki and that are consistent with Good Pharmacoepidemiology Practices and applicable laws and regulations of the country or countries where the study was conducted, as appropriate. Data accessed were compliant with the US patient confidentiality requirements, including the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996 regulations.

Data Sources

The Merative L.P. (formerly IBM®) MarketScan® Research Databases capture patient-level data on clinical utilization, expenditures, and enrollment across inpatient, outpatient, prescription drug, and carve-out services. The MarketScan Commercial Claims and Encounters (CCAE) Database contains data from active employees, early retirees, Consolidated Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act (COBRA) continues, and dependents insured by employer-sponsored plans (i.e., individuals not eligible for Medicare). The MarketScan Medicare Supplemental and Coordination of Benefits (COB) Database (also known as MDCR) includes data from Medicare-eligible retirees with employer-sponsored Medicare Supplemental plans. This database contains predominantly fee-for-service plan data. The MarketScan Monthly Early View Database was used for this study and included components found in the standard MarketScan Commercial and Medicare Supplemental Databases.

Study Outcomes

The primary objective was to evaluate patient demographics on the index date and clinical characteristics during the pre-index period. Treatment patterns (concomitant medication, number of index drug prescription refills, persistence, discontinuation, re-initiation after discontinuation, switching, and adherence) were assessed as secondary objectives during the 12-month follow-up period. The exploratory objective was to characterize HCRU (all-cause and axSpA-related outpatient, emergency room, and inpatient visits) at baseline and at the 12-month follow-up period. “axSpA-related” visits were defined as having either AS or nr-axSpA diagnosis in primary position on the claim.

Use of concomitant medications was defined as utilization of one or more other medications during the first 90 days after receiving ixekizumab. The number of index drug prescription refills was defined as the total number of unique, paid prescription claims of ixekizumab during the follow-up period. Persistence was defined as the number of days of continuous therapy from the point of ixekizumab initiation until the end of the follow-up period, allowing for a maximum fixed gap of 90 days between prescription refills. Patients with persistence extending till the end of follow-up were classified as persistent. Discontinuation was defined as failure to refill ixekizumab within 90 days after the depletion of the previous days’ supply or presence of an alternative advanced drug. The date of discontinuation was the date of last refill before the qualifying 90-day gap or fill date of alternative advanced drug, whichever happened earlier. Re-initiation after discontinuation was measured as proportion of patients who had ixekizumab prescription refills after the discontinuation date until the end of the study period. Switching was defined as the presence of alternative advanced drug in the follow-up period and was also measured among patients who discontinued ixekizumab. Adherence was measured using Proportion of Days Covered (PDC): number of days with ixekizumab on-hand or exposure to ixekizumab divided by the number of days in the follow-up period, regardless of discontinuation. A PDC ≥80% was defined as “adherent”. Adherence was also reported among patients who were persistent with ixekizumab.

Subgroup Analyses

The treatment patterns described above were also assessed in a subgroup of biologic-experienced patients receiving ixekizumab. Biologic-experienced patients were defined as patients who had claims for IL-17i (secukinumab), subcutaneous TNFi (adalimumab, etanercept, golimumab, and certolizumab), and intravenous TNFi (infliximab, golimumab) in the pre-index period.

Statistical Analyses

Descriptive statistics were used to assess study outcomes. Continuous variables were presented as mean and standard deviation (SD) and/or median and inter-quartile range (IQR). Categorical variables were summarized as frequencies and percentages. All the code lists were created in Instant Health Data software (Panalgo, Boston, MA, USA).

Results

Baseline Demographics and Clinical Characteristics

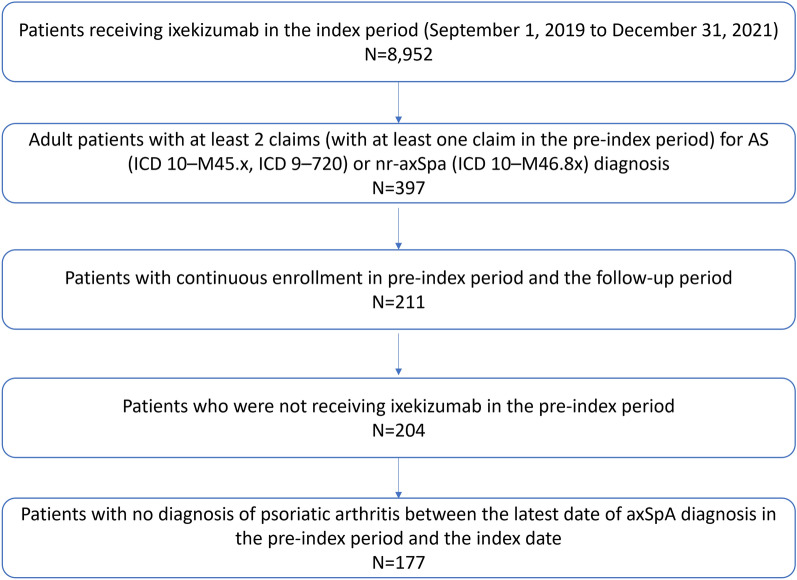

A total of 177 patients with axSpA who were receiving ixekizumab were included in the study (Fig. 1). The mean (SD) age at index was 45.8 (10.8) years and more than half of the patients were between the age group of 45 to 64 years (53.7%). The proportion of females was 54.8% and 37.3% of patients were from the US South region. Most patients (98.3%) were insured under a commercial plan (Table 1).

Fig. 1.

Patient attrition. AS ankylosing spondylitis, axSpA axial spondyloarthritis, ICD International Classification of Diseases, nr-axSpA non-radiographic axSpA

Table 1.

Baseline demographics and clinical characteristics of patients with axSpA receiving ixekizumab

| Variables | Patients with axSpA receiving ixekizumab (N = 177) |

|---|---|

| Baseline characteristics | |

| Age at index (years), mean (SD) | 45.8 (10.8) |

| Age (years), n (%) | |

| 18 to 44 | 79 (44.6) |

| 45 to 64 | 95 (53.7) |

| ≥ 65 | 3 (1.7) |

| Female, n (%) | 97 (54.8) |

| US region, n (%) | |

| South | 66 (37.3) |

| Midwest | 48 (27.1) |

| Northeast | 23 (13.0) |

| West | 15 (8.5) |

| Missing | 25 (14.1) |

| Payor at index date, n (%) | |

| Commercial | 174 (98.3) |

| Medicare | 2 (1.1) |

| Medicare advantage | 1 (0.6) |

| Clinical characteristics | |

| CCI score during pre-index period, mean (SD) | 1.1 (1.3) |

| CCI score categories, n (%) | |

| 0 | 77 (43.5) |

| 1 | 52 (29.4) |

| 2 | 23 (13.0) |

| 3 + | 25 (14.1) |

| Comorbidities, n (%) | |

| Malignancies | 21 (11.9) |

| Osteoarthritis | 55 (31.1) |

| Hyperlipidemia | 51 (28.8) |

| Obesity | 43 (24.3) |

| Cardiovascular diseasesa | 19 (10.7) |

| Osteoporosis | 13 (7.3) |

| Chronic gastritis | 9 (5.1) |

| Prior biologic useb, n (%) | 140 (79.1) |

| TNFic | 99 (70.7) |

| IL-17i (secukinumab) | 69 (49.3) |

| Prior biologic countd, mean (SD) | 1.0 (0.7) |

| Prior medication, n (%) | |

| NSAIDs | 106 (59. 9) |

| Oral corticosteroids | 93 (52.5) |

| csDMARDse | 39 (22.0) |

| Opioids | 39 (22.0) |

axSpA axial spondyloarthritis, CCI Charlson Comorbidity Index, csDMARDs conventional synthetic disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs, IL-17i interleukin-17 inhibitor, NSAIDs nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, SD standard deviation, TNFi tumor necrosis factor-alpha inhibitors, US United States

aIncludes ischemic heart disease, heart failure, stroke, angina pectoris, cerebrovascular disease, coronary artery disease, and myocardial infarction

bUse of biologics adalimumab, secukinumab, infliximab, golimumab, etanercept, or certolizumab during pre-index period

cTNFi included adalimumab, infliximab, golimumab, etanercept, and certolizumab

dNumber of unique prior biologics refilled in the pre-index period

ecsDMARDs included methotrexate and sulfasalazine

Overall, 79.1% patients reported prior biologic use; of these, 70.7% patients had exposure to TNFi, and 49.3% patients had exposure to secukinumab prior to initiating ixekizumab. More than half of the patients reported prior use of NSAIDs (59.9%) and oral corticosteroids (52.5%), and 22.0% patients reported use of conventional synthetic DMARDs (csDMARDs; methotrexate and sulfasalazine) and opioids (Table 1). The mean (SD) Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI) score during pre-index period was 1.1 (1.3) and ~ 27% of patients reported ≥2 comorbidities. The frequently reported comorbidities in addition to those in the CCI were osteoarthritis (31.1%), hyperlipidemia (28.8%), and obesity (24.3%).

Treatment Patterns During 12-Month Follow-Up Period in the Overall Population

Compared to baseline medication utilization, there was a reduction in the concomitant use of NSAIDs (36.7%), oral corticosteroids (21.5%), csDMARDs (13.0%), and opioids (6.2%) after initiating ixekizumab (Table 2).

Table 2.

Treatment patterns during the 12-month follow-up period

| Variables | Patients with axSpA receiving ixekizumab (N = 177) |

|---|---|

| Concomitant medicationa, n (%) | |

| NSAIDs | 65 (36.7) |

| Oral corticosteroids | 38 (21.5) |

| csDMARDs | 23 (13.0) |

| Opioids | 11 (6.2) |

| Number of index drug prescription refillsb | |

| Mean (SD) | 7.3 (4.0) |

| Median (IQR) | 7 (4–11) |

| Persistencec (days) | |

| Mean (SD) | 235.4 (127.3) |

| Median (IQR) | 268 (120–366) |

| Discontinuationd, n (%) | 96 (54.2) |

| Re-initiation after discontinuatione, n (%) | 19 (19.8) |

| Switching to non-index medication after discontinuationf, n (%) | 47 (49.0) |

| Proportion of days covered (PDC)g, mean (SD) | 0.6 (0.3) |

| PDC among persistent patients, mean (SD) | 0.8 (0.1) |

| Adherenceh (PDC ≥80%), n (%) | 61 (34.5) |

| Adherence (PDC ≥80%) among persistent patients, n (%) | 60 (74.1) |

| Switching to non-index medication, n (%) | 47 (26.6) |

axSpA Axial spondyloarthritis, csDMARDs conventional synthetic disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs, IQR inter-quartile range, NSAIDs nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, SD standard deviation

aUse of one or more other concomitant medications during the first 90 days after receiving ixekizumab

bThe total number of unique, paid prescription claims of ixekizumab during the follow-up period

cDays of continuous therapy from ixekizumab initiation until the end of the follow-up period, allowing for a maximum fixed gap of 90 days between prescription refills

dFailure to refill ixekizumab within 90 days after the depletion of the previous days’ supply or presence of an alternative advanced drug. For the remaining 30 patients who discontinued ixekizumab, there was no evidence of restarting ixekizumab or switching to non-index medication during the follow-up period

eProportion of patients who had ixekizumab prescription refills after the discontinuation date until the end of the study period

fPresence of alternative advanced drug in the follow-up period

gAdherence was measured using PDC: number of days with ixekizumab on-hand or exposure to ixekizumab divided by the number of days in the follow-up period, regardless of discontinuation

hPDC ≥80% was defined as “adherent”

The median (IQR) number of ixekizumab prescription refills was 7 (4–11; N = 177) (Table 2). The mean (SD) PDC for ixekizumab was 0.6 (0.3) and 34.5% of patients were adherent (PDC ≥80%). A total of 81 patients were persistent on ixekizumab and the median (IQR) persistence was 268 (120–366) days. Among these persistent patients (N = 81), the mean (SD) PDC was 0.8 (0.10) and 74.1% (N = 60) were adherent (PDC ≥80%) (Table 2). Overall, 26.6% (N = 47) of patients switched to a non-index medication during the follow-up period, and 54.2% (N = 96) of patients discontinued ixekizumab during the 90-day gap. Of the patients who discontinued (N = 96), 19.8% (N = 19) of patients restarted ixekizumab, and 49.0% (N = 47) of patients switched to a non-index medication (Table 2).

Subgroup Analyses

Of the 177 patients included in the study, 140 (79.1%) patients were biologic-experienced. Use of concomitant medication was similar to the overall patient population and included NSAIDs (35.7%), oral corticosteroids (22.9%), csDMARDs (14.3%), and opioids (7.1%). The number of ixekizumab prescription refills (median [IQR]: 6[4–11]), discontinuation rate (53.6%, N = 75), and treatment adherence (mean [SD] PDC: 0.6 [0.3]; PDC ≥ 80%: 36.4%, N = 51) were similar between the overall and biologic-experienced patients receiving ixekizumab (Supplementary Material). More patients treated with ixekizumab switched to non-index medication (32.1%) in the biologic-experienced subgroup. Among the patients who discontinued (N = 75), 16% of patients restarted ixekizumab and 60% of patients switched to a non-index medication. The median (IQR) persistence of ixekizumab was 272 (123.8–366) days. Similar to the overall population, biologic-experienced patients who were persistent on ixekizumab (N = 65) showed high PDC (mean [SD]: 0.9 [0.1]) and treatment adherence (PDC ≥80%: 76.9%, N = 50).

Health Care Resource Utilization During 12-Month Follow-Up Period

All-cause outpatient visits (mean 25.4 for pre-index and follow-up), inpatient visits (mean 0.2 for pre-index and follow-up), and emergency room visits (mean 0.4 for pre-index and follow-up) were similar between the pre-index period and the follow-up period. Likewise, axSpA-related outpatient visits (mean 4.0 for pre-index and 3.6 for follow-up), inpatient visits (mean 0.0 for pre-index and follow-up), and emergency room visits (mean 0.0 for pre-index and follow-up) were similar between the pre-index period and the follow-up period, respectively (Table 3).

Table 3.

Health care resource utilization during the 12-month follow-up period

| Variables | Patients with axSpA receiving ixekizumab (N = 177) | |

|---|---|---|

| 12-month pre-index | 12-month follow-up | |

| All-cause outpatient visits, mean (SD) | 25.4 (19.8) | 25.4 (19.0) |

| axSpA-related outpatient visits, mean (SD) | 4.0 (4.4) | 3.6 (3.8) |

| All-cause emergency room visits, mean (SD) | 0.4 (1.0) | 0.4 (0.8) |

| axSpA-related emergency room visits, mean (SD) | 0.0 (0.1) | 0.0 (0) |

| All-cause inpatient visits, mean (SD) | 0.2 (0.5) | 0.2 (0.6) |

| axSpA-related inpatient visits, mean (SD) | 0.0 (0.2) | 0.0 (0.1) |

axSpA axial spondyloarthritis, SD standard deviation

Discussion

This retrospective study utilized MarketScan Claims Databases to describe real-world treatment patterns and HCRU in patients with axSpA who were receiving ixekizumab in the US. More than a quarter of the patients reported at least two comorbidities. A majority of the patients (79%) were biologic-experienced and 71% of these patients reported prior use of TNFi in the pre-index period. Despite the comorbidity burden and prior use of biologics, patients initiating ixekizumab had favorable persistence during the 12-month follow-up period. Treatment patterns were largely similar between the overall population and biologic-experienced patients. AxSpA-related outpatient, inpatient, and emergency room visits were similar between the pre-index and the follow-up periods.

As the treatment options available for the management of axSpA are limited, treatment failures and cycling through the available bDMARDs are commonly observed [19]. In a systematic literature review and meta‑analysis of real-world evidence assessing drug survival of biologics (TNFi and IL-17i) in AS, first-line biologics showed higher drug survival compared to second- and third-line biologics [20]. Decline in treatment persistence with each line of therapy was also reported in a real-world Australian cohort of patients with AS [21]. Evidence from phase 3 studies of IL-17i in axSpA also suggests lower treatment efficacy in patients who were inadequate TNFi responders versus those who were TNFi/bDMARD naïve [16, 22]. In the current study, a majority of the patients were biologic-experienced and could potentially be more difficult-to-treat patients with prior biologic-failure. These findings support identifying optimal treatment strategies for patients with axSpA and consideration of early intervention with ixekizumab in these patients. As per the recent 2022 ASAS-EULAR recommendations, patients with persistently high disease activity despite conventional treatments should be started on TNFi or IL-17i [12]. Patients with axSpA, particularly with significant psoriasis, may benefit from IL-17i as first-line therapy [12].

In our study, 54% (N = 96) of patients discontinued ixekizumab during the 12-month follow-up period. Of the patients who discontinued (N = 96), subsequently, 20% re-initiated ixekizumab and 49% switched to a non-index medication. Unfortunately, reasons for treatment discontinuation and switching are not collected in administrative claims databases. The most common reasons for switching or discontinuation of biologics reported in the literature include inadequate response or therapeutic failure [23–25], drug cost and formulary changes [26–28], intolerance, adverse reactions, presence of multiple immune-mediated conditions [29], or patient-physician mutual decision [27]. Additionally, during the conduct of the study, the citrate-free formulation of ixekizumab was not available. The citrate-free formulation became available in August 2022 and was associated with significantly lower injection site pain and improved patient experience in clinical trials [30]. In a real-world survey, patients preferred citrate-free ixekizumab over the original formulation and were satisfied with their first injection experience. These results suggest that the citrate-free formulation may improve patient compliance [31].

The female patient population is often underrepresented in clinical trials of axSpA [32]. Overall, 55% of the patients included in this real-world study were females. Previous studies have reported lower treatment response, drug survival, and a higher number of drug switches in females with axSpA [33]. In a post hoc analysis of the phase 3 COAST studies, peak efficacy response with ixekizumab was achieved earlier in male versus female patients with axSpA. However, continued ixekizumab treatment resulted in improved response over time in female patients [34]. In the phase 3 PREVENT study, treatment response to secukinumab was relatively higher in male versus female patients with nr-axSpA [35]. This highlights the importance of conducting axSpA clinical trials stratified by sex, with a female patient population representative of the real-world [32].

While ixekizumab has demonstrated efficacy in biologic-naïve and biologic-experienced patients with axSpA in randomized placebo-controlled trials [17, 36, 37], real-world data on the use of ixekizumab are limited [38, 39]. While the current study was undertaken with the specific aim of addressing this existing gap, future studies should focus on long-term follow-up and health care costs in patients receiving ixekizumab. In addition, direct comparisons between ixekizumab and other biologic drugs in axSpA using real-world datasets can continue to deepen our understanding on the treatment effectiveness of ixekizumab [40].

The study results should be interpreted with consideration of several limitations. As with other claims-based studies, our study used data from commercially insured patients, and results may not be generalizable to all patients with axSpA. Certain comorbidities such as depression and fibromyalgia have not been reported in this study. Disease activity measures, and reasons for discontinuation and switching of ixekizumab are not captured in this administrative claims database; thus, limiting the assessment of real-world effectiveness of ixekizumab in patients with axSpA. In addition, over-the-counter use of NSAIDs or long-term use of NSAIDs or corticosteroids along with ixekizumab treatment was not captured. Nevertheless, after initiating ixekizumab, concomitant use of NSAIDs and corticosteroids reduced compared to the 12-month baseline period. Treatment patterns could not be assessed in biologic-naïve and nr-axSpA subgroups due to a low sample size.

Conclusions

Data from this real-world study suggest that patients receiving ixekizumab for axSpA had high comorbidity burden and frequent prior use of biologics, mainly TNFi. Patients initiating ixekizumab showed favorable persistence profile during the 12-month follow-up period, supporting the use of ixekizumab as an effective treatment option for management of axSpA.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

Medical Writing/Editorial Assistance

Moksha Shah of Eli Lilly Services India Pvt. Ltd provided medical writing support, which was funded by Eli Lilly and Company, Indianapolis, United States. The authors thank Marcus Ngantcha of Eli Lilly and Company for providing statistical peer review support.

Author Contributions

All named authors meet the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) criteria for authorship for this article, take responsibility for the integrity of the work as a whole, and have given their approval for this version to be published. Abhijeet Danve: Interpretation of data for the work and critical review of the work for important intellectual content. Aisha Vadhariya: Conception and design of the work, interpretation of data for the work, and critical review of the work for important intellectual content. Jeffrey Lisse: Interpretation of data for the work and critical review of the work for important intellectual content. Arjun Cholayil: Analysis of data for the work, and drafting of the work. Neha Bansal: Design of the work, analysis of data for the work, and drafting of the work. Natalia Bello: Analysis and interpretation of data for the work, drafting of the work, and critical review of the work for important intellectual content. Catherine Bakewell: Interpretation of data for the work and critical review of the work for important intellectual content.

Funding

The study and all support for the manuscript, including the journal’s Rapid Service Fee, was funded by Eli Lilly and Company, Indianapolis, United States.

Data Availability

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are not publicly available due to individual data privacy.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

Abhijeet Danve: Research Grants, Novartis, Eli Lilly; Advisory board member, Novartis, AbbVie, UCB, Janssen, and Amgen. Aisha Vadhariya, Jeffrey Lisse, Arjun Cholayil, Neha Bansal, and Natalia Bello: Employment and stockholder, Eli Lilly and Company. Catherine Bakewell: Consulting and/or speaker honoraria, AbbVie, Janssen, Lilly, Pfizer, UCB, Sanofi, and Novartis.

Ethical Approval

As this observational study used de-identified Merative L.P. MarketScan databases, a formal Consent to Release Information form and Ethical Review Board approval or waiver were not required. This study was conducted in accordance with the ethical principles that have their origin in the Declaration of Helsinki and that are consistent with Good Pharmacoepidemiology Practices and applicable laws and regulations of the country or countries where the study was conducted, as appropriate. Data accessed were compliant with the US patient confidentiality requirements, including the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996 regulations.

Footnotes

Prior Presentation: Findings from this study have been previously presented at Congress of Clinical Rheumatology West (CCR-W), San Diego, USA, held between 7 and 10 September 2023.

References

- 1.Sieper J, Poddubnyy D. Axial spondyloarthritis. Lancet. 2017;390(10089):73–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Danve A, Deodhar A. Axial spondyloarthritis in the USA: diagnostic challenges and missed opportunities. Clin Rheumatol. 2019;38(3):625–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Reveille JD, Witter JP, Weisman MH. Prevalence of axial spondylarthritis in the United States: estimates from a cross-sectional survey. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2012;64(6):905–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Strand V, Singh JA. Patient burden of axial spondyloarthritis. J Clin Rheumatol. 2017;23(7):383–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Magrey M, Walsh JA, Flierl S, Howard RA, Calheiros RC, Wei D, et al. The international map of axial spondyloarthritis survey: a US patient perspective on diagnosis and burden of disease. ACR Open Rheumatol. 2023;5(5):264–76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ogdie A, Hwang M, Veeranki P, Portelli A, Sison S, Shafrin J, et al. Association of health care utilization and costs with patient-reported outcomes in patients with ankylosing spondylitis. J Manag Care Spec Pharm. 2022;28(9):1008–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Walsh JA, Song X, Kim G, Park Y. Healthcare utilization and direct costs in patients with ankylosing spondylitis using a large US administrative claims database. Rheumatol Ther. 2018;5(2):463–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.van der Linden S, Valkenburg HA, Cats A. Evaluation of diagnostic criteria for ankylosing spondylitis. A proposal for modification of the New York criteria. Arthritis Rheum. 1984;27(4):361–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rudwaleit M, van der Heijde D, Landewé R, Listing J, Akkoc N, Brandt J, et al. The development of assessment of spondyloarthritis international Society classification criteria for axial spondyloarthritis (part II): validation and final selection. Ann Rheum Dis. 2009;68(6):777–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.López-Medina C, Ramiro S, van der Heijde D, Sieper J, Dougados M, Molto A. Characteristics and burden of disease in patients with radiographic and non-radiographic axial spondyloarthritis: a comparison by systematic literature review and meta-analysis. RMD Open. 2019;5(2):e001108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hunter T, Sandoval D, Booth N, Holdsworth E, Deodhar A. Comparing symptoms, treatment patterns, and quality of life of ankylosing spondylitis and non-radiographic axial spondyloarthritis patients in the USA: findings from a patient and rheumatologist survey. Clin Rheumatol. 2021;40(8):3161–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ramiro S, Nikiphorou E, Sepriano A, Ortolan A, Webers C, Baraliakos X, et al. ASAS-EULAR recommendations for the management of axial spondyloarthritis: 2022 update. Ann Rheum Dis. 2023;82(1):19–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ward MM, Deodhar A, Gensler LS, Dubreuil M, Yu D, Khan MA, et al. 2019 Update of the American College of Rheumatology/Spondylitis Association of America/Spondyloarthritis Research and Treatment Network Recommendations for the treatment of ankylosing spondylitis and nonradiographic axial spondyloarthritis. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2019;71(10):1599–613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lilly receives U.S. FDA approval for Taltz® (ixekizumab) for the treatment of active ankylosing spondylitis (radiographic axial spondyloarthritis). https://investor.lilly.com/news-releases/news-release-details/lilly-receives-us-fda-approval-taltzr-ixekizumab-treatment. Accessed 27 Nov 2023.

- 15.Lilly's Taltz® (ixekizumab) is the first IL-17A antagonist to receive U.S. FDA approval for the treatment of non-radiographic axial spondyloarthritis (nr-axSpA). https://investor.lilly.com/news-releases/news-release-details/lillys-taltzr-ixekizumab-first-il-17a-antagonist-receive-us-fda. Accessed 27 Nov 2023.

- 16.Dougados M, Wei JC, Landewé R, Sieper J, Baraliakos X, Van den Bosch F, et al. Efficacy and safety of ixekizumab through 52 weeks in two phase 3, randomised, controlled clinical trials in patients with active radiographic axial spondyloarthritis (COAST-V and COAST-W). Ann Rheum Dis. 2020;79(2):176–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Deodhar A, van der Heijde D, Gensler LS, Kim TH, Maksymowych WP, Østergaard M, et al. Ixekizumab for patients with non-radiographic axial spondyloarthritis (COAST-X): a randomised, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2020;395(10217):53–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Braun J, Kiltz U, Deodhar A, Tomita T, Dougados M, Bolce R, et al. Efficacy and safety of ixekizumab treatment in patients with axial spondyloarthritis: 2-year results from COAST. RMD Open. 2022;8(2):e002165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Danve A, Deodhar A. Treatment of axial spondyloarthritis: an update. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2022;18(4):205–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yu C-L, Yang C-H, Chi C-C. Drug survival of biologics in treating ankylosing spondylitis: a systematic review and meta-analysis of real-world evidence. BioDrugs. 2020;34(5):669–79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Griffiths H, Smith T, Mack C, Leadbetter J, Butcher B, Acar M, et al. Persistence to biologic therapy among patients with ankylosing spondylitis: an observational study using the OPAL dataset. J Rheumatol. 2022;49(2):150–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sieper J, Deodhar A, Marzo-Ortega H, Aelion JA, Blanco R, Jui-Cheng T, et al. Secukinumab efficacy in anti-TNF-naive and anti-TNF-experienced subjects with active ankylosing spondylitis: results from the MEASURE 2 study. Ann Rheum Dis. 2017;76(3):571–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Moral E, Plasencia C, Navarro-Compán V, Salcedo DP, Jurado T, Tornero C, et al. AB0657 Discontinuation of anti-TNF therapy in patients with axial spondyloarthritis in clinical practice: prevalence and causes. Ann Rheum Dis. 2016;75(2):1129. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Juanola X, Ramos MJM, Belzunegui JM, Fernández-Carballido C, Gratacós J. Treatment failure in axial spondyloarthritis: insights for a standardized definition. Adv Ther. 2022;39(4):1490–501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Navarro-Compan V, Plasencia-Rodriguez C, de Miguel E, Diaz Del Campo P, Balsa A, Gratacos J. Switching biological disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs in patients with axial spondyloarthritis: results from a systematic literature review. RMD Open. 2017;3(2): e000524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yi E, Dai D, Piao OW, Zheng JZ, Park Y. Health care utilization and cost associated with switching biologics within the first year of biologic treatment initiation among patients with ankylosing spondylitis. J Manag Care Spec Pharm. 2021;27(1):27–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yeaw J, Watson C, Fox KM, Schabert VF, Goodman S, Gandra SR. Treatment patterns following discontinuation of adalimumab, etanercept, and infliximab in a US managed care sample. Adv Ther. 2014;31(4):410–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Le QA, Kang JH, Lee S, Delevry D. Cost-effectiveness of treatment strategies with biologics in accordance with treatment guidelines for ankylosing spondylitis: a patient-level model. J Manag Care Spec Pharm. 2020;26(10):1219–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dougados M, Lucas J, Desfleurs E, Claudepierre P, Goupille P, Ruyssen-Witrand A, et al. Factors associated with the retention of secukinumab in patients with axial spondyloarthritis in real-world practice: results from a retrospective study (FORSYA). RMD Open. 2023;9(1):e002802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chabra S, Gill BJ, Gallo G, Zhu D, Pitou C, Payne CD, et al. Ixekizumab citrate-free formulation: results from two clinical trials. Adv Ther. 2022;39(6):2862–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chabra S, Birt J, Bolce R, Lisse J, Malatestinic WN, Zhu B, et al. Satisfaction with the injection experience of a new, citrate-free formulation of ixekizumab. Adv Ther. 2024;41(4):1672–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Marzo-Ortega H, Navarro-Compán V, Akar S, Kiltz U, Clark Z, Nikiphorou E. The impact of gender and sex on diagnosis, treatment outcomes and health-related quality of life in patients with axial spondyloarthritis. Clin Rheumatol. 2022;41(11):3573–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rusman T, van Bentum RE, van der Horst-Bruinsma IE. Sex and gender differences in axial spondyloarthritis: myths and truths. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2020;59(Suppl4):iv38–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.van der Horst-Bruinsma IE, de Vlam K, Walsh JA, Bolce R, Hunter T, Sandoval D, et al. Baseline characteristics and treatment response to ixekizumab categorised by sex in radiographic and non-radiographic axial spondylarthritis through 52 weeks: data from three phase III randomised controlled trials. Adv Ther. 2022;39(6):2806–19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Braun J, Blanco R, Marzo-Ortega H, Gensler LS, van den Bosch F, Hall S, et al. Secukinumab in non-radiographic axial spondyloarthritis: subgroup analysis based on key baseline characteristics from a randomized phase III study, PREVENT. Arthritis Res Ther. 2021;23(1):231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.van der Heijde D, Cheng-Chung Wei J, Dougados M, Mease P, Deodhar A, Maksymowych WP, et al. Ixekizumab, an interleukin-17A antagonist in the treatment of ankylosing spondylitis or radiographic axial spondyloarthritis in patients previously untreated with biological disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drugs (COAST-V): 16 week results of a phase 3 randomised, double-blind, active-controlled and placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2018;392(10163):2441–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Deodhar A, Poddubnyy D, Pacheco-Tena C, Salvarani C, Lespessailles E, Rahman P, et al. Efficacy and safety of ixekizumab in the treatment of radiographic axial spondyloarthritis: sixteen-week results from a phase III randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial in patients with prior inadequate response to or intolerance of tumor necrosis factor inhibitors. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2019;71(4):599–611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Atzeni F, Carriero A, Boccassini L, D’Angelo S. Anti-IL-17 agents in the treatment of axial spondyloarthritis. Immunotargets Ther. 2021;10:141–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Dubash S, Bridgewood C, McGonagle D, Marzo-Ortega H. The advent of IL-17A blockade in ankylosing spondylitis: secukinumab, ixekizumab and beyond. Expert Rev Clin Immunol. 2019;15(2):123–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Harrison SR, Marzo-Ortega H. Ixekizumab: an IL-17A inhibitor for the treatment of axial spondylarthritis. Expert Rev Clin Immunol. 2021;17(10):1059–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are not publicly available due to individual data privacy.