Abstract

Introduction

The therapeutic arsenal for psoriatic arthritis (PsA) is gradually being expanded, but the use of these targeted treatments must be optimal. Our objective was to guide the choice of targeted therapy to use as first-line treatment in a patient with PsA in whom methotrexate (MTX) has failed.

Methods

We searched for literature data in PubMed with the appropriate keywords for the six points of our argument: (1) the tolerance of MTX; (2) the efficacy of targeted therapies combined with MTX vs monotherapy; (3) immunogenicity of anti-tumor necrosis alpha (TNFα) monoclonal antibodies (mAbs); (4) immunogenicity of anti-interleukin (IL)-17, anti-IL-12/23, and anti-IL-23 mAbs; (5) the therapeutic maintenance of anti-TNFα mAbs when combined or not with MTX; (6) the therapeutic maintenance of anti-IL-17 vs anti-TNFα mAbs as first-line targeted therapy.

Results

The proposed rational strategy is as follows: in case of initiation of an anti-TNFα agent, maintaining treatment with MTX seems preferable, even in the absence of evidence of the superior efficacy of the combination, to avoid immunization and reduced therapeutic maintenance; in case of initiation of anti-IL-17, anti-IL-12/23, anti-IL-23 agents, or Janus kinase (JAK) inhibitors, again in the absence of evidence of the superior efficacy of the combination, discontinuing MTX therapy may be possible, at least in two steps, after verifying the efficacy of the targeted therapy initiated on the joints and skin.

Conclusion

We have data from the literature to guide the choice of targeted therapy to use as first-line treatment in a patient with PsA in whom MTX has failed.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s40744-024-00704-y.

Keywords: Psoriatic arthritis, Treatment, Methotrexate failure, First-line targeted therapy

Key Summary Points

| Why carry out the study? |

| The therapeutic arsenal for psoriatic arthritis (PsA) is gradually being expanded, notably by better identification of potential therapeutic targets, but studies of the optimal use of these targeted treatments are needed. |

| The objective of this work was to guide the choice of targeted therapy to use as first-line treatment in a patient with PsA in whom methotrexate (MTX) has failed. |

| We propose a six-point argument for a post-MTX treatment strategy in patients with PsA based on current evidence. |

| What was learned from the study? |

| In case of initiation of an anti-tumor necrosis factor alpha (anti-TNFα) agent, maintaining treatment with MTX seems preferable, even in the absence of evidence of the superior efficacy of the combination, to avoid immunization and reduced therapeutic maintenance. |

| In case of initiation of anti-IL-17, anti-IL-12/23, anti-IL-23 agents, or JAK inhibitors, again in the absence of evidence of the superior efficacy of the combination, discontinuing MTX therapy may be possible, at least in two steps, after verifying the efficacy of the targeted therapy initiated on the joints and skin. |

Introduction

Psoriatic arthritis (PsA) is a multifaceted disease, with several phenotypes conditioning the therapeutic propositions [1]. The therapeutic arsenal for PsA is gradually being expanded, notably by better identification of potential therapeutic targets, but studies of the optimal use of these targeted treatments are needed [2]. Indeed, among the biologic disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drugs (bDMARDs) are five anti-tumor necrosis factor alpha (anti-TNFα) agents [3–7], three anti-interleukin-17 (two anti-IL-17A and one anti-IL-17A/F) agents [8–10], one anti-IL-12/23 agent [11], and two anti-IL-23 agents [12, 13]. Among targeted synthetic DMARDs (tsDMARDs) are two Janus kinase inhibitors (JAKi) [14, 15] and one phosphodiesterase 4 inhibitor [16] (Fig. 1). For the peripheral arthritis phenotype, methotrexate (MTX) represents the usual first-line DMARD, despite low-level evidence of its efficacy [17]. If the treatment target is not achieved with this strategy, the recent European Alliance of Associations for Rheumatology (EULAR) recommendations indicate that a bDMARD (anti-TNFα, IL-23p40, IL-23p19, IL-17A, or IL-17A/F inhibitors) should be initiated, without preference among modes of action, and JAKi are proposed primarily after bDMARD failure; however, the proposed therapeutic choices essentially take into account extra-musculoskeletal manifestations (psoriasis, uveitis, inflammatory bowel diseases) [18]. Thus, we propose a six-point argument for a post-MTX treatment strategy in patients with PsA based on current evidence:

Fig. 1.

Marketing authorizations: r-axSpA and nr-axSpA, PsA, PsO, IBD. *Biosimilars: same indications. **Biosimilars: same indications (except pediatrics). ADA adalimumab, APRE apremilast, BKZ bimekizumab, CD Crohn’s disease, CTZ certolizumab, ETN etanercept, GLM golimumab, GUS guselkumab, IBD inflammatory bowel disease, IFX infliximab, IXE ixekizumab, nr-axSpA non-radiographic axial spondyloarthritis, PsA psoriatic arthritis, PsO psoriasis, r-axSpA radiographic axial spondyloarthritis, RIS risankizumab, SCK secukinumab, TOFA tofacitinib, UC ulcerative colitis, UPA upadacitinib, USK ustekinumab

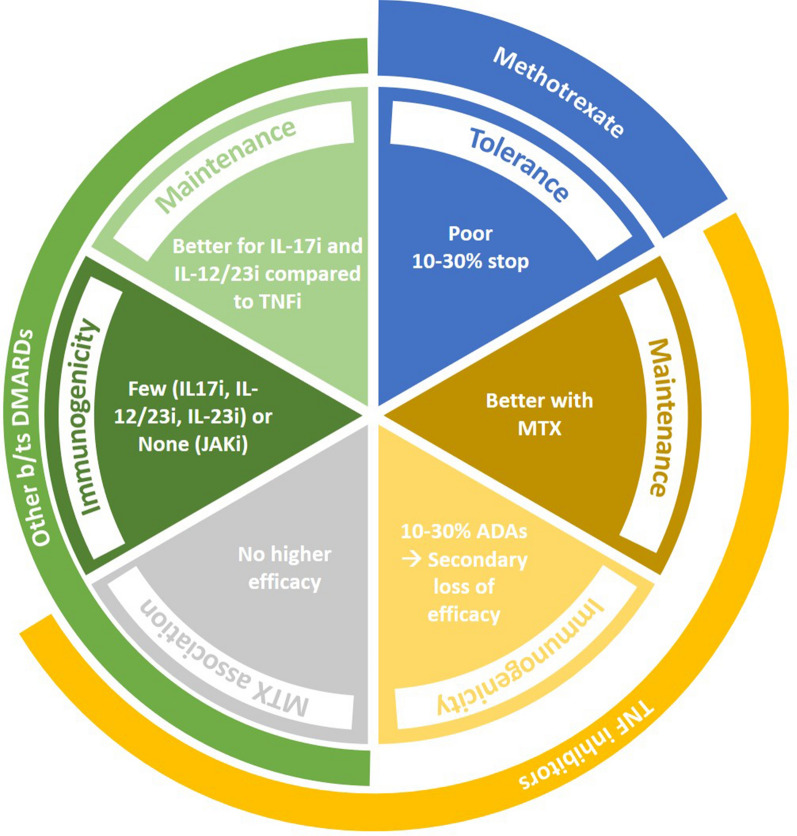

(1) The tolerance of MTX; (2) the efficacy of targeted therapies combined with MTX vs monotherapy; (3) immunogenicity of anti-TNFα monoclonal antibodies (mAbs); (4) immunogenicity of anti-IL-17, anti-IL-12/23, and anti-IL-23 mAbs; (5) the therapeutic maintenance of anti-TNFα mAbs when combined or not with MTX; (6) the therapeutic maintenance of anti-IL-17 vs anti-TNFα mAbs as first-line targeted therapy (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Six parameters to consider in order to choose targeted therapies in psoriatic arthritis. ADA anti-drug antibodies, DMARDs disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drugs, IL interleukin, JAKi janus kinase inhibitors, MTX methotrexate, TNFi tumor necrosis factor inhibitors

The objective of this work was to guide the choice of targeted therapy to use as first-line treatment in a patient with PsA in whom MTX has failed.

Methods

For the six points of our argument (Fig. 2), we searched for literature data in PubMed with the appropriate keywords (Supplementary Materials Table S1) and we have identified the most recent publications, from which we have tried to be as exhaustive as possible; this is not a systematic review of the literature (as a result, we did not use the methodology usually used for systematic reviews of the literature).

This article is based on previously conducted studies and does not contain any new studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Results of Literature Search

Poor Tolerance of MTX

Although the data are mostly for MTX used in rheumatoid arthritis (RA), the situation is similar for PsA; indeed, as for RA, the first conventional synthetic DMARD (csDMARD) recommended is MTX, even more so with associated psoriasis [1]. Thus, in RA, compliance with MTX is estimated at 60–80% [19–22], and the various international registries for follow-up of biological treatments report a monotherapy rate of about 30% of patients [23–28]. Approximately 30% of patients cannot tolerate MTX and 30% cannot tolerate a dosage > 15 mg per week [29, 30]. Overall, 10–30% of patients stop MTX because of intolerance, most often of digestive origin (nausea, abdominal pain) or alopecia, hepatic cytolysis, etc. [31, 32]. Nikiphorou et al. showed in 762 patients with RA and 193 with PsA that MTX had been stopped in 260 (34%) patients with RA and 71 (36%) patients with PsA most commonly as a result of gastrointestinal intolerability. The median duration of MTX treatment was 10 months in both groups, and overall, one-third of patients with RA and PsA stop MTX most commonly as a result of poor tolerability (this analysis did not include patients who suffer from side effects but continue therapy) [31]. Because of this poor tolerability, the possibility to stop the treatment when initiating targeted therapy would represent real added value.

The Efficacy of Targeted Therapies Combined with MTX is Not Superior to That of Monotherapy in PsA

Contrary to what is observed in RA treatment (i.e., greater efficacy of targeted therapies, especially anti-TNFα agents combined with MTX versus monotherapy), none of the targeted therapies available for PsA have shown superior efficacy when combined with MTX versus monotherapy [33–42]. A systematic review of the literature showed that the anti-TNFα–MTX combination was no more effective than anti-TNFα monotherapy in PsA [33], and this was demonstrated for each of the available products (Table 1) [4, 5, 8, 13, 34–42].

Table 1.

Efficacy of targeted therapies combined with methotrexate (MTX) or in monotherapy in psoriatic arthritis (PsA)

| Targeted therapy | Clinical response |

|---|---|

| Adalimumab [4] | ACR50 response at week 12: 36% with and without MTX |

| Etanercept [5] | PsARC response at week 12: 76% with MTX and 69% without MTX |

| Infliximab [33] | ACR50 response at week 14: 28% with MTX and 43% without MTX |

| Golimumab [34] | Reduction of DAS28-CRP at week 24: 0.7 without MTX and 1.175 with MTX |

| Certolizumab pegol [35] | ACR20 response at week 12: 61.7% with csDMARDs, 52.1% without csDMARDs |

| Secukinumab [8] | ACR20 response at week 24: 47.7% with MTX and 53.6% without MTX |

| Ixekizumab [36] | ACR50 response at week 52: 47.9% with MTX and 50.6% without MTX |

| Bimekizumab [37] | ACR50 response at week 16: 48% with and without MTX |

| Ustekinumab [38] | DAS28-ESR at week 24: 2.9 without MTX and 3.1 with MTX |

| Guselkumab [13] | ACR20 response at week 24: 62% without csDMARDs and 57% with MTX |

| Risankizumab [39] | ACR20 response at week 24: 57.9% with csDMARDs and 55.5% without csDMARDs |

| Tofacitinib [40] | No data with monotherapy for tofacitinib |

| Upadacitinib [41] | ACR50 response at week 12: 29.6% without MTX and 39.4% with MTX |

ACR American College of Rheumatology, DAS28-CRP Disease Activity Score in 28 joints–C-reactive protein, DAS28-ESR Disease Activity Score in 28 joints–erythrocyte sedimentation rate, csDMARDs conventional synthetic disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drugs, PsARC Psoriatic Arthritis Response Criteria

Anti-TNFα Monoclonal Antibodies (mAbs) are Immunogenic in PsA

Despite less data for PsA than RA, studies show that anti-TNFα mAbs can be responsible for immunization and the development of anti-drug antibodies (ADAs) in 20–30% of cases during PsA treatment. Also, as in RA, this immunization can be significantly reduced when combined with MTX [43–47] (Table 2). Three studies in patients with PsA treated with adalimumab showed the development of ADAs in 18–29% of cases, a lower serum adalimumab concentration, and poorer clinical outcome in patients with ADAs; MTX use was significantly correlated with low prevalence of ADAs [43–45] (Table 2). In the GO-REVEAL trial, the incidence of ADAs in response to golimumab at week 14 was low (4.6%), and no patient taking MTX at baseline had ADAs [46]. By week 104, 5.4% of golimumab-treated patients had ADAs, and this was less common in patients taking versus not taking MTX at baseline (1.6% vs 9.1%) [46]. In the IMPACT 2 study, only 3.6% of patients taking MTX at baseline were positive for ADAs to infliximab through week 66 as compared with 26.1% not taking MTX [47]. ACR improvement at week 54 was lower for patients with than without ADAs (22% vs 33%), and mild to moderate infusion reactions were 3.5-fold more common in patients with than without ADAs [47].

Table 2.

Immunogenicity of anti-TNF mAbs in psoriatic arthritis

| References | Product | ADAs | Impact on serum concentration and clinical response | Reduced by methotrexate |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| [43] | Adalimumab | 22% | Yes | Yes |

| [44] |

Adalimumab Infliximab |

29% 21% |

Yes | Yes |

| [45] | Adalimumab | 18% | Yes | Yes |

| [46] | Golimumab | 5% | Yes | |

| [47] | Infliximab | 26% | Yes | Yes |

ADAs anti-drug antibodies, mAbs monoclonal antibodies, TNF tumor necrosis factor

Thus, during the treatment of PsA with anti-TNFα mAbs, ADAs develop in 10–30% of patients and are associated with low serum concentrations of the drug and a secondary loss of efficacy and therefore less therapeutic maintenance. In addition, the development of ADAs is reduced when treatment is combined with MTX.

Anti-IL-17, Anti-IL-12/23, and Anti-IL-23 Antibodies are Poorly Immunogenic and JAKi Not at all Immunogenic

Unlike anti-TNFα mAbs, the other therapeutic antibodies (anti-IL17, anti-IL-12/23, and anti-IL-23) used for treating PsA are poorly immunogenic (Table 3).

Table 3.

Immunogenicity of anti-IL-17, IL-12/23, and IL-23 mAbs in psoriatic arthritis

| References | Product | Disease | ADAsa | Impact on serum concentration and clinical response | Reduced by methotrexate |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [48, 49] | Secukinumab | Psoriasis |

0.4% < 2% |

No | |

| [50] | Secukinumab | Chronic inflammatory diseases | < 1% | ||

| [51] | Secukinumab | PsA | 0.35% | No | |

| [52] | Ixekizumab | Psoriasis | 17.4% | No | |

| [53] | Ixekizumab | PsA | 10.3–12% | No | No |

| [54, 55] | Bimekizumab | Psoriasis, PsA, SpA | 31–57%b | No | |

| [50] | Ustekinumab | Chronic inflammatory diseases | 1–11% | ||

| [56] | Ustekinumab | PsA | 18.9–35% | No | No |

| [57] | Guselkumab | Psoriasis | 14.4–15.5% | No | |

| [58] | Guselkumab | PsA | 4.5% | ||

| [59] | Risankizumab |

Psoriasis PsA |

24% 12.1% |

No No |

ADAs anti-drug antibodies, IL interleukin, mAbs monoclonal antibodies, PsA psoriatic arthritis, SpA spondyloarthritis

aHeterogeneity of dosing techniques

bProbably with a very sensitive detection method

The low immunogenicity potential of secukinumab was first confirmed in psoriasis studies [48, 49]; across six phase III clinical trials, treatment-emergent ADAs (TE-ADAs) developed in 11/2842 patients (0.4%), with no association with secukinumab dose, frequency, or mode of administration [48]. In two phase III extension studies up to 5 years, TE-ADAs developed in 32/1636 (< 2%) patients, with no effect on the efficacy, safety, or pharmacokinetics of secukinumab [49]. In a systematic review of 443 study publications of chronic inflammatory diseases, secukinumab was responsible for the development of less than 1% of ADAs and ustekinumab for 1–11% [50]. TE-ADAs developed in 5 (0.35%) of 1414 patients with PsA treated with secukinumab, with no association with secukinumab dose, frequency, administration mode, secukinumab pharmacokinetics, or loss of efficacy [51].

In a phase III study of treatment with ixekizumab for moderate to severe plaque psoriasis, TE-ADAs were never detected in most patients (82.6%; 308/373) [52]. Among TE-ADA-positive patients (n = 65, 17.4%), 56 had low or moderate maximum titers, with serum concentrations and efficacy comparable to those of TE-ADA-negative patients. The median serum concentration in the high-titer TE-ADA group was in general comparable to that in the low-titer group, and for most patients, TE-ADAs had a negligible impact on ixekizumab serum concentration and efficacy [52]. In patients with PsA receiving ixekizumab (SPIRIT-P1 and -P2), among 107 patients taking MTX, 11 (10.3%) were TE-ADA-positive, 10 with low titers, and among 119 patients without MTX, 14 (12%) were TE-ADA-positive, 12 with low titers. ADAs did not affect the ixekizumab ACR20 response at week 52 [53].

In one phase IIA study of psoriasis, the incidence of anti-bimekizumab (BKZ) antibodies was 34% in the BKZ + placebo group and 47% in the BKZ group (probably with a very sensitive detection method), with no impact on drug exposure, clinical response, or safety [54]. The Summary of Product Characteristics for BKZ showed that ADAs developed in approximately 31–57% of patients, 33–44% of whom had neutralizing antibodies across indications, with no clinically meaningful impact on clinical response, and no association between immunogenicity and treatment-emergent adverse events [55].

A post hoc analysis of 112 PsA serum samples of individuals receiving open-label ustekinumab along with MTX (ustekinumab/MTX, n = 58) or placebo (ustekinumab/pbo, n = 54) revealed ADAs in 11 ustekinumab/pbo- and 19 ustekinumab/MTX-treated patients over 52 weeks (p > 0.05). At week 52, ADA-confirmed patients did not differ significantly from ADA-negative patients (p > 0.05) in safety or clinical outcomes. Thus, concomitant MTX had no significant impact on ustekinumab immunogenicity and ADA formation was not associated with impairments in ustekinumab safety, efficacy, or trough levels [56].

In 5-year data from two phase III randomized studies with guselkumab in patients with psoriasis, 111/770 (14.4%) and 146/943 (15.5%) were ADA-positive at some point through week 264 [57]. Only 5 (4.5%) and 8 (5.5%) ADA-positive patients had neutralizing antibodies equivalent (0.76% of patients receiving guselkumab with ADA-evaluable samples). Through week 264, serum guselkumab concentrations were comparable between ADA-positive and -negative patients, and the development of guselkumab ADAs did not seem to affect the clinical response [57]. In phase III pooled assays of PsA (DISCOVER 1 and 2 trials), at 1 year (DISCOVER 1), ADAs developed in 4.5% (49/1094) of patients, and at 2 years (DISCOVER 2) in 7.3% of patients [58].

For individuals receiving risankizumab for up to 52 weeks in psoriasis clinical trials, TE-ADAs and neutralizing antibodies were detected in 24% (263/1079) and 14% (150/1079), respectively. For most individuals, ADAs to risankizumab were not associated with changes in clinical response or safety. For patients receiving risankizumab for up to 28 weeks in PsA clinical trials, TE-ADAs and neutralizing antibodies were detected in 12.1% (79/652) and 0% (0/652), respectively, and were not associated with changes in clinical response or safety [59].

JAKi, which are not therapeutic antibodies but rather small chemical molecules, by definition are not immunogenic.

Thus, contrary to what is observed with anti-TNFα mAbs, the other therapeutic classes used for treating PsA (anti-IL-17, -12/23, -23) are poorly immunogenic or not at all immunogenic (JAKi). In addition, when neutralizing ADAs are produced, there is no impact on the serum concentration or clinical efficacy and therefore therapeutic maintenance. Finally, MTX does not seem to affect this immunization phenomenon.

Anti-TNFα mAbs Seem to Have Better Therapeutic Maintenance When Combined with MTX

Because of the immunogenicity of anti-TNFα mAbs and its reduction by MTX, logically, combined treatment with MTX may allow for better therapeutic maintenance during PsA treatment; this hypothesis was strongly suggested by a systematic review of the literature and data from several registries or observational studies [23, 33, 60–65].

A systematic review of the literature published in 2015 and therefore taking into account only anti-TNFα agents included therapeutic, controlled, randomized, and observational studies comparing anti-TNFα agents as monotherapy or combined with MTX, particularly regarding therapeutic maintenance, in PsA [33]. Drug survival data were reported for four registries. In the NOR-DMARD registry, concomitant MTX was associated with better 1-year TNFα antibody survival in patients with PsA, and no combination-treatment courses were discontinued as a result of lack of efficacy, whereas lack of efficacy was the reason for approximately 40% of monotherapy discontinuations [23].

In another analysis of NOR-DMARD data, patients receiving TNF inhibitors as monotherapy (n = 170) or combined with MTX (n = 270) had similar baseline characteristics, except for higher swollen joint count in the MTX than non-MTX group [60]. Drug survival analyses favored patients receiving MTX, although not significantly (p = 0.07), most prominently those receiving infliximab (p = 0.01). A similar trend was seen for adalimumab (p = 0.12, not significant, probably because of lack of power), and the difference in the etanercept group was negligible (p = 0.79). In a Cox regression analysis, lack of concomitant MTX and current smoking were independent predictors of TNF inhibitor discontinuation. Discontinuation rates were markedly higher for patients receiving infliximab as monotherapy because of adverse events (p < 0.001) [60].

The South Swedish Arthritis Treatment Group noted no baseline differences between 100 patients receiving TNF inhibitor monotherapy and 161 patients receiving concomitant MTX, other than greater non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug use in the MTX than no-MTX group [61]. Etanercept treatment and high C-reactive protein level at treatment initiation were associated with better drug survival over 7 years. The improved drug survival with concomitant MTX seemed related to significantly fewer dropouts because of adverse events [61].

In the Danish biologics registry, 54% of 410 patients with PsA were receiving concomitant MTX at baseline [62]. Baseline MTX use was more prevalent among patients receiving infliximab (70%) than adalimumab (49%) or etanercept (39%). In a Cox regression analysis, male sex, C-reactive protein level > 10 mg/l, concomitant MTX use and low visual analogue scale score for patient health at baseline were associated with longer drug survival. The adjusted hazard ratio (HR) for discontinuing the TNF inhibitor associated with lack of MTX use was 1.37 (95% CI 1.07–1.75). Lack of MTX use was associated with discontinuation due to adverse events but not lack of efficacy [62]. In contrast to the above findings, a study of the Canadian Rhumadata clinical database and registry found that concomitant MTX did not improve 5-year retention with adalimumab or etanercept (52% for combination therapy vs 67% monotherapy; p = 0.74) [63]. One study compared treatment outcomes for 15,332 patients with PsA treated with TNF inhibitor and csDMARD co-treatment (62%) versus TNF inhibitor monotherapy (38%) in patients who initiated a first TNF inhibitor in 13 European countries in 2006–2017. MTX co-medication was associated with improved remission for adalimumab and infliximab and improved retention for infliximab. No effect of co-medication was demonstrated for etanercept [64]. Finally, a prospective observational study of 82 patients with PsA receiving etanercept with or without concomitant MTX in one Italian center found no significant difference in the main demographic and clinical features, including rates of withdrawal due to inefficacy or toxicity, between patients receiving etanercept alone and those concomitant MTX therapy; concomitant MTX treatment did not seem a positive predictor of drug survival [65].

Anti-IL-17 Antibodies May Have Better Therapeutic Maintenance than Anti-TNFα Antibodies as First-Line Targeted Therapy in PsA

There are limited data on the maintenance of different targeted therapies and even less on how they compare over time in PsA. In addition, the data on persistence observed during extensions of phase III, registry, or observational studies are sometimes “optimistic”, are quite heterogeneous, and do not always reflect real life.

Maintenance of Anti-IL-17 Antibodies

In a retrospective, multicenter study of 178 patients with PsA receiving secukinumab as a first-, second-, or third-line or greater bDMARD therapy (for 37%, 21%, and 42% of patients, respectively), the overall 24-month persistence rate was 67% (95% CI 60–74). Patients receiving first-line secukinumab had the highest 24-month persistence (83% [95% CI 73–92], p = 0.024) [66].

Thirteen quality registries in rheumatology participating in the European Spondyloarthritis Research Collaboration Network provided longitudinal, observational data to assess real-life 6- and 12-month effectiveness (i.e., retention, remission, low disease activity, and response rates) of secukinumab in 2017 patients with PsA. Secukinumab retention rates were 86% and 76% after 6 and 12 months, respectively, significantly higher in biologic-naïve patients than patients who previously received at least two b/tsDMARDs (90% and 82% vs 85% and 72%) [67].

A French retrospective study collected data from 842 patients with PsA of whom 15.8%, 24.2%, and 60.0% received secukinumab as a first-, second-, or third-line or greater bDMARD, respectively. The 1-year retention rate for secukinumab was 64% (95% CI 61–68) and was numerically greater with first- versus second- and third-line or greater therapy: 77% (95% CI 69–84) vs 65% (59–72) and 61% (57–66) [68].

Studies Comparing the Maintenance of Anti-IL-12/23 and Anti-TNFα Antibodies

The prospective, observational study PsABio followed patients with PsA who were prescribed first- to third-line treatment with ustekinumab or a TNF inhibitor. At 3 years, among 895 patients, the proportion still on their initial treatment was similar with ustekinumab and TNFi treatment (49.9% and 47.8%). Drug persistence was better for patients with first- or second-line bDMARD treatment than those with third-line treatment [69]. In the Italian part of the PsABio study (222 patients, 101 on ustekinumab and 121 on TNF inhibitor), at 1 year, 74.3% of the ustekinumab group continued treatment up to a mean of 12 ± 3 months versus 63.6% in the TNF inhibitor group. Ustekinumab had better persistence than a TNF inhibitor, overall and in specific subgroups (female patients, monotherapy without MTX, body mass index < 25 or > 30 kg/m2, patients receiving ustekinumab as second-line treatment instead of a second TNF inhibitor) [70].

Studies Comparing the Maintenance of Secukinumab and Anti-TNFα Agents

EXCEED, a double-blind, active-controlled, phase IIIb, multicenter study, evaluated the efficacy and safety of secukinumab (300 mg) versus adalimumab as first-line biological monotherapy for 52 weeks in patients with active PsA; 61/426 (14%) patients in the secukinumab group discontinued treatment by week 52 versus 101/427 (24%) in the adalimumab group, which suggested that the treatment retention rate was higher with secukinumab than adalimumab [71].

The biologic registers of the Nordic countries were used to identify all patients with PsA starting secukinumab or a TNF inhibitor in 2015–2018. All analyses were stratified by line of biologic treatment. The study included 6143 patients with 8307 treatment courses (secukinumab, n = 1227; adalimumab, n = 1367) and found no clinically significant difference in treatment retention or response rates between the two agents. The adjusted HRs for discontinuation with the first, second, and third line of treatment were 0.98 (95% CI 0.68–1.41), 0.94 (0.70–1.26), and 1.07 (0.84–1.36), respectively [72].

Studies Comparing the Maintenance of b/tsDMARDs

A nationwide cohort study involved the administrative healthcare database of the French health insurance system [73]. All adults with psoriasis (PsO) and PsA who were new users of biologics (not in the year before the index date) from January 1, 2015 to May 31, 2019 were included and followed up through December 31, 2019; 16,892 patients with PsO were included. Of these patients, 10,199 (60.4%) started a TNF inhibitor, 3982 (23.6%) an IL-12/23 inhibitor, and 2711 (16.0%) an IL-17 inhibitor. An additional 6531 patients with PsA were included: 4974 (76.2%) started a TNF inhibitor, 803 (12.3%) an IL-12/23 inhibitor, and 754 (11.5%) an IL-17 inhibitor. Overall 3-year persistence rates were 40.9% and 36.2% for PsO and PsA, respectively. After adjustment, the IL-17 inhibitor was associated with higher persistence as compared with the TNF inhibitor for PsO (weighted HR 0.78 [95% CI 0.73–0.83]) and PsA (weighted HR 0.70 [95% CI 0.58–0.85]) and as compared with the IL-12/23 inhibitor for PsA (weighted HR 0.69 [95% CI 0.55–0.87]). The overall persistence rate for PsA was relatively low, 73%, 49%, and 36% at 1, 2, and 3 years, respectively: 72%, 49%, and 35% for anti-TNFα antibodies; 72%, 48%, and 38% for anti-IL-12/23 antibodies; and 77%, 51%, and 42% for anti-IL-17 antibodies. The findings of this cohort study suggested that treatment persistence is better for an IL-17 inhibitor than TNF inhibitor as first-line targeted therapies for PsO and PsA [73].

A total of 2301 patients with PsA from a large healthcare provider database with at least two consecutive dispensed prescriptions of a biologic agent from January 1, 2002 to December 31, 2018 were followed to estimate persistence in a real-life setting. The most commonly prescribed drug was etanercept (33%), followed by adalimumab (29%), golimumab (12%), secukinumab (10%), ustekinumab (8%), and infliximab (8%). Approximately 40% of patients showed treatment persistence after 20 months of treatment, but only about 20% remained on any particular biologic agent after 5 years. Analyzing the data for all treatment periods while taking into account all lines of therapy revealed secukinumab with higher persistence than adalimumab, infliximab, and ustekinumab. On analyzing the data using only the first indicated biologic line, no single anti-TNFα agent was superior in persistence, but secukinumab was superior as second-line therapy to adalimumab, etanercept, infliximab, and ustekinumab [74].

A study compared treatment persistence among b/tsDMARD-naïve patients with PsA identified from the IBM MarketScan® Commercial and Medicare Supplemental databases (October 1, 2013–October 31, 2018) who initiated an IL-12/23 inhibitor versus a TNF inhibitor, tsDMARD, or IL-17 inhibitor. Persistence was longer for the IL-12/23 inhibitor cohort than TNF inhibitor cohort (269 vs 215 days, p < 0.001) or tsDMARD cohort (269 vs 213 days, p < 0.001) but comparable between the IL-12/23 inhibitor and IL-17 inhibitor cohorts (267 vs 246 days, p = 0.199). Fewer patients in the IL-12/23 inhibitor cohort discontinued their index medication than in the TNF inhibitor or tsDMARD cohorts, with no significant difference between the IL-12/23 inhibitor and IL-17 inhibitor cohorts [75].

Although the data are heterogeneous, the therapeutic maintenance of anti-IL-12/23 and anti-IL-17 antibodies, with very low immunogenicity, seems superior to that of anti-TNFα antibodies.

Proposed Pragmatic Approach

Thus, our six-point argument allows for proposing the following pragmatic approach to a patient with PsA in whom MTX has failed:

In the event of initiation of an anti-TNFα agent, maintaining treatment with MTX (whose tolerance and compliance problems are well known) seems preferable, even in the absence of evidence of the superior efficacy of the combination, to avoid immunization and reduced therapeutic maintenance.

In the event of initiation of anti-IL1-17, anti-IL-12/23, anti-IL-23 agents, or JAK inhibitors, again in the absence of evidence of the superior efficacy of the combination, discontinuing MTX therapy may be possible, at least in two steps, after verifying the efficacy of the targeted therapy initiated on the joints and skin; this would represent real added value for the patient who would no longer have to fear the iatrogenic risk of MTX treatment.

In case of associated moderate to severe psoriasis, the choice of the first-line targeted therapy allowing for stopping MTX treatment would be, in a patient with PsA in whom MTX failed, anti-IL-17 monotherapy (because of superiority versus TNF inhibitor on skin involvement) [2]; anti-IL-23 monotherapy may also be considered.

- Finally, if the rheumatological phenotype and/or the presence of extra-rheumatological manifestations is taken into account, proposals for a first targeted treatment could be the following:

- In case of associated axial involvement, treatment with an anti-IL-17 antibody and discontinuation of MTX or TNF inhibitor with MTX continuation [76].

- In case of associated active inflammatory bowel disease, either anti-TNFα mAbs and maintenance of MTX or anti-IL-12/23, anti-IL-23 antibodies, or JAK inhibitors and discontinuation of MTX.

These pragmatic proposals need to be confirmed in targeted studies and, above all, in daily practice.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Author Contributions

All authors (Philippe Goupille, Guillermo Carvajal Alegria, Frank Verhoeven, Daniel Wendling) contributed equally to the literature search and manuscript writing.

Funding

No funding was received for this publication, the journal’s Rapid Service Fee is covered from the author’s institution, University Hospital of Tours.

Data Availability

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study.

Declarations

Conflict of Interest

Philippe Goupille: Financial interests/Lasting or permanent links: none; Specific interventions: AbbVie, BMS, Galapagos, Janssen-Cilag, Lilly, MSD, Novartis, Pfizer, UCB; Indirect interests: Abbvie, Biogen, Pfizer, MSD, UCB, Janssen, Lilly, Novartis. Guillermo Carvajal Alegria: Financial interests/ Lasting or permanent links: none; Specific interventions: Abbvie, BMS, Galapagos, Lilly, MSD, Novartis, Chugai, Pfizer; Indirect interests: Novartis, Lilly, Abbvie, Biogen, Fresenius-Kabi. Frank Verhoeven: Financial interests/ Lasting or permanent links: none; Specific interventions: AbbVie, BMS, Galapagos, Janssen, Lilly, MSD, Novartis, Chugai, UCB; Indirect interests: Novartis. Daniel Wendling: Financial interests/ Lasting or permanent links: none; Ad hoc interventions: AbbVie, BMS, MSD, Pfizer, Roche Chugai, Amgen, Nordic Pharma, UCB, Novartis, Janssen, Celgene, Lilly, Galapagos; Indirect interests: Abbvie, Pfizer, Roche Chugai, MSD, UCB, Mylan, Fresenius Kabi.

Ethical Approval

This article is based on previously conducted studies and does not contain any new studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

References

- 1.Ritchlin CT, Colbert RA, Gladman DD. Psoriatic arthritis. N Engl J Med. 2017;376(21):2095–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wendling D, Hecquet S, Fogel O, et al. 2022 French Society for Rheumatology (SFR) recommendations on the everyday management of patients with spondyloarthritis, including psoriatic arthritis. Joint Bone Spine. 2022;89(3): 105344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Antoni CE, Kavanaugh A, Kirkham B, et al. Sustained benefits of infliximab therapy for dermatologic and articular manifestations of psoriatic arthritis: results from the infliximab multinational psoriatic arthritis controlled trial (IMPACT). Arthritis Rheum. 2005;52(4):1227–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mease PJ, Gladman DD, Ritchlin CT, et al. Adalimumab for the treatment of patients with moderately to severely active psoriatic arthritis: results of a double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Arthritis Rheum. 2005;52(10):3279–89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mease PJ, Kivitz AJ, Burch FX, et al. Etanercept treatment of psoriatic arthritis: safety, efficacy, and effect on disease progression. Arthritis Rheum. 2004;50(7):2264–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kavanaugh A, McInnes I, Mease P, et al. Golimumab, a new human tumor necrosis factor alpha antibody, administered every four weeks as a subcutaneous injection in psoriatic arthritis: twenty-four-week efficacy and safety results of a randomized, placebo-controlled study. Arthritis Rheum. 2009;60(4):976–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mease PJ, Fleischmann R, Deodhar AA, et al. Effect of certolizumab pegol on signs and symptoms in patients with psoriatic arthritis: 24-week results of a phase 3 double-blind randomised placebo-controlled study (RAPID-PsA). Ann Rheum Dis. 2014;73(1):48–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.McInnes IB, Mease PJ, Kirkham B, et al. Secukinumab, a human anti-interleukin-17A monoclonal antibody, in patients with psoriatic arthritis (FUTURE 2): a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2015;386(9999):1137–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mease PJ, van der Heijde D, Ritchlin CT, et al. Ixekizumab, an interleukin-17A specific monoclonal antibody, for the treatment of biologic-naive patients with active psoriatic arthritis: results from the 24-week randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled and active (adalimumab)-controlled period of the phase III trial SPIRIT-P1. Ann Rheum Dis. 2017;76(1):79–87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.McInnes IB, Asahina A, Coates LC, et al. Bimekizumab in patients with psoriatic arthritis, naive to biologic treatment: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial (BE OPTIMAL). Lancet. 2023;401(10370):25–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.McInnes IB, Kavanaugh A, Gottlieb AB, et al. Efficacy and safety of ustekinumab in patients with active psoriatic arthritis: 1 year results of the phase 3, multicentre, double-blind, placebo-controlled PSUMMIT 1 trial. Lancet. 2013;382(9894):780–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mease PJ, Rahman P, Gottlieb AB, et al. Guselkumab in biologic-naive patients with active psoriatic arthritis (DISCOVER-2): a double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2020;395(10230):1126–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kristensen LE, Keiserman M, Papp K, et al. Efficacy and safety of risankizumab for active psoriatic arthritis: 24-week results from the randomised, double-blind, phase 3 KEEPsAKE 1 trial. Ann Rheum Dis. 2022;81(2):225–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mease P, Hall S, FitzGerald O, et al. Tofacitinib or adalimumab versus placebo for psoriatic arthritis. N Engl J Med. 2017;377(16):1537–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.McInnes IB, Anderson JK, Magrey M, et al. Trial of upadacitinib and adalimumab for psoriatic arthritis. N Engl J Med. 2021;384(13):1227–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kavanaugh A, Mease PJ, Gomez-Reino JJ, et al. Treatment of psoriatic arthritis in a phase 3 randomised, placebo-controlled trial with apremilast, an oral phosphodiesterase 4 inhibitor. Ann Rheum Dis. 2014;73(6):1020–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Felten R, Lambert Cursay G, Lespessailles E. Is there still a place for methotrexate in severe psoriatic arthritis? Ther Adv Musculoskelet Dis. 2022;14:1759720X221092376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gossec L, Kerschbaumer A, Ferreira RJO, et al. EULAR recommendations for the management of psoriatic arthritis with pharmacological therapies: 2023 update. Ann Rheum Dis. 2024;83:706–19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Grijalva CG, Chung CP, Arbogast PG, Stein CM, Mitchel EF Jr, Griffin MR. Assessment of adherence to and persistence on disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARDs) in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2010;62:730–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.de Thurah A, Nørgaard M, Johansen MB, Stengaard-Pedersen K. Methotrexate compliance among patients with rheumatoid arthritis: the influence of disease activity, disease duration, and co-morbidity in a 10-year longitudinal study. Scand J Rheumatol. 2010;39:197–205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cannon GW, Mikuls TR, Hayden CL, et al. Merging Veterans Affairs rheumatoid arthritis registry and pharmacy data to assess methotrexate adherence and disease activity in clinical practice. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2011;63:1680–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.de Thurah A, Nørgaard M, Harder I, Stengaard-Pedersen K. Compliance with methotrexate treatment in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: influence of patients’ beliefs about the medicine. A prospective cohort study. Rheumatol Int. 2010;30:1441–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Heiberg MS, Koldingsnes W, Mikkelsen K, et al. The comparative one-year performance of anti-tumor necrosis factor alpha drugs in patients with rheumatoid arthritis, psoriatic arthritis, and ankylosing spondylitis: results from a longitudinal, observational, multicenter study. Arthritis Rheum. 2008;59:234–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Soliman MM, Ashcroft DM, Watson KD, et al. Impact of concomitant use of DMARDs on the persistence with anti-TNF therapies in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: results from the British Society for Rheumatology Biologics Register. Ann Rheum Dis. 2011;70:583–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Listing J, Strangfeld A, Rau R, et al. Clinical and functional remission: even though biologics are superior to conventional DMARDs overall success rates remain low–results from RABBIT, the German biologics register. Arthritis Res Ther. 2006;8:R66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Askling J, Fored CM, Brandt L, et al. Time-dependent increase in risk of hospitalisation with infection among Swedish RA patients treated with TNF antagonists. Ann Rheum Dis. 2007;66:1339–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mariette X, Gottenberg JE, Ravaud P, Combe B. Registries in rheumatoid arthritis and autoimmune diseases: data from the French registries. Rheumatology. 2011;50:222–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yazici Y, Shi N, John A. Utilization of biologic agents in rheumatoid arthritis in the United States: analysis of prescribing patterns in 16,752 newly diagnosed patients and patients new to biologic therapy. Bull NYU Hosp Jt Dis. 2008;66:77–85. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Emery P. Why is there persistent disease despite biologic therapy? Importance of early intervention. Arthritis Res Ther. 2014;16:115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Emery P, Sebba A, Huizinga TW. Biologic and oral disease-modifying antirheumatic drug monotherapy in rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2013;72(12):1897–904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nikiphorou E, Negoescu A, Fitzpatrick JD, et al. Indispensable or intolerable? Methotrexate in patients with rheumatoid and psoriatic arthritis: a retrospective review of discontinuation rates from a large UK cohort. Clinical Rheumatol. 2014;33:609–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Salliot C, van der Heidje D. Long-term safety of methotrexate monotherapy in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: a systematic literature research. Ann Rheum Dis. 2009;68:1100–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Behrens F, Cañete JD, Olivieri I, van Kuijk AW, McHugh N, Combe B. Tumour necrosis factor inhibitor monotherapy vs combination with MTX in the treatment of PsA: a systematic review of the literature. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2015;54(5):915–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Antoni C, Krueger GG, de Vlam K, et al. Infliximab improves signs and symptoms of psoriatic arthritis: results of the IMPACT 2 trial. Ann Rheum Dis. 2005;64:1150–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sharif K, Gendelman O, Langevitz P, et al. Efficacy and survival of golimumab with and without methotrexate in patients with psoriatic arthritis: a retrospective study from daily clinical practice. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. 2018;32(5):692–700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Walsh JA, Gottlieb AB, Hoepken B, Nurminen T, Mease PJ. Efficacy of certolizumab pegol with and without concomitant use of disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drugs over 4 years in psoriatic arthritis patients: results from the RAPID-PsA randomized controlled trial. Clin Rheumatol. 2018;37(12):3285–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Smolen JS, Sebba A, Ruderman EM, et al. Efficacy and safety of ixekizumab with or without methotrexate in biologic-naïve patients with psoriatic arthritis: 52-week results from SPIRIT-H2H Study. Rheumatol Ther. 2020;7(4):1021–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.McInnes IB, Mease PJ, Tanaka Y, et al. Bimekizumab efficacy and safety in biologic DMARD-naïve patients with psoriatic arthritis was consistent with or without methotrexate: 52-week results from the phase 3 active-reference study BE-OPTIMAL EULAR 2023. Ann Rheum Dis. 2023;82(Suppl1):1133. POS1537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Koehm M, Foldenauer AC, Rossmanith T, et al. Differences in treatment response between female and male psoriatic arthritis patients during IL-12/23 therapy with or without methotrexate: post hoc analysis of results from the randomised MUST trial. RMD Open. 2023;9(4):e003538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ritchlin CT, Mease PJ, Boehncke WH, et al. Sustained and improved guselkumab response in patients with active psoriatic arthritis regardless of baseline demographic and disease characteristics: pooled results through week 52 of two phase III, randomised, placebo-controlled studies. RMD Open. 2022;8(1):e002195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kivitz AJ, FitzGerald O, Nash P, et al. Efficacy and safety of tofacitinib by background methotrexate dose in psoriatic arthritis: post hoc exploratory analysis from two phase III trials. Clin Rheumatol. 2022;41(2):499–511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Nash P, Richette P, Gossec L, et al. Upadacitinib as monotherapy and in combination with non-biologic disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs for psoriatic arthritis. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2022;61(8):3257–68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Vogelzang EH, Kneepkens EL, Nurmohamed MT, et al. Anti-adalimumab antibodies and adalimumab concentrations in psoriatic arthritis; an association with disease activity at 28 and 52 weeks of follow-up. Ann Rheum Dis. 2014;73:2178–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zisapel M, Zisman D, Madar-Balakirski N, et al. Prevalence of TNF-α blocker immunogenicity in psoriatic arthritis. J Rheumatol. 2015;42:73–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.van Kuijk AW, de Groot M, Stapel SO, et al. Relationship between the clinical response to adalimumab treatment and serum levels of adalimumab and anti-adalimumab antibodies in patients with psoriatic arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2010;69:6245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kavanaugh A, McInnes IB, Mease PJ, et al. Clinical efficacy, radiographic and safety findings through 2 years of golimumab treatment in patients with active psoriatic arthritis: results from a long-term extension of the randomised, placebo-controlled GO-REVEAL study. Ann Rheum Dis. 2013;72:1777–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kavanaugh A, Krueger GG, Beutler A, et al. Infliximab maintains a high degree of clinical response in patients with active psoriatic arthritis through 1 year of treatment: results from the IMPACT 2 trial. Ann Rheum Dis. 2007;66:498–505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Reich K, Blauvelt A, Armstrong A, et al. Secukinumab, a fully human anti-interleukin-17A monoclonal antibody, exhibits minimal immunogenicity in patients with moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis. Br J Dermatol. 2017;176(3):752–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Reich K, Blauvelt A, Armstrong A, et al. Secukinumab, a fully human anti-interleukin-17A monoclonal antibody, exhibits low immunogenicity in psoriasis patients treated up to 5 years. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2019;33(9):1733–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Strand V, Balsa A, Al-Saleh J, et al. Immunogenicity of biologics in chronic inflammatory diseases: a systematic review. BioDrugs. 2017;31(4):299–316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Deodhar A, Gladman DD, McInnes IB, et al. Secukinumab immunogenicity over 52 weeks in patients with psoriatic arthritis and ankylosing spondylitis. J Rheumatol. 2020;47(4):539–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Reich K, Jackson K, Ball S, et al. Ixekizumab pharmacokinetics, anti-drug antibodies, and efficacy through 60 weeks of treatment of moderate to severe plaque psoriasis. J Invest Dermatol. 2018;138(10):2168–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ritchlin CT, Merola JF, Gellett AM, Lin CY, Muram T. Anti-drug antibodies, efficacy, and impact of concomitant methotrexate in ixekizumab-treated patients with psoriatic arthritis. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2018;70(suppl 9).

- 54.Oliver R, Krueger JG, Glatt S, et al. Bimekizumab for the treatment of moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis: efficacy, safety, pharmacokinetics, pharmacodynamics and transcriptomics from a phase IIa, randomized, double-blind multicentre study. Br J Dermatol. 2022;186(4):652–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.SmPC bimekizumab. https://ema.europa.eu/medicines/human/EPAR/bimzelx

- 56.Mojtahed Poor S, Henke M, Ulshöfer T, et al. The role of antidrug antibodies in ustekinumab therapy and the impact of methotrexate. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2023;62(12):3993–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Armstrong A, Eyerich K, Conrad C, et al. Immunogenicity and pharmacokinetics of guselkumab among patients with moderate-to-severe psoriasis in VOYAGE-1 and VOYAGE-2. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2023;37(12):e1375–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Rahman P, Ritchlin CT, Helliwell PS, et al. Pooled safety results through 1 year of 2 phase III trials of guselkumab in patients with psoriatic arthritis. J Rheumatol. 2021;48(12):1815–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.SmPC risankizumab. https://ema.europa.eu/medicines/human/EPAR/skyrizi

- 60.Fagerli KM, Lie E, van der Heijde D, et al. The role of methotrexate co-medication in TNF-inhibitor treatment in patients with psoriatic arthritis: results from 440 patients included in the NOR-DMARD study. Ann Rheum Dis. 2014;73:132–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Kristensen LE, Gülfe A, Saxne T, Geborek P. Efficacy and tolerability of anti-tumour necrosis factor therapy in psoriatic arthritis patients: results from the South Swedish Arthritis Treatment Group register. Ann Rheum Dis. 2008;67:364–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Glintborg B, Østergaard M, Dreyer L, et al. Treatment response, drug survival, and predictors thereof in 764 patients with psoriatic arthritis treated with anti-tumor necrosis factor α therapy: results from the nationwide Danish DANBIO registry. Arthritis Rheum. 2011;63(2):382–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Hoa S, Choquette D, Bessette L, et al. Comparing adalimumab and etanercept as first line agents in patients with psoriatic arthritis: data from the Rhumadata clinical database and registry [abstract]. Arthritis Rheum. 2013;65(Suppl 10):S145. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Lindström U, Di Giuseppe D, Delcoigne B, et al. Effectiveness and treatment retention of TNF inhibitors when used as monotherapy versus comedication with csDMARDs in 15 332 patients with psoriatic arthritis. Data from the EuroSpA collaboration. Ann Rheum Dis. 2021;80(11):1410–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Spadaro A, Ceccarelli F, Scrivo R, Valesini G. Life-table analysis of etanercept with or without methotrexate in patients with psoriatic arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2008;67:1650–1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Alegre-Sancho JJ, Núñez-Monje V, Campos-Fernández C, et al. Real-world effectiveness and persistence of secukinumab in the treatment of patients with psoriatic arthritis. Front Med (Lausanne). 2023;10:1294247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Michelsen B, Georgiadis S, Di Giuseppe D, et al. Real-world six- and twelve-month drug retention, remission, and response rates of secukinumab in 2,017 patients with psoriatic arthritis in thirteen european countries. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2022;74(7):1205–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Ruyssen-Witrand A, Lardy-Cléaud A, Desfleurs E, et al. Factors associated with the retention of secukinumab (SEC) in patients with psoriatic arthritis (PSA) in real world practice: results from the retrospective FORSYA study. Ann Rheum Dis. 2023;82(Suppl 1):1127 (POS1530). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Gossec L, Siebert S, Bergmans P, et al. Long-term effectiveness and persistence of ustekinumab and TNF inhibitors in patients with psoriatic arthritis: final 3-year results from the PsABio real-world study. Ann Rheum Dis. 2023;82(4):496–506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Gremese E, Ciccia F, Selmi C, et al. Persistence, effectiveness and safety of ustekinumab compared to TNF inhibitors in psoriatic arthritis within the Italian PsABio cohort. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2023;41(3):735–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.McInnes IB, Behrens F, Mease PJ, et al. Secukinumab versus adalimumab for treatment of active psoriatic arthritis (EXCEED): a double-blind, parallel-group, randomised, active-controlled, phase 3b trial. Lancet. 2020;395(10235):1496–505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Lindström U, Glintborg B, Di Giuseppe D, et al. Comparison of treatment retention and response to secukinumab versus tumour necrosis factor inhibitors in psoriatic arthritis. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2021;60(8):3635–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Pina Vegas L, Penso L, Claudepierre P, Sbidian E. Long-term persistence of first-line biologics for patients with psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis in the French Health Insurance Database. JAMA Dermatol. 2022;158(5):513–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Haddad A, Gazitt T, Feldhamer I, et al. Treatment persistence of biologics among patients with psoriatic arthritis. Arthritis Res Ther. 2021;23(1):44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Walsh JA, Cai Q, Lin I, Pericone CD, Chakravarty SD. Treatment persistence and adherence among patients with psoriatic arthritis who initiated targeted immune modulators in the US: a retrospective cohort study. Adv Ther. 2021;38(5):2353–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Wendling D, Verhoeven F, Claudepierre P, Goupille P, Pham T, Prati C. Axial psoriatic arthritis: new entity or clinical form only? Joint Bone Spine. 2022;89(5):105409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study.