Abstract

Introduction

The relative efficacy of bimekizumab and risankizumab in patients with PsA who were biologic disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drug naïve (bDMARD naïve) or with previous inadequate response or intolerance to tumor necrosis factor inhibitors (TNFi-IR) was assessed at 52 weeks (Wk52) using matching-adjusted indirect comparisons (MAIC).

Methods

Relevant trials were systematically identified. For patients who were bDMARD naïve, individual patient data (IPD) from BE OPTIMAL (NCT03895203; N = 431) were matched with summary data from KEEPsAKE-1 (NCT03675308; N = 483). For patients who were TNFi-IR, IPD from BE COMPLETE (NCT03896581; N = 267) were matched with summary data from the TNFi-IR patient subgroup in KEEPsAKE-2 (NCT03671148; N = 106). To adjust for cross-trial differences, patients from the bimekizumab trials were re-weighted to match the baseline characteristics of patients in the risankizumab trials. Adjustment variables were selected based on expert consensus (n = 5) and adherence to established MAIC guidelines. Recalculated bimekizumab Wk52 outcomes for American College of Rheumatology (ACR) 20/50/70 response criteria and minimal disease activity (MDA) index (non-responder imputation) were compared with risankizumab outcomes via non-placebo-adjusted comparisons.

Results

In patients who were bDMARD naïve, bimekizumab had a significantly greater likelihood of response than risankizumab at Wk52 for ACR50 (odds ratio [95% confidence interval]: 1.52 [1.11, 2.09]) and ACR70 (1.80 [1.29, 2.51]). In patients who were TNFi-IR, bimekizumab had a significantly greater likelihood of response than risankizumab at Wk52 for ACR20 (1.78 [1.08, 2.96]), ACR50 (3.05 [1.74, 5.32]), ACR70 (3.69 [1.82, 7.46]), and MDA (2.43 [1.37, 4.32]).

Conclusions

Using MAIC, bimekizumab demonstrated a greater likelihood of efficacy in most ACR and MDA outcomes than risankizumab in patients with PsA who were bDMARD naïve and TNFi-IR at Wk52.

Trial Registration

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s40744-024-00706-w.

Keywords: ACR, Bimekizumab, Biologics, IL-17, IL-23, MAIC, MDA, Psoriatic arthritis, Risankizumab

Key Summary Points

| Why carry out this study? |

| There is currently no direct head-to-head evidence of the long-term efficacy of bimekizumab compared to interleukin (IL)-23 inhibitors in psoriatic arthritis (PsA). |

| This study uses a matching-adjusted indirect comparison (MAIC) approach to compare the efficacy of bimekizumab 160 mg every 4 weeks (Q4W) and risankizumab 150 mg every 12 weeks (Q12W) at 52 weeks for the treatment of PsA in patients who were naive to biologic disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (bDMARD naïve) or patients with previous inadequate response or intolerance to tumor necrosis factor inhibitors (TNFi-IR). |

| What was learned from this study? |

| In patients who were bDMARD naïve, bimekizumab had a greater likelihood of achieving at least a 50 or 70% improvement according to American College of Rheumatology response criteria (ACR50/70) compared to risankizumab at 52 weeks. |

| In patients who were TNFi-IR, bimekizumab had a greater likelihood of achieving ACR20/50/70 and MDA outcomes compared to risankizumab at 52 weeks. |

| Using MAIC methodology, bimekizumab was favorable to risankizumab in achieving more stringent, long-term treatment outcomes in patients with PsA who were bDMARD naïve and TNFi-IR. |

Introduction

Psoriatic arthritis (PsA) is a heterogeneous and systemic inflammatory disorder, characterized by musculoskeletal inflammation at entheseal sites, digits, and axial skeleton (arthritis, enthesitis, dactylitis, and spondylitis), which generally occurs in up to 30% of patients with psoriasis [1]. Advances in the treatment of PsA have identified several cytokine-driven inflammatory pathways (such as interleukin [IL]-12, IL-17, and IL-23]) that can be successfully targeted with specific inhibitors [2]. Several treatment guidelines recommend the use of biologic and/or targeted synthetic disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drugs (b/tsDMARDs) as first-line treatment for PsA [3, 4]; however, which of these available treatments can provide the best outcomes for patients with PsA is currently unclear.

Bimekizumab is a humanized monoclonal immunoglobulin G1 antibody that selectively inhibits IL-17A and IL-17F and has recently been approved in Europe, the UK, and Japan for PsA. Its efficacy and safety were recently established in two phase 3 randomized controlled trials (RCTs): BE OPTIMAL (NCT03895203) [5] in patients who were naive to biologic disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drugs (bDMARD naïve) and BE COMPLETE (NCT03896581) [6] in patients with previous inadequate response or intolerance to tumor necrosis factor inhibitors (TNFi-IR). An open-label extension (OLE) of both trials, BE VITAL (NCT04009499) [7], is also currently ongoing to assess long-term efficacy. Risankizumab, a selective IL-23 inhibitor, has also demonstrated efficacy and safety in the KEEPsAKE-1 (NCT03675308) [8] and KEEPsAKE-2 (NCT03671148) [9] RCTs for the treatment of active PsA. There is particular interest in evaluating the relative efficacy of IL-17A/F compared with IL-23 inhibition, given their broader cytokine inhibitory potential compared to IL-17A monospecific inhibitors [10].

When head-to-head comparisons in RCTs are unavailable, the relative effectiveness of several treatments may be evaluated by conducting a network meta-analysis (NMA) of placebo-controlled trials. Although the comparative efficacy of bimekizumab with other b/tsDMARDs over a shorter treatment period of ≤ 24 weeks has been established in a recently published NMA [11] and model-based meta-analysis (MBMA) [12], there are no analyses for longer-term comparative efficacy due to the lack of a placebo common comparator after 24 weeks [13]. In the absence of a common comparator, matching-adjusted indirect comparisons (MAICs) can overcome limitations in assessing comparative efficacy by using an approach similar to propensity score weighting to balance the baseline characteristics of different trial populations [14, 15]. Previous MAIC analyses comparing bimekizumab with other treatments for PsA, such as guselkumab and secukinumab, have demonstrated that bimekizumab was more favorable in achieving positive treatment outcomes in patients with PsA who were both bDMARD naïve and TNFi-IR [16, 17].

In this study, MAIC was conducted to assess the relative efficacy of bimekizumab vs risankizumab at 52 weeks in patients with PsA who were bDMARD-naive and TNFi-IR. Following the findings of a recently completed NMA and MBMA [11, 12], this MAIC aims to provide additional evidence of the long-term comparative efficacy (beyond Week 24) between bimekizumab and risankizumab.

Methods

Systematic Literature Review and Source Data

A systematic literature review (SLR) was conducted according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews (PRISMA) guidelines [18] to identify relevant clinical evidence for existing bDMARD therapies in PsA published from January 1991 to December 2022 and was used as the basis for this MAIC analysis. Details on SLR eligibility criteria and reasons for inclusion/exclusion were previously published [11]. All available IL-23 inhibitors in PsA were selected from this SLR as potential comparators. As MAICs were previously conducted to compare bimekizumab and guselkumab [16], risankizumab was chosen as the comparator for this analysis due to its established availability and wide usage in the PsA treatment market in Europe, the UK and Japan [19]. The KEEPsAKE-1 (for patients who were bDMARD naïve) and KEEPsAKE-2 (for a subgroup of patients who were TNFi-IR) RCTs were identified as most relevant for this MAIC analysis because of their alignment with the target patient populations in the BE OPTIMAL and BE COMPLETE trials. In this analysis, the efficacy of bimekizumab dosed at 160 mg every 4 weeks (Q4W) was compared to risankizumab dosed at 150 mg every 12 weeks (Q12W) in patients with PsA who were bDMARD naïve and TNFi-IR. Baseline characteristics for the TNFi-IR subgroup of patients in KEEPsAKE-2 were obtained from a previous presentation at the 2023 American Academy of Dermatology Annual Meeting, New Orleans, Louisiana (17–21 March 2023), as data stratified by prior TNF use were not reported in the original publication [20]. Patients in the TNFi-IR subgroup received at least one prior TNFi in the bimekizumab and risankizumab RCTs. This analysis was based on previously conducted studies and does not contain any new studies with human participants or animals performed by any authors. All the results presented in this article are in aggregate form, and no personally identifiable information was used for this study.

Selection of Baseline Characteristics for Matching

Adjustment variables were selected based on a review of previous MAICs in PsA [21, 22], consensus agreement with clinical experts (n = 5), and adherence to established MAIC guidelines [15]. Exploratory univariate sensitivity analyses evaluated the impact of all adjustment variables. To adjust for cross-trial differences, patients treated with bimekizumab in the BE OPTIMAL, BE COMPLETE, and BE VITAL RCTs were re-weighted to match the baseline characteristics of the patients treated with risankizumab in the KEEPsAKE-1 and KEEPsAKE-2 trials. Weights were determined based on age, sex, methotrexate (MTX) use, Health Assessment Questionnaire Disability Index (HAQ-DI) score, percentage with psoriasis affecting ≥ 3% body surface area (BSA ≥ 3%), swollen joint count – 68 joints (SJC 68), tender joint count—66 joints (TJC 66), and disease duration. Adjustments for race and weight at baseline were excluded as they were well balanced across trials and their adjustment impact was minimal. Adjustments for dactylitis and enthesitis at baseline were excluded as the impact of the effective sample size (ESS) was assessed to be too large, leading to an extreme distribution of weights.

Adjustment of Individual Patient Data to Aggregate Data and Pairwise Comparisons

The MAIC methodology described by Signorovitch et al. [23] was followed, and analyses were conducted in accordance with the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence Decision Support Unit Technical Support Document 18 (NICE DSU TSD 18) to create a robust population-adjusted indirect treatment comparison (ITC) [15]. Inverse propensity score weighting was used to form weighted mean estimators of the expected mean outcomes for bimekizumab in risankizumab trial populations, where the propensity scores are found using a method of moments [23]. All analyses were conducted with R version 3.6.2. The R program from the NICE DSU TSD 18 was used to implement this MAIC.

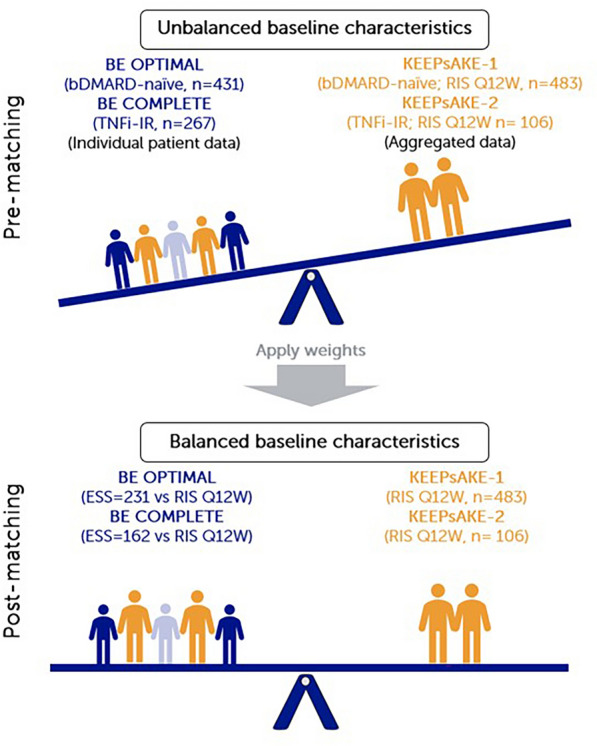

For patients who were bDMARD naïve, individual patient data (IPD) from the bimekizumab arm of BE OPTIMAL were matched to summary data from KEEPsAKE-1. For patients who were TNFi-IR, IPD from the bimekizumab arm of BE COMPLETE and the BE VITAL OLE were matched to summary data of a subgroup of patients who were TNFi-IR from KEEPsAKE-2 (Fig. 1). As only summary data were available for KEEPsAKE-1 and KEEPsAKE-2, it was not possible to control for unobserved or unreported variables from the RCTs.

Fig. 1.

Summary of MAIC matching. MAICs use IPD from trials of one treatment to match baseline aggregate statistics reported from trials of another treatment. Using propensity score weighting techniques to balance trial population characteristics, indirect comparisons can be made. Trial populations adjusted for age, sex, disease duration, MTX use, HAQ-DI, BSA ≥ 3%, SJC and TJC. bDMARD biologic disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drug, BSA body surface area, ESS effective sample size, HAQ-DI Health Assessment Questionnaire–Disability Index, IPD individual patient data, MAIC matching-adjusted indirect comparison, MTX methotrexate, Q12W every 12 weeks, RIS risankizumab, SJC swollen joint count, TJC tender joint count, TNFi-IR tumor necrosis factor inhibitor-inadequate response or intolerant

Outcomes

The outcomes reported were the proportion of patients with 20/50/70% improvement in the American College of Rheumatology response criteria (ACR20/50/70) and minimal disease activity (MDA, minimum 5 out of 7 domains achieved) scores. These were selected in line with the Outcomes Measures in Rheumatology (OMERACT) [24] and the Group for Research and Assessment of Psoriasis and Psoriatic Arthritis (GRAPPA) [4] guidelines. For this MAIC analysis, 52-week data from both bimekizumab and risankizumab trials were compared. Analyses of Psoriasis Area and Severity Index (PASI) scores and inhibition of radiographic progression outcomes were not feasible as baseline characteristics for the subset of patients who received treatment up to 52 weeks in KEEPsAKE-2 were not reported.

Reporting of Missing Data

Published outcomes were taken from the intent-to-treat population in KEEPsAKE-1 and KEEPsAKE-2, while IPD were taken from the intent-to-treat population in BE OPTIMAL, BE COMPLETE, and BE VITAL. Missing binary outcome data (ACR20/50/70 and MDA) were handled using non-responder imputation (NRI) methods.

Non-Placebo-Adjusted Outcome Comparisons

All patients randomized to placebo in the bimekizumab and risankizumab RCTs received active treatment from Week 16 onwards, resulting in the absence of placebo as a common comparator in all RCTs after Week 16. Therefore, non-placebo-adjusted (unanchored) outcomes at Week 52 from KEEPsAKE-1 and KEEPsAKE-2 were directly compared with recalculated outcomes from the bimekizumab arms in BE OPTIMAL and BE COMPLETE/BE VITAL. This MAIC analysis included all patients who were originally randomized to active treatment in BE COMPLETE (including those that subsequently entered BE VITAL) and excluded those who were originally randomized to placebo treatment.

Reporting of Results

After matching, the ESS indicates the number of independent, non-weighted individuals required to give an estimate with the same precision as the weighted sample estimate and is expressed as a proportion of the original sample size (OSS) from the source trials. Recalculated outcomes were reported as adjusted response rates, and the relative effects of bimekizumab vs risankizumab in different patient groups were reported as odds ratios (ORs) with 95% confidence intervals (95% CI, based on ESS). A standard value of p ≤ 0.05 was considered the threshold for concluding statistical significance (i.e., greater/lesser likelihood or comparable at achieving an outcome response compared to risankizumab).

Results

Patient baseline values for adjusted characteristics before matching are provided in Table 1 for both bDMARD-naïve and TNFi-IR patient subgroups in the bimekizumab and risankizumab RCTs. Before matching, patients in the BE OPTIMAL trial had shorter disease duration and lower HAQ-DI and SJC/TJC scores, and there was a lower proportion of patients with psoriasis covering BSA ≥ 3% compared to the corresponding subgroups in KEEPsAKE-1. Patients in the BE COMPLETE/BE VITAL trial had shorter disease duration, lower HAQ-DI and SJC/TJC scores. There was a higher proportion of patients with psoriasis covering BSA ≥ 3%, and a similar proportion of patients who were receiving MTX therapy, compared to the corresponding subgroups in KEEPsAKE-2.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of patients from bimekizumab (BE OPTIMAL/BE COMPLETE/BE VITAL) and risankizumab (KEEPsAKE-1/2) trials before matching

| Mean (SD) unless stated | bDMARD naïve | TNFi-IR | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| BE OPTIMAL | KEEPsAKE-1 | BE COMPLETE/BE VITAL | KEEPsAKE-2 | |

| N = 431 | N = 483 | N = 267 | N = 106 | |

| Age, years | 48.5 (12.6) | 52—median value | 50.1 (12.4) | 54.2 (12.7) |

| Male, % | 47 | 52 | 49 | 44 |

| Time since diagnosis, years | 6.0 (7.3) | 7.1 (7.0) | 9.6 (9.9) | 10.5 (9.2) |

| MTX use, % | 59 | 65 | 45 | 45 |

| SJC (of 66 joints) | 9.0 (6.2) | 12.1 (7.8) | 9.7 (7.5) | 13.4 (8.9) |

| TJC (of 68 joints) | 16.8 (11.8) | 20.8 (14.1) | 18.4 (13.5) | 22.8 (14.9) |

| HAQ-DI score | 0.82 (0.59) | 1.15 (0.66) | 0.97 (0.59) | 1.20 (0.60) |

| BSA ≥ 3%, % | 50 | 57 | 66 | 55 |

bDMARD biologic disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drug, BSA body surface area, HAQ-DI Health Assessment Questionnaire–Disability Index, MTX methotrexate, SD standard deviation, SJC swollen joint count, TJC tender joint count, TNFi-IR tumor necrosis factor inhibitor-inadequate response or intolerant

bDMARD-Naïve Patient Subgroup

Patients with PsA who were bDMARD naïve from BE OPTIMAL (bimekizumab, n = 431) were matched to those from KEEPsAKE-1 (risankizumab Q12W, n = 483). The post-matching ESS for bimekizumab was 231.00 (53.6% of OSS) compared to risankizumab (Fig. 2a and Supplementary Table S1).

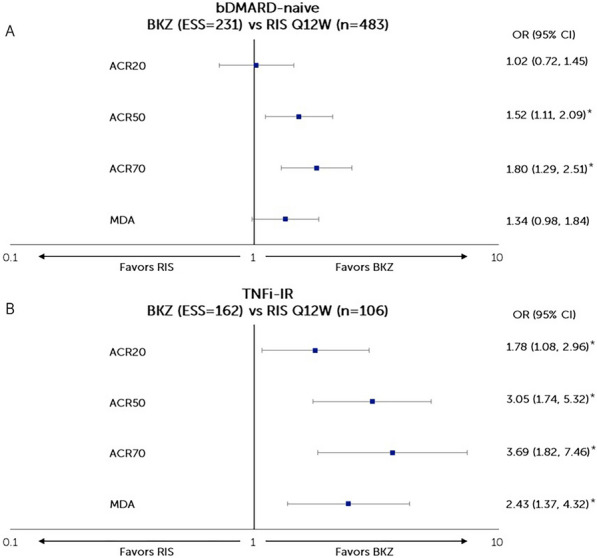

Fig. 2.

Matching-adjusted odds ratio comparison of bimekizumab vs risankizumab at Week 52 (NRI). A BKZ 160 mg Q4W vs RIS 150 mg Q12W in patients with PsA who were bDMARD naïve, B BKZ 160 mg Q4W vs RIS 150 mg Q12W in patients with PsA who were TNFi-IR. *Statistical significance. Figure shows a logarithmic scale. ACR American College of Rheumatology, ACR20/50/70 at least a 20/50/70% improvement according to the ACR response criteria, bDMARD biologic disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drugs, BKZ bimekizumab, CI confidence interval, ESS effective sample size, MDA minimal disease activity, NRI non-responder imputation, OR odds ratio, PsA psoriatic arthritis, Q4W every 4 weeks, Q12W every 12 weeks, RIS risankizumab, TNFi-IR tumor necrosis factor inhibitor-inadequate response or intolerant

Compared to risankizumab, bimekizumab had a greater likelihood of achieving ACR50 (OR [95% CI]: 1.52 [1.11, 2.09], p = 0.009] and ACR70 (1.80 [1.29, 2.51], p < 0.001) responses and was comparable in achieving ACR20 (1.02 [0.72, 1.45], p = 0.916) and MDA (1.34 [0.98, 1.84], p = 0.068) responses at Week 52 (Fig. 2a).

TNFi-IR Patients

Patients with PsA who were TNFi-IR from BE COMPLETE/BE VITAL (bimekizumab, n = 267) were matched to those from KEEPsAKE-2 (risankizumab Q12W, n = 106). The post-matching ESS for bimekizumab was 161.91 (60.6% of OSS) (Fig. 2b and Supplementary Table S2).

Compared to risankizumab, bimekizumab had a greater likelihood of achieving ACR20 (1.78 [1.08, 2.96], p = 0.025), ACR50 (3.05 [1.74, 5.32], p < 0.001), ACR70 (3.69 [1.82, 7.46], p < 0.001), and MDA (2.43 [1.37, 4.32], p = 0.003) responses at Week 52 (Fig. 2b).

Unadjusted response rates and ORs for both treatments are available in Supplementary Tables S1 and S2. The adjusted ORs were similar to unadjusted ORs for all outcomes, providing further support for the validity of these findings.

Discussion

In this MAIC analysis, patients receiving bimekizumab who were bDMARD naïve had a greater likelihood of achieving ACR50 and ACR70 responses than those treated with risankizumab. Bimekizumab was statistically comparable but numerically better than risankizumab for ACR20 and MDA outcomes. In patients who were TNFi-IR, bimekizumab demonstrated a greater likelihood of achieving all ACR and MDA responses than those receiving risankizumab.

These findings are consistent with a recent NMA and MBMA suggesting higher efficacy of bimekizumab versus risankizumab in joint outcomes at 16–24 weeks [11, 12]. While IL-17 and IL-23 pathways are distinct in PsA pathogenesis, it has been shown that IL-23 modulates IL-17A production upstream in the psoriatic inflammatory cascade. Therefore, treatments such as bimekizumab which directly target the IL-17 pathway further down this cascade may have more potential for disease specificity and rapid onset of action than those targeting IL-23 [25]. The results of this study suggest that most patients achieve higher treatment targets in PsA with dual inhibition of IL-17A/F compared to IL-23 mono-inhibition.

Study Limitations

This MAIC analysis has limitations, both intrinsic to the methodology and specific to this analysis. This MAIC analysis required the use of TNFi-IR patient level data from BE VITAL OLE because of the lack of data beyond week 16 in BE COMPLETE. The efficacy analyses used for BE VITAL OLE were conducted on the total patient population that started BE COMPLETE using NRI methodology, thereby reducing uncertainties introduced from using OLE data. All patients completing Week 16 in BE COMPLETE were eligible to enroll in BE VITAL, and patients receiving placebo were switched to bimekizumab. Although observed patient variables at baseline could be matched, it was not possible to control unobserved or unreported variables. Only summary level data from the risankizumab trials KEEPsAKE-1 and KEEPsAKE-2 were used in these analyses. There were also differences in the duration of the placebo-controlled segment between RCTs (16 weeks for BE OPTIMAL/BE COMPLETE and 24 weeks for KEEPsAKE-1/KEEPsAKE-2). There was variation in the study designs (active treatment blind [BE OPTIMAL] vs open-label [BE COMPLETE/BE VITAL/KEEPsAKE-1/KEEPsAKE-2]) at Week 52, although none of the studies were placebo controlled at Week 52; hence, all patients included in this MAIC were aware that they were receiving active treatment. Analyses for dactylitis and enthesitis at baseline were not feasible as the impact of the effective sample size (ESS) was assessed to be too large, leading to an extreme distribution of weights. This is a limitation of this analysis. Recent evidence demonstrated clinical examination has low specificity for assessing enthesitis compared with diagnostic assessment via ultrasonography [26, 27]. Analyses of PASI scores and inhibition of radiographic progression were not feasible as baseline characteristics for the subset of patients who received treatment up to 52 weeks were not reported. Analyses by prior TNFi use were not feasible as efficacy outcomes stratified by prior TNFi use were not reported from the RCTs; however, patients in the TNFi-IR subgroups were known to have received at least one prior TNFi. Safety outcomes could not be analyzed as the KEEPsAKE-2 RCT did not provide safety data for the TNFi-IR patient subgroup of interest.

Conclusion

Using established MAIC methodology, bimekizumab demonstrated a higher likelihood of achieving clinical efficacy outcomes than risankizumab at Week 52 in patients who were bDMARD naïve (for ACR50 and ACR70 outcomes) and TNFi-IR (for all ACR and MDA outcomes) with PsA. The results of this analysis should be viewed in the context of the limitations for an indirect comparison. Yet, the use of IPD and established MAIC methodology provides credible comparative evidence in the absence of a confirmatory head-to-head RCT.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the clinical investigators who provided advice on the design and implementation of this study.

Medical Writing/Editorial Assistance

The authors also acknowledge Heather Edens, PhD, UCB Pharma, Smyrna, GA, USA, and Costello Medical, UK, for publication coordination and editorial assistance and Darryl Low, PhD, Cytel Inc, UK, for medical writing and editorial assistance based on the authors’ input and direction. UCB Pharma funded support for third-party writing assistance for the article.

Author Contributions

Substantial contributions to study conception and design: Damon Willems, Vanessa Taieb, Jason Eells; substantial contributions to analysis and interpretation of the data: Damon Willems, Nikos Lyris, Vanessa Taieb, Jason Eells; drafting the article or revising it critically for important intellectual content: Phillip J. Mease, Richard B. Warren, Peter Nash, Jean-Marie Grouin, Damon Willems, Nikos Lyris, Vanessa Taieb, Jason Eells, Iain B. McInnes; final approval of the version of the article to be published: Phillip J. Mease, Richard B. Warren, Peter Nash, Jean-Marie Grouin, Damon Willems, Nikos Lyris, Vanessa Taieb, Jason Eells, Iain B. McInnes.

Funding

This study and its publication, including the Journal’s Rapid Service Fee, was sponsored by UCB Pharma and supported by the NIHR Manchester Biomedical Research Centre (NIHR203308). This article was based on the original studies BE OPTIMAL (NCT03895203), BE COMPLETE (NCT03896581), and BE VITAL (NCT04009499) sponsored by UCB Pharma. Support for third-party writing assistance for this article was funded by UCB Pharma and provided by Darryl Low, PhD, Cytel Inc, UK, in accordance with ISMPP Good Publication Practice (GPP 2022) guidelines [28].

Data Availability

Data from the bimekizumab clinical trials used in this analysis may be requested by qualified researchers 6 months after product approval in the US and/or Europe, or global development is discontinued, and 18 months after trial completion. Investigators may request access to anonymized individual patient data and redacted study documents, which may include: raw datasets, analysis-ready datasets, study protocol, blank case report form, annotated case report form, statistical analysis plan, dataset specifications, and clinical study report. Prior to the use of the data, proposals need to be approved by an independent review panel at www.Vivli.org, and a signed data-sharing agreement will need to be executed. All documents are available in English only, for a pre-specified time, typically 12 months, on a password-protected portal.

Declarations

Conflict of Interest

Phillip J. Mease: Research grants from AbbVie, Acelyrin, Amgen, BMS, Celgene, Eli Lilly, Gilead, Janssen, Novartis, Pfizer, Sun Pharma and UCB Pharma; consultancy fees from AbbVie, Acelyrin, Aclaris, Amgen, Boehringer Ingelheim, BMS, Celgene, Eli Lilly, Galapagos, Gilead, GSK, Janssen, Moonlake Pharma, Novartis, Pfizer, Sun Pharma, Takeda, and UCB, and Ventyx Pharma; speakers’ bureau from AbbVie, Amgen, Eli Lilly, Janssen, Novartis, Pfizer, and UCB Pharma. Richard B. Warren: Supported by the Manchester NIHR Biomedical Research Centre; consulting fees from AbbVie, Almirall, Amgen, Arena, Astellas, Avillion, Biogen, BMS, Boehringer Ingelheim, Celgene, DICE Therapeutics, Eli Lilly, GSK, Janssen, LEO Pharma, Meiji Pharma, Novartis, Pfizer, RAPT Therapeutics, Sanofi, Sun Pharma, UCB Pharma and Union; research grants to his institution from AbbVie, Almirall, Janssen, LEO Pharma, Novartis, Pfizer, and UCB Pharma; and honoraria from AbbVie, Almirall, BMS, Eli Lilly, Galderma, Janssen and Novartis. Peter Nash: Research grants, clinical trials and honoraria for advice and lectures on behalf of AbbVie, Boehringer Ingelheim, BMS, Celgene, Eli Lilly, Galapagos/Gilead, GSK, Janssen, Novartis, Pfizer, Samsung and UCB Pharma. Jean-Marie Grouin: Consulting fees and honoraria from Acticor, Chugai, BeiGene, Inflectis, Inotrem, Ipsen, Janssen, Otsuka, SpikImm, UCB Pharma. Nikos Lyris, Damon Willems, Vanessa Taieb, Jason Eells: Employees and shareholders of UCB Pharma. Iain B. McInnes: Consulting fees and honoraria from AbbVie, AstraZeneca, BMS, Boehringer Ingelheim, Cabaletta, Causeway Therapeutics, Celgene, Evelo, Janssen, Novartis, Eli Lilly, Moonlake, and UCB Pharma; and research support from BMS, Boehringer Ingelheim, Celgene, Janssen, Novartis, and UCB Pharma.

Ethical Approval

BE OPTIMAL and BE COMPLETE were conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and the International Conference on Harmonisation Guidance for Good Clinical Practice. Ethical approval was obtained from the relevant institutional review boards at participating sites, and all patients provided written informed consent by local requirements. This article is based on previously conducted studies and does not contain any new studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Footnotes

Prior Presentation: The data in this manuscript were previously shared at the Academy of Managed Care Pharmacy Congress 2024, New Orleans, LA, 15–18 April 2024 (Poster No. L19).

References

- 1.Stober C. Pathogenesis of psoriatic arthritis. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. 2021;35(2): 101694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Azuaga AB, Ramirez J, Canete JD. Psoriatic arthritis: pathogenesis and targeted therapies. Int J Mol Sci. 2023;24(5):4901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gossec L, Baraliakos X, Kerschbaumer A, et al. EULAR recommendations for the management of psoriatic arthritis with pharmacological therapies: 2019 update. Ann Rheum Dis. 2020;79(6):700–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Coates LC, Soriano ER, Corp N, et al. Group for Research and Assessment of Psoriasis and Psoriatic Arthritis (GRAPPA): updated treatment recommendations for psoriatic arthritis 2021. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2022;18(8):465–79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ritchlin CT, Coates LC, McInnes IB, et al. Bimekizumab treatment in biologic DMARD-naive patients with active psoriatic arthritis: 52-week efficacy and safety results from the phase III, randomised, placebo-controlled, active reference BE OPTIMAL study. Ann Rheum Dis. 2023;82(11):1404–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Merola JF, Landewe R, McInnes IB, et al. Bimekizumab in patients with active psoriatic arthritis and previous inadequate response or intolerance to tumour necrosis factor-alpha inhibitors: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial (BE COMPLETE). Lancet. 2023;401(10370):38–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Coates LC, Landewe R, McInnes I, Mease P, Ritchlin C, Tanaka Y. Sustained efficacy and safety of bimekizumab in patients with active psoriatic arthritis and prior inadequate response to tumour necrosis factor inhibitors: results from the phase 3 BE COMPLETE study and its open-label extension up to 1 year EULAR. 2023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 8.Kristensen LE, Keiserman M, Papp K, et al. Efficacy and safety of risankizumab for active psoriatic arthritis: 52-week results from the KEEPsAKE 1 study. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2022;62(6):2113–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ostor A, Van den Bosch F, Papp K, et al. Efficacy and safety of risankizumab for active psoriatic arthritis: 52-week results from the KEEPsAKE 2 study. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2022;62(6):2122–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vecellio M, Hake VX, Davidson C, Carena MC, Wordsworth BP, Selmi C. The IL-17/IL-23 axis and its genetic contribution to psoriatic arthritis. Front Immunol. 2020;11: 596086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mease PJ, Gladman DD, Merola JF, et al. Comparative effectiveness of bimekizumab in patients with psoriatic arthritis: results from a systematic literature review and network meta-analysis. Rheumatology. 2024 (Online ahead of print).

- 12.Maloney A, Dua P, Ahmed GF. Comparative effectiveness of bimekizumab in psoriatic arthritis: a model-based meta-analysis of american college of rheumatology response criteria. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2024;115(5):1007–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Deodhar A. Mirror, mirror, on the wall, which is the most effective biologic of all? J Rheumatol. 2018;45(4):449–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dias S, Sutton AJ, Ades AE, Welton NJ. Evidence synthesis for decision making 2: a generalized linear modeling framework for pairwise and network meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Med Decis Mak. 2013;33(5):607–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Phillippo DM, Ades AE, Dias S, Palmer S, Abrams KR, Welton NJ. Methods for population-adjusted indirect comparisons in health technology appraisal. Med Decis Mak. 2018;38(2):200–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Warren RB, McInnes IB, Nash P, et al. Comparative effectiveness of bimekizumab and guselkumab in patients with psoriatic arthritis at 52 weeks assessed using a matching-adjusted indirect comparison. Rheumatol Ther. 2024;11:829–39 (Online ahead of print). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mease PJ, Warren RB, Nash P, et al. Comparative effectiveness of bimekizumab and secukinumab in patients with psoriatic arthritis at 52 weeks using a matching-adjusted indirect comparison. Rheumatol Ther. 2024;11:817–28 (Online ahead of print). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ. 2021;372: n71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.EMA. Risankizumab —summary of product characteristics 2023 [cited 15 January 2024. https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/product-information/skyrizi-epar-product-information_en.pdf].

- 20.Strober V, Kivitz A, Ostor A, et al. Improvements in manifestations of active psoriatic arthritis with risankizumab treatment after intolerance or inadequate response to prior biologic therapy: subgroup analyses From the KEEPsAKE 2 trial. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2023;89(3):Supplement AB179. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nash P, McInnes IB, Mease PJ, et al. Secukinumab versus adalimumab for psoriatic arthritis: comparative effectiveness up to 48 weeks using a matching-adjusted indirect comparison. Rheumatol Ther. 2018;5(1):99–122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Strand V, McInnes I, Mease P, et al. Matching-adjusted indirect comparison: secukinumab versus infliximab in biologic-naive patients with psoriatic arthritis. J Comp Eff Res. 2019;8(7):497–510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Signorovitch JE, Sikirica V, Erder MH, et al. Matching-adjusted indirect comparisons: a new tool for timely comparative effectiveness research. Value Health. 2012;15(6):940–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tillett W, Eder L, Goel N, et al. Enhanced patient involvement and the need to revise the core set - report from the psoriatic arthritis working group at OMERACT 2014. J Rheumatol. 2015;42(11):2198–203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Menter A, Krueger GG, Paek SY, Kivelevitch D, Adamopoulos IE, Langley RG. Interleukin-17 and interleukin-23: a narrative review of mechanisms of action in psoriasis and associated comorbidities. Dermatol Ther (Heidelb). 2021;11(2):385–400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Macchioni P, Salvarani C, Possemato N, et al. Ultrasonographic and clinical assessment of peripheral enthesitis in patients with psoriatic arthritis, psoriasis, and fibromyalgia syndrome: the ULISSE study. J Rheumatol. 2019;46(8):904–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Di Matteo A, Smerilli G, Di Donato S, et al. Power Doppler signal at the enthesis and bone erosions are the most discriminative OMERACT ultrasound lesions for SpA: results from the DEUS (defining enthesitis on ultrasound in spondyloarthritis) multicentre study. Ann Rheum Dis. 2024;83(7):847–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.DeTora LM, Toroser D, Sykes A, et al. Good publication practice (GPP) guidelines for company-sponsored biomedical research: 2022 update. Ann Intern Med. 2022;175(9):1298–304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data from the bimekizumab clinical trials used in this analysis may be requested by qualified researchers 6 months after product approval in the US and/or Europe, or global development is discontinued, and 18 months after trial completion. Investigators may request access to anonymized individual patient data and redacted study documents, which may include: raw datasets, analysis-ready datasets, study protocol, blank case report form, annotated case report form, statistical analysis plan, dataset specifications, and clinical study report. Prior to the use of the data, proposals need to be approved by an independent review panel at www.Vivli.org, and a signed data-sharing agreement will need to be executed. All documents are available in English only, for a pre-specified time, typically 12 months, on a password-protected portal.