Abstract

Targeting lung cancer stem cells (LC-SCs) for metastasis may be an effective strategy against lung cancer. This study is the first on epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) properties of boric acid (BA) in LC-SCs. LC-SCs were isolated using the magnetic cell sorting (MACS) method. Tumor-sphere formation and flow cytometry confirmed CSC phenotype. The cytotoxic effect of BA was measured by MTT analysis, and the effect of BA on EMT was examined by migration analysis. The expression levels of ZEB1, SNAIL1, ITGA5, CDH1, ITGB1, VIM, COL1A1, and LAMA5 genes were analyzed by RT-qPCR. E-cadherin, Collagen-1, MMP-3, and Vimentin expressions were analyzed immunohistochemically. Boric acid slightly reduced the migration of cancer cells. Increased expression of transcription factor SNAIL (p < 0.001), but not ZEB1, was observed in LC-SCs. mRNA expression levels of ITGB1 (p < 0.01), ITGA5 (p < 0.001), COL1A1 (p < 0.001), and LAMA5 (p < 0.001) increased; CDH1 and VIM decreased in LC-SCs. Moreover, while E-cadherin (p < 0.001) and Collagen-1 (p < 0.01) immunoreactivities significantly increased, MMP-3 (p < 0.001) and Vimentin (p < 0.01) immunoreactivities decreased in BA-treated LC-SCs. To conclude, the current study provided insights into the efficacy and effects of BA against LC-SCs regarding proliferation, EMT, and cell death for future studies.

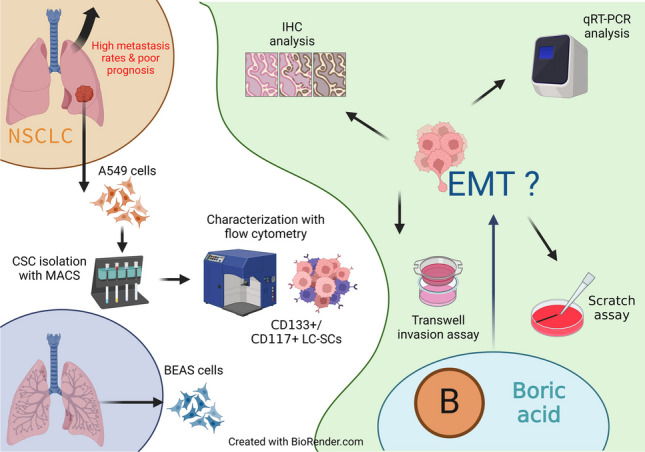

Graphical abstract

Keywords: Lung cancer, Cancer stem cell, Boric acid, Epithelial-mesenchymal transition, Cytotoxicity

Introduction

Lung cancer, which caused the death of more than 1.5 million people worldwide according to 2020 data, continues to be a significant cause of mortality despite newly developed treatment methods (Kerpel-Fronius et al. 2021). It is the most frequent cancer and cause of cancer death in both men and women worldwide (Bade and Dela Cruz 2020). While 80–85% of lung cancer cases are non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC), the remaining 20–15% are small cell lung cancer (SCLC) (Abughanimeh et al. 2022). Disease progression and 5-year survival rates in NSCLC are severely poor, and one of the most important reasons is the high metastasis rates in NSCLC patients (Xu et al. 2020). Another problem is that although the cisplatin-based chemotherapy approach and combined treatments, which may differ according to the type of cancer, are successful initially, they lose their effectiveness due to the development of drug resistance (Duruisseaux and Esteller 2018).

Cancer tissue consists of a heterogeneous population of cells. Some of these cells have the features of self-renewal, high differentiation capacity, and the ability to form colonies by migrating out of the tissue. These cells, responsible for maintaining the tumor mass, exhibit stem cell properties (Raniszewska et al. 2021). In addition, these cells, which have different karyotypes, surface markers, genetic abnormalities, and proliferation rates from others, also differ in sensitivity to chemotherapy and radiotherapy (Prasetyanti and Medema 2017). These cells, called cancer stem cells (CSCs), constitute less than 1% of the cell population in many solid tumors. However, these highly tumorogenic cells increase tumor progression considerably, resulting in treatment resistance. Many intrinsic and extrinsic factors play a role in the resistance mechanisms of CSCs, including the epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) (Najafi et al. 2019).

EMT is a process in which adherent epithelial cells transform into motile mesenchymal phenotype and is involved in processes such as embryogenesis, tissue regeneration, and wound healing. It is also responsible for tumor metastasis because a cancer cell that acquires a mesenchymal phenotype can cross endothelial barriers and enter systemic circulation (Babaei et al. 2022). EMT is regulated by controlling the expression of various combinations of genes that induce mesenchymal cellular state while suppressing epithelial cellular features (Dongre and Weinberg 2019). Although multiple mechanisms are involved in the local invasion and metastasis of NSCLC, EMT seems critical (Mahmood et al. 2017).

Boric acid (BA) is the most common form of boron, an essential element for animals and plants. BA is a vital potential resource for cancer treatment due to some of its chemical properties. It is known that exposure to boric acid reduces the incidence of prostate cancer in men and cervical and lung cancers in women (Barranco and Eckhert 2004). Various studies have shown that boron compounds have the potential to inhibit invasion and migration in some types of cancer. These studies show that boric acid reduces cell proliferation and stimulates apoptosis in prostate, melanoma, breast, and colon cancer cells (Sevimli et al. 2022). Although the number of studies investigating the effects of boron compounds on various cancer cells is increasing, it is seen that there are not enough studies examining their effects on cancer stem cells.

In this study, we looked at the effects of BA on the EMT properties of cancer stem cells. First, cancer stem cells were isolated from A549 cells with MACS. Then, normal bronchial epithelial cells, A549 cells, and cancer stem cells were cultured. After cytotoxicity studies, an in vitro wound healing experiment was performed to investigate BA’s effect on migration. The expression levels of some genes that play a crucial role in migration were analyzed with RT-qPCR. In addition, the presence of some essential proteins in cell migration was investigated by the immunohistochemical method.

Materials and methods

Cells

A549 (human lung carcinoma; CCL-185) and BEAS-2B (human bronchial epithelium; CRL-9609) cell lines were purchased commercially from the American Type Culture Collection. A549 cells were cultured in RPMI-1640 (Capricorn Scientific, RPMI-A) medium containing 10% FBS (GIBCO, 16,000,044) and 1% penicillin–streptomycin (Sigma-Aldrich, P4333-100ML). In contrast, BEAS-2B cells were cultured in Eagle’s minimum essential medium (GIBCO, 11,430,030) containing 10% FBS and 1% penicillin–streptomycin at 37 °C in 5% CO2.

Immunomagnetic isolation of lung cancer stem cells

CD133 and CD117 have been recognized as critical cell surface biomarkers for tumor-initiating cells in lung cancer (Herpel et al. 2011). When A549 cells reached sufficient numbers for cancer stem cell isolation, lung cancer stem cells (LC-SCs) were isolated by magnetic cell separation (MACS) technique using monoclonal antibodies against CD117 and CD133. Cells tested for isolation efficiency (purity and viability) were cultured as spheroid bodies (tumorospheres) until sufficient numbers were reached for further analysis.

Detection of the efficiency of LC-SC isolation with tumorsphere formation assay

CD133 + and CD117 + cells were incubated for 3D Tumorsphere Medium XF (PromoCell, cat. no C-28070) medium at 1 × 106 cells/ml, then cultured for 4–10 days with a medium change every 3–4 days. Tumorsphere formation was observed and photographed by an inverted microscope (Zeiss, Germany).

Detection of the efficiency of LC-SC isolation with flow cytometry

The efficiency of LC-SC isolations was analyzed by flow cytometry. For this purpose, cells were incubated for 45 min at room temperature in the dark with FITC-conjugated monoclonal antibodies specific for CD133 (Biolegend, cat. no 393906) and CD117 (Biolegend, cat. no 313216) surface markers and appropriate isotype controls, followed by washing with PBS (Capricorn, cat. no PBS-1A) solution containing 0.1% sodium azide, centrifuged at 1300 rpm for 5 min. The prepared cell suspensions were read in the AGILENT NovoCyte D3005 device and analyzed with the software program.

Cytotoxicity analysis

The effect of BA on the viability of A549 and LC-SCs was evaluated by MTT assay. The cells were seeded at a density of 5 × 103 per well in the 96-well plates and waited until adherent. Different concentrations of BA solutions (1 mM, 10 mM, 12.5 mM, 25 mM, 50 mM, 75 mM, and 100 mM) prepared with culture medium without FBS were applied to the cells. Plates were incubated for 24 and 48 h at 37 °C in 95% relative humidity in a 5% CO2 incubator. At the end of the incubation periods, MTT (Invitrogen, cat.no M6494) solution was added to each well and incubated for 2–4 h. At the end of this period, the medium was removed, and the DMSO (Invitrogen, cat.no D12345) solution was added in dark conditions. Then, the plates were analyzed at 540-nm wavelength with a microplate reader (Biotek ELx808IU, USA). The effective doses of BA are determined statistically by comparing the treated groups with the control group.

Wound healing (scratch) assay

For this assay, cells were seeded at 1 × 106 cells/well in 6-well culture dishes and cultured until confluent for about 24 h. Then, a wound model was created by scratching each well with the help of a sterile 1000-µl pipette tip. Next, cell debris and cells that had lost their adhesion were removed by washing twice with PBS. Finally, cells were cultured with an appropriate medium for 48 h. Meanwhile, images were acquired at 0, 6, 24, and 48 h. Images were analyzed using the Image J program “Wound healing size tool,” and wound area, healing speed, wound distance, and cell front velocity were calculated (Pijuan et al. 2019; Suarez-Arnedo et al. 2020).

RNA extraction and quantitative real-time PCR

Total RNA extraction was performed using an RNA isolation kit (RNeasy Micro Kit, Qiagen, Cat. No: 74004). cDNAs were obtained from RNAs using a cDNA synthesis kit (Qiagen, Cat. No: 330404). For real-time PCR reaction, master mix solution containing SYBR Green (Qiagen, Cat. No: 330501) and primers specific for ZEB1, SNAIL1, ITGA5, CDH1, ITGB1, VIM, COL1A1, and LAMA5 (Table 1) were used. Analyses were performed with the Rotorgene Q5 plex + HRM real-time PCR device, and the results were obtained with the Rotor gene Q software program. Changes in the gene expression levels were analyzed by the 2−ΔΔCt method.

Table 1.

Primer sequences used in RT-qPCR analysis

| Gene name | Primer sequence |

|---|---|

| GAPDH |

F: CACCCTGTTGCTGTAGCCATATTC R: GACATCAAGAAGGTGGTGAAGCAG |

| ZEB1 |

F: CACCTCTCTGAGGCTGTG R: CGTCATGTAAGCATCAATCAC |

| SNAIL1 |

F: ACAACCTGGAAGCTCAGT R: TTAATACGCAGCAAACCAACA |

| ITGA5 |

F: TGATAGTAGTGTTAGTGATGCAAA R: CAGCTAAAGGATTAATGGCAC |

| CDH1 |

F: ATCATTCACCCTTGGCAC R: CATGGAAGCCATTGTCCT |

| ITGB1 |

F: CCTGATGCCTGTACACCTCTT R: GCAGGCCGAGTACTGTTA |

| VIM |

F: CTTGGGACAGAACCTAAAATG R: GACGTCTCAGGTAGTGAAGAA |

| COL1A1 |

F: TGAGGGTACCTTTAGGCCAGA R: CACTGCCAGAGAGACCATACC |

| LAMA5 |

F: AGAGTGAAGATGAGTTGACACCTT R: CCAAGAGATCTCGATCACTGC |

GAPDH glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase; ZEB1 zinc finger E-box binding homeobox 1; SNAIL1 snail family transcriptional repressor 1; ITGA5 integrin alpha-5; CDH1 cadherin-1; ITGB1 integrin subunit beta 1; VIM Vimentin; COL1A1 Collagen, type 1, alpha 1; LAMA5 laminin subunit alpha 5; F forward primer 5' to 3'; R reverse primer 5' to 3'

Histochemical analysis

The presence of some essential proteins in cell migration was investigated with the immunohistochemical method. After coverslips were placed in 24-well culture dishes, cells were seeded and incubated until adherence. Then, the cells in the whole group were cultured for 24 and 48 h by applying BA at the IC50 dose determined by the cytotoxicity assays. At the end of the period, the cells were washed with PBS and fixed with methanol. Next, the samples were washed with PBS and incubated for 30 min with PBS containing 1.5% normal block serum. Next, primary antibodies (E-cadherin, Collagen-1, MMP-3, and Vimentin) prepared in appropriate proportions with the dilution solution were added and incubated for 2 h at room temperature. Subsequently, washing with PBS and histochemical marking were performed using the DAB Substrate Kit (Abcam, ab64238). The preparations were covered with a crystal mounting medium and analyzed under a Leica DMI 4000 Microsystems light microscope, and images were taken.

Statistical analysis

Each experiment was repeated at least three times. Obtained data were evaluated as mean ± SD and assessed with Student’s t-test and Tukey test. The significance level p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant for the differences between the study and control groups. All statistical analyzes were performed with GraphPad Prism 7.0 program.

Results

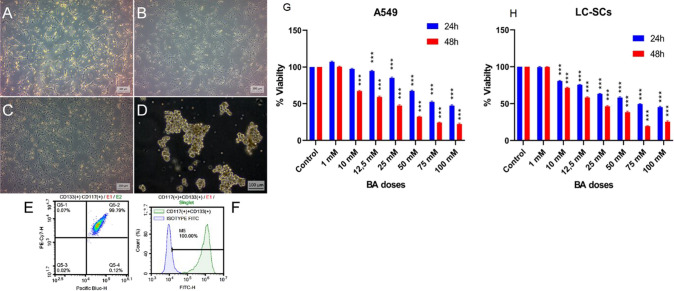

Morphological analysis of cells

BEAS-2B, A549, and LC-SCs (CD117 + /CD133 +) exhibited adhesive properties and epithelial morphology in monolayer culture conditions (Fig. 1A, B, and C). CD133 + /CD117 + LC-SCs isolated from A549 cells were also cultured as spheroid cultures to confirm cancer stem cell properties. It was observed that cells could form spheroids of appropriate shape and size (Fig. 1A–D). The other experimental studies were conducted by culturing the cells as monolayer cultures.

Fig. 1.

The morphology, tumorsphere formation, lung cancer stem cells (LC-SCs) characterization, dose–response columns, and IC50 boric Acid (BA) values. Cell viability was measured with the MTT assay. A BEAS-2B (human bronchial epithelium) cells (scale bar = 200 µm). B A549 (human lung carcinoma) cells (scale bar = 200 µm). C CD133 + /CD117 + LC-SCs isolated from A549 cells (scale bar = 200 µm). D Tumorspheres formation of CD133 + /CD117 + LC-SCs (scale bar = 100 µm). E, F Identification of CD133 + /CD117 + LC-SCs by flow cytometry. G A549 and H LC-SCs were exposed to different concentrations of BA (1, 10, 12.5, 25, 50, 75, and 100 mM) for 24 and 48 h. (C, control; BA, boric acid)

Identification of CD117 + /CD133 + cells

The MACS and flow cytometry methods showed the purity of CD133 + and CD117 + cells. Figure 1E and F shows that the CD133 + and CD117 + cell population was 100.0% (Fig. 1E and F).

Cytotoxicity analysis

It was observed that there was no significant difference between BA and control groups in A549 cells at a dose of 1 mM and 10 mM at 24 h and only 1 mM at 48 h. In other doses, it was observed that cell viability was significantly decreased in BA groups at both 24 and 48 h compared to the control group (all p < 0.005) (Fig. 1G). Cell viability was 48% and 28%, with the maximum dose at 24 and 48 h, respectively. In the analysis with LC-SCs, no difference was observed in cell viability between BA and control groups at 1 mM dose. In contrast, at other doses, it was observed that the viability of BA groups decreased significantly at both 24 and 48 h compared to the control group (all p < 0.005) (Fig. 1H). At the maximum dose, cell viability was found to be 48% and 23% in BA groups at 24 and 48 h, respectively. The 50% inhibitory concentrations of BA against A549 cells were found at 43.38 and 76.8, and for LC-SCs, were found at 47.8 mM and 75.8 mM for 24 and 48-h long experiments, respectively.

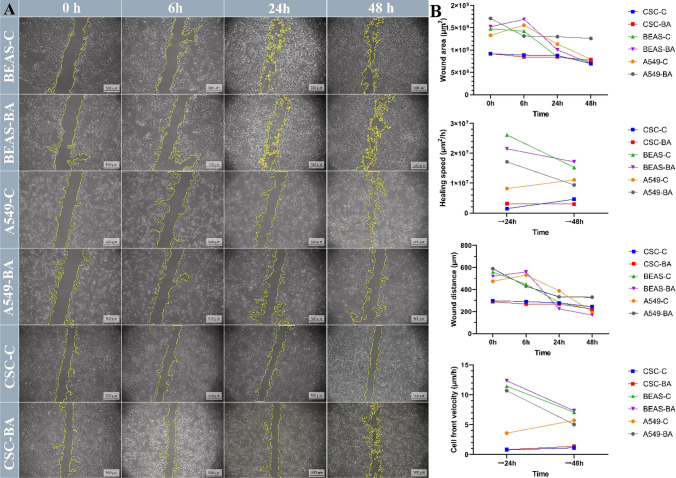

Wound healing assay

The effect of BA on cell migration was investigated with the wound healing method. BEAS, A549, and LC-SCs were treated initially and compared to untreated cells during 48 h by time-lapse imaging. The images represent the cell migration status at the start (0 h), 6 h, 24 h, and the end (48 h) (Fig. 2A).

Fig. 2.

Analysis of BEAS, A549, and cancer stem cell migration by in vitro wound healing assay. A Time-lapse microscopy images of wound closure of untreated (BEAS-C, A549-C, and CSC-C) and treated with boric acid (BA 50 Mm) BEAS, A549, and cancer stem cells at 0, 6, 24, and 48 h after culture insert removal. The dotted lines define the area lacking cells (scale bars, 500 μm). B Scratch area in μm2, speed of healing in µm2/h, wound distance in μm, and rate of cell front velocity in μm/h. All the measurements and parameters were taken for 48 h

According to the results of migration analysis, the wound area in BEAS cells decreased similarly in the BA and control groups at 0 to 48 h. In this respect, it was observed that BA did not significantly affect the migration in these cells. In A549 cells, at the end of the 48th hour, it was observed that the wound area was more extensive in the BA group compared to the control group, which means BA reduced the migration in these cells. In cancer stem cells, it was observed that the wound area remained more stable in both the control and BA groups compared to other cell lines, and there was a lower level of decrease (Fig. 2A, B). Similar results were obtained when the wound distance results were compared. It was observed that the wound distances tended to decrease in all groups, but this decrease was more stable, especially in the LC-SC groups (Fig. 2B). It was observed that wound healing speeds tended to increase between 24 and 48 h in the A549 control and LC-SC control groups, while they tended to decrease in the BEAS control, BEAS BA, and A549 BA groups. The wound healing speed remained approximately constant in the LC-SC control group (Fig. 2B). When the cell front velocity results were evaluated, it was observed that the velocity decreased similarly between 24 and 48 h in the BEAS control and BEAS BA groups. In A549 cells, on the other hand, it was observed that the rate tended to increase in the control group while it tended to decrease in the BA group. In the LC-SC control and BA groups, it was observed that the rate grew to change less between 24 and 48 and remained partially constant (Fig. 2B).

RT-qPCR results

RT-qPCR analysis was performed after administration of 50 mM at 24 h and 75 mM at 48 h of BA for determining the expression levels of ZEB1, SNAIL1, ITGA5, CDH1, ITGB1, VIM, COL1A1, and LAMA5 genes responsible for epithelial-mesenchymal transition. CDH1 expression of LC-SCs after BA treatment for 24 h was upregulated compared to the control group (p < 0.001) (Fig. 3). ITGB1 expression was upregulated in A549 cells (p < 0.001), and LC-SCs (p < 0.01) were treated with BA at 24 h, for 48 h it was upregulated in A549 (p < 0.05) compared to the control group (Fig. 3). ITGA5 expression was upregulated in A549 cells (p < 0.001) and LC-SCs (p < 0.001) after BA treatment for 24 h, but it was upregulated in only A549 cells (p < 0.01) after 48 h of treatment. ZEB expression was upregulated in only A549 cells after 24 h of BA treatment. SNAIL1 expression, a critical EMT transcription factor, was upregulated in LC-SCs compared with the control group after 24 h of BA treatment (p < 0.001). down (Fig. 3). VIM expression was upregulated in A549 cells (p < 0.01) after 24 h of BA treatment but it was upregulated only non-treated A549 cells (p < 0.001) and LC-SCs (p < 0.001) after 48 h non-up interestingly (Fig. 3). COL1A1 expression was upregulated in A549 cells (p < 0.001) and LC-SCs (p < 0.001) compared with the control group after 48 h of BA treatment. LAMA5 expression was upregulated in A549 cells (p < 0.001) and CSCs (p < 0.001) after 48 h BA treatment (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

mRNA expressions of EMT markers were detected by RT-qPCR after treatment of 50 mM 24 h and 75 mM 48 h BA with BEAS-2B, A549, and LC-SCs. GAPDH was used as a control. qRT-PCR was performed as described in the “Materials and methods” section. (mean ± SD, n = 3, *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, and ***p < 0.001; ns means not significant)

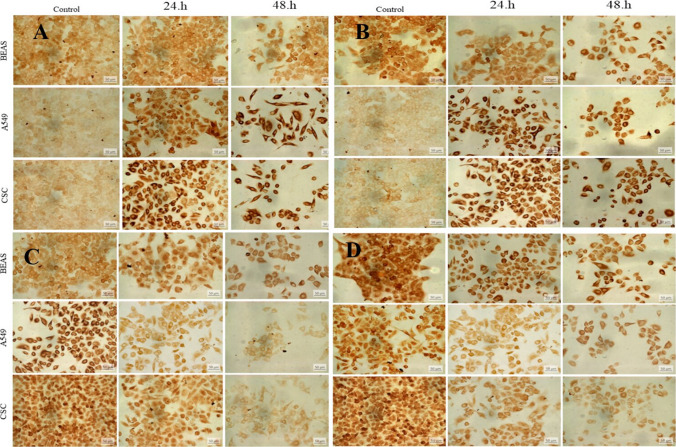

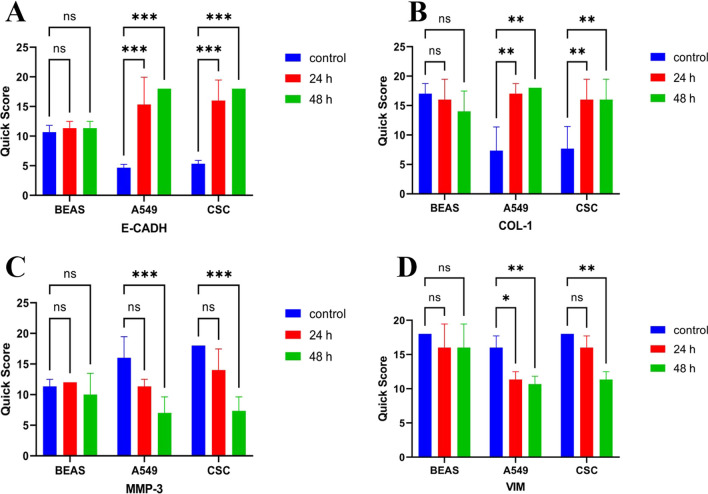

Immunohistochemical assessment

Immunohistochemical studies were performed to observe the expression of E-cadherin, Collagen-1, MMP-3, and Vimentin proteins, essential in epithelial-mesenchymal transition in BA-treated A549, BEAS-2B, and LC-SCs. E-cadherin (Figs. 4A and 5A, p-value < 0.001***), Collagen-1 (Figs. 4B and 5A, p-value < 0.01**) expression showed a significant increase both in A549 and LC-SCs treated with 50 mM BA for 24 h and 48 h and compared to the control group (p-value < 0.001***, p-value < 0.01**, respectively). Conversely, the expression of MMP3 (Figs. 4C and 5C) and Vimentin (Figs. 4D and 5D) decreased in LC-SCs compared to the control group (p-value < 0.001***, p-value < 0.01**, respectively).

Fig. 4.

Immunoreactivity of E-cadherin (A), Collagen-1 (B), MMP-3 (C), and Vimentin (D), respectively, in BEAS-2B, A549, and LC-SCs in 24 and 48-h cultures exposed to standard culture conditions or 50 mM boric acid (scale bars = 50 µm)

Fig. 5.

Percentage graph of immunoreactivity of E-cadherin (A), Collagen-1 (B), MMP-3 (C), and Vimentin (D), respectively, in BEAS-2B, A549, and LC-SCs in 24 and 48-h cultures exposed to standard culture conditions or 50 mM boric acid (scale bars = 50 µm) (mean ± SD, n = 3, *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, and ***p < 0.001)

Discussion

In epithelial cancers, epithelial cells transform into mesenchymal cells with increased invasive properties due to loss of intercellular adhesion and motility gain. The epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT), initially called epithelial-mesenchymal transformation, is necessary for acquiring and maintaining the CSC character and is directly related to cancer’s recurrence and metastasis processes. However, the mechanisms regulating these processes are still unknown (Ribatti et al. 2020; Walcher et al. 2020; Zou et al. 2021; Césaire et al. 2022; Jinesh and Brohl 2022). Our study aimed to develop a successful method that does not result in recurrence and metastases and has meager side effects in lung cancer, a significant health problem with high incidence and mortality rates. In the present study, IC50 of BA was calculated, and a single shared dose that could be used for 24 and 48 h in all cell lines was determined as 50 mM and 75 mM, respectively. Many new agents, such as boric acid, are being investigated for their anti-cancer properties to support the standard chemotherapy used in cancer treatment. For example, WHO classified boron as a trace element like Se, Zn, and Cu in 1980. Recent research has demonstrated the non-toxic potential of various boron compounds on healthy cells based on in vitro and in vivo studies (Nedunchezhian et al. 2016, Das et al. 2022; Messner et al. 2022). Epidemiological and experimental studies have shown that boron positively affects various types of cancer (Kahraman and Göker 2022, Hacioglu et al. 2023).

Furthermore, BA reduced the expression of some miRNA expressions (Mahabir et al. 2008). In addition, BA affected the migration and apoptotic characters of A549 cells (Celebı et al. 2024). In our previous study, we observed that BA suppresses SW-480 cell proliferation and induces apoptosis both in 2D and 3D culture conditions, and the apoptotic process was related to the TNF signaling pathway (Sevimli et al. 2022). Boric acid has been shown to have potential anti-cancer properties that suppress cancer cell proliferation in many cancer cell lines. Although the mechanism underlying the anti-cancer effects of boric acid is not yet precise, various theories have been proposed (Mahabir et al. 2008; Kahraman and Göker 2022). For example, boric acid and borax have been reported to exert anti-cancer effects concerning BRAF/MAPK, PTEN, and PI3K/AKT signaling pathways in glioblastoma cells (Turkez et al. 2021). Therefore, our study aimed to examine the effects of boric acid. This compound reduces cell proliferation in various cancer cells and causes apoptosis with low side effect rates on the EMT feature of LC-SCs. In addition, we aimed to contribute to elucidating the molecular mechanisms of EMT, which are vital in the formation and maintenance of CSCs and are responsible for cancer recurrence and metastases.

The mechanisms underlying metastasis are crucial for the survival of cancer cells. Zinc-finger transcriptional factors such as SNAIL, SLUG, TWIST, ZEB1, SIP1, and E47 are critical in inducing EMT by inhibiting E-cadherin. In addition, numerous signaling pathways such as TGFβ, Wnt, NF-κB, Notch, integrins, and tyrosine kinase receptors (EGF, FGF, HGF, PDGF, IGF) are crucial in the pathway to EMT (Chang et al. 2021). In our study, the expression levels of ZEB1, SNAIL1, ITGA5, CDH1, ITGB1, VIM, COL1A1, and LAMA5 genes play a crucial role in EMT were investigated with RT-qPCR at the molecular level. We also determined the expression of E-cadherin, Collagen-1, MMP-3, and Vimentin at the protein level immunohistochemically. LC-SCs treated with BA significantly increased E-cadherin and Collagen-1 expression compared to the control group.

Conversely, expression of MMP3 and Vimentin decreased in LC-SCs compared to the control group. Therefore, BA could inhibit the EMT of lung cancer stem cells by reducing E-cadherin and Collagen-1 expression. LC-CSCs are becoming an increasingly studied target for the treatment of lung cancer. Accordingly, several pharmaceutical companies are attempting to develop anti-cancer drugs targeting CSCs specifically, and several drugs are being used in patients (Kahm et al. 2021).

At the end of the 24th hour with 50 mM BA administration, CDH1 expression was upregulated in A549 and LC-SCs. E-cadherin expression was also increased at the protein level in LC-SCs compared to the control group. Application of 50 mM BA was shown to be more effective in LC-SCs by increasing CDH1 expression. Transcriptional repressors like ZEB1 and SNAIL expressions could not repress CDH1 expression, a hallmark in EMT, so that CDH1 expression could be upregulated. In addition, some miRNAs post-transcriptionally could induce the expression CDH1.

Various markers have been defined to indicate EMT. For example, E-cadherin, integrin, and cytokeratins are epithelial markers; N-cadherin, Vimentin, and fibronectin are widely used as mesenchymal markers (Loh et al. 2019; Imran et al. 2021). However, EMT’s most prominent distinguishing feature is the loss of E-cadherin expression (Kang and Massagué 2004).

ITG1 expression did not show variability between doses. However, ITGB1 and ITGA5 expression was upregulated in A549 and LC-SCs compared to the control group after 24 h and 48 h of BA administration in the present study. In both CSCs and other tumor cells, integrin expression can be induced by signals from the microenvironment and EMT steps by increased integrin signaling. The mesenchymal integrins α5 (ITGA5) and β1 form fibronectin heterodimers to cells for adhesion (Seguin et al. 2015). Studies in breast, ovarian, and colon cancer cells have shown that ITGA5 promotes migration by activating focal adhesion kinase. Furthermore, ITGA5 expression increases with the EMT process, thus suggesting that ITGA5 expression is associated with cancer progression (Qin et al. 2011; Gong et al. 2016; Yu et al. 2019; Ayama-Canden et al. 2022).

Snail and Slug are the most critical EMT-TFs. These factors bind directly to and suppress E-cadherin, reshaping intercellular adhesion. SNAIL and ZEB activate mesenchymal genes by suppressing other epithelial markers (Cho et al. 2019). These factors have also shown different expression profiles in various cancer types. While ZEB1/2 is associated with a poor prognosis in basal-type aggressive breast cancers, poor expression is associated with a good prognosis in luminal-type breast cancers (Ichikawa et al. 2022). In mesenchymal-like cells, low levels of E-cadherin and high levels of Vimentin and ZEB1/2 expression were reported.

In contrast, in other epithelium-like cells, low levels of Vimentin and ZEB1/2 and high levels of E-cadherin were reported (Osada et al. 2019). In our study, ZEB1 expression was upregulated in A549 cells treated with BA at 24 h compared to the control group. On the other hand, SNAIL1 expression was upregulated in LC-SCs compared with the control group after 24 h of BA treatment.

Vimentin plays a regulatory role in regulating cell function in multiple physiological activities (Peuhu et al. 2017). At the cellular level, it is essential in cell migration, differentiation, proliferation, adhesion, and invasion; it also plays crucial roles in the mammary gland, nervous system, and angiogenesis (Cheng et al. 2016). We observed that VIM expression was upregulated in A549 cells compared with the control group after 24 h of BA treatment and upregulated in non-treated CSCs after 48 h. In various studies, Vimentin has been shown to regulate EMT, which affects multiple physiological and pathological processes such as growth and wound healing. Vimentin has also been confirmed to be closely related to the formation and development of tumors by modulating EMT (Bronte et al. 2019; Zhang et al. 2019; Chen et al. 2021).

Collagen, the main component of type I collagen, is widely distributed throughout the body because it is located in the interstitium of the parenchymal organs and connective tissues (Simon et al. 2001). Due to its importance in tissue development and homeostasis, excessive collagen accumulation in ECM can lead to various diseases. In cancer biology, collagen regulates the physical and biochemical properties of the neoplastic microenvironment. Thus, it regulates cancer cells’ polarity, migration, and signaling. In our study, COL1A1 expression was upregulated in A549 cells but downregulated in LC-SCs compared with the control group after 24 h of BA treatment. After 48 h, COL1A1 expression was upregulated in A549 cells and LC-SCs. Different expressions of COL1A1 have been observed in many types of cancer. High levels of COL1A1 expression are associated with increased cell proliferation, invasion, metastasis, and drug resistance. These observations suggest that COL1A1 may become a novel prognostic cancer marker. However, COL1A1 expression levels and potential mechanisms differ between types of cancers (Li et al. 2022). To our observations, 50 mM 24 h of BA treatment could be more beneficial as it reduces the expression of COL1A1 in cancer stem cells.

Laminins are a family of cell adhesion glycoproteins that can combine into αβγ trimers, which are the main components of basement membranes. They play an essential role in signal transduction to maintain the function of both healthy and tumor cells (Maltseva et al. 2020). In addition, they play crucial roles in certain stages of the metastasis process. In many tumor types, expression levels of laminin chains are of prognostic importance. For example, in the case of colorectal cancer, an increase in the rate of expression levels of genes encoding the α4 and α5 laminin chains has been associated with a poor prognosis (Galatenko et al. 2018). In the present study, LAMA5 expression was upregulated after 48 h of BA treatment. Changes in the expression profile of laminin chains are also observed during EMT in various types of cancer. LAMA5 has been identified as an essential promoter in liver metastasis, and tumor-derived LAMA5 inhibition has been shown to reduce branching in angiogenesis with increased Notch signaling in the tumor endothelium (Gordon-Weeks et al. 2019). Upregulation of LAMA5 in cancer and cancer stem cells after 48 h of BA treatment could impair metastatic growth and increase the expression of Notch signal pathway genes. This data demonstrates a mechanism whereby induced LAMA5 expression in lung cancer and cancer stem cells.

In our study, there were differences between some immunohistochemical results and qRT-PCR results. The differences in qRT-PCR and immunohistochemistry are likely due in part to varying sampling methods and actual biological differences (Pascal et al. 2008). While transcriptional responses in physiological and pathological processes are measured by RT-qPCR analysis, the presence or localization of relevant molecules in the tissue is determined by immunocytochemical analyses. Differences observed between RT-qPCR and immunocytochemical analyses may be due to the transcription step. Some molecules, such as miRNAs, could regulate genes’ expression post-transcriptionally. We also know that epigenetic mechanism has severe cancer prevention and detection implications. The roles of boric acid on EMT in cancer and cancer stem cells are not yet known. There is also a relationship between morphological characteristics and EMT. Boric acid partially affects cell morphology and may affect epithelial and mesenchymal features of cells. Therefore, it may be more appropriate to administer a chemotherapeutic drug used in lung cancer and boric acid in combination therapy. To fully understand this, we must approach it using single-cell analyses, whole-exon sequencing, whole-genome sequencing, methylation chromatin analyses, and RNA sequencing approaches. Investigating detailed mechanisms with advanced molecular techniques will help us identify potential therapeutic targets. The main aim of this study is to examine how BA, which we are frequently exposed to in our daily diet, affects the metastatic properties of LC-CSCs and present data on the dosage or combined therapy to be selected at the clinical level, along with the in vivo study planned for subsequent analysis. In this context, the results of our research are pioneering and provide valuable data on the targeting and regulation of cancer stem cell therapy.

As a result, we investigated the effects of BA on the epithelial-mesenchymal transition of lung cancer stem cells derived from human NSCLC, A549, by gene expression levels, migration analysis, and immunohistochemical parameters. It was observed that boric acid slightly reduced the migration of cancer cells.

Conclusion

Moreover, while E-cadherin and Collagen-1 immunoreactivities significantly increased, MMP-3 and Vimentin immunoreactivities decreased in BA-treated LC-CSCs. Although BA causes significant changes in some EMT-related genes and protein expressions, it can slightly affect migration in LC-SCs at applied doses and times. Little is known about the relationship between lung cancer and EMT. A thorough understanding of the role of LC-SCs in lung cancer progression will benefit the use of more effective strategies for targeted therapy and agents for antitumor treatment. According to the results of our literature research, this is the first study to investigate the effect of BA on the epithelial-mesenchymal transition of lung cancer stem cells derived from human NSCLC, A549. We think the present results will be an incentive for and provide new insights into future studies about BA’s effect on lung cancer stem cells.

Author contribution

Conceived designed the research: Tuğba Semerci Sevimli. Designed the experiments and contributed data or analysis tools: Tuğba Semerci Sevimli, Aynaz Ghorbani, Emilia Qomi Ekenel, Zarifa Ahmadova, Bahar Demir Cevizlidere, Burcugül Altuğ, Tuğba Ertem, and Özlem Tomsuk. Performed the analysis: Fatih Çemrek. Collected the data: Aynaz Ghorbani, Emilia Qomi Ekenel, Zarifa Ahmadova, Bahar Demir Cevizlidere, and Burcugül Altuğ. Performed the literature review: Varol Şahintürk, Onur Uysal, Sibel Güneş Bağış, and Hüseyin Avci. Wrote the manuscript: Tuğba Semerci Sevimli and Murat Sevimli. All authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript. The authors declare that all data were generated in-house, and no paper mill was used.

Funding

Open access funding provided by the Scientific and Technological Research Council of Türkiye (TÜBİTAK). This study was supported by Eskişehir Osmangazi University Scientific Research Projects Coordination Unit (Grant number: 202046025). Author Tuğba Semerci Sevimli has received the support.

Data availability

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

Declarations

Ethics approval

This is an observational study. The Eskişehir Osmangazi University Research Ethics Committee has confirmed that no ethical approval is required.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

This article has been retracted. Please see the retraction notice for more detail: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00210-024-03613-7"

Change history

11/11/2024

This article has been retracted. Please see the Retraction Notice for more detail: 10.1007/s00210-024-03613-7

References

- Abughanimeh O, Kaur A, El Osta B, Ganti AK (2022) Novel targeted therapies for advanced non-small lung cancer. Semin Oncol 49(3–4):326–336 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ayama-Canden S, Tondo R, Piñeros L, Ninane N, Demazy C, Dieu M, Fattaccioli A, Tabarrant T, Lucas S, Bonifazi D (2022) IGDQ motogenic peptide gradient induces directional cell migration through integrin (αv) β3 activation in MDA-MB-231 metastatic breast cancer cells. Neoplasia 31:100816 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Babaei G, Vostakolaei MA, Bazl MR, Aziz SG-G, Gholipour E, Nejati-Koshki K (2022) The role of exosomes in the molecular mechanisms of metastasis: focusing on EMT and cancer stem cells. Life Sci 310:121103. 10.1016/j.lfs.2022.121103 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Bade BC, Dela Cruz CS (2020) Lung cancer 2020: epidemiology, etiology, and prevention. Clin Chest Med 41(1):1–24 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barranco WT, Eckhert CD (2004) Boric acid inhibits human prostate cancer cell proliferation. Cancer Lett 216(1):21–29 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bronte G, Puccetti M, Crinò L, Bravaccini S (2019) Epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition and EGFR status in NSCLC: the role of vimentin expression. Ann Oncol 30(2):339–340 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Césaire M, Montanari J, Curcio H, Lerouge D, Gervais R, Demontrond P, Balosso J, Chevalier F (2022) Radioresistance of non-small cell lung cancers and therapeutic perspectives. Cancers 14(12):2829 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang K-W, Zhang X, Lin S-C, Lin Y-C, Li C-H, Akhrymuk I, Lin S-H, Lin C-C (2021) Atractylodin suppresses TGF-β-mediated epithelial-mesenchymal transition in alveolar epithelial cells and attenuates bleomycin-induced pulmonary fibrosis in mice. Int J Mol Sci 22(20):11152 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Z, Fang Z, Ma J (2021) Regulatory mechanisms and clinical significance of vimentin in breast cancer. Biomed Pharmacother 133:111068 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng F, Shen Y, Mohanasundaram P, Lindström M, Ivaska J, Ny T, Eriksson JE (2016) Vimentin coordinates fibroblast proliferation and keratinocyte differentiation in wound healing via TGF-β–slug signaling. Proc Natl Acad Sci 113(30):E4320–E4327 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cho ES, Kang HE, Kim NH, Yook JI (2019) Therapeutic implications of cancer epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT). Arch Pharmacal Res 42:14–24 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Das BC, Nandwana NK, Das S, Nandwana V, Shareef MA, Das Y, Saito M, Weiss LM, Almaguel F, Hosmane NS (2022) Boron chemicals in drug discovery and development: synthesis and medicinal perspective. Molecules 27(9):2615 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dongre A, Weinberg RA (2019) New insights into the mechanisms of epithelial-mesenchymal transition and implications for cancer. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 20(2):69–84 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duruisseaux M, Esteller M (2018) Lung cancer epigenetics: from knowledge to applications. Semin Cancer Biol 51:116–128 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galatenko VV, Maltseva DV, Galatenko AV, Rodin S, Tonevitsky AG (2018) Cumulative prognostic power of laminin genes in colorectal cancer. BMC Med Genomics 11(1):77–81 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gong C, Yang Z, Wu F, Han L, Liu Y, Gong W (2016) miR-17 inhibits ovarian cancer cell peritoneal metastasis by targeting ITGA5 and ITGB1. Oncol Rep 36(4):2177–2183 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gordon-Weeks A, Lim SY, Yuzhalin A, Lucotti S, Vermeer JAF, Jones K, Chen J, Muschel RJ (2019) Tumour-derived laminin α5 (LAMA5) promotes colorectal liver metastasis growth, branching angiogenesis and notch pathway inhibition. Cancers 11(5):630 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hacioglu C, Kar F, Davran F, Tuncer C (2023) Borax regulates iron chaperone-and autophagy-mediated ferroptosis pathway in glioblastoma cells. Environ Toxicol 38(7):1690–1701 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herpel E, Jensen K, Muley T, Warth A, Schnabel PA, Meister M, Herth FJ, Dienemann H, Thomas M, Gottschling S (2011) The cancer stem cell antigens CD133, BCRP1/ABCG2 and CD117/c-KIT are not associated with prognosis in resected early-stage non-small cell lung cancer. Anti-Cancer Res 31(12):4491–4500 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ichikawa MK, Endo K, Itoh Y, Osada AH, Kimura Y, Ueki K, Yoshizawa K, Miyazawa K, Saitoh M (2022) Ets family proteins regulate the EMT transcription factors snail and ZEB in cancer cells. FEBS Open Bio 12(7):1353–1364 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imran SA, Yazid MD, Idrus RBH, Maarof M, Nordin A, Razali RA, Lokanathan Y (2021) Is there an interconnection between epithelial–mesenchymal transition (EMT) and telomere shortening in aging? Int J Mol Sci 22(8):3888 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jinesh GG, Brohl AS (2022) Classical epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) and alternative cell death process-driven blebbishield metastatic-witch (BMW) pathways to cancer metastasis. Signal Transduct Target Ther 7(1):1–17 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kahm YJ, Kim RK, Jung U, Kim IG (2021) Epithelial membrane protein 3 regulates lung cancer stem cells via the TGF-β signaling pathway. Int J Oncol 59(4):80 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Celebı D, Celebı O, Aydin E, Baser S, GülerMC Yildirim S, Taghizadehghalehjoughi A (2024) Boron Compound-Based Treatments Against Multidrug-Resistant Bacterial Infections in Lung Cancer In Vitro Model. Biol Trace Elem Res 202(1):145–160 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kahraman E, Göker E (2022) Boric acid exert anti-cancer effect in poorly differentiated hepatocellular carcinoma cells via inhibition of AKT signaling pathway. J Trace Elem Med Biol 73:127043 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang Y, Massagué J (2004) Epithelial-mesenchymal transitions: twist in development and metastasis. Cell 118(3):277–279 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerpel-Fronius A, Tammemägi M, Cavic M, Henschke C, Jiang L, Kazerooni E, Lee CT, Ventura L, Yang D, Lam S, Huber RM, members of the Diagnostics Working Group, ED and Screening Committee (2022) Screening for Lung Cancer in Individuals Who Never Smoked: An International Association for the Study of Lung Cancer Early Detection and Screening Committee Report. J Thorac Oncol 17(1):56–66 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Li X, Sun X, Kan C, Chen B, Qu N, Hou N, Liu Y, Han F (2022) COL1A1: a novel oncogenic gene and therapeutic target in malignancies. Pathol-Res Pract 236:154013 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Loh C-Y, Chai JY, Tang TF, Wong WF, Sethi G, Shanmugam MK, Chong PP, Looi CY (2019) The E-cadherin and N-cadherin switch in epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition: signaling, therapeutic implications, and challenges. Cells 8(10):1118 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahabir S, Spitz M, Barrera S, Dong Y, Eastham C, Forman M (2008) Dietary boron and hormone replacement therapy as risk factors for lung cancer in women. Am J Epidemiol 167(9):1070–1080 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahmood MQ, Ward C, Muller HK, Sohal SS, Walters EH (2017) Epithelial mesenchymal transition (EMT) and non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC): a mutual association with airway disease. Med Oncol 34(3):45 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maltseva D, Raygorodskaya M, Knyazev E, Zgoda V, Tikhonova O, Zaidi S, Nikulin S, Baranova A, Turchinovich A, Rodin S (2020) Knockdown of the α5 laminin chain affects differentiation of colorectal cancer cells and their sensitivity to chemotherapy. Biochimie 174:107–116 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Messner K, Vuong B, Tranmer GK (2022) The boron advantage: the evolution and diversification of boron’s applications in medicinal chemistry. Pharmaceuticals 15(3):264 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Najafi M, Mortezaee K, Majidpoor J (2019) Cancer stem cell (CSC) resistance drivers. Life Sci 234:116781 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nedunchezhian K, Aswath N, Thiruppathy M, Thirugnanamurthy S (2016) Boron neutron capture therapy-a literature review. J Clin Diagn Res: JCDR 10(12):ZE01 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osada AH, Endo K, Kimura Y, Sakamoto K, Nakamura R, Sakamoto K, Ueki K, Yoshizawa K, Miyazawa K, Saitoh M (2019) Addiction of mesenchymal phenotypes on the FGF/FGFR axis in oral squamous cell carcinoma cells. PLoS ONE 14(11):e0217451 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pascal LE, True LD, Campbell DS, Deutsch EW, Risk M, Coleman IM, Eichner LJ, Nelson PS, Liu AY (2008) Correlation of mRNA and protein levels: cell type-specific gene expression of cluster designation antigens in the prostate. BMC Genom 9(1):1–13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peuhu E, Virtakoivu R, Mai A, Wärri A, Ivaska J (2017) Epithelial vimentin plays a functional role in mammary gland development. Development 144(22):4103–4113 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pijuan J, Barceló C, Moreno DF, Maiques O, Sisó P, Marti RM, Macià A, Panosa A (2019) In vitro cell migration, invasion, and adhesion assays: from cell imaging to data analysis. Front Cell Dev Biol 7:107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prasetyanti PR, Medema JP (2017) Intra-tumor heterogeneity from a cancer stem cell perspective. Mol Cancer 16(1):1–9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qin L, Chen X, Wu Y, Feng Z, He T, Wang L, Liao L, Xu J (2011) Steroid receptor coactivator-1 upregulates integrin α5 expression to promote breast cancer cell adhesion and migrationSRC-1 enhances ITGA5 expression and cancer metastasis. Can Res 71(5):1742–1751 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raniszewska A, Vroman H, Dumoulin D, Cornelissen R, Aerts J, Domagała-Kulawik J (2021) PD-L1+ lung cancer stem cells modify the metastatic lymph-node immunomicroenvironment in nsclc patients. Cancer Immunol Immunother 70(2):453–461 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ribatti D, Tamma R, Annese T (2020) Epithelial-mesenchymal transition in cancer: a historical overview. Transl Oncol 13(6):100773 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seguin L, Desgrosellier JS, Weis SM, Cheresh DA (2015) Integrins and cancer: regulators of cancer stemness, metastasis, and drug resistance. Trends Cell Biol 25(4):234–240 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sevimli M, Bayram D, Özgöçmen M, Armağan I, SemerciSevimli T (2022) Boric acid suppresses cell proliferation by TNF signaling pathway mediated apoptosis in SW-480 human colon cancer line. J Trace Elem Med Biol 71:126958 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simon M-P, Maire G, Pedeutour F (2001) COL1A1 (collagen, type I, alpha 1). Atlas Genet Cytogenet Oncol Haematol 5:78–82 [Google Scholar]

- Suarez-Arnedo A, Figueroa FT, Clavijo C, Arbeláez P, Cruz JC, Muñoz-Camargo C (2020) An image J plugin for the high throughput image analysis of in vitro scratch wound healing assays. PLoS ONE 15(7):e0232565 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turkez H, Arslan ME, Tatar A, Mardinoglu A (2021) Promising potential of boron compounds against glioblastoma: in vitro antioxidant, anti-inflammatory and anti-cancer studies. Neurochem Int 149:105137 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walcher L, Kistenmacher A-K, Suo H, Kitte R, Dluczek S, Strauß A, Blaudszun A-R, Yevsa T, Fricke S, Kossatz-Boehlert U (2020) Cancer stem cells—origins and biomarkers: perspectives for targeted personalized therapies. Front Immunol 11:1280 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu S, Zhang H, Wang A, Ma Y, Gan Y, Li G (2020) Silibinin suppresses epithelial-mesenchymal transition in human non-small cell lung cancer cells by restraining RHBDD1. Cell Mol Biol Lett 25:36 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- Yu M, Chu S, Fei B, Fang X, Liu Z (2019) O-GlcNAcylation of ITGA5 facilitates the occurrence and development of colorectal cancer. Exp Cell Res 382(2):111464 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang H, Wu X, Xiao Y, Wu L, Peng Y, Tang W, Liu G, Sun Y, Wang J, Zhu H (2019) Coexpression of FOXK1 and vimentin promotes EMT, migration, and invasion in gastric cancer cells. J Mol Med 97:163–176 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zou K, Li Z, Zhang Y, Mu L, Chen M, Wang R, Deng W, Zou L, Liu J (2021) β-Elemene enhances radiosensitivity in non-small-cell lung cancer by inhibiting epithelial–mesenchymal transition and cancer stem cell traits via Prx-1/NF-kB/iNOS signaling pathway. Aging (albany NY) 13(2):2575 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.