Abstract

Abstract

The Streptomyces sp. is considered the vast reservoir of bioactive natural products belonging to different classes like polyketides, terpenoids, lanthipeptides, and non-ribosomal peptides to name a few. The ubiquitous distribution of the genus makes them capable of producing distinct compounds. Many of those compounds contain a unique γ-pyrone with various chemical structures and exhibit different bioactivities. One such class, nitrophenyl-γ-pyrone, constitutes different bioactive compounds isolated from Streptomyces sp. from different sources ranging from soil to marine environments. In addition, such compounds have antinematodal, cytotoxicity activities, and inhibition of adipogenesis. These compounds include aureothin (3), spectinabilin (7), and their derivatives. Moreover, there are other compounds like actinopyrones (11–16), benwamycins (22–23), and peucemycin and its derivatives (24–26) that also have antibacterial and anticancer activities. The other group classified as anthra-γ-pyrone has various bioactive natural products. For instance, tetrahydroanthra-γ-pyrone, shellmycin A-D (27–30) possess antibacterial as well as anticancer activities. In addition, the pluramycin family compounds belonging to anthra-γ-pyrone group also possess cytotoxic activity, for instance, kidamycin (31), rubiflavin, and their derivatives (33–37). Xanthones are another important group of natural products that also contain γ-pyrone ring producing different bioactivities. Albofungin (42) and its derivatives (43–46) belong to subgroup polycyclic tetrahydro xanthones that possess antibacterial, anticancer, and antibiofilm, antimacrofouling activities. Similarly, other compounds, belonging to this subgroup, exhibit different bioactivities like antifungal, antimalarial, and antibacterial activities and block transient receptor potential vanilloid 1 (TRPV1). These compounds include cervinomycins (48–55), citreamycins (56–57), sattahipmycin (59), and chrexanthomycins (60–63). This review gives succinct information on the γ-pyrone containing natural products isolated from Streptomyces sp. focusing on their structure and bioactivities.

Key points

• The Streptomyces sp. is the producer of various bioactive natural products including the one with γ-pyrone ring.

• These γ-pyrone compounds are structurally different and possess different bioactivities.

• The Streptomyces has the potential to produce such compounds and the reservoir of these compounds is expected to increase in the future.

Keywords: Streptomyces, γ-Pyrone, Nitrophenyl-γ-pyrone, Anthra-γ-pyrone, Pluramycin

Introduction

The phylum Actinomycetota (or Actinobacteria) has 374 genera with Streptomyces being the largest (Donald et al. 2022). The genus Streptomyces is a Gram-positive bacteria with a high GC content of 69–78%, filamentous, aerobic, non-motile, and produces mycelia that branch abundantly, while aerial hyphae differentiate into spores with various colors white, yellow, red, and violet to blue (Sharma et al. 2016).

The Streptomyces produce a variety of natural products with distinct structures and functions that have potential applications, such as antibacterial, antifungal, anticancer, and immunosuppressive (Donald et al. 2022; Alam et al. 2022). It is interesting to note that a single Streptomyces species can produce a wide range of biologically active metabolites. For example, Streptomyces hygroscopicus can produce about 180 metabolites with different bioactivities (Alam et al. 2022).

Various natural products have pyrone in their structure and impart distinct biological activities. The pyrone is a class of six-membered oxygen heterocycle that exists in two structural isomers, 2 pyrone (α-pyrone) (1) and 4-pyrone (γ-pyrone) (2) (Fig. 1) (Bhat et al. 2017). The natural products with these pyrone rings are widely distributed in all three kingdoms of life and have various biological activities (Busch and Hertweck 2009; Bhat et al. 2017). The first isomer, α-pyrone, is abundantly found in various natural products and produces an extensive range of biological activities ranging from antifungal, antimicrobial, HIV-protease inhibitor, and neurotoxic effects (Dobler et al. 2021). The second isomer, the γ-pyrone ring, is also found in various natural products constituting a large class of biologically active compounds and many of them have been isolated from various organisms including several microorganisms (Wilk et al. 2009). Most of them were isolated from marine organisms and its associated bacteria (Wilk et al. 2009). These compounds are found to be pharmacologically active and hence regarded as one of the important secondary metabolites. All of these compounds belong to polyketides, a large group of secondary metabolites that are synthesized by the activities of a group of enzymes called polyketide synthases (PKSs) (Risdian et al. 2019). Furthermore, these PKSs are divided into three different types (type I, type II, and type III) and produce polyketides with diverse structures (Risdian et al. 2019). The isolation of such compounds from Streptomyces with various sources makes the genus a suitable target for further research. There are no any succinct information regarding these compounds and their biological activities to date focusing on the Streptomyces sources.

Fig. 1.

Structural isomer of pyrone

This review summarizes the natural products with γ-pyrone ring isolated from Streptomyces sp. with their biological activities dated from 2019 until date. It provides succinct information on the structure and biological activities of such compounds including anthra-γ-pyrone, and xanthones as excluding a few other groups to meet the scope of this minireview.

γ-Pyrone compounds

Several natural products with γ-pyrone rings have been isolated from Streptomyces species. They are structurally diverse and have different bioactivities. These compounds have different chemical groups attached to the γ-pyrone ring. Some are found to have alkyl groups, furan ring, and benzyl groups attached to the γ-pyrone ring. As a result, this leads to a variety of compounds that, in turn, display various bioactivities. These compounds are divided into different classes based on these substituents.

γ-Pyrone not fused with benzene ring

These types of compounds do not have γ-pyrones fused with the benzene ring (Fig. 2). Instead, several other groups are linked to the γ-pyrone at different carbon positions. Hence, these compounds are classified into several groups based on the substituents attached to the γ-pyrone.

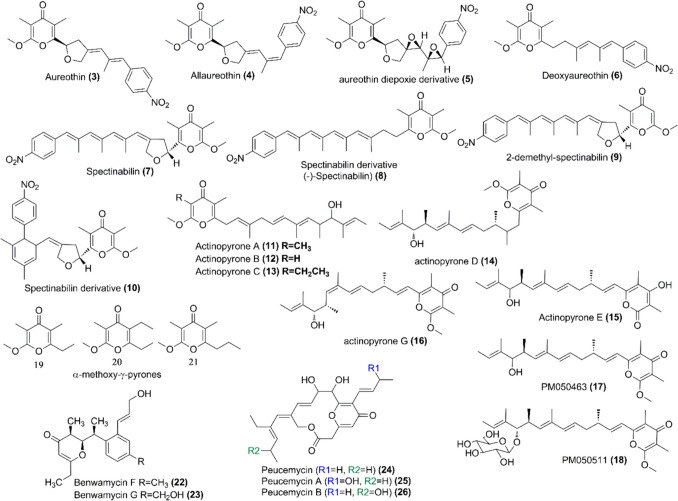

Fig. 2.

The chemical structure of natural products having γ-pyrone ring that is not attached to other benzene

Nitrophenyl-γ-pyrones

These γ-pyrones contain a nitrophenyl moiety with few exceptions (Wilk et al. 2009). Aureothin (3) is one of the members of this class that was first isolated from Streptomyces thioluteus (Hirata et al. 1961). This compound later has been isolated from several other Streptomyces species as well (Kang et al. 2022). An endophytic bacterium Streptomyces sp. AE170020 isolated from a pine tree root sample was found to produce compound 3 as well as alloaureothin (4) (Fig. 2 and Table 1) (Kang et al. 2022). Both of these compounds showed antinematode activity against Bursaphelenchus xylophilus; the growth, reproduction, and behavior of the nematodes were suppressed (Kang et al. 2022). A novel aureothin diepoxide derivative (5) was identified from Streptomyces sp. NIIST-D31 isolated from soil samples of the Western Ghats forest of Malampuzha of Palakkad district, Kerala (Fig. 2) (Drissya et al. 2022). The compound 5 had an antiadipogenesis effect and inhibited the accumulation of lipid droplets during the differentiation of 3T3-L1 cells (Table 1) (Drissya et al. 2022). Similarly, the compounds 3, 4, and deoxyaureothin (6) were also isolated from Streptomyces distallicus and their larvicidal activity against Aedes aegypti showed an interesting result (Fig. 2 and Table 1) (Kim et al. 2022). The compounds 3 and 4 demonstrated larvicidal activity with LC50 values of 1.5 and 3.1 ppm for 24 h post-treatment, respectively, and 3.8 and 7.4 ppm for 48 h post-treatment, respectively (Table 1), while the compound 6, a furan ring reduced form of the compound 3, did not show any activity (Kim et al. 2022).

Table 1.

List of natural products having a γ-pyrone ring that is not attached to other benzene

| Natural products | Biological activities | Sources | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nitrophenyl-γ-pyrones | |||

| Aureothin (3), alloaureothin (4) | Antinematodal activity against Bursaphelenchus xylophilus |

Endophytic bacteria Streptomyces sp. AE170020 |

(Kang et al. 2022) |

| Alloaureothin vicinal diepoxide (5) | Inhibition of adipogenesis and accumulation of lipid droplets during the differentiation of 3T3-L1 cells | Streptomyces sp. NIIST-D31 from soil samples of Western Ghats Forest of Malampuzha of Palakkad district, Kerala | (Drissya et al. 2022) |

| Aureothin (3), allo-aureothin (4), deoxyaureothin (6) | Larvicidal activity against Aedes aegypti with LC50 values of 1.5 and 3.1 ppm for aureothin and allo-aureothin, for 24 h post-treatment respectively | Streptomyces distallicus | (Kim et al. 2022) |

| Spectinabilin (7) | Antinematodal activity against Bursaphelenchus xylophilus with an LC50 value of 0.84 g mL−1 | Streptomyces sp. AN091965 from Korean forest soil samples | (Liu et al. 2019) |

| Spectinabilin (7), spectinabilin derivative (8), and a new analog, 2- demethyl-spectinabilin (9) | Spectinabilin has cytotoxicity against five human cancer cell lines, with IC50 values ranging from 18.7 ± 3.1 to34.6 ± 4.7 μM while the remaining compounds have weak cytotoxic activities | Soil-borne Streptomyces spectabilis strain | (Gao et al. 2019) |

| Spectinabilin derivative (10) and (-)-Spectinabilin) (8) | Streptomyces sp. S012 from rhizosphere soil of Nanjing Zhongshan Botanical Garden | (Zhang et al. 2020) | |

| Spectinabilin (7) | Nematicidal activity on Caenorhabditis elegans and Meloidogyne incognita. 100% lethality at 10 μg mL−1 concentration for C. elegans while 40% lethality at 100 μg mL−1 for M. incognita | Streptomyces sp. DT10 isolated from Wild moss | (Sun et al. 2023) |

| Actinopyrones | |||

| Actinopyrone A (11) | Antifungal activity against Ganoderma boninense | Oil palm rhizosphere-associated Streptomyces palmae CMU-AB204T |

(Sujarit et al. 2020a) (Sujarit et al. 2020b) |

| Actinopyrones D (14), Actinopyrone E (15), Actinopyrone G (16), PM050463 (17), PM050511 (18) | Cytotoxicity against human cancer cell lines with the PM050511 as the most potent | Deep-sea hydrothermal-vent-derived Streptomyces sp. SCSIO ZS0520 | (Zhang et al. 2022) |

| α-Methoxy-γ-pyrones | |||

| 2-Methoxy-3-methyl-5,6-diethyl-γ-pyrone (19), 2-methoxy-3,5- dimethyl-6-propyl- γ- Pyrone (20), 2-methoxy-3,5-dimethyl-6-ethyl-γ-pyrone (21) | Mangrove sediment-derived Streptomyces psammoticus SCSIO NS126 | (Li et al. 2021) | |

| Trialky substituted benzene with gamma pyrone | |||

| Benwamycins F (22), G (23) | Benwamycin F inhibits human T cell proliferation | Soil-derived Streptomyces sp. KIB-H1471 | (Yang et al. 2020) |

| Macrolides with γ-pyrones | |||

| Peucemycin (24), Peucemycin A (25) Peucemycin B (26) | Antibacterial and weak anticancer activities | Streptomyces peucetius ATCC 27952 |

(Pham et al. 2021) (Magar et al. 2023) (Magar et al. 2024) |

Spectinabilin (7) is another compound belonging to this group, which was first isolated from Streptomyces spectabilis (Fig. 2) (Kakinuma et al. 1976). The compound 7 was also isolated from Streptomyces sp. AN091965 collected from Korean forest soil sample and showed nematicidal activity against B. xylophilus, with an LC50 value of 0.84 g mL−1 (Table 2). In addition, the concentration of compound 7 at 0.9 mg per tree effectively suppressed the development of pine wilt diseases in 5-year-old Pinus densiflora trees (Liu et al. 2019). Spectinabilin derivative (8) and a new analog, 2-demethyl spectinabilin (9) along with the compound 7 were isolated from soil-borne Streptomyces spectabilis strain and evaluated their antiproliferative effect on hepatocellular carcinoma cells (Fig. 2 and Table 1) (Gao et al. 2019). The compound 7 exhibited cytotoxicity towards five human cancer cell lines. The IC50 values for 7 range from 18.7 ± 3.1 to 34.6 ± 4.7 μM; on the other hand, the remaining two compounds (8, 9) had weak cytotoxic activities (Gao et al. 2019). Streptomyces sp. S012 isolated from the rhizosphere soil of Nanjing Zhongshan Botanical Garden was found to produce the spectinabilin derivative (10) and a (-)-Spectinabilin (8) (Fig. 2 and Table 1) (Zhang et al. 2020). The compound 7 was also identified from newly isolated Streptomyces sp. DT10 from a wild moss sample and evaluated its nematicidal activity against Caenorhabditis elegens and southern root-knot nematode Meloidogyne incognita (Sun et al. 2023). The compound 7 exhibited nematicidal activity against both of these nematodes. The half-maximal inhibitory concentration (IC50) is 2.948 μg mL−1 for C. elegans L1 worms and the compound also significantly reduced the locomotive ability of C. elegans L4 worms at 40 μg mL−1 (Sun et al. 2023).

Table 2.

List of natural products belonging to anthra-γ-pyrone

| Natural products | Biological activities | Sources | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Tetrahydroanthra-γ-pyrone | |||

| Shellmycin A–D (27–30) |

Moderate antibacterial activity towards Bacillus subtilis, Staphylococcus aureus, and Enterococcus faecalis Cytotoxic activity towards various cancer cell lines with shellmycin C being the least potent |

Marine Streptomyces sp. Shell-016 from the Binzhou shell dike island | (Han et al. 2020) |

| Pluramycin family compounds | |||

| Kidamycin (31), photokidamycin (32), rubiflavinone C-1 (33), rubiflavin E (34), rubiflavin G (35), photorubiflavin G (36), photorubiflavin E (37) |

Kidamycin, photokidamycin, and photorubiflavin G showed cytotoxicity towards two human breast cancer cell lines–MCF7 and MDAMB-231 The most potent photokidamycin inhibited MCF7 and MDA-MB-231 cell growth (IC50 = 3.51 and 0.66 μM, respectively) |

Streptomyces sp. W2061from soil sample collected at Daejeon, Republic of Korea | (Lee et al. 2023) |

| Epoxykidamycinone (38), saptomycin (39), kidamycinone (40), kidamycin derivative (41) | Streptomyces sp. W2061from soil sample collected at Daejeon, Republic of Korea | (Heo et al. 2022) |

Actinopyrones

The structurally related actinopyrones, actinopyrone A (11), B (12), and C (13), were first isolated from Streptomyces pactum S12538 in 1986 by Yano and co-workers (Fig. 2) (Yano et al. 1986). These compounds as well as other derivatives were also isolated from several other Streptomyces species. The compound 11 was isolated from oil palm rhizosphere–associated Streptomyces palmae CMU-AB204T and the compound showed antifungal activity against Ganoderma boninense which is the causative agent of basal stem rot (BSR), or Ganoderma rot disease in oil palm plant of Southeast Asian countries (Table 1) (Sujarit et al. 2020a). Similarly, Sujarit and co-workers studied S. palmae CMU-AB204T as a biocontrol agent for the protection of palm trees from the fungus, G. boninense, and found that the compound 11 was present to control the fungus with the compound showed inhibitory activity at 50 μg disk−1 (Sujarit et al. 2020b). Zhang and co-workers recently isolated new actinopyrone derivatives, actinopyrones E (15), and G (16) along with other previously identified ones actinopyrone D (14), PM050463 (17), PM050511 (18) from deep-sea hydrothermal vent-derived Streptomyces sp. SCSIO ZS0520 (Fig. 2) (Zhang et al. 2022). Among the compounds tested as the potential anticancer, compound 18 was found to have cytotoxicity against six human cell lines with IC50 values of 0.26–2.22 μM (Table 1) (Zhang et al. 2022).

α-Methoxy-γ-pyrones

The structurally simplest γ-pyrones were isolated from mangrove sediment-derived actinomycete strain Streptomyces psammoticus SCSIO NS126 and include two new α-methoxy-γ-pyrone analogs, 2-methoxy-3-methyl-5,6-diethyl-γ-pyrone (19) and 2-methoxy-3,5-dimethyl-6-propyl-γ-pyrone (20), together with 2-methoxy-3,5-dimethyl-6-ethyl-γ-pyrone (21) (Fig. 2 and Table 1) (Li et al. 2021). They were isolated from the ethylacetate fraction of the culture media grown in optimized fermentation conditions. They were tested for the acetylcholinesterase activity, but unfortunately, did now show any activity (Li et al. 2021).

Trialky substituted benzene with γ-pyrones

The group of compounds with trialkyl-substituted benzene named benwamycin has been isolated from soil-derived Streptomyces sp. KIB-H1471 and among them, two of the benwamycins were found to have γ-pyrone ring, benwamycin F (22) and G (23) (Fig. 2) (Yang et al. 2020). The compound 22 inhibited human T cell proliferation with IC50 values of 12.5 μM and did not show any cytotoxicity to naïve human T cells (Table 1). In addition, the compound is expected to weakly enhance insulin-stimulated glucose uptake (Yang et al. 2020).

Macrolide with γ-pyrone

Peucemycin (24) is a macrolide with an unusual 14-membered macrocyclic γ-pyrone ring isolated from Streptomyces peucetius ATCC 27952 (Fig. 2 and Table 1) (Pham et al. 2021). Recently, our group identified two new peucemycin derivatives, peucemycin A (25-hydroxy peucemycin) (25) and peucemycin B (19-hydroxy peucemycin) (26) from S. peucetius ATCC 27952 (Fig. 2 and Table 1) (Magar et al. 2023, 2024). These compounds showed antibacterial activity towards various Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria with poor anticancer activity (Pham et al. 2021; Magar et al. 2023, 2024). They are synthesized by the type I polyketide synthase (PKS) genes and the biosynthetic gene cluster (BGC) responsible for the formation of these compounds is identified as Peu BGC (Magar et al. 2023). The Peu BGC is considered to be cryptic BGC because these compounds are not produced at the normal bacterial culture condition; instead, they are produced by decreasing the temperature of the culture condition (Pham et al. 2021; Magar et al. 2023, 2024).

Anthra-γ-pyrone

These types of compounds contain anthraquinone-γ-pyrone core structure. Based on the modification of the core structure, several compounds belonging to this class have been identified.

Tetrahydroanthra-γ-pyrone

Han and co-workers isolated four novel bioactive tetrahydroanthra-γ-pyrone compounds named shellmycin A-D (27–30) (Fig. 3 and Table 2) (Han et al. 2020). They identified their structures and tested their biological activities. All of the identified compounds showed moderate antimicrobial activity towards Bacillus subtilis, Staphylococcus aureus, and Enterococcus faecalis (Han et al. 2020). Similarly, all of the compounds exhibited the cytotoxicity towards the five cancer cell lines with IC50 value from 0.69 to 26.3 μM, and among them, the compound 29 had the least activity (Table 2) (Han et al. 2020).

Fig. 3.

Chemical structure of shellmycins

Pluramycin family compounds

The pluramycin is structurally characterized as having γ-pyrone angucycline backbone with two aminoglycosides linked by a carbon–carbon bond (Lee et al. 2023). Several compounds belonging to the pluramycin family were isolated from Streptomyces species. One of them is kidamycin (31) which was previously isolated from the Streptomyces species (Kanda 1971). Lee and co-workers identified different pluramycin derivatives from the same Streptomyces sp. W2061 including kidamycin (31), photokidamycin (32), rubiflavinone C-1 (33), rubiflavin E (34), rubiflavin G (35), photorubiflavin G (36), photorubiflavin E (37), and studied their cytotoxic activity towards various cancer cell lines (Fig. 4 and Table 2) (Lee et al. 2023). The newly identified compound 36 was compared with compounds 31 and 32 for cytotoxicity activity against the two human breast cancer cell lines and found that MDA-MB-231 cells were more sensitive than the MCF7 cells. Similarly, compounds 31 and 32 have higher cytotoxic effects with the latter having IC50 values of 3.51 and 0.66 μM for MCF7 and MDA-MB-231 cells respectively (Table 2) (Lee et al. 2023).

Fig. 4.

Chemical structure of pluramycin family compounds with γ-pyrone

During the elucidation of the biosynthetic pathway of the compound 31from Streptomyces sp. W2061 which was isolated from a soil sample collected at Daejeon, Republic of Korea, several kidamycin derivatives, and intermediates were isolated and identified their structure by Heo and co-workers (Fig. 4 and Table 2) (Heo et al. 2022). These include epoxykidamycinone (38), saptomycin (39), kidamycinone (40), and new kidamycin derivative (41) (Fig. 4 and Table 2).

Xanthone-derived natural products

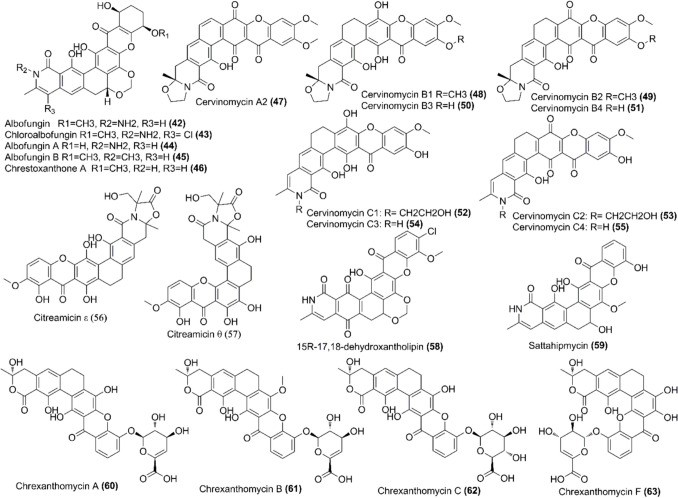

Xanthones are structurally characterized as γ-pyrone ring fused with two benzene rings. Polycyclic tetrahydro xanthones are one of the types of xanthones that include albofungin (42), chloroalbofungin (43), and related compounds (Fig. 5). The compound 42 was first isolated from Actinomyces tumemacerans (Fukushima et al. 1973), and since then, the compound 42 and its related compounds have been isolated from various Streptomyces species. Ye and co-workers determined the absolute structure of compounds 42 and 43 after isolating them from Streptomyces chrestomyceticus BCC 24770, crystalizing them, and performing the X-ray diffraction (Fig. 5 and Table 3) (Ye et al. 2020). She and co-workers identified two novel derivatives of 42, albofungin A (44) and B (45) along with compounds 42 and 43 that were previously identified (Fig. 5) (Table 3) (She et al. 2021). They also evaluated the biological activities of these compounds and found to be active against Gram-positive bacteria and have anticancer activity towards various cancer cells by inducing cellular apoptosis (She et al. 2021). Other derivatives of 42, chrestoxanthone A (46), and the compound 43 were later isolated from S. chrestomyceticus BCC 24770 and their antibiofilm and antimacrofouling activities were evaluated (Fig. 5 and Table 3) (She et al. 2022). These albofungins showed antibiofilm and antimacrofouling activities suggesting the potential application in marine environments where marine biofouling causes huge economic losses in marine industries (She et al. 2022).

Fig. 5.

Chemical structure of polycyclic tetrahydro xanthones

Table 3.

List of natural products with xanthone ring

| Natural products | Biological activities | Sources | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Polycyclic tetrahydro xanthones | |||

| Albofungin (42), chloroalbofungin (43) | Streptomyces chrestomyceticus BCC 24770 | (Ye et al. 2020) | |

| Albofungins A (44) and B (45), albofungin (42), chloroalbofungin (43) | Antibacterial activity against some Gram-positive bacteria and antitumor activities towards various cancer cell lines | Streptomyces chrestomyceticus BCC 24770 | (She et al. 2021) |

| Albofungin A (44), chrestoxanthone A (46), chloroalbofungin (43) | Antibiofilm and antimacrofouling activities | Streptomyces chrestomyceticus BCC 24770 | (She et al. 2022) |

| Cervinomycins A2 (47), cervinomycins B1–4 (48–51) | Anticancer and antibacterial activity towards Gram-positive bacteria | Streptomyces CPCC 204980, a soil isolate | (Hu et al. 2019) |

| Cervinomycins C1–4 (52–55) | Cytotoxicity against human cancer cell lines HCT116 and BxPC-3 and antibacterial activity towards Gram-positive bacteria | Streptomyces CPCC 204980, a soil isolate | (Hu et al. 2020) |

| Citreamicin ε and θ (56–57) | Antifungal activity against phytopathogenic fungi with citreamicin ε being the most potent, MIC values ranging from 1.56 to 12.5 mM | Streptomyces caelestis Aw99c isolated from the Red Sea | (Zhao et al. 2019) |

| 15R-17,18-dehydroxantholipin (58) | Antimicrobial and antiproliferative activities | Mangrove Streptomyces qinglanensis 172205 | (Xu et al. 2020) |

| Sattahipmycin (59) | Antibacterial, antimalarial, antibiofilm, and cytotoxicity towards some cancer cell lines | Marine-derived Streptomyces sp. GKU 257–1 | (Leetanasaksakul et al. 2022) |

| Chrexanthomycin A (cA) (60), chrexanthomycin B (cB) (61), chrexanthomycin C (cC) (62) | Binding to G-quadruplex (G4) forming C9orf 72 GGGGCC (G4C2) expanded hexanucleotide repeat (EHR) predominant in genetic diseases amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) and frontotemporal dementia (FTD) | Streptomyces chrestomyceticus BCC 24770 | (Cheng et al. 2022) |

| Chrexanthomycin F (cF) (63) | Transient receptor potential vanilloid 1 (TRPV1) blocker, suppressed capsaicin induced pain sensation in mice | Streptomyces chrestomyceticus BCC 24770 | (Ye et al. 2023) |

| Monomeric xanthones | |||

| Monacyclione G (64) | Marine-derived Streptomyces sp. HDN15129 | (Chang et al. 2020) | |

| Huanglongmycin E and F (65–66) | Cave-derived Streptomyces sp. CB09001 | (Jiang et al. 2022) |

Cervinomycins are other important xanthone-derived natural products that exhibit various biological activities. Cervinomycins A2 (47) and Cervinomycins B1 − 4 (48–51) were isolated from Streptomyces CPCC 204980, a soil isolate, and demonstrated that the later four compounds had cytotoxicity as well as antibacterial activity against Gram-positive bacteria (Fig. 5 and Table 3) (Hu et al. 2019). Hu and co-workers later isolated another cervinomycins, cervinomycins C1-4 (52–55) that showed strong cytotoxicity against human cancer cell lines HCT116 and BxPC-3 with IC50 value of 0.9–801.0 nm and had antibacterial activity towards Gram-positive bacteria (Hu et al. 2020).

Two more xanthones citreamicin ε (56) and θ (57) were identified from the culture extract of Streptomyces caelestis Aw99c isolated from the Red Sea (Fig. 5 and Table 3) (Zhao et al. 2019). The compound 56 was more potent in inhibiting the growth of phytopathogenic fungi than 57 and carbendazin (control) with MIC values ranging from 1.56 to 12.5 μM (Zhao et al. 2019). Xu and co-workers isolated another xanthone-derived secondary metabolite from mangrove Streptomyces ginglanensis 172205 that had strong antimicrobial and antiproliferative activities (Fig. 5 and Table 3) (Xu et al. 2020). The compound was 15R-17,18-dehydroxantholipin (58) and showed antimicrobial activities against S. aureus and Candida albicans with MIC (minimum inhibitory concentration) values of 0.78 µg mL−1 and 3.13 µg mL−1, respectively (Xu et al. 2020). Similarly, the compound exhibited strong cytotoxic activities against human breast cancer cell line MCF-7 and human cervical cancer cell line HeLa with IC50 values of 5.78 µM and 6.25 µM, respectively (Xu et al. 2020).

A new polycyclic xanthone, sattahipmycin (59), was identified from marine-derived Streptomyces sp. GKU 257–1 that showed strong biological activities (Fig. 5 and Table 3) (Leetanasaksakul et al. 2022). The compound showed antibacterial activity against several Gram-positive bacteria but did not show any activity against Gram-negative bacteria. Likewise, the compound showed significant antimalarial activity towards chloroquine-resistance and sensitive Plasmodium falciparum when compared with artemisinin and chloroquine antimalarial drugs with MIC values of 0.27 and 0.20 μM respectively (Leetanasaksakul et al. 2022). Moreover, the compound exhibited the antibiofilm activity showing the inhibition of 50% biofilm formation of E. coli at 15–60 μg mL−1 (Leetanasaksakul et al. 2022). Besides these activities, the compound also produced the cytotoxicity to human cervical cancer cell line (HeLa S3), human colorectal adenocarcinoma cell line (HT29), human adenocarcinoma cell line derived from lung cancer (A549), human non-small-cell lung-carcinoma cell line (H1299), and human cell line derived from pancreatic cancer (PANC-1) with IC50 values of 2.18, 1.90, 1.86, 10.64, and 12.89 μM, respectively (Leetanasaksakul et al. 2022).

The albofungin-producing S. chrestomyceticus BCC 24770 also produces several other xanthones. The chrexanthomycins are a few of them that have diverse biological functions. Cheng and co-workers isolated three compounds, chrexanthomycin A (cA) (60), chrexanthomycin B (cB) (61), chrexanthomycin C (cC) (62) from S. chrestomyceticus and tested the potential of these compounds as therapeutic agent in treating amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) and frontotemporal dementia (FTD) (Fig. 5 and Table 3) (Cheng et al. 2022). These compounds were found to bind the G-quadruplex (G4) forming C9orf 72 GGGGCC (G4C2) expanded hexanucleotide repeat (EHR) that are predominant in these genetic diseases. The compounds 60 and 62 significantly reduced G4C2 EHR-caused cell death and eliminated ROS in HT22 cells. Similarly, compounds 60 and 62 significantly rescued eye degeneration and improved locomotor deficits in (G4C2)29-expressing Drosophila (Cheng et al. 2022). Another chrexanthomycin named chrexanthomycin F (cF) (63) was isolated by Ye and co-workers and this compound along with the previously identified one was found as the transient receptor potential vanilloid 1 (TRPV1) blocker and showed the therapeutic potential of these compounds in chronic pain management (Ye et al. 2023). The compounds 62 and 63 showed significant TRPV1 inhibitory effects. Furthermore, these compounds effectively suppressed capsaicin-induced pain sensation in mice when compared with capsazepine, a known TRPV1 channel blocker (Ye et al. 2023).

Monomeric xanthones

Chang and co-workers isolated several angucycline derivatives and other compounds from marine-derived Streptomyces sp. HDN15129 (Fig. 6 and Table 3) (Chang et al. 2020). One of these compounds, monacyclinone G (64), possesses the xanthone core linked to the aminodeoxysugar, ossamine (Fig. 6). The compound was tested for anticancer activity against different cancer cell lines, but it was found to be inactive with IC50 higher than 10 μM (Chang et al. 2020). Similarly, Jiang and co-workers identified two new monomeric xanthones huanglongmycin E (65) and F (66) from cave-derived Streptomyces sp. CB09001 (Fig. 6 and Table 3) (Jiang et al. 2022). The plausible biosynthetic mechanism involving type II huanglongmycin polyketide synthase for this xanthone huanglomycin as well as benzophenone huanglomycin was also proposed (Jiang et al. 2022).

Fig. 6.

Chemical structures of monomeric xanthones

Conclusions

The genus Streptomyces is the highest producer of bioactive natural products among the actinobacteria belonging to different classes (Alam et al. 2022). Similarly, there is always in need of new antibiotics to combat the antibiotic resistance produced by the use of previous antibiotics (Donald et al. 2022). In addition, there is a requirement for anticancer compounds and bioactive compounds that have pharmacological activities. For this, Streptomyces are always the best choice and are always capable of producing bioactive compounds.

The γ-pyrone containing natural products are one of the major natural products that are biologically active, for instance, compound 11 (antifungal activity) (Sujarit et al. 2020a, b), compound 3 (antinematodal activity) (Kang et al. 2022), and compounds 27–30 (cytotoxic activity) (Han et al. 2020). These findings suggested that Streptomyces is capable of producing bioactive natural products with a γ-pyrone ring. Likewise, the ubiquitous distribution of the genus also helps in producing those unique γ-pyrone compounds. The disparity in the bioactivity is the result of the difference in the structure of the compounds. Moreover, a single compound can have various bioactivities, for example, compound 7 has both antinematodal and cytotoxic activities (Liu et al. 2019; Gao et al. 2019).

In the future, more bioactive natural products are expected to be discovered as more Streptomyces species are being identified from various habitats. Furthermore, a considerable number of natural products having γ-pyrone rings and diverse bioactivities would be present among these compounds.

Author contribution

RTM conceived and wrote the manuscript. RTM collected materials for the literature survey. JKS conceived and supervised manuscript writing, helped in writing the manuscript, and edited the manuscript to the final version.

Funding

This work was supported by a grant from Sun Moon University, Republic of Korea.

Data availability

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.

Declarations

Ethical approval

This article does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- Alam K, Mazumder A, Sikdar S, Zhao YM, Hao J, Song C, Wang Y, Sarkar R, Islam S, Zhang Y, Li A (2022) Streptomyces: the biofactory of secondary metabolites. Front Microbiol 13:1–21. 10.3389/fmicb.2022.968053 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhat ZS, Rather MA, Maqbool M, Lah HU, Yousuf SK, Ahmad Z (2017) α-pyrones: small molecules with versatile structural diversity reflected in multiple pharmacological activities-an update. Biomed Pharmacother 91:265–277. 10.1016/j.biopha.2017.04.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Busch B, Hertweck C (2009) Evolution of metabolic diversity in polyketide-derived pyrones: using the non-colinear aureothin assembly line as a model system. Phytochemistry 70:1833–1840. 10.1016/j.phytochem.2009.05.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang Y, Xing L, Sun C, Liang S, Liu T, Zhang X, Zhu T, Pfeifer BA, Che Q, Zhang G, Li D (2020) Monacycliones G−K and ent-gephyromycin A, angucycline derivatives from the marine-derived Streptomyces sp. HDN15129. J Nat Prod 83:2749–2755. 10.1021/acs.jnatprod.0c00684 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng A, Liu C, Ye W, Huang D, She W, Liu X, Fung CP, Xu N, Suen MC, Ye W, Sung HHY, Williams ID, Zhu G, Qian PY (2022) Selective C9orf72 G-quadruplex-binding small molecules ameliorate pathological signatures of ALS/FTD models. J Med Chem 65:12825–12837. 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.2c00654 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dobler D, Leitner M, Moor N, Reiser O (2021) 2-Pyrone – a privileged heterocycle and widespread motif in nature. European J Org Chem 2021:6180–6205. 10.1002/ejoc.202101112 [Google Scholar]

- Donald L, Pipite A, Subramani R, Owen J, Keyzers RA, Taufa T (2022) Streptomyces: still the biggest producer of new natural secondary metabolites, a current perspective. Microbiol Res (Pavia) 13:418–465. 10.3390/microbiolres13030031 [Google Scholar]

- Drissya T, Induja DK, Poornima MS, Jesmina ARS, Prabha B, Saumini M, Suresh CH, Raghu KG, Kumar BSD, Lankalapalli RS (2022) A novel aureothin diepoxide derivative from Streptomyces sp. NIIST-D31 strain. J Antibiot (Tokyo) 75:491–497. 10.1038/s41429-022-00547-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fukushima K, Ishiwata K, Kuroda S, Arai T (1973) Identity of antibiotic P-42-1 elaborated by Actinomycestumemacerans with kanchanomycin and albofungin. J Antibiot 26:65–69. 10.7164/antibiotics.26.65 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao X, Yao H, Mu Y, Guan P, Li G, Lin B, Jiang Y, Han L, Huang X, Jiang C (2019) The antiproliferative effect of spectinabilins from Streptomycesspectabilis on hepatocellular carcinoma cells in vitro and in vivo. Bioorg Chem 93:103311. 10.1016/j.bioorg.2019.103311 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han Y, Wang Y, Yang Y, Chen H (2020) Shellmycin A-D, novel bioactive tetrahydroanthra- γ-pyrone antibiotics from marine Streptomyces sp. Shell-016. Mar Drugs 18:58. 10.3390/md18010058 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heo KT, Lee B, Jang JH, Hong YS (2022) Elucidation of the di-c-glycosylation steps during biosynthesis of the antitumor antibiotic, kidamycin. Front Bioeng Biotechnol 10:985696. 10.3389/fbioe.2022.985696 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirata Y, Nakata H, Yamada K, Okuhara K, Naito T (1961) The structure of aureothin, a nitro compound obtained from Streptomycesthioluteus. Tetrahedron 14:252–274. 10.1016/S0040-4020(01)92175-1 [Google Scholar]

- Hu X, Hu X, Hu X, Li S, Li L, Yu L, Liu H, You X, Wang Z, Li L, Yang B, Jiang B, Wu L (2019) Cytotoxic and antibacterial cervinomycins B1–4 from a Streptomyces species. J Nat Prod 82:2337–2342. 10.1021/acs.jnatprod.9b00198 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Hu X, Sun W, Li S, Li LL, Yu L, Liu H, You X, Jiang B, Wu L (2020) Cervinomycins C1–4 with cytotoxic and antibacterial activity from Streptomyces sp. CPCC 204980. J Antibiot (Tokyo) 73:812–817. 10.1038/s41429-020-0342-1 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Jiang L, Xiang J, Zhu S, Tang D, Gong B, Pu H, Duan Y, Huang Y (2022) Undescribed benzophenone and xanthones from cave-derived Streptomyces sp. CB09001. Nat Prod Res 36:1725–1733. 10.1080/14786419.2020.1813134 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kakinuma K, Hanson CA, Rinehart KL Jr (1976) Spectinabilin, a new nitro-containing metabolite isolated from Streptomycesspectabilis. Tetrahedron 32:217–222. 10.1016/0040-4020(76)87004-4

- Kanda N (1971) A new antitumor antibiotic, kidamycin. I. Isolation, purification and properties of kidamycin. J Antibiot (Tokyo) 24:599–606. 10.7164/antibiotics.24.599 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang MK, Kim JH, Liu MJ, Jin CZ, Park DJ, Kim J, Sung BH, Kim CJ, Son KH (2022) New discovery on the nematode activity of aureothin and alloaureothin isolated from endophytic bacteria Streptomyces sp. AE170020. Sci Rep 12:1–16. 10.1038/s41598-022-07879-w [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim SJ, Cantrell CL, Avula B, Chen J, Schrader KK, Santo SN, Ali A, Khan IA (2022) Streptomycesdistallicus, a potential microbial biolarvicide. J Agric Food Chem 70:11274–11280. 10.1021/acs.jafc.2c03537 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee B, Lee GE, Hwang GJ, Heo KT, Lee JK, Jang JP, Hwang BY, Jang JH, Cho YY, Hong YS (2023) Rubiflavin G, photorubiflavin G, and photorubiflavin E: novel pluramycin derivatives from Streptomyces sp. W2061 and their anticancer activity against breast cancer cells. J Antibiot (Tokyo) 76:585–591. 10.1038/s41429-023-00643-w [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leetanasaksakul K, Koomsiri W, Suga T, Matsuo H, Hokari R, Wattana-Amorn P, Takahashi YK, Shiomi K, Nakashima T, Inahashi Y, Thamchaipenet A (2022) Sattahipmycin, a hexacyclic xanthone produced by a marine-derived Streptomyces. J Nat Prod 85:1211–1217. 10.1021/acs.jnatprod.1c00870 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li K, Zhou M, Su Z, Yang X, Zhou X, Huang J, Tao H (2021) Two new α-methoxy-γ-pyrones from the mangrove sediment-derived Streptomycespsammoticus SCSIO NS126. Nat Prod Commun 16:1–4. 10.1177/1934578X211041420 [Google Scholar]

- Liu MJ, Hwang BS, Jin CZ, Li WJ, Park DJ, Seo ST, Kim CJ (2019) Screening, isolation and evaluation of a nematicidal compound from actinomycetes against the pine wood nematode, Bursaphelenchusxylophilus. Pest Manag Sci 75:1585–1593. 10.1002/ps.5272 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magar RT, Pham VTT, Poudel PB, Nguyen HT, Bridget AF, Sohng JK (2023) Biosynthetic pathway of peucemycin and identification of its derivative from Streptomycespeucetius. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 107:1217–1231. 10.1007/s00253-023-12385-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magar RT, Pham VTT, Poudel PB, Bridget AF, Sohng JK (2024) A new peucemycin derivative and impacts of peuR and bldA on peucemycin biosynthesis in Streptomycespeucetius. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 108:1–10. 10.1007/s00253-023-12923-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Pham VTT, Nguyen HT, Nguyen CT, Choi YS, Dhakal D, Kim TS, Jung HJ, Yamaguchi T, Sohng JK (2021) Identification and enhancing production of a novel macrolide compound in engineered Streptomycespeucetius. RSC Adv 11:3168–3173. 10.1039/d0ra06099b [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Risdian C, Mozef T, Wink J (2019) Biosynthesis of polyketides in Streptomyces. Microorganisms 7:124. 10.3390/microorganisms7050124 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Sharma TK, Mawlankar R, Sonalkar VV, Shinde VK, Zhan J, Li WJ, Rele MV, Dastager SG, Kumar LS (2016) Streptomyceslonarensis sp. nov., isolated from Lonar Lake, a meteorite salt water lake in India. Antonie Van Leeuwenhoek 109:225–235. 10.1007/s10482-015-0626-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- She W, Ye W, Cheng A, Liu X, Tang J, Lan Y, Chen F, Qian PY (2021) Discovery, bioactivity evaluation, biosynthetic gene cluster identification, and heterologous expression of novel albofungin derivatives. Front Microbiol 12:635268. 10.3389/fmicb.2021.635268 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- She W, Ye W, Cheng A, Ye W, Ma C, Wang R, Cheng J, Liu X, Yuan Y, Chik SY, Limlingan Malit JJ, Lu Y, Chen F, Qian PY (2022) Discovery, yield improvement, and application in marine coatings of potent antifouling compounds albofungins targeting multiple fouling organisms. Front Microbiol 13:1–14. 10.3389/fmicb.2022.906345 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sujarit K, Mori M, Dobashi K, Shiomi K, Pathom-Aree W, Lumyong S (2020a) New antimicrobial phenyl alkenoic acids isolated from an oil palm rhizosphere-associated actinomycete, Streptomycespalmae CMU-AB204T. Microorganisms 8:1–15. 10.3390/microorganisms8030350 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sujarit K, Pathom-aree W, Mori M, Dobashi K, Shiomi K, Lumyong S (2020b) Streptomycespalmae CMU-AB204T, an antifungal producing-actinomycete, as a potential biocontrol agent to protect palm oil producing trees from basal stem rot disease fungus, Ganodermaboninense. Biol Control 148:104307. 10.1016/j.biocontrol.2020.104307 [Google Scholar]

- Sun Y, Xie J, Tang L, Odiba AS, Chen Y, Fang W, Wu X, Wang B (2023) Isolation, identification and molecular mechanism analysis of the nematicidal compound spectinabilin from newly isolated Streptomyces sp. DT10. Molecules 28:4365. 10.3390/molecules28114365 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilk W, Waldmann H, Kaiser M (2009) γ-Pyrone natural products-a privileged compound class provided by nature. Bioorganic Med Chem 17:2304–2309. 10.1016/j.bmc.2008.11.001 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Xu D, Tian E, Kong F, Hong K (2020) Bioactive molecules from mangrove Streptomycesqinglanensis 172205. Mar Drugs 18:1–11. 10.3390/md18050255 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang FX, Huang JP, Liu Z, Wang Z, Yang J, Tang J, Yu Z, Yan Y, Kai G, Huang SX (2020) Benwamycins A-G, trialkyl-substituted benzene derivatives from a soil-derived Streptomyces. J Nat Prod 83:111–117. 10.1021/acs.jnatprod.9b00903 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Yano K, Yokoi K, Sato J, Oono J, Kouda T, Ogawa Y, Nakashima T (1986) Actinopyrones A, B and C, new physiologically active substances II. Physico-chemical properties and chemical structures. J Antibiot (Tokyo) 39:38–43. 10.7164/antibiotics.39.38 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ye W, She W, Sung HHY, Qian P, Williams ID (2020) Albofungin and chloroalbofungin: antibiotic crystals with 2D but not 3D isostructurality. Acta Crystallogr Sect C Struct Chem 76:1100–1107. 10.1107/S2053229620015041 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ye W, Lui ST, Zhao Q, Wong YM, Cheng A, Sung HHY, Williams ID, Qian PY, Huang P (2023) Novel marine natural products as effective TRPV1 channel blockers. Int J Biol Macromol 253:127136. 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2023.127136 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Zhang Z, Zhang X, Kang Q, Lu C (2020) New spectinabilin and hexadienamide derivatives from Streptomyces sp. S012. Rec Nat Prod 14:312–318. 10.25135/rnp.173.19.12.1510 [Google Scholar]

- Zhang H, Zhang X, Yuan H, Wei Y, Xiaoyi J, Ju J (2022) Discovery, structure correction, and biosynthesis of actinopyrones, cytotoxic polyketides from the deep-sea hydrothermal vent-derived Streptomyces sp. SCSIO ZS0520 Huaran. J Nat Prod 85:625–633. 10.1021/acs.jnatprod.1c00901 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao JB, Liu LL, Liu HF, Gao HH, Yang ZZ, Feng XL, Gao JM (2019) Genome-based analysis of the type II PKS biosynthesis pathway of xanthones in: Streptomycescaelestis and their antifungal activity. RSC Adv 9:37376–37383. 10.1039/c9ra07345k [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.