Abstract

We show that gain-swept superradiance can be used to detect low (parts per million) concentrations of various gases at distances on the order of kilometers, which is done by using pulse timing to create small regions of gain at positions that sweep toward a detector. The technique is far more sensitive than previous methods such as light detection and ranging or differential absorption light detection and ranging.

The continuous monitoring of the atmosphere for traces of various gases and biopathogens at parts-per-million (ppm) concentrations and distances of the order of 1–10 km is a challenging problem, with applications from the control of environmental pollution to national security [e.g., the monitoring of nitric oxide (NO) and the warfare gas phosgene (COCl2)]. In the latter case, the LD50 (lethal dose for 50% for those exposed) is of the order of 10 ppm (1, 2). Continuous monitoring of the atmosphere for such gases at distances from 1 to 10 km would obviously be desirable and difficult. Beautiful measurements (3, 4) using light detection and ranging (LIDAR) techniques coupled with differential absorption LIDAR (DIAL) measurements have been reported and provide an important tool for the measurement of trace impurities in the atmosphere. However, to continuously scan the 2π sector of the sky covering a city, new schemes are needed. Stand-off superradiant (SOS) spectroscopy is such a scheme.

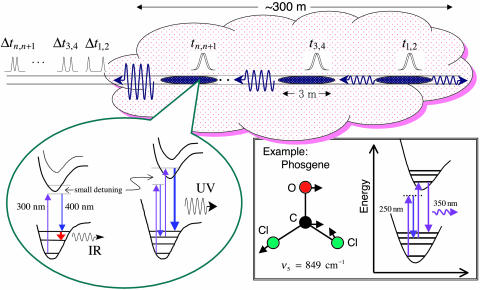

The detection scenario shown in Fig. 1 has two logical steps. In the first step, Raman or two-photon pumping of the gas molecules from the ground state to an appropriate excited state takes place. The excitation is achieved by simultaneous action of two synchronized picosecond laser pulses with a difference frequency that is resonant with the ground to vibrationally excited-state energy difference, or a sum frequency being resonant with the ground to electronically excited-state energy difference (5).

Fig. 1.

SOS spectroscopy. Multiple pairs of pulses are generated such that the spacing between pulses in each pair is decreasing. The second pulse in each pair has a higher velocity because of atmospheric dispersion. The first pair of pulses overlaps near the back of the cloud, creating a small region of gain. Subsequent pairs overlap at closer and closer regions of the cloud, producing a swept-gain amplifier that lases back toward the observer. We suggest two schemes: one in which blue and UV pulses are sent toward the cloud, causing lasing on an IR vibrational transition, and the other in which IR and UV pulses are sent toward the cloud, causing lasing on a blue electronic transition (such as the example shown in phosgene).

Then, in the second step, strong emission in the backward direction is generated by swept-gain superradiance (see refs. 6 and 7 and references therein). This generation ensures unidirectional high-gain propagation of the IR (Raman pumping) or UV (two-photon pumping) signal only within a narrow solid angle directed back along the exciting lasers, as shown in Fig. 1.

This scheme has the potential for real-time detection of poison gases (e.g., COCl2) and atmospheric pollutants (e.g., NO). Clouds in the size range of 1 m to 1 km can be addressed at distances from 10 m to 100 km and beyond. The essential advantage of this scheme is that the signal intensity exceeds the backscattering signal intensity of the usual LIDAR schemes by many orders of magnitude.

SOS spectroscopy has the main useful features of standard LIDAR systems, e.g. (i) long-range remote sensing, (ii) ranging by recording the time delay of the “radar” pulse return signal, (iii) monostatic (one location) operation with only “one” instrument on a mobile platform, and (iv) simplicity of alignment and pointing. Furthermore, the present “superradiant LIDAR” combines these advantages with several other significant advances, e.g. (i) many orders of magnitude increase in the magnitude of the detected signal and sensitivity, (ii) the possibility of real-time spectrally selective sensing, and (iii) the measurement of density distributions.

Thus, the principle of the present SOS spectroscopy is completely different from the well known DIAL technique and has significant advantages. In the following analysis, the application to such simple gases as mentioned earlier is presented.

Analysis

Let us first consider a subpicosecond ground-based (or airborne) laser system that emits pairs of picosecond visible pulses as shown in Fig. 1. There is a time delay Δtn,n+1 between the pulses in the nth pair. The first pulse in a pair is at a higher frequency (e.g., λ1 = 400 nm), and the second pulse is at a lower frequency (e.g., λ2 = 580 nm). The two pulses have different group velocities because of the dispersion of air. The delay time Δt12 between the first two pulses determines the distance z from the transmitter at which the faster-moving lower-frequency pulse catches up with the slower-moving higher-frequency pulse. Specifically, the group velocity in air depends on the frequency,

|

[1] |

Because of the dispersion of the refractive index of air (given by Cauchy's formula)

|

[2] |

the typical difference Δvg between the group velocities of the two pulses is a few kilometers per second, that is Δvg = vg (ω2) – vg(ω1) ∼ 4 × 105 cm/s for λ1 = 400 nm and λ2 = 580 nm.

Consider the nth pulse pair having an initial separation ΔLn = cΔtn,n+1. They will overlap after a time τn (when the faster pulse overtakes the slower pulse) defined by ΔLn = Δvgτn. The pulses are each moving at essentially the speed of light in vacuum so that the distance (from the sender) at which the overlap occurs is given by zn = cτn = cΔLn/Δvg. Hence, if we want the nth pair to overlap in the vicinity of zn, we should fix the separation to be Δtn,n+1 = Δvgzn/c2. For the case of λ1 = 400 nm and λ2 = 580 nm discussed above, Δtn,n+1 ≈ 50 ps for zn = 1 km.

Choosing a time delay Δt12 = zΔvg/c2, we can ensure that two pulses in a pair overlap each other at a particular location z in the target cloud, e.g. at z = 1kmfor Δt12 ∼ 50 ps. Because each pulse has a temporal duration of ∼1 ps, the spatial length of a pulse is of the order of ΔLpulse ∼ c × 1ps ∼ 3 × 10–2 cm, where c = 3 × 1010 cm/s is the velocity of light in vacuum. Hence, the two pulses are overlapping along the propagation path for a length of the order of ΔLoverlap = ΔLpulsec/Δvg ∼ 20 m. Over a portion, ΔLpump, of this overlap length the two pulses with properly chosen amplitudes will produce the desired stimulated Raman adiabatic passage (STIRAP) pumping of the vibrational transition or two-photon pumping of the UV electronic transition. (In particular, pump amplitudes are chosen so that their Rabi frequencies times the pulse duration is greater than π.) In such a case, counterintuitive passage (STIRAP) can be used. Under such conditions, a robust (≈100%) population inversion on the vibrational transition v = 4 → v = 3 or UV electronic transition as shown in Fig. 1 is possible. Note that ΔLpump is estimated as

|

[3] |

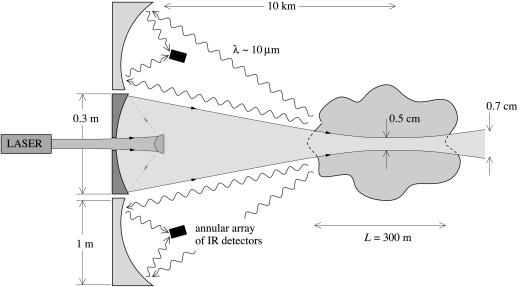

The relaxation time of the population inversion caused by collisions in the air is in the nanosecond range, T1 ∼ 1 ns. Therefore, as indicated in Fig. 1, each pair of visible pump pulses should follow the previous pair by the time Trep of order T1 ∼ 1 ns. In addition, we repeatedly decrease the delay time Δtn,n+1 between pulses in successive pairs by an amount TrepΔvg/c ∼ 0.01 ps. Because of this sequential decrease of the delay time between the two members of a given pulse pair Δtn,n+1, the gas along the LIDAR return path is pumped in neighboring segments that are successively closer to the receiver by approximately cTrep ∼ 0.3 m. With such a sequence of pairs of visible pump pulses (having Δtn,n+1 properly decreased in successive pairs), a long swept-gain amplifier of IR vibrational or UV electronic transition radiation in the warfare-gas cloud being interrogated is created. This amplifying region of excited gas molecules is a narrow cylinder of cross-sectional area As determined by the optics as illustrated in Fig. 2. This swept-gain configuration yields a beam of exponentially amplified spontaneous IR or UV radiation that is gain-guided in the backward direction. Note that the radiation from a particular vibrational transition, e.g., v = 4 → v = 3, is not reabsorbed by molecules in other vibrational states (e.g., v = 0 → v = 1) because of the anharmonicity of the molecular oscillator.

Fig. 2.

Schematic of the experimental apparatus.

Also, because the wavelength of the mid-IR radiation is of the order λ ∼ 10 μm, the radiation propagates with very little absorption because of the well known atmospheric transparency windows in the wavelength range from 3 to 5 μm and from 7 to 12 μm. Likewise, in the case of UV emission, the offset of the ground and electronic states allows for population inversion. Atmospheric propagation is possible without absorption in many applicable wavelength regions.

The regime of amplification in the long swept-gain amplifier described above depends on, among other things, the density of the pumped gas molecules N and the length L of the pumped region in the cloud. As discussed in refs. 6 and 7, the standard gain g is given by

|

[4] |

where T2 is the phase relaxation time (T2 < T1 ∼ 1 ns), γ0 is the radiative rate of decay from the upper to the lower operating state, ΔN is the density of the population difference of the warfare-gas molecules at the operating transition, ω0 = 2π c/λ0 and  are the frequency and dipole moment of this transition, respectively, and

are the frequency and dipole moment of this transition, respectively, and  is the cooperative frequency (as defined and discussed in ref. 6) that determines the rate of correlation of molecules through their interaction via exchange of emitted photons.

is the cooperative frequency (as defined and discussed in ref. 6) that determines the rate of correlation of molecules through their interaction via exchange of emitted photons.

Next, consider the population, ΔN, in the upper of the two levels, e.g., v = 4 in the IR case. At λ = 10 μm we may take the populations in the state v = 3 to be essentially zero. To easily transfer a substantial population from the v = 0 level into, say, the v = 4 level or the electronic excited state, we prefer to operate in single-photon resonance. As indicated in Fig. 1, the resonant Raman case involves replacing the visible radiation by UV. The associated resonant UV scheme of Fig. 1 operates by absorption of IR (v = 0 to v = 1) and UV (electronic ground to excited state), which occurs when the IR and UV pump pulses overlap. By tailoring the drive pulses properly, we can arrange to have a very substantial fraction of the v = 0 molecules brought into the excited state. This happens when  , where τ is the pulse duration ≈ 10–12 s. Thus, we require

, where τ is the pulse duration ≈ 10–12 s. Thus, we require  , implying an energy per pulse of

, implying an energy per pulse of

|

For example, if  Coulomb meter, the energy in each picosecond pulse is only a fraction of a millijoule.

Coulomb meter, the energy in each picosecond pulse is only a fraction of a millijoule.

Amplification Process

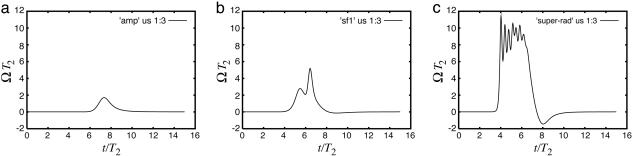

The evolution of the amplification process (see Fig. 3) of the backward mid-IR or UV signal is characterized by the following four different regimes.

Fig. 3.

Snapshots of the generated pulse at different positions in the cloud: at the far edge of the cloud where the pulse experiences linear amplification (a); in the middle of the cloud where the superfluorescent pulse is formed (b); and at the near edge of the cloud where the superradiant pulse is formed, where one can see that the time scale of the ringing is smaller than T2 (c). Parameters used in the simulation are:  , N = 1014 cm–3, and T2 = 10–9 s. Our estimate is that by using 60 laser pulses to transfer population to the excited vibrational state to create population inversion, one photon of spontaneous radiation at the far edge of the cloud will be amplified to 1016 photons leaving the near edge.

, N = 1014 cm–3, and T2 = 10–9 s. Our estimate is that by using 60 laser pulses to transfer population to the excited vibrational state to create population inversion, one photon of spontaneous radiation at the far edge of the cloud will be amplified to 1016 photons leaving the near edge.

Linear Amplification of Vacuum Fluctuations (or Thermal Radiation). In this regime the total gain along the whole gain-swept amplifier of a length L is small,  , where κ is the linear radiation losses in the amplifier caused by absorption, scattering, and diffraction out of the pumped cylindrical active region. The latter diffraction losses are determined by the cross-sectional area As as κdiff ∼ λ0/(3As). The variance of the Bloch angle at the operating transition characterizes the spontaneous or thermal noise, φ0 ∼ (NAs L)–1/2 ≪ 1, and is small, typically

, where κ is the linear radiation losses in the amplifier caused by absorption, scattering, and diffraction out of the pumped cylindrical active region. The latter diffraction losses are determined by the cross-sectional area As as κdiff ∼ λ0/(3As). The variance of the Bloch angle at the operating transition characterizes the spontaneous or thermal noise, φ0 ∼ (NAs L)–1/2 ≪ 1, and is small, typically  . The spatial profile of the average intensity of this amplified spontaneous (or thermal) luminescence along the gain-swept path in the cloud is a simple exponent,

. The spatial profile of the average intensity of this amplified spontaneous (or thermal) luminescence along the gain-swept path in the cloud is a simple exponent,

|

[5] |

and there is no any significant saturation of the population difference ΔN. In other words, the signal intensity, emitted from the cloud, is less than the saturation value:  . The pulse duration of the luminescence signal is of the order of τ ∼ τL = T1.

. The pulse duration of the luminescence signal is of the order of τ ∼ τL = T1.

Pulsed Superluminescence (Nonlinear Gain in Rate Equation Approximation). In this regime the gain is relatively large,  . The last inequality implies, however, that the cooperative time Tc = (α′c)–1/2 is still longer by a factor of

. The last inequality implies, however, that the cooperative time Tc = (α′c)–1/2 is still longer by a factor of  than the phase relaxation time on the operating transition,

than the phase relaxation time on the operating transition,  . The superluminescent-pulse duration again is determined by the relaxation time of the population inversion in the gain-swept amplifier, τ ∼ τSL ∼ T1. The intensity of the superluminescent pulse at the exit from the cloud is much larger than that of the spontaneous luminescence and is proportional to the number of pumped molecules,

. The superluminescent-pulse duration again is determined by the relaxation time of the population inversion in the gain-swept amplifier, τ ∼ τSL ∼ T1. The intensity of the superluminescent pulse at the exit from the cloud is much larger than that of the spontaneous luminescence and is proportional to the number of pumped molecules,

|

[6] |

The latter corresponds to the pulse energy that is of the order of half of the total pump energy stored at the operating transition in the warfare-gas molecules,

|

[7] |

if one would ignore losses. The spatial-temporal behavior of the superluminescent pulse traveling through the gain-swept amplifier can be described on the basis of the rate equations and is well studied (see, e.g., refs. 6–8 and references therein). It can be qualitatively inferred from the following simple equation for the field intensity of the signal

|

[8] |

which is valid in the case of relatively long pulses (τ ≫ T1) when the population difference is adiabatically saturated by the instantaneous value of the intensity, ΔN = N/(1 + I/Isat).

Superradiance (Superfluorescence). This coherent regime of the cooperative spontaneous (or thermal) emission occurs when the gain is very large,  so that the delay time of the development of superradiance (which in long-enough amplifiers is of the order of

so that the delay time of the development of superradiance (which in long-enough amplifiers is of the order of  ) is shorter than the population relaxation time, TD < T1. The superradiant regime provides a possibility to shorten the pulse duration below the relaxation time scale T2 and to increase further the maximal signal intensity. The linear-stage growth of the intensity of the superfluorescence from the noise level with the time t after pumping explicitly depends on the amplification length z, namely

) is shorter than the population relaxation time, TD < T1. The superradiant regime provides a possibility to shorten the pulse duration below the relaxation time scale T2 and to increase further the maximal signal intensity. The linear-stage growth of the intensity of the superfluorescence from the noise level with the time t after pumping explicitly depends on the amplification length z, namely

|

[9] |

The latter result and, in particular, the characteristic space-time profile of the superradiant pulse as a function of the combined variable  can be derived from the fact that one-dimensional Maxwell–Bloch equations for the complex slow-varying amplitudes of the field E and polarization P of the plane wave ∝ exp(–iω0t + iω0z/c) in the RWA approximation, namely

can be derived from the fact that one-dimensional Maxwell–Bloch equations for the complex slow-varying amplitudes of the field E and polarization P of the plane wave ∝ exp(–iω0t + iω0z/c) in the RWA approximation, namely

|

[10] |

|

[11] |

|

[12] |

have the modified Bessel functions I0(ζ′) and I1(ζ′) of the variable

|

[13] |

as the main part of their Green function at the linear stage of evolution, when ΔN = N = constant. Indeed, for the arbitrary initial profiles of the polarization P(z, t = 0) = P0(z)Θ(z) and field E (z, t = 0) = E0 (z)Θ(z) and arbitrary incident field E (z = 0, t) = Ein(t)Θ(t), we have from Eqs. 10 and 11 the following general solution (7) in the case of fixed population inversion ΔN = N = constant:

|

[14] |

|

|

Here Θ is the Heaviside step function and t̃ = t – z/c. It is straightforward to see from Eq. 14 that after a long-enough time the field and polarization on the linear stage of superradiance follow the similar asymptotic laws at all points of the active region, and these laws do not depend on the initial (smooth) profiles but only on the boundary value of the initial polarization P0(z = 0), namely

|

[15] |

The spatial-temporal dynamics of the amplitude of the molecular polarization  sin φ, the population inversion ΔN = N cos φ, and the amplitude of electric field

sin φ, the population inversion ΔN = N cos φ, and the amplitude of electric field  at the nonlinear stage of superradiance may be deduced from the one-dimensional sin-Gordon equation (equation 2.2 from ref. 6) that follows from Eqs. 10–12:

at the nonlinear stage of superradiance may be deduced from the one-dimensional sin-Gordon equation (equation 2.2 from ref. 6) that follows from Eqs. 10–12:

|

[16] |

|

[17] |

In the case of negligibly small linear losses, it can be described by a one-parameter family of its nonsingular self-similar solutions that obey the simple ordinary differential equation

|

[18] |

The superradiant pulse duration and delay time of its formation caused by the process of mutual correlations of warfare-gas molecules through the exchange by photons are inversely proportional to the square root of the warfare-gas density,

|

[19] |

|

[20] |

where  . The most imfeature of the superradiance is that the warfare-gas molecules tend to emit photons cooperatively as a collective, macroscopic coherent dipole in each causally related subvolume

. The most imfeature of the superradiance is that the warfare-gas molecules tend to emit photons cooperatively as a collective, macroscopic coherent dipole in each causally related subvolume  of the cooperative length

of the cooperative length  within the time durations shorter than the phase relaxation time, τSR < T2.

within the time durations shorter than the phase relaxation time, τSR < T2.

If one increases the gain further and pumps simultaneously very long active region,  , then each causally related subvolume Vc would emit its own superradiant pulse with the duration τSR so that the whole active region would emit a chaotic sequence of many (

, then each causally related subvolume Vc would emit its own superradiant pulse with the duration τSR so that the whole active region would emit a chaotic sequence of many ( ) such pulses with no additional increase of the peak intensity. However, we can overcome this unfavorable scenario by implementation of the gain-swept superradiance, as described below.

) such pulses with no additional increase of the peak intensity. However, we can overcome this unfavorable scenario by implementation of the gain-swept superradiance, as described below.

π -Pulse Production in a Long Swept-Gain Superradiant Amplifier. This gain-swept superradiant regime occurs when the gain is very large,  , and a coherent pulse is formed just behind the running front of pump pulses when the amplification length z is much larger than the cooperative length,

, and a coherent pulse is formed just behind the running front of pump pulses when the amplification length z is much larger than the cooperative length,  . In this case, the swept-gain amplifier produces a time-dependent pulse (7) of duration τπ ∝ 1/z, which is shorter than τSR (see Eq. 19). The field amplitude of the pulse grows linearly with the length of amplification, E ∝ z, and the pulse area tends to π,

. In this case, the swept-gain amplifier produces a time-dependent pulse (7) of duration τπ ∝ 1/z, which is shorter than τSR (see Eq. 19). The field amplitude of the pulse grows linearly with the length of amplification, E ∝ z, and the pulse area tends to π,

|

[21] |

This π-pulse takes up the entire energy stored in the pumped medium. Its asymptotic behavior is quasi-self-similar with the amplitude

|

[22] |

This solution is determined by the function φ(ζ) given by Eq. 18, in which for each value of the self-similar variable ζ there are two coordinates,

|

[23] |

that are related to two propagating fronts of population depletion. The population inversion ΔN first vanishes for  , i.e., in a time t0 = 2ζ0Lc at the point z0 = ζ0Lc, where z1 = z2. For t → ∞, one depletion front z(0)1 = z1(ζ = ζ0) approaches the beginning of the amplifier,

, i.e., in a time t0 = 2ζ0Lc at the point z0 = ζ0Lc, where z1 = z2. For t → ∞, one depletion front z(0)1 = z1(ζ = ζ0) approaches the beginning of the amplifier,  ; the second depletion front

; the second depletion front  follows the pumping front, z(0)2 ≈ ct. The former generates the self-similar superradiant pulse in a short sample,

follows the pumping front, z(0)2 ≈ ct. The former generates the self-similar superradiant pulse in a short sample,  , and the latter produces a time-dependent π -pulse in the long gain-swept superradiant amplifier.

, and the latter produces a time-dependent π -pulse in the long gain-swept superradiant amplifier.

The growth of this pulse is limited by radiation losses κ. If the gain is large enough, namely  , it results in the formation of a steady-state hyperbolic-secant superradiant pulse at large enough amplification length

, it results in the formation of a steady-state hyperbolic-secant superradiant pulse at large enough amplification length  . This pulse has a sech-shaped profile

. This pulse has a sech-shaped profile

|

[24] |

Its time duration is shorter than T2 and inversely proportional to the density of molecules

|

[25] |

as in equations 1.7 and 1.9 in ref. 6. The intensity grows as the square of the density of initially excited molecules N0 =ΔN (t = 0), i.e., Is ∝ N20.

If one compares these results against the case of uniform excitation, one sees that here there is no limitation on the power, whereas in the other case, the pulse width can be no shorter than the cooperation time Tc = (α′c)–1/2, and thus the peak power is also limited. In uniform excitation there is a limitation on a maximal range of cooperation  , which comes from requirement the that the atom must still be excited and avoid emission of photon until the pulse arrives. In a swept-gain amplifier, because atoms are excited only when the light coming from the proceeding ones reaches them, it is not necessary to impose a causal-related limit on the sample, i.e., the equivalent length of possible cooperation can be much larger than

, which comes from requirement the that the atom must still be excited and avoid emission of photon until the pulse arrives. In a swept-gain amplifier, because atoms are excited only when the light coming from the proceeding ones reaches them, it is not necessary to impose a causal-related limit on the sample, i.e., the equivalent length of possible cooperation can be much larger than  .

.

Estimates

Which amplification regime is realized depends first of all on the density N and size L of the warfare-gas cloud. For example, consider a typical vibrational transition with λ0 ∼ 10 μm, ω0 ∼ 2 × 1014 s–1,  , and T1,2 ∼ 1 ns. The values of the cooperative time and gain are then given by Eq. 4, where we assume ΔN ∼ N,

, and T1,2 ∼ 1 ns. The values of the cooperative time and gain are then given by Eq. 4, where we assume ΔN ∼ N,

|

[26] |

|

[27] |

Consider an extremely low density of the warfare gas, N ≤ 2 × 1014 cm–3 that is <10 ppm. Then, without a swept scheme, one has either amplified spontaneous emission [as discussed in Linear Amplification of Vacuum Fluctuations (or Thermal Radiation)] if the cloud size is small enough, L (cm) < 1017/N (cm–3) or pulsed superluminescence [as discussed in Pulsed Superluminescence (Nonlinear Gain in Rate Equation Approximation)] if L (cm) > 1017/N (cm–3). In this case, the gain can be already very large, e.g. e2gL ∼ e20 ≈ 109 for a cloud length L ∼ 10 m and a density N ∼ 2 × 1013 cm–3, i.e. 1 ppm.

Consider larger densities, N > 2 × 1014 cm–3, which still correspond to a very small fraction of the warfare gas in the air, only >10 ppm. Then the superradiance or π -pulse gain-swept coherent regime occurs with a huge gain gL ≫ 1 and extreme pulse shortening. For example, at a marginal density N ∼ 2 × 1014 cm–3 the superradiant pulse duration, τSR (s) ∼ 2 × 10–2 N–1/2 (cm–3), and the cooperative length, Lc (cm) ∼ 3 × 108 N–1/2 (cm–3), τSR ∼ 1 ns and Lc ∼ 10 cm, respectively, so that  m; at a density N ∼ 1015 cm–3, these become τSR ∼ 0.5 ns and Lc ∼ 5 cm, respectively. The peak coherent mid-IR power emitted toward the receiver by the superradiant pulse from even each subvolume of cooperative length,

m; at a density N ∼ 1015 cm–3, these become τSR ∼ 0.5 ns and Lc ∼ 5 cm, respectively. The peak coherent mid-IR power emitted toward the receiver by the superradiant pulse from even each subvolume of cooperative length,  , is very large: for a density N ∼ 2 × 1014 cm–3, it is

, is very large: for a density N ∼ 2 × 1014 cm–3, it is  W/cm2. This gain-collimated return signal propagates toward the receiver within the diffraction solid angle

W/cm2. This gain-collimated return signal propagates toward the receiver within the diffraction solid angle  and can be detected easily from distances of many kilometers.

and can be detected easily from distances of many kilometers.

In the regime of the π -pulse in the gain-swept superradiance, the intensity at the exit from the cloud is even larger by a factor depending on  . In a long-enough amplifier, when the steady-state π -pulse regime is formed, the intensity from the cloud reaches a peak value,

. In a long-enough amplifier, when the steady-state π -pulse regime is formed, the intensity from the cloud reaches a peak value,

|

[28] |

that is Is ∼ 40 MW/cm2 with a pulse duration τs = T2κ/g ∼ 20 ps for a density N ∼ 2 × 1014 cm–3 and diffraction losses κ = λ0/3As ∼ (500 cm)–1 in an amplifier of a diameter 0.5 cm (as shown in Fig. 2). In this case, the intensity at the receiver at a distance of 10 km from a cloud is of the order of 4 W/cm2, because the diffraction solid angle is ΔΩ ∼ λ20/As ∼ 4 × 10–6.

For example, the simulations shown in Fig. 3 predict the returning IR intensity at the near edge of the cloud to be of the order 106 W/cm2, with a pulse energy of 6 mJ (so that the number of photons returning is 3 × 1016).

To estimate the background noise from solar radiation scattered by haze, we assume horizontal observation and ∼30% of scattering from regular clouds, or ∼5 × 10–3 W·cm–2·steradian–1 in the visible region of spectrum (neglecting the Fraunhofer dark bands). This corresponds to ∼1016 photons per s per steradian per cm2 of observed scattering cross-sectional area. At 1 km, the solid angle for a 1-m diameter aperture is 10–6 steradian (although the presence of haze makes this rather uncertain). If we assume that the haze is colocated with the gas cloud, then the detector only observes that area that is illuminated by the laser, or ∼1 cm2, giving an unfiltered background of 1010 photons per s. Spectral filtering reduces this by ∼10–6 per GHz of bandwidth. The Raman signal may be broadened to several wavenumbers by rotational transitions; thus, we take the filter to be ∼100 GHz, reducing the background to 106 photons per s. Finally, we can use time gating to further reduce the background. For a 300-m cloud, the light travel time is 1 μs, resulting in a filtered and time-gated solar background of 1 photon per laser shot. (Note that the distance to the cloud is not a factor in the time gating.)

These estimates are better in the blue because of the reduced solar flux but worse because of the wavelength dependence of Rayleigh scattering and haze; however, this estimate suggests that the solar background from haze at 1 km cannot be removed to levels <1 photon per 1 μs time window. One of the advantages of stimulated Raman and IR is that gain narrowing collapses the spectrum, so a narrower spectral filter might be used.

Discussion

For comparison with the technique of SOS spectroscopy introduced in this article, we briefly review here state-of-the-art techniques for detection of atmospheric ozone by DIAL (3) and atmospheric water-vapor concentration by Raman LIDAR (4). The DIAL system developed by Walther and coworkers (3) for measurements of atmospheric ozone was based on the use of an injection-locked XeCl laser operating at 308 nm with a pulse energy of 150 mJ, a repetition rate of 50 Hz, and a line width of ∼1 cm–1. The 308-nm fundamental output of the XeCl laser is in the wing of a strong absorption band for ozone. A Raman-shifted Stokes beam at either 338 or 353 nm was generated in a Raman cell containing either methane or hydrogen, respectively. This Raman-shifted Stokes beam was not absorbed by ozone. Both the fundamental and Raman-shifted beams from the XeCl laser were expanded, collimated, and directed into the atmospheric region of interest. Backscattering from each beam caused by Rayleigh scattering was collected by using a 60-cm-diameter mirror, and the Rayleigh signals were measured by using a two-channel detection system with interference filters and three-stage Fabry–Perot filters for each wavelength. The ozone concentration was determined from the relative changes in the backscattered Rayleigh signals for the absorbed beam at 308 nm and the nonabsorbed beam at 338 or 353 nm. The quoted sensitivity of the system is 80 μg/m3, corresponding to 0.04 ppm, for a 5-hour measurement time.

Bisson et al. (4) describe a Raman LIDAR system based also on an injection-locked XeCl laser system. Their Raman LIDAR instrument was developed for both daytime and nighttime measurements of atmospheric water vapor. For the Raman measurements, detection channels for Rayleigh scattering at 308 nm, N2 Raman scattering at 331 nm, and H2O Raman scattering at 347 nm were used. For the daytime measurements, it was critical to reduce the number of background photons to the absolute minimum level, and the system incorporated specialized optics to restrict the field of view and specialized interference filters to block UV photons outside the Raman detection channel. The system was capable of water-vapor concentration measurements at altitudes up to 5 km with a spatial resolution of 75 m and a temporal resolution of 5 min. However, the sensitivity is not sufficient for the present purposes.

In conclusion, the SOS scheme is capable of detecting trace impurities at the parts-per-million level at kilometer distances.

Author contributions: V.K., S.C., K.L., R.L., R.M., Y.R., W.W., G.R.W., and M.O.S. performed research.

Abbreviations: LIDAR, light detection and ranging; DIAL, differential absorption LIDAR; SOS, stand-off superradiant.

References

- 1.Ellison, D. H. (2000) Handbook of Chemical and Biological Warfare Agents (CRC, Boca Raton, FL).

- 2.Clayton, G. D. & Clayton, F. E. (1982) Patty's Industrial Hygiene and Toxicology (Wiley, New York), Vol. 2C.

- 3.Steinbrecht, W., Rothe, K. W. & Walther, H. (1989) Appl. Opt. 28, 3616–3624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bisson, S. E., Goldsmith, J. E. M. & Mitchell, M. G. (1999) Appl. Opt. 38, 1841–1849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.DePristo, A., Rabitz, H. & Miles, R. (1980) J. Chem. Phys. 73, 4798–4806. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bonifacio, R., Hopf, F. A., Meystre, P. & Scully, M. O. (1975) Phys. Rev. A 12, 2568–2573. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zheleznyakov, V. V., Kocharovsky, V. V. & Kocharovsky, Vl. V. (1989) Sov. Phys. Usp. 32, 835–870. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sargent, M., III, Scully, M. O. & Lamb, W. E. (1974) Laser Physics (Addison–Wesley, Reading, MA).