Abstract

Aims

This study aimed to explore the causal relationships between cathepsins and cardiovascular diseases (CVDs) by Mendelian randomization (MR) analysis.

Methods and results

Single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) associated with nine cathepsin types (cathepsins B, E, F, G, H, O, S, L2, and Z) were obtained from the INTERVAL study (3301 individuals). CVDs data were acquired from the UK Biobank (coronary atherosclerosis: 14 334 cases, 346 860 controls) and a genome‐wide association study (GWAS) (myocardial infarction: 20 917 cases, 440 906 controls; myocarditis: 633 cases, 427 278 controls; chronic heart failure: 14 262 cases, 471 898 controls; angina pectoris: 30 025 cases, 440 906 controls; stable angina pectoris: 17 894 cases, 325 132 controls; unstable angina pectoris: 9481 cases, 446 987 controls; pericarditis: 1795 cases, 453 370 controls). Inverse variance weighted (IVW), MR‐Egger, weighted median methods were adopted to conduct univariable MR (UVMR), reverse MR, multivariable MR (MVMR) analyses to estimate causality. The UVMR analyses demonstrated significant causal relationships between higher cathepsin E levels and increased risk of coronary atherosclerosis [IVW: P = 0.0051, odds ratio (OR) = 1.0033, 95% confidence interval (CI) = 1.0010–1.0056] and myocardial infarction (IVW: P = 0.0097, OR = 1.0553, 95% CI = 1.0131–1.0993), while elevated cathepsin L2 levels were causally related to reduced risk of myocarditis (IVW: P = 0.0120, OR = 0.6895, 95% CI = 0.5158–0.9216) and chronic heart failure (IVW: P = 0.0134, OR = 0.9316, 95% CI = 0.8807–0.9854). Reverse MR analyses revealed that myocardial infarction increased cathepsin O levels (IVW: P = 0.0400, OR = 1.0708, 95% CI = 1.0031–1.1431). MVMR analyses treating nine cathepsins together revealed that the positive causality between cathepsin E levels and coronary atherosclerosis risk (IVW: P = 0.0390, OR = 1.0030, 95% CI = 1.0000–1.0060), and the protective effect of cathepsin L2 levels on myocarditis (IVW: P = 0.0030, OR = 0.6610, 95% CI = 0.5031–0.8676) and chronic heart failure (IVW: P = 0.0090, OR = 0.9259, 95% CI = 0.8737–0.9812) remained, as higher cathepsin O levels were found to be causally related to increased risks of myocarditis (IVW: P = 0.0030, OR = 1.6145, 95% CI = 1.1829–2.2034) and chronic heart failure (IVW: P = 0.0300, OR = 1.0779, 95% CI = 1.0070–1.1537).

Conclusions

The study highlights the causalities of cathepsin E, L2, and O on CVDs, offering insights into their roles in cardiovascular biomarkers and therapeutic targets development. Further research is required to apply these genetic findings clinically.

Keywords: Cathepsins, Cardiovascular diseases, Mendelian randomization, Genetic associations

Introduction

Cardiovascular diseases (CVDs) stand as the predominant cause of mortality worldwide, accounting for approximately one‐third of all mortality across the globe. 1 , 2 Representing a significant portion of this burden, heart failure affects approximately 64 million people worldwide. 3 These diseases not only lead to significant mortality but also contribute to disability and economic burden. Despite significant progress in diagnosis and treatment, the prevalence and mortality of cardiovascular events, including heart failure, have been on the rise, underscoring the need for further exploration into their underlying causes. 1 , 3

Cathepsins are a ubiquitously expressed group of lysosomal proteases characterized by an exceptionally wide range of functional roles. 4 Based on their molecular structures, they can be categorized into several families, including serine, aspartic, and cysteine cathepsins. 4 The significance of cathepsins in CVDs, particularly heart failure, is increasingly recognized due to their involvement in key pathophysiological mechanisms, such as extracellular matrix (ECM) remodelling and inducing inflammation. 5 , 6 Dysregulated cathepsins expression and activity can affect heart function by altering ECM balance and influencing immune responses. 7 Previous studies have predominantly focused on the role of cathepsins in atherosclerosis and coronary syndromes. 8 , 9 , 10 , 11 , 12 However, emerging evidence also suggests a significant impact of cathepsins on heart failure. Studies have shown elevated cathepsin levels in patients with chronic heart failure and a correlation between these levels and heart function. 13 , 14 , 15 These emerging insights into cathepsins' involvement in heart failure highlight their potential as therapeutic targets and biomarkers in cardiovascular management.

While prior studies have reported the relationship between cathepsins and CVDs, traditional observational studies often fall short of clearly establishing causality due to limitations like uncertainty in the time sequence of exposure factors and diseases, as well as selection and information biases. Mendelian randomization (MR) offers a more robust approach by utilizing single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) as genetic instrumental variables (IVs) to decipher a causal relationship between a particular trait and a specific disease outcome. The theory in MR analysis is that if these genetic variants are associated with the disease outcome through their effects on the exposure, then individuals carrying these variants should exhibit a higher likelihood of the disease. 16 Compared with observational studies, MR's strength lies in its ability to reduce confounding, as genetic variants, randomly allocated at conception, stay unchanged throughout life, avoiding the environmental or lifestyle factor biases often seen in observational studies. Additionally, this analysis effectively tackles reverse causality, as these genetic variants are unaffected by disease progression, thus clarifying the causality direction. 17 , 18 Furthermore, the advancement in genome‐wide association studies (GWASs) has significantly contributed to this methodology by identifying an abundance of genetic variants linked to complex diseases and traits, thereby expanding the pool of instrumental SNPs for more robust MR analyses. In this context, we conducted univariable, reverse, and multivariable MR analyses to examine the causal relationships of various cathepsin types on the risk of CVDs.

Materials and methods

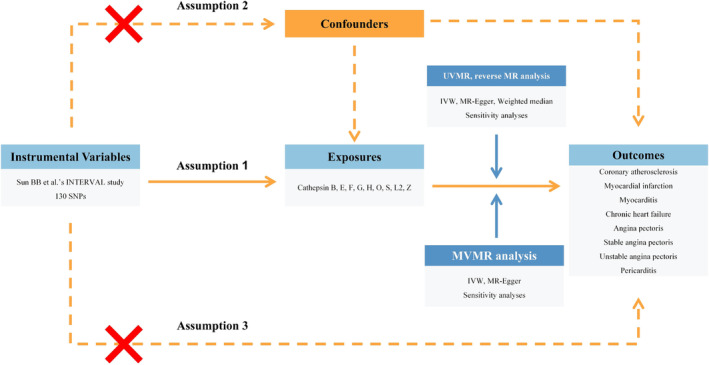

A detailed overview of the study design is shown in Figure 1 .

Fig. 1.

Flow chart of the entire study design. IVW, inverse variance weighted; MR, Mendelian randomization; MVMR, multivariable Mendelian randomization; SNP, single nucleotide polymorphism; UVMR, univariable Mendelian randomization.

Selection of instrumental variables for cathepsins

Summary data of diverse cathepsins adopted in this study were obtained from the INTERVAL study, including 3301 European. 19 Prior to their participation in the study, all individuals provided informed consent, and the study received approval from the National Research Ethics Service (11/EE/0538). The data source of cathepsins is displayed in Supporting information, Table S1 . The IVs selection process was grounded on three fundamental Mendelian assumptions. 20 , 21 (i) Genetic variants should exert a direct and statistically significant influence on exposure factors. (ii) Genetic variants should solely impact the outcomes through their effects on the exposures. (iii) Genetic variants should be strictly independent of any potential confounders. Our primary criteria for candidate SNPs screening as IVs were as follows: (i) P values less than the genome‐wide significant level of 5e‐6 proposed in the original study, which was aligned with the limitation of the sample size. (ii) A clump distance of less than 10 000 kb with r 2 < 0.001 to avoid potential linkage disequilibrium. To eliminate SNPs potentially influenced by confounding factors, we referred to each SNP in the PhenoScanner database to ensure that the selected instrumental genetic variants were independent of any potential confounders. 22 The data of SNPs selected as IVs are detailed in Table S2 .

Selection of instrumental variables for CVDs

In pursuit of conducting reverse MR analyses, we also acquired IVs for CVDs. In this study, a total of eight types of cardiovascular system diseases were regarded as outcomes. Other than the INTERVAL study, summary statistics of CVDs were derived from the UK Biobank and an independent study described as follows. Summary statistics of coronary atherosclerosis were acquired from a GWAS of the UK Biobank, involving 361 194 European individuals with 14 334 cases and 346 860 controls. Summary statistics of other cardiovascular disorders, including myocardial infarction (20 917 cases, 440 906 controls), myocarditis (633 cases, 427 278 controls), chronic heart failure (14 262 cases, 471 898 controls), overall angina pectoris (30 025 cases, 440 906 controls), stable angina pectoris (17 894 cases, 325 132 controls), unstable angina pectoris (9481 cases, 446 987 controls), and pericarditis (1795 cases, 453 370 controls), were extracted from a GWAS published by Sakaue et al. with the major study population of European descent. 23 Similarly, instrumental genetic variants for CVDs were reached through the steps mentioned above. The data sources of CVDs are displayed in Table S1 . All participants granted informed written consent, and all research endeavours underwent thorough review and approval by the institutional ethics review committees at the respective institutions involved. Phenotypes used in this study were available online at the Integrative Epidemiology Unit (IEU) OpenGWAS Project website (https://gwas.mrcieu.ac.uk).

Statistical analyses

We adopted diverse approaches to conduct univariable MR (UVMR) analyses, including inverse variance weighted (IVW), MR‐Egger, and weighted median. They produced different assumptions and dealt with pleiotropy effects by varied means. 24 , 25 , 26 Estimates of these methodologies were collectively taken into consideration to investigate the causalities of cathepsins and CVDs risk. Among them, the IVW method possessed the highest statistical power and was deemed the primary analytical approach to estimate the overall causal effects. 26 Although less efficient, the outcomes obtained from MR‐Egger and weighted median analyses were still valuable, as they provided crucial insights and contributed to a holistic assessment of the consistency and reliability of the results in our study. 27 From a statistical standpoint, a P value less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant. UVMR analyses were conducted using the ‘TwoSampleMR’ R package. 28 Following this, we implemented a series of sensitivity analyses to assess the potential influence of heterogeneous and pleiotropic effects on our estimates, ensuring the credibility and robustness of the study's results. The Cochran's Q test was carried out in order to assess and quantify potential heterogeneity in the estimates. 29 A P value below 0.05 signified the existence of heterogeneity, warranting the utilization of a random effects model. Instead, if the P value exceeded 0.05, a fixed effects model was deemed appropriate. 30 Meanwhile, we performed the MR‐Egger intercept test to identify potential horizontal pleiotropy. The p‐value of the intercept of MR‐Egger below 0.05 indicated the presence of pleiotropy. 31 MR Pleiotropy RESidual Sum and Outlier (MR‐PRESSO) test was employed to detect and thereby remove any outlier SNPs. 32 Leave‐one‐out test was also implemented to identify any SNPs that potentially exerted an extreme influence on the estimates, thus enhancing the validity of our analyses.

Advanced from univariate analysis, multivariable MR (MVMR) analyses were carried out to thoroughly evaluate the estimated causal relationships. 33 In this step, IVs associated with multiple cathepsins were taken into consideration together, thereby estimating the direct causal impact of each exposure on a single CVD. 34 MVMR analyses were conducted with the ‘MendelianRandomization’ R package. 30 To mitigate potential bias stemming from univariate analysis, we performed reverse MR analyses, where we employed CVDs as the exposures and cathepsins as the outcomes to detect the existence of reverse causality. In reverse analyses, summary statistics of CVDs and cathepsins were extracted from the same sources as mentioned above, where the IVs for CVDs were from UK Biobank and a GWAS by Sakaue et al., and those for cathepsins were from the INTERVAL study. Reverse MR analyses were conducted with the ‘TwoSampleMR’ R package. All statistical analyses were performed using R software version 4.3.1.

Results

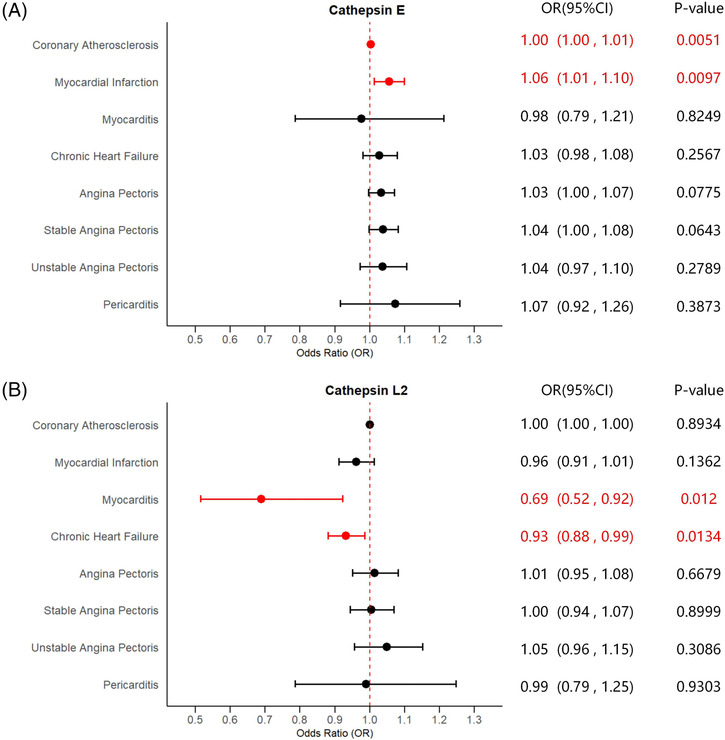

Univariable two‐sample MR analyses were conducted to evaluate the causalities of nine cathepsins (cathepsins B, E, F, G, H, O, S, L2, and Z) on diverse types of cardiovascular system diseases. Detailed results of UVMR are presented in Table 1 . We found significant causal relationships between higher cathepsin E levels and higher risk of coronary atherosclerosis [IVW: P = 0.0051, odds ratio (OR) = 1.0033, 95% confidence interval (CI) = 1.0010–1.0056] and myocardial infarction (IVW: P = 0.0097, OR = 1.0553, 95% CI = 1.0131–1.0993). Conversely, higher cathepsin L2 levels were found to be causally related to reduced risk of myocarditis (IVW: P = 0.0120, OR = 0.6895, 95% CI = 0.5158–0.9216) and chronic heart failure (IVW: P = 0.0134, OR = 0.9316, 95% CI = 0.8807–0.9854). Significant estimates of UVMR are presented in Figure 2 as forest plots. The significant causal relationship for coronary atherosclerosis was supported by the MR‐Egger and weighted median methods (MR‐Egger: P = 0.0378, OR = 1.0065, 95% CI = 1.0013–1.0117; weighted median: P = 0.0366, OR = 1.0034, 95% CI = 1.0002–1.0066), as the causal relationships for myocardial infarction (weighted median: P = 0.0298, OR = 1.0617, 95% CI = 1.0059–1.1206), myocarditis (weighted median: P = 0.0404, OR = 0.6551, 95% CI = 0.4371–0.9817), and chronic heart failure (weighted median: P = 0.0409, OR = 0.9263, 95% CI = 0.8607–0.9968) were only corroborated by the weighted median approach. Cochran's Q, MR‐Egger intercept, and MR‐PRESSO global tests did not yield any evidence indicating the presence of heterogeneity or horizontal pleiotropy. The results of the heterogeneity and pleiotropy tests for UVMR are displayed in Table S3 . No causal relationships were observed between the other types of cathepsins and any cardiovascular events.

Table 1.

Causal relationships of cathepsins on CVDs risk estimated by UVMR

| Cathepsin | nSNP | IVW | MR‐Egger | Weighted median | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P value | OR (95% CI) | P value | OR (95% CI) | P value | OR (95% CI) | ||

| Cathepsin B | |||||||

| Coronary atherosclerosis | 19 | 0.5423 | 0.9992 (0.9965–1.0018) | 0.9188 | 1.0003 (0.9939–1.0068) | 0.4194 | 1.0009 (0.9988–1.0029) |

| Myocardial infarction | 20 | 0.6249 | 0.9887 (0.9447–1.0348) | 0.9905 | 1.0006 (0.9011–1.1112) | 0.4714 | 1.0175 (0.9706–1.0665) |

| Myocarditis | 20 | 0.8703 | 1.0153 (0.846–1.2185) | 0.6354 | 1.1087 (0.729–1.686) | 0.3956 | 0.8915 (0.6839–1.162) |

| Chronic heart failure | 20 | 0.4895 | 0.9865 (0.9492–1.0253) | 0.3986 | 0.9628 (0.8835–1.0492) | 0.7165 | 0.99 (0.9377–1.0452) |

| Angina pectoris | 20 | 0.4022 | 0.9792 (0.9321–1.0286) | 0.3054 | 1.0593 (0.9517–1.1791) | 0.8366 | 0.9955 (0.9535–1.0393) |

| Stable angina pectoris | 20 | 0.4388 | 0.9787 (0.9268–1.0335) | 0.8731 | 1.0103 (0.8923–1.144) | 0.9535 | 0.9985 (0.9502–1.0493) |

| Unstable angina pectoris | 20 | 0.1319 | 1.04 (0.9883–1.0944) | 0.1941 | 1.0828 (0.9646–1.2156) | 0.3990 | 1.0308 (0.9607–1.1059) |

| Pericarditis | 20 | 0.6324 | 1.0386 (0.8892–1.2132) | 0.3981 | 0.8529 (0.5948–1.2229) | 0.6007 | 0.9585 (0.8176–1.1235) |

| Cathepsin E | |||||||

| Coronary atherosclerosis | 11 | 0.0051 | 1.0033 (1.001–1.0056) | 0.0378 | 1.0065 (1.0013–1.0117) | 0.0366 | 1.0034 (1.0002–1.0066) |

| Myocardial infarction | 11 | 0.0097 | 1.0553 (1.0131–1.0993) | 0.6741 | 1.0192 (0.9355–1.1104) | 0.0298 | 1.0617 (1.0059–1.1206) |

| Myocarditis | 11 | 0.8249 | 0.9758 (0.7855–1.2123) | 0.7059 | 0.9268 (0.6322–1.3587) | 0.7257 | 0.9479 (0.7028–1.2784) |

| Chronic heart failure | 11 | 0.2567 | 1.028 (0.9801–1.0783) | 0.5083 | 1.0361 (0.9366–1.1462) | 0.4243 | 1.026 (0.9634–1.0927) |

| Angina pectoris | 11 | 0.0775 | 1.0328 (0.9964–1.0706) | 0.9851 | 1.0007 (0.93–1.0768) | 0.5655 | 1.0138 (0.9675–1.0622) |

| Stable angina pectoris | 11 | 0.0643 | 1.0386 (0.9978–1.0811) | 0.2047 | 1.0674 (0.9721–1.1721) | 0.1636 | 1.0383 (0.9848–1.0947) |

| Unstable angina pectoris | 11 | 0.2789 | 1.0361 (0.9717–1.1049) | 0.7538 | 0.9788 (0.8598–1.1144) | 0.5206 | 1.027 (0.9468–1.114) |

| Pericarditis | 11 | 0.3873 | 1.0726 (0.915–1.2573) | 0.7749 | 0.9525 (0.6892–1.3165) | 0.5101 | 1.0726 (0.8707–1.3214) |

| Cathepsin F | |||||||

| Coronary atherosclerosis | 12 | 0.9618 | 0.9999 (0.9979–1.002) | 0.5776 | 0.9984 (0.9931–1.0038) | 0.9501 | 1.0001 (0.9976–1.0026) |

| Myocardial infarction | 11 | 0.8061 | 1.0052 (0.9645–1.0476) | 0.9339 | 0.9951 (0.8883–1.1146) | 0.9213 | 1.0023 (0.9582–1.0484) |

| Myocarditis | 11 | 0.8680 | 1.017 (0.8337–1.2405) | 0.6180 | 1.1443 (0.6861–1.9084) | 0.9543 | 1.0077 (0.7739–1.3123) |

| Chronic heart failure | 11 | 0.4742 | 1.0138 (0.9765–1.0525) | 0.7588 | 0.9837 (0.8885–1.0891) | 0.4418 | 1.0216 (0.9675–1.0787) |

| Angina pectoris | 11 | 0.3805 | 1.0166 (0.9799–1.0546) | 0.8583 | 0.9908 (0.8981–1.0931) | 0.9541 | 0.9987 (0.9565–1.0429) |

| Stable angina pectoris | 11 | 0.5375 | 1.0108 (0.9768–1.0461) | 0.1638 | 0.938 (0.8636–1.0189) | 0.5882 | 0.9879 (0.9455–1.0323) |

| Unstable angina pectoris | 11 | 0.9013 | 1.004 (0.9426–1.0694) | 0.9861 | 1.0016 (0.8416–1.1921) | 0.7994 | 0.9917 (0.9302–1.0573) |

| Pericarditis | 11 | 0.1615 | 1.0953 (0.9643–1.244) | 0.8473 | 1.0325 (0.7526–1.4164) | 0.5754 | 1.0494 (0.8865–1.2423) |

| Cathepsin G | |||||||

| Coronary atherosclerosis | 12 | 0.2465 | 0.9987 (0.9965–1.0009) | 0.4965 | 0.9982 (0.993–1.0033) | 0.2606 | 0.9984 (0.9957–1.0012) |

| Myocardial infarction | 12 | 0.6398 | 0.9882 (0.9403–1.0386) | 0.1853 | 0.9198 (0.8197–1.0321) | 0.5079 | 0.9777 (0.9147–1.0451) |

| Myocarditis | 12 | 0.9316 | 0.9883 (0.7552–1.2934) | 0.2462 | 1.431 (0.8091–2.5309) | 0.3744 | 0.8599 (0.6163–1.1997) |

| Chronic heart failure | 12 | 0.2259 | 1.0323 (0.9805–1.0868) | 0.4132 | 1.0547 (0.9333–1.1919) | 0.5780 | 1.0189 (0.9538–1.0885) |

| Angina pectoris | 12 | 0.3715 | 0.98 (0.9374–1.0245) | 0.0685 | 0.9052 (0.8227–0.996) | 0.3900 | 0.9724 (0.9123–1.0365) |

| Stable angina pectoris | 12 | 0.6704 | 0.9871 (0.9296–1.0481) | 0.1849 | 0.8995 (0.7776–1.0407) | 0.3218 | 1.0358 (0.9662–1.1104) |

| Unstable angina pectoris | 12 | 0.4519 | 0.9752 (0.9133–1.0412) | 0.0755 | 0.8547 (0.7318–0.9982) | 0.8752 | 0.9923 (0.9007–1.0932) |

| Pericarditis | 11 | 0.6543 | 0.963 (0.8165–1.1358) | 0.8810 | 1.0299 (0.7078–1.4986) | 0.8894 | 0.9841 (0.7856–1.2329) |

| Cathepsin H | |||||||

| Coronary atherosclerosis | 11 | 0.2040 | 0.9991 (0.9977–1.0005) | 0.1588 | 0.9984 (0.9964–1.0004) | 0.0409 | 0.9987 (0.9975–0.9999) |

| Myocardial infarction | 11 | 0.0519 | 0.9781 (0.9564–1.0002) | 0.0448 | 0.9643 (0.9352–0.9942) | 0.0223 | 0.9716 (0.9479–0.9959) |

| Myocarditis | 11 | 0.2382 | 0.9267 (0.8167–1.0516) | 0.6352 | 0.9557 (0.7975–1.1452) | 0.4656 | 0.9486 (0.8234–1.093) |

| Chronic heart failure | 11 | 0.9386 | 0.9985 (0.9605–1.0379) | 0.4632 | 0.9796 (0.9293–1.0326) | 0.0957 | 0.9749 (0.9461–1.0045) |

| Angina pectoris | 11 | 0.2290 | 0.9799 (0.9481–1.0128) | 0.2410 | 0.9704 (0.926–1.017) | 0.0229 | 0.9742 (0.9526–0.9964) |

| Stable angina pectoris | 11 | 0.3777 | 0.9853 (0.9534–1.0183) | 0.0810 | 0.9602 (0.922–0.9999) | 0.0536 | 0.9764 (0.9529–1.0004) |

| Unstable angina pectoris | 11 | 0.3200 | 0.9833 (0.9513–1.0165) | 0.0424 | 0.9483 (0.9074–0.991) | 0.0558 | 0.9663 (0.9329–1.0008) |

| Pericarditis | 11 | 0.7806 | 0.9888 (0.9135–1.0703) | 0.1939 | 0.9241 (0.8277–1.0318) | 0.2839 | 0.9531 (0.8731–1.0406) |

| Cathepsin O | |||||||

| Coronary atherosclerosis | 11 | 0.9470 | 1.0001 (0.9978–1.0023) | 0.9530 | 0.9998 (0.9946–1.0051) | 0.5319 | 1.001 (0.9979–1.004) |

| Myocardial infarction | 12 | 0.9648 | 0.999 (0.9551–1.0449) | 0.9909 | 1.0007 (0.8878–1.1279) | 0.8839 | 1.0045 (0.9453–1.0675) |

| Myocarditis | 12 | 0.7892 | 1.0348 (0.8052–1.3298) | 0.5850 | 1.1876 (0.6536–2.1576) | 0.7607 | 0.9504 (0.685–1.3186) |

| Chronic heart failure | 12 | 0.2733 | 1.03 (0.9769–1.086) | 0.2396 | 1.0957 (0.9495–1.2645) | 0.5834 | 1.0204 (0.9493–1.097) |

| Angina pectoris | 12 | 0.3224 | 1.021 (0.9799–1.0638) | 0.9524 | 0.9966 (0.8923–1.1129) | 0.1533 | 1.0403 (0.9854–1.0982) |

| Stable angina pectoris | 11 | 0.2306 | 1.034 (0.979–1.0922) | 0.4632 | 1.0648 (0.9069–1.2502) | 0.5094 | 1.0212 (0.9595–1.0868) |

| Unstable angina pectoris | 12 | 0.7750 | 1.0094 (0.9467–1.0762) | 0.7209 | 1.0324 (0.871–1.2237) | 0.7369 | 1.0144 (0.9332–1.1027) |

| Pericarditis | 12 | 0.5478 | 1.0663 (0.8649–1.3147) | 0.4638 | 1.2201 (0.7314–2.0352) | 0.4841 | 1.0911 (0.8547–1.3927) |

| Cathepsin S | |||||||

| Coronary atherosclerosis | 24 | 0.1814 | 1.0008 (0.9996–1.0021) | 0.1854 | 1.0015 (0.9994–1.0036) | 0.1303 | 1.0013 (0.9996–1.0031) |

| Myocardial infarction | 24 | 0.8767 | 0.9964 (0.9515–1.0433) | 0.4479 | 1.0339 (0.9501–1.125) | 0.4321 | 1.017 (0.9751–1.0607) |

| Myocarditis | 24 | 0.2586 | 0.9154 (0.7852–1.0671) | 0.9275 | 0.9875 (0.7551–1.2914) | 0.3174 | 0.8906 (0.7096–1.1177) |

| Chronic heart failure | 24 | 0.5192 | 1.0147 (0.9707–1.0606) | 0.7835 | 1.012 (0.9302–1.1011) | 0.5964 | 1.0125 (0.967–1.0602) |

| Angina pectoris | 24 | 0.8631 | 0.9971 (0.965–1.0303) | 0.4027 | 1.0258 (0.9675–1.0876) | 0.3317 | 1.019 (0.981–1.0584) |

| Stable angina pectoris | 24 | 0.7158 | 0.9942 (0.9635–1.0258) | 0.6060 | 1.0158 (0.9578–1.0773) | 0.8967 | 1.0026 (0.9637–1.0431) |

| Unstable angina pectoris | 24 | 0.5836 | 1.0123 (0.9691–1.0574) | 0.5353 | 1.0266 (0.9461–1.1139) | 0.4820 | 1.022 (0.9618–1.0861) |

| Pericarditis | 24 | 0.1512 | 0.9368 (0.8568–1.0242) | 0.9903 | 1.0009 (0.8606–1.1642) | 0.3596 | 0.9421 (0.8291–1.0704) |

| Cathepsin L2 | |||||||

| Coronary atherosclerosis | 12 | 0.8934 | 0.9998 (0.9963–1.0032) | 0.1034 | 1.0063 (0.9994–1.0132) | 0.5433 | 1.0009 (0.9979–1.0039) |

| Myocardial infarction | 10 | 0.1362 | 0.961 (0.9121–1.0126) | 0.6849 | 1.0285 (0.9023–1.1723) | 0.3835 | 0.9706 (0.9076–1.038) |

| Myocarditis | 10 | 0.0120 | 0.6895 (0.5158–0.9216) | 0.7658 | 1.123 (0.5369–2.3487) | 0.0404 | 0.6551 (0.4371–0.9817) |

| Chronic heart failure | 10 | 0.0134 | 0.9316 (0.8807–0.9854) | 0.5965 | 0.9595 (0.8284–1.1114) | 0.0409 | 0.9263 (0.8607–0.9968) |

| Angina pectoris | 10 | 0.6679 | 1.0141 (0.9511–1.0814) | 0.0558 | 1.1639 (1.0189–1.3296) | 0.8868 | 1.0046 (0.9433–1.0698) |

| Stable angina pectoris | 10 | 0.8999 | 1.004 (0.9432–1.0688) | 0.0988 | 1.1386 (0.9936–1.3047) | 0.7130 | 1.0131 (0.9451–1.0861) |

| Unstable angina pectoris | 10 | 0.3086 | 1.0494 (0.9563–1.1516) | 0.0309 | 1.2985 (1.0677–1.5792) | 0.5844 | 1.0286 (0.9296–1.1382) |

| Pericarditis | 10 | 0.9303 | 0.9897 (0.7856–1.2469) | 0.9088 | 0.9668 (0.5518–1.6938) | 0.7957 | 0.9645 (0.7339–1.2676) |

| Cathepsin Z | |||||||

| Coronary atherosclerosis | 12 | 0.1331 | 1.0012 (0.9996–1.0028) | 0.4900 | 1.0009 (0.9984–1.0035) | 0.2280 | 1.0011 (0.9993–1.003) |

| Myocardial infarction | 13 | 0.8737 | 0.9973 (0.965–1.0307) | 0.8576 | 0.9945 (0.9381–1.0543) | 0.4083 | 0.9825 (0.9421–1.0245) |

| Myocarditis | 13 | 0.4066 | 1.0887 (0.8907–1.3308) | 0.7069 | 1.0694 (0.7605–1.5037) | 0.9792 | 1.003 (0.8002–1.2572) |

| Chronic heart failure | 13 | 0.4762 | 0.9874 (0.9535–1.0225) | 0.5586 | 0.9817 (0.9246–1.0424) | 0.7133 | 0.9916 (0.9482–1.0371) |

| Angina pectoris | 13 | 0.0880 | 1.0265 (0.9961–1.0579) | 0.6700 | 1.0115 (0.9609–1.0648) | 0.1983 | 1.024 (0.9877–1.0616) |

| Stable angina pectoris | 12 | 0.1325 | 1.0234 (0.993–1.0547) | 0.6400 | 1.0134 (0.9602–1.0695) | 0.3359 | 1.0195 (0.9802–1.0603) |

| Unstable angina pectoris | 13 | 0.2862 | 0.976 (0.9335–1.0205) | 0.3557 | 0.9621 (0.8894–1.0407) | 0.6341 | 0.9861 (0.9309–1.0446) |

| Pericarditis | 13 | 0.4974 | 1.0469 (0.917–1.1952) | 0.5307 | 1.0743 (0.8648–1.3345) | 0.6278 | 1.0367 (0.8961–1.1995) |

CI, confidence interval; CVD, cardiovascular disease; IVW, inverse variance weighted; MR, Mendelian Randomization; OR, odds ratio; SNP, single nucleotide polymorphism; UVMR, univariable Mendelian randomization.

Fig. 2.

Forest plots of significant estimates of UVMR analyses. The IVW method was employed to explore the causalities of cathepsins on CVDs risk. (A) UVMR results of cathepsin E on CVDs risk; (B) UVMR results of cathepsin L2 on CVDs risk. CVD, cardiovascular disease; CI, confidence interval; IVW, inverse variance weighted; OR, odds ratio; UVMR, univariable Mendelian randomization. Statistically significant results are indicated in red, with error bars representing 95% confidence intervals.

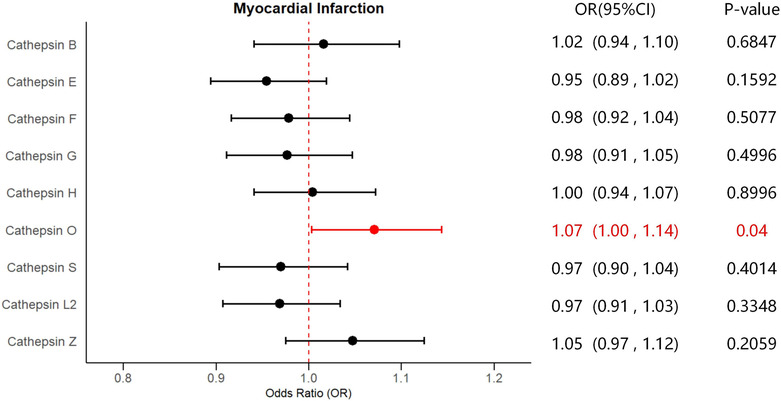

In addition, reverse MR analyses were also performed to evaluate the existence of reverse causality. Detailed results of reverse analyses are presented in Table S4 . There were no reverse causalities between cathepsin E levels and the risk of coronary atherosclerosis and myocardial infarction, and cathepsin L2 levels and the risk of myocarditis and chronic heart failure. Nevertheless, evidence was found that a higher risk of myocardial infarction was causally related to increased levels of cathepsin O (IVW: P = 0.0400, OR = 1.0708, 95% CI = 1.0031–1.1431), with no signs of heterogeneity and horizontal pleiotropy according to the results of Cochran's Q, MR‐Egger, and MR‐PRESSO global tests. Significant estimates of reverse MR analyses are presented in Figure 3 as forest plots. The results of the sensitivity tests for reverse analyses are displayed in Table S5 . No significant causalities of cardiovascular events on the other types of cathepsin levels were discovered.

Fig. 3.

Forest plot of significant estimates of reverse MR analyses. The IVW method was employed to explore the causalities of myocardial infarction risk on cathepsins levels. CVD, cardiovascular disease; CI, confidence interval; IVW, inverse variance weighted; MR, Mendelian randomization; OR, odds ratio. Statistically significant results are indicated in red, with error bars representing 95% confidence intervals.

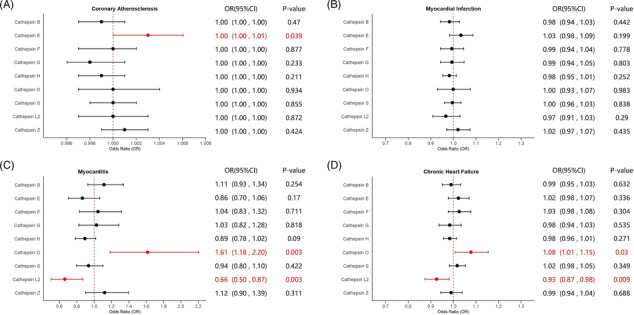

Under the adjustment of the other cathepsins, MVMR analyses were also conducted to validate the unbiased results in univariate analysis with independent estimates. Detailed results of MVMR analyses and sensitivity analyses are shown in Table S6 . For the causal relationship of coronary atherosclerosis, higher cathepsin E levels remained robustly related to a raised risk of coronary atherosclerosis after adjusting for the other types of cathepsins (IVW: P = 0.0390, OR = 1.0030, 95% CI = 1.0000–1.0060), with heterogeneity detected in the estimate based on Cochran's Q test. However, the causality of cathepsin E levels on the risk of myocardial infarction did not persist after the adjustment for the other types of cathepsins in the MVMR analysis (IVW: P = 0.1990, OR = 1.0336, 95% CI = 0.9831–1.0865). The causal effects of higher cathepsins L2 levels on decreased risk of myocarditis (IVW: P = 0.0030, OR = 0.6610, 95% CI = 0.5031–0.8676) and chronic heart failure (IVW: P = 0.0090, OR = 0.9259, 95% CI = 0.8737–0.9812) were steadily observed, which were further supported by the MR‐Egger method (P = 0.0040, OR = 0.6630, 95% CI = 0.5021–0.8763 for myocarditis; P = 0.0110, OR = 0.9268, 95% CI = 0.8746–0.9831 for chronic heart failure) with no heterogeneity detected. In addition, statistically robust causalities of higher cathepsin O levels on elevated risk of myocarditis (IVW: P = 0.0030, OR = 1.6145, 95% CI = 1.1829–2.2034) and chronic heart failure (IVW: P = 0.0300, OR = 1.0779, 95% CI = 1.0070–1.1537) were discovered, corroborated by the MR‐Egger method (P = 0.0040, OR = 1.6064, 95% CI = 1.1653–2.2144 for myocarditis; P = 0.0430, OR = 1.0747, 95% CI = 1.0020–1.1514). Results of Cochran's Q tests indicated no signs of heterogeneity. Estimates of MVMR are presented in Figure 4 as forest plots. No statistically significant causal relationships between the other types of cathepsins and CVDs were discovered in the multivariate analyses. In all analyses, the MR‐Egger intercept test did not suggest the presence of horizontal pleiotropy.

Fig. 4.

Forest plots of estimates of MVMR analyses. The IVW method was employed to explore the causalities of cathepsins on CVDs risk. (A) MVMR results of cathepsins on coronary atherosclerosis risk; (B) MVMR results of cathepsins on myocardial infarction risk; (C) MVMR results of cathepsins on myocarditis risk; (D) MVMR results of cathepsins on chronic heart failure risk. CI, confidence interval; CVD, cardiovascular disease; IVW, inverse variance weighted; MVMR, multivariable Mendelian randomization; OR, odds ratio. Statistically significant results are indicated in red, with error bars representing 95% confidence intervals.

Discussion

The development and progression of CVDs encompass an intensely intricate process in which proteolysis plays a pivotal role. Among the critical proteolytic enzymes, cathepsins have garnered significant attention. 35 Through MR analyses, we capitalized on summary genetic statistics from the UK Biobank and GWASs to systematically investigate the potential causal relationships between nine types of cathepsins and the risk of diverse CVDs. As far as we know, this is the first study combining UVMR, reverse MR, and MVMR analyses to establish causalities between cathepsins and CVDs. Taken together, we concluded that cathepsin E was a risk factor for coronary atherosclerosis, while cathepsin O served as a risk factor for myocarditis and chronic heart failure. On the contrary, cathepsin L2 was proven to exert protective effects on the risk of myocarditis and chronic heart failure. Intriguingly, reverse analyses suggested that myocardial infarction contributed to increasing cathepsin E levels.

The current study provided evidence that higher cathepsin E levels were causally related to increased coronary atherosclerosis risk. Results of the IVW method were consistent with other complementary methods, including MR‐Egger and weighted median, suggesting a robust causality. No heterogeneity, horizontal pleiotropy, and reverse causality were found. Cathepsins, a group of cysteine proteases characterized by their lysosomal activity, have long been considered a major contributing factor in a range of cardiovascular disorders. 35 Although direct evidence regarding cathepsin E remains elusive, previous studies have explored the possible mechanisms through which cathepsins interplay with cardiac and vascular conditions, suggesting that the effects of cathepsins on coronary atherosclerosis may be linked to their unique influences on multifaceted pathophysiological processes, including ECM remodelling and apoptosis. 36 In addition, cathepsins have an essential role in lipid metabolism and inflammation, contributing to the formation of the necrotic core and foam cells and, consequently, the development of atherosclerotic plaques. 37 Furthermore, cathepsins were found to be overexpressed in nearly every cell type within the plaque tissue, with particular prominence in macrophages, endothelial cells, and smooth muscle cells, ultimately exacerbating atherosclerotic lesions. 38 As former studies have revealed the distinct roles of cathepsin B, C, K, S, and L in atherosclerosis, our study discovered a potential causality of cathepsin E on the risk of coronary atherosclerosis. 39 Based on the complexity of the mechanisms of cathepsins in relation to atherosclerosis, further research is required to clarify the role of cathepsin E in atherosclerosis. Despite evidence of univariate analysis indicating the significant causal correlation between higher cathepsin E levels and increased myocardial infarction risk, such statistical significance did not remain after adjusting for the other types of cathepsins in the MVMR analyses, which could not establish a robust causality.

Furthermore, our UVMR and MVMR analyses suggested a protective role of cathepsin L2 in myocarditis and chronic heart failure, supported by a growing body of literature that elucidated the complex roles of cathepsins in CVDs. Cathepsin L2 is crucial in modulating the inflammatory response, a key feature in myocarditis. Its role in cytokine modulation, inflammatory molecule production, and lymphocyte activation can modulate inflammation and tissue damage in the myocardium, which are central to myocarditis pathology. 37 Additionally, cathepsin L2 interacts with the immune system, influencing immune cell activation, thus altering the disease course. 37 Deficiency in cathepsin L2 may lead to impaired CD4 + T cell positive selection, eventually resulting in dysfunction in both innate and adaptive immunity. 40 As myocarditis is widely known as an immune‐mediated disease, the roles of cathepsin L2 in both inflammation and immune system regulation correspond with its protective effects on myocarditis found in our study. 41 Cathepsin L2 has a multifaceted impact on heart failure. One of its most significant roles is regulating ECM remodelling. Heart failure is characterized by myocardial remodelling, often in the form of fibrosis marked by excessive collagen accumulation. 42 Cathepsin L2 is essential in regulating extracellular protein turnover and maintaining the balance between the deposition and degradation of collagen. 43 Because alteration of extracellular collagen turnover can lead to myocardial stiffening and dilation, cathepsin L2 is able to alleviate pathological cardiac remodelling in the context of heart failure, reducing myocardial fibrosis and preserving cardiac function. The cardioprotection of cathepsin L2 also includes the modulation of autophagy and lysosomal activity. Autophagy serves as an instrumental mechanism to clear damaged cells and misfolded proteins in the heart and thus plays a pivotal role in maintaining cellular health. 44 Cathepsin L2 may be essential in mitigating cardiac dysfunction in heart failure by activating the autophagy‐lysosomal pathway. 45 Deficiencies in cathepsin L2 can potentially result in decreased lysosomal activity and impaired autophagy, which leads to the accumulation of cytotoxic autophagosomes in cardiomyocytes, contributing to the development of heart failure. 46 Therefore, cathepsin L2 could protect against cellular stress and damage by facilitating autophagy in the heart to prevent the occurrence of heart failure. Furthermore, cathepsin L2's influence includes the regulation of the immune response in the cardiac microenvironment. Chronic heart failure is often accompanied by a sustained inflammatory response, which can exacerbate cardiac damage and worsen the disease progression. 42 Cathepsin L2 is implicated in apoptosis, particularly through its interaction with Bid, a key pro‐apoptotic member of the Bcl‐2 family significant for death receptor‐mediated apoptosis. This process involves releasing apoptogenic factors like cytochrome c and, eventually, launching the apoptotic cascade. 47 , 48 It has been demonstrated that cathepsin L2 may mediate the apoptosis of T cells, proving the significant role of cathepsin L2 in modulating the immune response. 49 , 50 Because the suppression of inflammation largely depends on apoptosis of inflammatory cells such as lymphocytes, cathepsin L2 can potentially reduce inflammatory‐mediated damage in heart failure by tempering the immune response. Additionally, the enzyme's role in antigen processing and presentation further implicates it in the immune‐regulatory processes within the heart. Cathepsin L2 is suggested to play a pivotal role in the selection of the surface peptide‐MHC II complexes and the MHC class I pathway. 51 It shapes the adaptive immune response, potentially influencing the progression of myocarditis towards chronic heart failure. 52 This dimension of cathepsin L2's activity suggests that its dysregulation could disrupt immune homeostasis in the heart, potentially influencing the chronicity and severity of heart failure. 41

On the contrary, the reverse MR analyses revealed that a higher risk of myocardial infarction was causally related to increased cathepsin O levels. Results of MVMR also demonstrated positive causalities of elevated cathepsin O levels on higher risk of myocarditis and chronic heart failure. Albeit indirectly related to cathepsin O, previous research has shown a general trend of increased cathepsin levels in the context of myocardial infarction. 53 , 54 Myocardial infarction might regulate cathepsins expression by affecting transcription factors SP1, ETS1, the lysosomal biogenesis regulator, and the transcription factor EB. 38 Such pathologic alterations suggested a latent association between cathepsin levels and the severity of myocardial infarction. 54 Based on the general functions of cathepsins, it is plausible that cathepsin O could contribute to the inflammatory cascade and immune dysfunction in the development of myocarditis, exacerbating tissue damage and disease progression. 37 In addition, cathepsin O might be involved in ECM remodelling, autophagic pathways, and cellular stress responses. Dysregulation of cathepsin O could potentially lead to adverse myocardial remodelling in chronic heart failure. 38 It is worth noting that specific studies on cathepsin O in the cardiovascular system are still lacking. The exact mechanisms by which cathepsin O influences these conditions remain elusive. Because our MR analyses estimated potential causalities of cathepsin on cardiovascular system disorders on a genetic level, future research, specifically focusing on the interplay of cathepsin O and CVDs, is necessary to provide more concrete evidence and understanding in this aspect.

To our knowledge, this study represents a groundbreaking approach to explore the causal relationships between various cathepsins and a range of CVDs by MR analyses, paving the way for a new understanding of genetic influences in cardiovascular pathology. By combining UVMR, reverse MR and MVMR, our study offered a multifaceted view of genetic causal relationships between cathepsins and CVDs, enhancing the validity of our findings through methodological diversity and cross‐validation. This comprehensive approach could effectively avoid confounding due to its reliance on genetic variants as IVs and reduce the risk of reverse causation, providing a more robust inference of causality. Most importantly, our findings have significant implications for developing predictive markers and therapeutic targets for CVDs, leveraging genetic insights for personalized medicine in cardiovascular care.

While our study provided significant insights into the causal relationships between cathepsins and CVDs, it is significant to acknowledge its limitations. Because the majority of our study population was of European descent, it is important to acknowledge that the generalizability of our findings to other ethnic groups may be limited. Additionally, heterogeneity was observed in our study, which suggested variability in the effects of genetic variants. This could be due to differences in genetic architecture or environmental interactions, indicating the complexity of genetic influences on CVDs and possibly affecting the interpretation of our findings. Furthermore, our research served as a pioneering effort in linking cathepsins with CVDs at a genetic level. However, these findings should be considered preliminary, stimulating further research bridging genetic findings with clinical applications.

Conclusions

To sum up, our study discovered that elevated levels of cathepsin E were causally related to an increased risk of coronary atherosclerosis, whereas high levels of cathepsin L2 exerted protective causal effects on reduced risk of myocarditis and chronic heart failure. Additionally, cathepsin O had a positive causal relationship with a higher risk of myocarditis and chronic heart failure, as its expression might be regulated by myocardial infarction. This research contributes to the development of predictive markers and therapeutic targets for better prediction, management, and treatment of CVDs, as further research is still required to translate our findings into therapeutic interventions and clinical practices.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Funding

Not applicable.

Supporting information

Table S1. Detailed information of summary data in this MR study.

Table S2. Detailed information of SNPs selected as IVs.

Table S3. Heterogeneity and pleiotropy tests of UVMR between cathepsins and CVDs.

Table S4. Results of reverse MR analyses between CVDs and cathepsins.

Table S5. Heterogeneity and pleiotropy tests of reverse MR between CVDs and cathepsins.

Table S6. Results of MVMR analyses between cathepsins and CVDs.

Table S7. Data of significant estimates of UVMR underlying Fig. 2.

Table S8. Data of significant estimates of reverseMR underlying Fig. 3.

Table S9. Data of estimates of MVMR underlying Fig. 4.

Acknowledgements

This study has utilized data from the GWASs by Sun et al. and Sakaue et al. and the UK Biobank. The authors extend their gratitude to the teams and behind these projects and all the contributors of the data.

Zeng, R. , Zhou, Z. , Liao, W. , and Guo, B. (2024) Genetic insights into the role of cathepsins in cardiovascular diseases: a Mendelian randomization study. ESC Heart Failure, 11: 2707–2718. 10.1002/ehf2.14826.

References

- 1. Benziger CP, Roth GA, Moran AEJG. The global burden of disease study and the preventable burden of NCD. Global heart 2016;11:393‐397. doi: 10.1016/j.gheart.2016.10.024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Shepard D, VanderZanden A, Moran A, Naghavi M, Murray C, Roth GJC, et al. Ischemic heart disease worldwide, 1990 to 2013: estimates from the Global Burden of Disease study 2013. Circul: Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes 2015;8:455‐456. doi: 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.115.002007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Bragazzi NL, Zhong W, Shu J, Abu Much A, Lotan D, Grupper A, et al. Burden of heart failure and underlying causes in 195 countries and territories from 1990 to 2017. Eur J Prev Cardiol 2021;28:1682‐1690. doi: 10.1093/eurjpc/zwaa147 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Fonović M, Turk B. Cysteine cathepsins and extracellular matrix degradation. Biochim Biophys Acta (BBA)‐general subjects 2014;1840:2560‐2570. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagen.2014.03.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Brix K, Dunkhorst A, Mayer K, Jordans S. Cysteine cathepsins: cellular roadmap to different functions. Biochimie 2008;90:194‐207. doi: 10.1016/j.biochi.2007.07.024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Turk V, Stoka V, Vasiljeva O, Renko M, Sun T, Turk B, et al. Cysteine cathepsins: from structure, function and regulation to new frontiers. Biochim Biophys Acta 2012;1824:68‐88. doi: 10.1016/j.bbapap.2011.10.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Reiser J, Adair B, Reinheckel T. Specialized roles for cysteine cathepsins in health and disease. J Clin Invest 2010;120:3421‐3431. doi: 10.1172/jci42918 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Cheng XW, Kikuchi R, Ishii H, Yoshikawa D, Hu L, Takahashi R, et al. Circulating cathepsin K as a potential novel biomarker of coronary artery disease. Atherosclerosis 2013;228:211‐216. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2013.01.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Kim DE, Kim JY, Schellingerhout D, Kim EJ, Kim HK, Lee S, et al. Protease imaging of human atheromata captures molecular information of atherosclerosis, complementing anatomic imaging. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 2010;30:449‐456. doi: 10.1161/atvbaha.109.194613 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Liu J, Ma L, Yang J, Ren A, Sun Z, Yan G, et al. Increased serum cathepsin S in patients with atherosclerosis and diabetes. Atherosclerosis 2006;186:411‐419. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2005.08.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Liu J, Sukhova GK, Yang JT, Sun J, Ma L, Ren A, et al. Cathepsin L expression and regulation in human abdominal aortic aneurysm, atherosclerosis, and vascular cells. Atherosclerosis 2006;184:302‐311. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2005.05.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Mareti A, Kritsioti C, Georgiopoulos G, Vlachogiannis NI, Delialis D, Sachse M, et al. Cathepsin B expression is associated with arterial stiffening and atherosclerotic vascular disease. Eur J Prev Cardiol 2020;27:2288‐2291. doi: 10.1177/2047487319893042 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Aimo A, Januzzi JL Jr, Bayes‐Genis A, Vergaro G, Sciarrone P, Passino C, et al. Clinical and prognostic significance of sST2 in heart failure: JACC review topic of the week. J Am Coll Cardiol 2019;74:2193‐2203. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2019.08.1039 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Yamac AH, Sevgili E, Kucukbuzcu S, Nasifov M, Ismailoglu Z, Kilic E, et al. Role of cathepsin D activation in major adverse cardiovascular events and new‐onset heart failure after STEMI. Herz 2015;40:912‐920. doi: 10.1007/s00059-015-4311-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Zhao G, Li Y, Cui L, Li X, Jin Z, Han X, et al. Increased circulating cathepsin K in patients with chronic heart failure. PLoS ONE 2015;10:e0136093. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0136093 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Burgess S, Smith GD, Davies NM, Dudbridge F, Gill D, Glymour MM, et al. Guidelines for performing Mendelian randomization investigations: update for summer 2023. 2019;4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 17. Davey Smith G, Hemani G. Mendelian randomization: genetic anchors for causal inference in epidemiological studies. Human Mol Gen 2014;23:R89‐R98. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddu328 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Emdin CA, Khera AV, Kathiresan SJJ. Mendelian randomization. 2017;318:1925‐1926. doi: 10.1001/jama.2017.17219 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Sun BB, Maranville JC, Peters JE, Stacey D, Staley JR, Blackshaw J, et al. Genomic atlas of the human plasma proteome. Nature 2018;558:73‐79. doi: 10.1038/s41586-018-0175-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Burgess S, Scott RA, Timpson NJ, Davey Smith G, Thompson SG, epidemiology E‐ICJEjo . Using published data in Mendelian randomization: a blueprint for efficient identification of causal risk factors. Eur J Epidemiol 2015;30:543‐552. doi: 10.1007/s10654-015-0011-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Davey Smith G, Holmes MV, Davies NM, Ebrahim S. Mendel's laws, Mendelian randomization and causal inference in observational data: substantive and nomenclatural issues. Eur J Epidemiol 2020;35:99‐111. doi: 10.1007/s10654-020-00622-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Kamat MA, Blackshaw JA, Young R, Surendran P, Burgess S, Danesh J, et al. PhenoScanner V2: an expanded tool for searching human genotype–phenotype associations. Bioinformatics 2019;35:4851‐4853. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btz469 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Sakaue S, Kanai M, Tanigawa Y, Karjalainen J, Kurki M, Koshiba S, et al. A cross‐population atlas of genetic associations for 220 human phenotypes. Nat Gen 2021;53:1415‐1424. doi: 10.1038/s41588-021-00931-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Bowden J, Davey Smith G. Mendelian randomization with invalid instruments: effect estimation and bias detection through Egger regression. Int J Epidemiol 2015;44:512‐525. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyv080 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Bowden J, Davey Smith G, Haycock PC, Burgess S. Consistent estimation in Mendelian randomization with some invalid instruments using a weighted median estimator. Gen Epidemiol 2016;40:304‐314. doi: 10.1002/gepi.21965 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Burgess S, Butterworth A, Thompson SG. Mendelian randomization analysis with multiple genetic variants using summarized data. Gen Epidemiol 2013;37:658‐665. doi: 10.1002/gepi.21758 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Hartwig FP, Davey Smith G, Bowden J. Robust inference in summary data Mendelian randomization via the zero modal pleiotropy assumption. Int J Epidemiol 2017;46:1985‐1998. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyx102 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Hemani G, Zheng J, Elsworth B, Wade KH, Haberland V, Baird D, et al. The MR‐base platform supports systematic causal inference across the human phenome. elife 2018;7:e34408. doi: 10.7554/eLife.34408 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Bowden J, Del Greco MF, Minelli C, Davey Smith G, Sheehan N, Thompson J. A framework for the investigation of pleiotropy in two‐sample summary data Mendelian randomization. Stat Med 2017;36:1783‐1802. doi: 10.1002/sim.7221 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Yavorska OO, Burgess S. Mendelian randomization: an R package for performing Mendelian randomization analyses using summarized data. Int J Epidemiol 2017;46:1734‐1739. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyx034 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Burgess S, Thompson SG. Interpreting findings from Mendelian randomization using the MR‐egger method. Eur J Epidemiol 2017;32:377‐389. doi: 10.1007/s10654-017-0255-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Verbanck M, Chen C‐Y, Neale B, Do R. Detection of widespread horizontal pleiotropy in causal relationships inferred from Mendelian randomization between complex traits and diseases. Nat Gen 2018;50:693‐698. doi: 10.1038/s41588-018-0099-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Sanderson E, Spiller W, Bowden J. Testing and correcting for weak and pleiotropic instruments in two‐sample multivariable Mendelian randomization. Stat Med 2021;40:5434‐5452. doi: 10.1002/sim.9133 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Sanderson E. Multivariable Mendelian randomization and mediation. Cold Spring Harbor Perspect Med 2021;11:a038984. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a038984 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Zhang X, Luo S, Wang M, Shi GP. Cysteinyl cathepsins in cardiovascular diseases. Biochim Biophys (BBA)‐Proteins Proteomics 2020;1868:140360. doi: 10.1016/j.bbapap.2020.140360 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Lutgens SP, Cleutjens KB, Daemen MJ, Heeneman SJTFJ. Cathepsin cysteine proteases in cardiovascular disease. FASEB Journal 2007;21:3029‐3041. doi: 10.1096/fj.06-7924com [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Liu C‐L, Guo J, Zhang X, Sukhova GK, Libby P, Shi G‐P. Cysteine protease cathepsins in cardiovascular disease: from basic research to clinical trials. Nat Rev Cardiol 2018;15:351‐370. doi: 10.1038/s41569-018-0002-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Weiss‐Sadan T, Gotsman I, Blum GJTFJ. Cysteine proteases in atherosclerosis. FEBS Journal 2017;284:1455‐1472. doi: 10.1111/febs.14043 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Wu H, Du Q, Dai Q, Ge J, Cheng XJ. Cysteine protease cathepsins in atherosclerotic cardiovascular diseases. J Atheroscler Thromb 2018;25:111‐123. doi: 10.5551/jat.RV17016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Nakagawa T, Roth W, Wong P, Nelson A, Farr A, Deussing J, et al. Cathepsin L: critical role in Ii degradation and CD4 T cell selection in the thymus. Science 1998;280:450‐453. doi: 10.1126/science.280.5362.450 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Tschöpe C, Ammirati E, Bozkurt B, Caforio AL, Cooper LT, Felix SB, et al. Myocarditis and inflammatory cardiomyopathy: current evidence and future directions. Nat Rev Cardiol 2021;18:169‐193. doi: 10.1038/s41569-020-00435-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Müller AL, Dhalla NS. Role of various proteases in cardiac remodeling and progression of heart failure. Heart Fail Rev 2012;17:395‐409. doi: 10.1007/s10741-011-9269-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Tang Q, Cai J, Shen D, Bian Z, Yan L, Wang YX, et al. Lysosomal cysteine peptidase cathepsin L protects against cardiac hypertrophy through blocking AKT/GSK3beta signaling. J Mol Med (Berl) 2009;87:249‐260. doi: 10.1007/s00109-008-0423-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Machackova J, Barta J, Dhalla NS. Myofibrillar remodeling in cardiac hypertrophy, heart failure and cardiomyopathies. Can J Cardiol 2006;22:953‐968. doi: 10.1016/s0828-282x(06)70315-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Sun M, Ouzounian M, de Couto G, Chen M, Yan R, Fukuoka M, et al. Cathepsin‐L ameliorates cardiac hypertrophy through activation of the autophagy‐lysosomal dependent protein processing pathways. J Am Heart Assoc 2013;2:e000191. doi: 10.1161/jaha.113.000191 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Sandri M. Signaling in muscle atrophy and hypertrophy. Physiology (Bethesda) 2008;23:160‐170. doi: 10.1152/physiol.00041.2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Saelens X, Festjens N, Vande Walle L, van Gurp M, van Loo G, Vandenabeele P. Toxic proteins released from mitochondria in cell death. Oncogene 2004;23:2861‐2874. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1207523 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Stoka V, Turk B, Schendel SL, Kim TH, Cirman T, Snipas SJ, et al. Lysosomal protease pathways to apoptosis. Cleavage of bid, not pro‐caspases, is the most likely route. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:3149‐3157. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M008944200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Alexander‐Miller MA, Leggatt GR, Sarin A, Berzofsky JA. Role of antigen, CD8, and cytotoxic T lymphocyte (CTL) avidity in high dose antigen induction of apoptosis of effector CTL. J Exp Med 1996;184:485‐492. doi: 10.1084/jem.184.2.485 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Kishimoto H, Sprent J. Strong TCR ligation without costimulation causes rapid onset of Fas‐dependent apoptosis of naive murine CD4+ T cells. J Immunol 1999;163:1817‐1826. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.163.4.1817 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Chapman HA. Endosomal proteases in antigen presentation. Curr Opin Immunol 2006;18:78‐84. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2005.11.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Rai A, Narisawa M, Li P, Piao L, Li Y, Yang G, et al. Adaptive immune disorders in hypertension and heart failure: focusing on T‐cell subset activation and clinical implications. J Hypertens 2020;38:1878‐1889. doi: 10.1097/hjh.0000000000002456 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Shalia KK, Mashru MR, Shah VK, Soneji SL, Payannavar S. Levels of cathepsins in acute myocardial infarction. Indian Heart J 2012;64:290‐294. doi: 10.1016/S0019-4832(12)60089-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Stamatelopoulos K, Mueller‐Hennessen M, Georgiopoulos G, Lopez‐Ayala P, Sachse M, Vlachogiannis NI, et al. Cathepsin s levels and survival among patients with non‐st‐segment elevation acute coronary syndromes. J Am Coll Cardiol 2022;80:998‐1010. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2022.05.055 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Table S1. Detailed information of summary data in this MR study.

Table S2. Detailed information of SNPs selected as IVs.

Table S3. Heterogeneity and pleiotropy tests of UVMR between cathepsins and CVDs.

Table S4. Results of reverse MR analyses between CVDs and cathepsins.

Table S5. Heterogeneity and pleiotropy tests of reverse MR between CVDs and cathepsins.

Table S6. Results of MVMR analyses between cathepsins and CVDs.

Table S7. Data of significant estimates of UVMR underlying Fig. 2.

Table S8. Data of significant estimates of reverseMR underlying Fig. 3.

Table S9. Data of estimates of MVMR underlying Fig. 4.