Abstract

BACKGROUND:

Bruton’s tyrosine kinase inhibitors (BTKis) and the BCL-2 inhibitor venetoclax in combination with obinutuzumab (VEN-O) are both recommended as frontline therapy in chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL). However, VEN-O is a 12-month fixed-duration therapy generating durable remissions whereas BTKis are continuous treat-to-progression treatments.

OBJECTIVE:

To examine costs before and after the fixed-duration treatment period for VEN-O relative to that observed for BTKis in a national sample of older US adults with CLL in the frontline setting.

METHODS:

This retrospective analysis used Medicare Parts A, B, and D claims from 2016 to 2021. Fee-for-service Medicare beneficiaries aged 66 years or older initiating frontline CLL treatment with VEN-O or a BTKi treatment between June 1, 2019, and June 30, 2020 (index date = first prescription fill date), were included in the sample. Mean cost measures were captured for both groups over 2 fixed time periods calculated from the index date: Month 0 to 12 (proxy for VEN-O on-treatment period) and Month 13 to 18 (proxy for VEN-O off-treatment period). A difference-in-difference approach was used. Multivariate generalized linear models estimated changes in adjusted mean monthly costs during Month 0 to 12 vs Month 13 to 18, for the VEN-O group relative to the BTKi group.

RESULTS:

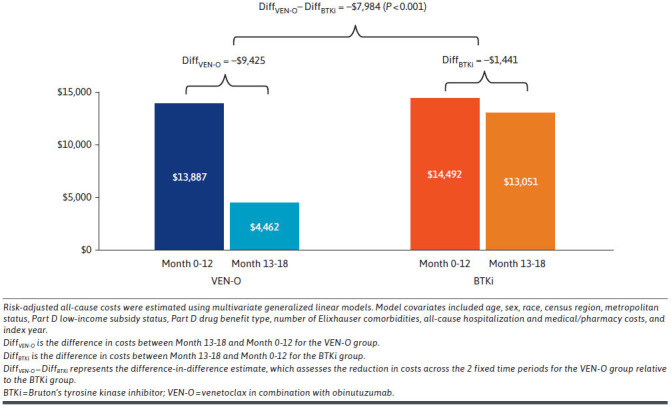

The final sample contained 193 beneficiaries treated with VEN-O and 1,577 beneficiaries treated with BTKis. Risk-adjusted all-cause monthly total costs were similar for VEN-O patients ($13,887) and BTKi patients ($14,492) between Month 0 and 12. Moreover, during Month 13 to 18, the mean monthly all-cause total costs declined by 67% for VEN-O ($13,887 to $4,462) but only by 10% for BTKi ($14,492 to $13,051). Hence, the relative reduction in costs across the 2 periods was significantly larger for VEN-O (−$9,425) vs BTKi (−$1,441) patients (ie, difference in difference = −$7,984; P < 0.001). Similar patterns were observed for CLL-related costs, with the substantially larger reductions in CLL-related total monthly costs (−$9,880 VEN-O vs −$1,753 BTKi; P < 0.001) for the VEN-O group primarily driven by the larger reduction in CLL-related monthly prescription costs (−$9,437 VEN-O vs −$2,020 BTKi; P < 0.001).

CONCLUSIONS:

This real-world study of older adults with CLL found a large reduction in monthly Medicare costs in the 6 months after completion of the fixed-duration treatment period of VEN-O, largely driven by the reduction in CLL-related prescription drug costs. A similar decline in costs was not observed among those treated with BTKis. Our study highlights the substantial economic benefits of fixed-duration VEN-O relative to treat-to-progression therapies like BTKis in the first-line CLL setting.

Plain language summary

Bruton’s tyrosine kinase inhibitors (BTKis) and the BCL-2 inhibitor venetoclax are both frontline treatment options in chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL). However, venetoclax is typically a fixed-duration therapy (12 months) whereas BTKis are taken continuously. Our study examined changes in health care costs before and after the fixed-duration treatment period for venetoclax relative to BTKis among US Medicare beneficiaries. We found that total costs in the 6 months after completion of the fixed-duration treatment period decreased by ~$8,000 per month for those treated with venetoclax compared with those treated with BTKis.

Implications for managed care pharmacy

In a highly competitive CLL treatment landscape, cost containment and formulary management pressures continue to demand greater value differentiation and real-world evidence to support health care decision-making. Our study found that in the 6 months after completion of the fixed-duration treatment period, monthly all-cause costs were approximately $8,000 per-patient per-month lower for Medicare beneficiaries receiving venetoclax-obinutuzumab compared with BTKis in frontline CLL. These findings highlight the substantial potential economic benefits of fixed treatment duration, an important consideration for payers and patients alike.

Chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) is a hematologic malignancy characterized by the clonal proliferation of mature B lymphocytes.1 CLL primarily affects individuals aged 65 years and older, and its prevalence rises significantly with advancing age.2 Although “watchful waiting” is often the standard of care for newly diagnosed patients, the clinical course can vary, and some older individuals may experience more aggressive forms of CLL requiring prompt intervention.3,4

The March 2016 US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approval of the first-generation oral Bruton’s tyrosine kinase inhibitor (BTKi) ibrutinib as a frontline therapy in CLL marked a major shift in the CLL treatment landscape.5 This was followed by approvals of next-generation BTKis such as acalabrutinib and zanubrutinib, with more BTKis still under development.6 Given improvements in survival relative to traditional chemoimmunotherapy regimens, BTKis have increasingly become a standard of care early in the CLL treatment pathway.7-9 However, a key limitation of these daily oral treatments is the need for continuous treatment until progression. This “treat-to-progression” paradigm of BTKis may not be ideal for older patients who may have greater treatment-related toxicities and may be more impacted by the financial burden of continuous treatment with high-cost cancer therapy.10,11

In contrast, the oral BCL-2 inhibitor venetoclax is typically given as a fixed-duration therapy and has been shown to generate deep and durable responses in CLL.8,11,12 As a result, venetoclax received approval in May 2019 to be given alongside obinutuzumab (VEN-O), an anti-CD20 antibody therapy, allowing for discontinuation after 12 months of therapy (obinutuzumab is only received for the first 6 months of treatment). Fixed-duration therapy with treatment-free remission is a particularly appealing aspect of VEN-O because it has the advantages of lowering health care costs by avoiding the need for continuous treatment. Clinical guidelines suggest that both VEN-O and BTKis are appropriate frontline treatment options in CLL.13

In addition to efficacy and tolerability, cost and value considerations may be important factors in the selection between fixed-duration venetoclax and continuous BTKi therapy. Recent studies from Canada and Denmark have estimated that venetoclax is more cost-effective than standard-of-care CLL treatments including ibrutinib.14,15 However, little real-world evidence has been generated to assess the potential economic benefits of a fixed-duration treatment regimen such as VEN-O relative to treat-to-progression therapies like BTKis. Critically, no studies have evaluated potential differences in health care costs between these treatment options in the US Medicare population. This gap in the literature is particularly problematic given (1) CLL is most prevalent among older adults, who primarily receive coverage through the Medicare program, and (2) the actual differences in cost between fixed-duration VEN-O and continuous BTKis has not been characterized. The objective of this study was to examine the reduction in costs before and after the expected fixed-duration treatment period for VEN-O relative to that observed for BTKis in a national sample of US Medicare beneficiaries aged 66 years or older with CLL in the frontline setting.

Methods

STUDY DESIGN AND DATA SOURCE

This was a retrospective cohort study using 2016-2021 Chronic Conditions Warehouse (CCW) 100% Medicare claims data available from the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS).16 The CCW data include comprehensive Medicare Part A and Part B claims for medical services such as inpatient and outpatient care and hospice services. Additionally, the CCW data include Medicare Part D prescription claims for all outpatient prescription drug events in the fee-for-service Medicare population; these claims capture the total cost of the prescription drug event and represent the price paid at the point of sale (ie, at the pharmacy), not including any rebates or manufacturer discounts. The Medicare claims files are linked to personal summary files, which capture patient sociodemographic characteristics and Medicare eligibility status.

SAMPLE SELECTION

The study sample consisted of patients with CLL newly initiating treatment with venetoclax plus obinutuzumab (ie, VEN-O group) or an available BTKi (ie, BTKi group) in the frontline setting between June 1, 2019, and June 30, 2020 (index date = first prescription fill date). Additional inclusion criteria for both groups included the following: (1) continuous fee-for-service Medicare Part A, B, and D coverage in the 36-month pre-index period and in the 12-month post-index period, (2) aged 67 years or older on index date, (3) at least 1 CLL diagnosis in the 12-month pre-index and post-index periods, (4) no evidence of at least 1 claim with a diagnosis of any other approved indication (ie, acute myeloid leukemia, mantle cell lymphoma, marginal zone lymphoma, Waldenström macroglobulinemia, or chronic graft vs host disease) for the index agent during the 12-month pre-index or post-index periods, (5) no evidence of prior CLL treatment in the 36-month pre-index period (except for anti-CD20s [obinutuzumab, rituximab, biosimilars] in the 4-week pre-index period), and (6) continuous fee-for-service medical and prescription coverage from 13 to 18 months after the index date or until death if it occurs earlier (to ensure each patient contributes costs for at least 1 month of the fixed time period of Months 13 to 18).

OUTCOMES

All outcomes for both study groups were measured over 2 fixed time periods calculated from the index date: Month 0 to 12 (ie, proxy for on-treatment period for VEN-O until its 12-month fixed-duration treatment was completed in the frontline setting) and Month 13 to 18 (ie, proxy for off-treatment period for VEN-O after fixed-duration treatment is completed in the frontline setting).

The study outcomes included all-cause and CLL-related health care costs during the 2 fixed time periods. All-cause total costs were identified based on all medical claims regardless of diagnosis and all medications regardless of indication. We also identified CLL-related total, medical, and prescription costs. CLL-related medical costs were identified based on medical service claims with a diagnosis code for CLL in any position on the claim. CLL-related prescription costs were identified based on drug claims for medications indicated for CLL. We reported costs separately for the CLL treatment prescriptions captured in the Part D prescription claims files (ie, CLL-related Part D drug costs) and the CLL infusion/injectable treatments administered by or under supervision of a physician and captured in the outpatient hospital or carrier claim files (ie, CLL-related Part B drug costs). We avoided double counting by excluding the CLL-related Part B drug costs from the reporting for the CLL-related medical costs. Finally, we also descriptively reported the patient out-of-pocket (OOP) costs for all Part D medications, CLL-related Part D medications, and the index agent (venetoclax or BTKi).

Cumulative costs were converted to mean monthly costs to permit standardized comparisons of the change in costs over time given the differing lengths of the 2 fixed time periods (12 months vs 6 months). Costs were inflated to 2022 US dollars using the medical care component of the 2022 US Consumer Price Index.17

ANALYSIS

Unadjusted cumulative and monthly all-cause and CLL-related health care costs were reported by fixed time periods (Month 0 to 12 and Month 13 to 18) for the 2 study groups. Risk-adjusted monthly costs were estimated using a 2-period difference-in-difference (DID) approach. Specifically, multivariate generalized linear models were used to estimate changes in monthly cost outcomes during Month 0 to 12 vs Month 13 to 18, for the VEN-O group relative to the BTKi group. Models included indicators for study group (VEN-O vs BTKi), time period (month 0 to 12 vs month 13 to 18), and an interaction term between study group and time period (ie, DID estimate). The regressions included control variables for age (66-69, 70-74, 75-79, 80+ years), sex (male, female), race (White, non-White), census region (Northeast, Midwest, South, West), metropolitan status (urban, rural), Part D low-income subsidy (LIS) status (full or partial LIS, non-LIS), Part D drug benefit type (basic alternative, enhanced alternative, defined standard benefit, other), number of Elixhauser comorbidities18 (≤2, 3-4, 5-7, 8-10, 11+), and index year (2019, 2020). Regressions also controlled for all-cause and CLL-related hospitalization and medical and pharmacy costs in the 12-month pre-index period where appropriate (for instance, the all-cause total cost regression controlled for pre-index all-cause hospitalization and all-cause medical and pharmacy costs).

The links for the generalized linear models were selected by use of the Pearson correlation test, the Pregibon link test, and the modified Hosmer-Lemeshow test, and the model families were selected by use of the modified Park test.19 Adjusted monthly cost estimates using the method of recycled predictions20 were produced for the key cost outcomes (all-cause and CLL-related monthly total costs, medical costs, and prescription costs) and the DID estimates were generated as follows. First, the difference or change in adjusted monthly costs between the 2 fixed time periods for the VEN-O group (DiffVEN-O) and the BTKi group (DiffBTKi) was reported. Next, by subtracting the difference in adjusted costs over the 2 time periods estimated for the BTKi group from the VEN-O group, we reported the adjusted DID (DiffVEN-O - DiffBTKi) estimate.

This study was deemed exempt from review by Pearl IRB according to FDA 21 CFR 56.104 and 45CFR46.104(b)(4): (4)Secondary Research Uses of Data or Specimens on 03/01/2021. A Waiver of Individual Authorization under HIPAA pursuant to 45 CFR 164.512 (i)(2)(i)-(v) exempt status as specified in 45 CFR 164.512 was approved.

Results

The final sample contained 193 patients in the VEN-O group and 1,577 patients in the BTKi group (Supplementary Table 1 (285.9KB, pdf) , available in online article). Compared with the BTKi group, the VEN-O group was slightly younger (mean age 75.6 years vs 77.6 years; P < 0.001) and more likely to be male (69.4% vs 55.8%; P < 0.001). However, patients in the VEN-O group had a higher comorbidity burden (57.5% vs 50.6% with ≥8 Elixhauser comorbidities in the 12-month pre-index period; P < 0.05) and higher rate of all-cause hospitalization (33.2% vs 24.7%; P < 0.05) in the 12-month pre-index period (Supplementary Table 2 (285.9KB, pdf) ). Whereas all patients in the VEN-O group were receiving venetoclax in combination with obinutuzumab, the majority (95.0%) of BTKi patients were receiving monotherapy. Additionally, most patients in the BTKi group (>87%) initiated treatment with ibrutinib (as opposed to acalabrutinib [12%] or zanubrutinib [<1%]).

Mean unadjusted all-cause and CLL-related cumulative and monthly health care costs over the 2 fixed time periods (Month 0 to 12 and Month 13 to 18) are presented in Table 1. Further breakdown of the costs in Month 0 to 2, Month 0 to 6, and Month 7 to 12 is provided in Supplementary Table 3 (285.9KB, pdf) . Prior to risk adjustment, mean all-cause total cumulative costs in the 12 months after initiation of treatment were similar for the VEN-O ($171,037) and BTKi groups ($173,361). In both groups, the majority (>90%) of costs were CLL-related. Between Month 0 and 12, cumulative CLL-related medical costs ($17,744 [VEN-O] vs $17,062 [BTKi]) and CLL-related prescription drug costs ($140,514 [VEN-O] vs $141,506 [BTKi]) were similar for both groups. However, within the cumulative CLL-related prescription costs between Month 0 and 12, the VEN-O group had lower cumulative CLL-related pharmacy costs ($99,639 [VEN-O] vs $137,950 [BTKi]) but higher CLL-related physician-administered drug costs ($40,875 [VEN-O] vs $3,556 [BTKi]) compared with the BTKi group. During Month 13 to 18, patients in the VEN-O group had substantially lower mean all-cause cumulative costs compared with the BTKi group ($27,085 [VEN-O] vs $74,702 [BTKi]) and thus experienced a greater relative reduction in costs across the 2 fixed time periods. This reduction was primarily driven by the large difference in mean cumulative CLL-related pharmacy costs ($12,413 [VEN-O] vs $56,428 [BTKi]).

TABLE 1.

Unadjusted All-Cause and CLL-Related Cumulative Health Care Costs by Time Period Among Medicare Beneficiaries Initiated on VEN-O vs BTKis in the Frontline Setting

| Cost measures | Cumulative costs | Monthly costs a | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| VEN-O | BTKi | VEN-O | BTKi | |||||

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | |

| All-cause total costs | ||||||||

| Month 0 to 12b | $171,037 | $55,445 | $173,361 | $60,988 | $14,253 | $4,620 | $14,447 | $5,082 |

| Month 13 to 18 | $27,085 | $33,749 | $74,702 | $42,250 | $4,861 | $6,679 | $13,007 | $8,209 |

| CLL-related total costs | ||||||||

| Month 0 to 12b | $158,258 | $52,880 | $158,568 | $58,711 | $13,188 | $4,407 | $13,214 | $4,893 |

| Month 13 to 18 | $18,216 | $28,869 | $66,021 | $40,009 | $3,234 | $5,329 | $11,434 | $7,574 |

| CLL-related medical costs | ||||||||

| Month 0 to 12b | $17,744 | $21,349 | $17,062 | $25,305 | $1,479 | $1,779 | $1,422 | $2,109 |

| Month 13 to 18 | $5,528 | $12,141 | $8,418 | $18,623 | $1,105 | $3,129 | $1,725 | $5,042 |

| CLL-related prescription drug costs | ||||||||

| Month 0 to 12b | $140,514 | $52,398 | $141,506 | $59,518 | $11,710 | $4,366 | $11,792 | $4,960 |

| Month 13 to 18 | $12,689 | $24,538 | $57,604 | $38,766 | $2,129 | $4,092 | $9,709 | $6,446 |

| CLL-related pharmacy costs (Part D drugs) | ||||||||

| Month 0 to 12b | $99,639 | $49,338 | $137,950 | $59,653 | $8,303 | $4,112 | $11,496 | $4,971 |

| Month 13 to 18 | $12,413 | $24,342 | $56,428 | $38,901 | $2,075 | $4,060 | $9,510 | $6,473 |

| CLL-related physician-administered drug costs (Part B drugs) | ||||||||

| Month 0 to 12b | $40,875 | $16,539 | $3,556 | $12,319 | $3,406 | $1,378 | $296 | $1,027 |

| Month 13 to 18 | $276 | $1,775 | $1,176 | $6,299 | $54 | $345 | $199 | $1,065 |

a For both the VEN-O and BTKi group, the mean number of person-months in Months 0-12 was 12 months and Month 13-18 was 5.9 months.

bFurther breakdown of the costs in Month 0 to 2, Month 0 to 6, and Month 7 to 12 is provided in Supplementary Table 3 (285.9KB, pdf) .

BTKi = Bruton’s tyrosine kinase inhibitor; CLL = chronic lymphocytic leukemia; VEN-O = venetoclax in combination with obinutuzumab.

Unadjusted all-cause and CLL-related monthly health care costs are also reported in Table 1 and exhibited a similar trend across the 2 fixed time periods. Before risk adjustment, mean monthly all-cause total costs for the VEN-O group were $14,253 in Month 0-12 and $4,861 in Month 13-18. Conversely, unadjusted mean monthly all-cause total costs for the BTK group were $14,447 in Month 0-12 and $13,007 in Month 13-18. Thus, patients in the VEN-O group experienced a $9,392 reduction compared with a $1,440 reduction in the BTKi group across the 2 fixed time periods. Similar results were observed for mean monthly CLL-related total costs, largely driven by the monthly CLL-related pharmacy costs. Correspondingly, greater relative reductions in monthly CLL-related OOP pharmacy costs across the 2 fixed time periods were observed for patients in the VEN-O group ($581 to $108 from Month 0-12 to Month 13-18) compared with the BTKi group ($703 to $492 from Month 0-12 to Month 13-18) (Supplementary Table 4 (285.9KB, pdf) ).

Risk-adjusted mean monthly all-cause total costs are presented in Figure 1. Between Month 0 and 12, risk-adjusted monthly all-cause total costs were similar for VEN-O patients ($13,887) and BTKi patients ($14,492). During Month 13 to 18, the monthly all-cause total costs declined by 67% for VEN-O patients (DiffVEN-O = -$9,425) but only by 10% for BTKi patients (DiffBTKi = -$1,441). This resulted in a DID (DiffVEN-O - DiffBTKi) between the VEN-O group and the BTKi group of -$7,894 (P < 0.001). The majority (>90% in Month 0-12) of mean monthly costs for patients in both the VEN-O and BTKi groups were CLL-related. Thus, a similar pattern was observed for CLL-related monthly total costs wherein the relative reduction across the 2 periods was significantly larger for VEN-O (DiffVEN-O = -$9,880) vs BTKi (DiffBTKi = -$1,753) patients (Figure 2). With respect to CLL-related medical costs, although there was a statistically significant DID (DiffVEN-O - DiffBTKi = -$710; P < 0.001) between VEN-O and BTKi groups, the difference was relatively small (Figure 3).

FIGURE 1.

Risk-Adjusted Mean Monthly All-Cause Total Costs by Time Period Among Medicare Beneficiaries Initiated on VEN-O vs BTKis in the Frontline Setting

FIGURE 2.

Risk-Adjusted Mean Monthly CLL-Related Total Costs by Time Period Among Medicare Beneficiaries Initiated on VEN-O vs BTKis in the Frontline Setting

FIGURE 3.

Risk-Adjusted Mean Monthly CLL-Related Medical Costs by Time Period Among Medicare Beneficiaries Initiated on VEN-O vs BTKis in the Frontline Setting

The difference in mean monthly costs between VEN-O and BTKi patients was primarily driven by the larger reduction in CLL-related monthly prescription costs (DiffVEN-O - DiffBTKi = -$7,417; P < 0.001) (Figure 4). The drop in mean monthly Part D prescription costs was more pronounced for the VEN-O group (DiffVEN-O = -$5,963) compared with the BTKi group (DiffBTKi = -$1,933). The VEN-O group ($3,524) had substantially higher mean monthly Part B drug costs in Month 0-12 than the BTKi group ($287); however, the Part B drug costs decreased substantially more for the VEN-O group in Month 13-18 (DiffVEN-O = -$3,474) than the BTKi group (DiffBTKi = -$87). In fact, in the post-treatment period, mean monthly Part B drug costs for the VEN-O group became much smaller ($50) than those for the BTKi group ($200). Thus, the DID estimate was substantial (DiffVEN-O - DiffBTKi = -$3,387; P < 0.001).

FIGURE 4.

Risk-Adjusted Mean Monthly CLL-Related Prescription Drug Costs by Time Period Among Medicare Beneficiaries Initiated on VEN-O vs BTKis in the Frontline Setting

Discussion

To our knowledge, this national study of older adults with CLL represents the first real-world evidence of the potential economic benefit of a fixed-duration venetoclax combination compared with treat-to-progression BTKis in the frontline setting. Our findings are particularly noteworthy given the shifting landscape of CLL treatment and ongoing discussions surrounding the relative merits of the fixed-duration vs treat-to-progression treatment paradigms.10,21

Although venetoclax is often assumed to have higher overall medical costs owing to the need for tumor lysis syndrome monitoring22 during the ramp-up phase (including metabolic testing and potentially inpatient hospitalization) and concomitant treatment with obinutuzumab for the first 6 months,23 our study revealed that in the first 12 months after treatment initiation, patients receiving VEN-O and BTKis actually have similar mean cumulative (~$170,000) and mean monthly (~$14,000) all-cause health care costs (despite having a larger comorbidity burden and higher rate of hospitalization prior to initiating treatment). We found that during Month 0 to 12, the CLL-related physician-administered drug costs (ie, Part B drug costs) were higher for the VEN-O group owing to the concurrent receipt of obinutuzumab, but these costs were offset by the higher CLL-related pharmacy costs (ie, Part D drug costs) in the BTKi group. Hence, CLL-related prescription drug costs were similar for both groups in the first 12 months after treatment initiation. Risk adjustment confirmed these findings, illustrating slightly lower CLL-related total monthly costs for the VEN-O group during Month 0 to 12.

Between Month 13 and 18, however, the 2 groups diverged significantly with respect to health care costs. Across the 2 fixed time periods, we observed a much larger and statistically significant reduction in all-cause mean monthly health care costs in the VEN-O group after completion of the fixed-duration treatment period of 12 months. This drop in mean monthly costs was driven by the reduction in CLL-related prescription drug costs, consistent with the fixed-duration nature of VEN-O and its potential for generating deep and long-lasting responses. A similar decline in monthly health care costs was not observed in the BTKi group, consistent with the treat-to-progression paradigm. Hence, overall costs for the BTKi group were approximately $8,000 per-patient per-month higher than the VEN-O group after the 12-month fixed-duration treatment period.

These findings are meaningful in several respects. Although previous modeling studies have demonstrated the overall cost-effectiveness of VEN-O compared with both chemoimmunotherapy and BTKi treatment in the frontline setting,14 our study is the first to use real-world data to provide empirical evidence confirming economic benefit offered by the fixed-duration nature of venetoclax treatment. Given that costs were similar for both the VEN-O group and BTKi groups in the first 12 months after treatment initiation, payers should be aware that a long-term view of treatment costs will be necessary in order to fully reap the potential economic benefits of effective fixed-duration treatments such as venetoclax. Although our study was limited to only 18 months of follow-up from the index date, BTKis are meant to be taken continuously, with a previous cost-effectiveness analysis from a Medicare perspective showing that total health care costs among patients treated with ibrutinib can be as high as $455,000 (in 2017 US dollars) over a patient’s lifetime.24 Additionally, patients treated with BTKis will often require subsequent CLL treatment with other targeted therapies, which will continue to incur costs. A prior real-world study of patients with CLL who discontinued BTKi treatment found that over a median follow-up of 6 years, subsequent treatments were observed in 74% of discontinuers.25 Conversely, previous work has shown that a majority (65%) of patients treated with venetoclax did not require subsequent CLL treatment over a median 5 years after completing their fixed-duration therapy.26

It is worth noting that as part of the implementation of the Inflation Reduction Act of 2022, ibrutinib was one of the 10 therapies selected by CMS for the first year of the Medicare drug price negotiation program with negotiated prices going into effect starting January 1, 2026.27 Depending on the price reduction negotiated for ibrutinib, the costs in the first 12 months may be lower for ibrutinib initiators compared with VEN-O users. However, as discussed above, our results suggest that a long-term economic outlook is required by payers when comparing the cost-effectiveness of these 2 treatments given the long natural history of CLL. A reduced drug price for ibrutinib may not fully address the continuous costs that payers will incur with treat-to-progression BTKis vs the time-limited costs of fixed-duration treatments like venetoclax. Similarly, our results on the observed OOP costs across the 2 fixed time periods also support this idea from the patient perspective: VEN-O users experience a much steeper decline in observed OOP costs once they complete the fixed-duration treatment period, whereas BTKi users continue to incur OOP costs, a scenario that will not change even if ibrutinib’s price is reduced.

Our findings are also worth considering in light of ongoing development of next-generation BTKis (acalabrutinib, zanubrutinib) and new venetoclax regimens (venetoclax + BTKi). Most patients in our study initiated ibrutinib rather than a newer BTKi treatment, and thus, it will be important to repeat this study as more data become available for acalabrutinib and zanubrutinib. Although newer second-generation BTKis, such as acalabrutinib, may offer an improved safety profile relative to the first-generation agent ibrutinib, adverse events such as bleeding and infection are still a concern.28 Despite the potential for tumor lysis syndrome and cytopenias, venetoclax is generally well tolerated, and a prior study suggests that venetoclax-treated patients may be less likely to discontinue because of adverse events compared with those receiving BTKi-based regimens.29 The cost of treatment-related adverse events will work against the potential economic benefit of next-generation BTKis, as will their treat-to-progression paradigm that incurs ongoing costs. Recently, venetoclax combined with ibrutinib in a fixed-duration regimen has been shown to be effective for high-risk and older adults with CLL in the frontline setting.30 Future research should compare fixed-duration VEN-O, fixed-duration venetoclax plus BTKi, and BTKi monotherapy to assess the relative economic benefits of these regimens.

LIMITATIONS

Our study had several limitations worth noting. First, the vast majority of patients in our BTKi group were receiving ibrutinib, which is currently undergoing Medicare drug price negotiation as of 2024. Hence, the overall costs of BTKi treatment (and OOP costs faced by patients) will likely be lower in the future once the negotiated price goes into effect on January 1, 2026. However, as we noted previously, the reduced price still must be paid indefinitely while on continuous BTKi treatment whereas patients treated with fixed-duration venetoclax will stop incurring costs after 12 months. Second, our claims-based analysis did not capture indirect costs or humanistic outcomes of VEN-O vs BTKi treatment. Third, our analysis did not determine whether the costs differed across subgroups. Fourth, our study is generalizable only to the fee-for-service Medicare population. Fifth, the available follow-up (ie, through December 31, 2021) also limited our ability to study long-term persistence of the economic benefit of VEN-O beyond the first 6 months after presumed treatment completion. Finally, there may be systematic differences between patients receiving VEN-O and the BTKi comparison group in our real-world observational study that could bias our results. However, our multivariate analysis using a DID approach controlled for not only all observed confounders but also unobserved time-invariant differences between the 2 study groups.

Conclusions

This real-world study of Medicare beneficiaries with CLL in the frontline setting found a large reduction in mean monthly all-cause health care costs in the venetoclax group after the fixed-duration treatment period of 12 months. This drop was largely driven by the reduction in CLL-related prescription drug costs. Similar declines in cost were not observed in Medicare CLL beneficiaries receiving first-line BTKi. Hence, the monthly all-cause costs for patients treated with VEN-O after the fixed-duration treatment period were approximately $8,000 per-patient per-month lower than the BTKi group. Our study highlights the substantial potential economic benefits of fixed-duration treatment with VEN-O for first-line CLL relative to treat-to-progression therapies like BTKis.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Data sharing statement: AbbVie is committed to responsible data sharing regarding the clinical trials we sponsor. This includes access to anonymized, individual, and trial-level data (analysis data sets), as well as other information (eg, protocols, clinical study reports, or analysis plans), as long as the trials are not part of an ongoing or planned regulatory submission. This includes requests for clinical trial data for unlicensed products and indications.

These clinical trial data can be requested by any qualified researchers who engage in rigorous, independent, scientific research and will be provided following review and approval of a research proposal, Statistical Analysis Plan (SAP), and execution of a Data Sharing Agreement (DSA). Data requests can be submitted at any time after approval in the United States and Europe and after acceptance of this manuscript for publication. The data will be accessible for 12 months, with possible extensions considered. For more information on the process or to submit a request, visit the following link https://vivli.org/ourmember/abbvie/ and then select “Home.”

Funding Statement

AbbVie and Genentech funded this real-world study and participated in the study design, interpretation of data, and the review and approval of the publication. AbbVie/Genentech were not involved in the analysis of data. All authors participated in the drafting, review, and approval of this publication. No honoraria or payments were made for authorship.

REFERENCES

- 1.Hallek M, Al-Sawaf O. Chronic lymphocytic leukemia: 2022 update on diagnostic and therapeutic procedures. Am J Hematol. 2021;96(12):1679-705. doi:10.1002/ajh.26367 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Stauder R, Eichhorst B, Hamaker ME, et al. Management of chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) in the elderly: a position paper from an international Society of Geriatric Oncology (SIOG) Task Force. Ann Oncol. 2017;28(2):218-27. doi:10.1093/annonc/mdw547 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Stilgenbauer S. Prognostic markers and standard management of chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Hematology (Am Soc Hematol Educ Program). 2015;2015(1):368-77. doi:10.1182/asheducation-2015.1.368 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ghia P, Hallek M. Management of chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Haematologica. 2014;99(6):965-72. doi:10.3324/haematol.2013.096107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Iovino L, Shadman M. Novel therapies in chronic lymphocytic leukemia: A rapidly changing landscape. Curr Treat Options Oncol. 2020;21(4):24. doi:10.1007/s11864-020-0715-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Frustaci AM, Deodato M, Zamprogna G, Cairoli R, Montillo M, Tedeschi A. Next generation BTK inhibitors in CLL: Evolving challenges and new opportunities. Cancers (Basel). 2023;15(5):1504. doi:10.3390/cancers15051504 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Robak T, Witkowska M, Smolewski P. The role of Bruton’s kinase inhibitors in chronic lymphocytic leukemia: Current status and future directions. Cancers (Basel). 2022;14(3):771. doi:10.3390/cancers14030771 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Small S, Ma S. Frontline treatment for chronic lymphocytic leukemia/small lymphocytic lymphoma (CLL/SLL): Targeted therapy vs. chemoimmunotherapy. Curr Hematol Malig Rep. 2021;16(4):325-35. doi:10.1007/s11899-021-00637-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Woyach JA, Ruppert AS, Heerema NA, et al. Ibrutinib regimens versus chemoimmunotherapy in older patients with untreated CLL. N Engl J Med. 2018;379(26):2517-28. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1812836 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Swaminathan M. Is Fixed-Duration Therapy the New Standard of Care in Frontline Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia? Targeted Oncology. Published September 7, 2023. Accessed November 17, 2023. https://www.targetedonc.com/view/is-fixed-duration-therapy-the-new-standard-of-care-in-frontline-chronic-lymphocytic-leukemia- [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lévy V, Delmer A, Cymbalista F. Frontline treatment in CLL: The case for time-limited treatment. Hematology (Am Soc Hematol Educ Program). 2021;2021(1):59-67. doi:10.1182/hematology.2021000233 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Eyre TA, Hori S, Munir T. Treatment strategies for a rapidly evolving landscape in chronic lymphocytic leukemia management. Hematol Oncol. 2022;40(2):129-59. doi:10.1002/hon.2943 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.National Comprehensive Cancer Network. Treatment Guidelines by Cancer Type. NCCN. Accessed May 24, 2023. https://www.nccn.org/guidelines/category_1

- 14.Chatterjee A, van de Wetering G, Goeree R, et al. A probabilistic cost-effectiveness analysis of venetoclax and obinutuzumab as a first-line therapy in chronic lymphocytic leukemia in Canada. PharmacoEconom Open. 2023;7(2):199-216. doi:10.1007/s41669-022-00375-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Slot M, Niemann CU, Ehlers LH, Rotbain EC. Cost-effectiveness of targeted treatment vs chemoimmunotherapy in treatment-naive unfit CLL without TP53 aberrations. Blood Adv. 2023;7(15):4186-96. doi:10.1182/bloodadvances.2023010108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. About the Chronic Conditions Warehouse. Chronic Conditions Data Warehouse. Accessed May 10, 2024. https://www2.ccwdata.org/about-ccw

- 17.U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. Consumer Price Indexes Overview. Bureau of Labor Statistics. Accessed May 10, 2024. https://www.bls.gov/cpi/overview.htm

- 18.Elixhauser A, Steiner C, Harris DR, Coffey RM. Comorbidity measures for use with administrative data. Med Care. 1998;36(1):8-27. doi:10.1097/00005650-199801000-00004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Glick HA, Doshi JA, Sonnad S, Polsky D, eds. Economic Evaluation in Clinical Trials. 2nd ed. Oxford University Press; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Li Z, Mahendra G. Using “Recycled Predictions” for Computing Marginal Effects. SAS Global Forum; 2010. Accessed May 10, 2024. https://support.sas.com/resources/papers/proceedings10/272-2010.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 21.Brander D, Islam P, Barrientos JC. Tailored treatment strategies for chronic lymphocytic leukemia in a rapidly changing era. Am Soc Clin Oncol Educ Book. 2019;39:487-98. doi:10.1200/EDBK_238735 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fischer K, Al-Sawaf O, Hallek M. Preventing and monitoring for tumor lysis syndrome and other toxicities of venetoclax during treatment of chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Hematology (Am Soc Hematol Educ Program). 2020;2020(1):357-62. doi:10.1182/hematology.2020000120 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rogers KA, Emond B, Manceur AM, et al. Real-world treatment sequencing and healthcare costs among CLL/SLL patients treated with venetoclax. Curr Med Res Opin. 2021;37(8):1409-20. doi:10.1080/03007995.2021.1929894 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Barnes JI, Divi V, Begaye A, et al. Cost-effectiveness of ibrutinib as first-line therapy for chronic lymphocytic leukemia in older adults without deletion 17p. Blood Adv. 2018;2(15):1946-56. doi:10.1182/bloodadvances.2017015461 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lin KH, Huynh L, Yang X, et al. Real-world evidence study of treatment patterns and outcomes following covalent BTKi discontinuation in a contemporary cohort of chronic lymphocytic leukemia/small lymphocytic lymphoma (CLL/SLL) patients. J Clin Oncol. 2023;41(suppl 16):e19510. doi:10.1200/JCO.2023.41.16_suppl.e19510 [Google Scholar]

- 26.Al-Sawaf O, Robrecht S, Zhang C, et al. Venetoclax-obinutuzumab for previously untreated chronic lymphocytic leukemia: 6-year results of the randomized CLL14 study. HemaSphere. 2023;7(suppl 3):e064430a. doi:10.1097/01.HS9.0000967492.06443.0a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Raymakers AJN, Kesselheim AS, Rome BN. Medicare price negotiation: The example of ibrutinib. Accessed May 10, 2024. https://www.healthaffairs.org/content/forefront/medicare-price-negotiation-under-inflation-reduction-act-example-ibrutinib [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wang JF, Hwang SR, Jiang Y, et al. Comparison of treatment-emergent adverse events of covalent BTK inhibitors in clinical trials in B-cell malignancies: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Blood. 2022;140(suppl 1):9882-4. doi:10.1182/blood-2022-168152 [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shadman M, Manzoor BS, Sail K, et al. Treatment discontinuation patterns for patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia in real-world settings: Results from a multi-center international study. Clin Lymphoma Myeloma Leuk. 2023;23(7):515-26. doi:10.1016/j.clml.2023.03.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jain N, Keating M, Thompson P, et al. Ibrutinib and venetoclax for first-line treatment of CLL. N Engl J Med. 2019;380(22):2095-103. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1900574 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]