Bifunctional catalyst blend is active in hydrocracking of plastic waste to valuable fuels and lubricants with high yields.

Abstract

Single-use plastics impose an enormous environmental threat, but their recycling, especially of polyolefins, has been proven challenging. We report a direct method to selectively convert polyolefins to branched, liquid fuels including diesel, jet, and gasoline-range hydrocarbons, with high yield up to 85% over Pt/WO3/ZrO2 and HY zeolite in hydrogen at temperatures as low as 225°C. The process proceeds via tandem catalysis with initial activation of the polymer primarily over Pt, with subsequent cracking over the acid sites of WO3/ZrO2 and HY zeolite, isomerization over WO3/ZrO2 sites, and hydrogenation of olefin intermediates over Pt. The process can be tuned to convert different common plastic wastes, including low- and high-density polyethylene, polypropylene, polystyrene, everyday polyethylene bottles and bags, and composite plastics to desirable fuels and light lubricants.

INTRODUCTION

Plastics are an indispensable part of modern life. Global plastic production reached 314 million tons in 2014 and is projected to increase to over 1200 million tons by 2050 (1, 2). This growth is alarming when considering the current plastic waste management. In the United States, >75% of plastics are disposed in landfills and < 16% are incinerated, and only <9% are recycled (3, 4). Unrecycled plastics generate large economic loss and emissions and harm the environment (2, 4–7). Current repurposing routes, such as mechanical processing, require substantial amounts of virgin material and lead to lower-value products. Chemical conversion is the most versatile and robust approach to combat plastics waste. Figure 1 depicts various existing approaches to fuel-range hydrocarbons. Thermal or catalytic pyrolysis alone at 400° to 600°C or pyrolysis followed by catalytic hydrotreatment has been exploited (Fig. 1) (8–13). Over SiO2-Al2O3 and zeolites, e.g., HY and HZSM-5 (14–19), the selectivity to monomers, gasoline-range hydrocarbons (20, 21), or diesel is low (22). Instead, undesired high fractions of light C1-C4 hydrocarbons, tar, and coke form (13). High temperatures are required to cleave the resilient C─C bonds, especially of polyethylene (PE) and polypropylene (PP), which give polymers their mechanical stability. High temperatures require significant energy and lead to low selectivity of valuable products (23).

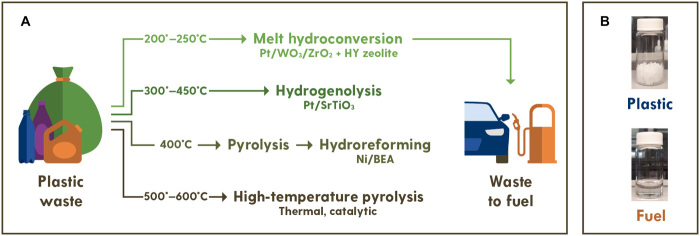

Fig. 1. Current and proposed chemical conversion of plastic-waste to fuels.

(A) Polyolefin pyrolysis (23) and hydrogenolysis (28) require harsh reaction conditions and produce low amounts of fuel-range hydrocarbons. The proposed approach exhibits a high yield to gasoline at low temperatures without solvents or diluents. (B) Initial chopped PE bag before reaction and liquid product after reaction. Photo credit: Pavel Kots, University of Delaware.

Recently, several reports highlighted the potential of metal-catalyzed hydrogenolysis for PE breakdown (24–26). Wax and lubricant-range hydrocarbons were produced over a Pt/SrTiO3 catalyst at 300°C, 96 hours with a yield of 42 to 97% depending on the PE material (24). Pt/SiO2 catalyst covered with a mesoporous SiO2 shell showed ca. 38% yield of diesel from high-density PE (HDPE) in 24 hours at 250°C and 13.8-bar H2 (25). Hydrogenolysis coupled with Pt-catalyzed aromatization was used to convert PE to long-chain alkyl aromatics without external H2 (26). Because noble metal catalysts could not catalyze carbon backbone isomerization, most of these products are probably solid at room temperature and unsuitable for many applications because of the lack of chain branching. Also, hydrogenolysis requires relatively long reaction times and high temperatures, as well as high catalyst-to-plastic ratios. Hydrocracking over bifunctional metal/acid catalysts is an attractive option, as the acid catalyst can crack C─C bonds and the metal catalyst can hydrogenate the intermediates and eliminate catalyst coking. However, only a limited number of works have been reported using this technology. Ni-, Co-, and Pt-based catalysts, combined with zeolites, exhibit unselective hydrocracking to gas products at temperatures higher than 330°C (27–30). To date, available methods do not meet practical implementation because of relatively low yield, long processing times, high temperatures and high energy demand, and the inability to tune product distribution for different applications. The development of a catalytic technology that is tunable, low-temperature, energy-efficient, and mixed-feedstock-agnostic can revolutionize the economical (re)use of commodity plastics while substantially reducing the environmental footprint of modern plastics.

We found that nanoparticle platinum deposited on tungstate-zirconia Pt/WO3/ZrO2 (characterization data provided in fig. S1 and table S1) mixed with FAU-type zeolite (HY) is a very active and selective catalyst for mild hydrocracking in the melt of low-density PE (LDPE) producing a mixture of gasoline, diesel, and jet-range hydrocarbons. A maximum liquid yield of 85% was attained at a low temperature of 250°C and 30-bar H2 in 2 hours. The synergy of catalysts is crucial in achieving high liquid yields at low temperature with minimal to no solid, as compared to a previous study (30). The balance between acid and metal sites is essential for fast polymer conversion via a bifunctional tandem catalysis, compared to the slower monofunctional hydrogenolysis (24, 25). The catalyst can be engineered in multiple ways to tune product distribution. The catalyst is active in converting the most abundant plastic waste components, including HDPE, PP, polystyrene (PS), layered PP-PE-PS composites, and everyday plastic bags, bottles, etc.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Pt/WO3/ZrO2 alone shows low activity for LDPE conversion in the melt phase at 250°C, giving linear and branched alkanes (an average of 9 and 91%, respectively) (Fig. 2, A and B, and figs. S2 and S3) with a broad carbon number distribution centered at ca. C10. Chain branching of hydrocarbons, occurring over Pt/WO3/ZrO2, is essential to impart suitable properties, such as low melting point and pour point, for everyday fuels and lubricants. Diesel-range hydrocarbons are attained at a relatively high yield of 35% after 12 hours with ca. 21% of solid residue, probably wax (fig. S3). Mechanically blending HY(30) zeolite with Pt/WO3/ZrO2 substantially increases the catalyst activity with only 7% unconverted solid residue after 2 hours (Fig. 2A). Furthermore, the product distribution becomes narrower and shifts to gasoline-range hydrocarbons (Fig. 2B and fig. S3). Pure HY(30) zeolite, under the same reaction conditions, shows very little LDPE conversion with extensive coking, leading to 91% solid residue (Fig. 2A). The results suggest a strong synergy between Pt/WO3/ZrO2 and HY(30) zeolite (Fig. 2E). Initially, the polymer undergoes hydrocracking over Pt/WO3/ZrO2 into relatively large olefins or alkanes. These intermediates diffuse into HY zeolite acid sites, where they crack relatively quickly into smaller C5–7 alkenes because of the microporous network’s shape selectivity. At the same time, the cracking of or corresponding alkanes over Pt/WO3/ZrO2 is slower because of a lower concentration of weaker acid sites and the absence of shape selectivity. A separate experiment with n-C26 alkane as a substrate revealed similar product distribution (fig. S3), indicating that high alkanes and olefins are potential reaction intermediates.

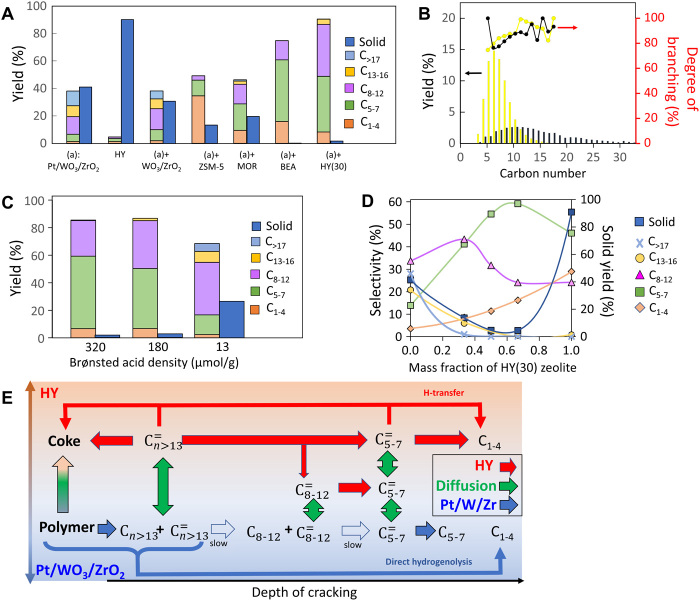

Fig. 2. Catalytic data at 250°C.

(A) Depolymerization of LDPE over Pt/WO3/ZrO2 with various solid acid catalysts for 2 hours. (B) Product yields and degree of isomerization by carbon number for pure Pt/WO3/ZrO2 (black) and Pt/WO3/ZrO2 mixed with HY(30) in a 1:1 mass ratio (yellow). (C) Influence of HY zeolite acidity on product yields in LDPE hydrocracking in a 1:1 mixture with Pt/WO3/ZrO2 for 4 hours. (D) Effect of the HY(30) zeolite mass fraction in a mixture with Pt/WO3/ZrO2 on the selectivity of the main product groups and solid yield for 2 hours. (E) Reaction network highlighting the role of the HY zeolite in accelerating deep cracking.

The acidity of the HY zeolite plays an important role in the overall performance and selectivity of the reaction (Fig. 2C, fig. S3, and table S2). Decreasing the Al content in the HY zeolite results in a decrease of the gasoline (C5–12) yield from 72 to 32% and an increase of the diesel (C9–22) yield from 11 to 27%. At the same time, the yield of solid residue over HY zeolites of low acid site density increases. Fourier transform infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy of adsorbed pyridine shows a correlation between strong Brønsted acid site content and catalyst activity, typical for cracking reactions of hydrocarbons (table S2). Thus, zeolite acidity can significantly affect the consumption of intermediates produced by Pt/WO3/ZrO2 (Fig. 2E). This mainly leads to a slowdown of the initial polymer proceeding with a shift in selectivity toward heavier hydrocarbons. Acidity is an essential knob for tuning product distribution from gasoline-range alkanes, at lower Si/Al ratios, to larger–molecular weight jet and diesel fuel-range alkanes, at higher Si/Al ratios.

Experiments over several microporous acid catalysts indicate that the LDPE conversion follows the order of the pore size, HY~HBEA > H-MOR > HZSM-5 (Fig. 2A and Table 1). The product distribution reflects shape-selective catalysis during hydrocracking; HY favors a gasoline-range product and HZSM-5 C1–4 gas products. HBEA gives higher gas products than HY. Shape selectivity arises primarily from slower diffusion of reaction intermediates in zeolites with narrower pores, leading to their secondary cracking to smaller products. Given that HY(30) provides the highest LDPE conversion and maximum yield to gasoline-range hydrocarbons among HY zeolites, it was selected for follow-up studies.

Table 1. Catalytic properties of different solid acids mixed with Pt/WO3/ZrO2 in LDPE hydroconversion.

Reaction conditions: 250°C, 30-bar H2, 2.0-g LDPE, 0.1-g Pt/WO3/ZrO2, 0.1-g solid acid, and reaction time of 2 hours [except for data in “*,” which was conducted for 12 hours)].

| Solid acid | Si/Al ratio |

Yield of

solid (%) |

Selectivity (%) |

Yield of

gasoline (C5–12) (%) |

Yield of

diesel (C9–22) (%) |

||||

| C1–4 | C5–7 | C8–12 | C13–16 | C>17 | |||||

| Zeolites | |||||||||

| HZSM-5 | 11.5 | 13 | 70 | 23 | 6 | 0 | 0 | 13 | 1 |

| HMOR | 10.0 | 20 | 21 | 42 | 31 | 5 | 2 | 32 | 12 |

| HBEA | 13 | 0 | 21 | 60 | 19 | 0 | 0 | 57 | 6 |

| HY(30) | 16 | 6 | 9 | 52 | 29 | 2 | 0 | 73 | 20 |

| Other solid acids | |||||||||

| Al-MCM-41 | 39.5 | 68 | 9 | 28 | 42 | 16 | 5 | 11 | 9 |

| WO3/ZrO2 | – | 31 | 5 | 21 | 40 | 19 | 15 | 23 | 23 |

| Al-MCM-41* | 40 | 3 | 6 | 28 | 39 | 15 | 11 | 57 | 45 |

| WO3/ZrO2* | – | 3 | 3 | 15 | 47 | 22 | 13 | 56 | 59 |

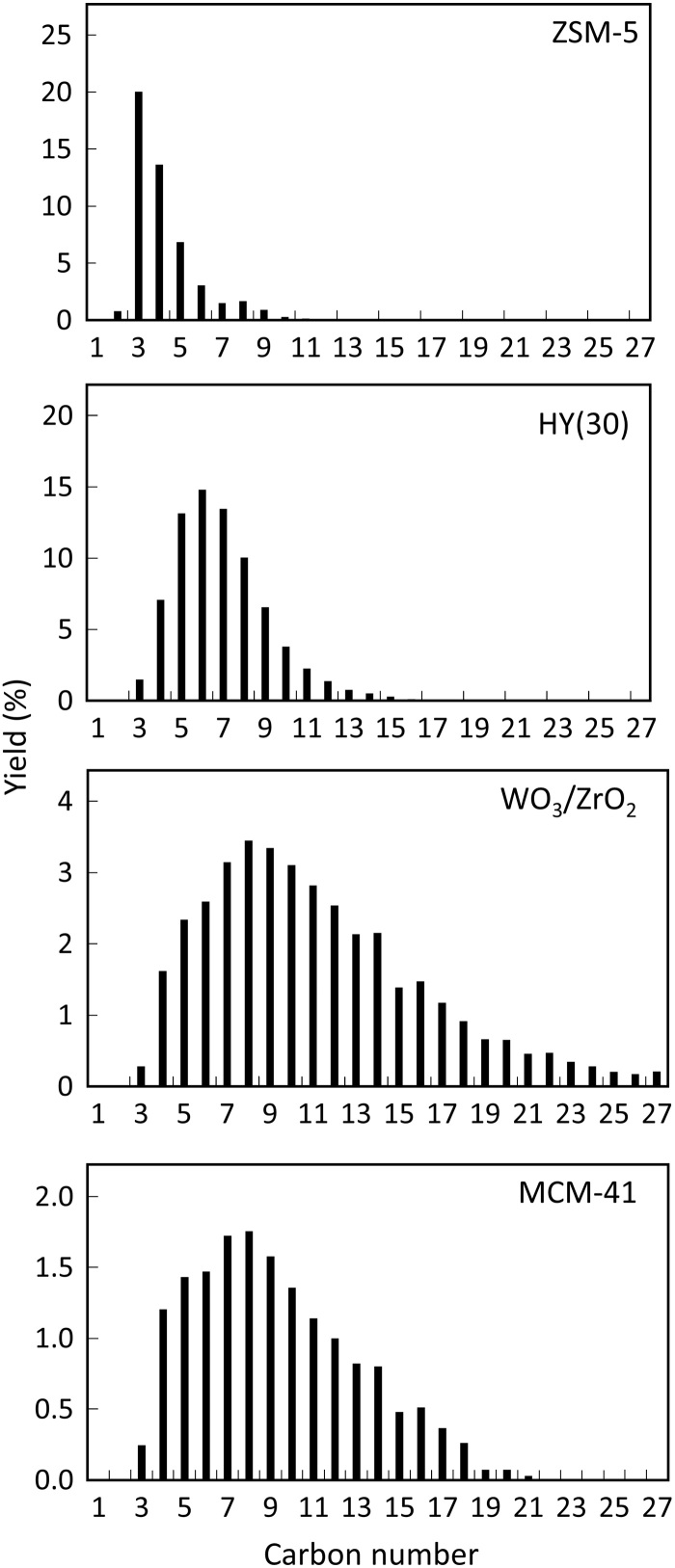

Other solid acid catalysts, such as WO3/ZrO2 (Fig. 2A and Table 1) and mesoporous Al-MCM-41, blended with Pt/WO3/ZrO2 exhibit lower conversion than the Pt/WO3/ZrO2 + HY(30) blend. The product distribution in terms of carbon number (Fig. 3) can be tuned by changing the characteristics of the acid catalyst, such as the acid site strength and the pore size or shape, with nonmicroporous materials giving rise to heavier fuels. This trend persists with longer reaction time, leading to high LDPE conversion over both Al-MCM-41 and WO3/ZrO2 (Table 1). Specifically, Pt/WO3/ZrO2 + HY(30) gives gasoline-range products (C5–12) with ca. 72% yield in a single step, higher than the best reported yield (55%) achieved in two steps, i.e., thermal cracking of LDPE and hydrotreatment of the obtained oil over Ni/meso-BEA catalysts (31). The jet/diesel fuel (C8–22 alkanes) yield is 54 and 73% using Al-MCM-41 and WO3/ZrO2 acid catalysts in 12 hours at 250°C, respectively (Table 1).

Fig. 3. Product yield distribution by carbon number over Pt/WO3/ZrO2 mixed with different solid acids.

Reaction conditions: 250°C, 30-bar H2, 2.0-g LDPE, 0.1-g Pt/WO3/ZrO2, 0.1-g solid acid, and reaction time of 2 hours.

The possibility of converting plastic waste to various types of motor fuels or lubricant base oils can add vital flexibility and increase economic feasibility of future plastic-waste conversion plants. Engineering the zeolite acidity and porosity can be a way to tune the product distribution. We prepared mesoporous HY zeolite via desilication by varying the NaOH solution concentration. The results reveal a complex effect of desilication on performance (table S2 and figs. S4 and S5). As the NaOH concentration increases, the yield to gasoline products goes through a maximum, and the yield to jet/diesel-range products and solids increases. This behavior is probably due to the interplay of increased diffusion in the mesopores (fig. S5), weaker acidity, and lower crystallinity (table S2) induced by more concentrated NaOH solutions. Samples with a high degree of desilication showed an appreciable increase in yields to light lubricant range (C13–25) hydrocarbons (32) from 0.4 to 12% at the expense of diesel (fig. S4). The combined enhanced acid site accessibility of the mesoporous HY framework and the decrease in acid site strength lead to the observed product distribution. The tendency of HY zeolite to crack C>13 hydrocarbons to small C5–7 products (Fig. 2E) can be reversed more effectively by engineering additional mesoporosity and reducing the impact of microporous confinement on product selectivity.

Experiments over catalyst blends of varying composition further confirm the synergy between the two catalysts (Fig. 2D). Pt/WO3/ZrO2 forms C>17 compounds as well as C13–16 and C8–12 molecules with slight deep cracking to C5–7 and C1–4 gases but is incapable of complete conversion of the plastic at mild conditions and short reaction times. This catalyst is likely responsible for the initiation steps in the reaction network by converting large paraffins to large olefins (33). The HY zeolite preferentially cracks the C>17 and C13–16 compounds formed over the Pt/WO3/ZrO2 at first to C8–12, then to smaller C5–7 hydrocarbons, and eventually to C1–4 light gases as its fraction in the catalyst blend increases (Fig. 2D). These C8–12 and C5–7 compounds are subjected to over cracking by the HY zeolite with modest contributions from hydrogenolysis over Pt nanoparticles (34). The same pattern is visible on time-dependent product distributions by carbon number (fig. S6). Almost no Cn>23 products are present in the liquid even after 0.5 hours of reaction time, despite the fact that both gas chromatography (GC) and GC–mass spectrometry (GC-MS) were calibrated with up to n-C37. Heavy reaction products Cn>23 have small solubility in cold CH2Cl2, and thus, we cannot conclusively infer larger fractions. Furthermore, the lack of heavier products could indicate that polymer cracking proceeds with one chain adsorbed and reacting until being completely consumed without releasing medium-sized products. The similar melting points of the solid residues at various reaction times corroborate with this point (fig. S7).

HY up to ca. 60 weight % (wt %) results in nearly complete plastic conversion, which is essential for practical implementation of a catalytic technology. Because of low activity of pure HY zeolite at 250°C, the metal particles likely hydrogenate coke precursors, keeping the zeolite catalyst active. Intermediate olefins are not observed in the product mixture, because of the shift in the hydrogenation/dehydrogenation equilibrium toward alkanes at moderate reaction temperatures (33).

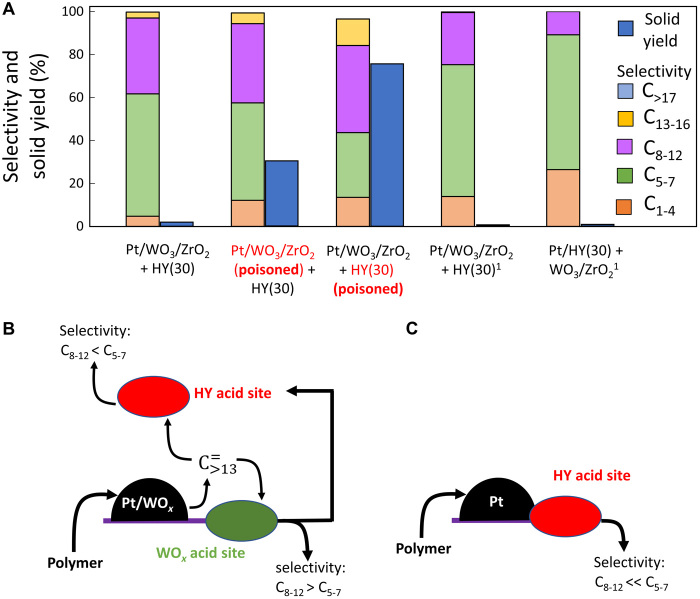

Poisoning of acid sites of Pt/WO3/ZrO2 with pyridine does not lead to significant changes in selectivity, while the residual solid yield increases from 1.9 to 30.6% (Fig. 4A). When poisoned HY(30) zeolite is used together with fresh Pt/WO3/ZrO2, the activity decreases even more, resulting in 76.1% solid yield. At the same time, poisoning of the zeolite increases the selectivity to higher–molecular weight products. These data show that the zeolite is a major contributor to the activity of the catalyst blend and to shifting the selectivity to lighter products. In an attempt to compare activities of both catalysts, the amount of irreversibly bonded pyridine during poisoning was counted by thermogravimetric analysis (TGA) in the flow of air. The results show that Pt/WO3/ZrO2 and HY(30) retain pyridine (60 and 410 μmol/g, respectively). This observation is in line with Brønsted acid sites concentrations measured over these samples (tables S1 and S2). The large difference in acid site concentration could be at least partially responsible for the remarkable differences in solid yields.

Fig. 4. Selective poisoning of Pt/WO3/ZrO2.

(A) Effect of selective poisoning of Pt/WO3/ZrO2 or HY(30) zeolite by pyridine on reaction performance. Conditions: 275°C, 1 hour, and 30-bar H2. Data marked with 1 are collected at 250°C, 4 hours of reaction time. (B) Depiction of main intermediates diffusing over Pt/WO3/ZrO2 + HY(30) catalyst. (C) Reaction selectivity in case of intimate contact between Pt particles and zeolite acid sites. Feedstock and catalyst weights are as in Table 1 with HY(30) as an acid catalyst.

Pyridine-poisoning results indicate that upon initial activation on the Pt surface, the reaction intermediates could further react over both HY and WO3/ZrO2 acid sites (Fig. 4, B and C). The precracking of intermediates over WO3/ZrO2 before their consecutive reaction on HY is less kinetically significant. This observation points to coupling between zeolite acid sites and Pt particles as a prerequisite for an active catalyst. To test this hypothesis, we synthesized Pt/HY catalyst and analyzed its performance in a mixture with WO3/ZrO2 (two rightmost bars in Fig. 4A). The presence of Pt near zeolite acid sites, as attempted in the past, leads to overcracking and the formation of light products (29). Over the Pt/HY catalyst, most of the intermediates are confined in the zeolite microporous network, where larger hydrocarbons exhibit substantial diffusional limitations. So, the reaction selectivity shifts to light products. On the other hand, anchoring Pt nanoparticle on WO3/ZrO2 supports leads to a separation between the zeolite and the Pt sites, increasing the yields of medium- and high-range products. In the latter case, the HY zeolite consumes the C>13 reaction intermediates, accelerating their production over Pt/WO3/ZrO2 (Figs. 2E and 4B). The optimal ratio between the zeolite and Pt/WO3/ZrO2 allows maintaining a high-reaction rate without deep-cracking the valuable C8–12 products. Thus, site separation in this technology is crucial for this tandem catalysis.

The reactivity trends discussed above are characteristic for HY(30) zeolite. The intrinsic propensity of zeolite to crack reaction intermediates to smaller C5–7 products is predetermined by the concentration of acid sites (Si/Al ratio) and by diffusion constraints (mesoporosity/microporosity balance). So, usage of a zeolite with a higher Si/Al ratio and/or increased content of mesopores should lead to less severe cracking of reaction intermediates toward C5–7.

Experiments with both components of the catalyst blend being poisoned by pyridine lead to nearly zero activity. Pt nanoparticles alone could not provide any substantial C─C─ bond breaking, because metal-catalyzed monofunctional hydrogenolysis requires longer reaction time and higher reaction temperature (24, 25).

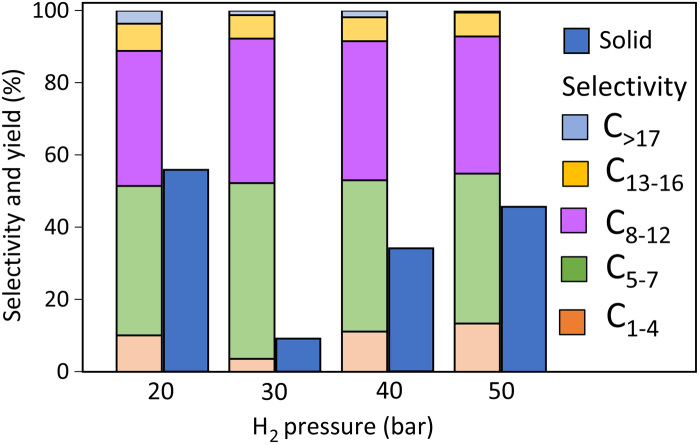

Appreciable reaction occurs even at 225°C; however, increasing the reaction temperature at constant reaction time enhances the yields of light C5–7 products via consecutive cracking reactions from C13+ to C8–12 to C5–7 products (table S3, visualized in the two-dimensional contour plots in fig. S8). Increasing reaction times at constant temperature has a similar effect. High–molecular weight products are attainable at short reaction times and/or low temperatures (table S3) with some compromise toward solid residue. This observation indicates the strong tendency of the catalyst blend to crack C12–30 alkanes to smaller products. The hydrogen pressure (PH2) exhibits an optimum catalyst performance at 30 bar (Fig. 5). At lower PH2, the rate of hydrocracking decreases, resulting in lower LDPE conversion. FTIR spectroscopy of adsorbed pyridine (fig. S9) showed that hydrogen pretreatment does not affect the concentration of stable Brønsted acid sites on Pt/WO3/ZrO2 but significantly increases their relative strength. Lack of strong Brønsted acid sites at low PH2 is a possible reason of low activity. The reduction in performance at higher PH2 and the concomitant higher selectivity toward C1-4 products and drop in C>17 selectivity may be associated with a shift in the alkane-olefin equilibrium and a consequent loss of active olefin intermediates and/or saturation of the Pt/WO3/ZrO2 active sites with adsorbed hydrogen.

Fig. 5. Effect of hydrogen pressure on LDPE conversion over Pt/WO3/ZrO2 mixed with HY(30).

Conditions: 250°C, 1 hour. Weights are in Table 1.

In comparison to pyrolysis, we estimated significant energy savings, nearly twofold or more in heating due to low operating temperatures in the melt and two- to fourfold for carrying out thermal cracking versus hydrocracking chemistry due to making hydrogenated products of larger molecular weight (see discussion in the Supplementary Materials).

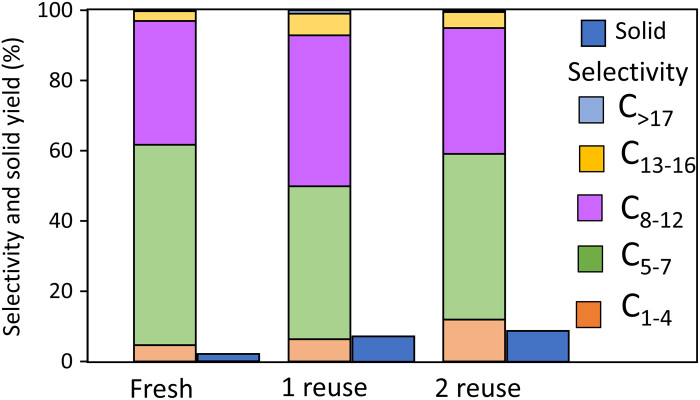

On the basis of TGA results (fig. S10), a relatively high calcination temperature is required to remove both the coke deposits and solid residue. Thus, the catalyst was calcined at 500°C in air and subsequently reduced at 250°C with hydrogen to regenerate activity. The catalyst blend can be fully regenerated with only a minor increase in the yield of solid residue and C1–4 products (Fig. 6). Across the regenerated samples, C5–12 selectivity remains constant, while the solid yield increases from 1.9 to 9.0%. CO chemisorption was used to elucidate possible changes of Pt dispersion during regeneration. Results show that after regeneration, the catalyst adsorbed 1.9 times more CO than the fresh Pt/WO3/ZrO2 and HY(30) mixture. This fact indicates that Pt dispersion increases during regeneration from ca. 57% close to 100%. At high temperature in an oxidizing atmosphere, Pt atoms could migrate from the WO3/ZrO2 surface to zeolite micropores because of the well-known high volatility of PtO2 (35). Thus, other factors rather than Pt agglomeration is responsible for the change in activity. X-ray diffraction analysis (fig. S10A) of regenerated catalyst showed a strong decrease of HY zeolite unit cell size, which originates from lower Al content in the framework (36). So, partial zeolite dealumination during regeneration may be responsible for the small acidity decrease and activity reduction. TGA analysis (fig. S10, B and C) shows that spent catalysts contain ca. 40 wt % of coke deposits and solid residues covering Pt particles and acid sites.

Fig. 6. Pt/WO3/ZrO2 mixed with HY(30) recyclability.

Conditions: 275°C, 1 hour, and 30 bar H2. Regeneration conditions: 500°C and 3 hours in static air.

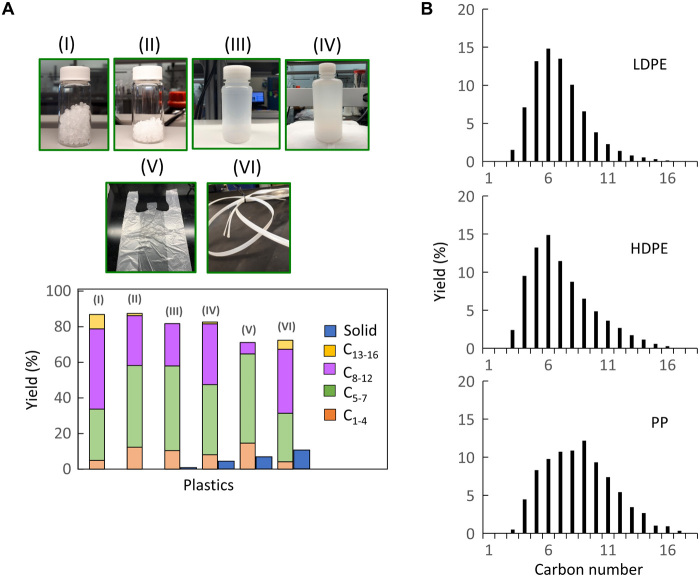

A major challenge in the plastics waste problem is the shift from single-component to multicomponent plastics (37), particularly in the packaging industry (38), e.g., composites, multilayers, and blends (39). Developing catalysts that can treat multiple single and mixed streams is essential. We performed catalytic tests with virgin granules of LDPE, HDPE, isotactic PP, PS, tapes of mixed layered plastics, and various bottles and transparent bags (Fig. 7 and fig. S11). The catalyst mixture can effectively convert all the plastic components, even everyday plastics, into liquid products with high yields (60 to 85%). The dual catalyst is active for hydrocracking HDPE to even higher yields of liquid than with LDPE. Hydrocracking of PP gave ca. 43% yield of diesel, which is substantially higher than that for LDPE (16%) and HDPE (19%) at similar experimental conditions (Fig. 7B). Obviously, compounds with ternary carbon atoms are more prone to crack over zeolites (40, 41), so the difference in the product distribution of PP and LDPE is difficult to explain by their C─C bond strength and polymer backbone structure alone. Limitations in the dehydrogenation kinetics play an important role in the initial PP activation, thus shifting the product distribution to heavier compounds. Everyday plastics were also converted with minimal solid yield within 8 hours (Fig. 7). The need to extend the reaction time is due to the presence of additives, such as stabilizers and dyes.

Fig. 7. Hydrocracking of different feedstocks.

(A) (I) PP granules, (II) HDPE granules, (III) LDPE bottle, (IV) HDPE bottle, (V) HDPE bag, and (VI) 45 volume % of PP to 45 volume % of PE to 10 volume % of PS composite tape. (B): Product distribution by carbon number for different polyolefin feedstocks over Pt/WO3/ZrO2 mixed with HY(30). Reaction conditions: 250°C and 30 bar H2; reaction time: (A) 2 hours for (I) to (IV), 8 hours for (V), and 4 hours for (VI); (B) 2 hours. Photo credit: Brandon Vance, University of Delaware.

Hydrocracking of everyday plastics and virgin polyolefins at mild reaction conditions demonstrated here is a promising energy-saving approach toward plastic waste-to-fuels conversion. The synergy of the dual catalyst via tandem chemistry allows one to fine-tune the activity and selectivity to highly branched gasoline or jet and diesel-range hydrocarbon products. Because the proposed catalyst is active in hydrocracking of different types of plastics, including most common PP and PE, preseparation of waste feedstocks are not required. Engineering the reaction conditions as well as the acidity and porosity of the HY zeolite are crucial for controlling the selectivity toward various products to meet the ever-changing market needs.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Preparation of Pt/WO3/ZrO2

WO3/ZrO2 supports were prepared by impregnating zirconia (IV) hydroxide [Zr(OH)4, 97%; Sigma-Aldrich] with an ammonium metatungstate hydrate [(NH4)6H2W12O40∙xH2O, 99.99%; Sigma-Aldrich] solution, dried in air at 110°C, and then calcined at 800°C for 3 hours (2°C/min ramp) in static air. The ZrO2 supports were loaded with 15 wt % WO3. The Pt/WO3/ZrO2 catalysts were synthesized by impregnating the WO3/ZrO2 supports with a chloroplatinic acid (H2PtCl6, 8 wt % in H2O; Sigma-Aldrich) solution, dried at 110°C, and then calcined at 500°C for 3 hours (2°C/min ramp) in static air. The catalysts were loaded with 0.5 wt % Pt.

Zeolite samples

Zeolites HY(30), HY(60), HY(80), HZSM-5(23), HBEA(25) and HMOR(20) were purchased from Zeolyst International. Al-MCM-41 (Si/Al = 39.5) was obtained from Sigma-Aldrich. All samples were prepared by calcining at 550°C for 4 hours (2°C/min ramp). For all the zeolite samples, the SiO2/Al2O3 ratio is indicated in parenthesis.

Desilication

Zeolite HY(30) was immersed in NaOH solution for 30 min at 60°C. Samples are denoted according to the NaOH concentration in the initial solution: M1 for 0.1 M, M2 for 0.2 M, M3 for 0.3 M, and M4 for 0.4 M.

After treatment, the samples were filtered, extensively washed with deionized water, and dried overnight at 110°C. The obtained samples were further exchanged to the H-form with aqueous NH4NO3, followed by drying at 110°C overnight with consecutive calcination at 550°C for 4 hours in the air. No sodium impurities were found in the samples by x-ray fluorescence analysis.

Feedstocks

LDPE [weight-average molecular weight (Mw), 250,000], HDPE, isotactic PP (Mw, 250,000), and PS (Mw, 35,000) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. The 120 ml. LDPE and 240 ml. HDPE bottles were obtained from SP Scienceware, and the HDPE t-shirt transparent bags were purchased from ULINE.

Catalyst characterization

The x-ray diffraction pattern of powdered calcined samples was measured on a Brucker D8 diffractometer in θ-θ geometry with a step size of 0.05°, 3 s per point. Porosity and surface area were investigated by N2 adsorption at −196°C on a Micromeritics ASAP 2020 instrument. Before adsorption, samples were pretreated in vacuum at 300°C overnight (ramping rate 2°/min). Chemical compositions were determined on a Rigaku Supermini 200 WDXRF. X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy spectra were recorded on a Thermo Fisher Scientific K-Alpha instrument with Al Kα radiation. Transmission electron microscope (TEM) images were acquired on an Aberration Corrected Scanning/Transmission Electron Microscope, JEOL NEOARM TEM/STEM.

CO chemisorption on Pt/WO3/ZrO2 was conducted using the pulse technique on a Micromeritics AutoChem II instrument. Diffuse reflectance infrared fourier transform spectra of adsorbed CO were recorded on a Nicolet 8700 spectrometer with a liquid nitrogen–cooled mercury cadmium telluride (MCT) detector and a Praying Mantis in situ flow cell equipped with KBr windows. Before adsorption, the sample were heated in 20% H2/He flow for 2 hours at 250°C, then purged with pure He for 0.5 hours, and cooled to room temperature. CO (99.99%; Praxair) was dosed onto the sample using a six-port valve with a calibrated loop.

FTIR transmission spectra of adsorbed pyridine followed by pyridine thermodesorption were recorded in a homemade pyrex flow cell equipped with KBr windows. Before measurements, the sample was reduced ex situ in a flow furnace for 2 hours at 250°C in 50% H2/He flow and left for 3 months in a sealed vial. Then, the sample was pressed in a self-supported wafer (1.27 cm2 and 40 bar/cm2 pressure), placed in a reactor sample holder, and heated in flow of pure He or in flow of 20% H2/He to 250°C (ramping rate 2°C/min) with 2-hour dwell at that temperature and 1-hour extra flushing with pure He. Then, the temperature was reduced to 150°C, and the sample was treated with pyridine vapor by passing He flow, although the bubbler filled with liquid pyridine (99.8%; Sigma-Aldrich). After saturation, the sample was flushed with pure He for 30 min, then the temperature was increased with a 10°C/min rate to 350°C in constant flow of He, and spectra were recorded every 1 min. Integration and peak deconvolution were done using the Omnic 8.2 software.

TGA of fresh and spent catalysts were conducted on a Discovery TGA (TA Instruments) in flow of air (50 ml/min) in the range of 25° to 700°C with a 10°C/min heating rate. Differential scanning calorimetry (DSC) of initial LDPE and solid residue was performed on Discovery DSC (TA Instruments) in flow of nitrogen (50 ml/min) with a heating rate of 10°/min in 30’ to 200°C range.

Catalyst pretreatment and reaction tests

Pt/WO3/ZrO2 was reduced before reaction in a 100 ml/min equimolar flow of H2 and He gas at 250°C for 2 hours (10°C/min ramp). Reduced Pt/WO3/ZrO2 and HY zeolite, at specified mass ratios, were mechanically mixed with 2.0 g of plastic in a 50-ml stainless-steel Parr reactor using a 0.7-ml stir bar. The mass ratio of LDPE to catalyst blend was maintained at 10 for all tests. After mixing, the Parr reactor was sealed and purged six times with H2 at 15 bar, charged to 30 bar for reaction, and then heated to reaction temperature. Reactions were maintained for specified time intervals and then were quickly quenched by plunging the Parr vessel in a water-ice bath and flowing house air over the lid. Products were collected once the temperature of the reactor fell below 10°C.

Product analysis

Gas samples from the headspace of the Parr reactor were charged in a Tedlar gas sampling bag and analyzed with gas chromatography-flame ionization detector (GC-FID) (Agilent HP-Plot GC column). The residual oil mixture was combined with approximately 20 ml of CH2Cl2 [American Chemical Society (ACS) grade, Thermo Fisher Scientific] containing 20 mg of octacosane (n-C28, TCI chemicals, ≥98.0%) as an internal standard. This mixture was separated from the catalyst and the unreacted solid by filtration (GE Whatman, 100 μm) and analyzed by GC-FID (Agilent HP-1 column) and GC-MS (Agilent DB-1 column). Calibration coefficients were measured by injection of the analytical standards (Supelco 04071). Typical GC trace of liquid products obtained from LDPE was shown in fig. S2.

The yield of the product group with ith carbons was calculated as

where ni is the number of carbon atoms in the product group with ith carbons, while ninitial is the number of carbon atoms in the initial polymer. The yield of solid residue was estimated gravimetrically.

The selectivity of the product group with ith carbons was calculated as

where ∑Yj corresponds to the total yield of all reaction products collected in liquid and in gas (excluding solid residue).

Degree of branching was determined as portion of isomerized Ci (isoCi) hydrocarbon in all Ci fraction (isoCi + nCi)

The carbon balance in all experiments were higher than 85%. All reported values have been rounded up given relative error of 10%.

Catalyst regeneration

To recover activity, the catalyst blend was filtered with 100 ml of CH2Cl2 (ACS grade, Thermo Fisher Scientific), dried in air overnight at 110°C, calcined at 500°C for 3 hours (2°C/min ramp) in static air, and then reduced in a 100 ml/min equimolar flow of H2 and He gas at 250°C for 2 hours (10°C/min ramp).

Acknowledgments

Thanks to A. Foucher for obtaining the microscopy images in the Supplementary Materials. Funding: This work was financially supported by the Center for Plastics Innovation (CPI), an Energy Frontier Research Center funded by the U.S. Department of Energy, Office of Science, Office of Basic Energy Sciences, award no. DE-SC0021166. This research used instruments in the Advanced Materials Characterization Lab (AMCL) at the University of Delaware. Author contributions: S.L. and D.G.V. conceived the project and designed the experiments. S.L., P.A.K., and B.C.V. executed all the experiments. A.D. reproduced some experiments. P.A.K., S.L., B.C.V., and D.G.V. wrote the article. All the authors proofread the manuscript. Competing interests: S.L. and D.G.V. are inventors on a patent application related to this work filed by the University of Delaware (no. 63/040,581, filed 18 June 2020). The authors declare no other competing interests. Data and materials availability: All data needed to evaluate the conclusions in the paper are present in the paper and/or the Supplementary Materials. Additional data related to this paper may be requested from the authors.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIALS

Supplementary material for this article is available at http://advances.sciencemag.org/cgi/content/full/7/17/eabf8283/DC1

REFERENCES AND NOTES

- 1.Rochman C. M., Browne M. A., Halpern B. S., Hentschel B. T., Hoh E., Karapanagioti H. K., Rios-Mendoza L. M., Takada H., Teh S., Thompson R. C., Classify plastic waste as hazardous. Nature 494, 169–171 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.The New Plastics Economy: Rethinking the Future of Plastics (Ellen MacArthur Foundation, 2016).

- 3.Rahimi A., García J. M., Chemical recycling of waste plastics for new materials production. Nat. Rev. Chem. 1, 0046 (2017). [Google Scholar]

- 4.United States Environmental Protection Agency. Advancing Sustainable Materials Management: 2017 Fact Sheet. United States Environ. Prot. Agency, Off. L. Emerg. Manag. Washington, DC 20460 2019, No. July, 22, https://www.epa.gov/sites/production/files/2019-11/documents/2017_facts_and_figures_fact_sheet_final.pdf (2019).

- 5.United Nations Environment Porgramme. Single-Use Plastic: A Roadmap for Sustainability (2018).

- 6.Garcia J. M., Robertson M. L., The future of plastics recycling. Science 358, 870–872 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lamb J. B., Willis B. L., Fiorenza E. A., Couch C. S., Howard R., Rader D. N., True J. D., Kelly L. A., Ahmad A., Jompa J., Drew Harvell C., Plastic waste associated with disease on coral reefs. Science 359, 460–462 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kulkarni P., Pache R., Depolymerization of polypropylene: A systematic review. J. Polym. Compos. 4, 1–16 (2016). [Google Scholar]

- 9.Banu J. R., Sharmila V. G., Ushani U., Amudha V., Kumar G., Impervious and influence in the liquid fuel production from municipal plastic waste through thermo-chemical biomass conversion technologies-A review. Sci. Total Environ. 718, 137287 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lopez G., Artetxe M., Amutio M., Bilbao J., Olazar M., Thermochemical routes for the valorization of waste polyolefinic plastics to produce fuels and chemicals. A review. Renew. Sust. Energ. Rev. 73, 346–368 (2017). [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wong S. L., Ngadi N., Abdullah T. A. T., Inuwa I. M., Current state and future prospects of plastic waste as source of fuel: A review. Renew. Sust. Energ. Rev. 50, 1167–1180 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- 12.Miandad R., Barakat M. A., Aburiazaiza A. S., Rehan M., Nizami A. S., Catalytic pyrolysis of plastic waste: A review. Process Saf. Environ. Protection 102, 822–838 (2016). [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kunwar B., Cheng H. N., Chandrashekaran S. R., Sharma B. K., Plastics to fuel: A review. Renew. Sust. Energ. Rev. 54, 421–428 (2016). [Google Scholar]

- 14.Songip A. R., Masuda T., Kuwahara H., Hashimoto K., Test to screen catalysts for reforming heavy oil from waste plastics. Appl. Catal. Environ. 2, 153–164 (1993). [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mordi R. C., Fields R., Dwyer J., Thermolysis of low density polyethylene catalysed by zeolites. J. Anal. Appl. Pyrolysis 29, 45–55 (1994). [Google Scholar]

- 16.Aguado J., Serrano D. P., Escola J. M., Garagorri E., Fernández J. A., Catalytic conversion of polyolefins into fuels over zeolite beta. Polym. Degrad. Stab. 69, 11–16 (2000). [Google Scholar]

- 17.Garforth A. A., Lin Y. H., Sharratt P. N., Dwyer J., Production of hydrocarbons by catalytic degradation of high density polyethylene in a laboratory fluidised-bed reactor. Appl. Catal. Gen. 169, 331–342 (1998). [Google Scholar]

- 18.Akpanudoh N. S., Gobin K., Manos G., Catalytic degradation of plastic waste to liquid fuel over commercial cracking catalysts: Effect of polymer to catalyst ratio/acidity content. J. Mol. Catal. A Chem. 235, 67–73 (2005). [Google Scholar]

- 19.Uemichi Y., Hattori M., Itoh T., Nakamura J., Sugioka M., Deactivation behaviors of zeolite and silica−alumina catalysts in the degradation of polyethylene. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 37, 867–872 (1998). [Google Scholar]

- 20.Santos B. P. S., Almeida D., de Fatima V. Marques M., Henriques C. A., Petrochemical feedstock from pyrolysis of waste polyethylene and polypropylene using different catalysts. Fuel 215, 515–521 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 21.Beltrame P. L., Carniti P., Audisio G., Bertini F., Catalytic degradation of polymers: Part II—Degradation of polyethylene. Polym. Degrad. Stab. 26, 209–220 (1989). [Google Scholar]

- 22.Williams P. T., Slaney E., Analysis of products from the pyrolysis and liquefaction of single plastics and waste plastic mixtures. Resour. Conserv. Recy. 51, 754–769 (2007). [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhao D., Wang X., Miller J. B., Huber G. W., The chemistry and kinetics of polyethylene pyrolysis: A feedstock to produce fuels and chemicals. ChemSusChem 13, 1764 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Celik G., Kennedy R. M., Hackler R. A., Ferrandon M., Tennakoon A., Patnaik S., LaPointe A. M., Ammal S. C., Heyden A., Perras F. A., Pruski M., Scott S. L., Poeppelmeier K. R., Sadow A. D., Delferro M., Upcycling single-use polyethylene into high-quality liquid products. ACS Cent. Sci. 5, 1795–1803 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tennakoon A., Wu X., Paterson A. L., Patnaik S., Pei Y., LaPointe A. M., Ammal S. C., Hackler R. A., Heyden A., Slowing I. I., Coates G. W., Delferro M., Peters B., Huang W., Sadow A. D., Perras F. A., Catalytic upcycling of high-density polyethylene via a processive mechanism. Nat. Catal. 3, 893–901 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhang F., Zeng M., Yappert R. D., Sun J., Lee Y. H., LaPointe A. M., Peters B., Abu-Omar M. M., Scott S. L., Polyethylene upcycling to long-chain alkylaromatics by tandem hydrogenolysis/aromatization. Science 370, 437–441 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ding W., Liang J., Anderson L. L., Hydrocracking and hydroisomerization of high-density polyethylene and waste plastic over zeolite and silica−alumina-supported Ni and Ni−Mo sulfides. Energy Fuel 11, 1219–1224 (1997). [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hesse N. D., White R. L., Polyethylene catalytic hydrocracking by PtHZSM-5, PtHY, and PtHMCM-41. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 92, 1293–1301 (2004). [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bin Jumah A., Anbumuthu V., Tedstone A. A., Garforth A. A., Catalyzing the hydrocracking of low density polyethylene. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 58, 20601–20609 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 30.Venkatesh K. R., Hu J., Wang W., Holder G. D., Tierney J. W., Wender I., Hydrocracking and hydroisomerization of long-chain alkanes and polyolefins over metal-promoted anion-modified zirconium oxides. Energy Fuel 10, 1163–1170 (1996). [Google Scholar]

- 31.Escola J. M., Aguado J., Serrano D. P., García A., Peral A., Briones L., Calvo R., Fernandez E., Catalytic hydroreforming of the polyethylene thermal cracking oil over Ni supported hierarchical zeolites and mesostructured aluminosilicates. Appl. Catal. Environ. 106, 405–415 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- 32.Liang Z., Chen L., Alam M. S., Zeraati Rezaei S., Stark C., Xu H., Harrison R. M., Comprehensive chemical characterization of lubricating oils used in modern vehicular engines utilizing GC× GC-TOFMS. Fuel 220, 792–799 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 33.P. B. Weisz, in Advances in Catalysis (Elsevier, 1962), vol. 13, pp. 137–190. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Regali F., Liotta L. F., Venezia A. M., Boutonnet M., Järås S., Hydroconversion of n-hexadecane on Pt/silica-alumina catalysts: Effect of metal loading and support acidity on bifunctional and hydrogenolytic activity. Appl. Catal. Gen. 469, 328–339 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jones J., Xiong H., DeLaRiva A. T., Peterson E. J., Pham H., Challa S. R., Qi G., Oh S., Wiebenga M. H., Hernández X. I. P., Wang Y., Datye A. K., Thermally stable single-atom platinum-on-ceria catalysts via atom trapping. Science 353, 150–154 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Arafat A., Jansen J. C., Ebaid A. R., van Bekkum H., Microwave preparation of zeolite Y and ZSM-5. Zeolites 13, 162–165 (1993). [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lebreton L., Andrady A., Future scenarios of global plastic waste generation and disposal. Palgrave Commun. 5, 6 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kaiser K., Schmid M., Schlummer M., Recycling of polymer-based multilayer packaging: A review. Dent. Rec. 3, 1 (2017). [Google Scholar]

- 39.Eastman Launches Chemical Recycling Innovation for Complex Plastic Waste, 4/15/2019D (2019); www.ptonline.com/blog/post/eastman-launches-chemical-recycling-innovation-for-complex-plastic-waste.

- 40.Corma A., Wojciechowski B. W., The chemistry of catalytic cracking. Catal. Rev. 27, 29–150 (1985). [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bhan A., Gounder R., Macht J., Iglesia E., Entropy considerations in monomolecular cracking of alkanes on acidic zeolites. J. Catal. 253, 221–224 (2008). [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kim D. S., Ostromecki M., Wachs I. E., Kohler S. D., Ekerdt J. G., Preparation and characterization of WO3/SiO2 catalysts. Catal. Lett. 33, 209–215 (1995). [Google Scholar]

- 43.Daniel M. F., Desbat B., Lassegues J. C., Gerand B., Figlarz M., Infrared and Raman study of WO3 tungsten trioxides and WO3, xH2O tungsten trioxide tydrates. J. Solid State Chem. 67, 235–247 (1987). [Google Scholar]

- 44.Liu H., Huang S., Zhang L., Liu S., Xin W., Xu L., The preparation of active WO3 catalysts for metathesis between ethene and 2-butene under moist atmosphere. Catal. Commun. 10, 544–548 (2009). [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kappers M. J., van der Maas J. H., Correlation between CO frequency and Pt coordination number. A DRIFT study on supported Pt catalysts. Catal. Lett. 10, 365–373 (1991). [Google Scholar]

- 46.Di Gregorio F., Keller V., Activation and isomerization of hydrocarbons over WO3/ZrO2 catalysts: I. Preparation, characterization, and X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy studies. J. Catal. 225, 45–55 (2004). [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kenvin J., Mitchell S., Sterling M., Warringham R., Keller T. C., Crivelli P., Jagiello J., Pérez-Ramírez J., Quantifying the complex pore architecture of hierarchical faujasite zeolites and the impact on diffusion. Adv. Funct. Mater. 26, 5621–5630 (2016). [Google Scholar]

- 48.Triwahyono S., Yamada T., Hattori H., IR study of acid sites on WO3–ZrO2 and Pt/WO3–ZrO2. Appl. Catal. Gen. 242, 101–109 (2003). [Google Scholar]

- 49.Comelli R. A., Canavese S. A., Querini C. A., Fígoli N. S., Coke deposition on platinum promoted WOx–ZrO2 during n-hexane isomerization. Appl. Catal. Gen. 182, 275–283 (1999). [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary material for this article is available at http://advances.sciencemag.org/cgi/content/full/7/17/eabf8283/DC1