Abstract

Background:

Family caregivers of patients with severe acute brain injury (SABI) admitted to intensive care units (ICUs) with coma experience heightened emotional distress stemming from simultaneous stressors. Stress and coping frameworks can inform psychosocial intervention development by elucidating common challenges and ways of navigating such experiences but have yet to be employed with this population. The present study therefore sought to use a stress and coping framework to characterize the stressors and coping behaviors of family caregivers of patients with SABI hospitalized in ICUs and recovering after coma.

Methods:

Our qualitative study recruited a convenience sample from 14 US neuroscience ICUs. Participants were family caregivers of patients who were admitted with ischemic stroke, intracerebral hemorrhage, subarachnoid hemorrhage, traumatic brain injury, or hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy; had experienced a comatose state for > 24 h; and completed or were scheduled for tracheostomy and/or gastrostomy tube placement. Participants were recruited < 7 days after transfer out of the neuroscience ICU. We conducted live online video interviews from May 2021 to January 2022. One semistructured interview per participant was recorded and subsequently transcribed. Recruitment was stopped when thematic saturation was reached. We deductively derived two domains using a stress and coping framework to guide thematic analysis. Within each domain, we inductively derived themes to comprehensively characterize caregivers’ experiences.

Results:

We interviewed 30 caregivers. We identified 18 themes within the two theory-driven domains, including ten themes describing practical, social, and emotional stressors experienced by caregivers and eight themes describing the psychological and behavioral coping strategies that caregivers attempted to enact. Nearly all caregivers described using avoidance or distraction as an initial coping strategy to manage overwhelming emotions. Caregivers also expressed awareness of more adaptive strategies (e.g., cultivation of positive emotions, acceptance, self-education, and soliciting social and medical support) but had challenges employing them because of their heightened emotional distress.

Conclusions:

In response to substantial stressors, family caregivers of patients with SABI attempted to enact various psychological and behavioral coping strategies. They described avoidance and distraction as less helpful than other coping strategies but had difficulty engaging in alternative strategies because of their emotional distress. These findings can directly inform the development of additional resources to mitigate the long-term impact of acute psychological distress among this caregiver population.

Keywords: Coma, Family caregivers, Informal caregivers, Interview

Introduction

Severe acute brain injuries (SABIs) that cause coma and require intensive care unit (ICU) admission often place patients’ family caregivers in stressful situations [1-3]. Patients are unable to communicate, and caregivers are tasked with adjusting to unfamiliar environments while grappling with patients’ potential but uncertain lifelong physical and cognitive changes [2, 4]. Long-term clinically elevated emotional distress (i.e., depression, anxiety, and posttraumatic stress) is very common among these caregivers [5, 6], particularly in cases of partial recovery from comatose states [7-9]. Professional societies and workgroups focused on promoting coma recovery have drawn attention to an urgent need to better support family caregivers of these patients from ICU admission through transition to post-ICU care [1, 10].

To design interventions that appropriately address these caregivers’ unique challenges and emotional needs, it is important to understand their lived ICU experiences in the context of established theoretical frameworks describing adjustment to acute and chronic stressors, including Lazarus and Folkman’s stress and coping theoretical framework [11, 12]. Stress and coping theories describe the variety of ways in which individuals respond to circumstances to try to manage the negative impact of stress [11, 12]. This framework defines stressors as situations perceived as challenging, threatening, or aversive and coping strategies as responses enacted to manage stressors. In the present study, we used this theoretical framework [11, 12] to guide a multicenter qualitative investigation enrolling family members of patients with SABI expected to survive hospitalization with varying degrees of initial recovery from coma, all near the time of transition out of the ICU after a recent decision to proceed with tracheostomy and/or feeding tube placement. Psychosocial interventions for other populations of ICU families that have been timed both to begin in the acute phase of injury and to continue into the weeks following hospitalization have shown promise for impacting long-term emotional outcomes [13]. Understanding stressors and coping strategies among families of ICU coma patients during this time frame is a critical step for developing similar acute and post-ICU interventions for this specific population.

Methods

Study Design and Sample

For this multicenter qualitative study, we recruited a convenience sample of family caregivers of patients with SABI admitted with coma from 14 US neuroscience ICUs (see eAppendix Supplement for a list of sites). The institutional review board at each site either approved study procedures or granted study exemptions. Family participants were 18 years or older and English-speaking. We included caregivers of patients who met the following criteria: (1) were admitted with ischemic stroke, intracerebral hemorrhage, subarachnoid hemorrhage, traumatic brain injury, or hypoxicischemic encephalopathy; (2) had either a Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) score < 9 while not intubated or an inability to follow commands while intubated (thought to be due to structural brain injury by the medical team and not by confounding medications or uncontrolled seizures) for a period of at least 24 h; (3) remained incapacitated and had undergone or were definitively scheduled for tracheostomy and/or percutaneous endoscopic/surgical gastrostomy (PEG) tube placement; and (4) were either still admitted to the ICU awaiting upcoming transfer to a lower level of care or had transferred out of the ICU for less than 7 days. One caregiver was recruited per patient; for families with more than one member, we prioritized recruitment of the primary caregiver, as self-defined by the family. All enrolled family caregivers provided written informed consent. We excluded caregivers of patients who were not expected by the clinical team to survive their hospitalization or who had concurrent diagnosis of terminal illness aside from their SABI given the goal of this study to inform acute and post-ICU interventions for caregivers with continued caregiving roles.

Data Collection

We developed a 60-min semistructured interview guide (see eAppendix Supplement) structured around a stress and coping framework [11, 12] via multidisciplinary team meetings among one neurointensivist (DYH) and two clinical psychologists (SMB and A-MV) with expertise in ICU settings [13-15]. The guide contained open-ended questions pertaining to the psychosocial stressors experienced by caregivers and strategies for coping and was iteratively revised after the first three interviews.

A PhD-level clinical psychologist (SMB) conducted the first three interviews of caregivers over a secure telehealth platform and received weekly supervision with feedback from the multidisciplinary team. She then trained and supervised three clinical research coordinators from one study site to conduct study interviews. The psychologist provided guidance on establishing rapport with participants and provided weekly supervision to the coordinators. Recordings of interviews were transcribed verbatim and deidentified.

Sample Size

We continued recruitment until thematic saturation [16] was achieved and then completed the remaining scheduled interviews.

Data Analysis

We uploaded deidentified transcripts to the NVivo 12 qualitative data analysis software package (version released March 2020; QSR International) and analyzed data using thematic analysis and a hybrid inductive–deductive approach to organize findings [17]. Our approach was deductive in the sense that first we used prior literature to identify two overarching theory-driven domains, psychosocial stressors, and coping strategies [11, 12]. Then we used an inductive approach to generate codes pertaining to stressors and coping strategies directly from the data through open coding of transcripts. Through team discussions, we refined codes and fit them into overarching themes and categories across the two a priori determined domains. All transcripts were coded independently by at least two members of the research team (KM, RK, NB, and JK), with discrepancies in coding resolved during face-to-face meetings. Afterward, two members of the research team (DYH and SMB) independently extracted findings within the stress and coping domains based on prior literature [1, 14, 18-20] and data observations.

We followed the Consolidated Criteria for Reporting Qualitative Research reporting guidelines for qualitative studies (see Supplementary Materials) [21]. We organized inductively derived codes and organized them into themes and themes into categories to aid reader interpretation. We allowed themes to overlap to promote a comprehensive understanding of participants’ experiences. To describe participant and patient characteristics, we used univariate descriptive statistics.

Results

Recruitment of Convenience Sample

Between May 2021 and January 2022, we contacted 64 caregivers, of whom 34 (53.1%) either declined consent or chose not to participate following initial consent. Thematic saturation [16] was achieved at n = 27 caregivers; after we completed the remaining scheduled interviews, the final sample consisted of 30 caregivers.

Participant Characteristics

Table 1 displays caregiver and patient characteristics. Caregivers were mostly women (n = 23; 79.3%) and predominantly White (n = 19; 67.9%) or Black (n = 7; 25.0%), with the majority completing high school and/or some college (n = 18; 64.2%).

Table 1.

Participant and patient characteristics

| Result | |

|---|---|

| Caregiver characteristics (n = 30) | |

| Age, mean (SD), y (n = 28) | 47.2 (13.6) |

| Female sex (n = 29) | 23 (79.3%) |

| Hispanic ethnicity (n = 26) | 4 (15.4%) |

| Race (n = 28) | |

| White | 19 (67.9%) |

| Black or African American | 7 (25.0%) |

| Asian | 1 (3.6%) |

| American Indian or Alaskan Native | 1 (3.6%) |

| Education level (n = 28) | |

| Less than high school | 1 (3.6%) |

| Completed high school or GED | 9 (32.1%) |

| Some college or associate degree | 9 (32.1%) |

| Four years of college | 4 (14.3%) |

| Graduate/professional degree | 5 (17.9%) |

| Relationship to patient (n = 29) | |

| Spouse | 8 (27.6%) |

| Child | 8 (27.6%) |

| Parent | 7 (24.1%) |

| Sibling | 4 (13.8%) |

| Other | 2 (6.9%) |

| Patient characteristics (n = 30) | |

| Age, mean (SD), y | 50.4 (17.9) |

| Female sex | 14 (46.7%) |

| Hispanic ethnicity | 4 (13.3%) |

| Race | |

| White | 23 (76.7%) |

| Black or African American | 7 (23.3%) |

| Admission diagnosis | |

| TBI | 9 (30.0%) |

| ICH | 7 (23.3%) |

| SAH | 6 (20.0%) |

| AIS | 6 (20.0%) |

| HIE | 2 (6.7%) |

| Tracheostomy planned or performed | 25 (83.3%) |

| Percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy placement planned or performed | 29 (96.7%) |

| GCS score ≥ 9 at time of study enrollment | 14 (46.7%) |

AIS arterial ischemic stroke; GCS Glasgow Coma Scale; GED general equivalency diploma; HIE hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy; ICH intracerebral hemorrhage; SAH subarachnoid hemorrhage, TBI, traumatic brain injury

At the time of study enrollment, most patients had a tracheostomy planned or performed (n = 25; 83.3%). Only one patient did not have a PEG planned or performed; this patient received an initial tracheostomy but then was eventually able to swallow during admission. Approximately half of the patients (n = 14; 46.7%) had recovered to a GCS score of 9 or greater, despite still requiring tracheostomy and/or artificial nutrition and hydration.

Qualitative Themes

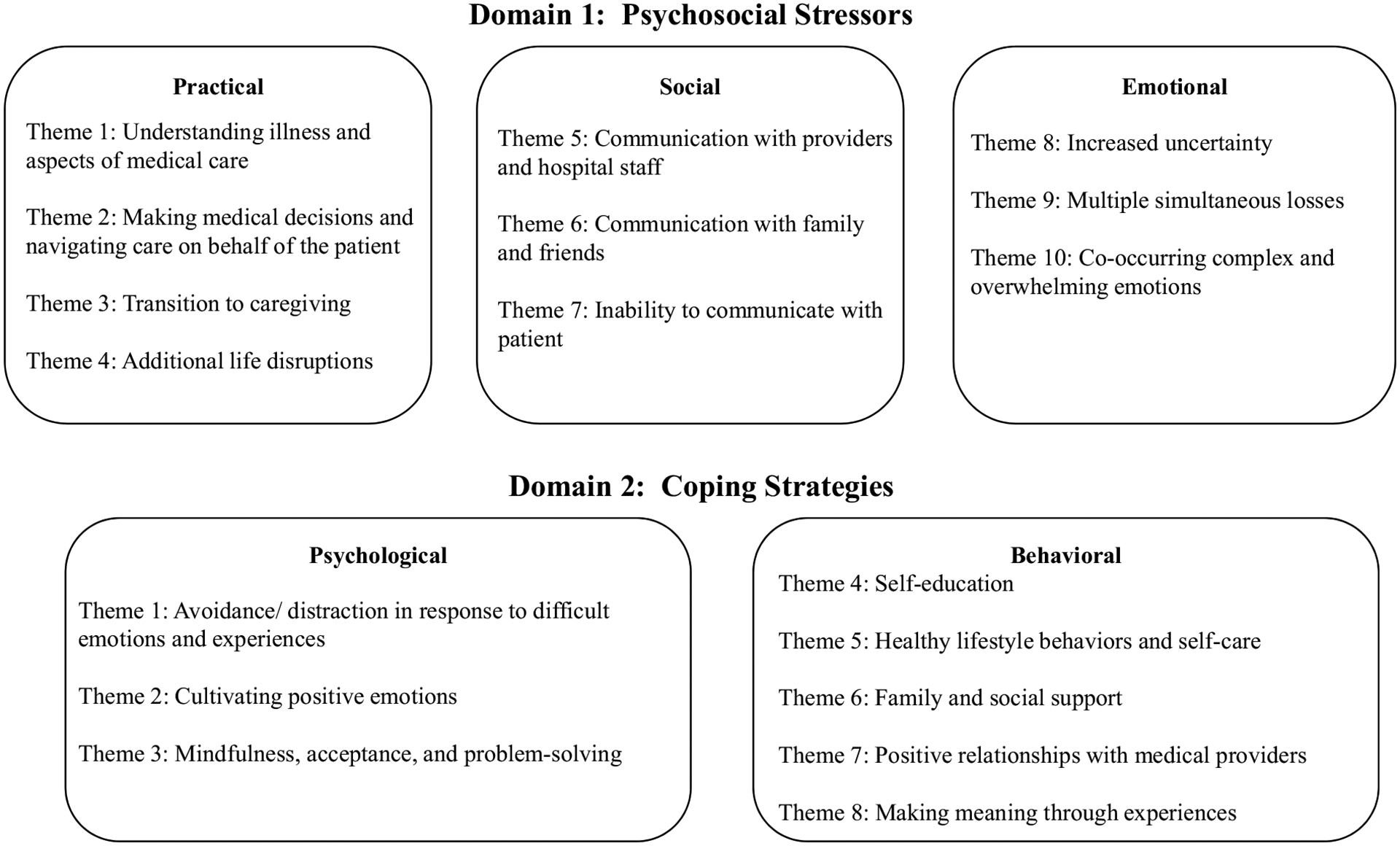

Figure 1 depicts our qualitative themes within the domains of psychosocial stressors and coping strategies. Within each domain, themes are organized into categories and described in further detail in the subsequent sections.

Fig. 1.

Qualitative themes. Themes are subdivided within the domains of (1) psychosocial stressors and (2) coping strategies

Domain 1: Psychosocial Stressors

We identified ten interrelated themes that pertain to the psychosocial stressors experienced by caregivers, which we organized into practical, social, and emotional categories (Table 2).

Table 2.

Description of themes and illustrative quotes for practical, social, and emotional stressors

| Theme | Theme definition | Illustrative quotations |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Understanding patient’s illness and medical care | Caregiver’s challenges understanding aspects of patients’ medical care, including medical terminology, communication about patients from providers, patients’ complex symptoms, conditions and prognosis, rapid changes in functioning, factors impacting medical decisions, and ways of obtaining information to inform current and future care plans | “I think, ironically, as a result of this study, they never used their word ‘comatose’ for us, right? And so, when I got the document to say, do you want to be part of this research, and it said like, comatose patients, and I was like wait, when was my mom comatose, right? It’s like, yeah, she was definitely nonresponsive, but I didn’t know that that’s what the medical community defined as—in a coma. And that would have been really helpful in both my understanding of her condition, as well as being able to communicate to other people, here’s where my mom is right now.” “Just basically, there were a lot of meetings in the very beginning while he was in the ICU, and the terminology was a lot. Leading us having to Google stuff when we left, which is never a good idea.” |

| 2. Making medical decisions and navigating care on behalf of the patient | Caregiver’s challenges making decisions about patients’ medical care (e.g., establishing guardianship, starting comfort care) and coordinating transitions (e.g., from ICU to floor after trach/PEG, transition to inpatient or outpatient rehab and medical appointments) amid uncertain or changing prognosis without being able to communicate with the patient | “So the list that was provided by the case manager for [patient’s name] had a list of a lot of rehabilitation places. Not all of them had longterm acute care, not all of them specialized in neuro, not a lot of them had disorders of consciousness, not all of them had emerging technique programs, and she just gave me the list to just do the research myself.” “That would be—like we still don’t know what is on the other side of this on waiting her next steps are. Like she’s in a nursing facility and doesn’t have part of her skull, and we still don’t even know the timeline for her to have that back, or how she’s going to change when that goes back in, and how we will need to adapt.” |

| 3. Transition to caregiving | Caregiver navigation of new responsibilities as primary caregiver of patient, specifically in terms of direct caregiving (e.g., communicating with providers, establishing plans for care, making decisions with patients’ and other family members’ preferences in mind) | “I was mad at myself because I felt like I needed to do more. I needed to find the number one everything, I needed to be on her doctors all the time, I needed to tell her nurses right from wrong, I needed to champion for her, basically, and I just didn’t have the energy to do that, and it felt very defeating.” “I think of it as—it is definitely something that I think about because now, I’m thinking okay, I work a 32-h shift, 7 to 3, like how’s that going to work? Like, he lives alone, is he going to be able to go back home, or is he going to be in an assisted living type thing?” |

| 4. Additional life disruptions | Caregivers’ stressors related to ongoing roles/responsibilities (e.g., quitting job or missed days at work, additional parenting, family, and household responsibilities) and managing medical, legal, financial, and practical matters (e.g., caregivers’ health care, employee assistance, parenting) | “I feel like I could sleep for 24 h; I’m exhausted. And just that, I mean we have a really great partnership, and we share the responsibilities of the kids and the house, and that’s sort of all fallen on me, and I didn’t even know how to pay–I’ve paid bills before, but– he manages all of our finances, like, I still can’t figure out how to log into one of our credit card accounts because I have no idea where his passwords are kept and everything, so I’m still working on that one but everything else is okay, but you know, just sort of like, I feel overwhelmed.” “I had to reach out to human resources to get—they have an employee assistance program that gives you specific access to discounts to services with lawyers and therapists and stuff like that. So, I had to reach out to them and ask for that information, and I also had to follow up to get additional information to be able to use it. So, it was not the most expedient process.” |

| 5. Communication with providers and hospital staff | Caregiver challenges communicating with health care providers and hospital staff (e.g., obtaining information, advocating for preferences, making medical decisions collaboratively) | “The only problem I might have with the hospital is the front desk; when you check in, they’re a little rude. They’re not very patient, I just have to say that, I mean, there was a miscommunication when she was first brought in, and we all got wristbands to go up, but when we [unclear] the waiting room, and my husband and I had been there all day, and her daughter got a little emotional and wanted to see her, because we were kind of under the impression that she was doing really bad, and she was, but we didn’t know. I honestly thought I was going to say goodbye to her. I didn’t know that she would have the chance to be better. So, they did call security on my 17-year-old granddaughter, and she had somebody watching her in the hallway, which is ridiculous.” “During kind of the initial conversations with the team about what are we going to do with him, you know, they told us, they weren’t pressuring us, they wanted us to take our time and really make a decision, but we did feel pressured, you know. We did feel pressured to make a decision and quickly. I feel like we weren’t given time to really kind of see how things play out, and I felt like if we would have, kind of made a rash decision and took him off of life support and ended his life, I would have felt so bad, knowing now that he’s recovering. So, you know, I feel like sometimes the decisions are too rash. Like let’s see what happens for a couple of weeks first before we make those huge decisions. So that’s something that I would change. I feel like there’s an immediate push to kind of make these big decisions, instead of kind of a watch-and-wait approach, even for just a little while.” |

| 6. Communication with family and friends | Caregivers’ challenges communicating and navigating relationships with family/friends besides patient during and after hospitalization (e.g., sharing information on prognosis, coordinating visits, discussing medical decisions and ways of navigating long-term care) | “It’s hard because my family is not medical and I am, so it’s hard to explain to them what’s going on without making me upset, and then my whole family, my husband’s family too, both sides, they would ask me questions and it was hard for me to answer, because sometimes I felt I didn’t want to accept some of the things that were happening to him.” “In the beginning, I would have someone texting me here, how’s your dad? Someone texting me there, hey, how’s your dad? Someone calling me. I was blocking so many calls, I was blocking so many numbers, but certain people know, that’s how I deal with stress. Like, I need to bring myself back down to reality before I can even, alright, to show information to this person and this person. I need to make sure that I’m okay. I can’t give you any update right now because I need to deal with myself. I have two young children that depend on me, so I can’t show any type of you know, unsettling issues. So, I feel like I have to just block out the world and deal with my own life before I can like, alright, let me open up, hey, my dad’s good.” |

| 7. Inability to communicate with patient | Caregivers’ challenges with disrupted relationship with patient (e.g., quality, bond, disruption in routines and/or communication) | “I keep hoping when I walk in the hospital he’s going to be able to speak and say something. That makes it really hard. Like if he could just tell us what he’s thinking, or what he’s feeling.” “He can’t talk. So, at least if I Zoom with him, I can see his reaction. I can see if he wants me to talk to him or if he’s getting tired of me talking to him. So, I just sit on the phone for hours having a conversation that I’m not even sure that he wants to be in that conversation. He can’t talk.” |

| 8. Increased uncertainty | Caregiver experience of uncertainty regarding current or future situation, especially regarding patient prognosis and eventual degree of patient’s recovery | “There would be times where they would ask us if they should do some life-saving measures, but they couldn’t tell me, after initial experience of her having the aneurysm, they couldn’t tell me like, oh in 12 months or in 12 weeks or anything, she’ll be back to herself or her baseline, or if she’d be virtually immobile for the rest of her life, so it’s hard to make those decisions about how we’re going to treat her without knowing what the expected outcome would be.” “I mean, I thought about it because I think of like future-wise, when he leaves the rehab, what’s his life going to be like? Is he going to need 24-h care, or is he going to be okay, or, like I just think of different things, but those, I don’t know, I kind of put things like that on the backburner because I don’t know what’s going to happen.” |

| 9. Multiple simultaneous losses | Caregiver experience of losing something (e.g., loss of normality, loss of relationships, loss of patient’s cognitive function, loss of patient’s self from before illness, loss of anticipated future) | “He is responding to things but I still miss my husband. It’s just a very weird, bizarre, alternate universe where my husband is gone but he’s still alive, and he’s working hard to come back.” “Every ounce of normalcy that I had, it feels lost now. I mean, I am on a leave of absence from work because I mean I work with chronically ill children, and I work in pediatric oncology, so I’m not going to go to work in a hospital when I’m going into a hospital for my family. And it’s very different when it’s your own family. And so I feel like that part of my life, I mean, that was a really important piece of my life. I love my work, and I would go back to it, but it’s hard to be in that setting with this going on.” |

| 10. Co-occurring complex and overwhelming emotions | Caregiver experience of difficult or overwhelming emotions, including emotions that are difficult to pinpoint, contradictory, or fluctuating (e.g., panic, guilt, anger, sadness, grief, confusion, worry) | “The machine starts going off, and I start panicking, and I press the button and tell them, look, you know, this machine is going off, and they’re all like, we’ll send somebody half an hour later, so, now, I’m, you know, almost had a panic attack, my heart’s beating, feel kind of dizzy, and I’ve just got to keep my soul calm.” “But that’s the guilt part. If I had checked her earlier, could she have been better off? You know. I know the logic behind it all that there’s nothing, it’s not my fault, there’s nothing I could have done, could’ve been this way regardless of 5 min or hours. I understand that logic, but that doesn’t take the feelings away, you know.” |

ICU, intensive care unit, PEG, percutaneous endoscopic/surgical gastrostomy, trach, tracheostomy

Practical Stressors

Caregivers faced difficulty understanding the patient’s illness and medical care (theme 1) because of patients’ changing symptoms and perceived lack of clear and reliable information surrounding medical terminology, treatment options, prognosis, recovery trajectory, and subsequent rehabilitation or long-term acute care. This stressor exacerbated their challenges making medical decisions and navigating medical care (theme 2). Caregivers felt unable to make plans for the future with limited information.

Patients’ sudden hospitalizations and incapacitated states also created challenges related to the abrupt transition to caregiving (theme 3). For example, caregivers experienced “huge emotional and physical stress” from their commutes to the hospital, efforts navigating patients’ medical care, and caregiving responsibilities at home. They also noted experiencing several additional co-occurring life disruptions and challenges outside the hospitalization (theme 4) related to loss of work, the financial impact of medical procedures, parenting and division of responsibilities at home, and navigating their own medical conditions.

Social Stressors

All caregivers described experiencing overwhelming confusion and frustration when communicating with medical and insurance providers and hospital staff (theme 5). They described providers’ tendency to focus “only about the immediate” issues regarding patients’ care. Additionally, the acute circumstances of hospitalization made it difficult to relate to providers’ preferred time frames (e.g., “They weren’t pressuring us, they wanted us to take our time and really make a decision, but we did feel pressured, you know.”).

For many participants in the sample, their role as primary caregiver also led to challenges communicating with family members and friends (theme 6). Caregivers found it difficult to navigate the role of informing others about the patient’s current status and medical care while also working to understand and process the patient’s prognosis, important medical decisions, and their own emotional experiences. Caregivers experienced frustration at these circumstances, which amplified caregivers’ distress in their inability to communicate with the patient (theme 7). Many caregivers described a feeling of sadness and a feeling of “letting down” or disappointing patients because of their inability to communicate with each other.

Emotional Stressors

Caregivers described experiencing increased uncertainty (theme 8) relating to prognosis, the timing of discharge and transfer to subacute care, and patients’ preferences for medical decisions. In addition, they described having trouble making sense of the multiple simultaneous losses occurring in their lives within a small time frame (theme 9), including the loss of normalcy, the loss of familiar routines, and anticipated loss of their familiar roles, responsibilities, and shared life with the patient. Because of these stressors, caregivers described experiencing challenges due to co-occurring complex and overwhelming emotions (theme 10). They described the hospitalization as producing “a roller coaster of emotions” with cascading experiences of devastation, helplessness, frustration, and guilt, as well as periods of “shock” marked by difficulties concentrating, feelings of being overwhelmed, and emotional numbness. Caregivers described these experiences as difficult to pinpoint and often contradictory, which alienated them from other family and friends and made it difficult to effectively plan for the uncertain future.

Domain 2: Coping Strategies

We identified eight themes pertaining to the coping strategies enacted by caregivers in response to the stressors they experienced during ICU hospitalization, which we organized into psychological and behavioral categories (Table 3).

Table 3.

Description of themes and illustrative quotes for psychological and behavioral coping strategies

| Theme | Theme definition | Illustrative quotations |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Avoidance or distraction in response to difficult emotions and experiences | Caregiver behavior of suppressing or turning away from difficult thoughts or emotions to deal with their situation, distracting themselves from the emotional difficulty of the current situation through various methods | “The mind is pretty incredible to be able to just detach myself from this reality, and I think like a couple days after I had been really, still just like very upset, crying. You know, [patient’s name], it wasn’t guaranteed that he would, you know, be okay, living, and I think a couple days after I got a feeling of void. Like I felt nothing, which was weird, but actually kind of welcomed to just feel nothing.” “I was kind of ignoring a lot of it. I wasn’t eating right, I wasn’t showering like I should, I wasn’t taking care of myself or the house. I was just kind of in autopilot, and then things kind of started to hit me. And I had some unhealthy coping habits. I was overeating and eating just absolutely crappy food. And you know, pretty snippy with my partner, and just kind of not doing anything and just kinda wanted to watch TV and zone out and not think about anything.” |

| 2. Cultivating positive emotions | Caregiver behavior of maintaining positivity in the situation (e.g., optimism, hope, gratitude) | “I do believe in God, and I do believe we all have a certain amount of time. And we have struggles we have to go through, and they’re supposed to increase your faith, even though they don’t always. You have your good days and your bad days. And so, I try to talk to myself about that.” “I like to journal not to myself, like to [patient]. In hopes that she’ll read it one day or I can read it to her, or whatever. But it kind of also helps me to process everything from the day. Like I have a list of the good of today, the bad of today, or the hard. Kind of helps me refocus in a way and also like look for the wins. Like sometimes, a day feels really bad, and I have like two columns—and it’s like the good, the hard. And I realize I’m like writing everything in the column that says like the hard stuff. And then it helps me kind of look for the good things that happened during the day, whether it’s moving her leg for the first time, or squeezing my hand or whatever.” |

| 3. Mindfulness, acceptance, and problem-solving | Caregiver using internal strategies (e.g., mindfulness, present moment focus) to identify and problem solve challenges | “If there something that’s worrying me, I always try to figure out what can I do to either solve the problem, and if I can’t solve it, you know, what can I do to make sure that I’ve done all I can to fix it, you know? So I guess I always try to fix what’s not working and hope that’ll solve what’s causing the stress.” “Staying in the moment and being able to not panic, necessarily, and keeping an even keel. Because you certainly wouldn’t want to be in a situation where like, you’re having an emotional breakdown, and so they’re asking you to leave the hospital room or, you know, whatever, so that’s preventing you from being able to be there for your loved one.” |

| 4. Self-education | Caregiver behavior of independent research and self-education to cope with current situation (e.g., Internet searches, second opinions) | “I really had to look at the facilities that he was going to make sure, you know, of course, I’m a research person just like yourself. So I believe in looking up reviews, looking up anything I can find on the facility to make sure that he’s going to the best place. And I feel confident after speaking to people on the phone and reading so much stuff over the Internet that he’s going to a good facility that will help with his physical therapy and his ventilator stuff.” “I kind of did my own research about it and kind of did like, alright, what can you do to help this, what’s the pros and cons of it? Because I wanted to know either way how it could go before I went in and asked any questions. And then, when I did do some research on it, I was also asking the nurse, okay, well, is this true, and is that true? And just to kind of make sure that the research that I got from it was actual facts because you know, you obviously can’t think everything that you see on the Internet is true. So, I kind of just to like back it up a little bit, and then they elaborated on it—well, yes that is true, but your dad is this way, or he’s doing this, or he’s showing signs of this, so it kind of was like, I don’t know, it was kind of soothing for me to do my own research and then go in and ask questions on top of it. And it also surfaced more questions because you know, you do your research on something, you read about something, you’re going to have questions about it.” |

| 5. Healthy lifestyle behaviors and self-care | Caregiver behavior of performing positive activities (e.g., exercise, cooking, relaxing activities) to cope with stress and difficult emotions | “I’ll turn my music on, and I cook, I love to cook, so I’ll be cooking, I’ll bake, I have my music on. My kids like to cook with me, so I’ll just involve them in stuff. So, I just kind of like, I don’t know, how do I say it, like get more involved with life. I’ll do that, or I’ll just cry it out.” “I have a seven-month-old Golden Retriever, and she helps me cope a lot because she gets me outside four times a day [unclear], take her out in the sun. And it’s just good I think for me to get out of the house. Just, I don’t know, I’ll go to the beach one day, go out for walks, kind of be better about seeing friends sometimes. I mean, sometimes, it’s just been watching TV and doing, I don’t know, things that help me feel normal.” |

| 6. Family and social support | Caregiver engaging support from family, friends, coworkers, managers/superiors, social network | “I mean, my old coworkers from where I worked in Boston—they have been so great. It was good for our relationship because they know what I’m going through. Not to the extent of personally knowing, but that was helpful. And my boss—I work for a neurologist—he literally, I think talked me off the edge about three or four times. He talked to the team for me; the team would tell me things, and in that moment I was sort of overwhelmed where I couldn’t focus on what was happening, and then I would talk to him, and then he would be like did you ask about this? And I would be like, no, I didn’t even think to ask about that. And then I would say, do you mind calling them, can they call you, and can you go over these things with them, and they did. He was able to explain it in a way that I could understand better, you know.” “Family’s very helpful. I have three sisters left out of five, and I talk to them more than I’ve ever talked to them, and that helps a lot. I mean, I’m on the phone a lot with my sisters. So, and we talk about this thing since… it’s almost like I didn’t have enough time before to talk to them.” |

| 7. Positive relationships with medical providers | Caregiver behavior of building relationships with medical providers focused on communicating trust and confidence that medical providers are properly taking care of the patient, even if caregiver does not understand all medical details | “A lot of people, myself included, you have to learn to ask questions, and it’s important to do that because if you don’t know, just ask. Because they’ll—usually, everybody is very accommodating—and they’ll explain to you what’s going on.” “I just will try to make sure I’m there in the morning when they do their report. But when they’re in report, I’m in report with them. So, you know, everything that’s going on with her, they communicate, and they have me right there, so I’m getting it firsthand.” |

| 8. Making meaning through experiences | Caregiver behavior of turning their difficult experience into something of meaning (e.g., being a resource for other people, volunteering, giving back) | “That’s what I’m here for. If anyone else can stop from going through what I’m going through, and I can help out, that’s my job. That’s what I’m going to do. Well, it’s not my job, but that’s what I’m going to do. I’m going to help anybody that I can.” “Like, for instance, you can put lotion on their arms and legs, you can ask the nurses for these little swab sticks, and there’s a liquid to help clean that person’s mouth. We got dry shampoo for my mom’s hair, Chapstick for her lips. I think that a lot of people are not aware that they can do these things when they’re in the hospital.’Cause they’re like, ugh, I don’t want to interfere with what the nurse’s doing. But they’re the kind of things that kind of help to maintain your loved one’s dignity when in the hospital, where you don’t really have as much because you’re sitting there in a hospital gown open to the world. So, I think little things like that that family members can do, and it gives them a sense of ability to contribute.” |

Psychological Coping Strategies

Nearly all caregivers described the initial adjustment to the hospitalization and patients’ conditions as a period marked by avoidance or distraction amid difficult emotions and experiences (theme 1). For some caregivers, this strategy was described as adaptive in the sense that it provided caregivers with temporary relief or escape from being overwhelmed by the acute trauma and co-occurring stressors (e.g., using statements such as “I got a feeling of void…actually kind of welcomed to just feel nothing”). For others, avoidance occurred through negative health behaviors (e.g., with phrases such as “I was kind of ignoring a lot of it” and “I had some unhealthy coping habits”).

To cope with uncertainty, loss, and heightened stress, caregivers in the study emphasized the importance of adaptive coping strategies to allow them to regulate their emotions and process the trauma. These included cultivating positive emotions (theme 2) through reflection, prayer, and daily routines and the use of mindfulness and acceptance. Some caregivers noted that they were able to practice mindfulness-based and acceptance-based strategies and identify and solve problems (theme 3). Specifically, they provided examples of the ways in which spirituality or gratitude practices allowed them to “refocus” and “look for the wins,” including the patient’s continued survival. Conversely, regarding negative events, they emphasized the importance of “not dwelling” and “accepting things that you can’t change.”

Behavioral Coping Strategies

To navigate challenges with medical care, caregivers emphasized the importance of self-education on the patients’ medical condition, ICU treatment options, and ways of navigating care after hospitalization (theme 4). They also described the importance of maintaining lifestyle behaviors and self-care through daily routines, including “staying active” and managing stress through exercise, cooking, and recreational activities (theme 5). Caregivers described these behaviors as helping them maintain normalcy and a sense of control. Most emphasized the importance of engaging family and social support (theme 6) amid the emotional, practical, and financial challenges of hospitalization and challenges navigating medical decisions (e.g., with statements such as “Everything was done by committee”).

Caregivers cited positive relationships with medical providers (theme 7) as being an important aspect of their emotional adjustment during hospitalization. Several noted the benefits of attending medical rounds to hear firsthand how providers communicated about the patient’s prognosis and care and to encourage themselves to write down and ask questions.

In addition, caregivers described the benefits of identifying actions that would “help [them] feel like [they] have some purpose” and allow them to transform their experiences to make meaning from their experiences (theme 8), including assisting in the patient’s care during hospitalization, helping other families in similar circumstances, volunteering, engaging in other caregiving roles, and participating in research and advocacy efforts. They described this strategy as a way of cultivating positives and helping them connect to a broader sense of purpose.

Discussion

In this multicenter qualitative study, we sought to characterize the psychosocial stressors and coping strategies reported by family caregivers of patients with SABI with varying degrees of initial recovery from coma, all near the time of transition out of the ICU following a recent decision to proceed with tracheostomy and/or feeding tube placement. Using a stress and coping framework [11, 12], we describe in detail the stressors that these caregivers experience along practical, social, and emotional categories. For all caregivers, stressors were described as substantial and compounding, which made it difficult to manage emotional reactions and process complex emotions. They attempted to cope in various ways and acknowledged that some coping strategies were more helpful than others. Specifically, many caregivers coped with overwhelming emotions using avoidance and distraction strategies, which provided short-term relief. For some, avoidance was adaptive, in that it allowed them to function amid intense emotions. However, all caregivers acknowledged that avoidance and distraction over time prevented them from engaging in more adaptive strategies with long-term benefit, such as cultivating positive emotions (e.g., optimism, hope, gratitude), engaging in problem-solving and healthy lifestyle behaviors, cultivating positive relationships with providers, engaging social support, and reflecting on their experiences to make meaning. Despite their awareness of the benefits of these strategies, most caregivers in the study noted that they had challenges consistently engaging in positive strategies in the presence of overwhelming emotions and distress.

There is currently unprecedented excitement among the medical community regarding a goal of “curing coma” and giving patients with SABI substantial time, when appropriate, to recover and achieve their best eventual outcomes [22-25]. Although a willingness to offer life-sustaining measures for patients is important for advancing the field of coma recovery, aggressive care for patients with SABI can come at profound psychosocial cost for many of these patients’ families [26]. To our knowledge, this is the first multicenter qualitative study of coma survivor caregivers that specifically used a stress and coping framework to interview caregivers during the unique period immediately following a decision to pursue tracheostomy and/or feeding tube placement in the ICU. This timing allowed our team to gather perspectives at a critical time point by which important goals-of-care discussions had already been made but at which caregivers were still actively processing their ICU experiences and were faced with uncertain next steps regarding the patient’s coma recovery. Our findings can directly inform the development of interventions to support caregivers of coma patients, beginning during ICU admission and continuing through transition to lower levels of care, with the goal of preventing transition from acute to chronic emotional distress following discharge. Equipping caregivers with coping skills necessary to manage stress and challenging emotions early in the loved one’s coma recovery journey has the potential to prevent chronic emotional distress in caregivers and improve quality of patient care [22-25]. These interventions are critically needed because more comatose patients are potentially given periods of time extending beyond the ICU to observe their clinical trajectories and quality of life [23].

Our study supports some findings in prior qualitative studies of caregivers of patients with SABI regarding psychosocial stressors experienced at various time points both during and following acute hospitalization [1, 3, 27-31]. We extended previous findings by comprehensively characterizing stressors in practical, social, and emotional categories in a geographically diverse sample of caregivers from across the United States. Importantly, we additionally describe caregivers’ attempted methods of coping with stressors. Nearly all caregivers in our study described using avoidance or distraction as an initial coping strategy. As prior investigations of caregiving populations outside the ICU have illustrated, avoidance can provide short-term relief from difficult experiences but can lead to reductions in positive coping behaviors, lower engagement in support, and barriers planning for the future [32-34]. Our findings also revealed caregivers’ awareness of positive psychological and behavioral coping strategies, such as cultivating positive emotions, mindfulness, acceptance, problem-solving, self-education, and healthy lifestyle behaviors; soliciting social support and positive relationships with providers; and meaning-making through reflection on their experiences. However, many caregivers’ acknowledged the difficulty enacting more adaptive coping strategies on their own, which highlights their need for additional psychosocial support.

We identified several possible limitations. First, regarding our convenience sample, we acknowledge our family participants were predominantly White, female, and educated. Approximately half of those family participants who were approached for study consent did not participate, demonstrating the challenge of recruiting study participants during their immense stress and potentially contributing to selection bias for those who decided to participate. We highlight though that our proportion of Black participants was higher than that of the general US population, that we were able to achieve thematic saturation, and that the generalizability of our findings was strengthened by recruitment from 14 neuroscience ICUs in diverse US geographical locations. Second, although all of our participants were family members for patients with SABI who were requiring tracheostomy and/or feeding tube placement for survival, our definition of initial coma was based on examination findings easily obtainable by bedside clinicians, and patients were mixed in terms of the degree of their neurologic recovery at the time of family enrollment. We believe that this broad, practical approach to enrollment, rather than focusing solely on families of patients projected to meet strict long-term definitions of disorders of consciousness, also improved the generalizability of our findings, reflective of a real-world experience. However, we did not include SABI caregivers who chose not to pursue tracheotomy and/or feeding tube placement, and it is possible that their experiences during acute hospitalization would differ from those of participants in our study. Third, we included only those families who had already decided to prolong life-sustaining therapy beyond the decision regarding tracheostomy and/or feeding tube placement. Although caregivers who elect to pursue comfort measures for patients with SABI are at high risk for experiencing stress during and after the ICU as well, we designed this study specifically to inform a future support intervention for those families who are transitioning out of the ICU to becoming long-term caregivers for patients with SABI. Examining the stressors and coping strategies of families of patients who pass away before tracheostomy and/or feeding tube placement is an important area of focus for a future study that would require recruiting a different population.

Finally, it is possible that caregivers’ experiences could differ across differing ICU lengths of stay and in the weeks and months following discharge. However, the selected timing of our interviews did allow for the characterization of caregivers’ experience beyond the initial shock of hospitalization but still during a period of heightened distress and uncertainty. Future studies could examine caregivers’ experiences of stressors and coping strategies over time and could characterize their preferences for additional psychosocial support during hospitalization and after discharge. Although we did not observe differences in themes generated from caregivers based on their relationship with the patient, future studies should also explore potential differences in postdischarge experiences by caregiving relationship to further direct intervention efforts.

Conclusions

Our findings highlight in detail the co-occurring stressors experienced by caregivers of patients with SABI surviving ICU admission for coma and the need for early psychosocial support to teach or support caregivers’ engagement in adaptive coping skills to prevent chronic emotional distress. We used a theoretical approach to guide analyses of interviews such that stressors and both positive and negative coping strategies were characterized comprehensively. Our use of a hybrid deductive–inductive approach allowed for a theoretical and empirical foundation for organizing findings while also providing our team with flexibility in identifying themes within each domain. This allowed identification of modifiable factors to target in future psychosocial interventions.

Psychosocial interventions delivered early to other (noncoma) brain injury and ICU populations that include skills and education focused on coping with difficult emotions and heightened stress have demonstrated feasibility and clinical utility in improving caregivers’ emotional distress through practical guidance and delivery using accessible formats [13, 35]. Additional research is needed to understand our particular group of caregivers’ preferences for psychosocial support delivery during and following hospitalization, to understand which caregivers are in need of psychosocial support, and to explore whether it may be possible to adapt approaches developed among other populations to address their unique needs.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge Varina L. Boerwinkle and Brian L. Edlow for their editorial and conceptual input in this project. We would also like to acknowledge the American Academy of Neurology Transforming Leaders Program for their conceptual support during data collection. Investigators in the Coma Family (COMA-F) study are listed in the eAppendix Supplement.

Source of Support

This work was supported by the Department of Neurology Research Fund at the Yale School of Medicine awarded to David Y. Hwang, a grant from the National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health awarded to Ana-Maria Vranceanu (1K24AT011760-01), and a grant from the National Institute of Nursing Research awarded to Ana-Maria Vranceanu (5R01NR019982-02). The funders/sponsors for this study did not play any role in the conception or design of this study, acquisition or analysis of data, or drafting of the manuscript.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest

Ana-Maria Vranceanu reports serving on the Scientific Advisory Board for the Calm application and royalties from Oxford University Press outside of the submitted work. The other authors report no conflicts of interest.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at https://doi.org/10.1007/s12028-023-01804-3.

Ethical Approval/Informed Consent

The study was approved by each institution’s institutional review board. The authors confirm use of informed consent.

References

- 1.Muehlschlegel S, Perman SM, Elmer J, et al. The Experiences and Needs of Families of Comatose Patients After Cardiac Arrest and Severe Neurotrauma: The Perspectives of National Key Stakeholders During a National Institutes of Health-Funded Workshop. Critical Care Explorations. 2022;4(3):e0648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cai X, Robinson J, Muehlschlegel S, et al. Patient preferences and surrogate decision making in neuroscience intensive care units. Neurocrit Care. 2015;23(1):131–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schutz RE, Coats HL, Engelberg RA, Curtis JR, Creutzfeldt CJ. Is there hope? Is she there? How families and clinicians experience severe acute brain injury. J Palliat Med. 2017;20(2):170–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Scheunemann LP, Arnold RM, White DB. The facilitated values history: helping surrogates make authentic decisions for incapacitated patients with advanced illness. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2012;186(6):480–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Siegel MD, Hayes E, Vanderwerker LC, Loseth DB, Prigerson HG. Psychiatric illness in the next of kin of patients who die in the intensive care unit. Crit Care Med. 2008;36(6):1722–8. 10.1097/CCM.0b013e318174da72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cameron JI, Chu LM, Matte A, et al. One-year outcomes in caregivers of critically ill patients. N Engl J Med. 2016;374(19):1831–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cipolletta S, Pasi M, Avesani R. Vita tua, mors mea: the experience of family caregivers of patients in a vegetative state. J Health Psychol. 2016;21(7):1197–206. 10.1177/1359105314550348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Noohi E, Peyrovi H, Imani Goghary Z, Kazemi M. Perception of social support among family caregivers of vegetative patients: a qualitative study. Conscious Cogn. 2016;41:150–8. 10.1016/j.concog.2016.02.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Magnani FG, Leonardi M, Sattin D. Caregivers of people with disorders of consciousness: Which burden predictors? Neurol Sci. 2020;41(10):2773–9. 10.1007/s10072-020-04394-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lewis A, Claassen J, Illes J, et al. Ethics priorities of the curing coma campaign: an empirical survey. Neurocrit Care. 2022;1:1–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Biggs A, Brough P, Drummond S. Lazarus and Folkman’s psychological stress and coping theory. The handbook of stress and health: A guide to research and practice. 2017;1:351–64. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lazarus RS, Folkman S. Stress, appraisal, and coping. Springer publishing company; 1984. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vranceanu A-M, Bannon S, Mace R, et al. Feasibility and efficacy of a resiliency intervention for the prevention of chronic emotional distress among survivor-caregiver dyads admitted to the neuroscience intensive care unit: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3(10):e2020807–e2020807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.McCurley JL, Funes CJ, Zale EL, et al. Preventing chronic emotional distress in stroke survivors and their informal caregivers. Neurocrit Care. 2019;30(3):581–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bannon S, Lester EG, Gates MV, et al. Recovering together: building resiliency in dyads of stroke patients and their caregivers at risk for chronic emotional distress; a feasibility study. Pilot Feasibil Stud. 2020;6(1):1–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Guest G, Namey E, Chen M. A simple method to assess and report thematic saturation in qualitative research. PLoS ONE. 2020;15(5): e0232076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fereday J, Muir-Cochrane E. Demonstrating rigor using thematic analysis: a hybrid approach of inductive and deductive coding and theme development. Int J Qual Methods. 2006;5(1):80–92. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Quinn K, Murray C, Malone C. Spousal experiences of coping with and adapting to caregiving for a partner who has a stroke: a meta-synthesis of qualitative research. Disabil Rehabil. 2014;36(3):185–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Meyers EE, McCurley J, Lester E, Jacobo M, Rosand J, Vranceanu A-M. Building resiliency in dyads of patients admitted to the Neuroscience Intensive Care Unit and their family caregivers: Lessons learned from William and Laura. Cogn Behav Pract. 2020;27(3):321–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hesamzadeh A, Dalvandi A, Maddah SB, Khoshknab MF, Ahmadi F. Family adaptation to stroke: a metasynthesis of qualitative research based on double ABCX model. Asian Nurs Res. 2015;9(3):177–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tong A, Sainsbury P, Craig J. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): a 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int J Qual Health Care. 2007;19(6):349–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mainali S, Aiyagari V, Alexander S, et al. Proceedings of the Second Curing Coma Campaign NIH Symposium: Challenging the Future of Research for Coma and Disorders of Consciousness. Neurocrit Care. May 10 2022. 10.1007/s12028-022-01505-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Giacino JT, Katz DI, Schiff ND, et al. Practice guideline update recommendations summary: disorders of consciousness: report of the Guideline Development, Dissemination, and Implementation Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology; the American Congress of Rehabilitation Medicine; and the National Institute on Disability, Independent Living, and Rehabilitation Research. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2018;99(9):1699–709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Olson DM, Hemphill JC. The curing coma campaign: challenging the paradigm for disorders of consciousness. Neurocrit Care. 2021;35(1):1–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Claassen J, Akbari Y, Alexander S, et al. Proceedings of the first curing coma campaign NIH symposium: challenging the future of research for coma and disorders of consciousness. Neurocrit Care. 2021;35(1):4–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lou W, Granstein JH, Wabl R, Singh A, Wahlster S, Creutzfeldt CJ. Taking a chance to recover: families look back on the decision to pursue tracheostomy after severe acute brain injury. Neurocrit Care. 2022;36(2):504–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Keenan A, Joseph L. The needs of family members of severe traumatic brain injured patients during critical and acute care: a qualitative study. Can J Neurosci Nurs. 2010;32(3):25–35. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Karimollahi M, Tazakori Z, Falahtabar R, Ajri-Khameslou M. The perceptions of families of comatose patients in the intensive care unit: a qualitative study. J Client-Center Nurs Care. 2021;7(1):9–16. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gonzalez-Lara LE, Munce S, Christian J, Owen AM, Weijer C, Webster F. The multiplicity of caregiving burden: a qualitative analysis of families with prolonged disorders of consciousness. Brain Inj. 2021;35(2):200–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kreitzer N, Bakas T, Kurowski B, et al. The experience of caregivers following a moderate to severe traumatic brain injury requiring ICU admission. J Head Trauma Rehabil. 2020;35(3):E299–309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Verhaeghe S, Defloor T, Van Zuuren F, Duijnstee M, Grypdonck M. The needs and experiences of family members of adult patients in an intensive care unit: a review of the literature. J Clin Nurs. 2005;14(4):501–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Shear MK. Exploring the role of experiential avoidance from the perspective of attachment theory and the dual process model. OMEGA-J Death Dying. 2010;61(4):357–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bonanno GA, Keltner D, Holen A, Horowitz MJ. When avoiding unpleasant emotions might not be such a bad thing: verbal-autonomic response dissociation and midlife conjugal bereavement. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1995;69(5):975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bannon SM, Grunberg VA, Reichman M, et al. Thematic analysis of dyadic coping in couples with young-onset dementia. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4(4):e216111–e216111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Garner J, Kelly S, Sadera G, Treadway V. How information sharing can improve patient and family experience in critical care: A focus group study. Patient Experience Journal. 2020;7(3):109–11. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.