Abstract

Purpose

This study aimed to assess the feasibility of the Apple AirPods Pro with the headphone accommodation feature as a hearing assistive device for patients with mild to moderate hearing loss (HL).

Materials and Methods

The study included a total of 35 participants with mild to moderate HL. To determine the degree of HL in the participants, a screening test using pure-tone audiometry was conducted prior to the main tests of functional gain, word recognition score (WRS), and sentence recognition in noisy environments. The study employed two hearing devices: the Bean (a personal sound amplification product, PSAP) and the AirPods Pro.

Results

Regarding functional gain, there were no significant differences between the Bean and the AirPods Pro at all frequencies, except 8 kHz. In terms of WRS, both the Bean and the AirPods Pro had higher scores than the unaided condition. In sentence recognition, both the Bean and the AirPods Pro had higher scores than the unaided condition. During real-ear measurement, the Bean demonstrated consistent frequency responses, while the AirPods had a deviation exceeding 10 dB SPL at 6 kHz in the left ear. This deviation was absent for all other frequencies.

Conclusion

This study shows that the Apple AirPods Pro, with its headphone accommodation feature, performed similarly to a validated PSAP and improved hearing compared to unaided conditions.

Keywords: Sensorineural hearing loss, hearing aids, personal sound amplification products, hearables, health services accessibility

Graphical Abstract

INTRODUCTION

According to a report by the World Health Organization in 2021, about 5% of the world’s population experiences hearing loss (HL).1 HL has a significant impact on communication, social participation, as well as the overall health and quality of life. Moreover, HL is the most easily modifiable risk factor for dementia.2 Therefore, proactive hearing rehabilitation is necessary.

Hearing aids (HAs) serve as first-line management for patients with HL. However, there are several barriers that can prevent individuals from using HAs, including high cost and limited insurance coverage.3,4,5,6 HAs can be expensive (ranging from US$3000 to US$6000 a pair), and some affected individuals are not able to afford them. Also, the social stigma associated with HA wear may contribute to the low rate of HA use.5,6 Many individuals with HL may feel embarrassed or ashamed to wear HAs and avoid seeking treatment.

Recently, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) established a regulatory category of over-the-counter (OTC) HAs, which are a type of medical device that can be purchased without a prescription or consultation with a licensed hearing healthcare professional.7 The expectation is that the availability of OTC HAs will increase access to affordable hearing care for millions of patients with HL who are currently underserved by the traditional HA market.

Considering this, various types of hearing devices have been proposed as alternatives to traditional HAs. Personal sound amplification products (PSAPs) are electronic devices designed to amplify sound for people with normal hearing. PSAPs are similar in design, function, and features to traditional HAs. These are not, however, regulated by the FDA and are not intended to be used as medical devices to treat HL. Nevertheless, PSAPs are sometimes considered an initial treatment option for patients with HL. In the MarkeTrak 10 research, nearly 40% of the 193 respondents identified their PSAP as a HA; and another 40% referred to the PSAP as an amplifier.8 In addition, some studies have shown that PSAPs performed similarly to HAs in patients with mild to moderate HL in a laboratory setting.9,10

Several smartphone manufacturers have released HA-like features, called hearables. A hearable is a type of wearable technology that is designed to enhance or augment a person’s hearing ability. Hearables are typically small, wireless devices that can be worn in or on the ear and often include features such as noise cancellation, sound amplification, and voice assistant capabilities.

The proportion of individuals owning smartphones, regardless of age, has increased over time.11 As of 2021, approximately 6.3 billion people, or about 67% of the global population, own a smartphone.12 In the fourth quarter of 2022, Apple had the largest smartphone market share worldwide, followed by Samsung.13

Apple Inc. has developed and applied “Accessibility” as a technical function supporting users in relation to vision, hearing, mobility, and cognition. In relation to hearing, the headphone accommodation feature amplifies the sound in relation to individual audiogram. The feature also fine tunes the audio appropriately for the target through a simple test within a function, adjusting the intensity accordingly.14 Despite Apple Inc.’s large market share, the potential of AirPods as an assistive device for those with HL has not been sufficiently explored. The aim of this study was to examine the potential of Apple’s AirPods Pro with the headphone accommodation feature (AirPods Pro) to be utilized as a hearing assistive device for patients with mild to moderate HL. To achieve this, the study compared the outcome variables under three conditions: unaided, using a PSAP, and using the AirPods Pro.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Participants

Participants were recruited from the outpatient clinic of the Department of Otorhinolaryngology between April 2022 and January 2023. The number of participants was calculated using G*Power Version 3.1.9.7 (Institute for Experimental Psychology, Dusseldorf, Germany) with the conditions of a two-tailed test, parent distribution=min asymptotic relative efficiency (ARE), effect size (dz)=0.09,15 significance level (α)=0.05, and power (1-β)=0.95, resulting in a sample size of 21. Considering the dropout rate, a total of 35 participants were recruited. The inclusion criteria were: 1) patient age ≥18 and <70 years and 2) pure-tone averages (500, 1000, 2000, and 4000 Hz) of 25 dB HL or more and 55 dB HL or less in both ears. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Samsung Medical Center in Seoul (IRB No. 2022-04-094). All participants signed an informed consent form before enrollment. Before the main test, participants were screened in the clinic with pure-tone audiometry (PTA) to determine eligibility.

Outcome measures

Screening test

PTA

HL was screened by PTA using a calibrated GSI Audio Star audiometer (Grason-Stadler, Inc., Eden Prairie, MN, USA) with TDH-39 headphones in a sound-proof room. The PTA was performed in each ear at frequencies of 0.25 and 8 kHz according to a standard procedure.16 The pure-tone average was calculated for each ear at frequencies of 0.5, 1, 2, and 4 kHz. The participants with a pure-tone average of 25 dB HL or more and 55 dB HL or less in both ears were enrolled in the study.

Main tests

Functional gain

Functional gain was carried out as stipulated in the International Organization for Standardization (ISO) 8253-2 (2009). Functional gain refers to the difference in dB HL between the aided and unaided free sound-field thresholds at test frequencies of 0.25 to 8 kHz. Participants were seated in a double-walled sound-attenuating booth 1 meter from a loudspeaker at 0° azimuth. Frequency modulation tones were presented as a test stimulus. The participants responded by pressing a button when hearing the stimulus.

Word recognition score

The word recognition score (WRS) was determined according to the ISO 8253-3 (2012) using the same audiometer as used for PTA. After connecting the CD player (YAMAHA TSX-B232; YAMAHA Corp., Shizuoka, Japan) to the audiometer, 25 monosyllabic words from the Korean standard-monosyllabic word list (KS-MWL-A)17 were presented at 50 dB HL. Participants were seated in a double-walled sound-attenuating booth 1 meter from a loudspeaker at 0° azimuth and asked to repeat the presented word back to the tester. The percentage of correct words was calculated for scoring.

Sentence recognition

The Korean Standard–Sentence Lists for Adults (KS-SL-A)18 was utilized for the speech recognition in noise. The KS-SL-A consisted of eight lists of 10 sentences and 40 words each. The eight lists were randomized to minimize order effects. After the participant was seated in the middle of the five speakers, sentences were presented at 50 dBA from the front speaker, while four-talker babble noise was presented from four speakers at 45, 135, 225, and 315°. Babble noise was also presented at 50 dBA. The presentation level was calibrated with a sound level meter (Hand-held Analyzer Type 2250-L, Brüel & Kjær, Virum, Denmark). The participants were asked to repeat the presented sentence back to the tester. The number of correct answers was calculated for scoring.

Real-ear measurement

The real-ear measurement (REM) was conducted using the Aurical Free Fit (Natus, Middleton, WI, USA). First, the external ear canal of the participant was checked for earwax or any foreign substances. Then, a probe tube was inserted. The measurement stimulus sound was projected from a speaker placed 1 meter at 0° azimuth from the participant. The stimulus sound employed was an Inter Speech Test Signal, presented at an intensity of 65 dB SPL, which is comparable to the average conversation speech. The appropriateness of the hearing device level was determined by evaluating the difference between the National Acoustics Laboratories-Non-Linear prescription, 2nd generation (NAL-NL2) targets and the aided response at seven frequencies (0.25, 0.5, 1, 2, 3, 4, and 6 kHz). If the difference fell within 10 dB SPL for five or more of the seven frequencies, it was considered an “appropriate level” for that specific hearing threshold.9

Hearing devices

The study utilized two hearing devices: the Bean (The Bean™, Etymotic Research, Elk Grove Village, IL, USA) and the Apple AirPods Pro with headphone accommodation feature. The Bean was chosen due to its popularity among PSAPs and its similarity to the in-ear design of the Apple AirPods Pro.

Procedure

Participants who passed the screening test proceeded with the main tests. Before conducting the main tests, the audiologists entered each participants’ PTA results into an audiogram of the Apple Health application to customize audio settings. The AirPods Pro was set to the headphone accommodation feature, fit bilaterally, and paired with an iPhone running iOS 15.6. The Bean was set to normal and high sound volume modes. Each participant was tested at their level of comfort. All tests were conducted under three conditions: unaided, using the Bean, and using the AirPods Pro. The order of the conditions was varied across participants to eliminate any potential ordering effects.

Statistical analysis

The assessment of variable distribution normality through the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test revealed non-normality, as indicated by p-values below 0.05 for all variables, thus necessitating the application of non-parametric analytical methods. Descriptive statistical analysis utilized the median and interquartile range (IQR) for continuous variables and frequency counts and percentages for categorical variables. For the comparative analysis of functional gain between the Bean and the AirPods Pro, the Mann-Whitney U test was conducted. Furthermore, the Friedman test was employed to compare additional clinical outcomes across different conditions, with the Wilcoxon signed-rank test serving as a post-hoc analysis tool. To address the potential for type I error associated with multiple comparisons, a Bonferroni correction was implemented. All statistical analyses were executed using SPSS software, version 29.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA).

RESULTS

Participant characteristics

The present study encompassed a cohort of 35 individuals diagnosed with mild to moderate HL. The median age of the participants was recorded at 63 years, with an IQR spanning from 61.00 to 67.00 years. Within this group, men constituted 31.4% (n=11), while women accounted for 68.6% (n=24). Audiometric evaluation revealed the pure-tone average for the right ear to be 38.75 dB HL, with an IQR of 35.00 to 46.25 dB HL. Similarly, the pure-tone average for the left ear was determined to be 42.50 dB HL, accompanied by an IQR of 36.25 to 47.50 dB HL (Table 1).

Table 1. Participant Characteristics (n=35).

| Variables | Value | |

|---|---|---|

| Age (yr) | 63.00 (61.00–67.00) | |

| Sex | ||

| Men | 11 (31.4) | |

| Women | 24 (68.6) | |

| Pure-tone average | ||

| Right (dB HL) | 38.75 (35.00–46.25) | |

| Left (dB HL) | 42.50 (36.25–47.50) | |

Data are presented as median (interquartile range) or n (%). Pure-tone average was calculated for each ear at frequencies of 0.5, 1, 2, and 4 kHz.

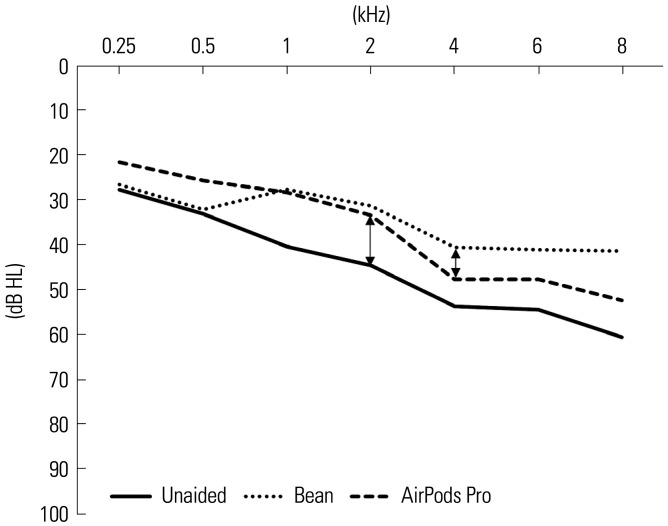

Functional gain

The functional gain was obtained by subtracting the unaided threshold from the aided threshold. There was no significant difference between the Bean and the AirPods Pro at frequencies of 0.25 (p=0.122), 0.5 (p=0.052), 1 (p=0.875), 2 (p=0.854), 4 (p=0.226), and 6 (p=0.213) kHz. At 8 kHz, the Bean showed significantly better functional gain compared to the AirPods Pro (p=0.036) (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1. Results of functional gain. Functional gain refers to the difference in dB HL between the aided and unaided free sound-field thresholds at test frequencies of 0.25 to 8 kHz.

WRS

The presence of significant differences in the WRS across three conditions (unaided, Bean, AirPods Pro) was examined using the Friedman test, which indicated a significant variant among the conditions (p=0.003). Subsequent post-hoc analysis revealed significant differences between the unaided condition and the Bean (p=0.007), as well as between the unaided condition and the AirPods Pro (p<0.001). However, no significant difference was observed between the Bean and the AirPods Pro (p=0.810) (Table 2).

Table 2. Speech Intelligibility Outcomes According to Hearing Device Conditions.

| Variables | Group | Median | IQR | p value | Post-hoc | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| U vs. B | U vs. A | B vs. A | |||||

| WRS (%) | Unaided (U) | 60.00 | 48.00–76.00 | 0.003** | 0.007** | <0.001*** | 0.810 |

| Bean (B) | 84.00 | 72.00–92.00 | |||||

| AirPods Pro (A) | 84.00 | 72.00–88.00 | |||||

| Sentence recognition: word (max=40) | Unaided (U) | 26.00 | 14.00–35.00 | 0.004** | 0.004** | <0.001*** | 0.432 |

| Bean (B) | 38.00 | 33.00–39.00 | |||||

| AirPods Pro (A) | 37.00 | 28.00–40.00 | |||||

| Sentence recognition: sentence (max=10) | Unaided (U) | 3.00 | 1.00–8.00 | 0.004** | 0.008** | <0.001*** | 0.975 |

| Bean (B) | 8.00 | 6.00–9.00 | |||||

| AirPods Pro (A) | 9.00 | 5.00–10.00 | |||||

IQR, interquartile range; Max, maximum; WRS, word recognition score.

**p<0.01; ***p<0.001.

Sentence recognition

To investigate the presence of significant differences across three conditions in word recognition, a Friedman test was conducted. The results demonstrated significant differences among the conditions (p=0.004), leading to the execution of post-hoc analyses. These analyses revealed significant differences between the unaided condition and the Bean (p=0.004), as well as between the unaided condition and the AirPods Pro (p<0.001). However, no significant difference was found between the Bean and the AirPods Pro (p=0.432).

Similar outcomes were observed in sentence recognition, where significant differences were identified between the unaided condition and the Bean (p=0.008), and between the unaided condition and the AirPods Pro (p<0.001). Conversely, no significant difference was observed between the Bean and the AirPods Pro (p=0.975).

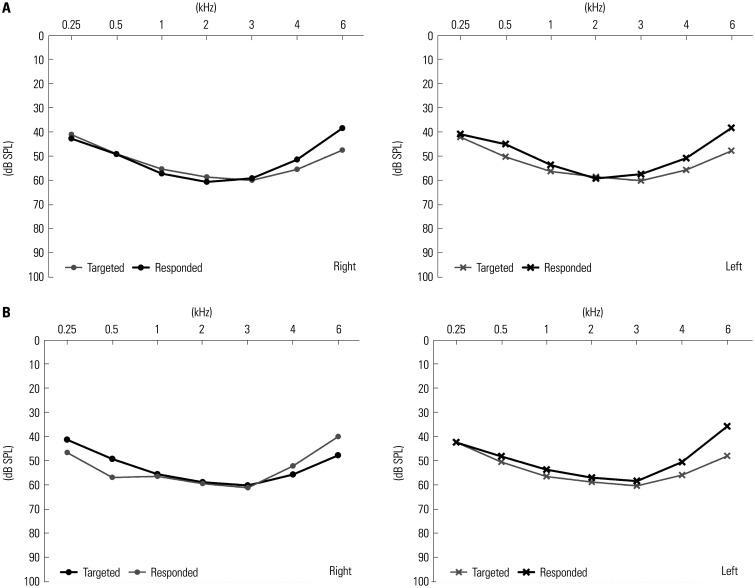

REM

The Bean demonstrated a deviation less than 10 dB SPL between the target and response frequencies in both ears across all seven frequency ranges. However, with the AirPods Pro, the difference between the target and response frequencies exceeded 10 dB SPL at 6 kHz, measuring 12.25 dB SPL in the left ear. Nonetheless, for the remaining six frequencies in the right ear and for all seven frequencies in the left ear, the AirPods Pro maintained a difference within 10 dB SPL (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2. Real-ear measurement (REM) results of the hearing devices in the study. (A) REM results of the Bean and (B) REM results of the AirPods Pro with headphone accommodation feature. The hearing device level appropriateness was determined by comparing NAL-NL2 targets and aided response at seven frequencies (0.25, 0.5, 1, 2, 3, 4, and 6 kHz). Appropriateness was defined as a difference within 10 dB SPL for five or more frequencies.

DISCUSSION

The purpose of the study was to investigate the potential of the Apple AirPods Pro with the headphone accommodation feature as a hearing assistive device and to provide evidence for appropriate recommendations to patients with mild to moderate HL. The results demonstrated better outcomes in all main tests when wearing the AirPods Pro compared to when not wearing any device. Furthermore, during REM, the AirPods Pro appropriately amplified the sound of each frequency according to the traditional target formula.

Functional gain is regarded as the key performance indicator for HA verification. In the present study, there was no significant difference between the Bean and the AirPods Pro at all test frequencies, except 8 kHz. At 8 kHz, the Bean showed significantly better functional gain. The objective measure, REM, also confirmed the Bean’s superior performance at 8 kHz. Previous studies have shown that hearing assistive devices, such as PSAPs, do not provide sufficient gains at high frequencies.9,10 The AirPods Pro did not provide enough gain around 8 kHz mainly due to a feedback problem. However, unlike English, the Korean language does not have speech sounds distributed at 8 kHz,19 and Korean speech understanding may not be affected by the low gain around 8 kHz from the AirPods Pro.

In the study, we conducted two conditions related to speech intelligibility: a quiet condition using WRS and a noisy condition using sentence recognition. Although previous research of PSAPs or hearables showed limited benefit on speech perception in noisy environments,9,10 the AirPods Pro demonstrated a significant improvement in noisy environments in this study. A possible explanation for this difference is that the ambient noise reduction feature of the AirPods Pro can enhance speech clarity in noisy environments by increasing the signal-to-noise ratio.20 However, a recently published study showed no significant difference between aided (with AirPods Pro) and unaided (no AirPods Pro) conditions in the presence of background noise.15 The disparate results are likely due to differences in the type of noise used and the direction of noise presentation.

REM is a method used to objectively verify whether a hearing device is appropriately amplifying sound at the target. The comprehensive analysis of REM results and functional gain in the present study confirmed that both the Bean and AirPods Pro accurately amplified sound at the target, demonstrating their effectiveness. Another notable finding revealed through REM was that both hearing devices could amplify sound in accordance with the widely used NAL-NL2 fitting formula, which is the most used fitting formula for HAs. The main goal of the NAL-NL2 fitting formula is to optimize speech intelligibility and ensure overall comfortable loudness perception.21

In summary, the AirPods Pro showed strong potential as a hearing assistive device in adult patients with mild or moderate HL. Regular use of HAs is low worldwide; the use rate was only 12.6% in Korea.22 The main obstacles to hearing aid use are high price, stigma, and negative concepts. The AirPods Pro could eliminate these traditional obstacles and may be used as a budget-friendly and clinically effective option for hearing rehabilitation in patients with HL. However, the present study has some limitations. First, while the study compared the results to a representative PSAP, there was no comparison to HAs. Second, the study findings were obtained in a laboratory setting, limiting their generalizability. These limitations must be addressed in future studies.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This research was supported by a grant of the Patient-Centered Clinical Research Coordinating Center funded by the Ministry of Health & Welfare, South Korea (grant number: HI19C0481, HC19C0128).

Footnotes

The authors have no potential conflicts of interest to disclose.

- Conceptualization: all authors.

- Data curation: Ga-Young Kim.

- Formal analysis: Ga-Young Kim.

- Funding acquisition: Il Joon Moon.

- Investigation: Ga-Young Kim, Hee Jung Yun, and Mini Jo.

- Methodology: all authors.

- Project administration: Hee Jung Yun and Mini Jo.

- Resources: Ga-Young Kim.

- Software: Ga-Young Kim.

- Supervision: Il Joon Moon.

- Validation: Ga-Young Kim.

- Visualization: Ga-Young Kim.

- Writing—original draft: Ga-Young Kim.

- Writing—review & editing: Ga-Young Kim, Young Sang Cho, and Il Joon Moon.

- Approval of final manuscript: all authors.

DATA AVAILABILITY

The data supporting the findings of this study are available upon reasonable request. Please contact corresponding author to access the data.

References

- 1.World Health Organization. Deafness and hearing loss [Internet] [accessed on 2023 September 11]. Available at: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/deafness-and-hearing-loss.

- 2.Livingston G, Huntley J, Sommerlad A, Ames D, Ballard C, Banerjee S, et al. Dementia prevention, intervention, and care: 2020 report of the Lancet Commission. Lancet. 2020;396:413–446. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30367-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Windmill IM. The financing of hearing care: what we can learn from MarkeTrak 2022. Semin Hear. 2022;43:339–347. doi: 10.1055/s-0042-1758400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Valente M, Amlani AM. Cost as a barrier for hearing aid adoption. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2017;143:647–648. doi: 10.1001/jamaoto.2017.0245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kim GY, Cho YS, Byun HM, Seol HY, Lim J, Park JG, et al. Factors influencing hearing aid satisfaction in South Korea. Yonsei Med J. 2022;63:570–577. doi: 10.3349/ymj.2022.63.6.570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cho YS, Kim GY, Choi JH, Baek SS, Seol HY, Lim J, et al. Factors influencing hearing aid adoption in patients with hearing loss in Korea. J Korean Med Sci. 2022;37:e11. doi: 10.3346/jkms.2022.37.e11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.U.S. Food and Drug Administration. FDA finalizes historic rule enabling access to over-the-counter hearing aids for millions of Americans [Internet] [accessed on 2023 September 11]. Available at: https://www.fda.gov/medical-devices/hearing-aids/otc-hearing-aids-what-you-should-know#:~:text=To%20increase%20the%20public’s%20access,effect%20on%20October%2017%2C%202022.

- 8.Powers TA, Rogin CM. MarkeTrak 10: hearing aids in an era of disruption and DTC/OTC devices. Hear Rev. 2019;26:12–20. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kim GY, Kim JS, Jo M, Seol HY, Cho YS, Moon IJ. Feasibility of personal sound amplification products in patients with moderate hearing loss: a pilot study. Clin Exp Otorhinolaryngol. 2022;15:60–68. doi: 10.21053/ceo.2020.02313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kim GY, Kim S, Jo M, Seol HY, Cho YS, Lim J, et al. Hearing and speech perception for people with hearing loss using personal sound amplification products. J Korean Med Sci. 2022;37:e94. doi: 10.3346/jkms.2022.37.e94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Statista. Percentage of U.S. adults who own a smartphone from 2011 to 2023. [accessed on 2023 September 11]. Available at: https://www.statista.com/statistics/219865/percentage-of-us-adults-who-own-a-smartphone.

- 12.Statista. Global smartphone penetration rate as share of population from 2016 to 2023. [accessed on 2023 September 11]. Available at: https://www.statista.com/statistics/203734/global-smartphone-penetration-per-capita-since-2005.

- 13.Statista. Global smartphone market share from 4th quarter 2009 to 1st quarter 2024, by vendor. [accessed on 2023 September 11]. Available at: https://www.statista.com/statistics/271496/global-market-share-held-by-smartphone-vendors-since-4th-quarter-2009.

- 14.Apple Inc. Accessibility [Internet] [accessed on 2023 September 11]. Available at: https://www.apple.com/accessibility.

- 15.Lin HH, Lai HS, Huang CY, Chen CH, Wu SL, Chu YC, et al. Smartphone-bundled earphones as personal sound amplification products in adults with sensorineural hearing loss. iScience. 2022;25:105436. doi: 10.1016/j.isci.2022.105436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.American Speech-Language-Hearing Association. Guidelines for manual pure-tone threshold audiometry [Internet] [accessed on 2023 September 11]. Available at: https://www.asha.org/policy/gl2005-00014.

- 17.Kim JS, Lim D, Hong HN, Shin HW, Lee KD, Hong BN, et al. [Development of Korean standard monosyllabic word lists for adults (KS-MWL-A)] Audiol. 2008;4:126–140. Korean. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jang H, Lee J, Lim D, Lee K, Jeon A, Jung E. [Development of Korean standard sentence lists for sentence recognition tests] Audiol. 2008;4:161–177. Korean. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lee JH, Jang HS, Chung HJ. [A study on frequency characteristics of Korean phonemes] Audiol. 2005;1:59–66. Korean. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chong-White N, Mejia J, Galloway J, Edwards B. Evaluating Apple AirPods Pro with headphone accommodations as hearing devices. Hear Rev. 2021;28:8–11. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Keidser G, Dillon H, Flax M, Ching T, Brewer S. The NAL-NL2 prescription procedure. Audiol Res. 2011;1:e24. doi: 10.4081/audiores.2011.e24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Moon IJ, Baek SY, Cho YS. Hearing aid use and associated factors in South Korea. Medicine (Baltimore) 2015;94:e1580. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000001580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data supporting the findings of this study are available upon reasonable request. Please contact corresponding author to access the data.