Abstract

Aim

Intimate partner violence (IPV) is becoming a serious public health issue worldwide. This study sought to analyze factors affecting the help‐seeking behavior of male victims of IPV using a web survey.

Methods

Male IPV victims living in Japan were recruited to participate in a web‐based questionnaire survey conducted on February 25 and 26, 2021. A total of 1466 men were divided into two groups: Group 1 (43 men) consisted of victims who sought help and Group 2 consisted of victims (1423 men) who had not sought help. The Domestic Violence Screening Inventory, a 20‐item questionnaire regarding IPV exposure, and the Patient Health Questionnaire‐9 were used, along with the questions regarding help‐seeking behaviors for Group 1.

Results

Of the 43 victims, 28 victims (65.1%) used exclusively informal supports, eight victims (18.6%) used exclusively formal supports, and seven victims (16.3%) used both. Logistic regression analyses revealed that only physical violence was significantly associated with help‐seeking behaviors among types of abuse/violence (odds ratio [OR] = 4.51, confidence interval [CI] = 1.95–10.50, P < .001). Of past experiences, “foregoing divorce to avoid adverse childhood experiences in their offspring” (OR = 3.14, CI = 1.45–6.82, P = .003) was the most significantly associated with help‐seeking behaviors.

Conclusion

In Japan, male IPV victims tend to seek help following physical violence, but males are less are likely to seek help for nonphysical victimization, highlighting the need for targeted support for victims of nonphysical abuse. To provide comprehensive aid to male IPV victims, consultation centers designed for men will be needed.

Keywords: female perpetrators, help‐seeking behaviors, intimate partner violence, male gender roles, male victims

Help‐seeking behavior of male intimate partner violence (IPV) victims in Japan. Male IPV victims tend to seek help following physical violence, but males are less are likely to seek help for nonphysical victimization.

INTRODUCTION

Intimate partner violence (IPV) is defined as “a pattern of assaultive and coercive behaviors, including physical, sexual, and psychological attacks as well as economic coercion, that adults or adolescents employ against their intimate partners.” 1

IPV is becoming a serious public health issue worldwide, since IPV victims often experience grave physical and psychological consequences, including post‐traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), depression, suicide attempts, psychosomatic symptoms, and high blood pressure. 1 , 2

Help‐seeking behavior is any behavior or activity involved in the process of seeking help that is external to the self with regard to “understanding, advice, information, treatment and general support in response to a problem or distressing experience.” 3

To date, several lines of research have investigated male IPV victimization. In Western societies, the incidence of male IPV victimization among the general population ranges from 10% to 46%. 4 , 5 , 6 , 7 , 8 , 9 Men are more likely to be victims of psychological abuse than physical violence. 10 For both sexes, IPV victimization is associated with development of psychiatric disorders, including depression. 10 , 11 With regard to risk factors, each of the following has been suggested to be related to male victimization involving violence/abuse: younger age group (younger, 18–49 years; elder, 50–85 years), 1 unemployed, 12 experiences of abuse in childhood, 13 alcohol misuse, 13 and jealousy. 13 Male victims are less likely to seek help for their victimization than female victims (female 81%, male 57%). 14 , 15 Lysova et al. 16 showed that male victims have four internal and two external barriers as reasons for being hesitant about help‐seeking behavior. The internal barriers are a failure to perceive the abuse; 17 , 18 a sense that one must maintain familial relationships, spare children from developing a negative image of their mother, and get along with their partners without the help of a third party; 18 , 19 the internalization of male gender roles, including the expectation that men should control themselves and their feelings and that men should be independent and superior to women; 17 , 20 and feelings of shame and guilt for internalizing their painful experiences by these partners. 16 , 18 , 21 , 22 The external barriers are a fear that no one will believe they are victims and a lack of people or institutions to turn to. 16 Since male victims have these barriers, they utilize informal supports (family members, friends, coworkers) more than public supports (government resources). 16 , 23

In Asian society, approximately 12% of males are victims of violence/abuse. 24 Male victims of physical violence and/or psychological and sexual abuse are more likely to have lower incomes, lower educational levels, a childhood in a nuclear family setting, and a harmful alcohol consumption habit. 25 Male victims tend to underreport incidents of intimate partner violence 26 and are less willing to seek out social supports. 24 It has been proposed that the reasons for underreporting can be divided three categories: psychological factors, cultural barriers, and decisional challenges. 24

In Arab society, 27 only 1.4% of males are victims of violence/abuse. Male victims experience coercive control, psychological and verbal abuse, emotional neglect, and physical violence by partners. Victims who are subjected to physical violence have insomnia, weight loss, loss of appetite, PTSD symptoms, and irritable bowel syndrome, and often forego divorce to avoid adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) in their offspring. In Arab society, men are expected to be more independent, stronger, and more assertive than women. This concept may prevent the victims from reporting their victimization.

At the start of 2020, the COVID‐19 pandemic overwhelmed the world. Most countries imposed stay‐at‐home orders on their citizenry. As a result, families were forced into prolonged proximity, which often gave rise to new conflicts or inflamed existing ones. The number of IPV‐related consultations thus abruptly increased and there was a concern regarding a potential increase in the severity of IPV victimization from intimate partners experiencing COVID‐19‐related stress and anxiety. 28 To address these issues, the Japanese government expanded the public consultation services for IPV victims in the spring of 2020. 28 As a result, the number of consultations by male IPV victims increased 2.5‐fold between 2019 and 2020 (from 2902 to 7354 cases). 29 Government research in 2020 revealed that male victims were more often victims of psychological abuse and/or neglect than physical violence, and that they tended not to report their victimization and not to consult anyone for support. 30 , 31 , 32

In Japanese society, psychological abuse was not widely recognized as a form of abuse until 2023, despite the clear evidence of even severe psychological abuse. In 2023, a partial revision (seventh version) of the Domestic Violence Prevention Act was conducted and the revised act included psychological abuse. 33 , 34 Victims of psychological abuse were conferred some degree of new protections under the Act. According to the preamble of the Act, the incidence of female victims of IPV is greater than that of male victims. 34 The previous studies of IPV were also more focused on female victims than male victims. 35 , 36 , 37 , 38 On the other hand, the number of male victims seeking consultation is increasing every year. According to the Criminal Situation 2022 report by the Japanese police department, 73.1% of respondents who were IPV victims were women and 26.9% were men. 39 The ratio of men among IPV victims has been growing year by year, from 21.7% in 2019 to 23.6% in 2020, 25.2% in 2021, and the aforementioned 26.9% in 2022.

However, most of the relevant studies have been conducted in the West, with few studies carried out in other regions, including Asian or Arab countries. Moreover, although our previous study indicated that male IPV victims in Japan are more frequently subject to psychological abuse than physical violence, 40 little is known about the help‐seeking behaviors of male victims who experience nonphysical forms of abuse.

Purpose of the study

The primary objective of this study was to identify and analyze factors influencing the help‐seeking behaviors of male IPV victims in Japan by means of a web‐based survey.

The research questions for this study were as follows:

-

1.

What are the specific attributes of male victims who report the victimizations?

-

2.

What kinds of victimization do male victims who report the victimizations receive?

-

3.

Does the victimization across multiple domains—that is, single or multiple domains—affect help‐seeking behaviors of victims?

-

4.

Where do male victims seek help?

METHODS

Study design

We engaged Cross Marketing Inc. 41 to execute an investigation into domestic cohabitation dynamics, specifically focusing on individuals within spousal or intimate partnerships. The survey, conducted on February 25–26, 2021, was designed to elucidate some of the complexities of domestic life.

Study participants

The study involved 1466 male individuals aged 18 years or older who had encountered heterosexual partner abuse or violence within the surveyed timeframe of the past year. Eligible participants were required to be proficient in both spoken and written Japanese. In a study in a Western cohort by Machado et al., 17 the act of seeking help was defined as consulting someone. During data analysis, participants were divided into two groups: Group 1 comprised victims who sought help by confiding in someone they knew, someone at an administrative agency, or the police, while Group 2 consisted of victims who did not seek help.

Survey contents

Sociodemographic characteristics

This survey consisted of items regarding the attributes (age, academic attainment, employment, and marital status) and past experiences (experience of school bullying, past/present psychiatric history, foregoing divorce to avoid ACEs in their offspring, experience of taking psychiatric medicine, childhood exposure to domestic violence and depression trait) of respondents.

Abuse/violence contents

The types of abuse/violent victimization were explored, employing the Domestic Violence Screening Inventory (DVSI) and a 20‐item questionnaire focusing on the types of IPV exposure. The question items are listed in Table 5.

Table 5.

Correlation analyses of the specifics of abuse/violent victimization.

| Specifics of abuse/violent victimization | n | Cramér (V) | P‐value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Domestic Violence Screening Inventory | |||

| My partner used force (hitting, restraint or use of weapon) to make me have oral or anal sex | 4 | 0.30 | <.001 |

| My partner used force (hitting, restraint or use of weapon) to make me have sex | 4 | 0.27 | <.001 |

| My partner used threats to make me have sex | 5 | 0.27 | <.001 |

| My partner used threats to make me have oral or anal sex | 3 | 0.24 | <.001 |

| I went to a doctor because of a fight with my partner | 4 | 0.21 | <.001 |

| My partner choked me | 4 | 0.21 | <.001 |

| My partner punched or hit me with something painful (physical violence) | 6 | 0.21 | <.001 |

| I passed out from being hit on the head by my partner in a fight | 3 | 0.19 | <.001 |

| I had a broken bone from a fight with my partner | 2 | 0.18 | <.001 |

| My partner beat me up | 4 | 0.17 | <.001 |

| I needed to see a doctor because of a fight with my partner, but I did not | 4 | 0.16 | <.001 |

| My partner showed me a knife or a weapon | 4 | 0.13 | <.001 |

| My partner did or said something to spite me (psychological abuse) | 19 | 0.11 | <.05 |

| My partner insulted or swore at me | 22 | 0.09 | .06 |

| My partner bawled at me | 21 | 0.07 | .284 |

| 20‐item questionnaire on the type(s) of IPV exposure | |||

| My partner threatened or suggested that she would commit suicide | 6 | 0.19 | <.001 |

| My partner had no will to work or repeatedly quit his/her job (economic abuse) | 8 | 0.18 | <.001 |

| My partner lived with her affair partner | 1 | 0.15 | <.001 |

| My partner separated from me without my agreement | 2 | 0.15 | <.001 |

| My partner did not allow me to go to the clinic when I was ill or hurt | 1 | 0.15 | <.001 |

| My partner refused to have sexual intercourse (sexual abuse) | 10 | 0.13 | <.01 |

| My partner monitored or eavesdropped on me | 6 | 0.11 | <.01 |

| My partner prevented me from seeing my family or friends | 6 | 0.11 | <.01 |

| My partner came to my workplace and threatened and bothered my colleagues | 1 | 0.10 | <.01 |

| My partner did not take care of me when I was ill or hurt | 4 | 0.11 | <.01 |

| My partner never gave me our living expenses | 4 | 0.09 | <.05 |

| My partner ignored and did not talk to me for many days | 21 | 0.06 | .54 |

| My partner wasted our daily living expenses and bought needless things | 8 | 0.07 | .39 |

| My partner gave me little money or seldom gave me money for our living expenses | 3 | 0.08 | .12 |

| My partner monitored my physical mail and emails on my mobile phone | 4 | 0.04 | .89 |

| My partner would not let me in or out of the house | 2 | 0.06 | .41 |

| My partner ran away from home many times and did not stay home all year round | 0 | 0.02 | .99 |

| My partner had an affair | 3 | 0.09 | .07 |

| My partner neither did housework nor raised a family | 4 | 0.09 | .09 |

| My partner used force to have an abortiona | – | – | – |

Note: n = 43 (Group 1) (there were duplicate responses).

Abbreviation: IPV, intimate partner violence. Bold entries showed statistical significance.

This question was a dummy question.

Single and multiple forms of victimizations

Several lines of research have indicated that male victims are more likely to experience multiple forms of abuse/violence than female victims, who are more likely to experience a single form of abuse/violence. 31 , 42 , 43 , 44 We therefore examined the various forms of abuse/violence suffered by male victims from their partners.

Survey items on help‐seeking behavior

Respondents were asked several questions regarding their help‐seeking behavior, including “Have you communicated with anyone about the abuse/violence you have experienced?” and “If you answered ‘yes’ to this question, to whom did you talk?”

Measurements

The instruments employed included the DVSI (the question items are listed in Table 5), 45 the Patient Health Questionnaire‐9 (PHQ‐9), 46 , 47 and the 20‐item questionnaire on IPV exposure (the question items are listed in Table 5). 40 The DVSI scale is designed to assess the intensity and frequency of physical and verbal abuse within intimate partnerships in Japan, and was standardized by Ishii et al. 48 It has 15 items and the respondents are instructed to respond to each item based on an eight‐point Likert scale ranging from 0 = “never” to 6 = “I have received abuse/violence from a partner more than 20 times in the past year,” and to mark 7 for “I have not received abuse/violence from a partner recently, but received it more than one year ago.” The PHQ‐9 is self‐administered tool for screening. It examines the severity of depression during the prior 2 weeks and is described elsewhere. It consists of 10 items, and respondents are directed to respond to each item, based on a four‐point Likert scale ranging from 0 = “not at all” to 3 = “extremely,” resulting in a total score ranging from 0 to 27. Cut‐off points of ≥5 and ≥10 were taken to indicate depressive traits and diagnosis of depression, respectively. The 20‐item questionnaire on IPV was created by Morishita et al. 40 and consists of questions regarding six categories of violence—namely, physical violence, psychological abuse, economic abuse, social abuse, sexual abuse, and neglect. The score is calculated in a similar way as for the DVSI, that is, using a Likert scale with scores of 0, 0.5, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, and 6.

Statistical analyses

Data are presented using P‐values and percentages. Cramér's coefficient of association was used to gauge the relationships among qualitative variables. We performed a chi‐square test to analyzed differences in attributes and type of abuse/violence between Groups 1 and 2 and logistic regression analyses to extract specific items from each variable. Significance was attributed to P‐values <.05, and denoted with asterisks according to the three levels of significance: <.05 (*), <.01 (**), and <.001 (***). Statistical computations were executed through IBM SPSS ver. 26 for Windows.

Logistic regression analyses

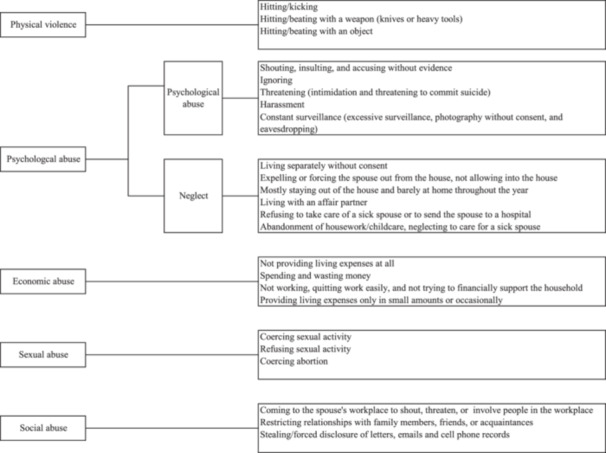

Three logistic regression analyses were conducted in this study. Initial screening involved the selection of independent variables based on respondent numbers (cutoff ≥4). Subsequent screening prioritized independent variables according to Cramér's coefficient of correlation. For victimization by type of abuse/violence, variables included physical violence, economic abuse, psychological abuse, sexual abuse and social abuse. A detailed description of each type of IPV is presented in Figure 1. 49 For past experiences, the independent variables were foregoing divorce to avoid ACEs in their offspring, experience of school bullying, history of psychiatric medications, and current depressive symptoms.

Figure 1.

Domestic violence forms in Japanese male victims. Created based on Morishita et al. (2022). Source: Perspectives on Domestic Violence in Japan: a Review Study of Court Precedent for Marital Lawsuits. Japanese Bulletin of Social Psychiatry 2022; 31: 9–29.

Selection criteria ensured the removal of unrelated or duplicate variables, resulting in a more accurate model. 50 Dependent variables maintained a binary distinction between those who sought consultation and those who did not, employing the forced entry method.

Ethical considerations

Participants were apprised that the questionnaire guaranteed anonymity and confidentiality, and that their responses would be meticulously controlled and securely stored. A coded system precluded individual identification, and the data were solely utilized for statistical purposes. Informed consent was obtained from participants, affirming their understanding of the survey's purpose and their voluntary participation. Since this survey might evoke psychological responses in the participant, we suggested that they stop answering when stressed. The ethical framework was approved by the Jichi Medical University Clinical Research Ethics Committee (approval no. 19‐196). Points were remunerated to participants by Cross Marketing as an honorarium payment.

RESULTS

Attributes (Table 1a)

Table 1a.

Sociodemographic characteristics of the study participants.

| Variables | Group 1, n (%) | Group 2, n (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Attributes | ||

| Age | ||

| ≤18 | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| 18–19 | 1 (2.3) | 0 (0.0) |

| 20–24 | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| 25–29 | 0 (0.0) | 3 (0.2) |

| 30–34 | 0 (0.0) | 12 (0.8) |

| 35–39 | 3 (7.0) | 33 (2.3) |

| 40–44 | 0 (0.0) | 78 (5.5) |

| 45–49 | 8 (18.6) | 167 (11.7) |

| 50–54 | 10 (23.3) | 208 (14.6) |

| 55–59 | 3 (7.0) | 244 (17.1) |

| 60–64 | 9 (21.0) | 212 (14.9) |

| 65–69 | 3 (7.0) | 204 (14.3) |

| 70–74 | 5 (11.6) | 178 (12.5) |

| 75–79 | 1 (2.3) | 58 (4.1) |

| 80–85 | 0 (0.0) | 26 (1.8) |

| ≥86 | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| total (%) | 43 (100) | 1423 (100) |

| Academic attainment | ||

| Junior high school | 1 (2.3) | 19 (1.3) |

| High school | 5 (11.6) | 335 (23.5) |

| College or technical school | 3 (7.0) | 139 (9.8) |

| Undergraduate | 30 (69.8) | 817 (57.4) |

| Graduate | 4 (9.3) | 113 (7.9) |

| Total (%) | 43 (100) | 1423 (100) |

| Employment | ||

| Regular employment | 13 (30.2) | 547 (38.4) |

| Contract employment | 5 (11.6) | 95 (6.7) |

| Public servant | 2 (4.7) | 92 (6.5) |

| Board of company | 7 (16.3) | 68 (4.8) |

| Teacher | 0 (0.0) | 27 (1.9) |

| Medical employment | 2 (4.7) | 29 (2.0) |

| Legal profession | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.1) |

| Agriculture, forestry, fisheries | 0 (0.0) | 6 (0.4) |

| Self‐employment | 4 (9.3) | 155 (10.9) |

| Part‐time employment | 1 (2.3) | 70 (4.9) |

| Student | 1 (2.3) | 0 (0.0) |

| Househusband | 0 (0.0) | 10 (0.7) |

| Unemployed | 8 (18.6) | 323 (22.7) |

| Total (%) | 43 (100) | 1423 (100) |

| Marital status | ||

| Married | 39 (90.7) | 1406 (98.8) |

| Lived together, not married | 3 (7.0) | 8 (0.6) |

| Died | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Divorced | 1 (2.3) | 9 (0.6) |

| Total (%) | 43 (100) | 1423 (100) |

Note: Group 1 (n = 43): victims who sought help. Group 2 (n = 1423): victims who did not seek help. The values do not add to 100% because of rounding. Bold entries are mode value s.

Age

The predominant age bracket was 50–54 years of age (23.3%) in Group 1 and 55–59 years of age (17.1%) in Group 2 (Table 1a). There was no significant difference in the proportion of the elderly population between Group 1 (50–85 years of age, 72.1%) and Group 2 (50–85 years of age, 79.4%) (P = .244) (Table 1b).

Table 1b.

Chi‐square test of the age population of Group 1 and Group 2.

| Age (years) | Group 1, n (%) | Group 2, n (%) | Total, n = 1466 | χ 2 value | P‐value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low (19–49) | 12 (27.9) | 293 (20.6) | 305 (20.8) | ||

| 1.356 | .244 | ||||

| High (50–85) | 31 (72.1) | 1130 (79.4) | 1161 (79.2) |

Note: Group 1 (n = 43): victims who sought help. Group 2 (n = 1423): victims who did not seek help.

Academic attainment

Undergraduate education was the predominant academic achievement in both Group 1 and Group 2 (Table 1a). There was no significant difference in the proportion of the academic attainments between both groups (chi‐square test, data not shown).

Employment

The most prevalent employment status in both Group 1 and Group 2 was regular employment, followed by unemployment (Table 1a). There was no significant difference in the proportion of the employment status between both groups (chi‐square test, data not shown).

Marital status

The prevailing marital status in both Group 1 and Group 2 was married (Table 1a). There was no significant difference in the proportion of the marital status between both groups (chi‐square test, data not shown).

Correlation analyses

Past experiences (Table 2)

Table 2.

Correlation analyses of past experiences.

| Past experience | Group 1, n (%) | Group 2, n (%) | Cramér (V) | P‐value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Experience of school bullying | 22 (51.2) | 275 (19.3) | 0.134 | <.001 |

| Past/present psychiatric history | 16 (37.2) | 173 (12.2) | 0.126 | <.001 |

| Foregoing divorce to avoid ACEs in their offspring | 21 (48.8) | 406 (28.5) | 0.108 | <.001 |

| Experience of taking psychiatric medicine (e.g., sleeping pills, tranquillizers) | 18 (41.9) | 259 (18.2) | 0.102 | <.001 |

| Childhood exposure to domestic violence | 11 (25.6) | 130 (9.1) | 0.094 | <.01 |

| Depression trait a | 21 (48.8) | 427 (30.0) | 0.069 | <.01 |

Note: Group1 (n = 43): victims who sought help. Group 2 (n = 1423): victims who did not seek help.

Abbreviation: ACEs, adverse childhood experiences. Bold entries showed statistical significance.

Total scores range from 0 to 27. A cutoff point of ≥5 was set for mild depression trait and ≥10 for moderate to severe depression trait. In this study, ≥5 was set for having depressive symptoms and ≤4 for not having depressive symptoms.

All items exhibited positive correlations between Group 1 and Group 2. The experience of school bullying demonstrated the highest correlation coefficient (V = 0.134, P < .001), whereas depressive trait exhibited the lowest correlation coefficient (V = 0.069, P < .01).

Types of abuse/violent victimization (Table 3)

Table 3.

Correlation analyses of types of abuse/violent victimization.

| Type of abuse/violence victimization | Group 1, n (%) | Group 2, n (%) | Cramér (V) | P‐value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Physical violence | 9 (20.9) | 67 (4.7) | 0.123 | <.001 |

| Social abuse | 8 (18.6) | 133 (9.3) | 0.053 | .048 |

| Economic abuse | 13 (30.2) | 278 (19.5) | 0.045 | .083 |

| Sexual abuse | 14 (32.6) | 317 (22.3) | 0.041 | .112 |

| Neglect | 8 (18.6) | 165 (11.6) | 0.037 | .160 |

| Psychological abuse | 29 (67.4) | 842 (59.2) | 0.028 | .277 |

Note: Group 1 (n = 43): victims who sought help (there were duplicate responses). Group 2 (n = 1423): victims who did not seek help. Bonferroni correction was performed for multiple comparisons. Bold entries showed statistical significance.

Victimization involving physical violence (V = 0.123, P < .001) displayed positive correlations between Group 1 and Group 2.

Specifics of abuse/violent victimization (Table 5)

Specifics of abuse/violent victimization showed significant correlation coefficients with four or more participants answering affirmatively: “My partner punched or hit me with something painful” (physical violence), “My partner had no will to work or repeatedly quit his/her job” (economic abuse), “My partner refused to have sexual intercourse” (sexual abuse), and “My partner did or said something to spite me” (psychological abuse).

Logistic regression analyses

Past experiences (Table 6)

Table 6.

Logistic regression analysis of past experiences.

| Logistic regression analysis | P‐value | Adjusted odds ratio | 95% CI for EXP(B) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Past experience | B | SE | Lower | Upper | ||

| Foregoing divorce to avoid ACEs in their offspring | 1.145 | 0.395 | .003 ** | 3.143 | 1.448 | 6.823 |

| Experience of school bullying | 0.974 | 0.376 | .009 ** | 2.648 | 1.267 | 5.535 |

| Experience of taking psychiatric medicine (e.g., sleeping pills or tranquillizers) | 0.778 | 0.390 | .046 * | 2.177 | 1.013 | 4.680 |

| Depression trait | 0.010 | 0.395 | .980 | 1.010 | 0.466 | 2.189 |

Note: The dependent variable was victims who sought help (Group 1) or victims who did not seek help (Group 2). Group 2 coded 0. Group 1 coded 1. Negelkerke R 2 0.093. Group 1: n = 43, Group 2: n = 1423. Bold entries showed statistical significance.

Abbreviations: ACEs, adverse childhood experiences; CI, confidence interval; EXP(B), exponentiation of the B coefficient; SE, standard error.

P < 0.05.

P < 0.01.

Analysis of past experiences revealed that “foregoing divorce to avoid ACEs in their offspring” (odds ratio [OR] = 3.14, confidence interval [CI] = 1.45–6.82, P = .003), “experience of school bullying” (OR = 2.65, CI = 1.27–5.53, P = .009), and “experience of taking psychiatric medicine” (OR = 2.18, CI = 1.01–4.68, P = .046) were significantly correlated with the availability of consultation.

Types of abuse/violent victimization (Table 7)

Table 7.

Logistic regression analysis of types of abuse/violent victimization.

| Logistic regression analysis | P‐value | Adjusted odds ratio | 95% CI for EXP(B) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Type of abuse/violent victimization | B | SE | Lower | Upper | ||

| Physical violence | 1.507 | 0.429 | .000 *** | 4.512 | 1.948 | 10.452 |

| Psychological abuse | 0.027 | 0.363 | .942 | 1.027 | 0.504 | 2.093 |

| Economic abuse | 0.248 | 0.395 | .529 | 1.282 | 0.591 | 2.778 |

| Social abuse | 0.319 | 0.466 | .494 | 1.375 | 0.551 | 3.431 |

Note: The dependent variable was victims who sought help (Group 1) or victims who did not seek help (Group 2). Group 2 coded 0. Group 1 coded 1. Negelkerke R 2 0.043. Group 1: n = 43, Group 2: n = 1423. Bold entries showed statistical significance.

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; EXP (B), exponentiation of the B coefficient; SE, standard error.

P < 0.001.

Only physical violence exhibited significance in this analysis (OR = 4.51, CI = 1.95–10.50, P < .001).

Specifics of abuse/violent victimization (Table 8)

Table 8.

Logistic regression analysis of the specifics of abuse/violent victimization.

| Logistic regression analysis | P‐value | Adjusted odds ratio | 95% CI for EXP(B) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Specifics of abuse/violent victimization | B | SE | Lower | Upper | ||

| Physical violence | ||||||

| My partner punched or hit me with something painful | 1.604 | 0.527 | .002 ** | 4.973 | 1.772 | 13.958 |

| Economic abuse | ||||||

| My partner had no will to work or repeatedly quit his/her job | 1.035 | 0.447 | .021 * | 2.815 | 1.173 | 6.758 |

| Psychological abuse | ||||||

| My partner did or said something to spite me | 0.425 | 0.343 | .215 | 1.530 | 0.782 | 2.994 |

| Sexual abuse | ||||||

| My partner refused to have sexual intercourse | −0.226 | 0.395 | .567 | 0.798 | 0.368 | 1.730 |

Note: The dependent variable was victims who sought help (Group 1) or victims who did not seek help (Group 2). Group 2 coded 0. Group 1 coded 1. Negelkerke R 2 0.056. Group 1: n = 43, Group 2: n = 1423. Bold and italic entries showed statistical significance.

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; EXP (B), exponentiation of the B coefficient; SE, standard error.

P < 0.05.

P < 0.01.

“My partner punched or hit me with something that could hurt” (physical violence: OR = 4.97, CI = 1.77–13.95, P = .002) and “My partner had no will to work or repeatedly quit his/her job” (economic abuse: OR = 2.81, CI = 1.17–6.76, P = 0.021) were significantly associated with the availability of consultation.

Victimizations across single or multiple domains within the past 1 year (Table 4, 9a, 9b)

Table 4.

Chi‐square test of multiple domains of victimization.

| n | Chi‐square test | P‐value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Multiple domains | Group 1 | 22 | 5.092 | .024 * |

| Group 2 | 491 |

Note: 1466 participants (43 in Group 1 and 1423 in Group 2). Bold entries showed statistical significance.

P < 0.05.

Table 9a.

A single domain of victimization and multiple domains of victimizations.

| Group 1 | Total, n (%) | n | |

|---|---|---|---|

| A single domain of victimization | 11 (25.6) | ||

| Psychological abuse | 9 | ||

| Sexual abuse | 1 | ||

| Economic abuse | 1 | ||

| Multiple domains of victimizations | 22 (51.2) | ||

| Two | 9 | ||

| Psychological abuse and economic abuse | 3 | ||

| Psychological abuse and sexual abuse | 3 | ||

| Psychological abuse and neglect | 1 | ||

| Psychological abuse and social abuse | 1 | ||

| Neglect and sexual abuse | 1 | ||

| Three | 7 | ||

| Physical violence, psychological abuse, and sexual abuse | 3 | ||

| Physical violence, psychological abuse, and social abuse | 1 | ||

| Psychological abuse, economic abuse, and sexual abuse | 1 | ||

| Psychological abuse, neglect, and economic abuse | 1 | ||

| Neglect, economic abuse, and social abuse | 1 | ||

| Four | 2 | ||

| Physical violence, psychological abuse, sexual abuse, and economic abuse | 1 | ||

| Psychological abuse, economic abuse, sexual abuse, and social abuse | 1 | ||

| Five | 2 | ||

| Psychological abuse, neglect, economic abuse, sexual abuse, and social abuse | 1 | ||

| Physical violence, psychological abuse, neglect, economic abuse, and social abuse | 1 | ||

| Six | 2 | ||

| Physical violence, psychological abuse, neglect, economic abuse, sexual abuse, and social abuse | 2 | ||

| None | 10 (23.3) | ||

Note: Group 1 (n = 43): victims who sought help.

Table 9b.

A single domain of victimization and multiple domains of victimizations.

| Group 2 | Total, n (%) | n | |

|---|---|---|---|

| A single domain of victimization | 452 (31.8) | ||

| Psychological abuse | 371 | ||

| Sexual abuse | 46 | ||

| Economic abuse | 18 | ||

| Social abuse | 8 | ||

| Neglect | 7 | ||

| Physical violence | 2 | ||

| Multiple domains of victimizations | 491 (34.5) | ||

| Two | 280 | ||

| Psychological abuse and sexual abuse | 112 | ||

| Psychological abuse and economic abuse | 91 | ||

| Psychological abuse and neglect | 24 | ||

| Psychological abuse and social abuse | 24 | ||

| Physical violence and psychological abuse | 11 | ||

| Neglect and sexual abuse | 4 | ||

| Physical violence and neglect | 1 | ||

| Neglect and economic abuse | 1 | ||

| Three | 115 | ||

| Psychological abuse, economic abuse, and sexual abuse | 27 | ||

| Psychological abuse, neglect, and economic abuse | 25 | ||

| Psychological abuse, neglect, and sexual abuse | 17 | ||

| Psychological abuse, economic abuse, and social abuse | 12 | ||

| Psychological abuse, sexual abuse, and social abuse | 11 | ||

| Psychological abuse, neglect, and social abuse | 9 | ||

| Physical violence, psychological abuse, and sexual abuse | 8 | ||

| Physical violence, psychological abuse, and economic abuse | 5 | ||

| Neglect, sexual abuse, and social abuse | 1 | ||

| Four | 63 | ||

| Psychological abuse, neglect, sexual abuse, and economic abuse | 21 | ||

| Psychological abuse, economic abuse sexual abuse, and social abuse | 15 | ||

| Psychological abuse, neglect, economic abuse, and social abuse | 13 | ||

| Physical violence, psychological abuse, economic abuse, and sexual abuse | 5 | ||

| Physical violence, psychological abuse, economic abuse, and social abuse | 3 | ||

| Psychological abuse, neglect, sexual abuse, and social abuse | 3 | ||

| Physical violence, psychological abuse, neglect abuse, and sexual abuse | 2 | ||

| Physical violence, psychological abuse, neglect abuse, and social abuse | 1 | ||

| Five | 22 | ||

| Psychological abuse, neglect, economic abuse, sexual abuse, and social abuse | 17 | ||

| Physical violence, psychological abuse, neglect, economic abuse, and sexual abuse | 2 | ||

| Physical violence, psychological abuse, neglect, economic abuse, and social abuse | 2 | ||

| Physical violence, psychological abuse, economic abuse, sexual abuse, and social abuse | 1 | ||

| Six | 11 | ||

| Physical violence, psychological abuse, neglect, economic abuse, sexual abuse, and social abuse | 11 | ||

| None | 480 (33.7) | ||

Note: Group 2 (n = 1423): victims who did not seek help.

In Group 1, 25.6% of victims experienced a single domain of victimization within the past year, while 51.2% experienced multiple domains of victimizations. In Group 2, 31.8% experienced a single domain of victimization and 34.5% experienced multiple domains of victimizations. The chi‐square test of multiple domains was significantly higher in Group 1 than in Group 2 (χ 2 = 5.092, P = .024).

Help‐seeking behavior: seeking formal/informal assistance (Table 10)

Table 10.

Help‐seeking behavior: seeking formal/informal assistance.

| Group 1 | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Informal help | 28 (65.1) |

| Formal help | 8 (18.6) |

| Both informal and formal help | 7 (16.3) |

| Total | 43 (100.0) |

| Informal helpa | |

| Family members | 27 (62.8) |

| Friends/colleagues | 16 (37.2) |

| Social networking services | 1 (2.3) |

| Formal help | |

| Healthcare workers | 12 (27.9) |

| Administrative institutions | 7 (16.3) |

| Police agencies | 3 (7.0) |

Note: Group1: n = 43.

There were duplicate responses.

Of 43 victims in Group 1, 65.1% sought informal help, 18.6% sought formal help, and 16.3% sought both informal and formal help. Informally, family members were the most frequently chosen advocates (62.8%), followed by friends/colleagues (37.2%). Formally, healthcare workers (27.9%), administrative institutions (16.3%), and police agencies (7.0%) were frequently sought.

DISCUSSION

We analyzed web‐based questionnaire responses from male IPV victims in Japan to investigate factors associated with help‐seeking behavior. Group 1 comprised 43 male individuals exhibiting help‐seeking behavior, while Group 2 consisted of 1423 male individuals who did not seek help. Comparisons between Groups 1 and 2 were conducted to elucidate existing differences.

What are the specific attributes of male victims who report the victimizations?

The results showed that the most frequent demographic characteristics in both groups were age 50–59 years, an undergraduate degree, full‐time employment, and married marital status. In regard to the age of the victims, middle‐age victims were common than younger victims, contradicting the hypothesis of previous studies 1 , 12 that younger men are more vulnerable. The unemployment rates of Groups 1 and 2 were 19% and 23%, respectively, substantially surpassing the general unemployment rate in Japan for 2021 (2.8%), 51 indicating that unemployment was associated with IPV victimization, which was consistent with previous studies. 12 , 52

Logistic regression analyses were performed to elucidate the factors influencing the help‐seeking behaviors of IPV victims. Previous studies have shown that past present/psychiatric history, 40 experiences of taking psychiatric medicine (e.g., sleeping pills, tranquillizers), 40 depressive trait, 40 experience of abuse in childhood, 13 experience of school bullying, 40 alcohol misuse, 13 , 27 jealousy, 13 and foregoing divorce to avoid ACEs in their offspring 13 were all risk factors for male IPV victimization in adulthood. 13 In this study, victims who sought help were more likely to have foregone divorce to avoid ACEs in their offspring, to be taking psychiatric medicine, and to have experienced school bullying compared to victims who did not seek help, a finding consistent with the previous study. 13 , 40 The victims foregoing divorce to avoid ACEs in their offspring might have been keen to preserve the family configuration due to the conventional disapproval of divorce in Japan, and this could have been the motivation for their help‐seeking behaviors. Victims who had endured school bullying might have previously experienced help‐seeking behavior during their formative years and thereby gained knowledge regarding abuse victimization; this could have motivated them to seek comparable help in the context of marital life. Also, participants with past or present psychiatric illness would have had better access to consultation regarding their family problems.

What kinds of victimization do male victims who report the victimizations receive?

Examining the types of abuse/violent victimization, it became evident that victims seeking help encountered higher rates of physical violent victimization compared to their counterparts who did not seek help (OR = 4.51, CI = 1.95–10.45, P < .001). This was consistent with previous studies which reported that male IPV victims were prone to be victimized by physical violence. 53 , 54 Notably, victims seeking help were more frequently subjected to being “hit by their partner with something painful” (physical violence) (Figure 1). The previous Western studies underscore the use of potentially injurious objects by female perpetrators. 36 Since the effects of physical violence are sometimes clearly visible, 55 they might help the victims to recognize that they have been abused and proactively seek help. In contrast, because male victims without help‐seeking behaviors did not have enough insight of nonphysical abuse, they could not seek help even if they suffer various kinds of abuse.

The results of the analysis of specific abuse/violent victimization content revealed that victims seeking help experienced heightened economic abuse victimization as expressed in the item “My partner had no will to work or repeatedly quit his/her job” (Table 8). Existing literature have signified a higher prevalence of economic abuse against men. 40 According to a Japanese national survey, 56 the number of double‐income households has increased and that of households with a full‐time homemaker has decreased every year for four decades (35.5% in 1980 and 70.0% in 2022), 56 suggesting that Japanese men increasingly expect women to contribute financially. This expectation might decrease the victims’ tolerance of this form of abuse and provoke the help‐seeking behaviors.

Does victimization across multiple domains—that is, single or multiple domains—affect the help‐seeking behaviors of victims?

A categorical examination of victimizations across single versus multiple domains revealed that victims displaying help‐seeking behavior were more likely to have experienced multiple domains of victimizations than those who did not seek help (χ2 = 5.09, P = .024). This result is consistent with previous studies. 31 A combination of psychological abuse and other abuse was particularly prevalent. According to Uehara, 57 victims who sought help demonstrated an increased awareness of violence/abuse, which likely contributed to their inclination to seek assistance. Conversely, victims who had experienced a single domain of victimization often endured solely psychological abuse, and might have been dissuaded from seeking help due to a lower level of awareness regarding this more subtle form of victimization. Comprehensive support measures, such as knowledge acquisition and awareness campaigns, are imperative to encourage help‐seeking behavior among male victims.

Where do male victims seek help?

Another important consideration when analyzing help‐seeking behavior is the matter of the specific individuals/agencies to whom victims disclose their victimization (Table 10). Our results indicate a preference among male victims for confiding in close associates rather than public agencies, which is consistent with the previous studies. 17 , 21 , 23 , 58 , 59 , 60 This may be simply attributable to victims preferring to confide their private and confidential problems to people who know them rather than unfamiliar consultants. Regarding formal support, more of our participants sought help from healthcare professionals than from administrative agencies or the police. This result showed that victims who had a psychiatric history sought help more often than those who did not have a psychiatric history. Their higher rate of consultation with healthcare professionals may thus have been due to their more‐ready access to healthcare professionals. The lack of easy male access to healthcare professionals would be exacerbated by the dearth of counseling services for male IPV victims: Japanese public institutions have only a few such services, versus 313 support centers (included facilities without accommodation) for female victims in Japan. It is also notable that there are 50 or more undisclosed shelters for women in Japan, including at least one such shelter in each Japanese prefecture, while for men there are fewer than 10 such facilities. 40 Given the anticipated rise in male IPV victims, public institutions should expand support services tailored to male victims, akin to those available for female victims.

Overall, our analysis revealed that the main factors contributing to help‐seeking behaviors by male victims were negative past experiences such as ACEs and school bullying, and past history of psychiatric illness and psychiatric medications.

In this study, 1466 male respondents shared their IPV experiences. Of these, only 2.9% sought help, while 97.1% did not seek help. This stark disparity raises concerns about the underreporting of male IPV victimization. To encourage help‐seeking in male victims who lack the above‐described factors to motivate them, it is recommended that education be provided on forms of victimization other than physical abuse, so that male victims will understand the importance of talking to family, friends, coworkers, or professional advocates. In tandem with this measure, there is a need to provide more public institutions that are accessible to male victims. These and other policy recommendations will be required to address the needs of this silent majority of male victims.

LIMITATIONS

The questionnaire responses in this study did not provide information on the severity of violence/abuse. Since this study was based on a web survey, there was unavoidable selection bias, and participant willingness to engage with the questionnaire may have led to another bias. However, for the study of private and confidential problems, web‐based surveys are considered to be less invasive and better‐tolerated by participants. 61 In addition, the observed correlation between IPV victimization and unemployment warrants caution, as increased unemployment rates might have influenced questionnaire participation, potentially affecting the results. Finally, detailed information about the motivations of help‐seeking victims was not collected. Future research endeavors should seek to rectify these limitations to enhance our comprehension of factors influencing the help‐seeking behavior of male victims.

CONCLUSION

Male IPV victims in Japan demonstrate a propensity to seek help following physical violence, highlighting the need for targeted support for victims experiencing forms of victimization beyond physical violence. The underreporting of Japanese male IPV victimization should be underscored. Expanding counseling and support services, along with the establishment of dedicated resources for male victims, is essential to fostering a supportive environment conducive to breaking the silence surrounding male IPV victimization.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

J.M. wrote the first draft, and J.M. and S.S. contributed to data interpretation. J.M., M.Y., and S.S. provided the outlines and conception. J.M. and S.S. wrote the paper, and S.S. supervised and finalized the manuscript and approved the final article.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

Dr. Shiro Suda is the Vice Editor‐in‐Chief of Psychiatry and Clinical Neurosciences Reports and a co‐author of this article. They were excluded from editorial decision‐making related to the acceptance and publication of this article.

ETHICS APPROVAL STATEMENT

This study was approved by the Jichi Medical University Clinical Research Ethics Committee (approval no. 19‐196). Informed consent was obtained from all participants.

PATIENT CONSENT STATEMENT

N/A.

CLINICAL TRIAL REGISTRATION

N/A.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank all participants of the study for their invaluable contributions. We also thank Makiko Mieno, Vice Director of the Information Center of Jichi Medical University, for her technical assistance and helpful comments on the manuscript. This study was supported by a training grant for Jichi Medical University graduate school students.

Morishita J, Yasuda M, Suda S. Help‐seeking behavior of male victims of intimate partner violence in Japan. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci Rep. 2024;3:e70013. 10.1002/pcn5.70013

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, S.S., upon reasonable request.

REFERENCES

- 1. World Health Organization . Violence against women. GHO. 2022. Available from: https://www.who.int/gho/women_and_health/violence/en [Google Scholar]

- 2. Ruiz‐Pérez I, Rodríguez‐Barranco M, Cervilla JA, Ricci‐Cabello I. Intimate partner violence and mental disorders: co‐occurrence and gender differences in a large cross‐sectional population based study in Spain. J Affect Disord. 2018;229:69–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Cornally N, McCarthy G. Help‐seeking behaviour: a concept analysis. Int J Nurs Pract. 2011;17(3):280–288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Drijber BC, Reijnders UJL, Ceelen M. Male victims of domestic violence. J Fam Violence. 2012;28(2):173–178. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Nybergh L, Taft C, Krantz G. Psychometric properties of the WHO Violence Against Women instrument in a male population‐based sample in Sweden. BMJ Open. 2012;2(6):e002055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. The ManKind Initiative . Helping men escape domestic abuse. 2023. Available from: https://mankind.org.uk/

- 7. Safe communities Portugal . Domestic violence | safe communities Portugal. 2022. Available from: https://www.safecommunitiesportugal.com/find-information/domestic-violence/

- 8. Dim EE, Elabor‐Idemudia P. Prevalence and predictors of psychological violence against male victims in intimate relationships in Canada. J Aggress Maltreat Trauma. 2018;27(8):846–866. [Google Scholar]

- 9. The national coalition against domestic violence . Voice of victims home for advocates. Available from: https://ncadv.org/

- 10. Carmo R, Grams A, Magalhães T. Men as victims of intimate partner violence. J Forensic Leg Med. 2011;18(8):355–359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Devries KM, Mak JY, Bacchus LJ, Child JC, Falder G, Petzold M, et al. Intimate partner violence and incident depressive symptoms and suicide attempts: a systematic review of longitudinal studies. PLoS Med. 2013;10(5):e1001439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Cook PW. Abused men: the hidden side of domestic violence. 2nd ed. Praeger; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Kolbe V, Büttner A. Domestic violence against men‐prevalence and risk factors. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2020;117(31–32):534–541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Taylor JC, Bates EA, Colosi A, Creer AJ. Barriers to men's help seeking for intimate partner violence. J Interpers Violence. 2022;37(19–20):NP18417–NP18444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Biddle L, Gunnell D, Sharp D, Donovan JL. Factors influencing help seeking in mentally distressed young adults: a cross‐sectional survey. Br J Gen Pract. 2004;54(501):248–253. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Lysova A, Hanson K, Dixon L, Douglas EM, Hines DA, Celi EM. Internal and external barriers to help seeking: voices of men who experienced abuse in the intimate relationships. Int J Offender Ther Comp Criminol. 2022;66(5):538–559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Machado A, Santos A, Graham‐Kevan N, Matos M. Exploring help seeking experiences of male victims of female perpetrators of IPV. J Fam Violence. 2017;32:513–523. [Google Scholar]

- 18. Walker A, Lyall K, Silva D, Craigie G, Mayshak R, Costa B, et al. Male victims of female‐perpetrated intimate partner violence, help‐seeking, and reporting behaviors: a qualitative study. Psychol Men Mascul. 2020;21(2):213–223. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Hines D, Douglas E. Intimate terrorism by women towards men: does it exist? J Aggress Conflict Peace Res. 2010;2(3):36–56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Corbally M. Accounting for intimate partner violence: a biographical analysis of narrative strategies used by men experiencing IPV from their female partners. J Interpers Violence. 2015;30:3112–3132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Douglas EM, Hines DA, McCarthy SC. Men who sustain female‐to‐male partner violence: factors associated with where they seek help and how they rate those resources. Violence Vict. 2012;27(6):871–894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Vogel DL, Heimerdinger‐Edwards SR, Hammer JH, Hubbard A. Boys don't cry”: examination of the links between endorsement of masculine norms, self‐stigma, and help‐seeking attitudes for men from diverse backgrounds. J Couns Psychol. 2011;58(3):368–382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Douglas EM, Hines DA. The helpseeking experiences of men who sustain intimate partner violence: an overlooked population and implications for practice. J Fam Violence. 2011;26(6):473–485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Choi AWM, Wong JYH, Kam CW, Lau CL, Wong JKS, Lo RTF. Injury patterns and help‐seeking behavior in Hong Kong male intimate partner violence victims. J Emerg Med. 2015;49(2):217–226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Deshpande S. Sociocultural and legal aspects of violence against men. J Psychosex Health. 2019;1(3–4):246–249. [Google Scholar]

- 26. Cheung M, Leung P, Tsui V. Asian male domestic violence victims: services exclusive for men. J Fam Violence. 2009;24(7):447–462. [Google Scholar]

- 27. Alsawalqa RO. A qualitative study to investigate male victims’ experiences of female‐perpetrated domestic abuse in Jordan. Curr Psychol. 2021;42:5505–5520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Social Inclusion Support Center DV consultation plus 2020 . Syakai housetsu sapooto senta DV soudan plus 2020] (in Japanese), 2020. Available from: https://soudanplus.jp

- 29. Gender Equality Bureau Cabinet Office . Number of consultations at Spousal Violence Counseling and Support Centers 2022 [Haiguusya bouryoku soudanshien center ni okeru soudan kensuu to 2022] (in Japanese). 2022. Available from: https://www.gender.go.jp/policy/no_violence/e-vaw/data/pdf/soudan_kensu_r04.pdf

- 30. Barker G. Adolescents, social support and help‐seeking behaviour. An international literature review and programme consultation with recommendations for action. World Health Organization; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 31. Gender Equality Bureau Cabinet Office . Report of the Survey on Violence between Men and Women, March 2021. Report of the Survey on Violence between Men and Women. 2021. [Reiwa 3nen 3gatsu nai. Danjyo kan ni okeru boryoku ni kansuru tyosa houkoku syo 2021] (in Japanese). 2021.

- 32. Hines DA, Douglas EM. Influence of intimate terrorism, situational couple violence, and mutual violent control on male victims. Psychol Men Mascul. 2018;19(4):612–623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Act on the Prevention of Spousal Violence and the Protection of Victims . Act No. 68 of June 17, 2022 [Haigusya karano bouryoku no boushi oyobi higaisya no hogo tou ni kansuru houritsu] (in Japanese). 2023.

- 34. Act on the Prevention of Spousal Violence and the Protection of Victims . [Haiguusya karano bouryoku no bousihi oyobi higaisya no hogo tou ni kansuru houritsu] (in Japanese). 2001.

- 35. Barber CF. Domestic violence against men. Nurs Stand. 2008;22(51):35–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Drijber BC, Reijnders UJL, Ceelen M. Male victims of domestic violence. J Fam Violence. 2013;28:173–178. [Google Scholar]

- 37. Dutton DG, White KR. Male victims of domestic violence. New male studies. Int J. 2013;2(1):5–17. [Google Scholar]

- 38. Mechem CC, Shofer FS, Reinhard SS, Hornig S, Datner E. History of domestic violence among male patients presenting to an urban emergency department. Acad Emerg Med. 1999;6(8):786–791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Police department criminal situation . [Keisatsutyo Reiwa ninenn no hanzai jyousei 2022] (in Japanese). 2022.

- 40. Morishita J, Kato R, Yasuda M, Suda S. Male intimate partner violence (IPV) victims in Japan: Associations of types of harm, sociodemographic characteristics, and depression trait. Psychiatr Clin Neurosci Rep. 2023;2(3):e127. 10.1002/pcn5.127.] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Cross Marketing . Online survey. 2022. Available from: https://www.cross-m.co.jp

- 42. Hines DA, Douglas EM. Relative influence of various forms of partner violence on the health of male victims: study of a help seeking sample. Psychol Men Mascul. 2016;17(1):3–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Morgan W, Wells M. ‘It's deemed unmanly’: men's experiences of intimate partner violence (IPV). The. J Forens Psychiatr Psychol. 2016;27(3):404–418. [Google Scholar]

- 44. Black MC, Basile KC, Breiding MJ, Smith SG, Walters ML, Merrick MT, et al. National intimate partner and sexual violence survey. 75. Atlanta, GA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 45. Hines DA, Douglas EM. The reported availability of U.S. domestic violence services to victims who vary by age, sexual orientation, and gender. Partner Abuse. 2011;2(1):3–30. [Google Scholar]

- 46. Muramatsu K, Kamijima K. The assessment screening tool of primary care and depressive symptoms. Patient Health Questionnaire‐9 Japanese version, about the mental and physical questionnaire. Diag Treatment. 2009;97(7):7. [Google Scholar]

- 47. Muramatsu K, Miyaoka H, Kamijima K, Muramatsu Y, Tanaka Y, Hosaka M, et al. Performance of the Japanese version of the Patient Health Questionnaire‐9 (J‐PHQ‐9) for depression in primary care. Gen Hosp Psychistry. 2018;52:64–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Ishii T, Asukai N, Kimura Y. To create the scale of screening of Domestic Violence (DVSI) and to examine their reliability and validity. Seishin igaku (in Japanese). 2003;45(8):817–823. [Google Scholar]

- 49. Morishita J, Yasuda M, Hukuda K, Kobayashi T, Suda S. Perspectives on domestic violence in Japan: a review study of court precedent for marital lawsuits. Jpn Bullet Soc Psychiatry. 2022;31(1):9–29. [Google Scholar]

- 50. Katz MH. Multiple analyses for medical research. second version. From standard generalized linear models to generalized estimation equations. a practical guide for selecting, constructing, and examining the optimal model. 25 August. Tokyo: Medical Science International; 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 51. Statistics Bureau. Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications . Labor Force Survey (Basic Tabulation) Results for June 2023. June 2023 [Roudouryoku tyousa kihon syuukei 2023 nen (reiwa 5 nen) 2023 nen 6 gatsubun kekka] (in Japanese). 2023.

- 52. Hines DA, Brown J, Dunning E. Characteristics of callers to the domestic abuse helpline for men. J Fam Violence. 2007;22(2):63–72. [Google Scholar]

- 53. Straus MA. Domestic violence and homicide antecedents. Bull N Y Acad Med. 1986;62(62):446–465. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Straus MA. Women's violence toward men is a serious social problem. In: Current controversies on family violence. 2005. p.55–77. [Google Scholar]

- 55. Hirigoyen M. Le harcèlement moral, Syros. Paris; 1998.

- 56. National Institute for Labour Policy and Training . [Figure 12 Households with Full‐Time Housewives and Households with Two‐Workers. 1980–2022] Zu 12 Sengyou syuhu setai to tomobataraki setai 1980 nen kara 2022 nen (in Japanese). 2023.

- 57. Uehara R. Rupo Abused survivors. [Rupo gyakutai survivor] (in Japanese). Tokyo: Kabushiki kaisya syuueisya; 2022. [Google Scholar]

- 58. Kgatle MO, Mafa P. Absent voices: help‐seeking behaviour among South African male victims of intimate partner violence. Technium Soc Sci. 2021;24:717–728. [Google Scholar]

- 59. Cho H, Seon J, Han J‐B, Shamrova D, Kwon I. Gender differences in the relationship between the nature of intimate partner violence and the survivor's help‐seeking. Violence Against Women. 2020;26(6–7):712–729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Lysova A, Dim EE. Severity of victimization and formal help seeking among men who experienced intimate partner violence in their ongoing relationships. J Interpers Violence. 2022;37(3–4):1404–1429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Nihon gakujyutu kaigi syakaigaku iinkai . Web tyosano kadaini kansuru kento bunkakai (in Japanese) 2020; iii:1–6. Available from: https://www.scj.go.jp/ja/info/kohyo/pdf/kohyo-24-t292-3.pdf

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, S.S., upon reasonable request.