Abstract

The mechanism of the progressive loss of CD4+ T lymphocytes, which underlies the development of AIDS in human immunodeficiency virus (HIV-1)-infected individuals, is unknown. Animal models, such as the infection of Old World monkeys by simian-human immunodeficiency virus (SHIV) chimerae, can assist studies of HIV-1 pathogenesis. Serial in vivo passage of the nonpathogenic SHIV-89.6 generated a virus, SHIV-89.6P, that causes rapid depletion of CD4+ T lymphocytes and AIDS-like illness in monkeys. SHIV-KB9, a molecularly cloned virus derived from SHIV-89.6P, also caused CD4+ T-cell decline and AIDS in inoculated monkeys. It has been demonstrated that changes in the envelope glycoproteins of SHIV-89.6 and SHIV-KB9 determine the degree of CD4+ T-cell loss that accompanies a given level of virus replication in the host animals (G. B. Karlsson et. al., J. Exp. Med. 188:1159–1171, 1998). The envelope glycoproteins of the pathogenic SHIV mediated membrane fusion more efficiently than those of the parental, nonpathogenic virus. Here we show that the minimal envelope glycoprotein region that specifies this increase in membrane-fusing capacity is sufficient to convert SHIV-89.6 into a virus that causes profound CD4+ T-lymphocyte depletion in monkeys. We also studied two single amino acid changes that decrease the membrane-fusing ability of the SHIV-KB9 envelope glycoproteins by different mechanisms. Each of these changes attenuated the CD4+ T-cell destruction that accompanied a given level of virus replication in SHIV-infected monkeys. Thus, the ability of the HIV-1 envelope glycoproteins to fuse membranes, which has been implicated in the induction of viral cytopathic effects in vitro, contributes to the capacity of the pathogenic SHIV to deplete CD4+ T lymphocytes in vivo.

Human immunodeficiency viruses (HIV-1 and HIV-2) and the related simian immunodeficiency viruses (SIV) cause AIDS in humans and Old World monkeys, respectively (3, 10, 13, 14, 19, 41). AIDS results from the progressive loss of CD4+ T lymphocytes (16, 17). The mechanisms underlying the destruction of CD4+ T lymphocytes in HIV- or SIV-infected primate hosts have not been elucidated. The specific destruction of CD4+ T cells in infected hosts should be distinguished from the generalized state of immune system activation and the resultant increase in the number of apoptotic lymphocytes that accompany these persistent viral infections (21, 22, 50). This increased level of apoptosis is not limited to CD4+ T cells, but also involves CD8+ T lymphocytes and B lymphocytes (18, 21, 22, 50, 52), which are not typically decreased in number in HIV- or SIV-infected hosts (16, 17). The degree of apoptosis does not necessarily correlate with viral burden (50, 52), in contrast to the rate of CD4+ T-cell depletion, which is strongly dependent upon the level of virus replication (7, 14, 46, 49, 63). Studies of virus and cell turnover in HIV-1-infected humans (25, 74) suggest that virus-producing cells, but not latently infected cells, undergo rapid destruction, apparently through nonapoptotic pathways (18). Thus, virus-driven mechanisms such as virus-induced cytopathic effects and immunologic clearance of infected cells may make important contributions to the specific loss of CD4+ T lymphocytes in HIV-1-infected individuals.

Several HIV-1 components have been associated with cytotoxic effects in tissue-cultured cells. The acute cytopathic changes observed in virus-infected cultures include the formation of multinucleated syncytia and the lysis of single cells (12, 19, 66, 68). Both of these forms of cytopathic effect can be mediated by the viral envelope glycoproteins (6, 34, 38, 40, 45, 65). The HIV-1 envelope glycoproteins, gp120 and gp41, support virus entry by binding to the viral receptors, CD4 and chemokine receptors, on the target cell and fusing the viral and the target cell membranes (8, 51, 70, 75, 77). HIV-1 envelope glycoproteins expressed on the infected cell surface fuse these cells with receptor-bearing, uninfected cells, leading to the formation of lethal syncytia (45, 65). Intracellular envelope glycoprotein-receptor complexes (27) are capable of mediating membrane fusion reactions that lead to the lysis of single cells (6). Recent studies indicate that the majority of primary CD4+ T lymphocytes expressing HIV-1 envelope glycoproteins lyse as single cells, due to a process dependent upon the membrane-fusing capacity of the envelope glycoproteins (40).

Other HIV-1 proteins can influence cell viability. The regulatory protein Tat has been reported to induce both apoptotic and antiapoptotic effects in T cells (4, 43, 48, 56, 78). The expression of Vpr results in cytostatic effects and apoptosis in some cell lines (69). Vpr, however, is not required for CD4+ T-cell depletion and the induction of AIDS in SIV-infected monkeys (20, 26). The HIV-1 protease can also cause some cytotoxic effects, but studies of viral mutants indicate that most of the cytopathic effects associated with HIV-1 infection of tissue-cultured cells are not mediated by this enzyme (35). Nef has been reported to induce cytolysis of some murine lymphoid cells (54) but, like Vpr, is not absolutely required for the destruction of T cells and the development of AIDS in SIV-infected monkeys (1).

The study of HIV-1 pathogenesis has been advanced by the availability of animal models in which viral or host variables can be controlled. Because HIV-1 does not replicate efficiently in species other than humans and chimpanzees, chimeric simian-human immunodeficiency viruses (SHIVs) have been created that can infect Old World monkeys (28, 44, 47, 64). SHIVs contain HIV-1-derived segments encoding the viral envelope glycoproteins and the Tat, Rev, and Vpu regulatory proteins in a SIV background (28, 44, 47, 64). A SHIV containing the envelope glycoproteins of a primary HIV-1 isolate, 89.6, replicated efficiently in rhesus monkeys but did not deplete CD4+ T lymphocytes or induce disease in these animals (60). Serial transfer of blood from SHIV-89.6-infected monkeys to naive monkeys generated a virus, SHIV-89.6P, that exhibited only modest increases in replication in infected monkeys compared with SHIV-89.6 (61). However, SHIV-89.6P caused rapid loss of CD4+ T lymphocytes and, subsequently, AIDS-like illness in inoculated monkeys (61). The risk of developing AIDS-related disease in monkeys infected with SHIV-89.6P variants is strongly influenced by the degree of decline in CD4+ T lymphocytes during the acute phase of infection (2, 62).

SHIV-KB9 is a molecularly cloned, pathogenic virus derived from the SHIV-89.6P isolate (31). The proviruses of the nonpathogenic SHIV-89.6 and the pathogenic SHIV-KB9 differ in the tat and env genes and in the long terminal repeats (LTRs) (31). A recombinant virus, SHIV-89.6*, which is identical to SHIV-89.6 except that it contains the passage-associated changes in the LTR and tat gene, replicated in monkeys but was not pathogenic (32). This result demonstrated that the passage-associated changes in the LTRs and tat gene were not sufficient for the profound ability of SHIV-KB9 to deplete CD4+ T lymphocytes in monkeys. The passage-associated env changes alter the ectodomain of the gp120 and gp41 envelope glycoproteins and the cytoplasmic tail of the gp41 glycoprotein (31). The contribution of these passage-associated changes in env to pathogenesis was investigated by studying recombinant SHIVs, SHIV-KB9ecto and SHIV-KB9ct, that, in addition to the passage-associated LTR and tat changes, contain the changes in the envelope glycoprotein ectodomains or cytoplasmic tail, respectively (32). Both ectodomain and cytoplasmic tail changes were shown to contribute to small increases in the average level of virus replication achieved in infected monkeys (32). Importantly, the envelope glycoprotein ectodomain changes, but not the cytoplasmic tail changes, increase the degree of CD4+ T-cell depletion associated with a given level of virus replication in the host animal (32). In vitro studies indicated that the 89.6 and KB9 envelope glycoproteins exhibited indistinguishable levels of expression, processing, subunit association, representation on the cell and virion surface, and CD4-binding ability (15, 32). The KB9 envelope glycoproteins demonstrated increased chemokine receptor-binding affinity and membrane-fusing ability compared with the 89.6 envelope glycoproteins (15, 32). Both of these properties were determined by the gp120 and gp41 ectodomains (15, 32). Twelve amino acid differences exist between the 89.6 and KB9 envelope glycoprotein ectodomains (15, 31). The amino acid differences responsible for the increased chemokine receptor-binding affinity and membrane-fusing ability of the KB9 envelope glycoproteins have been defined (15). This study utilizes this genetic information to test the hypothesis that augmented membrane-fusing activity is important for the ability of SHIV-KB9 to deplete CD4+ T lymphocytes efficiently in vivo.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Viruses.

Mutations were introduced into the env sequence of the SHIV-KB9 3′ proviral half by using the QuickChange site-directed mutagenesis kit (Stratagene) and were confirmed by DNA sequencing. Infectious viruses were produced by transfection of CEMx174 cells with proviral DNA as described previously (32, 44). SHIV-KB9(−225) and SHIV-KB9(−305) displayed replication kinetics comparable to those of SHIV-KB9 and SHIV-89.6 in both CEMx174 cells and rhesus monkey peripheral blood mononuclear cells (data not shown).

Animals.

Rhesus macaques were divided into groups according to the inoculated virus; the groups exhibited similar average CD4+ T-lymphocyte counts prior to virus inoculation. Rhesus macaques were inoculated intravenously with 106 reverse transcriptase units of the stock viruses. The rhesus monkeys used in this study were maintained in accordance with established guidelines (53). Monkeys were anesthetized with ketamine-HCl for all inoculations and blood sampling. Peripheral lymph node biopsies were performed under Telazol anesthesia.

Lymphocyte phenotyping and p27 quantification.

Blood was obtained from the infected animals on days 3, 7 or 8, 10, 14, 17, 21, 29, and 36 after virus inoculation. Peripheral blood lymphocytes were phenotyped for CD3/CD4 and CD3/CD8, as previously described (59). Absolute lymphocyte counts in blood were determined with an automated hematology analyzer (T540; Coulter Corp., Hialeah, Fla.) that provided a partial differential count. The concentration of SIVmac p27 core antigen in the plasma was determined by using a commercial enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay kit (SIV core [p27] antigen EIA kit; Coulter Corp.).

Fresh lymph node biopsies were obtained on days 10, 14, 21, and 43 after virus inoculation; individual cells were teased out, filtered, and phenotyped as above.

Statistical analysis.

Cumulative p27 antigenemia was used as a measure of viral replication; the area under the p27-versus-time curve (days 0 to 21 following infection) was estimated using the trapezoidal method. The “set point” for CD4+ T lymphocytes for each animal was defined as the median of the absolute CD4+ T-lymphocyte counts in the peripheral blood recorded between days 14 and 36 following infection. Several mathematical models (linear and nonlinear exponential decay models, an inverse model, and a hyperbolic model) were considered to be plausible candidates for explaining the relationships between virus replication and CD4+ T-lymphocyte counts. The adjusted R2 value was used to select the best-fitting model (23). To test differences between the effect of each virus group and its interaction term on CD4+ T-lymphocyte set points, we used a partial F test with a Bonferroni-adjusted alpha value of 0.025 (23, 33).

In situ hybridization for SHIV RNA in lymph nodes.

In situ hybridization of lymph nodes obtained on day 10 after virus inoculation was carried out as previously described (32, 71). Cells with at least 20 silver grains, which corresponded to a sixfold increase in silver grains over the background level, were scored as viral RNA positive. By using epiluminescent illumination, viral RNA-positive cells in 10 standard areas (450 by 700 μm) of the T-cell-dependent zones in the lymph nodes were counted with a 20× objective and the mean values were calculated.

RESULTS

SHIV envelope glycoprotein variants and phenotypes.

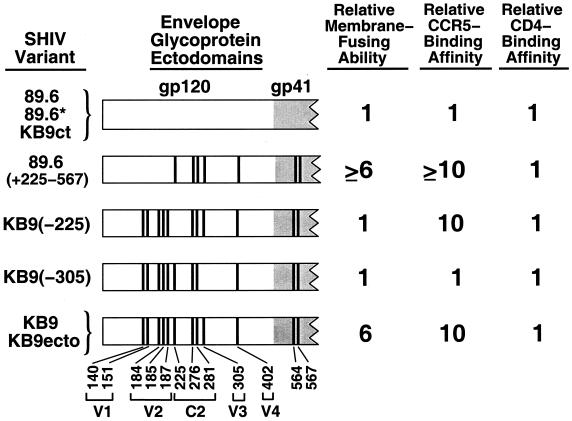

The envelope glycoprotein ectodomains of the SHIV variants used in this study are depicted in Fig. 1. SHIV-89.6*, SHIV-KB9ct, and SHIV-KB9ecto are recombinants between the parental SHIV-89.6 and the pathogenic SHIV-KB9 (31). SHIV-89.6∗ is identical to SHIV-89.6 except that it contains the passage-associated changes in the LTR and tat gene. SHIV-KB9ct contains, in addition, the passage-associated changes in the gp41 cytoplasmic tail. Thus, the envelope glycoprotein ectodomains of SHIV-89.6, SHIV-89.6*, and SHIV-KB9ct are identical. As the membrane-fusing capacity of SHIV-89.6/SHIV-KB9 recombinants is determined by the envelope glycoprotein ectodomains (15, 32), SHIV-89.6* and SHIV-KB9ct exhibit a membrane-fusing ability comparable to that of the parental SHIV-89.6. SHIV-KB9ecto contains the passage-associated changes in the LTR, tat gene, and the envelope glycoprotein ectodomains. Thus SHIV-KB9ecto and SHIV-KB9 share envelope glycoprotein ectodomains and exhibit a high level of membrane-fusing ability (15, 32).

FIG. 1.

Structure and biological properties of the HIV-1 envelope glycoproteins used in this study. The envelope glycoprotein ectodomains of the SHIV variants used in this study are depicted. The gp41 ectodomain is shaded gray. The vertical bars represent the positions of amino acids that are altered in the pathogenic SHIV-KB9, compared with the parental SHIV-89.6 (31). The residue number is indicated beneath the diagram, with numbering according to recommended convention (37). The gp120 variable (V1 to -4) and conserved (C2) regions in which the residues are located are indicated. The SHIV-89.6, SHIV-89.6*, and SHIV-KB9ct envelope glycoprotein ectodomains are identical, as are those of SHIV-KB9 and SHIV-KB9ecto. The relative membrane-fusing ability of the envelope glycoproteins was determined by cocultivating cells expressing comparable levels of surface envelope glycoproteins with CEMx174 lymphocytes for 6 h at 37°C. The number of syncytia formed was counted and normalized to that seen for the 89.6 envelope glycoproteins (15). The relative ability of the gp120 glycoproteins to bind to cells expressing the CCR5 chemokine receptor in the presence of soluble CD4 was determined as described previously (15, 32). The binding obtained for the 89.6 gp120 glycoprotein was assigned a value of 1. Relative CD4-binding ability was evaluated as described previously (32) and was normalized to that of the 89.6 gp120 glycoprotein.

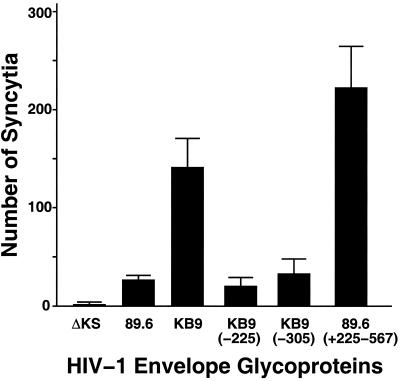

The SHIV-KB9 gp120 and gp41 ectodomains differ from those of SHIV-89.6 in 12 amino acid residues (15, 31, 32). In a previous study (15), each of these 12 amino acid residues in the KB9 envelope glycoproteins was changed back to the residue found in the 89.6 envelope glycoproteins, and the effect of the changes on membrane-fusing ability was evaluated. We found that two mutants, KB9(−225) and KB9(−305), with single amino acid changes in KB9 gp120 residues isoleucine 225 and glutamic acid 305, respectively, exhibited membrane fusion activity similar to that of the 89.6 envelope glycoproteins (Fig. 1). The ability of the 89.6, KB9, KB9(−225), and KB9(−305) envelope glycoproteins to induce the formation of syncytia in a CD4+ lymphocyte line is illustrated in Fig. 2. The KB9 envelope glycoproteins induced approximately five to six times as many syncytia as the 89.6 envelope glycoproteins. The syncytium-forming abilities of the KB9(−225) and KB9(−305) mutants were comparable to that of the 89.6 envelope glycoproteins. These results are similar to those previously obtained in other CD4+ cell lines and in primary CD4+ T lymphocytes (15, 40). Some mechanistic insights into these phenotypes have been obtained (15) and are summarized in Fig. 1. The change in isoleucine 225, within the second conserved (C2) gp120 region, does not affect the interactions of the envelope glycoproteins with either CD4 or the chemokine receptors (15). Instead, this change apparently alters gp120-gp41 interactions that are important for achieving fusion-competent conformations of the envelope glycoprotein complex (15). The change in glutamic acid 305, within the gp120 third variable (V3) loop, affects membrane fusogenic capacity by decreasing the affinity of gp120 for the chemokine receptors (15). Thus, changes in gp120 residues 225 and 305, which are located on opposite faces of the native gp120 glycoprotein (39), exert quantitatively similar effects on membrane-fusing activity by different mechanisms.

FIG. 2.

Syncytium-forming ability of the HIV-1 envelope glycoprotein variants. COS-1 cells expressing equivalent surface levels of the indicated HIV-1 envelope glycoproteins were cocultivated at 37°C with CEMx174 CD4+ lymphocytes, and syncytia were scored after 6 h as described previously (15). Control COS-1 cells were transfected with the ΔKS plasmid, which does not express functional envelope glycoproteins. Means and standard deviations of duplicate experiments are indicated.

Replacement of the other 10 KB9 envelope glycoprotein residues that were altered during virus passage with the amino acid residues found in the 89.6 envelope glycoproteins either did not attenuate membrane fusogenic capacity or exerted less dramatic effects on this property (15). As an example of the former phenotype, the five passage-associated changes in the KB9 gp120 V1/V2 variable loops were not necessary for efficient syncytium-forming ability in tissue culture [see the 89.6(+225–567) recombinant in Fig. 1 and 2]. Each of the seven passage-associated amino acid residues remaining in the 89.6(+225–567) envelope glycoproteins was found to contribute to the full syncytium-forming ability of this glycoprotein (15).

Investigation of passage-associated changes sufficient for CD4+ T-cell depletion.

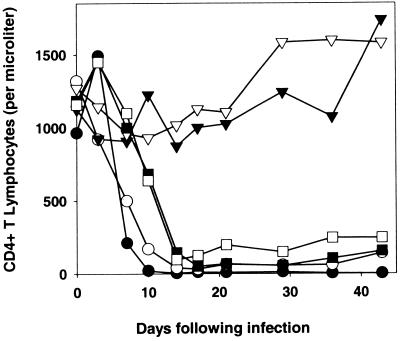

The SHIV-89.6(+225/567) envelope glycoproteins retain all of the KB9 envelope glycoprotein residues, including isoleucine 225 and glutamic acid 305, shown to contribute to enhanced membrane-fusing activity (15). To examine whether the changes in these residues were sufficient for the ability of SHIVs to cause CD4+ T-cell depletion in vivo, two rhesus monkeys were inoculated with SHIV-89.6*, SHIV-KB9, or SHIV-89.6(+225–567). As mentioned above, SHIV-89.6* is identical to the parental SHIV-89.6 except that it contains the passage-associated changes in the LTR and tat gene (32). SHIV-89.6(+225–567) is identical to SHIV-89.6 except that it contains the seven passage-associated amino acid changes spanning the gp120 carboxy-terminal half and the gp41 ectodomain (Fig. 1). The absolute CD4+ T-lymphocyte counts in the inoculated monkeys are shown in Fig. 3. Precipitous and profound decreases in CD4+ T lymphocytes were observed in the monkeys infected with SHIV-KB9 and SHIV-89.6(+225–567), but not in the monkeys infected with SHIV-89.6*. These results indicate that the seven amino acid changes in the gp120 and gp41 ectodomain segment encompassing residues 225 to 567 are sufficient to convert SHIV-89.6 into a virus capable of causing rapid CD4+ T-lymphocyte decline in rhesus monkeys. The results also show that the passage-associated changes in the SHIV-KB9 gp120 V1/V2 loops (and in the LTR, Tat protein, and gp41 cytoplasmic tail) are not required for efficient CD4+ T-cell depletion in SHIV-infected monkeys.

FIG. 3.

CD4+ T-lymphocyte counts in rhesus monkeys infected with SHIV variants. Two rhesus monkeys were inoculated intravenously with SHIV-89.6* (▿, ▾), SHIV-KB9 (○, ●), or SHIV-89.6(+225–567) (□, ■). The absolute CD4+ T-lymphocyte counts in the peripheral blood of the infected monkeys are shown, with normal values in uninfected animals ranging from 1,000 to 1,400 cells per microliter.

Effects of membrane fusion attenuation on CD4+ T-cell-depleting ability of SHIVs.

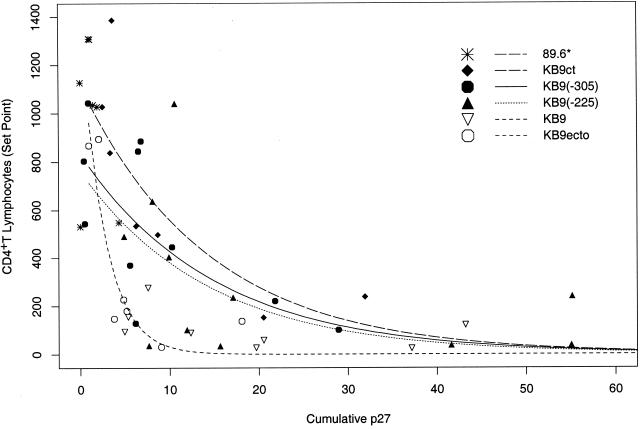

We wished to investigate the effects of the membrane fusion-attenuating changes in gp120 residues 225 and 305 on the intrinsic CD4+ T-cell-depleting ability of SHIV-KB9, i.e., the efficiency with which SHIV-KB9 depletes CD4+ T lymphocytes at a given level of virus replication in vivo. The degree of CD4+ T-cell loss in SHIV-infected monkeys is influenced by the level of virus replication, which can vary widely even among animals inoculated with identical viruses (32). Thus, an assessment of the intrinsic CD4+ T-cell-depleting ability of SHIV-KB9 variants requires the evaluation of virus replication levels and CD4+ T-cell counts in numerous monkeys. Previous studies defined the relationship between the level of virus replication and the degree of CD4+ T-lymphocyte depletion in rhesus monkeys infected by SHIV-KB9/SHIV-89.6 recombinants that differ only in the sequences of the envelope glycoprotein ectodomains (32). Analysis of this data using a nonlinear exponential decay model indicated that, at a given level of replication, viruses (SHIV-KB9 and SHIV-KB9ecto) with KB9 ectodomain sequences deplete CD4+ T lymphocytes more efficiently than viruses (SHIV-89.6* and SHIV-KB9ct) with 89.6 ectodomain sequences (P < 0.001) (32). The only sequence differences between SHIV-KB9 and SHIV-KB9ecto, or between SHIV-89.6* and SHIV-KB9ct, occur in the gp41 cytoplasmic tail and do not contribute significantly to the efficiency of CD4+ T-cell loss (32). To examine the potential contribution of membrane fusogenicity to increased CD4+ T-cell-depleting ability, SHIV-KB9 derivatives altered in gp120 residues 225 and 305 [SHIV-KB9(−225) and SHIV-KB9(−305), respectively] were created and inoculated intravenously into 11 rhesus monkeys each. Additional monkeys were infected with SHIV-KB9 as controls. The data obtained from these animals and from the animals in the aforementioned study (32) were included in the analysis of virus replication and CD4+ T-cell counts (Table 1). The level of virus replication achieved in each monkey was described by the cumulative antigenemia detected over the initial 3 weeks of infection, by which time the major decline in CD4+ T lymphocytes occurs in monkeys infected with pathogenic SHIVs (Fig. 3). The CD4+ T-lymphocyte set point was defined as the median of the absolute CD4+ T-lymphocyte counts in the peripheral blood between days 14 and 36 after virus inoculation, when CD4+ T-cell counts typically stabilize in SHIV-infected monkeys (31, 32, 61). The relationship between cumulative antigenemia and the CD4+ T-lymphocyte set point in the SHIV-infected monkeys is shown in Fig. 4. For the analysis of these data, the infecting viruses were organized into four groups: viruses with 89.6 envelope glycoprotein ectodomains (SHIV-89.6* and SHIV-KB9ct), viruses with KB9 envelope glycoprotein ectodomains (SHIV-KB9 and SHIV-KB9ecto), SHIV-KB9(−225), and SHIV-KB9(−305). The data were analyzed using a nonlinear exponential decay model; this model was chosen based on the adjusted R2 value, which represents the proportion of variability in CD4+ T-lymphocyte levels explained by the model (23, 33, 67) (Table 2). The chosen model contains a virus group-replication interaction term in addition to the main effect terms, thus allowing the shapes of the curves to vary independently by virus group. The interaction term improved the model's ability to capture the sharp changes in CD4+ T-lymphocyte set points occurring at low levels of cumulative antigenemia. Partial F tests revealed significant differences in CD4+ T-cell-depleting ability between either SHIV-KB9(−225) or SHIV-KB9(−305) and the SHIVs with KB9 ectodomain sequences (Table 3). The mean values for cumulative antigenemia did not differ significantly among these three groups of viruses [mean values were 21.6, 16.6, and 17.5 ng/day/ml for SHIV-KB9(−225), SHIV-KB9(−305), and the SHIV-KB9/SHIV-KB9ecto group, respectively]. There were no significant differences in CD4+ T-cell-depleting ability between SHIV-KB9(−225) and SHIV-KB9(−305) (P = 0.62) or between either of these viruses and the viruses with the 89.6 ectodomain sequences. Analysis of the data using the next best model, an inverse model with interaction terms, yielded the same conclusions (Tables 2 and 3). Thus, the passage-associated changes in residues 225 and 305 each significantly contribute to the increased intrinsic efficiency with which viruses with KB9 envelope glycoprotein ectodomains deplete CD4+ T lymphocytes in SHIV-infected monkeys.

TABLE 1.

Virus replication and CD4+ T lymphocytes in SHIV-infected monkeysa

| SHIV variant | Monkey | Cumulative p27 antigenemiab | CD4 T-lymphocyte set pointc | Viral RNA-positive cells in lymph nodesd |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SHIV-89.6* | 15140 | 1.93 | 1027 | 0.8 |

| 15023 | 1.0 | 1309 | ND | |

| 18431 | 4.31 | 547 | 14.0 | |

| 18408 | 0 | 1127 | ND | |

| 13893 | 1.12 | 1307 | ND | |

| 14468 | 1.47 | 1035 | ND | |

| 18331 | 0 | 531 | ND | |

| SHIV-KB9ct | 18390 | 3.37 | 838 | 3.5 |

| 15655 | 3.65 | 1386 | 8.5 | |

| 13898 | 2.52 | 1027 | 1.2 | |

| 18284 | 8.67 | 497 | 6.9 | |

| 15865 | 6.23 | 533 | 7.0 | |

| 13939 | 20.51 | 152 | 38.5 | |

| 11796 | 31.92 | 237 | 34.4 | |

| SHIV-KB9(−225) | 14315 | 17.1 | 235 | 0.22 |

| 17534 | 4.9 | 490 | 0 | |

| 18393 | 55.14 | 239 | 0.12 | |

| 13575 | 15.66 | 34 | ND | |

| 15842 | 9.92 | 403 | ND | |

| 19239 | 55.05 | 37 | 39.4 | |

| 15402 | 41.61 | 37 | 17.2 | |

| 17024 | 11.92 | 101 | 15.8 | |

| 18970 | 8.1 | 636 | 2.0 | |

| 18971 | 10.6 | 1040 | 5.8 | |

| 19952 | 7.67 | 36 | 10.4 | |

| SHIV-KB9(−305) | 20103 | 6.49 | 844 | 1.66 |

| 14239 | 94.83 | 69 | 0 | |

| 19941 | 0.95 | 1043 | 0.14 | |

| 13831 | 21.8 | 220 | 1.4 | |

| 18340 | 6.81 | 885 | 0.53 | |

| 19019 | 28.96 | 100 | 19.6 | |

| 17076 | 0.44 | 804 | 0 | |

| 18354 | 0.52 | 543 | ND | |

| 18396 | 10.26 | 443 | 2.5 | |

| 18946 | 5.55 | 369 | 3.83 | |

| 19931 | 6.18 | 128 | 9.5 | |

| SHIV-KB9ecto | 15669 | 1.0 | 868 | ND |

| 16155 | 4.83 | 227 | 39.5 | |

| 15487 | 5.19 | 180 | 37.7 | |

| 14122 | 2.1 | 895 | ND | |

| 13945 | 3.78 | 147 | 48.0 | |

| 13916 | 9.04 | 30 | 56.3 | |

| 18430 | 18.08 | 137 | 27.8 | |

| SHIV-KB9 | 15823 | 4.95 | 94 | 69.6 |

| 13950 | 7.58 | 276 | 33.6 | |

| 13921 | 5.36 | 155 | 22.6 | |

| 13930 | 12.35 | 89 | 10.8 | |

| 15431 | 37.17 | 24 | 90.5 | |

| 13970 | 19.71 | 27 | 29.5 | |

| 13876 | 43.22 | 121 | 45.6 | |

| 14379 | 84.63 | 9 | 16.75 | |

| 18395 | 20.55 | 58 | 2.2 |

Some of the data for monkeys infected with SHIV-89.6*, SHIV-KB9ct, SHIV-KB9ecto, and SHIV-KB9 were previously reported in reference 32.

The cumulative p27 antigenemia represents the area under the plasma p27 antigen-versus-time curve for days 0 to 21 following infection and was estimated using the trapezoidal method.

The CD4+ T-lymphocyte set point is the median of the absolute CD4+ T-lymphocyte counts in peripheral blood recorded between 14 and 36 days after virus inoculation.

Viral RNA-expressing cells in the T-cell-dependent areas of the lymph nodes on day 10 after virus inoculation were scored as described in Materials and Methods. ND, not determined.

FIG. 4.

Relationship between viremia and CD4+ T-lymphocyte counts in monkeys infected with SHIV variants. The set point value for the peripheral blood CD4+ T-cell counts was plotted against the cumulative p27 antigenemia for each infected animal. The curves were fitted to the data using a nonlinear exponential decay model with a viral group-replication interaction term (23, 67). A single curve was fitted to the data for SHIV-KB9 and SHIV-KB9ecto, which both contain KB9 envelope glycoprotein ectodomains; likewise, a single curve was fitted to the data for SHIV-89.6* and SHIV-KB9ct, which contain the 89.6 envelope glycoprotein ectodomains.

TABLE 2.

Characteristics of the best-fitting modelsa

| Model | Comparison group | Interaction term? | SHIV variant

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SHIV-KB9(−225)

|

SHIV-KB9(−305)

|

|||||

| F (df) | R2 (%) | F (df) | R2 (%) | |||

| Nonlinear exponential decayb | SHIV-KB9/SHIV-KB9ecto | No | 51 (4, 37) | 83 | 65 (4, 37) | 86 |

| Yes | 50 (5, 36) | 86 | 66 (5, 36) | 89 | ||

| Inversec | SHIV-KB9/SHIV-KB9ecto | No | 16 (3, 37) | 54 | 15 (3, 37) | 51 |

| Yes | 23 (4, 36) | 69 | 35 (4, 36) | 77 | ||

The relationship between cumulative antigenemia and the CD4+ T-lymphocyte set point in the SHIV-infected monkeys was analyzed using a nonlinear exponential decay model or an inverse model (23, 67). Each model was considered with or without a virus group-replication interaction term; the interaction term allowed the shapes of the curves to vary independently by virus group. The F statistic describes goodness of fit, and the adjusted R2 value describes the proportion of variability explained by the model (23, 33). The degrees of freedom (df) for the F statistics are shown in parentheses. The F statistics and adjusted R2 values for the comparisons of the SHIV-KB9(−225) and SHIV-KB9(−305) viruses with the SHIV-KB9/SHIV-KB9ecto group are shown for each model.

The formula for the nonlinear exponential decay model with interaction term is  , where CD4 is the CD4+ T-lymphocyte set point and p27 is the cumulative p27 antigenemia.

, where CD4 is the CD4+ T-lymphocyte set point and p27 is the cumulative p27 antigenemia.

The formula for the inverse model with interaction term is CD4 = 1/(β0 + β1 p27 + β2 virus group + β3 [p27 × virus group]) + ɛ, where CD4 is the CD4+ T-lymphocyte set point and p27 is the cumulative p27 antigenemia.

TABLE 3.

P values for tests of significant differences among the virusesa

| Model | Comparison group | SHIV-KB9 (−225) | SHIV-KB9 (−305) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nonlinear exponential decay model with interaction term | SHIV-KB9 and SHIV-KB9ecto (KB9 envelope glycoprotein ectodomains) | 0.01 | 0.002 |

| SHIV-89.6* and SHIV-KB9ct (89.6 envelope glycoprotein ectodomains) | 0.39 | 0.062 | |

| Inverse model with interaction term | SHIV-KB9 and SHIV-KB9ecto (KB9 envelope glycoprotein ectodomains) | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| SHIV-89.6* and SHIV-KB9ct (89.6 envelope glycoprotein ectodomains) | 0.147 | 0.782 |

Groups of animals infected with SHIV-KB9(−225) or SHIV-KB9(−305) were each compared with groups of animals infected with the indicated viruses by using either a nonlinear exponential decay model or an inverse model, each with a viral group-replication interaction term. P values are from partial F tests (23, 33).

Analysis of lymph nodes from SHIV-infected monkeys.

The lymph nodes of all of the macaques infected by SHIV variants in this study and the majority of macaques infected in a previous study (32) were examined. Analysis of lymph nodes taken from the monkeys on days 10, 14, 21, and 43 after virus inoculation revealed that the percentage of CD4+ T lymphocytes in the lymph nodes corresponded to the value observed in the peripheral blood at all of these time points (data not shown). Close inspection of the T-cell-dependent areas of the lymph nodes did not reveal the presence of syncytia (data not shown).

The number of cells in the T-cell-dependent areas of the lymph nodes that were expressing SHIV RNA on day 10 after virus inoculation was determined by in situ hybridization (71) (Table 1). Previous studies of SHIV-KB9 variants showed that the number of virus-expressing cells in the lymph nodes peaked around day 10 of infection (32, 62). To investigate the relationship between the number of viral RNA-positive cells in the lymph nodes and the peripheral blood CD4+ T-lymphocyte set point, a nonlinear exponential decay model was again employed (23, 67). The model had an R2 value of 65%, indicating that it explained a relatively large proportion of the variability. There was a statistically significant exponential decline in the CD4+ T-cell set point as the number of viral RNA-positive cells increased (P = 0.03). Thus, in monkeys infected by the SHIVs studied herein, there is a close relationship between the number of virus-expressing cells and the overall decline in CD4+ T lymphocytes.

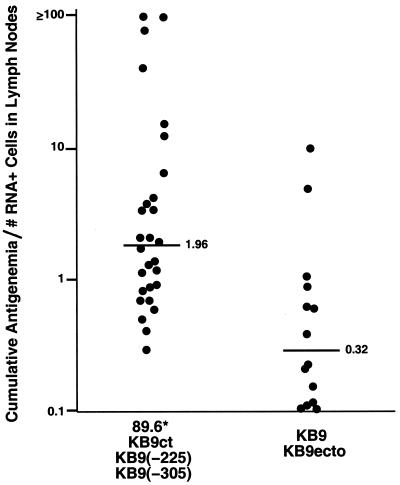

The observed effects of env changes on the efficiency of CD4+ T-cell depletion and the relationship between the number of virus-producing cells and CD4+ T-cell loss imply that changes in the membrane fusogenicity of the infecting SHIV might alter the balance between the level of viremia and the number of virus-producing cells. To examine this, we used the number of viral RNA-positive cells in the lymph nodes on day 10 after infection as an indicator of the virus-producing cell burden in the animals. The ratio of cumulative antigenemia to the number of viral RNA-positive cells was compared between groups of viruses with membrane fusogenicity equivalent to that of either SHIV-89.6 or SHIV-KB9. Figure 5 shows that this ratio was significantly lower for SHIV variants with greater membrane fusogenicity (P = 0.0006; Wilcoxon rank sum test).

FIG. 5.

Ratio of viremia to the number of virus-producing cells in macaques infected with SHIV variants differing in membrane fusogenicity. The ratio of the cumulative antigenemia to the number of viral RNA-positive cells measured in the lymph nodes on day 10 after infection is shown for macaques infected with SHIV variants with less fusogenic envelope glycoproteins [89.6*, KB9ct, KB9(−225), and KB9(−305)], compared with that for SHIV variants with more fusogenic envelope glycoproteins (KB9 and KB9ecto). In the three instances in which viral RNA-positive cells in the lymph nodes were undetectable, the lowest detectable value, 0.12, was used to calculate the ratio. The median values for the two groups are 1.96 and 0.32, respectively (P = 0.0006; Wilcoxon rank sum test).

DISCUSSION

The ability of the HIV-1 envelope glycoproteins to fuse cellular membranes is critical for in vitro cytopathic effects (6, 38, 40, 45, 65), which include syncytium formation and single cell lysis. The use of an animal model in which primate hosts are infected with defined viruses allowed us to test the hypothesis that the membrane-fusing capacity of the HIV-1 envelope glycoproteins contributes to CD4+ T-lymphocyte-depleting ability in vivo. In support of this hypothesis, a close relationship between the membrane fusogenicity and in vivo CD4+ T-cell-depleting ability of SHIV variants was observed. A SHIV identical to the nonpathogenic parental virus, except for the seven envelope glycoprotein residues required for efficient membrane-fusing capacity, caused rapid and profound CD4+ T-cell depletion in the monkeys. Several of the changes that arose during in vivo passage of the pathogenic SHIV-KB9, for example the changes in the gp120 V1/V2 variable loops or the gp41 cytoplasmic tail, did not increase membrane fusogenicity (15, 32) and were dispensable for efficient CD4+ T-cell destruction in SHIV-infected monkeys. By contrast, the changes in gp120 residues 225 and 305 affected both in vitro membrane fusion activity and the efficiency with which SHIV-KB9 depleted CD4+ T lymphocytes at a given level of in vivo replication. Because of the possibility of reversion of the introduced mutations during the experiments, the actual impact of the changes in residues 225 and 305 on in vivo CD4+ T-cell-depleting ability may be greater than that observed. Nonetheless, both of these mutant SHIVs exhibited relationships between CD4+ T lymphocyte depletion and virus replication that were statistically indistinguishable from those seen for the group of nonpathogenic SHIV variants (SHIV-89.6* and KB9ct). Both gp120 changes alter membrane fusogenicity by different mechanisms, but do not affect envelope glycoprotein processing, cell surface expression, subunit association, CD4 binding affinity, or coreceptor choice (15, 32). The buried position of residue 225 in the gp120 structure (39) essentially restricts the potential interactions of this residue to those involving other elements of the envelope glycoproteins. These observations strongly argue that the ability to fuse membranes, and not another fortuitously altered property of the envelope glycoproteins, is important for the destruction of CD4+ T cells in SHIV-infected animals.

A close relationship between the number of virus-producing cells and the degree of CD4+ T-lymphocyte decline exists in SHIV-infected monkeys (32). Enhanced membrane fusogenicity of the viral envelope glycoproteins would be expected to increase the efficiency of new infections and to decrease the vitality of at least the virus-producing cells. This would increase the pool of infected cells destined for destruction without necessarily modifying the level of viremia. Thus, changes in the intrinsic ability of the virus to damage virus-producing cells would alter the usual relationship (55, 58, 71, 76) between the number of cells expressing viral products and viremia. Consistent with this model, the ratio of cumulative viremia to the number of viral RNA-positive cells in lymph nodes was lower for SHIVs with more fusogenic envelope glycoproteins than for the SHIVs with less fusogenic envelope glycoproteins.

As in most HIV-1-infected humans and SIV-infected monkeys (42, 52, 55, 57), syncytia are not prominent in the lymph nodes of SHIV-infected animals. The rarity of multinucleated cells in vivo is not inconsistent with a contribution of envelope glycoprotein membrane fusogenicity to the demise of virus-producing cells. Recent studies indicate that the HIV-1 envelope glycoproteins lyse most primary CD4+ T lymphocytes as single cells, through a membrane fusion-dependent process (40). The formation of intracellular envelope glycoprotein-receptor complexes in the Golgi apparatus apparently initiates membrane fusion events that compromise the integrity of the cell membrane (6, 27).

The contribution of the death of uninfected cells to CD4+ T-lymphocyte depletion in SHIV-infected monkeys is uncertain (32). If the death of uninfected cells contributes in a quantitatively significant way to CD4+ T-cell decline in this model, our results suggest that most of this death must depend upon proximity to virus-producing cells or fusogenic virions. Assuming that viral proteins would be secreted from virus-producing cells in proportion to virions, they are less likely to contribute significantly to the observed differences in the CD4+ T-cell-depleting ability of SHIV-89.6 and SHIV-KB9. Further studies are needed to clarify whether the death of uninfected cells or pathogenic processes other than viral membrane fusion contribute to the loss of CD4+ T lymphocytes in SHIV-infected monkeys.

SHIV-infected monkeys resemble HIV-1-infected humans with respect to the relatedness of the infecting viruses, the evolutionary proximity of the host species, the patterns and levels of virus replication, the abnormalities of T-cell subsets that accompany infection, and the eventual disease manifestations (24, 28–32, 44, 47, 60, 61, 64). Studies of viral replication and T-cell turnover in HIV-1-infected individuals (26, 74) are consistent with the possibility that viral cytopathic effects contribute to CD4+ T-lymphocyte decline. SHIV-KB9 resembles the highly cytopathic primary HIV-1 isolates that typically emerge later in infection and that can utilize a broader range of chemokine receptors (9, 11, 32, 36, 72, 73), thereby placing a greater proportion of CD4+ T lymphocytes at risk of destruction (5). These similarities make it likely that envelope glycoprotein-mediated membrane fusion contributes to HIV-1 immunopathogenesis in humans. Intervention strategies targeting the fusogenic function of the HIV-1 envelope glycoproteins might therefore dually impact virus replication and CD4+ T-cell destruction.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Sheri Farnum and Yvette McLaughlin for manuscript preparation.

This work was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health (no. AI33832 and Center for AIDS Research Award no. AI28691) and the European Commission and by the G. Harold and Leila Mathers Foundation, the Friends 10, the late William F. McCarty-Cooper, and Douglas and Judith Krupp.

REFERENCES

- 1.Baba T, Liska V, Kimani A, Ray N, Dailey P, Penninck D, Bronson R, Greene M, McClure H, Martin L, Ruprecht R. Live attenuated, multiply deleted simian immunodeficiency virus causes AIDS in infant and adult macaques. Nat Med. 1999;5:194–203. doi: 10.1038/5557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barouch D H, Santra S, Schmitz J E, Kuroda J J, Fu T M, Wagner W, Bilska M, Craiu A, Zheng X X, Krivulka G R, Beaudry K, Lifton M A, Nickerson C E, Trigona W L, Punt K, Freed D C, Guan L, Dubey S, Casimiro D, Simon A, Davies M E, Chastain M, Strom T B, Gelman R S, Montefiori D C, Lewis M G, Shiver J, Letvin N. Control of viremia and prevention of clinical AIDS in rhesus monkeys by cytokine-augmented DNA vaccination. Science. 2000;290:486–492. doi: 10.1126/science.290.5491.486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Barre-Sinoussi F, Chermann J C, Rey F, Nugeyre M T, Chamaret S, Gruest J, Dauguet C, Axler-Blin C, Vezinet-Brun F, Rouzioux C, Rozenbaum W, Montagnier L. Isolation of a T-lymphotropic retrovirus from a patient at risk for acquired immune deficiency syndrome (AIDS) Science. 1983;220:868–871. doi: 10.1126/science.6189183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bartz S R, Emerman M. Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 Tat induces apoptosis and increases sensitivity to apoptotic signals by up-regulating FLICE/caspase-8. J Virol. 1999;73:1956–1963. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.3.1956-1963.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bleul C C, Wu L, Hoxie J A, Springer T A, Mackay C R. The HIV coreceptors CXCR4 and CCR5 are differentially expressed and regulated on human T lymphocytes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:1925–1930. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.5.1925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cao J, Park I W, Cooper A, Sodroski J. Molecular determinants of acute single-cell lysis by human immunodeficiency virus type 1. J Virol. 1996;70:1340–1354. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.3.1340-1354.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chakrabarti L, Cumont M C, Montagnier L, Hurtrel B. Variable course of primary simian immunodeficiency virus infection in lymph nodes: relation to disease progression. J Virol. 1994;68:6634–6642. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.10.6634-6643.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chan D C, Fass D, Berger J M, Kim P S. Core structure of gp41 from the HIV envelope glycoprotein. Cell. 1997;89:263–273. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80205-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cheng-Mayer C, Seto D, Tateno M, Levy J A. Biologic features of HIV-1 that correlate with virulence in the host. Science. 1988;240:80–82. doi: 10.1126/science.2832945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Clavel F. HIV-2, the West African AIDS virus. AIDS. 1987;1:135–140. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Connor R I, Sheridan K E, Ceradini D, Choe S, Landau N. Change in coreceptor use correlates with disease progression in HIV-1-infected individuals. J Exp Med. 1997;185:621–628. doi: 10.1084/jem.185.4.621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dedera D, Ratner L. Demonstration of two distinct cytopathic effects with syncytium formation-defective human deficiency virus type 1 mutants. J Virol. 1991;65:6129–6139. doi: 10.1128/jvi.65.11.6129-6136.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Desrosiers R C. The simian immunodeficiency viruses. Annu Rev Immunol. 1990;8:557–578. doi: 10.1146/annurev.iy.08.040190.003013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Desrosiers R C, Lifson J, Gibbs J, Czajak S, Howe A, Arthur L, Johnson R P. Identification of highly attenuated mutants of simian immunodeficiency virus. J Virol. 1998;72:1431–1437. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.2.1431-1437.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Eternad-Moghadam B, Sun Y, Nicholson E K, Fernandes M, Liou K, Lee J, Sodroski J. Envelope glycoprotein determinants of increased fusogenicity in a pathogenic simian-human immunodeficiency virus (SHIV-KB9) passaged in vivo. J Virol. 2000;74:4433–4440. doi: 10.1128/jvi.74.9.4433-4440.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fauci A S. The human immunodeficiency virus: infectivity and mechanisms of pathogenesis. Science. 1988;239:617–622. doi: 10.1126/science.3277274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fauci A S, Macher A M, Longo D L, Lane H C, Rook A H, Masur H, Gelmann E P. NIH conference. Acquired immunodeficiency syndrome: epidemiologic, clinical, immunologic, and therapeutic considerations. Ann Intern Med. 1984;100:92–106. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-100-1-92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Finkel T, Tudor-Williams G, Banda N, Cotton M, Curriel T, Monks C, Baba T, Ruprecht R, Kuppler A. Apoptosis occurs predominantly in bystander cells and not in productively infected cells of HIV- and SIV-infected lymph nodes. Nat Med. 1995;1:129–134. doi: 10.1038/nm0295-129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gallo R C, Salahuddin S Z, Popovic M, Shearer G M, Kaplan M, Haynes B F, Palker T J, Redfield R, Oleske J, Safai B, White G, Foster P, Markham P D. Frequent detection and isolation of cytopathic retroviruses (HTLV-III) from patients with AIDS and at risk for AIDS. Science. 1984;224:500–503. doi: 10.1126/science.6200936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gibbs J, Lackner A, Lang S, Simon M, Sehgal P, Daniel M, Desrosiers R. Progression to AIDS in the absence of a gene for vpr or vpx. J Virol. 1995;69:2378–2383. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.4.2378-2383.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gougeon M L, Garcia S, Henney J, Tscfhopp R, Lecoeur H, Guetard D, Rame V, Dauguet C, Montagnier L. Programmed cell death in AIDS-related HIV and SIV infections. AIDS Res Hum Retrovir. 1993;9:553–563. doi: 10.1089/aid.1993.9.553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Groux H, Torpier G, Monte D, Mouton Y, Capron A, Amieson J C. Activation-induced death by apoptosis in CD4+ T cells from human immunodeficiency virus-infected asymptomatic individuals. J Exp Med. 1992;175:331–340. doi: 10.1084/jem.175.2.331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hamilton L. Regression with graphics: a second course in applied statistics. Belmont, Calif: Duxbury Press; 1992. p. 41. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Harouse J M, Gettie A, Tan R C, Blanchard J, Cheng-Mayer C. Distinct pathogenic sequela in rhesus macaques infected with CCR5 or CXCR4 utilizing SHIVs. Science. 1999;284:816–819. doi: 10.1126/science.284.5415.816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ho D D, Neumann A U, Perelson A, Chen W, Leonard J M, Markowitz M. Rapid turnover of plasma virions and CD4 lymphocytes in HIV-1 infection. Nature. 1995;373:123–126. doi: 10.1038/373123a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hoch J, Lang S M, Weeger M, Stahl-Hennig C, Coulibaly C, Dittmer U, Hunsmann G, Fuchs D, Muller J, Sopper S, Fleckenstein B, Uberla K T. vpr deletion mutant of simian immunodeficiency virus induces AIDS in rhesus monkeys. J Virol. 1995;69:4807–4813. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.8.4807-4813.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hoxie J A, Alpers J D, Rackowski J, Huebner K, Haggarty B, Cedarbaum A, Reed J C. Alterations in T4 (CD4) protein and mRNA synthesis in cells infected with HIV. Science. 1986;234:1123–1127. doi: 10.1126/science.3095925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Igarashi T, Shibata R, Hasebe F, Ami Y, Shinohara K, Komatsu T, Stahl-Hennig C, Petry H, Hunsmann G, Kuwata T, Jin M, Adachi A, Kurimura T, Okada M, Miura T, Hayami M. Persistent infection with SIVmac chimeric virus having tat, rev, vpu, env and nef of HIV type 1 in macaque monkeys. AIDS Res Hum Retrovir. 1994;10:1021–1029. doi: 10.1089/aid.1994.10.1021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Joag S V, Li Z, Foresman L, Stephens E B, Zhao L, Adany I, Pinson D M, McClure H M, Narayan O. Chimeric simian/human immunodeficiency virus that causes progressive loss of CD4+ T cells and AIDS in pig-tailed macaques. J Virol. 1996;70:3189–3197. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.5.3189-3197.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Joag S V, Li Z, Foresman L, Pinson D M, Raghavan R, Zhuge W, Adany I, Wang C, Jia F, Sheffer D, Ranchalis I, Watson A, Narayan O. Characterization of the pathogenic KU-SHIV model of acquired immunodeficiency syndrome in macaques. AIDS Res Hum Retrovir. 1997;13:635–645. doi: 10.1089/aid.1997.13.635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Karisson G B, Halloran M, Li J, Park I-W, Gomila R, Reimann K, Axthelm M K, Iliff S A, Letvin N L, Sodroski J. Characterization of molecularly cloned simian-human immunodeficiency viruses causing rapid CD4+ lymphocyte depletion in rhesus monkeys. J Virol. 1997;71:4218–4225. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.6.4218-4225.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Karlsson G B, Halloran M, Schenten D, Lee J, Racz P, Tenner-Racz K, Manola J, Gelman R, Etemad-Moghadam B, Desjardins E, Wyatt R, Gerard N P, Marcon L, Margolin D, Fanton J, Axthelm M K, Letvin N L, Sodroski J. The envelope glycoprotein ectodomains determine the efficiency of CD4+ T lymphocyte depletion in simian-human immunodeficiency virus-infected macaques. J Exp Med. 1998;188:1159–1171. doi: 10.1084/jem.188.6.1159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kleinbaum D G, Kupper L L, Muller K E. Applied regression analysis and other multivariable methods. 2nd ed. Belmont, Calif: Duxbury Press; 1988. pp. 126–131. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Koga Y, Sasaki M, Nakamura K, Kimura G, Nornoto K. Intracellular distribution of the envelope glycoprotein of human immunodeficiency virus and its role in the production of cytopathic effect in CD4+ and CD4− human cell lines. J Virol. 1990;64:4661–4671. doi: 10.1128/jvi.64.10.4661-4671.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Konvalinka J, Litterst M, Welker R, Kottler H, Rippmann F, Heuser A, Krausslich H. An active-site mutation in the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 proteinase (PR) causes reduced PR activity and loss of PR-mediated cytotoxicity without apparent effect on virus maturation and infectivity. J Virol. 1995;69:7180–7186. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.11.7180-7186.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Koot M, Vos A H, Keet R P, de Goede R E, Dercksen M W, Terpstra F G, Coutinho R A, Miedema F, Tersmette M. HIV-1 biological phenotype in long-term infected individuals evaluated with an MT-2 cocultivation assay. AIDS. 1992;6:49–54. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199201000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Korber B T, Foley B, Kuiken C, Pillai S, Sodroski J G. Numbering position in HIV relative to HXB2. Human retroviruses and AIDS. A compilation and analysis of nucleic acid and amino acid sequences. Los Alamos, N.Mex: Los Alamos National Laboratories; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kowalski M, Bergeron L, Dorfman T, Haseltine W, Sodroski J. Attenuation of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 cytopathic effect by a mutation affecting the transmembrane envelope glycoprotein. J Virol. 1991;65:281–291. doi: 10.1128/jvi.65.1.281-291.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kwong P D, Wyatt R, Robinson J, Sweet R W, Sodroski J, Hendrickson W A. Structure of an HIV gp120 envelope glycoprotein in complex with the CD4 receptor and a neutralizing human antibody. Nature. 1998;393:648–659. doi: 10.1038/31405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.LaBonte J, Patel T, Hofmann W, Sodroski J. Importance of membrane fusion mediated by the human immunodeficiency virus envelope glycoproteins for lysis of primary CD4-positive T cells. J Virol. 2000;74:10690–10698. doi: 10.1128/jvi.74.22.10690-10698.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Letvin N L, Daniel M D, Sehgal P K, Desrosiers R C, Hunt R D, Waldron L M, MacKey J J, Schmidt D K, Chalifoux L V, King N W. Induction of AIDS-like disease in macaque monkeys with T-cell tropic retrovirus STLV-III. Science. 1985;230:71–73. doi: 10.1126/science.2412295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lewin-Smith M, Wahl S, Orenstein J. Human immunodeficiency virus-rich multinucleated giant cells in the colon: a case report with transmission electron microscopy, immunohistochemistry, and in situ hybridization. Mod Pathol. 1999;12:75–81. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Li C, Friedman D, Wang C, Metelev V, Pardee A. Induction of apoptosis in uninfected lymphocytes by HIV-1 Tat protein. Science. 1995;268:429–431. doi: 10.1126/science.7716549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Li J, Lord C I, Haseltine W, Letvin N L, Sodroski J. Infection of cynomolgus monkeys with a chimeric HIV-1/SIVmac virus that expresses the HIV-1 envelope glycoproteins. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 1992;5:639–646. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lifson J D, Feinberg M B, Reyes G R, Rabin L, Banapour B, Chakrabarti S, Moss B, Wong-Staal F, Steimer K S, Engelman E G. Induction of CD4-dependent cell fusion by the HTLV-III/LAV glycoprotein. Nature. 1986;323:725–728. doi: 10.1038/323725a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lifson J D, Nowak M A, Goldstein S, Rossio J L, Kinter A, Vasquez G, Wiltrout T A, Brown C, Schneider D, Wahl L, Lloyd A L, Williams J, Elkins W R, Fauci A S, Hirsch V M. The extent of early viral replication is a critical determinant of the natural history of simian immunodeficiency virus infection. J Virol. 1997;71:9508–9514. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.12.9508-9514.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Luciw P A, Pratt-Lowe E, Shaw K E, Levy J A, Cheng-Mayer C. Persistent infection of rhesus macaques with T-cell-line-tropic and macrophage-tropic clones of simian/human immunodeficiency viruses (SHIV) Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:7490–7494. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.16.7490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.McCloskey T W, Ott M, Tribble E, Khan S A, Teichberg S, Paul M O, Pahwa S, Verdin E, Chirmule N. Dual role of HIV Tat in regulation of apoptosis in T cells. J Immunol. 1997;158:1014–1019. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Mellors J W, Rinaldo C, Gupta P, White R, Todd J, Kingsley L A. Prognosis in HIV-1 infection predicted by the quantity of virus in plasma. Science. 1996;272:1167–1170. doi: 10.1126/science.272.5265.1167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Meyaard L, Otto S A, Jonker R R, Mijnster M J, Keet R P, Miedema F. Programmed death of T cells in HIV-1 infection. Science. 1992;257:217–219. doi: 10.1126/science.1352911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Moore J P, Trkola A, Dragic T. Co-receptors for HIV-1 entry. Curr Opin Immunol. 1997;9:551–562. doi: 10.1016/s0952-7915(97)80110-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Muro-Cacho C A, Pantaleo G, Fauci A S. Analysis of apoptosis in lymph nodes of HIV-infected persons. Intensity of apoptosis correlates with the general state of activation of the lymphoid tissue and not with stage of disease or viral burden. J Immunol. 1995;154:5555–5566. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.National Institutes of Health. Guide for the care and use of laboratory animals, rev. ed. Department of Health and Human Services publication no. (NIH) 85-23. Bethesda, Md: National Institutes of Health; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Okada H, Takei R, Tashiro M. Nef protein of HIV-1 induces apoptotic cytolysis of murine lymphoid cells independently of CD95 (Fas) and its suppression serine/threonine protein kinase inhibitors. FEBS Lett. 1997;417:61–64. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(97)01255-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Pantaleo G, Graziosi C, Demarest J F, Cohen O J, Vaccarezza M, Gantt K, Muro-Cacho C, Fauci A S. Role of lymphoid organs in the pathogenesis of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection. Immunol Rev. 1994;140:105–130. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065x.1994.tb00867.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Purvis S, Jacobberger J, Sramkoski M, Patki A, Lederman M. HIV type 1 Tat protein induces apoptosis and death in Jurkat cells. AIDS Res Hum Retrovir. 1995;4:443–450. doi: 10.1089/aid.1995.11.443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Racz P, Tenner-Racz K, van Vloten F, Schmidt H, Dietrich M, Gluckman J C, Letvin N, Janossy G. Lymphatic tissue changes in AIDS and other retrovirus infections: tools and insights. Lymphology. 1990;23:85–91. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Reimann K A, Tenner-Racz K, Racz P, Montefiori D, Yasutomi Y, Lin W, Ransil B, Letvin N. Immunopathogenic events in acute infection of rhesus monkeys with simian immunodeficiency virus of macaques. J Virol. 1994;68:2362–2370. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.4.2362-2370.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Reimann K A, Waite B C, Lee-Parritz D E, Lin W, Uchanska-Ziegler B, O'Connell M J, Letvin N L. Use of human leukocyte-specific monoclonal antibodies for clinically immunophenotyping lymphocytes of rhesus monkeys. Cytometry. 1994;17:102–108. doi: 10.1002/cyto.990170113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Reimann K A, Li J, Voss G, Lekutis C, Tenner-Racz K, Racz P, Lin W, Montefiori D, Lee-Parritz D, Collman R, Sodroski J, Letvin N. An env gene derived from a primary HIV-1 isolate confers high in vivo replicative capacity to a chimeric simian/human immunodeficiency virus in rhesus monkeys. J Virol. 1996;70:3198–3206. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.5.3198-3206.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Reimann K A, Li J T, Veazey R, Halloran M, Park I-W, Karlsson G B, Sodroski J, Letvin N L. A chimeric simian/human immunodeficiency virus expressing a primary patient human immunodeficiency virus type 1 isolate env causes an AIDS-like disease after in vivo passage in rhesus monkeys. J Virol. 1996;70:6922–6928. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.10.6922-6928.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Reimann K A, Watson A, Dailey P J, Lin W, Lord C I, Steenbeke T D, Parker R A, Axthelm M K, Karlsson G B. Viral burden and disease progression in rhesus monkeys infected with chimeric simian-human immunodeficiency viruses. Virology. 1999;256:15–21. doi: 10.1006/viro.1999.9632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Ruprecht R M, Baba T, Rasmussen R, Hu Y, Sharma P. Murine and simian retrovirus models: the threshold hypothesis. AIDS. 1996;10:S33–S40. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199601001-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Shibata R, Maldarelli F, Siemon C, Matano T, Parta M, Miller G, Frederickson T, Martin M A. Infection and pathogenicity of chimeric simian-human immunodeficiency viruses in macaques: determinants of high virus loads and CD4 cell killing. J Infect Dis. 1997;176:362–373. doi: 10.1086/514053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Sodroski J, Goh W C, Rosen C, Campbell K, Haseltine W A. Role of the HTLV-III/LAV envelope in syncytium formation and cytopathicity. Nature. 1986;322:470–474. doi: 10.1038/322470a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Somasundaran M, Robinson H. A major mechanism of human immunodeficiency virus-induced cell killing does not involve cell fusion. J Virol. 1987;61:3114–3119. doi: 10.1128/jvi.61.10.3114-3119.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Stata Corporation. Stata reference manual, release 5. College Station, Tex: Stata Corporation; 1987. pp. 574–584. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Stevenson M, Meier C, Mann A M, Chapman N, Wasiak A. Envelope glycoprotein of HIV induces interference and cytolysis resistance in CD4+ cells: mechanism for persistence in AIDS. Cell. 1988;53:483–496. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(88)90168-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Stewart S A, Poon B, Song J Y, Chen I S Y. Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 Vpr induces apoptosis through caspase activation. J Virol. 2000;74:3105–3111. doi: 10.1128/jvi.74.7.3105-3111.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Tan K, Liu J, Wang J, Shen S, Lu M. Atomic structure of a thermostable subdomain of HIV-1 gp41. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:12303–12308. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.23.12303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Tenner-Racz K, Stellbrink H-J, van Lunzen J, Schneider C, Jacobs H-P, Raschdorff B, Großschupff G, Steinman R M, Racz P. The unenlarged lymph nodes of HIV-1-infected, asymptomatic patients with high CD4 T cell counts are sites for virus replication and CD4 T cell proliferation. The impact of highly active antiretroviral therapy. J Exp Med. 1998;187:949–959. doi: 10.1084/jem.187.6.949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Tersmette M, Gruters R A, de Wolf F, de Goede R E, Lange J M, Schellekens P T, Goudsmit J, Huisman H G, Miedema F. Evidence for a role of virulent human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) variants in the pathogenesis of acquired immunodeficiency syndrome: studies on sequential HIV isolates. J Virol. 1989;63:2118–2125. doi: 10.1128/jvi.63.5.2118-2125.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Tersmette M, Lange J M, de Goede R E, de Wolfe F, Eeftink-Schattenkerk J K, Schellekens P T, Coutinho R A, Huisman J G, Goudsmit J, Miedema F. Association between biological properties of human immunodeficiency virus variants and risk for AIDS and AIDS mortality. Lancet. 1989;i:983–985. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(89)92628-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Wei X, Ghosh S, Taylor M, Johnson V, Emini E, Deutsch P, Lifson J, Bonhoeffer S, Nowak M, Hahn B, Saag M, Shaw G. Viral dynamics in human immunodeficiency virus type 1 infection. Nature. 1995;373:117–122. doi: 10.1038/373117a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Weissenhorn W, Dessen A, Harrison S C, Skehel J J, Wiley D C. Atomic structure of the ectodomain from HIV-1 gp41. Nature. 1997;387:426–430. doi: 10.1038/387426a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Wong J K, Gunthard H F, Havlir D V, Zhang Z Q, Haase A T, Ignacio C C, Kwok S, Emini E, Richman D D. Reduction of HIV-1 in blood and lymph nodes following potent antiretroviral therapy and the virologic correlates of treatment failure. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:12574–12579. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.23.12574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Wyatt R, Sodroski J. The HIV-1 envelope glycoproteins: fusogens, antigens, and immunogens. Science. 1998;280:1884–1888. doi: 10.1126/science.280.5371.1884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Zauli G, Gibellini D, Milani D, Mazzoni M, Borgatti P, LaPlaca M, Capitani S. Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 Tat protein protects lymphoid, epithelial, and neuronal cell lines from death by apoptosis. Cancer Res. 1993;53:4481–4485. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]