Abstract

Klebsiella pneumoniae is a pathogen that commonly causes hospital-acquired infections. Bacterial biofilms are structured bacterial communities that adhere to the surface of objects or biological tissues. In this study, we investigated the genome homology and biofilm formation capacity of ESBL-producing K. pneumoniae. Thirty ESBL-producing K. pneumoniae isolates from 25 inpatients at Ruijin Hospital, Shanghai, were subjected to pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE) to estimate genomic relatedness. Based on the chromosomal DNA patterns we obtained, we identified 21 PFGE profiles from the 30 isolates, eight of which had high homology indicating that they may have genetic relationships and/or potential clonal advantages within the hospital. Approximately 84% (21/25) of the clinical patients had a history of surgery, urinary tract catheterization, and/or arteriovenous intubation, all of which may have increased the risk for nosocomial infections. Biofilms were observed in 73% (22/30) of the isolates and that strains did not express type 3 fimbriae did not have biofilm formation capacity. Above findings indicated that a high percentage of ESBL-producing K. pneumoniae isolates formed biofilms in vitro and even though two strains with cut-off of PFGE reached 100% similarity, they generated biofilms differently. Besides, the variability in biofilm formation ability may be correlated with the expression of type 3 fimbriae. Thus, we next screened four ESBL-producing K. pneumoniae isolates (Kpn5, Kpn7, Kpn11, and Kpn16) with high homology and significant differences in biofilm formation using PFGE molecular typing, colony morphology, and crystal violet tests. Kpn7 and Kpn16 had stronger biofilm formation abilities compared with Kpn5 and Kpn11. The ability of above four ESBL-producing K. pneumoniae isolates to agglutinate in a mannose-resistant manner or in a mannose-sensitive manner, as well as RNA sequencing-based transcriptome results, showed that type 3 fimbriae play a significant role in biofilm formation. In contrast, type 1 fimbriae were downregulated during biofilm formation. Further research is needed to fully understand the regulatory mechanisms which underlie these processes.

1. Introduction

K. pneumoniae is a Gram-negative opportunistic pathogen that is widespread in clinical and nonclinical settings [1]. Clinically, ESBL-producing K. pneumoniae mainly causes nosocomial infections in hospitalized patients, including respiratory, urinary tract, blood, and wound infections [2, 3]. Additionally, antibiotic resistance in K. pneumoniae and other bacterial pathogens continues to be a growing public health concern. ESBL-producing K. pneumoniae are increasingly common and are difficult to treat. The extracellular matrices that makeup biofilms can trap antibiotics and prevent them from reaching bacterial cells. Additionally, bacteria have slowed metabolic rates within the biofilms, which makes them less susceptible to antibiotics that target rapidly dividing cells [4]. Biofilm formation increases bacterial density and provides favorable conditions for horizontal gene transfer, which allows for more frequent transmission of resistance genes between different bacterial species [5]. Medical devices are another important driver of bacterial infection, as they are susceptible to bacterial contamination both before and after implantation and can be growth surfaces for biofilms [6–9]. Thus, studying the mechanisms underlying ESBL-producing K. pneumoniae biofilm formation is of critical importance.

Biofilm formation in K. pneumoniae appears to be influenced by a variety of factors, including fimbriae formation, polysaccharides, and environmental conditions. Most K. pneumoniae produce type 1 and type 3 fimbriae. Type 1 fimbriae are short, hair-like structures that play a role in host tissue adhesion. Type 3 fimbriae, in contrast, are longer and more flexible, and are strongly associated with biofilm formation and bacterial aggregation. Type 1 fimbriae are encoded by the fim gene cluster, with the fimA gene encoding the major subunit and the fimH gene encoding the adduct located at the tip of fimbriae [10]. Type 1 fimbriae expression is associated with refractory urinary tract infections. Type 3 fimbriae are encoded by the mrkABCDF operon and mediate biofilm formation both in vitro and in vivo [11]. These fimbriae originate from the grana on the internal side of the bacterial membrane. Additionally, K. pneumoniae membrane protein integrity expression plays a crucial role in fimbriae structural stability, but the specific proteins and regulatory targets need to be further explored. The aim of this study is to evaluate the biofilm formation abilities of ESBL-producing K. pneumoniae isolates. Our findings may promote a more in-depth understanding of the regulatory process underlying fimbriae expression and thus lay the foundation for the therapeutic prevention of biofilm formation.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Bacterial Cultures

Thirty ESBL-producing K. pneumoniae isolates used in this study were provided by the Department of Infectious Diseases, North Campus of Ruijin Hospital, Shanghai during 2020-2021. All strains were identified and analyzed by VITEK2 Compact system (bioMérieux VITEK, USA). For bacterial cultures, 25 μL of clinically isolated ESBL-producing K.pneumoniae glycerol stocks were inoculated into 5 mL Luria–Bertani (LB) broth and cultured overnight in a shaking incubator at 37°C and 200 rpm to the middle exponential phase (OD600 ≈ 1.0). Cultures were then finished, collected and reserved for the next experiment.

2.2. Antibiotic Susceptibility Testing

All strains were identified and analyzed by the VITEK2 Compact system (bioMérieux VITEK, USA) and drug susceptibility analysis system. The production of strain β-lactamase (ESBL) was tested by broth microdilution method. The specific drugs are as follows: cefepime (CPM), ceftazidime (CAZ), cefotaxime (CTX), aztreonam (AZT), ciprofloxacin (CIP), ampicillin-sulbactam (AMS), imipenem (IMI), meropenem (MEM) and piperacillin-tazobactam (PTZ), sulfamethoxazole (SXT), gentamycin (GEN), and levofloxacin (LEF). Specific operational details and result interpretation were conducted according to CLSI 2019 relevant standards [12].

2.3. Pulsed-Field Gel Electrophoresis (PFGE)

Our ESBL-producing K. pneumoniae strains were isolated and purified on Columbia blood plates and then prepared into a bacterial suspension with a turbidity of 0.48–0.52 using CSB (100 mM Tris, 100 mM EDTA, pH 8.0). The chromosomes of the 30 ESBL-producing K. pneumoniae isolates were digested with the restriction enzyme XbaI and electrophoresis was performed on the CHEF Mapper XA System (Bio-Rad). When completed, gels were stained with Gelred (Biotium) to display characteristic patterns under the Gel Doc UV light (Bio-Rad). The maps of PFGE were analyzed using Bionumerics 6.0 software and calculated by the Dice coefficients. The dendrogram was performed through the unweighted-pair group method with average linkages (UPGMA) [13].

2.4. Evaluation of Biofilm Formation Ability

We employed two methods: crystal violet stains and the rugose colony morphology assay to evaluate ESBL-producing K. pneumoniae isolate biofilm formation [14]. For crystal violet stained biofilms, we completed routine bacterial cultures and cultures were separately diluted (1 : 100) in 200 μL LB medium in 96-well cell culture plate for 48 h. After incubation, the planktonic bacteria were moved and each aperture was washed three times and incubated at 60°C for 20 min to fix the biofilms. The apertures were then stained with 0.1% crystal violet for 20 min. The relative quantity of biofilm formation was represented by OD570/OD600 values. For the rugose colony morphology assay, 2 μL of glycerol stocks were spotted onto LB plates, which were dried at 37°C for 24−48 h and then equilibrated at room temperature for 2 h. After bacterial plaque maturation, colony surfaces either showed visible biofilm folds or did not, allowing for analysis of differences in biofilm fold formation capabilities among different strains. Paired Student's t-test was performed to determine statistically significant differences and the OD570/OD600 values were calculated to indicate the relative biofilm formation. P ≤ 0.01 was considered to indicate statistical significance.

2.5. Hydrogenated Sheep Red Blood Cell and Guinea Pig Red Blood Cell Agglutination Assays

After routine bacterial cultures and cultures were separated 100 μL of the four experimental strains to 24-well plate covers and then added 50 μL of 6% hydrolyzed sheep erythrocytes and 50 μL of 5% D-mannose solution.

100 μL of PBS solution was used as a negative control. We also completed identical experiments where 6% hydroformylation sheep erythrocytes were substituted with 6% guinea pig erythrocytes. For bacterial agglutination assays, the representative data from at least three independent biological replicates were shown. For bacterial erythrocyte agglutination titer ratio, Paired Student's t-test was performed to determine statistically significant differences and P ≤ 0.01 was considered to indicate statistical significance.

2.6. RNA Extraction and RNA-Seq

We cultured ESBL-producing K. pneumoniae through routine way. After incubation, we added RNA protectant (RNaseZap) to bacterial cultures, and then concentrated these bacterial broths using centrifugation. Total RNA was extracted following the PureLink™ RNA Mini Kit (Thermo Scientific) experimental protocols. RNA quantity and concentration were determined using NanoDrop 2000 spectrophotometry (Thermo Scientific). Finally, total RNA results were used to construct a cDNA library, and high-throughput sequencing was performed as previously described. The Fragments per Kilobase per Million (FPKM) value was used to measure the amount of ESBL-producing K. pneumoniae single gene transcripts and to calculate the relative differences in gene expression between different strains.

2.7. Quantitative RT-PCR (qRT-PCR)

Real-time quantitative PCR refers to the real-time analysis and detection of cumulative amplified PCR products during the reaction. To verify the differentially expressed genes suggested by RNA-seq, we used qRT-PCR on the Light Cycler 480 II (Roche, USA), with 16 S rRNA as the internal standard to standardize the expression of all sRNA candidates (Table 1). The primer we drew the 16 S rRNA gene relative standard curve, calculated the relative template quantity of the genes, and analyzed the results.

Table 1.

Primers for the target genes used in qRT-PCR.

| Gene name | Primers (5'-3') |

|---|---|

| KPHS_43560 | CTGGCCGGTAATCATTGGAAC/GAAAGGGATTGGGTTGCTGTC |

| KPHS_43590 | TTCTCGATCAGCAGCAGTCC/TGAAATTCCAGGGTGAATGTCG |

| KPHS_43550 | GATTGTTGTGTCAGCCCTGTC/GCCGCATTAACGACTTCTCC |

| KPHS_43440 | CAACATTAGCACCTCGTTCTCC/TGTAGCGGGTCTCCTGATTATTC |

| KPHS_43430 | CGACTAACGATAATAATACTCTGGATAAG/ACATAGCCAACGTAATAGGTGAAC |

| KPHS_43470 | CGGCAGCAGCGGATACTTAC/CTTCGGTGTTCGCCAGGTAG |

| KPHS_43460 | GCCGTTCTACATTACCGTCAG/GCCACTTTCACTGCGACATC |

| KPHS_43500 | TATTACCCGCCTGCCCAATC/TTCACCGTCACTGAGTCCTG |

| 16 s | GAGCGGCGGACGGGTGAGTA/GGGCACATCTGATGGCATGA |

2.8. Statistical Analysis

For all quantity bacterial assays, the representative data were from at least three independent biological replicates. The data were analyzed with SPSS 20.0 and Paired Student's t-test was performed to determine statistically significant differences and P ≤ 0.01 was considered to indicate statistical significance.

3. Results

3.1. Clinical Characteristics of ESBL-Producing K. pneumoniae Isolates in This Study

In this study, 30 clinical ESBL-producing K. pneumoniae isolates were collected from 25 patients aged an average of 62 years. The average duration of hospitalization for the patients was 42 days. Approximately 84% (21/25) of these patients had a history of surgery, urinary tract catheterization, and/or arteriovenous intubation, all of which were risk factors for nosocomial infections such as K. pneumoniae (Table 2). Besides, the strains in this study were multiple resistant bacteria which were simultaneously insensitive to at least 10 antimicrobial drugs (Table 3).

Table 2.

Characteristics of 30 antibiotic-resistant K. pneumoniae isolates.

| Strain Id | Sex/Age | Inpatient ward | Sample type | Length of hospital stay (days) | Risk factors | Biofilm formation | Type 3 fimbriae |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kpn1 | Man/81 | ICU | Sputum | 102 | Urinary intubation/respirator | YES | ± |

| Kpn2 | Man/39 | ICU | Sputum | 21 | Urinary intubation/arteriovenous cannula/respirator | YES | ± |

| Kpn3 | Man/56 | ICU | Catheter | 50 | Arteriovenous cannula | YES | +++ |

| Kpn4 | Femal/63 | ICU | Sputum | 50 | None | YES | ++ |

| Kpn5 | Femal/55 | Pulmonology | Urine | 13 | None | NO | — |

| Kpn6 | Femal/69 | ICU | Sputum | 23 | Urinary intubation/arteriovenous cannula/respirator | YES | ± |

| Kpn7 | Femal/45 | Pulmonology | Urine | 19 | ICU | YES | +++ |

| Kpn11 | Man/30 | ICU | Blood | 28 | Urinary intubation/arteriovenous cannula/respirator | NO | — |

| Kpn12 | Man/65 | ICU | Secretion | 70 | Surgery/urinary intubation/arteriovenous cannula/respirator | YES | + |

| Kpn13 | Man/44 | ICU | Bile | 62 | Surgery/urinary intubation/arteriovenous cannula/respirator | YES | + |

| Kpn14 | Man/65 | ICU | Bile | 70 | Surgery/urinary intubation/arteriovenous cannula/respirator | YES | + |

| Kpn15 | Man/65 | ICU | Blood | 70 | Urinary intubation/arteriovenous cannula/respirator | YES | + |

| Kpn16 | Man/79 | ICU | Secretion | 52 | Urinary intubation/arteriovenous cannula/respirator | YES | +++ |

| Kpn21 | Man/72 | Emergency department | Urine | 16 | Urinary intubation/arteriovenous cannula/respirator | NO | — |

| Kpn22 | Femal/63 | ICU | Urine | 50 | Urinary intubation/arteriovenous cannula | YES | ± |

| Kpn23 | Man/60 | Neurosurgery | Sputum | 22 | Urinary intubation/arteriovenous cannula/respirator | YES | +++ |

| Kpn24 | Femal/56 | Neurosurgery | Sputum | 21 | Urinary intubation/arteriovenous cannula/respirator | YES | ± |

| Kpn25 | Man/61 | Neurosurgery | Secretion | 14 | Surgery/urinary intubation/arteriovenous cannula/respirator | NO | — |

| Kpn31 | Man/64 | Hematology ward | Sputum | 19 | None | YES | ± |

| Kpn32 | Man/71 | Orthopaedic | Secretion | 35 | Urinary intubation/arteriovenous cannula | YES | ± |

| Kpn33 | Man/71 | ICU | Sputum | 81 | Urinary intubation/arteriovenous cannula/respirator | YES | ± |

| Kpn34 | Man/71 | ICU | Secretion | 81 | Urinary intubation/arteriovenous cannula/respirator | YES | ± |

| Kpn35 | Man/34 | Emergency department | Secretion | 65 | Arteriovenous cannula | YES | + |

| Kpn36 | Femal/54 | ICU | Secretion | 17 | Urinary intubation | NO | — |

| Kpn41 | Man/76 | ICU | Sputum | 39 | Urinary intubation/arteriovenous cannula/respirator | NO | — |

| Kpn42 | Femal/51 | ICU | Urine | 43 | None | YES | + |

| Kpn43 | Man/39 | Pulmonology | Sputum | 42 | Arteriovenous cannula | YES | + |

| Kpn44 | Man/73 | Pulmonology | Sputum | 50 | Urinary intubation/arteriovenous cannula/respirator | NO | — |

| Kpn45 | Man/31 | ICU | Sputum | 19 | Urinary intubation/respirator | YES | ± |

| Kpn46 | Man/67 | Neurology | Sputum | 23 | None | NO | — |

Table 3.

Multidrug resistance spectrum of K. pneumoniae in this study.

| Strain Id | Drug resistance spectrum | Number of resistant species |

|---|---|---|

| Kpn1 | CPM-CAZ-CTX-AZM-CIP-AMS-MEM-SXT-GEN-LEV-PIP/SBT | 11 |

| Kpn2 | CPM-CAZ-CTX-AZM-CIP-AMS-MEM-GEN-LEV-PIP/SBT | 10 |

| Kpn3 | CPM-CAZ-CTX-AZM-CIP-AMS-IMI-MEM-SXT-GEN-LEV-PIP/SBT | 12 |

| Kpn4 | CPM-CAZ-CTX-AZM-CIP-AMS-IMI-MEM-SXT-GEN-LEV-PIP/SBT | 12 |

| Kpn5 | CPM-CAZ-CTX-AZM-CIP-AMS-IMI-MEM-SXT-GEN-LEV-PIP/SBT | 12 |

| Kpn6 | CPM-CAZ-CTX-AZM-CIP-AMS-IMI-MEM-SXT-GEN-LEV-PIP/SBT | 12 |

| Kpn7 | CPM-CAZ-CTX-AZM-CIP-AMS-IMI-MEM-SXT-GEN-LEV-PIP/SBT | 12 |

| Kpn11 | CPM-CAZ-CTX-AZM-CIP-AMS-IMI-MEM-SXT-GEN-LEV-PIP/SBT | 12 |

| Kpn12 | CPM-CAZ-CTX-AZM-CIP-AMS-IMI-MEM-SXT-GEN-LEV-PIP/SBT | 12 |

| Kpn13 | CPM-CAZ-CTX-AZM-CIP-AMS-IMI-MEM-SXT-GEN-LEV-PIP/SBT | 12 |

| Kpn14 | CPM-CAZ-CTX-AZM-CIP-AMS-IMI-MEM-SXT-GEN-LEV-PIP/SBT | 12 |

| Kpn15 | CPM-CAZ-CTX-AZM-CIP-AMS-IMI-MEM-SXT-GEN-LEV-PIP/SBT | 12 |

| Kpn16 | CPM-CAZ-CTX-AZM-CIP-AMS-IMI-MEM-SXT-GEN-LEV-PIP/SBT | 12 |

| Kpn21 | CPM-CAZ-CTX-AZM-CIP-AMS-IMI-MEM-SXT-GEN-LEV-PIP/SBT | 12 |

| Kpn22 | CPM-CAZ-CTX-AZM-CIP-AMS-IMI-MEM-SXT-GEN-LEV-PIP/SBT | 12 |

| Kpn23 | CPM-CAZ-CTX-AZM-CIP-AMS-IMI-MEM-LEV-PIP/SBT | 11 |

| Kpn24 | CPM-CAZ-CTX-AZM-CIP-AMS-IMI-MEM-SXT-GEN-LEV-PIP/SBT | 12 |

| Kpn25 | CPM-CAZ-CTX-AZM-CIP-AMS-IMI-MEM-SXT-GEN-LEV-PIP/SBT | 12 |

| Kpn31 | CPM-CAZ-CTX-AZM-CIP-AMS-IMI-MEM-SXT-GEN-LEV-PIP/SBT | 12 |

| Kpn32 | CPM-CAZ-CTX-AZM-CIP-AMS-IMI-MEM-SXT-GEN-LEV-PIP/SBT | 12 |

| Kpn33 | CPM-CAZ-CTX-AZM-CIP-AMS-IMI-MEM-SXT-LEV-PIP/SBT | 11 |

| Kpn34 | CPM-CAZ-CTX-AZM-CIP-AMS-IMI-MEM-SXT-LEV-PIP/SBT | 11 |

| Kpn35 | CPM-CAZ-CTX-AZM-CIP-AMS-IMI-MEM-SXT-GEN-LEV-PIP/SBT | 12 |

| Kpn36 | CPM-CAZ-CTX-AZM-CIP-AMS-IMI-MEM-SXT-GEN-LEV-PIP/SBT | 12 |

| Kpn41 | CPM-CAZ-CTX-AZM-CIP-AMS-IMI-MEM-SXT-LEV-PIP/SBT | 11 |

| Kpn42 | CPM-CAZ-CTX-AZM-CIP-AMS-IMI-MEM-SXT-GEN-LEV-PIP/SBT | 12 |

| Kpn43 | CPM-CAZ-CTX-AZM-CIP-AMS-IMI-MEM-SXT-GEN-LEV-PIP/SBT | 12 |

| Kpn44 | CPM-CAZ-CTX-AZM-CIP-AMS-IMI-MEM-SXT-GEN-LEV-PIP/SBT | 12 |

| Kpn45 | CPM-CAZ-CTX-AZM-CIP-AMS-IMI-MEM-SXT-GEN-LEV-PIP/SBT | 12 |

| Kpn46 | CPM-CAZ-CTX-AZM-CIP-AMS-IMI-MEM-SXT-GEN-LEV-PIP/SBT | 12 |

3.2. The Evaluation Biofilm Ability of ESBL-Producing K. pneumoniae Isolates

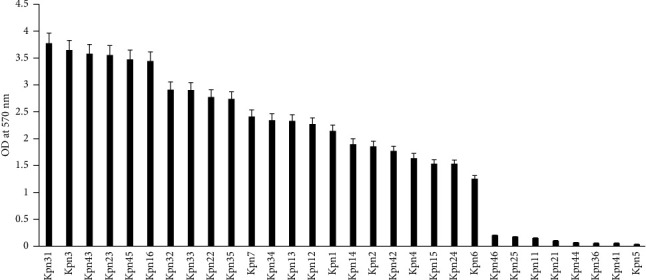

The classification of biofilm-producing strains was based on OD570 values. Strains with OD570 < 1 were considered to be non-biofilm formers, and strains with OD570 ≥ 1 were considered to be biofilm formers. Among the ESBL-producing K. pneumoniae isolates, 73% (22/30) formed biofilms (Figure 1). In addition, specific detection of type 3 fimbriae expression in ESBL-producing K. pneumoniae isolates via mannose-resistant agglutination of acid-sheep RBCs indicated that high percentages of ESBL-producing K. pneumoniae isolates formed biofilms in vitro, but that strains did not express type 3 fimbriae could not form biofilms.

Figure 1.

Biofilm formation in ESBL-producing K. pneumoniae strains. Biofilm formation by 30 ESBL-producing K. pneumoniae isolates was monitored with crystal violet staining and quantified with OD570 values. OD570 > 1 were classified as biofilm-forming strains, and OD570 < 1 were classified as nonbiofilm-forming strains.

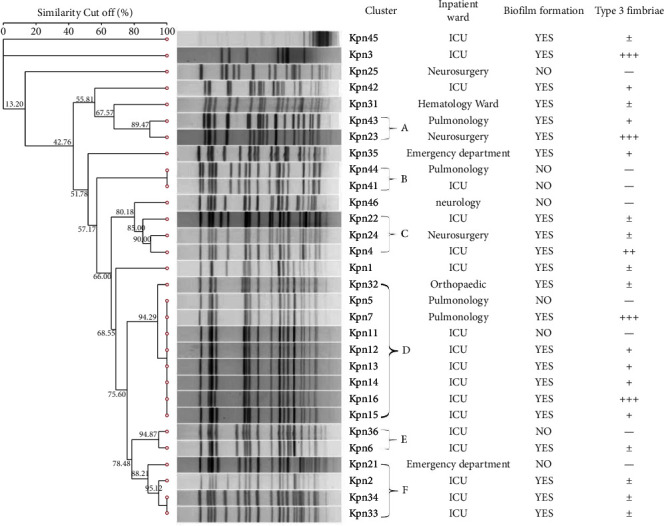

3.3. Homology Analysis of ESBL-Producing K. pneumoniae Isolates

After PFGE cluster analysis, based on drown dendrogram 22 clusters with more than 85% similarity cut-off were found among 30 isolates. Similarity from 85% to 100% on the dendrogram form a gene cluster (A–F) among which gene cluster D (including Kpn5/7/11/16) had the highest percentage of 40% (9/22) and may have signal clonal advantage. By considering the distinct pulsotypes obtained in the current study it seems that the genetic heterogeneity of ESBL-producing K. pneumoniae is more conserved in the North of Ruijin Hospital (Figure 2). Quantitative analysis of biofilm formation using 0.1% crystal violet staining showed significant differences in biofilm formation between the Kpn5 and Kpn7 strains, as well as between the Kpn11 and Kpn16 strains. To reduce interference factors and narrow the screening scope for potential biofilm formation target genes, four clinical ESBL-producing K. pneumoniae isolates with high homology and significant differences in biofilm formation were selected for further analysis.

Figure 2.

PFGE cluster analysis results of ESBL-producing K. pneumoniae strains. Dendrogram representing the genetic relationship between 30 ESBL-producing K. pneumoniae isolates after restriction with the XbaI enzyme. The gene cluster was formed on the dendrogram with a similarity cut off between 85% and 100% of which 22 PFGE stripe of ESBL-producing K. pneumoniae contained 6 gene clusters (A–F).

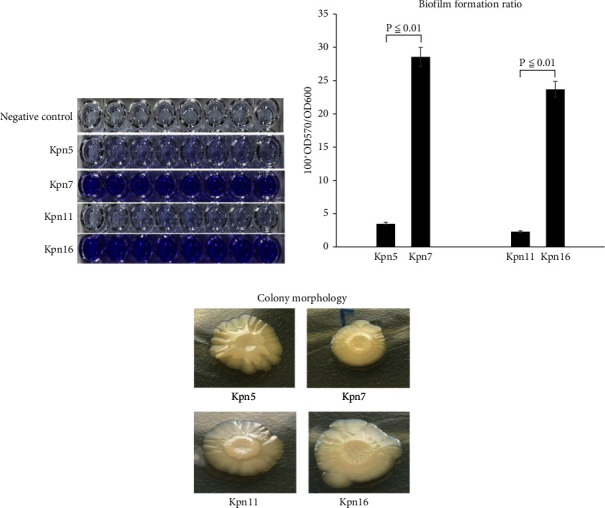

3.4. Differential Evaluation of Biofilm Formation Amongst Four ESBL-Producing K. pneumoniae

We set up LB solid media specially designed for the rugose colony morphology experiments and observed the phenotype after colony formation. The surfaces of the Kpn7 and Kpn16 colonies were relatively dry with obvious folds, but the Kpn5 and Kpn11 colony surfaces were smooth without obvious fold phenomena. Biofilm formation ratio determination showed that Kpn7 and Kpn16 formed more biofilms Figure 3(c). 96-well crystal violet staining assays and relative quantity of biofilm formation analysis (using OD570/OD600 values P ≤ 0.01) also showed that Kpn7 and Kpn16 formed relatively more biofilms (Figures 3(a) and 3(b)). Thus, these phenotypic experiments all indicated that the highly homologous strains had significant differences in biofilm formation abilities. Kpn7 and Kpn16 had much stronger biofilm formation capability than Kpn5 and Kpn11.

Figure 3.

Differential analysis of biofilm formation by Kpn5, Kpn7, Kpn11, and Kpn16. (a) Biofilms formed on the 96-well plate, as demonstrated by crystal violet staining. (b) Quantification of biofilm formation by measuring OD570 and OD600 values. (c) Biofilm folds formed by the Kpn5, Kpn7, Kpn11, and Kpn16 strains on LB solid medium.

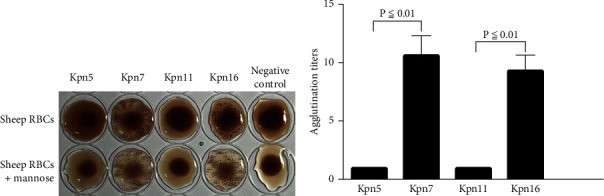

3.5. Expression Analysis of Types 1 and 3 Fimbriae of Four Experimental ESBL-Producing K. pneumoniae Strains

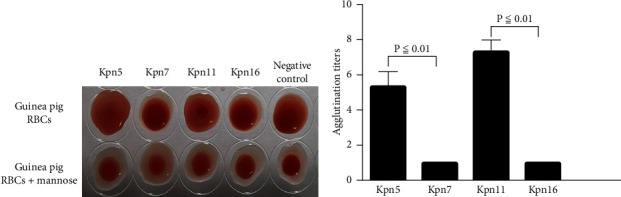

Most clinical ESBL-producing K. pneumoniae strains express both type 1 and type 3 fimbriae. Type 1 fimbriae can agglutinate guinea pig erythrocytes, but this reaction can be inhibited by D-mannose (“mannose-sensitive agglutination”). Type 3 fimbriae, in contrast, can agglutinate acidified sheep erythrocytes, but this reaction is not inhibited by D-mannose (“mannose-resistant agglutination”) [15]. Our results indicated that Kpn7 and Kpn16 showed mannose-resistant agglutination reactions in sheep erythrocytes, but Kpn5 and Kpn11 did not (Figure 4(a)). The sheep erythrocyte agglutination titer ratio for Kpn5 and Kpn7 was 1 : 10.07, but was 1 : 8.97 for Kpn11 and Kpn16 (Figure 4(b)). Additionally, guinea pig erythrocyte agglutination results showed that Kpn5 and Kpn11 had mannose-sensitive agglutination reactions, but Kpn7 and Kpn16 did not (Figure 5(a)). The guinea pig erythrocyte agglutination titer ratio for Kpn7 and Kpn5 was 1 : 5.03, but was 1 : 7.12 for Kpn16 and Kpn11 (Figure 5(b)). Taken together, these results suggest that Kpn7 and Kpn16 express more type 3 fimbriae than Kpn5 and Kpn11, and that overexpression of type 3 fimbriae is a major driver of the stronger biofilm formation abilities observed in the Kpn7 and Kpn16 strains. Interestingly, Kpn5 and Kpn11 expressed more type 1 fimbriae than Kpn7 and Kpn16.

Figure 4.

Sheep erythrocytes agglutination assay of ESBL-producing K. pneumoniae isolates. (a) Results of sheep erythrocyte agglutination by Kpn5, Kpn7, Kpn11, and Kpn16. Kpn7 and Kpn16 showed mannose-resistant agglutination reactions. (b) Sheep erythrocytes agglutination titers for Kpn5, Kpn7, Kpn11, and Kpn16.

Figure 5.

Guinea pig erythrocyte agglutination assay of ESBL-producing K. pneumoniae isolates. (a) Results of guinea pig erythrocyte agglutination by Kpn5, Kpn7, Kpn11, and Kpn16. Kpn5 and Kpn11 showed mannose-sensitive agglutination reactions. (b) Guinea pig erythrocyte agglutination titers for Kpn5, Kpn7, Kpn11, and Kpn16.

3.6. RNA-Seq Transcriptomic Analysis

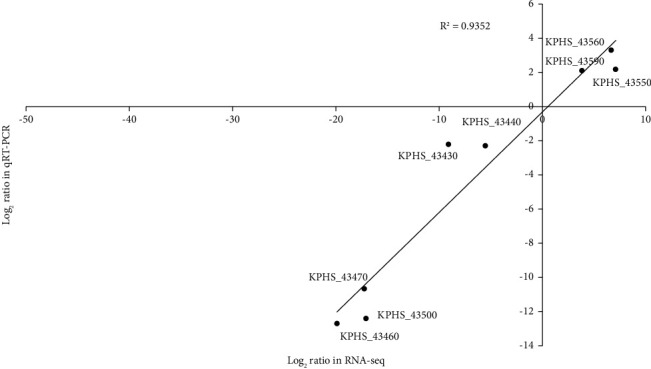

RNA-seq was used to monitor differences in the transcriptomic mRNA profiles between Kpn5 and Kpn7 as well as Kpn11 and Kpn16 at a global scale. A total of 82 genes were found to be differentially expressed in both groups, with 26 of them having high fold differences (Log2FoldChange>2) (Table 4). After qRT-PCR verification, the correlation index reached 0.90, indicating that the sequencing data were reliable (Figure 6). MrkABCDF gene cluster expression was significantly upregulated in Kpn7 and Kpn16 compared to Kpn5 and Kpn11. Type 3 fimbriae are encoded by the mrkABCDF operon [16], which includes mrkA, which encodes the pilus subunit; mrkB, which helps control the organization of protein surface subunits; mrkC, which encodes the scaffold proteins for type 3 fimbriae and is located on the outer membrane; and mrkD, which encodes the tip of the fimbriae and endows it with its adhesive properties. MrkF can be randomly integrated into positively changing fimbriae to increase their stability [17–19]. We found that fimbriae 1 gene clusters were significantly upregulated in both Kpn5 and Kpn11 relative to Kpn7 and Kpn16. The mean log folds of the KPHS_43480, KPHS_43490, KPHS_43500, and KPHS_43510 gene cluster was 15.56 times higher in Kpn7 and Kpn16 than that in Kpn5 and Kpn11. Thus, this gene cluster may be related to differences in biofilm formation between these strains.

Table 4.

List of 26 significantly differentially expressed genes in Kpn5 VS Kpn7 and Kpn11 VS Kpn16.

| Gene Id | MeanTPM (Kpn5/Kpn7) | MeanTPM (Kpn11/Kpn16) | Result | Log2FoldChange | Gene description |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| KPHS_43430 | 1.87/72.58 | 1.5/87.51 | Down | −5.3/−5.9 | Putative fimbrial-like protein |

| KPHS_43440 | 0.21/136.92 | 0.34/164.2 | Down | −9.3/−8.9 | Putative fimbrial-like protein |

| KPHS_43450 | 0.39/115.66 | 0.48/135 | Down | −8.2/−8.1 | Putative fimbrial usher protein |

| KPHS_43460 | 0.0001/86.42 | 0.0001/116.81 | Down | −19.7/−20.1 | MrkB fimbrial protein |

| KPHS_43470 | 0.0001/1383.18 | 0.86/1622.43 | Down | −23.7/−10.9 | MrkA fimbrial protein |

| KPHS_43480 | 0.0001/15.31 | 0.0001/38.12 | Down | −17.2/−18.5 | Hypothetical protein |

| KPHS_43490 | 0.0001/0.4 | 0.0001/0.31 | Down | −11.9/−11.6 | EamA family transporter |

| KPHS_43500 | 0.0001/12.61 | 0.0001/16.53 | Down | −16.9/−17.3 | Putative regulatory protein MarR |

| KPHS_43510 | 0.0001/0.86 | 0.0001/1.57 | Down | −13.1/−13.9 | Nickel/cobalt transporter |

| KPHS_43550 | 338.41/3.97 | 639.63/3.09 | Up | 6.4/7.69 | Major type 1 subunit fimbrin (pilin) |

| KPHS_43560 | 27.4/0.53 | 65.83/0.35 | Up | 5.7/7.6 | Fimbrial protein involved in type 1 pilus biosynthesis |

| KPHS_43570 | 23.96/0.2 | 25.75/0.46 | Up | 6.9/5.8 | Periplasmic chaperone |

| KPHS_43580 | 9.36/0.69 | 17.01/0.71 | Up | 3.8/4.6 | Outer membrane protein for export and assembly of type 1 fimbriae |

| KPHS_43590 | 25.75/1.69 | 40.39/3.12 | Up | 3.9/3.7 | Type 1 fimbrial minor component |

| KPHS_43600 | 11.82/1.03 | 28.91/2.42 | Up | 3.5/3.6 | Fimbrial morphology protein |

| KPHS_43610 | 14.34/1.61 | 28.08/2.07 | Up | 3.2/3.2 | Fimbrial protein FimH |

| KPHS_43620 | 3.76/0.81 | 10.34/1.36 | Up | 2.2/2.9 | Putative fimbrial protein |

| KPHS_47790 | 6.35/0.91 | 3.02/1.02 | Up | 2.8/1.6 | Hypothetical protein |

| KPHS_35550 | 56.19/7.41 | 42.15/3.9 | Up | 2.9/3.4 | dTDP-4-dehydrorhamnose 3,5-epimerase |

| KPHS_33690 | 40.52/6.7 | 13/4.17 | Up | 2.6/1.6 | Hypothetical protein |

| KPHS_12940 | 9.41/1.51 | 4.29/1.41 | Up | 2.6/1.6 | Hypothetical protein |

| KPHS_04400 | 30.47/2.2 | 5.14/2.39 | Up | 3.8/1.1 | Hypothetical protein |

| KPHS_35580 | 47.58/11.78 | 36.66/7.91 | Up | 2.0/2.2 | dTDP-D-glucose 4,6-dehydratase |

| KPHS_35570 | 46.72/11.01 | 41.52/7.15 | Up | 2.1/2.5 | Glucose-1-phosphate thymidylyltransferase |

| KPHS_31660 | 40.98/9.19 | 29.51/11.04 | Up | 2.2/1.4 | Putative translation initiation inhibitor |

| KPHS_17580 | 17.19/3.82 | 29.47/11.84 | Up | 2.2/1.3 | Oxygen-insensitive NADPH nitroreductase |

Figure 6.

Comparison of transcription levels as determined by RNA-seq and quantitative reverse transcription-PCR. 8 genes were selected and subjected to qRT-PCR. The corresponding log2 values were plotted against RNA-seq data. The R2 for the two datasets was more than 0.90. R2: correlation coefficient.

4. Discussion and Conclusion

4.1. Discussion

K. pneumoniae is a common opportunistic pathogen in hospitals. In 2017, the WHO classified ESBL-producing K. pneumoniae as a “critical threat” [20, 21]. Bacterial biofilms are known to play a significant role in chronic and device-associated infections and can render conventional antibacterial treatments ineffective [22–25]. In this study, we explored the homology and biofilm formation capacity of ESBL-producing K. pneumoniae isolates obtained from clinical specimens. Thirty clinical ESBL-producing K. pneumoniae isolates were collected from 25 patients aged an average of 62 years. Among these isolates, we found that 73% (22/30) could form biofilms. We also showed that 84% (21/25) of our included clinical patients had histories of surgery, urinary tract catheterization, and/or arteriovenous intubation, which can increase the risk of nosocomial opportunistic infections. The strains in this study were mainly drived from sputum (12, 41.3%), secretions (7, 24.1%), urine (5, 17.2%), blood (2, 6.8%), bile (2, 6.8%), and catheter (1, 3.4%). In comparison with isolates from different sources, the biofilm formation value was higher for isolates from sputum than from secretion, urine, blood, bile and catheter but the difference was not statistically significant. Instead, we found that high percentages of the isolates had the capacity to form biofilms in vitro but that strains that do not express type 3 fimbriae were not able to form biofilms. These data, although derived from a limited number of strains, are consistent with the results of previous studies. In one recent study, Hossein Ali Rahdar et al. reported that, among carbapenem-resistant K. pneumoniae, 77.9% (53/68) were able to form biofilms [23]. In another study, Vuotto et al. demonstrated that extensively ESBL-producing K. pneumoniae strains had strong biofilm generation capacities [26]. Binzhi Dan et al. reported the same results either [27]. Indeed, several studies have confirmed that biofilm capacity is associated with organisms viability in hospital environments, implanted medical devices, and patient wounds [28–30]. Numerous studies have shown that type 3 fimbriae are a critical factor in biofilm formation, especially within K. pneumoniae strains. This may be related to the ability of type 3 fimbriae to attach to the surface of K. pneumoniae and promote colonization and cloning [31–33].

The formation of bacterial biofilms has a significant impact on both patients and healthcare institutions, and understanding the mechanisms underlying biofilm formation may aid the development of more effective interventions. In our study, after PFGE cluster analysis, eight strains out of 30 clinical ESBL-producing K. pneumoniae isolates showed high homology and were suspected to have regional clonal transmission properties. 0.1% crystal violet staining experiments and bacterial fold results showed that the biofilm formation ability of the Kpn7 and Kpn16 strains far outstripped that of the Kpn5 and Kpn11 strains. One of the reasons for this difference may be related to the variability of bacterial living environments. Bacteria inside these biofilms needed to be able to quickly adapt to differing environmental stimuli and alter their gene expression. Both K. pneumoniae surface structures (fimbriae) and extracellular polysaccharides (cellulose) play an important role in biofilm formation [34, 35]. However, we did not detect cellulose production on our cellulase digestion assays or with β-1, 4-linkage specific calcofluor staining, findings which might be related to the low degree of cellulose synthesis that occurs in in vitro. Most of our clinical ESBL-producing K. pneumoniae isolates expressed type 1 and/or type 3 fimbriae, which we characterized, respectively, by their ability to mediate mannose-sensitive agglutination of guinea pig erythrocytes or their ability to mediate acidified sheep erythrocytes [36]. Findings from the acid-sheep and guinea pig RBC agglutination tests showed that the Kpn7 and Kpn16 strains expressed more type 3 and fewer type 1 fimbriae, but that the Kpn5 and Kpn11 expressed more type 1 and fewer type 3 fimbriae. Transcriptomic analysis showed that the mean log fold of the mrkABCDF gene cluster, which encodes type 3 fimbriae, was 12.01 times higher in the Kpn7 and Kpn16 strains than in the Kpn5 and Kpn11 strains. Additionally, the mean log fold of gene cluster encoding type 1 fimbriae was 4.66 times higher in the Kpn5 and Kpn11 strains than in the Kpn7 and Kpn16 strains. Phenotypic and molecular experiments indicated a positive correlation between biofilm formation ability and expression of type 3 fimbriae, and a negative correlation between the expression of type 1 fimbriae and biofilm formation. Di Martino et al. have also shown that the expression of type 3 fimbriae is positively correlated with biofilm formation abilities, but that strains only expressing the type 1 fimbriae cannot form biofilms [31]. Schroll et al.'s findings are also consistent with ours, as they found that biofilm formation in flow cell systems was associated with type 3 fimbriae rather than type 1 fimbriae, and that the expression of type 1 fimbriae was downregulated in K. pneumoniae strains which produced biofilms using a well-defined isogenic mutant [37]. Schroll et al. suggested that the downregulation of type 1 fimbriae in biofilm cells may be related to bacterial capsules, as the presence of capsules is crucial for the establishment and maturation of K. pneumoniae biofilms, and previous studies have confirmed that the presence of capsules could inhibit the functions of the type 1 fimbriae [38–40]. Nevertheless, the vast majority of K. pneumoniae isolates express both type 1 and type 3 fimbriae, and using epidemiological studies to characterize their role in biofilm formation is difficult.

The RNA sequencing-based transcriptome results showed that KPHS_43480, KPHS_43490, KPHS_43500, and KPHS_43510 gene cluster expression in the Kpn7 and Kpn16 strains was 15.56 times higher than that in the Kpn5 and Kpn11 strains. KPHS_43480 encodes proteins containing the DUF1471 domain, which has an unknown function, although it is present in several Enterobacteriaceae species (YdgH, YhcN, BhsA, and McbA) and may play a role in stress responses and/or biofilm formation and pathogenesis [41]. BhsA may decrease biofilm formation by repressing cell-cell interactions and cell surface interactions. YdgH and YhcN may respond to peroxide/acid stressors, and their paralogues have been implicated in bacteria pathogenesis. McbA may inhibit biofilm formation and overproduce colonic acid via currently unknown mechanisms. KPHS_43490 encodes EamA family transporters (formerly known as DUF6 transporters), which are part of several hypothetical membrane proteins of unknown functions [42]. KPHS_43500 encodes the MarR protein, which affects bacterial antibiotic resistance and the expression of capsule regulatory factors [43]. KPHS_43510 encodes a high-affinity nickel/cobalt transporter, which is involved in the incorporation of nickel into H2-uptake hydrogenase and urease and which is essential for the expression of catalytically active hydrogenase and urease [44]. Future studies should further characterize these regulatory mechanisms to better understand the processes underlying bacterial biofilm formation.

4.2. Conclusion

In this study, the genome homology and biofilm formation ability of 30 ESBL-producing K. pneumoniae strains from North Campus of Ruijin Hospital were initially explored. Even though two strains with the cut-off of PFGE reached 100% similarity, they generated biofilms differently. Meanwhile, high percentage of ESBL-producing K. pneumoniae isolates formed biofilms in vitro, and that strains that did not express type 3 fimbriae did not have biofilm formation capacity while type 1 fimbriae were downregulated during biofilm formation. Gene cluster of KPHS_43480, KPHS_43490, KPHS_43500, and KPHS_43510 may be related to biofilm, but few reported. Further studies were needed to fully understand the regulatory mechanisms of these genes.

Acknowledgments

This study was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (contract no. NSFC32370038) and supported by Shanghai Jiading District Center for Disease Control and Prevention (contract no. JDKW-2019-W21).

Contributor Information

Qian Peng, Email: peng59991569@163.com.

Yanping Han, Email: hypiota@hotmail.com.

Data Availability

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this manuscript. The RNA-seq data have been submitted in National Center for Biotechnology Information (BioProject: PRJNA1132956) (SRA:SRR29734451/SRR29734452/SRR29734453/SRR29734454) (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sra?LinkName=bioproject_sra_all&from_uid=1132956). The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding authors upon reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Authors' Contributions

Xiaofang Gao and Haili Wang contributed equally to this work and should be considered as co-first authors.

References

- 1.Ivin M., Dumigan A., de Vasconcelos F., et al. Natural killer cell-intrinsic type I IFN signaling controls Klebsiella pneumoniae growth during lung infection. PLoS Pathogens . 2017;13(11):p. e1006696. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1006696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hassan A., Usman J., Kaleem F., Omair M., Khalid A., Iqbal M. Evaluation of different detection methods of biofilm formation in the clinical isolates. Brazilian Journal of Infectious Diseases . 2011;15(4):305–311. doi: 10.1016/s1413-8670(11)70197-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mirzaee M., Ranjbar R., Mirzaie A. ESBL producing Klebsiella pnumoniae isolates recovered from clinical cases in tehran, Iran. Iranian Journal of Public Health . 2021;50(6):1298–1299. doi: 10.18502/ijph.v50i6.6437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wang G., Zhao G., Chao X., Xie L., Wang H. The characteristic of virulence, biofilm and antibiotic resistance of Klebsiella pneumoniae. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health . 2020;17(17):p. 6278. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17176278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hsu C., Chang I., Hsieh P., et al. A novel role for the Klebsiella pneumoniae sap (sensitivity to antimicrobial peptides) transporter in intestinal cell interactions, innate immune responses, liver abscess, and virulence. The Journal of Infectious Diseases . 2019;219(8):1294–1306. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiy615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.de Oliveira J., Lisboa L. d B. Hospital-acquired infections due to gram-negative bacteria. New England Journal of Medicine . 2010;363(15):1482–1484. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc1006641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rutledge-Taylor K., Matlow A., Gravel D., et al. A point prevalence survey of health care-associated infections in Canadian pediatric inpatients. American Journal of Infection Control . 2012;40(6):491–496. doi: 10.1016/j.ajic.2011.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Allegranzi B., Nejad S. B., Combescure C., et al. Burden of endemic health-care-associated infection in developing countries: systematic review and meta-analysis. The Lancet . 2011;377(9761):228–241. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(10)61458-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rosenthal V. Health-care-associated infections in developing countries. The Lancet . 2011;377(9761):186–188. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(10)62005-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sarshar M., Behzadi P., Ambrosi C., Zagaglia C., Palamara A., Scribano D. FimH and anti-adhesive therapeutics: a disarming strategy against uropathogens. Antibiotics . 2020;9(7):p. 397. doi: 10.3390/antibiotics9070397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jin X., Marshall J. Mechanics of biofilms formed of bacteria with fimbriae appendages. PLoS One . 2020;15(12):p. e0243280. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0243280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dice L. R. Measures of the amount of ecologic association between species. Ecology . 1945;26(3):297–302. doi: 10.2307/1932409. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Han H., Zhou H., Li H., et al. Optimization of pulse-field gel electrophoresis for subtyping of Klebsiella pneumoniae. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health . 2013;10(7):2720–2731. doi: 10.3390/ijerph10072720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sun F., Gao H., Zhang Y., et al. Fur is a repressor of biofilm formation in Yersinia pestis. PLoS One . 2012;7(12):p. e52392. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0052392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Stahlhut S., Struve C., Krogfelt K. Klebsiella pneumoniae type 3 fimbriae agglutinate yeast in a mannose-resistant manner. Journal of Medical Microbiology . 2012;61:317–322. doi: 10.1099/jmm.0.036350-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chan C., Chen F., Huang Y., et al. Identification of protein domains on major pilin MrkA that affects the mechanical properties of Klebsiella pneumoniae type 3 fimbriae. Langmuir . 2012;28(19):7428–7435. doi: 10.1021/la300224w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Langstraat J., Bohse M., Clegg S., Clegg S. Type 3 fimbrial shaft (MrkA) of Klebsiella pneumoniae , but not the fimbrial adhesin (MrkD), facilitates biofilm formation. Infection and Immunity . 2001;69(9):5805–5812. doi: 10.1128/iai.69.9.5805-5812.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wilksch J., Yang J., Clements A., et al. MrkH, a novel c-di-GMP-dependent transcriptional activator, controls Klebsiella pneumoniae biofilm formation by regulating type 3 fimbriae expression. PLoS Pathogens . 2011;7(8):p. e1002204. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ong C., Beatson S., Totsika M., Forestier C., McEwan A., Schembri M. Molecular analysis of type 3 fimbrial genes from Escherichia coli, Klebsiella and Citrobacter species. BMC Microbiology . 2010;10(1):p. 183. doi: 10.1186/1471-2180-10-183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wyres K., Holt K. Klebsiella pneumoniae as a key trafficker of drug resistance genes from environmental to clinically important bacteria. Current Opinion in Microbiology . 2018;45:131–139. doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2018.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Juan C., Chuang C., Chen C., Li L., Lin Y. Clinical characteristics, antimicrobial resistance and capsular types of community-acquired, healthcare-associated, and nosocomial Klebsiella pneumoniae bacteremia. Antimicrobial Resistance and Infection Control . 2019;8:p. 1. doi: 10.1186/s13756-018-0426-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Singh A., Yadav S., Chauhan B., et al. Classification of clinical isolates of Klebsiella pneumoniae based on their in vitro biofilm forming capabilities and elucidation of the biofilm matrix chemistry with special reference to the protein content. Frontiers in Microbiology . 2019;10:p. 669. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2019.00669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rahdar H., Malekabad E., Dadashi A., et al. Correlation between biofilm formation and carbapenem resistance among clinical isolates of Klebsiella pneumoniae. Ethiopian journal of health sciences . 2019;29(6):745–750. doi: 10.4314/ejhs.v29i6.11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mirzaie A., Ranjbar R. Antibiotic resistance, virulence-associated genes analysis and molecular typing of Klebsiella pneumoniae strains recovered from clinical samples. AMB Express . 2021;11(1):p. 122. doi: 10.1186/s13568-021-01282-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mirzaee M., Ranjbar R., Mirzaie A. ESBL producing Klebsiella pnumoniae isolates recovered from clinical cases in tehran, Iran. Iranian Journal of Public Health . 2021;50(6):1298–1299. doi: 10.18502/ijph.v50i6.6437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Vuotto C., Longo F., Pascolini C., et al. Biofilm formation and antibiotic resistance in Klebsiella pneumoniae urinary strains. Journal of Applied Microbiology . 2017;123(4):1003–1018. doi: 10.1111/jam.13533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dan B., Dai H., Zhou D., Tong H., Zhu M. Relationship between drug resistance characteristics and biofilm formation in Klebsiella pneumoniae strains. Infection and Drug Resistance . 2023;16(0):985–998. doi: 10.2147/idr.s396609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Costerton J., Stewart P., Greenberg E. Bacterial biofilms: a common cause of persistent infections. Science . 1999;284(5418):1318–1322. doi: 10.1126/science.284.5418.1318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hall-Stoodley L., Costerton J., Stoodley P. Bacterial biofilms: from the natural environment to infectious diseases. Nature Reviews Microbiology . 2004;2(2):95–108. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Donlan R., Costerton J. Biofilms: survival mechanisms of clinically relevant microorganisms. Clinical Microbiology Reviews . 2002;15(2):167–193. doi: 10.1128/cmr.15.2.167-193.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Di Martino P., Cafferini N., Joly B., Darfeuille-Michaud A. Klebsiella pneumoniae type 3 pili facilitate adherence and biofilm formation on abiotic surfaces. Research in Microbiology . 2003;154(1):9–16. doi: 10.1016/s0923-2508(02)00004-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Stahlhut S., Struve C., Krogfelt K., Reisner A. Biofilm formation of Klebsiella pneumoniae on urethral catheters requires either type 1 or type 3 fimbriae. FEMS Immunology and Medical Microbiology . 2012;65(2):350–359. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-695x.2012.00965.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Huang Y., Liao H., Wu C., Peng H. MrkF is a component of type 3 fimbriae in Klebsiella pneumoniae. Research in Microbiology . 2009;160(1):71–79. doi: 10.1016/j.resmic.2008.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Römling U. Molecular biology of cellulose production in bacteria. Research in Microbiology . 2002;153(4):205–212. doi: 10.1016/s0923-2508(02)01316-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Huertas M., Zárate L., Acosta I., et al. Klebsiella pneumoniae yfiRNB operon affects biofilm formation, polysaccharide production and drug susceptibility. Microbiology . 2014;160(12):2595–2606. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.081992-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Murphy C., Clegg S. Klebsiella pneumoniae and type 3 fimbriae: nosocomial infection, regulation and biofilm formation. Future Microbiology . 2012;7(8):991–1002. doi: 10.2217/fmb.12.74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Schroll C., Barken K., Krogfelt K., Struve C. Role of type 1 and type 3 fimbriae in Klebsiella pneumoniae biofilm formation. BMC Microbiology . 2010;10:p. 179. doi: 10.1186/1471-2180-10-179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Balestrino D., Ghigo J., Charbonnel N., Haagensen J., Forestier C. The characterization of functions involved in the establishment and maturation of Klebsiella pneumoniae in vitro biofilm reveals dual roles for surface exopolysaccharides. Environmental Microbiology . 2008;10(3):685–701. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2007.01491.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Matatov R., Goldhar J., Skutelsky E., et al. Inability of encapsulated Klebsiella pneumoniae to assemble functional type 1 fimbriae on their surface. FEMS Microbiology Letters . 1999;179(1):123–130. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1097(99)00402-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Schembri M., Dalsgaard D., Klemm P. Capsule shields the function of short bacterial adhesins. Journal of Bacteriology . 2004;186(5):1249–1257. doi: 10.1128/jb.186.5.1249-1257.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Eletsky A., Michalska K., Houliston S., et al. Structural and functional characterization of DUF1471 domains of Salmonella proteins SrfN, YdgH/SssB, and YahO. PLoS One . 2014;9(7):p. e101787. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0101787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Västermark Å, Almén M., Simmen M., Fredriksson R., Schiöth H. Functional specialization in nucleotide sugar transporters occurred through differentiation of the gene cluster EamA (DUF6) before the radiation of Viridiplantae. BMC Evolutionary Biology . 2011;11(1):p. 123. doi: 10.1186/1471-2148-11-123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Beggs G., Brennan R., Arshad M. MarR family proteins are important regulators of clinically relevant antibiotic resistance. Protein Science . 2020;29(3):647–653. doi: 10.1002/pro.3769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kersey C., Agyemang P., Dumenyo C. CorA, the magnesium/nickel/cobalt transporter, affects virulence and extracellular enzyme production in the soft rot pathogen Pectobacterium carotovorum. Molecular Plant Pathology . 2012;13(3):327–371. doi: 10.1111/j.1364-3703.2012.00793.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this manuscript. The RNA-seq data have been submitted in National Center for Biotechnology Information (BioProject: PRJNA1132956) (SRA:SRR29734451/SRR29734452/SRR29734453/SRR29734454) (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sra?LinkName=bioproject_sra_all&from_uid=1132956). The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding authors upon reasonable request.