Abstract

Background

Regular engagement in moderate-to-vigorous physical activity (MVPA) during childhood yields a myriad of health benefits, and contributes to sustained MVPA behaviors into adulthood. Given the influence of parents on shaping their child’s MVPA behaviour, the family system represents a viable target for intervention. The purpose of this study is to compare the effects of two intervention conditions designed to increase child MVPA: (1) A standard education + planning intervention providing information about benefits, action planning, and coping planning; and (2) An augmented physical activity education + planning intervention that includes the components of the standard intervention, as well as a focus on family identity promotion and developing as an active member of the family.

Methods

A two-arm parallel single-blinded randomized trial will compare the two conditions over 6 months. Eligible families have at least one child aged 6–12 years who is not meeting the physical activity recommendations within the Canadian 24-Hour Movement Guidelines (i.e.,<60 min/day of MVPA). Intervention materials targeting family identity promotion will be delivered online via zoom following baseline assessment, with booster sessions at 6-weeks and 3-months. Child MVPA will be measured by wGT3X-BT Actigraph accelerometry at baseline, 6-weeks, 3-months, and 6-months as the primary outcome. At these same time points, parent cognition (e.g., attitudes, perceived control, behavioral regulation, habit, identity) and support behaviours, and parent-child co-activity will be assessed via questionnaire as secondary outcomes. Child-health fitness measures will be also administered through fitness testing at baseline and 6-months as secondary outcomes. Finally, upon completion of the trial’s 6-month measures, a follow-up end-of-trial interview will be conducted with parents to examine parents’ experiences with the intervention.

Results

So far, 30 families have been enrolled from the Southern Vancouver Island and Vancouver Lower Mainland area. Recruitment will be continuing through 2026 with a target of 148 families.

Discussion

This study will contribute to the understanding of effective strategies to increase child physical activity by comparing two intervention approaches. Both provide parents with education on physical activity benefits, action planning, and coping planning supports. However, one intervention also incorporates components focused on promoting an active family identity and involving all family members in physical activity together. The findings from this study have the potential to inform the design and implementation of public health initiatives aimed at improving physical activity participation in children and guide the development of more effective interventions that leverage the crucial role of parents and the family system in shaping children’s physical activity behaviors.

Trial Registration

The clinical trial registration ID is NCT05794789. This trial was registered with clinicaltrials.gov on March 2nd, 2023, with the last updated release on September 28th, 2023.

Keywords: Exercise, Self-regulation, Planning, Multi-process action control, Attitudes, Parental support

Introduction

Children who engage in consistent moderate-to-vigorous physical activity (MVPA) are more likely to display positive health outcomes than their low active counterparts, such as better body composition, increased cardiorespiratory and musculoskeletal fitness, improved cardiovascular and metabolic health, positive emotional and behavioral regulation, and a reduced risk of chronic diseases [1–5]. Additionally, higher levels of childhood physical fitness have been associated with superior health and sustained physical activity (PA) participation in later adulthood [6].

Despite this overwhelming evidence, most children and youth (within the Western World) fail to adhere to international public health guidelines of 60 min per day of MVPA [7]. In Canada, over 80% of children are not active enough to reap the optimal benefits of MVPA [8]. Additional findings indicate that only 13% of 3–4-year-olds [9] and 17% of 5–17-year-olds meet the international guidelines for MVPA [8, 9]. Therefore, it is clear that promoting PA during childhood is a public health priority.

Children spend considerable time within the care of their parents. Parents play an important role in establishing child PA behaviours; therefore, emphasizing the family system as a viable target for PA promotion initiatives [10]. In support of this contention, there is a consistent and medium-sized correlation between supportive PA parenting practices and child PA [11–13]. Parental support involves any actions (by parents) designed to meet the psychological, social, and physical needs of their children with the goal of promoting their child’s physical activity [14, 15]. These support behaviours may manifest as encouragement, logistical support (e.g., signing children up for recreation activities, transport to activities), and intergenerational PA behaviors (e.g., parent and child recreation activities together) [13, 16].

Despite support for the positive correlations between parental support practices and child PA in observational designs, interventions focused on family PA have been generally unsuccessful, particularly in terms of sustaining behavioral changes [12]. Specifically, interventions focused on increasing parental support of child PA have been found to result in some positive changes in children’s PA (Standard Mean Difference (SMD) = 0. 29; 95% Confidence Interval (CI) 0.14 to 0.45) in the first six-weeks [12], but there is little evidence for sustained changes in the long-term. Previous randomized trials promoting family PA [15] and MVPA [14, 17] have reflected this evidence, showing that assisting parents with self-regulation skills (e.g., planning) can improve children’s MVPA over educational approaches (e.g., persuasive facts about the benefits of activity), yet, this approach also appears to wane in its effectiveness by 6-months post intervention [14]. In light of these outcomes, there is a need to focus on improving the effectiveness of family-based interventions for MVPA so that they may sustain initial behavioral changes.

To address this, contemporary research in PA promotion has started to examine the effectiveness of behavior change interventions that specifically target long-term maintenance processes within the general population [18], such as building habits and identity [19]. One of the most frequently applied frameworks within the PA domain with this focus on habit and identity is the multi-process action control framework (M-PAC) [20, 21]. The tenets of M-PAC suggest that sustained behaviour change is a function of three subsequent and overlapping processes. At the foundation of M-PAC are reflective processes (i.e., conscious expectations of behavioral consequences), such as attitudes and perceptions of control, which culminate in the formation of an intention to engage in PA. This framework is similar to the tenets of most intention-based social cognitive theories [22]. However, turning intention into behavior is dependent on regulation processes (e.g., planning, monitoring, regulating emotions), as people begin to use tactics to help translate positive intentions into action [23]. Finally, behavioral maintenance [19, 20] is developed through habit and identity formation, known as reflexive processes (i.e., stimulus-based motivation from learned associations and self-categorization).

The M-PAC framework is backed by over 30 tests in the PA domain including observational evidence that the provision of parental support is predictive of child PA intentions [24–26]. While M-PAC is currently being utilized to investigate the role of parental support habits on children’s PA [27–29], to our knowledge, there has not been a trial to explore this framework and the effectiveness of PA identity promotion in the family system. Previous observational research on predicting parental support for children’s PA [24] and reviews of PA identity processes [30–33], suggest identity may be a potent mechanism for sustaining long term PA.

Identity represents the meanings that individuals assign to the (multiple) roles they may play and the expectations that are associated with those roles [33]. This encompasses both self-identity and social identity. Self-identity involves the meanings and expectations a person attaches to a role based on their own internalized belief. For example, one’s self-identity as a physically active person, may include beliefs about the importance of regular exercise and seeing value in an active lifestyle. Social identity on the other hand reflects a person’s self-concept derived from their perceived membership in various social groups [34]. For example, one’s social identity as a member of an active family would involve the family’s shared views on the importance of physical activity and the expected behaviors of family members, such as regularly engaging in active outings together or supporting each other’s fitness goals.

Our self and social identities initiate a self-regulating system that increases our motivation and attention to sustain health behaviours, making them more resilient in the face of counter-stimuli or threats to the identity [31]. When an exercise identity is integrated into the self-concept, physical activity becomes an internalized value and pursuit. Moreover, identifying as a member of ‘an active group’ (e.g., family) can provides a sense of social support, establish social norms, and motivate identity-consistent behavior to affirm group membership [30, 35]. When this happens, behaviour can become habitual (translating positive intentions into behaviour), enabling greater attention to seize identity-affirming physical activity opportunities when they are presented [32].

In sum, grounding physical activity interventions in identity theory [33] and social identity theory [34] may provide a pathway for physical activity to become more congruent with one’s self and social view and lasting behavior change. Helping participants to see their expectations and values attached to an active identity, along with the social influence of identifying with an active group, could help make regular physical activity an integral part of “who I am.” Our research aims to test this possibility by exploring self and social identity-based strategies for promoting physical activity adoption and maintenance in families over time.

Study objectives and hypotheses

The primary objective of this study is to explore the effects of a theory-based intervention that targets family identity promotion (with education and planning) to promote child MVPA. For this study, we include the promotion of both self-identity of the parent (i.e., I am a parent supportive of child PA) [36] and social identity [34, 37] of the family (i.e., we are an active family) to better account for the family system [10]. Based off previous literature [17, 38]– [41], it is hypothesized that the MVPA for children in the identity promotion condition will be higher in comparison to the MVPA for children in the standard PA education and planning condition at six months.

Secondary objectives of the trial include the evaluation of children’s health-related fitness outcomes between the identity promotion condition and the education and planning condition at baseline and 6-months. It is hypothesized that child health-related fitness outcomes will be higher for the identity formation condition in comparison to the education and planning condition due to improved adherence. Specifically, in light of the anticipated superior adoption and maintenance of MVPA by children in the identity condition, we also anticipate that they will display better fitness than those randomized to the planning condition.

Additionally, group differences among behavioural and health-related fitness outcomes will be examined by a mediation model. It is hypothesized that the effect of the assigned conditions (identity promotion vs. standard education and planning) on child MVPA will be mediated by parental support behaviors, and this mediation will be further explained by parents’ identity as supportive of their child’s physical activity (i.e., manipulation check). In turn, the covariance of parental support on health-related fitness outcomes is expected to be mediated by children’s MVPA levels. In the case of null outcomes for the primary objective, outcomes will be explored with a prediction model of change in PA rather than a mediation model [41, 42]. Lastly, this study will explore intergenerational, seasonal, or sex differences across primary outcomes by assigned condition.

Methods

The design, conduct, and reporting of the trial follows the Standard Protocol Items: Recommendations for Interventional Trials (SPIRIT) guidelines [43] and conforms to the Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) guidelines [44]. This study is approved by the University of Victoria (UVic) Human Research Ethics Board (HREB). Additionally, this study has harmonized ethics approval by the Research Ethics Board of BC (REBC) for multi-jurisdictional research with the University of British Columbia (UBC) and Vancouver Island University (VIU). The trial is registered with the Clinical Trials Registry maintained by the National Library of Medicine at the National Institutes of Health (ClinicalTrials.gov) Trial ID NCT05794789. The trial was registered on March 2nd of 2023, and last updated on September 28th, 2023.

If modifications or amendments to the protocol are required, the Project Coordinator will submit the necessary paperwork to the Research and Information Systems (RISe) at UBC. Upon approval, the appropriate updates are made to the trial registration on the Clinical Trials Registry.

Trial design

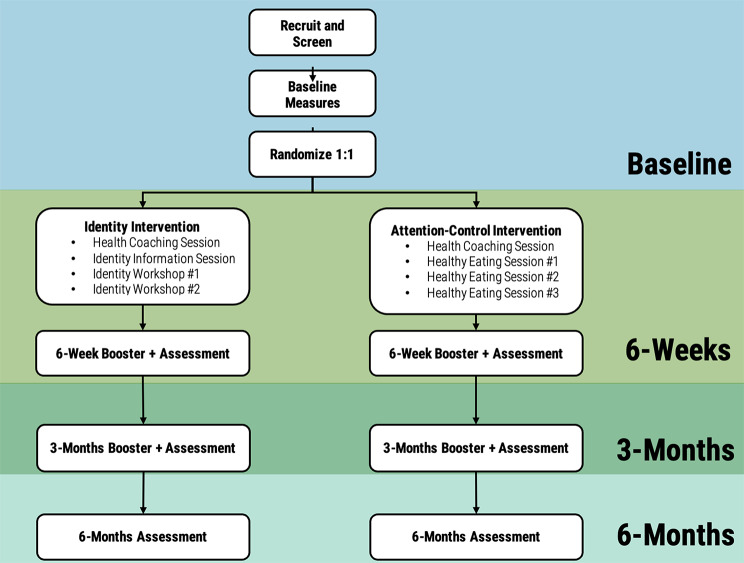

This study is a two-arm parallel single blinded randomized trial. After baseline assessment (fitness testing, MVPA, and questionnaire), participants are randomized to one of two groups: (1) physical activity education + planning + family identity promotion condition; or (2) physical activity education + planning condition for six months (See Fig. 1). The objective of the trial is to evaluate the efficacy of the identity promotion condition, when compared to the education + planning condition, at the primary end-point of the trial (6 months) with secondary assessment time points at 6-weeks and 3-months.

Fig. 1.

Procedures Outline

Sample size calculation

A power calculation was conducted to estimate the required sample size. Power was set at 0.80 with four repeated assessments, one-between group factor, an alpha of 0.05, and a medium effect size (Cohen’s f = 0.25), indicated that 128 families are needed to show a significant condition by time effect for PA [12, 45]. This effect size is consistent with previous studies examining physical activity interventions [46, 47]. With an expected attrition rate of 15% [14], 148 families (74 children per condition) will therefore be recruited.

Participants and eligibility

Participants are single or common law/married adult(s), with at least one child between the ages of six and twelve years. This age range has been shown to be the most effective for family-based intervention, as the influence of peer-relationships supercedes that of the parents by the teenage years. Families reside on Southern Vancouver Island spanning from Greater Victoria to the city of Nanaimo, British Columbia, Canada; as well as the Lower Mainland of British Columbia (Canada) encompassing Vancouver, Richmond, Surrey, Burnaby, Langley, and Coquitlam. Participants will be included if children participate in PA below Canadian recommendations of < 60 min/day of MVPA (screened by parental report through initial recruitment contact) [48]. To aid in the interpretation of this recommendation, our recruitment information includes examples of how one might accrue MVPA with an example schedule for the week. We also screen families based on child baseline accelerometry results (as a secondary assurance). If more than one child per family is eligible in this range, we randomly designate (via computer randomizer) a child as the target for analysis yet include all willing children within the study. If the child is not eligible due to meeting guidelines, the family is given the baseline honorarium, and removed from the study. The target parent(s) PA levels may be above or below the adult recommendations as they have no bearing on their eligibility to participate in the study.

Consent and permissions

Participating parents are required to provide written consent and complete.

ParQ + Health Screening Questionnaire [49] to ensure they are physically healthy (i.e., no known episode of chest pain, dizziness, or joint problems after physical activity) to engage in MVPA before participating in this study. Parents are required to sign informed consent forms if they agree to participate as a family unit, with verbal assent also obtained from the participating children from each family.

Recruitment

Recruitment is conducted by the Behavioural Medicine Lab at the University of Victoria in British Columbia, Canada. Based on our extensive experience with prior family trials [14, 15, 17, 27, 28], participants are recruited through a variety of avenues including (1) social media and online interest sites, (2) in-person markets and recruitment poster drops, and (3) community-based promotion and brand partnerships. The recruitment radius is stratified into three regions: Greater Victoria, Greater Nanaimo, and Greater Vancouver. Within each region, a complete list of schools, recreation centres, community centers, outdoor markets and health centers are approached to help facilitate recruitment, to maintain consistency along all regions of Southern Vancouver Island and Lower Mainland.

Participants are recruited primarily through the social media platforms Facebook and Instagram. Facebook and Instagram posts are made bi-monthly by the Behavioural Medicine Lab Recruitment Officer on the Behavioural Medicine Lab Facebook page (https://www.facebook.com/UVicBMED/) and Instagram account (@uvicbmed). These social media pages are linked, meaning a post made on Facebook is simultaneously shared on Instagram and vice versa. Posts are limited to 100 words or less and briefly describe the intent of the study and those eligible to partake, asking those interested to contact the Behavioural Medicine Lab through email or phone information provided in the post. Facebook posts are also shared to relevant Facebook groups (e.g., neighbourhood groups, young parent groups, homeschool group). Facebook posts are socially amplified by paying a small fee to have the post appear as an advertisement in a target demographic’s news feed. The target demographic is specified by selecting variables of age, location of residence, and other filters such as “parents”, and the advertisement typically run for 7 days.

The Recruitment Officer also sets up a recruitment booth on average 2–3 times at local markets and festival events during the summer, and at community and recreation centers in the winter to engage with potential participants, answer questions, and collect contact information for interested families. Posters are put up or mailed out every 3–4 months by a Research Assistant and/or Recruitment Officer in all major recreation centers in the area, as well as shopping centers, health care centers, and schools. Word of mouth is also used as a recruitment strategy. We currently recruit approximately 3–5 interested families per week with this strategy.

Additionally, we incorporated an incentive program to maximize recruitment interest. This program was set up through partnerships with local Universities (UVic, UBC, & VIU) as well as local businesses (Flying Squirrel, local gyms, apparel stores) to provide participants with draw prizes when screened to participate.

Randomization

Randomisation is performed by a Research Assistant assigned by the Research Coordinator to reduce bias using the Excel Sheet Randomization function. This is done with an allocation ratio of 1:1 to either the education + planning + identity promotion condition or education + planning condition. Participants are blind to their condition until the completion of the study, at which point they are informed of their group by the Project Coordinator and/or Research Assistant. Under no circumstance are participants informed of their condition while they are still enrolled in the study. Fitness testers are blind to each family’s condition as well, but the Research Coordinator and Research Assistants are aware of the condition to allow for correct delivery of intervention materials.

Procedures and protocol

When interested parents contact the lab, the Recruitment Officer follows up with an email to schedule a phone conversation. If initial contact is a message through Instagram or Facebook, the Recruitment Officer privately replies asking the person to call/email the contact provided in recruitment material or follow the link in the post that allows them to provide their contact information securely through an online form. An initial recruitment phone interview is set up with the Recruitment Officer, and families are screened using a parent-report of their child’s average physical activity per day as well as the ParQ + Health Screening Questionnaire [49]. If participants meet all eligibility criteria, the Recruitment officer advises the Project Coordinator, who then follows up with the family to schedule testing on site at our three satellite locations – UVic, UBC, or VIU.

Once deemed eligible and enrolled, participants are scheduled for a baseline assessment. At the initial baseline session, the Fitness Tester obtains written consent from parents and verbal assent from children, and at the completion of the fitness testing, the Fitness Tester provides the participating parent(s) and child (ren) with a short training session on how to wear and use the accelerometers, before sending them home for a week of wear. Upon completion of this device-assessed PA measure, the accelerometers are received through mail-back packages or courier pick-up, and the child MVPA is checked against PA recommendations [48] as a secondary screening procedure to exclude those families with children meeting international PA guidelines from the trial. Families whose children do not meet those guidelines and therefore eligible to continue are then randomized into one of two intervention conditions and parents are asked to complete a baseline questionnaire.

The Project Coordinator is responsible for guiding the two groups of participants through their respective interventions over the first 3 weeks after randomization. Both groups receive the same standard education + planning workshop in the first week. Then in weeks 2 and 3, each group receives two additional workshops relevant to their randomized intervention condition (i.e., education + planning, or education + planning + identity promotion), with one workshop per week.

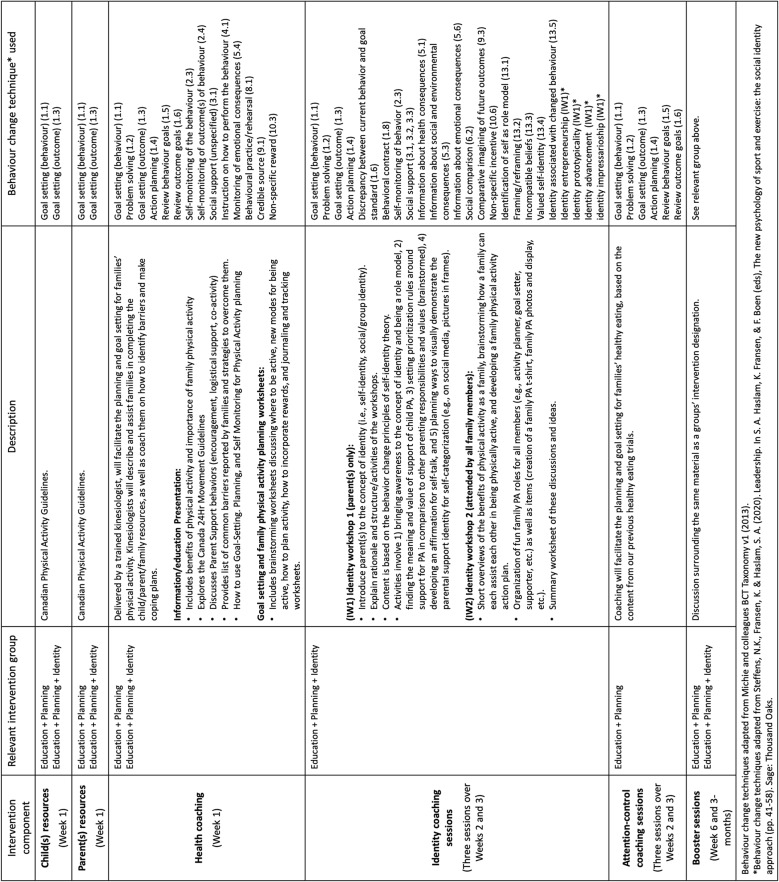

At 6 weeks post initial intervention period, families are given follow-up online questionnaires to complete and accelerometers to wear and to return via mail or courier pick-up. Both groups will receive “booster” sessions administered by a research assistant delivered online via Zoom on the same material as their intervention designation (see Table 1 for Behaviour Change Techniques (BCTs) per condition). This process will be followed for the three-month time-period. Thus, two booster sessions at both 6 weeks and 3 months will be provided to the education + planning and education + planning + identity promotion groups.

Table 1.

Overview of Intervention Content

At 6 months, in addition to the questionnaires and accelerometry assessment, children will be asked to perform fitness tests once again, and parents will participate in a brief end-of-trial qualitative interview to evaluate the efficacy of the intervention. These semi-structured interviews will allow us to evaluate two key aspects of fidelity outlined by Dumas et al. [50]: content fidelity, which refers to “what is done” in the intervention, and process fidelity, which captures “how it is done”. While measuring outcomes quantitatively will provide insight into the effectiveness of our intervention, it is also crucial to conduct a process evaluation through participant interviews. This qualitative approach will help determine whether the intervention program was delivered and carried out as intended. To assist study retention, we will offer monetary compensation across the study. Participants will receive an honorarium at baseline ($30), 6 weeks ($35), and 3 months ($40), and 6 months ($45) for a total of $150. Families only receive honoraria if they complete all the measures for the check point assessment (accelerometers, logbooks, questionnaires). Our experience with several past randomized control trials (RCTs) among families has shown that our protocol keeps attrition around or below 15% [14].

Standard education + planning condition

Participants in the standard education + planning condition will receive an initial baseline coaching session, designed exclusively for parents from a trained kinesiologist. Additionally, they will recieve an information-based series of worksheets that serve to standardize the delivery format of the material and provide a tangible knowledge translation (KT) product for the family after coaching. This is similar to our past family trials [14, 15, 27, 28]. The coaching session will consist of Canada’s 24-Hour Movement Guidelines for kids, which include recommendations of at least 60 min of MVPA a day [48] and a breakdown of ways for the parent to help their child achieve this PA, outlining three main types of parental support (encouragement, logistical support, and co-participation) [16]. The worksheet material is provided as prompts and suggestions, and contains questions that reinforce the benefits of PA for the child and family, as well as skill training content (how to plan for family PA). The material specifically includes a brainstorming exercise for parents where they list physical activities they think their children have found fun in the past. This list helps create a template for PA planning by contextualizing what the parents would like to do with their children.

Additional activities within this material explore how the environment and use of rewards can enhance engagement in physical activity behavior. Discussions around the physical environment (access to recreational facilities, parks, pedestrian-friendly neighborhoods) and social environment (support from family/friends) highlight how supportive environments align with values like health, wellbeing, enjoyment, and social connections. Exploring environments and rewards can facilitate conversations around the values associated with physical activity, and help individuals and families identify the values that motivate their physical activity choices, fostering sustained motivation and turning it into a value-driven habit. The subsequent skill training material for planning is based on several streams of prior work in the adult PA literature [51–53] and our prior family trials [17, 54]. Aligned with the regulatory processes of M-PAC, families plan for their PA support based on skill training for forming implementation intentions which involve creating specific “if-then” plans linking situational cues to desired behaviors (e.g., “If it’s Monday at 6 PM, then I will go for a 30-minute walk”), as well as action planning, coping planning and traditional goal setting [55–59].

Because the identity promotion condition has two additional workshops (when compared to the comparator intervention condition), the education + planning condition will also receive two additional workshops to compensate for time and attention, rather than content. The workshops will include education and planning material related to family healthy eating. This material will focus on the contents of the updated Canadian Food Guide [60], with discussions on macronutrient education, meal planning, healthy food choice strategies, and food labels. They will also receive a digital screen saver for their computer or cellular device with graphics highlighting “Healthy Food Habits Start At Home”.

Education/planning + identity condition

The identity formation condition will receive the same content as the education + planning condition during the initial baseline workshop. However, it will augment this material by explicitly targeting, bolstering, and enhancing parents’ “physical activity support identity” - that is, their self-categorization as a parent who actively supports their child’s engagement in physical activity. This will be done through two additional coaching sessions focused on the behavior change principles of self-identity [31, 61, 62] and social identity theory [34], as illustrated in Table 1.

Specifically, the second workshop will involve only the parent(s) to focus on parental support identity and the content based on the behavior change principles of self-identity theory [31, 61, 62]. This session’s activities are based on our prior PA identity formation trials among adults [38, 39, 54, 63] and are adapted to parental support of child PA. These activities are also augmented by principles from social identity theorizing [64] designed to bolster a ‘sense of us’ (i.e., we as an active family). These principles are tailored for parents, and include (as per Steffens et al., [64]): (a) identity entrepreneurship – when parents create a sense of shared social identity within the family, marked by a unique and compelling vision that distinguishes their supportive parental role from others; (b) identity prototypicality - when parents, in both action and perception, embody the values and ideals they aspire toward as active and supportive caregivers; (c) identity advancement - when parents prioritize their supportive roles as parents, and engage in activities that place the interests of their child above their own individual pursuits (as adults). This includes dedicating specific times in parents’ weekly schedule to support their child’s physical activities, even at the expense of personal or occupational demands, and lastly; (d) identity impressarioship - occurs when parents create unconventional or novel strategies to optimize their supportive parental identity. An example might involve trying out a new activity that’s new for every member of the family. These principles are emphasized throughout the second workshop and through a worksheet shared by the Research Coordinator with the participating parent. This worksheet is as follows:

* Activity #1: Workshop #2 begins with a review of parental support behaviours (i.e. encouragement, logisitical support, and co-participation), and a reflection question, where parents are encouraged to reflect on their willingness to change their behaviors to better support their child’s physical activity development. This reflection aligns with the concept of identity entrepreneurship [64], as it helps parents establish a clear vision of their role as a supportive parent.

* Activity #2 : Focuses on defining parental identity around physical activity engaging with the concepts of identity prototypicality and identity advancement [64]. Parents are prompted to consider the values and ideals they aspire to embody as supportive caregivers, list ways they can support their child’s physical activity, and prioritize their child’s physical activity over other responsibilities and pursuits.

* Activity #3: Involves brainstorming family activities and explores the concept of identity impressarioship [64]. Parents are encouraged to explore unconventional or novel strategies to optimize their supportive parental identity. By brainstorming ways to make use of their environment, having convenient “grab and go” activities on hand, and adjusting their home setup to facilitate physical activity, parents develop innovative approaches to support their child’s participation in PA. The self-reflection and planning tool in Activity 3 also allows parents recognize the enjoyment that PA provides for themselves and their family, and develop strategies to make it a priority.

* Activity #4: Parents brainstorm ways to effectively communicate and deal with potential issues that may arise during the implementation of their family PA plan and being a supportive parent. By anticipating and navigating challenges, parents create a supportive and cohesive family environment that reinforces their shared social identity as a physically active family. This proactive approach to problem-solving and communication helps parents establish a distinct and compelling vision of their family identity, as well as their own identity as a parent, thus encouraging identity entrepreneurship [64].

The third workshop involves the parent(s) and their child(ren) with a focus on social identity within the family (i.e., collective categorizing that “We are an Active Family”). The intervention material is grounded in social identity theory [34], self-categorization theory [36], and group cohesion behaviour change techniques [65], which emphasize the importance of group membership and shared identity in shaping behavior.

*Workshop 3, Activity #1: The workshop begins with a discussion of the family’s values and how physical activity can contribute to these values. This activity aims to highlight the importance of physical activity within the family context and foster a sense of shared purpose, thereby increasing identity salience the importance of the family’s physical activity identity to the individual family members [66]. The BCT applied in this activity is framing/reframing [13.2] [67].

*Workshop 3, Activity #2: Next, the family engages in a creative activity designed to promote a sense of unity and shared identity, such as creating a family team name, family crest, or a family Instagram account focused on physical activity. This activity draws upon the BCTs of identity associated with changed behavior [13.5] and social support [3.1, 3.2, 3.3] [67], fostering a sense of unity and distinctiveness around the family’s physical activity identity. This activity encourages identity fit and contrast - the extent to which the family’s physical activity identity distinguishes them from other families [36, 66].

*Workshop 3, Activity #3: The workshop then moves on to establishing standards for physical activity. The family discusses their expectations for physical activity, determines a reasonable amount of weekly family physical activity, and identifies activities to include in their family physical activity plan. This collaborative process employs the BCTs of discrepancy between current behavior and goal standard [1.6], goal setting (behavior) [1.1], and action planning [1.4] [67], promoting a shared understanding of the family’s physical activity goals and preferences, and promoting identity complementarity - the extent to which family members perceive themselves as similar to, and aligned with each other, in terms of their physical activity identity [68].

*Workshop 3, Activity #4: Problem-solving and brainstorming are then conducted to identify potential barriers to physical activity and develop strategies to overcome them. The family also discusses ways to support each other in changing the routine and recording their physical activity. This activity promotes a sense of shared responsibility and mutual support within the family, further enhancing identity salience. The BCTs applied in this activity are coping planning [1.2], social support [3.2, 3.3], and self-monitoring of behavior [2.3] [67].

*Workshop 3, Activity #5: The family then discusses the roles and responsibilities of each member in the physical activity program. They also identify individual and shared goals and explore ways to combine these goals to foster a sense of unity and family cohesion. The BCTs applied in this activity are goal setting (behavior) [1.1], action planning [1.4], and behavioral contract [1.8] [67].

*Workshop 3, Activity #6: Finally, the family are encouraged to envisions their possible selves as an active family at different time points in the future. This activity utilizes the BCTs of comparative imagining of future outcomes [9.3], framing/reframing [13.2], and identity associated with changed behavior [13.5] [67], and is desiged to reinforces the family’s shared vision and long-term commitment to an active lifestyle. When taken together, by focusing on the development of a shared family identity around PA, Workshop 3 aims to promote long-term adherence to an active lifestyle within the family context through the use of BCTs, the targeting of social identity constructs (that emphasizes a sense of ‘we-ness’ as an active family), and group discussion.

In addition to these intervention materials, the participating parents in the identity promotion condition will receive a digital screen saver for their computer or cellular device with graphics highlighting “We Are an Active Family”. Given the use of phones/digital tools in day-to-day activity, the use of this media will be encouraged for the duration of the study as a prompt for continued engagement in research goals.

Outcome measures

Primary outcome measures

Child MVPA is measured with wGT3X-BT Actigraph accelerometers, recognized as a widely accepted method for physical activity measurement in field settings [69]. These devices have several advantages over proxy-report subjective measures of PA. Accelerometers offer a more objective assessment of PA compared to parent or self-report measures, as they are less susceptible to reporting biases such as recall errors and social desirability [70]. Additionally, accelerometers have been shown to accurately record the short, intermittent bursts of activity that are characteristic of children’s PA patterns, providing a more accurate representation of their true activity levels than subjective measures [70, 71].

Children will wear the devices during waking hours (~ 10 h per day) on a belt around the waist for a for 7 consecutive days. The accelerometer is placed on an elastic belt, and participants are directed to wear it secured snugly around the waist with the device above the left iliac crest. Participants are instructed to remove the accelerometers for water-based activities as they are not waterproof, and a logbook is provided for participants, in most cases parents, to note when the devices were removed for water-based activity or any other reason. This includes noting the time the accelerometer was taken off for sleep, and the time it was put back on in the morning. Additionally, the logbook is to be used to provide other details of each day (e.g. if their routine was changed for any reason and/or what activities they participated in). This information can be used in parallel with the accelerometers to cross-reference the data it presents.

ActiLife software (Version 6.11.9; ActiGraph LLC) will be used to initialize accelerometers, download data, and process the data. The accelerometers are initialized to collect pre-filtered data at a sample rate of 30 Hz for the children and their parents (see secondary outcomes below), and are downloaded into 15-second epochs for children to capture the sporadic nature of their PA [70, 71], and 60-second epochs for parents, consistent with the methodology used by Troiano et al. [72]. For determining valid wear time, the Troiano algorithm is used which defines non-wear time as a period of at least 60 consecutive minutes of zero counts, with an allowance for one to two minutes of counts between 0 and 100. Measurements will take place at baseline, 6 weeks, 3 months, and 6 months (primary endpoint of interest), and MVPA will be evaluated as change from baseline.

Child MVPA will be determined using the Evenson [73] cut points based off of recommendations from Trost et al. [71]. Evenson cut points define moderate activity as 2296–4011 counts per minute (CPM) and vigorous activity as ≥ 4012 CPM. Therefore, MVPA will be any activity ≥ 2296 CPM. The outcome variable will be average minutes per day of children’s MVPA.

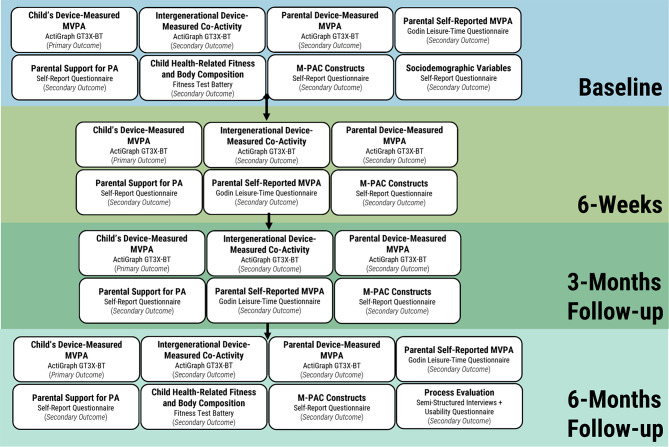

Secondary outcome measures (Fig. 2)

Fig. 2.

Flow Diagram of Outcomes Assessed Throughout the Trial

Parental PA

Parental PA will be measured using accelerometry and self-reported questionnaires at all assessment occasions (baseline, 6 weeks, 3 months and 6 months). Accelerometry will be measured in a similar fashion to the methods outlined above. Namely, parents are instructed to wear the Actigraph wGT3X-BT for 7 days a week (~ 10 h per day), remove it at night and for water-based activities, and note the details of the wear in a logbook. Parental MVPA will be measured using Troiano adult protocol [72]. Activity will be assessed by measuring several variables, including duration (total minutes worn, total movement counts/day, total minutes of sedentary, light, moderate to vigorous day), frequency (bouts of sedentary, light moderate to vigorous/day), and intensity. Non-wear time will be determined using the algorithm from Troiano et al. (2008), and will be subtracted from total wear time. The MVPA of adults will be evaluated as change from baseline and determined using frequently applied cut points [74] validated for adults [72] which classify MVPA as 2020 counts per minutes (CPM) and above.

As a secondary assessment, parents self-report physical activity using the Godin Leisure-Time Exercise Questionnaire [75, 76] at all time points. This questionnaire assesses the frequency of mild, moderate, and strenuous activity performed for at least 15 min during free time in a typical week. A total weekly MVPA score will be calculated by multiplying the frequency by the duration.

Parent-child intergenerational activity

Parent-child intergenerational activity will be measured using self-report with a modified Godin Leisure-Time Exercise Questionnaire (GLTEQ) [15] and accelerometry as discussed in the primary outcome above. Parent accelerometers will be tagged with the child’s accelerometer to assess coordinated activity. The wGT3X-BT accelerometer model has a Bluetooth proximity detection feature that can determine the presence (e.g., same room in a house, at the park together) or absence of close proximity between two accelerometers. The adult accelerometer is programmed to be the “beacon” device, and the child’s accelerometer is programmed as the “receiver”. In this method, “beacon” devices broadcast their serial number and “receiver” devices are set to search for the signal once per minute. The receivers then store a log of proximity detection information, recorded as a received signal strength indicator (RSSI). Every 60 s where the monitors are in close proximity will be “tagged” and recorded in the memory of the child’s monitor, which will be later linked to time-stamped data of the parent. According to ActiGraph [77], accelerometers communicate via Bluetooth when in close proximity indoors, which is a maximum of 10–20 m, and close proximity outdoors, which is a maximum of 100 m. Previous success has been demonstrated by the work of [78] showing 82% sensitivity and 81% specificity for determining the presence of close proximity between parents and preschoolers using the proximity feature [79]. The outcome variable will be average minutes per day parents and children were both engaging in physical activity at the same time while in close proximity.

Child health-related fitness and body composition

Child health-related fitness will assess the key components of body composition, aerobic fitness and musculoskeletal fitness. Body mass (kg), height (cm), body mass index, and waist circumference (cm; at the level of noticeable waist narrowing) will be measured according to standard procedures, and percentage body fat will be estimated using the Tanita TBF-300 A scale. Cardiovascular fitness (i.e., predicted maximal aerobic power) will be assessed following protocol for the modified Canadian Aerobic Fitness Test (mCAFT) standardized in children. Heart rate and blood pressure (sphygmomanometer and a stethoscope) will be monitored at rest and during exercise. All participants will complete the mCAFT step test, which uses one or more 3-min submaximal stepping stage based on the participant’s heart rate response. Musculoskeletal fitness [i.e., muscular (grip) strength, muscular endurance (curl-ups and push-ups), power (vertical jump), and flexibility (sit-and-reach)] will be assessed according to standardized guideline [80]. All tests will be conducted by qualified exercise professionals following the Canadian Society for Exercise Physiology (CSEP) Protocol [81]. The total time required for the health-related physical fitness measurements will be approximately 45 min.

Parental support and M-PAC constructs

Parental support measures are evaluated at all time points (baseline, 6 weeks, 3 months, 6 months) during the study. This includes main behavioral components such as encouragement, logistical support, and intergenerational PA behaviors [13], as well as M-PAC constructs related to parental support of child physical activity [82]. MPAC constructs include parental support identity, habit, PA regulation (proactive, reactive, self-monitoring, social monitoring), perceived capability and opportunity, affective and instrumental attitude, and intention.

Parental support for child physical activity is measured with an adapted 5-point Likert Scale (Strongly disagree <-> Strongly agree) from Davison et al. [83], to assess ways in which parents provide support for their child’s PA. Parents respond to questions like “I go out of my way to enroll my child in sports and other activities that get him/her to be physically active (e.g. After school programs, programs at the YMCA).” and “I often drive or take my child to places where he/she can be active (e.g., parks, playground, sport games or practices).” The scores from this questionnaire have demonstrated good internal consistency reliability, with Cronbach’s α ranging from 0.61 to 0.74 for the logistic support subscale and 0.69 to 0.75 for the modeling subscale [83].

Parent support identity (whether parents identify as being supportive of their child’s physical activity) is measured via a Modified Exercise Identity Scale from Anderson and colleagues [84–86]. Parents are asked if they consider themselves a supportive parent for my child’s physical activity; if when they describe themselves to others, they include their involvement in supporting their child’s physical activity; and if others see them as someone who regularly supports their child’s PA. In prior studies, the modified scale scores assessing parent support identity have demonstrated evidence of internal consistency (e.g., Cronbach’s α = 0.84) and convergent and predictive validity by correlating with measures of personal and family-based physical activity [24, 87].

Parent support of family physical activity identity is measured using a 4-item scale adapted from Doosje et al. [88]. Parents are asked to rate their agreement with the following statements on a 5-point Likert scale: “I identify as an active member of an active family”; “I see myself as an active member of an active family”; “I am pleased to be an active member of an active family”; and “I feel strong ties with my family members around being physically active” [88]. While the original scale by Doosje et al. [88] was designed to measure ingroup identification and has demonstrated good reliability for group identification (Study 1 = Cronbach’s α = 0.83), the current study adapts this scale to measure identification with being part of an active family. As this is a newly adapted scale, reliability and validity data are not yet available. We plan to examine the internal consistency of the scale scores (Cronbach’s α) in our sample, as well as explore the scale scores’ associations with related constructs (e.g., family physical activity levels, parental support behaviors) as preliminary evidence of validity.

Parental support of child physical activity habit is measured with an adapted Self-Reported Habit Strength Index (SRHI) [89], which provides the opportunity to use the self-reported behavioural automaticity index subscale (SRBAI) [90] as well. Parents respond on a five-point scale to questions in the following format: “Regular support of my child’s PA is something I do. automatically, frequently, etc.” The scores from the SRHI have demonstrated good internal consistency reliability (Cronbach’s α = 0.91, p < .001) and convergent validity with measures of past behavior and behavioral frequency [89]. The SRBAI subscale has also shown good internal consistency reliability (Cronbach’s α generally > 0.80) and a strong convergent validity with the SRHI [90].

Physical activity regulation is measured via a modified Physical Activity Regulation Scale (PARS) from Rhodes and Lithopoulos [91]. This instrument measures parent behaviours with regards to tracking and planning child’s physical activity. Parents respond to statements in the following format: “to support my child I made a detailed plan regarding when to support my child’s physical activity”, “I avoid spending long periods of time in environments that do not allow me to support my child’s physical activity” etc. Although this is a relatively new tool, initial evidence suggests that the scores from the PARS have good internal consistency reliability (Cronbach’s α generally > 0.80) and predictive validity with measures of physical activity behavior [91].

Furthermore, an adapted perceived control measure from Lithopoulos et al. [92] evaluates measures of perceived capability and opportunity for parents to support child PA. This measure asks parents their level of agreement of how much control they have to regularly support their child’s physical activity over the next 6 weeks/3months. These are presented as statements in the following format: “I have the physical ability to support my child’s physical activity over the next…”; “I have enough skill to do the activities needed of me to support my child’s physical activity over…”; “I can handle the physical demands supporting my child’s physical activity over…” etc. The scores from this measure have demonstrated good internal consistency (Cronbach’s α > 0.90) and test-retest reliability (Intraclass Correlation Coefficient (ICCs) of 0.79 for perceived opportunity and 0.82 for perceived capability). The measure also showed evidence of discriminant validity, distinguishing itself from related constructs like intentions and attitudes, as indicated by satisfactory model fit indices (Standardized Root Mean Square Residual (SRMR = 0.03); Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA = 0.06)). Additionally, the measure exhibited predictive validity, with perceived capability and opportunity predicting intentions, and perceived capability predicting physical activity [92].

Attitudes toward engaging in supportive parenting behaviours of child PA are measured with items covering both affective and instrumental components [93, 94]. Using a modified 7-point scale this measure assesses to what degree parents find regular support of their child’s physical activity to be enjoyable, wise, exciting, beneficial, useful, and pleasant (e.g., extremely unenjoyable <-> extremely enjoyable, extremely unwise <-> extremely wise, etc.). The scores from this affective and instrumental attitude measure show strong internal consistency (Cronbach’s alpha of > 0.84), and significant (p < .01) correlations of with intention and support child physical activity [24, 25].

Finally, parental support of child PA intention is assessed using Courneya’s recommendation for open-scaled measurement [95]. This instrument asks parents to respond on a 7-point scale from “Extremely Uncommitted” to “Extremely Committed” about how committed they are to regularly supporting their child’s physical activity over the next 6 weeks, aligning with the open-scaled approach [95], and exercise intention measures from Rhodes et al. [96]. They are also asked to quantify in times per week how often they intend to engage in supportive behaviors over the next 6 weeks, similar to measures in Rhodes, Berry, et al. [24]. These questions capture the distinction between decisional intention (direction) and intention strength (commitment) as recommended by [97] for improving measurement, theory testing and intervention practices related to physical activity intentions and behaviors.

Sociodemographic variables

A section of the baseline questionnaire assesses various demographic characteristics including gender, age, ethnicity, level of education, marital status, employment information, household income, and health background.

Exit interview questions

To evaluate participants’ experience with the intervention and gather insights for potential improvements, semi-structured exit interviews are conducted with parents at the 6-month timepoint. The interviews, conducted via video chat by Research Assistants, aim to assess parents’ overall experience, perceived benefits and barriers, satisfaction with the intervention materials and components, and any observed changes or consequences resulting from their participation. The interviews include common questions asked to all parents, as well as group-specific questions tailored to the respective intervention components. Common questions include: “What types of physical activities did you do over the course of the study and how often?”, “Did you use any of the intervention materials/worksheets that were shared with you at these meetings?”, “Were there any barriers to supporting your child’s physical activity?”, and “During the course of the study, did you notice any changes in regards to your relationship with your child, well-being or family functioning?”. Group-specific questions for parents in the identity intervention group ask about how discussions on supportive parent identity and family identity as an active family influenced their motivation and commitment to supporting their child’s physical activity. To control for attention, parents in the planning intervention group, had questions related to the Canadian Food Guide and were asked about how the shared information impacted their understanding and motivation to support healthy eating habits. These questions have proved useful in our prior evaluations [14] and are designed to provide a thorough illustration of the experience and impacts of the different intervention materials.

Analysis strategy

Quantitative process evaluation data analyses

Recruitment and retention rates will be determined, after which the pattern of missing data will be determined [98]. Linear mixed models will then be conducted to determine if condition (0 = education + planning; 1 = education + planning + identity formation) has a differential impact on the children’s MVPA over time. Subsequent models will be conducted that center the linear trend at each time point to determine if a condition effect is also present at a given time point (e.g., at baseline, 6 weeks, 12 weeks or 24 weeks). These analyses will address primary objective #1. The same analytical approach will be used to determine whether there are condition effects on the secondary child fitness outcomes (secondary objective #1). For secondary objective #2, parental support and parental support identity will be treated as time varying covariates to examine their relationships with children’s MVPA over time. Next, if a condition effect is present for the children’s MVPA, analyses will be conducted to determine if the parental support / parental support identity variables mediate the condition / children’s MVPA relationship. Finally, exploratory analyses will be conducted to examine potential intergenerational, sex and seasonal influences on the children’s MVPA over time.

Qualitative process evaluation data analyses

Participants will be invited to participate in exit interviews designed to elicit in-depth information about the quality of processes embedded within the program [99]. This will draw from a qualitative social constructionist perspective [100] to understand in the parents’ own words, the beneficial features and any problematic components of the intervention. Data collected via the semi-structured interviews will be analyzed through use of inductive content analytic procedures [101], through use of the NVivo software program, and themes will be identified that correspond to the strengths and limitations of the intervention program. The response themes will also be linked at the individual level, so post-hoc assessment of successful and unsuccessful interventions can be examined by these responses.

Discussion

This protocol describes the implementation of a randomized trial investigating the efficacy of planning and identity interventions aimed at increasing parent-child co-activity and parent support behaviours. This research is conceptually guided by the M-PAC framework [82] and has important implications for promoting children’s physical activity. By explicitly targeting and fostering parents’ “physical activity support identity” - their self-categorization as a parent who actively supports their child’s physical activity engagement - this study addresses a key yet understudied influence on child physical activity behaviors in intervention research. If successful, the findings could inform the development of more effective family-based interventions that have the potential to create more sustainable changes in child physical activity behaviours and ultimately contribute to improved health outcomes.

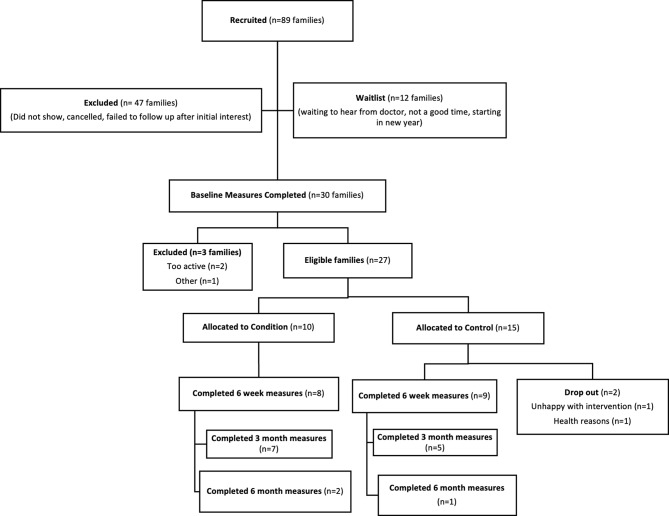

To date, we have obtained ethical approval, registered the trial, and have initiated recruitment and enrolledment efforts. Our recruitment strategies include targeted social media advertisements, distribution of flyers in community centers and schools, and outreach to local pediatricians and family health clinics. Through these efforts, we have generated interest from 50 families in the Greater Victoria region, 25 families in the Greater Vancouver region, and 14 families in the Greater Nanaimo region. From those expressing interest, 30 families have been assessed for eligibility based on our inclusion criteria of having a child aged 6–12 years old, being able to commit to the study requirements, and not having any medical conditions that would preclude participation in physical activity. Of these, 27 families have been deemed eligible and have completed all baseline measures, 25 are active families following two family drop-outs, and 12 are on a waitlist to begin baseline eligibility measures (see Fig. 3 for Participant Flow Diagram). The study is ongoing, and based on our current rate of recruitment, which averages 4 new interested families per week across all regions, we anticipate meeting our target sample size and completing recruitment by January 2026. We will continue to monitor recruitment progress and adjust our strategies as needed to ensure timely completion of the study.

Fig. 3.

Flow Diagram of Participant Recruitment

Our team has established scientific dissemination records and ongoing and long-standing knowledge exchange connections with international (e.g., International Society for Physical Activity and Health (ISPAH), International Society for Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity (ISBNPA), International Society of Behavioral Medicine (ISBM), WHO), national (e.g., ParticipACTION, Public Health Agency of Canada) and provincial (Ministry of Health, BC Healthy Living Alliance) organizations. Should our results support our hypotheses, we will leverage the relationships established through this network to establish a project advisory committee that includes the relevant policy-makers, child service providers and parents for the subsequent scale-up project and mobilization of study findings. This will ensure that our research findings are translated into practical recommendations and resources that can be integrated into existing programs and services to maximize their impact on child physical activity promotion.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Abbreviations

- BCT

Behaviour Change Technique

- CI

Confidence Interval

- CONSORT

Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials

- CPM

Counts per Minute

- CSEP

Canadian Society for Exercise Physiology

- GLTEQ

Godin Leisure-Time Exercise Questionnaire

- HREB

Human Research Ethics Board

- ICC

Intraclass Correlation Coefficient

- ISPAH

International Society for Physical Activity and Health

- ISBNPA

International Society for Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity

- ISBM

International Society of Behavioral Medicine

- KT

Knowledge Translation

- mCAFT

Modified Canadian Aerobic Fitness Test

- M

PAC-Multi-Process Action Control Framework

- MVPA

Moderate-to-Vigorous Physical Activity

- PARS

Physical Activity Regulation Scale

- ParQ+

Physical Activity Readiness Questionnaire for Everyone

- REBC

Research Ethics Board of BC

- RISe

Research and Information Systems

- RMSEA

Root Mean Square Error of Approximation

- RSSI

Received Signal Strength Indicator

- SRBAI

Self-Reported Behavioural Automaticity Index

- SRHI

Self-Reported Habit Strength Index

- SRMR

Standardized Root Mean Square Residual

- SPIRIT

Standard Protocol Items: Recommendations for Interventional Trials

- UBC

University of British Columbia

- UVic

University of Victoria

- VIU

Vancouver Island University

- WHO

World Health Organization

Author contributions

ES and RER contributed to the conception and design of the study. ES and RER drafted the manuscript. MB, KS, CM, VC, SS, LV, and SC reviewed the paper and approved the final submission. RER is responsible for project oversight.

Funding

This project is funded by Diabetes Canada Grant (OG-3-22-5649-RR). The funding body had no role in the design, data collection, or reporting associated with this study.

Data availability

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study protocol was approved by the University of Victoria Human Research Ethics Board (Victoria, Canada) reference number 23 − 0022. Informed consent is obtained from all participants before study enrolment.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Ahn JV, Sera F, Cummins S, Flouri E. Associations between objectively measured physical activity and later mental health outcomes in children: findings from the UK Millennium Cohort Study. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2018;72:94–100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Biddle SJH, Ciaccioni S, Thomas G, Vergeer I. Physical activity and mental health in children and adolescents: an updated review of reviews and an analysis of causality. Psychol Sport Exerc. 2019;42:146–55. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Donnelly JE, et al. Physical activity, fitness, cognitive function, and academic achievement in children: a systematic review. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2016;48:1197–222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Janssen I, LeBlanc AG. Systematic review of the health benefits of physical activity and fitness in school-aged children and youth. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2010;7:40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Poitras VJ, et al. Systematic review of the relationships between objectively measured physical activity and health indicators in school-aged children and youth. Appl Physiol Nutr Metab Physiol Appl Nutr Metab. 2016;41:S197–239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jones RA, Hinkley T, Okely AD, Salmon J. Tracking physical activity and sedentary behavior in childhood: a systematic review. Am J Prev Med. 2013;44:651–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.World Health Organization. Global Health Observatory (GHO) data: prevalence of insufficient physical activity; 2016. https://www.who.int/data/gho/data/indicators/indicator-details/GHO/prevalence-of-insufficient-physical-activity-among-school-going-adolescents-aged-11-17-years. Accessed 20 Mar 2024.

- 8.Roberts KC, et al. Meeting the Canadian 24-Hour Movement Guidelines for Children and Youth. Health Rep. 2017;28:3–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chaput J-P, et al. Proportion of preschool-aged children meeting the Canadian 24-Hour Movement guidelines and associations with adiposity: results from the Canadian Health measures Survey. BMC Public Health. 2017;17:147–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rhodes RE, et al. Development of a consensus statement on the role of the family in the physical activity, sedentary, and sleep behaviours of children and youth. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2020;17:74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Beets MW, Cardinal BJ, Alderman BL. Parental social support and the physical activity-related behaviors of youth: a review. Health Educ Behav off Publ Soc Public Health Educ. 2010;37:621–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Brown HE, et al. Family-based interventions to increase physical activity in children: a systematic review, meta-analysis and realist synthesis. Obes Rev off J Int Assoc Study Obes. 2016;17:345–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pyper E, Harrington D, Manson H. The impact of different types of parental support behaviours on child physical activity, healthy eating, and screen time: a cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health. 2016;16:568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rhodes RE, Blanchard CM, Quinlan A, Naylor P-J, Warburton DE. R. Family Physical Activity Planning and Child Physical Activity outcomes: a Randomized Trial. Am J Prev Med. 2019;57:135–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rhodes RE, Naylor P-J, McKay HA. Pilot study of a family physical activity planning intervention among parents and their children. J Behav Med. 2010;33:91–100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rhodes RE, Perdew M, Malli S. Correlates of parental support of child and youth physical activity: a systematic review. Int J Behav Med. 2020;27:636–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rhodes RE, et al. Couple-based physical activity planning for New Parents: a Randomized Trial. Am J Prev Med. 2021;61:518–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dunton GF, et al. Towards consensus in conceptualizing and operationalizing physical activity maintenance. Psychol Sport Exerc. 2022;61:102214. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rhodes RE, Sui W. Physical activity maintenance: a critical narrative review and directions for Future Research. Front Psychol. 2021;12:725671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rhodes RE. Multi-process action control in physical activity: a primer. Front Psychol. 2021;12:797484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rhodes RE, Janssen I, Bredin SSD, Warburton DER, Bauman A. Physical activity: Health impact, prevalence, correlates and interventions. Psychol Health. 2017;32:942–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Conner M, Norman P. Predicting and changing health behaviour: a social cognition approach. Predict Chang Health Behav Res Pract Soc Cogn Models. 2015;3:1–29. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rhodes RE, Yao CA. Models accounting for intention-behavior discordance in the physical activity domain: a user’s guide, content overview, and review of current evidence. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2015;12:9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rhodes RE, et al. Application of the Multi-process Action Control Framework To Understand Parental Support of Child and Youth Physical Activity, Sleep, and Screen Time Behaviours. Appl Psychol Health Well-Being. 2019;11:223–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rhodes RE, et al. Understanding action control of parental support behavior for child physical activity. Health Psychol off J Div Health Psychol Am Psychol Assoc. 2016;35:131–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tanna S, Arbour-Nicitopoulos K, Rhodes RE, Bassett-Gunter R. A pilot study exploring the use of a telephone-assisted planning intervention to promote parental support for physical activity among children and youth with disabilities. Psychol Sport Exerc. 2017;32:25–33. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Grant SJ, et al. Parents and children active together: a randomized trial protocol examining motivational, regulatory, and habitual intervention approaches. BMC Public Health. 2020;20:1436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Medd ER, et al. Family-based habit intervention to promote parent support for child physical activity in Canada: protocol for a randomised trial. BMJ Open. 2020;10:e033732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Quinlan A, Rhodes RE, Blanchard CM, Naylor P-J, Warburton D. E. R. Family planning to promote physical activity: a randomized controlled trial protocol. BMC Public Health. 2015;15:1011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Beauchamp MR. Promoting Exercise Adherence through groups: a self-categorization theory perspective. Exerc Sport Sci Rev. 2019;47:54–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Burke J, P., Stets E. J. Identity theory. Oxford University Press USA; 2009.

- 32.Rhodes RE, et al. Enacting physical activity intention: multi-process action control. In: Englert C, Taylor I, editors. Self-Regul Motiv Sport Exerc. Taylor & Francis; 2021. pp. 8–20.

- 33.Stryker S, Burke PJ. The past, present, and future of identity theory. Soc Psychol Q. 2000;63:284–97. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tajfel H, Turner JC. The Social Identity Theory of Intergroup Behavior. In: Worchel S, Austin WG, editors. Psychology of Intergroup Relation. Chicago: Hall; 1986. pp. 7–24. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rees T, Alexander Haslam S, Coffee P, Lavallee D. A social identity approach to sport psychology: principles, practice, and prospects. Sports Med. 2015;45:1083–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Turner JC, Hogg MA, Oakes PJ, Reicher SD, Wetherell MS. Rediscovering the social group: a self-categorization theory. Basil Blackwell; 1987.

- 37.Abrams D, Hogg MA. Social identifications: a Social Psychology of Intergroup Relations and Group processes. Routledge; 2006.

- 38.Hollman H, Sui W, Rhodes RE. A feasibility randomized controlled trial of a multi-process action control web-based intervention that targets physical activity in mothers. Women Health. 2022;62:384–401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Husband CJ, Wharf-Higgins J, Rhodes RE. A feasibility randomized trial of an identity-based physical activity intervention among university students. Health Psychol Behav Med. 2019;7:128–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.McEwan D, Rhodes RE, Beauchamp MR. What happens when the party is over? Sustaining physical activity behaviors after intervention cessation. Behav Med. 2022;48:1–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rhodes RE, et al. Predicting the physical activity of new parents who participated in a physical activity intervention. Soc Sci Med. 2021;284:114221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rhodes RE, Quinlan A, Naylor P-J, Warburton DE, Blanchard CM. Predicting personal physical activity of parents during participation in a family intervention targeting their children. J Behav Med. 2020;43:209–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Chan A-W, et al. SPIRIT 2013 statement: defining standard protocol items for clinical trials. Ann Intern Med. 2013;158:200–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Schulz KF, Altman DG, Moher D. CONSORT 2010 statement: updated guidelines for reporting parallel group randomised trials. J Pharmacol Pharmacother. 2010;1:100–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wright CE, Rhodes RE, Ruggiero EW, Sheeran P. Benchmarking the effectiveness of interventions to promote physical activity: a metasynthesis. Health Psychol off J Div Health Psychol Am Psychol Assoc. 2021;40:811–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Rhodes RE. Translating physical activity intentions into regular behavior is a consequence of reflective, regulatory, and reflexive processes. Exerc Sport Sci Rev. 2024;52:13–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Yao CA, Rhodes RE. Parental correlates in child and adolescent physical activity: a meta-analysis. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2015;12:10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Tremblay MS, et al. Canadian 24-Hour Movement Guidelines for Children and Youth: an integration of physical activity, sedentary Behaviour, and Sleep. Appl Physiol Nutr Metab. 2016;41:S311–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Warburton DE, Jamnik VK, Bredin SS, Gledhill N. The physical activity readiness questionnaire for everyone (PAR-Q+) and electronic physical activity readiness medical examination (ePARmed-X+). Health Fit J Can. 2011;4:3–17. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Dumas JE, Lynch AM, Laughlin JE, Smith EP, Prinz RJ. Promoting intervention fidelity: conceptual issues, methods, and preliminary results from the EARLY ALLIANCE prevention trial. Am J Prev Med. 2001;20:38–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hagger MS, et al. Implementation intention and planning interventions in health psychology: recommendations from the synergy expert group for research and practice. Psychol Health. 2016;31:814–39. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 52.Rhodes RE, Grant S, de Bruijn G-J. Planning and implementation intention interventions. The handbook of behavior change. New York, NY, US: Cambridge University Press; 2020. pp. 572–85. 10.1017/9781108677318.039. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Schwarzer R. Modeling Health Behavior Change: how to predict and modify the Adoption and Maintenance of Health Behaviors. Appl Psychol. 2008;57:1–29. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Sui W, Hollman H, Magel E, Rhodes RE. Increasing physical activity among adults affected by COVID-19 social distancing restrictions: a feasibility trial of an online intervention. J Behav Med. 2024;47:886–99. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 55.Locke EA, Latham GP. A theory of goal setting & Task Performance. Prentice-Hall, Inc; 1990.

- 56.Prestwich A, Lawton R, Conner M. The use of implementation intentions and the decision balance sheet in promoting exercise behaviour. Psychol Health. 2003;18:707–21. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Sniehotta FF, Scholz U, Schwarzer R. Bridging the intention–behaviour gap: planning, self-efficacy, and action control in the adoption and maintenance of physical exercise. Psychol Health. 2005;20:143–60. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Sniehotta FF, Scholz U, Schwarzer R. Action plans and coping plans for physical exercise: a longitudinal intervention study in cardiac rehabilitation. Br J Health Psychol. 2006;11:23–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Strecher VJ, et al. Goal setting as a strategy for health behavior change. Health Educ Q. 1995;22:190–200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Health Canada. Canada’s food guide: healthy eating resources. https://food-guide.canada.ca/en/healthy-eating-resources/. Accessed 1 Mar 2023.

- 61.Burke PJ. Identity change. Soc Psychol Q. 2006;69:81–96. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Kendzierski D, Morganstein MS. Test, revision, and cross-validation of the physical activity self-definition model. J Sport Exerc Psychol. 2009;31:484–504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Cox A, Rhodes R. Increasing physical activity in empty nest and retired populations online: a randomized feasibility trial protocol. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17:3544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Steffens NK, Fransen K, Haslam SA. Leadership. In: Haslam SA, Fransen K, Boen F, editors. The new psychology of sport and exercise: the social identity approach. Thousand Oaks: Sage; 2020. pp. 41–58. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Carron AV, Widmeyer WN, Brawley LR. The development of an instrument to assess cohesion in Sport teams: the Group Environment Questionnaire. J Sport Psychol. 1985;7:244–66. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Oakes PJ, Haslam SA, Turner JC. Stereotyping and social reality. Blackwell Publishing; 1994.

- 67.Michie S, et al. The behavior change technique taxonomy (v1) of 93 hierarchically clustered techniques: building an international consensus for the reporting of behavior change interventions. Ann Behav Med. 2013;46:81–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Haslam SA, Oakes PJ, Turner JC. Social identity, self-categorization, and the perceived homogeneity of ingroups and outgroups: The interaction between social motivation and cognition. (1996).

- 69.Esliger DW, Tremblay MS. Physical activity and inactivity profiling: the next generation. Appl Physiol Nutr Metab. 2007;32:S195–207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Cain KL, Sallis JF, Conway TL, Van Dyck D, Calhoon L. Using accelerometers in youth physical activity studies: a review of methods. J Phys Act Health. 2013;10:437–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Trost SG, McIver KL, Pate RR. Conducting accelerometer-based activity assessments in field-based research. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2005;37:S531–43. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 72.Troiano RP, et al. Physical activity in the United States measured by accelerometer. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2008;40:181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Evenson KR, Catellier DJ, Gill K, Ondrak KS, McMurray RG. Calibration of two objective measures of physical activity for children. J Sports Sci. 2008;26:1557–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Migueles JH, et al. Accelerometer data collection and processing criteria to assess physical activity and other outcomes: a systematic review and practical considerations. Sports Med. 2017;47:1821–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Godin G, Jobin J, Bouillon J. Assessment of leisure time exercise behavior by self-report: a concurrent validity study. Can J Public Health Rev Can Sante Publique. 1986;77:359–62. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Godin G, Shephard RJ. A simple method to assess exercise behavior in the community. Can J Appl Sport Sci J Can Sci Appl Au Sport. 1985;10:141–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]