Abstract

Biomimicry applications in different domains, from material science to technology, have proven to be promising in inspiring innovative solutions for present-day challenges. However, biomimetic applications in the built environment face several barriers including the absence of biological knowledge of architects and planners and the lack of an adequate common means to transfer biomimetic concepts into strategies applicable in the urban context. This review aims to create a multidimensional relational database of biomimetic strategies from successful precedent case studies in the built environment across different city systems and on different application scales. To achieve this, a thorough systematic search of the literature was implemented to map relevant biomimetic case studies, which are analyzed to extract biomimetic strategies that proved to be applicable and successful in an urban context. These strategies are then classified and documented in a relational database. This will provide a guide for architects and planners on how to transfer biomimetic strategies to strategies applicable in the urban context, thus bridging the gap of their lack of biological knowledge. The resulting matrix of strategies provides potential strategies across most of the different city systems and scales with few exceptions. This gap will be covered in a future work, currently in progress, to expand the database to include all city systems and scales.

Keywords: biomimicry, sustainability, built environment, energy efficiency, resource efficiency

1. Introduction

While cities represent just 3% of the Earth’s surface, they house over half of the world’s population, consume about 70% of global resources including energy resources, and account for three-quarters of the total greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions. These numbers are expected to worsen further since, according to a report by the United Nations, approximately two-thirds of the world’s population will move to urbanized areas by 2050 [1]. There is a need for rapid urbanization to meet the demands of the booming population worldwide, but at the same time, continuing down this path poses a huge threat to the environment, and as cities grow faster, they become more complex and harder to govern sustainably.

Cities have long been viewed as living organisms that require food to survive and that produce waste in a linear, non-cyclic process. Similarly, the urban metabolism in cities is linear, requires extensive energy, and produces waste. In the quest to rectify this, concepts of sustainability and eco-efficiency have emerged, but their application rather focuses on parts or elements in the built environment in isolation and attempts to improve them. This current thinking pattern turns a blind eye to the complex nature of cities with their many constituent systems and elements that affect one another and would, therefore, only provide approximate simplistic and reductionist solutions [2,3] instead of comprehensive solutions to environmental sustainability that will consider these complexities.

Therefore, a shift in mindset is needed to change the model by which cities are designed to a model of similar complexity and time-tested successes—nature. This is what biomimicry tries to achieve [4]. A breakdown of how natural ecosystems manage energy, water, and materials could provide insights into how cities can sustainably manage these resources, which sometimes require trade-offs within the system for the greater good.

This paper is a systematic review that focuses on applications of biomimetic strategies in the built environment—where nature’s organisms, processes, or ecosystems are mimicked in architectural and urban design—and the potential to present a novel approach for designing built environments to be truly sustainable or regenerative. The database collected and analyzed through this study and the ontology used to create relationships between the various examples will provide a valuable tool for city stakeholders, designers, and urban planners to create sustainable and resilient city systems.

2. Aim and Objectives

This paper aims to create a database that includes a selection of biomimetic strategies, based on patterns found in nature, from case studies in the built environment, which has a high potential of being useful to wider built environment applications. This review of the literature will help designers by increasing awareness of some specific applications and examples and categorizing them across scales, city systems, and biomimicry levels.

Accordingly, this study adopts the following objectives:

-

-

A systematic review of previous literature identifying applications of biomimicry in the built environment is carried out.

-

-

The most promising selected strategies and case studies of prior applications of biomimicry are assessed and ranked.

-

-

A select database of biomimetic strategies is created and classified.

3. Background

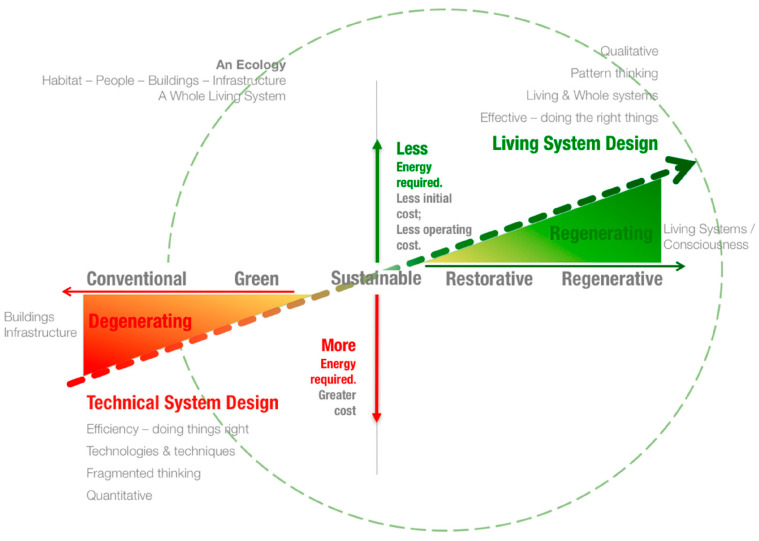

The following sub-sections set out the definition of some high-level terms used in this systematic literature review. Figure 1 summarizes approaches to sustainability in the form of a line graph, where the differences in terms of impact can be seen from degenerating to regenerative, and also shows the energy required to carry out certain approaches, with less energy used being positive on the y-axis. The current conventional practices of sustainability lie on the degenerative side of the graph and are net energy users. This section discusses some more regenerative approaches to sustainability.

Figure 1.

Trajectory of Ecological Design. Adapted with permission from reference [5].

3.1. Regenerative Sustainability

Regenerative sustainability is about creating built environments that regenerate ecosystems and enable communities to thrive without ongoing intervention. It is a shift from a human-only oriented design that focuses on efficiency to a systems approach that acknowledges humans as an integral part of an ecosystem. Regenerative development aims to improve ecological health rather than degrade it and uses place-based, integrative, and participatory design methods to ensure significant community health and well-being benefits. A systems-based approach is crucial to regenerative development, allowing, for example, mutually beneficial interactions between the built environment, the living world, and human inhabitants over time.

The main challenges in implementing regenerative development are the current lack of an integrated approach and the scarcity of completed examples to provide quantifiable evidence of the benefits of regenerative built environments [6]. Regenerative design is described as “building capacity not things” where buildings are designed as systems that interact with each other, the living world, and their human inhabitants rather than as objects [5]. Leading thinkers on regenerative design argue that a shift from a built environment that ultimately degrades ecosystems to one that restores local environments and regenerates the capacity for ecosystems to thrive will require a fundamental rethinking of not just the architectural design [7] but also, as Hunt points out, rethinking the present competitive economic landscape of the built environment [8].

As explained in Table 1 below, despite the numerous benefits of a regenerative approach over conventional and eco-efficient approaches, it is faced with the challenge of its lack of compatibility with the current status quo and business-as-usual mindset.

Table 1.

Benefits of eco-efficient and regenerative design. Source: [7].

| Conventional | Eco-Efficiency | Regeneration | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Works within the existing mindset | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Minimizes environmental impact | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Enhances people’s physical well-being | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Boosts psychological health | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Reduces overall lifecycle costs | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Enhances economic value in projects | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Fosters innovation in projects | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Yields positive environmental outcomes | ✓ | ||

| Transforms development into a potential income source | ✓ | ||

| Manages global issues strategically via place-based approaches | ✓ | ||

| Improves integrated knowledge of place | ✓ | ||

| Promotes mutually beneficial relationships between people and place | ✓ | ||

| Enhances resilience, flexibility, and adaptability in built environments | ✓ | ||

| Strengthens equitable communities | ✓ |

√: benefits.

3.2. Urban Resilience

The concept of resilience has a rich history across engineering, psychology, and disaster literature [9]. While various scholars have contributed to its development, ecologist C.S. Holling’s seminal paper in 1973 [10] is often regarded as the origin of modern resilience theory. Holling challenged the traditional ecological stability paradigm by recognizing ecosystems as dynamic and having multiple stable states. Resilience, according to Holling, describes an ecological system’s ability to persist and function even when altered without necessarily remaining unchanged [11,12,13].

Cities, like ecosystems, are not static and continuously evolve due to a variety of internal and external pressures (e.g., population growth, environmental changes, economic shifts, and technological advances. Urban resilience refers to the capability of an urban system, including its socio-ecological and socio-technical networks, to perform the following: 1. Maintain or rapidly return to desired functions after disturbances (e.g., natural disasters, social disruptions); 2. Adapt to ongoing changes (e.g., climate shifts); 3. Swiftly transform systems that currently limit adaptive capacity or hinder future resilience. This does not mean maintaining a status quo since cities (as in Holling’s resilience model) constantly undergo transformations [10].

Cities, being complex systems, require holistic approaches that consider interconnections among various domains. For example, a shock to the transportation system can affect economic productivity, social mobility, and even access to essential services. Therefore, planning for urban resilience must account for these interdependencies to ensure the city can withstand and adapt to disruptions while maintaining or quickly regaining desired functions even if the city’s structure or functions change. In this context, urban resilience serves as a boundary object, bridging expertise from multiple disciplines and stakeholders [14]. Therefore, implementing urban resilience involves diverse stakeholders with varying motivations, power dynamics, and trade-offs. Moreover, spatial and temporal scales play a crucial role in shaping resilience strategies [15]. This perspective means that urban planners should plan for adaptability, for the potential of transformation in ways that embrace change rather than merely resist it. This could mean rethinking urban infrastructure or governance models in the context of the interconnectedness of city systems [16].

3.3. City Systems and Flows

Globalization connects cities with distant places through material, energy, and capital exchanges [17,18]. This is mainly through trade and the movement of goods, fuel, and capital between distant cities. Nonetheless, each city in itself is a dynamic place where human and natural processes interact, forming urban ecosystems [19,20,21]. Cities can, therefore, be thought of as complex systems composed of interconnected subsystems [22].

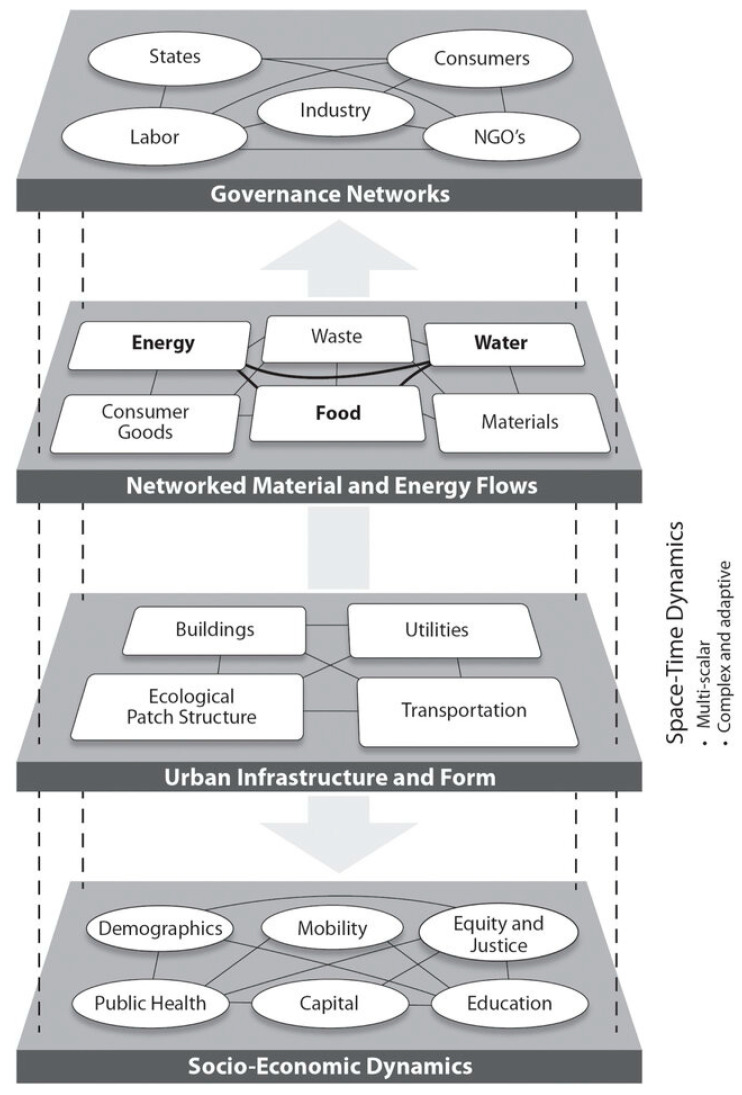

City systems consist of four subsystems [10,21]:

The physical built environment or the urban infrastructure and buildings: Built environment, transportation, energy, water grids, and green spaces.

Networked material and energy flows, also referred to as “metabolic flows”: These include water, energy, food, materials, waste, and consumer goods.

Governance Networks: Actors and institutions shaping urban decisions such as consumers, NGOs, labor, industry, and the state.

Socioeconomic Dynamics: Social aspects influencing urban resilience like demographics, mobility, public health, capital, education, equity, and justice.

Figure 2 provides a heuristic for understanding the intricate structures and dynamics of these urban systems [16]. The figure illustrates this concept of multilevel networks within the mentioned city systems. However, conventional design and governance often treat these subsystems as separate silos. This is due to the increasing specialization within the construction industry, which hinders holistic city-system interconnectivity. Transdisciplinary solutions require changes in city powers, cooperation, and mindset adaptation [10].

Figure 2.

A simplified conceptual schematic of the multilevel networks within the city system. Reprinted with permission from reference [16].

These subsystems interact at various scales (spatial and temporal), emphasizing interconnections [23,24,25]. For instance, by investing in wind turbines and biomass energy, a city can reduce its carbon footprint and improve air quality. This shift can also influence other systems, such as reducing the load on healthcare due to fewer respiratory issues from air pollution and encouraging economic growth in green technology sectors. Similarly, a well-functioning transportation system allows labor to commute easily, and it facilitates the movement of goods and services, thus increasing productivity and capital. Understanding such spatial and temporal interactions across networks is crucial for designing resilient cities. To comprehensively assess urban resilience, all these subsystems and their elements must be considered. This helps decision-makers think through the complexities involved in managing cities effectively.

3.4. What Is Biomimicry?

The term biomimicry was coined in 1997 by Janine Benyus. Biomimicry is from the Greek words “bios”, meaning “life”, and “mimesis”, meaning to “imitate”. Benyus, who is a biologist and a writer, defines it as “a new discipline that studies nature’s best ideas and then imitates these designs and processes to solve human problems” [4]. She explains that the field is grounded in the principles of ecological thinking and sustainability, where nature-inspired solutions are not only efficient but also have a low environmental impact.

Biomimicry has been adopted in a wide range of fields, from robotics and engineering to medicine and material science. Between each of these fields, the definition of biomimicry varies greatly. This is perhaps why Pederson Zari notes that there is no clear definition of biomimicry that architects could apply in designing their projects, and therefore, it is best to focus on analyzing the different approaches to biomimicry to come out with the best methods to apply biomimicry for maximum benefit [26]. Guber, on the other hand, defined biomimicry as “the study of overlapping fields of biology and architecture that show innovative potential for architectural problems” [27].

3.5. Levels of Biomimicry?

According to Benyus and Zari, there are three levels of biomimicry [28]. Firstly, if an organism’s form is mimicked, this is Organism level biomimicry. An example of this is the Lotusan paint, where the nanostructure of the lotus leaf’s surface was mimicked to create an engineered paint with similar surface properties that allow the paint to self-clean when subjected to the rain in a similar manner to the lotus leaves. The second level is behavior-level biomimicry, where an organism’s behavior or process is mimicked in design. This was the case with the Eastgate building in Zimbabwe, where the architect mimicked the way termites passively ventilated their mounds and created a similar ventilation mechanism that reduced the energy needed for artificial ventilation. Lastly, ecosystem-level biomimicry is when a design holistically mimics an entire ecosystem, including the complex links that relate to its components. HOK’s Lavasa masterplan proposal is an example of this level of biomimicry, where the hydrological cycle and the forest were analyzed and mimicked in the design of the buildings, landscape, and roads to create a city with minimum surface runoff and reducing the risk of flooding. The urban surfaces were designed to be permeable like a forest floor, while the buildings’ roof design was multilayered like a forest canopy to retain and re-evaporate rainwater back into the atmosphere. This is besides onsite rainwater collection and wastewater treatment and reuse for landscape irrigation. The latter, although seen as the ultimate goal, was, until lately, considered the most difficult form of biomimicry.

Kibert (2006) suggested that the complexity in understanding ecosystems makes it impossible for designers to engage in modeling ecosystems in their work since, according to Kibert, human designs are insufficiently complex. However, Zari argues otherwise. Zari defends that the ever-increasing knowledge about nature would enable us to mimic the complex relationships in ecosystems to increase the sustainability of the built environments [29].

There could be overlaps between the various levels of biomimicry, as are evident in the case studies handled in this review. For instance, several systems that relate to each other, such as in an ecosystem, are part of an ecosystem-level biomimicry. At the same time, the components of those systems may be modeled after organisms or their behavior in a similar way that a forest ecosystem is home to many interrelated organisms [26].

3.6. Nature’s Approach to Sustainable Design

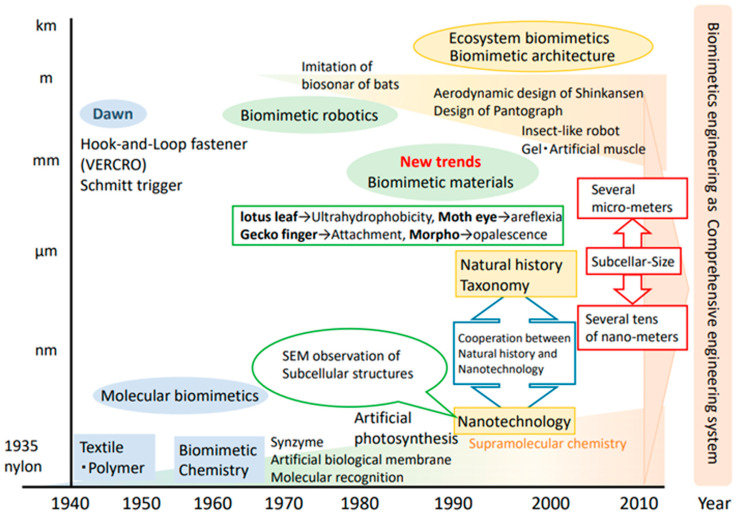

Biomimicry involves applying nature’s design principles to human design. These principles were identified by Benyus [4] and were later refined by the Biomimicry Institute to include the use of only the energy needed, recycling of all materials, resilience to disturbances, optimization rather than maximization, reward for cooperation, use of information, use of safe chemistry and materials, use of abundant resources, being locally attuned and responsive, and using shape to determine functionality [30]. It is argued that the application of these principles in human designs would make these designs biomimetic; they would be sustainable and behave in a way similar to nature’s resilient designs. The concept of biomimicry can be applied to address challenges across various scales [31,32]. In built environment applications, this approach extends from the nanostructure of building materials to entire buildings and even urban areas that extend kilometers [33] (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Historical trend of biomimicry across scales. Source [34].

3.7. Biomimicry in the Built Environment: Current State of Research

Although the approach of the application of biomimetic strategies is promising to reach regenerative built environments, the application of biomimicry in the built environment faces several challenges, according to various scholars. Firstly, there is a lack of a consistent and clear definition of biomimicry, which poses a challenge to understanding the implications of applying its abstract concepts [35]. Secondly, there is a gap in the availability of applicable methodologies to aid its incorporation into architectural and urban design [2,36]. Thirdly, there is a main concern that biological knowledge is not commonly accessible to architects and urban planners, which discourages them from trying to incorporate biomimicry in their designs [2]. This has led some scholars to suggest having a biologist on the design team in the early stages of the design process. Lastly, even if designers were aware of biological concepts, there are further knowledge barriers to transferring these concepts into designs and technologies that would be applicable within the built environment [33,37]. Although the awareness of the potential of biomimicry is increasing, it is still far from being common practice.

3.8. Contribution of the Study

This study is not concerned with providing a definition for biomimicry in the urban context. However, this paper is focused on addressing and bridging the rest of the gaps presented in the previous section by reviewing and selecting biomimetic strategies with high potential for their application to solve built environment problems. This study is focused on the mapping of successful precedent cases of the applications of biomimicry in the built environment on different scales. An analysis of the biomimetic strategies used and transferred to urban applications could overcome the barriers to the transferability of biomimetic concepts and bridge the gap of the lack of biological knowledge of architects and planners.

The classification and ontology presented in this study hope to offer a methodology for the comprehensive application of biomimicry in the built environment on various scales and across different city systems. For this purpose, different application scales were considered that varied from macro-scale, which this review refers to as urban scale, which includes applications of biomimicry on a scale larger than a building like a neighborhood, district, or even a city. This would be the scale that city planners or urban designers address in their designs. The second scale is the scale of a single building. This scale addresses the field of work of an architect. The final micro-scale is the scale of a building component or a building system within a building.

4. Materials and Methods

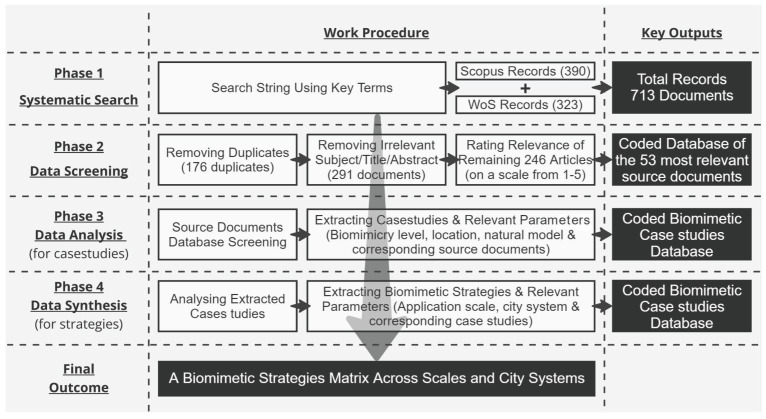

This review adopts an exploratory and analytic research methodology in an attempt to clarify the potential that lies in adopting biomimicry strategies to enable environmentally sustainable cities. The research follows a qualitative research design, which involves the collection and analysis of non-numerical data. The study starts with a systematic review approach where relevant scientific literature is reviewed, and appropriate case studies are analyzed. From this literature, biomimetic strategies are extracted to create a database of those that are most applicable in the built environment field. The review has been conducted in four phases.

First, a systematic search is conducted to identify literature that studies applications of biomimicry in the built environment. Second, a screening process filters the results of the literature search according to the inclusion and exclusion criteria. Third, relevant case studies of prior applications of biomimicry from the chosen literature are collected and analyzed. Finally, a database of biomimetic, environmental, and sustainability strategies is created and classified according to application scale and relevant city system(s). The flowchart (Figure 4) summarizes the following four phases of this paper.

Figure 4.

Process of systematic literature review. Source: designed by the author using Miro.

4.1. Phase 1: Data Collection

First, a comprehensive search of the literature was carried out using SCOPUS and Web of Science. The inclusion criterion was as follows:

-

-

Literature search only using Web of Science and Scopus (Google Scholar was dismissed due to an anomaly in results, which produced an excessive number of irrelevant results);

-

-

The combination of keywords as specified below in Table 2;

-

-

Language: English;

-

-

Published after 1997, when the term biomimicry was coined by Janine Benyus;

-

-

Only peer-reviewed articles, conference papers, reviews, and books were selected, not magazine articles.

Table 2.

Literature search parameters.

| Key terms |

|

| Search string used | TITLE-ABS-KEY ((“biomimetic” OR “biomimicry” OR “nature-inspired”) AND (“built environment” OR “architecture” OR “urban” OR “cities” OR “Buildings”) AND (“sustainable” OR “sustainability” OR “resilient”)) |

| Inclusion criteria |

|

| Exclusion criteria |

|

4.2. Phase 2: Data Screening

The results gathered during phase 1 were filtered using the following processes applied iteratively and in the following order:

-

-

Titles and authors were arranged in a spreadsheet, allowing for sorting.

-

-

Duplicates were identified and removed.

-

-

Irrelevant documents according to title were removed.

-

-

At this stage, abstracts were reviewed, and irrelevant documents were removed according to their abstracts.

The remaining documents were read and graded on relevance. The relevance scale was between 1 and 5. With 1, being the least relevant. Only those articles that were the most relevant (graded 5) were considered.

This selection process resulted in the 53 most relevant documents from a first search of 713 to be considered in detail as the source for extraction of biomimetic strategies with high potential to be useful to help solve built environment problems.

4.3. Phase 3: Data Analysis (for Case Studies)

In this phase, the researcher extracted strategies and summarized and synthesized the findings from the selected literature to create a database. In a Microsoft Excel spreadsheet, a table was created that included author(s), title, publication year, document focus, number of citations, document type, source title, and a coded description for each biomimetic case study mentioned in the source documents, note that some documents had several case studies. These coded case study descriptions were each assigned a unique identifier code prefixed by CS.

4.4. Phase 4: Data Synthesis (for Strategies)

A database of biomimetic strategies from the previous phase, which was used in the case studies extracted previously, was generated. These strategies, as well as other parameters extracted from the case studies that could be used to classify them, were added to a separate, linked database, which was a second Microsoft Excel spreadsheet. This database has a coded description for each strategy as well as other parameters, including built environment challenge, city system/flow involved, biomimicry level, and applied scale.

It was decided that although the 2017 list of Sustainable Development Goals and their indicators by the United Nations is comprehensive [38], limited indicators are relevant to city-level development. Therefore, city systems/categories included in the Green City Index were used instead to classify the different strategies as they are tailored to the built environment [39]. These categories/city systems are namely Energy and Carbon, Water, Waste, Mobility and Transport, Infrastructure and Buildings, Food, Air Quality, Biodiversity and Green Infrastructure, and Governance and Data.

Each strategy also had the case study code (CS###) from where the strategy was extracted. Each strategy was also given a unique identifier code with a prefix (S###). Some strategies were duplicated in several case studies.

The author continued reviewing and refining this strategy database until no further strategies were found. Through this process, a fully comprehensive list of high-potential strategies was found. This set of strategies was then further classified according to the application scale and the city systems.

5. Results

The data collection and screening phases of the methodology resulted in a list of 53 articles to be considered in the study, as summarized in Table 3 below. These are the source documents that will be used in the following tables to extract biomimetic case studies and strategies. The articles were ordered from the most cited articles to the least cited ones. The leftmost column contains the document ID number that will be used to identify each of the source document records. This identifying ID number will be used in Table 4 to link both tables together.

Table 3.

List of scientific articles relevant to biomimetic applications in the built environment. Full list of the source documents is available upon request from the author. For readability reasons, the table has been formatted with shortened references.

| SourceDoc ID | Author, Year | Title | Source Document Focus | Citation Ref-No |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | (López et al., 2017) | How plants inspire facades. From plants to architecture: Biomimetic principles for the development of adaptive architectural envelopes | Adaptive building envelopes | [40] |

| 2 | (Mathews, 2011) | Towards a Deeper Philosophy of Biomimicry | Philosophical principles | [41] |

| 3 | (Al-Obaidi et al., 2017) | Biomimetic building skins: An adaptive approach | Adaptive building envelopes | [42] |

| 4 | (Yuan et al., 2017) | Bionic building energy efficiency and bionic green architecture: A review | Energy efficiency, structure, and materials | [43] |

| 5 | (Anzaniyan et al., 2022) | Design, fabrication and computational simulation of a bio-kinetic façade inspired by the mechanism of the Lupinus Succulents plant for daylight and energy efficiency | Biomimetic kinetic envelope design | [44] |

| 6 | (Blau et al., 2018) | Urban River Recovery Inspired by Nature-Based Solutions and Biophilic Design in Albufeira, Portugal | Nature-based solutions | [45] |

| 7 | (Hayes et al., 2019) | Leveraging socio-ecological resilience theory to build climate resilience in transport infrastructure | Transport infrastructure | [46] |

| 8 | (Ahamed et al., 2022) | From biology to biomimicry: Using nature to build better structures-A review | Envelopes, structure, and materials | [47] |

| 9 | (Buck, 2017) | The art of imitating life: The potential contribution of biomimicry in shaping the future of our cities | City systems | [48] |

| 10 | (Radwan & Osama, 2016) | Biomimicry, An Approach For Energy Efficient Building Skin Design | Buildings envelopes | [49] |

| 11 | (Hayes et al., 2020) | Learning from nature—Biomimicry innovation to support infrastructure sustainability and resilience | Structure and infrastructure | [50] |

| 12 | (Zari & Hecht, 2020) | Biomimicry for Regenerative Built Environments: Mapping Design Strategies for Producing Ecosystem Services | Ecosystem services | [51] |

| 13 | (Gruber & Imhof, 2017) | Patterns of Growth-Biomimetics and Architectural Design | Growth patterns | [52] |

| 14 | (Badarnah, 2015) | A Biophysical Framework of Heat Regulation Strategies for the Design of Biomimetic Building Envelopes | Envelopes (heat regulation) | [53] |

| 15 | (Chou et al., 2016) | Big data analytics and cloud computing for sustainable building energy efficiency | Energy efficiency management | [54] |

| 16 | (Pedersen Zari & Koner, n.d.) | An ecosystem based biomimetic theory for a regenerative built environment | Ecosystem principles | [55] |

| 17 | (Uchiyama et al., 2020) | Application of biomimetics to architectural and urban design: A review across scales | Biomimicry across scales | [33] |

| 18 | (Carlos Montana-Hoyos & Carlos Fiorentino, 2016) | Bio-utilization, bio-inspiration, and bio-affiliation in design for sustainability: Biotechnology, biomimicry, and biophilic design | Education | [56] |

| 19 | (Blanco et al., 2021) | Urban Ecosystem-Level Biomimicry and Regenerative Design: Linking Ecosystem Functioning and Urban Built Environments | Ecosystem biomimicry | [57] |

| 20 | (Ilieva et al., 2022) | Biomimicry as a Sustainable Design Methodology-Introducing the ‘Biomimicry for Sustainability’ Framework | Classification framework | [58] |

| 21 | (Badarnah, 2016) | Light management lessons from nature for building applications | Light management | [59] |

| 22 | (Dash, 2018) | Application of biomimicry in building design | Case studies classification | [60] |

| 23 | (Jamei & Vrcelj, 2021) | Biomimicry and the Built Environment, Learning from Nature’s Solutions | Envelopes, structure, materials, and energy retrofits | [61] |

| 24 | (Timea Kadar & Manuella Kadar, 2020) | Sustainability Is Not Enough: Towards AI Supported Regenerative Design | AI for regenerative design | [62] |

| 25 | (Spiegelhalter & Arch, 2010) | Biomimicry and circular metabolism for the cities of the future | Ecosystem biomimicry | [63] |

| 26 | (Lazarus & Crawford, n.d.) | Returning genius to the place | Ecosystem biomimicry | [64] |

| 27 | (Sommese et al., 2022) | A critical review of biomimetic building envelopes: towards a bio-adaptive model from nature to architecture | Adaptive building envelopes | [65] |

| 28 | (Pedersen Zari, 2009) | An architectural love of the living: Bio-inspired design in the pursuit of ecological regeneration and psychological well-being | Ecosystem biomimicry | [66] |

| 29 | (Dicks et al., 2021) | Applying Biomimicry to Cities: The Forest as Model for Urban Planning and Design | Forest ecosystem biomimicry | [67] |

| 30 | (Faragalla & Asadi, 2022) | Biomimetic Design for Adaptive Building Facades: A Paradigm Shift towards Environmentally Conscious Architecture | Adaptive building envelopes | [68] |

| 31 | (Imani & Vale, 2022) | Developing a Method to Connect Thermal Physiology in Animals and Plants to the Design of Energy Efficient Buildings | Thermal energy efficiency | [69] |

| 32 | (Faragllah, 2021) | Biomimetic approaches for adaptive building envelopes: Applications and design considerations | Adaptive building envelopes | [70] |

| 33 | (Verbrugghe et al., 2023) | Biomimicry in Architecture: A Review of Definitions, Case Studies, and Design Methods | Biomimetic design methods | [37] |

| 34 | (Benyus et al., 2022) | Ecological performance standards for regenerative urban design | Ecological performance standards (EPS) | [71] |

| 35 | (Elshapasy et al., 2022) | Bio-Tech Retrofitting To Create A Smart-Green University | Biomimicry and smart buildings | [72] |

| 36 | (Hao et al., n.d.-b) | Closed-Loop Water and Energy Systems: Implementing Nature’s Design in Cities of the Future | Closed-loop urban water systems | [73] |

| 37 | (Movva & Velpula, 2020) | An analytical approach to sustainable building adaption using biomimicry | Building scale biomimetic design | [74] |

| 38 | (Hao et al., 2010a) | Network Infrastructure—Cities of the Future | Urban water management | [73] |

| 39 | (Oguntona & Aigbavboa, 2019) | Assessing the awareness level of biomimetic materials and technologies in the construction industry | Biomimetic construction materials and technologies | [75] |

| 40 | (Quintero et al., 2021) | Sustainability Assessment of the Anthropogenic System in Panama City: Application of Biomimetic Strategies towards Regenerative Cities | Biomimetic regenerative cities and EPS | [76] |

| 41 | (Speck et al., 2022) | Biological Concepts as a Source of Inspiration for Efficiency, Consistency, and Sufficiency | Biological concepts of lianas | [77] |

| 42 | (Widera, 2016) | Biomimetic And Bioclimatic Approach To Contemporary Architectural Design On The Example Of CSET Building | Biomimicry for net zero buildings | [78] |

| 43 | (AlAli et al., 2023) | Applications of Biomimicry in Architecture, Construction and Civil Engineering | Biomimicry in building design | [79] |

| 44 | (Aslan et al., 2022) | A Biomimetic Approach to Water Harvesting Strategies: An Architectural Point of View | Water harvesting on the building level | [80] |

| 45 | (Ortega Del Rosario et al., 2023) | Environmentally Responsive Materials for Building Envelopes: A Review on Manufacturing and Biomimicry-Based Approaches | Responsive building envelopes | [81] |

| 46 | (Elsakksa et al., 2022) | Biomimetic Approach for Thermal Performance Optimization in Sustainable Architecture. Case study: Office Buildings in Hot Climate Countries | Envelope Thermal Performance | [82] |

| 47 | (Mazzoleni et al., 2008b) | Eco-systematic restoration: a model community at Salton Sea | Biomimetic urban Restoration | [83] |

| 48 | (Sharma & Singh, 2021) | Protecting humanity by providing sustainable solution for mimicking the nature in construction field | Biomimicry levels in built environment | [84] |

| 49 | (Van Den Dobbelsteen et al., 2010) | Cities As Organisms: Using Biomimetic Principles To Become Energetically Self-Supporting And Climate Proof | Biomimetic city planning principles | [85] |

| 50 | (Pedersen Zari M, 2018) | Can built environment biomimicry address climate change? | Biomimetic strategies | [7] |

| 51 | (Pedersen Zari M, 2018) | Emulating ecosystem services in architectural and urban design Ecosystem services analysis | Ecosystem services |

[7] |

| 52 | (Pedersen Zari M, 2018) | Incorporating biomimicry into regenerative design | Biomimetic strategy regenerative design | [7] |

| 53 | (Pedersen Zari M, 2018) | Translating ecosystem processes into built environment design | Ecosystem services | [7] |

Each of these 53 articles was read and analyzed to extract the biomimetic case studies relevant to the built environment. Along with each case study, other parameters were also collected, including location, natural inspiration model, biomimicry level, and the corresponding source documents. These are summarized in Table 4 below. The leftmost column contains the case study ID (CS###) that will be used to identify each of the case studies. This identifying code will be used in Table 5 to link both tables (4 and 5) together. Moreover, to link each case study to the source documents in which they were mentioned, the source document ID(s) are provided in the rightmost column. This column acts as the link between both tables (3 and 4) to illustrate how they are related.

Table 5.

List of biomimetic strategies extracted from the precedent biomimetic case studies. Abbreviations Legend Application Scale: Urban Scale (U), Whole Building (B), Building Component (C). City Systems: Energy and Carbon (EC), Water (WR), Waste (WS), Mobility and Transport (MT), Infrastructure and Buildings (IB), Food (FD), Air Quality (AQ), Biodiversity and Green Infrastructure (BG), Governance and Data (GD).

| Strategy ID | Biomimetic Strategy | Corresponding Case Study ID |

Application Scale | City Systems |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| S001 | Sequester atmospheric carbon into building materials, Neutral and strength-enhancing carbon sequestering cement | CS003, CS016, CS111, CS112 | C | EC, IB |

| S002 | Low Carbon Economy (LCE) | CS105 | U | EC |

| S003 | (Efficient) wind turbines | CS097, CS098, CS064, CS104, CS110, CS127, CS128, CS135 | U, C | EC |

| S004 | Hydro turbines | CS036, CS037 | U | EC |

| S005 | Geothermal energy | CS104 | U | EC |

| S006 | CHP—Combined Heating and Power Plants | CS104 | U | EC |

| S007 | Solar Photovoltaic Panels (on building’s roof and façade) | CS023, CS036, CS064, CS076, CS080, CS104, CS110, CS126, CS127, CS135 | B | EC, IB |

| S008 | Dye-Sensitive Solar cells | CS018 | C | EC |

| S009 | Solar Benches | CS064 | U | EC |

| S010 | Solar light posts | CS064 | U | EC |

| S011 | Biofuel producing algae farms | CS135 | U | EC, BG |

| S012 | Biomass | CS104 | U | EC |

| S013 | Blue battery, energy storage for different RE outputs | CS099 | U | EC |

| S014 | Batteries to store renewable energy | CS078, CS135 | B | EC |

| S015 | Bioluminescence Materials | CS065 | U | EC |

| S016 | P2P energy sharing via blockchain technology | CS101 | B, C | EC, GD |

| S017 | Reduce Peak Demand | CS045 | C | EC, GD |

| S018 | Zero (fossil) energy | CS023, CS104, CS135 | B | EC |

| S019 | low energy passive house | CS104 | U | EC, IB |

| S020 | Passive design strategies | CS135, CS104 | U | EC, IB |

| S021 | Active Solar design strategies | CS104 | U | EC, IB |

| S022 | Wall/slab thermal mass | CS135 | U | EC, IB |

| S023 | Energy excess fed into grid | CS135 | U | EC |

| S024 | Double glazing | CS135 | U | EC, IB |

| S025 | Openings sizing to control solar radiation | CS135 | U | EC, IB |

| S026 | District Heating/Cooling | CS104 | U | EC |

| S027 | Spot heating system | CS022 | C | EC |

| S028 | Underground radiant heating/cooling | CS002, CS051, CS116, CS135 | C | EC |

| S029 | Geothermal heat pump | CS110, CS127, CS135 | B, U | EC |

| S030 | Cooling by avoiding direct sunlight | CS092 | B | EC |

| S031 | Radiative heat gain | CS092 | B | EC |

| S032 | Heat by Occupants’ Metabolism | CS091, CS100 | B | EC |

| S033 | Improved Trombe wall | CS054 | C | EC |

| S034 | Solar water heating/Solar Collector | CS025, CS127, CS135 | B | EC |

| S035 | Sewage heat recovery | CS115 | U | EC |

| S036 | Heat sinks | CS135 | U | EC |

| S037 | Solar ponds | CS135 | U | EC |

| S038 | Water cooled façade | CS135 | U | EC, IB |

| S039 | Passive Cooling (Stack effect Ventilation) | CS001, CS002, CS138 | B | EC |

| S040 | Natural Cross Ventilation | CS050, CS135 | B | EC, AQ |

| S041 | Demand-driven ventilation system | CS085 | B | EC, AQ |

| S042 | Wind Catchers | CS023, CS110 | B | EC, IB |

| S043 | Minimal Structural members for maximum daylight | CS034 | B | IB, EC |

| S044 | Fiber optic lighting system | CS048 | C | EC, IB |

| S045 | Phyllotaxy/Fibonacci order to avoid self-shading | CS049, CS095 | B | IB, EC |

| S046 | Narrow Floor Plan Depth | CS031, CS135 | B | IB, EC |

| S047 | Reflect/Focus light into Dim Areas | CS031 | B, C | EC, BI |

| S048 | Inflatable membrane structures | CS010, CS053, CS060 | B | IB, EC |

| S049 | Responsive Adaptive skin color change to retain or absorb heat | CS113 | B | EC, IB, GD |

| S050 | Solar Envelope Masterplanning | CS104 | U | EC, IB |

| S051 | Elastically Deformable Louvers | CS004, CS005 | C | EC, IB |

| S052 | Solar Self-Shading | CS008, CS013, CS039, CS074, CS080, CS093, CS124 | B | EC, IB |

| S053 | Responsive Adaptive Shading System | CS009, CS031, CS134 | C | EC, GD |

| S054 | Kinetic screen | CS132 | B | EC, GD |

| S055 | Foldable Shading Devices | CS031 | B, C | EC |

| S056 | Adjustable Shading Device | CS133, CS033, CS139 | B | EC |

| S057 | inflatable shading device | CS131 | C | EC |

| S058 | Dynamic Windows | CS094 | C | EC |

| S059 | Electrochromic smart windows for energy savings | CS040 | C | EC, GD |

| S060 | Dyed glass to decrease light projection | CS117 | C | EC |

| S061 | Self-thermoregulation hybrid systems | CS127 | B | EC, GD |

| S062 | Responsive Adaptive envelopes | CS090, CS109 | B, C | IB, EC |

| S063 | humidity-sensitive envelope | CS006 | C | IB |

| S064 | Envelope controls daylight and air quality | CS075 | B | EC, IB |

| S065 | Walkable city/compact city design | CS003, CS104 | U | MT, EC, AQ |

| S066 | Building on columns for less footprint | CS023 | B | IB |

| S067 | Allow for Growth (degrowth) | CS052 | B | IB |

| S068 | Design for disassembly | CS062, CS082, CS103 | B | IB |

| S069 | Standardized modular prefabricated parts | CS030, CS036, CS062, CS082 | C | IB |

| S070 | Refurbish rather than dismantle | CS102 | B | IB |

| S071 | Design for Longevity | CS102, CS103 | B | IB |

| S072 | Design for adaptability | CS103 | U | IB |

| S073 | Adaptive Building Zoning | CS025 | B, C | IB, EC |

| S074 | Reduce surface area to volume ratio | CS076 | B | IB, EC |

| S075 | Parasitic Architecture (addition of net zero units on top of existing buildings, surplus PV power provided to the building in exchange for use of staircase, etc.) | CS126 | B | IB |

| S076 | Building orientation | CS135 | U | IB, EC |

| S077 | Decentralization | CS104 | U | GD |

| S078 | Decentralized services and markets | CS104 | U | IB |

| S079 | Hexagonal structural elements | CS074, CS053, CS060, CS010 | B | IB |

| S080 | Remove excess structural material | CS011, CS031, CS074, CS083 | B | IB |

| S081 | Hollow Structural elements with integrated systems | CS031 | B, C | IB |

| S082 | Cobiax technology | CS085 | B | IB, WS |

| S083 | Thin-shell structure | CS020, CS061, CS087, CS089 | B | IB |

| S084 | Lightweight Structure | CS034, CS072 | B | IB |

| S085 | Shell lace structure | CS083 | B | IB |

| S086 | Branching columns | CS032 | B | IB |

| S087 | Irregular steel trusses structure | CS012 | B | IB |

| S088 | Curved diagrid steel envelope structure | CS044 | B | IB |

| S089 | Radial bifurcating ribs | CS058, CS063, CS106 | B | IB |

| S090 | Multidimensional curvature structure | CS096 | B | IB |

| S091 | Skin as Structure | CS074 | B | IB |

| S092 | Barrel structure | CS056 | B | IB |

| S093 | Responsive adjusting to loads. Infrastructure senses structural compromises and alters structure to compensate | CS028 | U | IB, GD |

| S094 | Flexible structures for high wind loads | CS046, CS011 | B | IB |

| S095 | Folding Structure | CS033, CS139 | C | IB |

| S096 | Suspension structure | CS057 | B | IB |

| S097 | Suspended-cable structure | CS059 | B | IB |

| S098 | load bearing curvilinear walls | CS084 | B | IB |

| S099 | Locally available materials | CS086, CS088 | B | IB |

| S100 | Recycled construction materials | CS078 | B | IB, WS |

| S101 | Design for less maintenance | CS007, CS015, CS029, CS030, CS055, CS108, CS118, CS119, CS122 | C | IB |

| S102 | Photocatalytic cement, neutralize organic and inorganic pollutants. It makes surfaces self-cleaning. Savings in maintenance costs | CS122 | B, U | IB |

| S103 | Smart Vapor Retarder blocks | CS136 | C | IB |

| S104 | surfaces that inhibit bacterial growth on high-touch surfaces | CS118 | C | IB |

| S105 | Non emissive materials | CS135 | U | IB, AQ |

| S106 | Self-cleaning paints | CS007 | C | IB |

| S107 | Self-cleaning solar panels | CS108 | C | IB, EC |

| S108 | Self-cleaning clay roofs | CS119 | C | IB |

| S109 | Self-cleaning urban elements | CS055 | C | IB |

| S110 | Self-healing cement/concrete | CS015, CS029 | C | IB |

| S111 | Industrial Ecology | CS069, CS105 | U | WS, EC |

| S112 | Closed-loop models/Cradle-to-cradle | CS026, CS035, CS047, CS069 | B, U | GD, WS |

| S113 | Organic Waste to Biogas and fertilizers | CS026, CS070, CS075 | U | WS, EC, FD |

| S114 | Biogas to energy (from landfills and waste treatment plants) | CS104 | U | WS, EC |

| S115 | Thermal waste treatment plant for (non-recyclables) | CS104 | U | WS |

| S116 | Fermentation of Bioorganic waste to energy | CS104 | U | WS, EC |

| S117 | Zero waste to landfill | CS047, CS135 | U | WS |

| S118 | Design out waste | CS103, CS104 | U | WS |

| S119 | Onsite waste recycling | CS036 | U | WS |

| S120 | Upcycle/recycle waste | CS078, CS103, CS104 | B | WS, GD |

| S121 | Zero Waste | CS135 | U | WS, GD |

| S122 | (Net) zero emissions | CS036, CS047, CS064, CS077, CS104, CS135 | U | AQ, EC |

| S123 | Non-toxic VOC-free wood glue | CS043 | C | AQ, IB |

| S124 | Biofilters for air purification | CS079, CS121 | U | AQ |

| S125 | Nature-based solution (NBS) and Biophilia | CS064, CS068 | U | BG |

| S126 | Green walls/vertical garden | CS064, CS085 | B | BG, IB, EC, AQ |

| S127 | Gravity driven irrigation | CS085 | B | BG, WR |

| S128 | Smart irrigation (soil sensors) | CS115 | U | WR, GD |

| S129 | Green Roofs | CS064, CS114, CS115 | U | BG, IB, EC, AQ |

| S130 | Organic suspended roof gardens | CS036, CS115 | U | FD, BG, EC |

| S131 | (Pervious) green corridor/green belt | CS003, CS027, CS64, CS104 | U | BG, AQ |

| S132 | Green Infrastructure | CS064 | U | BG |

| S133 | Trees and Shrubs | CS064 | U | BG, AQ |

| S134 | Permeable (Pervious) Paving/Urban Surfaces | CS064, CS003 | U | IB, WR |

| S135 | Recycle/Purify all Urban Water | CS064 | U | WR |

| S136 | Bioswales | CS114 | U | WR |

| S137 | Protect native landscapes/forests | CS104 | U | BG |

| S138 | interconnect protected landscape areas with biotopes | CS104 | U | BG |

| S139 | Urban landscapes | CS104 | U | BG, IB, AQ |

| S140 | Nature sensitive farming | CS135 | U | FD, BG |

| S141 | UV-reflective coating that mitigates bird collisions | CS120 | C | IB, BG |

| S142 | Design for increased biodiversity | CS035, CS073 | U | BG |

| S143 | Ecosystem Services | CS014, CS067 | U | GD |

| S144 | Ecological Performance Standards (EPS) | CS003, CS014, CS067, CS111, CS112 | U | GD |

| S145 | Food forest | CS135 | U | FD |

| S146 | Fish pond | CS135 | U | FD |

| S147 | Edible plants | CS135 | U | FD |

| S148 | Water Neutrality | CS135 | U | WR |

| S149 | Fog water collection | CS020, CS021, CS024, CS035, CS042, CS107, CS129 | B | WR |

| S150 | Rainwater Collection | CS042, CS077, CS114, CS115, CS129, CS 135, | C | WR |

| S151 | Rainwater filtration | CS114 | U | WR |

| S152 | Rainwater Storage | CS008, CS114, CS115 | B | WR |

| S153 | Water banking (inter-seasonal water storage) | CS115, CS003 | U | WR |

| S154 | Cistern Rainwater Storage | CS114, CS115 | B | WR |

| S155 | Rainwater storage pockets on façade | CS130 | C | WR |

| S156 | Rainwater onsite use | CS114, CS135 | U | WR |

| S157 | Greywater onsite use for irrigation and toilet flush | CS076, CS077, CS114, CS135 | B | WR |

| S158 | Recharge Aquifers | CS027 | U | WR |

| S159 | Connect water infrastructure to the surrounding watershed | CS115 | U | WR |

| S160 | water conservation | CS104 | U | WR |

| S161 | Adapt rain screens on buildings to enhance evapotranspiration and reduce runoff | CS017 | U | WR, IB |

| S162 | multipath low-grade channel designs of underground stormwater infrastructures and street layouts take a similar form | CS003 | U | WR |

| S163 | Redirect water to increased flow paths | CS003 | U | WR |

| S164 | Eliminate chemical runoff to waterbodies | CS135 | U | WR |

| S165 | Membrane filtration technology for safe drinking water | CS041 | C | WR |

| S166 | Onsite wastewater treatment (Bioreactor membrane) | CS114 | U | WR |

| S167 | Chemical-free wastewater treatment and filtering system | CS019, CS026, CS027, CS038, CS073 | U | WR |

| S168 | Wetland | CS135 | U | WR, BG |

| S169 | Electric Transport | CS123 | U | MT, EC, AQ |

| S170 | Routing Algorithm | CS125 | U | MT, EC |

| S171 | Reduced-traffic zones | CS104 | U | MT, AQ |

| S172 | Direct Access to public transport | CS104 | U | MT |

| S173 | Pedestrian traffic | CS104 | U | MT |

| S174 | Connecting public transport to bike lane network | CS104 | U | MT |

| S175 | Reduce distance to nearest bus/tram stop | CS104 | U | MT |

| S176 | High-density public transport | CS104 | U | MT |

| S177 | bicycle networks | CS104 | U | MT |

| S178 | Design infrastructure to mimic capacity hierarchies, bifurcation angles, and minimal disruption of flow | CS066 | U | MT |

| S179 | Bullet train | CS071 | U | MT, EC |

| S180 | Sensors and Actuators | CS028 | U | GD |

| S181 | Real-time building energy use auditing | CS104 | U | GD, EC |

| S182 | Real-time building CO2 emissions auditing | CS104 | U | GD, EC |

| S183 | Integrated systems | CS135 | U | GD |

| S184 | self-sustaining off-grid system (energy, water) | CS036, CS081, CS127, CS137 | U | GD |

Table 4.

List of biomimetic case studies extracted from the source documents in the previous table. Abbreviations Legend Biomimicry Level: Organism Level (OL), Behavior Level (BL), Ecosystem Level (EL).

| Case Study ID | Case Studies | Location | Natural Model | Biomimicry Level | Source Document ID(s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CS001 | Eastgate Building | Zimbabwe | Termite mound | BL | 4, 8, 10, 17, 22, 23, 27, 32, 33, 37, 43, 46, 48, 50, 52 |

| CS002 | City Council House 2 (CH2) | Australia | Termite mound, trees bark | BL | 4, 10, 22, 23, 32, 33, 37, 43, 46, 50 |

| CS003 | Lavasa | India | Indian Harvester Ant, Fig leaf, Natural water cycle, Ecosystem Performance Standards | BL, EL | 9, 10, 19, 22, 26, 34, 40, 51, 52 |

| CS004 | Flectofins by ITKE | Stuttgart, Germany | Valvular pollination mechanism in the Strelitzia reginae flower (aka Bird-Of-Paradise flower) | OL | 1, 3, 5, 17, 20, 27, 40 |

| CS005 | One Ocean Thematic Pavilion by SOMA Architecture | Yeosu, South Korea | Valvular pollination mechanism in the Strelitzia reginae flower (aka Bird-Of-Paradise flower) | OL | 1, 3, 23, 27, 33 |

| CS006 | HygroSkin Pavilion | Orleans, France | spruce (pine?) cones passive response to humidity changes | OL | 1, 3, 5, 17, 27 |

| CS007 | Lotusan Paint | Not Applicable | Lotus Leaves | OL | 4, 8, 29, 39, 52 |

| CS008 | MMAA | Qatar | Cactus | OL, BL | 22, 32, 43, 46, 48 |

| CS009 | Intitute de monde Arabe | France | Eye Iris | BL | 4, 22, 27, 33 |

| CS010 | Water Cube National Swimming Center Beijing | China | Bubbles | OL | 4, 10, 22, 27 |

| CS011 | Eiffel Tower | France | Thigh Bone | OL | 10, 22, 23, 43 |

| CS012 | Pechino National Stadium (Birds Nest Stadium) | Beijing, China | Bird’s nest | OL | 4, 10, 22, 27 |

| CS013 | Espalande theater | Singapore | Durian Fruit, sea urchin shells | OL | 10, 22, 27, 33 |

| CS014 | Lloyd Crossing | USA | Local ecosystem patterns | EL | 19, 40, 51, 52 |

| CS015 | Self-repairing concrete (Bio-concrete/Bionic self-healing concrete) | Not Applicable | Trees/fauna and human skin | BL | 4, 37, 39 |

| CS016 | Calera Portland cement, Eco-Cement | Not Applicable | Salp fish, seashells, and the Saguaro cactus | BL | 9, 37, 39 |

| CS017 | Urban Green Print Project | Seattle, USA | Water cycle, Forest | EL | 9, 51, 52 |

| CS018 | Cooke’s koki’o photosensitive | Not Applicable | Photosynthesis, Cooke’s Koki`o (Kokia cookei) | BL | 9, 37, 39 |

| CS019 | Living Machine/Eco-machine | Not Applicable | Natural water purification, Wetlands | EL | 18, 37, 39 |

| CS020 | Lotus Temple | New Delhi, India | Lotus Flower | OL | 22, 27, 33 |

| CS021 | Hydrological Center Namib University | Namibia | Stenocara Beetle | OL | 35, 44, 52 |

| CS022 | IRLens Spot Heating System | Not Applicable | crayfish and lobster eyes | BL | 37, 39, 50 |

| CS023 | Rafflesia Zero Energy House | Not Applicable | Rafflesia flower | BL | 22, 33, 43 |

| CS024 | The Las Palmas Water Theater | Spain | Stenocara Namib Beetle | OL | 4, 44 |

| CS025 | Heliotrope | Germany | Sunflower | OL | 4, 17 |

| CS026 | Mobius | London, UK | ecosystem’s recycling of resources, Wetlands | EL | 9, 20 |

| CS027 | Eco-Smart City of Langfang | Langfang, China | Natural water cycle, wetlands | EL | 9, 26 |

| CS028 | Tensegrity (Kurilpa) Bridges | Australia | Spider web, human body’s adaptation to damage | OL, BL | 9, 22 |

| CS029 | Biocement, Engineered cement composite | Not Applicable | flexible self-healing skin | BL | 17, 48 |

| CS030 | i2 Modular Carpets | Not Applicable | Forest floor, organized chaos of nature’s ground coverings | OL | 18,39 |

| CS031 | Explore Biomimetic office Building | Zurich, Switzerland | Spookefish eye, brittle starfish, Stone Plant, Bird’s skull, mimosa leaves, Beetle’s wings, mollusc’s iridescent shell, double-duty spinal column, mimosa pudica plant | OL, BL | 23, 46 |

| CS032 | Sagrada Familia | Barcelona, Spain | Tree | OL | 22, 27 |

| CS033 | Milwaukee Art Museum | Milwaukee, USA | Bird Wings, Animal bone | OL | 4, 27 |

| CS034 | Eden Project | Cornwall, UK | Soap Bubbles Formation | BL | 27, 33 |

| CS035 | Sahara Forest Project | Qatar, Tunisia, and Jordan | Namibian Desert Beetle, Ecosystem | BL, EL | 24, 33 |

| CS036 | The carbon-neutral Utopian Village (coral reef project) | Haiti | Coral Reefs | EL | 35, 43 |

| CS037 | BioWave | Not Applicable | Bull Kelp, Cochayuyo seaweed withstand strong wave forces by being flexible and stretchy | OL | 37, 39 |

| CS038 | Biolytix System | Not Applicable | Earth Ecosystem | EL | 37, 39 |

| CS039 | COMOLEVI Forest Canopy | Not Applicable | Shadow Trees | OL | 37,39 |

| CS040 | Sage GlassQuantum Glass | Not Applicable | Bobtail squid, hummingbird | OL | 37, 39 |

| CS041 | Aquaporin Membrane | Not Applicable | lipid bilayer of living cells, cell membrane | BL | 37,39 |

| CS042 | Chaac-ha | Not Applicable | Spiders and Bromeliads | OL | 37, 39 |

| CS043 | Purebond (Bioplywood) | Not Applicable | Blue mussel mollusk adhesion | OL | 37, 39 |

| CS044 | Gherkin Tower, SwissRe Headquarters | London, UK | Venus flower basket sponge | OL | 22, 43 |

| CS045 | Encycle BMS Swarm Logic | Not Applicable | Honeybees | BL | 23, 50 |

| CS046 | Waterloo International Terminal | Waterloo, UK | pangolin | OL | 22, 53 |

| CS047 | brewery near Tsumeb | Namibia | Ecosystem | EL | 2 |

| CS048 | Sunflower fiber optic lighting system | Japan | Sunflower | OL | 4 |

| CS049 | Urban Cactus | Netherlands | phyllotaxy, which refers to the way in which the leaves of different plants grow on the stem and which varies between alternate phyllotaxy | OL | 4 |

| CS050 | Haikou Tower | China | fins | OL | 4 |

| CS051 | Duisburg Business Support Cente | Germany | biological circulatory system | OL | 4 |

| CS052 | The Sky house by kiyonori Kikutake | Japan | Growth and Metabolism | BL | 4 |

| CS053 | Tokyo Dome Stadium | Japan | Bubbles | OL | 4 |

| CS054 | School of Youth Education designed by Thomas Herzog | Germany | Polar Bear Skin | OL | 4 |

| CS055 | Self-cleaning traffic light glass | Germany | Lotus Leaves | OL | 4 |

| CS056 | Willis Tower | Chicago, USA | Bamboo | OL | 4 |

| CS057 | BMW Office Building | Munich, Germany | Ears of wheat | OL | 4 |

| CS058 | Rome Gatt Wool Factory | Italy | Lotus leaf vein | OL | 4 |

| CS059 | Worker’s Stadium | Beijing, China | Cobweb | OL | 4 |

| CS060 | Fuji Pavilion World Expo, 1970 | Osaka, Japan | Soap bubble | OL | 4 |

| CS061 | National Industries & Techniques Center | France | Eggshell | OL | 4 |

| CS062 | The Montreal Biosphere | Montreal, Canada | Honeycomb | OL | 4 |

| CS063 | Palazzeto Dellospori | Rome, Italy | Amazon Water Lilly | OL | 4 |

| CS064 | Albufeira River Restoration | Portugal | Nature Based Solutions, Soil, Evapotranspiration | EL | 6 |

| CS065 | Van Gogh Roosegaarde cycle route | Eindhoven, Netherlands | Bioluminescence | BL | 6 |

| CS066 | Tokyo railway mapping experiment | Tokyo, Japan | Physarum polycephalum Slime Mould | BL | 9 |

| CS067 | Wellington | New Zealand | Ecosystem services (provision of water and energy) | EL | 17 |

| CS068 | Green surge project | Europe | Nature | EL | 17 |

| CS069 | Kalundborg Industrial Complex | Kalundborg, Denmark | ecosystem’s recycling of resources | EL | 18 |

| CS070 | Organic Waste Biodigester | Not Applicable | Natural Decomposition Process | BL, EL | 18 |

| CS071 | Bullet train | Japan | Kingfisher Bird’s beak | OL | 20 |

| CS072 | Silk Pavilion | Massachusetts, USA | Silkworm | OL | 20 |

| CS073 | Biohaven’s Floating Islands | Not Applicable | Wetland ecosystems | EL | 20 |

| CS074 | Sinosteel International Plaza | Tianjin, China | Beehive | OL | 22 |

| CS075 | Habitat 2020 | Not Applicable | stomata of leaves | BL | 22 |

| CS076 | Tree scraper, tower of tomorrow | Not Applicable | Tree growth | BL | 22 |

| CS077 | Taichung Opera house | Taichung, Taiwan | Schwarz P type | OL | 22 |

| CS078 | Earth ships | Not Applicable | Ship? | EL | 22 |

| CS079 | Treepods | Boston, USA | Dragon tree | BL | 22 |

| CS080 | All seasons tent tower | Armenia | Mt. Ararat | OL | 22 |

| CS081 | Lily pad floating city | Not Applicable | Lily pad | EL | 22 |

| CS082 | Loblolly House | Maryland, USA | tree house | BL | 22 |

| CS083 | Shi ling bridge | China | shell lace structure | OL | 22 |

| CS084 | Guggenheim Museum | New York, USA | Ship | OL | 22 |

| CS085 | Parkroyal | Singapore | Vertical Garden | BL | 22 |

| CS086 | SUTD library pavilion | Singapore | timber shell | BL | 22 |

| CS087 | Sydney opera house | Sydney, Australia | shell structure | OL | 22 |

| CS088 | Redwood Tree house | New Zealand | seed pod | OL | 22 |

| CS089 | TWA terminal | New York, USA | bird flight | OL | 22 |

| CS090 | Institute for Computer-Based Design | Stuttgart, Germany | BL | 23 | |

| CS091 | Himalayan rhubarb towers | China | Metabolism heat | BL | 23 |

| CS092 | Cabo Llanos Towers | Santa Cruz de Tenerife, Spain | BL | 23 | |

| CS093 | Simon Center for Geometry and Physics at the State University | New York, USA | Tree Canopy | OL | 23 |

| CS094 | Hobermann’s Dynamic Windows | Not Applicable | Tree Canopy | OL | 23 |

| CS095 | phyllotactic towers | Iran | Plants with phyllo-tactic geometry | OL | 23 |

| CS096 | Pantheon | Rome, Italy | Seashell | OL | 23 |

| CS097 | Vertical Wind turbines | Not Applicable | Schools of fish | BL | 23 |

| CS098 | humpback fin wind turbine | Not Applicable | humpback whale fin | OL | 23 |

| CS099 | Green Power Island | Not Applicable | Energy storage | BL | 23 |

| CS100 | Max Fordham’s House | London, UK | Metabolism heat | BL | 24 |

| CS101 | IKEA’s Space 10 lab miniature wooden village | Copenhagen, Denmark | Mycellium | BL | 24 |

| CS102 | Here East | Lonon, UK | Nature recycles everything | EL | 24 |

| CS103 | Waterloo City Farm | Waterloo, UK | Nature recycles everything | EL | 24 |

| CS104 | Rieselfeld & Vauban | Freiburg, Germany | Ecosystem | EL | 25 |

| CS105 | Hammarby Sjostad District | Sweden | ecosystem’s recycling of resources | EL | 25 |

| CS106 | Crystal Palace | London, UK | Victoria amazonica | OL | 27 |

| CS107 | Teatro del Agua | Canary Islands | Stenocara Beetle, Hydrological cycle | BL | 28 |

| CS108 | Self-cleaning Solar Panels | Not Applicable | Lotus Leaves | OL | 29 |

| CS109 | Homeostatic Façade | New York, USA | Muscles | BL | 33 |

| CS110 | Cairo Gate Residence | Cairo, Egypt | Termite Mound | BL | 33 |

| CS111 | Durban resilient development plan | South Africa | Kwazulu Natal-Cape coastal forests, Southern Africa mangroves | EL | 34 |

| CS112 | Interface Inc.: factory as a forest | Lagrange, USA | Oak–hickory–pine forest | EL | 34 |

| CS113 | Adaptive fitting glass | Not Applicable | Namaqua chameleon | BL | 35 |

| CS114 | Dockside Green development | B.C, Canada | Hydrological cycle | EL | 36 |

| CS115 | Vancouver Olympic Village at Southeast False Creek | Vancouver, Canada | Hydrological cycle | EL | 36 |

| CS116 | Radiant Cooling Technology | Not Applicable | Ground water channels | EL | 37 |

| CS117 | Turtle glass | Not Applicable | Chelonia mydas | OL | 37 |

| CS118 | sharklet | Not Applicable | Shark skin | OL | 39 |

| CS119 | Lotus clay roofing tiles | Not Applicable | Lotus Leaves | OL | 39 |

| CS120 | Ornilux insulated glass, | Not Applicable | Orb weaver spiders | OL, BL | 39 |

| CS121 | BioUrban 2.0 | Panama City, Panama | Trees | BL | 40 |

| CS122 | Photocatalytic cement | Milan, Italy | nature uses nonharmful chemicals | EL | 40 |

| CS123 | IONITY | Europe | Nature uses clean energy | EL | 40 |

| CS124 | Sierpinski roof | Not Applicable | Sierpinski forest | OL | 40 |

| CS125 | La Paz and El Alto | Bolivia | ant colony algorithm | BL | 40 |

| CS126 | Plus-energy Rooftop Unit | Not Applicable | Liana | BL | 41 |

| CS127 | CSET building | Ningbo, China | natural flows | EL | 42 |

| CS128 | Pearl River Tower | China | Sea sponge | OL | 43 |

| CS129 | Warka Towers | Ethiopia | Spider Web | OL | 44 |

| CS130 | Rainbellows | Seattle, USA | Ice Flower | OL | 44 |

| CS131 | The Media TIC building | Barcelona, Spain | Stomata | BL | 46 |

| CS132 | Doha Tower | Doha, Qatar | Cactus Pores | BL | 46 |

| CS133 | Tricon Corporate Center | Lahore, Pakistan | Oxalis Oreganada leaf | BL | 46 |

| CS134 | Al Bahar Tower | Abu Dhabi, UAE | White Butterfly | BL | 46 |

| CS135 | Model Community at Salton Sea | California, USA | Ecosystem, Algae | EL | 47 |

| CS136 | MemBrain blocks | Not Applicable | stomata transpiration | BL | 48 |

| CS137 | Zira Island | Azerbaijan | Forest Ecosystem | EL | 48 |

| CS138 | Davis Alpine House in Kew Gardens | London, UK | termite mound | BL | 52 |

| CS139 | Hemisferic | Valencia, Spain | Eyelid | OL | 27 |

An analysis of each case study produced one or more entries in the database, as shown in Table 5; these are the biomimetic strategies that were used in each preceding case. Strategies were categorized according to a number of parameters, including city systems (Energy and Carbon, Water, Waste, Mobility and Transport, Infrastructure and Buildings, Food, Air Quality, Biodiversity and Green Infrastructure, and Governance and Data) and application scale (Urban Scale, Building Scale, and Building Component Scale). These parameters were added in the two rightmost columns. These parameters will play a role in the classification process of the strategies to form a framework for applying them in the built environment across different scales and city systems. Moreover, to link each biomimetic strategy to the corresponding precedent case study or case studies, the case study ID(s) are provided in the middle column. This column acts as the link between both tables to illustrate how they are related.

Each strategy was given an identification code (S###) to facilitate referencing it in the rest of the study. The strategies above represent a set of biomimetic strategies that were applied in the built environment in precedent case studies and can, therefore, represent a guide to architects and planners on how to apply biomimicry in the built environment. However, these applications are on different scales in the built environment. A fraction of these strategies can be applied on a scale as large as a district, neighborhood, or even a city, while others can be applied to a building or a building component. Moreover, the strategies target different aspects of city systems such as energy efficiency, water conservation, material efficiency, data flow, and biodiversity.

6. Discussion

The outcome of the methodology applied is a relational database consisting of three tables (Table 3, Table 4 and Table 5) which are linked together. Table 5 provides the biomimetic strategies that are applicable in the built environment for the design of regenerative, resilient cities, and these strategies are applicable on different scales and through different city systems. Table 4 provides a mapping of best-practice biomimetic case studies in the built environment. The precedent application of any of the strategies from Table 5 can be found in one or more precedent case studies, which can provide a guide to architects and planners on how to successfully apply a certain strategy to the built environment. Therefore, Table 5 and Table 4 were linked together via the case study identification code (CS###) to cross-reference the strategies with their corresponding precedent case studies. Where more information is needed by the architect or planner about a particular case study or a strategy, the source document(s) in Table 3 can be consulted. Accordingly, Table 3 and Table 4 were linked together via the source document ID number to cross-reference the case studies with their corresponding source documents in which they were mentioned and analyzed. How best to organize and use this relational database is the subject of current research by the authors, as will be discussed in the Future Work section.

The diverse parameters included in the database allowed for a multidimensional set of strategies that could be filtered and reordered to provide insights on how to tackle a particular dimension. For instance, all strategies related to energy could be filtered to provide a set of strategies that focus on minimizing energy consumption. Another dimension could be filtering all strategies relating to the applied scale to give guidelines on how to design sustainable buildings, for example. This ontology allows this database to be used in different ways that correspond to the different goals of the architect or planner using the database. This filtering across the application scales and city systems can act as a valuable tool for architects and planners and facilitate the application of biomimetic strategies in the built environment.

An indication of how this will work can be summarized in the following matrix (Table 6), where all biomimetic strategies applicable on a particular scale can be found in the same column, while all strategies addressing a particular urban system can be found in the same row. This classification can make it more accessible to architects and planners to decide on which scale they are tackling and what challenges they are trying to address in their designs, who can, therefore, refer to the relevant biomimetic strategies after getting the strategy codes (S###) from the matrix of Table 6 and cross-referencing them to Table 5 to find the corresponding strategy. For further information on how to apply these strategies, the next step would be to cross-reference the strategies with the corresponding precedent case studies (in Table 4), as explained earlier using the case study ID(s) (CS###). For further details on a case study, a further step would be to cross-reference the case study to the relevant source document in Table 3 using the corresponding source document ID(s).

Table 6.

Biomimetic Strategies Matrix Across Scales and City Systems.

| Urban Scale (U) | Whole Building Scale (B) |

Building Component Scale (C) | |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Energy and Carbon

(EC) |

S002, S003, S004, S005, S006, S009, S010, S011, S012, S013, S015, S019, S020, S021, S022, S023, S024, S025, S026, S029, S035, S036, S037, S038, S050, S065, S076, S111, S113, S114, S116, S122, S129, S130, S169, S170, S179, S181, S182 | S007, S014, S016, S018, S029, S030, S031, S032, S034, S039, S040, S041, S042, S043, S045, S046, S047, S048, S049, S052, S054, S055, S056, S061, S062, S064, S073, S074, S126 | S001, S003, S008, S016, S017, S027, S028, S033, S044, S047, S051, S053, S055, S057, S058, S059, S060, S062, S073, S107 |

|

Water

(WR) |

S128, S134, S135, S136, S148, S151, S153, S156, S158, S159, S160, S161, S162, S163, S164, S166, S167, S168 | S127, S149, S152, S154, S157 | S150, S155, S165 |

|

Waste

(WS) |

S111, S112, S113, S114, S115, S116, S117, S118, S119, S121 | S082, S100, S112, S120 | |

|

Mobility and Transport

(MT) |

S065, S169, S170, S171, S172, 173, S174, S175, S176, S177, S178, S179 | ||

|

Infrastructure and Buildings

(IB) |

S019, S020, S021, S022, S024, S025, S038, S050, S072, S076, S078, S093, S102, S105, S129, S134, S139, S161 | S007, S042, S043, S045, S046, S047, S048, S049, S052, S062, S064, S066, S067, S068, S070, S071, S073, S074, S075, S079, S080, S081, S082, S083, S084, S085, S086, S087, S088, S089, S090, S091, S092, S094, S096, S097, S098, S099, S100, S102, S126 | S001, S044, S047, S051, S062, S063, S069, S073, S081, S095, S101, S103, S104, S106, S107, S108, S109, S110, S123, S141 |

|

Food

(FD) |

S113, S130, S140, S145, S146, S147 | ||

|

Air Quality

(AQ) |

S065, S105, S122, S124, S129, S131, S133, S139, S169, S171 | S040, S041, S126, | S123 |

| Governance and Data (GD) | S077, S093, S112, S121, S128, S143, S144, S180, S181, S182, S183, S184 | S016, S049, S054, S061, S112, S120 | S016, S017, S053, S059 |

| Biodiversity and Green Infrastructure (BG) | S011, S125, S129, S130, S131, S132, S133, S137, S138, S139, S140, S142, S168 | S126, S127 | S141 |

For example, to consider water use at the building scale, one might review one of the five strategies relevant strategies in Table 6 below. If the architect referring to the matrix decides to consider applying strategy S149; fog-catching (highlighted in bold in the matric below), the architect can refer to the relational database for ideas on how to apply this in the building design. Strategy S149 is linked to case studies CS020, CS021, CS024, CS035, CS042, CS107, and CS129 and the source documents 4, 22, 24, 27, 28, 33, 35, 37, 39, 44, and 52. These documents along with the case studies will provide a detailed guide on how to apply fog-catching technologies on the building scale and present previous successes.

It is observed in Table 6 that some cells were empty, presenting no strategies for a particular city system on a particular application scale. This can be due to two reasons. Firstly, certain challenges may only be tackled on a particular scale. For instance, all strategies collected for Mobility and Transport were on the urban scale and none on the other two scales. This can be understood since transport is usually between distant places normally on a scale larger than one building. Secondly, it could be that the collected source documents lacked case studies or strategies for that particular city system and scale, as will be explained in the Limitations section. An example of this is the lack of strategies for Food on the building scale or the building component scale. One might argue that a productive green roof can be a potential strategy to fill this gap, but such a strategy was missing from the collected source documents. The Future Work section will outline how this will be overcome in further research after this study.

7. Conclusions

Architects and planners require great awareness to achieve efficiency and sustainability in buildings, especially in this era when meeting sustainability targets is more critical than in the past. Architects and planners need to rethink the way they build in order to achieve a truly sustainable future. Novel ideas need to be explored and tested; a new design model is needed. The natural world provides an extensive design database that can inspire solutions as sustainable, resilient, and self-perpetuating as those seen in nature. The case studies and strategies presented here are successful precedents biomimetic applications in the built environment. Accumulating and presenting them in this relational database can help to develop wider awareness and understanding of the potential of biomimicry, which can help develop cities that are regenerative and resilient.

The design and management of future cities could also incorporate biomimicry but may have significant barriers due to the wider transdisciplinary nature of the field. While it is true that there is a gap in the biological knowledge of architects and planners, this gap can be bridged by providing a database of biomimetic strategies that have already been successfully applied in the built environment, along with the precedent case studies and source documents to support the understanding of how biomimicry applications can be transferred to the built environment.

Biomimicry, the science of imitating natural models, has good potential when integrated into the design of the built environment. While Benyus suggests that “a full emulation of nature engages at least three levels of mimicry: form, process, and ecosystem” [4], the authors propose a comprehensive vision of applying biomimicry in the built environment on different scales and across all city systems to achieve a regenerative, resilient city.

Ecosystem-level biomimicry gives a more holistic approach to the design of built environments. If applied on an urban scale, it would allow designing better cities that behave like natural ecosystems, and within those ecosystems, architects could also design buildings and building systems that thrive in themselves to achieve higher levels of efficiency in terms of energy, water, and resource use. Moreover, how natural ecosystems respond to place and the local environment is very important in setting design goals in terms of energy, air, water, and carbon budgets for a given design to ensure that cities can behave as a natural ecosystem would behave.

8. Limitations and Future Work

The authors acknowledge that this database is of limited scale, but it is expandable as more strategies or case studies are found. It is also noted that the resultant number and variety of strategies and case studies depended on the criteria put forward to limit the number of source documents that were reviewed. Widening the search scope in the future to include more articles will result in a richer database of case studies and strategies that better cover areas lacking in the biomimetic strategies matrix presented in Table 6.

Since this database is a work in progress that is set to be expanded and developed further in the future, it will be materialized into a digital application to facilitate access to the database. This would also allow for the accumulation of more biomimetic best practice cases in the built environment from architects and planners using this platform.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, O.B. and B.C.; methodology, O.B. and B.C.; formal analysis, O.B.; investigation, O.B.; resources, O.B.; data curation, O.B.; writing—original draft preparation, O.B.; writing—review and editing, O.B., B.C. and D.W.; visualization, O.B.; supervision, B.C. and D.W. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study, in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data, in the writing of the manuscript, or in the decision to publish the results.

Funding Statement

This paper is part of a PhD funded by the MINISTRY OF HIGHER EDUCATION OF THE ARAB REPUBLIC OF EGYPT, grant number NMM13/21.

Footnotes

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content.

References