Abstract

We assessed the immunogenicities and efficacies of two highly attenuated vaccinia virus-derived NYVAC vaccine candidates encoding the human T-cell leukemia/lymphoma virus type 1 (HTLV-1) env gene or both the env and gag genes in prime-boost pilot regimens in combination with naked DNA expressing the HTLV-1 envelope. Three inoculations of NYVAC HTLV-1 env at 0, 1, and 3 months followed by a single inoculation of DNA env at 9 months protected against intravenous challenge with HTLV-1-infected cells in one of three immunized squirrel monkeys. Furthermore, humoral and cell-mediated immune responses against HTLV-1 Env could be detected in this protected animal. However, priming the animal with a single dose of env DNA, followed by immunization with the NYVAC HTLV-1 gag and env vaccine at 6, 7, and 8 months, protected all three animals against challenge with HTLV-1-infected cells. With this protocol, antibodies against HTLV-1 Env and cell-mediated responses against Env and Gag could also be detected in the protected animals. Although the relative superiority of a DNA prime-NYVAC boost regimen over addition of the Gag component as an immunogen cannot be assessed directly, our findings nevertheless show that an HTLV-1 vaccine approach is feasible and deserves further study.

The human T-cell leukemia/lymphoma virus type 1 (HTLV-1) is the causative agent of adult T-cell leukemia (38) and of tropical spastic paraparesis/HTLV-1-associated myelopathy (11). It has also been associated with a number of inflammatory diseases, such as pediatric infectious dermatitis (23), uveitis (26), and some cases of arthropathy (18) and polymyositis (27). The overall prevalence of severe HTLV-1-associated disease is 2 to 8% among HTLV-1-infected persons, estimated to represent 15 to 25 million persons worldwide, mostly in Central and South America, equatorial Africa, and Asia (7). In regions where it is endemic, HTLV-1 is transmitted primarily from mother to child during breast-feeding; later, it is transmitted sexually between adults. In the Western world, the principal routes of infection are parenteral (transfusion and needle sharing among intravenous drug users) and sexual. Mother-to-child transmission should be prevented easily by discouraging breast-feeding, but this has proved to be impossible in areas of endemicity. Campaigns to encourage condom use in some areas of endemicity have also had disappointing results. Thus, the development of an HTLV-1 vaccine appears to be crucial.

Experimental vaccines against HTLV-1 in which the envelope protein was used for immunization have been tested in rabbits, rats, and monkeys. A series of vaccine candidates based on recombinant vaccinia virus vectors containing the HTLV-1 env gene have been tested in rabbits. Two vaccina virus-based recombinants, WR-env17 and WR-proenv1, induced an Env-specific antibody response and were protective (32). WR-SFB5env induced antibodies against gp46 that were not neutralizing and conferred only partial protection (13). We evaluated WR-SFB5env in rats: animals primed and boosted with this recombinant vaccinia virus developed antibodies against the HTLV-1 Env protein and showed partial protection against challenge from HTLV-1-infected MT2 cells (20). Cynomolgus macaques immunized with WR-SFB5env were also protected against challenge (17). Immunization by synthetic peptides with overlapping neutralizing domains in the central region of gp46 protected against challenge in rabbits (33).

The highly attenuated vaccinia virus derivative NYVAC (37) was engineered to express antigens from both animal and human pathogens. NYVAC-based recombinants expressing the rabies virus glycoprotein, a polyprotein from Japanese encephalitis virus, and seven antigens from Plasmodium falciparum were demonstrated to be safe and immunogenic in an initial study with humans (35). NYVAC-based recombinants have also been shown to protect against infection with other retroviruses, such as human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) type 2 and simian immunodeficiency virus (3, 9, 28). When NYVAC containing the HTLV-1 env gene was assessed in rabbits, immunization with this recombinant and boosting with recombinant Env protein protected against challenge from HTLV-1-infected cells. However, 5 months after the initial challenge, the immunized rabbits were not protected against exposure to a large inoculum of blood from an HTLV-1-infected animal (10).

Genetic or DNA-based immunization involves delivery of an immunogen-encoding expression plasmid to a given tissue in vivo to induce an immune response to the encoded immunogen. This novel form of immunization results in the production of correctly folded, glycosylated protein antigens de novo. Indeed, in most studies to date, DNA-based immunization has been found to induce the full range of immune responses, including neutralizing antibodies, a cytotoxic T-cell response (cytotoxic T lymphocytes), and protection against challenge (8, 15). Several DNA vaccines have been shown to be effective in nonhuman primates (4, 24), but in most cases multiple administrations were necessary to induce adequate immunity. Naked DNA has also been used to induce neutralizing antibodies against HTLV-1 Env glycoproteins in mice (1, 12). Although immunization with various naked plasmid constructs containing the env gene under the control of various promoters was not sufficient to elicit specific detectable humoral responses, booster administration with recombinant baculovirus gp62, after priming with the DNA HTLV-1 env gene, resulted in detectable humoral and cell-mediated immune responses.

We showed recently that the squirrel monkey, Saimiri sciureus, a South American primate devoid of endemic infection with simian T-cell leukemia virus, was susceptible to experimental infection with HTLV-1. Experimental inoculation led to chronic infection, similar to that in humans, with high titers of antibodies against HTLV-1 and HTLV-1 provirus being detectable by PCR in peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) for up to 4 years after inoculation (21, 22). The squirrel monkey thus appears to be a suitable model for evaluating candidate HTLV-1 vaccines. The aim of the study reported here was to evaluate the immunogenicity and protective efficacy of a vaccination regimen involving priming with a candidate NYVAC HTLV-1 vaccine and boosting with naked HTLV-1 env DNA in squirrel monkeys.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Vaccine preparations.

Recombinant NYVAC HTLV-1 env candidate vaccines were constructed from a plasmid containing DNA from the HTLV-1 1711 clone, obtained by culture of PBMCs from a West African patient (5). The procedure for generating and analyzing the recombinant NYVAC vaccine expressing the entire HTLV-1 env (gp46 and gp21) gene has been described previously (10). The DNA-based immunogen, consisting of the HTLV-1 env gene and the cytomegalovirus (CMV) promoter and long terminal repeat (CMV-env-LTR), was kindly provided by M.-C. Dokhelar, Institut de Génétique Moléculaire, Paris, France. This plasmid was constructed by Delamarre et al. (6) in order to study the expression of HTLV-1 envelope glycoprotein and its role in cell-to-cell viral transmission. The expression of this plasmid was studied by immunoprecipitation of the envelope glycoprotein from transfected COS-1 cells with sera from HTLV-1-infected individuals. This plasmid has also been studied for its capacity to induce humoral and cell-mediated immune responses against HTLV-1 in mice after boosting with recombinant Env protein (1, 12). Expression of the Env protein with this plasmid was also evaluated in transiently transfected HeLa cells by Western blotting and immunofluorescence. The transfected cells showed a high level of Env protein expression with sera from HTLV-1-infected rabbits. The functional expression of HTLV-1 Env protein was also confirmed by the observation of syncytia in HeLa cells transfected with the same plasmid (1, 12).

Animals, vaccination regimens, and challenge.

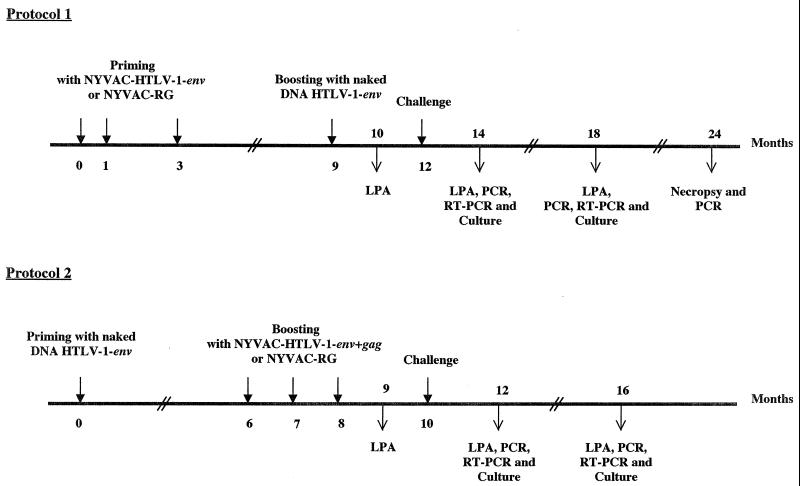

For the vaccination experiments, which complied with French legislation on animal experiments, we used 8-year-old male squirrel monkeys from the primate center of the Pasteur Institute of French Guiana. In the initial protocol (Fig. 1, protocol 1), three monkeys (monkeys 1711, 1811, and 89057) were injected intramuscularly with 108 PFU of NYVAC containing the HTLV-1 env gene at 0, 1, and 3 months. A control monkey (monkey 1495) was similarly injected intramuscularly with 108 PFU of NYVAC-rabies G protein (NYVAC-RG) at the same time. Six months after the last administration of NYVAC-env, two of the three vaccinated monkeys (monkeys 1811 and 89057) were boosted with 500 μg of the naked DNA immunogen CMV-env-LTR intramuscularly into the tibialis anterior muscle. The third monkey (monkey 1711) and the control (monkey 1495) were injected with a naked DNA vector containing the β-galactosidase gene (CMV-βgal) (Table 1).

FIG. 1.

Immunization protocols and challenge. In the first protocol (protocol 1), three monkeys were primed by three intramuscular injections of 108 PFU of NYVAC containing the HTLV-1 env gene. A control monkey was similarly injected with NYVAC-RG. Six months after the last administration of NYVAC-env, two of the three vaccinated monkeys were boosted with 500 μg of naked DNA (CMV-env-LTR) while the third monkey and the control were injected with CMV-βgal. The monkeys were killed 1 year after challenge and examined for the presence of HTLV-1 provirus in various organs. In the second immunization protocol (protocol 2), three monkeys received a single intramuscular injection of 500 μg of CMV-env-LTR DNA and the control monkey received the CMV-βgal vector. Six months later, the three vaccinated monkeys received a series of three booster injections, separated by 1-month intervals, of 108 PFU of the NYVAC-based candidate vaccine containing the HTLV-1 env and gag genes. The control monkey received 108 PFU of NYVAC-RG at the same times. Two months after the last boost, the monkeys were challenged with an intravenous injection of squirrel monkey HTLV-1-producing cells (EVO/798). Before and after challenge, the monkeys were bled each month and their PBMCs were separated on Ficoll plaques. The level of antibodies to HTLV-1 in the sera of immunized animals was evaluated by ELISA and Western blotting, and the presence of an HTLV-1-specific lymphocyte proliferative response (LPA) was evaluated 1 month after the last boost and 2 and 6 months after challenge.

TABLE 1.

Immunization protocols and protective immunity as judged by PCR, RT-PCR, and ELISA at various times after challenge

| Protocol | Monkey | Imunizationa

|

PCRb result after:

|

Result after culture for 1 mo at both 2 and 6 mo by:

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Priming | Boosting | 24 h | 2 mo | 6 mo | RT-PCRc | ELISAd | ||

| 1 | 1711 | env | CMV-βgal | + | + | + | + | + |

| 1811 | env | CMV-env-LTR | + | − | − | − | − | |

| 89057 | env | CMV-env-LTR | + | + | + | + | + | |

| 1495 | RG | CMV-βgal | + | + | + | + | + | |

| 2 | 93081 | CMV-env-LTR | env + gag | + | − | − | − | − |

| 93089 | CMV-env-LTR | env + gag | + | − | ND | −e | −e | |

| 93096 | CMV-env-LTR | env + gag | + | − | − | − | − | |

| 93116 | CMV-βgal | RG | + | + | + | + | + | |

Monkeys were primed with NYVAC-env and boosted with naked env DNA (protocol 1) or primed with naked env DNA and boosted with NYVAC-env and gag (protocol 2). In protocol 1, priming was with NYVAC at 0, 1, and 3 months and boosting was with naked DNA at 9 months. In protocol 2, priming was with naked DNA at time zero and boosting was with NYVAC at 6, 7, and 8 months. ND, not determined.

To detect HTLV-1 provirus using gag and pol primers.

To detect HTLV-1 provirus expression (tax, rex mRNA).

To detect HTLV-1 p19 antigen.

Result only for 2 months after challenge.

In the second immunization protocol (Fig. 1, protocol 2), three monkeys (monkeys 93081, 93089, and 93096) received single intramuscular injections of 500 μg of the DNA immunogen CMV-env-LTR and the control monkey (monkey 93116) was injected with the CMV-βgal vector. Six months later, the three vaccinated monkeys received a series of three booster injections, separated by 1-month intervals, of 108 PFU of the NYVAC-based candidate vaccine containing the HTLV-1 env and gag genes. The control monkey received 108 PFU of NYVAC-RG at the same times (Table 1).

The vaccinated monkeys were challenged 2 months after being boosted with an intravenous injection of 5 × 107 squirrel monkey HTLV-1-transformed and -producing cells (EVO/798) by a previously described protocol (21, 22). Four control monkeys (monkeys 86021, 92039, 1491, and 1657) infected with HTLV-1 but not vaccinated with any recombinant used in the two immunization regimens were also included in the study.

Serological and molecular biology assays.

At various times after challenge, the serum levels of specific HTLV-1 antibodies were determined by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) (Cobas Core Anti-HTLV-I/II enzyme immunoassay; Roche, Basel, Switzerland) and confirmed by Western blot analysis (HTLV-1; 2.3 Diagnostic Biotechnology, Singapore). We also tested genomic DNA extracted from PBMCs for the presence of HTLV-1 sequences, as described by Ibrahim et al. (16). PCR was performed as previously described with the gag-specific primers gag1 and gag2 (19) or the pol-specific primers SK54 and PolAG2 (16). The amplified products were subjected to electrophoresis in a 1.4% agarose gel, transferred to nylon membranes, and hybridized with 32P-labeled internal oligonucleotide probes specific for the gag (5′ GCAAAGGTACTGCAGGAGGT 3′ ) and pol (5′ TTCCAGCCCTACTTTGCTTTCACTGTCCC 3′ ) sequences. The membranes were washed and placed against Hyperfilm MP (Amersham, Little Chalfont, Buckinghamshire, United Kingdom) at −80°C for 24 h and then against a second film for 1 week.

The presence of HTLV-1 provirus was evaluated in PBMCs from the challenged monkeys 2 and 6 months after challenge, after 1 month of in vitro culture by ELISA for the presence of HTLV-1 p19 antigen (ZeptoMetrix, Buffalo, N.Y.), or by seminested reverse transcription (RT)-PCR in the pX region, with RPX3 and RPX5 as the external primers and RPX3 and RPX4 as the internal primers, as previously described by Kazanji et al. (22).

Lymphocyte proliferation assays.

PBMCs were collected from the eight immunized monkeys 1 month after the last boost and 2 and 6 months after challenge (Fig. 1). The PBMCs were separated on Ficoll plaques and suspended at a concentration of 5 × 106 per ml in RPMI 1640 medium containing 10% fetal calf serum supplemented with glutamine (2 mmol/liter), penicillin (50 IU/ml), and streptomycin (50 μg/ml). The remaining cells were added to triplicate wells (2 × 105 cells per well) in 96-well round-bottom microtiter plates (Costar; Corning, Inc., Corning, N.Y.) and incubated for 5 days in a final volume of 200 μl at 37°C in 5% CO2 in the presence or absence of 1 μg of recombinant HTLV-1 Env gp46 protein per well corresponding to amino acids 16 to 312 (Intracel, London, United Kingdom) or two HTLV-1 Gag peptides (amino acids 110 to 130 and 175 to 191) corresponding, respectively, to portions of the HTLV-1 p19 and p24 Gag proteins (ABTeurope, London, United Kingdom). Phytohemagglutinin was used as a positive control, and cells were incubated with 4 μg of this nonspecific mitogen per ml for 24 h. Recombinant Schistosoma japonicum glutathione transferase and HIV peptide corresponding to a portion of the Env protein (V3 loop region) were used as negative controls. After stimulation, the wells were pulsed for 12 h with 0.5 μCi of [3H]thymidine (Amersham, Les Ulis, France); the cells were then lysed, and 3H incorporation was measured in a liquid scintillation counter (Rackbeta 1209-b; LKB/Wallac, Turku, Finland).

RESULTS

Protocol 1.

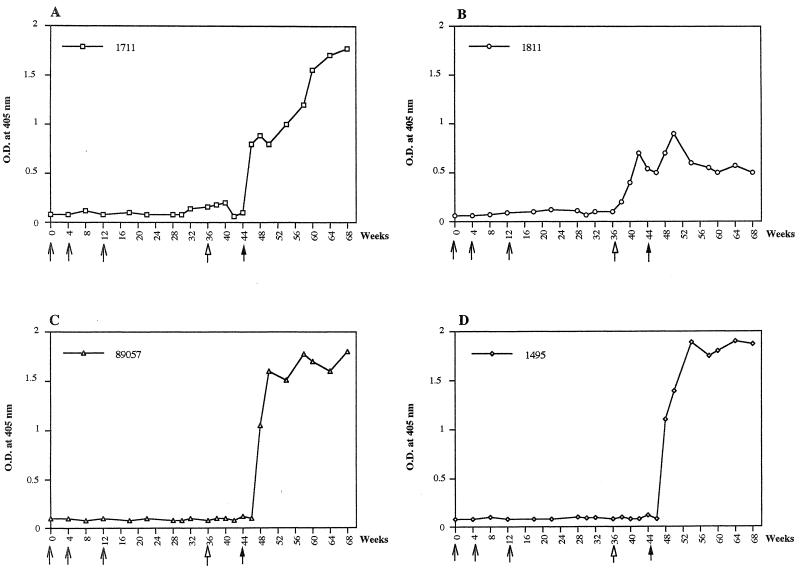

With the first immunization protocol, no antibodies against HTLV-1 Env protein were detected in any of the three vaccinated animals after three administrations of the NYVAC–HTLV-1 env vaccine preparation (Fig. 2). However, one of the two animals boosted with CMV-env-LTR (monkey 1811) developed a serum antibody response 2 weeks after being boosted (Fig. 2B and 3).

FIG. 2.

Antibody responses to HTLV-1, as detected by ELISA, before and after challenge in monkeys immunized with NYVAC-env and boosted with naked DNA containing the HTLV-1 env gene. (A, B, and C) Results with monkeys 1711, 1811, and 89057, respectively; (D) control monkey 1495, which was first injected with NYVAC-RG and then boosted with CMV-βgal. Arrows denote times of vaccination, and the filled arrows indicate times of challenge. O.D., optical density.

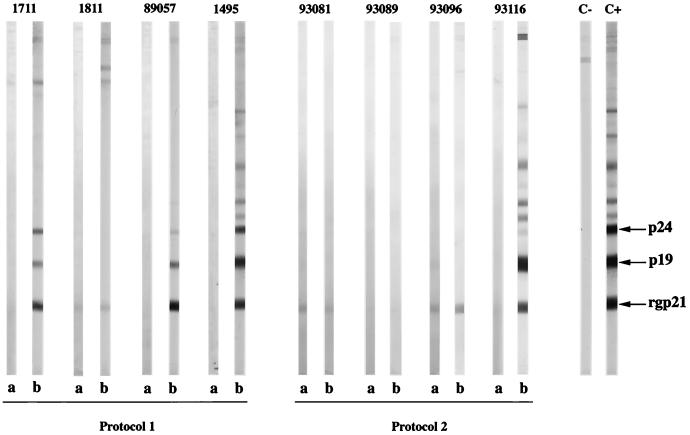

FIG. 3.

Western blot analysis of sera from immunized monkeys before and after challenge with HTLV-1-producing cells. (Protocol 1) Western blot pattern for monkeys immunized with NYVAC-env and boosted with naked DNA containing the HTLV-1 env gene. Lanes a, Western blot pattern 1 month after the last boost (before challenge); lanes b, Western blot pattern 2 months after challenge. Monkey 1711 was immunized with NYVAC–HTLV-1 env and boosted with naked CMV-βgal DNA, monkeys 1811 and 89057 were immunized with NYVAC–HTLV-1 env and boosted with naked CMV-env-LTR DNA, and control monkey 1495 was injected with NYVAC-RG and boosted with naked CMV-βgal DNA. (Protocol 2) Western blot pattern for monkeys primed with naked DNA (CMV-env-LTR) and boosted with NYVAC containing the HTLV-1 env and gag genes. Lanes a, Western blot pattern 1 month after the last boost (before challenge); lanes b, Western blot pattern 2 months after challenge. Monkeys 93081, 93089, and 93096 were first immunized with naked CMV-env-LTR DNA and then boosted three times with the NYVAC–HTLV-1 env and gag vaccine preparation; control monkey 93116 was injected with naked CMV-βgal DNA and boosted with NYVAC-RG. Lane C−, Western blot pattern for HTLV-1-negative control monkey; lane C+, Western blot pattern for HTLV-1-positive control monkey.

Six months after challenge, seroconversion was observed in two of the three vaccinated animals and in the control (Fig. 2 and 3) but no anti-Tax or anti-Gag antibodies were detected in one vaccinated animal (monkey 1811) 2 or 6 months after challenge or thereafter (Fig. 3). At 2 and 6 months after challenge, gag-specific sequences were detected by PCR in PBMCs from the seroconverted monkeys and the control (monkeys 1711, 89057, and 1495) but no HTLV-1 sequences were detected in animal 1811. When PBMCs were isolated from all monkeys 2 and 6 months after challenge, both ex vivo and cultured PBMCs from the two seroconverted monkeys and the control monkey tested positive for tax/rex mRNA and HTLV-1 p19 antigen by seminested RT-PCR and ELISA. In similar samples from animal 1811, neither tax/rex mRNA nor HTLV-1 p19 was detected (Table 1). In addition, PBMCs and various tissue samples obtained at necropsy 1 year after challenge showed the presence of these HTLV-1-specific gene products in the two monkeys that seroconverted and in the control but not in monkey 1811.

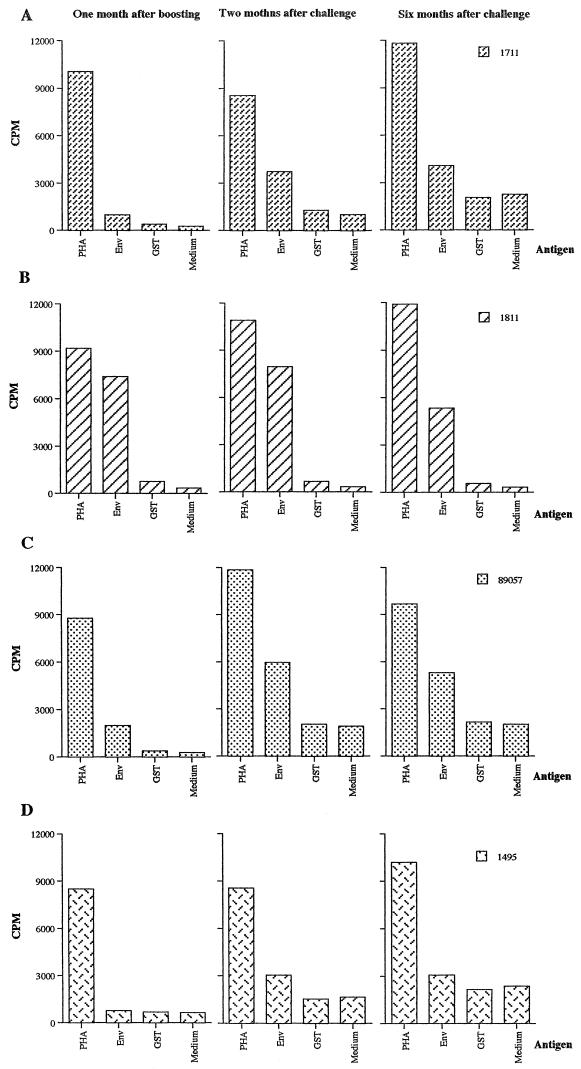

In the lymphocyte proliferation test, performed 1 month after the last boost, an intense positive signal was found with recombinant Env gp46 protein in the animal that did not seroconvert after challenge and very low or no positive signals were found in the three other monkeys (Fig. 4). Two months after challenge, the lymphocyte proliferation response against HTLV-1 Env gp46 was stimulated in all of the three immunized monkeys and a lesser response was stimulated in the control monkey. Six months after challenge, the lymphocyte proliferation response was detected in all monkeys but at a lower level than at 2 months (Fig. 4).

FIG. 4.

Lymphocyte proliferation responses before and after challenge in monkeys primed with NYVAC-env and boosted with naked DNA containing the HTLV-1 env gene. PBMCs were assayed for the proliferative response to HTLV-1 Env (gp46) protein, as described in the text. CPM, counts per minute of [3H]thymidine incorporated in the presence or absence of the antigens. Results are shown for triplicate wells. Phytohemagglutinin (PHA) was used as a positive control, and glutathione S-transferase (GST) and medium alone were used as negative controls. Monkey 1495 is a control animal.

Protocol 2.

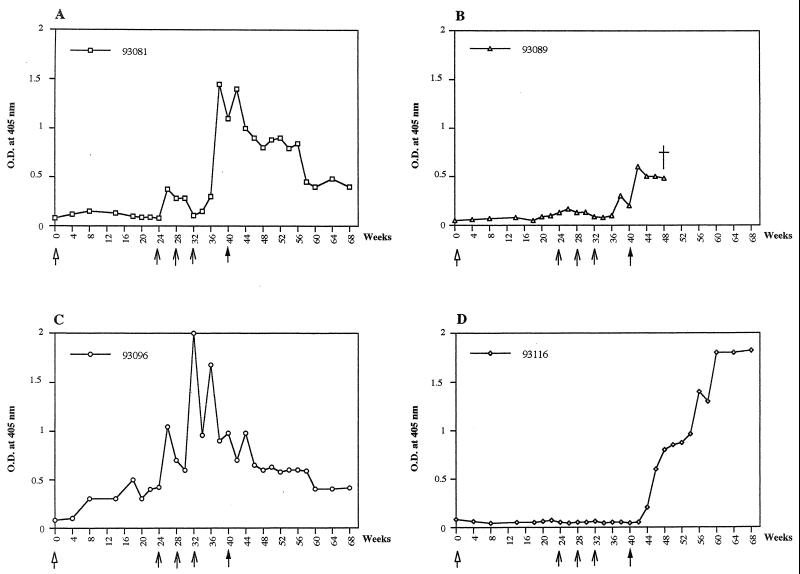

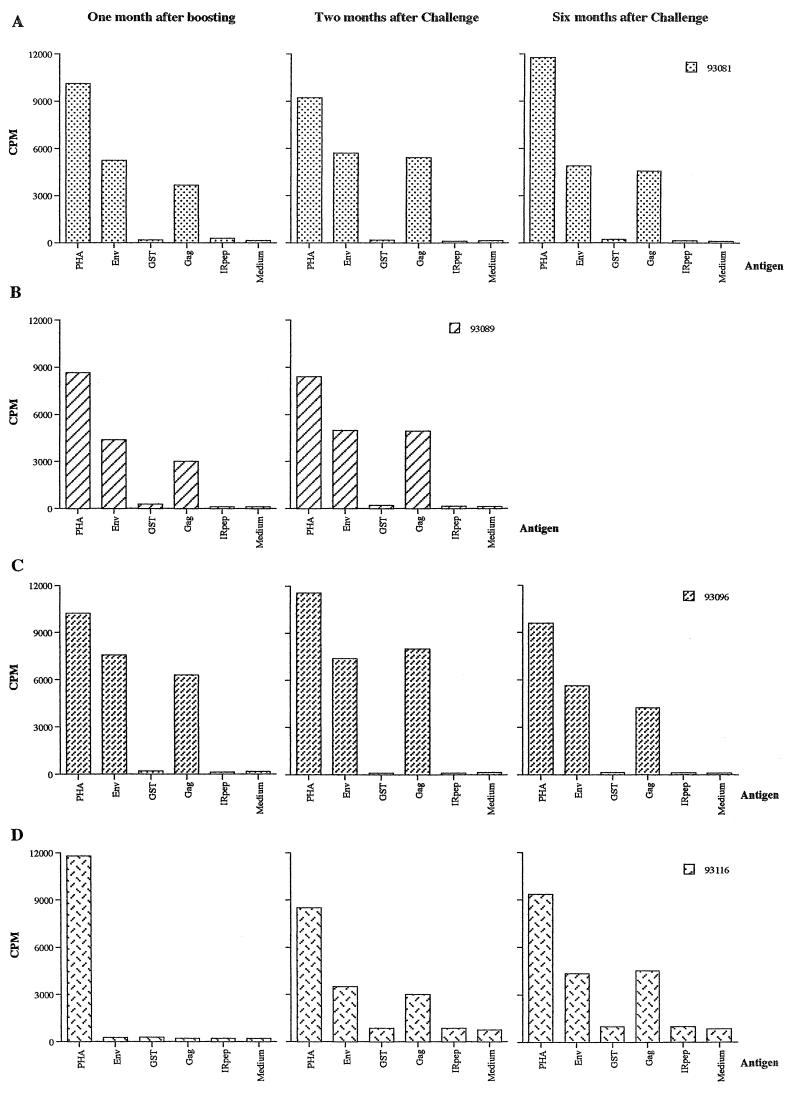

With the second immunization protocol, injection of CMV-env-LTR did not induce detectable levels of antibodies against HTLV-1 Env protein in any of the three vaccinated animals. In contrast, after being boosted with three injections of NYVAC containing the HTLV-1 env and gag genes, two of three boosted animals (monkeys 93081 and 93096) developed an antibody response to HTLV-1, as detected by ELISA (Fig. 5). In these two animals, anti-Env antibodies were also detected by Western blotting (Fig. 3). Two months after challenge, seroconversion against HTLV-1 was detected only in the control animal (monkey 93116) (Fig. 3 and 5D). One of the three vaccinated animals (animal 93089) died 2 months after challenge from clinically and pathologically confirmed acute renal failure. At necropsy, HTLV-1 provirus was not detected by PCR in the spleen, lymph nodes, liver, lung, kidney, or brain or in any other part of the central nervous system. When PBMCs from this animal were cultured, no markers of HTLV-1 infection could be detected by PCR or RT-PCR and Gag p19 was not found in the culture. No antibodies to Tax or Gag were detected in the other vaccinated animals (animals 93081 and 93096) 2 or 6 months after challenge or thereafter. pol-specific sequences were detected by PCR 2 or 6 months after challenge in PBMCs from the control animal but were not found in the vaccinated animals, and only PBMCs from the control monkey tested positive for tax/rex mRNA and HTLV-1 p19 (Table 1). In the lymphocyte proliferation test performed 1 month after boosting, high-level, specific responses were detected in the three immunized animals against both recombinant Env gp46 protein and Gag peptides but not in the control monkey (Fig. 6). This positive signal appeared to be directed more strongly against Env than against Gag. In contrast, the positive responses were similar in all immunized monkeys 2 months after challenge and could be maintained for 6 months (Fig. 6). In the control monkey, no lymphocyte proliferation response was observed before challenge but 2 and 6 months after challenge a cell-mediated immune response was detected (Fig. 6D).

FIG. 5.

Antibody responses to HTLV-1, as detected by ELISA, before and after challenge in monkeys primed with naked DNA (CMV-env-LTR) containing the HTLV-1 env gene and boosted three time with NYVAC containing the HTLV-1 env and gag genes. (A, B, and C) Results with monkeys 93081, 93096, and 93089, respectively; (D) results with the control monkey 93116, which was was first injected with CMV-βgal and then boosted with NYVAC-RG. Arrows denote times of vaccination, and filled arrows indicate the time of challenge. O.D., optical density.

FIG. 6.

Lymphocyte proliferation responses before and after challenge in monkeys primed with naked DNA (CMV-env-LTR) containing the HTLV-1 env gene and boosted with NYVAC containing the HTLV-1 env and gag genes. PBMCs were assayed for the proliferative response to HTLV-1 Env (gp46) protein and to two Gag peptides (p19 and p24), as described in the text. Phytohemagglutinin (PHA) was used as a positive control, and glutathione S-transferase (GST), an irrelevant peptide (IRpep), and medium alone were used as negative controls. Monkey 93116 is a control animal. CPM, counts per minute.

DISCUSSION

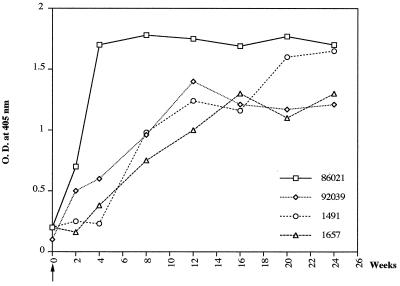

In this study, we found that a vaccination regimen involving priming with naked DNA and boosting with NYVAC containing the HTLV-1 env and gag genes was more efficient in eliciting HTLV-1-specific antibody and cell-mediated responses and protective immunity against HTLV-1 than a regimen involving priming with NYVAC-env and boosting with naked DNA. With the latter protocol, only one of the three immunized animals was protected, and humoral and cell-mediated immune responses to HTLV-1 Env were detected. The curves for HTLV-1 seroconversion during the 6 months after HTLV-1 inoculation (challenge) of control monkeys and unprotected animals were similar to those observed for four nonimmunized control monkeys infected with HTLV-1 (Fig. 7). This comparison showed that protection was achieved in the immunized monkeys.

FIG. 7.

Antibody responses to HTLV-1, as detected by ELISA, in four nonimmunized control monkeys infected with HTLV-1. The arrow indicates the time of HTLV-1 inoculation. O.D., optical density.

The Env protein has been reported to confer partial protection against HTLV-1 infection in various animal models, but the mechanisms of immunity associated with the protection remain unclear. In particular, protection has been observed in the absence of an antibody response (10, 20), suggesting that cell-mediated immunity plays a key role. We used the recombinant NYVAC vaccine containing a Gag component in the second immunization protocol for the following reasons. First, rats inoculated with HTLV-1-transformed rat cells have been shown to develop cytotoxic T lymphocytes directed against Gag-specific epitopes rather than against Env-specific epitopes (29, 34). Second, vaccines containing Gag or Gag and Env have been shown to protect against Moloney and Friend murine leukemia viruses in mice (25, 30) and against feline leukemia virus in cats (36). In our squirrel monkey model, we found that monkeys primed with naked DNA and boosted with NYVAC containing the env and gag genes developed a humoral response to HTLV-1 after each boost and a cell-mediated immune response to Env and Gag after being boosted and challenged. Furthermore, these monkeys were protected against HTLV-1 challenge. Similar results were obtained by Hanke et al. (14), who showed that a combined immunization regimen involving priming with a DNA immunogen and boosting with the modified Ankara vaccina virus resulted in a more potent immune response, as determined by epitope-specific gamma interferon production and a cytotoxic T-lymphocyte response.

The combination of a recombinant virus and naked DNA containing the HTLV-1 env gene has also been tested in rats. HTLV-1-specific cytotoxic T lymphocytes were recovered from rats immunized with recombinant adenovirus 5 and boosted with naked DNA containing the HTLV-1 env gene (20). More recently, Robinson et al. (31) compared eight immunization protocols in rhesus macaques and found that the most promising protocol for protection against HIV was priming with naked DNA and boosting with recombinant vaccinia virus. This protection did not require neutralizing antibody production but was effective for a series of challenges.

Indeed, the ideal vaccine should induce long-lasting neutralizing antibodies to HTLV-1 in serum and a strong cell-mediated immune response. These conditions might be difficult to achieve with a single vaccine preparation, because the optimal immunization regimens for inducing humoral and cell-mediated immunity are often different. A cytotoxic T-lymphocyte response directed mainly against p40tax protein is detected in asymptomatic human HTLV-1 carriers and in patients with tropical spastic paraparesis/HTLV-1-associated myelopathy. Bangham et al. (2) suggested that this response plays a major role in controlling HTLV-1 replication. A mutated tax might therefore also be included in the vaccine preparation to increase the breadth of the immune response against HTLV-1. Alternatively, separate immunization with naked DNA containing env, gag, and tax may be necessary, followed by boosting with live recombinant vector-based candidates or with recombinant subunit vaccine preparations in an appropriate adjuvant. As we have shown in this study, this approach is promising for the induction of sustained levels of both humoral and cell-mediated immunity.

In conclusion, our results show that the second vaccination protocol used protected squirrel monkeys against HTLV-1 infection. Future efforts should be directed to elucidating the qualitative aspects and the duration of this protection.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank J. F. Pouliquen and E. Bourreau for technical assistance and the Director of the Institut Pasteur of French Guiana, J.-L. Sarthou, for support and encouragement.

We also thank the Association pour la Recherche contre le Cancer (ARC), La Fondation pour la Recherche Médicale (FRM/SIDACTION), and the Virus Cancer Prévention (VCP) association for financial support. Part of this study was supported by a grant from the Ministère de la Recherche (Programme de Recherche Fondamentale en Microbiologie des Maladies Infectieuses et Parasitaires), which is gratefully acknowledged.

REFERENCES

- 1.Armand M A, Grange M P, Paulin D, Desgranges C. Targeted expression of HTLV-I envelope proteins in muscle by DNA immunization of mice. Vaccine. 2000;18:2212–2222. doi: 10.1016/s0264-410x(99)00565-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bangham C, Kermode A G, Hall S E, Daenke S. The cytotoxic T-lymphocyte response to HTLV-I: the main determinant of disease. Semin Virol. 1996;7:41–48. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Benson J, Chougnet C, Robert-Guroff M, Montefiori D, Markham P, Shearer G, Gallo R C, Cranage M, Paoletti E, Limbach K, Venzon D, Tartaglia J, Franchini G. Recombinant vaccine-induced protection against the highly pathogenic simian immunodeficiency virus SIV(mac251): dependence on route of challenge exposure. J Virol. 1998;72:4170–4182. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.5.4170-4182.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Boyer J D, Ugen K E, Wang B, Agadjanyan M, Gilbert L, Bagarazzi M L, Chattergoon M, Frost P, Javadian A, Williams W V, Refaeli Y, Ciccarelli R B, McCallus D, Coney L, Weiner D B. Protection of chimpanzees from high-dose heterologous HIV-1 challenge by DNA vaccination. Nat Med. 1997;3:526–532. doi: 10.1038/nm0597-526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cardoso E A, Robert-Guroff M, Franchini G, Gartner S, Moura-Nunes J F, Gallo R C, Terrinha A M. Seroprevalence of HTLV-I in Portugal and evidence of double retrovirus infection of a healthy donor. Int J Cancer. 1989;43:195–200. doi: 10.1002/ijc.2910430204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Delamarre L, Rosenberg A R, Pique C, Pham D, Dokhelar M C. A novel human T-leukemia virus type 1 cell-to-cell transmission assay permits definition of SU glycoprotein amino acids important for infectivity. J Virol. 1997;71:259–266. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.1.259-266.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.de Thé G, Kazanji M. An HTLV-I/II vaccine: from animal model to clinical trials? J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr Hum Retrovirol. 1996;13:191–198. doi: 10.1097/00042560-199600001-00029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Donnelly J J, Ulmer J B, Shiver J W, Liu M A. DNA vaccines. Annu Rev Immunol. 1997;15:617–648. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.15.1.617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Franchini G, Robert-Guroff M, Tartaglia J, Aggarwal A, Abimiku A, Benson J, Markham P, Limbach K, Hurteau G, Fullen J, Aldrich K, Miller N, Sadoff J, Paoletti E, Gallo R C. Highly attenuated HIV type 2 recombinant poxviruses, but not HIV-2 recombinant Salmonella vaccines, induce long-lasting protection in rhesus macaques. AIDS Res Hum Retrovir. 1995;11:909–920. doi: 10.1089/aid.1995.11.909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Franchini G, Tartaglia J, Markham P, Benson J, Fullen J, Wills M, Arp J, Dekaban G, Paoletti E, Gallo R C. Highly attenuated HTLV type I env poxvirus vaccines induce protection against a cell-associated HTLV type I challenge in rabbits. AIDS Res Hum Retrovir. 1995;11:307–313. doi: 10.1089/aid.1995.11.307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gessain A, Barin F, Vernant J C, Gout O, Maurs L, Calender A, de The G. Antibodies to human T-lymphotropic virus type-I in patients with tropical spastic paraparesis. Lancet. 1985;ii:407–410. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(85)92734-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Grange M P, Armand M A, Audoly G, Thollot D, Desgranges C. Induction of neutralizing antibodies against HTLV-I envelope proteins after combined genetic and protein immunizations in mice. DNA Cell Biol. 1997;16:1439–1448. doi: 10.1089/dna.1997.16.1439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hakoda E, Machida H, Tanaka Y, Morishita N, Sawada T, Shida H, Hoshino H, Miyoshi I. Vaccination of rabbits with recombinant vaccinia virus carrying the envelope gene of human T-cell lymphotropic virus type I. Int J Cancer. 1995;60:567–570. doi: 10.1002/ijc.2910600423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hanke T, Blanchard T J, Schneider J, Hannan C M, Becker M, Gilbert S C, Hill A V, Smith G L, McMichael A. Enhancement of MHC class I-restricted peptide-specific T cell induction by a DNA prime/MVA boost vaccination regime. Vaccine. 1998;16:439–445. doi: 10.1016/s0264-410x(97)00226-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hassett D E, Whitton J L. DNA immunization. Trends Microbiol. 1996;4:307–312. doi: 10.1016/0966-842x(96)10048-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ibrahim F, Fiette L, Gessain A, Buisson N, de Thé G, Bomford R. Infection of rats with human T-cell leukemia virus type-I: susceptibility of inbred strains, antibody response and provirus location. Int J Cancer. 1994;58:446–451. doi: 10.1002/ijc.2910580324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ibuki K, Funahashi S I, Yamamoto H, Nakamura M, Igarashi T, Miura T, Ido E, Hayami M, Shida H. Long-term persistence of protective immunity in cynomolgus monkeys immunized with a recombinant vaccinia virus expressing the human T cell leukaemia virus type I envelope gene. J Gen Virol. 1997;78:147–152. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-78-1-147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ijichi S, Matsuda T, Maruyama I, Izumihara T, Kojima K, Niimura T, Maruyama Y, Sonoda S, Yoshida A, Osame M. Arthritis in a human T-lymphotropic virus type-I (HTLV-I) carrier. Ann Rheum Dis. 1990;49:718–721. doi: 10.1136/ard.49.9.718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kawase K, Katamine S, Moriuchi R, Miyamoto T, Kubota K, Igarashi H, Doi H, Tsuji Y, Yamabe T, Hino S. Maternal transmission of HTLV-I other than through breast milk: discrepancy between the polymerase chain reaction positivity of cord blood samples for HTLV-I and the subsequent seropositivity of individuals. Jpn J Cancer Res. 1992;83:968–977. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.1992.tb02009.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kazanji M, Bomford R, Bessereau J L, Schulz T, de Thé G. Expression and immunogenicity in rats of recombinant adenovirus 5 DNA plasmids and vaccinia virus containing the HTLV-I env gene. Int J Cancer. 1997;71:300–307. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0215(19970410)71:2<300::aid-ijc27>3.0.co;2-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kazanji M, Moreau J P, Mahieux R, Bonnemains B, Bomford R, Gessain A, de Thé G. HTLV-I infection in squirrel monkey (Saïmiri sciureus) using autologous, homologous or heterologous HTLV-I-transformed cell lines. Virology. 1997;231:258–266. doi: 10.1006/viro.1997.8528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kazanji M, Ureta-Vidal A, Ozden S, Tangy F, de Thoisy B, Fiette L, Talarmin A, Gessain A, de Thé G. Lymphoid organs as a major reservoir for human T-cell leukemia virus type 1 in experimentally infected squirrel monkeys (Saimiri sciureus): provirus expression, persistence, and humoral and cellular immune responses. J Virol. 2000;74:4860–4867. doi: 10.1128/jvi.74.10.4860-4867.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lagrenade L, Hanchard B, Fletcher V, Cranston B, Blattner W. Infective dermatitis of Jamaican children—a marker for HTLV-I infection. Lancet. 1990;336:1345–1347. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(90)92896-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Letvin N L, Montefiori D C, Yasutomi Y, Perry H C, Davies M E, Lekutis C, Alroy M, Freed D C, Lord C I, Handt L K, Liu M A, Shiver J W. Potent, protective anti-HIV immune responses generated by bimodal HIV envelope DNA plus protein vaccination. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:9378–9383. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.17.9378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Miyazawa M, Nishio J, Cheseboro B. Protection against Friend retrovirus-induced leukemia by recombinant vaccinia viruses expressing the gag gene. J Virol. 1992;66:4497–4507. doi: 10.1128/jvi.66.7.4497-4507.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mochizuki M, Yamaguchi K, Takatsuki K, Watanabe T, Mori S, Tajima K. HTLV-I and uveitis. Lancet. 1992;339:1110. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(92)90699-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Morgan O, Rodgers-Johnson P, Mora C, Char G. HTLV-I and polymyositis in Jamaica. Lancet. 1989;ii:1184–1186. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(89)91793-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Myagkikh M, Alipanah S, Markham P D, Tartaglia J, Paoletti E, Gallo R C, Franchini G, Robert-Guroff M. Multiple immunizations with attenuated poxvirus HIV type 2 recombinants and subunit boosts required for protection of rhesus macaques. AIDS Res Hum Retrovir. 1996;12:985–992. doi: 10.1089/aid.1996.12.985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Noguchi Y, Tateno M, Kondo N, Yoshiki T, Shida H, Nakayama E, Shiku H. Rat cytotoxic T lymphocytes against human T-lymphotropic virus type I-infected cells recognize gag gene and env gene encoded antigens. J Immunol. 1989;143:3737–3742. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Plata F, Langlade-Demoyen P, Abastado J P, Berbar T, Kourilsky P. Retrovirus antigens recognized by cytotoxic T lymphocytes activate tumor rejection in vivo. Cell. 1987;48:231–240. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(87)90426-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Robinson H L, Montefiori D C, Johnson R P, Manson K H, Kalish M L, Lifson J D, Rizvi T A, Lu S, Hu S L, Mazzara G P, Panicali D L, Herndon J G, Glickman R, Candido M A, Lydy S L, Wyand M S, McClure H M. Neutralizing antibody-independent containment of immunodeficiency virus challenges by DNA priming and recombinant pox virus booster immunizations. Nat Med. 1999;5:526–534. doi: 10.1038/8406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Shida H, Tochikura T, Sato T, Konno T, Hirayoshi K, Seki M, Ito Y, Hatanaka M, Hinuma Y, Sugimoto M, Takahashi-Nishimaki F, Maruyama T, Miki K, Suzuki K, Morita M, Sashiyama H, Hayami M. Effect of the recombinant vaccinia viruses that express HTLV-I envelope gene on HTLV-I infection. EMBO J. 1987;6:3379–3384. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1987.tb02660.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tanaka Y, Tanaka R, Terada E, Koyanagi Y, Miyano-Kurosaki N, Yamamoto N, Baba E, Nakamura M, Shida H. Induction of antibody responses that neutralize human T-cell leukemia virus type I infection in vitro and in vivo by peptide immunization. J Virol. 1994;68:6323–6331. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.10.6323-6331.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tanaka Y, Tozawa H, Koyanagi Y, Shida H. Recognition of human T cell leukemia virus type I (HTLV-I) gag and pX gene products by MHC-restricted cytotoxic T lymphocytes induced in rats against syngeneic HTLV-I-infected cells. J Immunol. 1990;144:4202–4211. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tartaglia J, Cox W I, Pincus S, Paoletti E. Safety and immunogenicity of recombinants based on the genetically-engineered vaccinia strain, NYVAC. Dev Biol Stand. 1994;82:125–129. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tartaglia J, Jarrett O, Neil J C, Desmettre P, Paoletti E. Protection of cats against feline leukemia virus by vaccination with a canarypox recombinant, ALVAC-FL. J Virol. 1993;67:2370–2375. doi: 10.1128/jvi.67.4.2370-2375.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tartaglia J, Perkus M E, Taylor J, Norton E K, Audonnet J C, Cox W I, Davis S W, van der Hoeven J, Meignier B, Riviere M. NYVAC: a highly attenuated strain of vaccinia virus. Virology. 1992;188:217–232. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(92)90752-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yoshida M, Seiki M, Yamaguchi K, Takatsuki K. Monoclonal integration of human T-cell leukemia provirus in all primary tumors of adult T-cell leukemia suggests causative role of human T-cell leukemia virus in the disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1984;81:2534–2537. doi: 10.1073/pnas.81.8.2534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]