Abstract

Socioeconomic differences in health risk behaviours during pregnancy may be influenced by social relations. In this study, we aimed to investigate if social need fulfillment moderates the association between socioeconomic status (SES) and health risk behaviours (smoking and/or alcohol consumption) during pregnancy. We used baseline data from the Lifelines Cohort Study merged with data from the Lifelines Reproductive Origin of Adult Health and Disease (ROAHD) cohort. Education level was used to determine SES, categorized into low, middle, and high, with middle SES as the reference category. Social need fulfillment was taken as indicator for social relations and was measured with the validated Social Production Function Instrument for the Level of Well-being scale. The dependent variable was smoking and/or alcohol consumption during pregnancy. Univariable and multivariable logistic regression analysis was conducted to assess the association of SES and social need fulfillment with health risk behaviours and to test for effect modification. We included 1107 pregnant women. The results showed that women with a high SES had statistically significantly lower odds of health risk behaviours during pregnancy. The interaction effect between SES and social need fulfillment on health risk behaviours was not statistically significant, indicating that no moderation effect is present. The results indicate that social need fulfillment does not modify the effect of SES on health risk behaviours during pregnancy. However, in literature, social relations are identified as an important influence on health risk behaviours. More research is needed to identify which measure of social relations is the most relevant regarding the association with health risk behaviours.

Introduction

In the Netherlands, 8% of women smoke during (part of) their pregnancy and 2.6% consume alcohol during pregnancy [1]. Women who smoke or consume alcohol tend to engage in other health risk behaviours during pregnancy, such as an unhealthy diet and inadequate folic acid intake [2]. These health risk behaviours are associated with adverse outcomes, such as low birthweight, preterm birth, and miscarriage [3, 4].

Health risk behaviours during pregnancy are associated with socioeconomic status (SES), where women with a lower SES are at greater risk of continuation of unhealthy behaviours during pregnancy compared to women with higher SES [5]. Socioeconomic differences in health behaviours during pregnancy may be explained by psychosocial stress and available resources [2, 6]. Women with a lower SES tend to have fewer resources, such as income, knowledge, and social support, compared to women with higher SES [7]. Lacking these resources increases psychosocial stress and may make individuals at greater risk to turn to unhealthy behaviours to cope with psychosocial stress [7]. One study reported that stress is a mediator between lower SES and postpartum smoking relapse [8]. Studies on the pathways between SES and the consumption of alcohol during pregnancy are scarce; one study reports that women consume alcohol during pregnancy as a mechanism to cope with stress [9].

Social relations may positively help manage psychosocial stress. Previous studies stated that social relations play an important role in socioeconomic differences in health behaviours [7, 10]. Social relations may function as a buffer against psychosocial stress and thereby have a positive influence on health behaviours [11, 12]. On the other hand, social relations might negatively influence health behaviours. Women who smoke often have many smokers in their social networks, which influences women’s attitudes towards smoking during pregnancy [13].

The mechanism could be different for pregnant women compared to the general population, because pregnant women are also responsible for the health of their unborn child. Putatively, this new responsibility for the unborn makes women more dependent on social support to cope with general and pregnancy-related stress [8]. There are limited studies that examined the moderating effect of social relations on the association between SES and health behaviours during pregnancy. One previous study investigated pathways between SES and smoking during pregnancy [14]. This study did not report evidence in favour of the moderating effect of social relations. This study used the quality of the primary intimate relationship as operationalization for social relationships and had smoking in the third trimester as outcome [14]. The results of another study, not performed among pregnant women, indicated that social support may act as a buffer for stress and problem drinking [15].

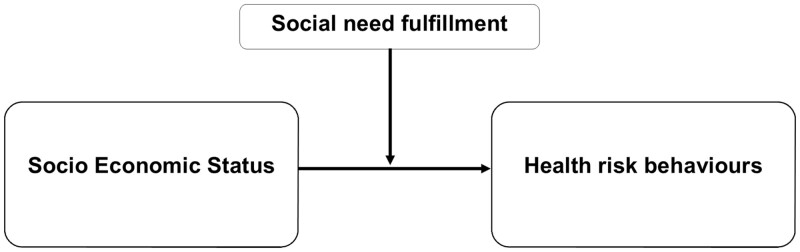

Another way of operationalization of social relationships is social need fulfillment as defined within the Social Production Function (SPF) theory [16, 17]. According to this theory, all humans are motivated to optimize their social needs (e.g. the need for social support and friendship), and therefore achieve psychosocial well-being [16, 17]. Social need fulfillment relates to the social aspect of the SPF theory. According to the SPF theory, individuals have three basic social needs and goals: affection, behavioural confirmation, and status. Affection refers to the need to be loved, liked, and accepted. Behavioural confirmation refers to the need of feeling that important others think that you are a good person or that you are doing the ‘right’ thing. Status refers to the need of feeling that you have an influence, are taken seriously, or are known for your skills and achievements. The fulfillment of these three social needs leads to social well-being [16, 17]. We will use the SPF theory, as measured with the validated Social Production Function Instrument for the Level of Well-being (SPF-IL) questionnaire, to investigate the following research question: does social need fulfillment moderate the association between SES and health risk behaviours (smoking and/or alcohol consumption) during pregnancy? By answering this question, we aim to understand the role of social need fulfillment in the association between SES and health behaviours during pregnancy (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Hypothesized moderation effect of social need fulfillment on socioeconomic status and health risk behaviours.

Methods

Design and study population

In this study, we used baseline data from the original Lifelines Cohort Study merged with data from the Lifelines Reproductive Origin of Adult Health and Disease (ROAHD) cohort, which is nested in the original Lifelines Cohort Study. Lifelines is a large representative population-based cohort study and a biobank in the northern provinces of the Netherlands with the aim to investigate risk factors for multifactorial diseases [18, 19]. Recruitment for the Lifelines Cohort Study was performed between 2006 and 2013 (N = 167 729). Inhabitants of the northern part of the Netherlands were invited to participate through their general practitioner. The Lifelines Cohort Study collects different types of data: biomaterial (e.g. urine, blood), physical examination (e.g. pulmonary function, blood pressure), and questionnaires. All participants gave informed consent before they underwent a physical examination. Participants completed multiple questionnaires about general characteristics (i.e. education, work), health (i.e. healthcare use, health status), lifestyle and environment (i.e. smoking, nutrition), and psychosocial parameters (i.e. social relations assessed with the SPF-IL questionnaire, stress) [18].

The aim of the Lifelines-ROAHD cohort is to investigate the health of women in their reproductive age (20–45 years). Data were collected in the period September 2017 until Mach 2018. From the original Lifelines Cohort, 30 712 women of reproductive age were eligible to participate in the Lifelines-ROAHD Cohort. In total, 5933 (19.3%) women completed the online questionnaire for the Lifelines-ROAHD study. After excluding women who did not complete essential parts of the questionnaire, in total, 5412 women participated in the Lifelines-ROAHD study, of which 2604 women had not been pregnant and 2808 women had experienced 6158 pregnancies and 5068 births [20]. The Lifelines-ROAHD questionnaire comprised items on women’s health: menstrual cycle characteristics, menopause, contraceptive use, fertility problems, and assisted reproduction treatments. If women had experienced a pregnancy, they also received items about conception, medication use during pregnancy, lifestyle (smoking during pregnancy, second-hand smoking, alcohol use, weight gain), course of pregnancy, and pregnancy outcomes. If women had given birth, they received additional questions about the onset of delivery, mode of birth, birth outcomes, health outcomes for mothers, and infant health problems [20].

The current study focuses on the population of women in the northern parts of the Netherlands (age ≥ 18 years). We included the women who had experienced at least one pregnancy independent of pregnancy outcome. From the Lifelines-ROAHD cohort, we selected women with data about health behaviours during pregnancy around two years prior to and after the Lifelines baseline assessment, including the social need fulfillment questionnaire (SPF-IL). If women were pregnant more than once in this time interval, we selected the pregnancy that occurred closest to the baseline assessment. Women were excluded from the analyses when they had missing data on education level or more than two missing values on the SPF-IL questionnaire.

Measurements

Demographics

Demographic characteristics that were collected included maternal age, marital status (single or in a relationship), migration background (Dutch or non-Dutch), and SES operationalized as the respondents highest attained education level. We chose education level as measure for SES because education is related to non-material resources such as knowledge and health literacy, which facilitate a healthy lifestyle [21]. In addition, there is an association between education level with smoking and alcohol consumption [1]. We categorized education level into a SES score according to the guideline of Statistics Netherlands, which is based on the International Standardized Classification of Education (ISCEI) [22]. We categorized a low SES as being lower educated (having finished primary education or lower- or preparatory secondary education), a middle SES as being middle educated (having finished middle or higher secondary education), and a high SES as being higher educated (having finished higher vocational education or university). Furthermore, we collected data about lifestyle characteristics, such as body mass index (BMI, kg/m2, overweight and obesity), and pregnancy characteristics, such as planned pregnancy (yes or no) and parity (nulliparous or multiparous).

Health risk behaviours during pregnancy

Health behaviours included in this study were smoking behaviour and/or alcohol consumption during pregnancy. In the ROAHD questionnaire, women were asked whether they had smoked or consumed alcohol during the pregnancy. They could either answer: (1) ‘yes, during part of the pregnancy’, (2) ‘yes, during the entire pregnancy’, or (2) ‘no’. The two variables (smoking and alcohol consumption) were combined into one variable. If women had either smoked or consumed alcohol during a part or their entire pregnancy, they were categorized as ‘yes’. If women never smoked or consumed alcohol during pregnancy, they were categorized as ‘no’.

Social need fulfillment

Social need fulfillment was assessed using the validated nine-item SPF-IL scale [17, 23]. The SPF-IL scale contains questions relating to the three social needs during the past three months: affection (three items), behavioural confirmation (three items), and status (three items). For example, respondents were asked: ‘do you feel that people really love you?’ (affection), ‘do others appreciate the things you do?’ (behavioural confirmation), and ‘do people find you an influential person?’ (status). The items were scored on a 4-point Likert scale ranging from 0 (never) to 3 (always,) resulting in a summed scale score with a maximum of 27. A higher score indicates higher social need fulfillment.

Other control variables

We pre-identified possible confounders. We identified maternal age (continuous) as possible confounder from the demographic characteristics [24]. From pregnancy characteristics, we included partners in consecutive pregnancies (dichotomized as same partner compared to multiple partners), parity [24], and planned pregnancy (dichotomous) [25] as possible confounders. With respect to parameters of lifestyle, we included BMI (continuous) [24], second-hand smoke exposure (dichotomous), physical illness (dichotomous), and psychological illness (dichotomous) as confounders. We decided to take second-hand smoke exposure into account because it is associated with smoking during pregnancy [26]. Because the presence of physical or psychological disease may influence health behaviours [27, 28], we also controlled for the presence of physical or psychological diseases prior to pregnancy, as measured in the Lifelines baseline assessment. Having a chronic physical disease may positively influence health behaviours (i.e. not smoking or drinking), while psychological diseases may negatively influence health behaviours [27, 28]. The most common physical diseases with a high burden among women in the reproductive age are hypertension and migraine [29, 30]. If women had one or both chronic diseases, they were categorized as having at least one physical disease (dichotomous). Common psychological diseases are depression, social phobia, agoraphobia, panic disorder, (other) anxiety disorder, and manic-depressive disorder [31]. If women had one or more of these psychological diseases, they were categorized as having at least one psychological disease (dichotomous).

Statistical analysis

To report baseline characteristics, we used descriptive statistics. To assess differences between subgroups who differed on SES, we used Chi-Square tests and Fisher-Freeman-Halton exact test, where appropriate. Differences between the SES-groups on the SPF-IL score were tested with Kruskal–Wallis test, since the data were not normally distributed.

Univariable and multivariable logistic regression was used to assess the hypothesized effect modification of social need fulfillment (as measured with the total score of the SPF-IL) on the association between SES and health risk behaviours during pregnancy. First, we performed a univariable logistic analysis with SES as independent variable and health risk behaviours as dependent variable. Middle SES was taken as the reference category. We also performed a univariable logistic analysis for the SPF-IL score on health risk behaviours. Second, we performed multivariable logistic regression analyses where we assessed the association between SES and the total SPF-IL score on health risk behaviours (model 1). Subsequently, we added the confounders and the interaction terms of SES and the total SPF-IL score (model 2). For the selection of confounders, we performed a multivariable analysis for each potential confounder in the full model on health risk behaviours separately. If the relative change of associations of the primary exposure was greater than 10% after adding the possible confounder to the model, we concluded that there was confounding [32]. To be able to interpret the interaction effects, we reported the betas with the P values and calculated the odds ratios (ORs) for the interaction terms by putting the median SPF-IL score and the median plus one standard deviation score in the model. For each model, we calculated ORs with corresponding 95% confidence intervals (95% CI). All data were analysed in SPSS version 26.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). A P values ≤ 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Participants

From the 2808 women of the Lifelines-ROAHD cohort who experienced at least one pregnancy, in total, 1701 women were excluded because: they did not experience a pregnancy two years before or after completing the baseline questionnaire (n = 1694), had more than two missing values on the SPF-IL (n = 3), or because they had missing values on education level (n = 4). Our final study population consisted of 1107 women with a mean age (SD) of 31.7 (3.8) years. A minority of 5.0% had a low SES, 36.3% a middle SES, and 58.7% a high SES (Table 1). The SES-subgroups showed statistically significant differences on maternal age, number of partners in consecutive pregnancies, parity, BMI, smoking behaviour, second-hand smoke exposure, and presence of physical disease and psychological disease. Compared to women with a middle and high SES, women with a low SES were more often multiparous, obese, and smoked more often during pregnancy. Women with a low SES had a higher prevalence of health risk behaviours (smoking and/or alcohol consumption) during pregnancy compared with women with a middle or high SES. Women with a low SES had statistically significantly lower scores on the SPF-IL (P ≤ 0.001), compared with women with a middle or high SES; median scores (interquartile range) were 24.0 (21.0–25.0), 25.0 (23.0–27.0), and 25.0 (24.0–27.0) respectively, indicating they had a lower social need fulfillment.

Table 1.

Population characteristics of women in the Lifelines Cohort Study and Lifelines-ROAHD by socioeconomic status

| Total population | Low SES | Middle SES | High SES | Statistical differences between SES groups | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N = 1107 | n = 55 (5.0%) | n = 402 (36.3%) | n = 650 (58.7%) | ||

| N (%)a | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | P value | |

| Maternal characteristics | |||||

| Maternal age (in years) during pregnancy | 0.05 | ||||

| 18–30 | 333 (30.1) | 24 (43.6) | 136 (33.8) | 173 (26.6) | |

| 31–35 | 518 (46.8) | 19 (34.5) | 184 (45.8) | 315 (48.5) | |

| ≥36 | 256 (23.1) | 12 (21.8) | 82 (20.4) | 162 (24.9) | |

| Migration background | 0.26 | ||||

| Dutch | 1058 (95.6) | 55 (100) | 382 (95.0) | 621 (95.5) | |

| Non-Dutch | 49 (4.4) | – | 20 (5.0) | 29 (4.5) | |

| Marital status | 0.60 | ||||

| Single | 37 (3.3) | ≤10 (≤0.2) | ≤10 (≤0.02) | 20 (3.1) | |

| In a relationship | 741 (66.9) | 38 (69.1) | 274 (68.2) | 429 (66.0) | |

| Missing | 329 (29.7) | 14 (25.5) | 114 (28.4) | 201 (30.9) | |

| Pregnancy characteristics | |||||

| Partners consecutive pregnancies | 0.03 | ||||

| Same partner | 881 (79.6) | 45 (81.8) | 308 (76.6) | 528 (81.2) | |

| Two or more partners | 70 (6.3) | ≤10 (≤0.2) | 35 (8.7) | 31 (4.8) | |

| Missing | 156 (14.1) | ≤10 (≤0.2) | 59 (14.7) | 91 (14.0) | |

| Parity | ≤0.001 | ||||

| Nulliparous | 497 (44.9) | 14 (25.5) | 167 (41.5) | 316 (48.6) | |

| Multiparous | 610 (55.1) | 41 (74.5) | 235 (58.5) | 334 (51.4) | |

| Planned pregnancy | 0.08 | ||||

| Yes | 960 (86.7) | 43 (78.2) | 344 (85.6) | 573 (88.2) | |

| No | 147 (13.3) | 12 (21.8) | 58 (14.4) | 77 (11.8) | |

| Lifestyle characteristics | |||||

| BMIb | ≤0.001 | ||||

| Overweight | 285 (25.7) | 17 (30.9) | 123 (30.6) | 145 (22.3) | |

| Obesity | 136 (12.3) | 13 (23.6) | 67 (16.7) | 56 (8.6) | |

| Smoking behaviour | ≤0.001 | ||||

| No | 1026 (92.7) | 43 (78.2) | 357 (88.8) | 626 (96.3) | |

| Yes | 81 (7.3) | 12 (21.8) | 45 (11.2) | 24 (3.7) | |

| Second-hand smoke exposurec | ≤0.001 | ||||

| Yes | 50 (4.5) | ≤10 (≤0.2) | 31 (7.7) | 15 (2.3) | |

| Alcohol consumption | 0.59 | ||||

| Yes | 66 (6.0) | ≤10 (≤0.2) | 20 (5.0) | 43 (6.6) | |

| Health risk behavioursd | ≤0.001 | ||||

| No | 984 (88.9) | 43 (78.2) | 346 (86.1) | 595 (91.5) | |

| Yes | 123 (11.1) | 12 (21.8) | 56 (13.9) | 55 (8.5) | |

| Presence of physical disease | |||||

| No | 787 (71.1) | 39 (70.9) | 265 (65.9) | 483 (74.3) | 0.01 |

| Yes | 320 (28.9) | 16 (29.1) | 137 (34.1) | 167 (25.7) | |

| Presence of psychological disease | |||||

| No | 947 (85.5) | 43 (78.2) | 328 (81.6) | 576 (88.6) | 0.01 |

| Yes | 160 (14.5) | 12 (21.8) | 74 (18.4) | 74 (11.4) |

Percentages may not add up to 100% due to rounding.

BMI classified as: overweight (25.0–29.9), obesity (>30).

As response to the question: Are there other household members smoking inside the house during pregnancy?

Composite outcome of smoking behaviour and/or alcohol consumption during pregnancy. The numbers of smoking behaviour and alcohol consumption do not add up to the composite outcome since some participants both smoke and consume alcohol.

Moderation effect

The univariable logistic analysis showed that women with a high SES had statistically significantly lower odds of health risk behaviours during pregnancy (OR 0.57, 95% CI 0.39–0.85) (Table 2). Social need fulfillment was not statistically significantly associated with health risk behaviours (OR 0.96, 95% CI 0.91–1.02).

Table 2.

Univariable and multivariable logistic regression models on health risks behaviours during pregnancy

| Univariable logistic regression | Multivariable logistic regression |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Health risk behaviour | Health risk behaviour | Health risk behaviour | |

| OR (95% CI) | Model 1 OR (95% CI) | Model 2 aOR (95% CI)a | |

| Socioeconomic status | |||

| Middle | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. |

| Low | 1.72 (0.86–3.47) | 1.67 (0.83–3.38) | 0.01 (0.00–9.32) |

| High | 0.57 (0.39–0.85) b | 0.58 (0.39–0.86) | 0.35 (0.01–11.70) |

| SPF-IL scorec | 0.96 (0.91–1.02) | 0.98 (0.92–1.04) | 0.95 (0.86–1.05) |

Adjusted for the dichotomous variables second-hand smoke exposure, partners in consecutive pregnancies and planned pregnancy.

Numbers in bold indicate statistically significant results (P ≤ 0.05).

The total SPF-IL score.

In the multivariable logistic regression analysis, including SES and the total social need fulfillment score (model 1), there was a significant association between high SES and health risk behaviours during pregnancy (OR 0.58, 95% CI 0.39–0.86). After adding the confounders and interaction terms (model 2), there were no statistically significant associations between SES, the SPF-IL score, and health risks behaviours. The interaction effect between SES and social need fulfillment on health risk behaviours was not statistically significant, indicating that no moderation effect is present (Table 2). The betas for the interaction effects for low SES and the SPF-IL score and high SES and the SPF-IL score were 0.207 (p = 0.33) and 0.029 (p = 0.66), respectively. For the low SES group, the odds for health risk behaviours during pregnancy were 1.66 times higher if the SPF-IL score increased with one standard deviation, in comparison with the middle SES group. For the high SES group, the odds for health risk behaviours during pregnancy were 0.93 times lower if the SPF-IL score increased with one standard deviation, in comparison with the middle SES group.

Discussion

Main findings

In this study, we investigated if social need fulfillment moderates the relationship between SES and health risk behaviours (smoking and/or consuming alcohol) during pregnancy. In our study population, women with a low, middle, and high SES showed statistically significant differences on maternal age, number of partners in consecutive pregnancies, parity, BMI, smoking behaviour, second-hand smoke exposure, health risk behaviours, presence of physical disease, and presence of psychological disease. Women with a low SES had a statistically significant lower social need fulfillment score than women with a middle or high SES. Women with a high SES had lower odds of smoking and/or consuming alcohol during pregnancy compared with women with a middle SES. However, this association did not remain after adjustment for confounders. The interaction effects between SES and social need fulfillment on health risk behaviours were not statistically significant, indicating that no moderation effect is present.

Strengths and limitations

A strength of this study is the richness of the available data about women’s pregnancies, such as BMI of women, data about second-hand smoke exposure, and partners in consecutive pregnancies. The prevalence of smoking in this cohort is comparable to the prevalence in the Dutch population, and the observed prevalence of alcohol consumption is higher than reported in a previous study [1]. However, smoking and alcohol consumption might still be underreported, since these were self-reported measures. Furthermore, the data were retrospectively collected, which might have caused a recall bias. Another limitation is the relatively high proportion of women with a high SES in the data compared to the general Dutch population [33]. In our study, 59% of the women had a high SES, whereas in the Dutch population, this is 40% [33]. The overrepresentation of women with a high SES and the relative low number of women with a low SES influences the generalizability of the results. Lastly, we combined smoking and/or alcohol consumption because of power issues. The relative low number of women with a low SES (n = 55) could explain why we did not find significant results for this group.

Interpretation

Our results show that women with a low SES have a lower social need fulfillment score, indicating that they feel less affection, behavioural confirmation, and status compared with women with a middle or high SES [17, 23]. This is in accordance with a previous study which reports that women with a low SES have fewer resources, which influences their health behaviours [7]. Although women with a low SES tend to have a less healthy lifestyle [5], we did not find a statistically significant association between a low SES and health risk behaviours during pregnancy. However, the high SES group did have statistically significant lower odds of health risk behaviours during pregnancy compared with the middle SES group. It could be that the association between SES and health behaviours differs across groups [34]. Other factors than SES influence health behaviours during pregnancy and could be a reason for differences in associations between SES groups [34]. For example, years of smoking, confidence, self-efficacy, and health concerns are associated with health risk behaviours [35]. Furthermore, the statistically significant association between high SES and health risk behaviours disappeared after adjusting for second-hand smoke exposure, partners in consecutive pregnancies, and planned pregnancy. This means that these variables likely explain part of the association between SES and health risk behaviours.

Contrary to the results of previous studies, we did not find a statistically significant association between social need fulfillment and health risks behaviours during pregnancy [12, 36]. This could be related to the influence of pregnancy on women’s lifestyle. Women are more likely to change their lifestyle during pregnancy because they are responsible for the health of the unborn child [37]. Despite the importance of social relations [8], pregnancy itself could be a main factor for women to change their health behaviours [37]. Another potential reason could be the differences in measures for social relations that were used. Previous studies used the quality of the intimate relationship or the perceived availability of interpersonal resources as measures for social relations [11, 14]. Especially support from a partner seems to be an important factor, which is associated with smoking cessation and a reduced likelihood of binge drinking during pregnancy [26, 38].

The measure used for social relations might also explain why we did not find a moderation effect, indicating that social need fulfillment does not influence the association between SES and health risk behaviours during pregnancy. We hypothesized that social need fulfillment could act as a buffer for stress and therefor positively influence health risk behaviours [10–12]. However, the type of social support that functions as a buffer for stress might depend on the source and type of stress [12]. In literature, there is no conclusive evidence about how social relations influence health behaviours [12, 14]. While some studies argue for a moderation effect, another study found evidence for a mediating effect with stress and social relations as mediators [11, 12, 14]. Future studies should particularly focus on the measure of social relations that influences health behaviours during pregnancy. Insight into the influence of social relations on health behaviours during pregnancy has important implications for interventions. Interventions aiming to improve social support are effective by improving social well-being and might be beneficial for health risk behaviours of pregnant women [39]. Furthermore, interventions that focused on peer support seem to be promising for addressing substance use during pregnancy [40].

Conclusion

In this study, we aimed to investigate if social need fulfillment moderates the relationship between SES and health risk behaviours during pregnancy. The results indicate that social need fulfillment does not modify the effect of SES on health risk behaviours during pregnancy. However, in existing literature, social relations are identified as an important influence on health risk behaviour. More research is needed to understand the pathways and to identify which measure of social relations is the most relevant regarding the association with health risk behaviours.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank all women who participated in the Lifelines-ROAHD cohort.

Contributor Information

Stella Weiland, Department of Primary and Long-term Care, University of Groningen, University Medical Center Groningen, Groningen, The Netherlands; Midwifery Academy Amsterdam Groningen, InHolland, Groningen, The Netherlands; Amsterdam UMC Location Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam, Midwifery Science, Amsterdam, The Netherlands.

Danielle E M C Jansen, Department of Primary and Long-term Care, University of Groningen, University Medical Center Groningen, Groningen, The Netherlands; Department of Sociology and Interuniversity Center for Social Science Theory and Methodology (ICS), University of Groningen, Groningen, The Netherlands.

Henk Groen, Department of Epidemiology, University of Groningen, University Medical Center Groningen, Groningen, The Netherlands.

Dorien R de Jong, Department of Primary and Long-term Care, University of Groningen, University Medical Center Groningen, Groningen, The Netherlands; Midwifery Academy Amsterdam Groningen, InHolland, Groningen, The Netherlands; Amsterdam UMC Location Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam, Midwifery Science, Amsterdam, The Netherlands.

Jan Jaap H M Erwich, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, University of Groningen, University Medical Center Groningen, Groningen, The Netherlands.

Marjolein Y Berger, Department of Primary and Long-term Care, University of Groningen, University Medical Center Groningen, Groningen, The Netherlands.

Annemieke Hoek, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, University of Groningen, University Medical Center Groningen, Groningen, The Netherlands.

Lilian L Peters, Department of Primary and Long-term Care, University of Groningen, University Medical Center Groningen, Groningen, The Netherlands; Midwifery Academy Amsterdam Groningen, InHolland, Groningen, The Netherlands; Amsterdam UMC Location Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam, Midwifery Science, Amsterdam, The Netherlands.

Author contributions

S.W.: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Writing—original draft. D.E.M.C.J.: Conceptualization, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Supervision, Writing—review and editing. H.G.: Conceptualization, Methodology, Project administration, Supervision, Writing—review and editing. D.R.d.J.: Conceptualization, Methodology, Project administration, Supervision, Writing—review and editing. J.J.H.M.E.: Conceptualization, Methodology, Project administration, Supervision, Writing—review and editing. M.Y.B.: Conceptualization, Methodology, Project administration, Supervision, Writing—review and editing. A.H.: Conceptualization, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Supervision, Writing—review and editing. L.L.P.: Conceptualization, Data curation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Supervision, Writing—review and editing.

Conflict of interest

A.H. reports consultancy for development and implementation of a lifestyle app MyFertiCoach developed by Ferring Pharmaceutical Company. The other authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Funding

This work was supported by the Dutch institute ZonMw (number 531 003018) and is part of the broader project ‘Together we’ll quit smoking! Optimizing the implementation of the Trimbos guideline “smoking cessation counseling” in daily practice of healthcare professionals supporting low SES pregnant women in the North or the Netherlands’.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the Lifelines Cohort Study, but restrictions apply to the availability of these data, which were used under license for the current study, and so are not publicly available. Data are, however, available from the authors upon reasonable request and with permission of the Lifelines Cohort Study.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

An informed consent was signed by all Lifelines participants before data collection. The Lifelines Cohort Study is conducted according to the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki and in accordance with research code University Medical Center Groningen. The Lifelines study was approved by the ethics committee of the University Medical Center Groningen (UMCG METc 2007/152). Informed consent was obtained from all individuals included in the study.

Consent for publication

Not applicable (there are no images or other personal or clinical details of participants that compromise anonymity).

Key points.

Women with a high SES had statistically significant lower odds of health risk behaviours during pregnancy.

There is no moderation effect present for social need fulfillment on the association between SES and health risk behaviours during pregnancy.

More research is needed to identify which measure of social relations is the most relevant regarding the association with health risk behaviours.

References

- 1. Scheffers-van Schayck T, Thissen V, Errami F, Tuithof M. Monitor Middelengebruik en Zwangerschap 2021. Utrecht: Trimbos-instituut, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Crone MR, Luurssen-Masurel N, Bruinsma-van Zwicht BS et al. Pregnant women at increased risk of adverse perinatal outcomes: a combination of less healthy behaviors and adverse psychosocial and socio-economic circumstances. Prev Med 2019;127:105817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Sundermann AC, Zhao S, Young CL et al. Alcohol use in pregnancy and miscarriage: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 2019;43:1606–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Abraham M, Alramadhan S, Iniguez C et al. A systematic review of maternal smoking during pregnancy and fetal measurements with meta-analysis. PLoS One 2017;12:e0170946. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Crozier SR, Robinson SM, Borland SE, SWS Study Group et al. Do women change their health behaviours in pregnancy? Findings from the Southampton Women’s Survey. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol 2009;23:446–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Weaver K, Campbell R, Mermelstein R et al. Pregnancy smoking in context: the influence of multiple levels of stress. Nicotine Tob Res 2008;10:1065–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Gallo LC, de Los Monteros KE, Shivpuri S. Socioeconomic status and health: what is the role of reserve capacity? Curr Dir Psychol Sci 2009;18:269–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Businelle MS, Kendzor DE, Reitzel LR et al. Pathways linking socioeconomic status and postpartum smoking relapse. Ann Behav Med 2013;45:180–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Popova S, Dozet D, Akhand Laboni S et al. Why do women consume alcohol during pregnancy or while breastfeeding? Drug Alcohol Rev 2022;41:759–77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Umberson D, Crosnoe R, Reczek C. Social relationships and health behavior across life course. Annu Rev Sociol 2010;36:139–57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Cohen S, Wills TA. Stress, social support, and the buffering hypothesis. Psychol Bull 1985;98:310–57. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Thoits PA. Mechanisms linking social ties and support to physical and mental health. J Health Soc Behav 2011;52:145–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Derksen ME, Kunst AE, Murugesu L et al. Smoking cessation among disadvantaged young women during and after pregnancy: exploring the role of social networks. Midwifery 2021;98:102985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Yang I, Hall LA, Ashford K et al. Pathways from socioeconomic status to prenatal smoking: a test of the reserve capacity model. Nurs Res 2017;66:2–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Fogelman N, Hwang S, Sinha R et al. Social support effects on neural stress and alcohol reward responses. Curr Top Behav Neurosci 2022;54:461–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Steverink N, Lindenberg S. Which social needs are important for subjective well-being? What happens to them with aging? Psychol Aging 2006;21:281–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Steverink N, Lindenberg S, Spiegel T et al. The associations of different social needs with psychological strengths and subjective well-being: an empirical investigation based on Social Production Function theory. J Happiness Stud 2020;21:799–824. [Google Scholar]

- 18. Scholtens S, Smidt N, Swertz MA et al. Cohort profile: LifeLines, a three-generation cohort study and biobank. Int J Epidemiol 2015;44:1172–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Stolk RP, Rosmalen JGM, Postma DS et al. Universal risk factors for multifactorial diseases: LifeLines: a three-generation population-based study. Eur J Epidemiol 2008;23:67–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Peters LL, Groen H, Sijtsma A et al. Women of reproductive age living in the North of the Netherlands: Lifelines Reproductive Origins of Adult Health and Disease (Lifelines-ROAHD) cohort. BMJ Open 2023;13:e063890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Lahelma E, Martikainen P, Laaksonen M et al. Pathways between socioeconomic determinants of health. J Epidemiol Community Health 2004;58:327–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Statistiek. Standaard onderwijsindeling 2016. Den Haag/Heerlen: Centraal Bureau voor de. 2019.

- 23. Nieboer AP, Lindenberg S, Boomsma A et al. Dimensions of well-being and their measurement: the SPF-IL Scale. Soc Indic Res 2005;73:313–53. [Google Scholar]

- 24. Tsakiridis I, Mamopoulos A, Papazisis G et al. Prevalence of smoking during pregnancy and associated risk factors: a cross-sectional study in Northern Greece. Eur J Public Health 2018;28:321–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Stephenson J, Heslehurst N, Hall J et al. Before the beginning: nutrition and lifestyle in the preconception period and its importance for future health. Lancet 2018;391:1830–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Scheffers-van Schayck T, Tuithof M, Otten R et al. Smoking behavior of women before, during, and after pregnancy: indicators of smoking, quitting, and relapse. Eur Addict Res 2019;25:132–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Ploughman M, Wallack EM, Chatterjee T, Health Lifestyle and Aging with MS Consortium et al. Under-treated depression negatively impacts lifestyle behaviors, participation and health-related quality of life among older people with multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler Relat Disord 2020;40:101919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Dambha-Miller H, Day AJ, Strelitz J et al. Behaviour change, weight loss and remission of type 2 diabetes: a community-based prospective cohort study. Diabet Med 2020;37:681–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Van der Linden M, Westert GB, Bakker Dd, Schellevis F. Tweede Nationale Studie naar ziekten en verrichtingen in de huisartspraktijk: klachten en aandoeningen in de bevolking en in de huisartspraktijk. Nivel. 2004.

- 30. Den Haag/Heerlen: Centraal Bureau voor de Statistiek. Vrouwen hebben vaker chronische aandoeningen dan mannen 2011. https://www.cbs.nl/nl-nl/achtergrond/2011/10/vrouwen-hebben-vaker-chronische-aandoeningen-dan-mannen (19 July 2022, date last accessed).

- 31. de Graaf MtHSvD R. De psychische gezondheid van de Nederlandse bevolking—NEMESIS 2: Opzet en eerste resultaten. Utrecht, 2010. Contract No.: ISBN 978-90-5253-663-7.

- 32. Hernán MA, Hernández-Díaz S, Werler MM et al. Causal knowledge as a prerequisite for confounding evaluation: an application to birth defects epidemiology. Am J Epidemiol 2002;192:1797–800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Planbureau SeC. De sociale staat van Nederland 2020. https://digitaal.scp.nl/ssn2020/onderwijs/#:∼:text=In%202010%20had%20ruim%2020,samen%20meer%20dan%2040%25 (19 July 2022, date last accessed).

- 34. Gazmararian JA, Adams MM, Pamuk ER. Associations between measures of socioeconomic status and maternal health behavior. Am J Prev Med 1996;12:108–15. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Crittenden KS, Manfredi C, Cho YI et al. Smoking cessation processes in low-SES women: the impact of time-varying pregnancy status, health care messages, stress, and health concerns. Addict Behav 2007;32:1347–66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Cohen S. Social relationships and health. Am Psychol 2004;59:676–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Olander EK, Smith DM, Darwin Z. Health behaviour and pregnancy: a time for change. J Reprod Infant Psychol 2018;36:1–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Dejong K, Olyaei A, Lo JO. Alcohol use in pregnancy. Clin Obstet Gynecol 2019;62:142–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Poudel-Tandukar K, Jacelon CS, Rai S et al. Social and emotional wellbeing (SEW) intervention for mental health promotion among resettled bhutanese adults in Massachusetts. Community Ment Health J 2021;57:1318–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Solomon LJ, Secker-Walker RH, Flynn BS et al. Proactive telephone peer support to help pregnant women stop smoking. Tob Control 2000;9 Suppl 3:Iii72–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the Lifelines Cohort Study, but restrictions apply to the availability of these data, which were used under license for the current study, and so are not publicly available. Data are, however, available from the authors upon reasonable request and with permission of the Lifelines Cohort Study.