Abstract

Fibronectin fragments have been shown to improve retrovirus gene transfer efficiency by binding retrovirus and target cells. Using a novel virus adhesion assay, we confirmed binding of type C oncoretrovirus vectors to the heparin II domain of fibronectin and demonstrated inhibition of viral binding and gene transfer by heparin.

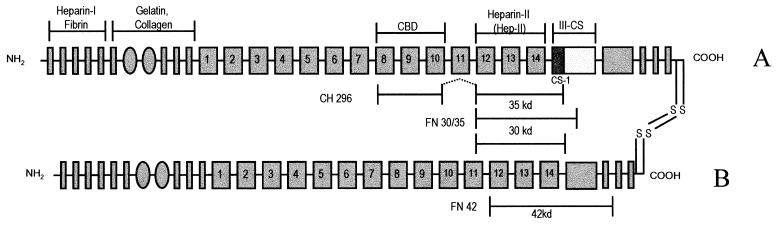

Fibronectin (FN) fragments have been shown to improve retrovirus gene transfer into primitive hematopoietic cells, including murine (9, 20) and primate (10) long-term repopulating stem cells or human cells repopulating immunodeficient NOD-SCID or BNX mice (7, 12). The technology has also been applied successfully to clinical studies (1, 5). The underlying biological mechanism has at least partly been resolved, as it was demonstrated that FN binds not only hematopoietic target cells (26, 27) but also recombinant retrovirus particles (9, 18). For this reason, colocalization of retrovirus and target cells on the FN fragments has been proposed as the mechanism responsible for improved retrovirus transduction of hematopoietic cells in the presence of FN (9, 18). The putative site for retrovirus binding is localized within type III repeats 12 to 14 of FN, containing the high-affinity heparin II (Hep-II) domain (Fig. 1) (11, 29). FN fragments combining the Hep-II domain with domains allowing integrin-mediated cell binding, such as the central cell binding domain or the type III repeat-connecting segment region (Fig. 1), are most active in enhancing retrovirus gene transfer efficiency (9).

FIG. 1.

Schematic diagram of the FN molecule. Depicted are the A and B chains of the plasma FN molecule, including binding sites for macromolecules and the locations of the chymotryptic fragments FN 30/35 and FN 42 (22, 23) as well as the recombinant fragment CH 296 (11) used in the experiments. CBD, cell binding domain, ligand for α5β1 integrins; CS-1, connecting segment 1, ligand for α4β1 integrins; III-CS, type III repeat-connecting segment, alternately spliced; heparin-II (Hep-II), C-terminal high-affinity heparin binding site. Symbols: narrow shaded bars, type I repeats (45 amino acids [aa]); shaded ovals, type II repeats (60 aa); wide shaded bars, type III repeats (90 aa).

Given the importance of the Hep-II -domain in this colocalization model, we were interested in investigating heparin as a potential inhibitor of retrovirus binding and, consequently, retrovirus transduction on FN fragments. Inhibitory effects of heparin and other sulfated polysaccharides on infection have been reported for other enveloped viruses, such as human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (6), cytomegalovirus (2), and Rous sarcoma virus (25). During lentivirus infection, heparin seems to interfere with intracellular events necessary for viral replication (6), whereas in the case of Rous sarcoma virus, negatively charged sulfated proteoglycans inhibit infection most likely through electrostatic inhibition of viral adsorption to the cell surface (25).

So far, most studies investigating the binding of retrovirus to FN have applied indirect methods using transduction efficiency for NIH 3T3 fibroblasts, which were added to FN-bound virus, as the readout (9, 18). More-direct evidence of retrovirus-binding to FN was provided by studies demonstrating binding of the retrovirus envelope protein gp70 using enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay technology (14). For the studies presented here, a radioactive virus binding assay, that allows direct and quantitative detection of virus bound to FN and is independent of downstream steps of infection was developed. This seems warranted, as viral infection is a multistep process and competitors of viral binding might also interfere with other downstream events in the viral infectious cycle.

Sucrose density centrifugation and purification of retrovirus vectors.

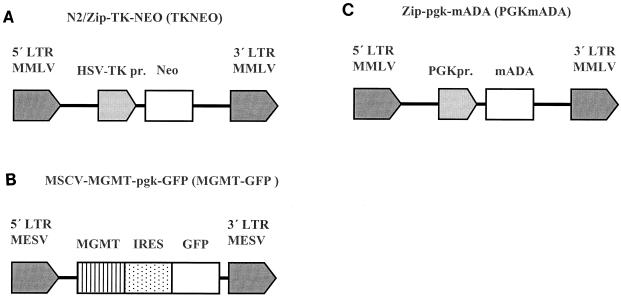

To generate radioactively labeled retrovirus for binding studies, purification of retrovirus is required. We addressed this requirement by applying a method previously described for the purification of vesicular stomatitis virus (17) that uses ultracentrifugation and a sucrose-step gradient to purify viral particles within the interphase of the gradient. First, localization of infectious retrovirus in the different fractions of the gradient after centrifugation was analyzed. These experiments were performed using two well-characterized, stable retrovirus producer clones: (i) a GP+envAM12 (15) amphotropic producer clone for the retrovirus vector N2/Zip-TKNEO (TKNEO; infectious titer of approximately 105/ml [19]) expressing the marker neomycin phosphotransferase (NEO) and (ii) a GP+E86 (16) ecotropic producer clone for the retrovirus vector MSCV-MGMTP140K-IRES-GFP (MGMT-GFP; infectious titer of approximately 106/ml [21]) expressing the marker green fluorescent protein (GFP), (Fig. 2A and B). Supernatant from the stable producer clones was filtered through a 0.45-μm-pore-size filter and loaded upon a sucrose gradient of 7 ml of 20% sucrose and 3 ml of 55% sucrose in 50 mM Tris, pH 7.4, with 150 mM NaCl and 0.5 mM EDTA. This gradient was centrifuged for 90 min at 25,000 rpm on a Beckman SW27 centrifuge at 4°C. After ultracentrifugation, 1-ml fractions starting from the bottom of the tube were quantitatively analyzed for the presence of infectious virus. Titration of infectious particles was performed by determining the number of cells expressing NEO (resistance to 0.75 mg/ml of G418 per ml; Gibco, Eggenstein, Germany) or, GFP (flow cytometric analysis; FacsCalibur with CellQuest software [Becton Dickinson]) following exposure of NIH 3T3 cells to serial dilutions of the different gradient fractions.

FIG. 2.

Schematic diagram of retrovirus-vectors. (A) The N2/Zip backbone of the TKNEO vector (19) and (C) the Zip backbone of the PGKmADA vector (4) are both based on the Moloney murine leukemia virus (MMLV). (B) The MSCV backbone of the MGMT-GFP vector is based on the murine embryonic sarcoma virus (MESV) (21, 28). In the TKNEO vector, the NEO reporter gene is transcribed from an internal herpes simplex virus thymidine kinase promoter (HSV-TKpr); in the PGKmADA vector, the murine adenosine deaminase (mADA) gene is transcribed from an internal human phosphoglycerate kinase promoter (PGKpr). In the MGMT-GFP vector, O6-methylguanine methyltransferase (MGMT) and the marker GFP are transcribed from the MESV promoter, 5′ and 3′ of an encephalomyocarditis virus internal ribosome entry site (IRES).

These initial experiments demonstrated that after centrifugation, most infectious retrovirus was present around the interphase within the third and fourth milliliters (Table 1), and viral titers recovered in these interphase fractions (2 × 103 to 5 × 103 infectious particles per ml for TKNEO and approximately 3 × 106 infectious particles per ml for MGMT-GFP) roughly equalled the viral titers present in the supernatant before centrifugation, with a maximal difference of 1 log. Above and below the interphase, titers dropped significantly, and in the supernatant above the gradient very little virus could be recovered. These data indicate the feasibility of recovering biologically active retrovirus after ultracentrifugation around the interphase of the gradient.

TABLE 1.

Recovery of retrovirus after ultracentrifugationa

| Fraction | MGMT-GFP titer (% GFP-positive cells per ml)b | TKNEO titer (G418r colonies per ml)

|

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Expt 1 | Expt 2 | ||

| 1st ml | 4 × 104 ± 6 × 104 | <102 | 102 |

| 2nd ml | 2 × 105 ± 5 × 105 | 3 × 102 | 2 × 102 |

| 3rd ml | 3 × 106 ± 3 × 106 | 4 × 103 | 5 × 103 |

| 4th ml | 3 × 106 ± 3 × 106 | 4 × 103 | 2 × 103 |

| 5th ml | 4 × 105 ± 3 × 105 | NDc | ND |

| 6th ml | 4 × 105 ± 3 × 105 | ND | ND |

| 7th ml | 7 × 104 ± 7 × 104 | ND | ND |

| Supernatant above gradient | 4 × 104 ± 5 × 104 | <10 | 10 |

| Supernatant before centrifugation | 8 × 105 ± 7 × 105 | 3 × 104 | 3 × 103 |

Infectious titer of different fractions recovered after ultracentrifugation of retrovirus on a two-step sucrose gradient. Interphase fractions 3 and 4 are in boldface.

Mean values ± standard deviations for four independent experiments.

ND, not done.

Radioactive labeling of retrovirus with [35S]methionine.

As in preliminary studies, [3H]uridine labeling of viral RNA was too inefficient to allow binding studies; subsequent experiments were performed utilizing 35S-protein labeling. For the initial experiments, two high-titer retrovirus producer clones were used: the ecotropic MGMT-GFP producer clone described above and a GP+envAM12 amphotropic producer clone for the retrovirus vector PGKmADA (Fig. 2C) (infectious titer of approximately 107/ml [4]). Cells were starved for 2 h in Dulbecco modified Eagle medium without methionine before 100 μCi of [35S]methionine per ml (specific activity, >1,000 Ci/mmol; Amersham, Braunschweig, Germany) was added. Following overnight culture, supernatant was filtered through a 0.45-μm-pore-size filter and sucrose gradient centrifugation was performed as described above. One-milliliter fractions were harvested from the bottom of the tube, diluted 1:20 with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), and incubated on 35-mm dishes (Falcon, Heidelberg, Germany) coated with 4 μg of FN 30/35 fragment per cm2 or bovine serum albumin (BSA) (Sigma, Deisenhofen, Germany), as described earlier (8, 18). After incubation for 30 min at 37°C, dishes were washed three times with PBS. Radioactive proteins remaining on the dishes thereafter (bound radioactivity) were recovered by extensive trypsin digestion (Trypsin-EDTA; Gibco) and measured in a scintillation counter (LS 6500; Beckman, Palo Alto, Calif.). To prove viral specificity of 35S-labeled proteins adhering to FN fragments, producer cell lines were compared with the parental, non-virus-producing cell line NIH 3T3. For these cell lines, all labeled proteins, except viral proteins, should be identical; therefore, radioactivity detected from supernatant of the producer cell lines only should indicate retrovirus origin.

As shown in Table 2, a 10- to 20-fold increase of bound radioactivity was noted in the virus-containing interphase fractions 3 and 4 for supernatant of virus producer cell lines but not of NIH 3T3 cells. Also, no bound radioactivity above background was recovered from the interphase fractions of PGKmADA supernatant after incubation on non-virus-binding BSA control plates. These lines of evidence suggested that bound radioactivity recovered from FN-coated plates corresponded to 35S-labeled retrovirus proteins.

TABLE 2.

Binding of radioactively labeled supernatant from retrovirus producer cells to FN fragments

| Fraction | Adherent radioactivity (cpm)a

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Expt 1

|

Expt 2

|

||||

| PGKmADA on FN 30/35 | PGKmADA on BSA | NIH 3T3 on FN 30/35 | MGMT-GFP on CH 296 | NIH 3T3 on CH 296 | |

| 1st ml | 58 | 55 | 105 | 48 | 25 |

| 2nd ml | 55 | 54 | 85 | 41 | 37 |

| 3rd ml | 633 | 58 | 135 | 180 | 31 |

| 4th ml | 933 | 62 | 210 | 1,190 | 64 |

| 5th ml | ND | ND | ND | 56 | 25 |

| 6th ml | ND | ND | ND | 96 | 21 |

Adherent radioactivity on FN or BSA after [35S]methionine labeling, ultracentrifugation, and incubation for different gradient fractions of two virus producer lines and the respective parental cell line NIH 3T3. Interphase fractions 3 and 4 are in boldface. ND, not done.

Adhesion of ecotropic and amphotropic retrovirus to FN fragments.

For these and further experiments, after 35S labeling and centrifugation, fractions 3 and 4 were pooled and diluted 1:20 in PBS and radioactively labeled viral supernatant was tested for adherence to dishes coated with FN fragments, as described above. Adhesion of retrovirus to FN fragments was investigated for amphotropic TKNEO and PGKmADA and ecotropic MGMT-GFP retroviruses. As demonstrated in Table 3, all three retroviruses showed significant binding to dishes coated with 4 μg of FN 30/35, FN 42, or CH 296 fragments per cm2 compared to BSA controls. As demonstrated for the TKNEO vector, binding was substantially reduced on dishes coated with 0.5 μg of FN fragments per cm2. Next, the correlation between retrovirus titer and binding to FN fragments was investigated. Various dilutions of [35S]methionine-labeled TKNEO supernatant were incubated on dishes coated with 4 μg of commercially available FN per cm2 (Boehringer Mannheim, Mannheim, Germany), comprising both chains of FN including the Hep-II domain. Increasing the concentration of retrovirus by lowering the dilution of the interphase fractions from 1:20 (397 cpm) via 1:10 (798 cpm) to 1:5 (1,051 cpm) led to a progressive increase in retrovirus binding in this experiment.

TABLE 3.

Adhesion of radioactively labeled retrovirus to FN fragments

| Fragment or control | Concn (μg/cm2) | Adherent radioactivity (cpm) (mean ± SD)a

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PGKmADA (n = 3) | TKNEO (n = 3) | MGMT-GFP (n = 6) | ||

| FN 30/35 | 4.0 | 3,810 ± 228∗ | 1,580 ± 574∗ | NDb |

| 0.5 | ND | 469 ± 454 | ND | |

| FN 42 | 4.0 | ND | 1,500 ± 712∗ | ND |

| 0.5 | ND | 833 ± 519∗ | ND | |

| CH 296 | 4.0 | ND | ND | 2,680 ± 332∗ |

| BSA | 546 ± 185 | 410 ± 176 | 843 ± 345 | |

Adherent viral radioactivity on FN or BSA after [35S]methionine labeling, ultracentrifugation, and incubation of interphase fractions for three viral cell lines. ∗, significantly different from control (BSA) values (P < 0.05 [two-tailed t test]).

ND, not done.

Heparin inhibits retrovirus binding to FN.

As FN binds heparin with high affinity within the Hep-II domain (3, 29) and the viral binding site is localized within this domain (9), we hypothesized that heparin might inhibit retrovirus binding to FN. To prove this hypothesis, unfractionated heparin isolated from porcine mucosa (Sigma) was added during incubation of labeled MGMT-GFP or TKNEO retrovirus on FN fragments. As shown in Table 4, bound radioactivity was significantly reduced in the presence of 5 to 500 μg of heparin per ml. This was observed with both viral vectors and for all FN fragments investigated, indicating that heparin at these concentrations substantially inhibits retrovirus binding to FN. For the MGMT-GFP vector, the inhibition of viral binding to CH 296 by heparin was highly significant (P = 0.0001 to 0.0004; two-tailed, paired t test) for all concentrations tested. For this vector, some reduction of bound radioactivity in the presence of heparin was also observed on BSA for heparin concentrations of 10 to 500 μg/ml (P = 0.02 to 0.05). This finding indicated a certain degree of nonspecific, heparin-sensitive binding of retrovirus to BSA-coated plastic dishes, especially for higher heparin concentrations. However, this effect accounted for only approximately 20 to 25% of the changes in viral binding detected on CH 296, indicating that most of the inhibition of retrovirus binding to FN was due to a specific effect of heparin. Inhibition of retrovirus binding by heparin was also demonstrated for a commercially available 40-kDa FN fragment spanning the Hep-II domain (Boehringer Mannheim) (data not shown).

TABLE 4.

Inhibition of retrovirus binding by heparin

| Retrovirus | Fragment or control | Adherent radioactivity (cpm) at indicated heparin concn (μg/ml)a

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 5 | 10 | 50 | 100 | 500 | ||

| MGMT-GFP | CH 296 | 2,680 ± 332∗ | 775 ± 385‡ | 701 ± 394‡ | 651 ± 294‡ | 665 ± 336‡ | 502 ± 280‡ |

| BSA | 843 ± 345 | 656 ± 440 | 566 ± 255† | 551 ± 283† | 558 ± 283† | 425 ± 241† | |

| TKNEO | FN 30/35 | 1,150 | 764 | 286 | |||

| FN 42 | 1,770 | 293 | 221 | ||||

| BSA | 350 | ||||||

| TKNEO | FN 30/35 | 2,640 | 278 | 360 | |||

| FN 42 | 3,840 | 182 | 661 | ||||

| BSA | 562 | ||||||

Adherent viral radioactivity on FN or BSA after [35S]methionine labeling, ultracentrifugation, and incubation of interphase fractions for three viral cell lines. Data for MGMT-GFP are means ± standard deviations for four experiments; other data are from single experiments. ∗, significantly different from control (BSA) values (P < 0.05 [two-tailed t test]); †, significantly different from values obtained in the absence of heparin (P < 0.05 [two-tailed t test]); ‡, significantly different from values obtained in the absence of heparin (P < 0.01 [two-tailed t test]).

Heparin inhibits enhanced retrovirus transduction of primary CD34+ cells on FN fragments.

We next investigated the effect of heparin on retrovirus transduction efficiency for primary human CD34+ hematopoietic cells in the presence of FN fragments. For these experiments, mobilized peripheral blood progenitor cells from patients were collected according to a protocol approved by the local ethics committee. CD34+ cells were selected twice on an MS+ separation column (Miltenyi, Bergisch-Gladbach, Germany) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Purity of CD34+ cells as assessed by flow cytometry was higher than 90%. Cells were prestimulated for 48 h with 100 ng of recombinant human stem cell factor (Amgen, Munich, Germany) per ml and 100 U of recombinant human interleukin-3 (Novartis, Nuremberg, Germany) per ml. Thereafter, cells were incubated for 24 h in TKNEO supernatant containing the same cytokines and various concentrations of unfractionated heparin on dishes coated with 4 μg of CH 296 per cm2 or BSA as a control substrate. Cells were harvested through vigorous washing with cold medium and centrifuged, and growth of hematopoietic progenitor cells was assessed using standard methylcellulose-based clonogenic assays (24). Half of the cells were grown with the addition of 1.5 mg of G418 per ml (dry powder, adjusted to pH 7.4; Gibco) to define the percentage of transduced clonogenic cells. Control colonies infected with GP+envAM12 supernatant (mock) consistently demonstrated <1% background colony growth after exposure to 1.5 mg of G418 per ml.

As expected, there was a clear increase in the percentage of G418-resistant clonogenic progenitor cells after infection on CH 296, in comparison to BSA, and this effect was completely lost when heparin (500 μg/ml, equivalent to 70 IU/ml) was added during the retrovirus transduction procedure. The percentages of resistant clonogenic progenitor cells (means ± standard errors of the means of four experiments) were 16.4% ± 6.8% and 2.4% ± 4.5% for cells transduced on FN 30/35 and BSA, respectively, in the absence of heparin and 4.5% ± 4.7% (P < 0.05 compared with the value obtained in the absence of heparin; two-tailed t test) and 3.0% ± 6.0% for cells transduced on FN 30/35 and BSA, respectively, in the presence of 500 μg of heparin per ml. Thus, heparin completely abolished enhanced transduction efficiency on CH 296. No effect of heparin on the transduction rate for clonogenic progenitor cells was noted on BSA-coated control dishes, arguing for a distinct inhibitory effect of heparin on FN-enhanced retrovirus gene transfer. Reduced transduction of CD34+ cells was not due to reduced binding of target cells to FN in the presence of heparin, as heparin at the concentration used in our studies slightly enhances binding of hematopoietic progenitor cells to FN (D. Carstanjen, unpublished observations).

Heparin production by producer cell lines.

As it has been demonstrated that retrovirus producer cell lines can secrete proteoglycans (13), we tested several amphotropic retrovirus producer cell lines based on the GP+envAM12 producer cell line for the presence of heparin. All cell lines tested negative at a threshold level for detection of 0.02 U of heparin per ml, equivalent to approximately 2.8 μg of heparin per ml. Nevertheless, a negative effect on transduction by low concentrations of heparin present within the supernatants of these cell lines cannot definitively be excluded, as we have shown that heparin concentrations as low as 2 μg/ml can inhibit the enhancing effect of FN on retrovirus transduction of hematopoietic cells (25a).

Conclusion.

In this report, we demonstrate a novel technology to study the interaction of retrovirus vectors with matrix molecules directly and thus independently of events downstream in the retrovirus infectious cycle. We introduce a method to generate 35S-labeled retrovirus and use the radioactively labeled virus to investigate the binding to FN fragments containing the C-terminal high-affinity heparin-binding domain Hep II. We demonstrate binding of virus to dishes coated with recombinant FN fragments expressed in Escherichia coli (11), chymotryptic fragments isolated from human plasma (22, 23), and commercially available plasma FN, all of these preparations containing the Hep-II domain. The data are in agreement with previously published observations that the main adhesive domain for retrovirus lies within the Hep-II domain of FN (9). Binding was dose dependent for coating concentrations of FN fragments, as well as for viral load in the supernatant.

According to the colocalization model of FN-enhanced retrovirus gene transfer, inhibition of retrovirus binding to FN should reduce viral presentation to target cells and thus gene transfer efficiency. Here, we introduce heparin as an inhibitor of retrovirus binding to FN and as a potent inhibitor of FN-enhanced retrovirus gene transfer. Binding of ecotropic or amphotropic retrovirus vectors was inhibited by heparin, as was FN-enhanced gene transfer into hematopoietic cells, thus further supporting the colocalization model of FN-enhanced retrovirus gene transfer.

As extracellular matrix-based gene transfer is an elegant method of improving ex vivo retrovirus gene transfer efficiency, the radioactive viral binding assay presented here might be useful for identifying novel enhancer molecules by screening other matrix proteins for viral binding. These studies might include retrovirus vectors pseudotyped with different surface proteins. In addition, the assay might prove helpful in defining the critical amino acid sequences required for viral adhesion to matrix molecules.

Acknowledgments

We thank H. Hansen, Institute of Laboratory Medicine, Charité Virchow University Hospital, Berlin, Germany, for the measurements of heparin in retrovirus supernatant; David A. Williams, Herman B Wells Center for Pediatric Research, Indianapolis, Ind., in whose laboratories some of the experiments were performed, for continuous support and helpful commentary; and Mervin C. Yoder, Herman B Wells Center for Pediatric Research, Indianapolis, Ind., for critical and helpful review of the manuscript.

T.M. was supported by DFG grant Forschergruppe “Tumorselektive Therapie und Therapieresistenz: Grunlagen und Klinik” and by BMBF grant “Forschungsverbund somatische Gentherapie.”

REFERENCES

- 1.Abonour R, Williams D A, Einhorn L, Hall K M, Chen J, Coffman J, Traycoff C M, Bank A, Kato I, Ward M, Williams S D, Hromas R, Robertson M J, Smith F O, Woo D, Mills B, Srour E F, Cornetta K. Efficient retrovirus-mediated transfer of the multidrug resistance 1 gene into autologous human long-term repopulating hematopoietic stem cells. Nat Med. 2000;6:652–658. doi: 10.1038/76225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Baba M, Snoeck R, Pauwels R, de Clercq E. Sulfated polysaccharides are potent and selective inhibitors of various enveloped viruses, including herpes simplex virus, cytomegalovirus, vesicular stomatitis virus, and human immunodeficiency virus. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1988;32:1742–1745. doi: 10.1128/aac.32.11.1742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Benecky M J, Kolvenbach C G, Amrani D L, Mosesson M W. Evidence that binding to the carboxyl-terminal heparin-binding domain (Hep II) dominates the interaction between plasma fibronectin and heparin. Biochemistry. 1988;27:7565–7571. doi: 10.1021/bi00419a058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bodine D M, Moritz T, Donahue R E, Luskey B D, Kessler S W, Martin D I, Orkin S H, Nienhuis A W, Williams D A. Long-term in vivo expression of a murine adenosine deaminase gene in rhesus monkey hematopoietic cells of multiple lineages after retroviral mediated gene transfer into CD34+ bone marrow cells. Blood. 1993;82:1975–1980. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cavazzana-Calvo M, Hacein-Bey S, de Saint Basile G, Gross F, Yvon E, Nusbaum P, Selz F, Hue C, Certain S, Casanova J L, Bousso P, Deist F L, Fischer A. Gene therapy of human severe combined immunodeficiency (SCID)-XI disease. Science. 2000;288:669–672. doi: 10.1126/science.288.5466.669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Coombe D R, Harrop H A, Watton J, Mulloy B, Barrowcliffe T W, Rider C C. Low anticoagulant heparin retains anti-HIV type 1 activity in vitro. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 1995;11:1393–1396. doi: 10.1089/aid.1995.11.1393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dao M A, Nolta J A. Use of the BNX/Hu xenograft model of human hematopoiesis to optimize methods for retroviral-mediated stem cell transduction. Int J Mol Med. 1998;1:257–264. doi: 10.3892/ijmm.1.1.257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hanenberg H, Hashino K, Konishi H, Hock R A, Kato I, Williams D A. Optimization of fibronectin-assisted retroviral gene transfer into human CD34+ hematopoietic cells. Hum Gene Ther. 1997;8:2193–2206. doi: 10.1089/hum.1997.8.18-2193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hanenberg H, Xiao X L, Dilloo D, Hashino K, Kato I, Williams D A. Colocalization of retrovirus and target cells on specific fibronectin fragments increases genetic transduction of mammalian cells. Nat Med. 1996;2:876–882. doi: 10.1038/nm0896-876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kiem H P, Andrews R G, Morris J, Peterson L, Heyward S, Allen J M, Rasko J E, Potter J, Miller A D. Improved gene transfer into baboon marrow repopulating cells using recombinant human fibronectin fragment CH-296 in combination with interleukin-6, stem cell factor, Flt-3 ligand, and megakaryocyte growth and development factor. Blood. 1998;92:1878–1886. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kimizuka F, Taguchi Y, Ohdate Y, Kawase Y, Shimojo T, Hashino K, Kato I, Sekiguchi K, Titani K. Production and characterization of functional domains of human fibronectin expressed in Escherichia coli. J Biochem (Tokyo) 1991;110:284–291. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jbchem.a123572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Larochelle A, Vormoor J, Hanenberg H, Wang J C, Bhatia M, Lapidot T, Moritz T, Murdoch B, Xiao X L, Kato I, Williams D A, Dick J E. Identification of primitive human hematopoietic cells capable of repopulating NOD/SCID mouse bone marrow: implications for gene therapy. Nat Med. 1996;2:1329–1337. doi: 10.1038/nm1296-1329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Le Doux J M, Morgan J R, Snow R G, Yarmush M L. Proteoglycans secreted by packaging cell lines inhibit retrovirus infection. J Virol. 1996;70:6468–6473. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.9.6468-6473.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.MacNeill E C, Hanenberg H, Pollok K E, van der Loo J C M, Bierhuizen M F A, Wagemaker G, Williams D A. Simultaneous infection with retroviruses pseudotyped with different envelope proteins bypasses viral receptor interference associated with colocalization of gp70 and target cells on fibronectin CH-296. J Virol. 1999;73:3960–3967. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.5.3960-3967.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Markowitz D, Goff D, Bank A. Construction and use of a safe and efficient amphotropic packaging cell line. Virology. 1988;167:400–406. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Markowitz D, Goff S, Bank A. A safe packaging line for gene transfer: separating viral genes on two different plasmids. J Virol. 1988;62:1120–1124. doi: 10.1128/jvi.62.4.1120-1124.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Matlin K, Bainton D F, Pesonen M, Louvard D, Genty N, Simons K. Transepithelial transport of a viral membrane glycoprotein implanted into apical plasma membrane of Madin-Darby canine kidney cells. Morphological evidence. J Cell Biol. 1983;97:627–637. doi: 10.1083/jcb.97.3.627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Moritz T, Dutt P, Xiao X, Carstanjen D, Vik T, Hanenberg H, Williams D A. Fibronectin improves transduction of reconstituting hematopoietic stem cells by retroviral vectors: evidence of direct viral binding to chymotryptic carboxy-terminal fragments. Blood. 1996;88:855–862. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Moritz T, Keller D C, Williams D A. Human cord blood cells as targets for gene transfer: potential use in genetic therapies of severe combined immunodeficiency disease. J Exp Med. 1993;178:529–536. doi: 10.1084/jem.178.2.529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Moritz T, Patel V P, Williams D A. Bone marrow extracellular matrix molecules improve gene transfer into human hematopoietic cells via retroviral vectors. J Clin Investig. 1994;93:1451–1457. doi: 10.1172/JCI117122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ragg S, Xu-Welliver M, Bailey J, D'Souza M, Cooper R, Chandra S, Seshadri R, Pegg A E, Williams D A. Direct reversal of DNA damage by mutant methyltransferase protein protects mice against dose-intensified chemotherapy and leads to in vivo selection of hematopoietic stem cells. Cancer Res. 2000;60:5187–5195. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ruoslahti E, Hayman E G, Engvall E, Cothran W C, Butler W T. Alignment of biologically active domains in the fibronectin molecule. J Biol Chem. 1981;256:7277–7281. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ruoslahti E, Hayman E G, Pierschbacher M, Engvall E. Fibronectin: purification, immunochemical properties, and biological activities. Methods Enzymol. 1982;82:803–831. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(82)82103-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Toksoz D, Zsebo K M, Smith K A, Hu S, Brankow D, Suggs S V, Martin F H, Williams D A. Support of human hematopoiesis in long-term bone marrow cultures by murine stromal cells selectively expressing the membrane-bound and secreted forms of the human homolog of the steel gene product, stem cell factor. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992;89:7350–7354. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.16.7350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Toyoshima K, Vogt P K. Enhancement and inhibition of avian sarcoma viruses by polycations and polyanions. Virology. 1969;38:414–426. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(69)90154-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25a.Trarbach T, Greifenberg S, Badenheuer W, Elmaagacli A, Flasshove M, Seeber S, Moritz T. Optimized retroviral transduction protocol for human progenitor cells utilizing fibronectin fragments. Cytotherapy. 2000;2:429–438. doi: 10.1080/146532400539378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Verfaillie C M, McCarthy J B, McGlave P B. Differentiation of primitive human multipotent hematopoietic progenitors into single lineage clonogenic progenitors is accompanied by alterations in their interaction with fibronectin. J Exp Med. 1991;174:693–703. doi: 10.1084/jem.174.3.693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Williams D A, Rios M, Stephens C, Patel V P. Fibronectin and VLA-4 in hematopoietic stem cell-microenvironment interactions. Nature. 1991;352:438–441. doi: 10.1038/352438a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wiznerowicz M, Fong A Z, Hawley R G, Mackiewicz A. Development of a double-copy bicistronic retroviral vector for human gene therapy. Adv Exp Med Biol. 1998;451:441–447. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4615-5357-1_68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yamada K M. Fibronectin domains and receptors. In: Mosher D F, editor. Fibronectin. San Diego, Calif: Academic Press; 1988. pp. 47–121. [Google Scholar]