Abstract

Supercritical , known for its non-toxic, non-flammable and abundant properties, is well-perceived as a green alternative to hazardous organic solvents. It has attracted considerable interest in food, pharmaceuticals, chromatography, and catalysis fields. When supercritical is integrated into microfluidic systems, it offers several advantages compared to conventional macro-scale supercritical reactors. These include optical transparency, small volume, rapid reaction, and precise manipulation of fluids, making microfluidics a versatile tool for process optimization and fundamental studies of extraction and reaction kinetics in supercritical applications. Moreover, the small length scale of microfluidics allows for the production of uniform nanoparticles with reduced particle size, beneficial for nanomaterial synthesis. In this perspective, we review microfluidic investigations involving supercritical , with a particular focus on three primary applications, namely, solvent extraction, nanoparticle synthesis, and chemical reactions. We provide a summary of the experimental innovations, key mechanisms, and principle findings from these microfluidic studies, aiming to spark further interest. Finally, we conclude this review with some discussion on the future perspectives in this field.

I. INTRODUCTION

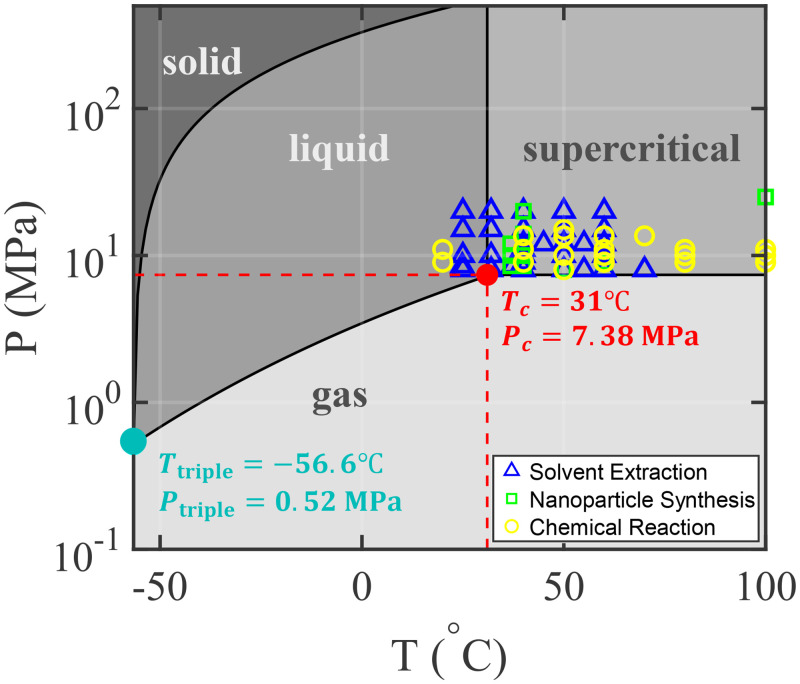

A supercritical (sc) fluid represents an intriguing phase achieved when a substance exceeds its critical pressure and temperature.1 These fluids, in the absence of surface tension for a supercritical phase, exhibit combined properties of high density (typically associated with a liquid state), low viscosity (similar to a gaseous state), and an intermediate diffusivity between the gas and liquid phases.2 Compared to a liquid solvent, the higher diffusivity and lower viscosity of supercritical fluids enhance mass transfer, beneficial for the applications of extraction and chromatography.2 Supercritical fluids also occur naturally under extreme pressure and temperature conditions, such as supercritical water near underwater volcanoes and supercritical carbon dioxide ( ) in the atmosphere of Venus.3 Among various supercritical fluids, supercritical stands out for industrial applications due to its relatively low critical pressure and temperature ( MPa, K),4 as opposed to other fluids like water ( MPa, K)4 and ethanol ( MPa, K).4 Figure 1 shows a thermodynamic phase diagram for at various pressures and temperatures.

FIG. 1.

A phase diagram for . is in the supercritical state when the pressure and temperature exceed the critical values, and , respectively. The symbols on this phase diagram highlight the conditions for the key experimental investigations mentioned in this review. Here, we focus on reviewing the studies with applications of supercritical in microfluidics, including solvent extraction, nanoparticle synthesis, and chemical reactions.

As a green solvent, supercritical is particularly appealing in pharmaceuticals and food science to replace organic solvents for non-toxicity.5,6 Its distinct mass transfer characteristics have led to a diverse range of applications, including supercritical fluid chromatography,2 fluid extraction,7–9 nano- and micro-particle formation,10 polymer impregnation and foaming,11,12 drying, cleaning, and chemical reactions.13 In established industrial applications, supercritical is utilized in extraction processes, such as decaffeination from coffee and tea,14 and essential oil extraction from botanic species. By adjusting system pressure and temperature, the fluid properties of supercritical —including density, viscosity, and diffusivity—can be conveniently tuned to improve its solvent power. However, since molecules are non-polar with a net-zero dipole moment due to their symmetrical and linear structure, it has poor solvent strength toward dissolving polar compounds.15 To overcome this limitation, polar co-solvents such as ethanol are often used to augment the solvent strength of supercritical . Due to strong molecular interactions, supercritical also exhibits exceptional solubility for fluorocarbon and carbonyl-based materials.3

While supercritical fluid extraction (SFE) is typically performed in pressure vessels made of metal, rapid screening and process optimization are difficult using these macro-scale units.16 Microfluidics, when integrated with advanced imaging techniques, enables visualization of fluidic phenomena at a small scale. Microfluidics focuses on studying and controlling fluids within the length scale of – m.17 In microfluidic channel flow, the typical Reynolds number ( , defined as the ratio of inertial to viscous forces, with fluid velocity , density , viscosity , and characteristic length scale ) ranges from 0.5 to 500,16 indicating predominantly laminar pipe flow due to miniaturization. In typical microfluidic channels, laminar flow results in slow diffusion-dominated fluid mixing, with minimal flow recirculation or turbulence.16,18 Consequently, to enhance fluid mixing, microfluidic designs often incorporate passive mixers (e.g., zigzag-shaped microchannels, geometric obstacles) or active mixers (e.g., pressure-driven flow with periodic perturbations).19 Recent experiments and numerical simulations have demonstrated that turbulent mixing can be achieved for supercritical fluids in microchannels under high pressure, making it advantageous for applications such as extraction, synthesis, and reaction.20,21 Another characteristic of microfluidics is the reduced mixing time ( ) due to the small length scale ( ), where is the typical flow width and is the diffusion coefficient.16 Moreover, for supercritical fluids in microfluidics, a narrower residence time distribution (RTD) exists due to the low viscosity of supercritical fluids and the reduced length scale of microfluidics.16 Residence time distribution (RTD) is a statistical distribution of the time that particles spend inside a system, generally influenced by velocity profile and molecular diffusion.22,23 A narrower RTD is advantageous for nanomaterial synthesis, allowing for control over the size distribution of the nanoparticles.16,24 For an in-depth discussion of supercritical microfluidics fundamentals and applications, Marre et al. provide an extensive review.16

To explore the diverse applications of supercritical in microfluidics, it is essential that the microfluidic chip can withstand a high fluid pressure exceeding 7.4 MPa. The thermodynamic condition of supercritical in the microchannel is usually achieved and maintained by controlling the pressure and temperature above the critical condition. A high-pressure syringe pump injects compressed into the microchannel, while a backpressure regulator downstream maintains the pressure above the critical condition.25–27 The temperature is kept above the critical point, either through electric heating28–30 or by immersing the microfluidic chip in a fluid bath.31,32 In addition to the challenges of maintaining the supercritical state in microfluidics, the fabrication of high-pressure microfluidics presents various challenges. Such microfluidic designs need to take into consideration factors including microchannel size, cross-sectional shape, spacing between individual channels, and packaging elements including interconnections and fittings, as well as thermal stress from heating.33

Commonly, these devices are made of silicon and glass, which can endure pressure and temperature up to 25 MPa and 450 °C while maintaining good optical transparency for experimental observations.33 Fabricating these “lab-on-a-chip” devices relies on photolithography, a technique originally developed for manufacturing integrated circuits in the 1950s. In this process, a desired pattern is transferred onto a thin layer of photoresist through UV exposure, followed by etching of the microchannels and subsequent bonding with a cover glass for enclosure.17,33 These fabricated microfluidic devices demonstrate resilience against elevated pressure and temperature while maintaining good optical transparency for visualizing fluid flow. In addition to silicon-glass microfluidic devices, recent developments in sapphire microreactors offer enhanced pressure and temperature resistance, with the microfluidic device capable of withstanding up to 50 MPa and 500 °C.34,35 This unlocks further potential for extraction, synthesis, chemical reactions, and other process engineering in “lab-on-a-chip” devices under more extreme conditions.

The optical transparency of microfluidics offers opportunities to obtain real-time information about the dissolution or reaction kinetics on the chip for supercritical applications. For example, it allows for the observation of dissolution or extraction through size variations of fluid droplets.28–30,36–38 The thermodynamic properties, including the phase diagram, of supercritical can be determined on a chip owing to the optical access provided by the microfluidics, making it a powerful tool for investigating various applications.39–41 Additionally, in a microfluidic device, local concentration changes can be visualized through color variation.42,43 In situ characterization, including fluorescent,44–46 ultraviolet-visible (UV-vis), and Raman spectroscopy,25,47,48 are useful tools for on-chip analysis of mass transfer and reactions. Integrating microfluidics with these in situ characterization techniques makes the investigation of supercritical applications more convenient.

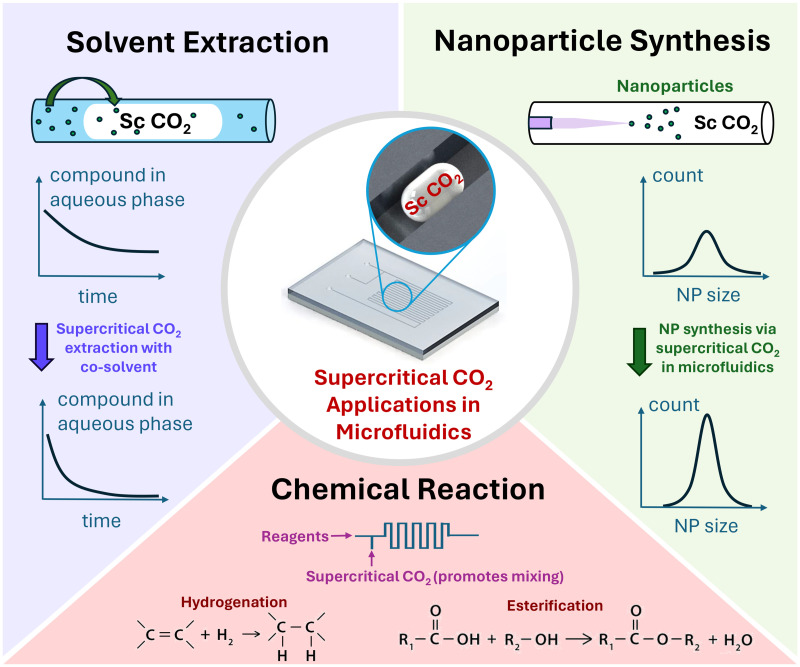

To date, many microfluidic investigations have been carried out for applications, including supercritical fluid extraction and nanoparticle synthesis with supercritical ,36,42,49–54 encapsulation of microparticles for drug delivery,55 screening flooding performance in the oil and gas industry,56–58 dissolution kinetics in an aqueous phase,25,28–30,38,44,59,60 and more. Compared with conventional methods, microfluidics allows precise manipulation of the fluid flow and enables superior control of parameters, such as the nanoparticle diameter and size distribution. In this perspective, we explore the current state-of-art in microfluidic studies for supercritical applications, including solvent extraction, nanoparticle synthesis, and chemical reaction using supercritical in microfluidics, as highlighted in Fig. 2. We aim to provide relevant background knowledge and highlight recent investigations concerning supercritical -related applications. We conclude by discussing the future perspectives and outlook of this field. For a comprehensive literature review on supercritical applications in microfluidics, readers can be directed to Kazan.61

FIG. 2.

Supercritical applications in microfluidics, including solvent extraction, nanoparticle synthesis, and chemical reaction.

II. SOLVENT EXTRACTION USING SUPERCRITICAL CO2 IN MICROFLUIDICS

A. Supercritical fluid extraction (SFE)

Solvent extraction is a separation process where a chemical compound is transferred from one phase to another immiscible phase (usually from water to an organic solvent), driven by the solubility difference of the extracted compound in the two phases.62 Traditional liquid–liquid extraction involves using organic solvents, such as hexane, toluene, or dichloromethane. However, the heavy usage of these organic solvents poses threats to human health and the environment. For instance, inhalation of hydrocarbons such as toluene can be harmful, and chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs) contribute to the depletion of the atmospheric ozone layer.63 Since the 1970s, when Zosel first patented supercritical extraction of caffeine,14 the supercritical fluid extraction (SFE) technique has been gaining considerable attention due to their potential to replace hazardous organic solvents. Supercritical effectively extracts valuable compounds from various raw materials, such as coffee beans, microalgae, hop, sesame, grape seeds, and many others.7 Furthermore, the compound separation upon depressurization eliminates an additional purification step, which is typically required in conventional solvent extraction techniques. Nowadays, supercritical extraction has already been employed in commercial processes for the decaffeination of tea and coffee. There is also a growing marketing demand for extracting high-value microalgae-derived products such as docosahexaenoic acid (DHA), eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA), astaxanthin, -carotene and Lutein, for applications in the food, medicine, and cosmetic industries.8,64 The moderate critical temperature of can avoid thermal degradation when extracting these bioactive compounds.

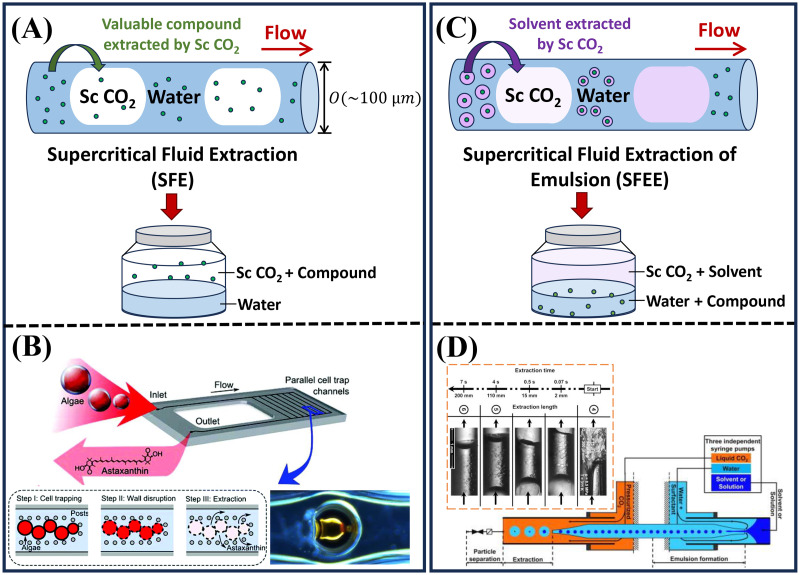

Table I provides an overview of recent microfluidic studies on supercritical extraction. Supercritical has been employed to extract a variety of compounds in microfluidics, with the extraction efficiency varying significantly across different species. The experimental conditions, including pressure, temperature, and co-solvent concentration, also play a crucial role in the extraction efficiency. For instance, supercritical has been used to extract vanillin and other aromatic lignin oxidation products from a continuous aqueous phase in a segmented flow.31,32 The process is schematically illustrated in Fig. 3(a), where extracts the valuable compounds that are initially dissolved in the continuous aqueous phase. As a result, the extraction efficiency was related to the polarity of the extracted compound. Among the five compounds, the less polar methyl dehydroabietate (MDHA) achieved nearly complete extraction, whereas the extraction of the more polar compound, vanillin, remained marginal regardless of pressure and temperature conditions.31,32 In addition, the extraction was improved under elevated pressure and reduced temperature conditions.31,32 In another study, various phenolic compounds have been extracted by supercritical in microfluidics, including ferulic acid (FA), gallic acid (GA), protocatechuic acid (PA), caffeic acid (CA), syringic acid (SA), and benzoic acid (BA).65,66 Among these compounds, BA exhibited the highest extraction efficiency, reaching up to , which increased with contact time, contact area, and density.65 Given the large variance in extraction efficiency among different compounds, this supercritical extraction approach allows for selective extraction and separation.31,32

TABLE I.

Literature summary of solvent extraction using supercritical in microfluidics.

| Microfluidic | Efficiency | Pressure | Temperature | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| design | Component extracted by | (%) | (MPa) | (°C) | Reference |

| Y-junction | Vanillin (V) | ≈0 | 8–12 | 40–60 | Assmann et al.32 |

| Methyl vanillate (MV) | 5–17 | ||||

| 5-Carbomethoxy-vanillin (5CV) | 17–50 | ||||

| Methyl 5-carbomethoxy-vanillate (M-5CV) | 27–66 | ||||

| Methyl dehydroabietate (MDHA) | 80–100 | ||||

| Parallel microchannelsa | Astaxanthin | 11.9–98.6b | 8 | 40–70 | Cheng et al.42 |

| Micromixer | Gallic acid (GA) | ≈0 | 8–20 | 25–60 | Houng et al.65 |

| Protocatechuic acid (PA) | ≈0 | ||||

| Caffeic acid (CA) | ≈0 | ||||

| Syringic acid (SA) | 0–4.6 | ||||

| Ferulic acid (FA) | 0–13.7 | ||||

| Benzoic acid (BA) | 4–75.3 | ||||

| Co-flow | Ethyl acetate (EA)c | / | 8.5 | 24.85–37.35 | Luther and Braeuer37 |

Microchannels were designed with trapping posts to trap algae cells for sc extraction.

20 vol. % of ethanol or olive oil as a co-solvent significantly improved the extraction efficiency to .

Supercritical extraction of emulsion (SFEE), acted as an anti-solvent in the process.

FIG. 3.

Supercritical extraction processes in microfluidics. (a) A schematic illustration of supercritical fluid extraction (SFE) in a microcapillary, where the valuable compound is extracted into the supercritical bubbles. The typical microchannel diameter is of the order of a few hundred m. (b) Supercritical extracts astaxanthin from hydrothermally disrupted algae cells using a silicon-glass microfluidic device.42,67 Reproduced with permission from Cheng et al., Green Chem. 19, 106–111 (2017). Copyright 2017 Royal Society of Chemistry. Reproduced with permission from Cheng et al., Bioresour. Technol. 250, 481-485 (2018). Copyright 2018 Elsevier. (c) A schematic illustration of supercritical fluid extraction of emulsion (SFEE) in a microcapillary, where the supercritical bubbles extract the solvent from the water/solvent/chemical compound mixture. (d) Supercritical extracts an organic solvent, ethyl acetate, from water plus solvent emulsions in a microcapillary.36 Reproduced with permission from Luther and Braeuer, J. Supercrit. Fluids 65, 78–86 (2012). Copyright 2012 Elsevier.

In addition to supercritical extraction in a segmented flow setting, researchers have also innovatively designed parallel structural traps in a silicon-glass microfluidic chip.42,67 These traps can effectively immobilize the algae cells for supercritical extraction, as seen in Fig. 3(b).42,67 The astaxanthin content was extracted by feeding a continuous stream of supercritical .42 Since astaxanthin is a lipid-soluble pigment, which naturally appears in red, the astaxanthin extraction efficiency was assessed by real-time monitoring of the color change in the cells.42 The results revealed a noticeable increase in the extraction efficiency from 12% to 63% when increasing the temperature from to 70 °C.42 Moreover, by adding ethanol or olive oil as co-solvents, the extraction efficiency improved considerably from 22% (for pure extraction) to as high as 98% at T=55 °C, meanwhile significantly reducing the extraction time to within minutes.42 Astaxanthin has a much higher solubility in both ethanol and olive oil compared to supercritical , leading to more rapid extraction with the addition of co-solvents.42

B. Supercritical fluid extraction of emulsion (SFEE)

Directly extracting the chemical compounds using supercritical , discussed above, sometimes results in low extraction efficiency limited by the solubility. Hence, supercritical fluid extraction of emulsion (SFEE) has been developed as an alternative approach, which utilizes as an anti-solvent. As illustrated in Fig. 3(c), in the SFEE process, the target compound is initially dissolved in an organic solvent and dispersed in water to create an oil-in-water emulsion. Following this, supercritical is introduced for solvent removal and the precipitation of nanoparticles in water. The agglomeration of nanoparticles can be avoided by adding surfactants into the system.68 The SFEE method offers several advantages, including the reduction of organic solvent usage and allowing for a high load capacity of the extracted compounds. Ethyl acetate (EA) is most widely used as an organic solvent in SFEE, making the SFEE process quite flexible since EA can dissolve a broad spectrum of hydrophobic compounds.68

Microfluidics can generate homogeneous emulsion with a well-defined droplet size by manipulating flow rate ratios,55,69,70 therefore being advantageous for investigating the SFEE process. Luther et al. studied the mass transfer in the SFEE process using fused silica capillaries with a co-flow geometry.36,37 Their experimental setup is shown in Fig. 3(d). In the first stage, an ethyl acetate (EA) in water emulsion was generated and stabilized with 1 wt. of modified starch.36,37 In the second stage, EA was extracted from the emulsion by supercritical .36,37 The process was visualized as supercritical penetrated the water phase, causing the EA droplets to swell. Supercritical penetration into the EA droplets led to a reduction in the refractive index of the droplets and made them invisible in water.36,37 Further downstream, the size of EA droplets reduced as they dissolved in supercritical .36 Although the authors presented a proof-of-concept study without any model compound dissolved in EA, the concept of utilizing supercritical as an anti-solvent to extract organic solvents is versatile and can be extended to various applications, particularly in nanoparticle synthesis, discussed in Sec. III.

In this section, we review recent microfluidic studies on supercritical extraction. The microfluidic platform serves as a versatile screening tool for flow visualization and process optimization. Studying extraction at a smaller length scale using microfluidics greatly accelerates the investigation process, making it a good platform for initial studies. Nonetheless, it may face obstacles when scaling up to industrial-scale production. In these studies, supercritical acts as either a solvent to extract valuable components or as an anti-solvent to remove unwanted organic solvents. The extraction efficiency is highly dependent on the polarity of the component32 and the addition of co-solvent (e.g., ethanol, olive oil).42 Extraction yield improves with increasing density, which corresponds to higher pressure or lower temperature conditions.31,65 However, the extraction efficiency for many species remains low, and further research is needed to identify which components can be extracted most effectively.

III. NANOPARTICLE SYNTHESIS USING SUPERCRITICAL CO2 IN MICROFLUIDICS

The utilization of nanoparticles in applications, including ceramic reinforcement and glass staining, dates back to ancient civilizations long preceding the scientific discovery starting from the 1980s.71,72 Today, organic and inorganic nanoparticles continue to play an important role in the field of electronics, catalysis, drug delivery, medical imaging, and so on. For example, carbon black serves as a common coloring and reinforcement additive in the production of rubber;73 transition-metal nanoparticles function as efficient heterogeneous catalysts;49,74 and lipid or polymeric nanoparticles are effective drug carriers for drug delivery.75 Nanoparticles exhibit unique size-dependent properties; their optical, electrical, or magnetic properties vary upon changing size and shape, which has sparked a growing interest in scientific research.71 The size and size distribution of nanoparticles are often determined via advanced characterization techniques such as atomic force microscopy (AFM), scanning electron microscopy (SEM), and transmission electron microscopy (TEM) for dry nanoparticles, as well as dynamic light scattering (DLS) for nanoparticles in suspension.76 In addition, zeta potential ( ) measurements determine the surface charges of nanoparticles and indicate the stability of a colloidal nanoparticle suspension, where colloids with mV are stable and unlikely to aggregate.77

Nanoparticle synthesis is classified into the “top-down” and “bottom-up” approaches, depending on whether the starting material is a bulk material or atoms/molecules.78 The top-down approach reduces a bulk material to nanometer size mostly through physical processes, such as mechanical milling, laser ablation, sputtering, and ultrasonic dispersion. In contrast, the bottom-up approach involves the growth and agglomeration of seeding particles through processes, such as chemical vapor deposition, solgel method, and supercritical fluid synthesis.78 Recently, there has been a rising demand for a green and sustainable synthetic route to replace organic solvents, by using environmentally benign solvents such as ionic liquid and supercritical fluid (most commonly, supercritical and water).79 As a bottom-up approach, synthesizing nanoparticles with supercritical in microfluidics enables continuous production of nanoparticles and achieves superior size control and narrow size distribution.33 Section III presents a literature review on the current state-of-the-art in nanoparticle synthesis using supercritical in microfluidic systems, with key information presented in Table II. We organize this section into subsections based on nanoparticle applications, including catalysis, semiconductor, nucleation and growth studies, and drug delivery.

TABLE II.

Literature summary of nanoparticle synthesis using supercritical in microfluidics.

| Microfluidic | Size | Pressure | Temperature | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| design | Nanoparticle | (nm) | (MPa) | (°C) | Reference |

| Co-flow | Palladium (Pd) nanocrystal | 3.6 ± 0.6 | 25 | 100 | Gendrineau et al.49 |

| Co-flow | Poly(3-hexylthiophene) (P3HT) nanoparticle | 36 ± 8 | 10 | 40 | Couto et al.50 |

| 47 ± 12 | 8 | 50 | |||

| Co-flow | Tetraphenylethylene (TPE) nanoparticle | 9 ± 3 | 10 | 40 | Jaouhari et al.80 |

| Co-flow | Fluorescent organic nanoparticle | 16 ± 4 | 10 | 40 | Jaouhari et al.46 |

| T-junction | Polyvinyl alcohol (PVA) nanoparticle | 10–20a | 8.5–12 | 36.85 | Murakami and Shimoyama51 |

| T-junction | Ibuprofen/PVA nanoparticleb | 231 ± 31 | 8.5–12 | 36.85 | Murakami and Shimoyama52 |

| T-junction | Timolol maleate (TM)-loaded liposome | 80–3000c | 10 | 40 | Murakami et al.54 |

| T-junction | PEGylated liposome | 270–417d | 10 | 40 | Akiyama et al.53 |

| T-junction | Stearic acid solid lipid nanopariticle | 20–150e | 8.5–20 | 40 | Wijakmatee et al.81 |

Depending on the degree of PVA hydrolyzed.

Ibuprofen/PVA nanoparticles were functionalized by chitosan.

Depending on the co-solvent (ethanol) flow rate.

Depending on the ratio of PEG:lipid.

Depending on the pressure and total flow rate of water and oil phases.

A. Synthesis of metal nanoparticles for catalysis

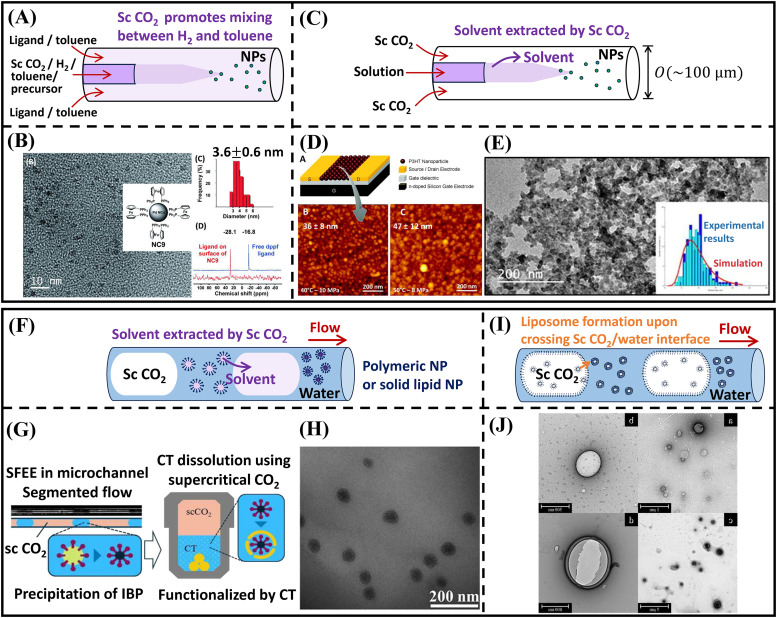

Metallic nanoparticles, such as palladium ( ) and nickel ( ), have been widely used as heterogeneous catalysts in chemical reactions benefiting from their high surface-to-volume ratio, which leads to improved catalytic performance.74,82 Researchers have used a coaxial-flow microfluidic design for synthesizing nanocrystals, a schematic of which has been illustrated in Fig. 4(a).49 The inner flow consists of a mixture of precursor/sc / /toluene. As the fluid mixture contacted the outer flow consisting of ligands and toluene, the -nanocrystals nucleated and were functionalized by different ligands.49 The presence of supercritical greatly enhanced the solubility of in toluene, thereby promoting the hydrogen reduction of the precursor and successfully producing -nanocrystals at 100 °C and 25 MPa.49 The high-resolution transmission electron microscopy (HRTEM) showed a particle size distribution of nm, seen in Fig. 4(b).49 The catalytic efficiency of the -nanocrystals was evaluated in reactions involving boron compounds.49 The resulting yield was highly dependent on the ligand attached to the nanoparticles, demonstrating that the functional group on -nanocrystals needs to be tailored for targeted reactions.49

FIG. 4.

Supercritical -assisted nanoparticle synthesis in microfluidics. (a) Supercritical enhances the mixing of and toluene, thereby promoting nanocrystal formation; the schematic is adapted from Ref. 49. Reproduced with permission from Gendrineau et al., Angew. Chem. 124, 8653–8656 (2012). Copyright 2012 John Wiley and Sons. (b) Palladium nanocrystal synthesis assisted by sc in microfluidics as catalysts. The surface of palladium nanocrystals was functioned by different ligands.49 Reproduced with permission from Gendrineau et al., Angew. Chem. 124, 8653–8656 (2012). Copyright 2012 John Wiley and Sons. (c) Schematic illustration of nanoparticle formation in co-axial flow microfluidics, where supercritical extracts the solvent and nanoparticles precipitate. (d) Sc assisted synthesis of poly(3-hexylthiophene) nanoparticles in microfluidics for OFET applications.50 Reproduced with permission from Couto et al., Chem. Commun. 51, 1008–1011 (2015). Copyright 2015 Royal Society of Chemistry. (e) Nucleation and growth of organic nanoparticles synthesized with sc in microfluidics.80 Reproduced with permission from Jaouhari et al., Chem. Eng. J. 397, 125333 (2020). Copyright 2020 Elsevier. (f) The process of supercritical fluid extraction of emulsion (SFEE) to fabricate polymeric nanoparticles of solid lipid nanoparticles for drug delivery applications. (g) Ibuprofen-loaded nanosuspension functioned by chitosan produced using sc in microfluidics.52 Reproduced with permission from Murakami and Shimoyama, J. Supercrit. Fluids 128, 121–127 (2017). Copyright 2017 Elsevier. (h) Solid lipid nanoparticles of stearic acid generated in microfluidic flow using sc .81 Reproduced with permission from Wijakmatee et al., Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 61, 9274–9282 (2022). Copyright 2022 American Chemical Society. (i) Synthesis of liposomes in microfluidics using supercritical . (j) TEM images of liposomes produced using sc in a LipTube micro-mixing device.54 Reproduced with permission from Murakami et al., Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 61, 14598–14608 (2022). Copyright 2022 American Chemical Society.

B. Synthesis of semiconducting nanoparticles

The conjugated polymer has alternating single and double bonds in the carbon backbone chain, and its molecular structure induces high charge transport and semiconductive properties.83 The organic semiconducting nanoparticles are light-weight, low-cost, and flexible, making them well-suited for applications in photovoltaic cells, organic field-effect transistors (OFETs), and organic light-emitting diode (OLED). These semiconducting nanoparticles are prepared mostly through solution-based synthesis methods in a macroscopic batch process, sometimes leading to a broad size distribution.77 Supercritical has been used as an anti-solvent to fabricate semi-conducting organic poly(3-hexylthiophene) (P3HT) nanoparticles in microfluidics.50 P3HT was first dissolved in an organic solvent, tetrahydrofuran (THF).50 As shown in Fig. 4(c), P3HT solution in THF was injected as the inner jet in a co-flow microfluidic device, where supercritical was introduced as the outer phase that extracted THF while P3HT nanoparticles precipitated.50 Downstream of the microfluidic device, the system was depressurized, and the P3HT nanoparticles were directly spray-coated on an organic field-effect transistor (OFET) substrate, where the substrate and AFM images of the nanoparticle layer are seen in Fig. 4(d).50 AFM measurements showed the P3HT nanoparticles were nm when T=40 °C, MPa.50 The transfer characteristic measurement (of the drain current vs the gate voltage) demonstrated a comparable performance compared to a classical deposition approach.50

C. Nucleation and growth of organic nanoparticles

Despite many experimental efforts synthesizing nanoparticles using supercritical in microfluidics, understanding the physics of nucleation and growth remains challenging, since the resolution of optical imaging systems is limited by light diffraction to a sub-micrometer scale. Jaouhari et al. investigated the precipitation of tetraphenylethylene (TPE) nanoparticles in THF using supercritical as an antisolvent [see Fig. 4(e)].80 Ultra-small TPE nanoparticles of size nm were generated in the microfluidics in a fast-mixing turbulent flow of .80 Numerical simulation suggested that the characteristic mixing time between THF and supercritical was crucial for the nanoparticle size and distribution.80 For a turbulent flow in microfluidics, the mixing time was considerably reduced to 0.01 ms, comparable to the nucleation time, and resulted in small and uniform-sized nanoparticles.80 Using a similar microfluidic setup, the authors extended their investigation to fluorescent organic nanoparticles and visualized the fluorescent intensity field near the mixing zone using a confocal microscope.46 Similarly, homogeneous nucleation occurred due to fast mixing time computed from numerical simulation, resulting in an experimental nanoparticle size of nm.46

D. Nanoparticle synthesis for drug delivery applications

Recently, supercritical has emerged as a novel approach for synthesizing pharmaceutical nanoparticles in microfluidics, owing to its benign nature to the health and environment. The delivery of active pharmaceutical ingredients (APIs) is often limited by the low solubility of many drugs in water, as well as their instability in the colloidal system, ultimately leading to deficient bioactivity.84 One effective method to improve drug loading is to use nanoparticles to encapsulate hydrophilic or hydrophobic drugs and form a suspension in water. The advancement of nanomedicine also provides opportunities for personalized precision medicine.85 Nanomedicines approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) fell into three categories: lipid-based, polymeric, and inorganic nanoparticles.85 In drug delivery applications, the nanoparticle size influences cellular uptake and drug transportation in the human body, and as a result, significantly affects therapeutic effectiveness.86 A major concern in the conventional production of nanoparticles as drug carriers is the toxicity associated with the organic solvent residuals. To mitigate this, using supercritical to fabricate nanoparticles in microfluidics has been investigated as an innovative approach for drug delivery applications.51–54,81 Microfluidics has demonstrated excellent control over fluid flow to encapsulate microparticles in emulsion droplets,55,87 hence exhibiting great potential for nanoparticle production in drug delivery applications. From Table II, the size of the synthesized nanoparticles was observed to vary based on experimental pressure, co-solvent flow rate, and the presence of surface functional groups.

One way to improve the drug loading is to encapsulate the API within a biocompatible and biodegradable polymeric carrier. Figure 4(f) conceptually illustrates a microfluidic approach to generate polyvinyl alcohol (PVA) nanoparticle suspension using the technique of supercritical fluid extraction of emulsion (SFEE). An oil-in-water (O/W) emulsion was first prepared by mixing PVA, water, and an organic solvent [i.e., ethyl acetate (EA)], and it was subsequently injected into the microchannel as a continuous phase. Supercritical forms a dispersed phase and extracts EA from the emulsion. In the experimental study by Murakami and Shimoyama, Sc was able to extract EA completely when using 78%–82% hydrolyzed PVA.51 In a separate investigation, Murakami and Shimoyama loaded the EA/PVA/water emulsion with ibuprofen where the ibuprofen/PVA nanoparticles were further functionalized by chitosan (CT), as illustrated in Fig. 4(g).52 Chitosan has pH-dependent solubility and can rapidly dissolve in an acidic environment, facilitating a controlled release of the drug compounds.52 The aqueous PVA/CT/IBP nanoparticle suspension was able to achieve 0.3 wt. % ibuprofen concentration, which is 140 times higher than in its water-saturated solution, with an average particle size of nm from DLS analysis.52 This result demonstrates the superior drug loading capacity of nanoparticles synthesized via supercritical in microfluidics.

Solid lipid nanoparticles emerged recently as a promising drug carrier due to their improved physical stability. The nanomedicine is immobilized inside a solid lipid core surrounded by a surfactant shell, forming a micellar structure.86 As seen in Figs. 4(f) and 4(h), SFEE can be implemented to produce solid lipid nanoparticles. In comparison to the conventional solvent evaporation method, the microfluidic SFEE approach has been reported with reduced nanoparticle size and lower solvent residual.81 Interestingly, particle aggregation occurred in experiments at a pressure above 10 MPa, leading to a larger average nanoparticle size.81

In addition to polymeric and solid lipid nanoparticles, liposome is another type of drug carrier, which has been fabricated using supercritical in microfluidics. A liposome, consisting of one or several lipid bilayers, serves as a nano-sized carrier for both hydrophilic and hydrophobic drugs.86 The versatile structure of liposomes enables drug encapsulation by enclosing the hydrophilic compounds within the interior, or trapping the hydrophobic compounds inside the lipid bilayers.86 The preparation of liposomes conventionally involves organic solvents such as ethanol, isopropanol (IPA) or EA. Figure 4(i) demonstrates the process of producing liposomes with supercritical in microfluidics. The emulsions, which have a reverse micelle structure, are initially present in the phase. As the emulsions are transported from to water, they self-assemble into liposomes upon crossing the interface, as indicated by the arrow in Fig. 4(i). Murakami et al. utilized this microfluidic approach to produce liposomes loaded with a model compound–timolol maleate (TM).54 The microfluidic approach achieved a remarkable size control of the liposomes, ranging from 80 to 3000 nm depending on the co-solvent flow rate, with the TEM images of the liposomes presented in Fig. 4(j).54 The encapsulation efficiency of TM was as high as 70% when ethanol was used as the co-solvent with a flow rate above 0.2 ml min−1.54 Using a similar microfluidic method, liposomes could also be surface modified with poly-(ethylene glycol) (PEG) to form PEGylated liposomes.53 PEG is a biocompatible and inert polymer, which protects liposomes during delivery and avoids severe immune response in the human body.53 Zeta potential measurements confirmed the successful PEG coating of the liposomes, with the thickness of the polymer layer controlled by varying the PEG-lipid concentration.53

In this part, we review several recent investigations on supercritical -assisted nanoparticle synthesis, with applications ranging from chemical catalysis to drug delivery. The microfluidic approach outperforms the conventional solvent evaporation method by synthesizing nanoparticles with reduced size, narrower size distribution, and lower solvent residuals.81 For pharmaceutical applications, in particular, the nano-sized drug carriers are outstanding in loading a high amount of active ingredients compared with the traditional approach, making it worthy of further investigation on the mechanisms of mass transfer.52 Additionally, the precise fluid manipulation offered by microfluidics enables surface modification of the nanoparticles, opening up opportunities for personalized nano-medicine in the future. Moreover, as noted in Table II, all experiments on supercritical -assisted nanoparticle synthesis were performed at a constant temperature, and the effect of temperature on nanoparticle size and distribution is yet to be explored.

IV. CHEMICAL REACTION USING SUPERCRITICAL CO2 IN MICROREACTORS

Supercritical has also been utilized in chemical reactions to eliminate the mass transfer barrier and intensify the reaction rate. In organic reactions such as hydrogenation and esterification, supercritical often facilitates as a solvent medium for the reactants that are usually poorly soluble with one another. The reaction rate can be further enhanced through rapid mixing induced by the microfluidic design, compared to batch experiments using bench-top glassware.18 The small size of the microreactor has many merits when it comes to the field of organic synthesis; on the one hand, it promotes the contact between reactants due to the large surface-to-volume ratio, and on the other hand, it enables the safe handling of hazardous or explosive substances due to the small sample volume. Section IV summarizes the research efforts to utilize supercritical in chemical reactions within microreactors, as summarized in Table III.

TABLE III.

Literature summary of chemical reactions using supercritical in microreactors.

| Microfluidic | Pressure | Temperature | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| design | Reaction | (MPa) | (°C) | Reference |

| Microreactora | Hydrogenation of six substances | 9 | 60 | Kobayashi et al.88 |

| Microreactor | Hydrogenation of cyclohexene | 8–15 | 40–70 | Trachsel et al., 200989 |

| Stainless-steel capillary | Hydrogenation of to methane | 20–95 | 450 | Tidona et al.90 |

| Microreactor | Esterification of phthalic anhydride 1 + methanol | 8–11 | 20–100 | Benito-Lopez et al.91 |

| Microreactor | Esterification of oleic acid + methanol | 10 | 60–120 | Quitain et al.92 |

The solid catalyst Pd was immobilized in the microchannel.

A. Hydrogenation reaction

Hydrogenation is an important reaction in the food and petrochemical industry, as it transforms unsaturated fat or hydrocarbon into saturated ones by adding hydrogen ( ) and converting the double (or triple) bonds to single bonds. Heterogeneous catalysts, such as palladium (Pd), nickel (Ni), and platinum (Pt), are commonly used in hydrogenation reactions. The reaction rate of heterogeneous hydrogenation is limited when using a conventional solvent, which is largely due to the low solubility of in these solvents.93 Supercritical has been discovered as an ideal solvent (or reaction medium) for hydrogenation reactions, as it forms a homogeneous phase with and removes the interphase mass transfer resistance.93 Incorporating supercritical with the hydrogenation in a microreactor is beneficial for creating efficient solid–liquid–gas contact.88 Kobayashi et al. innovatively designed a microchannel covered by a thin layer of solid Pd catalyst immobilized on the channel wall.88,94 The reactants, and , were introduced to an external high-pressure cell and subsequently injected into the Pd-immobilized microchannel for reaction.88 Six substances containing double or triple bonds were tested, where the double or triple bonds were reduced smoothly in the Pd-coated microchannel.88 The reaction happened within 1 s with a yield rate higher than 90%.88

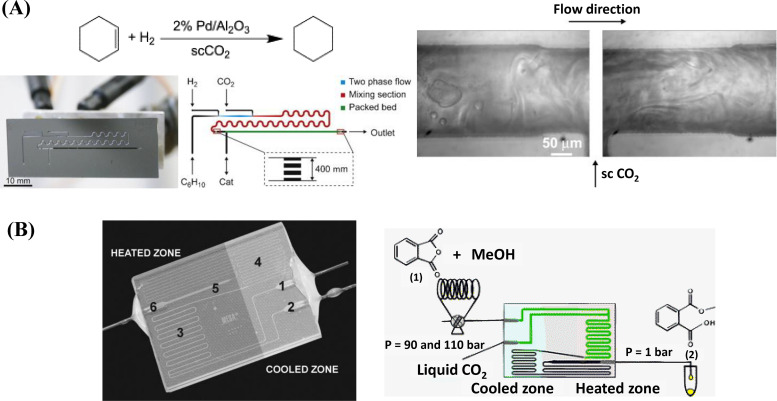

Owing to the optical transparency of microfluidics, the hydrogenation reaction has also been visualized in situ, confirming that supercritical creates an environment for rapid mixing between the reactants.89 Trachsel et al. performed the hydrogenation of cyclohexene in a microreactor, where and cyclohexene were simultaneously introduced at the first T-junction as a segmented gas–liquid flow.89 In the second T-junction, when was introduced to the –cyclohexene mixture, the phase boundaries vanished and the mixing was chaotic between , cyclohexene, and as a single phase, as seen in Fig. 5(a).89 A higher reaction rate was observed as the temperature increased from 40 to 70 °C, whereas the change in reaction rate was insignificant with varying pressure.89 Other than acting as a solvent, itself can undergo hydrogenation to produce methanol as a source of fuel. Tidona et al. investigated supercritical hydrogenation in a stainless-steel microcapillary, and the chemical reaction was carried out at ultra-high temperature of T = 450 °C and varying pressure of –90 MPa.90 conversion rate was well below the equilibrium of the reaction network due to insufficient residence time for conversion.90 Same microreactor has also been incorporated with Raman spectroscopy to probe the phase behavior of on-chip at different pressures and temperatures.47

FIG. 5.

Chemical reaction using sc in microfluidics. (a) Hydrogenation reaction of cyclohexene in a silicon-glass microreactor with the addition of sc as a solvent, where intensified mixing was observed upon sc injection from the microscopic images on the right.89 Reproduced with permission from Trachsel et al., J. Supercrit. Fluids 48, 146–153 (2009). Copyright 2009 Elsevier. (b) The glass microreactor and experimental setup were designed by Benito-Lopez et al. to perform an esterification reaction of phthalic anhydride and methanol, with sc as a co-solvent that leads to rate enhancement.91 Reproduced with permission from Benito-Lopez et al., Lab Chip 7, 1345–1351 (2007). Copyright 2007 Royal Society of Chemistry.

B. Esterification reaction

Esterification is a critical organic reaction to produce flavoring agents, fragrances, pharmaceuticals, and soaps.95 It combines a carboxylic acid with alcohol to form an ester and water. Despite the significance of esterification reactions in a variety of commercial products, achieving a high conversion rate is still challenging due to the poor solubility between reactants and the slow reaction kinetics.95 Benito-Lopez et al. first investigated the esterification reaction of phthalic anhydride 1 with methanol using a microreactor shown in Fig. 5(b).91 Adding supercritical as co-solvent for the reaction reduces the viscosity of the supercritical –methane mixture and intensifies the reaction rate constants by O( ) compared to similar experimental conditions without the addition of .91 The second-order rate constants of the reaction were improved when increasing the temperature and pressure in microfluidics, compared to batch-size reactions at atmospheric pressure.91 The significant rate enhancement can be potentially attributed to a different reaction mechanism, where induces the formation of localized clusters of the reactant molecules.91 Quitain et al. studied the reaction between methanol and oleic acid in a microreactor with supercritical for biodiesel synthesis at –12 MPa and –120 °C.92 In this experimental study, supercritical acts as a solvent for both reactants, as methanol and oleic acid are immiscible.92 The reaction product was oleic acid methyl ester (OAME), and the yield was determined by gas chromatographic analysis, where the reaction yield was found to increase with a higher temperature and a longer residence time in the microreactor.92 Furthermore, by recirculating the reaction products, the yield was found to improve significantly.92

In this section, we review two organic reactions in microreactors, namely, hydrogenation and esterification, where supercritical was used as a solvent medium for reactants that would otherwise exhibit weak solubility in each other. Overall, it has been observed that supercritical -assisted chemical reactions significantly enhanced both hydrogenation and esterification processes, leading to higher reaction yields compared to batch reactions without supercritical . In the chemical reactions using supercritical , the reaction yield increased with a higher temperature and longer residence time in the microchannel. Given the safe handling (due to the small reagent volume) and rapid reaction, microfluidics provides an advantageous platform for visualizing fluid mixing and studying the reaction kinetics of supercritical -enhanced chemical reactions. However, it is unlikely that microfluidic reactors will replace batch-scale chemical reactors due to their low throughput currently.

V. CONCLUSION AND OUTLOOK

The adoption of supercritical in microfluidics in applications has been a promising and ongoing field of research. This review highlighted three applications: solvent extraction, nanoparticle synthesis, and chemical reactions in pharmaceuticals, food science, chemical catalysis, and beyond. In these studies, microfluidics offers a convenient approach for flow visualization and process optimization. Despite these many advantages, several challenges could limit the advancement of supercritical applications in microfluidics. These challenges include achieving the high pressure in microfluidics required to reach the supercritical state of . Additionally, fabricating silicon-glass chips in cleanroom facilities is an expensive process. From an extraction standpoint, although supercritical is an environmentally friendly solvent, its extraction efficiency can sometimes be low. For supercritical extraction of high value-added compounds in microfluidics, it is challenging to transfer the relevant technologies from academic research to industrial-scale production in a profitable way. The microfluidic approach will likely remain a valuable tool for investigation due to its optical access and fast processing times. Furthermore, in the complex processes discussed in the review, there remains a lack of comprehensive understanding of nanoparticle nucleation and growth, supercritical mass transfer mechanisms, and reaction kinetics. Without this fundamental knowledge, process optimization is challenging. Furthermore, scaling up the microfluidic process is essential for commercializing supercritical -assisted applications in microfluidics.

Supercritical applications in microfluidics encompass interdisciplinary studies involving fluid dynamics, mass transfer, chemistry, and more. For future investigations, it would be beneficial to scale up the microfluidics from academic research to a commercialized solution. This could be accomplished through the use of parallel microfluidic channels or parallel microfluidic systems. Recently, numerical simulations have been performed to investigate the mixing performance when scaling up nanoparticle production using supercritical in a microreactor from laboratory to industrial scale.96 This novel approach opens up opportunities to predict and ensure sufficient mixing is achieved before scaling up the microreactor.96 Numerical tools such as computational fluid dynamics (CFD) and machine learning are beneficial for predicting and optimizing mixing dynamics and production yield, which would attract more emphasis in future research on supercritical .96,97 Additionally, it would be valuable to systematically compare solvent residual, techno-economic performance, and the therapeutic effectiveness between the supercritical -assisted approach in microfluidics and the conventional solvent evaporation methods. To enhance the efficiency of supercritical extraction, it is crucial to thoroughly understand the fluid mixing and mass transfer process associated with these applications. The effects of microfluidic design, supercritical flow, and recirculation on nanoparticle nucleation and growth rates, as well as their size and distribution, are areas that require further investigation.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We gratefully acknowledge support from the Canada First Research Excellence Fund (CFREF), Future Energy System (FES T02-P05 CCUS projects) at the University of Alberta, and Canada Foundation for Innovation (CFI 34546). P.A.T. holds a Canada Research Chair (CRC) in Fluids and Interfaces and gratefully acknowledges funding from the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada (NSERC) and Alberta Innovates (AI), in particular, the NSERC Canada Research Chairs Program (CRC 233147) and Discovery Grant (No. RGPIN-2020-05511).

AUTHOR DECLARATIONS

Conflict of Interest

The authors have no conflicts to disclose.

Author Contributions

Junyi Yang: Visualization (equal); Writing – original draft (lead). Peichun Amy Tsai: Conceptualization (lead); Funding acquisition (lead); Supervision (lead); Visualization (equal); Writing – review & editing (lead).

DATA AVAILABILITY

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no new data were created or analyzed in this study.

REFERENCES

- 1.Noyori R., “Supercritical fluids: Introduction,” Chem. Rev. 99(2), 353–634 (1999). 10.1021/cr980085a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Saito M., “History of supercritical fluid chromatography: Instrumental development,” J. Biosci. Bioeng. 115(6), 590–599 (2013). 10.1016/j.jbiosc.2012.12.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Girard E., Tassaing T., Daniel Marty J., and Destarac M., “Structure-property relationships in CO2-philic (Co)polymers: Phase behavior, self-assembly, and stabilization of water/CO2 emulsions,” Chem. Rev. 116(7), 4125–4169 (2016). 10.1021/acs.chemrev.5b00420 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.NIST, see https://webbook.nist.gov/chemistry/ for “Standard Reference Database” (2023) (last accessed October 31, 2023.

- 5.Jessop P. G., “Searching for green solvents,” Green Chem. 13(6), 1391–1398 (2011). 10.1039/c0gc00797h [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Clarke C. J., Chien Tu W., Levers O., Bröhl A., and Hallett J. P., “Green and sustainable solvents in chemical processes,” Chem. Rev. 118(2), 747–800 (2018). 10.1021/acs.chemrev.7b00571 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sahena F., Zaidul I. S. M., Jinap S., Karim A. A., Abbas K. A., Norulaini N. A. N., and Omar A. K. M., “Application of supercritical CO2 in lipid extraction—A review,” J. Food Eng. 95(2), 240–253 (2009). 10.1016/j.jfoodeng.2009.06.026 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Singh S., Kumar Verma D., Thakur M., Tripathy S., Patel A. R., Shah N., Lara Utama G., Prakash Srivastav P., Roberto Benavente-Valdés J., Chávez-González M. L., and Noe Aguilar C., “Supercritical fluid extraction (SCFE) as green extraction technology for high-value metabolites of algae, its potential trends in food and human health,” Food Res. Int. 150, 110746 (2021). 10.1016/j.foodres.2021.110746 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ahangari H., King J. W., Ehsani A., and Yousefi M., “Supercritical fluid extraction of seed oils—A short review of current trends,” Trends Food Sci. Technol. 111, 249–260 (2021). 10.1016/j.tifs.2021.02.066 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Padrela L., Rodrigues M. A., Duarte A., Dias A. M. A., Braga M. E. M., and de Sousa H. C., “Supercritical carbon dioxide-based technologies for the production of drug nanoparticles/nanocrystals—A comprehensive review,” Adv. Drug. Delivery Rev. 131, 22–78 (2018). 10.1016/j.addr.2018.07.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sauceau M., Fages J., Common A., Nikitine C., and Rodier E., “New challenges in polymer foaming: A review of extrusion processes assisted by supercritical carbon dioxide,” Prog. Polym. Sci. (Oxford) 36(6), 749–766 (2011). 10.1016/j.progpolymsci.2010.12.004 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lu J., Zhang H., Chen Y., Ge Y., and Liu T., “Effect of chain relaxation on the shrinkage behavior of TPEE foams fabricated with supercritical CO2,” Polymer 256, 125262 (2022). 10.1016/j.polymer.2022.125262 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Brunner G., “Applications of supercritical fluids,” Annu. Rev. Chem. Biomol. Eng. 1, 321–342 (2010). 10.1146/annurev-chembioeng-073009-101311 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zosel K., “Process for the decaffeination of coffee,” U.S. patent 4,260,639 (April 1981).

- 15.Knez Ž., Cör D., and Knez Hrnčič M., “Solubility of solids in sub- and supercritical fluids: A review,” J. Chem. Eng. Data 56, 694–719 (2011). 10.1021/je1011373 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Marre S., Roig Y., and Aymonier C., “Supercritical microfluidics: Opportunities in flow-through chemistry and materials science,” J. Supercrit. Fluids 66, 251–264 (2012). 10.1016/j.supflu.2011.11.029 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tabeling P., Optical Lithography (Oxford University Press, 2005). [Google Scholar]

- 18.DeMello A. J., “Control and detection of chemical reactions in microfluidic systems,” Nature 442(7101), 394–402 (2006). 10.1038/nature05062 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bayareh M., Nazemi Ashani M., and Usefian A., “Active and passive micromixers: A comprehensive review,” Chem. Eng. Process.—Process Intensif. 147, 1–19 (2020). 10.1016/j.cep.2019.107771 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhang F., Marre S., and Erriguible A., “Mixing intensification under turbulent conditions in a high pressure microreactor,” Chem. Eng. J. 382, 122859 (2020). 10.1016/j.cej.2019.122859 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bernades M., Capuano F., and Jofre L., “Microconfined high-pressure transcritical fluid turbulence,” Phys. Fluids 35(1), 015163 (2023). 10.1063/5.0135388 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bruce Nauman E., “Residence time theory,” Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 47(5), 3752–3766 (2008). 10.1021/ie071635a [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rodrigues A. E., “Residence time distribution (RTD) revisited,” Chem. Eng. Sci. 230, 116188 (2021). 10.1016/j.ces.2020.116188 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sebastian Cabeza V., Kuhn S., Kulkarni A. A., and Jensen K. F., “Size-controlled flow synthesis of gold nanoparticles using a segmented flow microfluidic platform,” Langmuir 28(17), 7007–7013 (2012). 10.1021/la205131e [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Liu N., Aymonier C., Lecoutre C., Garrabos Y., and Marre S., “Microfluidic approach for studying solubility in water and brine using confocal Raman spectroscopy,” Chem. Phys. Lett. 551, 139–143 (2012). 10.1016/j.cplett.2012.09.007 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Qin N., “Micro-scale studies on hydrodynamics and mass transfer of dense carbon dioxide segments in water,” Ph.D. thesis (University of Waterloo, 2017). [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ho T.-H., “Microfluidic investigations of mass transport at elevated pressure and salt precipitation,” Ph.D. thesis (University of Alberta, 2021). [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hsing Martin Ho T., Sameoto D., and Amy Tsai P., “Multiphase dispersions in microfluidics: Formation, phases, and mass transfer,” Chem. Eng. Res. Des. 174, 116–126 (2021). 10.1016/j.cherd.2021.07.006 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Martin Ho T.-H., Yang J., and Amy Tsai P., “Microfluidic mass transfer of at elevated pressures: Implications for carbon storage in deep saline aquifers,” Lab Chip 21(20), 3942–3951 (2021). 10.1039/D1LC00106J [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yang J. and Amy Tsai P., “Microfluidic mass transfer of supercritical in brine,” Chem. Eng. Sci. 300, 120543 (2024). 10.1016/j.ces.2024.120543 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Assmann N., Kaiser S., and Rudolf Von Rohr P., “Supercritical extraction of vanillin in a microfluidic device,” J. Supercrit. Fluids 67, 149–154 (2012). 10.1016/j.supflu.2012.03.015 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Assmann N., Werhan H., Ładosz A., and Rudolf von Rohr P., “Supercritical extraction of lignin oxidation products in a microfluidic device,” Chem. Eng. Sci. 99, 177–183 (2013). 10.1016/j.ces.2013.05.032 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Marre S. and Jensen K. F., “Synthesis of micro- and nanostructures in microfluidic systems,” Chem. Soc. Rev. 39(3), 1183–1202 (2010). 10.1039/b821324k [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Marre S., Lecoutre C., Garrabos Y., Fauveau C., Cario A., and Nguyen O., “Sapphire microreactors,” U.S. patent 2023/0133449 A1 (2023).

- 35.Sharma D., Nguyen O., Palencia F., Lecoutre C., Garrabos Y., Glockner S., Marre S., and Erriguible A., “Supercritical water oxidation using hydrothermal flames at microscale as a potential solution for organic waste treatment in space applications—A practical demonstration and numerical study,” Chem. Eng. J. 488, 150856 (2024). 10.1016/j.cej.2024.150856 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Luther S. K. and Braeuer A., “High-pressure microfluidics for the investigation into multi-phase systems using the supercritical fluid extraction of emulsions (SFEE),” J. Supercrit. Fluids 65, 78–86 (2012). 10.1016/j.supflu.2012.02.029 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Luther S. K., Schuster J. J., Leipertz A., and Braeuer A., “Microfluidic investigation into mass transfer in compressible multi-phase systems composed of oil, water and carbon dioxide at elevated pressure,” J. Supercrit. Fluids 84, 121–131 (2013). 10.1016/j.supflu.2013.10.002 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Qin N., Wen J. Z., and Ren C. L., “Highly pressurized partially miscible liquid-liquid flow in a micro-T-junction. I. Experimental observations,” Phys. Rev. E 95(4), 043110 (2017). 10.1103/PhysRevE.95.043110 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bao B., Riordon J., Xu Y., Li H., and Sinton D., “Direct measurement of the fluid phase diagram,” Anal. Chem. 88(14), 6986–6989 (2016). 10.1021/acs.analchem.6b01725 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bao B., Riordon J., Mostowfi F., and Sinton D., “Microfluidic and nanofluidic phase behaviour characterization for industrial CO2, oil and gas,” Lab Chip 17(16), 2740–2759 (2017). 10.1039/C7LC00301C [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gavoille T., Pannacci N., Bergeot G., Marliere C., and Marre S., “Microfluidic approaches for accessing thermophysical properties of fluid systems,” React. Chem. Eng. 4(10), 1721–1739 (2019). 10.1039/C9RE00130A [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Cheng X., Bang Qi Z., Burdyny T., Kong T., and Sinton D., “Low pressure supercritical CO2 extraction of astaxanthin from Haematococcus pluvialis demonstrated on a microfluidic chip,” Bioresour. Technol. 250, 481–485 (2018). 10.1016/j.biortech.2017.11.070 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Deleau T., Letourneau J. J., Camy S., Aubin J., and Espitalier F., “Determination of mass transfer coefficients in high-pressure CO2-H2O flows in microcapillaries using a colorimetric method,” Chem. Eng. Sci. 248, 117161 (2022). 10.1016/j.ces.2021.117161 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sell A., Fadaei H., Kim M., and Sinton D., “Measurement of diffusivity for carbon sequestration: A microfluidic approach for reservoir-specific analysis,” Environ. Sci. Technol. 47, 71–78 (2013). 10.1021/es303319q [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Nguyen P., Mohaddes D., Riordon J., Fadaei H., Lele P., and Sinton D., “Fast fluorescence-based microfluidic method for measuring minimum miscibility pressure of CO2 in crude oils,” Anal. Chem. 87(6), 3160–3164 (2015). 10.1021/ac5047856 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Jaouhari T., Marre S., Tassaing T., Fery-Forgues S., Aymonier C., and Erriguible A., “Investigating nucleation and growth phenomena in microfluidic supercritical antisolvent process by coupling in situ fluorescence spectroscopy and direct numerical simulation,” Chem. Eng. Sci. 248, 117240 (2022). 10.1016/j.ces.2021.117240 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Urakawa A., Trachsel F., Rudolf Von Rohr P., and Baiker A., “On-chip Raman analysis of heterogeneous catalytic reaction in supercritical CO2: Phase behaviour monitoring and activity profiling,” Analyst 133(10), 1352–1354 (2008). 10.1039/b808984c [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Deleau T., Fechter M. H. H., Letourneau J. J., Camy S., Aubin J., Braeuer A. S., and Espitalier F., “Determination of mass transfer coefficients in high-pressure two-phase flows in capillaries using Raman spectroscopy,” Chem. Eng. Sci. 228, 115960 (2020). 10.1016/j.ces.2020.115960 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Gendrineau T., Marre S., Vaultier M., Pucheault M., and Aymonier C., “Microfluidic synthesis of palladium nanocrystals assisted by supercritical CO2: Tailored surface properties for applications in boron chemistry,” Angew. Chem. 124(34), 8653–8656 (2012). 10.1002/ange.201203083 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Couto R., Chambon S., Aymonier C., Mignard E., Pavageau B., Erriguible A., and Marre S., “Microfluidic supercritical antisolvent continuous processing and direct spray-coating of poly(3-hexylthiophene) nanoparticles for OFET devices,” Chem. Commun. 51(6), 1008–1011 (2015). 10.1039/C4CC07878K [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Murakami Y. and Shimoyama Y., “Supercritical extraction of emulsion in microfluidic slug-flow for production of nanoparticle suspension in aqueous solution,” J. Supercrit. Fluids 118, 178–184 (2016). 10.1016/j.supflu.2016.08.009 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Murakami Y. and Shimoyama Y., “Production of nanosuspension functionalized by chitosan using supercritical fluid extraction of emulsion,” J. Supercrit. Fluids 128, 121–127 (2017). 10.1016/j.supflu.2017.05.014 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Akiyama R., Murakami Y., Inoue K., Orita Y., and Shimoyama Y., “Fabrication of PEGylated liposome in microfluidic flow process using supercritical CO2,” J. Nanoparticle Res. 24(12), 257 (2022). 10.1007/s11051-022-05635-9 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Murakami Y., Inoue K., Akiyama R., Orita Y., and Shimoyama Y., “LipTube: Liposome formation in the tube process using supercritical CO2,” Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 61(39), 14598–14608 (2022). 10.1021/acs.iecr.2c02095 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Duncanson W. J., Lin T., Abate A. R., Seiffert S., Shah R. K., and Weitz D. A., “Microfluidic synthesis of advanced microparticles for encapsulation and controlled release,” Lab Chip 12(12), 2135–2145 (2012). 10.1039/c2lc21164e [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Saadat M., Tsai P. A., Hsing Ho T., Øye G., and Dudek M., “Development of a microfluidic method to study enhanced oil recovery by low salinity water flooding,” ACS Omega 5(28), 17521–17530 (2020). 10.1021/acsomega.0c02005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Saadat M., Yang J., Dudek M., Øye G., and Amy Tsai P., “Microfluidic investigation of enhanced oil recovery: The effect of aqueous floods and network wettability,” J. Pet. Sci. Eng. 203, 108647 (2021). 10.1016/j.petrol.2021.108647 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Yang J., Saadat M., Azizov I., Dudek M., Øye G., and Amy Tsai P., “Wettability effect on oil recovery using rock-structured microfluidics,” Lab Chip 22(24), 4974–4983 (2022). 10.1039/D1LC01115D [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Yao C., Dong Z., Zhao Y., and Chen G., “An online method to measure mass transfer of slug flow in a microchannel,” Chem. Eng. Sci. 112, 15–24 (2014). 10.1016/j.ces.2014.03.016 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Yao C., Ma H., Zhao Q., Liu Y., Zhao Y., and Chen G., “Mass transfer in liquid-liquid Taylor flow in a microchannel: Local concentration distribution, mass transfer regime and the effect of fluid viscosity,” Chem. Eng. Sci. 223, 115734 (2020). 10.1016/j.ces.2020.115734 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Kazan A., “Supercritical applications in microfluidic systems,” Microfluid. Nanofluidics 26(9), 1–16 (2022). 10.1007/s10404-022-02574-8 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Stevens G. W., Lo T. C., and Baird M. H. I., “Extraction, liquid-liquid,” in Kirk-Othmer Encyclopedia of Chemical Technology (John Wiley and Sons, Inc, 2018), pp. 1–60.

- 63.Herrero M., Mendiola J. A., Cifuentes A., and Ibáñez E., “Supercritical fluid extraction: Recent advances and applications,” J. Chromatogr. A 1217(16), 2495–2511 (2010). 10.1016/j.chroma.2009.12.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Molino A., Mehariya S., Di Sanzo G., Larocca V., Martino M., Paolo Leone G., Marino T., Chianese S., Balducchi R., and Musmarra D., “Recent developments in supercritical fluid extraction of bioactive compounds from microalgae: Role of key parameters, technological achievements and challenges,” J. CO2 Util. 36, 196–209 (2020). 10.1016/j.jcou.2019.11.014 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Houng P., Murakami Y., and Shimoyama Y., “Effect of slug flow pattern on supercritical extraction of phenolic compounds from aqueous solutions,” J. Supercrit. Fluids 163, 104885 (2020). 10.1016/j.supflu.2020.104885 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Houng P., Murakami Y., and Shimoyama Y., “Micro-mixing in flow-type process for supercritical CO2 extraction of ferulic acid and gallic acid from aqueous solution,” J. CO2 Util. 47, 101503 (2021). 10.1016/j.jcou.2021.101503 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Cheng X., Riordon J., Nguyen B., Ooms M. D., and Sinton D., “Hydrothermal disruption of algae cells for astaxanthin extraction,” Green Chem. 19(1), 106–111 (2017). 10.1039/C6GC02746F [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Cerro D., Rojas A., Torres A., Villegas C., José Galotto M., Guarda A., and Romero J., “Nanoencapsulation of food-grade bioactive compounds using a supercritical fluid extraction of emulsions process: Effect of operational variables on the properties of nanocapsules and new perspectives,” LWT 184, 115115 (2023). 10.1016/j.lwt.2023.115115 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Yin Chu L., Utada A. S., Shah R. K., Woong Kim J., and Weitz D. A., “Controllable monodisperse multiple emulsions,” Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 46(47), 8970–8974 (2007). 10.1002/anie.200701358 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Thiele J., Abate A. R., Cheung Shum H., Bachtler S., Förster S., and Weitz D. A., “Fabrication of polymersomes using double-emulsion templates in glass-coated stamped microfluidic devices,” Small 6(16), 1723–1727 (2010). 10.1002/smll.201000798 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Heiligtag F. J. and Niederberger M., “The fascinating world of nanoparticle research,” Mater. Today 16(7-8), 262–271 (2013). 10.1016/j.mattod.2013.07.004 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Talapin D. V. and Shevchenko E. V., “Introduction: Nanoparticle chemistry,” Chem. Rev. 116(18), 10343–10345 (2016). 10.1021/acs.chemrev.6b00566 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Fan Y., Fowler G. D., and Zhao M., “The past, present and future of carbon black as a rubber reinforcing filler—A review,” J. Cleaner Prod. 247, 119115 (2020). 10.1016/j.jclepro.2019.119115 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Astruc D., “Introduction: Nanoparticles in Catalysis,” Chem. Rev. 120(2), 461–463 (2020). 10.1021/acs.chemrev.8b00696 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Park H., Soo Kim J., Kim S., Sol Ha E., Soo Kim M., and Joo Hwang S., “Pharmaceutical applications of supercritical fluid extraction of emulsions for micro-/nanoparticle formation,” Pharmaceutics 13(11), 1928 (2021). 10.3390/pharmaceutics13111928 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Modena M. M., Rühle B., Burg T. P., and Wuttke S., “Nanoparticle characterization: What to measure?,” Adv. Mater. 31(32), 1901556 (2019). 10.1002/adma.201901556 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Zangoli M. and Di Maria F., “Synthesis, characterization, and biological applications of semiconducting polythiophene-based nanoparticles,” View 2(1), 1–18 (2021). 10.1002/VIW.20200086 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Baig N., Kammakakam I., Falath W., and Kammakakam I., “Nanomaterials: A review of synthesis methods, properties, recent progress, and challenges,” Mater. Adv. 2(6), 1821–1871 (2021). 10.1039/D0MA00807A [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Duan H., Wang D., and Li Y., “Green chemistry for nanoparticle synthesis,” Chem. Soc. Rev. 44(16), 5778–5792 (2015). 10.1039/C4CS00363B [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Jaouhari T., Zhang F., Tassaing T., Fery-Forgues S., Aymonier C., Marre S., and Erriguible A., “Process intensification for the synthesis of ultra-small organic nanoparticles with supercritical CO2 in a microfluidic system,” Chem. Eng. J. 397, 125333 (2020). 10.1016/j.cej.2020.125333 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Wijakmatee T., Shimoyama Y., and Orita Y., “Integrated micro-flow process of emulsification and supercritical fluid emulsion extraction for stearic acid nanoparticle production,” Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 61(26), 9274–9282 (2022). 10.1021/acs.iecr.1c05062 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Joe Ndolomingo M., Bingwa N., and Meijboom R., “Review of supported metal nanoparticles: Synthesis methodologies, advantages and application as catalysts,” J. Mater. Sci. 55(15), 6195–6241 (2020). 10.1007/s10853-020-04415-x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Osaka I., “Semiconducting polymers based on electron-deficient -building units,” Polym. J. 47(1), 18–25 (2015). 10.1038/pj.2014.90 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Kumar Kankala R., Yao Xu P., Qi Chen B., Bin Wang S., and Zheng Chen A., “Supercritical fluid (SCF)-assisted fabrication of carrier-free drugs: An eco-friendly welcome to active pharmaceutical ingredients (APIs),” Adv. Drug. Delivery Rev. 176, 113846 (2021). 10.1016/j.addr.2021.113846 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Mitchell M. J., Billingsley M. M., Haley R. M., Wechsler M. E., Peppas N. A., and Langer R., “Engineering precision nanoparticles for drug delivery,” Nat. Rev. Drug Discovery 20(2), 101–124 (2021). 10.1038/s41573-020-0090-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Tenchov R., Bird R., Curtze A. E., and Zhou Q., “Lipid nanoparticles from liposomes to mRNA vaccine delivery, a landscape of research diversity and advancement,” ACS Nano 15(11), 16982–17015 (2021). 10.1021/acsnano.1c04996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Li W., Zhang L., Ge X., Xu B., Zhang W., Qu L., Hyung Choi C., Xu J., Zhang A., Lee H., and Weitz D. A., “Microfluidic fabrication of microparticles for biomedical applications,” Chem. Soc. Rev. 47(15), 5646–5683 (2018). 10.1039/C7CS00263G [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Kobayashi J., Mori Y., and Kobayashi S., “Hydrogenation reactions using scCO2 as a solvent in microchannel reactors,” Chem. Commun. 2005(20), 2567–2568. 10.1039/B501169H [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Trachsel F., Tidona B., Desportes S., and Rudolf von Rohr P., “Solid catalyzed hydrogenation in a Si/glass microreactor using supercritical CO2 as the reaction solvent,” J. Supercrit. Fluids 48(2), 146–153 (2009). 10.1016/j.supflu.2008.09.026 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Tidona B., Urakawa A., and Rudolf von Rohr P., “High pressure plant for heterogeneous catalytic CO2 hydrogenation reactions in a continuous flow microreactor,” Chem. Eng. Process.: Process Intensif. 65, 53–57 (2013). 10.1016/j.cep.2013.01.001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Benito-Lopez F., Tiggelaar R. M., Salbut K., Huskens J., Egberink R. J. M., Reinhoudt D. N., Gardeniers H. J. G. E., and Verboom W., “Substantial rate enhancements of the esterification reaction of phthalic anhydride with methanol at high pressure and using supercritical CO2 as a co-solvent in a glass microreactor,” Lab Chip 7(10), 1345–1351 (2007). 10.1039/b703394j [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Quitain A. T., Mission E. G., Sumigawa Y., and Sasaki M., “Supercritical carbon dioxide-mediated esterification in a microfluidic reactor,” Chem. Eng. Process.: Process Intensif. 123, 168–173 (2018). 10.1016/j.cep.2017.11.002 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Dierk Grunwaldt J., Wandeler R., and Baiker A., “Supercritical fluids in catalysis: Opportunities of in situ spectroscopic studies and monitoring phase behavior,” Catal. Rev. 45(1), 1–96 (2003). 10.1081/CR-120015738 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Kobayashi J., Mori Y., Okamoto K., Akiyama R., Ueno M., Kitamori T., and Kobayashi S., “A microfluidic device for conducting gas-liquid-solid hydrogenation reactions,” Science 304(5675), 1305–1308 (2004). 10.1126/science.1096956 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Khan Z., Javed F., Shamair Z., Hafeez A., Fazal T., Aslam A., Zimmerman W. B., and Rehman F., “Current developments in esterification reaction: A review on process and parameters,” J. Ind. Eng. Chem. 103, 80–101 (2021). 10.1016/j.jiec.2021.07.018 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Glockner S., Jost A. M. D., and Erriguible A., “Advanced petascale simulations of the scaling up of mixing limited flow processes for materials synthesis,” Chem. Eng. J. 431(P1), 133647 (2022). 10.1016/j.cej.2021.133647 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Roach L., Marco Rignanese G., Erriguible A., and Aymonier C., “Applications of machine learning in supercritical fluids research,” J. Supercrit. Fluids 202, 106051 (2023). 10.1016/j.supflu.2023.106051 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no new data were created or analyzed in this study.