Abstract

The nucleocapsid of the hepatitis B virus (HBV) is composed of 180 to 240 copies of the HBV core (HBc) protein. HBc antigen (HBcAg) capsids are extremely immunogenic and can activate naive B cells by cross-linking their surface receptors. The molecular basis for the interaction between HBcAg and naive B cells is not known. The functionality of this activation was evidenced in that low concentrations of HBcAg, but not the nonparticulate homologue HBV envelope antigen (HBeAg), could prime naive B cells to produce anti-HBc in vitro with splenocytes from HBcAg- and HBeAg-specific T-cell receptor transgenic mice. The frequency of these HBcAg-binding B cells was estimated by both hybridoma techniques and flow cytometry (B7-2 induction and direct HBcAg binding) to be approximately 4 to 8% of the B cells in a naive spleen. Cloning and sequence analysis of the immunoglobulin heavy- and light-chain variable (VH and VL) domains of seven primary HBcAg-binding hybridomas revealed that six (86%) were related to the murine and human VH1 germ line gene families and one was related to the murine VH3 family. By using synthetic peptides spanning three VH1 sequences, one VH3 sequence, and one VLκV sequence, a linear motif in the framework region 1 (FR1)complementarity-determining region 1 (CDR1) junction of the VH1 sequence was identified that bound HBcAg. Interestingly, the HBcAg-binding motif was present in the VL domain of the HBcAg-binding VH3-encoded antibody. Finally, two monoclonal antibodies containing linear HBcAg-binding motifs blocked HBcAg presentation by purified naive B cells to purified HBcAg-primed CD4+ T cells. Thus, the ability of HBcAg to bind and activate a high frequency of naive B cells seems to be mediated through a linear motif present in the FR1-CDR1 junction of the heavy or light chain of the B-cell surface receptor.

The nucleocapsid of the hepatitis B virus (HBV) is extremely immunogenic in all of the vertebrate hosts that have been tested. The icosahedral nucleocapsid is composed of 180 or 240 subunits of a 183-residue protein and is known as the HBV core (HBc) antigen (HBcAg) (8). The subunits are clustered as dimers, producing spikes that protrude from the underlying shell domain, and contain the immunodominant loop of HBcAg (7, 20, 23). The HBV capsid displays several unique properties. It was shown in the mid-1980s that HBcAg could function as both a T-cell-dependent and a T-cell-independent antigen (16). Subsequently, foreign B-cell epitopes inserted at the tip of the immunodominant loop may induce a T-cell-independent B-cell response (11). It was recently shown that a high frequency of naive B cells were able to bind HBcAg, whereby they became activated and were able to present HBcAg to a specific T-cell hybridoma (15). These data support the notion that HBcAg is a unique B-cell immunogen, although the molecular basis for this has remained unknown. An interesting observation is that during infection, the C gene of HBV often displays genetic deletions within the tip of the protruding spikes of HBcAg, which are known to contain the major site for antibody binding (5, 7). These have been referred to as core internal deletion variants, and they often appear in end stage liver disease (5). Depending on the nature of the deletion, they may still form functional capsids, as determined by electron microscopy (19). This is rather unexpected, since neither B cells nor antibodies to HBcAg, an internal component of the virion, have been considered to be of functional importance for the host (21).

There may be several explanations for these observations. First, the particulate nature of HBcAg may aid in the cross-linking of B-cell surface receptors and in the subsequent activation of B cells (16). Surface immunoglobulin receptor cross-linking is a critical signal for B-cell activation that is often achieved by the binding of structurally ordered viruses with repetitive identical antigens (1). Second, HBcAg might bind to non-HBcAg-specific B cells through an unknown mechanism similar to that of bacterial superantigens (9, 10, 12). If the latter were true, one would expect that the naive B cells that were able to bind and present HBcAg had surface receptors encoding a common motif or restricted in the usage of variable heavy- and light-chain (VH and VL, respectively)-encoding genes.

In the present study, we examined the molecular basis for the binding of HBcAg to naive B cells.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Mice.

Wild-type BALB/c and CBA mice were purchased from BK Universal, Sollentuna, Sweden. The generation of T-cell receptor (TCR)-transgenic (TCR-Tg) mice with T cells specific for HBcAg and HBV envelope antigen (HBeAg) has been described previously (6). The two TCR-Tg lineages used were 11/4-12 (67% transgenic TCRs) and 8/3-11 (11.5% transgenic TCRs). The 11/4-12 lineage preferentially recognizes HBeAg and represents a low-affinity TCR, whereas 8/3-11 preferentially recognizes HBcAg and represents a higher-affinity TCR (6). Splenocyte cultures from these lineages were used to study the presentation and activation of naive B and T cells through HBcAg.

Recombinant antigens.

Recombinant particulate HBcAg encompassing residues 1 to 183 was produced in Escherichia coli as previously described (26). This protein assembles into particles 27 nm in diameter. A truncated recombinant form of HBcAg containing nine residues of the precore and the first 150 residues of HBcAg was designated HBeAg (26). A recombinant HBcAg in which the region including residues 76 to 95 had been replaced with an irrelevant sequence, designated ΔHBcAg, was also used (3). Denatured HBcAg (dHBcAg) was obtained by boiling HBcAg in the presence of mercaptoethanol and sodium dodecyl sulfate. Also, a nonstructural 3 (NS3) protein of the hepatitis C virus (HCV) was used as a recombinant control antigen (13). Traditional anti-HBc monoclonal antibody (MAb) 35/312 has been described in detail previously (20, 22, 23).

Peptide synthesis.

Overlapping peptides (20 amino acids long with a 10-amino-acid overlap) corresponding to the VH and/or VL domains of the MAbs were produced by standard techniques (24) with a multiple-peptide synthesizer using standard 9-fluorenylmethoxy carbonyl chemistry (Syro; MultiSynTech). Additional deletion and alanine substitution analogues of reactive peptides were synthesized by the same technique. In some cases, the peptides were purified by high-performance liquid chromatography using standard protocols (24).

Production of B-cell hybridomas.

To obtain antibodies that represent naive HBcAg-specific B-cell receptors, CBA mice were primed with 50 μg of HBcAg, HBeAg, or HCV NS3 antigen intraperitoneally. Three days later, spleen cells were harvested and fused with SP2/0-Ag14 myeloma cells in accordance with standard procedures. Following three rounds of cloning and screening by enzyme immunoassay (EIA) using the indicated antigens, stable hybridomas secreting antibodies with the desired specificity were selected for antibody production and extraction of mRNA. Hybridoma cell lines were maintained in Dulbecco modified Eagle medium supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum (FCS), 2 mM l-glutamine, 100 U of penicillin per ml, 100 μg of streptomycin per ml, 1 mM nonessential amino acids, 50 μM β-mercaptoethanol, and 1 mM sodium pyruvate (GIBCO-BRL, Gaithersburg, Md.). All cells were grown in a humidified 37°C, 5% CO2 incubator.

Sequence analysis of VH and VL domains.

Total cellular mRNA was extracted by using magnetic beads coated with oligo-dT25 (Dynal AS, Oslo, Norway) as previously described (28). The VH and VL domains of MAbs were amplified from cDNA by PCR using the primer sequences designed for PCR-based cloning of VH and VL regions (14a) and Ig-prime kits (Novagen, Madison, Wis.). The amplified cDNA fragments were directly ligated into the TA cloning vector pCR 2.1 (Invitrogen, San Diego, Calif.) as previously described (28). The DNA sequence was determined by an automated sequencer (ALF Express; Pharmacia, Uppsala, Sweden) as previously described (28).

Identification and characterization of specific MAbs.

HBcAg, HBeAg, or NS3 protein at 10 μg/ml was passively adsorbed onto 96-well microtiter plates in sodium carbonate buffer (pH 9.6) at +4°C overnight. The plates were incubated with MAbs diluted in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) containing 1% bovine albumin, 2% goat serum, and 0.05% Tween 20 (PBS-GT) for 60 min. Bound MAbs were indicated by rabbit anti-mouse immunoglobulin peroxidase conjugate (P260; Dako AS) by incubation for 60 min. The plates were developed with o-phenylenediamine substrate for 30 min, and the reaction was stopped by adding 2 M H2SO4. The optical density (OD) at 490 nm was determined. The immunoglobulin classes, subclasses, and light-chain types of the MAbs were determined with a mouse hybridoma subtyping kit in accordance with the manufacturer's (Boehringer GmbH, Mannheim, Germany) recommendations.

The affinity of HBcAg-binding MAbs was estimated by a competitive inhibition EIA as described previously (20). In brief, microplates were coated with HBcAg at 10 μg/ml. Simultaneously with the addition of MAbs at a predetermined dilution (giving an OD at 490 nm of 0.5 to 1.0), serial twofold dilutions of HBcAg starting at 100 μg/ml were added to the wells. The mixture was incubated on the plates for 1 h, and the amount of MAb bound was determined as described above. The affinity was expressed as the molar concentration of HBcAg that reduced the OD at 490 nm by more than 50% compared to that of the uninhibited control.

Identification and characterization of HBcAg- and HBeAg-binding peptides.

Synthetic peptides corresponding to the VH and VL domains of the sequenced MAbs were passively adsorbed onto 96-well microplates as described above in serial dilutions starting at 200 μg/ml. The peptide-coated plates were incubated with HBcAg and HBeAg serially diluted in PBS-GT. The amounts of HBcAg and HBeAg bound to the peptides were indicated by using a previously characterized MAb to an epitope common to HBcAg and HBeAg (57/8; 4) diluted 1:3,000 in PBS-GT. Bound MAb was indicated by rabbit anti-mouse immunoglobulin–peroxidase conjugate (P0260; Dako AS). The plates were developed by incubation with o-phenylenediamine (Sigma) substrate, the reaction was stopped with 2 M H2SO4, and the OD at 490 nm was determined.

Purification of B and T cells.

To prepare enriched naive B cells, spleens were removed from nonimmune BALB/c mice, disrupted, and depleted of red blood cells by using lysis buffer (Sigma). Cells were suspended in PBS–1% FCS and depleted of T cells by incubation with Dynabeads mouse pan-T (Thy1.2) in accordance with the manufacturer's (Dynal) instructions. Adherent cells were removed by panning on a plastic plate at 37°C for 60 min. The resulting B-cell population was >85% singly positive for B220 as determined by flow cytometry.

To obtain HBcAg-specific T cells, BALB/c mice were immunized at the base of the tail with 20 μg of HBcAg emulsified in complete Freund adjuvant. Ten days later, peripheral draining lymph nodes were collected. Lymph nodes were mechanically disrupted, and B cells were depleted by incubation with Dynabeads mouse pan-B (B220) in accordance with the manufacturer's (Dynal) instructions. Macrophages were removed by adherence to the plastic plate at 37°C for 60 min. The resulting T-cell population was >90% positive for CD3 as determined by flow cytometry.

Antigen presentation of HBcAg by naive B cells to primed T cells.

Enriched naive B cells from BALB/c mice (3 × 105 cells per well) were cocultured with enriched T cells from HBcAg-primed BALB/c mice (5 × 105 cells per well) in multiple wells of a 96-well cell culture plate. The total volume of each culture was 200 μl. Decreasing concentrations of HBcAg were included starting at 20 μg/ml and following a series of fivefold dilutions. Each sample was run in triplicate. Control wells included cells incubated with phytohemagglutinin at a final concentration of 1 μg/ml and wells with no antigen stimulation. To evaluate possible background proliferation, both enriched naive B cells (3 × 105 cells per well) and primed enriched T cells (5 × 105 cells per well) were cultured alone in the absence or presence of serially diluted HBcAg. Cell culture supernatants were collected at 24 and 48 h to measure cytokine production. Cell proliferation was measured by adding 1 μCi of [3H]thymidine (TdR; Amersham) at 72 h. After 16 to 20 h of incubation, cells were harvested onto cellulose filters. Filters were quenched, and TdR incorporation was measured by a liquid scintillation β counter.

Inhibition of HBcAg presentation by MAbs.

Purified primed T cells (5 × 105 cells per well) and naive B cells (3 × 105 cells per well) were cultured in multiple wells of a 96-well cell culture plate as described earlier. MAbs 9C8, 5H7, and 4-2 were added in serial fivefold dilutions starting at 1:5, along with HBcAg at a final concentration of 10 μg/ml. All MAbs were affinity purified from cell culture supernatants on protein A-Sepharose (Sigma) or anti-mouse immunoglobulin M (IgM; μ chain specific) agarose affinity columns in accordance with the manufacturer's (Sigma) instructions. The control wells included cells incubated with either antibody alone or antibody with phytohemagglutinin at a final concentration of 1 μg/ml. Cell proliferation was measured by adding 1 μCi of TdR (Amersham) at 72 h, following by incubation for 16 to 20 h and harvesting onto cellulose filters. Filters were quenched, and TdR incorporation was measured by using a liquid scintillation β counter.

Flow cytometric determination of the frequency of B7-2+ B cells after culture with HBcAg.

Spleen cells from naive mice were depleted of T cells by a 1:1:1 ratio of supernatants from hybridomas 31M (anti-CD8), RL172.4 (anti-CD4), and AT83 (anti-Thy1.2) plus low-toxicity rabbit complement (kindly provided by Eva Severinsson and Lena Ström, CMB, Karolinska Institutet). A total of 2.5 × 106 T-cell-depleted cells per ml were then cultured in RPMI medium containing 10% FCS and 0.05 mM 2-mercaptoethanol for 48 h without antigen, with HBcAg at 10 μg/ml, or with lipopolysaccharide (Sigma) at 10 μg/ml. After 48 h, cells were harvested and washed in PBS containing 1% FCS and then preincubated with Fc-block (2.4G2; Pharmingen, San Diego, Calif.). Thereafter, cells were stained with CyChrome-conjugated B220 antibody and phycoerythrin-conjugated B7-2 antibody (Pharmingen) in accordance with the standard staining protocol. Data were acquired on a FACScan flow cytometer (Becton Dickinson, Mountain View, Calif.) by using CellQuest software.

Flow cytometric determination of the frequency of naive B cells able to bind HBcAg.

A total of 0.5 × 106 T-cell-depleted spleen cells were incubated for 30 min at +4°C without antigen or with 0.5 μg of HBcAg or control antigen NS3. Cells were then extensively washed and incubated with Fc-block (2.4G2) for 20 min at +4°C. Cells were then washed and incubated with sulfo-NHS-LC-Biotin (Pierce, Rockford, Ill.)-labeled HBcAg-specific antibody 35/312 (24). Fluorescein isothiocyanate-conjugated streptavidin (Dako) was used as the second-step reagent together with CyChrome-conjugated B220 antibody. Data were acquired on a FACScan flow cytometer and analyzed with CellQuest software.

RESULTS

Naive B cells produce HBcAg-binding IgM when cultured with HBcAg- or HBeAg-specific naive CD4+ T cells.

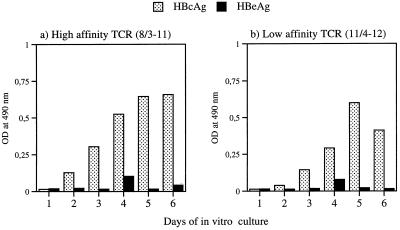

The ability of naive B cells to produce HBcAg-binding IgM when cultured with naive HBcAg- or HBeAg-specific CD4+ T cells was tested in vitro. We recently showed that high in vitro concentrations (>1 μg/ml) of T-cell-dependent HBeAg could induce anti-HBe IgM production in splenocytes from HBcAg- or HBeAg-specific TCR-Tg mice (6). Herein, the effect of a low concentration (0.0016 μg/ml) of HBcAg or HBeAg on in vitro IgM production in Tg mice expressing TCRs specific for HBcAg and HBeAg was determined. In splenocytes from TCR-Tg mice expressing a high- or low-affinity TCR for HBcAg, anti-HBc IgM was detected as early as 2 days and peaked at 5 days of in vitro culture (Fig. 1). Thus, low concentrations of HBcAg were sufficient to allow naive B cells and naive T cells to collaborate, resulting in IgM production in vitro. In contrast, low concentrations of HBeAg were unable to prime anti-HBe production in vitro despite the presence of specific CD4+ T cells that preferentially recognize HBeAg over HBcAg (TCR-Tg 11/4 12; Fig. 1). This confirms the unique ability of limiting concentrations of HBcAg, as opposed to its nonparticulate homologue HBeAg, to elicit IgM production in primary in vitro cultures.

FIG. 1.

In vitro priming of anti-HBc IgM production in naive TCR-Tg mouse splenocyte cultures by HBcAg and HBeAg. A low concentration (0.0016 μg/ml) of HBcAg or HBeAg was added to naive splenocyte cultures, which were incubated for 6 days. Supernatants were removed daily, and anti-HBc IgM was determined by EIA. In splenocytes from TCR-Tg mice, T cells preferentially recognize HBcAg (8/8-11; a) or HBeAg (11/4-12; b; reference 6).

Frequency of HBcAg-binding B cells in a naive mouse spleen.

The frequency of HBcAg-binding B cells in a naive spleen was estimated by three approaches. First, to obtain B-cell hybridomas as naive as possible, fusion of spleen cells was performed 3 days after a single immunization to avoid a massive clonal expansion of specific B cells. The procedure was repeated in three separate experiments. In the following text, the results from one representative experiment are given in which we were able to obtain antibody-producing hybridomas at a surprisingly high frequency. After fusion of HBcAg-immunized mouse spleens, 77 (8%) out of 940 wells produced detectable antibodies to HBcAg (anti-HBc) whereas 7 (0.7%) produced detectable anti-HCV NS3. In contrast, after fusion of HCV NS3-immunized mouse spleens, 39 (4%) out of 940 wells produced detectable anti-HBc whereas 17 (2%) produced detectable anti-HCV NS3. Thus, by this B-cell hybridoma method, it was estimated that at least 4% of the B cells in an HBcAg-naive spleen (i.e., immunized with HCV NS3) can bind HBcAg.

Second, it has been demonstrated that naive B cells cultured with HBcAg for 48 h have an increased level of B7-2 mRNA expression (15). Here we quantified, by flow cytometry, the frequency of B cells that express B7-2 molecules on the cell surface after 48 h of culture with HBcAg at 5 μg/ml. The cells were doubly stained with the B-cell marker B220 and an antibody against B7-2. With this approach, approximately 8% of the B cells in a naive spleen express B7-2 on their surface after culture with HBcAg (Fig. 2).

FIG. 2.

Determination of the frequency of naive HBcAg-binding B cells by fluorescence-activated cell sorter using direct binding of HBcAg (a to c) and by B7-2 induction after 48 h of in vitro culture (d). Purified B cells were incubated on ice with HBcAg (a), medium alone (b), or NS3 (c), and the cells were then doubly stained by the B-cell marker B220 and HBcAg-specific MAb 35/312. The labeling antibodies are indicated on the x and y axes. For panel d, purified B cells were incubated for 48 h with HBcAg, medium alone, or lipopolysaccharide (LPS) and then doubly stained with B220 and a MAb to B7-2. In panel d, the values are the mean percentages of cells expressing B220 and B7-2.

Third, to avoid the induction of B7-2 by unknown contaminants in the HBcAg preparation, the number of B cells able to bind HBcAg was estimated directly. T-cell-depleted naive spleen cells were incubated with HBcAg on ice to prevent endocytosis (see Materials and Methods) and were doubly stained with biotinylated HBcAg-specific MAb 35/312 and B-cell marker B220. The percentage of B cells that were recognized by the HBcAg-specific antibody was approximately 7% (Fig. 2). Cells stained with the biotinylated 35/312 MAb and incubated without HBcAg or with an irrelevant protein, NS3, resulted in a background staining of approximately 2%.

Collectively, by three independent techniques, the percentage of HBcAg binding B cells in a naive mouse spleen was estimated to be in the range of 4 to 8%. This high frequency supports the hypothesis that HBcAg can bind B cells through a common motif or receptors encoded by particular germ line genes.

Characterization of MAbs 9C8 and 5H7.

HBcAg-binding MAbs 9C8 and 5H7, obtained 3 days after a single immunization with HBcAg, were further characterized with respect to their reactivity pattern. IgM MAbs 9C8 and 5H7 recognized particulate HBcAg but not ΔHBcAg, dHBcAg, or HBeAg (Fig. 3). Consistent with this, MAbs 9C8 and 5H7 did not recognize any linear synthetic peptide spanning the HBcAg sequence (data not shown). Thus, the MAbs recognize an epitope unique to particulate HBcAg and neighboring, or containing, the region from position 76 to position 85 at the tips of the spikes of HBcAg (7). Importantly, none of the MAbs were able to compete with polyclonal anti-HBc in commercial assays (Abbott; data not shown) or with anti-HBe (Abbott and Behringwerke; data not shown). The affinity of the two MAbs was estimated by competitive inhibition with HBcAg in a solution in which the concentration of HBcAg inhibiting the reactivity of the MAb by 50% was taken as the affinity value. The affinities, estimated in parallel, of MAbs 9C8, 5H7, and 35/312 were 0.42, 263, and 0.0006 pmol. Thus, MAbs 9C8 and 5H7 had 700- to 105-fold lower affinities than the traditional 35/312 anti-HBc MAb. Collectively, IgM MAbs 9C8 and 5H7 recognize only particulate HBcAg and have very low affinity constants. This further supports the notion that MAbs 9C8 and 5H7 are good representatives of the IgM receptor on naive B cells that bind HBcAg.

FIG. 3.

Reactivities of four HBcAg-binding MAbs with HBcAg, ΔHBcAg, dHBcAg, and HBeAg when used as solid-phase antigens in an EIA. Microplates coated with the indicated antigens were incubated with serial dilutions of the respective MAbs, and the amounts of the MAbs bound were determined as described in Materials and Methods. The values shown are the endpoint titers (dilution giving twice the OD at 490 nm of the negative control) of the MAbs with the different solid-phase antigens.

Two additional MAbs were produced by the standard hyperimmunization procedure. These were found to recognize HBcAg, but both preferentially recognized dHBcAg (4-2) or HBeAg (3-4; Fig. 3).

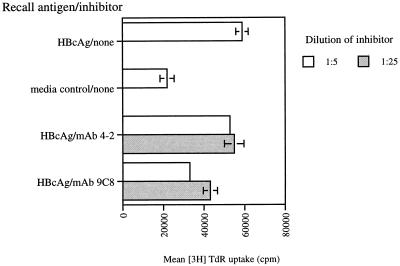

Inhibition of antigen presentation of HBcAg by naive B cells to HBcAg-primed CD4+ T cells.

The ability of three MAbs to inhibit antigen presentation by naive B cells was tested in several experiments. In general, groups of BALB/c mice were immunized with HBcAg and 9 days later, the lymph nodes were harvested and CD4+ T cells were isolated. The purified CD4+ T cells from immunized mice were cocultured with purified B cells from naive mice in the presence of HBcAg and different MAbs as inhibitors. As shown in one representative experiment, HBcAg-binding MAbs 9C8 and 5H7 significantly blocked the presentation of HBcAg by naive B cells whereas control MAb 4-2 did not (Fig. 4). Thus, HBcAg-binding MAbs 9C8 and 5H7, derived from mice 3 days after a single immunization with HBcAg, were able to block the presentation of HBcAg by naive B cells to primed CD4+ T cells. The data confirm that these MAbs should be representative of the surface immunoglobulin receptors present on HBcAg-binding B cells present at a high frequency in naive animals.

FIG. 4.

Inhibition of HBcAg presentation by naive B cells to specific T cells by MAbs in vitro. Purified naive B cells were cocultured for 96 h with purified specific T cells in the presence of HBcAg with or without MAbs 9C8 and 4-2. After 72 h, TdR was added and 24 h later, the amount of radioactivity incorporated was determined with a β counter. The values shown are the mean absolute counts per minute ± the standard deviation of triplicate determinations.

Sequence analysis of the VH and VL domains from HBcAg-binding B cells.

Seven VH sequences were obtained from B-cell hybridomas producing immunoglobulin that bound to HBcAg. These hybridomas were all made 3 days after a single immunization with HBcAg. The sequences were analyzed by using the International ImMunoGeneTics database (http://imgt.cnusc.fr: 8104/) for determination of murine V gene usage and by using the Vbase database (http://www.mrc-cpe.cam.ac.uk/imt-doc/public/INTRO.html) for homologies with human V gene families. Out of the seven hybridomas, six (including 9C8) were encoded by the murine VH1-encoding gene family (Table 1). One hybridoma (5H7) was encoded by the murine VH3-encoding gene family. The light chain from VH3-expressing hybridoma 5H7 was sequenced and found to be encoded by the VκV-encoding gene family. These data suggest that the heavy chains of close-to-naive B cells secreting IgM that can bind HBcAg have restricted V gene usage.

TABLE 1.

Alignment of the VH domains of nine sequenced HBcAg-binding hybridomas

| Hybridoma | V gene usagea | Difference from consensus sequence:

|

|---|---|---|

| FR1---------------------->CDR1-----FR2------------->CDR2----->FR3------------------------------------->CDR3 V.LQESGTEV VKPGASVKLS CKASGYIFTS YDIDWVRQTP EQGLEWIGWI FPGEGSTEYN EKFKGRATLS VDKSSSTAYM ELTRLTSEDS AVYFCARGDY YRRYFDLWGQ GTTVTVSS-- | ||

| Single immunization | ||

| 9C8 | VH1 | IQ..Q..A.L ........I. ......S..G .NMN..K.SH GKS.....N. N.YY...S.. Q....K...T .......... Q.NS...... ...Y....KG .---..Y... ..L....AAK |

| 8G2-3 | VH1 | .Q........ .......... .......... .......... .......... .......... .......... .......... .......... .......... .W........ .......... |

| 2A3-1 | VH1 | .K..X..... .......... .......... .......... .......... .......... .......... .......... .......... .......... .......... .......-.. |

| 3F2 | VH1 | .K........ .......... .......... .......... .......... .......... .......... .......... .......... .......... .......... ......--.. |

| 3C7 | VH1 | .K........ .......... .......... .......R.. .......... .......... .......... .......... .......... ....R..... .......... .......... |

| 7C4 | VH1 | .Q.....GGL ....G.L... .A...FA.S. ..MS...... .KR...VAY. SS.G...Y.P DTV...F.I. R.NAKN.L.L QMSS.K...T .M.Y...QRD FDEFYAM--- -GLLGAK-.. |

| 5H7-1 | VH3 | .K.....PGL ...SQ.LS.T .SVT..SI.. GYYWNWIRQF PGNKLEWMGY I-SYDGSNNY NPSLKNRISI TRDT.KNQFF LKLNSVTTED TATYYCARTD .---..Y... .......... |

| Hyperimmunization | ||

| 3-4-1 | VH1 | .K.....A.L .R......I. ...F..T..N HH.N.MK.R. G...D...Y. N.YNDY.N.. Q....K...T .......... ..SS...... ...Y..K.-- TG--.AY... .......... |

| 4-2-1 | VH1 | .K..Q..... .......... .......... .......... .......... .......... .......... .......... .......... .......... .......... .......... |

V gene allele usage and locations of FR and CDR regions are according to the international ImMunoGeneTics database (http://imgt.cines.fr:8104; initiator and coordinator, Marie-Paule Lefranc, Montpellier, France).

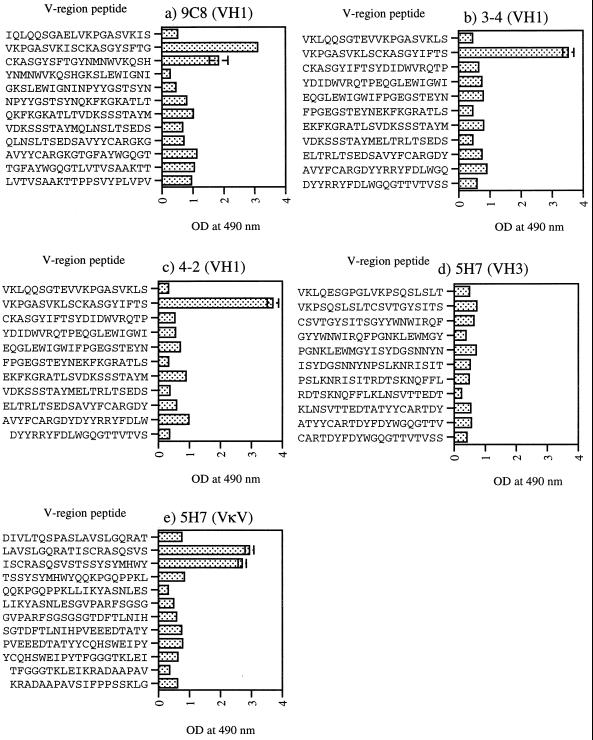

Scanning of the VH1-encoding gene sequence peptides for a sequence that binds HBcAg.

To determine whether the murine VH1- and VH3-encoding gene families encoded a linear HBcAg-specific binding motif, overlapping peptides corresponding to a total of four MAbs were produced. The solid-phase-bound VH1- and VH3-encoding gene peptides were tested for binding to HBcAg and HCV NS3 by EIA (Fig. 5). Interestingly, HBcAg was found to bind to peptides corresponding to the FR1-CDR1 junction of VH1-expressing hybridomas (9C8, 3-4, and 4-2; Figure 5). Thus, a motif common to all three of these VH1-encoding genes was the I/LSCKASGYI/SFTS/G sequence at the FR1-CDR1 junction.

FIG. 5.

HBcAg binding of solid-phase-bound peptides corresponding to VH1 MAbs (a to c), a VH3 MAb (d), and a VκV light chain (e). Microplates were coated with 100 μg of peptide per ml and then incubated with HBcAg. The amount of HBcAg bound was indicated by the 57/8 MAb as described in Materials and Methods. The values shown are the mean OD at 490 nm ± the standard deviation of triplicate determinations.

None of the peptides encoded by the VH3 gene of MAb 5H7 was found to bind HBcAg (Fig. 5). We therefore synthesized and tested peptides corresponding to the VLκV chain of MAb 5H7. Overlapping peptides at the FR1-CDR1 junction of the VLκV sequence were found to bind HBcAg, similar to the VH1 peptides. Interestingly, these peptides contained a motif similar to the I/LSCKASGYI/SFTS/G sequence of the VH1 domain. The VLκV motif contained the sequence ISCRASQVSTSS, which has a direct sequence homology of 58%. However, considering highly similar amino acids, i.e., K and R, T and S, the motif homology is 75%. This suggests that an HBcAg-binding motif may be present in either the VH or the VL domain of the antibody.

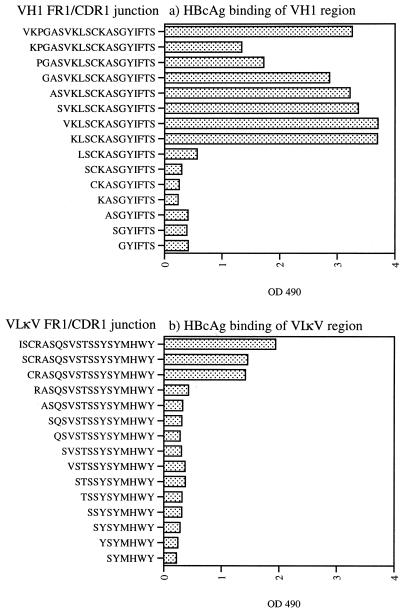

Mapping of the binding domain by deletion analogue peptides.

To further test whether the binding of HBcAg was related to the suspected I/LSCKASGYI/SFTS/G and ISCRASQVSTSS sequences, amino-terminal deletion analogues corresponding to VH1 and VLκV sequences were produced. Interestingly, amino acids N terminal to the KLSCKASGYIFTS sequence could be deleted with retained reactivity to HBcAg (Fig. 6). This sequence may represent the minimal HBcAg-binding sequence and contains the suggested I/LSCKASGYI/SFTS/G motif. With respect to the VLκV sequence, a sequence containing the CRASQSVSTSSYSYMHWY sequence was identified, further implicating the suggested motif in the binding of HBcAg (Fig. 6).

FIG. 6.

Fine mapping, by using N-terminal deletion analogue peptides, of the HBcAg-binding activity of the VH1-derived domain (a) and of the VκV-derived domain (b) with solid-phase-bound peptides. Microplates were coated with 100 μg of peptide per ml and then incubated with HBcAg. The amount of HBcAg bound was indicated by the 57/8 MAb as described in Materials and Methods. The values shown are the ODs at 490 nm.

As an alternative approach to mapping by solid-phase-bound peptides, the deletion analogues were tested for competition with a VH1-encoded MAb for binding to HBcAg. The results of the competitive EIA were identical to the analysis with the peptides on a solid phase (data not shown), confirming the validity of the results.

The Cys residue at position 3 in the I/LSCKASGYI/SFTS/G motif is present in all VH-encoding gene families, and we therefore tested whether that is a critical residue for HBcAg binding. Peptide analogues of VH1 sequence VKLSCKASGYIFTS in which the Cys was replaced with an amino acid that had a minimal (Ala), sulfur-containing (Met), acidic (Glu), or basic (Lys) side chain were produced. Only replacement of the Cys with Glu abolished the HBcAg-binding activity of the VH1 peptides (data not shown), suggesting that the Cys residue present in all VH-encoding gene families is not highly essential for interaction with HBcAg.

Restriction of HBcAg binding to the human VH1- and VH7-encoding gene families.

To test whether the binding of HBcAg is restricted to the murine VH1-encoding gene family, peptides corresponding to the reactive FR1-CDR1 domain were produced from human germ line VH1- to VH7-encoding gene sequences. In solid-phase EIAs, only the peptides corresponding to the human VH1- and VH7-encoding germ line gene families were found to bind HBcAg (Table 2). Interestingly, this domain is identical in both the VH1- and VH7-encoding gene families. Thus, the HBcAg binding of this linear sequence seems to be restricted to the murine VH1-encoding and human VH1- and VH7-encoding gene families. However, this does not exclude the possibility that other motifs in other VH or VL regions of additional V gene families bind HBcAg

TABLE 2.

Alignment of human VH peptides within the FR1-CDR1 junction and their reactivity with HBcAg in an EIAa

| V gene | Peptide sequence (FR1→CDR1) | % Homology | Reactivity with HBcAg (S/N)b |

|---|---|---|---|

| VH1 | KKPGASVKVSCKASGYTFT S | 100 | 6.8 |

| 4-2 | V-------L-------I-- - | 85 | 8.4 |

| VH2 | V--TQTLTLT-TF--FSLS T | 25 | 1.2 |

| VH3 | VQ--G-LRL--A---F--S - | 55 | 0.9 |

| VH4 | V--SGTLSLT-AV--GSIS - | 30 | 1.7 |

| VH5 | ----E-L-I---G---S-- - | 75 | 2.8 |

| VH6 | V--SQTLSLT-AI--DSVS - | 30 | 0.7 |

| VH7 | ------------------- - | 100 | 6.8 |

Microplates were coated with the respective peptides at 100 μg/ml and then incubated with 5 μg of HBcAg per ml. Bound HBcAg was then detected as described in Materials and Methods.

S/N is the sample OD at 492 nm divided by the mean OD at 405 nm of the negative controls. An S/N value of ≥3.0 indicates reactivity.

DISCUSSION

It is well known that HBcAg is extremely immunogenic in most hosts and primes humoral and CD4+ and CD8+ T-cell responses in mice (14, 17, 25, 27). This has been partly attributed to the particulate nature of the protein and its ability to activate B cells by a T-cell-independent pathway (16). It was recently shown that HBcAg has the ability to bind naive murine B cells (15). In a companion paper, we report that this is also true for human B cells (4). Such a finding suggests that the interaction between HBcAg and the naive B-cell receptor may differ from traditional antigen-antibody interactions. One explanation might be that HBcAg has the ability to bind a sequence restricted to a particular germ line V gene family, similar to proposed B-cell superantigens (9, 10). This hypothesis was tested in the present study.

We could show that low concentrations of HBcAg, but not its nonparticulate homologue HBeAg, were sufficient to allow naive B cells and naive T cells to collaborate in in vitro IgM antibody production. Importantly, even in the presence of TCR-Tg T cells that preferentially recognize HBeAg over HBcAg, only low concentrations of HBcAg, but not HBeAg, primed in vitro IgM antibody production within 2 days. Thus, the activation of naive B cells by HBcAg, as shown previously (15) and herein, by the induction of B7-2 appears to be sufficient to activate naive TCR-Tg CD4+ T cells. However, T-cell activation by non-B-cell antigen-presenting cells cannot be ruled out. This confirms that HBcAg-binding B cells are present at high precursor frequencies in naive murine spleens. Consistent with this, HBcAg-binding hybridomas were easily obtained by immunization with a totally irrelevant antigen. Thus, such hybridomas should not be designated HBcAg specific, or anti-HBc producing, in the traditional sense. By our estimates, HBcAg-binding B cells constitute 4 to 8% of the splenic B-cell population. This strongly suggests that a restricted set of heavy- or light-chain V gene families may mediate the binding of HBcAg by naive B cells. Fully consistent with this, we did observe that adoptive transfer of naive human B cells together with HBcAg in immunodeficient mice immediately primed the production of anti-HBc IgM (4). Thus, a similar situation most likely also applies to human B cells.

We were able to obtain low-affinity HBcAg-binding IgM MAbs that bound particulate HBcAg. These MAbs did not bind HBeAg or denatured HBcAg and did not recognize particulate HBcAg with an insertion in the tips of the spikes at positions 76 to 85. Additionally, the MAbs blocked the binding and antigen presentation of HBcAg by naive B cells to specific T cells. Consequently, these results suggest that these MAbs represent the surface receptor of the repertoire of naive B cells that bind HBcAg.

Interestingly, 86% of the sequenced VH domains obtained from hybridomas that bound HBcAg corresponded to the murine and human VH1-encoding gene families. When linear synthetic peptides corresponding to VH1-expressing hybridomas were produced, we could identify a linear sequence responsible for the HBcAg-binding activity. The specificity of this observation was confirmed by producing human VH1- to VH7-derived peptides spanning the same region, and only those containing the proposed sequence, i.e., VH1 and VH7, were able to bind HBcAg. Furthermore, none of the overlapping peptides from the HBcAg-binding 5H7 MAb encoded by the VH3-encoding gene family bound HBcAg. However, HBcAg-binding activity was identified in the VL domain of the 5H7 MAb. Thus, the HBcAg-binding motif may also be present in light-chain sequences. HBcAg can bind directly to naive B cells expressing surface receptors encoded by the murine and human VH1-encoding gene families (or possibly the human VH7-encoding gene family), or the VLκV-encoding gene family, through a linear motif present in the FR1-CDR1 junction. By this interaction, HBcAg can cross-link several surface receptors and the naive B cell becomes activated, as evidenced by increased surface expression of B7-2. Subsequently, the now-activated B cell becomes a highly efficient antigen-presenting cell that can effectively assist in the presentation of HBcAg to CD4+ T cells.

A major question still remains: does HBV benefit by targeting HBcAg to B cells? Effective priming of HBcAg- and HBeAg-specific CD4+ T cells through activated B cells acting as antigen-presenting cells is unlikely to ensure the persistence of HBV in the host. However, there may be other events that are beneficial for HBV persistence that are maintained by B cells as antigen-presenting cells. One explanation may be that the B-cell uptake of either HBcAg alone, or capsids containing infectious HBV genomes (18), allows leakage between the class I and II antigen-presenting pathways within the B cell. If so, it is possible that these HBcAg-binding B cells expressing HBcAg peptides in both class I and II molecules impair the cytotoxic T lymphocyte response, since B cells loaded with class I peptides have been reported to downregulate a cytotoxic T-lymphocyte response in vivo (2). This deserves further study.

In conclusion, the molecular basis of HBcAg binding to a high frequency of naive murine B cells is explained by the ability of a linear motif expressed by some VH- and VL-encoding gene families to directly bind HBcAg. This helps to explain the enhanced immunogenicity of HBcAg, but the relevance to the persistence of HBV in the infected host remains unclear. Also, it is important to determine if similar molecular mechanisms apply to naive human B cells that bind HBcAg (4). Finally, the targeting of HBcAg to B cells may offer therapeutic uses for HBcAg as a delivery vehicle for B cells.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This study was supported by grant 3825-B99-04XAC from the Cancer Foundation and by Tripep AB.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bachmann M F, Kopf M. The role of B cells in acute and chronic infections. Curr Opin Immunol. 1999;11:332–339. doi: 10.1016/s0952-7915(99)80053-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bennett S R, Carbone F R, Toy T, Miller J F, Heath W R. B cells directly tolerize CD8+ T cells. J Exp Med. 1998;188:1977–1983. doi: 10.1084/jem.188.11.1977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Borisova G, Borschukova O, Skrastina D, Dislers A, Ose V, Pumpens P, Grens E. Behavior of a short preS1 epitope on the surface of hepatitis B core particles. Biol Chem. 1999;380:315–324. doi: 10.1515/BC.1999.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cao T, Lazdina U, Desombere I, Vanlandschoot P, Milich D R, Sällberg M, Leroux-Roels G. Hepatitis B virus core antigen binds and activates naive human B cells in vivo: studies with a human PBL-NOD/SCID mouse model. J Virol. 2001;75:6359–6366. doi: 10.1128/JVI.75.14.6359-6366.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Carman W F, Boner W, Fattovich G, Colman K, Dornan E S, Thursz M, Hadziyannis S. Hepatitis B virus core protein mutations are concentrated in B cell epitopes in progressive disease and in T helper cell epitopes during clinical remission. J Infect Dis. 1997;175:1093–1100. doi: 10.1086/516447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chen M, Sällberg M, Thung S N, Hughes J, Jones J, Milich D R. Nondeletional T-cell receptor transgenic mice: model for the CD4+ T-cell repertoire in chronic hepatitis B virus infection. J Virol. 2000;74:7587–7599. doi: 10.1128/jvi.74.16.7587-7599.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Conway J F, Cheng N, Zlotnick A, Stahl S J, Wingfield P T, Belnap D M, Kanngiesser U, Noah M, Steven A C. Hepatitis B virus capsid: localization of the putative immunodominant loop (residues 78 to 83) on the capsid surface, and implications for the distinction between c and e-antigens. J Mol Biol. 1998;279:1111–1121. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1998.1845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Crowther R A, Kiselev N A, Bšttcher B, Berriman J A, Borisova G P, Ose V, Pumpens P. Three-dimensional structure of hepatitis B virus core particles determined by electron cryomicroscopy. Cell. 1994;77:943–950. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90142-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Domiati-Saad R, Attrep J F, Brezinschek H P, Cherrie A H, Karp D R, Lipsky P E. Staphylococcal enterotoxin D functions as a human B cell superantigen by rescuing VH4-expressing B cells from apoptosis. J Immunol. 1996;156:3608–3620. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Domiati-Saad R, Lipsky P E. Staphylococcal enterotoxin A induces survival of VH3-expressing human B cells by binding to the VH region with low affinity. J Immunol. 1998;161:1257–1266. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fehr T, Skrastina D, Pumpens P, Zinkernagel R M. T cell-independent type I antibody response against B cell epitopes expressed repetitively on recombinant virus particles. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:9477–9481. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.16.9477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Graille M, Stura E A, Corper A L, Sutton B J, Taussig M J, Charbonnier J B, Silverman G J. Crystal structure of a Staphylococcus aureus protein A domain complexed with the Fab fragment of a human IgM antibody: structural basis for recognition of B-cell receptors and superantigen activity. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:5399–5404. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.10.5399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jin L, Peterson D L. Expression, isolation, and characterization of the hepatitis C virus ATPase/RNA helicase. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1995;323:47–53. doi: 10.1006/abbi.1995.0008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kuhober A, Pudollek H P, Reifenberg K, Chisari F V, Schlicht H J, Reimann J, Schirmbeck R. DNA immunization induces antibody and cytotoxic T cell responses to hepatitis B core antigen in H-2b mice. J Immunol. 1996;156:3687–3695. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14a.Margulies M. Antibody detection and preparation. In: Coico R, et al., editors. Current protocols in immunology. New York, N.Y: John Wiley & Sons; 1996. pp. 2.0.1–2.12.15. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Milich D R, Chen M, Schödel F, Peterson D L, Jones J E, Hughes J L. Role of B cells in antigen presentation of the hepatitis B core. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:14648–14653. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.26.14648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Milich D R, McLachlan A. The nucleocapsid of hepatitis B virus is both a T-cell-independent and a T-cell-dependent antigen. Science. 1986;234:1398–1401. doi: 10.1126/science.3491425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Milich D R, McLachlan A, Stahl S, Wingfield P, Thornton G B, Hughes J L, Jones J E. Comparative immunogenicity of hepatitis B virus core and E antigens. J Immunol. 1988;141:3617–3624. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pasquetto V, Wieland S, Chisari F V. Intracellular hepatitis B virus nucleocapsids survive cytotoxic T-lymphocyte-induced apoptosis. J Virol. 2000;74:9792–9796. doi: 10.1128/jvi.74.20.9792-9796.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Preikschat P, Borisova G, Borschukova O, Dislers A, Mezule G, Grens E, Kruger D H, Pumpens P, Meisel H. Expression, assembly competence and antigenic properties of hepatitis B virus core gene deletion variants from infected liver cells. J Gen Virol. 1999;80:1777–1788. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-80-7-1777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pushko P, Sällberg M, Borisova G, Ruden U, Bichko V, Wahren B, Pumpens P, Magnius L. Identification of hepatitis B virus core protein regions exposed or internalized at the surface of HBcAg particles by scanning with monoclonal antibodies. Virology. 1994;202:912–920. doi: 10.1006/viro.1994.1413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sällberg M, Hultgren C. Mutations and deletions within the hepatitis B virus core antigen and locations of B cell recognition sites. J Infect Dis. 1998;177:264–265. doi: 10.1086/513810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sällberg M, Pushko P, Berzinsh I, Bichko V, Sillekens P, Noah M, Pumpens P, Grens E, Wahren B, Magnius L O. Immunochemical structure of the carboxy-terminal part of hepatitis B e antigen: identification of internal and surface-exposed sequences. J Gen Virol. 1993;74:1335–1340. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-74-7-1335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sällberg M, Ruden U, Magnius L O, Harthus H P, Noah M, Wahren B. Characterisation of a linear binding site for a monoclonal antibody to hepatitis B core antigen. J Med Virol. 1991;33:248–252. doi: 10.1002/jmv.1890330407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sällberg M, Ruden U, Magnius L O, Norrby E, Wahren B. Rapid “tea-bag” peptide synthesis using 9-fluorenylmethoxycarbonyl (Fmoc) protected amino acids applied for antigenic mapping of viral proteins. Immunol Lett. 1991;30:59–68. doi: 10.1016/0165-2478(91)90090-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sällberg M, Townsend K, Chen M, O'Dea J, Banks T, Jolly D J, Chang S M, Lee W T, Milich D R. Characterization of humoral and CD4+ cellular responses after genetic immunization with retroviral vectors expressing different forms of the hepatitis B virus core and e antigens. J Virol. 1997;71:5295–5303. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.7.5295-5303.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Schödel F, Peterson D, Zheng J, Jones J E, Hughes J L, Milich D R. Structure of hepatitis B virus core and e-antigen. A single precore amino acid prevents nucleocapsid assembly. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:1332–1337. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Townsend K, Sällberg M, O'Dea J, Banks T, Driver D, Sauter S, Chang S M, Jolly D J, Mento S J, Milich D R, Lee W T. Characterization of CD8+ cytolytic responses after genetic immunization with retroviral vectors expressing different forms of the hepatitis B virus core and e antigens. J Virol. 1997;71:3365–3374. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.5.3365-3374.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zhang Z X, Lazdina U, Chen M, Peterson D L, Sällberg M. Characterization of a monoclonal antibody and its single-chain antibody fragment recognizing the nucleoside triphosphatase/helicase domain of the hepatitis C virus nonstructural 3 protein. Clin Diagn Lab Immunol. 2000;7:58–63. doi: 10.1128/cdli.7.1.58-63.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]