To the Editor:

Somatic mutation in the ubiquitin-activating enzyme E1 gene UBA1 is a key biomarker of VEXAS (vacuoles, E1-enzyme, X-linked auto-inflammatory, somatic) [1]. UBA1 mutations were recently also detected in myelodysplastic neoplasm (MDS) [2]. Of note, the most frequent UBA1 variants in VEXAS and MDS lead to reduced UBA1 proteins [3]. To investigate whether RNA expression of UBA1 is also reduced in MDS, we analyzed a transcriptomic dataset generated by bulk RNA-sequencing (RNA-seq) in CD34+ bone marrow hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells (BM HSPCs) in MDS and chronic myelomonocytic leukemia (CMML) (n = 72, 29 MDS with excess blasts 〈EB〉, 22 MDS with low blasts 〈LB〉, and 21 CMML, Supplementary Table 1) [4]. Because UBA1 is an X-chromosomal gene escaping X-inactivation in female individuals [5], all healthy donors (HD; n = 12) and patients were male.

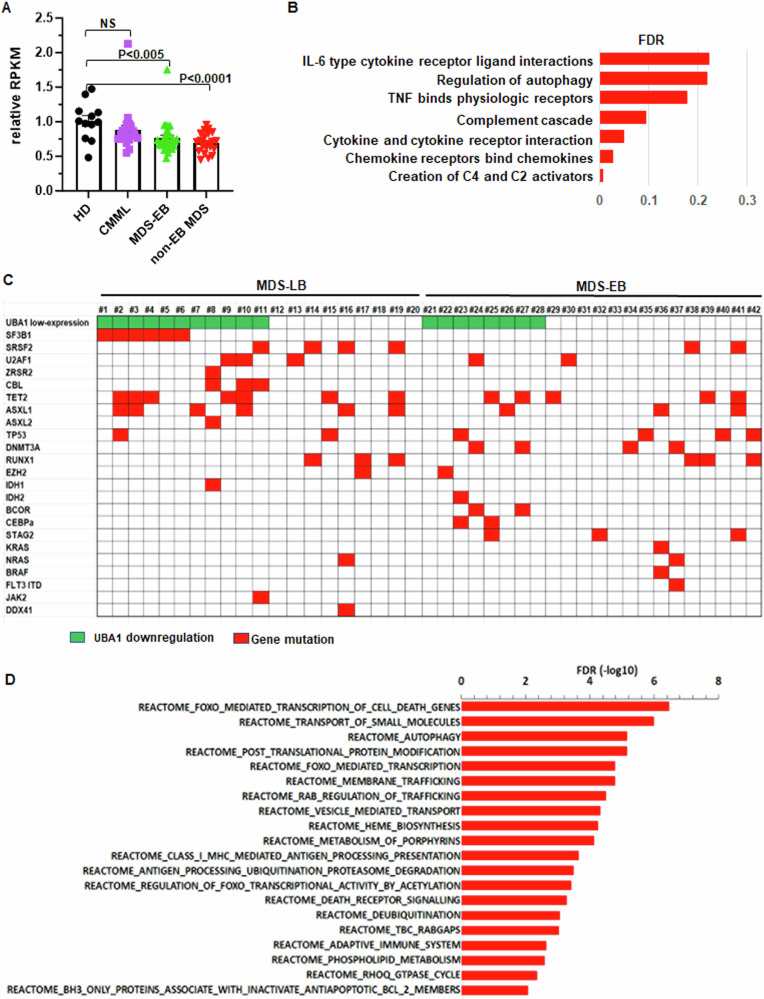

RNA-Seq indicated that, compared to HD, UBA1 RNA level in BM HSPCs was moderately decreased in MDS-EB (75% ±8%, P < 0.005) and MDS-LB (70% ±7%, P < 0.0001; Fig. 1A), but not in CMML (P = 0.22; Fig. 1A). Using an antibody that detects both UBA1a and UBA1b [3], we confirmed lower UBA1 protein levels, particularly UBA1a, in BM mononuclear cells (MNC) from patients with decreased UBA1 RNA (MDS #1 and #2), but not patients with normal UBA1 RNA expression (MDS #3) (Supplementary Fig. 1A). Sanger sequencing in BM MNC from 33 patients in the cohort (15 MDS-EB and 18 MDS-LB) did not detect the hotspot UBA1 p.Met41 mutations.

Fig. 1. UBA1 RNA expression is downregulated in myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS).

A Relative reads per kilobase of transcript per million reads mapped (RPKM) in bone marrow CD34+ cells from patients with chronic myelomonocytic leukemia (CMML), MDS with excess blasts (MDS-EB), or MDS with low blasts (MDS-LB) relative to healthy donors (HD). Bars represent the means + S.E.M. P-values were calculated using one-way ANOVA test. B REACTOME signaling pathways that are specifically activated in MDS-LB with UBA1 downregulation. FDR false discovery rate. C Frequent mutations detected by next-generation sequencing in the bone marrow of patients with MDS. D REACTOME signaling pathways that are associated with genes specifically upregulated in MDS-LB UBA1 downregulation and SF3B1 mutation. These pathways were defined by GSEA analysis using the list of genes specifically overexpressed in MDS-LB with both UBA1 downregulation and SF3B1 mutation comparing to HD (but not in other patients with MDS-LB comparing to LD).

For clinical characteristics, MDS-EB patients with UBA1 RNA downregulation (≥1.5-fold decrease compared with HD) (n = 11) had lower white cell counts in peripheral blood (PB) compared to MDS-EB with normal UBA1 RNA (n = 18; 2.2 × 109/L compared with 3.5 × 109/L, P = 0.02). This difference was more obvious for neutrophil (0.69 × 109/L compared with 1.5 × 109/L, P < 0.005) (Supplementary Fig. 1B). There is a higher percentage of complex cytogenetic abnormalities in patients with UBA1 downregulation (55% compared with 22%, P = 0.05). In MDS-LB, patients with UBA1 downregulation (n = 11) had lower levels of hemoglobin (9.2 g/dL compared with 10.8 g/dL, P = 0.048) but higher platelet counts (187 × 109/L compared with 105 × 109/L, P = 0.02) (Supplementary Fig. 1C). To investigate the biological signals affected by UBA1 downregulation in MDS, we performed gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA, REACTOME) [6] using RNA-seq data. While no pathway was specifically altered in MDS-EB with UBA1 downregulation compared to HD, multiple pathways were specifically activated in MDS-LB with UBA1 downregulation (q < 0.25; Fig. 1B) but not in other MDS-LB. Of note, most of these pathways are involved in inflammation and innate immune signal activation. Consistently, a tendency of increased level of interferon-β was detected in PB of MDS-LB with UBA1 downregulation (Supplementary Fig. 1D).

We next examined whether UBA1 downregulation co-occurred with specific mutations in MDS. Figure 1C illustrated mutations detected by targeted sequencing of 81 myeloid neoplasm genes in 42 patients (20 MDS-LB and 22 MDS-EB) [7]. While no mutation specifically co-occurred with UBA1 downregulation in MDS-EB (Fig. 1C), in MDS-LB, mutations in splicing genes (SF3B1, SRSF2, U2AF1, and ZRSR2), particularly in SF3B1, tended to co-occur with UBA1 downregulation (Fig. 1C). Of the 11 MDS-LB patients with UBA1 downregulation, ten (91%) carried splicing gene mutations, and among them 6 (55%) had SF3B1 mutations. Mutant SF3B1 is known to cause alternative pre-mRNA splicing in hematopoietic cells [8]. To examine whether the SF3B1 mutations in MDS-LB cause abnormal splicing of UBA1 pre-mRNA in MDS BM HSPCs, we analyzed alternative splicing (alternative 3’ and 5’ splicing-sites, mutually exclusive exons, retained introns, and skipped exons) in SF3B1 mutant MDS-LB. This analysis detected 1060 significant alternative splicing events (>30% change compared with HD; P < 0.05) in SF3B1 mutant but not wildtype MDS-LB (Supplementary Fig. 2A). There was no UBA1 alternative splicing in these events, suggesting that the co-occurrence of UBA1 downregulation and SF3B1 mutations in MDS-LB was not due to mis-splicing of UBA1 pre-mRNA by mutant SF3B1. On the other hand, genes specifically overexpressed in MDS-LB with concurrent UBA1 downregulation and SF3B1 mutations were enriched in pathways of autophagy, mitophagy, cell-cycle regulation, innate immunity, mTOR signals, and signals regulated by forkhead-box transcription factor-O (FOXO; Fig. 1D). Consistently, major FOXO family members, FOXO3 and FOXO4, were overexpressed specifically in MDS-LB with both UBA1 downregulation and SF3B1 mutations (n = 6; Supplementary Fig. 2B). PB interferon-β level also had a strong tendency to be increased in patients with concurrent UBA1 downregulation and SF3B1 mutation (Supplementary Fig. 2C). These findings suggest a cooperative interaction between UBA1 downregulation and SF3B1 mutation to activate disease-driving signals in MDS.

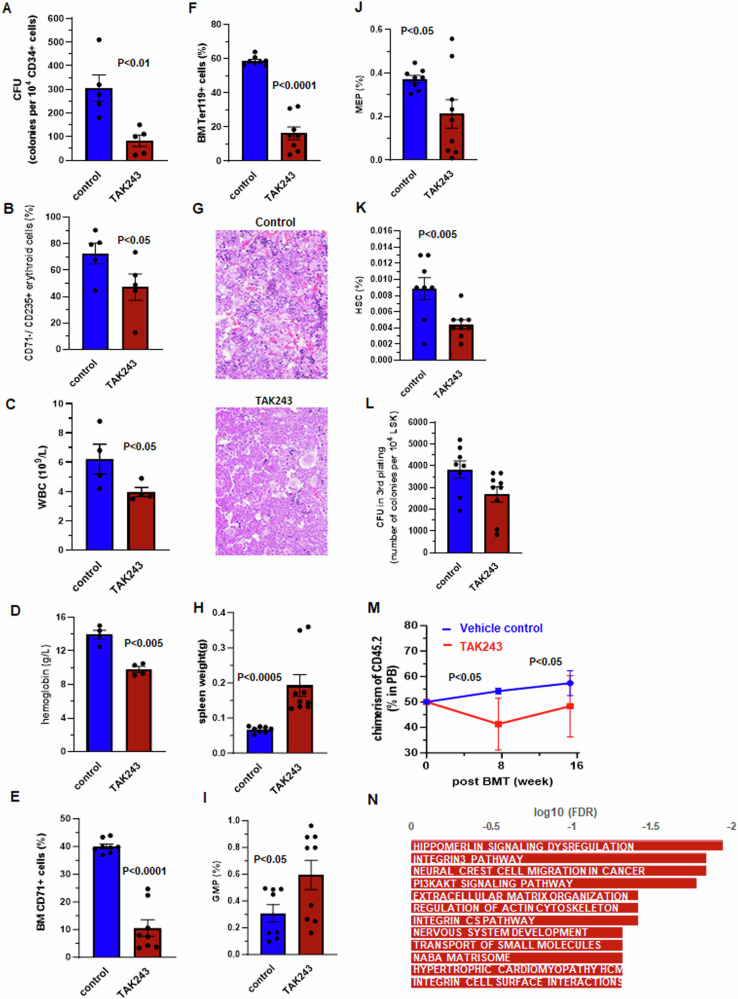

To investigate whether decreased UBA1 activity contributes to impaired functions of BM HSPC in MDS, we applied TAK243 [9, 10], a small-molecule UBA1 inhibitor to human BM HSPC. TAK243 (50 nM) reduced poly-ubiquitination (K63) in hematopoietic K562 cells (Supplementary Fig. 3A). The same dose was assessed for its impact in hematopoietic repopulation activities of CD34 + BM HSPCs by colony formation unit (CFU) assays. TAK243-treated CD34+ cells from HD (n = 6) had significantly fewer CFU than control-treated counterparts (Fig. 2A). Moreover, there were significantly fewer CD71-/CD235a+ erythroid cells in TAK243-treated colonies than in control-treated colonies (Fig. 2B). These results support that UBA1 inhibition has a negative effect on hematopoietic repopulating activity of BM HSPCs, particularly their erythropoietic activity.

Fig. 2. Impact of UBA1 inhibition by TAK243 in human bone marrow hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells and mice.

TAK243 in cultured CD34+ bone marrow hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells (n = 6) led to decreased (A) colony-forming units (CFU) and (B) CD71–/CD235+ erythroid cells. Significant differences in white blood cell count (WBC) (C) and hemoglobin (D) between mice treated with TAK243 (n = 4) and those treated with vehicle control (n = 4). Significant differences in frequencies of bone marrow (BM) early erythroid cells (CD71+) (E) and mature erythroid cells (Ter119+) (F) between TAK243- and control-treated mice (n = 8 for each treatment). G BM histopathology findings at 100× (upper) magnification from control-treated (top) and TAK243-treated (bottom) mice. H Significant differences in spleen weight between TAK243− (n = 9) and control-treated (n = 8) mice. Significant differences in frequencies of BM granulocyte-marcrophage progenitor (GMP) (I) megakaryocyte-erythroid progenitors (MEP) (J) and hematopoietic stem cells (HSC) (K) between mice treated with TAK243 (n = 9) and those treated with vehicle control (n = 8). L Colony-forming units (CFU) in the third plating of colony formation assays using bone marrow LSK cells of TAK243− (n = 9) and control-treated (n = 8) mice. M CD45.2 chimerism in the peripheral blood (PB) of CD45.1 recipient mice transplanted with bone marrow cells of TAK243− (n = 6) and control-treated (n = 4) CD45.2 mice. N Signaling pathways associated with upregulated genes in LSK cells of TAK243-treated mice compared with control-treated mice. FDR false discovery rate. Bars represent the means + S.E.M. P-values were calculated using one tail t-test.

We next characterized the in vivo effect of TAK243 (10 mg/kg) in hematopoiesis of adult BL6 mice. TAK243 reduced poly-ubiquitination (K63) and Uba1a but increased free-ubiquitin in spleen cells of treated mice (Supplementary Fig. 3B). In PB, TAK243 led to significant decreases in white cell counts (4 × 109/L compared with 6.2 × 109/L, P < 0.05; Fig. 2C) and hemoglobin levels (9.8 g/dL compared with 13.9 g/dL; Fig. 2D). Consistently, both BM CD71+ early erythroid cells (10.5% compared with 40.0%; Fig. 2E) and Ter119+ late-stage erythroid cells (16.3% compared with 58.8%; Fig. 2F) were decreased in TAK243-treated mice compared with control-treated mice. Histopathologic review showed a reduction of erythroid cells (clusters of dark nuclear cells in hematoxylin and eosin stains) in BM biopsies of TAK243-treated mice compared with control-treated mice (Fig. 2G), providing further evidence that erythropoiesis is inhibited by UBA1 inhibition. In addition, spleens in TAK243-treated mice were significantly larger than in control-treated mice (0.20 g compared with 0.07 g; Fig. 2H), suggesting extramedullary hematopoiesis. Moreover, TAK243-treated mice had decreased lymphocyte frequencies (81% compared with 90%; Supplementary Fig. 3C) but increased frequencies of PB monocytes (3.3% compared with 1.8%; Supplementary Fig. 3D) and neutrophils (13.3% compared with 7.1%; Supplementary Fig. 3E), suggesting a myeloid-skewing. Consistently, frequencies of BM Gr1+/CD11b+ myeloid population significantly increased (67.9% compared with 16.0%; Supplementary Fig. 3F), whereas frequencies of BM CD220+ lymphoid cells decreased (1.4% compared with 6.6%; Supplementary Fig. 3G).

In BM HSPCs, TAK243 led to increased frequency of granulocyte-macrophage progenitors (GMP, 0.59% compared with 0.31%; Fig. 2I) and decreased frequency of megakaryocyte-erythroid progenitors (MEP, 0.21% compared with 0.37%; Fig. 2J). The frequency of BM hematopoietic stem cells (HSC, lineage–/Sca1+/cKit+〈LSK〉/CD150+/CD48–) also significantly decreased in TAK243-treated mice compared with control-treated mice (0.004% compared with 0.009%; Fig. 2K). We evaluated the repopulating activity of BM HSPC by CFU assays using LSKs. Significantly lower CFU was observed in LSKs from TAK243-treated mice (Fig. 2L). Moreover, in competitive transplantation analysis, the recipient CD45.1 mice transplanted with CD45.2 BM from TAK243-treated donors had significantly lower CD45.2 chimerism than that in recipient mice that were transplanted with BM from control-treated donors (Fig. 2M).

To dissect molecular signals underlying the impaired hematopoiesis led by UBA1 inhibition, we performed RNA-seq using BM LSKs from drug-treated mice and identified 271 genes to be significantly upregulated in BM LSKs from TAK243-treated mice compared with counterparts from control-treated mice (>2-fold, q < 0.05; Supplementary Table 2). GSEA indicated that these genes were enriched in pathways known to regulate hematopoiesis and leukemogenesis, such as PI3/AKT and integrin signaling pathways (Fig. 2N). TAK243 also led to increased innate immune genes such as complement cascade genes C1s2 and C6 (Supplementary Fig. 3H).

UBA1 encodes the major activating enzymes for ubiquitination, which is one of the most important protein modifications that regulate numerous biological processes and signals, including hematopoiesis [11–13]. As far as we know, the current work is the first to report that, in addition to somatic mutations of UBA1, there is also a mild but significant downregulation of UBA1 RNA in BM HSPCs of MDS. Moreover, particularly in MDS-LB, UBA1 downregulation is associated with activation of inflammatory signals and mutations of splicing genes such as SF31B. Of note, the decrease of UBA1 RNA expression in MDS was relatively modest (~30% downregulation), which could be due to the essential role of UBA1 in ubiquitination processes. In C. elegans and yeast, total loss of UBA1 is lethal [14, 15]. Consistently, the UBA1 mutations identified in both VEXAS and MDS only lead to partial reductions but not complete loss of UBA1 proteins [3]. We also demonstrate that, in both human BM cells and mice, inhibition of UBA1 activity leads to impaired hematopoiesis, including reduced repopulating activity of BM HSPC, myeloid-bias, and reduced erythropoiesis, without obvious cytotoxicity (Supplementary Fig. 3I). Of importance, these alterations led by UBA1 inhibition are similar with key pathological features of MDS. Overall, our findings provide important information to further characterize UBA1 and its pathophysiological roles in both MDS and the overlapping systemic inflammatory and autoimmune diseases.

Supplementary information

Acknowledgements

This work is supported by MD Anderson Internal Research Grant (IRG). We thank for sharing Dr. Simona Colla for sharing the K562 cell line, which was from Dr. Siddhartha Mukherjee. We also thank Erica Goodoff, Senior Scientific Editor in the Research Medical Library at The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, for editing this article.

Author contributions

YW: Concept and design; collection and assembly of data; data analysis and interpretation; manuscript writing; and final approval of manuscript. HZ, ZL, PPL, FD, RK-S, HY, DH: Collection and assembly of data; data analysis and interpretation; manuscript writing; and final approval of manuscript. GG-M: Conception and design; administrative support; provision of study materials or patients; collection and assembly of data; and final approval of manuscript.

Data availability

To review mouse BM LSK ENA-Seq data, the GEO accession GSE238153,please go to https://urldefense.com/v3/__https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/query/acc.cgi?acc=GSE238153__;!!PfbeBCCAmug!jmvYsDFqpfS_ROFkAKw6yNgNkq1Zet1AIRlELSrmgqgFgmPYMoW1O-1zky-i5RiMfPcQi-s49avwuuRWUDl5$.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This research involving human material and human data is in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. BM specimens were obtained from the MD Anderson Cancer Center tissue bank following institutional guidelines and protocol # PA12-0445_MOD003. Informed consent was obtained from all subjects. Animal experiments were approved by MD Anderson IACUC, protocol # 00001930-RN01.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41375-024-02364-x.

References

- 1.Beck DB, Grayson PC, Kastner DL. Mutant UBA1 and Severe Adult-Onset Autoinflammatory Disease. Reply. N Engl J Med. 2021;384:2164–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zhao LP, Schell B, Sebert M, Kim R, Lemaire P, Boy M, et al. Prevalence of UBA1 mutations in MDS/CMML patients with systemic inflammatory and auto-immune disease. Leukemia. 2021;35:2731–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ferrada MA, Savic S, Cardona DO, Collins JC, Alessi H, Gutierrez-Rodrigues F, et al. Translation of cytoplasmic UBA1 contributes to VEXAS syndrome pathogenesis. Blood. 2022;140:1496–506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wei Y, Zheng H, Bao N, Kanagal-Shamanna R, Class C, Yang H, et al. KDM6B Overexpression and TET2 Deficiency Cooperatively Drive Development of Myelodysplastic Syndrome and Chronic Myelomonocytic Leukemia-like Phenotype in Mice. Blood. 2019;134:562. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Goto Y, Kimura H. Inactive X chromosome-specific histone H3 modifications and CpG hypomethylation flank a chromatin boundary between an X-inactivated and an escape gene. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009;37:7416–28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Croft D, O’Kelly G, Wu G, Haw R, Gillespie M, Matthews L, et al. Reactome: a database of reactions, pathways and biological processes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011;39:D691–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Montalban-Bravo G, Darbaniyan F, Kanagal-Shamanna R, Ganan-Gomez I, Class CA, Sasaki K, et al. Type I interferon upregulation and deregulation of genes involved in monopoiesis in chronic myelomonocytic leukemia. Leuk Res. 2021;101:106511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yin S, Gambe RG, Sun J, Martinez AZ, Cartun ZJ, Regis FF, et al. A Murine Model of Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia Based on B Cell-Restricted Expression of Sf3b1 Mutation and Atm Deletion. Cancer Cell. 2019;35:283–96.e5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hyer ML, Milhollen MA, Ciavarri J, Fleming P, Traore T, Sappal D, et al. A small-molecule inhibitor of the ubiquitin activating enzyme for cancer treatment. Nat Med. 2018;24:186–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Barghout SH, Patel PS, Wang X, Xu GW, Kavanagh S, Halgas O, et al. Preclinical evaluation of the selective small-molecule UBA1 inhibitor, TAK-243, in acute myeloid leukemia. Leukemia. 2019;33:37–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schulman BA, Harper JW. Ubiquitin-like protein activation by E1 enzymes: the apex for downstream signalling pathways. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2009;10:319–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Li J, Chai QY, Liu CH. The ubiquitin system: a critical regulator of innate immunity and pathogen-host interactions. Cell Mol Immunol. 2016;13:560–76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kraft C, Peter M, Hofmann K. Selective autophagy: ubiquitin-mediated recognition and beyond. Nat Cell Biol. 2010;12:836–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kulkarni M, Smith HE. E1 ubiquitin-activating enzyme UBA-1 plays multiple roles throughout C. elegans development. PLoS Genet. 2008;4:e1000131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.McGrath JP, Jentsch S, Varshavsky A. UBA 1: an essential yeast gene encoding ubiquitin-activating enzyme. EMBO J. 1991;10:227–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

To review mouse BM LSK ENA-Seq data, the GEO accession GSE238153,please go to https://urldefense.com/v3/__https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/query/acc.cgi?acc=GSE238153__;!!PfbeBCCAmug!jmvYsDFqpfS_ROFkAKw6yNgNkq1Zet1AIRlELSrmgqgFgmPYMoW1O-1zky-i5RiMfPcQi-s49avwuuRWUDl5$.