Abstract

Mutations in the DNAJC21 gene were recently described in Shwachman–Diamond syndrome (SDS), a bone marrow failure syndrome with high predisposition for myeloid malignancies. To study the underlying biology in hematopoiesis regulation and disease, we generated the first in vivo model of Dnajc21 deficiency using the zebrafish. Zebrafish dnajc21 mutants phenocopy key SDS patient phenotypes such as cytopenia, reduced growth, and defective protein synthesis. We show that cytopenia results from impaired hematopoietic differentiation, accumulation of DNA damage, and reduced cell proliferation. The introduction of a biallelic tp53 mutation in the dnajc21 mutants leads to the development of myelodysplastic neoplasia-like features defined by abnormal erythroid morphology and expansion of hematopoietic progenitors. Using transcriptomic and metabolomic analyses, we uncover a novel role for Dnajc21 in nucleotide metabolism. Exogenous nucleoside supplementation restores neutrophil counts, revealing an association between nucleotide imbalance and neutrophil differentiation, suggesting a novel mechanism in dnajc21-mutant SDS biology.

Subject terms: Cancer models, Cancer metabolism

Introduction

Shwachman–Diamond syndrome (SDS) is an inherited bone marrow failure syndrome (IBMFS) characterized by cytopenia, exocrine pancreatic insufficiency, growth restriction, and skeletal abnormalities. As with many other IBMFS, primary treatment for SDS is allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation which is associated with significant toxicity and engraftment failure in SDS patients. Further, SDS patients are highly predisposed to developing myeloid malignancies such as myelodysplastic neoplasia (MDS) and acute myeloid leukemia (AML) [1–3]. SDS patients with myeloid malignancies have a poor 5-year overall survival of only 15–29% [4, 5].

Approximately 90% of SDS patients have a germline mutation in the Shwachman-Bodian-Diamond Syndrome (SBDS) gene, which functions in ribosomal biogenesis [6, 7], cell proliferation [8, 9], cellular stress response [10] and mitochondrial function [11]. More recently, biallelic germline mutations in the DnaJ Heat Shock Protein Family (Hsp40) Member C21 (DNAJC21) gene were identified in SDS patients who did not harbor SBDS mutations [12]. DNAJC21 is required in the final maturation step of the 60S large ribosomal subunit, where it associates with PA2G4, the nuclear-cytoplasmic shuttling factor that transports the pre-60S subunit to the cytoplasm [13]. Homozygous nonsense mutations have been reported in DNAJC21 suggesting that complete loss of DNAJC21 is not lethal. This contrasts with the lack of patients with homozygous SBDS loss [14]. Accordingly, animal models including mice and zebrafish with biallelic nonsense mutations in Sbds die during early embryogenesis [15–17]. To date, no in vivo models of DNAJC21 mutations have been reported.

Given the rarity of SDS, only a limited number of studies examining the clonal landscape of SDS-AML evolution have been published [18–20]. Somatic TP53 mutations are the most frequently identified mutations in SDS patients with myeloid malignant transformation. However, their presence in SDS patients without concomitant malignant transformation limits their usefulness for clinical surveillance [18–20].

Here, we report the first in vivo model of dnajc21-mutant SDS employing the zebrafish. Dnajc21 loss accurately recapitulated the neutropenia, anemia, and reduced growth seen in SDS patients with DNAJC21 mutations. We show that Dnajc21 is required for normal hematopoietic differentiation and cell proliferation. Using transcriptomics and metabolomics, we uncover a novel role for Dnajc21 in regulating nucleotide metabolism. We show that reduced nucleotide availability contributes to neutropenia development in dnajc21 mutants and exogenous nucleoside supplementation is able to reverse this effect.

Methods

Zebrafish lines

All zebrafish studies were performed in accordance with approved protocols by the University of Ottawa Animal Ethics Committee under protocol number 4243. Casper [21], dnajc21 and dnajc21/tp53 mutant fish, and transgenic lines were raised and maintained as previously described [22].

CRISPR-Cas9 genomic editing was used to generate the dnajc21 mutant. Single guide RNAs (sgRNAs) targeting exons 5 and 6 were designed. sgRNAs were synthesized as previously described [23]. Zebrafish codon-optimized Cas9 mRNA was synthesized from the pT3TS-nCas9n plasmid (46,757, Addgene, Watertown, MA, USA) using the mMessage mMachine T3 kit (Thermo Fisher, Waltham, MA, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. One-cell stage wildtype zebrafish embryos were injected with 300 ng/µL Cas9 mRNA and seven sgRNAs (Table. S1) pooled to a final concentration of 350 ng/µL. Mutant embryos were identified by genotyping via PCR with the mutant and wildtype alleles resulting in amplicon sizes of 236 bp and 1621 bp, respectively.

For mRNA rescue assays, a full-length dnajc21 mRNA construct in a pcDNA3.1 + /C-(K)DYK vector was obtained from GenScript Biotech (Piscataway, NJ, USA). mRNA was synthesized using the mMessage mMachine transcription kit (Thermo Fisher) and 200 pg mRNA was injected into dnajc21−/− mutant embryos at the one-cell stage. Embryos were fixed at 48 hours post-fertilization (hpf) for Sudan Black staining.

For weight measurements, adult fish were anesthetized with 0.02% Tricaine and placed on a petri dish. Any excess water was wiped, and the dish was placed on a scale. Fish were immediately returned to their tanks.

Hematopoietic characterization

For the whole-mount in situ hybridization (WISH) and Sudan Black staining experiments, embryos obtained from crossing dnajc21 heterozygous adult fish were used. Post-staining, embryos were genotyped by PCR, as described above. Homozygous crosses were subsequently used to confirm the observed phenotypes. dnajc21+/− embryos showed normal hematopoiesis, similar to wildtype (data not shown).

WISH for common blood lineage genes was performed as previously described [24]. Antisense digoxigenin-labeled mRNA probes for cebpa, gata1, hbbe3, lcp1, mpx, myb and spi1b were generated.

For Sudan Black staining, fixed embryos were stained with 0.045% Sudan Black B (Millipore Sigma) in 70% ethanol at room temperature for 45 min followed by depigmentation. Stained cells in the trunk, as outlined by black boxes in the respective figures, were counted using the Cell Counter plugin on ImageJ [25].

Adult fish were anesthetized with 0.02% Tricaine and the whole kidney marrow (WKM) was dissected. To detect dysplasia, WKM touchpreps were prepared and stained with May Grünwald–Giemsa (Millipore Sigma, Burlington, MA, USA). For flow cytometry, WKMs were dissociated in PBS containing 1% fetal bovine serum (FBS) by gentle trituration using a 1 mL syringe fitted with 21-gauge needle and filtered using a 40 µm cell strainer. Cell viability was determined using the Calcein Violet 450 AM dye (Thermo Fisher). WKM populations were analyzed on the Beckman Coulter Gallios Flow Cytometer based on their forward scatter and side scatter profiles as previously described [26]. Analysis was carried out using Kaluza Analysis Software (Beckman Coulter, Brea, CA, USA).

Drug treatments

For nucleoside supplementation, zebrafish embryos were incubated with 100 mM uridine [27] or 100 mM thymidine (Millipore Sigma) dissolved in embryo media (E3) from 3–48 hpf for Sudan Black staining or 3–4 days post-fertilization (dpf) for larval length assays. Assays were blinded by randomly assigning 30 wildtype or dnajc21−/− embryos to each well of a 12-well plate. Eight embryos per well were subjected to PCR to determine the genotype of the wells and correlated to the corresponding neutrophil counts or larval length measurements.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using GraphPad Prism 8.0. All data are represented as mean ± standard deviation. Data from qPCR, WISH, and Sudan Black staining experiments were subjected to unpaired student t-tests. Data from immunostaining, LPS, gcsf, and drug treatment assays were subjected to one-way ANOVA using Tukey’s multiple comparisons tests. The number of experimental replicates and significance p-values are described in each figure legend.

Additional methods are described under supplementary information.

Results

Zebrafish dnajc21 mutants phenocopy SDS

Zebrafish have a single DNAJC21 orthologue with 76.84% sequence identity to the human protein (Fig. S1A). We characterized the spatial distribution of wildtype dnajc21 mRNA during embryogenesis using WISH at different embryonic developmental stages (Fig. S1B). dnajc21 expression was largely ubiquitous until 24 hpf. By 48 hpf, increased expression was observed in the notochord and inner ear and later in the intestinal bulb by 96 hpf.

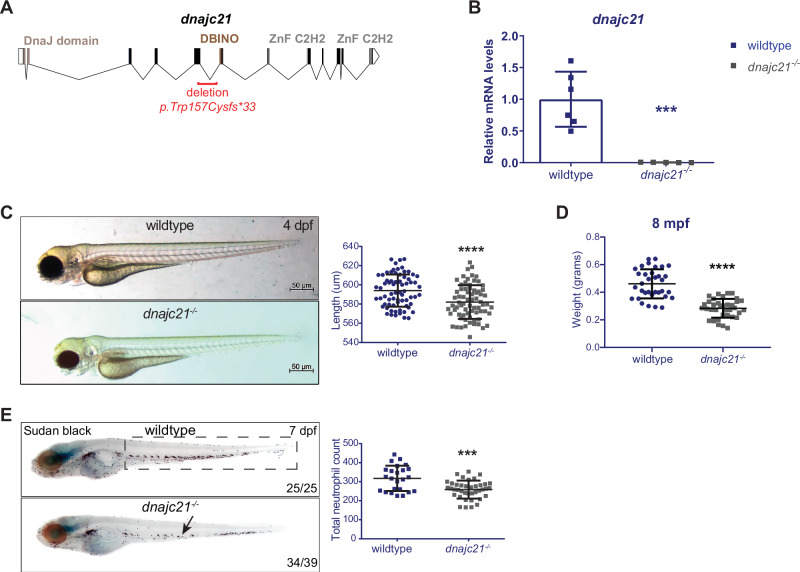

In patients with DNAJC21 mutations, missense, and frameshift mutations occur in the DNAJ domain or upstream of the two zinc finger motifs [12, 13]. Using CRISPR-Cas9 genomic editing, we generated a 1385 bp deletion spanning exons 5 and 6 of the dnajc21 gene. This was predicted to cause a nonsense mutation, p.W157Cfs*33, resulting in premature truncation upstream of the DBINO DNA binding domain and the two zinc finger motifs (Fig. 1A, S1A). This mutation partially overlaps the V148Kfs*30 patient mutation. qPCR revealed a significant downregulation of dnajc21 mRNA in mutant homozygous embryos at 48 hpf (Fig. 1B). By 4 dpf, mutant larvae exhibited reduced growth (Fig. 1C), but no other morphological abnormalities were observed. Growth restriction was also observed in adult fish, with dnajc21 mutants weighing significantly less than their wildtype counterparts at 8 months post-fertilization (mpf) (Fig. 1D). Using Sudan Black staining [28], we observed fewer total neutrophils in dnajc21−/− mutant compared to wildtype embryos at 48 hpf (Fig. S1C). This difference became more significant at 7 dpf (Fig. 1E), suggesting progressive neutropenia. Injection of dnajc21−/− mutant embryos with wildtype zebrafish dnajc21 mRNA was able to rescue the neutrophil loss (Fig. S1C), confirming the specificity of the mutant phenotype. Survival analysis revealed that the dnajc21−/− mutant fish are viable to adulthood but show reduced survival by 8 mpf (Fig. S2). Thus, Dnajc21 deficiency in zebrafish recapitulates key hallmarks of SDS, such as neutropenia and poor growth.

Fig. 1. dnajc21-mutant zebrafish exhibit reduced growth and neutropenia.

A Schematic of the zebrafish dnajc21 gene showing locations of the deletion and important functional domains. B qPCR analysis showing downregulation of dnajc21 mRNA in dnajc21−/− mutant embryos compared to wildtype at 48 hpf. Each datapoint represents RNA extracted from a pool of n = 30 larvae. b-actin and eef1a1l1 were used for normalization. C Brightfield lateral view images of dnajc21−/− mutant and wildtype larvae at 4 dpf. Graph shows quantification of larval length. Two biological replicates, each comprising 30–60 embryos per genotype, were analyzed. D Weight measurements of wildtype (n = 34) and dnajc21−/− (n = 36) fish at 8 mpf. E Lateral views of Sudan Black staining in dnajc21−/− mutant and wildtype larvae at 7 dpf. Arrow indicates reduced staining. Two biological replicates, each comprising 20 embryos per genotype, were analyzed. Numbers on the lower right indicate the number of larvae with the same phenotype. The black dotted box marks the region in the trunk used for counting. Number of neutrophils per embryo is quantified in the graph. hpf: hours post-fertilization; dpf: days post-fertilization; mpf: months post-fertilization ***p < 0.0001; ****p < 0.00001.

Global protein synthesis is reduced in the dnajc21 mutants

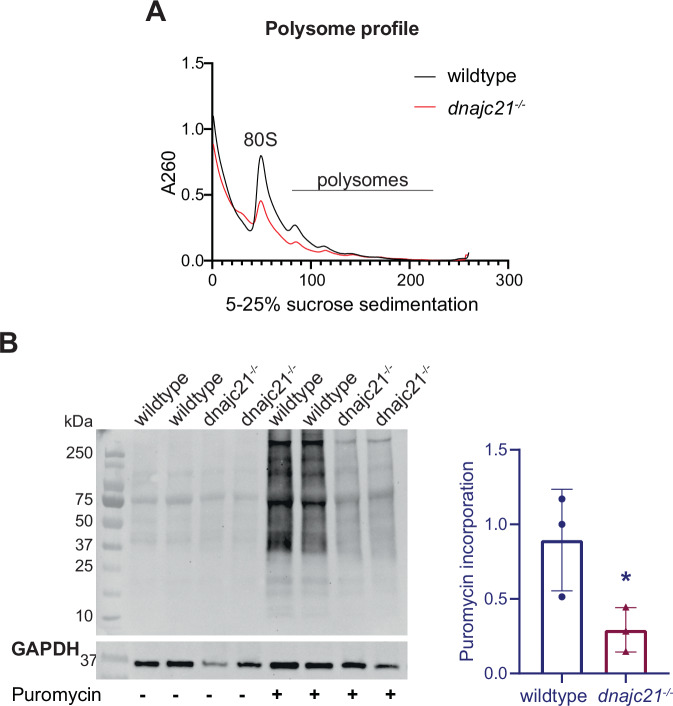

Given the known function of DNAJC21 in 60S ribosomal subunit maturation, we characterized ribosomal function in our mutant using polysome profiling. Across various sucrose gradients, we observed a consistent reduction of 80S monosome and polysomes in dnajc21−/− mutant larvae compared to wildtype at 5 dpf (Figs. 2A, S3). To analyze the subsequent impact on protein synthesis, we used puromycin to label nascent proteins in wildtype and dnajc21−/− mutants at 5 dpf (Fig. 2B). A significantly lower puromycin incorporation was observed in the dnajc21−/− mutants, suggesting an impairment of global protein synthesis, another key phenotypic hallmark of SDS.

Fig. 2. dnajc21 mutants show reduced global translation.

A Representative polysome profiles of wildtype and dnajc21−/− mutant embryos at 48 hpf. B Immunoblotting following puromycin incorporation into nascent proteins in wildtype and dnajc21−/− mutant embryos at 48 hpf. GAPDH was used as loading control. Intensity of puromycin signal relative to GAPDH was measured. hpf: hours post-fertilization. *p < 0.01.

Dnajc21 is required for normal myeloid and erythroid differentiation

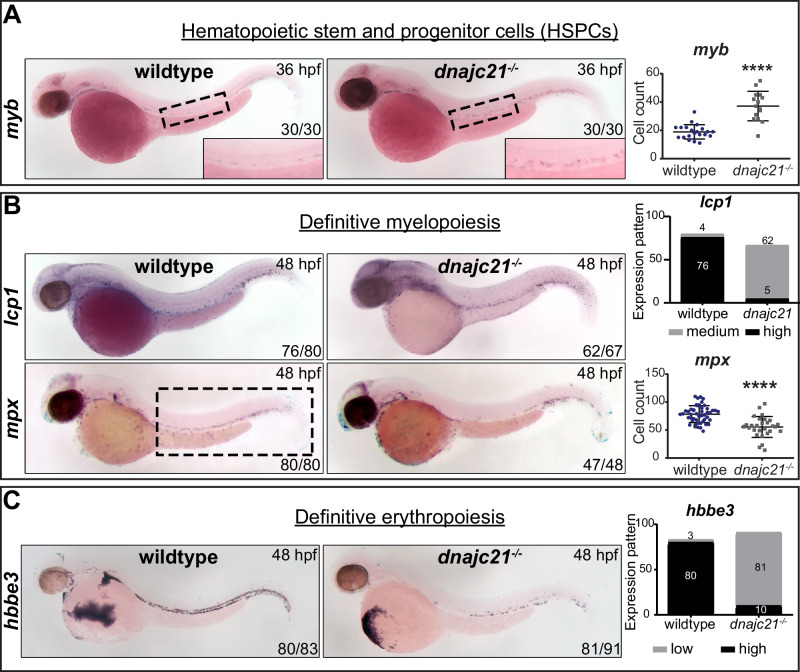

To determine the origin of the observed neutropenia, we investigated the role of Dnajc21 in hematopoietic specification using WISH for key blood lineage markers. In zebrafish, bipotential hemangioblasts give rise to blood and endothelial cells, including erythrocytes and leukocytes that constitute the primitive hematopoietic wave from 12 to 24 hpf [29]. While we observed no changes in spi1b+ common myeloid progenitors and gata1+ erythrocytes, lcp1+ total leukocytes were reduced in the dnajc21−/− mutants compared to wildtype at 24 hpf (Fig. S4). By 28 hpf, a hematopoietic stem cell-derived definitive hematopoietic wave initiates from the dorsal aorta, which then gives rise to all blood lineages [30]. We observed a significant increase in myb+ hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells (HSPCs) in the dnajc21−/− mutants at 36 hpf (Fig. 3A). Downstream, specification of lcp1+ leukocytes and mpx+ neutrophils (Fig. 3B) were reduced in the dnajc21−/− mutants at 48 hpf. In addition to poor myeloid specification, we observed reduced hbbe3+ mature erythrocytes (Fig. 3C) in the dnajc21−/− mutants at 48 hpf. Our data suggest that Dnajc21 loss impairs HSPC differentiation, resulting in the limited production of mature leukocytes and erythrocytes.

Fig. 3. Dnajc21 loss impairs myeloid and erythroid differentiation.

Brightfield images of whole mount in situ hybridization for (A) myb+ hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells at 36 hpf; the ventral wall of the dorsal aorta is outlined and shown at higher magnification. B lcp1+ total leukocytes and mpx+ neutrophils during definitive myelopoiesis at 48 hpf; and C hbbe3+ mature erythrocytes during definitive erythropoiesis at 48 hpf. Lateral views are shown with anterior to the left. Numbers on the lower right indicate the number of embryos with the same phenotype. Experiments were done in 2–4 biological replicates, each comprising at least 20 embryos per genotype. The black dotted box marks the region in the trunk used for counting mpx+ neutrophils. Graphs show quantification of cell counts or staining pattern per embryo. hpf: hours post-fertilization. ****p < 0.00001.

To assess the ability of dnajc21 mutants to mount an inflammatory response, we challenged the embryos with lipopolysaccharide (LPS). Wildtype and dnajc21−/− mutant fish carrying the mpx:eGFP transgene were generated by crossing the respective genotypes into the background of mpx:eGFP transgenic zebrafish. LPS or phosphate-buffered saline (PBS, control) was injected into the yolk of transgenic wildtype and dnajc21−/− mutant embryos at 48 hpf, and neutrophil recruitment was measured at 4 hours post-injection. LPS-injected wildtype embryos showed a significant increase in mpx+ neutrophils at the injection site whereas dnajc21−/− mutants exhibited an attenuated response (Fig. S5A). Thus, Dnajc21 loss also impairs neutrophil function. SDS patients present with recurrent viral and bacterial infections, and treatment with granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (G-CSF) is used to stimulate neutrophil production with the goal of reducing the incidence of infections [1]. We asked if the excessive number of immature progenitors seen in dnajc21−/− mutants (Fig. 3A) could be mobilized with G-CSF treatment. Zebrafish gcsf mRNA at concentrations of 20 ng or 100 ng was injected into wildtype and dnajc21−/− mutant embryos at the one-cell stage. WISH for mpx at 48 hpi revealed a significant expansion of neutrophils in the dnajc21−/− mutants but not to wildtype-like levels (Fig. S5B).

A tp53 gain-of-function mutation partially rescues neutropenia but leads to MDS development in the dnajc21 mutants

Aberrant activation of the p53 pathway as a consequence of ribosomal stress is thought to cause cytopenia in many IBMFS [31]. We measured the expression of tp53 and its downstream targets in the dnajc21 mutants at 48 hpf. We also measured the levels of tp53Δ113, an N-terminally truncated form of tp53 that is induced upon DNA damage [32, 33]. Both the DNA damage marker, atm, and the cell cycle regulator, p21, were significantly upregulated but no changes in tp53, tp53Δ113 isoform, puma, or bax expression were seen in the dnajc21−/− mutants compared to wildtype embryos (Fig. S6A). Given the increase in atm, we asked if Dnajc21 loss induces DNA damage and/or increases sensitivity to DNA-damaging agents. We measured the expression of the DNA damage response protein, γ-H2AX, at baseline and following exposure to γ-irradiation. γ-H2AX foci were already increased at baseline in the dnajc21−/− mutants and became further elevated upon irradiation (Fig. S6B). We also studied apoptosis under these conditions using acridine orange staining. While we did not observe differences at baseline, a higher proportion of dnajc21−/− embryos showed apoptosis following irradiation (Fig. S6C). In line with the elevated DNA damage, cell cycle analysis revealed an accumulation of cells in the S-phase in the dnajc21−/− mutants (Fig. S6D). Together, these data suggest that Dnajc21 loss increases DNA damage and the ensuing replication stress impairs cell cycle progression by arresting cells in the S-phase.

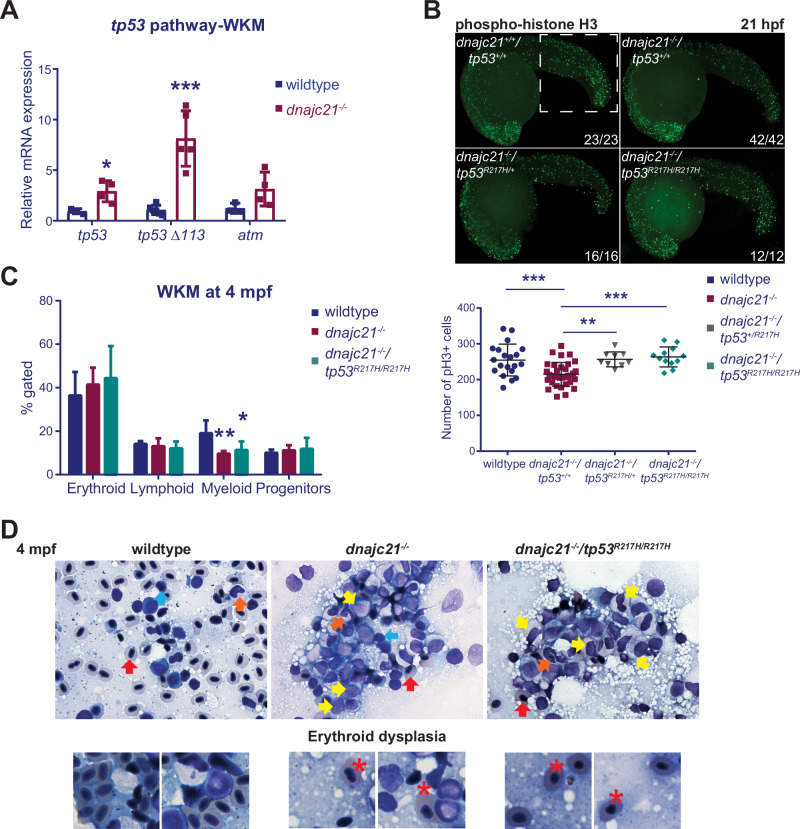

To understand the significance of these findings for hematopoiesis, we looked at the expression of tp53 genes in whole kidney marrows (WKMs, human bone marrow equivalent) isolated from wildtype and dnajc21−/− mutant fish (Fig. S7A). Both tp53 and tp53Δ113 isoforms were upregulated in mutant WKMs at 8 mpf (Fig. 4A). Somatic mutations in the TP53 gene frequently occur as clonal events in SDS patients and can contribute to the development of myeloid malignancies. There are no hotspot mutations and patients can acquire multiple independent TP53 mutant clones [18]. We previously generated a zebrafish line that carries a point mutation in tp53 [34] (second manuscript under review) namely, tp53R217H. The p.R217 locus in zebrafish corresponds to p.R248 in humans, a codon that is frequently mutated in SDS [18] as well as in MDS and AML [35–37]. In mice, tp53 R248 mutations confer novel oncogenic properties, such as protection from apoptosis and inactivation of DNA damage responses [38–40]. We crossed the dnajc21−/− mutant zebrafish with tp53R217H/R217H through two generations to generate a compound homozygous mutant line: dnajc21−/−/tp53R217H/R217H. Sudan Black staining revealed enhanced neutrophil counts in dnajc21−/− mutants carrying the tp53 R217H mutation (Fig. S7B). Ribosomal stress and TP53 activation have been associated with reduced proliferation in IBMFS. Immunostaining for the mitotic marker, phosphorylated histone H3 (pH3), revealed fewer mitotic cells in the dnajc21−/− mutants compared to wildtype at 21 hpf (Fig. 4B), supporting a state of hypo-proliferation. Proliferation was rescued in both dnajc21−/−/tp53R217H/+ and dnajc21−/−/tp53R217H/R217H mutants (Fig. 4B).

Fig. 4. A gain-of-function tp53 mutation partially rescues neutropenia but leads to an expansion of immature progenitors.

A Levels of tp53, tp53 Δ113 isoform, and atm mRNA measured by qPCR in kidney marrows of wildtype and dnajc21−/− fish at 8 mpf. b-actin and eef1a1l1 were used for normalization. B dnajc21−/− mutants were crossed with tp53R217H/R217H to generate compound mutant dnajc21−/−/tp53R217H/R217H fish. Lateral views of pH3 immunofluorescence in wildtype, dnajc21−/−, dnajc21−/−/tp53R217H/+ and dnajc21−/−/tp53R217H/R217H mutant embryos at 21 hpf. Experiments were done in 2 biological replicates. Numbers on the lower right indicate the number of larvae with the same phenotype. The white dotted box marks the region used for counting. The number of pH3+ cells per embryo is quantified in the graph. C Flow cytometry of kidney marrows from wildtype (n = 5), dnajc21−/− (n = 5) and dnajc21−/−/tp53R217H/R217H (n = 3) fish at 4 mpf. Hematopoietic lineages were detected based on the forward and side scatter profiles. D Representative images from Giemsa staining of kidney marrow touch preparations from wildtype (n = 3), dnajc21−/− (n = 5), and dnajc21−/−/tp53R217H/R217H (n = 4) fish at 4 mpf. Arrows indicate mature erythrocytes (red), lymphocytes (blue), myelocytes (yellow), and mature neutrophils (orange). Red asterisks mark dysplastic erythrocytes. hpf: hours post-fertilization; mpf: months post-fertilization *p < 0.01; **p < 0.001; ***p < 0.0001.

Next, we assessed the impact of Dnajc21 loss on adult hematopoiesis through flow cytometry and histopathological analysis of WKMs isolated from wildtype and mutant fish. The myeloid compartment was significantly reduced in the dnajc21−/− mutants but slightly improved in the dnajc21−/−/tp53R217H/R217H mutants compared to wildtype at 4 mpf (Figs. 4C, S7C). Using fish carrying the mpx:eGFP transgene, we further confirmed reduced WKM neutrophils in the dnajc21−/− mutants, which was also partially rescued in the dnajc21−/−/tp53R217H/R217H mutants (Fig. S7D). To further analyze the hematopoietic populations that were most affected, we performed Giemsa staining of kidney marrow smears at 4 and 8 mpf. We observed a progressive expansion of immature progenitors, including myeloid precursors (myelocytes), in both the dnajc21−/− and dnajc21−/−/tp53R217H/R217H mutants (Fig. 4D, S7E). Evaluation of differential counts at 8 mpf revealed cytopenia of the lymphoid lineage in both mutants with no significant changes in the counts of myelocytes and erythrocytes (Fig. S7E). However, we observed erythroid dysplasia, characterized by rounded erythrocytes with irregular nuclear morphology, in both the dnajc21−/− (n = 4/8 fish) and dnajc21−/−/tp53R217H/R217H mutants (n = 4/8 fish) (Fig. 4D). These phenotypes are consistent with the development of MDS. Given that not all fish showed dysplasia, we determined the expression of Dnajc21 accessory factors that function in ribosomal maturation, to rule out functional compensation [18]. We did not observe any changes in the mRNA levels of pa2g4a, pa2g4b, or eif6 in mutant WKMs compared to wildtype at 8 mpf (Fig. S8). In sum, Dnajc21 loss in zebrafish leads to MDS, possibly through the acquisition of mutations in other genes. The presence of a tp53 mutation partially restores neutrophil counts, but concomitantly promotes the expansion of progenitors and erythroid dysplasia.

Transcriptomic analysis of dnajc21 mutants

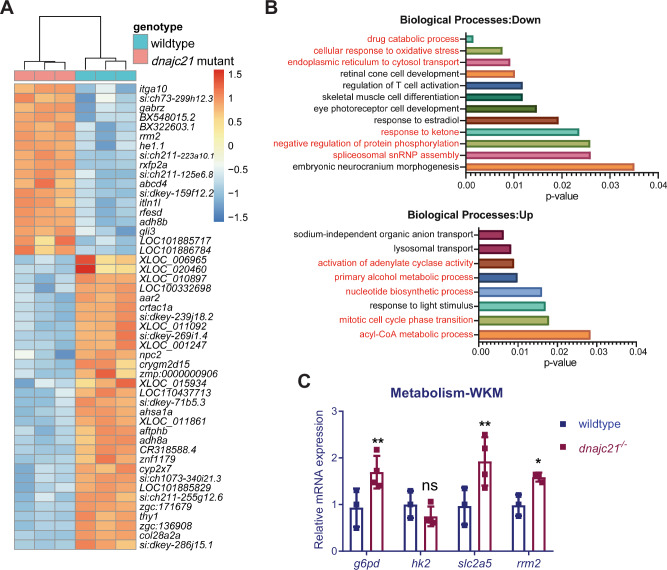

To understand the molecular mechanisms underlying the reduced growth and cytopenia seen in the dnajc21 mutants, we performed bulk RNA sequencing on whole embryos at 48 hpf. A total of 389 genes were downregulated and 240 genes were upregulated (Fig. 5A). Enrichment analysis revealed downregulation of biological processes such as oxidative stress response, drug catabolism, and pre-mRNA spliceosome assembly in the dnajc21 mutants (Fig. 5B). Upregulated processes included several metabolic processes: cyclic AMP synthesis, nucleotide biosynthesis and acyl-CoA synthesis (Fig. 5B). Notably, the ribonucleotide reductase subunit, rrm2, which is important for de novo nucleotide synthesis [41] was overexpressed in the mutants. We also observed dysregulated expression of several glucose metabolism genes including g6pd that catalyzes the first step of the pentose phosphate pathway, and pck1 and ganc, which are involved in gluconeogenesis. To determine if these pathways influence hematopoiesis, we measured the expression of these genes in WKMs isolated from wildtype and dnajc21−/− mutant fish at 8 mpf. Elevated levels of g6pd, slc2a5, and rrm2 were seen in mutant WKMs (Fig. 5C). These findings suggest novel functions for Dnajc21 in the regulation of nucleotide and glucose metabolism.

Fig. 5. RNA sequencing identifies various dysregulated metabolic pathways in dnajc21 mutants.

A Heatmap shows hierarchical clustering of the top 50 differentially expressed genes in dnajc21−/− mutant vs. wildtype embryos. RNA sequencing was performed on pools of 30 embryos at 48 hours post-fertilization. B Gene ontology enrichment analysis showing top downregulated and upregulated biological processes. Processes related to metabolism, protein homeostasis, and cell proliferation are highlighted in red font. C Validation of altered glucose and nucleotide metabolism genes by quantitative PCR in wildtype and dnajc21−/− whole kidney marrows (WKMs) at 8 months post-fertilization. b-actin and eef1a1l1 were used for normalization. *p < 0.01; **p < 0.001.

Defective nucleotide biosynthesis may contribute to neutropenia in dnajc21-mutant SDS

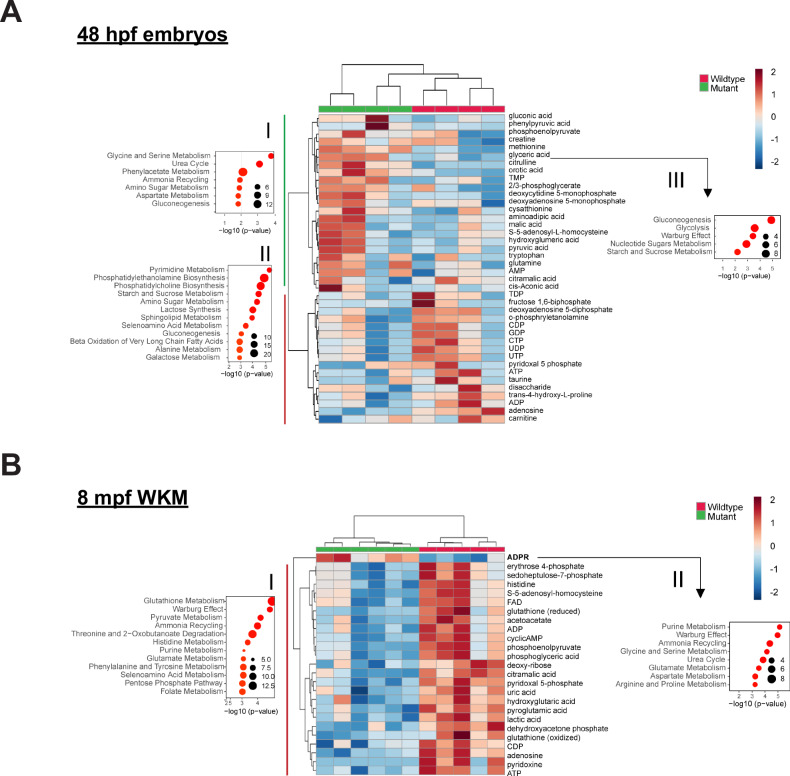

Given that various metabolic pathways were altered and since metabolism is a known regulator of blood cell homeostasis and leukemogenesis [42, 43], we performed untargeted metabolomics using liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry of whole embryos at 48 hpf and WKMs at 8 mpf. In dnajc21−/− mutant embryos, metabolites such as citrulline, glyceric acid, methionine, and orotic acid were significantly upregulated whereas adenosine was significantly downregulated (Fig. 6A). The top upregulated pathways were urea cycle, amino acid metabolism (glycine, serine, aspartate, alanine, etc.), phenylacetate metabolism and gluconeogenesis (Fig. 6AI). Pyrimidine metabolism and biosynthesis of phosphatidylethanolamines and phosphatidylcholines were the top downregulated pathways in the mutants (Fig. 6AII). In dnajc21−/− mutant WKMs, only ADP-ribose (ADPR) was upregulated whereas all other metabolites were significantly reduced (Fig. 6B). Glutathione metabolism, pyruvate metabolism, ammonia recycling, and purine metabolism were among the top downregulated pathways in the mutants (Fig. 6BI).

Fig. 6. Nucleotide metabolism is altered in dnajc21 mutants.

Heatmaps show hierarchical clustering of selected set of altered metabolites in dnajc21−/− mutant vs. wildtype (A) embryos at 48 hpf and (B) whole kidney marrows (WKMs) at 8 mpf. Metabolites are selected based on t-test comparison. Pathway enrichment analysis is performed for subsets of metabolites showing higher concentration in (A.I) mutant embryos, (A.II) wildtype embryos, and (B.I) kidney samples. Analysis of pathway enrichment for correlation partners of the most significantly differentially concentrated metabolites in mutant and wildtype samples is shown in (A.III) for citrulline and orotic acid in mutant embryos and (B.II) ADPR for mutant kidney. Enrichment graphs show p-values on the x-axis and size of the bubble indicates the number of significantly altered metabolites for each pathway. FAD—flavin adenine dinucleotide; ADP—adenosine 5-diphosphate; cyclicAMP—adenosine 3-5-cyclic monophosphate; CDP—cytidine 5-diphosphate; CTP—cytidine 5-triphosphate; ATP—adenosine 5-triphosphate; AMP—adenosine 5-monophosphate; TMP—thimidine 5-monophosphate; DMP—deoxycytidine 5-monophosphate; ADPR—ADP-ribose. hpf: hours post-fertilization; mpf: months post-fertilization.

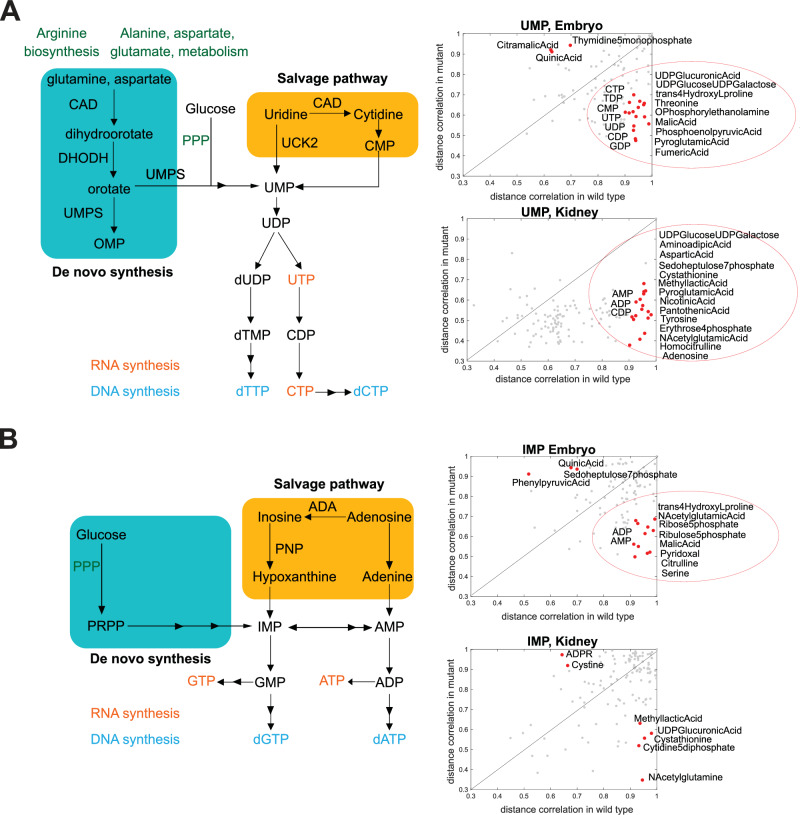

Next, we analyzed metabolites that showed significant distance correlations (p < 0.01) to the most altered metabolites in each dataset (citrulline and orotic acid for embryos; ADPR for WKMs). Pathway enrichment of correlation partners identified the Warburg effect in both the embryo and WKM datasets (Fig. 6AIII, BII). Additional pathways in the embryos included gluconeogenesis, glycolysis, and metabolism of nucleotide sugars (Fig. 6AIII). Given the overrepresentation of ADPR correlates in the WKM, purine metabolism was identified as the top hit (Fig. 6BII). On closer inspection, most metabolites in the purine pathway show reduced concentrations in the mutant WKMs (Table. S2). In fact, we observed a decrease in ADP and ATP levels accompanied by AMP accumulation, suggesting a potential energy deficit in the dnajc21 mutants (Fig. 6A, B). Among the pyrimidine metabolites, CDP showed reduced concentrations with a p < 0.01 cut-off (Fig. 6B). Furthermore, we observed significantly poor correlation of the bottleneck metabolites uridine monophosphate (UMP) and inosine monophosphate (IMP) with pyrimidine and purine pathway [44] metabolites, respectively (Fig. 7A, B). Overall, our findings point to dysregulated nucleotide metabolism in the dnajc21 mutants involving both de novo and salvage pathways.

Fig. 7. Distance correlation analysis shows major changes in pyrimidine and purine metabolism.

Schematic representations of de novo and salvage nucleotide biosynthesis are shown. Scatter plot graphs show distance correlations between (A) UMP or (B) IMP and all other metabolites measured. Correlation is calculated separately for wildtype and mutant fish. Separate analysis is done for embryo and kidney samples. Each point in the graph shows value in two groups of samples for a metabolite pair. Indicated in red and with metabolite names are correlations that show differences in wildtype and mutant animals (correlations that are very high, over 0.9 in one group of animals, and low, under 0.7 in the other group).

Exogenous nucleoside supplementation rescues neutropenia in the dnajc21 mutants

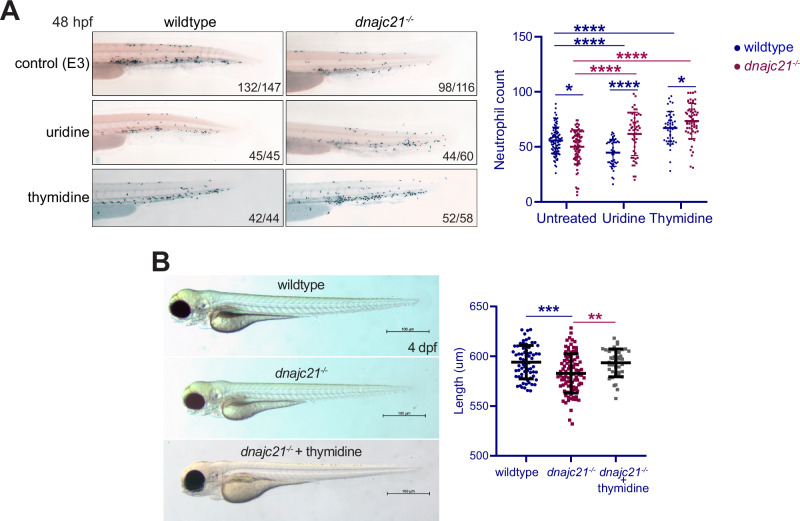

Given the observed reduction in pyrimidine nucleotides as well as the accumulation of orotic acid in the dnajc21 mutant embryos, we wondered if overcoming the pyrimidine deficiency might rescue neutropenia in these embryos. We first treated the fish with uridine, that serves as a precursor for the synthesis of both thymine and cytosine ribonucleotides as well as deoxyribonucleotides. Wildtype and dnajc21−/− mutant embryos were treated with 100 mM uridine from 3 to 48 hpf followed by Sudan Black staining. No toxicity was observed at these doses (Fig. S9). Whereas uridine treatment significantly improved neutrophil counts in the dnajc21−/− mutants, it surprisingly reduced neutrophils in wildtype embryos (Fig. 8A). Next, we evaluated the effects of thymidine, the only nucleoside that is unique to the dNTP pool. Wildtype and dnajc21−/− mutant embryos were treated with 100 mM thymidine from 3 to 48 hpf followed by Sudan Black staining. Thymidine increased neutrophil counts in both the dnajc21−/− and wildtype embryos (Fig. 8A). In addition, thymidine treatment also rescued the growth restriction observed with Dnajc21 loss. At 4 dpf, the length of dnajc21−/− larvae was significantly greater in the treated versus untreated group (Fig. 8B). Given the known role of thymidine in arresting cells in S-phase, we performed cell cycle analysis (Fig. S10). As expected, wildtype embryos showed an accumulation of cells in S-phase, consistent with the effects of having excess thymidine [45]. In contrast, in dnajc21−/− mutants that have low endogenous thymidine, supplementation rescued the S-phase arrest and restored cell cycle progression. In sum, these data show that restoring pyrimidine nucleotide supply rescues neutropenia in dnajc21-mutant zebrafish.

Fig. 8. Exogenous nucleoside supplementation restores neutropenia in dnajc21 mutants.

A Lateral views of Sudan Black staining in wildtype and dnajc21−/− mutant embryos at 48 hpf following treatment with 100 mM uridine or 100 mM thymidine from 3 to 48 hpf. Experiments were done in two biological replicates, each comprising at least 20–30 embryos per condition. Numbers on the lower right indicate the number of larvae with the same phenotype. Number of neutrophils per embryo is quantified in the graph. B Brightfield lateral view images of wildtype and dnajc21−/− mutant larvae untreated or treated with 100 mM thymidine from 3 hpf to 4 dpf. Graph shows quantification of larval length. Two biological replicates, each comprising at least 20 embryos per genotype, were analyzed. hpf: hours post-fertilization; dpf: days post-fertilization. *p < 0.01; ***p < 0.0001; ****p < 0.00001.

Discussion

Impaired ribosomal function, DNA damage, and oxidative stress are inherent features of most IBMFS. These syndromes are characterized by poor energy production in keeping with reduced cell proliferation, accelerated cell death, and cytopenia [11, 46, 47]. How ribosomal function regulates metabolism and growth is a topic of growing interest. In SDS, the unique presence of exocrine pancreatic insufficiency adds an extra layer of metabolic complexity. A further question that remains unanswered is how energy-deficient cells in IBMFS acquire and sustain excessive proliferation in the context of cancer.

In this study, we focused on the poorly characterized SDS gene, DNAJC21. Using zebrafish, we generated the first in vivo model of Dnajc21 deficiency and showed that it accurately phenocopies salient features of SDS such as cytopenia, poor growth, and reduced protein synthesis. Consistent with the biallelic DNAJC21 loss reported in patients [13], our mutant fish were viable allowing characterization of both embryonic and adult hematopoiesis. Dnajc21 deficiency predominantly affected embryonic definitive hematopoiesis by downregulating the production of neutrophils and erythrocytes (Fig. 3). In addition to neutropenia, thrombocytopenia, and anemia are frequently reported in SDS patients [48], phenotypes which have not been recapitulated in previous animal models. Similarly, the kidney marrows of adult dnajc21 mutants exhibited neutropenia, lymphopenia, and excessive immature progenitors (Fig. 4D). Global protein synthesis was impaired and a poor bioenergetic profile defined by decreased ATP production was observed in our dnajc21 mutant zebrafish. Similar phenotypes have been observed in SBDS-mutant SDS models: SBDS-deficient yeast models show increased oxidative stress and mitochondrial dysfunction [10, 11] and SBDS-mutant primary lymphocytes have decreased ATP production resulting from complex IV dysfunction [46]. We found that Dnajc21 loss increased the levels of endogenous DNA damage as well as the sensitivity to γ-irradiation. This is in line with the S-phase arrest in cell cycle and the poor proliferation observed in these mutants. Hypersensitivity to DNA damaging agents is also seen SBDS-mutant SDS. Using Sbds-mutant mouse embryonic fibroblasts, Calamita et al. showed increased susceptibility to UV irradiation and chlorambucil treatment [49]. Radiosensitivity was observed in SBDS-mutant primary lymphocytes upon exposure to x-rays and γ-rays and was attributed to compromised DNA repair pathways [50]. We propose that a combination of the above-mentioned factors may explain the cytopenia observed in dnajc21-mutant SDS.

In addition to reduced neutrophil numbers, we found poor neutrophil recruitment following LPS exposure, suggesting impaired chemotaxis. The hematopoietic cytokine, G-CSF, is routinely used to treat patients with congenital neutropenia. It mobilizes HSPCs from the bone marrow and stimulates the production of neutrophils [51, 52]. The attenuated response to gcsf in dnajc21 mutants suggests dysfunctional hematopoietic progenitors that may be compromised in their capacity for gcsf-induced granulopoiesis.

Cytopenia in IBMFS has been attributed to both p53-dependent and independent mechanisms [53, 54]. In the case of dnajc21-mutant SDS, we found that introduction of the tp53 R217H mutation partially rescued both hypo-proliferation and neutropenia. Based on observations from mice carrying tp53 R248 mutations (analogous to tp53 R217) [39, 40], we suspect that mutant tp53 R217H dampens DNA damage responses and promotes cell cycle progression in the dnajc21 mutants. However, evaluation of kidney marrows showed worsening erythroid dysplasia and progenitor expansion in the dnajc21−/−/tp53R217H/R217H mutants compared to dnajc21−/− mutants (Fig. 4D). We speculate that Dnajc21 deficiency causes an MDS-prone state which then progresses to MDS in the presence of the tp53 mutation. The acquisition of additional maladaptive mutations may likely play a role in MDS pathogenesis since we only observed these phenotypes in a subset of dnajc21 mutant fish. Somatic compensation has been described in SBDS-mutant SDS, where the acquisition of somatic mutations in the SBDS binding partner, EIF6, ameliorates the underlying ribosomal defect [18]. We did not observe any changes in dnajc21 binding partners, pa2g4a and pa2g4b, at least at the mRNA level.

Analysis of transcriptomes and metabolomes from dnajc21 mutant embryos and kidney marrows identified alterations in a number of processes related to nucleotide metabolism. rrm2, which encodes a subunit of ribonucleotide reductase that catalyzes the synthesis of deoxyribonucleotides (dNTPs) from ribonucleotides (NTPs), was overexpressed in the dnajc21 mutants (Fig. 5A). RRM2 overexpression is seen in many cancers [41, 55] and is thought to provide an adequate dNTP supply to facilitate DNA repair thereby protecting from genotoxic stress [56], and to support excessive proliferation [57, 58]. We suspect that despite increased rrm2 levels, dnajc21 mutants are unable to overcome the replication stress from DNA damage due to the reduced availability of NTPs (Figs. 6,7). By externally supplying uridine or thymidine nucleosides, we were able to rescue neutropenia in the dnajc21 mutants. A similar mechanism was previously illustrated using zebrafish models of Diamond Blackfan anemia where exogenous nucleoside treatment alleviated DNA damage and improved hematopoiesis [59]. Recently, thymidine treatment was shown to effectively restore telomere lengths in induced pluripotent stem cells derived from dyskeratosis congenita patients [60]. Furthermore, thymidine is already being used in clinical trials for the treatment of thymidine kinase 2 deficiency (NCT03639701). Our study provides the first preliminary evidence for uridine and thymidine nucleosides in rescuing neutropenia in dnajc21-mutant SDS. Further studies including in mice and primary patient cells are required to determine drug dosing and pharmacokinetics.

In conclusion, we present for the first time, an animal model of dnajc21-mutant SDS that provides new insights into the cause of cytopenia in SDS. Our novel dnajc21/tp53 compound mutant represents a suitable animal model to evaluate pathways and interventions that can impede leukemia progression in SDS. Lastly, we provide preliminary evidence implicating pyrimidine metabolism in the SDS pathophysiology and show that nucleoside supplementation may be a viable therapeutic strategy for SDS.

Supplementary information

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by grants from the Leukemia and Lymphoma Society of Canada and Canadian Institutes of Health Research. Metabolomics studies were performed at the University of Ottawa Metabolomics Core Facility. This facility is supported by the Terry Fox Foundation and University of Ottawa. The authors would like to thank Dr. Shahrokh Ghobadloo, University of Ottawa Cellular Imaging and Cytometry Facility, and Dr. Vera A Tang, uOttawa Flow Cytometry & Virometry Core Facility for their guidance with flow cytometry experiments.

Author contributions

SK and JNB conceived the research study. SK designed and performed experiments analyzed data, and wrote the paper; SVP, AC, KB, SD, and SP generated and characterized the mutants; HH performed polysome experiments; MFL and EL performed histopathological analysis; MC, SAB, and IA performed metabolomics data analysis. TA, YD, and JNB supervised the research. SVP, HH, TA, MC, YD, and JNB reviewed and edited the manuscript.

Data availability

RNA sequencing data are available at GEO under the accession number GSE225613. Metabolomics data are shown in Supplemental Table 2.

Competing interests

JNB is on the advisory board of Oxford Immune Algorithmics.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41375-024-02367-8.

References

- 1.Farooqui SM, Ward R, Aziz M Shwachman–Diamond Syndrome. In: StatPearls. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2021. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK507866/. [PubMed]

- 2.Donadieu J, Leblanc T, Bader Meunier B, Barkaoui M, Fenneteau O, Bertrand Y, et al. Analysis of risk factors for myelodysplasias, leukemias and death from infection among patients with congenital neutropenia. Experience of the French Severe Chronic Neutropenia Study Group. Haematologica 2005;90:45–53. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Deschler B, Lübbert M. Acute myeloid leukemia: epidemiology and etiology. Acute Leukemias. 2008:47–56. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 4.Cesaro S, Pillon M, Sauer M, Smiers F, Faraci M, de Heredia CD, et al. Long-term outcome after allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation for Shwachman–Diamond syndrome: a retrospective analysis and a review of the literature by the Severe Aplastic Anemia Working Party of the European Society for Blood and Marrow Transplantation (SAAWP-EBMT). Bone Marrow Transpl. 2020;55:1796–809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Myers KC, Furutani E, Weller E, Siegele B, Galvin A, Arsenault V, et al. Clinical features and outcomes of patients with Shwachman–Diamond syndrome and myelodysplastic syndrome or acute myeloid leukaemia: a multicentre, retrospective, cohort study. Lancet Haematol. 2020;7:e238–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wong CC, Traynor D, Basse N, Kay RR, Warren AJ. Defective ribosome assembly in Shwachman–Diamond syndrome. Blood. 2011;118:4305–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Finch AJ, Hilcenko C, Basse N, Drynan LF, Goyenechea B, Menne TF, et al. Uncoupling of GTP hydrolysis from eIF6 release on the ribosome causes Shwachman–Diamond syndrome. Genes Dev. 2011;25:917–29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Austin KM, Gupta ML, Coats SA, Tulpule A, Mostoslavsky G, Balazs AB, et al. Mitotic spindle destabilization and genomic instability in Shwachman–Diamond syndrome. J Clin Investig. 2008;118:1511–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Orelio C, Verkuijlen P, Geissler J, Berg TK, van den, Kuijpers TW. SBDS expression and localization at the mitotic spindle in human myeloid progenitors. PLoS ONE. 2009;4:e7084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jensen LT, Phyu T, Jain A, Kaewwanna C, Jensen AN. Decreased accumulation of superoxide dismutase 2 within mitochondria in the yeast model of Shwachman–Diamond syndrome. J Cell Biochem. 2019;120:13867–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Henson AL, Moore JB, Alard P, Wattenberg MM, Liu JM, Ellis SR. Mitochondrial function is impaired in yeast and human cellular models of Shwachman–Diamond syndrome. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2013;437:29–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dhanraj S, Matveev A, Li H, Lauhasurayotin S, Jardine L, Cada M, et al. Biallelic mutations in DNAJC21 cause Shwachman–Diamond syndrome. Blood. 2017;129:1557–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tummala H, Walne AJ, Williams M, Bockett N, Collopy L, Cardoso S, et al. DNAJC21 mutations link a cancer-prone bone marrow failure syndrome to corruption in 60S ribosome subunit maturation. Am J Hum Genet. 2016;99:115–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shammas C, Menne TF, Hilcenko C, Michell SR, Goyenechea B, Boocock GRB, et al. Structural and mutational analysis of the SBDS protein family: Insight into the leukemia-associated Shwachman–Diamond syndrome. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:19221–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhang S, Shi M, Hui Cchung, Rommens JM. Loss of the mouse ortholog of the Shwachman–Diamond syndrome gene (Sbds) results in early embryonic lethality. Mol Cell Biol. 2006;26:6656–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tourlakis ME, Zhong J, Gandhi R, Zhang S, Chen L, Durie PR, et al. Deficiency of Sbds in the mouse pancreas leads to features of Shwachman–Diamond syndrome, with loss of zymogen granules. Gastroenterology. 2012;143:481–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Oyarbide U, Shah AN, Amaya-Mejia W, Snyderman M, Kell MJ, Allende DS, et al. Loss of Sbds in zebrafish leads to neutropenia and pancreas and liver atrophy. JCI Insight. 2020;5:134309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kennedy AL, Myers KC, Bowman J, Gibson CJ, Camarda ND, Furutani E, et al. Distinct genetic pathways define pre-malignant versus compensatory clonal hematopoiesis in Shwachman–Diamond syndrome. Nat Commun. 2021;12:1334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Xia J, Miller CA, Baty J, Ramesh A, Jotte MRM, Fulton RS, et al. Somatic mutations and clonal hematopoiesis in congenital neutropenia. Blood. 2018;131:408–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Heidemann S, Bursic B, Zandi S, Li H, Abelson S, Klaassen RJ, et al. Cellular and molecular architecture of hematopoietic stem cells and progenitors in genetic models of bone marrow failure. JCI Insight. 2020;5. Available from: https://insight.jci.org/articles/view/131018#SEC2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 21.White RM, Sessa A, Burke C, Bowman T, LeBlanc J, Ceol C, et al. Transparent adult zebrafish as a tool for in vivo transplantation analysis. Cell Stem Cell. 2008;2:183–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Westerfield M The zebrafish book. A guide for the laboratory use of zebrafish (Danio Rerio). 4th ed. Univ. of Oregon Press, Eugene.; 2000.

- 23.Prykhozhij SV, Cordeiro-Santanach A, Caceres L, Berman JN. Genome editing in zebrafish using high-fidelity Cas9 nucleases: choosing the right nuclease for the task. In: Sioud M, editor. RNA Interference and CRISPR technologies: technical advances and new therapeutic opportunities. New York, NY: Springer US; 2020. p. 385–405. (Methods in Molecular Biology). 10.1007/978-1-0716-0290-4_21. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 24.Thisse C, Thisse B. High-resolution in situ hybridization to whole-mount zebrafish embryos. Nat Protoc. 2008;3. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/18193022/. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 25.Schneider CA, Rasband WS, Eliceiri KW. NIH Image to ImageJ: 25 years of image analysis. Nat Methods. 2012;9:671–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Traver D, Paw BH, Poss KD, Penberthy WT, Lin S, Zon LI. Transplantation and in vivo imaging of multilineage engraftment in zebrafish bloodless mutants. Nat Immunol. 2003;4:1238–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rossmann MP, Hoi K, Chan V, Abraham BJ, Yang S, Mullahoo J, et al. Cell-specific transcriptional control of mitochondrial metabolism by TIF1γ drives erythropoiesis. Science. 2021;372:716–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sheehan HL, Storey GW. An improved method of staining leucocyte granules with Sudan black B. J Pathol Bacteriol. 1947;59:336–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Paik EJ, Zon LI. Hematopoietic development in the zebrafish. Int J Dev Biol. 2010;54:1127–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bertrand JY, Chi NC, Santoso B, Teng S, Stainier DYR, Traver D. Haematopoietic stem cells derive directly from aortic endothelium during development. Nature. 2010;464:108–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bursac S, Brdovcak MC, Donati G, Volarevic S. Activation of the tumor suppressor p53 upon impairment of ribosome biogenesis. Biochimica Biophysica Acta. 2014;1842:817–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gong L, Gong H, Pan X, Chang C, Ou Z, Ye S, et al. p53 isoform Δ113p53/Δ133p53 promotes DNA double-strand break repair to protect cell from death and senescence in response to DNA damage. Cell Res. 2015;25:351–69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Aoubala M, Murray-Zmijewski F, Khoury MP, Fernandes K, Perrier S, Bernard H, et al. p53 directly transactivates Δ133p53α, regulating cell fate outcome in response to DNA damage. Cell Death Differ. 2011;18:248–58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Prykhozhij SV, Fuller C, Steele SL, Veinotte CJ, Razaghi B, Robitaille JM, et al. Optimized knock-in of point mutations in zebrafish using CRISPR/Cas9. Nucleic Acids Res. 2018;46:e102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Genovese G, Kähler AK, Handsaker RE, Lindberg J, Rose SA, Bakhoum SF, et al. Clonal hematopoiesis and blood-cancer risk inferred from blood DNA sequence. N. Engl J Med. 2014;371:2477–87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wong TN, Miller CA, Jotte MRM, Bagegni N, Baty JD, Schmidt AP, et al. Cellular stressors contribute to the expansion of hematopoietic clones of varying leukemic potential. Nat Commun. 2018;9:455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Jaiswal S, Fontanillas P, Flannick J, Manning A, Grauman PV, Mar BG, et al. Age-related clonal hematopoiesis associated with adverse outcomes. N. Engl J Med. 2014;371:2488–98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chen S, Wang Q, Yu H, Capitano ML, Vemula S, Nabinger SC, et al. Mutant p53 drives clonal hematopoiesis through modulating epigenetic pathway. Nat Commun. 2019;10:5649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hanel W, Marchenko N, Xu S, Yu SX, Weng W, Moll U. Two hot spot mutant p53 mouse models display differential gain of function in tumorigenesis. Cell Death Differ. 2013;20:898–909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Song H, Hollstein M, Xu Y. p53 gain-of-function cancer mutants induce genetic instability by inactivating ATM. Nat Cell Biol. 2007;9:573–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Aye Y, Li M, Long MJC, Weiss RS. Ribonucleotide reductase and cancer: biological mechanisms and targeted therapies. Oncogene. 2015;34:2011–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rashkovan M, Ferrando A. Metabolic dependencies and vulnerabilities in leukemia. Genes Dev. 2019;33:1460–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.de Beauchamp L, Himonas E, Helgason GV. Mitochondrial metabolism as a potential therapeutic target in myeloid leukaemia. Leukemia. 2022;36:1–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Mullen NJ, Singh PK. Nucleotide metabolism: a pan-cancer metabolic dependency. Nat Rev Cancer. 2023;23:275–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Darzynkiewicz Z, Halicka HD, Zhao H, Podhorecka M. Cell synchronization by inhibitors of DNA replication induces replication stress and DNA damage response: analysis by flow cytometry. Methods Mol Biol. 2011;761:85–96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ravera S, Dufour C, Cesaro S, Bottega R, Faleschini M, Cuccarolo P, et al. Evaluation of energy metabolism and calcium homeostasis in cells affected by Shwachman–Diamond syndrome. Sci Rep. 2016;6:25441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sen S, Wang H, Nghiem CL, Zhou K, Yau J, Tailor CS, et al. The ribosome-related protein, SBDS, is critical for normal erythropoiesis. Blood. 2011;118:6407–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Furutani E, Liu S, Galvin A, Steltz S, Malsch MM, Loveless SK, et al. Hematologic complications with age in Shwachman–Diamond syndrome. Blood Adv. 2022;6:297–306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Calamita P, Miluzio A, Russo A, Pesce E, Ricciardi S, Khanim F, et al. SBDS-deficient cells have an altered homeostatic equilibrium due to translational inefficiency which explains their reduced fitness and provides a logical framework for intervention. PLoS Genet. 2017;13:e1006552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Morini J, Babini G, Mariotti L, Baiocco G, Nacci L, Maccario C, et al. Radiosensitivity in lymphoblastoid cell lines derived from Shwachman–Diamond syndrome patients. Radiat Prot Dosim. 2015;166:95–100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Panopoulos AD, Watowich SS. Granulocyte colony-stimulating factor: molecular mechanisms of action during steady state and ‘emergency’ hematopoiesis. Cytokine. 2008;42:277–88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Liongue C, Hall CJ, O’Connell BA, Crosier P, Ward AC. Zebrafish granulocyte colony-stimulating factor receptor signaling promotes myelopoiesis and myeloid cell migration. Blood. 2009;113:2535–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Provost E, Wehner KA, Zhong X, Ashar F, Nguyen E, Green R, et al. Ribosomal biogenesis genes play an essential and p53-independent role in zebrafish pancreas development. Development. 2012;139:3232–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Oyarbide U, Topczewski J, Corey SJ. Peering through zebrafish to understand inherited bone marrow failure syndromes. Haematologica. 2019;104:13–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Zhan Y, Jiang L, Jin X, Ying S, Wu Z, Wang L, et al. Inhibiting RRM2 to enhance the anticancer activity of chemotherapy. Biomedicine &. Pharmacotherapy 2021;133:110996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Lin ZP, Belcourt MF, Carbone R, Eaton JS, Penketh PG, Shadel GS, et al. Excess ribonucleotide reductase R2 subunits coordinate the S phase checkpoint to facilitate DNA damage repair and recovery from replication stress. Biochemical Pharmacol. 2007;73:760–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Ward PS, Thompson CB. Metabolic reprogramming: a cancer hallmark even Warburg did not anticipate. Cancer Cell. 2012;21:297–308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Elford HL, Freese M, Passamani E, Morris HP. Ribonucleotide reductase and cell proliferation. I. Variations of ribonucleotide reductase activity with tumor growth rate in a series of rat hepatomas. J Biol Chem. 1970;245:5228–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Danilova N, Bibikova E, Covey TM, Nathanson D, Dimitrova E, Konto Y, et al. The role of the DNA damage response in zebrafish and cellular models of Diamond Blackfan anemia. Dis Model Mech. 2014;7:895–905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Mannherz W, Agarwal S. Manipulation of thymidine nucleotide metabolism controls human telomere length and promotes telomere elongation in dyskeratosis congenita patient derived cells. Blood. 2022;140:988–9. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

RNA sequencing data are available at GEO under the accession number GSE225613. Metabolomics data are shown in Supplemental Table 2.