Abstract

(−)-Epigallocatechin-3-gallate (EGCG) is reported to have benefits for the treatment of Alzheimer’s disease by binding with acetylcholinesterase (AChE) to enhance the cholinergic neurotransmission. Organophosphorus pesticides (OPs) inhibited AChE and damaged the nervous system. This study investigated the combined effects of EGCG and OPs on AChE activities in vitro & vivo. The results indicated that EGCG significantly reversed the inhibition of AChE caused by OPs. In vitro, EGCG reactived AChE in three group tubes incubated for 110 min, and in vivo, it increased the relative activities of AChE from less than 20% to over 70% in brain and vertebral of zebrafish during the exposure of 34 h. The study also proposed the molecular interaction mechanisms through the reactive kinetics and computational analyses of density functional theory, molecular docking, and dynamic modeling. These analyses suggested that EGCG occupied the key residues, preventing OPs from binding to the catalytic center of AChE, and interfering with the initial affinity of OPs to the central active site. Hydrogen bonding, conjugation, and steric interactions were identified as playing important roles in the molecular interactions. The work suggests that EGCG antagonized the inhibitions of OPs on AChE activities and potentially offered the neuroprotection against the induced damage.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41598-024-72637-z.

Keywords: (−)-Epigallocatechin-3-gallate, Organophosphorus insecticides (OPs), Acetylcholinesterase, Antagonism, Neuroprotection

Subject terms: Biochemistry, Neuroscience, Environmental sciences

Introduction

(−)-Epigallocatechin-3-gallate (EGCG) is the main and most significantly bioactive polyphenol found in solid green tea extract. Studies showed EGCG was one of the rare natural compounds to be benefit for the treatment of Alzheimer’s disease1,2. This compound has important protective effects against neuronal damage and brain edema as well as anti-inflammatory and antiatherogenic properties. EGCG consists the polyhydroxy structure with eight hydroxyl groups (- OH) and three aromatic rings. The unique structure is responsible to be affinity with AChE through forming hydrogen bond to impact the behavior of AChE3,4. By the silico analysis, Ali B, et al. reported that EGCG could be as reversible inhibitors of AChE to enhance the cholinergic neurotransmission in Alzheimer’s disease treatment5. The amount of energy for EGCG bond with AChE was lower to about − 14.45 kcal·mol− 1, and nineteen amino acids residues were involved in. The inhibition constant for EGGC was 10.69 nM in case of AChE. Kiziltas, H., et al. further reported EGCG bond with AChE at eight residues of Asp 72, Asn 85, Gly 117, Try 121, Ser 122, Tyr 130, Ser 200, and His 440 with the energy of -10.0 kcal·mol− 16. Though the multiple neuroprotective efficacies of EGCG are reported focusing on the involvement of αβ- evoked damage and αβ- regulation, inhibition of tauphosphorylation, anti-oxidation, anti-inflammation, and anti-apoptosis7,8, EGCG promots Ach content by diminishing the activity of AchE has been reported9. Moreover, EGCG can assist other compounds in exerting their effects in the treatments. Ali AA, et al. and Wei B -b, et al. demonstrated that EGCG passed blood brain barrier and combined with Vinpocetine performing the pronounced neuroprotective effects in ameliorating aluminum chloride-induced Alzheimer’s disease in rats10,11. Huperzine A is mainly identified from Huperziaceae plants, and has been exploited for the treatment of Alzheimer’s disease with long effects and remarkable stability through the reversible inhibition to AChE12,13. The investigation by Zhang L, et al. indicated that EGCG enhanced the effect of huperzine A on inhibiting AChE and largely prolonged the inhibitory time though by itself hardly inhibits the AChE activity within the range from 10 to 300 mg·kg− 114. AChE is also reported to be the important target of the nerve agents of organophosphorus compounds (OPs) in cholinic nerves15. Mostafalou, S. & Abdollahi, M. reviewed the susceptibility of humans to neurodegenerative and neurodevelopmental toxicities caused by OPs16. OPs inhibit the activities of cholinesterase (ChE) enzymes which AChE is the important one in. The inhibitions have been linked to an increased risk of neurological disorders, including neurodegenerative and neurodevelopmental diseases. Chlorpyrifos is an organophosphorus pesticide that is extensively applied in the field or garden. The exposures to Chropyrifos damage cholinergic transmission and AChE variant alterations, resulting in cell death of basal forebrain cholinergic neurons which are involved in learning and memory regulation17. A consistent feature of Alzheimer’s disease is the dysfunction of basal forebrain cholinergic neurons which is important contributing to dementia and memory disorders18. As the critical OPs toxicology has always been reported to be the cholinergic disruption, to revers AChE is a target to relieve the neurological symptoms induced by OPs in the treatment of Alzheimer’s disease15,19,20. However, the effects of EGCG on the inhibition of AChE by OPs were unclear.

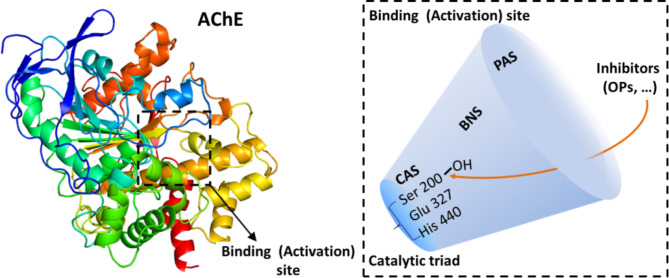

Organophosphorus compounds (OPs), pesticides or ‘nerve agents’, damage AChE causing the death, or the impaired physiological activities, which are the potential risk in ecosystem and public health15,21. Both chronic and acute poisoning by OPs can leave long-lasting health effects including the risk of Alzheimer’s disease20, even when the patients are treated with standard medical therapy22,23. Furthermore, the standard therapy to react AChE is treated by oximes with the serious side-effects, no penetration through blood brain barrier, and low broad-spectrum24,25. OPs are generally regarded to result in a rapid phosphylation of the catalytic center of AChE (Sketch 1) through targeting the hydroxyl group (-OH) on serine 200, thereby inhibiting hydrolysis of the transmitter acetylcholine, and hence disturbing cholinergic transmission26–28. Though that OPs misadjust the gens inducing the physiological defects and cell damage has been reported29,30, the irreversible phosphylation is recognized to be one of the main mechanism on the poisoning of OPs31,32. The targeting process involves four steps, i.e. the affinity to AChE, the formation of stable covalent bond for phosphorylation, the hydrolysis reaction, and the aging of phosphorylation causing permanent inhibition of the enzyme. The AChE activities are indicated by the magnitude of kinetic constants for the capability to hydrolyze choline33,34. The molecular interactions of OPs and AChE have been simulated by the computational in recent years though experiments in vitro & vivo demonstrated the bio-toxic. AChE is reported to pose two binding-sites in a deep and narrow gorge, referred to as the ‘active site gorge’ with about 5 Å wide and 20 Å deep. OPs phosphylates Serine situated at the “anionic” sub-site of center active site (CAS) in the gorge. CAS, locates near the bottom of the gorge, contains a catalytic triad (His440-Glu327-Ser200) and a key aromatic residue, Trp 84 35. Čadež T, et al. simulated four OPs docking to AChE, and reported phosalone and fenamiphos were positioned near the catalytic Ser 203, and created the hydrogen bond with Ser 203. Trp 86 located at the choline binding site also creates interactions with pesticides37. Reyes-Espinosa F, et al. modeled the binding of forty compounds of OPs with AChE for the associated point mutations of the resistance by the computational33. The modeling presented a hydrogen bond between Ser 297 and oxygen from OPs. The report proposed the deduction on an inadequate steric interaction that prevents a phosphorylation reaction.

Sketch 1.

The activation and inhibition sites of acetylcholinesterase (AChE).

There is another binding-site, the peripheral “anionic” site (PAS). PAS is close to the entrance of the active-site gorge, and Trp279 is an important component. Besides, in the middle of the gorge, a bottleneck as an open-shut-door is formed mainly by the side-chains of Phe330 and Tyr121 36. Because AChE has two binding sites (so called the bivalent fashion), many compounds with dual binding site have been selected and tested to reverse the inhibited AChE when AChE was poisoned. Eckert S, et al. afforded the reversible inhibitors, physostigmine, pyridostigmine and huperzine A, to protect AChE from the irreversible inhibition of OPs in vitro and observed the pre-protection39. As a natural compound with the neuroprotective and excellent antioxidative, the effects of EGCG on the toxic of OPs are much focused on through regulating antioxidant factors. Biasibetti R, et al. and Zhao Y, et al. reported EGCG antioxidated the oxygen stress of OPs to protect AChE through the modulation of the genes expression40,41. Zhang L, et al. indicate the enhancement and complementary effects of EGCG on huperzine A activity were partly be due to the antioxidant property of EGCG14. However, it is unclear whether EGCG bind to the catalytic center through more than one site, and the directly interacts with OPs and AChE through the molecule interactions to affects the damage of OPs on AChE .

The combined effects of EGCG with OPs on AChE activities and the molecular interactions mechanism were rarely reported, especially for the systematically empirical data in vitro, in vivo of zebrafish, and by the computational. In this work, three organophosphorus pesticides, chlorpyrifos, dichlorvos, and malathion, which are used extensively, were selected as the inhibitors to AChE. The batch incubations of three groups in vitro were conducted to identify the resistant effects of EGCG to OPs. The adult zebrafish was chosen to be the model animals to investigate the antagonisms of EGCG in vivo through two group exposures. The interactions mechanism of EGCG, OPs and AChE were deduced by the first-order kinetics and the computational of Density Function Theory (DFT) calculating, molecules docking, and dynamics simulating. The work analyzed the results and attempted to propose the further protection of choline nerves by EGCG.

Experiments

Chemicals and materials

Epigallocatechin-3-gallate (EGCG, ≥ 97.0%), chlorpyrifos (CPF, ≥ 98.0%), dichlorvos (DDVP, ≥ 98.5%), malathion (MAL, ≥ 97.0%) were purchased from Sigma Aldrich Co. (Rockville, MD, USA). AChE (Electrophorus electricus, 220 U·mg − 1 ) was obtained from Leaf Biology Co. (Shanghai, China). Dinitrobenzoic acid (DTNB) and acetylcholine iodide (ATChI, substrate) were purchased from Meryer and Macklin (Shanghai, China). TRIzol® reagent was from Thermo Fisher Scientific Co. (Waltham, MA, USA). All the routine chemicals and solvents were of analytical grade and supplied by Tianjin Chemical Company (Tianjin, China). Kits for detection of AChE and protein were purchased from Nanjing Jiancheng Bioengineering Institute (Nanjing, Jiangsu, China). Kits for genes express abundance were purchased from Applied Biosystems Co. (Foster City, CA, USA).

Tests in vitro

Incubation

OPs was dissolved independently by acetonitrile and EGCG was dissolved by deionized water to prepare 0.5 mmol mL− 1 solvents as the storage solvents and was set at 4 ℃ for further diluted. Then, OPs solutions were gradually diluted by solvents of delionzed water and acetoiril (1:1, v: v) to be 0.11, 0.0018, and 0.06 mmol mL− 1 solvents for CPF, DDVP, and MAL, respectively. EGCG was diluted by deionized water to be the concentration of 0.11 mmol mL− 1. Phosphate buffer (0.1 M, pH 7.5) dissolved the compounds to prepare 0.1 U·mL− 1 of AChE, 4.8 mmol·mL− 1 of ATChI, and 3.2 mmol·mL− 1 DTNB, respectively.

The incubation was referred to Ellman method reported by Worek, F et al.42,43. Three groups of incubations were conducted, i.e. that EGCG presented synchronous (Syn.) with OPs, or 15 min before (Pre.) or behind (Post.) OPs (Scheme 1) in the reaction with AChE .

Scheme 1.

The reaction scheme for the incubation of EGCG combined with OPs in vitro (Det., chromogenic reactions detection).

According to Scheme 1, 5 µl OPs, 5 µl EGCG, 5 µl AChE and 20 µl DTNB were added into the tube with 715 µl phosphate buffer to be mixed. The total volume of reaction solution was 750 µl. The final incubation concentrations were 73.0, 1.25, and 40.0 µmol·L− 1, for CPF, DDVP, and MAL, respectively. The concentration of EGCG was according to the ratio to OPs from 5:1 to 1:5 (µmol·L− 1: µmol·L− 1). The final incubation concentrations were 6.4 µmol·L− 1 for AChE. The final concentration of acetonitrile in the incubation cell was lower than 1.0%. The 1.0% acetonitrile was tested to observe, and the results indicated there were no effects on the incubation. The incubations with 1.0, 10.0, 20.0. 30.0% acetonitrile were observed, respectively, before the preparation of the storage solvents of OPs in the beginning of tests. The results indicated that there were also no effects on the determination of activities of AChE.

Then, 180 µl of the reaction solutons was added into the pores of 96-pore plate and incubation (Scheme 1), After incubation, 32 µmol·L− 1 of the final concentration ATChI as substrate, and 100.0 µmol·L− 1 of the final concentration DTNB as chromogenic reagent were added the pores containing the 180 µl reaction solution to react for 2 min. The solutions in the pores were detected by Microplate reader (Varioskan LUX, Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc.) and the detective absorbance was at 412 nm. The blank and controls for independent OPs or EGCG were tested. All the incubations were three replicates. The reversal rate (Rrev., %) of EGCG were calculated.

IC50 of OPs and EC50 of EGCG

According to th modified Ellman assay43 and the Kits guiding for use (Jianchen, Nanjiang, China), solutions of varied concentrations of pesticides were incubated with AChE for 30 min at 37 ℃ to calculate IC5028. The concentration of 25 ~ 95, 0.75 ~ 7.5, and 30 ~ 150 µmol·L− 1 was for CPF, DDVP, and MAL, respectively. The calculated IC50 of OPs was used as the concentration in the combination incubation to assured that the AChE activity was about 50%. The relative activities of AChE were determined at the concentration ratios of EGCG to OPs was ranged from 5:1 to 1:5 (µmol·L− 1: µmol·L− 1) in 2, 5, 10, 20, 40, 70, 110 min. EC50 were calculated according to dose of EGCG and values of Rrev. Effects of EGCG from 1.0 to 200.0 µmol·mL− 1 on AChE activities were also determined.

The observed reaction kinetics

The hydrolysis velocity of ATChI was evaluated by the observed first- order kinetics reaction constants (kobs.) through the determining the chromogenic reactions according to Ellman assays44. After the incubation and addtions of substrate of ATChI and chromogenic reagent of DTNB. The adsorptions of the solutions in pores were detected at 0.5, 1.0, 1.5, 2.0, 2.5 min. Then, the observed reaction kinetics constants (k obs.) were calculated as the formula followed.

Experiments in vivo

Ethics statement

The research complied with the ARRIVE guidelines (PLoS Bio 8(6), e1000412, 2010) and followed the American Veterinary Medical Association (AVMA) Guidelines for the Euthanasia of Animals (2020). All zebrafish protocols and experiments were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committees (IACUC) of Anhui Agricultural University (Approved number: AHAUB23025), which are accredited by Anhui Agricultural University. The approval was in accordance with Laboratory animal - Guideline for ethical review of animal welfare published in China.

The number of fish was preplanning according to the experiments. The emergency plan for zebrafish (Danio rerio) to be euthanized is the rapid chilling as described in the ‘Guidelines for the Euthanasia of Animals’.

Animal husbandry

Previous studies have shown that zebrafish is one of the model animals in researches on toxic of OPs and the behavior of AChE exposred by chemicals41,45,46. Mixed-sex adult zebrafish (Danio rerio) (4–5 months old) were purchased from aquarium (Hefei, China), and maintained in a standalone system according to published guidelines. Briefly, fish were maintained in 20 L transparent rectangular tanks equipped with white filter, light, ventilation device and thermostat. The deionized water supplemented with E3 medium (2 mL 60X E3 per 5 L of deionized water) (60X E3 media containing 0.595 M NaCl, 0.021 M KCl, 0.039 M CaCl2·2H2O, and 0.048 M MgCl2·6H2O and pH 7.2) was used for the fish maintenance. Tanks were under the conditions of 24 ± 2 °C, 14 h light and 10 h dark. Fish were manually fed ad libitum twice-a-day with commercial pellet based diet. The excess of food or fish waste were removed using the filter or siphon. Fish underwent 7-day period of adaptation before the experiment.

Exposures and sampling

Exposures: LC50 detection

LC50 of OPs to zebrafish was assessed within 72 h. The doses were 1.4 ~ 2.8, 90.0 ~ 180.0, and 10.0 ~ 40.0 µmol·L− 1 of CPF, DDVP, and MAL, respectively, according to the references46–48. EGCG of 1.0 ~ 200.0 µmol·L− 1 was also tested independently. Six fish were exposed to chemicals according to 203 for testing chemicals (OECD, 1992). The dead fish were immediately removed from the aquaria. Fish in water were as controls. Treatments: (1) enzyme source. The independent compounds or the combination of EGCG and OPs were exposed to the adult zebrafish. The treatments concentrations of OPs were basically according to the values of LC50. The combined concentration of EGCG was equal to OPs (1:1, µmol·L− 1: µmol·L− 1). Sixteen fish were treated by the single-dose in two groups of Continuous and Separation in the glass tanks of 20 × 20 × 20 cm. In the Continuous group, fish were exposed to the combined EGCG with OPs in the same tank for 34 h. In the Separation group, fish were exposed to OPs for 2 h, and then, transported into a new tank in which the exposure solution contained EGCG to finish the next test of 34 h. (2) Gene expression abundance (GEA). Zebrafish were exposed to the combination of OPs and EGCG for 5 days. Eight fish were in a bank for exposures. The concentrations of OPs were 0.15, 0.60, and 1.8 µmol L− 1 for CPF, DDVP, and MAL, respectively. The concentration ratio of EGCG to OPs was 2:1 and 1:1 (µmol L− 1: µmol L− 1.). In all exposures, fish in water were as blank, and treated by OPs or EGCG independently were as controls. All treatments were two replicates.

Sampling: enzyme source

The sources of AChE for the determination of the relative activities followed the reference reported45. Two of Zebrafish were sampled at 3, 6, 12, 24, 34 h, respectively, and The tissues of brain (H-) and vertebra (V-) were dissected and accurately weighed. The tissues were subsequently homogenized in 2 ml pore of 48 pores plate with the cold saline (4 °C, 0.1 g of tissue to 0.9 mL of aqueous) at 1500 rpm for 2 min (CK1000, Thmorgan, Beijing, China). Then, samples were centrifuged at 3000 g in 4 ºC for 10 min (Biofuge Stratos, Thermo Scientific Co., USA). The supernatant was separated and employed as an enzyme source.

GEA

Extract the total RNA according to the method reported by Awoyemi O.M., et al.49. The tissues were homogenized with 500 µL Trizol® reagent (Life technologies, Carlsbad, CA, USA) in 1.5 mL tubes. Then, 100 µL chloroform: isoamyl alcohol (24:1, V: V) was added into the tubes for phase separation. The mixture was centrifuged at 15,000 g for 10 min at 4 °C after mixed gently by inverting the tube. The supernatant was introduced into new 1.5 mL tube containing 500 µL isopropanol, and centrifuged at 10,000 g, for 10 min at 4 °C. The mRNA extract was cleaned twice with the addition of 75% cold ethanol, centrifuged at 7500 g, for 5 min at 4 °C, the ethanol was decanted, and the mRNA pellet was dissolved in 50 µL of ultra-pure™ distilled water. The total mRNA concentration and purity was assessed using Nanodrop 2000 spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Wilmington, MA, USA) and mRNA solution was stored at − 80 °C until further analysis.

Assay of AChE activities, and GEA in vivo

AChE activities

The relative activities of AChE were monitored with a modified Ellman assay43 by Kits (Jianchen, Nanjiang, China). All experiments were performed at 37 ℃ temperature. Total protein was measured by the Coomassie blue method by Kits (Jianchen, Nanjiang, China)44. The samples were detected by the spectrophotometer (UV 1800, Shimadzu, Japan).

GEA

The High capacity cDNA preparation Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Carlsbad, CA, USA) was used for cDNA synthesis. An aliquot of 200 ng of the total mRNA was prepared and used as a template to synthesize the cDNA in a 10 µL reaction mixture containing 10× RT buffer, 25× dNTP mix, 10× RT random primers, reverse transcriptase MultiScribe RT. The cDNA synthesis was performed on a Veriti 96 well Fast Thermal Cycler (Applied Biosystems, Foster city, CA, USA). Gene-specific primer sequences (Supplementary material, S 1) were purchased from Novizan Co. (Nanjing, China). To determine the gene expression abundance, 1 µL cDNA was added by 8 µL of Fast SYBR Green I Kit (Qiagen, German), 1 µL each of reverse and forward primer, and 10.8 µL of ultra-pure water. The RT-qPCR was performed on Applied Biosystems QuantStudio 3 Real-Time PCR System (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). The RT-qPCR conditions consisted of initial polymerase activation at 95 °C for 15 s, followed by 40 cycles of alternating denaturation at 95 °C for 30 s, and annealing at 55 °C for 30 s. After the 40 cycles, a melt curve analysis was performed with fluorescence measure from 95 °C to 55 °C. The threshold cycle (ct) value was also obtained by QuantStudio 3 Real-Time PCR System. Relative fold change in gene expression was determined according to the methods described by Livak and Schmittgen50,51, using β-actin as the reference gene.

Calculation, modeling and statistics

Reversal rate calculation

The reversal rate (Rrev., %) of EGCG against to OPs was calculated according to Formula 1

|

1 |

Where,  was the relative activity of AChE incubated with the combination of EGCG and OPs,

was the relative activity of AChE incubated with the combination of EGCG and OPs,  was the relative activity of AChE incubated with OPs independently.

was the relative activity of AChE incubated with OPs independently.

IC50 and EC50

IC50 and EC50 were calculated according to the respond-growth of software of Origin 9.1 (https://www.originlab.com/).

The observed reaction kinetics constants (kobs.)

The modeling of the observed first-order kinetics was shown as Formula 2. ‘kobs.’ was calculated to evaluate the reactions velocity.

|

2 |

Where, Ct was the concentration of Choline, C0 was the initial concentration of Choline, kobs was the kinetics constants, t was the reactive time.

Computational and dynamic simulation for molecular interactions

(1) Molecular docking. Molecular dynamic simulations were performed using Gromacs 5.1.5 program52. (2) Computational dynamic simulation. The complex of EGCG- AChE, OPs- AChE, OPs- EGCG- AChE were simulated in the constructed system. The system consisted of: (i) the ligand-receptor complex, which was solved using TIP3P waters53; (ii) Na + and Cl− ions neutralizing the system; and (iii) periodic boundary conditions with a minimal distance of 1.0 Å between the protein and the edge of the box. The methods of simulation and energy calculation were seen in Supplementary material (S 2). (3) Density functional theory. The density functional theory (DFT) calculations were performed under B3LYP –D3/6 -31G ** method.

Statistics

The statistics was performed through t-test with the mean and standard deviation from the control group and exposure group. The results was demonstrated by the statistically significant different with p-value < 0.05.

Results and discussions

Reversal of AChE inhibition by EGCG in vitro

Molecules docking and DFT calculation deducted that EGCG was had the ability to compete with OPs taking advantageous to affinity the catalytic center. The observed hydrolysis kinetics of AChE confirmed the calculation deductions.

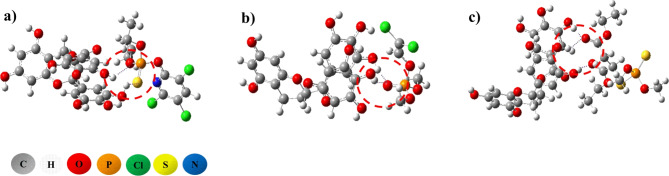

Molecules docking indicated that four compounds can bind to catalytic center in the active cavity of the AChE, and combine with the formation of the hydrophobic bond. Furthermore, EGCG, CPF and MAL formed hydrogen bond interacting with the amino acids around the pocket where the active cavity sited. The binding energy to catalytic center of AChE was − 10.231 kcal·mol− 1 for EGCG, which was significantly lower than − 7.201,-5.371, and − 7.063 kcal·mol− 1 for CPF, DDVP and MAL, respectively (Fig. 1 I-IV). Flavonoids has been reported recently to bind with AChE reversely. Ahmad, V. et al. reported recently that Taxifolin combine with AChE by − 8.85 kcal·mol− 1 through MD, and the main interactions are hydrogen bonds, Van der Waals and others54. The results were corresponded with that of EGCG. OPs were also modeled to combine with AChE, and MD was simulated for CPF and paraoxon by − 6.5 and − 6.7 kcal·mol− 1, respectively55. DFT calculations demonstrated that EGCG could combine with OPs by hydrogen bonds forming the complexes (Fig. 2a-c). The energies were − 27.43, − 25.36 and − 30.13 kcal·mol− 1 for EGCG binding to CPF, DDVP and MAL, respectively. The formation of complexes might disturb the combination of OPs with AChE or intercept the immigration of OPs to AChE.

Fig. 1.

Molecular docking of four compounds to the catalytic center of AchE. (I) EGCG, (II) CPF, (III) DDVP, (IV) MAL. (a) Combination of compound with protein of AChE, (b) compound on the surface of active site of AChE, (c) 2-D map of molecular interaction, (d) 3-D map of molecular interaction.

Furthermore, the velocity for AChE to hydrolyze ATChI in the present of EGCG was higher than that of OPs. The hydrolysis conformed to the first-order kinetics during the first 3 min reactions. The kinetic constants (kobs) for AChE reflected the magnitude of hydrolysis velocity. kobs introduced by EGCG were higher than that by OPs showed that EGCG improved the hydrolysis velocity for AChE in vitro (Fig. 3I). Meanwhile, the observed hydrolysis reactions testified that AChE was the anchored enzyme.

Fig. 2.

Complex for EGCG combined with OPs and hydrogen bonds (purple in the red circle) deducted by DFT (a, b, and c were for CPF, DDVP and MAL, respectively).

The investigations in three group incubations indicated that EGCG reversed the AChE activities and restored the inhibited AChE by OPs in vitro. In order to acquire the incubation concentrations in vitro, IC50 of the pesticides was tested and the calculated values were corresponding to the previous reports (Table 1)56–58. EGCG performed the reversible- noncompetitive inhibition (S 3) and the relative activities of AChE were 58.23 ± 15.03% by EGCG as the reversible inhibitor with concentration from 1.0 to 200 µmol·L− 1. When the incubations were treated with IC50 of OPs, the maximum reversal rates (Rrev.) of EGCG to the inhibited AChE was 88.06 ± 4.8%, 95.14 ± 11.4% and 67.19 ± 1.61% for CPF, DDVP, and MAL, respectively (Table 1). Figure 3II showed the average relative activities of AChE and the corresponded reversal rates in three group incubations. EGCG exhibited more obvious antagonism towards DDVP compared to the other two pesticides, while the differences in antagonism levels were insignificant within the groups. The values of EC50 cal. were calculated after five concentration ratios of EGCG to OPs were treated in the combined incubations considering the dose effects (Table 1). The peaks of ‘Rrev.’ were observed at the time from 20 to 60 min during the time-kinetic effects of 110 min (Fig. 3III). It was note the resistant for EGCG to OPs was obvious to the dose and chemical specific. The doses of EGCG with equal and double the concentration of OPs have the optimal effects, which was rather than the increase of absolute concentration. Meanwhile, EGCG has the most significant effects to DDVP and the lowest to MAL in the three pesticides when the dose of EGCG was applied at the optimal effects (Fig. 3III).

Table 1.

The maximum reversal rates (Rrev.max, %) in three group incubations and the calculated EC50 of EGCG in vitro (ρ < 0.05) .

| Compounds (IC50/µmol·L− 1) | Pre. | Syn. | Post. |

|---|---|---|---|

| Rrev.max/% | |||

| CPF (73.0) | 47.03 ± 2.64 | 84.06 ± 4.8 | 63.99 ± 5.65 |

| DDVP (1.25) | 86.34 ± 1.06 | 92.14 ± 3.14 , | 62.59 ± 4.87 |

| MAL (40.0) | 10.99 ± 8.80 | 67.19 ± 1.61 | 37.35 ± 8.81 |

| EC50 /µmol·L− 1 | |||

| CPF | – | 33.34 ± 5.25 | 122.62 ± 29.69 |

| DDVP | 0.38 ± 0.17 | 1.18 ± 1.5 | 0.62 ± 0.18 |

| MAL | – | 45.63 ± 37.60 | – |

–: the reversal rates were lower than 50%.

Resistant in brain and vertebra of adult zebrafish

EGCG improving the inhibited-AChE were observed in brain and vertebral of zebrafish exposed in two group exposures of 34 h. LC50 investigated in 72 h were 1.71, 135.8 and 30.3 µmol·L− 1 for CPF, DDVP and MAL, respectively, which basically corresponded to the reports46,47,49. EGCG did not lead to the death of zebrafish during 96 h exposed to concentration from 1.0 to 200.0 µmol·L− 1. When zebrafish were exposed to LC50 of pesticides, AChE was inhibited obviously. The average relative activities of AChE during 34 h were from 10.83 ± 9.27 to 28.64 ± 11.32% for brain and 11.45 ± 7.02 to 31.56 ± 13.76% for vertebra. EGCG performed the reversible- noncompetitive inhibition by 67.76 ± 11.27% of the relative activities of AChE.

However, the inhibited-AChE by OPs was restored by the intervention of the equal concentration of EGCG. The average values of Rrev were 94.00 ± 25.97% for CPF, 125.79 ± 36.71% for DDVP, and 20.28 ± 9.34 for MAL, respectively. Figure 4 displayed the relative activities of AChE when the maximum reversal occurred in brain (Fig. 4a) and vertebral (Fig. 4b). The antagonism in brain was more effective than in vertebral as well as in group of separation than of continuous. The antagonism was also depended on the compounds, which the most significant improvements were observed for EGCG to resist DDVP in the three OPs compounds. EGCG could increase the relative activities of AChE from 24.45 ± 6.24% to 76.82 ± 8.92% in brain during the exposure of 6 h to DDVP. The maximum Rrev was 278.76 ± 16.84% in brain and 152.36 ± 12.28% in vertebra of zebrafish exposed to DDVP. EGCG exhibited fair reversal effects for CPF and the lowest effects for MAL in the three pesticides, which followed the similar sequence to the incubation in tubes. The observation of kinetic reversal indicated that the resistant could perform at least 34 h after the single dosage intervention of EGCG. Most reversals were observed to reach the peaks from 3 to 12 h in the exposures.

Fig. 3.

The resistant of EGCG against OPs on situ in vitro (*, the value of ρ). (I) the observed kinetics constants (k obs) of reactions for AchE to hydrolyze ATChI in incubation. (II) The average relative activities of AchE in the incubations during 110 min (a, b, and c were for Pre-, Syn-, and Post-incubation, respectively). (III) the kinetic of effects of EGCG on the inhabition of OPs to AChE during 110 min (Cont. was as control. Comb. was as combination incubation of EGCG and OPs. IC50 of the compounds were as the concentration of inhibitor OPs. CEGCG: COPs = 1:1, µmol·L− 1: µmol·L− 1).

There have been reports indicating that EGCG regulates GEA of oxidative enzymes to counteract the oxidation pressure of AChE from CPF and MAL in embryonic zebrafish46,47. However, the accompanying qPCR determination indicated no significant changes in GEA were observed in brain and vertebral of zebrafish in the acute exposures of 34 h. The further analysis of GEA was conducted in 5 days by a chronic toxic concentration. The results showed that EGCG had difficulty in restoring the dysregulation of GEA to the normal level (Fig. 5I-II). In the 5 days exposure, OPs dysregulated GEA significantly, except for DDVP in brain and MAL in vertebra. EGCG could affect the dysregulated GEA when introduced by the equal or double concentration to OPs, but the effects had not the help to mitigate the dysregulation to normal levels.

Fig. 4.

The average relative activities of AchE in vivo exposed by EGCG combined with OPs (*, the value of ρ) (a and b were for brain and vertebral, respectively). (Cont. was the exposures of independent pesticide as the control. Comb. was as combined incubation. CEGCG: COPs = 1:1, µmol·L− 1: µmol·L− 1).

Molecular interactions on the compounds OPs by EGCG to AChE

Molecular interactions mechanisms on the compounds OPs by EGCG to AChE were addressed through the molecular docking and dynamic simulation. The key and other involved ammonia acids residues of the center active gorge bonded by the four compounds were given in Table 2. The computational indicated that it is possible for OPs to complete a key three-step advance to CAS, i.e., landing to Phe 331 and Tyr 334 by the conjugation, binding to Tyr121 in BNS through the hydrogen bond and penetrating the door of gorge into the inner where CAS is located, and conjugating with Trp 84 and His 440, to finish the phosphorylation of Serine residues in CAS (Fig. 6a). No hydrogen bonds formed for OPs binding to dual active sites, except the hydrogen bond combined with Tyr 121 in BNS. The calculated inhibition indexes were 6.56, 114, and 5.20 mM for the irreversible inhibition of CPF, DDVP, and MAL, respectively.

Table 2.

The affinities of Ligands with the active site of AchE and binding energies by molecular docking.

| Ligand | Binding energy/kcal mol− 1 | Hydrophobic bonds | Conjugation | Hydrogen bond |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| EGCG | -10.231 | 13 |

CAS: His440, Trp84 PAS: Trp279 BNS: Phe330, Tyr121 Other: Tyr70, Phe290, Phe331, Tyr334 |

CAS: Trp84, Ser200 PAS: – BNS: Tyr121 |

| CPF | -7.201 | 9 |

CAS: His440, Trp84 PAS: – BNS: Phe330, Tyr121, Other: Phe331, Tyr334 |

CAS: – PAS: – BNS: Tyr121 |

| DDVP | -5.371 | 7 | – | – |

| MAL | -7.063 | 11 |

CAS: His440, Trp84 PAS: – BNS: Phe330, Tyr121 Other: Tyr70, Phe331, Tyr334 |

CAS: – PAS: – BNS: Tyr121 |

Fig. 5.

The gene expression abundance of AchE in the treatments (*, the value of ρ). (I) Tissue of brain. (II) Tissues of vertebral. (a, b) For CPF, (c, d) for DDVP, (e, f) for MAL, (con. was as control. inde. was as independent treatments of OPs. comb. was the combination treatments of EGCG and OPs. ‘1:1’ & ‘1:2’ were the ratio of mole concentrations of OPs to EGCG).

However, EGCG occupied more sites at the key residues than OPs did in the binding site of catalytic center (Fig. 6a-c), and formed more hydrogen bonds. PAS was one of the dual affinity sites, and the key landing site was considered to be the residue Trp 279. EGCG was affinity to Trp 279 through the conjugation and formed three hydrogen bonds with Tyr121 in BNS, Trp 84 and Ser 200 in CAS. EGCG could directly interact with the dual active sites and occupied six sites in the seven key residues, while OPs might not land at the site of PAS and only combined with no more than 4 four sites. According to the simulation, EGCG interacted with the catalytic center through thirteen hydrophobic bonds including conjugation and hydrogen bonds. The molecular interactions nets between EGCG and the gorge might prevent Serine in CAS from phosphorylation by OPs through steric hindrance. The binding energy indicated the stronger combinations for EGCG to the active center than that for OPs. The complex of EGCG and AChE posed the lowest energy in all the four complexes (Fig. 2).

Dynamic simulation in 50 ns demonstrated that EGCG interfered with the initial binding of OPs to CAS once OPs entered the interior of the gorge. CPF, as one of compounds comprehensively focused on in the toxicology59,60 and with the lowest binding energies to AChE in the three OPs, was modeled to bind to CAS dynamically (Fig. 7). The binding was relatively stable in 20 ns when EGCG was introduced. However, EGCG could destabilize the binding because the root mean square deviation (RMSD) began to rise in the latter 30 ns (Fig. 7a). As can be seen in Fig. 7a, at the beginning of the simulation, the binding of CPF is relatively stable, but the ligand RMSD of CPF rised in the latter part of the simulation, indicating EGCG affected the binding stability of CPF. Among of primary bonds to the key residues, there was the important hydrogen bond formed by CPF with Tyr121 (Fig. 7b). Landing Tyr 121 might help CPF to penetrate the narrow gate in BNS set up by the chain of Phe 330 and Tyr 121 to approach CAS. However, the combinations of CPF with Trp84 in 25 ns and with Tyr121 in 40 ns had been weakening, while the affinity of CPF with Tyr334 was strong in the last 5 ns (Fig. 7c). Thus, the modeling successfully simulated the procession that EGCG might tow CPF away from Try84 and Tyr121 in CAS to Tyr334 situated out of the gorge by forming the complex.

Fig. 6.

Combination of compounds with the active center gorge in AChE. (a) Sketch of molecular interactions in the active center gorge. (b) The binding site in AChE protein of 3-D structure. (c) The main sequences and key ammonia acid of AChE referenced from website of ebi.ac.uk.

Fig. 7.

The dynamic simulations of CPF combined with AchE in present of EGCG. (a) The ligand RMSD in 50 ns simulation. (b) The binding of CPF with ammonia acid in the active site. (c) The energy of vibration in the dynamic simulation.

Since the energy and binding sites of MAL were similar to those of CPF (Table 2), a similar interaction of EGCG with MAL was inferred. It was note that DDVP bond to the residues of catalytic center weakly though there were seven hydrophobic bonds displayed by molecular docking. Hence, EGCG blocking of DDVP from approaching and binding to the gorge through steric hindrance or the formation of a complex was deemed to be more significant than destabilizing the non-covalent bonding to CAS.

Through occupying the key residues in the active center, preventing OPs from binding to the catalytic center of AChE, and interfering with the initial affinity of OPs to CAS, EGCG provided the neuroprotection from OPs targeting to AChE.

Conclusion

The present study demonstrated EGCG improving the inhibited-AChE activities by OPs through competitive affinity with the active site in catalytic center of AChE. EGCG reversing AChE activities were deducted by computational and observed in vitro & vivo at reasonable concentrations. EGCG reactived AChE in three group incubation, and increased the relative activities of AChE from less than 20% to over 70% in brain and vertebral of zebrafish. The hydrophobic bonds especially the hydrogen bonds played the important role. The conjugation at multiple points might form the steric hindrance, which blocked the binding of OPs to the active center of AChE. EGCG also destabilized the initial non-covalent binding of OPs to CAS driving OPs away by forming the complex, as well as occupied the key amino acid residues. The antagonism occurred in brain and vertebral of zebrafish indicated that EGCG as the antidote candidate might take the advantageous over the compounds which only performed in peripheral nerves.

The inhibition to AChE was the main damage to nervous system from OPs. The study supported the idea that EGCG protecting AChE through the antagonism to OPs could directly perform at the catalytic center of AChE. This study was limited to an evaluation of only acute exposure with a single dose in vivo. The chronic exposure with multi-doses was considered to be conducted followed. The further challenges were the knowledge on the effects of EGCG on the synaptic dysfunctions involved in OP‑induced neurotoxicity. These kind works will lead to a better understanding of EGCG effects on the behaviors of AChE, and suggest the further protection of EGCG to cholinergic nerves.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

The authors gratefully thank Anhui Provincial Natural Science Foundation (grant No. 2108085MB39), Anhui Provincial Department of Science and Technology (grant No. 2022m07020004), and National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant No. 32001947).

Abbreviations

- EGCG

(–)-Epigallocatechin-3-gallate

- AChE

Acetylcholinesterase

- OPs

Organophosphorus pesticides

- CPF

Chlorpyrifos

- DDVP

Dichlorvos

- MAL

Malathion

- ATChI

Acetylcholine iodide

- CAS

Central active site

- PAS

Peripheral active site

- BNS

Bottleneck site

- LC50

Median lethal concentration

- IC50

Median inhibition concentration

- EC50

Median effects concentration

- GEA

Gene expression abundance

Author contributions

L. W. analyzed the main data and wrote original draft. J. L. and W. G. prepared Table 1 and 2. R. Zh. wrote and reviewed manuscrip, conceptualized the methodology, and prepared Figs. 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6 and 7. X. L. prepared supplimentary materials. L. F. reviewed and edited manuscrip. Hui Li, conceptualized the methodology. D. P. and W. Y. reviewed manuscrip. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Cascella, M., Bimonte, S., Muzio, M. R., Schiavone, V. & Cuomo, A. The efficacy of epigallocatechin-3-gallate (green tea) in the treatment of Alzheimer’s disease: an overview of pre-clinical studies and translational perspectives in clinical practice. Infect. Agent Cancer. 12, 36. 10.1186/s13027-017-0145-6 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Garcia-Ayllon, M. S., Small, D. H., Avila, J. & Saez-Valero, J. Revisiting the role of acetylcholinesterase in Alzheimer’s disease: cross-talk with P-tau and beta-amyloid. Front. Mol. Neurosci. 4, 22. 10.3389/fnmol.2011.00022 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Uriarte-Pueyo, I. & Calvo, M. I. flavonoids as acetylcholinesterase inhibitors. Curr. Med. Chem. 18, 5289–5302 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Orhan, I. E. Implications of some selected flavonoids towards Alzheimer’s disease with the emphasis on cholinesterase inhibition and their bioproduction by metabolic engineering. Curr. Pharm. Biotechnol. 15, 352–361 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ali, B. et al. In silico analysis of green tea polyphenols as inhibitors of AChE and BChE enzymes in Alzheimer’s disease treatment. CNS Neurol. Disord -Drug Targets. 15, 624–628. 10.2174/1871527315666160321110607 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kiziltas, H. et al. Comprehensive metabolic profiling of Acantholimon caryophyllaceum using LC–HRMS and evaluation of antioxidant activities, enzyme inhibition properties and molecular docking studies. S Afr. J. Bot. 151, 743–755. 10.1016/j.sajb.2022.10.048 (2022). [Google Scholar]

- 7.Youn, K., Ho, C. T. & Jun, M. Multifaceted neuroprotective effects of (-)-epigallocatechin-3-gallate (EGCG) in Alzheimer’s disease: an overview of pre-clinical studies focused on β-amyloid peptide. Food Sci. Hum. Welln. 11, 483–493. 10.1016/j.fshw.2021.12.006 (2022). [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhang, S., Zhu, Q., Chen, J. Y., OuYang, D. & Lu, J. H. The pharmacological activity of epigallocatechin-3-gallate (EGCG) on Alzheimer’s disease animal model: a systematic review. Phytomedicine Int. J. Phytother Phytopharmacol. 79, 153316. 10.1016/j.phymed.2020.153316 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nan, S., Wang, P., Zhang, Y. & Fan, J. Epigallocatechin-3-gallate provides protection against Alzheimer’s disease-induced learning and memory impairments in rats. Drug Des. Dev. Ther. 15, 2013–2024. 10.2147/DDDT.S289473 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ali, A. A. et al. The influence of vinpocetine alone or in combination with epigallocatechin-3-gallate, coenzyme COQ10, vitamin E and selenium as a potential neuroprotective combination against aluminium-induced Alzheimer’s disease in Wistar albino rats. Arch. Gerontol. Geriat. 98, 104557 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wei, B. B., Liu, M. Y., Zhong, X., Yao, W. F. & Wei, M. J. Increased BBB permeability contributes to EGCG-caused cognitive function improvement in natural aging rats: pharmacokinetic and distribution analyses. Acta Pharmacol. Sin. 40, 1490–1500. 10.1038/s41401-019-0243-7 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Li, X., Li, W., Tian, P. & Tan, T. Delineating biosynthesis of Huperzine A, a plant-derived medicine for the treatment of Alzheimer’s disease. Biotechnol. Adv. 60, 108026. 10.1016/j.biotechadv.2022.108026 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Friedli, M. J., Inestrosa, N. C. & Huperzine A and Its neuroprotective molecular signaling in Alzheimer’s disease. Molecules (Basel Switzerland). 26 10.3390/molecules26216531 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 14.Zhang, L., Cao, H., Wen, J. & Xu, M. Green tea polyphenol (-)-epigallocatechin-3-gallate enhances the inhibitory effect of huperzine A on acetylcholinesterase by increasing the affinity with serum albumin. Nutr. Neurosci. 12, 142–148. 10.1179/147683009x423283 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tsai, Y. H. & Lein, P. J. Mechanisms of organophosphate neurotoxicity. Curr. Opin. Toxicol. 26, 49–60. 10.1016/j.cotox.2021.04.002 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mostafalou, S. & Abdollahi, M. The susceptibility of humans to neurodegenerative and neurodevelopmental toxicities caused by organophosphorus pesticides. Arch. Toxicol. 97, 3037–3060. 10.1007/s00204-023-03604-2 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Moyano, P. et al. Toxicogenomic profile of apoptotic and necrotic SN56 basal forebrain cholinergic neuronal loss after acute and long-term chlorpyrifos exposure. Neurotoxicol. Teratol. 59, 68–73. 10.1016/j.ntt.2016.10.002 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hamlin, A. S., Windels, F., Boskovic, Z., Sah, P. & Coulson, E. J. Lesions of the basal forebrain cholinergic system in mice disrupt idiothetic navigation. PLoS One. 8, e53472. 10.1371/journal.pone.0053472 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mostafalou, S. & Abdollahi, M. The link of organophosphorus pesticides with neurodegenerative and neurodevelopmental diseases based on evidence and mechanisms. Toxicology. 409, 44–52. 10.1016/j.tox.2018.07.014 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yadav, B. et al. Implications of organophosphate pesticides on brain cells and their contribution toward progression of Alzheimer’s disease. J. Biochem. Mol. Toxicol. 38, e23660. 10.1002/jbt.23660 (2024). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Newmark, J. Nerve agents. Neurologist. 13, 20–32. 10.1097/01.nrl.0000252923.04894.53 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Aroniadou-Anderjaska, V., Figueiredo, T. H., Apland, J. P. & Braga, M. F. Targeting the glutamatergic system to counteract organophosphate poisoning: a novel therapeutic strategy. Neurobiol. Dis. 133, 104406. 10.1016/j.nbd.2019.02.017 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Worek, F. & Thiermann, H. The value of novel oximes for treatment of poisoning by organophosphorus compounds. Pharmacol. Ther. 139, 249–259. 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2013.04.009 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Worek, F., Thiermann, H. & Wille, T. Oximes in organophosphate poisoning: 60 years of hope and despair. Chem. Biol. Interact. 259, 93–98. 10.1016/j.cbi.2016.04.032 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Worek, F., Thiermann, H. & Wille, T. Organophosphorus compounds and oximes: a critical review. Arch. Toxicol. 94, 2275–2292. 10.1007/s00204-020-02797-0 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cui, Y., Zhao, M. & Han, L. Differences in biological activities between recombinant human paraoxonase 1 (rhPON1) subtype isozemys R/Q as antidotes against organophosphorus poisonings. Toxicol. Lett. 325, 51–61 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lundy, P. M., Hamilton, M. G., Sawyer, T. W. & Mikler, J. Comparative protective effects of HI-6 and MMB-4 against organophosphorous nerve agent poisoning. Toxicology. 285, 90–96. 10.1016/j.tox.2011.04.006 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Horn, G., de Koning, M. C., van Grol, M., Thiermann, H. & Worek, F. Interactions between acetylcholinesterase, toxic organophosphorus compounds and a short series of structurally related non-oxime reactivators: analysis of reactivation and inhibition kinetics in vitro. Toxicol. Lett. 299, 218–225. 10.1016/j.toxlet.2018.10.004 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bist, R., Chaudhary, B. & Bhatt, D. K. Defensive proclivity of bacoside A and bromelain against oxidative stress and AChE gene expression induced by dichlorvos in the brain of Mus musculus. Sci. Rep. 11, 3668. 10.1038/s41598-021-83289-8 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Richendrfer, H. & Creton, R. Chlorpyrifos and malathion have opposite effects on behaviors and brain size that are not correlated to changes in AChE activity. Neurotoxicology. 49, 50–58. 10.1016/j.neuro.2015.05.002 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yang, C. C. & Deng, J. F. Intermediate syndrome following organophosphate insecticide poisoning. J. Chin. Med. Assoc. 70, 467–472. 10.1016/S1726-4901(08)70043-1 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Worek, F., Eyer, P., Aurbek, N., Szinicz, L. & Thiermann, H. Recent advances in evaluation of oxime efficacy in nerve agent poisoning by in vitro analysis. Toxicol. Appl. Pharm. 219, 226–234 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Reyes-Espinosa, F. et al. In Silico Study of the Resistance to Organophosphorus Pesticides Associated with Point mutations in acetylcholinesterase of Lepidoptera: B. Mandarina, B. mori, C. Auricilius, C. Suppressalis, C. Pomonella, H. armígera, P. Xylostella, S. frugiperda, and S. Litura. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 20 10.3390/ijms20102404 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 34.Lushchekina, S. V. et al. Optimization of cholinesterase-based catalytic bioscavengers against Organophosphorus agents. Front. Pharmacol. 9 10.3389/fphar.2018.00211 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 35.Xie, R. et al. Design, synthesis and biological evaluation of organophosphorous-homodimers as dual binding site acetylcholinesterase inhibitors. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 21, 278–282. 10.1016/j.bmc.2012.10.030 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sussman, J. L. et al. Atomic structure of acetylcholinesterase from Torpedo californica: a prototypic acetylcholine-binding protein. Science. 253, 872–879. 10.1126/science.1678899 (1991). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Čadež, T., Kolić, D., Šinko, G. & Kovarik, Z. Assessment of four organophosphorus pesticides as inhibitors of human acetylcholinesterase and butyrylcholinesterase. Sci. Rep. 11 10.1038/s41598-021-00953-9 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 38.Xu, Y., Cheng, S., Sussman, J., Silman, I. & Jiang, H. Computational studies on Acetylcholinesterases. Molecules (Basel Switzerland). 22 10.3390/molecules22081324 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 39.Eckert, S., Eyer, P., Muckter, H. & Worek, F. Kinetic analysis of the protection afforded by reversible inhibitors against irreversible inhibition of acetylcholinesterase by highly toxic organophosphorus compounds. Biochem. Pharmacol. 72, 344–357 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Biasibetti, R. et al. Green tea (-)epigallocatechin-3-gallate reverses oxidative stress and reduces acetylcholinesterase activity in a streptozotocin-induced model of dementia. Behav. Brain Res. 236, 186–193 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zhao, Y. et al. Catechin from green tea had the potential to decrease the chlorpyrifos induced oxidative stress in larval zebrafish (Danio rerio). Pestic Biochem. Physiol. 182, 105028. 10.1016/j.pestbp.2021.105028 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Worek, F., Eyer, P. & Thiermann, H. Determination of acetylcholinesterase activity by the Ellman assay: a versatile tool for in vitro research on medical countermeasures against organophosphate poisoning. Drug Test. Anal. 4, 282–291. 10.1002/dta.337 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Worek, F., Mast, U. & Kiderlen, D. Improved determination of acetylcholinesterase activity in human whole blood. Clin. Chim. Acta. 288, 73–90 (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bradford, M. M. A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding [J]. Anal. Biochem. 72, 248–254 (1976). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Pullaguri, N., Nema, S., Bhargava, Y. & Bhargava, A. Triclosan alters adult zebrafish behavior and targets acetylcholinesterase activity and expression. Environ. Toxicol. Pharmacol. 75, 103311. 10.1016/j.etap.2019.103311 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Fan, R. et al. Individual and synergistic toxic effects of carbendazim and chlorpyrifos on zebrafish embryonic development. Chemosphere. 280, 130769. 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2021.130769 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Shen, W. F. et al. Lethal toxicity and gene expression changes in embryonic zebrafish upon exposure to individual and mixture of malathion, chlorpyrifos and lambda-cyhalothrin. Chemosphere 239 124802 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 48.Kunwar, P. S. et al. Mixed toxicity of chlorpyrifos and dichlorvos show antagonistic effects in the endangered fish species golden mahseer (Tor putitora). Comp. Biochem. Phys. C 240 108923 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 49.Awoyemi, O. M., Kumar, N., Schmitt, C., Subbiah, S. & Crago, J. Behavioral, molecular and physiological responses of embryo-larval zebrafish exposed to types I and II pyrethroids. Chemosphere. 219, 526–537. 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2018.12.026 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Livak, K. J. & Schmittgen, T. D. J. M. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) method. 25(4), 402–408 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 51.Schmittgen, T. D. & Livak, K. J. Analyzing real-time PCR data by the comparative C(T) method. Nat. Protoc. 3, 1101–1108. 10.1038/nprot.2008.73 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Pronk, S. et al. GROMACS 4.5: a high-throughput and highly parallel open source molecular simulation toolkit. Bioinformatics. 29, 845–854. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btt055 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Jorgensen, W. L., Chandrasekhar, J., Madura, J. D., Impey, R. W. & Klein, M. L. Comparison of simple potential functions for simulating liquid water. J. Chem. Phys. 79, 926–935. 10.1063/1.445869 (1983). [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ahmad, V. et al. Computational approaches to evaluate the acetylcholinesterase binding interaction with taxifolin for the management of Alzheimer’s disease. Molecules (Basel Switzerland). 29. 10.3390/molecules29030674 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 55.Cabral, M. F., Sgobbi, L. F., Kataoka, E. M. & Machado, S. A. S. On the behavior of acetylcholinesterase immobilized on carbon nanotubes in the presence of inhibitors. Colloids Surf. B Biointerfaces. 111, 30–35. 10.1016/j.colsurfb.2013.05.017 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Rao, J. V. & Kavitha, P. In vitro effects of chlorpyrifos on the acetylcholinesterase activity of euryhaline fish, Oreochromis mossambicus. Z. Nat. C J. Biosci. 65, 303–306. 10.1515/znc-2010-3-420 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Jammu, C. S. R., Neelima, P. & Rao, K. A review on the toxicity and other effects of Dichlorvos, an organophosphate pesticide to the freshwater fish. Biosci. Discov. 8, 402–415 (2017). [Google Scholar]

- 58.Krstić, D., Colović, M., Krinulović, K., Djurić, D. & Vasić, V. Inhibition of AChE by single and simultaneous exposure to malathion and its degradation products. Gen. Physiol. Biophys. 26, 247–253 (2007). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Zhao, Q. et al. Homo- and hetero-dimers of inactive organophosphorous group binding at dual sites of AChE. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 21, 6404–6408. 10.1016/j.bmcl.2011.08.098 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Ubaid, U. et al. A comprehensive review on chlorpyrifos toxicity with special reference to endocrine disruption: evidence of mechanisms, exposures and mitigation strategies. Sci. Total Environ. 755, 142649. 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.142649 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.