Abstract

The discrepancy between estimated glycemia from HbA1c values and actual average glucose (AG) levels has significant implications for treatment decisions and patient understanding. Factors contributing to the gap include red blood cell (RBC) lifespan and glucose uptake into the RBC. Personalized models have been proposed to enhance AG prediction accuracy by considering interpersonal variation. This study contributes to our understanding of personalized models for estimating AG from HbA1c. Utilizing data from seven studies (340 participants), including Hispanic/Latino populations with or at risk of non-insulin-treated type 2 diabetes (T2D), we examined kinetic features across cohorts. Additionally, the study simulated scenarios to understand data requirements for improving accuracy. Personalized approaches improved agreement between AG estimations and CGM-AG, particularly with four or more weeks of training CGM data. A multiple linear regression model using kinetic parameters and added clinical features was shown to improve the accuracy of personalized models further. As CGM usage extends beyond type 1 diabetes, there is growing interest in leveraging CGM data for clinical decision-making. Patient-specific models offer a valuable tool for managing glycemic status in patients with discordant HbA1c and AG values.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41598-024-72837-7.

Subject terms: Type 1 diabetes, Type 2 diabetes, Diagnosis

Introduction

In diabetes management, glycated hemoglobin (HbA1c) has played a pivotal role in assessing glycemic control and establishing treatment targets, offering an estimate of average glucose (AG) levels over the past 2–3 months1. More recently, continuous glucose monitors (CGMs) are experiencing increasing adoption in diabetes management. Previous studies have indicated a correlation between the 14-day CGM-derived AG (CGM-AG), and the 3-month CGM-AG, suggesting that the 14-day metric can also effectively reflect long-term glycemia2. Despite the expectation that both HbA1c and CGM-AG serve as indicators for average estimates of long-term glycemia, discordance between the two measures has been reported3–5.

Inter-individual variation between HbA1c and glycemic values is influenced by factors beyond blood glucose levels, including red blood cell (RBC) lifespan and RBC glycation rate. Previously, the international, multicenter A1c-Derived Average Glucose (ADAG) study addressed the challenge of translating HbA1c measurements into estimated average glucose (eAG) using a linear regression model. However, data from the ADAG study highlighted the large variation between eAG and AG6.

Similarly, we can estimate an HbA1c value from AG with the Glucose Management Indicator (GMI) which predicts an HbA1c value from mean glucose data. The gap between predicted and measured glycemic values has shown to have clinical implications, potentially leading to misdiagnosis and the risk of suboptimal treatment recommendations7–9. The difference between observed and predicted HbA1c values is called the “hemoglobin glycation index” (HGI)3,10–12. High HGI and glycemic gaps are associated with an elevated risk of diabetes-related complications, such as retinopathy, nephropathy, and adverse cardiac events3,13. Additionally, it has been observed that racial factors contribute to variations in hemoglobin glycation, with HbA1c levels often overestimating AG levels, particularly in black individuals with T1D11.

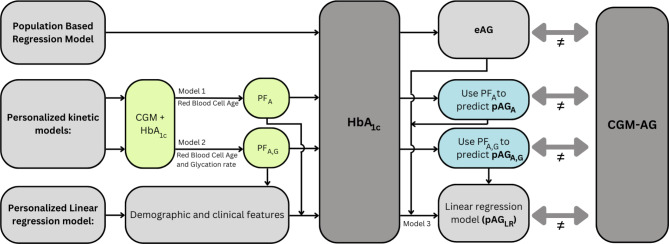

Alternative approaches have been reported that aim to correct discrepancies between estimated and measured glycemic levels12,14,15. In this study, we compared one kinetic model that personalizes HbA1c-derived AG estimates using RBC lifespan introduced by Malka et al. (Model 1) and one considering both RBC lifespan and glucose uptake variability introduced by Xu et al. (Model 2)14,16–20. The aim of the current study was threefold: (i) To determine the benefit of using personalized approaches in datasets with T1D and T2D, including two datasets with a majority of Hispanic/Latino adults with or at risk of T2D. (ii) To compare two patient-specific Models 1 and 2 against the generalized eAG calculation and investigate how much data is essential to improve estimations and (iii) To compare kinetic Models 1 and 2 with a multiple linear regression model (Model 3) that includes kinetic features from Models 1 and 2 as well as demographic and clinical characteristics. The three models were compared with the generalized population-based regression model (eAG), as illustrated in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Overview of models under comparison. HbA1c is often translated to an estimated average glucose (eAG) using a population-based linear regression model. However, the eAG has a high variance with CGM-derived average glucose (CGM-AG). In contrast, novel personalized kinetic models use concurrent CGM and HbA1c data to compute a personalization factor (PF) that can later be used to compute a patient-specific predicted average glucose (pAG). We compare two kinetic models (models 1 and 2) proposed in prior studies to obtain pAGA and pAGA, G. Moreover, we introduce model 3, which employs a multiple linear regression model. This model incorporates demographic, clinical, and kinetic features to generate a pAGLR.

Personalized models

Both patient-specific models share parallel structures: an initial CGM data section with a concurrent HbA1c measurement is used to compute a correction factor, referred to as the personalization factor (PF). This PF is later used to adjust a future AG estimation from an HbA1c measurement, a term that we coined predicted average glucose (pAG).

Model 1: PFA, pAGA

Malka et al. introduced a patient-specific linear model that suggests that intersubject variability between AG and HbA1c can be explained by an inter-patient slope variation, as represented in Eq. (1)15. In this equation,  symbolizes an estimated patient-specific slope that characterizes the relationship between average glucose and HbA1c. The model incorporates AG as a weighted average glucose estimation preceding the HbA1c measurement. Once the estimated slope is found, we can obtain

symbolizes an estimated patient-specific slope that characterizes the relationship between average glucose and HbA1c. The model incorporates AG as a weighted average glucose estimation preceding the HbA1c measurement. Once the estimated slope is found, we can obtain  , or estimated mean RBC age using Eq. (2). The equation includes two estimated constants: kg, the glycation rate, and the intercept HbA1c(0). For clear interpretation and to align both models, we refer to the

, or estimated mean RBC age using Eq. (2). The equation includes two estimated constants: kg, the glycation rate, and the intercept HbA1c(0). For clear interpretation and to align both models, we refer to the  as the Personalization Factor (PFA) with the subscript to represent that this model considers RBC aging. Using PFA, we can compute the pAGA with Eq. (3).

as the Personalization Factor (PFA) with the subscript to represent that this model considers RBC aging. Using PFA, we can compute the pAGA with Eq. (3).

|

1 |

|

2 |

|

3 |

Model 2: PFA, G, pAGA, G

Xu et al. proposed a model that incorporates RBC lifespan as well as glycation uptake rate. This model introduces a patient-specific personalization factor called Apparent Glycation Ratio (AGR) shown in Eq. (4). For streamlined nomenclature, we call this PFA, G representing the personalization factor based on age and glycation rate. In this equation, AG signifies average glucose, and KM represents the universally assumed Michaelis constant for Glucose Transporter 1 (GLUT-1)18,19.

|

4 |

According to Xu et al., an AGR of 65.1 ml/g is the expected value for an individual with a typical RBC lifespan of 105 days and a glycation rate of 0.62 mL/g per day20. A higher value categorizes a participant as a “high glycator,” and a low value is characteristic of a “low glycator”. The PF can then be used to estimate the pAGA, G using Eq. (4) in conjunction with a subsequent HbA1c measurement20.

|

5 |

Model 3: Linear regression model, pAGLR

As seen from Models 1 and 2, each model gives us patient-specific kinetic features and a predicted AG value. However, the models lack demographic and clinical information such as diabetes type or change in HbA1c levels since the time of the PF estimation. In this study, we included kinetic features from Models 1 and 2 and available demographic and clinical information into a multiple linear regression model to obtain a predicted AG that we termed pAGLR.

Results

Patient profiles

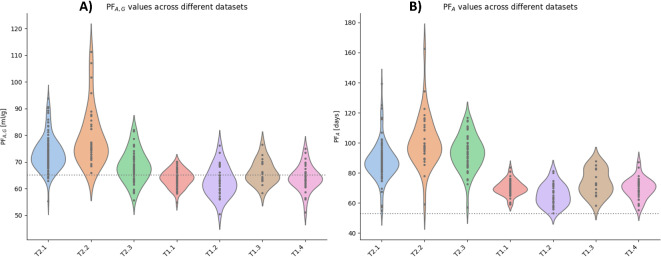

We analyzed the personalization factors (PFA, G, and PFA) values across the different datasets (Fig. 2). This analysis aimed to determine which datasets would experience more substantial corrections when using Models 1 and 2. PF values with greater deviation from the reference correspond to more extensive corrections. Elevated PF values suggest an overestimation of AG from HbA1c, while lower values imply an underestimation of AG. For Datasets T2.1 and T2.2 (please refer to the Dataset section for more information), the median PFA, G in the study was 72.3 ml/g (IQR: 69.1, 76.2 ml/g) and 75.3 ml/g (IQR: 72.8 to 83.6 ml/g), respectively. PFA, G values in the T2.1 and T2.2 datasets were significantly higher than the reference value of 65.1 ml/g (p < 0.0005 for both). Dataset T2.3 also had a higher PFA, G of 68.1 ml/g (IQR: 63.9 to 71.8 ml/g) with p < 0.005. All other datasets (T1.1-4 and T2.3) were not significantly different than the reference (Fig. 2a). When comparing the PFA against the reference value of 53 days13, all datasets showed a higher PFA median (p < 0.005) (Fig. 2b). However, Datasets T2.1, T2.2, and T2.3 offer higher values (86.6 [82.4, 92.5], 97.6 [93.1,109.1], and 93.5 [85.7,100] days) than the rest of the datasets (T1.1-4) (69.5 [67.5,72.4], 64.5 [60.4, 70.9], 72.3 [66.1, 82.5], and 70.2 [66.4, 73.7] days). We also compared PFA, G and PFA values for different demographic groups, as shown in Supplementary Figs. 1 and 2 and found no consistent significant differences across datasets.

Fig. 2.

Comparing PFA, G, and PFAacross datasets using a violin plot to depict the data distributions for each dataset. (A) Dataset T2.1 and Dataset T2.2 have higher PFA, Gvalues than Datasets T2.3, T1.1-T1.4, and the reference value of 65.1 ml/g (dotted line). (B) PFAvalues are higher than the reference of 53 days (dotted line) for all datasets, with Dataset T2.1, T2.2, and T2.2 showing even higher values.

Data length and predictive accuracy

Impact of data duration

In our simulation study, we targeted Datasets T1.1, T1.3, and T1.4 (n = 112). Throughout the study, we simulated scenarios using different lengths of CGM data, ranging from one to twelve weeks, for both the training and testing segments. The aim was to evaluate the estimated values in comparison to the actual CGM-AG. We performed this simulation to determine the optimal duration of CGM data required for accurate estimations.

To establish a baseline, we compared the Root Mean Squared Errors (RMSE) between the eAG and the CGM-AG. As testing duration increased, eAG-CGM-AG RMSE decreased: 12 weeks resulted in 11 mg/dL, versus 13 mg/dL with four weeks (Supplementary Fig. 6). Simultaneously, standard deviation (SD) increased from 14 mg/dL to 17 mg/dL with shorter testing data, aligning with expectations that eAG has a better match with long-term CGM-AG.

Assessing pAGs, we studied the impact of varying CGM data length for training on pAG accuracy compared to CGM-AG during testing. Varying training CGM data from 1 to 12 weeks improved RMSE and SD. With 12 weeks of training and testing, both pAGA and pAGA, G had lower RMSE and SD than eAG (eAG: 11 ± 14 mg/dL, pAGA, G: 8 ± 11 mg/dL, pAGA: 6 ± 8 mg/dL) (Supplementary Fig. 6).

Using 4 weeks of CGM data for training, Model 1 (pAGA) showed improved RMSE and SD (eAG: 11 ± 14 mg/dL, pAGA: 8 ± 11 mg/dL), regardless of a 3-month data gap (Supplementary Fig. 6c and 6d). With Model 2, pAGA, G exhibited lower RMSE with 4 weeks of data but worsened SD (pAGA, G: 10 ± 15 mg/dL). Since the kinetic models presume stable glycemic control, a time gap between training and testing did not significantly affect pAG for individuals without drastic glycemic changes. Nonetheless, simulations for participants with HbA1c changes exceeding 0.4% showed that Model 1 with 4 weeks of training data and a 3-month gap had a better RMSE than eAG (eAG: 11 ± 14 mg/dL, pAGA: 9 ± 13 mg/dL), but this was not true for Model 2, where performance was worse than eAG (pAGA, G: 13 ± 16 mg/dL) (Fig. 3).

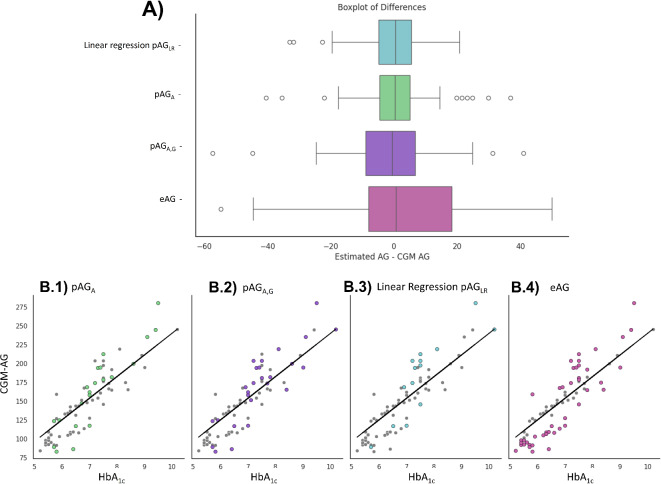

Fig. 3.

Comparing kinetic models with multiple linear regression model. Panel (A) Comparison of different glucose estimation models, including the top-performing multiple linear regression model selected after an exhaustive feature selection search. Panel (B) Analyzing Clinical Errors: Assessing the number of participants with clinically significant errors for each model: pAGAshowed high errors in 21 participants (B.1), pAGA, Gin 26 participants (B.2), the top-performing linear regression model in 15 participants (B.3), and eAG in 44 participants (B.4).

Performance of patient-specific estimated AG

To compare patient-specific estimated AG values, we performed a Bland-Altman (BA) analysis of the Merged dataset. Focusing on error assessment between eAG or patient-specific estimations (pAGA and pAGA, G) and CGM-AG, we simulated three scenarios: (1) A single data section with a 3-month gap (Fig. 4, B.1), (2) A single contiguous data section to the prediction section (Fig. 4, B.2), and (3) Two contiguous data sections to the prediction section (Fig. 4, B.3).

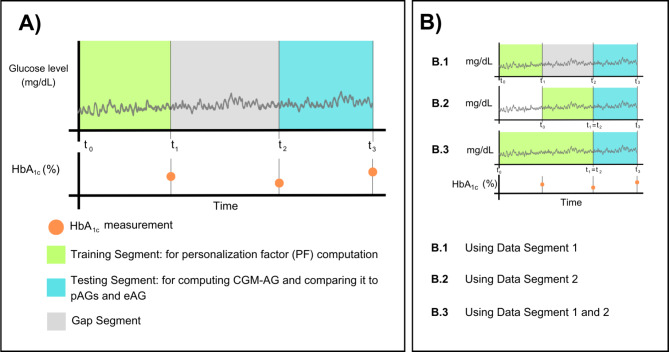

Fig. 4.

Data sectioning and structure. (A) Defining structure and nomenclature. Green: The training segment used for computing the personalization factors (PFs) is delimited by the start of continuous glucose monitoring (CGM) data and a contiguous HbA1c measurement. Blue: the testing segment, comprised of CGM data and a contiguous HbA1c used to compute the estimated average glucose (eAG) and personalized AG (pAGs), which are then compared to the average glucose from the CGM (CGM-AG). In some cases, there is a data gap between training and testing, defined as the gap segment (gray). (B) Data partitioning: Datasets T1.1, T1.3, and T1.4 have three HbA1c measurements every ∽3 months. We use different segments of data as the training segment.

The BA plots showed higher consistency for pAGA, G than eAG [the reproducibility coefficient (RPC) for pAGA, G using 2 and 1 data sections were 19.5, 34.6, and 25.9 mg/dL vs. 41.3 mg/dL for eAG]. For pAGA, the RPC was consistently lower, ranging from 15.7 to 31.9 mg/dL across scenarios. Significantly, there was a bias for both eAG and pAGA, G when estimated using a single data section with a 3-month gap (Supplementary Fig. 3a and 3b). However, bias was absent when using pAGA, G with one or two data sections contiguous to the prediction (Supplementary Fig. 3c and 3d). Moreover, pAGA exhibited no significant bias across any of the scenarios examined (Supplementary Fig. 3e, 3f, and 3 g). The number of data points is higher when using the second data segment (n = 247) than when using segment 1 or segments 1 and 2 (n = 112) since datasets T2.1 and T1.2 did not have sufficient longitudinal CGM data to simulate a 3-month gap between PF computation and prediction.

Moreover, we looked at the number of clinically significant errors (> 10 mg/dL) and observed lower errors when using pAGA and pAGA, G than eAG as observed in Supplementary Figs. 4 and 5.

Multiple linear regression model

Lastly, we used a multiple linear regression model to combine prior knowledge from kinetic models with demographic and clinical information. We analyzed the correlations between the available features (shown in Supplementary Fig. 7). We excluded features that were highly correlated with clinically significant features, such as HbA1c, to avoid multicollinearity issues. We also removed one of the PFs as they were highly correlated with each other. With the resulting features: HbA1c, PFA, G, Age, Delta HbA1c (defined as the difference between the most recent HbA1c measurement and an older HbA1c measurement), BMI, Gender, and Type of Diabetes, we trained a linear regression model. After analyzing the coefficients and p-values, we removed non-significant features (p > 0.005) from the model. The final multiple linear regression model used only HbA1c, PFA, G, Delta HbA1c and can be seen in Eq. (6).

|

6 |

The coefficients and p-values are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Coefficients and P-values from the multiple Linear regression model.

| Predictor Variable | Coeficient | Standard Error | t-value | p-value | [0.025, 0.975] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Const | 100.2 | 11.9 | 8.5 | 0.000 | [76.8, 123.7] |

| HbA1c | 29.7 | 0.9 | 33.7 | 0.000 | [27.9, 31.5] |

| PFA, G | -2.3 | 0.1 | -18.3 | 0.000 | [-2.6, -2.1] |

| Delta HbA1c | -14.7 | 1.6 | -9.2 | 0.000 | [-17.8, -11.5] |

From the testing set, we analyzed the outliers using a parallel coordinate plot (Supplementary Fig. 8) and we noticed one participant had consistently high error. When looking at that participant’s featured, we discovered a very high Delta HbA1c suggestion possible measuring error. Therefore, we removed this participant from the analysis. Data from other participants that also had high error across all four models were left in the testing set as no inconsistencies in the data were found. We compared the linear regression model, which we coined peAGLR, with the other models (Fig. 3). Evaluation metrics at testing were: R2: 0.94, MAE: 7.4 mg/dL, MSE: 105.2 mg2/dL2, RMSE: 10.3 mg/dL. In comparison, a linear regression model using only HbA1c as the training feature yielded testing R2: 0.79, MAE: 16.3 mg/dL, MSE: 421.1 mg2/dL2, and RMSE: 20.5 mg/dL.

In Fig. 3, we compare the best model we obtained with the personalized estimations (pAGA, pAGA, G) and the population-based model (eAG). Moreover, we show in Fig. 3.B a scatterplot illustrating the number of participants that had a clinically significant error. The highest number of significant errors were associated with eAG, where 44 out of 74 (59.5%) participants were misestimated. The pAGLR demonstrated a moderate improvement over the personalized estimations using the kinetic model (pAGA and pAGA, G), with 15 out of 74 (20.2%) participants experiencing high errors compared to 26 (35.1%) and 21 (28.4%), respectively.

Discussion

Translating AG levels to HbA1c and vice versa can facilitate clinical decision-making, patient understanding, effective communication, and comparability in research. Moreover, it enables us to align with the technological advancements in diabetes care, such as CGMs. However, existing formulas such as eAG and GMI, developed to convert from one measurement to another, fail to account for inter-individual variation21,22. Researchers have developed customized mathematical models to understand the HbA1c-AG relationship and personalize AG estimations, but their validation in diverse datasets is needed15,18–20,23–25. Further insights are necessary to determine the optimal scenarios for applying these models to enhance personalized estimations.

In the current study, we performed a comparative analysis of kinetic models in the context of diverse populations, with datasets with individuals with T1D and T2D. Our analysis contrasts two existing methodologies across seven datasets. We include two datasets primarily comprising Hispanic/Latino adults with or at risk of T2D. Introducing Hispanic/Latino datasets involving individuals with T2D is innovative, given the scarcity of research findings within the HGI domain pertaining to this specific demographic group21,22. Previous research has demonstrated significant differences in AG and HbA1c levels between White and Black or African-American participants11,23,26.

Our investigation highlighted that datasets primarily composed of individuals with or at risk of type 2 diabetes observed significantly higher personalization factors considering age (PFA) and both age and glycation rate (PFA, G). Deviation of PF values from the reference value indicates either an overestimation or underestimation of AG derived from HbA1c, with high PF values suggesting that HbA1c levels overestimate AG levels for that population. Specifically, in our analysis, Hispanic/Latino populations with or at risk of T2D show higher PFA, G values than the reference and other datasets, which predominantly featured White participants with T1D (T1.1-T1.4). When comparing T2.1 and T2.2 PFA, G values to the dataset T2.3 (comprised mostly of normoglycemic individuals with some individuals with prediabetes or diabetes but unknown race/ethnicity), the studies with mostly Hispanic/Latino individuals also showed higher PFA, G values. However, when comparing PFA values, all T2.1,T2.2, and T2.3 datasets are higher than T1.1-T1.4. The findings suggest that a systematic study should be conducted considering diabetes type and racial and ethnic differences to understand why the HGI is wider for specific demographic groups. The study should also include participants with both T1D and T2D and confirm the validity of the suggested reference values. Our work does not aim to suggest that different glycemic targets are needed for each racial and ethnic group, but rather that the translation between the two diagnostic tests is an opportunity to understand individual glycemic and nonglycemic factors contributing to HbA1c levels. With our limited datasets, we cannot conclude that Hispanic/Latino individuals will have different HGI as type of diabetes plays a confounding role in our analysis. The introduction of dataset T2.3 allows us to see that PFA, G is higher for the Hispanic/Latinos. However, this finding is not consistent when analyzing PGA.

Both personalized estimations, pAGA, and pAGA, G, consistently outperformed the conventional eAG model when using four or more weeks of CGM data for training. Improvement of patient-specific estimations underlines the potential benefits of incorporating personalized and data-driven approaches in glucose monitoring with a limited monitoring burden. Furthermore, our introduction of a linear regression model demonstrated an improvement over the personalized estimations, suggesting a novel direction for enhancing accuracy by combining kinetic models and adding clinical and demographic or clinical features. However, it is crucial to acknowledge that further investigation is warranted to determine the clinical significance of incorporating patient-specific models.

Our study has several limitations. Firstly, the studies we analyzed did not have sufficient representation of Blacks, Asians, and individuals of other races with T2D or T1D to make a comprehensive racial analysis. Moreover, the studies used different CGM devices and lengths of use. While the CGM devices employed in our analysis exhibit similar characteristics and functionalities (more details in Supplementary Table 1), it’s noteworthy that they originate from various manufacturers. Including multiple devices provides a more comprehensive representation of the diverse technologies available. However, it’s essential to acknowledge that differences in calibration methods, sensor technologies, and algorithms may persist among these devices. While these distinctions contribute to the richness of our dataset, they also highlight the importance of cautious interpretation when extending our conclusions. Finally, our analysis does not consider potential hemoglobinopathies or other conditions affecting RBC dynamics.

While our study has several limitations, our findings offer valuable insights into the complex dynamics of glycemic control in three ways. First, the comparison between two mathematical models across seven different datasets, with two mainly comprised mostly of an underserved Hispanic/Latino community with or at risk of T2D, found that this cohort seems to have significantly different nonglycemic factors contributing to their HbA1c levels when compared to the values for non-Hispanic White individuals with T1D. Secondly, we show that personalized AG estimations can improve agreement between estimates and long-term and short-term CGM-AG. This improvement is found when using at least 4 weeks of training data. Lastly, utilizing the kinetic model’s features can further improve personalized estimations by incorporating additional demographic and clinical features into a linear regression model.

In conclusion, our study advances the understanding of personalized models for estimating AG from HbA1c values. As CGM usage expands, our findings highlight the potential of patient-specific models in addressing the discordance between HbA1c and CGM measures. Finding more accurate ways to translate between AG and HbA1c holds significant promise for developing more precise and personalized diabetes management strategies. For instance, algorithms that can learn about patient-specific relationships between both measurements can be incorporated into CGM devices to enhance their functionality and accuracy. Users can input HbA1c readings when tested, allowing the device to learn the patient-specific glycation rate. Obtaining personalized AG estimations would improve the management of glycemic status in patients with discordant HbA1c and AG values. Our research aims to further validate the kinetic models, providing individuals with diabetes better tools to understand their glycation rate. Furthermore, we underscore the need for future research to unravel the factors contributing to the higher glycemic gap observed in specific populations and to refine the utilization of kinetic models.

Methods

Data sectioning

We utilized seven independent datasets (refer to Tables 2 and 3, and the “Dataset Descriptions” section in Supplementary Material) and created a “Merged Dataset” (Tables 2 and 3). Each independent dataset is denoted as T1.n for those diagnosed with T1D and T2.n for those with or at risk of T2D. For all datasets, a data segment was defined as the combination of an HbA1c measurement and contiguous CGM data, as shown in Fig. 4A. One data segment is designated as the “training segment,” used for computing personalization factors (PFs), and a subsequent segment is used as the “testing segment.” In the testing segment, the HbA1c measurement was used to compute pAGs and eAG. The estimates were then compared to the CGM-AG. If there was a time gap between training and testing, we referred to this as the “gap segment.” The gap segment was not present in most scenarios, but it was defined for clarity when CGM data was not used or not available. We had three contiguous data segments for datasets T1.1, T1.3, and T1.4. We used different CGM lengths to compute PFs, as shown in Fig. 4B.

Table 2.

Demographic information of datasets T2.1, T2.2, T2.3 and T1.1.

| T2.1. - Farming for Life * | T2.2. - Digital Health | T2.3 - Glucotypes | T1.1. -REPLACE-BG | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Paired A1c | Used Data | All/Used | All | All** | Used Data | |

| Participants | At-risk/pre-diabetes or T2D | At-risk/pre-diabetes or T2D | At-risk/pre-diabetes or T2D | Normoglycemic/pre-diabetes or T2D | T1D | T1D |

| n | 247 | 105 | 36 | 57 | 226 | 60 |

| Age - Mean (SD) | 54.2 ± 11.9 | 54.4 ± 11.8 | 49.9 ± 12 | 48.9 ± 14 | 44 ± 14 | 48.6 ± 13.6 |

| BMI - Mean (SD) | 31.3 ± 6 | 30 ± 5.1 | 32.7 ± 5.5 | 26.7 ± 4.7 | 27.3 ± 4.4 | 27.2 ± 4 |

| Gender | ||||||

| Female | 187 (75.7%) | 77 (73.3%) | 28 (77.8%) | 32 (56.1%) | 112 (49.6%) | 27 (45%) |

| Male | 60 (24.3%) | 28 (26.7%) | 8 (22.2%) | 25 (43.9%) | 114 (50.4%) | 33 (55%) |

| Race/Ethnicity | ||||||

| Non-Hispanic White | 33 (13.4%) | 9 (8.6%) | 0 | - | 207 (91.6%) | 54 (90%) |

| Hispanic or Latino | 208 (84.2%) | 96 (91.4%) | 36 (100%) | - | 9 (4.0%) | 3 (0.05%) |

| Black/African American | 3 (1.2%) | 0 | 0 | - | 5 (2.2%) | 2 (3%) |

| Asian | 3 (1.2%) | 0 | 0 | - | 4 (1.8%) | 0 |

| Other/ Unknown | 0 | 0 | 0 | 57 (100%) | 1 (0.4%) | 1 (1.7%) |

| Laboratory HbA 1c | ||||||

| HbA1c < 5.7% | 79 (31.9%) | 38 (36.2%) | 13 (36.1%) | 44 (77.2%) | 7 (3.1%) | 2 (3.3%) |

| 5.7%≤ HbA1c ≤ 6.4% | 90 (36.4%) | 35 (33.3%) | 9 (25%) | 9 (15.8%) | 35 (15.5%) | 7 (11.7%) |

| HbA1c > 6.4% | 78 (31.6%) | 32 (30.5%) | 14 (38.9%) | 2 (3.5%) *** | 184 (81.4%) | 51 (85%) |

| Arm/Group | ||||||

| CGM only | NA | NA | NA | NA | 149 (65.9%) | 40 (66.7%) |

| CGM + BGM | NA | NA | NA | NA | 77 (34.1%) | 20 (33.3%) |

| Data Segments | ||||||

| CGM Length | 2 segments 10–14 days with 10 week gap | 2 weeks | 1 week | 2–10 week run-in phase + 6-month trial | 3 segments > 60 days | |

| HbA1c | NA | t0 and t3 | t0 | t0 | NA | t1, t2, t3 |

| NCT | NCT03940300 | NCT04820348 | - | NCT02258373 | ||

*at enrollment.

**From A Trial Comparing Continuous Glucose Monitoring With and Without Routine Blood Glucose Monitoring in Adults With Type 1 Diabetes - Study Results - ClinicalTrials.gov.

*** 2 participants with unknown HbA1c were not used in the analysis.

Table 3.

Demographic information of datasets T1.1-T1.4, and the merged dataset.

| T1.2. - DirectNet - CGM in Young Children | T1.3. - DirectNet - Metabolic Control | T1.4. - RT-CGM | Merged Dataset | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All | Used Data | All | Used | All | Used Data | Used | |

| Participants | T1D | T1D | T1D | T1D | T1D | T1D | T1D, At-risk/pre-diabetes or T2D |

| n | 146 | 30 | 71 | 19 | 451 | 33 | 247 |

| Age - Mean (SD) | 7.2 ± 1.8 | 6.9 ± 2 | 12.9 ± 5.6 | 13.3 ± 6.4 | 25 ± 15.8 | 21.2 ± 11.8 | 39.6 ± 21.6 |

| BMI - Mean (SD) | 17.4 ± 2.2 | 17.3 ± 1.9 | 18.4 ± 3.5 | 18.3 ± 3.4 | 23.5 ± 4.4 | 23.1 ± 4.7 | 26 ± 6.4 |

| Gender | |||||||

| Female | 79 (54.1%) | 17 (56.7%) | 25 (35.2%) | 8 (42.1%) | 248 (55%) | 21 (63.6%) | 150 (60.7%) |

| Male | 67 (45.9%) | 13 (43.3%) | 46 (64.8%) | 11 (57.9%) | 203 (45%) | 12 (36.4%) | 97 (39.3%) |

| Race/Ethnicity | |||||||

| Non-Hispanic White | 112 (76.7%) | 23 (76.6%) | 63 (88.7%) | 19 (100%) | 417 (92.6%) | 30 (90.9%) | 135 (54.7%) |

| Hispanic or Latino | 14 (9.6%) | 2 (6.6%) | 3 (4.2%) | 0 | 15 (3.3%) | 1 (3.0%) | 102 (41.3%) |

| Black/African American | 6 (4.1%) | 1 (3.3%) | 1 (1.4%) | 0 | 7 (1.6%) | 1 (3.0%) | 4 (1.6%) |

| Asian | 4 (2.7%) | 1 (3.3%) | 0 | 0 | 2 (0.4%) | 0 | 1 (0.4%) |

| Other/ Unknown/More than one race | 10 (6.8%) | 3 (10%) | 4 (5.6%) | 0 | 10 (2.2%) | 1 (3.0%) | 5 (2%) |

| Laboratory HbA 1c | |||||||

| HbA1c < 5.7% | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 6 (1.3%)** | 0 | 40 (16.2%) |

| 5.7%≤ HbA1c ≤ 6.4% | 0 | 0 | 1 (1.4%) | 0 | 47 (10.5%) | 5 (15.2%) | 47 (19%) |

| HbA1c > 6.4% | 146 (100%) | 30 (100%) | 69 (98.6%)* | 19 (100%) | 396 (88.2%) | 28 (84.8%) | 160 (64.8%) |

| Arm/Group | |||||||

| Control | 72 (49.3%) | 6 (20%) | 50 (70.4%) | 0 | 219 (48.6%) | 0 | NA |

| Active | 74 (50.7%) | 24 (80%) | 21 (29.6%) | 19 (100%) | 232 (51.4%) | 33 (100%) | NA |

| Data Segments | |||||||

| CGM Length |

Phase 1: 26 weeks Phase 2: 26 weeks |

2 segments > 45 days | up to 2 years | ∽9 months of consecutive data |

Phase 1: 26 weeks Phase 2: 26 weeks |

3 segments > 45 days | 2 segments > 45 days |

| HbA1c | NA | t1 (equal to t2), and t3 | NA | t1, t2, tP3 | NA | t1, t2, t3 | t1 (equal to t2), and t3 |

| NCT | NCT00760526 | NCT00891995 | NCT00406133 | - | |||

* One participant had no Baseline HbA1c measurement.

** 2 participants with missing HbA1c measurements at Randomization.

Datasets

A description of our datasets is presented in Tables 2 and 3. Two sets comprised participants with or at-risk (including pre-diabetes) of non-insulin treated T2D with mostly Hispanic/Latino adults (T2.1 and T2.2); one dataset was primarily comprised of normoglycemic participants with some individuals with prediabetes or T2D (T2.3)27. The rest of the participants with T1D with mostly non-Hispanic White participants (T1.1-T1.4)28–33.

We created a Merged Dataset with Datasets T2.1, T1.1, T1.2, T1.3, and T1.4. We included only these datasets since they offered two data sections with CGM and a contiguous HbA1c measurement. Two data sections were needed to train using the first section and to later test for accuracy when prediction AG. The remaining datasets were used when comparing PFs in Fig. 2. Moreover, datasets T1.1, T1.3, and T1.3 had three consecutive data sections and could be used for simulating in the Results “Data length and predictive accuracy”.

Datasets T1.1-T1.4 were obtained from the Jaeb Center for Health Research https://public.jaeb.org/. The analyses content and conclusions presented herein are solely the responsibility of the authors and have not been reviewed or approved by the Jaeb Center for Health Research or DirectNet.

Datasets T2.1 (Farming for Life NCT03940300) and T2.2 (Digital Health NCT04820348) were obtained from two independent studies aimed to study behavioral interventions on Hispanic/Latino subjects with or at risk of T2D. Ethics approval was obtained from Advarra IRB and the Rice University Institutional Review Board (IRB-FY2021-54), respectively. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants. All methods were carried out in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations.

Study design

To understand the effectiveness of patient-specific models in estimating AG levels compared to generalized models, we sought to understand three aspects:

Comparing kinetic features in different datasets: We aimed to identify which individuals benefit the most from individual-specific models. Using seven datasets, including two of predominantly Hispanic/Latino adults at risk of or diagnosed with non-insulin-treated T2D, we compared personalization factors (PFA and PFA, G). We also compared PFs with published reference values for standard RBC age and glucose uptake rate using the Wilcoxon signed-rank test.

Data Length and Predictive Accuracy: Two aspects were investigated. Firstly, we determined the necessary CGM data length for accurate PF computation, simulating scenarios with training data ranging from one to twelve weeks. Secondly, we assessed model performance by comparing participants with errors exceeding a clinically significant glucose threshold (10 mg/dL) and using BA plots. We analyzed error metrics such as mean error (indicating bias) and confidence intervals (measuring error spread) to gain deeper insights into model accuracy.

Addition of demographic information to a linear regression model: Lastly, we tested our multiple linear regression model to further improve the glucose estimations obtained from the patient-specific models by combining them and including additional features. The original set of characteristics included the personalization factors and the predicted AG values (pAGA, pAGA, G). We also incorporated age, gender, Body Mass Index (BMI), and change in HbA1c, as well as encoded T1D/T2D status and dataset.

To select the best feature subset, we divided the Merged Dataset (247 samples detailed in Tables 2 and 3), combining Datasets T2.1, T1.1, T1.2, T1.3, and T1.4 into a 70/30 train-test split. The split was stratified by dataset to ensure the proportion of participants from each dataset was represented equally in the training and testing set. We analyzed correlations between features (Supplementary Fig. 7) and removed any feature that was highly correlated with HbA1c. We also removed any other highly correlated feature. We evaluated coefficients and kept significant features only to present a model with coefficients that can be easily interpreted.

We employed the testing dataset to evaluate model performance using the coefficient of determination (R2), which assesses the variance in the data, Mean Absolute Error (MAE) to measure the absolute difference between predictions and actual values, Mean Squared Error (MSE) to provide the squared difference emphasizing large errors, and Root Mean Squared Error (RMSE) to provide an average size of the errors. We compared the performance against patient-specific models and eAG by examining the number of participants in the testing dataset that had a high (> 10 mg/dL) error between CGM-AG and the estimations.

Statistical analysis

All statistical tests were performed using Python (version 3.10.12) and the following libraries: numpy (version 1.23.5), pandas (version 1.5.3), and scipy (version 1.10.1). Additionally, for the development of our linear regression models, we utilized the scikit-learn library.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

We gratefully acknowledge Dr. Timothy Dunn, Dr. Yongjin Xu, Dr. Yashevini Ram for their invaluable explanations of their model.

Author contributions

ES, AS, and DK worked on conceptualization, methodology, and formal analysis. ES performed statistical analyses, created figures, and drafted the manuscript. AS, WB, and DK contributed to review and editing of the manuscript. WB and DK played a crucial role in facilitating data curation from the Farming for Life and Digital Health Studies.

Data availability

Data from the Farming for Life (T2.1) and Digital Health (T2.2) datasets is available upon reasonable request. To gain access, data requestors will need to sign a data access agreement. Requests should be directed to wbevier@sansum.org.

Declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.English, E. & Lenters-Westra, E. HbA1c method performance: The great success story of global standardization. Crit. Rev. Clin. Lab. Sci. 55, 408–419 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Riddlesworth, T. D. et al. Optimal sampling duration for continuous glucose monitoring to long-term glycemic control. Diabetes Technol. Ther. 20, 314–316 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mccarter, R. J., Hempe, J. M., Gomez, R. & Chalew, S. A. Biological variation in HbA 1c predicts risk of retinopathy and nephropathy in type 1 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 27, 1259–1264 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cohen, R. M. et al. Red cell life span heterogeneity in hematologically normal people is sufficient to alter HbA1c. Blood. 112, 4284–4291 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Snieder, H. et al. HbA1c levels are genetically determined even in type 1 diabetes evidence from healthy and diabetic twins. Diabetes 50, 2858–2863 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nathan, D. M. et al. Translating the A1C assay into estimated average glucose values. Diabetes Care. 31, 1473–1478 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sacks, D. B., Bebu, I. & Lachin, J. M. Refining measurement of hemoglobin A1c. Clin. Chem. 63, 1433–1435 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sacks, D. B., Nathan, D. M. & Lachin, J. M. Gaps in the glycation gap hypothesis. Clin. Chem. 57, 150–152 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hempe, J. M., Gomez, R., McCarter, R. J. & Chalew, S. A. High and low hemoglobin glycation phenotypes in type 1 diabetes: A challenge for interpretation of glycemic control. J. Diabetes Complic. 16, 313–320 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hsia, D. S. et al. Implications of the hemoglobin glycation index on the diagnosis of prediabetes and diabetes. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 105, e118–e126 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bergenstal, R. M. et al. Racial differences in the relationship of glucose concentrations and hemoglobin A1c levels. Ann. Intern. Med. 167, 95-102 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 12.Cohen, R. M. & Smith, E. P. Frequency of HbA1c discordance in estimating blood glucose control. Clin. Nutr. Metabolic Care 11, 512–517 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Liao, W. I. et al. An elevated glycemic gap is associated with adverse outcomes in diabetic patients with acute myocardial infarction. Sci. Rep. 6, 27770 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 14.Gonzalez, A. et al. Research: Epidemiology impact of mismatches in HbA 1c vs glucose values on the diagnostic classification of diabetes and prediabetes. Diabet. Med. 37, 689–696 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Malka, R., Nathan, D. M. & Higgins, J. M. Mechanistic modeling of hemoglobin glycation and red blood cell kinetics enables personalized diabetes monitoring. Sci. Transl. Med. 8, 359ra130 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 16.Ladyzynski, P. et al. Validation of a hemoglobin A1c model in patients with type 1 and type 2 diabetes and its use to go beyond the averaged relationship of hemoglobin A1c and mean glucose level. J. Transl. Med. 12, 1–16 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ladyzynski, P. et al. Validation of hemoglobin glycation models using glycemia monitoring in vivo and culturing of erythrocytes in vitro. Ann. Biomed. Eng. 36, 1188–1202 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Xu, Y., Dunn, T. C. & Ajjan, R. A. A kinetic model for glucose levels and hemoglobin A1c provides a individualized diabetes management. J. Diabetes Sci. Technol. 15, 294–302 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Xu, Y., Bergenstal, R. M., Dunn, T. C. & Ajjan, R. A. Addressing shortfalls of laboratory HbA1c using a model that incorporates red cell lifespan. eLife 10 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 20.Hirota, Y. et al. Type 1 diabetes iron-deficiency anaemia case report and the clinical relevance of red blood cell lifespan-adjusted glycated haemoglobin. Diabetes Obes. Metab. 25(1), 319-322 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 21.Angellotti, E., Muppavarapu, S., Siegel, R. D. & Pittas, A. G. The calculation of the glucose management indicator is influenced by the continuous glucose monitoring system and patient race. Diabetes Technol. Ther. 22, 651–657 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Toschi, E. et al. Usefulness of CGM-derived metric, the glucose management indicator, to assess glycemic control in non-white individuals with diabetes. Diabetes Care 44, 2787–2789 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Xu, Y., Bergenstal, R. M., Dunn, T. C., Ram, Y. & Ajjan, R. A. Interindividual variability in average glucose-glycated haemoglobin relationship in type 1 diabetes and implications for clinical practice. Diabetes Obes. Metab. 24, 1779–1787 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Xu, Y. et al. Personal glycation factors and calculated hemoglobin A1c for diabetes management: Real-world data from the diabetes prospective follow-up (DPV) registry. Diabetes Technol. Ther. 23, 452–459 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fabris, C., Heinemann, L., Beck, R., Cobelli, C. & Kovatchev, B. Estimation of hemoglobin A1c from continuous glucose monitoring data in individuals with type 1 diabetes: Is time in range all we need? Diabetes. Technol. Ther. 22, 501–501 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Herman, W. H., Cohen, R. M. & Update Racial and ethnic differences in the relationship between HbA1c and blood glucose: Implications for the diagnosis of diabetes. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 97, 1067–1072 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hall, H. et al. Glucotypes reveal new patterns of glucose dysregulation. PLoS Biol. 16, e2005143 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.York, B., Kujan, M., Conneely, C., Glantz, N. & Kerr, D. Farming for life: Pilot assessment of the impact of medical prescriptions for vegetables on health and food security among latino adults with type 2 diabetes. Nutr. Health 26, 9–12 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kerr, D. et al. Farming for life: Impact of medical prescriptions for fresh vegetables on cardiometabolic health for adults with or at risk of type 2 diabetes in a predominantly Mexican-American population. BMJ Nutr. Prev. Health 3, 239–246 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Aleppo, G. et al. Estimation of hemoglobin A1c from continuous glucose monitoring data in individuals with type 1 diabetes: Is time in range all we need? Diabetes Care. 40, 538–545 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sato Imuro, S. E. et al. Temporal changes in bio-behavioral and glycemic outcomes following a produce prescription program among predominantly Hispanic/Latino adults with or at risk of type 2 diabetes. Heliyon 9, e18440–e18440 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mauras, N. et al. A randomized clinical trial to assess the efficacy and safety of real-time continuous glucose monitoring in the management of type 1 diabetes in Young Children aged 4 to < 10 years. Diabetes Care 35, 204–210 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.The Juvenile Diabetes Research Foundation Continuous Glucose Monitoring Study. Continuous glucose monitoring and intensive treatment of type 1 diabetes. N. Engl. J. Med. 359, 1464–1476 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data from the Farming for Life (T2.1) and Digital Health (T2.2) datasets is available upon reasonable request. To gain access, data requestors will need to sign a data access agreement. Requests should be directed to wbevier@sansum.org.