Abstract

Evidences illustrate that cell senescence contributes to the development of pulmonary arterial hypertension. However, the molecular mechanisms remain unclear. Since there may be different senescence subtypes between PAH patients, consistent senescence-related genes (SRGs) were utilized for consistent clustering by unsupervised clustering methods. Senescence is inextricably linked to the immune system, and the immune cells in each cluster were estimated by ssGSEA. To further screen out more important SRGs, machine learning algorithms were used for identification and their diagnostic value was assessed by ROC curves. The expression of hub genes were verified in vivo and in vitro. Transcriptome analysis was used to assess the effects of silence of hub gene on different pathways. Three senescence molecular subtypes were identified by consensus clustering. Compared with cluster A and B, most immune cells and checkpoint genes were higher in cluster C. Thus, we identified senescence cluster C as the immune subtype. The ROC curves of IGF1, HOXB7, and YWHAZ were remarkable in both datasets. The expression of these genes was increased in vitro. Western blot and immunohistochemical analyses revealed that YWHAZ expression was also increased. Our transcriptome analysis showed autophagy-related genes were significantly elevated after silence of YWHAZ. Our research provided several prospective SRGs and molecular subtypes. Silence of YWHAZ may contribute to the clearance of senescent endothelial cells by activating autophagy.

Keywords: Senescence-related genes, Pulmonary arterial hypertension, Machine learning, Molecular subtypes, Immune infiltration, Transcriptome analysis

Subject terms: Genome informatics, Cellular signalling networks

Introduction

Idiopathic pulmonary arterial hypertension (IPAH) is regarded as a rare disease with poor prognosis. Wherein, the 5-year mortality of patients with IPAH is only 50%1. Research shows that tissue hypoxia, arterial spasm and vascular remodeling result in increased pulmonary vascular resistance, and ultimately lead to right heart failure2. According to the present definition, the mean pressure of the pulmonary artery (mPAP) of IPAH is ≥ 20 mmHg3. Despite great advances in the research of IPAH, its mortality rate remains high, with unclarified molecular mechanisms4. Therefore, an efficient molecular marker for early diagnosis and treatment is urgently needed.

Cellular senescence is a stress response, characterized by the cessation of normal cell division and the loss of cell proliferation capacity5,6. Evidences indicate that pulmonary artery endothelial and smooth muscle cell senescence contribute to the pulmonary artery remodeling and development of pulmonary hypertension7,8. Senescent cells promote vascular inflammation and fibrosis by modifying the senescence-associated secretory phenotype (SASP)9. In addition, senescent pulmonary endothelial cells (PAECs) decrease the production of nitric oxide, but increase the release of endothelin-110. Hence, it contributes to increase the blood pressure in the pulmonary artery. Frataxin was intimately related to endothelial cell senescence in PAH, and the a lack of frataxin exacerbatesendothelial senescence11. The senolytic drug ABTABT26 induced the apoptosis of senescent endothelial cells,to reverse hemodynamic and structural changes in PAH12. However, a recent study found that elimination of senescent endothelial cells by senolytic drug impaired the control of pulmonary vascular cell growth and promoted the development of pulmonary hypertension13. Therefore, further exploration of the link between senescence phenotype and pulmonary hypertension, may contribute to clarifying the molecular mechanisms involved and identifying a potential therapeutic targets for IPAH.

This study systematically analyzed the senescence-related genes (SRGs) that were significant differences between IPAH patients and the normal controls. Since there may be different senescence subtypes between PAH patients, an unsupervised clustering algorithm was used to cluster SRGs to explore senescence-related gene signatures and molecular subtypes with diverse immune infiltrations in IPAH. To further identify core genes, the SRGs were screened by LASSO and SVM algorithms to provide insights into the development of early diagnosis and targeted therapy for IPAH.

Method

Data resource

The datasets GSE1519714, GSE11343915 were obtained from the GEO database. Microarray data of GSE15197, which contains lung tissue samples from 13 normal samples and 18 IPAHs, were used as the identification cohort. GSE113439 was used as the verification cohort, and included lung tissue from 6 patients with IPAH and 11 normal controls. The details of the above two datasets are summarized in Table 1. A total of 307 and 213 SRGs were obtained from the GenAge16 and MSigDB17 databases, respectively. The online web tool GEO2R18 was used to explore differential expression. The differential expressed genes (DEGs) were defined as those whose adjusted p-value < 0.05 and |Log2FC|> 1. Microarray data of GSE15197 was used to identify the differential expression of SRGs between IPAH patients and normal controls, and the dataset GSE113439 dataset was used to assess the diagnostic value of the hub genes. Hub genes, also known as core genes, are defined as the genes most closely associated with disease.

Table 1.

Information of two GEO datasets involving normal samples and IPAH patients.

Gene enrichment analysis

Gene Ontology (GO) and Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) pathway enrichment analyses were used to investigate the DEGs with the “ClusterProfiler” package19 in R software (4.2.2). For the GO and KEGG enrichment analyses, the p-value threshold was set to less than 0.05, “hsa” was selected for species, and the genes were annotated with “org.Hs.eg.db”.

Consensus cluster and ssGSEA analysis

An unsupervised clustering algorithm was used to cluster SRGs of the GSE15197 dataset by “Consensus Cluster Plus” R package20. To understand the immune status of different senescence clusters, single sample gene set enrichment analysis (ssGSEA) was used to evaluate the abundance of marker genes in immune cells in each cluster. The ssGSEA algorithm was carried out using a “GSVA” package. The various marker genes in immune cells were derived from Charoentong et al.21. The marker genes in immune cells are visible in the material file we provided (Supplementary Table 1). For ssGSEA analysis, Gaussian was chosen for the kernel function to normalize the expression profiles of marker genes in immune cells within the samples, and then the corresponding ssGSEA rank for each gene was calculated.

Screening and assessment of the SRGs

The LASSO and support vector machines (SVM)22 arithmetics were used independently to identify the SRGs. The LASSO model is a regression analysis algorithm that applies regularization to variable selection23 which was carried out by “glmnet” package. LASSO regression was used to fit a binary logistic regression model with L1 regularization, and negative log-likelihood was used as a performance metric. With this model, we performed tenfold cross-validation on IPAH samples and normal samples to select the hub genes. Coefficient profiles are generated from the log(λ) sequence24. A vertical line was drawn at the selected value as optimized (λ). Draw a dashed line at the optimal value using the minimum criterion and 1 standard error of the minimum criterion (1- SE criterion). The minimum λ was used to screen the hub genes in this study. SVM-RFE is a widely utilized supervised machine learning algorithm for categorization and regression using the “e1071” package25. The SVM-RFE algorithm searches for the optimal variables according to the deletion of the feature vector, which was compared by the average misjudgement rate of 10 cross-validations26. Finally, we used the intersection of the LASSO and SVM-RFE algorithms as hub genes for subsequent analysis. ROC curve analysis was subsequently performed to assess the diagnostic value of the hub genes, and the dataset GSE113439 dataset was used to verify its diagnostic efficiency. To further assess the expression of these characterized genes in other lung disease, we analyzed the COPD dataset (GSE21359). GSE21359 contains small airway epithelial samples from 112 controls and 23 COPD patients.

Construction of miRNA-mRNA and TF-mRNA networks

By further exploring upstream factors that regulate key genes, we predicted miRNAs and transcription factors that regulate these genes. The online networking tool NetworkAnalyst27 was used to explore potential miRNAs-mRNA and transcription factor (TF) -mRNA regulatory mechanisms. NetworkAnalyst is an integrated website that links gene sets to other databases for prediction. Specifically, transcription factor targets were obtained from the JASPAR TF binding site profile database. Comprehensive experimentally validated miRNA-gene interaction data were derived from miRTarBase (vision 9.0).

Construction of gene co-expression matrix and identification of core modules

The WGCNA package28 was used to investigate the correlation between the key modules and IPAH. By calculating Pearson correlations between all gene pairs in the IPAH group and the normal group, an adjacency matrix was created and key modules were identified according to correlation coefficients. The driver genes in the turquoise module were screened according to a gene significance (GS) > 0.5 and module membership (MM) > 0.8.

Experimental validation

Animal models

A total of 16 male Sprague–Dawley rats (220–250 g) were obtained from the Experimental Laboratory Animal Centre of Guangxi Medical University. All the animals were housed in a room with 12 h of alternating light and dark and a controlled temperature (22–25 °C). Food and water were available ad libitum. We randomly divided 16 male Sprague Dawley rats into control and monocrotaline (MCT) groups. The control and MCT groups were subjected to a single intraperitoneal injection of normal saline or MCT (60 mg/kg), respectively29. The MCT was dissolved with 1 N HCl, followed by 0.5 N NaOH to adjust the pH to 7.4, and finally diluted with distilled water. After 4 weeks, we established a rat model of PAH. All the experiments were performed in accordance with the relevant named guidelines and regulations, and all the animal experiments complied with the ARRIVE guidelines. All animal experiments were approved by the Ethics Committee of Guangxi Medical University (No. 202309877).

Quantitative real-time PCR (qPCR)

We extracted RNA from the lung tissues of rats or cells for qPCR to evaluate the hub gene’s expression. Total RNA was extracted via Trizol reagent. Then, the RNA was reverse transcribed to cDNA by HiScript®II Q RT SuperMix (Vazyme, China). RT-qPCR was performed on a real-time PCR system using ChamQ SYBR qPCR Master Mix (Vazyme, China). The 2−∆∆Ct method was used to quantify the expression of hub genes. The qPCR primers provided by Sangon Biotech are listed in Table 2.

Table 2.

Primer sequences for quantitative real-time PCR.

| Gene | Forward | Reverse |

|---|---|---|

| Rat YWHAZ | 5'-ACTACTACCGCTACTTGGCTGAGG-3' | 5'-TTCTTGGTATGCTTGCTGTGACTGG-3' |

| Rat IGF1 | 5'-ATTCGGAGGGCACCACAGAC-3' | 5'-CTTCAGCGGAGCACAGTACATC-3' |

| Rat HOXB7 | 5'-CTGCCTCACCGAAAGACAGATCAAG-3' | 5'-CTCTTCCTCCTCGTCCGCTTCC-3' |

| Rat p21 | 5'-TGGTGGCGTAGGCAAGAGTG-3' | 5'-CTGCTGTGTCGAGAATATCCAAGAG-3' |

| Rat p53 | 5'-GGCTCCGACTATACCACTATCCAC-3' | 5'-GTCCCGTCCCAGAAGATTCCC-3' |

| Rat β-actin | 5'-GGAGATTACTGCCCTGGCTCCTA-3' | 5'-GACTCATCGTACTCCTGCTTGCTG-3' |

Western blot

The total protein was extracted from lung tissue or cells using RIPA buffer (Roche) supplemented with protease inhibitors and quantified by BCA protein assay reagent (Beyotime, China). The proteins were separated on 10–15% SDS‒polyacrylamide gels and transferred to a polyvinylidene fluoride membranes. The membranes were blocked with 5% non-fat milk for one hour and incubated with YWHAZ (Abmart, China,1:800), and β-actin (Affinity, China, 1:5000) overnight. The membranes were then incubated with secondary antibody at room temperature for 1 h.

Immunohistochemistry

Lung tissues were immersed in xylene and different concentrations of ethanol dilutions, respectively, and then blockedwith 3% bovine serum albumin (BSA) for 30 min. The tissues were incubated with YWHAZ antibody (dilution 1:200) overnight at 4 ºC. The tissues were then incubated with secondary antibody at room temperature for 1 h. Then, the sections were washed with PBS, stained with diaminobenzidine, and observed under a microscope. The resulting images were analyzed using Image-Pro Plus software and quantified by immunohistochemistry.

Pulmonary artery endothelial cells primary isolation and culture

The pulmonary artery was isolated from the lung tissue of SD rats. After the outer layer of fibrous connective tissue was removed, it was dissected into small pieces of adherent wall and then inverted. Afterward, the culture flasks containing the small arterial pieces were cultured in a cell culture incubator at 37 °C. The flasks were turned over after 2 h, and the medium was changed every 3 days. After about 1 week, the cells were grown to 70–80% confluency, digested with 0.25% trypsin to generate a cell suspension, passaged, counted and inoculated into 6-well plates at a density of 1 × 10 ~ 6/well for the subsequent intervention experiments.

Cell culture and treatment

The purity of the isolated PAECs was detected by immunofluorescence staining with VIII antibody. After incubation in serum-free medium for 24 h, PAECs were transfected with YWHAZ siRNA or empty vector (siNC) by lipo 3000 for 24 h to inhibit YWHAZ expression. Then, PAECs were exposed to normoxia (21% O2) or hypoxia (3% O2) for 24 h.

Transcriptome analysis

RNA extracted from cells using Trizol (Invitrogen). Total RNA quality was estimated with a Qubit RNA detection kit (Life, Q32855). Intact mRNA was isolated by magnetic bead purification kit for total RNA (YEASEN, China) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Amplified cDNA was prepared with DNA selection beads (YEASEN, China) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. After testing and quality control, RNA sequencing was conducted on an MGI sequencing platform library (BGI, China).

Statistical analysis

All data analyses were conducted in RStudio (“version 4.2.2”) and GraphPad (“version 8.1”). The normally distributed variables were analyzed via independent Student’s t tests, and the nonnormally distributed variables were performed using Wilcoxon rank sum tests. One-way analysis of variance or the Kruskal–Wallis test, as appropriate, was used for comparisons of more than two groups. The correlation coefficients of different variables were evaluated by Pearson correlation analysis. A two-sided p-value less than 0.05 was regarded as statistically significant.

Results

Identification of DEGs between IPAH patients and normal controls

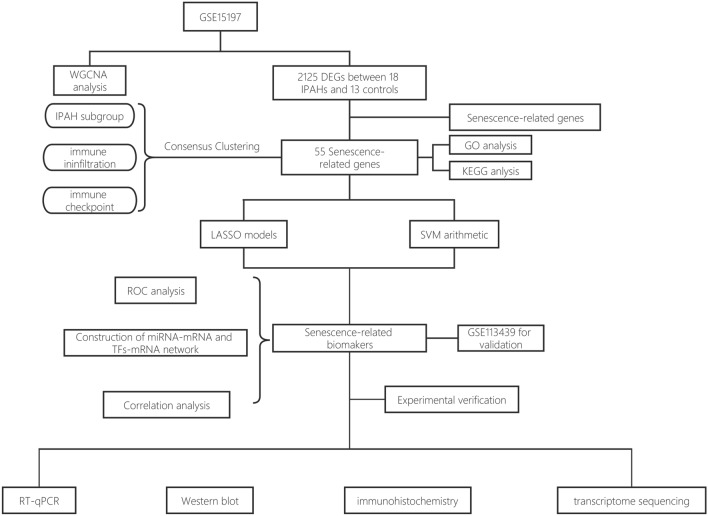

The flow chart of this study was showed in Fig. 1. There were 2125 DEGs in GSE15197, 1124 of which were upregulated and 1001 of which were downregulated. All DEGs were presented in the heatmap and bar plot (Supplementary Fig. 1A, B). The results of the differential analysis of the GSE15197 dataset from GEO2R could be seen in Supplementary Table 2.

Fig. 1.

The flow chart of the present study.

Identification of SRGs and enrichment analysis

A total of 55 SRGs were obtained from the intersection between DEGs and senescence genes (Supplementary Fig. 1C). GO analysis, revealed that these genes were enriched in aging, epithelial cell proliferation, the regulation of epithelial cell proliferation, cellular senescence, and DNA-binding transcription factor binding (Supplementary Fig. 2A, B). The KEGG enrichment analysis showed those DEGs were mainly associated with pathways associated with p53, MAPK, AGE-RAGE, HIF-1, Fox, proteoglycans in cancer, and PI3K-Akt (Supplementary Fig. 2C, D).

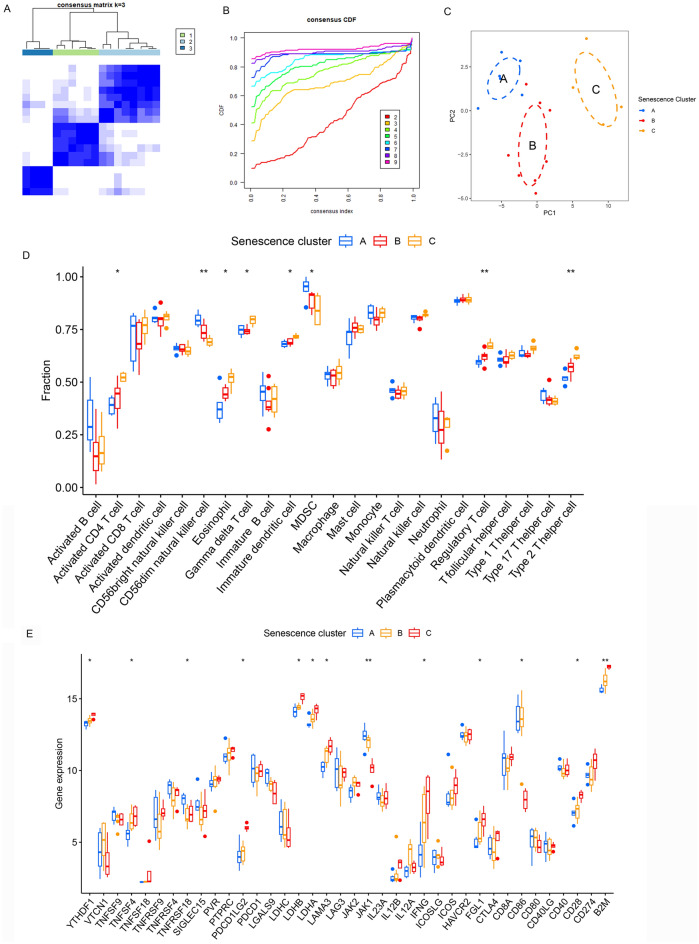

Consensus cluster analysis of SRGs in IPAH

Consensus unsupervised cluster analysis of 55 SRGs was performed to further explore different senescence patterns in IPAH. Consistent cluster analysis showed that the optimal number of subtypes was 3, as determined by the cumulative distribution function (CDF) (Fig. 2A, B). The three senescence subtypes were named senescence cluster A, B, and C. Principal component analysis (PCA) revealed that there was a remarkable difference among the different subtypes (Fig. 2C).

Fig. 2.

Consensus cluster analysis of SRGs in IPAH. (A) Consensus matrices of the 55 senescence-related DEGs for k = 3. (B) Cumulative distribution function (CDF) showing each consensus distribution. (C) Principal component analysis (PCA) of three subtypes. (D) Difference analysis of immune cells in senescence subtypes by Kruskal–Wallis test. (E) Difference analysis of immune checkpoints in senescence subtypes by Kruskal–Wallis test. *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; and ***p < 0.001.

Differences in immunological features across senescence subtypes

We evaluated the abundance of immune infiltration in the above three senescence subtypes. Compared with those in cluster A, the infiltration levels of most immune cells were greater in cluster C (Fig. 2D). As shown in Fig. 2E, the expression of most checkpoint genes was significantly upregulated in cluster C compared with cluster A. Thus, we identified senescence cluster C as the immune subtype, senescence cluster B as the median immune subtype, and senescence cluster A as the non-immune subtype.

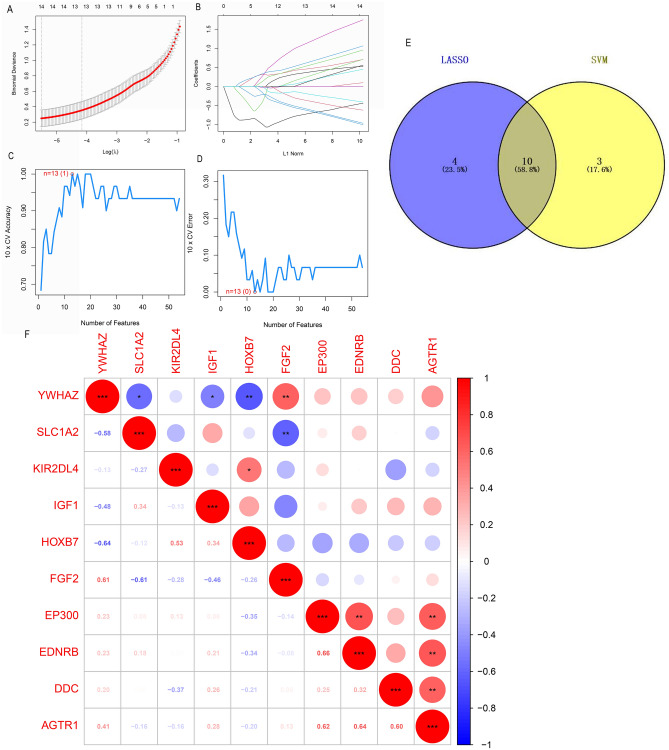

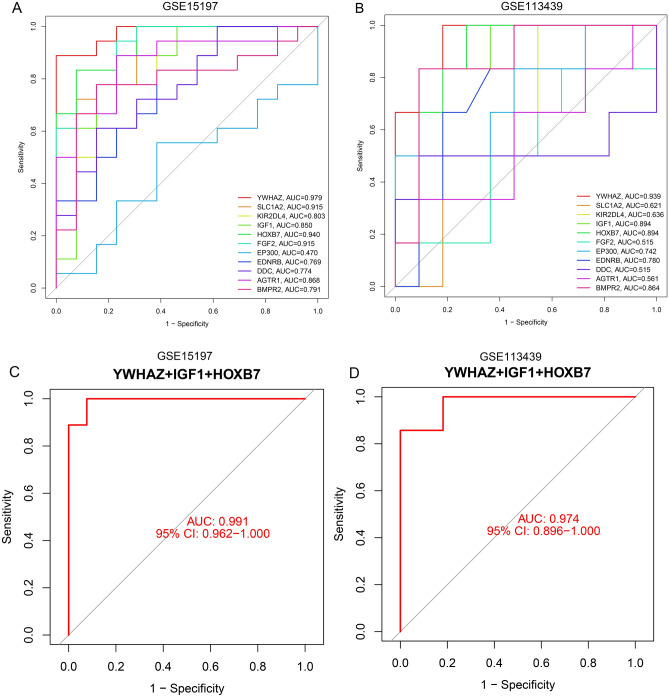

Screening and assessment of SRGs

The LASSO regression model identified 14 characteristic genes from 55 SRGs (Fig. 3A, B) and SVM arithmetic selected 13 feature DEGs (Fig. 3C, D). Ten SRGs were identified by intersecting the results of the above two machine-learning methods (Fig. 3E). Pearson correlation analysis showed a strong positive correlation between YWHAZ and FGF2, and a strong negative correlation between YWHAZ and HOXB7 (Fig. 3F). The diagnostic value of the 10 hub genes was evaluated in the GSE15197 dataset. We further validated the discriminability of the 10 hub genes to serve as biomarkers of IPAH in the GSE113439 dataset. Discriminatory ability was visualized by the ROC curve (Fig. 4A and B). The area under the curve for BMPR2 in the GSE15197 and GSE113439 datasets also has relatively robust predictive powers of 0.791 and 0.864, respectively. The ROC curves of IGF1, HOXB7, and YWHAZ were remarkable in the GSE15197 and GSE113439 datasets, and thus might serve as biomarkers of IPAH. In addition, we found that the prediction value was further improved by joint prediction (0.991 and 0.974, respectively) (Fig. 4C and D). Among these characterized genes, only SLC1A2, and IGF1 were highly expressed in COPD patients (Supplementary Fig. 3A and B). However, further ROC curve analysis revealed that these characterized genes were not well distinguished for COPD patients, and the area of ROC curves was only 0.461–0.692 (Supplementary Fig. 3C).

Fig. 3.

Screening senescence-relating hub genes. (A, B) Screening of gene signatures from senescence-relating genes using LASSO regression. (C, D) Screening of gene signatures from senescence-relating genes by SVM algorithm. (E) The Venn diagram of hub genes shared by LASSO, and SVM-RFE. (F) The correlation analysis of hub genes by Pearson correlation analysis. Red dots represent positive correlation and blue dots represent negative correlation. *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; and ***p < 0.001.

Fig. 4.

Evaluation of diagnostic accuracy of hub genes for IPAH. (A) ROC curves analysis of hub genes in GSE15197. (B) ROC curves analysis of hub genes in GSE113439. (D) ROC curves for evaluating joint diagnostic accuracy of YWHAZ, IGF1, and HOXB7 in the GSE15197 (C) and GSE113439 (D).

Construction of miRNA-mRNA and TF-mRNA networks

The miRNA-mRNA regulatory networks and the potential TF-mRNA regulatory mechanism were shown in Supplementary Fig. 4. There were 97 miRNAs that regulate YWHAZ, 26 miRNAs that take over HOXB7 and 14 miRNAs that regulate IGF1. Among them, hsa-mir-1-3p could simultaneously regulate YWHAZ, HOXB7 and IGF1. Similarly, the transcription factors YY1 and FOXC1 could simultaneously regulate YWHAZ, HOXB7 and IGF1. In summary, miRNAs and TFs may regulate the senescence process by regulating the above genes.

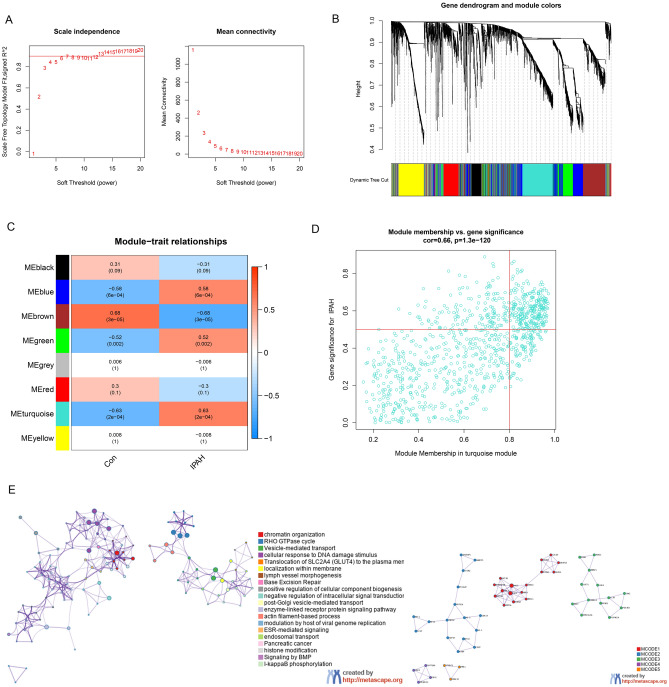

Construction of genes co-expression matrix

All genes were used to construct co-expression matrices. The soft threshold power of β = 6 (scale independence = 0.9) was applied to determine the scale-free network (Fig. 5A). According to our selection criteria, eight modules were identified (Fig. 5B). To evaluate the interactive links between the 8 modules, we computed the characteristic genes of the 8 modules and quantified their co-expression similarity according to their correlation clustering. Among these 8 modules, the turquoise module (290 genes) presented the highest positive correlation with IPAH (R = 0.63, p = 0.0002) (Fig. 5C). The scatterplot showed the close relationship between the MM and GS of the turquoise module (R = 0.66, p = 1.3e-120; Fig. 5D). The enrichment analysis of the turquoise module gene set can be seen in Fig. 5E. The genes of this module were mainly enriched in intracellular signaling transduction, histone modification, I-kappaB phosphorylation, etc.

Fig. 5.

The WGCNA analysis and key modules (A) Determining the soft threshold power for the scale-free fit index. (B) The hierarchical cluster analysis of DEGs. Each color represents one co-expression module. (C) The correlation of IPAH with the modules. Red dots represent positive correlation and blue dots represent negative correlation. (D) Scatterplot of Module Membership (MM) versus GS in the turquoise module for IPAH. (E) The enrichment analysis of the turquoise module genes.

Experimental validation

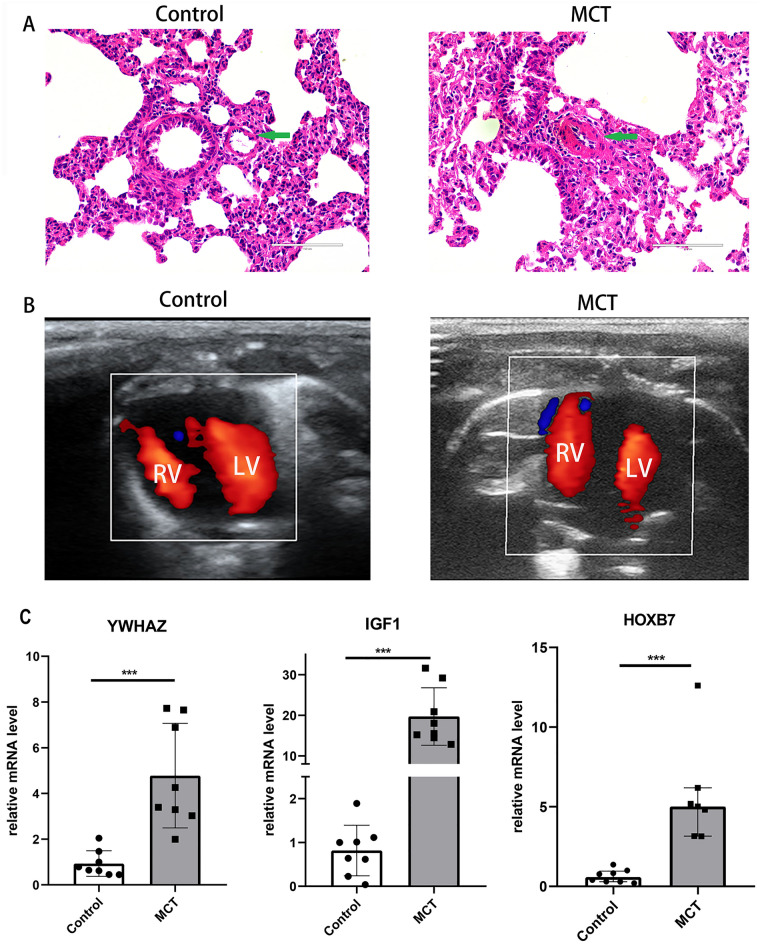

Hub gene mRNA expression

To further verify the expression level of hub genes, we further established MCT-induced PAH model in rats. HE staining of the control and MCT groups can be seen in Fig. 6A. In the MCT group, the pulmonary wall arteriole was thickened and the vascular lumen was narrowed or blocked. The echocardiography results for the control and MCT group were shown in Fig. 6B. In the MCT group, the right heart load increased significantly. Compared with those in the control group, the mRNA levels of YWHAZ, IGF1 and HOXB7 were increased dramatically in the MCT-induced PAH model, as determined by qPCR (Fig. 6C).

Fig. 6.

Experimental validation. (A) HE staining for control (left)and MCT group (right). In the MCT group, the pulmonary wall arteriole was thickened and the vascular lumen was narrowed or blocked. (B) The echocardiography for control (left) and MCT group (right). The green arrow points to the pulmonary artery. In the MCT group, the right heart load increased significantly. (C) The relative mRNA level of hub genes between the control and MCT groups by RT-qPCR (YWHAZ and IGF1 by t test, HOXB7 by wilcoxon test). (n = 7–8).

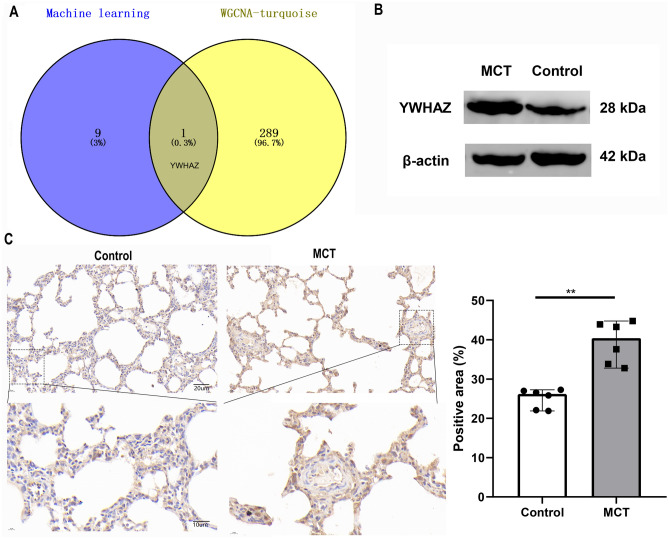

The YWHAZ is positively associated with PAH

To further identify the hub genes positively associated with IPAH, two machine learning methods were combined with the in WGCNA turquoise module gene set (Pearson correlation coefficient 0.63) (Fig. 7A). We identified a hub gene (YWHAZ) positively associated with the disease, which was subsequently verified. The protein level of YWHAZ was increased significantly in the MCT groups (Fig. 7B). In immunohistochemical analysis, the positive area of YWHAZ in the MCT group was also significantly higher than that of the normal group (Fig. 7C).

Fig. 7.

YWHAZ positively associated with PAH model. (A) The intersection result of WGCNA turquoise module and machine learning. (B) The protein level of YWHAZ between the control and MCT groups. (C) The positive area of YWHAZ between the control and MCT groups by t test (n = 6). (Note: *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001).

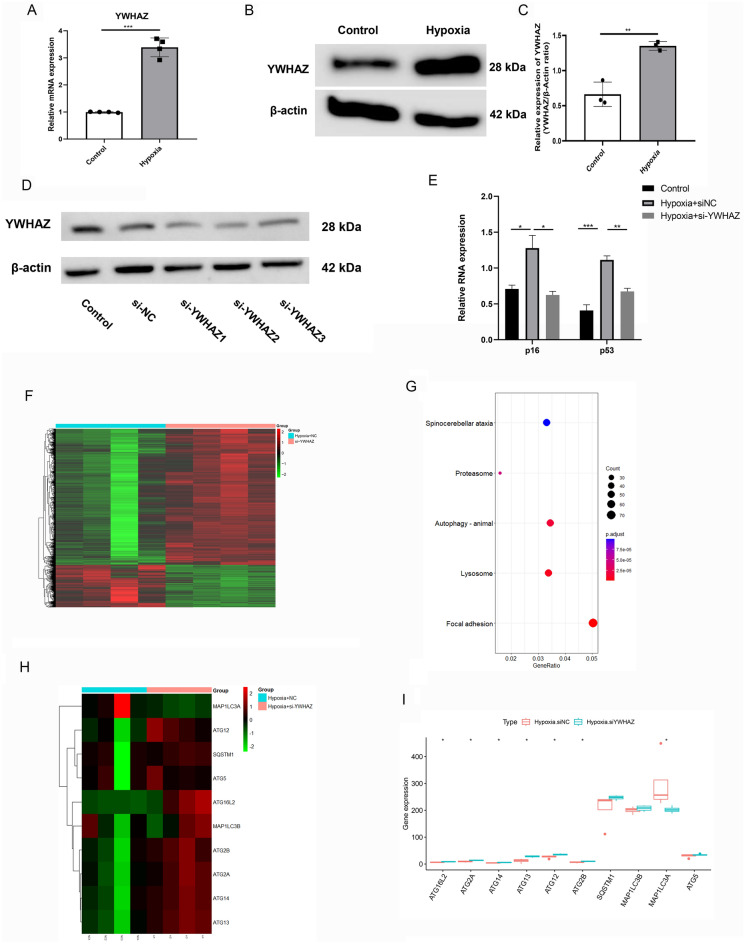

YWHAZ increased in hypoxic treatment of PAECs

To simulate the condition of PAECs in vivo, PAECs were exposed to normoxia or hypoxia (3% O2) for 6 h. The mRNA and protein levels of YWHAZ were upregulated in PAECs exposed to hypoxia (Fig. 8A, B and C). The images of original gels and blots in the manuscript could be seen in supplementary Fig. 5.

Fig. 8.

YWHAZ increased in hypoxic treatment of PAECs. (A) qPCR analysis of YWHAZ expression in PAECs by t test (n = 4). (B and C) The protein expression level of YWHAZ in PAECs by t test (n = 3). (D) The silencing effect of siRNA. (E) Silence of YWHAZ decreased expression of SASP (p21 and p53) (n = 3). (F) The heatmap of DEGs. Red represents up-regulated genes and green represents down-regulated genes. (G) The KEGG enrichment analysis of DEGs. (H) The heatmap of autophagy-related genes. Red represents up-regulated genes and green represents down-regulated genes. (I) Autophagy-related genes were significantly elevated after knockdown of YWHAZ. (Note: *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001).

Silencing YWHAZ decreased expression of SASP and activated the autophagy pathway

The silencing effect of the siRNA was shown in Fig. 8D. Finally, si-YWHAZ2(Forward: GCAUGAAGUCUGUCACUGAGCTT, Reverse: GCUCAGUGACAGACUUCAUGCTT) was selected for siRNA intervention. Silencing YWHAZ decreased the expression of SASP (p21 and p53), as shown in Fig. 8E. Subsequently, transcriptome sequencing was performed on PAECs after siRNA intervention. The threshold of significance was set to a p value < 0.05 and |logFC|> 1. There were 3550 DEGs as showed in heatmap (Fig. 8F), 2707 of which were upregulated and 843 of which were downregulated. KEGG enrichment analysis was used to assess the effects of YWHAZ silencing on different pathways. Enrichment analysis showed that the biological processes such as autophagy signaling pathway, and focal adhesion were significantly enriched after YWHAZ was silenced (Fig. 8G). Therefore, we further evaluated the alterations in the expression of autophagy-related genes upon YWHAZ silencing. The expression of autophagy-related genes was significantly elevated after YWHAZ was silenced (Fig. 8H and I).

Discussion

In this study, we mainly probe the correlation between SRGs and IPAH. A total of 55 SRGs were acquired from the 2125 DEGs in the GSE15197 dataset. A consensus unsupervised cluster analysis was performed for 55 SRGs, and three senescence subtypes were identified as senescence cluster A, B, and C. We found that immune cell abundance also differed significantly between senescence score subgroups. The infiltration degree of CD56dim NK cells was lower in the group with a lower senescence score. A previous study shown that senescence leads to altered NK cell phenotypes, such as increased numbers of CD56 dim NK cell subpopulations and decreased numbers of CD56 bright NK cells30. This may also mean that the lower the senescence score is, the milder the degree of senescence. Moreover, we found that senescence cluster C had more severe immune cell abundance and higher immune checkpoint expression than the other subtypes did. This may also be due to a lighter degree of senescence. As aging progresses, it also causes an alteration in the immune response and immune remodeling31. On the basis of these findings, we speculated that there may be three senescence phenotypes in pulmonary hypertension, namely, the senescence subtype, median senescence subtype, and non-senescence subtype, which correspond to the non-immune subtype, median immune subtype, and immune subtype, respectively. Immune cells have a positive effect on senescent cells, and recent research has shown that transplanting young immune cells into aging mice could reverse the aging process32. A randomized controlled trial also showed that autoinfusion of NK cells could improve immune regulation and clear senescent cells33. These studies partly explain why appropriate inflammatory responses can protect against or prevent cellular senescence, which may also contribute to alleviating lung vessel remodeling.

Based on the above SRGs, the candidate hub genes were identified by both the LASSO and SVM algorithms. HOXB7, IGF1, and YWHAZ, especially the latter, showed significant discriminative ability in the GSE15197 and GSE113439 datasets. Homeobox B7 (HOXB7), a member of the homeobox gene family, can regulate the proliferation, invasion, migration and angiogenesis of tumor cells34,35. Overexpression of HOXB7 promoted myeloma-related angiogenesis and increased the expression of angiogenic genes36. A study showed FOXF1 could promote fetal lung morphogenesis by activating HOXB737. Another study reported significant differences in HOXB7 mRNA and protein levels in the microvasculature of the brain and spinal cord, which may indicate that HOXB7 plays an important role in endothelial cells38.

Insulin-like growth factor-1 (IGF-1) is a hormone that regulates cell differentiation and proliferation39. In the current study, the expression level of IGF-1 was significantly elevated in the MCT-induced PAH model than in the normal group. Yang et al. found that IGF-1 activated the AKT signaling pathway to promote pulmonary hypertension in neonatal mice40. Through inhibition of IGF-1, the right ventricular hypertrophy and pulmonary vascular remodeling were attenuated in a hypoxia-induced PAH model in mice. Over-expression of miR-22341 or miR-322-5p42 reduced right ventricular hypertrophy and improved right cardiac function by inhibiting IGF expression. However, in another study, researchers found that loss of IGF-1 did not influence hypoxia-induced PH in adult mice43. Therefore, the effect of IGF-1 on pulmonary hypertension is extremely complex and still needs to be further explored.

Tryptophan 5-monooxygenase-activating protein zeta (YWHAZ), a member of the 14–3-3 protein family, is involved in a host of signal transduction44. Increasing evidences have showed that YWHAZ promoted tumor cell proliferation45,46, migration47, cell cycle regulation48 and other biological behaviors. Wang et al. found expression of 14–3-3β was significantly elevated in peripheral blood mononuclear cells with pulmonary hypertension49. In addition, their study also found that 14–3-3β expression was positively related to the mean pulmonary artery pressure (R2 = 0.8783; p < 0.001). Although different from our study, these findings also suggest that 14-3-3 families are crucial for the development of pulmonary hypertension. In the present study, we observed that YWHAZ was closely related to the PI3K-AKT pathway via KEGG pathway analysis. Shi et al. found that YWHAZ could activate the PI3K-Akt1 signaling pathway to promote ovarian cancer metastasis50. A study on gastric cancer found that YWHAZ suppression could inhibit the activation of PI3K/AKT/mTOR signaling51. Previous studies have reported the PI3K/ AKT pathway is involved in pulmonary vascular remodeling, and that inhibition of AKT phosphorylation weakens pulmonary vascular remodeling52,53. In the WGCNA analysis, we found a significant positive correlation between YWHAZ and IPAH. To validate the findings of the biological information analysis, we subsequently conducted qPCR and immunohistochemistry. In the animal model, the expression of YWHAZ also increased dramatically in the IPAH group, suggesting that our results are reliable. In addition, transcriptome analysis revealed that silencing YWHAZ could activate the autophagy pathway. Autophagy plays an important role in cell homeostasis, and the inhibition of autophagy leads to an increase in reactive oxygen species, which leads to cell senescence54. A recent study shown that the activation of autophagy could protect against age-related diseases55. Thus, silencing YWHAZ may contribute to the clearance of senescent endothelial cells by activating autophagy. Endothelial cell dysfunction and phenotypic changes are considered important factors that initiate pulmonary hypertension56. Unlike the use of senolytic drugs, elimination of senescent endothelial cells by appropriate activation of autophagy may be beneficial for improving the progression of pulmonary hypertension. Therefore, on the basis of the above studies, we assume that YWHAZ may be a novel potential therapeutic target for pulmonary arterial hypertension.

MicroRNAs are small, non-coding RNAs that negatively regulate gene expression57. Recent studies have reported that miRNA is closely related to the development and progression of pulmonary arterial hypertension58,59. miR-214-3p was reported to affect hypoxia-induced pulmonary artery smooth muscle proliferation60. Downregulation of miR-214-3p significantly reduced proliferation and promoted apoptosis in pulmonary artery smooth muscle. A recent study found that the expression of miR-93-5p was associated with the severity of chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension (CTEPH)61. Furthermore, Guo et al. found the level of miR-22 in the plasma of CTEPH patients was significantly decreased and had certain diagnostic accuracy62. Thus, the epigenetic regulatory mechanism is highly important in the treatment of pulmonary hypertension. In summary, our research identified several potential senescence-related genes and molecular subtypes. And silence of YWHAZ may contribute to the clearance of senescent endothelial cells by activating autophagy. However, there are several limitations to this study. First, it is unclear whether the difference in gene expression is related to gender or race. Second, the author did not provide specific age information in the datasets, so we could not further correct for the effects of age on hub genes. The prevalence of IPAH is relatively low and it is difficult to obtain lung tissue from IPAH patients. Lung tissue specimens could be obtained from only a subset of patients who are able to undergo lung transplantation. Thus, the sample size of the datasets we analyzed was relatively limited. In future research, it is necessary to increase the sample size and conduct multicenter studies. Finally, further in vitro and in vivo experiments are needed to further validate our findings in transcriptome sequencing. We believe that, despite the limited sample size, our study findings offer new insights and provide some valuable hypotheses for future research endeavors.

Supplementary Information

Author contributions

Conceptualization, Zhong-yuan Meng; Formal analysis, Juan Liao and Hong Wen; Investigation, Chuang-hong Lu, Jing Li and Juan Liao; Methodology, Chuang-hong Lu and Jing Li; Software, Zhong-yuan Meng; Supervision, Feng Huang and Zhi-yu Zeng; Validation, Chuanghong Lu; Writing – original draft, Zhong-yuan Meng; Writing – review & editing, Yuan Li and Hong Wen, Feng Huang and Zhi-yu Zeng.

Funding

This work was supported by Guangxi Key Laboratory of Precision Medicine in Cardio-Cerebrovascular Diseases Control and Prevention (19–245-34), Guangxi Clinical Research Center for Cardio-Cerebrovascular Diseases (AD17129014).

Data availability

The data used in this analysis are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

This authors contributed equally: Zhong-Yuan Meng and Chuang-Hong Lu.

Contributor Information

Feng Huang, Email: huangfeng@sr.gxmu.edu.cn.

Zhi-Yu Zeng, Email: zengzhiyu@gxmu.edu.cn.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41598-024-72979-8.

References

- 1.Thenappan, T., Ormiston, M. L., Ryan, J. J. & Archer, S. L. Pulmonary arterial hypertension: Pathogenesis and clinical management. BMJ360, j5492. 10.1136/bmj.j5492 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Naeije, R., Richter, M. J. & Rubin, L. J. The physiological basis of pulmonary arterial hypertension. Eur. Respir. J.10.1183/13993003.02334-2021 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Humbert, M. et al. 2022 ESC/ERS Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of pulmonary hypertension. Eur. Heart J.43, 3618–3731. 10.1093/eurheartj/ehac237 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Beshay, S., Sahay, S. & Humbert, M. Evaluation and management of pulmonary arterial hypertension. Respir. Med.171, 106099. 10.1016/j.rmed.2020.106099 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mohamad Kamal, N. S., Safuan, S., Shamsuddin, S. & Foroozandeh, P. Aging of the cells: Insight into cellular senescence and detection methods. Eur. J. Cell Biol.99, 151108. 10.1016/j.ejcb.2020.151108 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Salama, R., Sadaie, M., Hoare, M. & Narita, M. Cellular senescence and its effector programs. Genes Dev.28, 99–114. 10.1101/gad.235184.113 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Culley, M. K. & Chan, S. Y. Endothelial senescence: a new age in pulmonary hypertension. Circ. Res.130, 928–941. 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.121.319815 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Roger, I., Milara, J., Belhadj, N. & Cortijo, J. Senescence alterations in pulmonary hypertension. Cells10.3390/cells10123456 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.van der Feen, D. E., Berger, R. M. F. & Bartelds, B. Converging paths of pulmonary arterial hypertension and cellular senescence. Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol.61, 11–20. 10.1165/rcmb.2018-0329TR (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jia, G., Aroor, A. R., Jia, C. & Sowers, J. R. Endothelial cell senescence in aging-related vascular dysfunction. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Mol. Basis Dis.10.1016/j.bbadis.2018.08.008 (1865). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Culley, M. K. et al. Frataxin deficiency promotes endothelial senescence in pulmonary hypertension. J. Clin. Invest.10.1172/JCI136459 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.van der Feen, D. E. et al. Cellular senescence impairs the reversibility of pulmonary arterial hypertension. Sci. Transl. Med.10.1126/scitranslmed.aaw4974 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Born, E. et al. Eliminating senescent cells can promote pulmonary hypertension development and progression. Circulation147, 650–666. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.122.058794 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rajkumar, R. et al. Genomewide RNA expression profiling in lung identifies distinct signatures in idiopathic pulmonary arterial hypertension and secondary pulmonary hypertension. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol.298, H1235-1248. 10.1152/ajpheart.00254.2009 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mura, M., Cecchini, M. J., Joseph, M. & Granton, J. T. Osteopontin lung gene expression is a marker of disease severity in pulmonary arterial hypertension. Respirology24, 1104–1110. 10.1111/resp.13557 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tacutu, R. et al. Human ageing genomic resources: new and updated databases. Nucl. Acids Res.46, D1083–D1090. 10.1093/nar/gkx1042 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Liberzon, A. et al. The molecular signatures database (MSigDB) hallmark gene set collection. Cell Syst.1, 417–425. 10.1016/j.cels.2015.12.004 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Barrett, T. et al. NCBI GEO: Archive for functional genomics data sets–update. Nucl. Acids Res.41, D991-995. 10.1093/nar/gks1193 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wu, T. et al. clusterProfiler 4.0: A universal enrichment tool for interpreting omics data. Innovation (Camb)2, 100141. 10.1016/j.xinn.2021.100141 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wilkerson, M. D. & Hayes, D. N. ConsensusClusterPlus: A class discovery tool with confidence assessments and item tracking. Bioinformatics26, 1572–1573. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btq170 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Charoentong, P. et al. Pan-cancer immunogenomic analyses reveal genotype-immunophenotype relationships and predictors of response to checkpoint blockade. Cell Rep.18, 248–262. 10.1016/j.celrep.2016.12.019 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sanz, H., Valim, C., Vegas, E., Oller, J. M. & Reverter, F. SVM-RFE: Selection and visualization of the most relevant features through non-linear kernels. BMC Bioinform.19, 432. 10.1186/s12859-018-2451-4 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dai, P. et al. Retrospective study on the influencing factors and prediction of hospitalization expenses for chronic renal failure in China based on random forest and lasso regression. Front. Public Health9, 678276. 10.3389/fpubh.2021.678276 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wu, L. et al. LASSO regression-based diagnosis of acute ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) on electrocardiogram (ECG). J. Clin. Med.10.3390/jcm11185408 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Huang, S. et al. Applications of support vector machine (SVM) learning in cancer genomics. Cancer Genom. Proteom.15, 41–51. 10.21873/cgp.20063 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wu, X. et al. Genetic analysis of potential biomarkers and therapeutic targets in ferroptosis from coronary artery disease. J. Cell. Mol. Med.26, 2177–2190. 10.1111/jcmm.17239 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zhou, G. et al. NetworkAnalyst 3.0: A visual analytics platform for comprehensive gene expression profiling and meta-analysis. Nucl. Acids Res.10.1093/nar/gkz240 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Langfelder, P. & Horvath, S. WGCNA: An R package for weighted correlation network analysis. BMC Bioinform.9, 559. 10.1186/1471-2105-9-559 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jin, H. et al. Astragaloside IV blocks monocrotaline-induced pulmonary arterial hypertension by improving inflammation and pulmonary artery remodeling. Int. J. Mol. Med.47, 595–606. 10.3892/ijmm.2020.4813 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Witkowski, J. M., Larbi, A., Le Page, A. & Fulop, T. Natural killer cells, aging, and vaccination. Interdiscip Top Gerontol Geriatr43, 18–35. 10.1159/000504493 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mogilenko, D. A., Shchukina, I. & Artyomov, M. N. Immune ageing at single-cell resolution. Nat. Rev. Immunol.22, 484–498. 10.1038/s41577-021-00646-4 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yousefzadeh, M. J. et al. An aged immune system drives senescence and ageing of solid organs. Nature594, 100–105. 10.1038/s41586-021-03547-7 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tang, X. et al. Characterization of age-related immune features after autologous NK cell infusion: Protocol for an open-label and randomized controlled trial. Front Immunol13, 940577. 10.3389/fimmu.2022.940577 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Huan, H. B. et al. HOXB7 accelerates the malignant progression of hepatocellular carcinoma by promoting stemness and epithelial-mesenchymal transition. J. Exp. Clin. Cancer Res.36, 86. 10.1186/s13046-017-0559-4 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Errico, M. C., Jin, K., Sukumar, S. & Care, A. The widening sphere of influence of HOXB7 in solid tumors. Cancer Res.76, 2857–2862. 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-15-3444 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Storti, P. et al. HOXB7 expression by myeloma cells regulates their pro-angiogenic properties in multiple myeloma patients. Leukemia25, 527–537. 10.1038/leu.2010.270 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ustiyan, V. et al. FOXF1 transcription factor promotes lung morphogenesis by inducing cellular proliferation in fetal lung mesenchyme. Dev. Biol.443, 50–63. 10.1016/j.ydbio.2018.08.011 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Molino, Y. et al. Gene expression comparison reveals distinct basal expression of HOX members and differential TNF-induced response between brain- and spinal cord-derived microvascular endothelial cells. J. Neuroinflammation13, 290. 10.1186/s12974-016-0749-6 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Obradovic, M. et al. Effects of IGF-1 on the cardiovascular system. Curr. Pharm. Des.25, 3715–3725. 10.2174/1381612825666191106091507 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yang, Q., Sun, M., Ramchandran, R. & Raj, J. U. IGF-1 signaling in neonatal hypoxia-induced pulmonary hypertension: Role of epigenetic regulation. Vascul. Pharmacol.73, 20–31. 10.1016/j.vph.2015.04.005 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Shi, L. et al. miR-223-IGF-IR signalling in hypoxia- and load-induced right-ventricular failure: A novel therapeutic approach. Cardiovasc. Res.111, 184–193. 10.1093/cvr/cvw065 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Connolly, M. et al. miR-322-5p targets IGF-1 and is suppressed in the heart of rats with pulmonary hypertension. FEBS Open Bio8, 339–348. 10.1002/2211-5463.12369 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sun, M., Ramchandran, R., Chen, J., Yang, Q. & Raj, J. U. Smooth muscle insulin-like growth factor-1 mediates hypoxia-induced pulmonary hypertension in neonatal mice. Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol.55, 779–791. 10.1165/rcmb.2015-0388OC (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gan, Y., Ye, F. & He, X. X. The role of YWHAZ in cancer: A maze of opportunities and challenges. J. Cancer11, 2252–2264. 10.7150/jca.41316 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Mei, J. et al. YWHAZ interacts with DAAM1 to promote cell migration in breast cancer. Cell Death Discov.7, 221. 10.1038/s41420-021-00609-7 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Gong, Y., Wei, Z. & Liu, J. MiRNA-1225 inhibits osteosarcoma tumor growth and progression by targeting YWHAZ. Onco Targets Ther14, 15–27. 10.2147/OTT.S282485 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Guo, F. et al. miR-375-3p/YWHAZ/beta-catenin axis regulates migration, invasion, EMT in gastric cancer cells. Clin. Exp. Pharmacol. Physiol.46, 144–152. 10.1111/1440-1681.13047 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Xie, J. et al. ITGB1 drives hepatocellular carcinoma progression by modulating cell cycle process through PXN/YWHAZ/AKT Pathways. Front. Cell Dev. Biol.9, 711149. 10.3389/fcell.2021.711149 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wang, T. et al. Integrated bioinformatic analysis reveals YWHAB as a novel diagnostic biomarker for idiopathic pulmonary arterial hypertension. J. Cell Physiol.234, 6449–6462. 10.1002/jcp.27381 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Shi, J. et al. YWHAZ promotes ovarian cancer metastasis by modulating glycolysis. Oncol. Rep.41, 1101–1112. 10.3892/or.2018.6920 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Guo, F. et al. Anticancer effect of YWHAZ silencing via inducing apoptosis and autophagy in gastric cancer cells. Neoplasma65, 693–700. 10.4149/neo_2018_170922N603 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Cai, H. et al. Dihydroartemisinin attenuates hypoxia-induced pulmonary hypertension through the ELAVL2/miR-503/PI3K/AKT axis. J. Cardiovasc. Pharmacol.80, 95–109. 10.1097/FJC.0000000000001271 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Zuo, W. et al. Luteolin ameliorates experimental pulmonary arterial hypertension via suppressing hippo-YAP/PI3K/AKT signaling pathway. Front. Pharmacol.12, 663551. 10.3389/fphar.2021.663551 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kang, C. & Elledge, S. J. How autophagy both activates and inhibits cellular senescence. Autophagy12, 898–899. 10.1080/15548627.2015.1121361 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Yamamoto-Imoto, H. et al. Age-associated decline of MondoA drives cellular senescence through impaired autophagy and mitochondrial homeostasis. Cell Rep.38, 110444. 10.1016/j.celrep.2022.110444 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Evans, C. E., Cober, N. D., Dai, Z., Stewart, D. J. & Zhao, Y. Y. Endothelial cells in the pathogenesis of pulmonary arterial hypertension. Eur. Respir. J.10.1183/13993003.03957-2020 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Saliminejad, K., Khorram Khorshid, H. R., Soleymani Fard, S. & Ghaffari, S. H. An overview of microRNAs: Biology, functions, therapeutics, and analysis methods. J. Cell. Physiol.234, 5451–5465. 10.1002/jcp.27486 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Wang, Y. et al. Pulmonary arterial hypertension and microRNAs–an ever-growing partnership. Arch. Med. Res.44, 483–487. 10.1016/j.arcmed.2013.08.003 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Chun, H. J., Bonnet, S. & Chan, S. Y. Translational advances in the Field of pulmonary hypertension. Translating microRNA biology in pulmonary hypertension. It will take more Than “miR” Words. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med.195, 167–178. 10.1164/rccm.201604-0886PP (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Xing, X. Q. et al. MicroRNA-214-3p regulates hypoxia-mediated pulmonary artery smooth muscle cell proliferation and migration by targeting ARHGEF12. Med. Sci. Monit.25, 5738–5746. 10.12659/MSM.915709 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Gong, J. et al. Expression of miR-93-5p as a potential predictor of the severity of chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension. Biomed. Res. Int.2021, 6634417. 10.1155/2021/6634417 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Guo, L. et al. Differentially expressed plasma microRNAs and the potential regulatory function of Let-7b in chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension. PLoS One9, e101055. 10.1371/journal.pone.0101055 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Kanehisa, M., Furumichi, M., Sato, Y., Kawashima, M. & Ishiguro-Watanabe, M. KEGG for taxonomy-based analysis of pathways and genomes. Nucl. Acids Res.51, D587–D592. 10.1093/nar/gkac963 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Kanehisa, M. Toward understanding the origin and evolution of cellular organisms. Protein Sci.28, 1947–1951. 10.1002/pro.3715 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Kanehisa, M. & Goto, S. KEGG: Kyoto encyclopedia of genes and genomes. Nucl. Acids Res.28, 27–30. 10.1093/nar/28.1.27 (2000). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data used in this analysis are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.