Abstract

The development of a new catalytic asymmetric synthetic methodology has been following virtually the same pattern in the past decades. Herein, we present a latent synthon strategy within this well-established research domain. By employing substrates containing latent groups, specifically “ON-alkene” in this investigation, a single optimization exercise yields the Diels–Alder adduct with excellent enantiomeric purity. This adduct serves as a universal intermediate, undergoing late-stage diversifications via robust and easily performed synthetic transformations. Consequently, a broad array of structurally diverse chiral norbornanes (NBAs) and norbornenes (NBEs) are obtained with consistent and high enantiomeric purities. Furthermore, our methodology allows for facile asymmetric preparation of chiral NBE ligands as well as the concise synthesis of (+)-gemmacin, ( + )-gemmacin B, and their structural analogs.

Subject terms: Synthetic chemistry methodology, Asymmetric catalysis, Synthetic chemistry methodology

The development of a new catalytic asymmetric synthetic methodology is of topic of interest. Herein, the authors report a latent synthon strategy, which has been used in the synthesis of a wide range of optically enriched norbornanes with great structural diversity.

Introduction

The development of catalytic asymmetric synthetic methodology in organic chemistry is a highly important yet very matured area, which essentially follows the same pattern that has been commonly practiced for years. As illustrated in Fig. 1a, representative substrates (S1-1, S2-1) are selected for a model reaction, which is treated with different catalysts/catalytic systems under various reaction conditions. Through numerous rounds of screenings and reaction optimizations, many of those efforts are in fact not even documented in the eventual publication, optimal conditions are found to deliver product P1 in high yield with excellent stereoselectivity. The subsequent reaction scope study is crucial, as any good reaction needs to be applicable to a broad range of substrates. In the reaction scope survey, substrates (S1, S2) containing different structural subunits are subjected to the optimized conditions that have been established in the model reaction, i.e. those optimal for S1-1 and S2-1, to realize diversification and form different products (P2–P5). There are some key drawbacks in the above conventional methodology development: 1) the substrates often need to be prepared, in an appealing table containing a broad range of substrates, tremendous efforts for substrate synthesis may be hidden and only described in the supporting information. 2) carrying out reactions using optimized conditions obtained through the model reaction for substrates bearing different structural subunits inevitably leads to inconsistent results: the yields and stereoselectivities often fluctuate, and can be substantial at times. In a conceptually novel manner, we propose the latent synthon1,2 strategy as a new paradigm for the development of synthetic methodologies in asymmetric catalysis (Fig. 1b). The key is to design and utilize substrates bearing the latent groups (a, b, d in S1/S2 structures) enabling late-stage functionalization and structural diversification. When one or more universal substrates bearing the latent groups are employed, only one optimization exercise is needed; the catalytic effects of different catalysts under a variety of reaction conditions are to be evaluated to identify the optimal conditions so that the products with latent groups can be obtained in high yields with excellent stereoselectivities. Thereafter, traditional tedious reaction scope study becomes late-stage functionalization of a common intermediate bearing easily functionalized groups, and scope survey essentially is the stepwise molecular assembly using a common chiral backbone through robust chemical transformations. Notably, upon obtaining optically enriched products bearing the latent groups, different chiral products with the same enantiopurity can be readily accessed through late-stage functionalization steps, provided these steps do not affect stereochemical integrity arrived earlier (steps 1–3 in Fig. 1b).

Fig. 1. Background.

a Conventional methodology development: an illustration. b Our proposal: the latent synthon strategy. Cat., catalyst.

We believe the latent synthon strategy is of conceptual significance, holding tremendous potential in organic chemistry. In our proof-of-concept study, we aim to validate this concept and demonstrate its power and practical values in asymmetric catalysis and synthesis. Alkenes play a crucial role in organic synthesis due to their availability, reactivity, and versatility, and the development of alkene-based synthetic methodologies forms the cornerstone of modern organic chemistry. Given the importance of alkenyl substrates as valuable building blocks in synthetic organic chemistry, and also due to the ubiquitous presence of alkene functionality in organic compounds, we decided to incorporate a C = C double bond into the design of a latent synthon. For the selection of the latent groups, we bear in mind the following criteria: 1) sufficient stability, to survive a broad range of reaction conditions; 2) readiness to undergo facile transformation to yield different substructures, e.g. introducing aryl/alkyl moieties; 3) robust chemistry for the late-stage functionalization, no racemization thus well-retained stereochemical information. Intriguingly, the electronic nature of the latent groups and the eventual substructure, i.e. aryl/alkyl substituents in the products are expected to be substantially different. From a synthetic planning viewpoint, such differences in electronic properties may render the latent synthon strategy a departure from a conventional retrosynthetic analysis (vide infra). In what follows, we describe our design of a disubstituted alkene as the latent synthon, for the enantioselective synthesis of diverse multi-substituted norbornanes (NBAs), en route to the synthesis of norbornene (NBE)-type ligands, as well as facile preparation of (+)-gemmacin, ( + )-gemmacin B, and their analogs.

Chiral NBEs and NBAs are substructures that are widely present in drug molecules, biologically active agents, and ligands in asymmetric catalysis (Fig. 2a). Biperiden3, a medication to treat Parkinson’s disease, antibacterial agents gemmacin and gemmacin B4, and aurora-kinase inhibitor cenisertib (AS-703569)5 all contain a core NBA/NBE unit or its derivative. In transition metal catalysis, NBE and its structural derivatives have been shown to be very powerful ligands in mediating various reactions, including the Catellani reaction, and C–H functionalization/activation, among others6–19. In their recent studies, Zhou and co-workers disclosed asymmetric construction of C–C20–23 and C–N24 axially chiral molecules via palladium/chiral NBE cooperative catalysis. To the best of our knowledge, the current methods for the preparation of chiral NBAs/NBEs rely on chiral resolution or utilization of stoichiometric chiral reagent to synthesize specific NBEs with high enantiopurity16,17, a general catalytic method that allows for asymmetric access to structurally diverse chiral NBAs/NBEs remains elusive. It was with this observation that we became interested in finding a practical solution to this challenging problem. Through the introduction of the latent synthon strategy, we wish to showcase its power and potential in asymmetric catalysis and synthesis.

Fig. 2. The latent synthon strategy for asymmetric Diels–Alder reaction, a straightforward and unifying synthesis of chiral norbornanes and norbornenes.

a Chiral norbornanes (NBAs)/norbornenes (NBEs). b Synthesis of NBEs via Diels–Alder reaction. c Diels–Alder synthesis of NBEs using the latent synthon strategy. d Facile synthesis of the key alkene latent synthon, ON-alkene. THF, tetrahydrofuran; aq., aqueous solution; NHPI, N-hydroxyphthalimide; DIC, N,N’-diisopropylcarbodiimide; DMAP, 4-dimethylaminopyridine.

To construct the bridged backbone of NBAs/NBEs, a Diels–Alder reaction is an obvious choice. In the past few decades, there have been numerous reports describing the Diels–Alder reaction between cyclopentadiene and oxazolidinone-type dienophiles for the enantioselective synthesis of substituted NBEs25–31. However, those studies were rather focused on the development of chiral Lewis acids/chiral ligands, and only very limited NBE scaffolds were accessed with a certain degree of success in enantiomeric control. We envisioned that an enantioselective Diels–Alder reaction between cyclopentadiene and a carefully designed dienophile, a latent synthon in this case, may provide a general method for the preparation of structurally diverse chiral NBAs/NBEs. To synthesize disubstituted NBEs bearing different substitution groups (Fig. 2b, I-III), a direct retrosynthetic analysis yields simple alkene starting materials (i-iii). However, the corresponding Diels–Alder reactions are not possible, as cyclopentadiene and the alkene substrates are electronically not matched. We wish, through the design and engagement of latent functional groups (LFGs), that the above retrosynthetic analysis may be seen as feasible at the reaction planning stage. In a projected enantioselective synthesis of NBEs via an asymmetric Diels–Alder reaction utilizing cyclopentadiene as a reaction partner, the alkenyl dienophile needs to be electron-poor. To design a specific alkene latent synthon suitable for derivatizing NBEs, we envisaged installing two LFGs at both ends of a C=C double bond, which ideally would be electron-withdrawing in nature and can be readily converted to different groups through robust chemical transformations (Fig. 2c).

The past decade has witnessed widespread applications of N-hydroxyphthalimide (NHP) based redox-active esters in synthetic organic chemistry32–34. Following single electron transfer (SET) reduction, fragmentation of the NHP ester leads to the generation of a radical species, which participates in a variety of transformations under mild conditions, including arylation35,36, alkylation37, decarboxylation and Giese-type addition38, borylation39, and iodination40, among others. In addition to their synthetic versatility, the NHP esters are inexpensive and stable, readily accessible from commonly available carboxylic acids, we thus decided to use the NHP ester as one of the LFGs. To the best of our knowledge, NHP esters have not been employed in the Diels–Alder reaction previously. It should be noted that the incorporation of an NHP ester moiety into the structure of a substrate is unknown, thus its stability towards multi-step synthetic manipulations remains to be seen. Furthermore, the presence of the NHP ester moiety is also an unknown factor in effective enantiomeric control. When it comes to the selection of another LFG in our designated alkene substrate, we turned our attention to N-acyloxazolidinone structure, which was present in a range of dienophile structures in the Diels–Alder reaction with cyclopentadiene. The electron-withdrawing nature of the N-acyloxazolidinone is ideal, and the presence of two carbonyl groups provides sites for metal coordination thus for the potential enantiomeric control. Our aim is to design one single, simple substrate, an alkenyl latent synthon, which can be subjected to the Diels–Alder reaction with cyclopentadiene. Subsequently, upon obtaining the common enantiomerically enriched product under optimal conditions, a broad range of products may be derived in a stepwise fashion using robust and easily performed synthetic protocols. Ideally, the alkenyl latent synthon needs to be readily accessible through trivial chemical transformations, produced in large quantities from common, cheap starting materials. With the above thinking in mind, we developed a facile synthesis of an alkenyl latent synthon. The synthesis is straightforward; simply mixing two inexpensive starting materials, 2-oxazolidinone and maleic anhydride, followed by a coupling reaction with NHPI, yielding an alkenyl latent synthon, which we name “ON-alkene” (O: oxazolidinone, N: NHP). It is noteworthy that ON-alkene is easily purified by simple recrystallization, and it is a bench-stable compound, readily attainable at decagram-scale (Fig. 2d).

Results and discussion

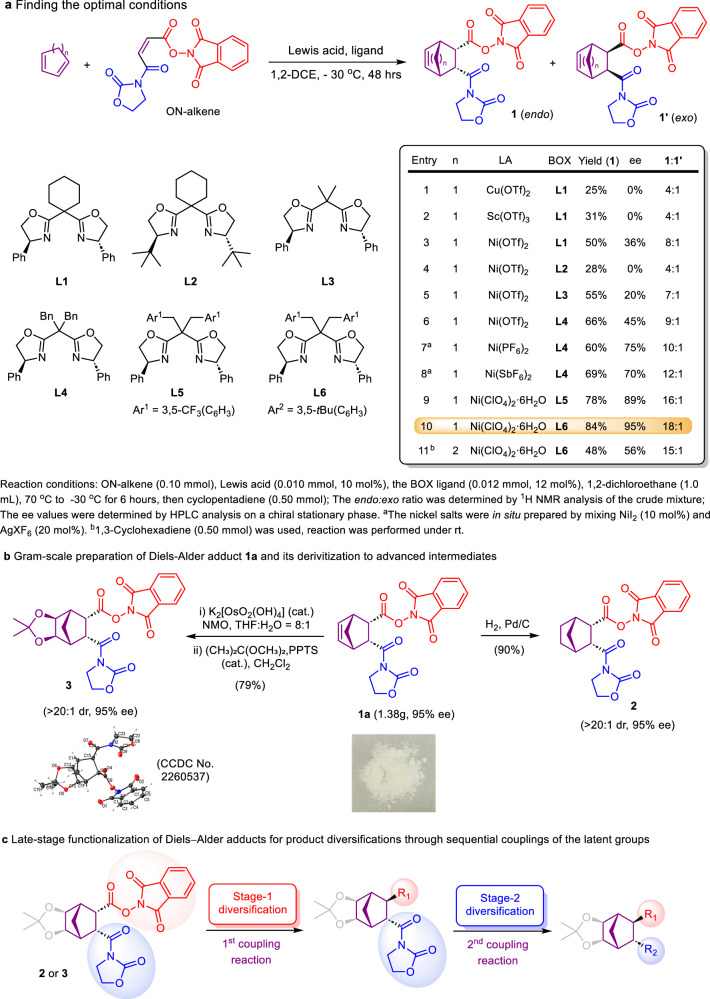

We started our investigation by finding out the optimal conditions for the Diels–Alder reaction between cyclopentadiene and ON-alkene (Fig. 3a). Different Lewis acids, as well as a number of chiral bisoxazoline (Box) ligands, were examined. Although Cu(OTf)2 and Sc(OTf)3 were widely used as Lewis acid catalysts for Diels–Alder reactions in the previous reports, they were found to be totally ineffective for our reaction (entries 1 and 2, Tables S1 and S2 in SI), despite employing a broad range of chiral ligands (see the SI for details). Similarly, Yb(OTf)3 was also ineffective. To our delight, Ni(OTf)2 appeared to be promising (entry 3). Subsequently, the effects of combining different nickel complexes and Box ligands on promoting the reaction were evaluated (entries 4–9, Tables S3 and S4 in SI). It is noteworthy that the phenyl substituent in the Box structure is crucial for asymmetric induction, and other substituents were less effective. Moreover, the counterions in the nickel complexes dramatically influenced the reaction. Lastly, the influences of different solvents, as well as temperatures on the reaction were evaluated (Table S5 in SI). Under the optimal reaction conditions, the employment of Ni(ClO4)2·6H2O and L6 led to the formation of endo-adduct 1a in 84% yield with 95% ee (entry 10). When 1,3-cyclohexadiene was employed, the corresponding Diels–Alder adduct bicyclo[2.2.2]octene-type 1b was formed in moderate yield and ee value (entry 11). Due to the low reactivity of 1,3-cyclohexadiene41, the reaction had to be performed at room temperature instead of −30 °C. It is noteworthy the synthesis of 1a is easily scalable; in a gram-scale synthesis, adduct 1a was obtained in 75% yield, with the same enantio- and endo-selectivities, although a longer reaction time was required. Towards eventual late-stage functionalization to access various chiral NBEs and NBAs, compound 1a was further converted to two advanced intermediates (Fig. 3b). Simple hydrogenation led to the formation of NBA 2, the structural elaborations of which are anticipated to yield different chiral NBAs. The double bond in the NBE structure may lead to potential radical norbornenyl-nortricyclyl equilibrium42,43, which was thus protected to furnish NBA 3, serving as a masked NBE and a common intermediate for the preparation of various optically enriched NBEs. The absolute configuration of Diels–Alder adduct 1a was determined on the basis of X-ray crystallographic analysis of compound 3 (CCDC No. 2260537). In projected syntheses of enantiomerically enriched NBEs and NBAs, advanced common intermediates 2 and 3 will be subjected to the coupling reactions at the NHP ester site, to realize stage-1 diversification. The structural manipulations of the N-acyloxazolidinone moiety then induce stage-2 functionalization, completing structural diversification and adding complexity to the eventual NBEs and NBAs (Fig. 3c). We bear in mind the diversification/functionalization steps should be racemization free, without compromising the stereochemical integrity of the advanced intermediates so that the excellent enantioselectivity attained through initial optimization will be carried forward to the eventual chiral NBE/NBA products.

Fig. 3. Reaction development.

a Optimizing the reaction conditions. b Gram-scale preparation of Diels–Alder adduct 1 and its derivatization to advanced intermediates for further diversifications. c Late-stage diversifications of Diels–Alder products through sequential couplings of the latent groups. 1,2-DCE, 1,2-dichloroethane; BOX, bisoxazoline; Ph, phenyl; tBu, tert-butyl; NMO, N-methylmorpholine N-oxide; THF, tetrahydrofuran; PPTS, pyridinium p-toluenesulfonate.

We first carried out the stage-1 diversification reactions, through functionalization of the NHP ester moiety in 2 or 3 (Fig. 4). With the employment of aryl zinc reagents, nickel-catalyzed decarboxylative aryl–alkyl cross-coupling reactions33 proceeded smoothly, leading to the formation of NBAs 4 (4a, 4b) or 5 (5a–5d) containing an aryl or a hetero-aryl substituent. The C(sp3)–C(sp3) radical cross-coupling reactions37 also took place readily through the reaction with dialkyl zinc reagent, and alkyl-substituted NBAs (5e & 5f) were obtained in good yields with excellent stereoselectivities. Moreover, under the catalysis of Ni(ClO4)2·6H2O, and using zinc powder as a reductant, the radical species derived from 3 underwent the Giese reaction38 to effectively add to several radical acceptors, e.g., acrylate (5g), vinyl sulfone (5h), and acrylamide (5i), forming the corresponding addition products in good yields. Notably, arylation product 5j, a key intermediate for the synthesis of gemmacin and gemmacin B (vide infra) was easily prepared as a single diastereomer with 95% ee. When an allyl sulfone was employed, a formal allylation reaction44 occurred through the release of the sulfonyl radical, resulting in the formation of NBA 5k bearing an allyl group. Through triphenylphosphine-catalyzed iodination using lithium iodide under visible light irradiation45, the corresponding chiral NBA iodide (5l) was obtained in good yield. We observed that utilizing sodium iodide instead of lithium iodide and running the reaction at a higher temperature (45 °C) led to more elimination products. Accordingly, the reaction mixture was treated with DBU to smoothly form NBE 5 m in good yield. In a similar fashion, NBE 4c was obtained in a good yield with excellent enantioselectivity. We next explored late-stage functionalization by employing natural product-bearing substrates, including (L)-menthol, (-)-borneol, and (+)-δ-tocopherol. Excellent functional group tolerance was observed, and the corresponding diastereomerically pure NBAs (5n–5p) were obtained. It is noteworthy that the stage-1 functionalization leads to the formation of functionalized products NBAs 4 or 5 in decent yields in all the above diversification reactions. Remarkably, almost all the reactions are diastereospecific, simple stage-1 functionalization yielded a single stereoisomer of functionalized NBA/NBE products, with ee values constantly at ~95%.

Fig. 4. The scope of reaction: stage-1 diversification of Diels–Alder products via decarboxylative coupling reactions.

Reaction conditions: either 2 or 3 (0.10 mmol) was used. aStandard conditions for arylation: Ni(glyme)Cl2 (20 mol%), dtbbpy (40 mol%), ArZnCl·LiCl (0.30 mmol), DMF (0.50 mL), THF (0.70 mL). bReaction performed at 50 °C. cStandard conditions for photo-induced iodination: LiI (0.20 mmol), PPh3 (10 mol%), acetone (1.0 mL), 30 W Blue LEDs irradiation. dNaI is used as the iodine source, then DBU (0.20 mmol). See General Procedures G–J in the Supplementary Information for detailed conditions. Yields refer to isolated yields. The dr ratios were determined by 1H NMR analysis of the crude mixture. The ee values were determined by HPLC analysis on a chiral stationary phase. tBu, tert-butyl; Bn, benzyl; Ph, phenyl.

Enantiomerically enriched NBAs bearing two adjacent unactivated groups are structural motifs that are easily conceived synthetically via a Diels–Alder reaction but practically inaccessible, they are however readily prepared through our latent synthon strategy. The advanced chiral NBA products 4 or 5 were subjected to second-stage functionalization, and the results are summarized in Fig. 5. The latent N-acyloxazolidinone group was readily hydrolyzed, which were then converted to advanced NHP esters (6a–6e). Through photo-induced decarboxylative borylation reaction39, boronic esters (6f–6h) were obtained in high yields. The presence of the boronate moiety offers a convenient synthetic handle for further structural manipulations. For instance, chiral alcohol 6n was obtained as a single diastereomer in 96% yield. Triphenylphosphine-catalyzed decarboxylative iodination under visible light furnished iodides 6i–6k in excellent yields, and no elimination products were observed. Utilizing nickel-catalyzed Barton decarboxylation reaction38, NBAs 6l and 6m were smoothly prepared. Furthermore, through nickel-catalyzed cross-coupling reactions35, the corresponding arylation (6p–6r, 6t–6v) and allylation products (6o & 6s) were readily formed. Leveraging on the versatile boronate group, complex natural products or drug molecules can be incorporated to furnish late-stage functionalized NBA derivatives, including (S)-naproxen (6w), indomethacin (6x) and isoxepac (6y), and dehydrocholic acid (6z). Notably, all the trans-disubstituted chiral NBA adducts were readily synthesized in respectable yields (up to 95%), with high diastereoselectivities ( > 20:1 dr), and excellent enantioselectivities at ~95%. It should also be noted that the optically enriched NBA products synthesized herein have either aryl/alkyl substituents, or synthetically versatile boronate/halogen atoms at two adjacent sites, which were not obtained previously in a catalytic Diels–Alder reaction.

Fig. 5. The scope of reaction: stage-2 diversification of Diels–Alder products via decarboxylative coupling reactions.

Reaction conditions: 6a to 6e (0.050 mmol) (derived from 4 or 5) were used. aStandard conditions for photo-induced borylation: B2cat2 (0.15 mmol), DMAc (0.50 mL) under 30 W Blue LEDs irradiation, then pinacol (0.20 mmol) and Et3N (0.20 mL). bDerivatized from the corresponding boronates 6g, 6h. See General Procedures K–N in the Supplementary Information for detailed conditions. Yields refer to isolated yields. The dr ratios were determined by 1H NMR analysis of the crude mixture. The ee values were by HPLC analysis on a chiral stationary phase. NHPI, N-hydroxyphthalimide; DIC, N,N’-diisopropylcarbodiimide; DMAP, 4-dimethylaminopyridine.

The Catellani reaction is a palladium-catalyzed multi-component tandem reaction that makes use of aryl iodides, an electrophilic coupling reaction partner, and a terminating reagent, for the synthesis of multi-substituted arenes. In the Catellani reaction, NBEs play a critical role as a co-catalyst in the palladium catalytic cycle. Very recently, Zhou, Song, and co-workers reported atroposelective synthesis of C–C biaryl axially chiral molecules via palladium/chiral NBE cooperative catalysis20–23, whereby chiral NBEs were crucial in those processes. We thus developed facile catalytic synthetic protocols to access a range of structurally diverse chiral NBE ligands. By treating with sodium iodide at 45 °C under the blue LED irradiation, advanced intermediate 2 with two latent groups underwent a decarboxylative iodination to form iodide 7, mixed with NBE 4c. The former, upon reaction with DBU, was converted fully to eliminated product 4c. With the presence of latent amide group, 4c was readily transformed to a number of NBE ligands bearing different ester moieties (Fig. 6a). The application of chiral NBEs to the atroposelective synthesis through enantioselective Catellani reaction was quickly demonstrated; the C–C biaryl axially chiral molecules (14–16 & 19) were prepared in good yields with excellent enantioselectivities (Fig. 6b).

Fig. 6. Synthesis and applications of chiral NBE-type ligands.

a Facile synthesis of chiral NBE-ligands. b The applications of NBE-ligands in the construction of atropisomers. Ph, phenyl; iPr, isopropyl.

Gemmacin and gemmacin B are remarkable antibacterial agents, with activities against certain methicillin-resistant epidemic strains (EMRSA 15 and EMRSA 16) that are responsible for MRSA infections46,47, structure-activity relationship (SAR) studies on gemmacin and gemmacin B, and their structural analogs are thus of great importance. In fact, the versatile synthesis of molecules bearing a motif that is responsible for specific biological activities is of critical value in medicinal chemistry, we next applied our Diels–Alder adduct 3 bearing two LFGs to the total synthesis of gemmacin and gemmacin B, as well their structural analogs48. Through nickel-catalyzed decarboxylative aryl–alkyl cross-coupling, diastereomerically pure NBA 5j bearing the key thiol-arene moiety was obtained with 95% ee. The oxazolidinone was converted to a methyl ester, forming NBA 20 in high yield. The diol moiety was then oxidatively cleaved, and subsequent reductive amination and ester hydrolysis completed the total synthesis of gemmacin and gemmacin B (Fig. 7a). Synthesis of structural analogs of gemmacin and gemmacin B is straightforward; we could simply do so by carrying out the 1-diversification reaction with different diaryl zinc reagents, and treating the advanced dialdehyde intermediates with different amines. As an illustration, gemmacin analogs (27–31) were prepared in decent overall yields and with high stereochemical selectivities (Fig. 7b). Notably, the above synthesis of gemmacin, gemmacin B and their structural analogs all started from a common intermediate, and the enantiomerically enriched products were easily obtained through robust chemistry and the stereochemical information established in the initial single reaction optimization practice was well maintained in the subsequent steps and passed on to the final drug-like molecules.

Fig. 7. Applications to total synthesis of natural products and their structural analogs.

a Asymmetric synthesis of (+)-gemmacin and (+)-gemmacin B. b Preparation of close structural analogs of (+)-gemmacin and (+)-gemmacin B. dtbbpy, 4,4’-di-tert-butyl-2,2’-dipyridyl; DMF, N,N-dimethylformamide; THF, tetrahydrofuran; TsOH, p-toluenesulfonic acid; TFA, trifluoroacetic acid; 1,2-DCE, 1,2-dichloroethane.

In conclusion, we have introduced the latent synthon strategy as a new paradigm in asymmetric catalysis and synthesis. Through the design of common synthon(s) bearing the latent groups, traditional methodology development may become one optimization exercise involving universal substrate(s), followed by the utilization of robust, well-established chemistry for structural diversification for the subsequent substrate scope survey. In our proof of concept study, we designed an alkene synthon, ON-alkene, bearing a latent NHP ester and an oxazolidinone moieties, and showed its unique value in the Diels–Alder reaction. Specifically, through the employment of ON-alkene as a universal alkene substrate, stereoselective Diels–Alder reaction with cyclopentadiene formed the NBE adduct in high yield, excellent endo- and enantioselectivity. Through robust chemistry, the stereochemical information obtained in the initial optimization studies was carried forward to form a wide range of optically enriched NBAs of great structural diversity. Notably, the synthesis of chiral NBAs described is unconceivable through a known Diels–Alder reaction, and the approach reported herein represents a departure from conventional retrosynthetic analysis. Furthermore, the practical values of the chiral NBAs and NBEs obtained in this study were demonstrated in the synthesis of chiral NBE ligands and related applications in atroposelective synthesis of axially chiral molecules, as well as in the total synthesis of gemmacin, gemmacin B, and their structural analogs. With the introduction of the latent synthon strategy, we anticipate the design and development of new latent group-bearing molecules to be forthcoming, which may provide a partial solution to the tedious and inefficient scope survey in asymmetric catalysis, providing a fresh perspective on methodology development in organic synthesis.

Methods

A typical procedure for the preparation of dienophile reagent

The alkene latent synthon (ON-Alkene) was synthesized according to the procedure below: A round-bottom-flask was charged with maleic anhydride (100 mmol, 1.0 equiv.), 2-oxazolindinone (100 mmol, 1.0 equiv), LiCl (5 mmol, 5 mol%) and THF (300 mL). The reaction mixture was cooled to 0 °C, then triethylamine (110 mmol, 1.1 equiv.) was added slowly to the system. After 5 h (Note: Prolonged reaction time may cause the partial Z-E isomerization!), the solution was acidified with 3 N HCl until pH <2. The mixture solution was washed with water, extracted with EtOAc, dried over Na2SO4, and concentrated directly to give the acid intermediate without further purification. The crude solid was dissolved in CH2Cl2, and NHPI (100 mmol, 1.0 equiv.), DMAP (10.0 mmol, 10 mol%) was added to the solution. The reaction mixture was cooled to 0 °C, and then DIC (105 mmol, 1.05 equiv.) was added slowly to the system. After the acid was fully consumed (monitored by TLC), the reaction mixture was directly concentrated to give an orange-colored crude solid mixture. The crude product was washed with cold EtOAc to remove most of the byproducts. After that, the washed solid was dissolved in excess CH2Cl2, filtered, and the filtrate was washed with a small amount of water. The filtrate was then dried over Na2SO4, and concentrated to give the purified dienophile ON-Alkene (24.0 g, 73%) without further purification. In most cases, ON-Alkene obtained by this procedure can be directly used in Diels–Alder reaction. If desired, it can be further purified by silica gel column chromatography (pure CH2Cl2) to afford pure ON-Alkene as an off-white crystalline.

A typical procedure for Ni-catalyzed Diels–Alder reaction

A Schlenk-tube was charged with dienophile reagent ON-Alkene (0.10 mmol, 1.0 equiv.), Ni(ClO4)2·6H2O (0.010 mmol, 10 mol%) and L6 (0.012 mmol, 12 mol%). The solid mixture was dissolved in 1,2-dichloroethane (1.0 mL) and then heated to 70 °C under Ar atmosphere. After 6–10 h, the mixture became a yellow-green solution without undissolved Ni(ClO4)2·6H2O. Then the solution was cooled to −30 °C, and freshly distilled cyclopentadiene (0.50 mmol, 5.0 equiv.) was added slowly to the system. After 48 h, the reaction mixture became a clear yellow solution without undissolved ON-Alkene, which indicated the full consumption of dienophile. After that, the mixture was concentrated directly and then purified by silica gel column chromatography (Hexane:EtOAc = 1:1) to afford the endo-cycloadduct 1.

Supplementary information

Acknowledgements

Y.L. thanks the National University of Singapore (A-8001466-00-00), and the Ministry of Education (MOE) of Singapore (A-0008481-00-00) for generous financial support.

Author contributions

Z.-A.S. and Y.L. conceived the work, developed the conditions, and designed the experiments. Z.-A.S. and J.G. performed most of the investigations, substrate design, and syntheses. Z.-A.S., J.G., and Y.L. analyzed the results and wrote the manuscript together. Y.L. administered the whole project.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Sandip Murarka and Thierry Ollevier for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Data availability

The authors declare that all data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article and its supplementary information files. The X-ray crystallographic coordinates for structures reported in this study have been deposited at the Cambridge Crystallographic Data Center (CCDC), under deposition number 2260537 (3). These data can be obtained free of charge from The Cambridge Crystallographic Data Center via www.ccdc.cam.ac.uk/data_request/cif. All data are available from the corresponding author upon request.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

These authors contributed equally: Zi-An Shen, Jiami Guo.

Supplementary information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41467-024-52644-4.

References

- 1.Gomez, A. M., Cristobal Lopez, J. & Fraser-Reid, B. Serial radical cyclization of pyranose-derived dienes in the stereocontrolled synthesis of woodward’s reserpine precursor. J. Org. Chem.60, 3859–3870 (1995). [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chang, J. W. et al. In vivo imaging of the tumor-associated enzyme NCEH1 with a covalent PET probe. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed.59, 15161–15165 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Richardson, C., Kelly, D. L. & Conley, R. R. Biperiden for excessive sweating from clozapine. Am. J. Psychiatry158, 1329–1330 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Robinson, A., Thomas, G. L., Spandl, R. J., Welch, M. & Spring, D. R. Gemmacin B: bringing diversity back into focus. Org. Biomol. Chem.6, 2978–2981 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cheung, C. H. A., Sarvagalla, S., Lee, J. Y.-C., Huang, Y.-C. & Coumar, M. S. Aurora kinase inhibitor patents and agents in clinical testing: an update (2011 – 2013). Expert. Opin. Ther. Pat.24, 1021–1038 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Narsireddy, M. & Yamamoto, Y. Catalytic asymmetric intramolecular hydroamination of alkynes in the presence of a catalyst system consisting of Pd(0)-methyl norphos (or tolyl renorphos)-benzoic acid. J. Org. Chem.73, 9698–9709 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Catellani, M., Frignani, F. & Rangoni, A. A complex catalytic cycle leading to a regioselective synthesis of o,o′-disubstituted vinylarenes. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed.36, 119–122 (1997). [Google Scholar]

- 8.Maestri, G. et al. Of the ortho effect in palladium/norbornene-catalyzed reactions: a theoretical investigation. J. Am. Chem. Soc.133, 8574–8585 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dong, Z., Wang, J. & Dong, G. Simple amine-directed meta-selective C–H arylation via Pd/norbornene catalysis. J. Am. Chem. Soc.137, 5887–5890 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dong, Z., Wang, J., Ren, Z. & Dong, G. Ortho C-H acylation of aryl iodides by palladium/norbornene catalysis. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed.54, 12664–12668 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Huang, Y., Zhu, R., Zhao, K. & Gu, Z. Palladium-catalyzed catellani ortho-acylation reaction: an efficient and regiospecific synthesis of diaryl ketones. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed.54, 12669–12672 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shen, P.-X., Wang, X.-C., Wang, P., Zhu, R.-Y. & Yu, J.-Q. Ligand-enabled meta-C–H alkylation and arylation using a modified norbornene. J. Am. Chem. Soc.137, 11574–11577 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wang, X.-C. et al. Ligand-enabled meta-C–H activation using a transient mediator. Nature519, 334–338 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ye, J. & Lautens, M. Palladium-catalysed norbornene-mediated C–H functionalization of arenes. Nat. Chem.7, 863–870 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cheng, H.-G. et al. Epoxides as alkylating reagents for the catellani reaction. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed.57, 3444–3448 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Li, R., Liu, F. & Dong, G. Palladium-catalyzed asymmetric annulation between aryl iodides and racemic epoxides using a chiral norbornene cocatalyst. Org. Chem. Front.5, 3108–3112 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shi, H., Herron, A. N., Shao, Y., Shao, Q. & Yu, J.-Q. Enantioselective remote meta-C–H arylation and alkylation via a chiral transient mediator. Nature558, 581–585 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wang, J., Li, R., Dong, Z., Liu, P. & Dong, G. Complementary site-selectivity in arene functionalization enabled by overcoming the ortho constraint in palladium/norbornene catalysis. Nat. Chem.10, 866–872 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bai, M. et al. A modular approach for diversity-oriented synthesis of 1,3-trans-disubstituted tetrahydroisoquinolines: seven-step asymmetric synthesis of michellamines B and C. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed.61, e202205245 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Liu, Z.-S. et al. Construction of axial chirality via palladium/chiral norbornene cooperative catalysis. Nat. Catal.3, 727–733 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 21.Feng, Q. et al. Catalytic atroposelective catellani reaction enables construction of axially chiral biaryl monophosphine oxides. CCS Chem.3, 377–387 (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 22.Liu, Z.-S. et al. Construction of axially chiral biaryls via atroposelective ortho-C–H ARylation of Aryl Iodides. ACS Catal.13, 2968–2980 (2023). [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ye, J. et al. Enantioselective assembly of ferrocenes with axial and planar chiralities via palladium/chiral norbornene cooperative catalysis. JACS Au3, 384–390 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Liu, Z.-S. et al. An axial-to-axial chirality transfer strategy for atroposelective construction of C–N axial chirality. Chem7, 1917–1932 (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 25.Evans, D. A., Chapman, K. T. & Bisaha, J. Asymmetric Diels-Alder cycloaddition reactions with chiral.alpha.,.beta.-unsaturated N-acyloxazolidinones. J. Am. Chem. Soc.110, 1238–1256 (1988). [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jaquith, J. B., Levy, C. J., Bondar, G. V., Wang, S. & Collins, S. Diels−Alder reactions of oxazolidinone dienophiles catalyzed by zirconocene bis(triflate) catalysts: mechanism for asymmetric induction. Organometallics17, 914–925 (1998). [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kanemasa, S. et al. Transition-metal aqua complexes of 4,6-dibenzofurandiyl-2,2‘-bis(4-phenyloxazoline). Effective catalysis in Diels−Alder reactions showing excellent enantioselectivity, extreme chiral amplification, and high tolerance to water, alcohols, amines, and acids. J. Am. Chem. Soc.120, 3074–3088 (1998). [Google Scholar]

- 28.Evans, D. A. et al. Bis(oxazoline) and bis(oxazolinyl)pyridine copper complexes as enantioselective Diels-Alder catalysts:reaction scope and synthetic applications. J. Am. Chem. Soc.121, 7582–7594 (1999). [Google Scholar]

- 29.Evans, D. A., Miller, S. J., Lectka, T. & von Matt, P. Chiral bis(oxazoline)copper(II) complexes as Lewis acid catalysts for the enantioselective Diels-Alder reaction. J. Am. Chem. Soc.121, 7559–7573 (1999). [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ghosh, A. K. & Matsuda, H. Counterions of BINAP-Pt(II) and -Pd(II) complexes: novel catalysts for highly enantioselective Diels-Alder reaction. Org. Lett.1, 2157–2159 (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bolm, C., Martin, M., Simic, O. & Verrucci, M. C2-symmetric bissulfoximines as ligands in copper-catalyzed enantioselective Diels-Alder reactions. Org. Lett.5, 427–429 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Parida, S. K. et al. Single electron transfer-induced redox processes involving N-(Acyloxy)phthalimides. ACS Catal.11, 1640–1683 (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chen, T. G. et al. Building C(sp3)-rich complexity by combining cycloaddition and C-C cross-coupling reactions. Nature560, 350–354 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Murarka, S. N-(Acyloxy)phthalimides as redox-active esters in cross-coupling reactions. Adv. Synth. Catal.360, 1735–1753 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cornella, J. et al. Practical Ni-catalyzed aryl-alkyl cross-coupling of secondary redox-active esters. J. Am. Chem. Soc.138, 2174–2177 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Huihui, K. M. M. et al. Decarboxylative cross-electrophile coupling of N-hydroxyphthalimide esters with aryl iodides. J. Am. Chem. Soc.138, 5016–5019 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Qin, T. et al. A general alkyl-alkyl cross-coupling enabled by redox-active esters and alkylzinc reagents. Science352, 801–805 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Qin, T. et al. Nickel-catalyzed barton decarboxylation and giese reactions: a practical take on classic transforms. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed.56, 260–265 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Fawcett, A. et al. Photoinduced decarboxylative borylation of carboxylic acids. Science357, 283–286 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Fu, M.-C., Wang, J.-X. & Shang, R. Triphenylphosphine-catalyzed alkylative iododecarboxylation with lithium iodide under visible light. Org. Lett.22, 8572–8577 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Levandowski, B. J. & Houk, K. N. Theoretical analysis of reactivity patterns in Diels–Alder reactions of cyclopentadiene, cyclohexadiene, and cycloheptadiene with symmetrical and unsymmetrical dienophiles. J. Org. Chem.80, 3530–3537 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Warner, C. R., Strunk, R. J. & Kuivila, H. G. The norbornenyl-nortricyclyl radical system. J. Org. Chem.31, 3381–3384 (1966). [Google Scholar]

- 43.Chowdhury, R. et al. Decarboxylative alkyl coupling promoted by NADH and blue light. J. Am. Chem. Soc.142, 20143–20151 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sumino, S., Uno, M., Huang, H.-J., Wu, Y.-K. & Ryu, I. Palladium/light induced radical alkenylation and allylation of alkyl iodides using alkenyl and allylic sulfones. Org. Lett.20, 1078–1081 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Fu, M.-C., Shang, R., Zhao, B., Wang, B. & Fu, Y. Photocatalytic decarboxylative alkylations mediated by triphenylphosphine and sodium iodide. Science363, 1429–1434 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Moore, P. C. L. & Lindsay, J. A. Molecular characterisation of the dominant UK methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus strains, EMRSA-15 and EMRSA-16. J. Med. Microbiol.51, 516–521 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wolter Daniel, J., Chatterjee, A., Varman, M. & Goering Richard, V. Isolation and Characterization of an epidemic methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus 15 variant in the central United States. J. Clin. Microbiol.46, 3548–3549 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Thomas, G. L. et al. Anti-MRSA agent discovery using diversity-oriented synthesis. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed.47, 2808–2812 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The authors declare that all data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article and its supplementary information files. The X-ray crystallographic coordinates for structures reported in this study have been deposited at the Cambridge Crystallographic Data Center (CCDC), under deposition number 2260537 (3). These data can be obtained free of charge from The Cambridge Crystallographic Data Center via www.ccdc.cam.ac.uk/data_request/cif. All data are available from the corresponding author upon request.