Abstract

Background:

The syndemic of HIV, substance use (SU), and mental illness has serious implications for HIV disease progression among women. We described co-utilization of HIV care, SU treatment, and mental health treatment among women with or at risk for HIV.

Methods:

We included data from women with or at risk for HIV (n = 2559) enrolled in all 10 sites of the Women’s Interagency HIV Study (WIHS) from 2013 to 2020. Current SU was defined as self-reported, non-medical use of drugs in the past year, excluding use of only marijuana. Tobacco and alcohol were assessed separately. We described co-utilization of SU treatment, tobacco and alcohol use treatment, HIV care, and mental health care in the past year among women who were eligible for each service. We compared service utilization by those who did/did not utilize SU treatment using Wald Chi-square tests.

Results:

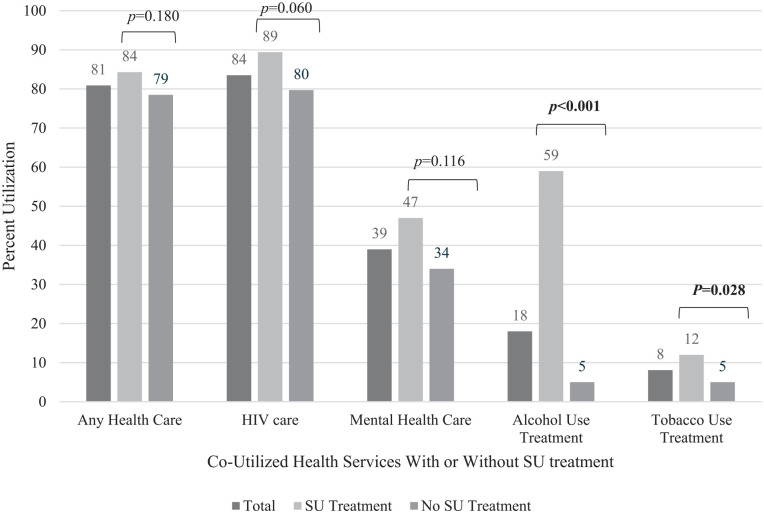

Among women with current SU (n = 358), 42% reported utilizing SU treatment. Among those with current SU+HIV (n = 224), 84% saw their HIV provider, and 34% saw a mental health provider. Among women with current SU+heavy alcohol use (n = 95), 18% utilized alcohol use treatment; among current SU+tobacco use (n = 276), 8% utilized tobacco use treatment. Women who utilized SU treatment had higher utilization of alcohol use treatment (59% vs. 5%; P < .001) and tobacco use treatment (12% vs. 5%; P = .028). HIV care engagement was high regardless of SU treatment.

Conclusions:

We found high engagement in SU and HIV care, but low engagement in alcohol and tobacco use treatment. Integrated SU treatment services for women, including tobacco/alcohol treatment and harm reduction, are needed to optimize treatment engagement and HIV care continuum outcomes.

Keywords: HIV, women, substance use

Introduction

Substance use disorder is common among women with HIV 1 and associated with adverse health outcomes. People living with HIV who use substances have faster progression of their HIV, lower adherence to antiretrovirals, 2 and reduced viral suppression. 3 In the US, 1 in 3 women with HIV are diagnosed with substance use disorders, and women who inject drugs are more vulnerable than men to drug-related harms, such as acquisition of HIV, bacterial infections, and sexually transmitted infections.4 -6 Despite evidence-based treatments for substance use disorders,7,8 there is an implementation gap in substance use (SU) treatment uptake. 9 Although reasons for this are not well understood, women face unique barriers to accessing SU treatment, including intersectional stigma and discrimination, fear of intimate partner violence if treatment is sought, childcare responsibilities, and fear of loss of custody.10 -13 Together, these may contribute to gender disparities in seeking, accessing, and remaining engaged in SU care or harm reduction services.

Integrated care delivery is a way to potentially improve treatment access and utilization by linking SU care to other services that women trust and may be a strategy to improve both HIV and SU outcomes for women. Several models of integrated care delivery have been demonstrated in HIV and SU care settings, such as co-location of services, 14 low-barrier or “bridge” clinics,15,16 mobile health services, 17 and integration with harm reduction services. 18 Low barrier HIV care models (eg Seattle’s Max Clinic, San Francisco’s POP-UP clinic) have been implemented and studied for individuals with housing instability, substance use disorders, or other barriers to care, and have been shown to improve rates of viral suppression.15,16 Offering HIV treatment via telehealth at a syringe services program for people who inject drugs also found high rates of viral suppression. 18 Studies of mobile health units to deliver integrated HIV and opioid use disorder care are underway, 19 however outcomes data are currently limited. Integrated HIV/substance use care for women is less well-described, but addressing co-occurring problems could reduce barriers to accessing care, mitigate drug-related harms, and improve health outcomes among women with HIV and SU.14,20,21

Contemporary data on healthcare utilization among women with HIV and SU are needed to inform implementation strategies and optimal models of integrated care. We previously found that women enrolled in the Women’s Interagency HIV Study (WIHS) with current SU had higher-than-expected utilization of SU treatment, although this finding was predominantly driven by high rates of methadone treatment. 22 Building upon those findings, to better understand patterns of healthcare engagement among women with substance use, we described co-utilization of HIV, SU (including drugs, alcohol, tobacco), harm reduction, and mental health services among women with and without HIV who reported current SU.

Methods

Study Population

The WIHS is a large, prospective cohort study that began in 1993 and includes cisgender women either living with HIV or at risk for HIV23,24 from 10 sites across the US (Figure S1). Additional eligibility criteria and recruitment methods are in Supplemental Materials and have been published previously.22 -25 Participants completed follow-up visits every 6 months, during which medical histories were obtained by interviewers and questionnaires, and comprehensive physical examinations were completed.

We included data from participants enrolled at all 10 WIHS sites who reported current SU at the time of last study visit occurring between October 2013 and March 2020. The WIHS protocol was approved by each site’s Institutional Review Board, and all participants provided written informed consent.

Definitions

Current SU was defined as self-reported, non-medical drug use (crack/cocaine, methamphetamines, other amphetamines, opioids, tranquilizers, and other drugs) in the past year. The study questionnaires only assessed SU, not substance use disorders. Although alcohol, tobacco, and marijuana are also substances, we analyzed these separately for this study. Heavy alcohol use for women was defined as >7 drinks/week, based on National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism definitions. HIV serostatus was determined at the last observed study visit. The Center for Epidemiologic Studies-Depression (CES-D) score of ≥16 26 was used to define the presence of depressive symptoms; the CES-D is a validated instrument and self-reported depression scale to identify individuals at risk for depression. History of hepatitis C virus (HCV) assessed prior exposure to HCV, defined as a positive HCV antibody and/or RNA. History of STI included gonorrhea, chlamydia, or syphilis acquired or treated in the past six months.

Substance use treatment utilization was defined in the study questionnaires as self-reported use of any drug treatment in the past year, including inpatient or outpatient detoxification programs, halfway houses, prison/jail-based programs, Narcotics Anonymous, and medications for opioid use disorder (methadone, buprenorphine/naloxone). Alcohol use treatment included inpatient and outpatient detoxification programs, Alcoholics Anonymous, halfway houses, and other treatments. The WIHS questionnaires did not assess medications for alcohol use disorders. Tobacco use treatment included nicotine replacement, other smoking medications (varenicline, bupropion), E-cigarettes, and other treatments. HIV care engagement was care in the last 6 months. Mental health care engagement was seeing a psychiatrist or counselor since last study visit (typically 6 months). Regarding harm reduction services, we assessed use of needle exchange services among women who inject drugs or history of receiving naloxone for accidental overdose. Other harm reduction services were not assessed in questionnaires.

Statistical Analysis

We described participant characteristics by HIV status using counts (percentage) and medians (quartile 1-quartile 3) for categorical and continuous characteristics, respectively. We assessed association between participant characteristics and HIV status using Wald Chi-square or Wilcoxon rank sum test, as appropriate. Among participants with current SU and who were eligible for each healthcare service, we described utilization of each service. We used latent classes (count, percentage) to assess the frequency of co-utilization of HIV care, mental health care, alcohol, and tobacco treatment services by HIV and SU. We also described SU treatment utilization by substance type (stimulants, opioids). We compared utilization of other services by those who did or did not utilize SU treatment using Wald Chi-square tests. Statistical significance was defined as P values <.05. We used SAS (v 9.4) for our analyses.

Results

Participant Characteristics

Our study included 358 women who self-reported current SU (62.6% women with HIV, 37.4% women without HIV). Median age was 54 years (IQR 48-59), and 68.2% self-identified as non-Hispanic Black. Of these, 269 (75.1%) reported past-year stimulant use (crack/cocaine, methamphetamines, or other amphetamines), and 141 (39.4%) reported past-year opioid use (heroin, prescription narcotic misuse, other opioids). Among all participants, 95 (27.0%) reported heavy alcohol use, 276 (77.1%) current tobacco use, and 189 (52.8%) current marijuana use. Other notable characteristics included 161 (46.1%) who reported depressive symptoms, 187 (52.2%) history of physical abuse, and 132 (36.9%) sexual abuse (Table 1).

Table 1.

Demographic, Socio-Behavioral, and Clinical Characteristics Among Women’s Interagency HIV Study (WIHS) Participants Who Reported Current Substance Use, Enrolled in All Study Sites From 2013 to 2020, by HIV Serostatus (n = 358).

| Participant characteristics | Total | Women without HIV | Women living with HIV | P value c |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N = 358 | N = 134 | N = 224 | ||

| N (%) | N (%) b | N (%) b | ||

| Age, years | ||||

| Median (Q1, Q3) | 54 (48, 59) | 54.5 (47, 59) | 54 (49, 59) | .76 |

| Race | .14 | |||

| Non-Hispanic Black | 244 (68.2) | 85 (63.4) | 159 (71.0) | |

| Else | 114 (31.8) | 49 (36.6) | 65 (29.0) | |

| WIHS region | .06 | |||

| New York | 79 (22.1) | 38 (28.4) | 41 (18.3) | |

| Washington DC | 25 (7.0) | 12 (9.0) | 13 (5.8) | |

| California | 82 (22.9) | 32 (23.9) | 50 (22.3) | |

| Illinois | 51 (14.3) | 17 (12.7) | 34 (15.2) | |

| South | 121 (33.8) | 35 (26.1) | 86 (38.4) | |

| Marital status | .20 | |||

| Married/partner | 93 (26.4) | 30 (22.6) | 63 (28.8) | |

| Unmarried/no partner | 259 (73.6) | 103 (77.4) | 156 (71.2) | |

| Highest level of education | .71 | |||

| ≤High school graduation | 250 (69.8) | 92 (68.7) | 158 (70.5) | |

| >High school graduation | 108 (30.2) | 42 (31.3) | 66 (29.5) | |

| Employed (full-time or part-time) | .68 | |||

| No | 300 (84.0) | 114 (85.1) | 186 (83.4) | |

| Yes | 57 (16.0) | 20 (14.9) | 37 (16.6) | |

| Annual household income | .40 | |||

| ≤$242 000 | 302 (88.1) | 112 (86.2) | 190 (89.2) | |

| >$24 000 | 41 (12.0) | 18 (13.9) | 23 (10.8) | |

| Health insurance a | <.001 | |||

| No | 28 (8.0) | 23 (17.3) | 5 (2.3) | |

| Yes | 323 (92.0) | 110 (82.7) | 213 (97.7) | |

| Ever jailed/incarcerated | .41 | |||

| No | 85 (23.7) | 35 (26.1) | 50 (22.3) | |

| Yes | 273 (76.3) | 99 (74.9) | 174 (77.7) | |

| Ever reported physical abuse | .83 | |||

| No | 171 (47.8) | 63 (47.0) | 108 (48.2) | |

| Yes | 187 (52.2) | 71 (53.0) | 116 (51.8) | |

| Ever reported sexual abuse | .56 | |||

| No | 226 (63.1) | 82 (61.2) | 144 (64.3) | |

| Yes | 132 (36.9) | 52 (38.8) | 80 (35.7) | |

| Ever had sex for drugs, money, shelter (baseline visits) | .40 | |||

| No | 129 (36.0) | 52 (38.8) | 77 (34.4) | |

| Yes | 229 (64.0) | 82 (61.2) | 147 (65.6) | |

| Depressive symptoms e | .13 | |||

| No | 188 (53.9) | 78 (59.1) | 110 (50.7) | |

| Yes | 161 (46.1) | 54 (40.9) | 107 (49.3) | |

| History of hepatitis C virus exposure f | .27 | |||

| No | 222 (62.0) | 88 (65.7) | 134 (59.8) | |

| Yes | 136 (38.0) | 46 (34.3) | 90 (40.2) | |

| History of sexually transmitted infection g | >.99 d | |||

| No | 347 (98.6) | 131 (98.5) | 216 (98.6) | |

| Yes | 5 (1.4) | 2 (1.5) | 3 (1.4) | |

| Substance use history and behaviors | ||||

| Alcohol use | .04 | |||

| Abstain | 152 (43.2) | 46 (34.6) | 106 (48.4) | |

| 0-7 drinks/week | 105 (29.8) | 45 (33.8) | 60 (27.4) | |

| >7 drinks/week | 95 (27.0) | 42 (31.6) | 53 (24.2) | |

| Tobacco use (cigarette smoking) | .59 | |||

| Never | 28 (7.8) | 8 (6.0) | 20 (8.9) | |

| Former | 54 (15.1) | 20 (14.9) | 34 (15.2) | |

| Current | 276 (77.1) | 106 (79.1) | 170 (75.9) | |

| Marijuana use in last year | .87 | |||

| No | 169 (47.2) | 64 (47.8) | 105 (46.9) | |

| Yes | 189 (52.8) | 70 (52.2) | 119 (53.1) | |

| Crack/cocaine use in past year | .18 | |||

| No | 100 (27.9) | 43 (32.1) | 57 (24.5) | |

| Yes | 258 (72.1) | 91 (67.9) | 167 (74.6) | |

| Opioid use in past year | .11 | |||

| No | 217 (60.6) | 74 (55.2) | 143 (63.8) | |

| Yes | 141 (39.4) | 60 (44.8) | 81 (36.2) | |

| Methamphetamine use in past year | .99 | |||

| No | 334 (93.3) | 125 (93.3) | 209 (93.3) | |

| Yes | 24 (6.7) | 9 (6.7) | 15 (6.7) | |

| Other amphetamine use in past year | .01 d | |||

| No | 351 (98.0) | 128 (95.5) | 223 (99.6) | |

| Yes | 7 (2.0) | 6 (4.5) | 1 (0.4) | |

| Tranquilizer use (including benzodiazepines) in past year | .66 | |||

| No | 334 (93.3) | 124 (92.5) | 210 (93.8) | |

| Yes | 24 (6.7) | 10 (7.5) | 14 (6.3) | |

| Polysubstance use (≥2 illicit substances) in past year h | .34 | |||

| No | 282 (78.8) | 102 (76.1) | 180 (80.4) | |

| Yes | 76 (21.2) | 32 (23.9) | 44 (19.6) | |

| Injection of drugs in last year | .56 | |||

| No | 316 (88.3) | 120 (89.6) | 196 (87.5) | |

| Yes | 42 (11.7) | 14 (10.5) | 28 (12.5) | |

| History of sharing needles in past year (if yes to injection of drugs) | .33 | |||

| No | 11 (64.7) | 4 (50.0) | 7 (77.8) | |

| Yes | 6 (35.3) | 4 (50.0) | 2 (22.2) | |

| History of accidental overdose in past year | >.99 d | |||

| No | 263 (98.9) | 104 (99.1) | 159 (98.8) | |

| Yes | 3 (1.1) | 1 (1.0) | 2 (1.2) | |

| HIV-related characteristics | ||||

| HIV RNA <200c/mL i | n/a | |||

| No | 56 (27.2) | n/a | 56 (27.2) | |

| Yes | 150 (72.8) | 150 (72.8) | ||

| CD4 >200 cells/µL i | n/a | |||

| No | 21 (9.9) | n/a | 21 (9.9) | |

| Yes | 191 (90.1) | 191 (90.1) | ||

| ART use i | n/a | |||

| No | 24 (10.7) | n/a | 24 (10.7) | |

| Yes | 200 (89.3) | 200 (89.3) | ||

Values in bold indicate statistical significance, defined as p<0.05.

Insurance = health insurance, ADAP, and/or Ryan White Program.

Percentages are column percentages unless otherwise noted and may not total 100 due to rounding.

Chi-square test performed for categorical variables, Wilcoxon rank sum for non-normally distributed continuous variables unless otherwise noted.

Fisher exact test.

As defined as Center for Epidemiologic Studies-Depression (CESD) score ≥16.

History of either hepatitis C antibody and/or RNA positive.

Gonorrhea, chlamydia, or syphilis by self-report or medical examination.

Among crack/cocaine, opioids, methamphetamines, other amphetamines, tranquilizers.

Among women with HIV only.

Among women with current SU, 136 (38.0%) had history of HCV exposure (40.2% women with HIV, 34.3% women without HIV), and 5 (1.4%) reported history of at least one STI in the past six months (1.4% women with HIV, 1.5% women without HIV). When restricted to women with current injection drug use, prevalence of HCV exposure was 54.8%.

Substance Use, Mental Health, and HIV Care Utilization

Among women with current SU, 41.9% (n = 150) utilized SU treatment in the past year. Utilization of SU treatment was 28.3% among those with stimulant use (n = 269) and 77.3% among those with opioid use (n = 141). Additional details on SU treatment by substance type were previously published. 22 Of those with concurrent heavy alcohol use (n = 95), 17 (17.9%) utilized alcohol use treatment, and of those with concurrent tobacco use (n = 276), 21 (7.6%) utilized tobacco use treatment. Among women with current SU and depressive symptoms (n = 161), 63 (39.1%) saw a mental health provider. Among women with current opioid use, 66.7% utilized methadone for treatment in the past year and 5.7% utilized buprenorphine/naloxone. For those with concurrent tobacco use, 4.4% utilized nicotine replacement therapy and <1.0% utilized other medications for smoking cessation.

Among women with HIV and current SU (n = 224), most saw their HIV provider (83.5%) or any health care provider (85.3%) since their last study visit, and 33.5% saw a psychiatrist or counselor. We observed higher HIV care engagement among those who saw a psychiatrist or counselor vs. those who did not (95.9% vs. 77.2%, P < .001), but this was not statistically significantly different between those who utilized SU treatment or not (89.4% vs. 79.7%, P = .06). Lower proportions of women at risk for HIV had seen any healthcare provider compared with women living HIV (73.7% vs. 85.3%, P = .007).

Utilization of Harm Reduction Services

Among women with current SU, 12% (n = 42) reported history of injecting drugs in the past year, however only 17 responded to questions about harm reduction services. Among those who injected drugs at their last visit and responded to these questions (n = 17), 6 (35.3%) reported sharing injecting equipment at least some of the time, either before or after someone else; 12 (70.6%) reported obtaining needles from a needle exchange program at least half of the time. History of accidental overdose was only assessed at one study visit (v50); among the 266 women with current SU who were asked, 3 (1.1%) reported accidental overdose in the last six months, of whom 2 had been given naloxone. The questionnaires did not assess other harm reduction services.

Utilization of Health Services, by SU Treatment Utilization

When comparing by SU treatment utilization (Figure 1), among women with concurrent SU and heavy alcohol use in the past year (n = 95) utilization of alcohol use treatment was 59.1% among women who utilized SU treatment versus 5.5% among those who did not (P < .001). Among women with concurrent SU and tobacco use (n = 276), utilization of tobacco use treatment was low, with 11.6% among women utilizing SU treatment and 4.5% among women who did not (P = .03).

Figure 1.

Co-utilization of health services among women with current substance use (n = 358), by utilization of substance use treatment. Utilization of health services was compared by SU treatment versus no SU treatment using Wald’s chi-square test. SU treatment refers to drug use treatment, including inpatient and outpatient detoxification, halfway house, prison- or jail-based treatments, Narcotics Anonymous, or medications for opioid use disorder. HIV care was assessed among women living with HIV. Mental health care was assessed among women reporting depressive symptoms and current substance use. Alcohol use treatment was assessed among women with heavy alcohol use and current substance use. Tobacco use treatment was assessed among women with current tobacco smoking and current substance use.

Discussion

We previously found high engagement in SU treatment services in the past year among women enrolled in the WIHS, 22 which exceeded national averages of 10 to 30% of lifetime SU treatment among US adults with current SU.9,27 Despite high rates of concomitant tobacco use and heavy alcohol use, we found comparatively low tobacco and alcohol use treatment utilization. Compared to SU treatment among those using opioids, treatment utilization was lower among those using crack/cocaine, the predominant substance used. This may be due in part to the lack of evidence-based medications for stimulant use disorders, 28 compared with medications for opioid use disorders. 8 However, our findings may underestimate stimulant use treatment, as the questionnaires did not assess for psychosocial interventions (eg counseling, contingency management) or pharmacological options (eg topiramate, bupropion + naltrexone) to treat stimulant use disorders. Additional research is urgently needed to expand evidence-based treatment options for stimulant use disorders.

In the WIHS cohort, most women living with HIV had seen their HIV provider in the past 6 months, regardless of SU treatment utilization; this frequent touchpoint with healthcare suggests opportunities for linkage to or integration with other healthcare services for women with HIV and SU. Integrating SU care into HIV prevention and treatment settings may increase access to SU treatment services, and prior studies have shown that integrated SU/HIV treatment services improve health outcomes.29 -33 For women at risk for HIV, despite having similar social vulnerabilities as women living with HIV, we found that fewer had seen any healthcare provider compared with women with HIV. These findings support the need for a status neutral approach to the HIV care continuum, offering comprehensive HIV prevention or treatment (pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) or antiretroviral therapy), quality health care, and wraparound services, regardless of their HIV test result. 34 In an article by Myers et al, 34 several actionable items are emphasized to move toward a status neutral approach to HIV care, including (1) increased identification of individuals at risk for HIV and eligible for PrEP, (2) increasing PrEP awareness, (3) consistent sexual history and substance use history taking by clinicians regardless of perceived risk, (4) promoting sex-positive HIV prevention messaging, (5) expanding the Ryan White care model to offer services to persons without HIV including PrEP, mental health, and substance use services, and (6) expanding public funding for culturally competent sexual health clinics that offer comprehensive HIV prevention and treatment services. Individuals living with HIV and at risk for HIV are not distinct populations, and comprehensive services, such as substance use care, should be accessible regardless of their HIV test result.

Mental health care engagement of nearly 40% in this cohort of women using substances was higher than estimates of 20 to 25% in prior studies of mental health care among people living with HIV.35,36 Considering that psychosocial interventions through counseling is an important part of SU care, it is possible that some of the mental health services also offered SU care, even if individuals did not specifically report SU treatment. Unfortunately, the questionnaires only assessed outpatient detoxification, but not outpatient counseling, as part of SU treatment.

Harm reduction services are a critical part of HIV and substance use care to mitigate drug-related harms, but women are often neglected as target populations of harm reduction interventions and studies. 6 We observed high rates of utilization of syringe service programs among women who inject drugs, however, our ability to assess true utilization of harm reduction services was limited by low number of responses to these questions. Our low responses may be due to lack of awareness of or access to harm reduction services, misunderstanding of the questions, or stigma and fear of punitive measures related to use of such services. We found high prevalence of HCV exposure among women with current substance use, especially injection drug use, emphasizing the important role of syringe exchange programs in preventing HIV and HCV transmission. Despite this, syringe exchange programs remain illegal in 11 U.S. states as of 2021. 37 Future substance use research should include the assessment of harm reduction interventions and their outcomes, beyond just abstinence as the primary outcome of substance use care. In the clinical setting, many low-barrier care models for people who use substances emphasize shared-decision making when establishing goals of treatment, rather than focusing only on treatment guidelines 38 ; for example, goals to reduce substance use, opt for safer routes of use, or practice safer injection practices to reduce infection risk—are all acceptable goals. Including such outcomes in research is needed to assess harm reduction interventions, reduce stigma, and advocate for policy changes that support harm reduction.

We found high rates of polysubstance use with tobacco and alcohol among women with current SU. In our study, women with concurrent SU and heavy alcohol use who did not utilize SU treatment also did not receive alcohol use treatment, and a similar association was seen with tobacco use. Thus, women with polysubstance use with alcohol or tobacco may be a group to prioritize for integrated alcohol, tobacco, and drug treatment programs. Conversely, one study on dual alcohol and tobacco dependence found that participants were more motivated, confident, and active in changing their alcohol use relative to smoking, and initiating cessation of both behaviors simultaneously proved challenging for participants. 39 This could be due to use of another substance perceived as lower risk, while attempting to abstain from another substance. One of the challenges in our current system is the lack of treatments for polysubstance use, and treatments tend to be siloed by type of substance use. Further implementation studies are needed to evaluate the feasibility, acceptability, and effectiveness of integrating tobacco, alcohol, and drug use treatment services into each other and into HIV care settings through novel care delivery models.

Women with HIV have unique preferences and health needs when considering treatment or harm reduction strategies for their SU. Siloing HIV, mental health, and SU care creates additional barriers to care and perpetuates stigma, and therefore interventions to integrate treatment services specifically for women may facilitate engagement in SU care. Implementation research including qualitative data to inform patient-centered approaches are needed when considering the design of such interventions for women with HIV.

Limitations

Limitations of this study include the possibility of response bias and misclassification of SU and treatment utilization in the self-reported questionnaires. Additionally, we could only determine SU but not substance use disorders, as defined by DSM-V criteria. Our study did not assess utilization of preexposure prophylaxis among women without HIV, and questions about harm reduction services were limited, both of which are important components of SU care. Finally, the median age of WIHS participants was >50 years, thus our findings may not be generalizable to younger women with HIV, or to other populations of women without HIV. Analysis from a younger cohort of women is in progress to provide contemporary data on SU treatment among reproductive age women, including pregnant and postpartum women. 40

Conclusion

Among this sample of women with HIV and current SU, we found (1) high engagement in SU treatment and HIV care, but (2) low engagement in alcohol and tobacco use treatments despite high rates of polysubstance use. Syringe service utilization was high among the limited number of women who inject drugs who were assessed, but harm reduction service utilization was not consistently evaluated at all study visits. Integrated drug, alcohol, and tobacco treatment programs are critical pieces of optimizing the HIV care continuum and clinical outcomes and should be incorporated as standard of care among women experiencing this syndemic.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental material, sj-docx-1-jpc-10.1177_21501319241285531 for Co-Utilization of HIV, Substance Use, Mental Health Services Among Women With Current Substance Use: Opportunities for Integrated Care? by Ayako W. Fujita, Aditi Ramakrishnan, C. Christina Mehta, Oyindamola B. Yusuf, Azure B. Thompson, Steven Shoptaw, Adam W. Carrico, Adaora A. Adimora, Ellen Eaton, Mardge H. Cohen, Jennifer P. Jain, Adebola Adedimeji, Michael Plankey, Deborah L. Jones, Aruna Chandran, Jonathan A. Colasanti and Anandi N. Sheth in Journal of Primary Care & Community Health

Acknowledgments

Data in this manuscript were collected by the Women’s Interagency HIV Study (WIHS), now the Multicenter AIDS Cohort Study/WIHS Combined Cohort Study (MWCCS). The authors gratefully acknowledge the contributions of the study participants and dedication of the staff at the MWCCS sites. We would also like to thank the WIHS site coinvestigators for serving as site liaisons for data collaboration.

Footnotes

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: MWCCS (Principal Investigators): Atlanta Clinical Research Site (CRS) (Ighovwerha Ofotokun, Anandi Sheth, and Gina Wingood), U01-HL146241; Baltimore CRS (Todd Brown and Joseph Margolick), U01-HL146201; Bronx CRS (Kathryn Anastos, David Hanna, and Anjali Sharma), U01-HL146204; Brooklyn CRS (Deborah Gustafson and Tracey Wilson), U01- HL146202; Data Analysis and Coordination Center (Gypsyamber D’Souza, Stephen Gange and Elizabeth Topper), U01-HL146193; Chicago-Cook County CRS (Mardge Cohen and Audrey French), U01-HL146245; Chicago-Northwestern CRS (Steven Wolinsky), U01-HL146240; Northern California CRS (Bradley Aouizerat, Jennifer Price, and Phyllis Tien), U01-HL146242; Los Angeles CRS (Roger Detels and Matthew Mimiaga), U01-HL146333; Metropolitan Washington CRS (Seble Kassaye and Daniel Merenstein), U01-HL146205; Miami CRS (Maria Alcaide, Margaret Fischl, and Deborah Jones), U01-HL146203; Pittsburgh CRS (Jeremy Martinson and Charles Rinaldo), U01-HL146208; UAB-MS CRS (Mirjam-Colette Kempf, Jodie Dionne-Odom, and Deborah Konkle-Parker), U01-HL146192; University of North Carolina (UNC) CRS (Adaora Adimora and Michelle Floris-Moore), U01-HL146194. The MWCCS is funded primarily by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, with additional co-funding from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, National Institute on Aging, National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research, National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID), National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke, National Institute of Mental Health, National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA), National Institute of Nursing Research, National Cancer Institute, National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism, National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders, National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities, and in coordination and alignment with the research priorities of the NIH, Office of AIDS Research. MWCCS data collection is also supported by UL1-TR000004 (University of California, San Francisco Clinical and Translational Science Award), UL1-TR003098 (Johns Hopkins University Institute for Clinical and Translational Research), UL1-TR001881 (University of California, Los Angeles Clinical and Translational Science Institute), P30-AI-050409 (Atlanta Center for AIDS Research [CFAR]), P30-AI-073961 (Miami CFAR), P30-AI-050410 (UNC CFAR), P30-AI-027767 (UAB CFAR), P30-MH-116867 (Miami Center for HIV and Research in Mental Health), UL1-TR001409 (DC CTSA), KL2-TR001432 (DC CTSA), and TL1-TR001431 (DC CTSA). A. W. F. is supported by the NCATS of the NIH (UL1TR002378 and TL1TR002382) and NIAID (T32AI157855). Dr. Jain is supported by a Career Development Award from NIDA (5K01DA056306-02). The authors gratefully acknowledge services provided by the Emory CFAR funded through NIAID (P30-AI- 050409).

Disclaimer: The contents of this publication are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health (NIH).

In memoriam: We dedicate this work to the memory of our colleague and co-author on this manuscript, Dr. Adaora Adimora, who passed away during its preparation.

ORCID iD: Ayako W. Fujita  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-8890-6434

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-8890-6434

Supplemental Material: Supplemental material for this article is available online.

References

- 1. Cook JA, Burke-Miller JK, Steigman PJ, et al. Prevalence, comorbidity, and correlates of psychiatric and substance use disorders and associations with HIV risk behaviors in a multisite cohort of women living with HIV. AIDS Behav. 2018;22(10):3141-3154. doi: 10.1007/s10461-018-2051-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Zhang Y, Wilson TE, Adedimeji A, et al. The impact of substance use on adherence to antiretroviral therapy among HIV-infected women in the United States. AIDS Behav. 2018;22(3):896-908. doi: 10.1007/s10461-017-1808-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Labisi TO, Podany AT, Fadul NA, Coleman JD, King KM. Factors associated with viral suppression among cisgender women living with human immunodeficiency virus in the United States: an integrative review. Womens Health (Lond). 2022;18:17455057221092267. doi: 10.1177/17455057221092267 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Hartzler B, Dombrowski JC, Crane HM, et al. Prevalence and predictors of substance use disorders among HIV care enrollees in the United States. AIDS Behav. 2017;21(4):1138-1148. doi: 10.1007/s10461-016-1584-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Iversen J, Page K, Madden A, Maher L. HIV, HCV, and health-related harms among women who inject drugs: implications for prevention and treatment. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2015;69 Suppl 2:S176-S181. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0000000000000659 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Pinkham S, Malinowska-Sempruch K. Women, harm reduction and HIV. Reprod Health Matters. 2008;16(31):168-181. doi: 10.1016/S0968-8080(08)31345-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Larochelle MR, Stopka TJ, Xuan Z, Liebschutz JM, Walley AY. Medication for opioid use disorder after nonfatal opioid overdose and mortality. Ann Intern Med. 2019;170(6):430-431. doi: 10.7326/L18-0685 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Sordo L, Barrio G, Bravo MJ, et al. Mortality risk during and after opioid substitution treatment: systematic review and meta-analysis of cohort studies. BMJ. 2017;357:j1550. doi: 10.1136/bmj.j1550 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Lipari RN, Park-Lee E, Van Horn S. America’s Need for and Receipt of Substance Use Treatment in 2015. The CBHSQ Report. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; 2013:1-7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. El-Bassel N, Terlikbaeva A, Pinkham S. HIV and women who use drugs: double neglect, double risk. Lancet. 2010;376(9738):312-314. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61026-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Greenfield SF, Brooks AJ, Gordon SM, et al. Substance abuse treatment entry, retention, and outcome in women: a review of the literature. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2007;86(1):1-21. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2006.05.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Green CA. Gender and use of substance abuse treatment services. Alcohol Res Health. 2006;29(1):55-62. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Harris MTH, Laks J, Hurstak E, et al. “If you’re strung out and female, they will take advantage of you”: a qualitative study exploring drug use and substance use service experiences among women in Boston and San Francisco. J Subst Use Addict Treat. 2023;157:209190. doi: 10.1016/j.josat.2023.209190 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Oldfield BJ, Munoz N, McGovern MP, et al. Integration of care for HIV and opioid use disorder. AIDS. 2019;33(5):873-884. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0000000000002125 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Hickey MD, Imbert E, Appa A, et al. HIV treatment outcomes in POP-UP: drop-in HIV primary care model for people experiencing homelessness. J Infect Dis. 2022;226(3):S353-S362. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiac267 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Dombrowski JC, Ramchandani M, Dhanireddy S, Harrington RD, Moore A, Golden MR. The max clinic: medical care designed to engage the hardest-to-reach persons living with HIV in Seattle and King County, Washington. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2018;32(4):149-156. doi: 10.1089/apc.2017.0313 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Henkhaus ME, Hussen SA, Brown DN, et al. Barriers and facilitators to use of a mobile HIV care model to re-engage and retain out-of-care people living with HIV in Atlanta, Georgia. PLoS One. 2021;16(3):e0247328. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0247328 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Tookes HE, Oxner A, Serota DP, et al. Project T-SHARP: study protocol for a multi-site randomized controlled trial of tele-harm reduction for people with HIV who inject drugs. Trials. 2023;24(1):96. doi: 10.1186/s13063-023-07074-w [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Goodman-Meza D, Shoptaw S, Hanscom B, et al. Delivering integrated strategies from a mobile unit to address the intertwining epidemics of HIV and addiction in people who inject drugs: the HPTN 094 randomized controlled trial protocol (the INTEGRA Study). Trials. 2024;25(1):124. doi: 10.1186/s13063-023-07899-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Vogel EA, Ly K, Ramo DE, Satterfield J. Strategies to improve treatment utilization for substance use disorders: a systematic review of intervention studies. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2020;212:108065. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2020.108065 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Haldane V, Cervero-Liceras F, Chuah FL, et al. Integrating HIV and substance use services: a systematic review. J Int AIDS Soc. 2017;20(1):21585. doi: 10.7448/IAS.20.1.21585 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Fujita AW, Ramakrishnan A, Mehta CC, et al. Substance use treatment utilization among women with and without human immunodeficiency virus. Open Forum Infect Dis. 2023;10(1):ofac684. doi: 10.1093/ofid/ofac684 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Barkan SE, Melnick SL, Preston-Martin S, et al. The women’s interagency HIV study. WIHS Collaborative Study Group. Epidemiology. 1998;9(2):117-125. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Bacon MC, von Wyl V, Alden C, et al. The women’s interagency HIV study: an observational cohort brings clinical sciences to the bench. Clin Diagn Lab Immunol. 2005;12(9):1013-1019. doi: 10.1128/CDLI.12.9.1013-1019.2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Adimora AA, Ramirez C, Benning L, et al. Cohort profile: the women’s interagency HIV study (WIHS). Int J Epidemiol. 2018;47(2):393-394i. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyy021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Radloff LS. The CES-D Scale: a self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Appl Psychol Meas. 1977;1:385-401. [Google Scholar]

- 27. Boden MT, Hoggatt KJ. Substance use disorders among veterans in a nationally representative sample: prevalence and associated functioning and treatment utilization. J Stud Alcohol Drugs. 2018;79(6):853-861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Ronsley C, Nolan S, Knight R, et al. Treatment of stimulant use disorder: a systematic review of reviews. PLoS One. 2020;15(6):e0234809. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0234809 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Altice FL, Sullivan LE, Smith-Rohrberg D, Basu S, Stancliff S, Eldred L. The potential role of buprenorphine in the treatment of opioid dependence in HIV-infected individuals and in HIV infection prevention. Clin Infect Dis. 2006;43 Suppl 4:S178-S183. doi: 10.1086/508181 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Altice FL, Bruce RD, Lucas GM, et al. HIV treatment outcomes among HIV-infected, opioid-dependent patients receiving buprenorphine/naloxone treatment within HIV clinical care settings: results from a multisite study. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2011;56 Suppl 1:S22-S32. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e318209751e [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Fiellin DA, Weiss L, Botsko M, et al. Drug treatment outcomes among HIV-infected opioid-dependent patients receiving buprenorphine/naloxone. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2011;56 Suppl 1:S33-S38. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3182097537 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Lucas GM, Chaudhry A, Hsu J, et al. Clinic-based treatment of opioid-dependent HIV-infected patients versus referral to an opioid treatment program: a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med. 2010;152(11):704-711. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-152-11-201006010-00003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Eaton EF, Tamhane A, Turner W, Raper JL, Saag MS, Cropsey KL. Safer in care: a pandemic-tested model of integrated HIV/OUD care. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2022;231:109241. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2021.109241 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Myers JE, Braunstein SL, Xia Q, et al. Redefining prevention and care: a status-neutral approach to HIV. Open Forum Infect Dis. 2018;5(6):ofy097. doi: 10.1093/ofid/ofy097 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Hussen SA, Camp DM, Wondmeneh SB, et al. Mental health service utilization among young black gay, bisexual, and other men who have sex with men in HIV care: a retrospective cohort study. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2021;35(1):9-14. doi: 10.1089/apc.2020.0202 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Weaver MR, Conover CJ, Proescholdbell RJ, et al. Utilization of mental health and substance abuse care for people living with HIV/AIDS, chronic mental illness, and substance abuse disorders. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2008;47(4):449-458. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3181642244 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Opioid and Health Indicators Database. Syringe Exchange Program Legality. 2021. Accessed May 22, 2024. https://opioid.amfar.org/indicator/SSP_legality

- 38. Dombrowski JC, Ramchandani MS, Golden MR. Implementation of low-barrier human immunodeficiency virus care: lessons learned from the max clinic in Seattle. Clin Infect Dis. 2023;77(2):252-257. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciad202 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Stotts AL, Schmitz JM, Grabowski J. Concurrent treatment for alcohol and tobacco dependence: are patients ready to quit both? Drug Alcohol Depend. 2003;69(1):1-7. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(02)00227-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Sheth AN, Adimora AA, Golub ET, et al. Study of treatment and reproductive outcomes among reproductive-age women with HIV infection in the Southern United States: protocol for a longitudinal cohort study. JMIR Res Protoc. 2021;10(12):e30398. doi: 10.2196/30398 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental material, sj-docx-1-jpc-10.1177_21501319241285531 for Co-Utilization of HIV, Substance Use, Mental Health Services Among Women With Current Substance Use: Opportunities for Integrated Care? by Ayako W. Fujita, Aditi Ramakrishnan, C. Christina Mehta, Oyindamola B. Yusuf, Azure B. Thompson, Steven Shoptaw, Adam W. Carrico, Adaora A. Adimora, Ellen Eaton, Mardge H. Cohen, Jennifer P. Jain, Adebola Adedimeji, Michael Plankey, Deborah L. Jones, Aruna Chandran, Jonathan A. Colasanti and Anandi N. Sheth in Journal of Primary Care & Community Health