Abstract

Aim

The systematic Airway, Breathing, Circulation, Disability, and Exposure (ABCDE) approach is a priority-based consensus approach for the primary assessment of all categories of critically ill or injured patients. The aims of this review are to provide a wide overview of all relevant literature about existing ABCDE assessment tools, adherence to the ABCDE approach and related outcomes of teaching or application of the ABCDE approach by healthcare professionals.

Methods

A comprehensive scoping review was conducted following the Joanna Briggs Institute guidelines and reported according to the PRISMA-ScR Checklist. An a priori protocol was developed. In March 2024, MEDLINE, EMBASE, CINAHL and Cochrane library were searched to identify studies describing healthcare professionals applying the ABCDE approach in either simulation settings or clinical practice. Two reviewers independently screened records for inclusion and performed data extraction.

Results

From n = 8165 results, fifty-seven studies met the inclusion criteria and reported data from clinical care (n = 27) or simulation settings (n = 30). Forty-two studies reported 39 different assessment tools, containing 5 to 36 items. Adherence to the approach was reported in 43 studies and varied from 18–84% in clinical practice and from 29–35% pre-intervention to 65–97% post-intervention in simulation settings. Team leader presence and attending simulation training improved adherence. Data on patient outcomes were remarkably scarce.

Conclusion

Many different tools with variable content were identified to assess the ABCDE approach. Adherence was the most frequently reported outcome and varied widely among included studies. However, association between the ABCDE approach and patient outcomes is yet to be investigated.

Keywords: ABCDE, Airway Breathing Circulation Disability Exposure, Primary survey, Assessment, Adherence

Introduction

The Airway, Breathing, Circulation, Disability, Exposure (ABCDE) approach is a systematic approach for the primary survey of all categories of critically ill or injured patients.1 Initially, the ABCDE approach was developed to improve trauma care, but nowadays it is used in all potential medical emergencies and applicable to patients of all ages.2, 3 The ABCDE approach is advocated to be a universal tool with the aim to assess and treat patients conform the ‘treat first what kills first’ principle. However, ABCDE algorithms and assessment tools differ amongst studies and life support courses.4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9 Several studies and personal observations suggested that adherence to the ABCDE approach varies between healthcare professionals.4, 5 Variations in algorithms and suboptimal adherence to this approach might hypothetically affect patient outcomes. The ABCDE approach is based on expert consensus and reviews on adherence to the ABCDE approach specifically or related outcomes could not be identified. As the ABCDE approach is recommended by (inter)national life support courses and guidelines and a majority of healthcare professionals is ABCDE trained,6, 7, 8, 9 insight into adherence and the impact on outcomes is of importance for every healthcare professional possibly encountering critically ill or injured patients. With the purpose to identify research into the ABCDE approach and its outcomes, a scoping review was considered the most suitable approach.10, 11 The objectives of this study are to provide an overview of 1) all relevant literature about existing ABCDE assessment tools, 2) reported adherence to the ABCDE approach (completeness and/or correct order) and influencing factors, and 3) other professional, team or patient related outcomes of teaching and application of the ABCDE approach by healthcare professionals in a hospital setting.

Methods

This scoping review follows the guidelines of the Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) manual.12 The PRISMA-ScR Checklist was used to document the selection process and is attached in Appendix A.13 As recommended by Peters et al.,14 an a priori protocol was developed and published in the Open Science Framework.15

Eligibility criteria

The following eligibility criteria were applied:

Participants: healthcare professionals (nurses, nurse practitioners, physician assistants, residents, medical specialists) or healthcare students.

Concept: the ABCDE approach and its application in clinical practice or in a simulation setting. Since the ABCDE approach is part of the primary survey, studies reporting specifically on the primary survey (without distinction of the different ABCDE domains) were considered eligible as well.

Context: any acute care situation in a hospital where the ABCDE approach was taught or applied in clinical practice or simulation settings (including courses).

Study selection: All type of studies (quantitative, qualitative, mixed-method), except reviews, were considered eligible if assessment of or adherence to the ABCDE approach, or any other outcome related to application or teaching of the ABCDE approach was described.

The following exclusion criteria were applied: conference abstracts, languages other than English, Dutch, German, French and Spanish and studies performed in a pre-hospital setting. Although the application of the ABCDE approach itself should not differ from a hospital setting, the diagnostical, therapeutical and team resources differ significantly. The literature search was not limited by year of publication.

Information sources and search strategy

A three-step search strategy was performed as recommended by Briggs.10 First, an initial limited search was conducted, followed by an analysis of relevant keywords used in titles and abstracts and of index terms (MeSH terms) used to label the identified articles. Second, a complete and thorough search strategy was constructed with the assistance of an experienced literature specialist. The final search strategy is available in Appendix B. This search was executed in MEDLINE, EMBASE, CINAHL and the Cochrane library from inception until March 3, 2024. Thirdly, backward citation searching was performed on all included full text articles.

Study selection

The search results were collected and deduplicated in EndNote X9, and subsequently imported into Rayyan (https://rayyan.qcri.org). One reviewer (LB) screened all titles and abstracts for relevance and classified the articles into two categories: ‘clearly not eligible’ (unquestionably wrong participants, wrong context and wrong concept stated in title or abstract) and ‘potentially eligible 1'. The articles in the category ‘potentially eligible 1' were independently screened on title and abstract by two reviewers (LB, ML) and classified into ‘not eligible’ and ‘potentially eligible 2'. Full-text screening was performed on all ‘potentially eligible 2' articles by LB and ML independently. Eventually, backward citation searching was conducted on all included full text articles by LB and ML. In every stage of the selection, discrepancies were solved through discussion with a third reviewer (MH).

Data items and data charting process

Two reviewers (LB and ML) individually extracted and assessed the data of the selected full-text articles using a specifically designed pre-piloted spreadsheet, adapted from the JBI scoping review methodological guidance (Appendix D).10 Abstracted data included article characteristics, study aims, methods, participants, concept, context, discipline, described outcomes and the ABCDE algorithm used. No authors were contacted for obtaining additional data. No formal methodological quality assessment was performed given the broad scope of this review and the expected heterogeneity of the included studies.

Synthesis of results

After data extraction, both quantitative and qualitative content analyses were conducted. A frequency analysis was performed to map the distribution of studies by year of publication, country of origin, study design, concept (ABCDE or primary survey), context (clinical practice or simulation) and discipline. Content analysis was performed by one reviewer (LB) and checked by a second reviewer (ML). Reported outcomes were categorized into three main outcome groups: 1) assessment tools, 2) adherence to the ABCDE approach and 3) other outcomes. The outcome group was divided into the following subgroups: a. professional outcomes (e.g. confidence and knowledge), b. team outcomes (such as communication and teamwork), c. patient outcomes (such as mortality and length of hospital stay), d. other outcomes.

Results

Selection of sources of evidence

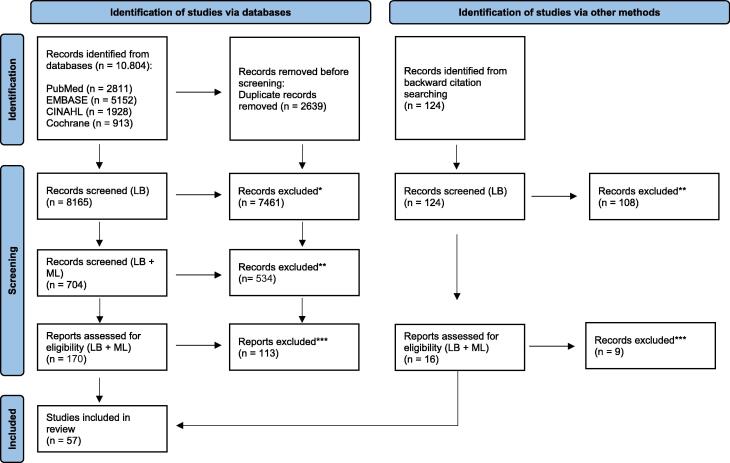

The search identified 10,416 citations. After removing duplicates, screening on title and abstract, followed by full text screening and discussion, 50 studies were included (Fig. 1).4, 5, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32, 33, 34, 35, 36, 37, 38, 39, 40, 41, 42, 43, 44, 45, 46, 47, 48, 49, 50, 51, 52, 53, 54, 55, 56, 57, 58, 59, 60, 61, 62, 63 Backward citation searching identified another 7 articles eligible for inclusion,64, 65, 66, 67, 68, 69, 70 resulting in a total of 57 studies.

Fig. 1.

Flow chart study selection. * Neither participants, concept nor context stated in title or abstract. ** Wrong participants, concept or participants stated in title or abstract. *** Reasons for exclusion (wrong participants, wrong concept, wrong context) can be found in Appendix C.

Characteristics of sources of evidence

The majority of the included studies (n = 38, 66%) were published in the last ten years (Table 1). Most studies were conducted in Europe (n = 23, 40%) and North America (n = 23, 40%). The design varied from observational studies (n = 37, 64%); intervention studies (n = 19, 33%) of which 8 were randomized,4, 21, 22, 38, 41, 67, 69, 70 to one mixed-method study.50 Table 1 shows study characteristics sorted by medical discipline. Half of the studies reported data from clinical practice and half from a simulation setting. The major discipline was traumatology (n = 36, 62%), of which 21 concerned paediatric trauma. Two studies investigated the assessment of the ABCDE approach in healthy individuals.

Table 1.

Study characteristics.

| First author | Year, Country | Study design | Context | Concept | Participants/Assessments | Reported outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CLINICAL PRACTICE | ||||||

| TRAUMA | ||||||

| Aukstakalnis17 | 2020, Lithuania | Observational | ED* | Primary survey | 143 team assessments |

Adherence: Adherence, time to completion Team: Non-technical skills |

| Bergs23 | 2005, The Netherlands | Observational | ED* | ABCDE† | 193 team assessments | Team: Communication |

| Gyedu34 | 2022, Ghana | Observational | ED* | Primary survey | 1006 assessments by ED health care providers (doctors, physician assistants, nurses) | Adherence: Primary assessment and actions, Reassessment |

| Hoff35 | 1997, USA | Observational | Trauma area* | Primary survey† | 425 team assessments | Adherence: Adherence, time to completion |

| Koko48 | 2023, Sudan | Observational | Trauma room | ABCDE | 50 team assessments | Adherence: Adherence, facilitators and barriers |

| Lubbert66 | 2009, The Netherlands | Observational | ED* | Primary survey | 387 team assessments |

Adherence: Quality appraisal for ATLS items, timing of ATLS items Team: Errors in team organization |

| Maluso51 | 2016, USA | Observational | ED* | ABCDE | 170 team assessments |

Adherence: Tasks completed at 2 min and 5 min Team: Team size, team leader performance, closed loop communication |

| Ritchie57 | 1999, Australia | Observational | ED | Primary survey | 50 team assessments | Adherence: Time to completion, team leader performance |

| Spanjersberg59 | 2009, The Netherlands | Observational | ED* | ABCDE | 193 team assessments | Adherence: Protocol compliance, trauma resuscitation time, timing of ATLS steps |

| Tsang61 | 2013, Canada | Observational | ED* | Primary survey | 508 team assessments | Adherence: Compliance rate with ATLS protocols |

| PAEDIATRIC TRAUMA | ||||||

| Botelho24 | 2020, Brazil | Observational | ED* | ABCDE | 64 assessments by physicians (surgeons, surgical residents, paediatricians) | Adherence: Adherence |

| Botelho25 | 2021, Brazil | Interventional | ED* | ABCDE | 80 assessments by physicians (surgeon, surgery resident, paediatrician) | Adherence: Adherence, time to initiate primary survey |

| Carter26 | 2013, USA | Observational | ED* | Primary survey | 237 team assessments | Adherence: Frequency, time to completion, associated factors |

| Gala31 | 2016, USA | Observational | ED* | ABCD | 228 assessments by paediatric or emergency medicine resident, nurse practitioner, fellow or attending | Adherence: Adherence, time to completion |

| Kelleher43 | 2014, USA | Interventional | ED* | ABCDE | 435 team assessments | Adherence: Primary survey tasks, time to completion |

| Kelleher44 | 2014, USA | Interventional | ED | Primary survey | 437 assessments by resident or nurse practitioner | Adherence: Model fitness, conformance, task completion sequence pattern |

| Kelleher45 | 2014, USA | Observational | ED | ABCDE | 201 team assessments | Adherence: Task completion |

| O’Connell53 | 2017, USA | Observational | ED* | Primary survey | 135 team assessments | Adherence: Frequency, time to completion tasks |

| Oakley68 | 2005, Australia | Observational | ED | ABCD | 90 team assessments | Adherence: Errors |

| Taylor60 | 2020, USA | Interventional | ED* | Primary survey† | 54 team assessments | Adherence: Time to completion |

| Wurster62 | 2017, USA | Observational | ED | ABCDE | 142 team assessments |

Adherence: Adherence, resuscitation time, timing of ATLS steps Patient: ED length of stay |

| Yan63 | 2020, USA | Observational | Trauma bay* | Primary survey | 188 assessments by residents | Adherence: Primary survey scores |

| SURGERY | ||||||

| Glanville33 | 2021, Australia | Interventional | Surgical department | ABCDE | 74 nurses | Adherence: Adherence, time assessment |

| CRITICALLY ILL ADULT PATIENTS | ||||||

| Olgers5 | 2017, The Netherlands | Observational | ED | ABCDE | 270 assessments by attending physician, consultant, resident, medical student. |

Adherence: Frequency, adherence, time to initiation, time to completion Professional: Reasons for not applying |

| CRITICALLY ILL PATIENTS | ||||||

| Althobity16 | 2024, Saudi Arabia | Observational | University medical centre | ABCDE† | 242 health care professionals (anaesthesiology, paediatrics, ED, ICU, NICU) | Professional: Knowledge |

| Schoeber58 | 2022, The Netherlands | Observational | University medical centre | ABCDE† | 240 health care professionals (ED, anaesthesiology, paediatrics, ICU, PICU and NICU) | Professional: Knowledge ABCDE |

| PAEDIATRICS | ||||||

| Renning56 | 2022, Malawi | Observational | Paediatric critical care units | ABCDE | 153 nurses | Professional: Confidence |

| SIMULATION SETTING | ||||||

| TRAUMA | ||||||

| Barnes18 | 2017, Malawi | Observational | Course | ABCDE† | 20 nurses | Professional: Self-reported confidence |

| Gillman32 | 2016, Canada | Observational | Course | Primary survey | 11 teams |

Adherence: Global rating score, ATLS checklist Professional: Satisfaction with course |

| Holcomb36 | 2002, USA | Interventional |

Course | ABCD | 10 assessments by 10 teams |

Adherence: 5 scored tasks, 8 timed tasks, Final scores Professional: Comfortable caring for critically ill patients |

| Hultin39 | 2019, Sweden | Observational | Training | ABCDE | 55 medical students performed 23 team assessments |

Adherence: ABCDE checklist Professional: Situational Awareness Team: TEAM |

| Long49 | 2019, USA | Observational | Training | Primary survey† | 67 assessments by multidisciplinary teams | Adherence: Time to completion primary survey |

| Pringle55 | 2015, Nicaragua | Interventional | Course | Primary survey | 33 physicians and resident physicians |

Adherence: Number of critical actions completed, time to completion Professional: Knowledge test |

| PAEDIATRIC TRAUMA | ||||||

| Auerbach64 | 2014, USA | Interventional, Qualitative | Training | ABCD | 398 health care providers performed 22 simulations |

Adherence: Trauma team performance Team: Team organization |

| Civantos Fuentes27 | 2011, Spain | Observational | Course | Primary survey | 156 paediatric primary care paediatricians | Adherence: Compliance, time |

| Dickerson- Young28 | 2020, USA | Observational, Qualitative |

Course | ABCDE | 49 participants (paediatric residents, medical students, and nurse practitioners) |

Adherence: Time to completion Professional: Confidence after simulation |

| Falcone30 | 2008, USA | Interventional | Course | ABCD | 46 scenario’s performed by 160 multidisciplinary team members | Adherence: Adherence appropriate and timely care measures, task achievement, performance in early and late simulation sessions |

| Holland37 | 2020, USA | Observational | Training | Primary survey† | 245 paediatric residents | Professional: Confidence |

| Hulfish38 | 2021, USA | Interventional | Training | ABCDE | 131 simulated trauma resuscitations performed by teams. |

Adherence: Checklist elements completed, time to completion Professional: Mental efforts |

| Hunt65 | 2006, USA | Observational | Training | Primary survey | 35 simulation scenarios by 35 teams | Adherence: ED tasks in need of improvement, ED tasks performed well |

| Parsons69 | 2014, USA | Qualitative, Interventional |

Training | ABCDE | 48 simulation scenarios performed by teams. |

Adherence: ATLS performance score, Checklist compliance Professional: Workload during using the checklist. |

| CRITICALLY ILL ADULT PATIENTS | ||||||

| Berg20 | 2021, Norway | Observational | Training | ABCDE† | 3 scenarios by 1 emergency department team | Adherence: Overall score, clinical actions, time |

| Drost – de Klerck29 | 2020, The Netherlands | Observational | Course | ABCDE | 30 participants: first year residents and non-residents | Adherence: Primary assessment score, skills and competences |

| Innocenti40 | 2022, Italy | Observational | Course | ABCDE | 76 residents emergency medicine | Adherence: ABCDE assessment, ABCDE management |

| Jonsson41 | 2021, Sweden | Observational | Course | ABCDE† | 105 participants (26 physicians, 79 nurses) in 26 teams ICU |

Adherence: ABCDE Checklist Team: Leadership, teamwork, task management |

| Jonsson42 | 2021, Sweden | Interventional | Training | ABCDE | 20 inter-professional teams, 75 nurses and physicians |

Adherence: ABCDE-checklist Professional: Situation awareness Team: TEAM |

| Kliem47 | 2022, Switzerland | Observational | Training | ABCDE | 74 residents in intensive care medicine, emergency medicine, internal medicine, and neurology |

Adherence: Adherence, risk-factors non-adherence, deduced management |

| Macnamara50 | 2021, UK | Mixed-methods | Training | ABCDE† | 20 final year medical students | Other: Simulation experience, relation to clinical practice |

| Merriman67 | 2014, UK | Interventional | Training | ABCDE | 34 first year undergraduate nursing students |

Adherence: OSCE (Objective Structured Clinical Examination) Professional: Self-efficacy and self-reported competency, Other: evaluation teaching method |

| Stayt70 | 2015, UK | Interventional | Training | ABCDE | 98 first year nursing students |

Adherence: OSCE Professional: Self-efficacy and self-reported competency, Other: Evaluation of teaching method |

| Peran54 | 2020, Czech Republic | Observational | Training | ABCDE | 48 paramedic students | Adherence: Number performed assessment steps, order of assessment steps, time |

| INTERNAL MEDICINE | ||||||

| Kiessling46 | 2022, Sweden | Interventional | Training | ABCDE† | 123 participants: 21 physicians, 20 nurses, 14 assistant nurses, 37 medical students and 31 student nurses. |

Professional: Self-efficacy |

| PAEDIATRICS | ||||||

| Benito19 | 2018, Spain | Observational, Qualitative | Course | ABCDE† | 402 paediatricians, emergency paediatricians, paediatric residents, other professionals |

Professional: Application Other: Evaluation course |

| Nadel52 | 2000, USA | Interventional | Course | ABCD | 58 paediatric residents |

Adherence: Time to completion Professional: Knowledge, technical skills, experience and confidence |

| NEONATOLOGY | ||||||

| Linders4 | 2021, The Netherlands | Interventional | Training | ABCDE | 72 nurses, nurse practitioners, physician assistants, paediatric residents, neonatal fellows, neonatologists. | Adherence: Adherence |

| HEALTHY INDIVIDUALS | ||||||

| Berg22 | 2020, Norway | Interventional | Training | ABCDE | 289 medical and nursing students | Adherence: Documentation 8 ABCDE items in 5 min. |

| Berg21 | 2021, Norway | Interventional | Training | ABCDE | 289 medical and nursing students |

Adherence: Documentation 8 ABCDE items in 5 min Professional: Confidence |

| ED=Emergency Department, * Level 1 trauma center, † ABCDE or primary survey items not reported | ||||||

Results of individual sources of evidence

-

1)

ABCDE assessment tools

Of the 48 studies reporting adherence to or time to complete the ABCDE approach or primary survey, 42 studies published 39 different assessment tools. Of these 42 studies, 23 studies used the term ABCDE approach in their assessment tools, 14 studies primary survey without distinction between the different domains of the ABCDE, and five studies used an incomplete approach, i.e. ABCD (Table 1). Two studies that reported adherence,35, 49 two studies that reported time to completion,28, 60 and one study reporting both,20 did not elucidate which items were included in their assessment tool. The assessment tools were used during live observations or video reviews and scored team performance or individual performance (Table 2). The assessment tools were developed to 1) evaluate adherence to the ABCDE approach or primary survey, 2) investigate factors influencing adherence, 3) identify omissions during the assessment, 4) optimize team performance (leadership and optimum team size) or 5) evaluate teaching and training methods. For the 39 assessment tools used, different validation methods were identified and reported in Table 2. Sixteen tools were based on a life support course protocol (e.g. ATLS or APLS). Sixteen studies used previously published assessment tools of which two studies did not meet the inclusion criteria of this review.71, 72 Only one study reported intra-rater reliability (Intraclass Correlation Coefficient (ICC) which was 0.87 (95% Confidence Interval 0.74–0.94).4 Six studies assessed inter-rater reliability measured with different statistical tests, described in Table 2. Eight studies used expert consensus to compose an assessment tool. The number of items in the assessment tools ranged from 5 to 36. Nineteen assessment tools included subsequent actions such as radiology investigations, laboratory tests, and treatment such as oxygen supplementation or fluid resuscitation, which are not components of the ABCDE assessment itself. The assessment tool scores were used for improvement of a training program in two studies17, 66 and in some studies, all participants or worst performers were invited for a review of their assessment as a learning opportunity.57, 60, 62

-

2)

Adherence towards the ABCDE approach

Table 2.

Summary of assessment tools.

| Author | Aim study | Participants |

Context |

Content |

Observation |

Validation |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Individual | Team | Simulation | Clinical care | ABCDE-items (N) | Assess-ment | Action | Video | Live | Protocol based | Published tools | Reliability ((ICC/κ/r/ρ)*) | Expert consensus | ||

| Auerbach64 | Measure impact of a quality improvement simulation program | ✓ | ✓ | 11 | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||

| Aukstakalnis17 | Performance analysis and feedback | ✓ | ✓ | 11 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ATLS | |||||||

| Berg22 | Non-inferiority of individual VR versus traditional equipment | ✓ | ✓ | 8 | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||

| Berg21 | Non-inferiority of multiplayer VR versus traditional equipment | ✓ | ✓ | 8 | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||

| Botelho24 | Assess adherence after checklist introduction | ✓ | ✓ | 11 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ATLS | |||||||

| Botelho25 | Evaluate of adherence | ✓ | ✓ | 12 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ATLS | ✓⁰ | |||||

| Carter26 | Identify factors related to delayed and omitted primary survey tasks | ✓ | ✓ | 8 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ATLS | ✓inter-rater (r = 0.99, κ = 0.89) |

||||||

| Civantos Fuentes27 | Detect areas of improvement in simulation setting | ✓ | ✓ | 11 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓30 | ||||||

| Drost-de Klerck29 | Evaluate performance regarding skills and competences during and after course | ✓ | ✓ | 22 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓inter-rater T1, T2, T3 (ρ = 0.81, 0.61, 0.83) | |||||||

| Falcone30 | Evaluate effectiveness of multidisciplinary trauma team training | ✓ | ✓ | 18 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓36 | ✓ | |||||

| Gala31 | Describe current performance of primary survey | ✓ | ✓ | 11 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓71 | ✓ | ||||||

| Gillman32 | Course evaluation | ✓ | ✓ | 14 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ATLS | ||||||

| Glanville33 | Evaluate the effectiveness of a learning program | ✓ | ✓ | 19 | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||

| Gyedu34 | Determine the achievement of key performance indicators during the initial assessment and management | ✓ | ✓ | 18 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓WHO | ✓ | |||||

| Holcomb36 | Validate advanced simulation as an evaluation tool for trauma team resuscitation skills | ✓ | ✓ | 26 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||

| Hulfish38 | Determine if cognitive aid checklist reduces omissions and speeds assessment time | ✓ | ✓ | 14 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓69 | ||||||

| Hultin39 | Assess interrater reliability | ✓ | ✓ | 10 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓36 | ✓inter-rater (ICCs = 0.55 and 0.83) | |||||

| Hunt65 | Characterize quality of resuscitation efforts and identify problem areas for educational interventions | ✓ | ✓ | 16 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓PALS, ATLS, TNCC | ✓inter-rater (ICC=0.77, 95% CI+ 0.74–0.79) | ✓ | ||||

| Innocenti40 | Evaluate effectiveness of training program | ✓ | ✓ | 23 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓Emergency Medicine Manual Oxford | |||||||

| Jonsson41 | Evaluate situational awareness training program on performance | ✓ | ✓ | 10 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓39 | ✓39 | ||||||

| Kelleher43 | Evaluate the effect of checklist on completion and timeliness of ATLS tasks | ✓ | ✓ | 16 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓69 | |||||||

| Kelleher44 | Evaluate effect checklist on deviations | ✓ | ✓ | 6 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ATLS | |||||||

| Kelleher45 | Analyse impact of team size on resuscitation task completion | ✓ | ✓ | 24 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓26 | |||||||

| Kliem47 | Investigate adherence | ✓ | ✓ | 12 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓inter-rater (κ = 0.94) |

|||||||

| Koko48 | Investigate adherence | ✓ | ✓ | 17 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓5 | |||||||

| Linders4 | Investigate adherence between video-based instruction versus conventional lecture | ✓ | ✓ | 24 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓APLS | ✓intra-rater (ICC=0.87, 95% CI 0.74–0.94) | ||||||

| Lubbert66 | Analyse team functioning and protocol deviations | ✓ | ✓ | 26 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ATLS | ||||||

| Maluso51 | Determine the optimal number of team members in the initial evaluation | ✓ | ✓ | 20 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ATLS | ||||||

| Merriman67 | Compare the use of teaching in clinical simulation or classroom | ✓ | ✓ | 21 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ALERT & ERC | |||||||

| Nadel52 | Evaluate effectiveness of an educational intervention on knowledge, technical skills and confidence | ✓ | ✓ | 5 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓PALS | |||||||

| O’Connell53 | Evaluate effect of family presence on ATLS task performance | ✓ | ✓ | 7 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓26 | ✓26 | ||||||

| Oakley68 | Determine the ability of video review to identify management errors | ✓ | ✓ | 12 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ATLS | ✓⁰ | ||||||

| Olgers5 | Study completeness | ✓ | ✓ | 26 | ✓ | |||||||||

| Parsons69 | Test checklist effectiveness | ✓ | ✓ | 15 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓26 | ✓ | |||||

| Peran54 | Validate cognitive aid tool | ✓ | ✓ | 36 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓⁰ | ✓ | ||||||

| Pringle55 | Assess effectiveness of a trauma course | ✓ | ✓ | 11 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||

| Ritchie57 | Assess utility of video review in assessing trauma team performance | ✓ | ✓ | 20 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓72 | ||||||

| Spanjers- Berg59 |

Analyse protocol compliance | ✓ | ✓ | 29 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||

| Stayt70 | Compare the use of teaching in clinical simulation or classroom | ✓ | ✓ | 21 | ✓ | ✓67 | ||||||||

| Tsang61 | Assess protocol compliance | ✓ | ✓ | 11 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ATLS | |||||||

| Wurster62 | Evaluate competency of assessment physician | ✓ | ✓ | 14 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓inter-rater (κ = 0.84, 95% CI 0.79–0.90) |

✓ | ||||||

| Yan63 | Investigate the impact of rapid cycle deliberate practice on skill retention | ✓ | ✓ | 8 | ✓ | ✓31 | ||||||||

*ICC: Intraclass Correlation Coefficient, κ: Kappa, r: Pearson’s correlation coefficient, ρ: Spearman’s Rho. +95%-CI: 95% Confidence Interval was only provided if reported in the study.

⁰The study indicated that interrater was performed, but results were not reported.

Forty-three studies reported about adherence to the ABCDE approach, 22 in simulation setting, 21 in clinical practice (Table 1). The number of ABCDE assessments per study varied from 10 to 437.

Simulation setting

Overall adherence varied from 29% to 35% pre-intervention29, 70 and from 65% to 97% post-intervention (simulation training or course).29, 55 The frequency with which specific ABCDE items were assessed, varied from 80% for assessment of airway and breathing to 20% for stabilization of the cervical spine in trauma setting.65 Pulse oximetry and blood pressure measurement were performed in all simulations (100%), in contrast to pupillary examination (31%) and Glasgow Coma Scale (5%).27 Two studies investigated adherence for the separate domains (A, B, C, D, and E).4, 47 The highest and lowest adherence was measured in domain A (100%) and E (0%), respectively. Several studies reported influencing factors: the use of a cognitive aid tool54 or a handheld checklist resulted in higher adherence.38, 69 The type of healthcare professional might also impact adherence: physicians scored higher than nurses.4 Simulation training programs resulted in improved adherence both directly after the course and in the longer term (4 months to two years later) in some,29, 40 but not in all studies.64 According to three studies, teaching method influenced adherence.4, 67, 70 Virtual reality can be used as instruction method to teach students the ABCDE approach in the right order.21, 22

Time to completion of the ABCDE approach varied from within two minutes38, 52, 55 up to six minutes.27, 36, 54 The use of a cognitive aid tool or checklist did not influence assessment time.38, 54

Clinical practice

In clinical studies, overall adherence towards the ABCDE approach ranged from 18% to 84%.5, 25 One study showed that the ABCDE approach was used in the minority (33%) of unstable patients and in only 3% of presumably stable patients in the emergency department.5 The frequency with which specific ABCDE items were assessed by participants varied widely, for example: airway patency from 76% to 100%, respiratory rate from 7% to 100%, and measurement of temperature from 0% to 100%.5, 17, 26, 33, 43, 59, 61, 62 One study showed that incomplete adherence involved basic ABCDE assessment principles such as omission of chest auscultation (44%) and central capillary refill time assessment (66%).68 Higher adherence was observed in the presence of an identified team leader35, 51, 61; lower adherence with increased injury severity.25 The number of team members influenced adherence, with an optimum of seven team members.45, 51 The use of a checklist,24 training in situational awareness,41 nor family presence53 influenced adherence, neither did speciality.25 Reported reasons for not applying the ABCDE approach were that clinical impression, vital signs or reason for visiting the emergency department did not indicate instability of the patient.5

Time to start the ABCDE approach after patient arrival to the emergency department varied from two minutes to 57 min and was significantly decreased by increasing triage code.5, 24 Time to complete the ABCDE approach varied from within 2 min to more than 30 min.5, 17, 26, 31, 35, 53, 57, 59, 60, 63, 66 Time needed to assess all domains of the ABCDE approach depended on the condition of the patient (e.g. injury severity)51 and the number of therapeutic interventions performed.31 The use of a handheld checklist increased the speed of the assessment of vital signs, resulting in a faster completion of the ABCDE approach.43

-

3)

Other outcomes

-

a.

Professional outcomes

In 18 studies professional outcomes, such as knowledge and confidence were reported (simulation setting (n = 15), clinical practice (n = 3) (Table 1)).

Simulation setting

Attending a simulation course increased participants’ confidence in adequately assessing critically ill patients.18, 19, 28, 36, 37, 52 There was no correlation between self-reported confidence or self-efficacy and ABCDE performance.67, 70 The use of a displayed primary survey checklist resulted in a slight (not significant) increase in mental demand and effort in team leaders compared to no checklist.38 An interdisciplinary paediatric trauma simulation program resulted in improved overall assessment scores including teamwork.64

Clinical practice

Scores on a theoretical knowledge test of the ABCDE approach varied among healthcare professionals (mean test scores: 80.1%, SD 12.2 and 52.9%, SD 12.2).16, 58 Type of department, profession category and age significantly influenced test scores. Nurses reported they felt most confident in the assessment and management of the circulation (88.2%) compared to airway (58.8%) and breathing (40.5%).56 The application of the ABCDE approach facilitated determination of a diagnosis and enhancing the decision to administer oxygen or intravenous fluids.19

-

b.

Team outcomes

Reported team outcomes concerned communication, leadership and teamwork.17, 23, 35, 42, 51, 57, 61, 64, 66 While applying the ABCDE approach, understandable communication (i.e. clear questions or instructions) between team members varied from 6% to 70%.23 Errors in team organization (unclear or inefficient team leader, unorganized resuscitation, not working according to protocol, and discontinuous supervision of the patient) led to significantly more deviations from the primary survey than when team organization was clearly defined.66 A paediatric trauma simulation program resulted in improved scores for teamwork.64

-

c.

Patient outcomes

Only two studies reported patient outcomes. One study showed that patients with a higher, although not significant, mean adherence to the ABCDE had shorter length of stay at the emergency department.62 The other presented that healthcare professionals scoring higher in ABCDE adherence ordered fewer CT scans, with no difference in patient mortality.25

Discussion

This review identified 57 studies that reported assessment, adherence, and other outcomes related to application of the ABCDE approach in clinical practice and simulation setting. To our knowledge, this is the first literature review focusing on the ABCDE approach. Reviews about Advanced Life Support (ALS) guidelines and Advanced Trauma Life Support (ATLS) courses exist, but did not describe outcomes related to the ABCDE approach nor the primary survey specifically.73, 74, 75

-

1)

ABCDE assessment tools

A reason for the large variation in content of ABCDE assessment tools might be that the assessment tools were developed with various goals. Some tools focused on details on the content of and adherence to the ABCDE approach. Other tools were developed to study the ABCDE approach in a broader perspective, for example, to answer research questions about team outcomes and education. Therefore, studies might have chosen a limited number of items in their assessment tool for practical reasons (e.g. to ease scoring). Another potential explanation might be that interprofessional disagreement exists about the most important ABCDE items. Moreover, several tools included the action items following the ABCDE assessment in their assessment tools (Table 2). These action items might have different functions, for example, ‘consider ordering blood’ was designed to test higher level decision making.69 While the ABCDE approach itself is strictly a structured method to assess a patient, it should be linked to clinical decision-making including appropriate management, i.e. actions, in order to improve a patient’s condition.

-

2)

Adherence to the ABCDE approach

A wide variation in adherence is evident. Considering the variation in content of assessment tools, but also in context, setting and participants, fair comparison is not possible and the actual performance of professionals with regards to the ABCDE remains largely unknown. However, most studies showed suboptimal adherence. In this review, we identified factors influencing adherence which might reveal opportunities for improvement in every department treating (potentially) critically ill patients. For example, to assign a team leader in your daily team and to regularly attend simulation training can already lead to increased adherence.35, 51, 61 Nurses scored low on adherence and knowledge, suggesting a tailored approach to benefit these healthcare professionals.4, 16, 58 Thereby, as with all skills, practice is the key for retention of skills. For the ABCDE approach itself this has not been investigated yet, but it is known that ALS knowledge and skills decay by six months to one year after training and that skills decay faster than knowledge.73 The ABCDE approach is a quick and simple, however valuable tool as one assessment enables healthcare professionals to collect relevant information about the current condition of the patient, and repeated assessments provide trend monitoring to prioritize the associated treatment. Performing only a first clinical impression or collecting some vital signs without a structure, might risk missing a critically ill patient or a significant deterioration. Although adherence indicates how precise the ABCDE algorithm is performed, in a real patient the actions following the assessment are as important. A patient will not improve as a result of perfect adherence per se, but hopefully as a result of the actions based on the assessment. Even though some studies included actions in their assessment tools, no study investigated the associated actions separately.

-

3)

Outcomes

It is remarkable that only two studies in this review reported the ABCDE approach in association with patient outcomes.25, 62 Two other studies were interested in patient outcomes, but could not report results as result of underpowering and lack of relevant outcomes in the studies.24, 59 For the ATLS, of which the primary survey, and thus the ABCDE approach is an important element, it is also known that evidence confirming reduction of morbidity or mortality is still lacking.74, 75 If the goal of the ABCDE approach is to identify potentially life-threatening conditions followed by lifesaving actions, failure to complete the ABCDE approach in a complete and efficient manner might influence patient outcomes. Setting up a randomized controlled trial comparing the ABCDE approach versus no structured approach in the assessment of a real patient is not possible given the wide adoption of the ABCDE approach. Therefore, detailed study of adherence, the factors influencing this adherence and the association of this adherence to clinical outcomes might shed light on this hitherto largely unexplored area.

Strengths and limitations

This scoping review, performed in concordance with the JBI guidelines, is an important and new contribution to the existing knowledge about the ABCDE approach as it identified research regarding the approach and its outcomes. Strengths are the use of a broad search strategy in multiple databases and the structured scoping approach including two researchers independently performing study selection and data extraction. Foremost, the heterogeneity of the included studies stands out as it limits comparison of the results.

Knowledge gaps and implications

Based on this scoping review, the following knowledge gaps were identified:

-

•

No uniformity in reported assessment tools. Standardization of the assessment tools, along with appropriate validation evidence, is needed. A universal ABCDE approach and subsequently a universal assessment tool could be part of that process.

-

•

Effectiveness of application remains unknown. Randomized controlled trials comparing the ABCDE approach to no structure do not exist and data on patient outcomes were scarce. Reported adherence varied widely and was measured inconsistently. Although perfect adherence does not necessarily guarantee improvement of patient outcomes, decision making and calling for appropriate actions following the ABCDE assessment might be related to this adherence. As such, uniformity and clarity in reporting on the ABCDE approach and its assessment is needed as a first step towards potential improvement of patient outcomes. A consensus-based core outcome set (COS) should be developed, consisting of outcome measures which are easy to use, demonstrate suitable measurement properties to evaluate application of the ABCDE approach, facilitating comparison.76, 77 For future researchers publishing about the ABCDE approach, we recommend providing detailed information about the assessment tools and outcome measurements used.

-

•

Teaching and implementation underexplored. There is a lack of understanding regarding teaching methods to improve application and, in particular, adherence in clinical care. However, a reliable and valid assessment tool is needed to further investigate this. Teaching is mainly focused on simulation training, but learning should be continued afterwards in daily clinical care. Therefore, workplace learning is essential to continue the learning process and thereby improving implementation and adherence.

Conclusion

This scoping review showed that a large variety of ABCDE assessment tools exists. Adherence varied widely among included studies. The effects of the ABCDE approach on patient outcomes are yet to be established.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Laura J. Bruinink: Writing – original draft, Methodology, Investigation, Formal analysis. Marjolein Linders: Writing – original draft, Methodology, Investigation, Formal analysis, Conceptualization. Willem P. de Boode: Writing – review & editing, Conceptualization. Cornelia R.M.G. Fluit: Writing – review & editing. Marije Hogeveen: Writing – review & editing, Supervision, Methodology, Conceptualization.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Alice Tillema for the support in the development of the search strategy.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Footnotes

-

A.The PRISMA-ScR Checklist.

-

B.Search strategy in PubMed.

-

C.Studies excluded following full-text review.

-

D.Data extraction instrument.

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resplu.2024.100763.

Contributor Information

Laura J. Bruinink, Email: laura.bruinink@radboudumc.nl.

Marjolein Linders, Email: marjolein.linders@radboudumc.nl.

Willem P. de Boode, Email: willem.deboode@radboudumc.nl.

Cornelia R.M.G. Fluit, Email: lia.fluit@radboudumc.nl.

Marije Hogeveen, Email: marije.hogeveen@radboudumc.nl.

Appendix B. Supplementary material

The following are the Supplementary data to this article:

References

- 1.Thim T., Krarup N.H.V., Grove E.L., Rohde C.V., Løfgren B. Initial assessment and treatment with the Airway, Breathing, Circulation, Disability, Exposure (ABCDE) approach. Int J Gen Med. 2012;5:117–121. doi: 10.2147/IJGM.S28478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schipper I.B., Schep N. ATLS - a pioneer in trauma education; history and effects. Ned Tijdschr Geneeskd. 2017;161:D1569. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hannon M.M., Middelberg L.K., Lee L.K. The initial approach to the multisystem pediatric trauma patient. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2022;38:290–298. doi: 10.1097/pec.0000000000002722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Linders M., Binkhorst M., Draaisma J.M.T., van Heijst A.F.J., Hogeveen M. Adherence to the ABCDE approach in relation to the method of instruction: a randomized controlled simulation study. BMC Emerg Med. 2021;21:121. doi: 10.1186/s12873-021-00509-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Olgers T.J., Dijkstra R.S., Drost-de Klerck A.M., Ter Maaten J.C. The ABCDE primary assessment in the emergency department in medically ill patients: an observational pilot study. Neth J Med. 2017;75:106–111. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Perkins G.D., Graesner J.T., Semeraro F., et al. European Resuscitation Council Guidelines 2021: Executive summary. Resuscitation. 2021;161:1–60. doi: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2021.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Turner N.M., Kieboom J., Nusmeier A. 6th edition. Bohn Stafleu van Loghum; Houten: 2022. Advanced Paediatric Life Support - de Nederlandse editie. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Henry S. 10th Edition. American College of Surgeons; Chicago: 2018. ATLS Advanced Trauma Life Support Student Course Manual. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Resucitation Council (UK). Information about using the Airway, Breathing, Circulation, Disability, Exposure (ABCDE) approach to assess and treat patients. Resuscitation Council (UK), 2021. (Accessed 28 June 2024, at https://www.resus.org.uk/resuscitation-guidelines/abcde-approach/).

- 10.Peters MDJ, Godfrey C, McInerney P, et al. Scoping Reviews (2020). Aromataris E, Lockwood C, Porritt K, Pilla B, Jordan Z, editors. JBI Manual for Evidence Synthesis. JBI; 2024. https://synthesismanual.jbi.global. 10.46658/JBIMES-24-09. [DOI]

- 11.Munn Z., Peters M.D.J., Stern C., Tufanaru C., McArthur A., Aromataris E. Systematic review or scoping review? Guidance for authors when choosing between a systematic or scoping review approach. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2018;18:143. doi: 10.1186/s12874-018-0611-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Peters M.D.J., Marnie C., Tricco A.C., et al. Updated methodological guidance for the conduct of scoping reviews. JBI Evid Synth. 2020;18:2119–2126. doi: 10.11124/jbies-20-00167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tricco A.C., Lillie E., Zarin W., et al. PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and Explanation. Ann Intern Med. 2018;169:467–473. doi: 10.7326/m18-0850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Peters M.D.J., Godfrey C., McInerney P., et al. Best practice guidance and reporting items for the development of scoping review protocols. JBI Evid Synth. 2022;20:953–968. doi: 10.11124/jbies-21-00242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Linders M, Bruinink L, Fluit L, de Boode W, Hogeveen M. The ABCDE approach in critically ill or injured patients: a scoping review of quantitative and qualitative evidence; 2021. 10.31219/osf.io/psdt8. [DOI]

- 16.Althobity T.A., Jawhari A.M., Almalki M.G., et al. Healthcare professional's knowledge of the systemic ABCDE approach: a cross-sectional study. Cureus. 2024;16:e51464. doi: 10.7759/cureus.51464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Aukstakalnis V., Dambrauskas Z., Stasaitis K., et al. What happens in the shock room stays in the shock room? A time-based audio/video audit framework for trauma team performance analysis. Eur J Emerg Med. 2020;27:121–124. doi: 10.1097/MEJ.0000000000000627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Barnes J., Paterson-Brown L. Improving care of critically unwell patients through development of a simulation programme in a malawian hospital. Journal of Education and Training Studies. 2017;5 doi: 10.11114/jets.v5i6.2366. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Benito J., Luaces-Cubells C., Mintegi S., et al. Evaluation and Impact of the “Advanced Pediatric Life Support” Course in the Care of Pediatric Emergencies in Spain. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2018;34:628–632. doi: 10.1097/pec.0000000000001038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Berg H., Båtnes R., Steinsbekk A. Changes in performance during repeated in-situ simulations with different cases. BMJ Simul Technol Enhanc Learn. 2021;7:75–80. doi: 10.1136/bmjstel-2019-000527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Berg H., Steinsbekk A. The effect of self-practicing systematic clinical observations in a multiplayer, immersive, interactive virtual reality application versus physical equipment: a randomized controlled trial. Adv Health Sci Educ Theory Pract. 2021;26:667–682. doi: 10.1007/s10459-020-10019-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Berg H., Steinsbekk A. Is individual practice in an immersive and interactive virtual reality application non-inferior to practicing with traditional equipment in learning systematic clinical observation? A randomized controlled trial. BMC Med Educ. 2020;20:123. doi: 10.1186/s12909-020-02030-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bergs E.A., Rutten F.L., Tadros T., Krijnen P., Schipper I.B. Communication during trauma resuscitation: do we know what is happening? Injury. 2005;36:905–911. doi: 10.1016/j.injury.2004.12.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Botelho F., Truché P., Caddell L., et al. Implementation of a checklist to improve pediatric trauma assessment quality in a Brazilian hospital. Pediatr Surg Int. 2021;37:1339–1348. doi: 10.1007/s00383-021-04941-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Botelho F., Truche P., Mooney D.P., et al. Pediatric trauma primary survey performance among surgical and non-surgical pediatric providers in a Brazilian trauma center. Trauma Surg Acute Care Open. 2020;5:e000451. doi: 10.1136/tsaco-2020-000451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Carter E.A., Waterhouse L.J., Kovler M.L., Fritzeen J., Burd R.S. Adherence to ATLS primary and secondary surveys during pediatric trauma resuscitation. Resuscitation. 2013;84:66–71. doi: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2011.10.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Civantos Fuentes E., Rodriguez Nunez A., Iglesias Vazquez J.A., Sanchez S.L. Assessment of primary care paediatricians performance in a paediatric trauma simulation. An Pediatr (Barc) 2012;77:203–207. doi: 10.1016/j.anpedi.2012.01.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dickerson-Young T., Keilman A., Yoshida H., Jones M., Cross N., Thomas A. Pediatric emergency medicine disaster simulation curriculum: the 5-minute trauma assessment for pediatric residents (TRAP-5) MedEdPORTAL. 2020;16:10940. doi: 10.15766/mep_2374-8265.10940. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Drost-de Klerck A.M., Olgers T.J., van de Meeberg E.K., Schonrock-Adema J., Ter Maaten J.C. Use of simulation training to teach the ABCDE primary assessment: an observational study in a Dutch University Hospital with a 3–4 months follow-up. BMJ Open. 2020;10 doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2019-032023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Falcone R.A., Jr., Daugherty M., Schweer L., Patterson M., Brown R.L., Garcia V.F. Multidisciplinary pediatric trauma team training using high-fidelity trauma simulation. J Pediatr Surg. 2008;43:1065–1071. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2008.02.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gala P.K., Osterhoudt K., Myers S.R., Colella M., Donoghue A. Performance in trauma resuscitation at an urban tertiary level I pediatric trauma center. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2016;32:756–762. doi: 10.1097/pec.0000000000000942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gillman L.M., Brindley P., Paton-Gay J.D., et al. Simulated trauma and resuscitation team training course-evolution of a multidisciplinary trauma crisis resource management simulation course. Am J Surg. 2016;212(188–193):e3. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2015.07.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Glanville D., Kiddell J., Lau R., Hutchinson A., Botti M. Evaluation of the effectiveness of an eLearning program in the nursing observation and assessment of acute surgical patients: A naturalistic observational study. Nurse Educ Pract. 2021;55 doi: 10.1016/j.nepr.2021.103152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gyedu A., Quainoo E., Nakua E., Donkor P., Mock C. Achievement of key performance indicators in initial assessment and care of injured patients in ghanaian non-tertiary hospitals: an observational study. World J Surg. 2022;46:1288–1299. doi: 10.1007/s00268-022-06507-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hoff W.S., Reilly P.M., Rotondo M.F., DiGiacomo J.C., Schwab C.W. The importance of the command-physician in trauma resuscitation. J Trauma. 1997;43:772–777. doi: 10.1097/00005373-199711000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Holcomb J.B., Dumire R.D., Crommett J.W., et al. Evaluation of trauma team performance using an advanced human patient simulator for resuscitation training. J Trauma. 2002;52:1078–1085. doi: 10.1097/00005373-200206000-00009. discussion 1085-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Holland J.R., Latuska R.F., MacKeil-White K., Ciener D.A., Vukovic A.A. “Sim one, do one, teach one”: a simulation-based trauma orientation for pediatric residents in the emergency department. Pediatric Emergency Care. 2021;37:e1285–e1289. doi: 10.1097/PEC.0000000000002003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hulfish E., Diaz M.C.G., Feick M., Messina C., Stryjewski G. The impact of a displayed checklist on simulated pediatric trauma resuscitations. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2021;37:23–28. doi: 10.1097/pec.0000000000001439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hultin M., Jonsson K., Härgestam M., Lindkvist M., Brulin C. Reliability of instruments that measure situation awareness, team performance and task performance in a simulation setting with medical students. BMJ Open. 2019;9 doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2019-029412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Innocenti F., Tassinari I., Ralli M.L., et al. Improving technical and non-technical skills of emergency medicine residents through a program based on high-fidelity simulation. Intern Emerg Med. 2022;17:1471–1480. doi: 10.1007/s11739-022-02940-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Jonsson K., Brulin C., Härgestam M., Lindkvist M., Hultin M. Do team and task performance improve after training situation awareness? A randomized controlled study of interprofessional intensive care teams. Scand J Trauma Resusc Emerg Med. 2021;29:73. doi: 10.1186/s13049-021-00878-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Jonsson K., Hultin M., Härgestam M., Lindkvist M., Brulin C. Factors influencing team and task performance in intensive care teams in a simulated scenario. Simul Healthc. 2021;16:29–36. doi: 10.1097/sih.0000000000000462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kelleher D.C., Carter E.A., Waterhouse L.J., Parsons S.E., Fritzeen J.L., Burd R.S. Effect of a checklist on advanced trauma life support task performance during pediatric trauma resuscitation. Acad Emerg Med. 2014;21:1129–1134. doi: 10.1111/acem.12487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kelleher D.C., Jagadeesh Chandra Bose R.P., Waterhouse L.J., Carter E.A., Burd R.S. Effect of a checklist on advanced trauma life support workflow deviations during trauma resuscitations without pre-arrival notification. J Am Coll Surg. 2014;218:459–466. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2013.11.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kelleher D.C., Kovler M.L., Waterhouse L.J., Carter E.A., Burd R.S. Factors affecting team size and task performance in pediatric trauma resuscitation. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2014;30:248–253. doi: 10.1097/pec.0000000000000106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kiessling A., Amiri C., Arhammar J., et al. Interprofessional simulation-based team-training and self-efficacy in emergency medicine situations. J Interprof Care. 2022;36:873–881. doi: 10.1080/13561820.2022.2038103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kliem P.S.C., Tisljar K., Baumann S.M., et al. First-response ABCDE management of status epilepticus: a prospective high-fidelity simulation study. J Clin Med. 2022:11. doi: 10.3390/jcm11020435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Koko J.A.B., Mohamed O.S.A., Koko B.A.B., Musa O.A.Y. The ABCDE approach: Evaluation of adherence in a low-income country. Injury. 2023: doi: 10.1016/j.injury.2023.111268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Long A.M., Lefebvre C.M., Masneri D.A., et al. The golden opportunity: multidisciplinary simulation training improves trauma team efficiency. J Surg Educ. 2019;76:1116–1121. doi: 10.1016/j.jsurg.2019.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Macnamara A.F., Bird K., Rigby A., Sathyapalan T., Hepburn D. High-fidelity simulation and virtual reality: an evaluation of medical students' experiences. BMJ Simul Technol Enhanc Learn. 2021;7:528–535. doi: 10.1136/bmjstel-2020-000625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Maluso P., Hernandez M., Amdur R.L., Collins L., Schroeder M.E., Sarani B. Trauma team size and task performance in adult trauma resuscitations. J Surg Res. 2016;204:176–182. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2016.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Nadel F.M., Lavelle J.M., Fein J.A., Giardino A.P., Decker J.M., Durbin D.R. Teaching resuscitation to pediatric residents: the effects of an intervention. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2000;154:1049–1054. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.154.10.1049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.O'Connell K.J., Carter E.A., Fritzeen J.L., Waterhouse L.J., Burd R.S. Effect of family presence on advanced trauma life support task performance during pediatric trauma team evaluation. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2021;37:e905–e909. doi: 10.1097/pec.0000000000001164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Peran D., Kodet J., Pekara J., et al. ABCDE cognitive aid tool in patient assessment - development and validation in a multicenter pilot simulation study. BMC Emerg Med. 2020;20:95. doi: 10.1186/s12873-020-00390-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Pringle K., Mackey J.M., Modi P., et al. A short trauma course for physicians in a resource-limited setting: Is low-cost simulation effective? Injury. 2015;46:1796–1800. doi: 10.1016/j.injury.2015.05.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Renning K., van de Water B., Brandstetter S., et al. Training needs assessment for practicing pediatric critical care nurses in Malawi to inform the development of a specialized master's education pathway: a cohort study. BMC Nurs. 2022;21:6. doi: 10.1186/s12912-021-00772-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Ritchie P.D., Cameron P.A. An evaluation of trauma team leader performance by video recording. Aust N Z J Surg. 1999;69:183–186. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1622.1999.01519.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Schoeber N.H.C., Linders M., Binkhorst M., et al. Healthcare professionals' knowledge of the systematic ABCDE approach: a cross-sectional study. BMC Emerg Med. 2022;22:202. doi: 10.1186/s12873-022-00753-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Spanjersberg W.R., Bergs E.A., Mushkudiani N., Klimek M., Schipper I.B. Protocol compliance and time management in blunt trauma resuscitation. Emerg Med J. 2009;26:23–27. doi: 10.1136/emj.2008.058073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Taylor M.A., 2nd, Hewes H.A., Bolinger C.D., Fenton S.J., Russell K.W. Established time goals can increase the efficiency of trauma resuscitation. Cureus. 2020;12 doi: 10.7759/cureus.9524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Tsang B., McKee J., Engels P.T., Paton-Gay D., Widder S.L. Compliance to advanced trauma life support protocols in adult trauma patients in the acute setting. World J Emerg Surg. 2013;8:39. doi: 10.1186/1749-7922-8-39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Wurster L.A., Thakkar R.K., Haley K.J., et al. Standardizing the initial resuscitation of the trauma patient with the Primary Assessment Completion Tool using video review. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2017;82:1002–1006. doi: 10.1097/ta.0000000000001417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Yan D.H., Slidell M.B., McQueen A. Rapid cycle deliberate practice simulation curriculum improves pediatric trauma performance: a prospective cohort study. Simul Healthc. 2021;16:94–99. doi: 10.1097/sih.0000000000000524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Auerbach M., Roney L., Aysseh A., et al. In situ pediatric trauma simulation: assessing the impact and feasibility of an interdisciplinary pediatric in situ trauma care quality improvement simulation program. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2014;30:884–891. doi: 10.1097/pec.0000000000000297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Hunt E.A., Hohenhaus S.M., Luo X., Frush K.S. Simulation of pediatric trauma stabilization in 35 North Carolina emergency departments: identification of targets for performance improvement. Pediatrics. 2006;117:641–648. doi: 10.1542/peds.2004-2702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Lubbert P.H., Kaasschieter E.G., Hoorntje L.E., Leenen L.P. Video registration of trauma team performance in the emergency department: the results of a 2-year analysis in a Level 1 trauma center. J Trauma. 2009;67:1412–1420. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e31818d0e43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Merriman C.D., Stayt L.C., Ricketts B. Comparing the effectiveness of clinical simulation versus didactic methods to teach undergraduate adult nursing students to recognize and assess the deteriorating patient. Clinical Simulation in Nursing. 2014;10:e119–e127. doi: 10.1016/j.ecns.2013.09.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Oakley E., Stocker S., Staubli G., Young S. Using video recording to identify management errors in pediatric trauma resuscitation. Pediatrics. 2006;117:658–664. doi: 10.1542/peds.2004-1803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Parsons S.E., Carter E.A., Waterhouse L.J., et al. Improving ATLS performance in simulated pediatric trauma resuscitation using a checklist. Ann Surg. 2014;259:807–813. doi: 10.1097/sla.0000000000000259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Stayt L.C., Merriman C., Ricketts B., Morton S., Simpson T. Recognizing and managing a deteriorating patient: a randomized controlled trial investigating the effectiveness of clinical simulation in improving clinical performance in undergraduate nursing students. J Adv Nurs. 2015;71:2563–2574. doi: 10.1111/jan.12722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Donoghue A., Nishisaki A., Sutton R., Hales R., Boulet J. Reliability and validity of a scoring instrument for clinical performance during Pediatric Advanced Life Support simulation scenarios. Resuscitation. 2010;81:331–336. doi: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2009.11.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Sugrue M., Seger M., Kerridge R., Sloane D., Deane S. A prospective study of the performance of the trauma team leader. J Trauma. 1995;38:79–82. doi: 10.1097/00005373-199501000-00021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Yang C.W., Yen Z.S., McGowan J.E., et al. A systematic review of retention of adult advanced life support knowledge and skills in healthcare providers. Resuscitation. 2012;83:1055–1060. doi: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2012.02.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Mohammad A., Branicki F., Abu-Zidan F.M. Educational and clinical impact of Advanced Trauma Life Support (ATLS) courses: a systematic review. World J Surg. 2014;38:322–329. doi: 10.1007/s00268-013-2294-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Jayaraman S, Sethi D. Advanced trauma life support training for hospital staff. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2009(2):Cd004173. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD004173.pub3. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 76.Prinsen C.A.C., Vohra S., Rose M.R., et al. How to select outcome measurement instruments for outcomes included in a “Core Outcome Set” – a practical guideline. Trials. 2016;17:449. doi: 10.1186/s13063-016-1555-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Williamson P.R., Altman D.G., Blazeby J.M., et al. Developing core outcome sets for clinical trials: issues to consider. Trials. 2012;13:132. doi: 10.1186/1745-6215-13-132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.