Abstract

Background

The representativeness of cohort studies compared to nationwide data is a major concern. This study evaluated the similarity and seasonality of causative respiratory viruses for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) and asthma exacerbations between retrospective multicenter cohort study and nationwide data.

Methods

We compared data from the retrospective multicenter cohort study with Korean Influenza and Respiratory Surveillance System data between 2015 and 2018. Correlation, dynamic time warping (DTW), and seasonal autoregressive integrated moving average (SARIMA) analyses were performed.

Results

Spearman correlation coefficients [ρ] indicated very strong (respiratory syncytial virus [RSV] [ρ = 0.8458] and influenza virus [IFV] [ρ = 0.8272]), strong (human metapneumovirus [HMPV] [ρ = 0.7177] and parainfluenza virus [PIV] [ρ = 0.6742]), and moderate (rhinovirus [RV] [ρ = 0.5850] and human coronavirus [HCoV] [ρ = 0.5158]) correlations. DTW analyses showed moderate (PIV) and high (IFV, RSV, and HMPV) synchronicity between the two datasets, while RV and HCoV showed low synchronicity. SARIMA analyses revealed 12-month seasonality for IFV, RSV, PIV, and HMPV. The peak season was winter for RSV and IFV, spring to summer for PIV, and spring for HMPV.

Conclusions

This was the first study to report the synchronicity between a retrospective multicenter cohort study of viruses that can cause COPD or asthma exacerbations and nationwide surveillance system data.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12890-024-03298-x.

Keywords: Respiratory virus, Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, Asthma, Exacerbation, Causative agent, Cohort, Representativeness

Background

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) and asthma are both caused by chronic airway inflammation. COPD is characterized by irreversible respiratory symptoms and airflow obstruction, while asthma typically shows reversible symptoms [1–3]. These conditions pose substantial global health challenges, imposing significant socioeconomic burdens and contributing to morbidity rates worldwide [4, 5]. Exacerbations, defined as deterioration from a stable state, play a crucial role in their progression [4, 6].

In previous studies, respiratory viral infections are responsible for more than half of COPD exacerbations and 60–80% of asthma exacerbations [7, 8]. These infections often result in severe symptoms, hospitalizations, and extended recovery periods [7]. Several studies have investigated the causative pathogens of exacerbations, including research conducted in South Korea [9–12]. However, national representativeness of data is usually lacking due to selection bias from enrollment, limiting the generalizability of their findings.

The Korean Influenza and Respiratory Viruses Surveillance System (KINRESS), which operates under the Korean National Institute of Health (KNIH) and is affiliated with the Korean Disease Control and Prevention Agency (KDCA), collects virus samples from sentinel institutions and provides weekly reports to anticipate potential outbreaks [13]. While these data provide valuable epidemiological information on respiratory viruses in South Korea, they have limited ability to elucidate conditions exacerbated by these infections, such as COPD or asthma.

We aimed this study to reassess a multicenter retrospective cohort and expands the utilization of KINRESS data by validating the synchronicity between two datasets.

Methods

Data source and study population

Nationwide surveillance dataset

KINRESS is a sentinel surveillance system that has been reporting on a weekly basis since December 2005. Starting from July 2011, KINRESS has been monitoring eight major respiratory viruses, including adenovirus (AdV), human coronavirus (HCoV), rhinovirus (RV), respiratory syncytial virus (RSV), influenza virus (IFV), parainfluenza virus (PIV), human metapneumovirus (HMPV), and human bocavirus (HBoV), at 52 primary healthcare institutions for specimen collection and approximately 200 participating community-based healthcare institutions for data collection on patients requiring hospitalization due to acute respiratory infections across the country. Patients exhibiting typical symptoms of respiratory viral infections undergo real-time reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (PCR) or rapid antigen tests using naso- or oropharyngeal swabs within 3 days of symptom onset. Confirmed cases are then reported to 17 public health and environment research institutes. The data are reported weekly on the Infectious Disease Portal, which is operated by the KDCA. The data extracted for this study cover the period between January 2015 and December 2018.

Multicenter retrospective cohort data

A multicenter retrospective cohort study was conducted at 28 university hospitals in South Korea between January 2015 and December 2018. The definitions of COPD, asthma, and exacerbation were based on well-established guidelines, including the Global Initiative for Obstructive Lung Disease and Global Initiative for Asthma. Patients who met the following criteria underwent conventional testing for respiratory virus PCR, influenza PCR, or influenza rapid antigen tests to identify the causative pathogen. If the same patient experiences multiple exacerbation events, each event is considered separately if there is an interval of at least 30 days between the exacerbations. Patients who were prescribed any antibiotics within 4 weeks of enrollment for reasons other than exacerbation treatment were excluded [10, 12]. Ultimately, a total of 1314 patients were included in this study.

Definition of COPD

Aged ≥ 40 years with chronic respiratory symptoms.

Post-bronchodilator forced expiratory volume in 1 s/forced vital capacity < 0.7 more than 6 months ago.

Definition of Asthma

Aged ≥ 18 years with clinical symptoms consistent with asthma.

Asthma diagnosed more than 6 months ago.

Definition of Exacerbation

Acute condition with worsening of respiratory symptoms (e.g., cough, dyspnea, wheezing, and chest discomfort), which leads to treatment with antibiotics, systemic corticosteroids, or hospitalization. In case of asthma exacerbation, elevation of at least double the baseline dose of controlling inhaler were also included.

Statistical analyses

The positive cases refer to the reported number of virus cases during each period. For comparing the trend and similarity between the KINRESS data and the multicenter retrospective cohort dataset, normalization of the positive cases into a normalized incidence rate is required due to the differences between the two datasets. The data were normalized between 0 and 1 by using the highest number of confirmed cases in the given year as the denominator and the actual confirmed cases as the numerator before further analysis. AdV and HBoV were excluded from analyses because of the small sample size in the retrospective cohort. Spearman correlation coefficients were calculated for each virus due to its non-normally distribution (Supplementary Table 1).

Dynamic time warping (DTW)

The similarities in normalized time-series patterns of two datasets were assessed through dynamic time warping (DTW) using the R package “dtw.” DTW is a widely used technique for measuring similarity when there are differences in the lengths and time points of the compared time-series data. It identifies the best alignment by minimizing the cumulative distance between the corresponding elements in each sequence by a dynamic programming algorithm to explore all potential alignments. These statistics allow analysis of the similarity and identification of patterns or trends in the data. The standardized distance between the two alignments is transformed into a value ranging from 0 to 1, with values closer to 0 indicating greater similarity [14].

Seasonal autoregressive integrated moving average (SARIMA)

The periodicity of multicenter cohort study was assessed using the seasonal autoregressive integrated moving average (SARIMA) model [15]. SARIMA is a powerful method for examining the seasonality of time-series data. It relies on the concept of autocorrelation, which demonstrates the correlation between different time points. In this analysis, autocorrelation indicates a relationship between the values of previous months and the current or subsequent months. A value of 0 suggests no autocorrelation, while a higher value indicates that many past values are required for accurate prediction. Conversely, a lower value indicates underfitting. The details of the SARIMA results are presented in Supplementary Table 2. The R package “forecast” was used to perform the SARIMA analyses [16]. A P-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. All analyses were performed using R 3.6.3 and RStudio Team (2020) software (RStudio: Integrated Development for R. RStudio, PBC, Boston, MA, USA).

Results

Description of the datasets

A descriptive summary of the annual occurrence of six key respiratory viruses (RV, IFV, RSV, PIV, HCoV, and HMPV) between 2015 and 2018 in the two datasets is presented in Table 1. In the multicenter cohort dataset, six types of viruses included in this study were identified as causative agents in 31.8–39.7% of all exacerbation events. IFV was the most common, accounting for 12.5–15.6%, followed by RV at 8.1–10.4%. RSV (3.4–5.0%), PIV(2.2–4.6%), HCoV (1.6–4.0%), and HMPV (1.4–5.1%) were reported, and the order varied by year. Between 2015 and 2018, RV consistently had the highest number of reported cases in the KDCA data, followed by IFV and RSV.

Table 1.

Descriptive table of used datasets. Table 1 presents a summary of the annual occurrence of respiratory viruses between 2015 and 2018. While the KDCA table only reported the total number of positive cases, the table of multicenter cohort described both the number of positive cases and the proportion of total exacerbation events per year

| RV | IFV | RSV | PIV | HCoV | HMPV | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Multicenter cohort data | |||||||

| 2015 | 20 (9.2) | 34 (15.6) | 11 (5.0) | 7 (3.2) | 5 (2.3) | 3 (1.4) | 80 (36.7) |

| 2016 | 31 (10.4) | 45 (15.2) | 10 (3.4) | 7 (2.4) | 10 (3.4) | 15 (5.1) | 118 (39.7) |

| 2017 | 26 (8.1) | 40 (12.5) | 12 (3.7) | 7 (2.2) | 5 (1.6) | 12 (3.7) | 102 (31.8) |

| 2018 | 45 (9.4) | 61 (12.8) | 17 (3.6) | 22 (4.6) | 19 (4.0) | 16 (3.3) | 180 (37.7) |

| KDCA data | |||||||

| 2015 | 15,453 | 5739 | 8736 | 5846 | 1495 | 3040 | 40,309 |

| 2016 | 18,993 | 10,462 | 13,606 | 7035 | 5083 | 4338 | 59,517 |

| 2017 | 21,467 | 8723 | 14,450 | 7971 | 3825 | 4388 | 60,824 |

| 2018 | 25,896 | 23,583 | 16,227 | 10,586 | 7084 | 7052 | 90,428 |

RV rhinovirus, HCoV human coronavirus, RSV respiratory syncytial virus, IFV influenza virus, PIV parainfluenza virus, HMPV human metapneumovirus, KDCA Korean Disease Control and Prevention Agency

Spearman correlation analyses

Spearman correlation coefficients (Spearman rho, ρ) varied across viruses and years (Table 2). Overall, we found strong correlations when matching the year and virus type (mean ρ = 0.6943). RSV (mean ρ = 0.8458) and IFV (mean ρ = 0.8272) had very strong correlations, while HMPV (mean ρ = 0.7177) and PIV (mean ρ = 0.6742) had strong correlations. Meanwhile, RV (mean ρ = 0.5850) and HCoV (mean ρ = 0.5158) showed moderate correlations. When considering the data on a yearly basis, a robust correlation was observed (mean ρ = 0.6943), with the 2018 data showing a particularly strong correlation (mean ρ = 0.8110).

Table 2.

Spearman correlation coefficients of respiratory viruses from two datasets. Strong correlations of RSV, IFV, HMPV, and PIV were found. Overall data showed a robust correlation

| Spearman (ρ) | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| RV | 0.3075 | 0.4622 | 0.7589 | 0.8115 |

| IFV | 0.7012 | 0.9386 | 0.8461 | 0.8230 |

| HCoV | 0.6783 | 0.5745 | -0.0411 | 0.8514 |

| RSV | 0.8713 | 0.7204 | 0.9103 | 0.8810 |

| PIV | 0.7700 | 0.6782 | 0.4570 | 0.7915 |

| HMPV | 0.6400 | 0.7807 | 0.7428 | 0.7073 |

RV rhinovirus, HCoV human coronavirus, RSV respiratory syncytial virus, IFV influenza virus, PIV parainfluenza virus, HMPV human metapneumovirus

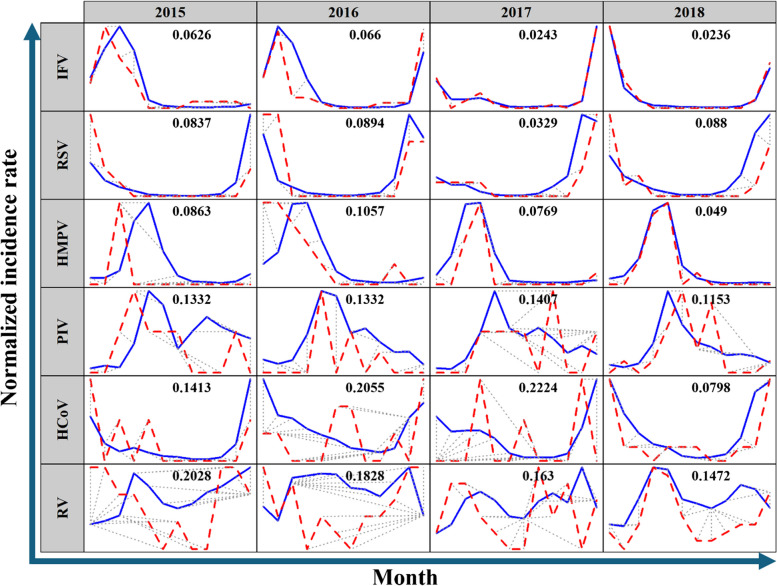

Annual virus prevalence

Figure 1 provides a summary of the distances (D) obtained from the DTW analysis, indicating the degree of synchronicity between the two datasets. IFV (D = 0.0236–0.0660), RSV (D = 0.0329–0.0894), and HMPV (D = 0.0490–0.1057) demonstrated high synchronicity, while PIV showed moderate synchronicity. However, RV (D = 0.1472–0.2028) and HCoV (D = 0.1413–0.2224) showed low synchronicity, except for HCoV in 2018 (D = 0.0798).

Fig. 1.

The results of dynamic time warping (DTW). Figure 1 provides results of the dynamic time warping analyses. Blue line means positivity trends of KDCA data and red dash line means those of multicenter retrospective cohort data in each year. IFV, RSV, HMPV, and PIV showed synchronicity

Seasonal factors in annual virus prevalence

IFV, RSV, PIV, and HMPV demonstrated 12-month periodicity between 2015 and 2018 in SARIMA analyses (Table 3). On the other hand, RV and HCoV did not exhibit any clear periodicity during this period. The peak incidence of IFV and RSV occurred during the winter season. PIV showed a peak incidence between the spring and summer seasons, while HMPV peaked during the spring season. These seasonal patterns were consistent with the findings for the KDCA dataset, except for HCoV (Supplementary Table 2).

Table 3.

Results of seasonality and peak for each virus in this study. Seasonality in 12-month intervals was observed for RSV, IFV, PIV, and HMPV. RSV and IFV were identified as winter viruses, PIV as a spring/summer virus, and HMPV as a spring virus

| Viruses | RV | HCoV | RSV | IFV | PIV | HMPV |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Periodicity | No | No | 12 months | 12 months | 12 months | 12 months |

| Peak | - | - | Winter | Winter | Spring/Summer | Spring |

SARIMA Seasonal Autoregressive Integrated Moving Average, AR autoregressive, I integrate, MA moving average, RV rhinovirus, HCoV human coronavirus, RSV respiratory syncytial virus, IFV influenza virus, PIV parainfluenza virus, HMPV human metapneumovirus

Discussion

In the context of the coronavirus 2019 pandemic, the requirement for extensive studies of respiratory viruses has increased due to their health effects [17]. However, both prospective and retrospective studies focusing on respiratory viruses, including their impact on chronic disease patients, have inherent limitations, particularly in terms of their national representativeness [10, 18]. Prospective studies often encounter challenges related to the cost of collecting large-scale data, while nationwide datasets may lack detailed disease-specific information. Bridging the gap between these research needs and the realities of data availability would allow more comprehensive analyses of chronic respiratory diseases.

Our analysis demonstrated several significant findings for this aspect. First, we established the representativeness of the retrospective cohort study compared to nationwide surveillance data through various techniques, such as correlation and time-series analyses. The overall dataset showed strong correlations, with RSV and IFV demonstrating particularly strong associations. The data from 2018 consistently showed high correlations across all virus types. Most viruses, except RV and HCoV, showed very close alignment between the two time-series datasets in DTW analyses. From these results, we can use cohort data as representing features of causative pathogen of COPD and asthma exacerbation in South Korea. The data can be integrated with other relevant data from South Korea, including temperature, humidity, and air pollution data, which contribute to exacerbations. To our best knowledge, this was the first study to demonstrate the national representativeness of causative viruses’ cohort. Second, we demonstrated the peak season of each virus on cohort that may cause exacerbations. RSV, IFV, PIV, and HMPV exhibited 12-month seasonality. The peak incidence was in the winter for RSV and IFV, spring to summer for PIV, and spring for HMPV. These patterns aligned with the findings from the analysis of KDCA data, suggesting that the cohort data align with nationwide patterns.

This study had several limitations. First, some viruses, such as HBoV and AdV, were not included in the final analysis due to small sample sizes. However, most respiratory viruses were included. Further research is needed to investigate the excluded viruses. Second, the annual data did not consistently show the same distribution. However, despite this variability, there was a significant overall correlation. In particular, the data from 2018 showed a very strong correlation. Therefore, utilizing the 2018 data may help mitigate potential biases in the analysis. Third, due to differences in the characteristics of the two datasets, some patient overlap is possible. The KDCA data were collected from primary care and hospital-level institutions, while the multicenter cohort data were from tertiary/general or university hospitals. Although some overlap in participants might occur, the number is likely very small given the distinct settings of the datasets. To account for this, we conducted the same analysis assuming full overlap of patients, and the results showed no significant differences (Supplementary Table 3). Fourth, the age profiles of the two datasets were not comparable due to the study settings. The KINRESS dataset included results from all age groups in the nationwide surveillance system, while the retrospective cohort study focused on asthma (≥ 18-year-old) and COPD (≥ 40-year-old). Further research matching the nationwide age-stratified data with the cohort data will be necessary.

Conclusions

In conclusion, this study used correlation and time-series analysis techniques to demonstrate the potential national representativeness of retrospectively collected multicenter cohort data on COPD and asthma exacerbations in South Korea.

Supplementary Information

Acknowledgements

None.

Abbreviations

- AdV

Adenovirus

- COPD

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

- DTW

Dynamic time warping

- HBoV

Human bocavirus

- HCoV

Human coronavirus

- HMPV

Human metapneumovirus

- IFV

Influenza virus

- KDCA

Korean Disease Control and Prevention Agency

- KINRESS

Korean Influenza and Respiratory Viruses Surveillance System

- KNIH

Korean National Institute of Health

- PIV

Parainfluenza virus

- PCR

Polymerase chain reaction

- RSV

Respiratory syncytial virus

- RV

Rhinovirus

- SARIMA

Seasonal autoregressive integrated moving average

Authors’ contributions

TJ An, DK Kim, and CK Rhee make up the concept of this study. KH Yoo, YI Hwang, KH Min, DK Kim, YS Sim, JY Jung, TJ An, and CK Rhee acquired the dataset. J Lee and M Shin curated a dataset and performed formal analysis. Initial investigation was performed by TJ An. CK Rhee and KH Min validated the study results. Original draft was wrote by TJ An and CK Rhee. All authors reviewed and edited the manuscript.

Funding

This study was supported by grants from the Korean Environment Industry and Technology Institute through the Core Technology Development Project for Environmental Disease Prevention and Management, funded by the Korea Ministry of Environment (Grant number 2022003310008).

Availability of data and materials

The KINRESS dataset are available on the Infectious Disease Portal, https://www.kdca.go.kr/npt/biz/npp/iss/influenzaStatisticsMain.do and https://www.kdca.go.kr/npt/biz/npp/iss/ariStatisticsMain.do. The data of retrospective cohort study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was approved and informed consent was waived due to its anonymization (KINRESS) and retrospective nature of multicenter data (retrospective cohort) by the Institutional Review Board of the Catholic University of Korea Yeouido St. Mary’s Hospital (approval number SC23ZISE0002).

Consent for publication

All authors agreed with publication.

Competing interests

CK Rhee received consulting/lecture fees from MSD, AstraZeneca, GSK, Novartis, Takeda, Mundipharma, Boehringer-Ingelheim, Teva, Sanofi, and Bayer. Other authors did not have any conflicts of interest to declare.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Jo YS, Rhee CK, Yoon HK, Park CK, Lim JU, An TJ, Hur J. Evaluation of asthma-chronic obstructive pulmonary disease overlap using a mouse model of pulmonary disease. J Inflamm (Lond). 2022;19(1):25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.An TJ, Rhee CK, Kim JH, Lee YR, Chon JY, Park CK, Yoon HK. Effects of macrolide and corticosteroid in neutrophilic asthma mouse model. Tuberc Respir Dis. 2018;81(1):80–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.An TJ, Kim JH, Park CK, Yoon HK. Tiotropium bromide has a more potent effect than corticosteroid in the acute neutrophilic asthma mouse model. Tuberc Respir Dis. 2022;85(1):18–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lee EG, Rhee CK. Epidemiology, burden, and policy of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in South Korea: a narrative review. J Thorac Dis. 2021;13(6):3888–97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.An TJ, Yoon HK. Prevalence and socioeconomic burden of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. JKMA. 2018;61(9):533–8. [Google Scholar]

- 6.An TJ, Yoo YJ, Lim JU, Seo W, Park CK, Rhee CK, Yoon HK. Diaphragm ultrasound is an imaging biomarker that distinguishes exacerbation status from stable chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2022;17:3–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wedzicha JA. Role of viruses in exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Proc Am Thorac Soc. 2004;1(2):115–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hewitt R, Farne H, Ritchie A, Luke E, Johnston SL, Mallia P. The role of viral infections in exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and asthma. Ther Adv Respir Dis. 2016;10(2):158–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sethi S, Sethi R, Eschberger K, Lobbins P, Cai X, Grant BJ, Murphy TF. Airway bacterial concentrations and exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2007;176(4):356–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lee HW, Sim YS, Jung JY, Seo H, Park JW, Min KH, Lee JH, Kim BK, Lee MG, Oh YM, et al. A multicenter study to identify the respiratory pathogens associated with exacerbation of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in Korea. Tuberc Respir Dis (Seoul). 2022;85(1):37–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Choi J, Shim JJ, Lee MG, Rhee CK, Joo H, Lee JH, Park HY, Kim WJ, Um SJ, Kim DK, Min KH. Association between air pollution and viral infection in severe acute exacerbation of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. J Korean Med Sci. 2023;38(9):e68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sim YS, Lee JH, Lee EG, Choi JY, Lee CH, An TJ, Park Y, Yoon YS, Park JH, Yoo KH. COPD Exacerbation-related pathogens and previous COPD treatment. J Clin Med 2022, 12(1):111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kim JM, Jung HD, Cheong HM, Lee A, Lee NJ, Chu H, Lee JY, Kim SS, Choi JH. Nation-wide surveillance of human acute respiratory virus infections between 2013 and 2015 in Korea. J Med Virol. 2018;90(7):1177–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Giorgino T. Computing and visualizing dynamic time warping alignments in R: the dtw package. J Stat Softw. 2009;31:1–24. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nobre FF, Monteiro ABS, Telles PR, Williamson GD. Dynamic linear model and SARIMA: a comparison of their forecasting performance in epidemiology. Stat Med. 2001;20(20):3051–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hyndman RJ, Khandakar Y. Automatic time series forecasting: the forecast package for R. J Stat Softw. 2008;27:1–22. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fauci AS. It ain’t over till it’s over…but it’s never over — emerging and reemerging infectious diseases. N Engl J Med. 2022;387(22):2009–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.To KKW, Chan KH, Ho J, Pang PKP, Ho DTY, Chang ACH, Seng CW, Yip CCY, Cheng VCC, Hung IFN, Yuen KY. Respiratory virus infection among hospitalized adult patients with or without clinically apparent respiratory infection: a prospective cohort study. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2019;25(12):1539–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The KINRESS dataset are available on the Infectious Disease Portal, https://www.kdca.go.kr/npt/biz/npp/iss/influenzaStatisticsMain.do and https://www.kdca.go.kr/npt/biz/npp/iss/ariStatisticsMain.do. The data of retrospective cohort study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.