Abstract

Background

Colorectal cancer (CRC) risk is strongly affected by dietary habits with red and processed meat increasing risk, and foods rich in dietary fibres considered protective. Dietary habits also shape gut microbiota, but the role of the combination between diet, the gut microbiota, and the metabolite profile on CRC risk is still missing an unequivocal characterisation.

Methods

To investigate how gut microbiota affects diet-associated CRC risk, we fed Apc-mutated PIRC rats and azoxymethane (AOM)-induced rats the following diets: a high-risk red/processed meat-based diet (MBD), a normalised risk diet (MBD with α-tocopherol, MBDT), a low-risk pesco-vegetarian diet (PVD), and control diet. We then conducted faecal microbiota transplantation (FMT) from PIRC rats to germ-free rats treated with AOM and fed a standard diet for 3 months. We analysed multiple tumour markers and assessed the variations in the faecal microbiota using 16S rRNA gene sequencing together with targeted- and untargeted-metabolomics analyses.

Results

In both animal models, the PVD group exhibited significantly lower colon tumorigenesis than the MBD ones, consistent with various CRC biomarkers. Faecal microbiota and its metabolites also revealed significant diet-dependent profiles. Intriguingly, when faeces from PIRC rats fed these diets were transplanted into germ-free rats, those transplanted with MBD faeces developed a higher number of preneoplastic lesions together with distinctive diet-related bacterial and metabolic profiles. PVD determines a selection of nine taxonomic markers mainly belonging to Lachnospiraceae and Prevotellaceae families exclusively associated with at least two different animal models, and within these, four taxonomic markers were shared across all the three animal models. An inverse correlation between nonconjugated bile acids and bacterial genera mainly belonging to the Lachnospiraceae and Prevotellaceae families (representative of the PVD group) was present, suggesting a potential mechanism of action for the protective effect of these genera against CRC.

Conclusions

These results highlight the protective effects of PVD while reaffirming the carcinogenic properties of MBD diets. In germ-free rats, FMT induced changes reminiscent of dietary effects, including heightened preneoplastic lesions in MBD rats and the transmission of specific diet-related bacterial and metabolic profiles. Importantly, to the best of our knowledge, this is the first study showing that diet-associated cancer risk can be transferred with faeces, establishing gut microbiota as a determinant of diet-associated CRC risk. Therefore, this study marks the pioneering demonstration of faecal transfer as a means of conveying diet-related cancer risk, firmly establishing the gut microbiota as a pivotal factor in diet-associated CRC susceptibility.

Video Abstract

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s40168-024-01900-2.

Introduction

The risk of colorectal cancer (CRC), the third most common cancer worldwide [1], is strongly affected by dietary habits (https://wcrf.org/diet-activity-and-cancer/). Specifically, red/processed meat consumption has been associated with an elevated CRC risk due to mutagenic compounds generated during food cooking and N-nitroso compounds formed in the colon, whose production is catalysed by heme iron present in red meat [2, 3]. Heme iron can also catalyse lipid peroxidation, leading to the formation of cytotoxic and genotoxic alkenals in the colon, capable of inducing positive selection of precancerous cells [3, 4]. Antioxidants, especially lipid-soluble tocopherols, have been shown to modulate red meat-associated cancer risk by controlling heme iron-induced lipid peroxidation [5–7].

Contrary to red and processed meat, foods rich in dietary fibres have been associated with a lower CRC risk, while for other foods, like fish, despite epidemiological studies suggest a lower risk [8, 9], this evidence is deemed limited (https://wcrf.org/diet-activity-and-cancer/). Rodent studies indicate a protective effect of fish oils (ω3 lipids), but research on fish consumption is insufficient [9]. The gut microbiota is strongly influenced by dietary habits [10]; it has been associated with heme-induced peroxidation in CRC [11], and it may influence CRC risk associated with red meat [12]. While some reports suggest a positive link between fish consumption and increased gut microbiota diversity [13], evidence remains limited, leaving the question of whether fish-based diets benefit from changes in the intestinal microbiota somewhat unanswered.

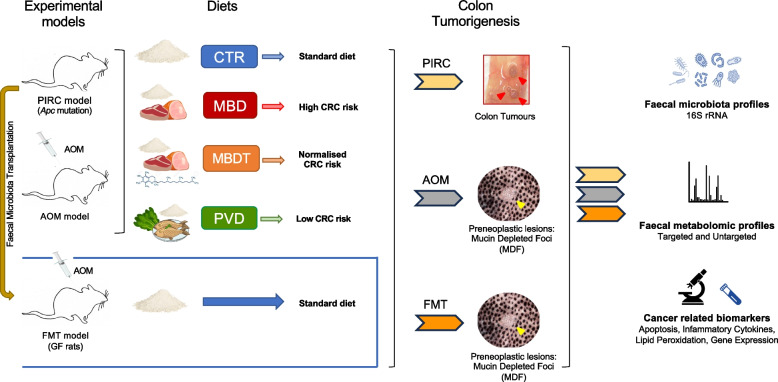

Given these considerations, our study aimed to comparatively investigate the effects of a high-risk red/processed meat-based diet (MBD), a normalised-risk diet (MBD supplemented with α-tocopherol, MBDT), and a low-risk pesco-vegetarian diet (PVD) based on codfish and spinach on colon tumorigenesis, colon mucosa, lipid peroxidation markers, faecal microbiota, and metabolite patterns. A further experimental group (control group, CTR) was also included, fed a basic rodent synthetic control diet, consisting in a low-calcium AIN-76 diet, which has been shown to highlight the cancer-promoting activity of red-processed meat [5, 14]. Our biological inquiry focuses on the mechanisms through which both high-risk and low-risk diets can influence the microbiota and, conversely, how the microbiota can affect the process of intestinal carcinogenesis. We used two complementary animal models of colon carcinogenesis: PIRC rats, mutated in Apc, a key gene in CRC development, which spontaneously develop colon tumours [15], and azoxymethane (AOM)-induced rats, developing colon preneoplastic lesions [14, 16]. Additionally, to establish a direct causal link between the gut microbiota and carcinogenesis and to test whether diet-influenced microbiota could transmit cancer risk, we performed a faecal microbiota transplantation (FMT) experiment from PIRC rats fed the abovementioned diets into germ-free (GF) rats in which carcinogenesis was induced with AOM (experimental scheme described in Fig. 1). We observed a protective effect in the PVD group with the reduction of several tumour biomarkers in both PIRC and AOM models as well as an increase of them in the MBD group. The variation in CRC was associated with changes in the bacterial and metabolic profiles. We described specific correlations between genera belonging to the Prevotellaceae and/or Lachnospiraceae family and bile acids. Furthermore, through the FMT experiment, we highlighted the connection between microbiota and CRC risk.

Fig. 1.

Experimental design. Schematic representation of the experiments performed to understand the effects of the different diets (CTR, MBD, MBDT, and PVD) on colon tumorigenesis, faecal microbiota, metabolite patterns, and cancer-related biomarkers. The four experimental diets (CTR, MBD, MBDT, and PVD) were tested for 3 months in two complementary animal models: PIRC rats (PIRC model) and azoxymethane (AOM)-treated rats (AOM model). PIRC rats, mutated in Apc, a key gene in CRC development, spontaneously develop colon tumours that can be enumerated at sacrifice, after 3 months of feeding as indicated by red arrowheads in the picture of tumours in a PIRC rat [15]. In the AOM model, F344 rats are treated with the specific colon carcinogen AOM to induce colon preneoplastic lesions such as mucin-depleted foci (MDF), which can be easily visualised in the unsectioned colon of the animals through a mucin-specific staining [14, 16]; the yellow arrowhead in the picture indicates an example of a MDF in an AOM-treated rat, as observed at microscope (magnification 40X). In addition, to test whether diet-influenced microbiota could transmit cancer risk when transplanted into GF AOM-treated rats, we performed a faecal microbiota transplantation (FMT) experiment in which the faeces of PIRC rats, collected at the end of the four dietary treatments, were transplanted into GF rats that were treated with AOM to induce colon tumorigenesis and then fed with a control diet (Standard AIN-76) for 3 months; and finally, tumorigenesis was determined, as in the AOM model, counting MDF in the colon after 3 months. In all the experimental models, we identified faecal microbiota and metabolomic profiles, together with specific cancer-related biomarkers, as described in the “ Methods” section. Images of PIRC colon tumours and MDF are from Giovanna Caderni

Methods

Experimental diets

Experimental diets (Supplementary Table S1) were formulated in two separate locations: in Italy (for the PIRC rat experiment) and in France (for the AOM experiment) following the same protocol. These diets were administered in powdered form (for all diets) with included portions of cooked meat and ham (MBD and MBDT) or cooked fish pieces (PVD). Organic spinach powder was purchased from SAS Lyophilise.fr (Lorient, France), while beef sirloin and codfish fillets were purchased frozen from local suppliers (Geloin, Florence, Italy, and Picard, France) (Supplementary Table S2). The cooked ham was sourced from COOP.it (Italy) and Votrecharcutier.fr (France). To prevent food oxidation, the ham, beef, and fish were stored frozen until microwave cooking (every 2 weeks, for beef and fish) and then frozen again in two-rat portions until distributed to animals, every day at the end of the day, just before rat active period, to avoid food oxidation. All diets were based on modified low calcium AIN-76 diets with two powder compositions: one for rat acclimatisation and CTR diet group and one to complement beef/cooked ham and fish in the MBD, MBDT, and PVD groups. Powder for the PVD group contained 8.2% w/w spinach powder; powder for the MBDT group contained 0.1% w/w α-tocopherol. Powder for acclimatisation and CTR group contained 32% of casein as protein source, while complement powders of other diets contained no protein, because the protein source was meat or fish. All diets were balanced for protein content; protein amounts in beef, fish, and ham were calculated from Ciqual tables. All diets contained 5% w/w safflower oil (MPBio, France). CTR diet contained 10.16% lard to balance lipids present in the meat occurring in MBD and MBDT.

PIRC rat model

PIRC rats (F344/NTac-Apcam1137) were obtained from the National Institutes of Health (NIH), Rat Resource and Research Center (RRRC) (University of Missouri, Columbia, MO, USA), and bred in CESAL (Housing Centre for Experimental Animals of the University of Florence, Italy). Approval to perform the experiments was obtained from the Animal Subjects Review Board of the University of Florence and by the Italian Ministry of Health, according to EU Directive 2010/63/EU for animal experiments (authorization: 319/2018-PR). The PIRC rat colony was maintained by mating heterozygous PIRC with wt rats, genotyping pups at 3 weeks of age, as previously described [17]. Male PIRC rats entering in the experiment were maintained in polyethylene cages with their respective mothers up to 4 weeks of age; then, they were separated and fed for 1 week with a CTR diet (Supplementary Table S1) to collect faeces, before the beginning of the experiment. Rats were then allocated to the different dietary treatments (n = 11 in CTR and n = 12 in all the other groups). At day 50, they were individually placed in plastic metabolic cages to separately collect urine and faeces. The rats were euthanized after 3 months of feeding. At sacrifice, the entire colon and small intestine were opened to enumerate the macroscopic tumours.

AOM-treated rat model

F344 male rats were purchased from Charles River at 5 weeks of age. They were randomly assigned to their respective group (12 rats/group) and housed in wire cages to collect faeces (2 animals/cage). After 1 week of acclimatisation with CTR diet, animals were injected with AOM (Sigma-Aldrich) in buffered saline solution (20 mg/kg i.p.) to induce colon tumorigenesis. One week after AOM injection, rats were given their respective experimental diets (Supplementary Table S1). At day 50, they were individually placed in plastic metabolic cages to separately collect urine and faeces. They were euthanized after 3 months of feeding. At sacrifice, the colons were removed and the number of MDF and ACF determined as previously described [14, 17]. Faeces were collected just before the start of the experimental diets (T0) and just before the end of the experimentation (T3). Approval to perform these and the permeability experiments outlined below was obtained from the French Comité d'Ethique CEEA-86 and the Ministère de l'Education Nationale, de l'Enseignement Supérieur et de la Recherche (authorization: APAFiS no. 16139-2018071617502938v3).

Permeability experiment

F344 rats were purchased from Charles River at 5 weeks of age. They were randomly assigned to their respective dietary group (eight rats/group). After 1 week of acclimatisation, they were given the four experimental diets (Supplementary Table S1) for 2 weeks. They were then placed in metabolic cages for 24 h to collect faeces and urine. They were then treated orally with 51CrEDTA (25.9 kBq) (PerkinElmer Life Science) diluted in 0.5 ml of saline solution; their urine was then collected for 24 h more, and its radioactivity was determined with a gamma counter (Cobra II; Packard) to measure intestinal permeability. Rats were then replaced in conventional cages and fed the experimental diets for one more week to decrease residual radioactivity before euthanasia. Colons were collected for cytokine assays.

Collection of faeces and urine

In both PIRC rats and AOM-treated rats, fresh faeces (at least five pellets) were collected at the beginning (T0 samples) and at the end of each dietary treatment (T3 samples), rapidly frozen at − 80 °C and then used for 16S rRNA gene sequencing and metabolomic studies. To perform FMT, additional faeces from PIRC rats were collected at the end of the experimental diet period and immediately processed as described below. Three days before sacrifice, in PIRC- and AOM-treated rats, 24-h-faecal pellets and urine samples were also collected in metabolic cages to assess haem, TBARS and free HNE in faecal water (FW), and DHN-MA (1,4-dihydroxynonane mercapturic acid) and 8-isoPGF2α in urine as described below. Faecal water (FW) preparation was as follows: 0.5 g of faeces was solved in 1 ml of distilled water and added with 50 µl of 0.45-M 2,6-ditert-butyl-4-methyl-phenol (BHT) in ethanol. The resulting samples were processed using FastPrep technology with Lysing Matrix E beads in 15-ml tubes and then centrifuged at 3200 g, for 20 min. After centrifugation, supernatants were collected and stored at − 80 °C until use.

Faecal microbiota transplantation model (FMT)

Faecal samples from PIRC rats collected at the end of each dietary treatment (CTR, MBD, MBDT, and PVD) were prepared for FMT by thoroughly dispersion and dilution (1:50 w/v) with a saline solution (sodium chloride 9 g/l, potassium chloride 0.4 g/l) added with L-cysteine 0.5 g/l (Ringer Solution). The suspension was then diluted 1:1 with 20% v/v skimmed milk and stored at − 80 °C. Fischer male F344 rats were obtained from the breeding unit of Anaxem, the GF facility of the Micalis Institute (INRAE, Jouy-en-Josas, France). All standardised procedures, including the breeding of GF animals, were carried out in France in licenced animal facilities (Anaxem licence number: B78-33–6). The experimental protocol was agreed upon by the French Ministère de l’Education Nationale, de l’Enseignement Supérieur et de la Recherche (APAFIS no. 27039). GF rats were given free access to autoclaved tap water and a gamma-irradiated (45 kGy) standard diet (AIN-76 diet) referred to as control diet. GF rats were randomised into the four experimental groups (n = 10 in CTR, MBDT, and PVD groups, and n = 8 in MBD group), and each group was housed in a distinct sterile isolator, with five cages per isolator (two rats/cage). Transplantation was achieved by oral-gastric gavage with 1 ml of the diluted faecal samples from PIRC rats fed the four different diets (CTR, MBD, MBDT, PVD) as described previously [18]. Three weeks after FMT, recipient rats were treated with AOM (20 mg/kg i.p.) to induce colonic preneoplastic lesions. After AOM injection, all rats received the same control diet ad libitum, for 14 weeks following AOM injection. Body weight and diet consumption were measured weekly. At sacrifice, the colons were removed and the number of MDF (n = 8 in CTR, n = 7 in MBD, and n = 9 in MBDT and PVD) and ACF (n = 10 in CTR, MBDT, and PVD groups, and n = 8 in MBD group) determined as described [14, 17].

Determination of myeloperoxidase activity in the colon mucosa

Myeloperoxidase activity (MPO) was determined in the colon of AOM-treated rats (n = 10 in CTR and PVD, n = 12 in MBD and MBDT) as previously described [19], with only slight modifications: the MPO activity kinetics were performed in 96-well plates and recorded for 5 min; a MPO standard curve was used for quantitation. Protein levels were measured using the BCA assay (Pierce BCA Protein Assay Kit, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Rockford, USA).

Determination of markers of lipid peroxidation, oxidative stress in the urine, and FW

DHN-MA is the major urinary metabolite of HNE, a lipid peroxidation product. DHN-MA was measured in urine after dilution (1/200 to 1/1000 in the dedicated buffer), through Enzyme ImmunoAssay (EIA) using Bertin Bioreagent kit, according to manufacturer’s instructions. 8-isoPGF2α is formed upon arachidonic acid nonenzymatic oxidation; it was here quantified in urine after dilution (1/20 in the dedicated buffer) by Enzyme ImmunoAssay (EIA) using Bertin Bioreagent kit, according to manufacturer’s instructions. Faecal TBARS and free HNE were measured in FW according to Ohkawa et al. [20] and Chevolleau et al. [21], respectively. In the PIRC rats for TBARS in FW, n = 9 in CTR and MBDT groups and n = 12 in MBD and PVD groups; for HNE in FW, n = 9 in CTR and MBDT groups and n = 12 in MBD and PVD groups; for urinary DHN-MA, n = 7 in CTR group, n = 12 in MBD group, n = 8 in MBDT group, and n = 10 in PVD group; and for urinary 8-isoPGF2α, n = 7 in CTR and MBDT groups, n = 12 in MBD group, and n = 10 in PVD group. In the AOM rats for TBARS in FW, n = 6 for all the groups; for HNE in FW, n = 6 in CTR, MBDT, and PVD groups and n = 5 in MBD group; for urinary DHN-MA, n = 11 in CTR group and n = 12 in the other groups; and for urinary 8-isoPGF2α, n = 12 for all the groups.

FW cytotoxicity on “Co” cell culture

“Co” (derived from C57BL/6 J mice and ImmortoMouse®) colon epithelial cells express the heat-labile SV40 large T antigen (AgT tsa58) under the control of an IFNγ-inducible promoter [22]. Those “Co” cells express cytokeratin 18, an epithelial phenotype marker. Cell proliferation and phenotype are affected by culture conditions: at 33 °C with IFNγ, the large T antigen is active and drives cellular proliferation, while at 37 °C, the temperature-sensitive mutation yields an inactive protein, and cells act like non-proliferating epithelial cells. All the studies were conducted at 37 °C. Cytotoxicity of FW from different dietary groups was quantified using the WST-1 assay on colon epithelial cell line, after treatment with diluted (1/20) and filtered FW.

Colon cytokines

Colon samples were FastPrep ground in FastPrep Lysing Matrix D tubes with RIPA buffer containing protease inhibitors, centrifuged at 10,000 g for 15 min, at 4 °C. Supernatants were collected and stored at − 80 °C until use. Proteins were quantified using the BCA kit (Pierce).

Cytokines were quantified using R&D systems kits (Bio-Techne) (IL-6: DY506; IL-1β: DY501; TNF-α: DY510), according to the manufacturer’s instructions. In PIRC rat’s normal mucosa for IL-6, n = 5 in CTR and MBD and n = 6 in MBDT and PVD groups; for TNF-α, n = 6 in CTR and PVD groups and n = 5 in MBD and MBDT; and for IL-1β, n = 5 in CTR and MBD groups and n = 6 in MBDT and PVD groups. In AOM-treated rats’ normal mucosa for IL6, n = 11 in CTR and PVD groups, n = 8 in MBD, and n = 10 in MBDT, and for IL-1β, n = 12 in all the groups. In the normal mucosa of the permeability experiment rats for TNF-α, n = 8 in CTR, MBDT, and PVD and n = 7 in MBD; for IL-6, n = 8 in CTR and MBDT and n = 7 in MBD in PVD; and for IL-1β, n = 8 in all the groups.

Evaluation of proliferation, apoptosis, CD68, and Dcamk1 in colon mucosa and tumours

Proliferative activity in tumours and in the normal mucosa of PIRC- and AOM-treated rats was evaluated measuring the proliferating cell nuclear antigen (PCNA) immunoreactivity with a mouse monoclonal antibody (PC-10, Santa Cruz, CA, USA), as previously reported [17]. CD68 and Dcamkl1 expressions were also evaluated in normal mucosa of PIRC rats (CD68: n = 10 in CTR group, n = 12 in MBD and PVD groups, n = 11 in MBDT group; Dcamkl1: n = 9 in CTR and MBD groups and n = 10 in MBDT and PVD groups); AOM-treated rats (CD68: n = 9 in CTR group, n = 11 in MBD group, n = 8 in MBDT group, and n = 10 in PVD group) and in PIRC tumours (CD68: n = 10 in CTR group, n = 12 in MBD group, and n = 11 in MBDT and PVD groups) with immunohistochemistry experiments [23]. Apoptosis was evaluated morphologically in histological longitudinal Sects. (5 µm thick) of the normal mucosa of PIRC rats (n = 10 in CTR group, n = 12 all the other groups), AOM-treated rats (n = 7 in CTR group, n = 10 in the other groups), and in PIRC tumours (n = 9 in CTR group, n = 11 in MBD and PVD groups, and n = 12 in MBDT group) stained with haematoxylin–eosin, as reported [17].

Semiquantitative RT-PCR in colonic tissue

Total RNA was extracted by TRIzol reagent (Ambion) from the colonic normal mucosa and colonic tumour collected at the time of sacrifice. RNA (300 ng) was reverse transcribed in cDNA using the RevertAid RT Kit (Thermo Scientific), according to manufacturer’s instructions. The list of primers used in RT-PCR is reported in Supplementary Table S3. The amplification conditions and the analysis of gene expression were carried out following the procedures previously described [17].

Bacterial DNA extraction, 16S rRNA gene sequencing, and sequencing data analysis

Faecal samples from all rats collected at all time points were stored at − 80 °C, and then DNA extraction was carried out by using DNeasy PowerLyzer PowerSoilKit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) following the manufacturer’s instructions. Library preparation and sequencing of the V3–V4 region of the 16S rRNA gene were carried out on Illumina MiSeq platform in paired-end mode (PE300). All additional details are reported in supplementary methods. Primer pairs were removed by using cutadapt version 3.5 [24]. Amplicon sequence variants (ASVs) were identified from the raw sequences using the DADA2 pipeline version 1.26 [25]. Taxonomic classification was performed using the DECIPHER package version 2.14 with the latest version of the pre-formatted SILVA small-subunit reference database [26] (SSU version 138, available at http://www2.decipher.codes/Downloads.html). All sequence variants not classified as bacteria were removed together with chloroplasts or mitochondria sequences.

DADA2 pipeline and subsequent statistical analyses were conducted in R environment version 4.2.2 (R Core Team, 2022 — https://www.r-project.org). β-diversity analyses were conducted using “vegan” package version 2.6–4 [27]. Significant taxonomic features were obtained by performing the linear discriminant analysis effect size (LEfSe) on relative abundances table after counts per million (CPM) transformation [28]. Likelihood ratio test (LRT) was performed by using “DESeq2” package version 1.38.3 [29]. Environmental fitting analysis was performed by using the envfit function in the “vegan” package. Additional details on sequence variants inference and statistical analyses were reported in supplementary materials and methods.

Metabolomics and data analysis

Metabolite profiles in faecal samples of all the rats of the experiments at all time points described were covered through four independent procedures based on gas chromatography (GC–MS) and liquid chromatography-high-resolution tandem mass spectrometry (LC–MS/MS). Samples were separately extracted with both methanol and water to respectively obtain methanolic supernatants for bile acid analysis and aqueous supernatants for the other three procedures (SCFAs, semipolar metabolites, and methyl-chloroformate derivatives). Details are reported in supplementary methods.

Short-chain fatty acids

Samples were acidified using hydrochloric acid and spiked with deuterium-labelled internal standards. Analysis was performed using a high polarity column (Zebron™ ZB-FFAP, GC Cap. Column 30 m × 0.25 mm × 0.25 μm, Phenomenex, Torrance, CA, USA) installed in a GC–MS (7890B, Agilent, Santa Clara, CA, USA) coupled with a quadrupole detector (5977B, Agilent). The system was controlled by ChemStation; raw data were converted to NetCDF format using ChemStation (Agilent) and imported and processed in MATLAB R2014b (MathWorks, Inc.) using the PARADISe software described by Johnsen et al. [30].

Semipolar metabolites

Faecal water samples were diluted (1/10) in 1% formic acid in 10-mM ammonium formate; the suspensions were mixed for 2 min at 4 °C, and then centrifuged at 12,000 g, at 4 °C, for 10 min. The analysis was carried out by LC–MS/MS, using a Vanquish system coupled to a hybrid quadrupole Orbitrap, Q Exactive HF (both from Thermo Fisher Scientific, Bremen, Germany) working in polarity switching and in data-dependent scanning mode. A heated electrospray interface (HESI) was interfaced to the chromatographic stream, and analyte separation was achieved through a thermostated (30 °C) reversed phase column (ACQUITY HSS-T3 C18, 150 × 2.1, 1.8 µm, Waters, Milford, MA, USA). Mobile phases consisted of 10-mM ammonium formate in 0.1% formic acid in water (solvent A, pH 3.1) and 10-mM ammonium formate in 0.1% formic acid in methanol (solvent B). Samples were injected in partial loop mode, and analytes were separated through the following gradient of solvent B (minutes/%B): (0/0), (2/0), (12/35), (13/90), and (14/90), at a flow rate of 0.3 ml/min. Peak areas were extracted using Compound Discoverer 3.0 (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Compounds identification was performed at four levels according to Sumner et al. [31]. In detail, Level 1 included identification by retention time, accurate mass value (± 3 ppm), and MS/MS spectra matching with in-house authentic reference standards database; Level 2a included the same parameters as Level 1, but without MS/MS spectra; Level 2b was in line with Level 1, but retention time was not used as a discriminant factor; and Level 3 only considered the accurate mass value alone (± 3 ppm), elemental composition, and isotopic patterns as identification parameters. The compound annotations on Level 3 were matched with a publicly available database as Human Metabolome Database (www.hmdb.ca).

Bile acids

Aliquots of 50–100 mg faeces were weighed, and methanol was added by using a 1:4 sample/solvent ratio (w/v). The suspensions were mixed for 1–2 min at 4 °C; then, the samples were centrifuged at 12,000 g, 4 °C, for 10 min, and the supernatants were transferred to a Spin-X centrifuge filters (Corning) and centrifuged again at max speed, 4 °C, for 5 min. The final filtrates were collected for the analysis. Bile acids analysis was carried out by using a Vanquish LC coupled to Thermo Q Exactive HF working in negative ion mode. The chromatographic separation of bile acids was achieved through a Waters ACQUITY HSS T3, 1.8-μm particle size, 2.1 × 150 mm. The column was thermostated at 30 °C; the mobile phases consisted of (A) ammonium acetate 10 mM and (B) methanol: acetonitrile (1:1, v/v), running at a final flow rate of 0.3 ml/min. Bile acids were eluted by linearly increasing solvent B in A from 45 to 100% for 16 min. Peak areas were extracted using TraceFinder 4.1 (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Identification of compounds was based on accurate mass value and retention time of authentic reference standards.

GC–MS methyl-chloroformate derivative metabolites

Samples were derivatized with methyl chloroformate using a slightly modified version of the protocol described by Smart et al. [32]. For such metabolites, the same GC–MS configuration described for SCFA was used. Data were imported and processed in MATLAB R2018b (MathWorks, Inc.) using the PARADISe software described by Johnsen et al. [30]. Briefly, the identification workflow encompassed the elimination of impurities and unresolved redundant peaks and the curation of annotated metabolites based on authentic reference standards and library matching with the NIST Library.

Statistical analysis

Data on tumorigenesis and related cancer markers from tissues (normal mucosa or tumours), FW, and urine were presented as means ± SE. The levels of the markers measured were tested within the four diets or diet- derived FMT groups in the R environment by performing Tukey HSD test using the tukey_hsd function of the “rstatix” package version 0.7.2 (https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=rstatix). Area counts of LC–MS/MS semipolar compounds were loaded in XLStat environment (v. 5.03, Addinsoft, NY, USA) for multivariate data analysis; red to blue through white heatmap was optimised through centering and reduction procedures to magnify association between diet (dendrograms on x-axis) and target analytes (dendrograms on y-axis) following Euclidean distance and the Ward linkage method. For differential analysis, volcano plots compared compound area counts in the four dietary interventions through a 1 vs 1 comparison. False discovery rate was minimised post hoc through Benjamini–Hochberg corrections; parametric test type was used at a significance level of 0.05, through a non-specific filtering with a standard deviation less than 50%. Log2 mean ratio fold change was fixed at 1, and Log10 for p-value was fixed at 2.

Results

Our biological inquiry delves into the dynamics of how high- and low-risk diets impact the gut microbiota and how the microbiota in turn influences the complex process of intestinal carcinogenesis. To investigate how gut microbiota influences diet-linked CRC risk in Apc-mutated PIRC and AOM-induced models, rats were fed for 3 months with different diets: high-risk red/processed meat-based (MBD), normalised risk with α-tocopherol (MBDT), low-risk pesco-vegetarian (PVD), and control (CTR) diets. To highlight the role of microbiota in influencing cancer risk, we also performed faecal microbial transplantation (FMT) from PIRC rats on each diet to GF rats, which were then induced with AOM. The modulation of CRC risk was assessed by the analysis of multiple markers of carcinogenesis, including apoptotic, inflammation, intestinal permeability, and oxidative stress assays. These results were combined with changes in the microbiota as determined by 16S rRNA gene sequencing and changes in metabolic profiles obtained by targeted and untargeted approaches (Fig. 1).

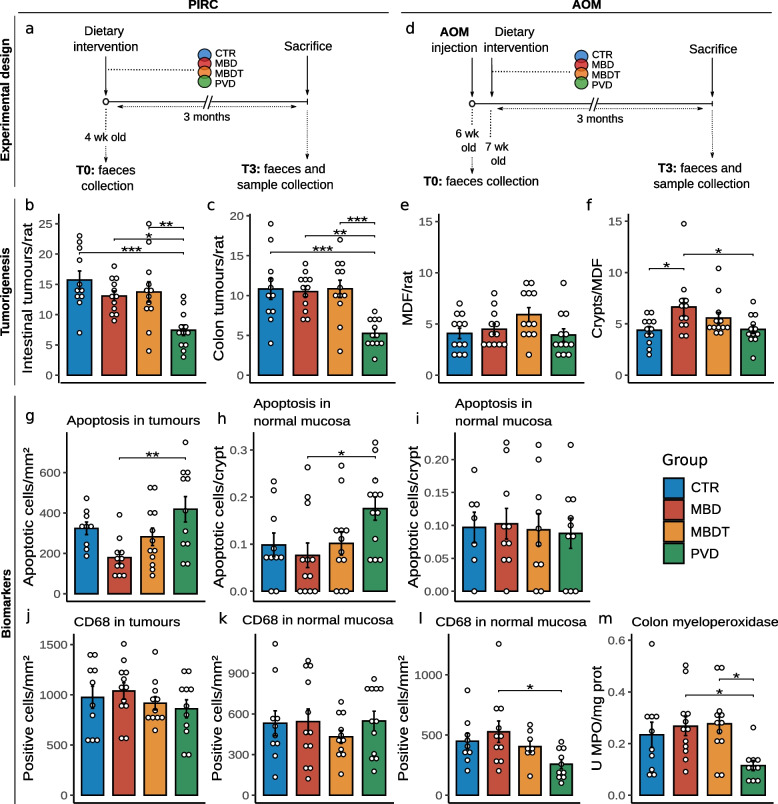

Diet affects tumorigenesis in both PIRC- and AOM-treated rat models

In PIRC rats (Fig. 2a), PVD markedly suppressed tumour formation (Fig. 2b), particularly in the colon (Fig. 2c). The size of colon tumours was not significantly different among groups (data not shown). In the AOM model (Fig. 2d), the number of colon precancerous lesions, known as mucin-depleted foci (MDF) [16], was similar among groups (Fig. 2e). However, the number of crypts forming each MDF (Fig. 2f), a measure of their size, was significantly lower in PVD and control diet (CTR) groups compared to the MBD one, suggesting a slower growth of these lesions. The number of aberrant crypt foci (ACF), another type of preneoplastic lesion [14], was significantly lower in the CTR- and PVD-fed rats compared to MBD- and MBDT-fed ones (Supplementary results). In both models, body weight was not affected by dietary treatment (Supplementary results).

Fig. 2.

Colon tumorigenesis and cancer-related biomarkers in PIRC and AOM models. a, b, c, g, h, and j, k PIRC model experiments. a PIRC model experiment overview; group size (rats): n = 11 (CTR) and n = 12 (MBD, MBDT, and PVD group). b, c Tumour count per rat in the whole intestine (small intestine and colon) and in the colon, respectively. g, h, Apoptosis in colon tumours and in the normal mucosa, respectively. j, k, CD68-positive cells/mm2 in colon tumours and in the normal mucosa, respectively. d, e, f and i, l, m AOM model experiments. d AOM model experiment overview; group size (rats): n = 12 for all the groups. e Number of MDF per rat. f Number of crypts forming each MDF. i Apoptotic cells per crypt in the normal mucosa. l CD68-positive cells/mm2 in the colonic mucosa. m Myeloperoxidase activity in the colon mucosa [19]. Coloured circles in a and d represent the four different diets administered in PIRC- and AOM-treated rats, respectively. Additional details regarding biomarkers description and sample size are reported in the “ Methods” section. Barplots illustrate tumour marker levels for each diet-related group (colour coded). Tukey HSD tests were used for group comparisons, and significant comparisons are denoted with asterisks (*p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001). Error bars in each barplot represent standard errors

Diet affects colon cancer-related biomarkers

The cancer-related biomarkers tested in both models show a similar trend associated with the PVD diet, but opposite when associated with the MBD diet, suggesting that the two diets may influence carcinogenesis-related processes differently. In particular, in PVD-fed PIRC rats, apoptosis in both tumours and normal mucosa was higher than in MBD-fed animals (Fig. 2g, h respectively and Supplementary Fig. S2a, b), while in the AOM model, it was similar in the four diets (Fig. 2i). In both PIRC and AOM models, colon proliferation was not affected by dietary treatments (data not shown), while the expression of Dcamkl1, which is associated with mucosal pro-survival [23], was slightly higher in PIRC MBD-fed rats than in the other groups (Supplementary Fig. S2c). In PIRC rats, the expression of some apoptosis/survival-related genes was also affected by dietary treatments (Supplementary Fig. S3a, b, c, d).

In the PIRC model, expression of the macrophage marker CD68 was similar among groups in both the tumours and normal mucosa (Fig. 2j and k, respectively). Conversely, in the AOM model (Fig. 2l), CD68-positive cells were less abundant in the normal mucosa of the PVD group than in the MBD counterpart. Interestingly, the myeloperoxidase activity in AOM rats was also lower in the PVD than in MBD/MBDT groups (Fig. 2m).

In PIRC rats fed PVD and MBDT diets, IL-6 levels in the normal mucosa were lower than in CTR and MBD groups (Supplementary Fig. S4a). Further, TNF-α levels were slightly lower in the PVD group compared to the others (Supplementary Fig. S4b), while IL-1β levels were similar among groups (Supplementary Fig. S4c). In the AOM model, no significant effects were observed for IL-6 and IL-1β (Supplementary Figs. S4d and S4e, respectively). In PIRC rats, the expression of IL-6, IL-1β, Cox2, and iNOS genes (Supplementary Fig. S3 e, f, g, h) was consistently higher in tumours than in the respective normal mucosa, regardless of the diet.

Gut permeability, tested in a separate experiment (Supplementary Fig. S4i), was lower in the PVD group, than in CTR and MBDT ones. In rats of this experiment, IL-6 levels (Supplementary Fig. S4g) were also lower in the PVD group compared to all the other groups, with a significant difference when comparing PVD with CTR. TNF-α and IL-1β remained similar among the groups (Supplementary Fig. S4f, h).

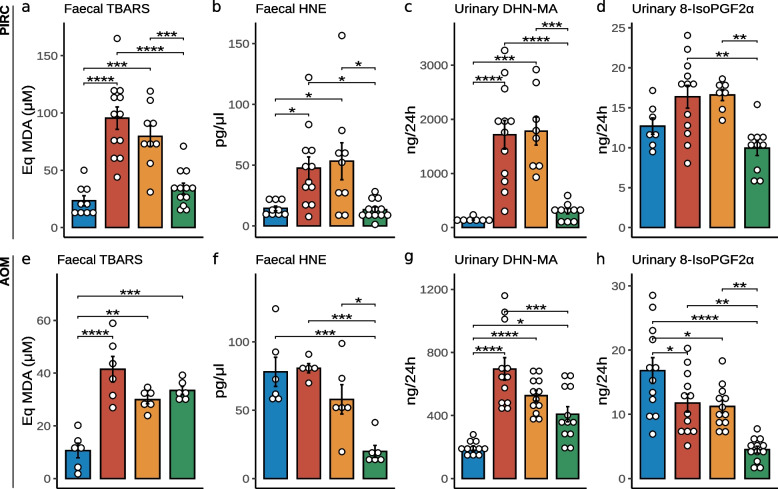

Diet affects lipid peroxidation biomarkers

We have thus studied lipid peroxidation biomarkers that reflect oxidative stress and inflammation in colon tissues, playing a crucial role in understanding and potentially intervening in the initiation and progression of colon cancer. In PIRC rats, faecal thiobarbituric reactive substances (TBARS) (Fig. 3a) and 4-hydroxy-2-nonenal (HNE) (Fig. 3b) levels were lower in the PVD and CTR groups than in MBD and MBDT counterparts. Urinary 1,4-dihydroxynonene mercapturic acid (DHN-MA) (Fig. 3c) and 8-isoprostane (8-isoPGF2α) (Fig. 3d) were also lower in the PVD than in meat-based diets and CTR. Similarly, in the AOM model, HNE was significantly lower in the PVD than in meat-based diets and CTR (Fig. 3f), while urinary DHN-NA (Fig. 3g) and 8-isoPGF2α (Fig. 3h) were lower in the PVD than in the MBD and MBDT groups, with the latter group showing an appreciable but nonsignificant difference only for DHN-NA. Faecal TBARS were higher in the three experimental diets compared to CTR (Fig. 3e). Faecal water (FW) of PIRC MBD-fed rats was slightly more cytotoxic than CTR and PVD-fed counterparts (Supplementary Fig. S2d).

Fig. 3.

Lipid peroxidation and oxidative-stress biomarkers in PIRC and AOM models. Markers of lipid peroxidation and oxidative stress were evaluated in PIRC model (a, b, c, d) and AOM model (e, f, g, h). a, e TBARS in FW (µM eq malondialdehyde, MDA) for PIRC and AOM models, respectively. b, f HNE in FW (pg/µl) for PIRC and AOM models, respectively. c, g Urinary DHN-MA (ng/24-h urine) for PIRC and AOM models, respectively. d, h Urinary 8-isoPGF2α (ng/24-h urine) for PIRC and AOM models, respectively. Additional details regarding biomarkers description and sample size are reported in the “ Methods” section. Barplots illustrate marker levels for each diet group (colour coded). Group comparisons were assessed using the Tukey HSD test, and significant comparisons are indicated with asterisks (*p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001; ****p < 0.0001). Standard errors for each barplot are represented with error bars. Colour legend as in Fig. 2

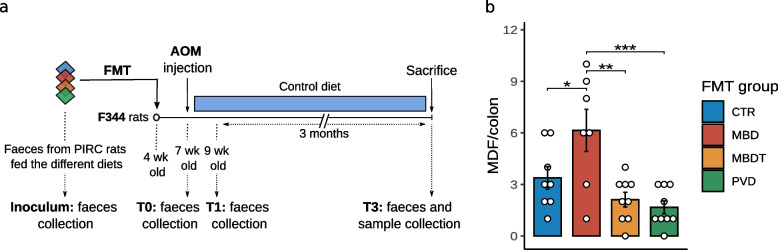

The intestinal microbiota as a determinant of diet-related CRC risk

To establish a direct link between gut microbiota profiles (including taxonomic and metabolic ones) and their impact on colon carcinogenesis, we performed a faecal transplant from PIRC rats fed the above-mentioned diets into GF rats, subsequently induced with AOM and then fed CTR diet for 3 months (Fig. 4a). The use of the control diet following AOM induction was chosen to understand how much the microbiota, modulated by the diet in the PIRC model, carried with it the “memory” of potential promoter of colon carcinogenesis.

Fig. 4.

Colon tumorigenesis in faecal microbiota transplantation (FMT) experiment. a Overview of FMT experiment description. The time points of faecal sampling are reported as follows: T0 (3 weeks after the inoculum with PIRC rat faeces), T1 (2 weeks after AOM injection), and T3 (12 weeks after T1). Coloured diamonds in the a represent the faecal samples, obtained from each dietary group of PIRC rats (coloured circles in Fig. 1a), which were used for the faecal microbiota transplantation (FMT). The light blue rectangle in the timeline represents the CTR diet administered to the animals transplanted with PIRC faeces. b Number of MDF/colon in the rats transplanted with PIRC faeces from the four different groups (sample size is reported in the “ Methods” section). Statistical significance is denoted as follows: *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001, determined by ANOVA followed by Tukey’s test. Standard errors in each barplot are represented with error bars

Strikingly, at the end of this period of 3 months, rats transplanted with faeces from the MBD group exhibited a significantly higher number of preneoplastic lesions (MDF) compared to rats transplanted with faeces from the other dietary groups (Fig. 4b); ACF determination in these animals confirmed these results (Supplementary Fig. S2e, f).

Faecal microbiota analysis in different dietary groups across three experimental models (AOM, PIRC, and FMT)

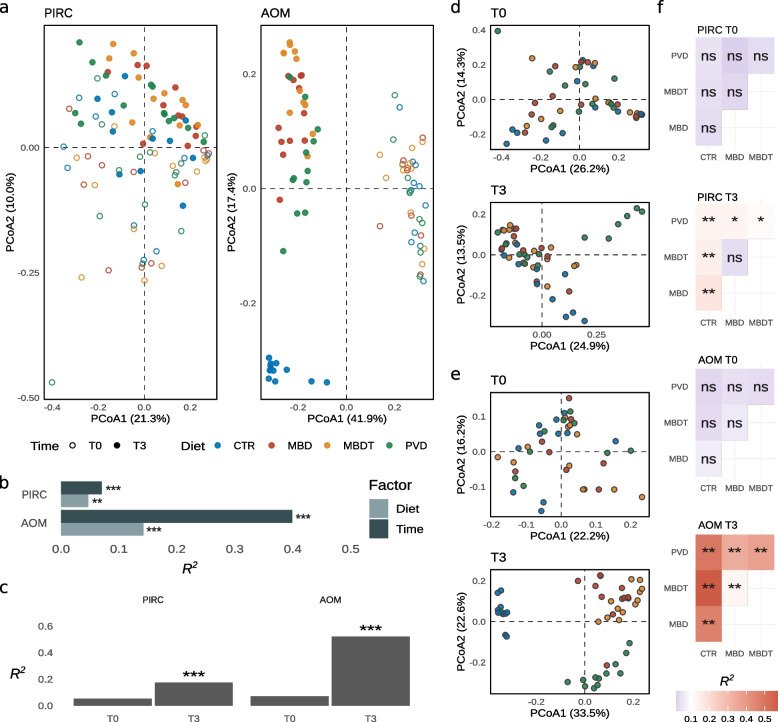

We first compared the faecal microbiota profiles in PIRC and AOM models, regardless of dietary groups, at the beginning of the experiments (T0), finding significant differences in the bacterial diversity (β-diversity) between the two animal models, in accordance with Vitali et al. (2022) [23] (Supplementary Figure S5). Faecal bacterial composition was then evaluated at the beginning (T0) and at the end (T3) of the study, across the AOM, PIRC, and FMT experimental models. β-diversity analysis, employing PCoA based on Bray–Curtis distance, indicated significant influences of dietary regimen (Supplementary Table S4). The PIRC model exhibited comparatively less pronounced effects in terms of significance and explained variance, compared to the AOM model (Fig. 5a, b, c). When examining T0 and T3 data separately (Fig. 5d, e and Supplementary Table S5), PIRC and AOM models showed initial overlap of samples at T0, confirming microbiota homogeneity. After 3 months of different diets (T3), significant alterations in bacterial composition emerged, revealing diet-related clusters in the multidimensional distribution in both models. Pairwise adonis PERMANOVA analysis showed significant diet-based group differences, except for MBD and MBDT in the PIRC model (Fig. 5f, Supplementary Table S6). Explained variance in cross-comparisons highlighted more pronounced diet effects in the AOM than in the PIRC model (colour gradient in Fig. 5f).

Fig. 5.

Bacterial diversity among dietary groups in PIRC and AOM models. a Principal coordinates analysis (PCoA) based on Bray–Curtis distance matrix for both PIRC and AOM models, illustrating sample distribution according to different dietary treatments (represented by colours) and time points (represented by shapes, as indicated by the legend at the bottom of each panel). b Barplot displaying explained variance (R2) values from adonis PERMANOVA was calculated based on the factors in the multidimensional analysis (a). Significant effects associated with each variable (factor) are marked with asterisks (*p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001) and displayed using a grey colour scale. c Explained variance (R2) from adonis PERMANOVA calculated based on the diet variable only. The datasets are split by the time points at the beginning and end of the treatments (T0 and T3) for both PIRC and AOM models. Significant effects linked to the diet variable are indicated by asterisks (***p < 0.001). d, e Principal coordinates analysis (PCoA) based on Bray–Curtis distance matrix demonstrating sample distribution based on the diet variable only (represented by colours). The datasets are separated by time points T0 and T3, as indicated at the top of each panel, for both PIRC (d) and AOM (e) models. f Significant pairs and their related variance explained (R2) values from pairwise adonis PERMANOVA are reported for each group pair according to the model and time. Explained variance (R2) levels are depicted using a blue-red colour gradient, with significant contrasts highlighted by asterisks (ns, p > 0.05; *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01)

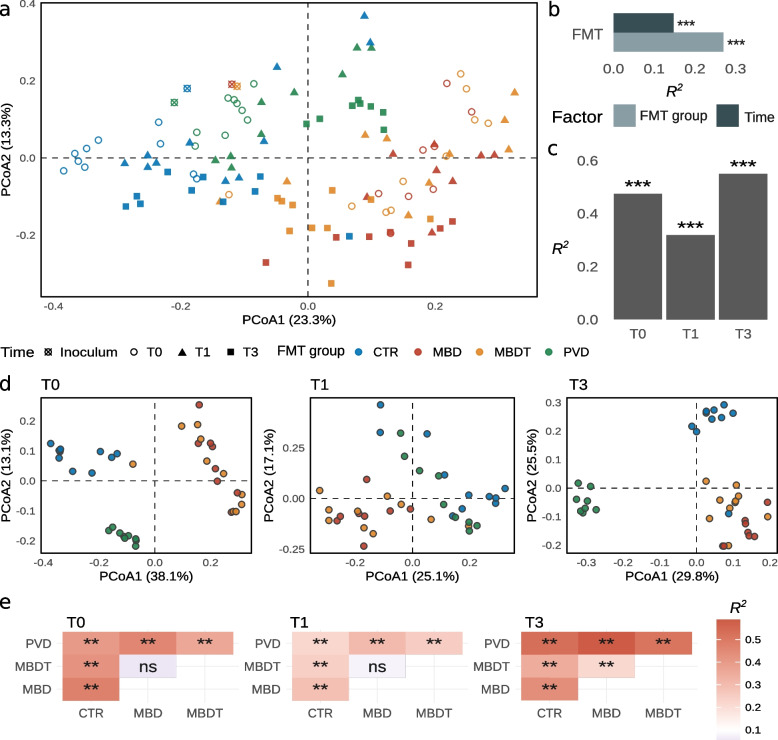

In the FMT experiment, β-diversity analysis using PCoA (Bray–Curtis distance) distinctly exhibited separation among sample groups at different time points (T0, T1, T3) based on the dietary group of the faecal inoculum donors (Fig. 6a). This separation was confirmed by adonis PERMANOVA, highlighting significant effects and explained variance (Fig. 6b, Supplementary Table S4).

Fig. 6.

Bacterial diversity among FMT groups. a Principal coordinates analysis (PCoA) based on the Bray–Curtis distance matrix reveals the distribution of samples according to the diet of faecal inoculum donors (indicated by colour patterns) and time points (indicated by shape patterns, as shown below the panel). b Bar plot displays explained variance (R2) values from adonis PERMANOVA, calculated based on the variables (factors) presented in the multidimensional analysis (a). Significant effects associated with each factor are marked with asterisks (ns, p > 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001), and the factors are represented using a grey colour scale. c Overview of explained variance (R2) values from adonis PERMANOVA, calculated based on the diet FMT group variable only. The datasets were categorised according to the time points after 3, 5, and 17 weeks from microbial inoculation (referred to as T0, T1, and T3, respectively). Significant effects linked to the FMT group factor are denoted by asterisks (***p < 0.001). d, e Principal coordinates analysis (PCoA) based on the Bray–Curtis distance matrix illustrates the sample distribution associated with the FMT group variable only (indicated by the colour pattern). The datasets were divided according to the time points (T0, T1, and T3), as indicated at the top of each panel. Significant pairs and their corresponding variance explained (R2) from pairwise adonis PERMANOVA are provided for each group contrast according to each time point, as mentioned in d and e. Explained variance (R2) levels are depicted using a blue-red colour gradient, with significant differences marked by asterisks (ns, p > 0.05; *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01)

When analysing the dataset across the three sampling times, a significant distinction among the FMT groups emerged (Fig. 6d, Supplementary Table S5). Pairwise adonis PERMANOVA tests confirmed this evident distinction (Fig. 6e, Supplementary Table S6), revealing significant differences associated with the faecal donor’s diet. While no clear differences between the MBD and MBDT groups were observed at T0 and T1, they became evident at T3, suggesting a noteworthy shift in the bacterial community over the 3-month period.

The diets and FMT treatment also produced variations in α-diversity metrics as detailed in Supplementary Fig. S6, Supplementary Table S7 and Supplementary Table S8. The log-likelihood ratio test (LRT of DESeq2) was performed to examine differences in bacterial amplicon sequence variants (ASVs) among experimental groups across the AOM, PIRC, and FMT models (ASVs selected by LRT for each model were resumed in Supplementary Table S9). Hierarchical clustering, performed on the variance-stabilised transformed (VST) abundances of significant ASVs, revealed distinct clusters corresponding to different diets in both the AOM and PIRC models (Supplementary Fig. S7a, b). The MBD and MBDT groups exhibited similar ASVs abundance distributions in both PIRC and AOM models, notably forming a “meat-based diet” cluster. In contrast, in the FMT experiment, a noticeable separation between the MBD and MBDT groups emerged (Supplementary Fig. S7c).

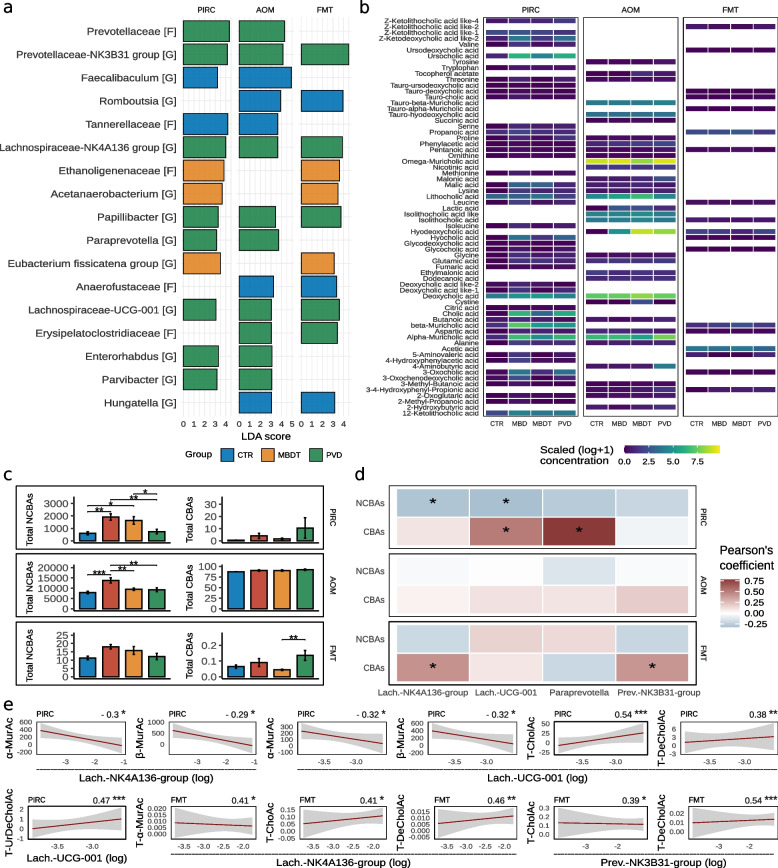

Additionally, we conducted LEfSe analysis to identify taxonomic markers associated with each group (LDA > 3). Across the AOM, PIRC, and FMT models, a total of 83, 46, and 91 distinct taxonomic markers were identified, respectively (Supplementary Fig. S8). While each model showcased its unique taxonomic signature, shared taxonomic marker-group associations were observed, indicating “taxonomic convergence” (Fig. 7a). Notably, 17 bacterial markers were identified across at least two of the three models exclusively, associated with the same diet/FMT groups (Fig. 7a). For instance, Faecalibaculum, Romboutsia, and Hungatella were associated with the CTR. The MBDT group had Acetanaerobacterium and Eubacterium fissicatena group as exclusive markers, while the MBD group had none. Interestingly, the PVD group exhibited the most numerous taxonomic markers, including Prevotellaceae NK3B31 group, Lachnospiraceae NK4A136 group, Lachnospiraceae UCG-001, Papillibacter, Paraprevotella, Enterorhabdus, and Parvibacter, representing over 50% of the shared markers.

Fig. 7.

Specific taxonomic and metabolic profiles associated with different dietary treatments in PIRC, AOM, and FMT models. a Barplot outlines the taxonomic markers associated with each group, identified through LEfSe analysis, and detected exclusively in at least two different experimental models within the entire dataset. Linear discriminant analysis (LDA) scores are presented on the x-axis, while the taxonomic assignments of markers are indicated on the y-axis. Group-related taxonomic markers are colour coded as per the legend. b A heatmap depicting the distribution of metabolite concentrations detected using targeted quantitative analysis in PIRC, AOM, and FMT models. The heatmap illustrates metabolite concentrations that exhibit significant changes among sample groups (Kruskal–Wallis test, p < 0.05). Metabolite concentrations are reported with a log + 1 transformation and are indicated by a colour gradient. c Barplot reports the total amount, expressed as µmol/L, of nonconjugated bile acids (NCBAs) and conjugated bile acids (CBAs), significantly different within dietary groups (b), in the three animal models. Differences between groups are tested using Tukey HSD test, and significant comparisons are highlighted using asterisks (*p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001). d Heatmap reports correlations between NCBAs or CBAs and the relative abundance of four representative bacterial genus selected by PVD in at least two different animal models (a). Pearson’s correlation coefficient is reported with colour gradient, while significant correlations are reported using asterisks (*, from p < 0.05 to p < 0.001). e Scatter plots report the correlation trend between specific NCBA or CBA and representative bacterial genera within the four genera tested in d. The y-axis reports metabolite concentration (µmol/L), while x-axis reports the logarithm of bacterial relative abundance. Animal model and Pearson’s coefficients are reported above each panel. Significant correlations are reported using asterisks (*p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001), and bacterial genera are reported using the following abbreviations, Lach-NK4A136-group, Lachnospiraceae NK4A136 group; Lach-UCG-001, Lachnospiraceae UCG-001; Prev.-NK3B31-group, Prevotellaceae NK3B31 group. Metabolites in e are reported using the following abbreviations: α-MurAc, α-muricholic acid; β-MurAc, β-muricholic acid; T-CholAc, taurocholic acid; T-DeCholAc, taurodeoxycholic acid; T-UrDeCholAc, tauroursodeoxycholic acid; T-α-MurAc, tauro-α-muricholic acid

Taxonomic changes induced by the different diets lead to distinctive metabolic profiles in faeces

To comprehend the metabolites generated by bacterial communities in the specific context, metabolomic analysis was conducted on faecal samples, identifying specific metabolites associated with the four diets in the three different models.

LC–MS/MS untargeted screening of polar metabolites (annotation levels 1 and 2a, see the “ Methods” section) revealed distinct molecular effects influenced by the different diets. In the AOM model (Supplementary Fig. S9), the x-axis dendrogram distinguished the CTR diet from the two meat-based diets. Notably, PVD was characterised by blue-labelled polyphenols and polyphenol metabolites, which were positioned in the lower-left corner of the y-axis dendrogram. In PIRC rats (Supplementary Fig. S10), no specific dietary clustering was observed, despite a higher number of identified compounds. Both the metabolite and diet dendrograms exhibited puzzling profiles.

In the FMT model (Supplementary Fig. S11), the metabolite pattern outlined a clear clustering between MBD + MBDT and CTR + PVD groups, highlighting the impact of meat on microbial metabolites, regardless of tocopherol presence. MBD promoted acetylation and methylation, particularly in N- and O-acetylated amino acids and 5-methylcytosine.

Furthermore, untargeted LC–MS/MS data were analysed through discriminant analysis and volcano plot. In the AOM model, a prevalence of polyphenols was observed in PVD, while MBD and MBDT diets exhibited significantly higher concentrations of tryptophan metabolites, exemplified by 3-indole acetic acid and kynurenic acid responses (Supplementary Fig. S12).

In the PIRC model, hypoxanthine, inosine, and xanthosine were the key markers distinguishing PVD and CTR from MBD and MBDT (Supplementary Fig. S13). Interestingly, the differential analysis between PVD and MBD showed a significant increase of bile acids (deoxycholic acid, hyodeoxycholic acid, hyocholic acid, and muricholic acid), as well as carnitine and butylcarnitine, in MBD compared to PVD (Supplementary Fig. S13c). Similar differences were observed when comparing PVD with MBDT, with an increase of deoxycholic acid, hyodeoxycholic acid, carnitine, and its derivatives in MBDT (Supplementary Fig. S13d).

In the FMT model, we identified specific PVD biomarkers such as 4-coumaric acid, salicylic acid and histidinol, representing primary markers of plant-based products (Supplementary Fig. S14). Comparisons of PVD with MBD and MBDT revealed a notable increase of histidinol and 4-imidazoleacrylic acid (a marker of histidine deamination) in the former diet, along with tryptophan metabolites like 5-hydroxyindole acetic acid, tryptamine, and kynurenic acid in PVD compared to the two meat-based diets (Supplementary Fig. S14c, d).

Finally, targeted analytical methods were used to quantitatively determine differences in bile acids (conjugated and nonconjugated bile acids: CBAs and NCBAs, respectively), amino acids, and short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs) using authentic reference standards. Concentration differences in metabolites were assessed through the Kruskal–Wallis test (Fig. 7b), and metabolites showing significant differences among groups were further analysed through pairwise comparisons (Supplementary Figs. S15, 16, 17).

In the AOM model, 35 compounds significantly varied among different dietary groups (Supplementary Fig. S15). Bile acids such as muricholic acids (in ⍵- and α-form), hyodeoxycholic acid, and deoxycholic acid were present. The most abundant was ⍵-muricholic acid, a secondary bile acid significantly higher in the MBD group than in MBDT and PVD counterparts. α-muricholic was also higher in MBD, while hyodeoxycholic and deoxycholic acids were significantly lower in CTR. Considering the sum of all NCBAs, a significant comparison was evident for the MBD group compared to the MBDT, CTR, and PVD groups (Fig. 7c). CBAs levels were similar among groups (Fig. 7c). Tocopherol acetate was exclusively detected in MBDT, likely due to tocopherol metabolism, with its antioxidant properties preventing degradation or promoting the accumulation of alanine and lactic acid in faeces.

In the PIRC model, 43 compounds exhibited significant variations among the different diets (Supplementary Fig. S16). Notably, bile acids (α- and β-muricholic acids, deoxycholic acid, deoxycholic acid isomers, glycodeoxycholic acid, Z-ketolithocholic acid, and its isomers) as well as amino acids and their derivatives (glutamic acid, glycine, isoleucine, propionic acid, 2-methyl-propanoic acid, and butanoic acid) displayed higher concentrations in the MBD and MBDT groups compared to the PVD one. Considering the sum of all nonconjugated BAs (NCBAs), the MBD and MBDT groups showed a significantly higher level of total NCBAs compared to the CTR and PVD groups, while no significant differences were evident for conjugated bile acids (CBAs) (Fig. 7c). CBAs levels were similar among different groups.

In the FMT model, only 16 compounds showed significant differences among sample groups (Supplementary Fig. S17). β-muricholic was the most abundant bile acid, with higher levels in rats transplanted with MBD- and MBDT-derived faeces than in those transplanted with the PVD- or CTR-related counterparts. No significant differences in total NCBAs were present, while total CBAs levels were higher in PVD than in the MBDT group (Fig. 7c). In the PVD-derived group, a notable decrease in propionic acid and pentanoic acid was observed with respect to the corresponding MBD and MBDT groups and a higher 5-aminovaleric acid concentration compared to all other groups.

We evaluated correlations of total NCBAs and CBAs levels with the four bacterial genera belonging to the Lachnospiraceae and Prevotellaceae families, selected by the PVD diet in at least two of the models (Fig. 7a), i.e. Lachnospiraceae NK4A136 group, Lachnospiraceae UCG-001, Paraprevotella, and Prevotellaceae NK3B31 group. In the PIRC model, negative correlations were evident between NCBAs level and both Lachnospiraceae NK4A136 group and Lachnospiraceae UCG-001 genera, while positive correlations were evident between CBAs and Lachnospiraceae UCG-001 and Paraprevotella genera (Fig. 7d). In the FMT model, positive correlations between CBAs and the Lachnospiraceae NK4A136 group and Prevotellaceae NK3B31 group genera were evident (Fig. 7d). The specific correlations of the individual compounds within the NCBAs and CBAs categories were reported in Fig. 7e.

We also used environmental fitting regression analysis to explore metabolite-bacterial profile relationships. In the AOM model, significant correlations (refer to environmental fitting analysis) were found between bacterial diversity and 23 metabolites, while the FMT model showed one such correlation with 2 compounds (Supplementary Fig. S18). No significant correlations were found in the PIRC model.

Discussion

Our research analysed how different diets, each linked with differing risks of colorectal cancer, influence both colon cancer development and the gut microbiota. Our aim was to uncover a direct connection between diet-influenced microbiota and cancer susceptibility. What we found was striking: the pesco-vegetarian (PVD) diet exhibited a notably diminished potential for tumour formation compared to the other dietary groups in all three experimental models.

In PIRC rats, the PVD significantly reduced spontaneous tumorigenesis; in the parallel AOM model, the precancerous lesions MDF in the PVD and CTR groups exhibited fewer crypts, compared to the meat-based diet (MBD) group, which were indicative of a lower growth of these lesions with the PVD. These results suggested a protective effect of PVD against CRC and, in the AOM model, a potential tumour-promoting effect of MBD, not evident in the PIRC rats. The disparity between the two models might be explained by the Apc mutation in PIRC rats, which is a potent driver of tumorigenesis that could mask the promotion effect of MBD [15, 17]. Conversely, in the AOM model, with a weaker stimulus for tumorigenesis, the promoting effect of MBD may be more apparent, alongside the lower tumorigenesis in the PVD group.

Importantly, when the faeces of PIRC rats fed the four different diets were transplanted into GF animals which were subsequently initiated with AOM, those receiving the MBD-associated faeces developed more preneoplastic lesions than those receiving the PVD-associated faeces, even more than those receiving the MBDT-associated faeces, demonstrating the ability of gut microbiota to convey risk factors linked to the diet. These findings also confirmed the PVD diet’s protective role and suggest a protective effect of α-tocopherol, which was not evident in the PIRC carcinogenesis experiment, possibly due to the strong effect of Apc mutation, as discussed above.

In PIRC rats fed PVD, apoptosis levels were higher than in the MBD group, suggesting a mechanism like that associated with the cancer preventive effect of fish-derived ω3-lipids [33]. Although the fish we fed to our rats (codfish) is not particularly high in lipids, we could speculate that the observed effects may be partly due to the surplus of ω3-lipids content. Inflammation potentially promotes carcinogenesis [34], and in AOM rats fed PVD, CD68 expression and myeloperoxidase activity were lower compared to the MBD counterpart. Moreover, lower levels of IL-6 and TNF-α in the colon of PIRC rats fed PVD were also indicative of a mild anti-inflammatory effect, like fish oils [9]. Furthermore, PVD maintained a healthy intestinal permeability, acting as a protective barrier against inflammatory triggers [34, 35]. Regarding lipid peroxidation and oxidative stress-related biomarkers, in both experimental models, PVD-fed rats showed lower values than those experiencing MBD diets, potentially contributing to PVD protective effect against carcinogenesis, consistent with prior findings [6, 7, 36].

Our previous studies [5, 7, 37] indicated that α-tocopherol added during the pork meat curing process inhibits rat colon carcinogenesis and normalises urinary DHN-MA. Consistent with these previous reports, in the AOM model fed MBDT, urinary DHN-MA levels were slightly lower than in the MBD group. In parallel, faecal TBARS and HNE concentrations, markers of lipid peroxidation, were slightly but not significantly lower in the MBDT group than that in the MBD one. Along with the lower carcinogenicity of MBDT-derived faeces observed in the FMT experiments, these findings suggested a protective effect of α-tocopherol, which might require higher doses for a more pronounced effect. Moreover, in our study, α-tocopherol was added directly to the powdered component of the diet, and not during the curing process.

Our study highlighted the significant impact of the diet on microbial composition, which was evident after 3-month treatments across all three models (AOM, PIRC, and FMT). During this period, substantial changes in microbiota composition occurred, highlighting the gut microbiota’s adaptability and responsiveness to dietary changes and confirming its plasticity, as previously demonstrated [38]. At 3 months, α-diversity measures revealed significant differences, with the PVD group in the AOM model displaying higher diversity than the MBD/MBDT groups, a result aligning with previous studies in PIRC rats on a spinach-rich diet [39] and with evidence on healthy subjects consuming fish [13].

β-diversity analysis also demonstrated substantial diet-driven microbial composition shifts, with a stronger impact seen in the AOM model, particularly after 3 months. Note that we also observed significant differences in β-diversity between the AOM and PIRC models at the beginning of the experiment, i.e. at time T0, highlighting the different microbiota of these two different animal models as previously reported [23]. Therefore, our observation that, despite the different structure of the starting microbiota, the dietary treatments determine a selection of specific bacterial communities which is shared across different models points out to the central effect of diet in selecting specific communities and corroborates the protective effect of PVD diet in the three animal models.

In the FMT study, distinct patterns in bacterial β-diversity emerged at various time points (T0, T1, T3) according to the faecal donor’s diet. Notably, while no significant distinctions were found between the MBD and MBDT groups at T0 and T1, a significant separation between these two groups was observed after 3 months (T3) and was associated with differential CRC risk. Accordingly, in the FMT experiment, not only the PVD-derived faeces but also those derived from the MBDT group were able to reduce the number of preneoplastic lesions, an effect in contrast with the negative impact on colon tumorigenesis observed with the MBD-derived faeces.

LEfSe analysis revealed unique taxonomic profiles for each dietary group. Shared markers linked CTR to Faecalibaculum, Romboutsia, and Hungatella, while Acetanaerobacterium and Eubacterium fissicatena group were associated with the MBDT group. The PVD group across all models displayed significant markers, including Prevotellaceae NK3B31 group, Lachnospiraceae NK4A136 group, Lachnospiraceae UCG-001, Papillibacter, Paraprevotella, Enterorhabdus, and Parvibacter. Plant-based diets have already been associated with increased Prevotellaceae NK3B31 group, known for its positive effects on metabolism and growth [40, 41]. A previous study in PIRC rats harbouring different microbiota [42] also showed an association between relative abundance of Prevotella copri and decreased tumour burden. Lachnospiraceae NK4A136 group, a potential probiotic genus [43], is reduced in mice fed red meat which, in line with our report, showed an impairment in colon barrier integrity and more inflammation [44]. In addition, Lachnospiraceae NK4A136 group has been recently shown to be increased by plant lipids [45]. Lachnospiraceae UCG-001 was previously associated with carbohydrate metabolism and fermentation [46]. Papillibacter and Paraprevotella, both PVD markers, are known butyrate producers and have been proposed as “microbiomarkers” of intestinal health in patients with inflammatory bowel diseases [47]. Enterorhabdus, also more prevalent in PVD-fed animals, was shown to metabolise polyphenols, including ellagic acid and isoflavones [48] and dietary lignin [49]. Parvibacter has also been recently suggested to be beneficial [50] since its presence, in mice fed polysaccharides, is associated with improved insulin resistance, reduced inflammation, and amelioration of the lipid profile.

Regarding the faecal metabolites, in all three models, nonconjugated bile acids (NCBAs) were the significantly overrepresented metabolic class. Epidemiological and experimental studies have shown a strong link between faecal BAs and an elevated risk of CRC [34, 51]. BAs can promote tumorigenesis by acting as surfactants on the mucosa, leading to increased cell turnover and proliferation [52, 53]. Red meat or processed meat-based diets, rich in lipids, can stimulate BAs secretion in the intestine, potentially increasing CRC risk [2]. Notably, fish ω-3 fatty acids do not impact luminal concentrations of secondary bile acids, in contrast to saturated and ω-6 fatty acids [9]. It is also interesting to note that in a study performed in Apc-mutated mice fed deoxycholic acid [54], the faecal microbiota transplant to the recipient group of Apc-mutated mice increased intestinal carcinogenesis, according to our study. Therefore, the increased faecal BAs, in the MBD diet, especially secondary BAs, may contribute to the carcinogenic outcome observed in our study. Interestingly, considering the sum of all NCBAs, in both the PIRC and the AOM models, we observed a significantly higher level in the MBD group than in the CTR and PVD, while no significant differences were evident for CBAs whose level, as expected, was much lower respect NCBAs. At least in the PIRC model a significant inverse correlation between several bacterial genera belonging to the Lachnospiraceae and Prevotellaceae families (representative of the PVD group) and total NCBAs was present, suggesting a potential mechanism of action for the protective effect of these genera against CRC.

Our data demonstrate the importance of associating faecal metabolic changes with taxonomic changes in the microbiota in order to elucidate the various CRC biomarkers across different dietary groups. It was therefore particularly interesting to identify diet-related patterns of microbiota-metabolite association within the natural variability inherent to the different models. In this regard, we observed crucial evidence essential for understanding the link between diet, microbiota, metabolic variations, and modulation of CRC risk. As mentioned earlier, regardless of the animal model considered, the PVD selected four bacterial genera (Prevotellaceae NK3B31 group, Lachnospiraceae NK4A136 group, Papillibacter, and Lachnospiraceae UCG-001), thus identified as biomarkers in all three models. Intervention trials highlighted the Mediterranean diet’s role in selecting the genus Lachnospiraceae NK4A136 group, associating it with a reduction in metabolic risk markers and a decrease in bile acid levels in subjects with metabolic syndrome [55]. In PIRC rats, we observed a negative correlation between the two genera Lachnospiraceae NK4A136 group and Lachnospiraceae UCG-001 with two different NCBAs, α-muricholic acid and β-muricholic acid. Interestingly, in the FMT experiment, although the direct taxa-metabolite correlation was no longer evident, β-muricholic acid (NCBA) levels were significantly higher in the two MB groups (MBD and MBDT) compared to the CTR and PVD groups. Moreover, in the FMT rats, as reported in PIRC rats, we observed significantly higher levels of β-muricholic acid and 3-oxocholic acid in the MBD group. Additionally, in the FMT rats, a distinct effect was observed, characterised by the positive correlations between Prevotellaceae NK3B31 group, Lachnospiraceae NK4A136 group, and CBAs. However, the very lower concentration of CBAs requires cautious interpretation to avoid misinterpretations.

While BAs represented the key metabolic class significantly over-represented in the MBD-fed rats belonging to all the animal models here investigated, polar and semipolar metabolites showed specific metabolic patterns, especially in the AOM and FMT models. Furthermore, the accumulation of faecal polyphenols, such as protocatechuic acid, gentisic acid, 4-vinylphenol, and 4-coumaric acid in the PVD group, was coherent with the intake of vegetable products and fibres, consistent with faecal comparative metabolomic studies on vegans and omnivores [56]. We hypothesised an interconnection between the production of these metabolites, inflammation status influenced by antioxidant compounds and the prevalence of specific microbiota genera as Prevotellaceae NK3B31 group, Lachnospiraceae NK4A136 group, and Papillibacter, which may be modulated by polyphenols in PVD [57].

Conversely, we also observed that faecal polyphenol concentration was lower in the MBD, MBDT, and CTR groups, leading to metabolite production shifts towards amino acid metabolites, simple sugars, nucleic acids, purine nucleosides, carnitine, and their acetylated and methylated derivatives [58]. In PIRC and FMT models, 5-methylcytosine was under-represented in PVD when compared to MB diets. This metabolite has been studied as a marker of the DNA methylation, a process altered during colorectal carcinogenesis [59]. Interestingly, a report studying faecal metabolites and microbiota in healthy elderly subjects found that 5-methylcytosine, together with other metabolites associated with age-related diseases, was enriched in elderly type gut microbiota and characterised by increased intestinal permeability [60], suggesting, in agreement with our data, that low levels of this metabolite are associated with a lower CRC risk. Specific compounds like hypoxanthine, inosine (hypoxanthosine), and xanthosine markedly differentiated PVD and CTR from MBD and MBDT, as in the case of the PIRC model. Furthermore, we observed the prevalence of compounds like methionine, tryptophan, and histidine metabolites in CTR and MBD, consistent with observations in humans consuming bovine meat [61]. When comparing the metabolite profiles in AOM and FMT, we spotted similarities in the increase of indole ring accumulation in the corresponding MBD groups, with higher concentration of indole-3-acetic acid, kynurenine, and indole 3-lactic acid, which suggested an enrichment of compounds formed in tryptophan degradation pathway. We also document that carnitines and their acetylated and methylated forms were over-represented in the MBD group compared to the PVD one, a result that was evident also in the PIRC model. Carnitine, like other compounds present in red meat, can be converted by gut microbiota into trimethylamine which, once absorbed, is transformed into trimethylamine-N-oxide (TMAO) in the liver [62, 63]. TMAO concentration, especially in the serum, has already been correlated with CRC risk, but preformed TMAO is also present in seafood and fish [64], which may explain why in the AOM model TMAO was over-represented in the PVD group. On the contrary, in the FMT experiment, TMAO had an opposite trend, being highly represented in the MBD- and MBDT-associated groups compared to those derived from PVD faeces.

Conclusions

Our results highlight, for the first time, a strong protective effect on colon tumorigenesis of a fish- and spinach-based diet and confirmed the potential carcinogenicity of a red and processed meat-based diet, effects associated with variation in specific CRC biomarkers as apoptosis, inflammation, intestinal permeability, and oxidative stress. Importantly, the faecal microbiota transplant experiment clearly establishes a causal role of diet-shaped microbiota in CRC risk, demonstrating the strong protective effect of the gut microbiota associated with PVD, and the harm of that associated with MBD. The negative correlation between NCBAs and bacterial genera belonging to the Lachnospiraceae and Prevotellaceae families, abundant in the PVD diet, suggests a connection between changes in bacterial and metabolic profiles. Although previous studies have reported that risk factors for colon cancer may be transmitted by the faecal microbiome [54, 65], this is the first study demonstrating that diet-associated cancer risk can be transmitted through faeces. This underscores the significance of faecal microbiota and its metabolites in conveying diet-related risk factors for colon cancer. Further research should aim to understand the molecular mechanisms and explore dietary interventions to prevent colon cancer in high-risk individuals.

Supplementary Information