Abstract

Background

Policymakers across countries promote cross-sector collaboration as a route to improving health and health equity. In England, major health system reforms in 2022 established 42 integrated care systems (ICSs)—area-based partnerships between health care, social care, public health, and other sectors—to plan and coordinate local services. ICSs cover the whole of England and have been given explicit policy objectives to reduce health inequalities, alongside other national priorities.

Methods

We used qualitative methods to understand how local health care and social services organizations are collaborating to reduce health inequalities under England’s reforms. We conducted in-depth interviews between August and December 2022—soon after the reforms were implemented—with 32 senior leaders from NHS, social care, public health, and community-based organizations in three ICSs experiencing high levels of socioeconomic deprivation. We used a framework based on international evidence on cross-sector collaboration to help analyse the data.

Results

Leaders described strong commitment to working together to reduce health inequalities, but faced a combination of conceptual, cultural, capacity, and other challenges in doing so. A mix of factors shaped local collaboration—from how national policy aims are defined and understood, to the resources and relationships among local organizations to deliver them. These factors interact and have varying influence. The national policy context played a dominant role in shaping local collaboration experiences—frequently making it harder not easier. Organizational restructuring to establish ICSs also caused major disruption, with unintended effects on the partnership working it aimed to promote.

Conclusions

The major influences on cross-sector collaboration in England mirror key areas identified in international research, offering opportunities for learning between countries. But our data highlight the pervasive—frequently perverse—influence of national policy on local collaboration in England. National policymakers risked undermining their own reforms. Closer alignment between policy, process, and resources to reduce health inequalities is likely needed to avoid policy failure as ICSs evolve.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12889-024-20089-5.

Keywords: Health Policy, Intersectoral Collaboration, Health Care Reform, Health Inequalities, Qualitative Research

Background

Cross-sector collaboration between health care, social services, and other sectors is widely promoted as a route to improving population health [1–3]. The idea is that coordinated action is needed to tackle complex health challenges that extend beyond organizational boundaries, such as preventing obesity or improving services for people with multiple health and social care needs. In England, policymakers recently overhauled the structure of the NHS to embed cross-sector collaboration at a local level [4, 5]. Since July 2022, England’s NHS has been formally divided into 42 integrated care systems (ICSs)—area-based partnerships between the NHS, social care, public health, and other agencies, covering populations of around 500,000 to 3 million—responsible for planning and coordinating local services to improve health and care [6]. Similar policies are being pursued in other UK countries and internationally [7, 8]. For example, in the US, federal policymakers are testing Accountable Health Communities to join up health care and social services [9], while state Medicaid reforms in Oregon, Washington, and elsewhere focus on developing regional cross-sector partnerships to improve health and health equity [10, 11].

A major aim of England’s new ICSs is to reduce health inequalities. ICSs have been given four ‘core purposes’ by national policymakers, including to ‘tackle inequalities in outcomes, experience, and access’ [12]. NHS leaders have identified broad priorities to guide ICS action, such as target groups for interventions to reduce health care inequalities, [13, 14] and provided modest additional funding to support local efforts [15]. But the task facing ICSs is substantial: inequalities in health outcomes between richer and poorer areas in England are wide, [16, 17] and there are persistent gaps in access to high quality health care [18–20]. Local government agencies in England—responsible for social care, public health, and other services that influence health—have faced deep cuts since 2010, with funding falling furthest in poorer areas [21–23]. ICSs are also expected to deliver other high-profile policy objectives, including improving quality and efficiency in the NHS and reducing long waiting lists for hospital treatment [12, 15].

Making cross-sector collaboration work has proved a persistent challenge. ICSs build on a long history of policies encouraging local collaboration to improve health and reduce health inequalities in England [24]. Local health partnerships have been developed in diverse national contexts for decades—including in Europe, North America, and elsewhere [25–27]. Yet there is little high quality evidence to suggest that collaboration between local health care and non-health care agencies improves health or health equity [28]. Meanwhile, a large body of evidence describes the mix of factors that can hold back effective collaboration—including competing organizational agendas, resource gaps, communication issues, power imbalances, and more [28]. To make things harder, policy initiatives to tackle health inequalities are frequently ambiguous, underfunded, and undermined by other short-term political objectives [29–32].

Whether England’s new ICSs can overcome these challenges and meet policymakers’ expectations is yet to be seen. ICSs have existed informally for several years, but only recently gained formal powers from central government. Each ICS is made up of a new NHS body and wider committee of NHS, local government, and other agencies. Studies have focused on the emergence of ICSs prior to their formal establishment in 2022, including analysis of early ICS plans and planning processes, [33–35] experiences during the pandemic, [36, 37] and evolving governance and decision-making processes [38, 39]. Olivera et al. analysed early ICS plans and found vague and inconsistent conceptualization of health inequalities, and lack of commitment to concrete action [33]. Our previous research focused on ICS interpretations of policy aims on health inequalities [40]. But in-depth understanding of how ICSs are collaborating to reduce health inequalities is lacking—as is data on the implementation of ICSs since the 2022 reforms. We conducted qualitative research with senior NHS, public health, social care, and other leaders in three more socioeconomically deprived ICSs to understand local experiences of collaboration to reduce health inequalities in England. We focus on how the NHS is working with other sectors beyond health care to reduce health inequalities, and analyse factors shaping cross-sector collaboration across key domains identified in the international literature [28]. We use theory on public policy implementation to help interpret the results, drawing on Exworthy and Powell’s concept of ‘policy streams’ and their alignment at multiple levels [41–43]. Our findings can inform future policy on cross-sector collaboration to improve health and reduce health inequalities in England and beyond.

Approach and methods

Study design and sample

We conducted a qualitative study of how local health care and social services organizations are collaborating to reduce health inequalities under NHS reforms in England. Our sample included 32 leaders from NHS, social care, public health, and community-based organizations in three ICSs.

We identified a purposive sample of ICSs with varied characteristics all experiencing high levels of socioeconomic deprivation (defined using the index of multiple deprivation—an official measure of relative deprivation for small areas in England that combines a mix of data on income, employment, education and skills, health, crime, barriers to housing and services, and living environments). To do this, we collated publicly available data on the characteristics of England’s 42 ICSs, [6] including their geography, population size and deprivation, organizational complexity, and policy context (Table 1). We selected these characteristics because of evidence on their likely role in shaping how health care and other organizations in ICSs work together to reduce health inequalities [6, 28]. For example, differences in organizational governance and decision-making can hold back effective collaboration, [28] and these challenges may be exacerbated when a greater number of organizations are involved in local partnerships [31]. We used these data to identify a sub-group of ICSs experiencing the highest concentration of socioeconomic deprivation relative to other ICSs in England (the top tercile of ICSs with the highest concentration of local areas in the most deprived 20% of areas nationally). National NHS bodies are aiming to reduce health inequalities by targeting efforts on the most deprived population groups (the 20% most deprived of the population) [13]. ICS leaders in these areas are likely to be particularly aware of their role in reducing health inequalities, and ICSs with similar levels of socioeconomic deprivation may pursue some common approaches. Understanding the experiences of ICSs in these areas is therefore important to inform policy and practice in England.

Table 1.

ICS characteristics used to guide case study sampling

| For each of England’s 42 ICSs, we collated data on [6]: | |

|---|---|

|

- Socioeconomic deprivation—the proportion of lower super output areas (LSOAs) in the most deprived 20% of areas nationally, using index of multiple deprivation (IMD) ranks - Geographical context—including NHS region and proportion of rural/urban areas - Population size—the NHS registered population - Organizational complexity—including the number of NHS trusts and upper tier local authorities - Policy context—including the number of sites involved in relevant recent policy initiatives within the ICS (new care model ‘vanguards’[44] and integrated care and support ‘pioneers’[45]) and date the early version of the ICS was created (NHS England established ICSs in ‘waves’ based on their perceived maturity, [46] before all ICSs were formally established under legislation in July 2022) |

Within this sub-group of high deprivation areas, we identified three ICSs that varied in population size (which is strongly correlated with organizational complexity), geographical region, rurality, and recent policy context—for example, by avoiding selecting all three sites from the same region of England, or with a similar policy context and history of cross-sector collaboration. This gave us a relatively heterogenous mix of three ICSs all serving more socioeconomically deprived populations in England (Table 2). ICS leaders from the three areas we selected all agreed to participate in the study.

Table 2.

Selected case study characteristics compared to all ICSs

| Socioeconomic deprivation | Geographical context | Population size | Policy context | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ICS A | High | Mixed | Large | Earlier ICS wave, high involvement in relevant policy initiatives |

| ICS B | High | Urban | Medium | Later ICS wave, moderate involvement in relevant policy initiatives |

| ICS C | High | Urban | Large | Later ICS wave, high involvement in relevant policy initiatives |

For socioeconomic deprivation, we defined ‘high’ deprivation as the top tercile of ICSs with the highest concentration of local areas in the most deprived 20% of areas nationally. For geographical context, we divided ICSs into terciles based on the proportion of local areas in each ICS classified as urban by the Office of National Statistics. We defined ICSs in the middle tercile as ‘mixed’ (74–87% urban areas), and ICSs in the top tercile ‘urban’ (87–100% urban areas). For population size, we divided ICSs into terciles based on their NHS registered population. We defined ICSs in the middle tercile as ‘medium’ (1.1 m-1.7 m), and ICSs in the top tercile ‘large’ (1.7 m-3.1 m)

ICSs are complex systems involving various organizations and organizational partnerships. The NHS’s new ICSs are themselves made up of two linked bodies: integrated care boards (ICBs—area-based NHS agencies responsible for controlling most NHS resources to improve health and care for the ICS population), and integrated care partnerships (ICPs—looser collaborations between NHS, local government, and other agencies, responsible for developing an integrated care plan to guide local decisions, including those of the ICB). ICSs are expected to deliver their objectives through the work of both bodies and other local agencies [12, 47]. This includes additional local partnerships between the NHS, local authorities, and other relevant organizations at a ‘place’ level within each ICS—smaller geographical units, often based around local authority boundaries (most ICSs include multiple local authority areas). NHS England and other national bodies are responsible for overseeing and managing the performance of ICSs—for instance, by setting targets, monitoring progress, and assessing performance. Over recent decades, the approach of national NHS bodies to driving improvement in the health system has typically relied on top-down targets and performance management [48, 49]. More broadly, the English NHS is a centralized health system with strong political involvement [8]. In our research, we focused on overall experiences of collaboration on health inequalities across the ICS, including the relationship between action at different geographical levels.

In each ICS, we carried out in-depth interviews with senior leaders of NHS, local government, and other organizations involved in the ICS’s work on health inequalities. This included leaders from NHS ICBs (such as ICB chief executives and directors of strategy), NHS providers (such as NHS Trust chief executives and general practitioners), local authorities (such as directors of public health and adult social care), and other community-based organizations (such as leaders of charities working with the ICS to represent community interests or provide services)—as well as those involved in the day-to-day management of the ICS’s work on health inequalities. Participants were identified through web-based research and snowball sampling, [50] and contacted via email. Our sample included 17 leaders from the NHS (including those working in the NHS’s new ICBs) and 15 from public health, social care, and other sectors outside the NHS (Table 3). We describe all participants as ‘leaders’ when reporting the results.

Table 3.

Interviewee sectors

| NHS | Other sectors | Total | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ICB | Provider | Public health | Social care | Community | ||

| ICS A | 3 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 8 |

| ICS B | 3 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 9 |

| ICS C | 4 | 4 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 15 |

| Total | 10 | 7 | 7 | 5 | 3 | 32 |

Data collection and analysis

We used a semi-structured interview guide with questions on ICS aims and priorities, how ICS work on health inequalities is being led and managed, and factors shaping the experience of collaboration between the NHS and other sectors to reduce health inequalities (supplementary material file 1). The interview guide was designed to gain a broad understanding of the early development of ICS work on health inequalities, and was informed by our analysis of national policy on ICSs and existing literature on cross-sector collaboration [28]. Interviews were carried out online, lasted an average of 44 minutes, and took place between August and December 2022—soon after ICSs were formally introduced across England. One researcher (HA) carried out one interview with each research participant individually. All interviews were audio recorded, professionally transcribed, and anonymized at the point of transcription. Field notes were also made during the interviews. We asked interviewees to share relevant documents (such as draft ICS plans or papers describing relevant local initiatives) when they referred to them in their responses. Participants did not review interview transcripts or feed back on research findings.

We analyzed the data using the constant comparative method of qualitative analysis [50]. We reviewed the transcripts line by line to identify themes in the data and refined these themes iteratively as new concepts emerged. All authors (HA, NM, AH) reviewed a sample of the transcripts and worked collaboratively to develop the code structure. One author (HA) then analyzed all transcripts and the authors met regularly to discuss interpretation of the data and any changes to the coding framework. We used an integrated approach [51] to develop the code structure based on the themes identified in the data and broader evidence on factors shaping local collaboration between health care and non-health care organizations. Our recent umbrella review identified a mix of factors shaping cross-sector collaboration in five domains (Table 4) [28]. We used these domains as a conceptual framework to organize our analysis and help interpret the data. For example, our analysis identified cultural differences between the NHS and other sectors as a barrier to local collaboration, which we grouped alongside other factors linked to the broader theme of culture and relationships—one of the five domains identified in the literature. We used NVivo (release 1.3) to facilitate our analysis of the data. Where relevant, we accessed publicly available documents on ICS initiatives to cross-check examples mentioned by our interviewees. More detailed analysis of study data on local conceptualizations of national policy on health inequalities is reported elsewhere, [40] while this paper focuses on the overall research findings.

Table 4.

Factors shaping cross-sector collaboration identified in the international literature

| A recent umbrella review synthesized evidence on collaborations between local health care and non-health care organizations and factors shaping how they function. |

| The review included 36 studies (reviews) with evidence on varying forms of collaboration in diverse contexts: some included data on large organizational collaborations with broad population health goals, such as preventing disease and reducing health inequalities; others focused on collaborations with a narrower scope and focus, such as better integration between health and social care services. The study included data from the UK, US, and other countries and points to a mix of dominant factors in five interrelated domains: |

|

- Motivation and purpose—such as vision, aims, perceived impacts, and commitment to collaboration. For example, unclear aims or lack of commitment can hold back collaboration - Relationships and cultures—such as trust, values, professional cultures, and communication. For example, shared values and history of joint working can help organizations collaborate - Resources and capabilities—such as funding, staff, and skills, and how these resources are distributed. For example, lack of resources is commonly identified as a barrier to collaboration - Governance and leadership—such as decision-making, accountability, engagement, and involvement. For example, clarity on accountability is thought to help collaborations function - External factors—such as national policy, politics, and broader institutional contexts. For example, national policy changes can conflict with local priorities or disrupt existing relationships |

Results

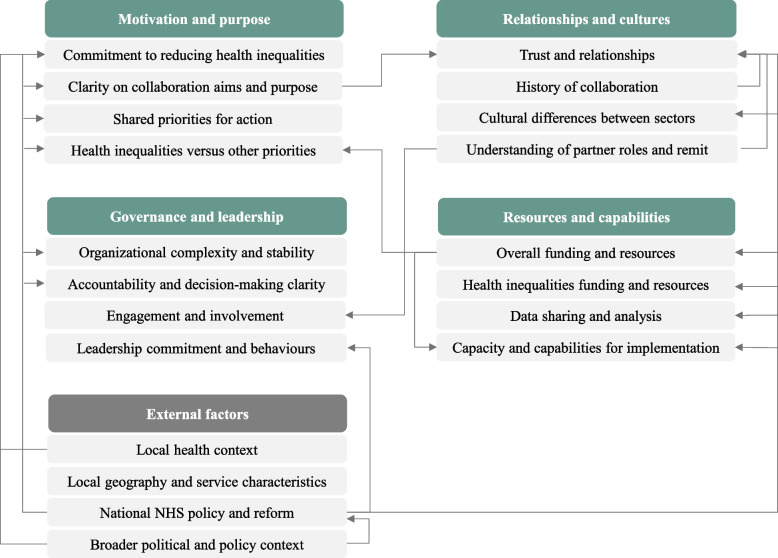

We identified a combination of factors shaping local collaboration between the NHS and other sectors to reduce health inequalities, spanning the five domains identified in the international literature (Fig. 1). These factors interact and have varying influence—and the national policy context in England played a dominant role in shaping local collaboration experiences across all five domains (Table 5).

Fig. 1.

Factors shaping cross-sector collaboration on health inequalities, and example interactions

Table 5.

Examples of the dominant role of national policy in shaping local collaboration experiences

| Domain | Influence of national policy |

|---|---|

| Motivation and purpose |

- ICSs given explicit policy objectives to reduce health inequalities - Vague national policy guidance contributes to lack of clarity on ICS aims and purpose - Overriding focus of national NHS bodies on other short-term policy priorities |

| Governance and leadership |

- Formal governance framework for ICSs defined by national policymakers - National accountability differences between NHS and local government creates tension - NHS restructuring causes organizational upheaval and leadership turnover |

| Relationships and cultures |

- NHS restructuring destabilizes local relationships and existing partnerships - Top-down, hierarchical approach of national NHS bodies can cause local conflict - Frequency of reform contributes to fatalism and scepticism about local partnerships |

| Resources and capabilities |

- Insufficient funding and resources can hold back what local partnerships can deliver - Short-term and limited health inequalities funding can constrain effective investment - NHS restructuring can create capacity or capability gaps and divert local resources |

Motivation and purpose

Interviewees generally described strong commitment among local leaders to work together to reduce health inequalities. The scale of the health challenges facing their community—exacerbated by the covid-19 pandemic and cost of living crisis—was often identified as a unifying force. For example:

‘Honestly, in [ICS A], we’re absolutely at the bloody table. I guess that’s the thing. I don’t care what agency you’re from. For us up here, it is unjust that our population is suffering so much.’ —Regional public health leader, ICS A.

‘So there’s a collective will because of what we’re facing—particularly, I think, exacerbated by the cost of living crisis’ —ICS leader, ICS B.

But this high-level commitment did not necessarily translate into shared priorities for action. Leaders’ interpretations of national policy objectives on health inequalities varied—both within and between ICS areas. Perceptions of the ICSs’ role in tackling health inequalities varied too, with leaders articulating different views on how far the ICS—and NHS agencies within them—should extend their focus beyond reducing health care inequalities (such as differences in access to care) to address the broader social and economic conditions shaping health inequalities (such poor housing conditions).

The result was often lack of clarity. Some leaders could point to broad objectives for their ICS on reducing health inequalities, such as reducing gaps in healthy life expectancy or improving care for specific population groups. Leaders often described how reducing health inequalities should be a cross-cutting objective throughout their ICS plans (‘it literally runs through everything, doesn’t it, this health inequalities work’). But others felt their ICS’s priorities on health inequalities were vague (‘I haven’t heard anything specific’) or under construction (‘a work in progress’)—and several said they were struggling to know where to start. For example, an ICS leader in ICS C described how: ‘well, it’s massively complex, it’s kind of in everything […], so how do you, kind of—and it’s so entrenched as well, and so multifactorial—how do you start to make headway?’. National policy guidance often contributed to this lack of clarity (see external context). Vague and varied perceptions of ICSs’ role also created potential for conflict between sectors (see relationships and cultures).

‘Crowding out’ health inequalities

A widespread challenge was prioritizing work on health inequalities. Despite local leaders’ strong motivation to reduce health inequalities, interviewees in every ICS described how short-term pressures in the NHS and social care, such as long waiting times for ambulances and hospital care, risked dominating the agenda. These short-term pressures tended to have a ‘crowding out’ effect:

‘If you think about the kind of health inequalities piece, it’s up there but it gets drowned out in the day to day’—ICS leader, ICS A.

‘So trying to get airtime at the same time as there being queues of ambulances outside the door, to take one example, it’s quite tricky […]. So there’s a great deal of lip service played to inequalities but forcing that into concrete action is often more difficult when the environment is so noisy.’—NHS provider leader, ICS C.

‘This is just one more priority amongst all of the other priorities in an environment where there is not enough money or people or stability. […] If you look at the pressure the NHS particularly is under in terms of the urgent emergency care, hospital discharges, ambulance waits… you know, it’s harsh.’—Local authority social care leader, ICS B.

Beyond short-term pressures, leaders pointed to a mix of other factors contributing to this crowding out effect, including insufficient resources (see resources and capabilities), the behaviour and focus of national policymakers, and organizational restructuring and uncertainty (see external context).

Governance and leadership

In all three ICSs, structures for governing and managing local work on health inequalities were still being developed. Establishing ICSs involved forming new NHS organizations, partnership committees, and decision-making processes—and often meant substantial upheaval. ICS leaders were seeking to do this in a complex organizational environment, involving multiple agencies (such as NHS providers and local authorities) and existing partnership bodies (such as Health and Wellbeing Boards, which bring together local authorities, NHS organizations, and other services to develop local health strategies). This required careful navigation. For instance, a leader in ICS A described how:

‘I have resisted the temptation to dive straight in, to say this is ICS or ICB led, because, actually, our local authorities have been at health inequalities for bloody decades. And we need to be really careful not to disrupt that ecosystem in an unhelpful way and alienate. So […] we’re working together at the moment to figure out how best we do this.’—ICS leader, ICS A.

Meantime, interviewees frequently described being unclear about how and where decisions related to health inequalities would be made. Some pointed to practical challenges making decisions in new ICS structures. For example, a leader in ICS A described how there were more than 50 people on their new integrated care partnership committee; ‘I mean, we can’t even be round a table, we have to meet cabaret-style. It’s really, really tricky.’ Some worried that their new partnership committee would lack ‘teeth’, with real power held by the NHS-led ICB (‘the health lot are going to steamroller them’). But a bigger challenge was defining the right balance of power and decision-making between different geographical levels in each ICS—particularly between ‘systems’ (across the whole ICS) and ‘places’ (smaller area-based partnerships within them, typically organized around local authority boundaries).

Place versus system

This tension was playing out in all three ICSs. Leaders across sectors emphasized the importance of place-level action on health inequalities—for instance, given the public health expertise in local government, longstanding local partnerships (such as Health and Wellbeing Boards), and close links with community-based groups at this more local level. Local authority leaders frequently highlighted that their primary focus and accountability lay locally too. For instance, a local authority public health leader in ICS C said: ‘to be honest, our accountability is to our local residents, and, whether ICB or ICP likes it or not, […] the decisions are made by the local politicians, not the ICS. We're not accountable to the NHS.’ Interviewees also stressed that differences in context within ICSs, which span varied geographical areas and diverse populations, meant place-level approaches were essential to effectively address health inequalities. A local authority public health leader in ICS B described how ‘the [ICS B] big broad-brush picture actually doesn't represent what [place X] looks like.’

Views on where this left system-wide action across the ICS varied. Leaders in ICS A, for example, talked about ensuring the ICS was ‘enabling, not dictating’ to local areas, at the same time as identifying issues where the ICS can ‘can do once and do better’ than places acting alone. In ICS C, ICS leaders described plans to develop the ICS’s capabilities to support local action on health inequalities—including data analytics, training and development, and communities of practice to identify and spread promising interventions—and suggested this might involve using a greater proportion of their NHS funding allocation for the ICS on system-wide initiatives in future. For some, ICSs also represented an opportunity to reallocate resources between areas—for instance, between more and less socioeconomically deprived ‘places’ in the ICS—to help address health inequalities.

Yet leaders frequently identified the tension between systems and places as a barrier to progress:

‘Because we haven’t got this clear demarcation yet between “this is [ICS C] wide, this is […] place”, there's a lot of, like, to’ing and fro’ing and duplication in the system […]. I feel like the fact that they still haven’t worked out this [ICS C]-local split is a massive barrier.’—Local authority social care leader, ICS C.

‘One of the barriers at times can be what I call the push–pull between place and system’—ICS leader, ICS A.

For some organizations, such as large NHS hospital providers—often spanning multiple places, and sometimes spanning multiple ICSs—this tension was having an impact on service planning:

‘We want to be raising equality in maternity services that we provide. The different boroughs may want to have different maternity services and different ways of delivering maternity services, and actually the tension therefore is how do we, as a large bureaucratic organisation with enormous overheads, deliver a flexible enough service that meets the needs across those [X] different boroughs, when the needs are actually quite diverse. […] That's something that we are literally scratching our heads over.’—NHS provider leader, ICS C.

Engagement and involvement

At all levels of the system, leaders described the importance of engaging the right individuals and organizations to make progress on health inequalities. For example, a leader in ICS A described ‘this constant round of work that we need to do, […] going back and checking with local places, constant engagement with our local authority chief executives, informing them of what we’re doing, keeping them happy so they can keep their politicians happy.’ This included engagement with groups outside the public sector. A leader in ICS C, for instance, talked about how they were designing their ICS governance to ensure involvement of people using services, so ‘we have as many service users with decision making voices around the table as the statutory sector’. In some areas, this appeared to be making a difference. For example, a local authority social care leader in ICS A said: ‘I've never known social care to be as actively pulled into this as we are currently. […] We’re delighted’.

But not all interviewees felt meaningfully involved in their ICS’s work. A local authority public health leader in ICS C, for example, talked about being invited to a series of ICS workshops by NHS leaders, but said ‘it’s like a tick-box; […] it’s engagement for the sake of it, rather than true engagement’. Leaders from community-based organizations in two ICSs described challenges engaging GPs and other NHS staff in their work—even when it was commissioned by NHS agencies. One said: ‘there are people who really should be speaking to us and should be having to speak to us who have just, you know, been really hard to pin down’. For some, a lack of understanding among NHS leaders of work in other sectors was one factor holding back effective involvement (see cultures and relationships). Lack of time and resources was another barrier (see resources and capabilities). For example, a local authority public health leader involved in developing ICS plans described how ‘you cannot co-design in a meaningful way a strategy between July and December with no funding’.

Leadership

Across sectors, interviewees in all ICSs emphasized the importance of senior leadership in enabling collaboration—for instance, by articulating the importance of tackling health inequalities and bringing local organizations together to do it. Different kinds of leaders appeared to matter in different sectors, such as clinical leaders in the NHS and political leaders in local authorities. The skills and experience of local authority Directors of Public Health and other public health leaders were often recognized as important within ICSs, including in bridging gaps between organizations and sectors (see resources and capabilities). On the flipside, leadership turnover—sometimes a direct result of organizational restructuring to establish ICSs (see external context)—was identified as a barrier to effective joint working. Beyond individual roles, interviewees emphasized the importance of ‘system leadership’—for instance, leaders across sectors making joint decisions—for collaboration to work. For one ICS leader, this meant ‘being humble in the NHS and knowing… it's almost, where do you play the leadership, the intellectual capacity, in the health and care leadership? […] For me, the intellectual capacity that deals with this most effectively is often in local government, not in health’. But leadership behaviours did not always match this approach in practice (see relationships and cultures).

Relationships and cultures

Whatever formal governance structures were emerging in ICSs, interviewees consistently described how trust and strong relationships between leaders and organizations were needed to make progress:

‘You can sit four people in a room from organisations, but if they have no knowledge of each other, don't trust and respect each other, you can have any memorandum of agreement, whatever you like, it's not going to work. You need humans with history, with respect, with trust.’—Primary care leader, ICS A.

Leaders pointed to a mix of factors that could foster these kinds of relationships, including shared aims, open communication, understanding of each others’ organizations, a positive history of joint working, and more. Leaders also often stressed that strong relationships take time and effort to develop. In some areas, interviewees thought relationships between leaders and organizations were already strong—particularly at a ‘place’ level and where organizations and leaders had a long track record of collaboration. The covid-19 response—often involving partnership working between the NHS, local authorities, and various community groups—was frequently thought to have strengthened local relationships, providing a platform for future collaboration. For example, an NHS provider leader in ICS C described how ‘relationships were built because of the need driven by covid, and we’re kind of just re-warming up those relationships to face this year’s pandemic, which is the cost of living crisis’.

But relationships were not strong everywhere. For some interviewees, motivation to collaborate among organizational leaders was not always backed up with the behaviours needed to make it a reality. For example, an NHS provider leader in ICS B said that local leaders had ‘a shared understanding about why we’re here and what our priorities ought to be’, but ‘our relationships aren’t always great in the how we go about it’. For several interviewees, NHS leaders in particular needed to adapt their behaviour to make ICSs work—shifting from more competitive to collaborative leadership styles. For example, a local authority public health leader in ICS B described the lack of collaboration between local NHS providers, saying: ‘you go to the chief exec’s meeting and, you know, some of the time they’re barely civil to each other, sometimes they’re absolutely not civil to each other’. Relationships could also be more challenging between ‘middle managers’ working on the detail of how services are funded or delivered between sectors—for instance, between NHS and local authority staff making decisions about funding services for people with complex health and social care needs.

In all ICSs, organizational restructuring to establish integrated care systems had harmed some local relationships (see external context). Leaders in local government and community-based organizations often talked about disruption of key relationships with the NHS—including loss of NHS staff from clinical commissioning groups (local NHS purchasing organizations that were abolished under the reforms to establish ICSs) with knowledge of their local context, not knowing who to go to for key NHS programs or issues, and having to establish relationships from scratch with new NHS staff.

Cultural differences

Differences in culture between the NHS and other sectors could also hold back collaboration. Leaders outside the NHS often talked about the NHS’s top-down, hierarchical culture, with a heavy focus on reporting upwards to national NHS bodies. This could skew ICSs’ focus towards high-profile national targets linked to hospitals. But it could also conflict with ways of working in other sectors—and often contributed to a perception that NHS organizations expected others to adapt to fit their needs:

‘I think the top-down approach to doing things that the NHS has is a barrier. They fixate on counting beans not things that are making a difference to people's lives. […] I’ve had several conversations with people in the NHS that NHS E[ngland] need to know this by four o’clock today. I'm like, “well, that’s really nice but I don't work for NHS E[ngland], so I don't care”. And they don’t get that way of working because local authorities don’t work that way. […] There isn’t a national top-down thing on councils. […] And to be able to do something quick and different on the ground when half of the partnership have that—“we need to get permission, we need to make sure, and then we need to report it ten times”—is sometimes quite difficult.’—Local authority social care leader, ICS C.

‘One function that we have to do within that [ICS health inequalities advisory group] is report on our progress on Core20PLUS5, because the NHS—and I’ve just been upfront with the DPHs [Directors of Public Health] and I just said, “look, the NHS is a top-down organisation, we’re different to you as local authorities, we will have to report our progress on the Core20PLUS5, so we just need to build that in, we just all need to accept that, that we’re going to have to do it.”’—ICS leader, ICS A.

For some, lack of understanding among NHS leaders about how other sectors work exacerbated these challenges. Some local government leaders, for example, talked about the NHS not understanding the social care sector and the diverse range of services provided beyond care homes. A community-based organization leader in ICS C talked about being ‘horrified by the lack of understanding’ among NHS leaders about the voluntary and community-sector—including the assumption that the sector was just about people volunteering in the community rather than organizations contracted to deliver a wide mix of local services. But some interviewees talked more positively about a growing understanding in the NHS about the skills and capabilities of other sectors. A local authority leader in ICS B, for instance, talked about how the ‘ICS dynamic’ was helping shift understanding among NHS staff:

‘For a lot of NHS people, they’re actually seeing what local government can do in a really practical way. […] So you can just see light bulbs going on when they go, “actually, gosh, there is someone here that can do this”. […] They can just see, actually, we get there is another way of doing this that might be better than seeing it all through the prism of primary care, community services and, you know, big hospitals. So I do think there’s a cultural shift going on which could be really valuable”—Local authority public health leader, ICS B.

Stepping on toes

Varied perceptions of the role of ICSs in tackling health inequalities created tension. Perceptions varied within areas and professional groups (see motivation and purpose). But several leaders—particularly from local government—wanted their ICS to focus primarily on reducing health care inequalities, and were concerned about NHS leaders in integrated care boards and other organizations misinterpreting their role and focus. One public health leader in ICS C, for example, talked about a ‘misconception’ that the NHS is now responsible for solving poverty through ICSs. Another described how the ICS should be ‘absolutely focused on healthcare inequalities as its first and foremost responsibility. Get the inequalities within the NHS, what’s in their grasp. They’re not going to solve poverty at an ICS level.’ Several leaders described a caricatured dynamic where NHS leaders appear to have ‘discovered’ health inequalities, and—as an NHS provider leader in ICS C put it—‘public health teams in particular just sort of go: “well, hello!?”’. Leaders described a mix of potential negative effects of this dynamic, including the NHS ‘stepping on toes’, failing to acknowledge others’ skills and expertise, and alienating local authorities with a long history of action to reduce inequalities.

Resources and capabilities

Lack of funding and resources was consistently identified as a major barrier to local efforts to reduce health inequalities. Part of this was about general resource constraints across the NHS, local government, and other sectors holding back what the system could deliver. Leaders pointed to gaps in funding (‘don’t have the money’) and staff (‘don’t have the workforce’), as well as the capacity of existing staff to prioritize work on health inequalities. As a result, organizations often lacked capacity to plan or deliver new services and prioritized meeting short-term pressures on core services instead (see motivation and purpose):

‘There is no question that we’re under-resourced compared to the amount of stuff that we need to do.’—ICS leader, ICS C.

‘I think the big elephant in the room is a lot of this does need local government delivery. And those budgets, you know, the cuts to local government funding have been eye watering.’—Local authority public health leader, ICS B.

‘People just don’t have the mental or emotional bandwidth sometimes to engage with this stuff, because all of this work in inequalities and wider determinants is on top of everything else we were already doing’—ICS leader, ICS A.

Interviewees also pointed to a lack of dedicated resources to support work on health inequalities. ICSs had been allocated modest additional funding by NHS England for health inequalities interventions—and some organizations had access to other funding for targeted local projects. Leaders welcomed the central funding and gave a mix of examples of how it was being used, including interventions on alcohol and drugs-related issues, grants to voluntary and community sector organizations for place-level projects, and community engagement. But the small sums provided and lack of certainty about whether they would be available to ICSs over the long-term were often identified as barriers to effective investment. More broadly, leaders pointed to how short-term funding pots—often with strings attached to each—could hold back the sustained and systemic changes needed to tackle inequalities:

‘The resources we have—£[X] billion for [ICS population size]—sounds like it’s a lot, but within that £[X] billion, when it arrives in our region, a lot of that is already spoken for. So a lot of that resource goes straight into secondary care contracts, and then the rest goes into our prescribing budgets, commissioning ambulance services, mental health trust. So the actual discretionary spend for you to be innovative and to do things differently is very, very small.’—NHS provider leader, ICS A.

‘I think the key thing for us is the money runs out in March and we only really started to deliver in September, so it’s, kind of like, “Oh my God, we’ve got this deadline in March”. […] And then, by the way, there’s no money after March.’—Community-based organization leader, ICS B.

‘For us, it was very much billed as a one-off fund. And it was peanuts. You know, it translated into, kind of, broadly speaking about three quarters of a million to a million pounds between each area. A huge amount of energy, of, kind of, bureaucratic energy, went into that process because it’s the, kind of, easy thing to do, to spend a bit of money on some new projects. But as we know, nothing is easier than spending a little bit of money on some new projects. System change is so, so, so much harder.’—Local authority public health leader, ICS C.

Weak capacity in ICSs to lead work on health inequalities was often identified as a constraint too. Examples included teams and posts to focus on health inequalities not yet being recruited in ICBs, limited capacity for data analytics, and lack of resources for planning and engagement across sectors. The transition to ICSs and ongoing organizational restructuring in the NHS contributed to these staffing gaps (see external context). A senior manager for health inequalities in ICS B described how:

‘When I went for interview, you know, one of the questions I asked was, “Is there a team?” And I was told, “yes, you know, there will be a team very quickly”, but immediately it became apparent there wasn’t one and it took a lot of hard work just to get one other person recruited and I had to go and identify an external pot of funds. […] I mean, you know, this agenda is massive, so, it feels, since last May, just running, running, running, running […] Given that health inequalities was supposed to be one out of the four main aims—reasons for existing—it didn’t sit right.’—ICS leader, ICS B.

In this context, key individuals were often thought to be crucial for driving cross-sector action on health inequalities. As well as senior organizational leaders (see governance and leadership), interviewees pointed to people able to bridge gaps between sectors—sometimes in jointly funded-posts between the NHS and local government—along with passionate clinicians and others making change happen in local services. In ICS A, public health specialists worked in several NHS trusts and led work on health inequalities, collaborating with local authorities and others. One described how ‘it’s helpful to have interlopers like myself, who basically just work for everyone, […] who have got the permission to roam around the system and join things together and overcome some of those silos.’

Data sharing and analysis

Leaders consistently described how access to high-quality data, including data shared across sectors, was needed to tackle health inequalities—including to understand gaps in services and outcomes, design interventions to address them, track progress over time, and make the case for action with different groups. Leaders in all areas described efforts to use existing data to prioritize action on health inequalities. Organizations were developing various platforms and ‘dashboards’ to help do this, often stitching together a mix of data held locally to create a picture of health inequalities across the ICS. But gaps in data and lack of access to relevant information was frequently identified as a barrier.

One common challenge was sharing data between sectors. As one ICS leader put it: ‘data sharing, you know, all of that information governance stuff, can get in the way quite quickly’. Some leaders gave examples where data had been shared across sectors to target interventions during the covid-19 pandemic (such as shielding vulnerable groups and vaccination programs), or establish particular demonstration programs (such as to deliver more proactive care for high risk groups), but said these data were no longer able to be shared after the programs ended (‘we’ve got to do another whole round of getting these data agreements in place, and that’s just nuts’). This consumed time and resources.

But access to data was not the only issue. Capacity to analyse the data and make it useful to local agencies was another challenge—and NHS restructuring had created further gaps in some ICSs:

‘It’s not just about linking the data and it’s not just about having data, it’s also about having the people who can analyse it, interpret it, and make sure it’s usable, because until we have that then we can’t do the widespread analysis, the front-line analysis […] we can only rely on a central team doing what they have capacity to do. I think that’s a real barrier for us’—ICS leader, ICS C.

‘I think where we’ve struggled is data. That’s been a really big gap. So everyone talks about PHM [population health management] like it’s the great panacea. The CCG has jettisoned or lost almost all of their informatic capacity outside of performance management during the transition. So at the moment we still don’t have as an ICS informatics officer […] and there's no clarity about what the ICS informatics capacity is. […] So the ability for the NHS to actually look at inequalities is quite limited.’—Local authority public health leader, ICS B.

Moving from rhetoric to reality

Resource and capacity gaps contributed to a broader challenge of moving from rhetoric to reality on action to reduce health inequalities. Leaders often talked about a struggle getting beyond describing inequalities to identifying tangible priorities for improvement and making changes in services to achieve them. Short-term pressures tended to dominate instead (see motivation and purpose). Interviewees described a mix of work underway to help organizations across the ICS understand and prioritize action on health inequalities. For instance, in ICS A, local authority leaders had developed ‘toolkits’ for local authorities and NHS providers to help guide interventions to reduce health inequalities, and were now working on similar frameworks for mental health trusts and primary care settings. In ICS C, leaders were considering how to apply quality improvement principles to guide action on health inequalities. In all ICSs, leaders could point to a mix of cross-sector initiatives on health inequalities (Table 6). Nonetheless, leaders frequently worried about an implementation gap:

Table 6.

Examples of cross-sector initiatives on health inequalities

| Focus | Approach |

|---|---|

| Social and economic determinants |

- Identifying households at risk of damp, cold, and other housing-related issues and providing targeted health and social support - Increasing access to skills and employment for people living in more deprived areas, including jobs in health and social care |

| Selected risk factors |

- Coordinated tobacco control programs across the NHS and local government, including population measures and targeted support - Identifying people at risk of developing diabetes in general practice and referral to culturally appropriate prevention support |

| Conditions or population groups |

- Improving maternity care and support for women from Black, Asian, and minority ethnic groups, and more deprived areas - Social prescribing and peer support programs for people with mental health conditions, with a mix of community support |

| Service design and access |

- Identifying people waiting for hospital treatment from more deprived areas and providing proactive health and social support - Service redesign to improve access for more deprived groups, such as changes in opening times, setting, or communication |

| Mechanisms to plan or fund services |

- Flexible funding for local areas within ICSs to design and deliver their own projects to meet health inequalities objectives - Community engagement in areas experiencing worse outcomes to understand barriers to services and priorities for improvement |

‘They’re just, you know, putting out their statements and telling us what great things they’re going to tackle but nothing about how this is going to work or anything’—Primary care leader, ICS A.

‘There’s a lot of talking about inequalities and not as much action.’—Local authority social care leader, ICS B.

‘I think the risk is we keep telling the problem and not doing the interventions. Population health management is just the data bit. It’s just the tool. And I keep saying that to people: […] “What's the intervention?” So I think the risk is we’ll do the data bit and not do the intervention’.—Regional public health leader, ICS A.

‘This whole agenda is how you get beyond rhetoric and saying the right thing and warm words into actions that meaningfully change […] behaviours in health and care organisations […] that ultimately lead to something being different on the ground. And you know, everyone buys in to that warm words and rhetoric. What actual change is driven from this is a whole other question. […] There’s a systemic challenge about moving from rhetoric to reality’—Local authority public health leader, ICS C.

External factors

The broader context in which local organizations operated had a major impact on how they worked together on health inequalities. This included a combination of local factors, such as health needs and geography, and the broader policy context, such as national NHS policy and wider policy and politics on health. The national policy context in the NHS in particular played a dominant role in shaping collaboration experiences across other domains, such as aims, resources, and relationships (Table 5).

At a local level, leaders described a mix of contextual factors influencing the ICS’s work on health inequalities. Examples included the geography and boundaries of the ICS (for example, large and diverse ICSs creating challenges for the coherence of health inequalities plans), the scale of local health needs (for example, stark inequalities in services and outcomes providing motivation for collaboration—see motivation and purpose), and the composition of local health services (for example, with dominant NHS providers having outsized power and influence over how resources are used). The political context in local government also shaped how collaborations worked—for better and worse. In some areas, support of local politicians for action on health inequalities added weight to local efforts (‘we’ve got politicians who are really up for this’). But mixed political leadership of different local authorities within an ICS area—for example, with both Labour and Conservative-led administrations—could make planning and framing issues on health inequalities more difficult.

NHS policy context

At a national level, the biggest factor influencing ICSs was the national policy context in the NHS. Many leaders welcomed the explicit national policy objective for ICSs to reduce health inequalities. This helped give profile to work on health inequalities in ICSs and effectively mandated partnership working to achieve it. For example, a local authority social care leader in ICS C described how the national mandate for ICSs on health inequalities had been a ‘driver’ for the NHS to work differently with local authorities in their area, rather than just thinking ‘well that’s public health and that should be sorted by the council’. But translating this broad objective into tangible priorities was a challenge, and leaders often thought national policy guidance for ICSs on health inequalities was vague (see motivation and purpose). Several interviewees could point to policy documents on ICSs’ role in tackling health and health care inequalities (such as the Core20Plus5 framework [13]), but did not always understand what they meant in practice or find them helpful for their local system. For instance, a leader of ICS A said: ‘well, there’s no clarity at all, is there’. Broader aspects of national NHS policy, such as short-term funding cycles, were identified as barriers to work on health inequalities too.

More fundamentally, leaders described how the behaviour of national NHS bodies undermined the ICS’s work on health inequalities in practice. The overriding priority of national NHS bodies appeared to be on holding ICSs to account for short-term improvements in NHS performance. For example, an ICS leader in ICS A said: ‘I don’t think I've had a conversation on health inequalities or population health with NHS England since we’ve been in existence, but I’d need more than my fingers and toes to count the number of conversations I’ve had on ambulance handover [of patients at acute hospitals].’ Similarly, an ICS leader in ICS C described how ‘even with a big, sort of, program around health inequalities, it’s not the thing that chief execs are asked about when they’re, you know, having those focus calls with NHS England’. This focus on short-term improvements in NHS performance appeared to be increasing, exacerbated by ‘hard’ targets on hospital performance and political pressure to meet them:

‘I cannot explain in seven weeks, eight weeks, how much their focus has changed, it’s unbelievable. It's almost as if, if you came into one job as an ICB chief exec, and you’ve got another job now, which is basically being the chief operating officer for the system, and that is the absolute focus from them, you know. So I’m on, you know, regular phone calls with them about those short-term issues, whether it’s private care access, ambulance turnaround times, 104 week wait, 78 week waits, cancer waiting times. That is the absolute focus.’—ICS leader, ICS B.

The ‘top-down’ and bureaucratic approach of NHS England was identified as a barrier to collaboration too, contributing to cultural differences between the NHS and other sectors (see relationships and cultures) and limiting the agency of local leaders to make decisions. For example, an ICS leader in ICS C described how national NHS bodies tell you ‘on the one hand that the ICS is the one that’s always in control, and then the next time sending you an edict telling you you have to do X. What the fuck? You know, make up your mind’. Reporting upwards to national bodies also consumed time and energy. An NHS provider leader in ICS A, for instance, described NHS England as a ‘hungry beast upstairs that needs to be fed constantly’, and said that ‘the time it takes us to feed the beast and to give updates and all of that is time we haven’t got to spend on driving things forward’.

Organizational restructuring

Organizational restructuring in the NHS to establish ICSs caused major disruption. At the time of our fieldwork, new organizations and organizational partnerships were being established, existing NHS organizations were being restructured, and teams and individuals were being recruited or consulted on their jobs. The scale of upheaval varied, but leaders in all ICSs described the ongoing process of the NHS reorganization and its unintended effects on local partnerships. Examples included lack of clarity about new NHS structures and responsibilities, loss of analytical and other staff, gaps in NHS leadership and management, disrupted local relationships, and time and energy being diverted towards managing the process of structural change. A local authority public health leader in ICS A, for example, described their ‘concern’ about the lack of clarity on NHS roles and responsibilities in their area, looking for answers to questions like: ‘who’s the place-based director? Who’s going to be the director of nursing? What’s the accountability in terms of infection prevention control? Where does quality sit? What happens when there’s a suicide?’ Local authority leaders also described spending substantial extra time supporting the development of new NHS structures and strategies.

Interviewees often commented on the scale of the changes underway and challenging context in which they were being introduced, such as pressures on health and care services and the ongoing effects of covid-19. For some, there was a sense time was being lost while the NHS reorganized itself:

‘I think they’re just rearranging the chairs on the Titanic at the moment, because they haven’t actually got round to thinking about anything. […] They haven’t even organized their people, so how they can start to organize strategy, budgets, resources? I don’t know. […] It’s time being wasted.’ Primary care leader—ICS A.

‘There is instability […] in terms of the extent of the reform. This is massive. The health reform is massive, isn’t it—the establishment of ICSs, the concept of ICBs, the bringing of councils into those for the first time as a, sort of, formal part of the structure, so that’s huge and hasn’t finished yet. […] We cannot keep all of the plates spinning in the way that is expected, so some things are giving.’ Local authority adult social care leader—ICS B.

‘If this had been the council, we would have restructured ready for June. The CCG people, structures, are still being restructured ready for something that happened in June, so it’s like… it’s the NHS is a much slower beast than the local authorities.’ Local authority adult social care leader—ICS C.

Despite widespread support for collaboration to reduce health inequalities (see motivation and purpose), there was also a sense of fatalism about the future of ICSs and perceived inevitability of further NHS restructuring. For some, this contributed to short-termism, instability, and scepticism about ICSs’ potential impact.

‘This stuff takes time, and have we got the political will to see this through? If you kind of think about ICBs, yes they’ve given us all these new statutory responsibilities, but we know that it’s like with NHS structures: the clock’s already ticking. I sort of think we’ve got three years really—if that—to really prove ourselves. And what can you do in three years when it comes to health inequalities?’ ICS leader—ICS A.

‘You can see the opportunities. Whether there’s time to take some before the next reorganization comes, like, only time will tell. I’m not sure’. NHS provider leader—ICS C.

The NHS is constantly changing and never achieving any of these big things it sets out to achieve anyway. […] Part of that could be well, yes, you’re just going through the motions and then you’ll do another big massive restructure in four years’ time, so you can’t measure what’s said anyway.’ Local authority social care leader—ICS C.

Broader political and policy context

The broader political and policy context exacerbated these challenges—and sometimes created them. Several interviewees described a lack of policy coherence in central government on health inequalities as a barrier to collaboration. Some pointed to gaps in national NHS reforms on the role of wider services and sectors in shaping health inequalities—for instance, with existing local government structures focused on reducing health inequalities (such as health and wellbeing boards) not sufficiently ‘respected’ in national NHS reforms to establish ICSs, or national policy documents lacking sufficient detail on the role of local government, housing, or other sectors in reducing health inequalities. Others pointed to cuts in funding for public health and wider public services holding back government policy objectives on health inequalities. The broader context of increasing inequalities and growing economic challenges in England were also identified as constraining factors.

Political leadership was often identified as a barrier to local efforts to reduce health inequalities too—for example, with regular ministerial changes creating policy instability, and a perceived overriding focus among politicians on short-term improvements in NHS performance ahead of the next UK general election undermining longer-term objectives to improve health and reduce health inequalities:

‘In the last year it’s been disgraceful. That’s the only polite word I can think of. You know, so, health inequalities and prevention were seen as priorities, then we’re told “actually, you can’t talk about health inequalities and prevention is off the agenda”. […] So, actually, there’s been this oscillation.’ NHS provider leader—ICS B.

‘I’m paraphrasing here and nobody actually says this openly, but you can see in the national meetings: “well, you’re here to deliver: it’s the next six weeks, getting through winter, then the eighteen months up to the election”. And, effectively, when you’ve already got a government that’s rowing back on potential public health commitments […] and public health funding is going to actually be reduced, you can see that it’s going to be difficult to hold the line at a local level.’ ICS leader—ICS B.

Discussion

We analysed experiences of collaboration between the NHS, social care, public health, and other sectors to reduce health inequalities under NHS reforms in England. We identified a mix of factors shaping local collaboration—from how national policy aims are defined and understood, to the resources and relationships among local organizations to deliver them. We mapped these factors to key domains in the international literature and identified interactions between them. Overall, local leaders described strong commitment to working together to reduce health inequalities in England’s new ICSs, but faced a combination of conceptual, cultural, capacity, and other challenges in doing so. The national policy context played a dominant role in shaping local collaboration experiences—frequently making it harder not easier—and the spectre of further NHS restructuring loomed large.

In many ways, our findings are consistent with international evidence on cross-sector collaboration between health care and non-health care organizations [28]. We identified factors shaping collaboration functioning in England across five domains identified in the international literature, including motivation and purpose, relationships and cultures, resources and capabilities, governance and leadership, and external factors. These domains provided a useful framework to analyse and interpret local experiences in England. And several common factors that appear across multiple studies of local collaboration in diverse country contexts, such as the role of trust between partners, meaningful involvement across sectors, and sufficient resources, were identified in our research too. Our findings also link to broader literature on major system change in England and elsewhere—for instance, in emphasizing the role of differences in meaning, values, power, and resources between organizations and leaders in shaping the formulation and implementation of major system change [52–54]. But evidence on the interaction between factors shaping collaboration functioning and their relative importance in different contexts is limited [28]. Existing studies on cross-sector collaboration also often focus predominantly on local conditions shaping how collaborations work.

Our research highlights the pervasive—frequently perverse—influence of national policy on local collaboration in England. Despite national policymakers mandating partnership working to reduce health inequalities, our data suggest the national policy context often harmed rather than helped local leaders seeking to achieve these objectives. Theory on policy implementation can help illustrate some of these challenges and how they might be addressed. Drawing on models of policy failure [55, 56] and policy streams, [57, 58] Exworthy and Powell describe three ‘streams’ that need to align for successful policy implementation on health inequalities [41–43]. Policies must have clear goals and objectives (the policy stream), feasible mechanisms to achieve these objectives (the process stream), and the financial, human, and other resources to make it happen (the resource stream). These streams also need to align at multiple levels: vertically between central and local agencies (for instance, with policy objectives on health inequalities clearly stated and translated by central government), horizontally between local agencies (for instance, with aims shared by health care, social services, and other agencies responsible for implementing policy changes), and horizontally between national agencies (for instance, with coordination between government health and finance departments to ensure resources are available to meet health inequalities objectives). Complex policy issues like health inequalities, which are affected by decisions across multiple agencies and sectors, make coordination at each level more challenging.

Our study identified misalignment across all three policy streams, both vertically and horizontally. In the policy stream, national policy objectives on health inequalities were vague, contributing to lack of clarity on local priorities and potential conflict between sectors within ICSs. Horizontal coordination at a national level appeared weak, with the behaviour of national policymakers undermining their stated aims on health inequalities—focusing predominantly on short-term political priorities to improve NHS performance instead. In the process stream, ICSs had been established by national NHS bodies as a mechanism to reduce health inequalities, but their governance and accountability was muddy and local leaders were struggling to turn rhetoric on health inequalities into tangible action. The top-down culture of national NHS bodies affected local relationships and constrained leadership agency in ICSs, while the frequency of top-down NHS reform contributed to capability gaps in ICSs, and scepticism and fatalism about their potential impact. In the resource stream, ICSs felt constrained by lack of resources from central government—influenced, in turn, by misalignment between policy and resources centrally. In each stream, national policy context strongly shaped local experiences.

The dominant role of national policy in England is not a surprise—and not, in itself, a problem. The NHS is a national health care system with a strong emphasis on geographic equity of access, [8] and there is a high degree of centralization in UK public policy [59, 60]. Studies of previous health partnerships in England also emphasize the influence of national policy context on how local collaborations work—for better and worse [31, 30, 61, 62]. Indeed, a growing body of evidence suggests that England’s last cross-government strategy to reduce health inequalities, introduced and delivered under Labour governments in the 2000s—involving a mix of investment in public services, new social programs, such as SureStart and the national minimum wage, and various area-based initiatives spanning the NHS and social services—had a positive impact, contributing to reductions in health inequalities over time [63, 64]. In other words, central government matters, and central government can help.

Fast forward to 2024, however, and the problem for ICSs is that national policymakers in England do not appear to have been using their dominant role to enable effective policy implementation on health inequalities. This fits with broader evidence on the Conservative government’s record on health policy in the 2010s and early 2020s. In contrast to the 2000s, there has been no national strategy to reduce health inequalities in England, and investment in public services that shape health and its distribution has been weak [24, 65, 66]. Cuts in spending on local government and public health services since 2010 have hit poorer areas hardest, contributing to growing inequalities [21–23]. And funding for key cross-sector policy interventions that evidence shows can improve health and reduce health inequalities, such as SureStart programs for young children, have fallen substantially [67, 68]. In the NHS, constrained resources and top-down pressure to reduce hospital admissions have held back a series of policy initiatives to better integrate health and social care services locally [31]. Closer alignment between policy, process, and resources on health inequalities will likely be required to enable ICSs to make progress in future. The election of a new UK government in July 2024 provides an opportunity to make this happen—for instance, by developing a new cross-government strategy to reduce health inequalities in England and boosting funding for public health and other local services. The approach of national NHS bodies will also need to change to ensure that short-term targets to improve NHS performance do not crowd out the broader action needed to reduce health inequalities through ICSs. This may require stronger measures and accountability for meeting health inequalities objectives [69].

While our research focuses on policy in England, similar issues occur internationally. For instance, stronger coordination between fragmented national agencies and greater policy alignment at federal, state, and local levels is needed to support effective action to reduce health inequalities in the US [70, 71].

Our research also illustrates the disruption caused by NHS restructuring. The NHS in England is frequently reorganized—and local NHS planning bodies have been in almost constant organizational flux since the 1990s [72]. Evidence suggests these top-down reorganizations deliver little measurable benefit [73–77], while organizational structuring can cause harm [76, 78, 79]. Examples of disruption identified in our research included lack of clarity about roles and responsibilities, loss of analytical and other staff, gaps in NHS leadership and management, disrupted local relationships, and time and energy being diverted from other priorities. In the short-term, at least, the introduction of ICSs had, in some cases, paradoxically posed challenges to the kind of partnership working the reforms were aiming to promote. The threat of further reorganization appeared ingrained in local leaders’ psyche. These practical and psychological risks of restructuring are not unique to the NHS, given major health system reforms in high-income countries frequently involve organizational and governance changes [80].

Limitations

Our study has several limitations. First, we focused on collaboration experiences in three ICSs in England (out of 42), so our findings reflect in-depth experiences in selected ICSs rather than overall experiences nationally. However, our structured sampling approach meant we were able to target ICSs in areas with strong relevance to national policy on reducing health inequalities. We identified three ICSs with varied characteristics all experiencing high levels of socioeconomic deprivation. National policymakers in England are targeting efforts to reduce health inequalities at populations in more socioeconomically deprived areas [13]. Leaders in these ICSs are likely to be particularly aware of their role in reducing health inequalities, and their experiences relevant to other ICSs in similar areas.

Second, our interviews focused on senior organizational leaders in ICSs. This meant we were able to understand high-level perspectives from the most senior leaders responsible for overseeing and directing work on health inequalities in ICSs—as well as the key individuals routinely engaging with national policymakers. It also meant we could gain perspectives from individuals able to describe the overall experiences of their organization and how it works with others. Our sample included a diverse mix of leaders from NHS, social care, public health, and community-based organizations. But our research does not focus on perspectives of people providing services or patients and populations experiencing inequalities. Our sample also excludes national leaders responsible for developing policy on health inequalities and their experiences working with local leaders in ICSs. We use wider evidence on national policy on health inequalities to help interpret and triangulate our findings.

Third, our study data were collected between August and December 2022—early in the development of ICSs, which were formally established in July 2022. This allowed us to understand local perspectives as leaders were collaborating to develop and implement plans on health inequalities—as well as to understand the impact of organizational restructuring to establish ICSs. ICSs had existed informally for several years prior to 2022, and a series of relatively recent policy initiatives had focused on area-based partnerships to reduce health inequalities, [24] so organizations in ICSs were not starting from scratch. But the timing of our fieldwork means our data represent early experiences of collaboration in ICSs after the 2022 reforms, when ICSs were given formal powers. These experiences will evolve as ICSs develop—for instance, as the articulation and understanding of national policy objectives evolves. Further research is needed to track experiences over time.

Conclusion