Abstract

CD8 T cells are the principal antiviral effectors controlling cytomegalovirus (CMV) infection. For human CMV, the virion tegument protein ppUL83 (pp65) has been identified as a source of immunodominant peptides and is regarded as a candidate for cytoimmunotherapy and vaccination. Two sequence homologs of ppUL83 are known for murine CMV, namely the virion protein ppM83 (pp105) expressed late in the viral replication cycle and the nonstructural protein pM84 (p65) expressed in the early phase. Here we show that ppM83, unlike ppUL83, is not delivered into the antigen presentation pathway after virus penetration before or in absence of viral gene expression, while other virion proteins of murine CMV are processed along this route. In cytokine secretion-based assays, ppM83 and pM84 appeared to barely contribute to the acute immune response and to immunological memory. Specifically, the frequencies of M83 and M84 peptide-specific CD8 T cells were low and undetectable, respectively. Nonetheless, in a murine model of cytoimmunotherapy of lethal CMV disease, M83 and M84 peptide-specific cytolytic T-cell lines proved to be highly efficient in resolving productive infection in multiple organs of cell transfer recipients. These findings demonstrate that proteins which fail to prime a quantitatively dominant immune response can nevertheless represent relevant antigens in the effector phase. We conclude that quantitative and qualitative immunodominance are not necessarily correlated. As a consequence of these findings, there is no longer a rationale for considering T-cell abundance as the key criterion for choosing specificities to be included in immunotherapy and immunoprophylaxis of CMV disease and of viral infections in general.

Resolution of human cytomegalovirus (hCMV) infection after bone marrow transplantation (BMT) correlates with the reconstitution of CD8 T cells (54). Clinical trials of cytoimmunotherapy in BMT patients gave promising results in that preemptively transferred hCMV-specific CD8 T-cell clones colonized and persisted for a long time in the recipients and, to the best of our knowledge, did not exert adverse immunopathological effects (56). Since hCMV infection and disease were rarely observed in the recipients, it was justified to propose an antiviral, protective effect of the transferred cells (56, 64). Although the hCMV genome has coding capacity for as many as ca. 200 proteins, only few of those are thought to be relevantly involved in the antiviral control by CD8 T cells (for a recent review, see reference 44). The list so far includes the virion tegument proteins ppUL32 (pp150 or basic phosphoprotein) and ppUL83 (pp65 or lower matrix protein), the virion envelope glycoprotein gpUL55 (gB), and the nonvirion regulatory immediate-early (IE) protein ppUL123 (IE1 or pp68-72). There are no evident common features that could explain the immunodominance of this limited set of proteins, but one may speculate that viral immune evasion mechanisms interfering with the major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class I pathway of antigen processing and presentation (for reviews, see references 19 and 66) are involved in the selection of successful and thus antigenic peptides. To our knowledge, except for ppUL32, a number of antigenic peptides and their presenting MHC class I molecules have been defined by now (reviewed in reference 44). The immunological role of IE1 of hCMV, originally noticed by L. K. Borysiewicz et al. (6), was underestimated for a long time but was brought back to attention recently (reviewed in reference 44). Nonetheless, there is a consensus that ppUL83 is a major antigen of hCMV for recognition by CD8 T cells (35). Several previous reports have documented high frequencies of pp65-specific cytolytic T lymphocytes (CTL) in hCMV-positive individuals (for examples, see references 5, 14, and 67), with the most recent work demonstrating binding by pp65-peptide-folded HLA-A*0201 and HLA-B*0702 tetramers of up to ca. 5% of all CD8 T cells present in the peripheral blood of healthy seropositive donors (14).

Notably, despite its abundant synthesis in infected cells, pp65 is dispensable for virus replication in cell culture (58). As a tegument protein, it gets immediate access to the cytosol in the course of uncoating and enters the MHC class I pathway of antigen processing and presentation. As a consequence, pp65-derived antigenic peptides can be generated and presented before and even in the absence of viral gene expression with an efficacy that depends on the dose of penetrating virions (35, 55). The efficacy of this “exogenous loading” of the MHC class I pathway is further enhanced by a special morphogenetic feature of hCMV, namely the formation of noninfectious subviral particles, called dense bodies (DBs) (8, 57). DBs lack the viral genome and capsid and can be viewed as enveloped packages of pp65, since pp65 accounts for most of their total protein mass (26). Like virions, DBs penetrate efficiently by fusion (57, 62) and deliver their protein content into the cytosol. Recent work by Pepperl et al. has demonstrated the importance of the DB envelope for efficient delivery of pp65 and presentation of pp65-derived antigenic peptide in a vaccination model using HLA-A2 transgenic mice (39). Regarding the contribution of DBs to the immune response in natural infection, it must be noted that DB formation is abundant in cells infected with cell culture-adapted strains of hCMV but is much less so with clinical isolates (29). Yet, as shown by Grefte et al. (16), DBs are found in the cytoplasm of cytomegalic, productively infected epithelial cells circulating in the peripheral blood of patients.

The infection of mice with murine cytomegalovirus (mCMV) has proven a reliable model for many, albeit certainly not all, aspects of CMV immunogenicity and pathogenesis. Specifically, the success of experimental adoptive cytoimmunotherapy of mCMV disease with CD8 T cells (47, 51, 53) has encouraged clinical trials (56). It was demonstrated previously in the murine model that preemptive CD8 T-cell immunotherapy not only prevents lethal disease by resolving acute mCMV infection but also limits the load of latent viral genome and the risk of recurrent infection (59). It was thus an obvious and long overdue issue to investigate the role of virion proteins in the immune response to mCMV and to verify the protective function of virion protein-specific CD8 T cells in cytoimmunotherapy.

It is the merit of D. H. Spector's group to have thoroughly characterized mCMV homologs of hCMV ppUL83 (9, 36, 37). It is important to understand that mCMV genes M82, M83, and M84 as well as their positional homologs in hCMV, namely UL82, UL83, and UL84, have most likely descended from a common ancestor and are therefore all related to some extent (9). The positional homolog of UL83, mCMV gene M83, encodes an 807-amino-acid (aa) phosphoprotein, ppM83 (pp105), which shows significant amino acid homology to ppUL83, although the homology is even closer to ppUL82. Notably, on the basis of shared amino acids, pM84, a 587-aa protein with an apparent molecular mass of 65 kDa (p65), is the closest homolog of ppUL83. However, unlike ppUL83 and ppM83, pM84 was not detected in the virion and is expressed in the early (E) phase of the viral transcriptional program, whereas the virion proteins ppUL83 and ppM83 are both synthesized most abundantly in the late (L) phase (9, 36). In conclusion, ppM83 is an amino acid homolog of ppUL83 and is analogous to ppUL83 by virtue of its virion association, its phosphorylation, and its expression kinetics. A major difference between hCMV and mCMV concerns the morphogenesis of subviral particles: unlike hCMV, mCMV does not generate a significant amount of DBs (65). As a consequence, the quantity of ppM83 does not compare to that of ppUL83, and this difference may play a role for the efficacy with which the immune response is primed in the infected host.

Like ppUL83 of hCMV (58), its mCMV homologs ppM83 and pM84 are both dispensable for virus growth in cell culture. Yet, the respective deletion mutants ΔM83 and ΔM84 of mCMV (strain K181) showed attenuated growth in vivo in various target organs (36). Upon genetic immunization of BALB/c (H-2d haplotype) mice with an M84 expression plasmid followed by challenge infection, pM84 was identified as an immunogenic and actually protection-generating protein (37). Based on this knowledge, our group was recently successful in identifying an antigenic peptide derived from pM84, namely the nonapeptide 297AYAGLFTPL305 that is presented by the MHC class I molecule Kd (23). In contrast, plasmids specifying the mCMV homologs of hCMV virion proteins UL32-pp150 (corresponding to mCMV M32), UL48-pp212 (M48), UL56-(g)p130 (M56), ppUL69 (M69), UL82-pp71 (M82), UL85-mCP (M85), UL86-MCP (M86), and UL99-pp28 (M99) did not confer protection (37). Surprisingly, ppM83 also belonged to the list of nonprotective proteins, and, moreover, this conclusion was confirmed by a study in which mice were immunized with a ppM83-expressing recombinant vaccinia virus, M83-vacc (37). These data thus suggested that there exists a very notable difference between hCMV ppUL83 and mCMV ppM83.

We have here revisited the immunological properties of ppM83 by using mCMV strain Smith. An antigenic peptide presented by the MHC class I molecule Ld has been identified in Smith ppM83, and frequencies of ppM83 peptide-specific CD8 T cells were determined in acute and latent infections. Notably, M83 and M84 peptide-specific CTL lines (CTLL), referred to as M83-CTLL and M84-CTLL, were both found to be capable of resolving acute mCMV infection in various organs of adoptive cell transfer recipients.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

In vivo priming of antiviral effector and memory CD8 T cells.

Animal experiments were approved by the Ethics Commission, permission no. 177-07/991-35, according to German federal law. An immune response to mCMV was elicited by subcutaneous (intraplantar) infection of female, 8- to 10-week-old BALB/c (haplotype H-2d) mice at the left hind footpad with 105 or 106 PFU of cell culture-propagated and then purified mCMV, strain Smith (ATCC VR-194/1981), in 25 μl of physiological saline. As shown previously, the inoculum virus has a genome-to-infectivity ratio of 500 genomes per PFU and is composed of monocapsid and multicapsid virions present in a ratio of ca. 3:2, with multicapsid virions containing 3.4 capsids on average (33). Subviral and incomplete particles are not prominent in mCMV morphogenesis in mouse embryofetal fibroblasts (MEF) (65). In a control group, mice were likewise inoculated with UV light (254 nm)-inactivated mCMV (for details of the inactivation and for efficacy control, see reference 50) equivalent to a dose of 106 PFU, referred to as PFUUV.

Acutely sensitized CD8 T cells were derived from the draining popliteal lymph nodes (PLNs) on day 8 after infection of immunocompetent mice. Memory CD8 T cells were isolated from the spleens after two protocols of infection: protocol A, consisting of intraplantar infection of adult, immunocompetent mice, which is associated with only low local and systemic infection (45), and protocol B, consisting of intraplantar infection of BMT recipients performed after hemato- and immunoablative conditioning by total-body gamma irradiation with a single dose of 6.5 Gy. BMT was syngeneic with BALB/c mice used as bone marrow cell donors and recipients. Reconstitution of recipients was achieved by intravenous infusion of 5 × 106 donor-derived bone marrow cells (21, 40, 59). Infection of BMT recipients is characterized by extensive virus dissemination and highly productive and prolonged infection of various organs, including the spleen (33, 59). In both instances, spleen cells were isolated by standard methods after clearance of the acute, productive infection of the spleen, usually at 3 months postinfection or beyond (33).

CD8 T cells were purified from the leukocyte preparations of lymph nodes (pool of 6 to 12) or spleens (pool of at least three) by positive immunomagnetic cell sorting (MidiMACS separation unit and kit; Miltenyi Biotec Systems, Bergisch-Gladbach, Germany) and controlled for purity by cytofluorometric analysis as described and documented previously (1, 20, 40). In the reported experiments, the purity of the CD8 T-cell preparations was >98%.

Detection of intracellular IFN-γ by three-color cytofluorometric analysis.

Cytofluorometric analyses were performed with a FACSort cytofluorometer (Becton Dickinson, San Jose, Calif.) by using CellQuest software (Becton Dickinson) for data processing. Cytokine synthesis induction cultures and subsequent cytofluorometric analyses of cell surface markers in combination with the detection of intracellular gamma interferon (IFN-γ) were performed essentially as described previously (40). In brief, spleen cells (depleted of erythrocytes) were seeded in replicate 0.2-ml microcultures at a concentration of 106 cells per well and cultured for 5 h in the presence of brefeldin A. Polyclonal induction of cytokine synthesis was achieved by stimulation with a hamster monoclonal antibody (MAb) directed against murine CD3ɛ (clone 145-2C11, IgG; Dianova, Hamburg, Germany) at a dose of 0.4 μg per culture. Peptide-specific induction of cytokine synthesis was achieved with synthetic peptides in solution at a final concentration of 10−6 M. Cells were washed and processed for cytofluorometric analysis. Fluorescence channel 1 (FL-1) represents the fluorochrome fluorescein (fluorescein isothiocyanate [FITC]), FL-2 represents the fluorochrome R-phycoerythrin (PE), and FL-3 represents the tandem fluorochrome PE-Cy5. Cell surface staining was performed with FITC-conjugated MAb anti-CD62L and PE-Cy5-conjugated MAb anti-CD8a. Cells were then fixed with paraformaldehyde, permeabilized, and labeled with PE-conjugated MAb (rat immunoglobulin G1 [IgG1]) anti-mouse IFN-γ or with PE-conjugated rat IgG1 (isotype control). Gates were set on lymphocytes and on positive FL-3 to restrict the analysis to CD8 T cells.

IFN-γ-based ELISPOT assays.

A cytokine secretion assay was used to determine the number of CD8 T cells capable of producing IFN-γ upon polyclonal or antigen-specific signaling via the α/β T-cell receptor (TCR)-CD3 complex. Cells were seeded in graded numbers in nylon membrane-backed enzyme-linked immunospot (ELISPOT) microwells (three replicate cultures for each test) and stimulated for 16 h with 105 antigen-presenting cells. Cells were thoroughly washed off, membrane-bound IFN-γ was labeled, and brown spots, representing imprints of individual IFN-γ-secreting effector cells, were counted under a zoom stereomicroscope for the cell dilution that resulted in >10 (where appropriate) and <100 spots. Photodocumentation was made with a digital camera. Details of the methods were described previously (20, 22, 60). Technical improvements and important controls are shown in Appendix.

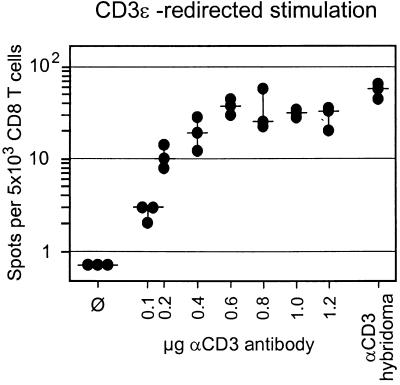

(i) CD3ɛ-redirected ELISPOT assay.

For polyclonal signaling via the CD3ɛ molecule of the TCR-CD3 complex, an assay was performed with immunomagnetically purified CD8 T cells to exclude CD4-positive IFN-γ-producing T-helper type 1 cells. In a modification of the recently described method (20), 145-2C11 hybridoma cells producing anti-CD3ɛ MAb (34) (obtained from and used with the kind permission of J. A. Bluestone, UCSF Diabetes Center, San Francisco, Calif.) were used directly for polyclonal stimulation in place of P815-B7 transfectants armed with Fc receptor-bound MAb derived from the same hybridoma. The equivalence of these two modes of polyclonal stimulation is documented in the Appendix (see Fig. A2).

(ii) Peptide-specific ELISPOT assay.

Another version of the ELISPOT assay was performed as described previously (22) by using P815-B7 transfectants (2) (obtained from and used with the kind permission of L. L. Lanier, UCSF, Department of Microbiology and Immunology, San Francisco, Calif.) for stimulation of whole spleen cells (for motif screening) or of immunomagnetically purified CD8 T cells. It must be noted that binding of immunomagnetic microbeads to CD8 does not interfere with function, because only a few CD8 molecules are actually involved. The P815-B7 cells were pulsed for 2 h at 37°C with a saturating dose of synthetic peptide, usually with a 10−10 to 10−8 M concentration (for determination of the optimal dose, see Fig. A1). Custom peptide synthesis in a 1-mg scale and at a purity of >75% was performed by JERINI Bio Tools GmbH (Berlin, Germany), and peptides were dissolved as specified previously (22). Published antigenic peptides of mCMV include the IE1 (pp89)-derived nonapeptide 168YPHFMPTNL176 presented by Ld (52) as well as the M84 (p65)-derived nonapeptide 297AYAGLFTPL305 presented by Kd (23).

(iii) ELISPOT assay for a naturally presented peptide(s).

For stimulation of T cells, another version of the ELISPOT assay used P815-B7 cells that were mock infected with UV-inactivated virus for exogenous loading of the MHC class I pathway of antigen processing and presentation. UV inactivation does not destroy the fusion activity of virions (57). Mock infection was performed with virus doses of 0.5, 5, 20, and 40 PFUUV per cell under conditions of centrifugal enhancement of virus penetration, with the highest dose corresponding to the amount of virion protein that is associated with 20,000 viral genomes (33).

Generation of peptide-specific CTLL and cytolysis assays.

CTLL specific for antigenic peptides of mCMV were generated essentially as described in a previous report (22), but with some modification. In brief, 1.5 × 107 spleen cells derived at 3 months postinfection from protocol A memory mice were seeded in 2-ml cultures (24-well flat-bottom culture plates) in 1.5 ml of clone medium (46) with no recombinant human interleukin-2 (rhIL-2) added at this stage, but supplemented with synthetic peptides in a concentration specifically optimized for every peptide. As documented for mCMV-m04 (gp34) peptide-specific CTLL (22), the peptide concentration is critical for the generation of a CTLL, as it can be suboptimal as well as supraoptimal. As noted previously, M84-CTLL need to be stimulated with 10−10 M peptide (23), while CTLL with other specificities were found to tolerate a higher dose range. Thus, for instance, IE1-CTLL tolerate 10−7 to 10−11 M, with a broad optimum ranging from 10−8 to 10−10 M (R. Holtappels, unpublished observation), and M83-CTLL can be generated at 10−9 to 10−11 M, with the optimum at 10−10 M. At day 4, 100 U of rhIL-2 was added in 0.5 ml of fresh clone medium. Further rounds of restimulation were performed weekly beginning on day 7 by a 1:1 split of the cultures and readdition of 1 ml of clone medium supplemented with the appropriate dose of peptide, 200 U of rhIL-2, and 5 × 105 gamma irradiated (25 Gy) normal spleen cells as feeder cells. Usually, CTLL reached monospecificity, as assessed by congruence between peptide-specific and CD3ɛ-redirected cytolytic activity (21) after three (e.g., M83-CTLL and IE1-CTLL) or three to five (e.g., M84-CTLL) rounds of restimulation. CTLL were usually maintained for up to 3 months without significant loss of activity. By cytofluorometric analysis, all CTL were classified as CD8 T cells. In the case of in vitro restimulation of memory cells with infectious mCMV for subsequent ELISPOT analysis, 107 spleen cells were seeded in a 2-ml culture (24-well plate) with 5 × 105 PFU of mCMV. At day 4, the medium was supplemented with 100 U of rhIL-2.

Cytolytic activity of CTLL was tested in a standard 4-h 51Cr release assay, performed with graded numbers of CTL and with the constant number of 103 51Cr-labeled target cells per 0.2-ml microwell, resulting in different effector-to-target (E/T) cell ratios. The percentage of specific radioactivity release (i.e., target cell lysis) represents the mean value of triplicate cultures. Target cells for monitoring peptide-specific CTL activity were P815 cells (DBA/2 mouse-derived mastocytoma; H-2d) pulsed for 15 min at ca. 22°C with the indicated molar concentrations of synthetic peptides. Excess peptide was washed out before use of the peptide-loaded target cells in the assay. Total cytolytic activity, elicited by addressing the TCR-CD3 complex directly, was measured by CD3ɛ-redirected lysis of P815 target cells carrying Fc-receptor-bound hamster MAb (clone 145-2C11; Dianova) specific for murine CD3ɛ (21). For Fc receptor loading of the target cells, 4 × 105 P815 cells were incubated with 3 μg of the MAb. Excess antibody was washed out before use of the anti-CD3ɛ-armed target cells in the assay.

Analysis of viral gene expression.

The kinetics of viral gene expression in infected MEF (per time point, three monolayer cultures in a six-well plate, containing 2.5 × 105 cells per culture) was assessed by reverse transcriptase (RT) PCR. Specifically, MEF were infected in the third cell culture passage with 0.2 PFU of mCMV per cell under conditions of centrifugal enhancement of viral penetration and infectivity (33), resulting in a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 4 infectious units (PFU∗) per cell, with 1 PFU* representing 25 viral genomes. Under these conditions, >90% of the cells were infected as assessed by immunofluorescence specific for the intranuclear IE1 protein pp89. When indicated, transcription was blocked irreversibly with actinomycin D added to the culture medium in a concentration of 5 μg per ml, and translation was reversibly blocked with 100 μg of cycloheximide per ml.

(i) Isolation of polyadenylated RNA.

At the indicated time points postinfection, culture medium was removed and the lysis-binding buffer of the μMACS mRNA isolation kit (catalog no. 752-01; Miltenyi Biotec Systems) was added. The detachment of cells was facilitated by using a cell scraper. The material was mixed in a vortex machine for 1 min and disrupted by freezing (−20°C) and thawing, and the lysate was vortexed again for 3 min. Poly(A)+ RNA was purified from that lysate by using MACS column type-μ (Miltenyi) filled with oligo(dT)-coated superparamagnetic microbeads (50-nm diameter). In essence, the method was performed according to the instructions of the supplier, with the modification that a step of digestion of contaminating DNA was included. This was important since genes M83 and M84 do not possess an exon-intron structure that would allow an RNA-specific RT-PCR design. In detail, unbound material was removed from the column by four cycles of washing with the wash buffer contained in the kit, and DNA was digested for 10 min at ca. 22°C with 100 μl of DNase solution containing 5 μl (50 U) of DNase I (fast protein liquid chromatography purified and RNase free, catalog no. 27-0514-01; Amersham Pharmacia Biotech) in assay buffer (40 mM Tris [pH 7.5], 6 mM MgCl2). The reaction was stopped by addition of 2 × 150 μl of lysis-binding buffer supplemented with 10% (vol/vol) EGTA, pH 8.0. After washing with lysis-binding buffer (two times with 200 μl) and wash buffer (four times with 100 μl), poly(A)+ RNA was eluted with 120 μl of elution buffer. The first drop was discarded; drops 2 to 4 (ca. 75 μl) were collected and adjusted with H2O to a volume of 100 μl for storage at −70°C. Throughout, 10 μl samples of a 1/10 dilution of the stock (ca. 10 ng, representing the yield of ca. 104 infected MEF) were subjected to qualitative RT-PCR.

(ii) Primers and probes for RT-PCR.

Throughout, oligo(dT) priming was used for the RT reaction mixtures. RT-PCRs specific for transcripts of mCMV gene ie1 and the cellular gene hprt (hypoxanthine phosphoribosyltransferase) were described previously (22) and gave fragments of 280 bp and 163 bp, respectively. The ie1-specific probe was directed against the exon 3-exon 4 junction to ensure detection of the correctly spliced mRNA. Positions of primers and probes for M83 and M84 gene expression refer to the genomic sequence of the Smith strain of mCMV (43) (GenBank accession no. MCU68299 [complete genome]). Since genes M83 and M84 show significant homology (9), primers and probes had to be selected from nonhomologous regions to exclude cross-amplification and cross-hybridization. Detection of M83 cDNA used forward primer 5′-117,906-117,929-3′ (5′-CGTTTCGACAGTCCTGTTTTCGTG-3′) and reverse primer 5′-118,281-118,258-3′ (5′-GTGACAATCCATTCTACCGCAACC-3′). The 376-bp M83 amplificate was detected by probe 5′-118,029-118,052-3′ (5′-TGCAGAAAGAGGGATATCGCCTCG-3′). Detection of M84 cDNA used forward primer 5′-120,801-120,822-3′ (5′-GCGAGACGAAGTACATGTCTCC-3′) and reverse primer 5′-121,204-121,183-3′ (5′-GTACGTGTCGTTCGCGACCAAG-3′). The 404-bp M84 amplificate was detected by probe 5′-120,961-120,982-3′ (5′-CCTCGAGAAGTAGCTGATTGAC-3′).

(iii) RT-PCR.

Reactions were carried out by using an automated thermal cycler (GeneAmp PCR System 9700; Perkin-Elmer Applied Biosystems, Norwalk, Conn.). The RT reaction was performed as recently described in greater detail (22). For the subsequent amplification of M83 and M84 cDNA sequences by PCR, the time-temperature profile for cycles 2 through 29 was as follows: denaturation for 30 s at 96°C, annealing for 1 min, and elongation for 1 min at 72°C. The annealing temperatures were 64°C and 60°C for M83 and M84, respectively. In the first cycle, denaturation was performed for 3 min at 95°C. In the last cycle (cycle 30), the elongation time was extended to 5 min. Amplification products (20 μl thereof) were visualized by standard procedures of 2% (wt/vol) agarose gel electrophoresis. Southern blotting, hybridization with the respective γ-32P-end-labeled oligonucleotide probe, and autoradiography.

Preemptive cytoimmunotherapy of acute CMV infection.

Adoptive cell transfer into infected recipient mice was used to determine the in vivo antiviral efficacy of peptide-specific CD8 T cells, specifically of cells from a CTLL. Recipients were 8-week-old, female BALB/c mice that were immunosuppressed by gamma-irradiation with a dose of 6.5 Gy. After intraplantar infection with 105 PFU of purified mCMV, recipients all die of multiple-organ CMV disease between day 10 and day 18 after infection, unless they receive protective T cells (53, 59). Graded numbers of CTL were transferred intravenously (into the tail vein) 2 h before infection, and antiviral function in recipients' tissues was assessed on day 12 postinfection.

(i) Quantitation of infectious virus in organs.

Virus titers in organ homogenates, here specifically of spleen, lung, and liver, were measured by a plaque assay performed on subconfluent second-passage MEF monolayers under conditions of centrifugal enhancement of infectivity as described in greater detail previously (53). The virus titers represent the amounts of infectious virus per organ and are expressed as PFU*, with the asterisk indicating the ca. 20-fold enhancement of infectivity that is achieved by the centrifugally enforced virus penetration (33).

(ii) IHC detection of infected cells in situ.

Direct visualization of organ infection was achieved by immunohistochemical (IHC) detection of infected cells in 2-μm tissue sections, here specifically in whole-organ sections of the suprarenal (adrenal) glands, by staining of the intranuclear IE1 protein pp89 of mCMV, precisely as described in a previous report (17). In essence, infected cells were stained black by the nickel-enhanced avidin-biotin-peroxidase method with MAb CROMA 101 (S. Jonjic, University of Rijeka, Department of Histology and Embryology, Rijeka, Croatia) serving for the specific detection of IE1. A low-intensity counterstaining was performed with hematoxylin for just 5 s in order to give optimal contrast between infected and uninfected nuclei and still allow sufficient staining to reveal the typical zonation of the suprarenal gland. Microphotographs were taken with a Zeiss research microscope (Axiophot; Carl Zeiss Jena GmbH, Jena, Germany) at low magnification using a 2.5× objective lens (plan-Neofluar; Zeiss). Diapositives were scanned for computed documentation.

RESULTS

Genes M83 and M84 of mCMV strain Smith are both transcribed in the E phase.

Previous work from the group of D. H. Spector has characterized M84 of mCMV strain K181 as an E gene with mRNA detectable in NIH 3T3 cells by Northern blotting at 8 h postinfection. It encodes a nonphosphorylated protein of 587 aa with an apparent molecular mass of 65 KDa, p65 (36). This protein was detectable by Western blotting at 8 h postinfection in NIH 3T3 cells but was undetectable in virion preparations. By contrast, M83 was found to encode a phosphorylated virion protein, presumably a tegument protein, of 807 aa with an apparent molecular mass of 105 kDa, pp105 (9, 36). Its mRNA became detectable in NIH 3T3 cells at 24 to 48 h postinfection, while immunoreactive protein species were seen only at 48 h, suggesting that M83 is expressed with L kinetics (9).

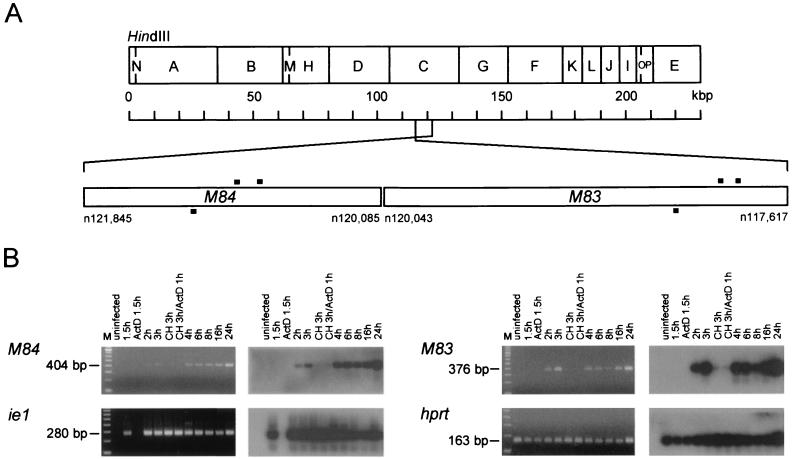

Since gene expression may differ in MEF infected with mCMV strain Smith (ATCC VR-194), we reinvestigated the expression kinetics of genes M83 and M84 in infected MEF, and we chose RT-PCR with oligo(dT) priming of the reverse transcription as the most sensitive method for detecting polyadenylated transcripts. Controls included detection of spliced ie1 transcripts (exon 3-exon 4) and transcripts of the cellular gene hprt (Fig. 1). As predicted, a steady-state level of hprt mRNA was detected throughout the kinetics in infected cells and was present in uninfected cells as well as in cells infected in the presence of actinomycin D. In accordance with the definition of IE genes, ie1 transcription was found to be blocked by actinomycin D but not by cycloheximide. M84 transcripts were generated only in the absence of metabolic inhibitors and became visible after just 2 h. Thus, in line with earlier conclusions for mCMV-K181, M84 is an E gene. Unexpectedly, the expression of M83 showed a very similar kinetics and drug sensitivity, classifying it as an E gene as well. In accordance with the definition of E genes, transcription of M83 and M84 was not blocked by phosphonoacetic acid (not shown). As noted above (see the introduction), genes M83 and M84 are homologous to each other as well as to hCMV ppUL83. This fact entailed a theoretical risk of cross-amplification in RT-PCRs. We have therefore selected primers and probes from nonhomologous regions. Accordingly, when hybridized reciprocally with the M83 and M84 probes, the M83 and M84 RT-PCR products were not detected with the respective heterologous probe (not shown).

FIG. 1.

Expression of genes M83 and M84. (A) HindIII map of the mCMV (strain Smith) genome with the relevant region expanded. Nucleotide (n) positions refer to the sequence published by Rawlinson et al. (43). Black bars, positions of PCR primers and probes. (B) Kinetics of viral gene expression in MEF analyzed by RT-PCR. Poly(A)+ RNA was isolated at the indicated time points after infection that was performed in the absence or presence of metabolic inhibitors. CH, cycloheximide; ActD, actinomycin D. (Left panels) Ethidium bromide-stained gels verifying the correct sizes of the amplificates. M, 100-bp size markers. (Right panels) Corresponding Southern blot autoradiographs obtained after hybridization with the specific γ-32P-end-labeled oligonucleotide probes. The expression of mCMV gene ie1 and that of the cellular gene hprt were studied for comparison. Blots did not show any amplificates when the RT step of the RT-PCR was omitted.

Identification of an antigenic peptide in M83 by the reverse immunology approach.

Previous work had shown a recognition by polyclonal CTL of target cells that were exposed to UV-inactivated mCMV virions or were infected with mCMV in the presence of metabolic inhibitors preventing viral gene expression (49, 50). Yet, since then, a virion-derived antigenic peptide(s) remained unidentified for mCMV. As the tegument protein ppUL83 is a major antigenic protein of hCMV, it was tempting to speculate that its mCMV homolog, the virion protein ppM83, actually represents the antigen responsible for the earlier results. Thus, even though an M83 expression plasmid and the recombinant vaccinia virus M83-vacc had both failed to prime for protective immunity against mCMV-K181 in BALB/c mice (37), we performed a search for an antigenic peptide in ppM83 of mCMV Smith, on the basis of the amino acid sequence deduced from the nucleotide sequence published by Rawlinson et al. (43).

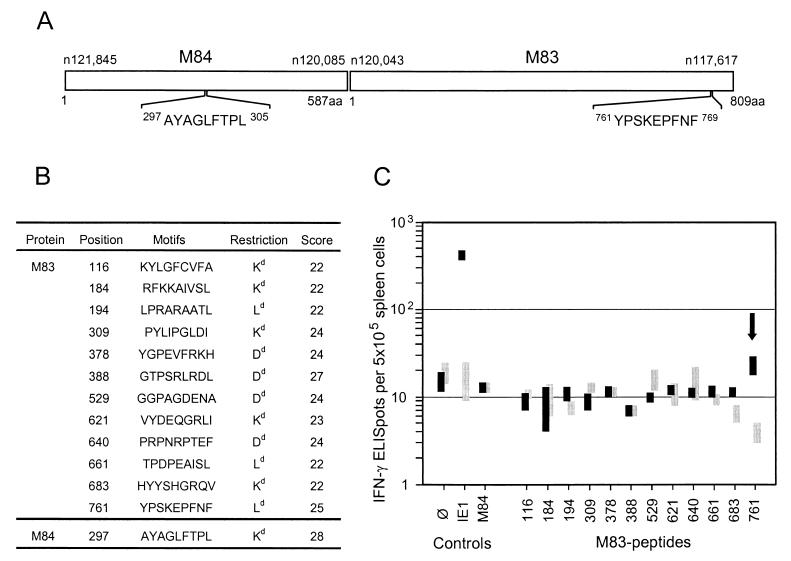

We used the antigenic motif forecast developed by Rammensee and his colleagues (for an overview, see reference 42). In essence, the forecast is based on the identification of conserved anchor residues of peptides extending into hydrophobic pockets of MHC class I molecules. Specifically, the major nonameric motifs are X(Y or F)XXXXXX(I or L or V), XGPXXXXX(L or I or F) and X(P or S)XXXXXX(F or L or M) for the H-2d haplotype MHC class I molecules Kd, Dd, and Ld, respectively. In addition, we limited the search to motifs that scored 22 or higher in a refined forecast (Internet database SYFPEITHI, version 1.0; htpp://www.uni-tuebingen.de/uni/kxi/). By using this approach, the M84-derived antigenic peptide 297AYAGLFTPL305 (Fig. 2A) that is presented by Kd was recently identified (23).

FIG. 2.

Identification of an antigenic peptide in ppM83. (A) M84 and M83 open reading frames drawn to scale. Nucleotide (n) and amino acid (aa) positions refer to the sequence of mCMV strain Smith. (B) List of nonameric antigenic motifs predicted by SYFPEITHI, version 1.0 (http://www.uni-tuebingen.de/uni/kxi/). One predicted Ld motif with the sequence DPEAISLFL (score of 22) is not included, because the corresponding peptide could not be synthesized with the standard technique. (C) Screening of the synthetic nonapeptides listed in panel B by an IFN-γ-based ELISPOT assay. Bars, ranges of triplicate determinations. Responder cells were memory spleen cells derived from mCMV-infected (protocol A) BALB/c mice (solid bars) or naive spleen cells derived from unprimed BALB/c mice (shaded bars). Stimulator cells were P815-B7 cells pulsed with 10−8 M peptide. ∅, P815-B7 cells with no peptide added; IE1, antigenic peptide 168YPHFMPTNL176 of the IE1 protein; M84, antigenic peptide 297AYAGLFTPL305 of the M84 protein. Arrow, data obtained with the M83 peptide 761YPSKEPFNF769.

The MHC class I motifs in the M83 Smith amino acid sequence (listed in Fig. 2B) were tested as synthetic peptides by pulsing P815-B7 cells for a peptide-specific IFN-γ-based ELISPOT assay. Responder cells were unseparated spleen cells derived from infected immunocompetent mice after resolution of acute infection, referred to as protocol A memory mice. Spleen cells isolated from unprimed mice were used as responder cells for controlling priming dependence, and known mCMV peptides IE1-168YPHFMPTNL176 and M84-297AYAGLFTPL305 were included for comparison. Criteria for the definition of an immunogenic peptide were, first, a responder cell frequency above the background defined by the omission of peptide in the assay and, second, a clear difference in the response of primed and unprimed spleen cells. The only M83 peptide that fulfilled both criteria was peptide 761YPSKEPFNF769 (Fig. 2C), representing an Ld motif with a fairly high score (Fig. 2B). In accordance with previous data (23), the IE1 peptide was recognized by a significant proportion of the cells, namely by ca. 0.8% of the CD8 T cells (considering that ca. 10% of the spleen cells are CD8 T cells), while CD8 T cells specific for the CTL-defined M84 peptide were not detectable on the basis of IFN-γ secretion (Fig. 2C).

Cytofluorometric detection of IFN-γ synthesis induced by the M83 peptide.

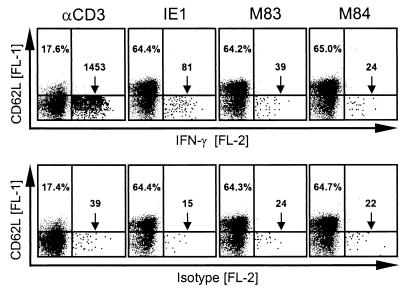

Staining of intracellular IFN-γ after peptide-induced synthesis was used as a second method to confirm the ELISPOT-identified antigenic M83 peptide (Fig. 3). As in the situation illustrated in Fig. 2, peptide-specific cells were detected in a population of protocol A memory spleen cells. Cells were stained for surface CD8, surface CD62L (L-selectin), and intracellular IFN-γ. Cytofluorometric analysis was restricted to CD8 T cells by appropriate electronic gates. Polyclonal stimulation with a MAb directed against the CD3ɛ chain of the TCR-CD3 complex resulted in downregulation of CD62L surface expression in the majority of CD8 T cells, which is consistent with rapid proteolytic cleavage of CD62L upon stimulation (61). However, only a minority of the CD62Llo CD8 T cells were capable of producing IFN-γ. Specifically, of 20,000 CD8 T cells analyzed, only 1,414 (7.1%; isotype control subtracted) expressed IFN-γ. Since the number of CD8 T cells expressing T-killer type 2 cytokines IL-4 or IL-5 was found to be very low (not shown), we infer from this finding that different levels of activation are required for downregulation of CD62L and induction of IFN-γ synthesis in the T-killer type 1 CD8 T cells. This positive control is important for evaluating the frequencies of peptide-specific cells. Thus, the frequencies of IE1 and M83 peptide-specific CD8 T cells were 66 and 15 per 20,000 CD8 T cells, that is, 0.33 and 0.075%, respectively. However, when related to the number of CD8 T cells capable of responding to a TCR-CD3 stimulus with production of IFN-γ, these frequencies have to be corrected to 4.7 and 1.1%, respectively. In accordance with the ELISPOT results (Fig. 2C), the number of M84-specific memory CD8 T cells was below the detection limit.

FIG. 3.

Detection of peptide-specific memory cells by induction of IFN-γ synthesis. Memory spleen cells isolated at 3 months after intraplantar mCMV infection of immunocompetent BALB/c mice (protocol A memory) were stimulated either polyclonally via CD3ɛ or specifically with the antigenic peptides IE1-168YPHFMPTNL176, M83-761YPSKEPFNF769, and M84-297AYAGLFTPL305. Secretion of IFN-γ was blocked by brefeldin A. The proportion and phenotype of CD8 T cells that synthesized IFN-γ was determined by three-color cytofluorometric analysis of the expression of cell surface CD62L (FL-1) and CD8 (FL-3) and of intracellular IFN-γ (FL-2). PE-conjugated rat IgG1 (FL-2) was used for control. An electronic gate was set on positive FL-3 to restrict the analysis to CD8 T cells. Shown are two-dimensional dot plots of FL-1 versus FL-2 fluorescences for 20,000 gated CD8 T cells with all dots displayed. For better documentation, dots in the relevant lower right quadrants are shown enlarged. Percentages in the upper left quadrants show the proportions of resting, CD62Lhi-expressing cells. The frequencies of activated IFN-γ-expressing cells located in the lower right quadrants (surface phenotype, CD8+CD62Llo) are given as numbers of cells per 20,000 CD8 T cells.

Frequencies of mCMV-specific IFN-γ-defined memory CD8 T cells in the spleen.

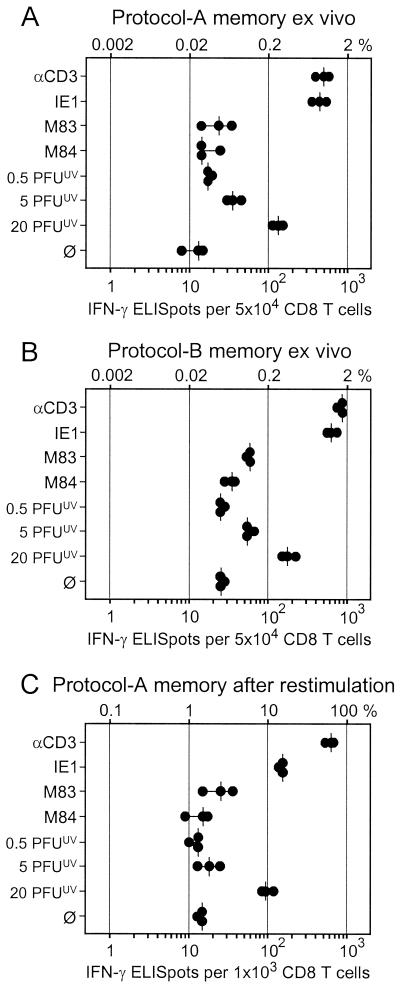

The quantitative contribution of M83 and M84 peptide-specific CD8 T cells to the immune response against mCMV infection was evaluated by measuring the frequencies of memory CD8 T cells present in the spleen after resolution of production infection, that is, during viral latency (33). The analysis was made with immunomagnetically purified, positively sorted CD8 T cells to exclude detection of other IFN-γ-producing cell types such as CD4 T cells and NK cells. The CD3ɛ-redirected ELISPOT assay (20) (see also Appendix) was employed to determine the frequency of CD8 T cells present in a metabolic state capable of responding with IFN-γ secretion after antigen-independent, polyclonal stimulation via the TCR-CD3 complex. The known immunodominant IE1 peptide was included for comparison. Since we had surmised that the virion protein ppM83, like its homolog ppUL83 of hCMV, might be processed along the MHC class I pathway after virion penetration and uncoating, the frequency of CD8 T cells recognizing processed virion antigens in the absence of viral gene expression was determined. To this end, an ELISPOT assay was performed with stimulator cells that were exposed to graded doses of UV-inactivated virions. Among CD8 T cells derived from the spleen at 3 months after intraplantar infection of immunocompetent mice (protocol A memory), ca. 1% (median value) responded to anti-CD3ɛ (Fig. 4A). A great majority of these cells were specific for the Ld-presented IE1 peptide, namely ca. 0.8% of all CD8 T cells or ca. 80% of all responding cells. M83 contributed little, namely 0.05% of all CD8 T cells, and the number for M84 was within the range found for spontaneous secretion of IFN-γ. Notably, CD8 T cells specific for virion-derived antigens were detected in frequencies dependent upon the dose of inactivated virions, with a frequency of ca. 0.3% of all CD8 T cells at the highest dose tested. It should be noted that 20 PFUUV is an enormous dose that corresponds to ca. 6,000 monocapsid plus ca. 1,000 multicapsid virions per cell (33). Altogether, considering the variance in all measurements, IE1-specific and virion antigen-specific CD8 T cells accounted for a major part of the response.

FIG. 4.

Frequencies of memory CD8 T cells determined by IFN-γ-based ELISPOT assays. For mCMV-specific stimulation of responder cells, P815-B7 cells either were pulsed with saturating doses of antigenic peptides (IE1, M83, and M84) or were exposed to the indicated doses of UV-inactivated virions. αCD3, polyclonal stimulation with 145-2C11 hybridoma cells that produce MAb anti-mouse CD3ɛ; ∅, P815-B7 cells with no peptide added. Dots, data from triplicate assay cultures. Vertical bars, median values. (A) Responder cells were CD8 T cells derived from the spleen at 3 months after intraplantar infection of BALB/c mice with 105 PFU of mCMV. (B) Responder cells were CD8 T cells derived from the spleens of BALB/c mice at 6 months after syngeneic BMT and intraplantar infection with 105 PFU of mCMV. (C) Responder cells were CD8 T cells derived from memory spleens (protocol as described for panel A) after one round of in vitro restimulation with mCMV in the presence of rhIL-2.

Intraplantar infection of immunocompetent mice causes only limited virus replication locally and in organs, which is rapidly controlled, except in the salivary glands (45). This situation may favor the priming of IE1-specific CD8 T cells, because IE1 can be expressed in cells that are not productively infected. In contrast, intraplantar infection of immunodeficient BMT recipients is associated with highly productive and prolonged virus replication in many organs before hematopoietic reconstitution generates antiviral CD8 T cells that resolve the acute infection (21, 40, 41, 59). This situation might therefore improve the chance for the priming of CD8 T cells specific for virion-derived antigens. With this rationale in mind, we performed the analysis with CD8 T cells isolated from the spleen of mice at 6 months after BMT and intraplantar infection, referred to as a protocol B memory condition (Fig. 4B). The much more extensive viral replication in these mice had in fact generated somewhat higher frequencies of memory cells, but compared with protocol A memory, the increase was rather moderate (e.g., 1.8 versus 1.0% for anti-CD3ɛ and 1.2 versus 0.8% for IE1). Notably, against our assumption, the specificity pattern of the response was qualitatively unchanged. Specifically, the number of CD8 T cells recognizing virion antigens was barely elevated, and the response to M84 remained insignificant. Yet, with 0.12% as opposed to 0.05% in the absence of stimulation with peptide, the frequency of M83 peptide-specific CD8 T cells was now significant.

Restimulation of memory cells with virus in cell culture is frequently used for clonal expansion and has originally led to the conclusion that ppUL83 is by far dominant over IE1 in the immune response to hCMV, a conclusion that was relativized recently (reviewed in reference 44). While this strategy increases the absolute numbers of antigen-specific cells and may thus help to confirm the existence of low-frequency specificities, it entails some risk of in vitro selection that can change the proportions between different specificities and thus may mislead with regard to the in vivo immunodominance of antigens. The selecting force of a single round of restimulation with mCMV was tested for protocol A memory spleen cells (Fig. 4C). In essence, expansion for 1 week in presence of mCMV and rhIL-2 markedly increased all frequencies. Specifically, ca. 1.5 and ca. 70% of all CD8 T cells in the cultures secreted IFN-γ spontaneously and after maximal stimulation via CD3ɛ, respectively. Notably, the original ranking of the antigen-specific responses (compare Fig. 4A and C) was not yet qualitatively disturbed, but in quantitative terms the restimulation apparently selected against IE1-specific CD8 T cells (ca. 14% compared with ca. 10% specific for virion antigens). Thus, the in vivo significance of IE1 in the immune response to mCMV would have been underestimated on the basis of this assay, as was the case of IE1 of hCMV. Restimulation with infectious virus, however, did not help to expand M83 and M84 peptide-specific CD8 T cells to a level more significantly above the baseline defined by the number of cells that secreted IFN-γ spontaneously.

Specificity of CD8 T cells present in draining lymph nodes during acute infection.

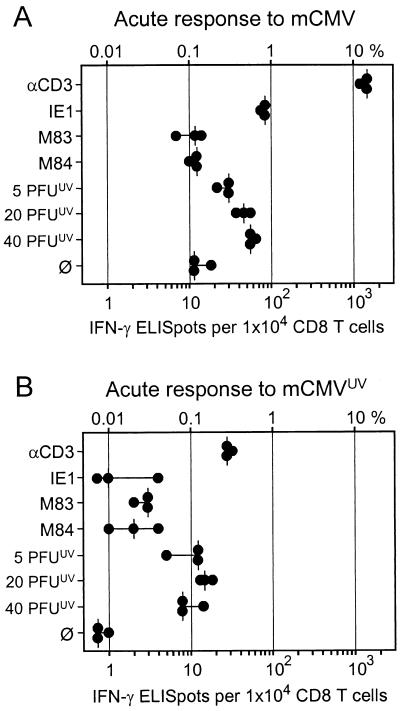

The data have thus far shown that M83 and in particular M84 peptide-specific CD8 T cells are not prominent in memory populations in the spleen. There is evidence from other virus infections that the specificity repertoire involved in memory T-cell responses can differ from the repertoire that constitutes the primary response to acute infection (4, 63). Specifically, an antigenic peptide that is immunodominant in the acute response does not necessarily participate in the generation of memory (3). It was therefore worthwhile testing whether the M83 and M84 peptides sensitize CD8 T cells during acute infection. To this end, the acute immune response was analyzed in the lymph node that drains the site of intraplantar infection, which is the PLN. Previous work on the acute immune response to intraplantar mCMV infection has shown a peak activity in the ipsilateral PLN on day 8, as defined by the number of lymph node lymphocytes and by the number of sensitized, IL-2-responsive CTL precursors (48). Furthermore, the dose-response relation had revealed an only fivefold increase in the CTL precursor frequency after the virus dose was increased from 102 to 106 PFU (48). We have therefore infected with the highest dose that is reasonable, i.e., with 106 PFU, and the ELISPOT assay was performed on day 8 with purified CD8 T cells (Fig. 5A). The frequencies of CD3ɛ-responsive cells and of IE1 peptide-specific cells were found to be ca. 12 and 0.9%, respectively. As one expects for highly sensitized cell populations, some cells secreted IFN-γ spontaneously (ca. 0.11% as opposed to ca. 0.03% for memory cells [Fig. 4A]). In accordance with previous work on sensitized CTL precursors present in the PLN (49, 50), virion-derived antigens were recognized by a significant number of cells that increased to up to 0.6% with increasing doses of inactivated virions used for exogenous loading of the MHC class I pathway in the presenting cells. However, M83 and M84 peptide-specific cells were not significantly involved in the acute immune response.

FIG. 5.

Frequencies of CD8 T cells present in the draining popliteal lymph node during the primary immune response. Stimulation conditions for the IFN-γ-based ELISPOT assays were as described for Fig. 4. (A) Primary immune response in the ipsilateral PLN at day 8 after intraplantar infection with 106 PFU of mCMV. (B) Primary immune response in the ipsilateral PLN at day 8 after intraplantar inoculation with 106 PFUUV of inactivated mCMV virions.

Exogenous loading of the MHC class I pathway could also prime for a virion antigen-specific response in vivo (39). To investigate the contributions of incoming virion antigens and of viral replication to the acute immune response in the PLN, we inoculated mice with 106 PFUUV. The inactivated virions also caused a significant swelling of the PLN associated with a cell number of 7.1 million cells, as opposed to 11.7 million and 0.9 million cells in PLNs of infected (refers to 106 PFU) and of uninoculated mice, respectively (not shown). The proportion of CD8 T cells in the PLN was also not impressively different after priming with infectious and with inactivated virus, namely 19.1 and 16.5%, respectively, and the corresponding CD8:CD4 ratios were 0.53 and 0.39 (cytofluorometric data not shown). Yet, it has to be considered that most of the increase in cell number after priming results from lymphocyte trapping in the draining PLN and not from antigen-driven cell proliferation. In fact, as revealed by ELISPOT assays (Fig. 5B), the inactivated virus hardly induced CD3ɛ-responsive CD8 T cells (0.3% as opposed to 12% induced by infectious virus [Fig. 5A]) and failed to induce CD8 T cells specific for peptides IE1, M83, and M84. Spontaneous IFN-γ secretion was below the detection limit. Notably, inactivated virions primed some cells that responded to virion antigens, but their number was less than after infection (ca. 0.15 versus 0.6%). This finding implies that the virion antigen-specific response is primed mainly by virus replication and only to a lesser extent by virion proteins contained in the inoculum.

In conclusion, efficient priming depends on replicative virus and generates significant numbers of effector cells specific for the IE1 peptide as well as of effector cells that recognize virion-derived antigens. The contribution of M83 and M84 peptide-specific CD8 T cells to the acute immune response is minimal, if there is any.

Generation and comparative characterization of M83 and M84 peptide-specific CTLL.

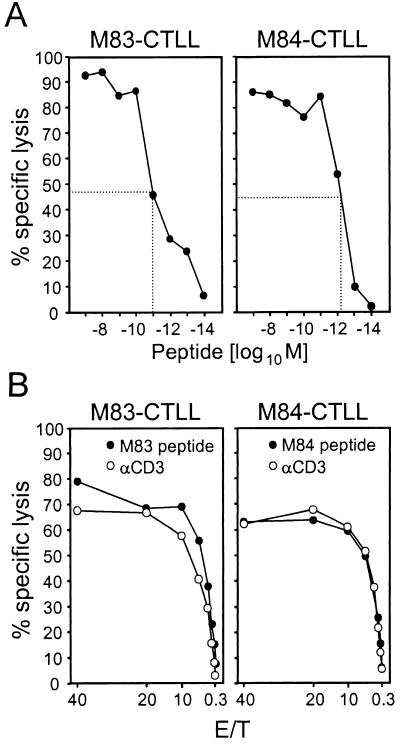

Even though the frequency of M84 peptide-specific CD8 T cells defined by IFN-γ ELISPOT did not exceed the detection limit in acute and memory immune responses to mCMV infection (see above), an M84 peptide-specific CTLL has previously been successfully raised (23). In that work, the peptide was identified by screening of Rammensee's motifs on the basis of CTL activity, whereas screening on the basis of IFN-γ secretion had failed to detect the peptide. Since M83 peptide-specific CD8 T cells were detectable in memory spleen cell populations by the ELISPOT assay (Fig. 4), we saw a good chance for raising a CTLL. In fact, a CTLL could be generated from protocol A memory spleen cells by three cycles of restimulation with the M83 peptide. M83-CTLL and M84-CTLL were both highly cytolytic, and half-maximal cytolysis of peptide-loaded P815 target cells was achieved for 10−11 and 10−12 M concentrations of peptide, respectively (Fig. 6A). Thus, peptides M83 and M84 bind with very high affinity to their presenting MHC class I molecules, Ld and Kd, respectively. The predicted Ld restriction of the M83 peptide (Fig. 2B) was confirmed by the finding that M83-CTLL lysed peptide-loaded L-cell transfectants L-Ld, but not L-Dd and L-Kd (not shown; see reference 23 for proof of the Kd-restriction of M84-CTLL). Monospecificity of the CTLL is shown by the congruence between peptide-specific and CD3ɛ-redirected cytolysis (Fig. 6B).

FIG. 6.

Cytolytic activity of M83-CTLL and M84-CTLL. (A) Determination of the optimal peptide concentrations for target cell formation. As target cells for M83-CTL and M84-CTL in a cytolysis assay, P815 cells were pulsed with M83 and M84 peptides, respectively, in the indicated molar concentrations. The assay was performed at an E/T cell ratio of 20. The peptide concentrations required for half-maximal response are marked. Symbols represent the mean values of triplicate measurements. The CTL lysed only target cells that were pulsed with the cognate peptide (negative data for the heterologous peptides are not depicted). (B) Congruence between peptide-specific and CD3ɛ-redirected cytolytic activity. Cytolytic activity of CTL was measured for the indicated E/T with P815 target cells that were either pulsed with 10−9 M of the respective peptide or loaded via Fc receptor binding with MAb 145-2C11 directed against CD3ɛ.

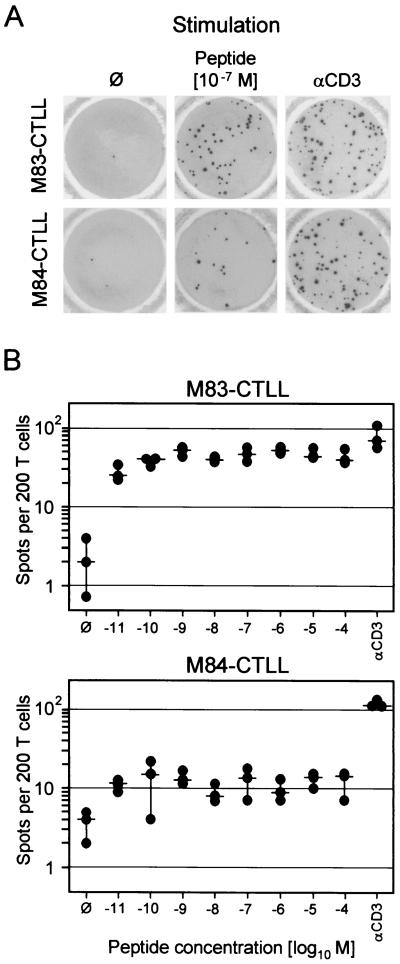

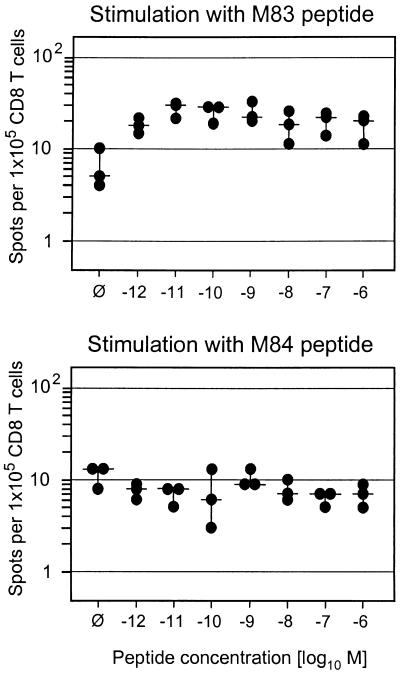

M84-CTLL are deficient in cytokine secretion after stimulation with their cognate peptide.

Since cytolytic activity and IFN-γ secretion are distinct effector functions of CD8 T cells, we investigated the capacity of M83-CTLL and M84-CTLL to secrete IFN-γ upon stimulation with their cognate peptide or after signaling enforced by anti-CD3ɛ (Fig. 7). Using IE1-CTLL as an example, we have recently documented that only a proportion of cells is in a responsive state, which was ca. 50% in the reported case, but stimulation with peptide and stimulation via CD3ɛ gave comparable results (20). In principle, this experience was now also true for M83-CTLL, even though the number of responsive cells was a bit higher with anti-CD3ɛ (Fig. 7A, top). The frequency of cells responding in the ELISPOT assay was constant over a very broad range of peptide concentrations used for pulsing of the stimulator cells (Fig. 7B, top). The results were notably different for M84-CTLL (Fig. 7A, bottom). The proportion of cells capable of responding to CD3ɛ-directed stimulation with IFN-γ synthesis and secretion was as high as observed here for M83-CTLL and previously for IE1-CTLL (20), but only 10% of these responsive cells responded also to stimulation with the M84 peptide. Again, the frequency was constant over a very broad range of peptide concentrations (Fig. 7B, bottom), indicating that peptide affinity to the presenting Kd molecule was not the limiting factor. That the M84 peptide is actually a high-affinity ligand of Kd was concluded above from the finding that a 10−12 M concentration of M84 peptide was sufficient to generate half-maximal cytolysis (Fig. 6A). As M84-CTL were found to express a normal level of surface CD8 (not shown), the results are not explainable by inefficient coreceptor binding to MHC class I. It should be noted that all responsive cells in M83-CTLL and M84-CTLL showed a T-killer type 1 cytokine phenotype in that they coexpressed IFN-γ and tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α), but not IL-4 and IL-5 (cytofluorometric data, not shown). We infer from all this information that the limiting factor is the affinity of the M84-specific TCR to the Kd-peptide complex.

FIG. 7.

Frequencies of IFN-γ-secreting cells in M83-CTLL and M84-CTLL. (A) Photodocumentation of ELISPOT filters. One representative filter of triplicate assay cultures with 200 CTL seeded is shown. ∅, P815-B7 stimulator cells with no peptide added; αCD3, stimulation with 145-2C11 hybridoma cells that produce MAb anti-mouse CD3ɛ. (B) Dose-response curves obtained by pulsing the P815-B7 stimulator cells with the indicated molar concentrations of the cognate peptides. Dots, data from triplicate assay cultures. Horizontal bars, median values.

ppM83 and pM84 are not processed after exogenous loading of the MHC class I pathway.

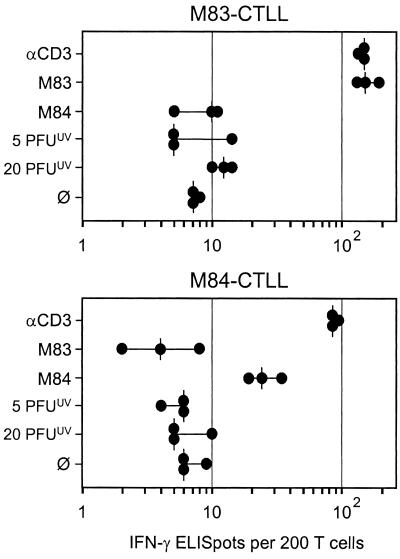

The tegument protein ppUL83 of hCMV is processed after exogenous loading of the MHC class I pathway in the absence of viral gene expression (35, 39, 55). Of its homologs pM84 and ppM83 of mCMV, only ppM83 is a virion protein (9, 36). Accordingly, only ppM83 is a candidate for exogenous loading. As shown in Fig. 4 and 5, a significant number of mCMV-specific CD8 T cells recognized virion antigens, whereas the frequency of M83 peptide-specific cells was much lower. This finding already told us that the M83 peptide is certainly not the most relevant peptide among the unidentified virion-derived peptides. However, since the cumulative response to inactivated virions may be composed of little contributions made by many CD8 T-cell clones specific for many different virion protein-derived peptides, the M83 peptide still could have been one in the crowd. If true, the M83-CTLL should detect the naturally processed and presented M83 peptide on stimulator cells that were exposed to high doses of inactivated virions. As shown in Fig. 8, M83-CTLL and M84-CTLL both recognized their cognate peptide in the ELISPOT assay, but both failed to recognize virion antigens. It should be noted that both CTLL also failed to lyse target cells that were exposed to inactivated virions with doses of up to 20 PFUUV (not shown). Accordingly, an attempt to stimulate T-cell clone S1-A, a CTL clone shown previously to recognize virion antigen (46), with the M83 peptide failed too (not shown). While these results were predictable for the M84 peptide, we learn from it that the M83 peptide too is not processed in a detectable amount after exogenous loading of the MHC class I pathway with inactivated virions.

FIG. 8.

Reactivity of CTLL in IFN-γ-based ELISPOT assays. P815-B7 stimulator cells were pulsed with peptides or exposed to the indicated doses of inactivated virions. αCD3, stimulation with 145-2C11 hybridoma cells that produce MAb anti-CD3ɛ. ∅, P815-B7 cells with no peptide added. Dots, data from triplicate assay cultures. Vertical bars, median values.

Preemptive cytoimmunotherapy of CMV disease with M83-CTLL and M84-CTLL.

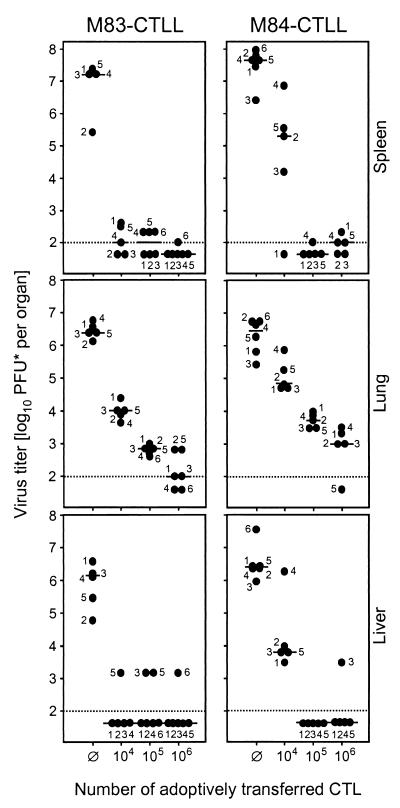

Why after all this rather disenchanting information do we think that having investigated the immune response to mCMV homologs of hCMV ppUL83 is still of interest? What really counts is the antiviral function of CD8 T cells. We have therefore tested the in vivo antiviral efficacy of M83-CTLL and M84-CTLL by adoptive transfer into recipients under experimental conditions that cause a lethal multiple-organ CMV disease unless the transferred cells are capable of controlling the infection. The results were impressive. Both cell lines were highly efficient in the protection against productive infection of a variety of host organs, including the spleen, the lungs, and the liver (Fig. 9). As few as 104 CTL significantly reduced the virus titers, with M83 peptide-specific CTL having been a bit more effective in this particular experiment. However, one should not overinterpret the difference between the two CTLL, as it is impossible to synchronize different CTLL in such a way that they reach identical activity on the day of transfer. The bottom-line information therefore is that both CTLL were highly antiviral.

FIG. 9.

In vivo antiviral function of M83 and M84 peptide-specific CTLL. Graded numbers of CTL were transferred intravenously into female BALB/c recipients under lethal conditions of infection (6.5 Gy of total-body gamma-irradiation followed by intraplantar infection with 105 PFU of mCMV). ∅, no adoptive cell transfer. Virus titers in homogenates of spleen, lung, and liver were determined at day 12 after infection. The virus plaque assay was performed under conditions of centrifugal enhancement of infectivity. Accordingly, titers of infectious virus are expressed as PFU*. Dots, virus titers in numbered individual mice. Horizontal bars, median values. Dotted line, detection limit of the plaque assay.

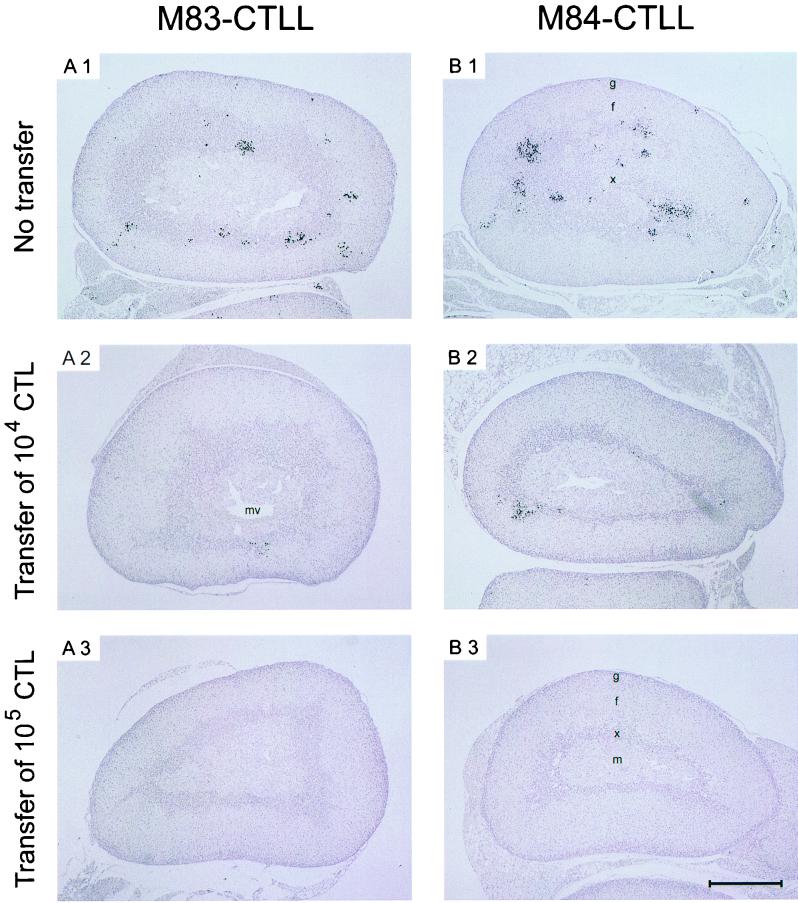

For demonstrating the antiviral effect in situ, we have chosen the suprarenal gland, because this organ is small enough to allow the documentation of whole-organ sections. This avoids selection of sites of interest and gives the reader an unbiased impression of the extent of organ infection. Nuclei of infected cells were stained black by immunohistology specific for the intranuclear IE1 protein. In the absence of protective T cells (Fig. 10A1 and B1), mCMV replicated and generated large foci, preferentially in the juxtamedullary X zone of the inner cortex.

The X zone of the mouse adrenals is a genetically determined, sex- and age-dependent site of steroid synthesis (11, 18). It is fully developed only in juvenile female mice before the first pregnancy. Preferential replication of mCMV in the X zone is a side aspect of this work. Here we just wish to say that this localization does not result from a particular tropism of mCMV for X zone cells, because in other stages of mCMV disease the medulla and outer cortex were found to be strongly infected (17, 41, 47). More probably, the X zone is the site of virus entry into the tissue via fenestrated capillaries whose pore diameters increase from 100 nm in the outer cortex to more than mCMV virion size, namely to 250 nm, in the inner cortex.

Most importantly, the number of infectious foci in this X zone was reduced by transfer of 104 CTL (Fig. 10A2 and B2), and infection was completely prevented by the transfer of 105 CTL (Fig. 10A3 and B3).

DISCUSSION

The prominent role of the tegument protein ppUL83 in the immune response of humans to hCMV (14, 35, 67) has raised interest in mCMV homologs for experimental research in the mouse, addressing questions that are not easily accessible to clinical research. Specifically, the importance of ppUL83 for immunity to hCMV is concluded from the abundance of ppUL83 peptide-specific CD8 T cells in persons of various HLA haplotypes (for a review, see reference 44). Whether the quantitative immunodominance really reflects a benefit in terms of protection against CMV disease is less established. In fact, recent work by Gillespie et al. (14) has associated the high frequency of activated ppUL83-specific T cells with frequent reactivation of hCMV. In reverse interpretation, the T cells were apparently unable to prevent reactivations. Even though longevity of adoptively transferred immune cells and low incidence of CMV disease in BMT patients who had received ppUL83-specific CD8 T-cell cytoimmunotherapy was indeed encouraging (56, 64), there is, in a formal sense, no firm evidence for antiviral protection mediated by the transferred cells. Since CD8 T cells of other specificities, for instance IE1-specific CD8 T cells (for a review, see reference 44), were not yet considered for clinical cytoimmunotherapy, the role of different hCMV antigens in antiviral immunity cannot be comparatively evaluated. Admittedly, such studies are difficult to perform in clinical settings. Murine models can help to provide proof of evidence.

Very detailed studies conducted by the group of D. H. Spector (9, 36, 37) have identified the M82-M84 gene family in mCMV and have unraveled its phylogenetic relation to the positional homologs UL82-UL84 in hCMV. On the basis of amino acid identities, M83 and M84 were both classified as sequence homologs of UL83, with M84 being somewhat closer in this respect than the positional homolog M83. The corresponding proteins were characterized as ppM83 (105 kDa; pp105) and pM84 (65 kDa; p65), respectively. Even though somewhat attenuated for growth in vivo, deletion mutants mCMV-ΔM83 and mCMV-ΔM84 were viable and established latency (36). When used for immunization against lethal challenge infection, the parental mCMV and the two deletion mutants provided similar levels of protection. One must infer from this result that neither of the two genes is indispensable for the induction of a protective immune response. This is probably true also for the immunodominant UL83 of hCMV, but of course the corresponding ΔUL83 mutant of hCMV, mutant RVAd65 (58), cannot be tested in immunization-challenge experiments. Clearly, there is redundancy in protection-generating viral proteins. Specifically, the IE1 proteins of mCMV and hCMV account for antigenic peptides (reviewed in reference 44), and antiviral protection mediated by IE1-specific CD8 T cells is proven for mCMV by adoptive cell transfer (22), by immunization with recombinant vaccinia viruses expressing IE1 protein (27) or expressing just the IE1 nonapeptide (10), and by genetic immunization with an ie1 expression plasmid (15). On the other hand, IE1 of mCMV is also dispensable for protection. Mutant BALB/c H-2dm2 mice, which lack the Ld gene and are thus unable to present the IE1 peptide (the only antigenic peptide of IE1 presented in H-2d) (10, 31; Holtappels, unpublished), can control mCMV infection. Antiviral CD8 T cells generated in the mutant strain protect against lethal mCMV disease upon adoptive transfer into indicator recipients of mutant and parental genotypes (1). In accordance with these findings, gp34 of mCMV encoded by the E-gene m04 (30) was recently shown to account for an antigenic peptide presented by Dd and to be capable of inducing protective CTL (22). It was therefore worthwhile studying the immunogenic capacities of further proteins.

Antigenicity of pM84.

That pM84 is a protection-generating protein of mCMV in the H-2d haplotype has been demonstrated by genetic immunization of BALB/c mice with an M84 expression plasmid followed by challenge infection, and this result was confirmed by immunization with recombinant vaccinia virus M84-vacc (37). Notably, however, despite its closest amino acid sequence homology to hCMV ppUL83 among the three members of the M82-84 protein family, pM84 is not the mCMV counterpart of hCMV ppUL83. It differs from ppUL83 in that it is not a component of the virion, is not phosphorylated, and is expressed with E-phase kinetics (36). We have here confirmed the E-phase kinetics of M84 gene expression. With the sensitivity of RT-PCR, the transcripts were already detectable at 2 h postinfection of MEF and were absent when the infection was performed in presence of metabolic inhibitors actinomycin D or cycloheximide. Thus, M84 mRNA does not enter the cells during penetration of the virions (7) and its synthesis is dependent upon prior viral protein synthesis. No doubt, M84 is an E gene, and according to Western blot data, the protein also is detectable in the E phase (36). Antigenicity of pM84 was confirmed previously by the identification of an antigenic peptide presented by the MHC class I molecule Kd (23). The data shown here might suggest that the M84 peptide 297AYAGLFTPL305 is not involved in the immune response to mCMV infection. Specifically, neither in the draining PLN during acute infection nor in memory spleen cell populations primed by different modes of primary infection could M84 peptide-specific CD8 T cells be identified with cytokine (IFN-γ) synthesis-based assays. Yet, it is worth recalling that the M84 peptide was originally defined by CTL activity after several rounds of in vitro restimulation of memory spleen cells, whereas an IFN-γ-based ex vivo ELISPOT screening of predicted motifs had failed to uncover this antigenic peptide (23). The properties of the M84-CTLL give an important hint that may explain the low IFN-γ-defined frequencies of M84 peptide-specific cells. Specifically, M84-CTLL showed a high cytolytic activity against target cells presenting the peptide. In accordance with the high score of the M84 peptide in the prediction of MHC class I binding (Fig. 2B), a high affinity to the presenting Kd molecule was indicated by the very low molar concentration of the peptide required for target cell formation. In contrast, only a minority of the cells of the M84-CTLL secreted IFN-γ in an amount sufficient for detection in the ELISPOT assay after stimulation via the TCR with the cognate ligand, even though the unresponsive cells were able to secrete IFN-γ upon direct stimulation via the signal-transducing CD3ɛ molecule. A likely explanation is that the M84-specific TCR has a low affinity for the peptide-Kd complex. This low-affinity binding suffices for triggering target cell lysis but leads to inefficient signaling for the synthesis of IFN-γ. We believe that our experience with the antigenicity of pM84 is of more general relevance. There is currently a lot of enthusiasm praising the elegance of cytokine-based high-throughput peptide-screening methods, such as intracellular cytokine cytofluorometry (28). However, as exemplified here for M84, relevant antigenic peptides can be missed in cytokine-based assays.

Antigenicity of ppM83.

In contrast to pM84, the gene product ppM83 (pp105) of the positional homolog M83 of hCMV UL83 resembles ppUL83 (pp65) by virtue of its expression kinetics, phosphorylation, and virion association (9). It was thus predicted that ppM83 may also resemble ppUL83 with respect to immunogenicity. Yet, to some surprise, ppM83 did not mediate protection when expressed for immunization in BALB/c mice by an expression plasmid or by recombinant vaccinia virus M83-vacc (37). These data had thus indicated a major difference between ppM83 of mCMV and ppUL83 of hCMV. To be more precise one must specify that the results cited for mCMV refer to mCMV strain K181. As we have shown herein, ppM83 of mCMV strain Smith contains an antigenic peptide that is presented by the MHC class I molecule Ld. Unlike the M84 peptide, it was identifiable by the induction of IFN-γ secretion in an ELISPOT assay. While the frequencies of M83 peptide-specific CD8 T cells during acute infection and after establishment of immunological memory were not impressively high when compared to the number of cells specific for the immunodominant IE1 peptide, the existence of memory cells with that specificity implies that ppM83 expressed in the course of in vivo mCMV infection was able to prime for a response. As was shown recently in a model of CMV pneumonia after experimental BMT (40), M83 peptide-specific CD8 T cells are generated during acute mCMV infection and are recruited to a nonlymphoid tissue site of inflammation and antiviral control (20). Among the four antigenic peptides of mCMV known to date, the M83 peptide ranks second best after IE1 in its immunogenicity (reference 20 and this report). Accordingly, we had no difficulties in establishing a long-term CTLL. Unlike the M84-CTLL, the M83-CTLL was not only highly cytolytic but also efficient in secreting IFN-γ upon stimulation with the cognate ligand. We therefore saw no obvious reason for a failure in antiviral protection.

The M83 peptide YPSKEPFNF spans aa 761 to 769 in the C-terminal portion of the 809-aa protein ppM83 of mCMV strain Smith. A critical mutation in mCMV strain K181, in particular one affecting the MHC anchor residues, could have explained the discrepant data. However, a comparison of the sequences of GenBank accession no. MCU68299 (Smith) and MCU65003 (K181) does not reveal any amino acid exchange in the peptide sequence or in its closer neighborhood. However, there exist a few distant mutations. For instance, M83 Smith consists of 809 instead of 807 aa due to an insertion of Asp-Glu after position aa 549 of the Smith sequence. As a consequence, the putative M83 peptide of strain K181 would span the length from aa 759 to 767. A failure in generating the antigenic peptide in K181 could theoretically result from an altered cleavage pattern at the proteasome. Far-range effects of distant mutations on the generation of an antigenic peptide are difficult to assess with currently used algorithms for predicting proteasomal cleavages. The computer program PAProC (included in SYFPEITHI, version 1.0; http://www.uni-tuebingen.de/uni/kxi/) did not reveal differences in proteasomal cleavage sites relevant to the generation of the M83 peptide, and the computer program POCS (24, 25) predicted that the M83 peptide is generated in both strains with a probability of >90% (P.-M. Kloetzel, personal communication).

In strain K181, ppM83 has been characterized as an L-phase protein (9). We have here detected M83 transcripts already at 2 h postinfection, identifying M83 of strain Smith as an E-phase gene. Whether this difference reflects a true difference in the expression kinetics of gene M83 in the two strains or just results from the higher sensitivity of RT-PCR as compared with direct Northern blot analysis is open to further investigation. We wish to emphasize that identification of M83 as an E-phase gene does by no means interfere with the previous finding that the bulk of ppM83 protein synthesis, as determined by Western blotting, occurs late (9). In conclusion, the comparison of the amino acid sequences did not offer an explanation for the immunological differences.

Even though the virion protein ppM83 of mCMV is now identified as an immunogenic protein, the data have also revealed that it clearly differs from ppUL83. There is no doubt that ppUL83 can enter the MHC class I pathway after virion penetration and uncoating. As a consequence, antigenic peptides derived from incoming tegument ppUL83 can be generated and presented in the absence of viral gene expression (35, 39, 55). Our experiments, as shown in Fig. 8 in particular, indicate that this mechanism does not apply to ppM83. It is established that most of the ppUL83 in hCMV preparations is contained in enveloped subviral particles, the DBs, and is delivered into the cytosol by fusion of the DB envelope with the cell membrane (26, 39, 57, 62). Since mCMV does not produce significant amounts of DBs, one might speculate that this morphogenetic difference between the two viruses accounts for the observed difference in the immunodominance of ppUL83 and ppM83. Absence of DBs in mCMV does not mean that exogenous loading of the MHC class I pathway with virion proteins plays no role in the immune response to mCMV. In fact, generation of target cells in the absence of viral gene expression by exogenous loading with virion proteins was originally described for mCMV. Specifically, polyclonal CTL (49, 50) as well as cloned CTLL (46) was found to lyse target cells that had been exposed to UV-inactivated virions or had been infected in the presence of metabolic inhibitors. We have here reproduced these previous findings with the modern technology of an ELISPOT assay using stimulator cells that were exposed to UV-inactivated virions. Notably, as shown previously with limiting-dilution CTL assays (50), the frequencies of responding cells increased with increasing doses of virions. This is not a trivial observation. One possibility is that a higher presentation density of a virion-derived, still unknown peptide recruits more responding cells with low-affinity TCRs. Alternatively, and in our opinion more likely, virion proteins could account for several still unknown antigenic peptides. In that case, antigenic peptides derived from quantitatively prominent virion proteins would already be generated in a sufficient amount after low-dose loading, while rare virion proteins would contribute to the response only after high-dose loading. In either case, the M83 peptide is not among virion-derived antigenic peptides.

Protection by preemptive cytoimmunotherapy with CD8 T cells specific for subdominant peptides.

In essence, neither ppM83 nor pM84 was immunodominant in either the acute immune response or the memory state. However, the hierarchy of antigens in a natural immune response to infection is mainly determined by different efficacies in priming the response (for current opinion, see reference 68). This hierarchy does not necessarily correlate with protective capacity (13). Protection depends on the efficacy of the effector cells in migrating to inflammatory sites and delivering their antiviral effector function there, as well as on efficient presentation of the antigenic peptides in the tissues and by the cell types that are relevant to viral pathogenesis. In cases in which the natural immune response is not fully protective, it may even be desirable as a vaccination strategy to boost the response to subdominant antigens in order not to just reproduce the inefficient natural immune response but to engineer a new quality of immunity. Specifically, T-cell anergy induced by immunodominant peptides expressed during chronic infection can only be bypassed by immunization with subdominant peptides. There are precedents in the literature documenting protective cellular antiviral immunity induced by subdominant peptides (12, 38).

We have here tested the in vivo antiviral effector qualities of M83-CTLL and M84-CTLL specific for mCMV homologs of the hCMV virion protein ppUL83. Irrespective of the fact that only ppM83 is a virion protein, both cell lines proved to be highly efficient in preventing virus replication in a variety of target tissues of lethal CMV disease. Notably, the deficiency of M84-CTLL in secreting IFN-γ upon stimulation with the cognate ligand did not destroy its antiviral in vivo function.

Conclusion.

It is established that the tegument protein ppUL83 of hCMV elicits a quantitatively dominant CD8 T-cell response. In clinical trials of an adoptive cytoimmunotherapy of hCMV disease, ppUL83-specific CD8 T cells were chosen with the rationale that abundance reflects functional importance. One could also think the other way round; abundance might rather indicate a low efficiency in controlling infection. If CD8 T cells of a particular specificity were highly effective, why should high numbers be needed? More logically, low numbers should then suffice for resolving productive infection. We have shown here that ppM83 and pM84 of mCMV do not prime a quantitatively dominant response. Yet, nevertheless or because of that, CTLL with these specificities were highly effective in cytoimmunotherapy. The bottom-line message is that there no longer exists a rationale for considering only immunodominant antigens as candidates for immunotherapy or immunoprophylaxis of CMV infection.

FIG. 10.

Clearance of infection in the suprarenal gland by cytoimmunotherapy with M83 and M84 peptide-specific CTLL. IHC analysis specific for the intranuclear IE1 protein pp89 of mCMV (black staining) was performed on whole-organ sections of the suprarenal glands of the same mice for which virus titers in other organs are documented in Fig. 9. (A1 and B1) Infection in the absence of protective CTL. Protection is mediated by adoptive transfer of 104 (A2 and B2) and 105 (A3 and B3) cells of M83-CTLL and M84-CTLL, respectively. Letters g and f, zona glomerulosa (underneath the capsule) and zona fasciculata of the outer cortex, respectively; x, X zone or inner (juxtamedullary) cortex; m, medulla. The X zone is particularly developed in virgin mice used as recipients in our experiments. The zona reticularis, a tiny cell layer located between the zona fasciculata and the X zone, is not discernible in the sections. mv, medullary vein. Foci of infected cells are located preferentially in the X zone that is demarcated by a more intense hematoxylin staining of dense nuclei. Single foci are found in the outer cortex as well as in the brown fat tissue that is attached to the suprarenal glands. The section shown in B1 does not include the medulla, and therefore its central part represents a large area of the X zone. All sections are shown at the same magnification. Bar, 0.5 mm.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Aysel Rojan for technical assistance with the immunohistological analysis and Doris Dreis for assistance with the analysis of gene expression. Stefan Stevanovic and Alexander Nussbaum (both from the Institute for Cell Biology, Department of Immunology, University of Tübingen, Tübingen, Germany) helped us regarding computer programs SYFPEITHI and PAProC. Peter-Michael Kloetzel and Hermann-Georg Holzhütter (both from the Institute for Biochemistry, Humboldt University, Berlin, Germany) helped us by analyzing M83 sequences for proteasomal cleavage fragments with their computer program POCS.