Abstract

Background

Pre-existing comorbidities increase the likelihood of post-stroke dysphagia. This study investigates comorbidity prevalence in patients with dysphagia after ischemic stroke.

Methods

The data of patients with acute ischemic stroke from two large representative cohorts (STROKE-CARD trial 2014–2019 and STROKE-CARD registry 2020–2022 – both study center Innsbruck, Austria) were analyzed for the presence of dysphagia at hospital admission (clinical swallowing examination). Comorbidities were assessed using the Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI).

Results

Of 2054 patients with ischemic stroke, 17.2% showed dysphagia at hospital admission. Patients with dysphagia were older (77.8 ± 11.9 vs. 73.6 ± 14.3 years, p < 0.001), had more severe strokes (NIHSS 7(4–12) vs. 2(1–4), p < 0.001) and had higher CCI scores (4.7 ± 2.1 vs. 3.8 ± 2.0, p < 0.001) than those without swallowing impairment. Dysphagia correlated with hypertension (p = 0.034), atrial fibrillation (p < 0.001), diabetes (p = 0.002), non-smoking status (p = 0.014), myocardial infarction (p = 0.002), heart failure (p = 0.002), peripheral arterial disease (p < 0.001), severe chronic liver disease (p = 0.002) and kidney disease (p = 0.010). After adjusting for relevant factors, the associations with dysphagia remained significant for diabetes (p = 0.005), peripheral arterial disease (p = 0.007), kidney disease (p = 0.014), liver disease (p = 0.003) and overall CCI (p < 0.001).

Conclusions

Patients with multiple comorbidities have a higher risk of developing post-stroke dysphagia. Therefore, early and thorough screening for swallowing impairment after acute ischemic stroke is crucial especially in those with multiple concomitant diseases.

Trial registration

Stroke Card Registry (NCT04582825), Stroke Card Trial (NCT02156778).

Keywords: Dysphagia, Swallowing impairment, Ischemic stroke, Comorbidities, Risk factors

Background

Stroke continues to be one of the leading causes of death worldwide, with the highest age-standardised mortality rates in low-income countries (as defined by the World Bank) [1, 2]. Swallowing impairment following ischemic stroke leads to serious complications and less favourable outcomes [3]. Early detection of dysphagia in the post-acute phase of ischemic stroke significantly reduces the incidence of pulmonary infections [4]. Therefore, various important predictors for post-stroke dysphagia have been investigated in the past [5]. Especially higher stroke severity and older age were identified as key contributors to the development of dysphagia [5]. Also pre-existing comorbidities, such as diabetes mellitus and arterial hypertension, were associated with an increased likelihood of swallowing impairment after ischemic stroke [6, 7]. Little is known about the impact of other comorbidities.

In this comprehensive study involving 2054 patients, we aim to investigate the prevalence of various comorbidities and their potential impact on the development of dysphagia after ischemic stroke.

Methods

Secondary analysis of prospectively collected data from two large stroke cohorts from the study center Innsbruck, Austria, was performed: The STROKE-CARD trial (SCT) (NCT02156778) from 2014–2019 and the STROKE-CARD registry (SCR) (NCT04582825) from 2020–2022. The STROKE-CARD program represents the post-stroke disease management initiative of the Medical University of Innsbruck and the St. John of God Hospital in Vienna, Austria, which effectively reduces the cumulative risk of cardiovascular events and improves health-related quality of life of patients with ischemic stroke or high-risk transient ischemic attack (TIA) [8]. All patients (≥ 18 years of age) admitted to the Department of Neurology of the University Hospital of Innsbruck, who gave written informed consent and lived inside the catchment area of the study center (Tyrol, Austria), were included. Exclusion criteria for the STROKE-CARD trial only were, a) estimated life expectancy < 1 year, (b) drug or alcohol addiction or (c) severe persistent disability with poor prognosis of successful rehabilitation (modified Rankin Scale [mRS] score of 5 at hospital discharge). A total of 2% (n = 60), 1% (n = 35) or 9% (n = 243) of potentially eligible patients were not included due to these exclusion criteria. No exclusion criteria applied for participation in the STROKE-CARD registry. All study participants or their legal guardian had to give informed consent at baseline or at the 3-month follow-up visit. A total of 92.2% and 87.5% of patients who fulfilled the inclusion criteria participated in the STROKE-CARD trial and the STROKE-CARD registry, respectively.

Patient data including demographic factors, presence of comorbidities such as diabetes, atrial fibrillation, arterial hypertension, dyslipidemia and obesity (body mass index ≥ 25) and clinical measures such as stroke severity (National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale NIHSS [9]) as well as disability (modified Rankin Scale mRS) [10] were recorded at baseline. We identified comorbidities in a face-to-face interview and information of the digital health record using the Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI) [11]. This index was validated in the context of ischemic stroke [12]. A pre-existing or at the time of hospitalization existing diagnosis of myocardial infarction (according to the Fourth Universal Definition of Myocardial Infarction 2018) [13], heart failure (with reduced ejection fraction ≤ 49%), peripheral arterial disease (symptoms and measured ancle brachial index ABI < 0,9), previous ischemic cerebral infarction, known dementia (clinical diagnosis based on DSM-V criteria), chronic pulmonary disease (asthma or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease), rheumatologic diseases (such as rheumatoid arthritis, lupus erythematosus, among others), history of gastric ulcers, chronic liver disease (mild: chronic hepatitis or cirrhosis without portal hypertension; moderate-to-severe: cirrhosis with portal hypertension with/without variceal bleeding), diabetes mellitus type 2 (with or without end organ damage combined), moderate-to-severe chronic renal insufficiency (creatinine > 3 mg per deciliter), pre-existing hemiplegia or paraplegia, Acquired Immunodeficiency Syndrome (AIDS), or tumor disease (solid tumors with or without metastases within the last 5 years, leukemia, lymphoma) were collected. The CCI assigns different score points for the presence of different comorbidities and age groups (termed ‘age-adjusted CCI’) ranging from 0 to 37: Maximum six points were scored for a metastatic tumor or AIDS, three points for moderate-to-severe liver disease and two points for hemiplegia/paraplegia, chronic kidney disease, diabetes with end-organ damage, tumor without metastases, leukemia and lymphoma; the remaining diseases were each rated with one point. Additional points were given depending on age: over 80 years 4 points, 70–79 years 3 points, 60–69 years 2 points and 50–59 years 1 point. In sensitivity analyses we used the CCI without scoring for age ranging from 0 to 33 (‘unadjusted CCI’).

Dysphagia was defined as newly developed inability to swallow at hospital admission. As part of routine clinical practice, all patients were screened for possible swallowing disorders upon admission. Dysphagia was diagnosed through a clinical swallowing examination conducted by speech and language therapists. If needed, this examination was supplemented by additional diagnostic procedures, such as a fibreoptic endoscopic evaluation of swallowing.

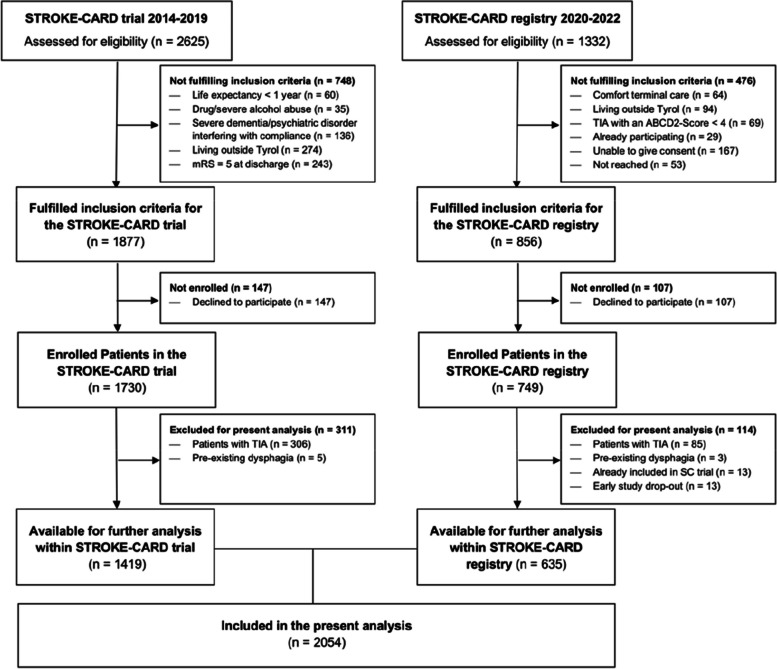

After exclusion of those with TIA as an index event (SCT n = 306; SCR n = 85), a total of 2075 patients with ischemic stroke from both cohorts (SCT n = 1424; SCR n = 664) were available for further analysis at the study center Innsbruck in October 2022. After the exclusion of 8 patients with pre-existing dysphagia (SCT n = 5; SCR n = 3) and those patients from the SCR cohort who were already included in the SCT cohort (SCR n = 13) or had insufficient data because of an early study drop-out (SCR n = 13), 2054 patients remained for further analysis.

Both STROKE-CARD studies (SCR and SCT) received approval from the local ethics committee of the Medical University of Innsbruck. All required patient consents were obtained, and the corresponding institutional forms were archived.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics such as mean and standard deviation or median and interquartile range were used to analyze various characteristics. Comparisons between subgroups were performed using Pearson’s chi-square for binary and nominal variables and the Mann–Whitney U-test for continuous data. Data missing was indicated where appropriate. Significant differences between the groups (dysphagia yes/no) were initially determined using univariate comparisons and subsequently assessed using multivariable logistic regression. Three models were utilized: model 1 (age, sex, NIHSS, study cohorts, arterial hypertension, atrial fibrillation and smoking), model 2a (age-adjusted CCI, sex, NIHSS, study cohorts, arterial hypertension, atrial fibrillation and smoking) and model 2b (unadjusted CCI, age per 10-years, sex, NIHSS, study cohorts, arterial hypertension, atrial fibrillation and smoking). The significance level was set at p < 0.05 and false discovery rate adjustment accounted for multiple testing (SPSS version 27.0.1.0; IBM Corporation, Armonk, New York).

Results

In a total of 2054 patients with acute ischemic stroke (detailed study description shown in Fig. 1), of which 38.9% were women, dysphagia was present in 17.2% of patients (SCT 16.6% vs. SCR 18.6%, p = 0.279). Except for age (mean + SD in SCT 75.8 ± 14.1 vs. SCR 71.0 ± 13.2 years, p < 0.001), no significant differences were found between the two cohorts.

Fig. 1.

Study flow-chart (Study center Innsbruck)

In the cohorts analyzed, patients with dysphagia were older (p < 0.001), had a higher stroke severity (NIHSS, p < 0.001) and a significantly higher Charlson Comorbidity Index CCI (p < 0.001). In addition, patients with dysphagia had higher rates of atrial fibrillation (p < 0.001), arterial hypertension (p = 0.034) and were less likely currently smoking (p = 0.014) – shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Differences in characteristics of patients with or without dysphagia at hospital admission

|

All Patients (n = 2054) |

Dysphagia (n = 354) |

No Dysphagia (n = 1700) |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| percentage (%), mean ± SD or median (IQR) | P valuea | |||

| Female sex | 38.9% | 41.8% | 38.4% | 0.225 |

| Age | 74.3 ± 14.0 | 77.8 ± 11.9 | 73.6 ± 14.3 | < 0.001 |

| NIHSS, admission | 3 (1–6) | 7 (4–12) | 2 (1–4) | < 0.001 |

| mRS, admission | 3 (2–4) | 4 (3–5) | 2 (2–3) | < 0.001 |

| CCI (unadjusted) | 1.1 ± 1.4 | 1.5 ± 1.8 | 1.0 ± 1.3 | < 0.001 |

| CCI (age-adjusted) | 4.0 ± 2.0 | 4.7 ± 2.1 | 3.8 ± 2.0 | < 0.001 |

| Smoking | 22.5% | 17.5% | 23.5% | 0.014 |

| Obesity* | 18.3% | 16.3% | 18.7% | 0.292 |

| Arterial hypertension | 78.9% | 83.1% | 78.0% | 0.034 |

| Dyslipidemia | 82.8% | 79.9% | 83.4% | 0.116 |

| Atrial fibrillation | 23.5% | 34.2% | 21.8% | < 0.001 |

CCI Charlson comorbidity index, SD Standard deviation, IQR Interquartile range, NIHSS National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale, mRS Modified Rankin scale

*n = 2020 (missing data in 34 patients; 5 with Dysphagia, 29 without Dysphagia)

ap values for difference between those with and without dysphagia. After adjusting for multiple testing (using false discovery rate), a p value ≤ 0.034 can be considered statistically significant

In the multivariable logistic regression (model 1 including age, sex, NIHSS, study cohorts, arterial hypertension, atrial fibrillation and smoking), both NIHSS (p < 0.001; OR 1.19 [1.16, 1.22] per 1-point increase in NIHSS) and age (p < 0.001; OR 1.02 [1.01, 1.03] per 1-year increase in age) remained independently linked to dysphagia. The association with arterial hypertension, atrial fibrillation and smoking did not persist independently of other covariates (data not shown).

When comparing the prevalence of individual components of the CCI in ischemic stroke patients with and without dysphagia at hospital admission, patients with dysphagia were significantly more likely to have a history of myocardial infarction (p = 0.002), heart failure (p = 0.002), peripheral arterial disease (p < 0.001), diabetes mellitus (p = 0.002), moderate-to-severe liver disease (p = 0.002) and moderate-to-severe kidney disease (p = 0.010), as shown in Table 2. Although various comorbidities (dementia, leukemia and metastatic solid tumor) tended to be more common in patients with dysphagia, the association was not statistically significant after adjustment for multiple testing.

Table 2.

Charlson Comorbidity index in patients with or without dysphagia

| All Patients (n = 2054) | Dysphagia (n = 354) | No Dysphagia (n = 1700) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Percentage (%) | Unadjusted p value* | Adjusted p valuea | |||

| Charlson Comorbidity Index | |||||

| Myocardial infarction | 10.6% | 15.3% | 9.7% | 0.002 | 0.052 |

| Heart failure | 9.6% | 14.1% | 8.7% | 0.002 | 0.214 |

| Peripheral arterial disease | 9.2% | 14.1% | 8.1% | < 0.001 | 0.007 |

| History of ischemic stroke | 12.9% | 14.1% | 12.6% | 0.432 | 0.627 |

| Dementia | 2.9% | 4.8% | 2.5% | 0.017 | 0.153 |

| Chronic pulmonary disease | 6.5% | 8.2% | 6.1% | 0.149 | 0.464 |

| Rheumatologic disease | 2.0% | 2.3% | 1.9% | 0.697 | 0.414 |

| Peptic ulcer disease | 3.6% | 4.0% | 3.5% | 0.654 | 0.620 |

| Mild liver disease | 1.0% | 0.6% | 1.1% | 0.389 | 0.397 |

| Moderate-to-severe liver disease | 0.7% | 2.0% | 0.5% | 0.002 | 0.003 |

| Diabetes | 19.6% | 25.7% | 18.4% | 0.002 | 0.005 |

| Moderate-to-severe CKD | 1.8% | 3.4% | 1.4% | 0.010 | 0.014 |

| Hemiplegia or paraplegia | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | ––– | ––- |

| Cancer without metastasis | 5.9% | 6.2% | 5.9% | 0.810 | 0.950 |

| Leukemia | 0.3% | 0.8% | 0.2% | 0.033 | 0.029 |

| Lymphoma | 0.5% | 0.6% | 0.5% | 0.816 | 0.701 |

| Metastatic solid tumor | 0.4% | 1.1% | 0.3% | 0.030 | 0.037 |

| AIDS | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.1% | 0.648 | ––- |

CKD Chronic kidney disease, AIDS Acquired immune deficiency syndrome

*p-values for the difference between those with and without dysphagia. Adjusted for multiple testing (false discovery rate), a p-value ≤ 0.014 can be considered significant with an alpha error of 0.05

aadjusted p-value for age, sex, NIHSS, study cohorts, arterial hypertension, atrial fibrillation and smoking (model 1) using logistic regression

Adjusted for age, sex, NIHSS, study cohorts, arterial hypertension, atrial fibrillation and smoking (model 1), diabetes mellitus (p = 0.005), moderate-to-severe liver disease (p = 0.003), peripheral arterial disease (p = 0.007) and moderate-to-severe kidney disease (p = 0.014) remained independently associated with dysphagia (Table 2).

The age-adjusted CCI demonstrated a significant and independent association with dysphagia (p < 0.001; OR 1.23 [1.15, 1.32] per 1-point increase in CCI) – model 2a (shown in Table 3). When age was included in the analysis (model 2b), the unadjusted CCI exhibited a similar association with dysphagia (p < 0.001, OR 1.22 [1.12, 1.32] per 1-point increase in CCI) as the age-adjusted CCI. Additionally, when substituting the NIHSS with the modified Rankin Scale (mRS) as a measure of initial stroke severity or when including stroke type in the multivariable regression model, comparable results were observed (data not shown). Further sensitivity analyses limiting the cohort to patients aged 55 and older yielded similar results.

Table 3.

Multivariable adjusted odds ratios for post-stroke dysphagia

| Multivariable Model 2a | Multivariable Model 2b | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| p value | OR (95% CI) | p value | OR (95% CI) | |

| CCI (age-adjusted) | < 0.001 | 1.23 (1.15, 1.32) | –- | –- |

| NIHSS, admission | < 0.001 | 1.19 (1.16, 1.22) | < 0.001 | 1.19 (1.16, 1.22) |

| Female sex | 0.782 | 1.04 (0.80, 1.34) | 0.865 | 1.02 (0.79, 1.33) |

| Study cohort (SCR) | 0.094 | 1.26 (0.96, 1.66) | 0.073 | 1.29 (0.98, 1.71) |

| Smoking | 0.279 | 0.83 (0.60, 1.16) | 0.338 | 0.85 (0.60, 1.19) |

| Arterial hypertension | 0.390 | 1.17 (0.82, 1.68) | 0.396 | 1.17 (0.81, 1.69) |

| Atrial fibrillation | 0.332 | 1.15 (0.87, 1.54) | 0.393 | 1.14 (0.85, 1.52) |

| Age (per 10-years) | –- | –- | < 0.001 | 1.22 (1.12, 1.32) |

| CCI (unadjusted) | –- | –- | 0.001 | 1.21 (1.08, 1.36) |

Discussion

In our secondary analysis of a large representative cohort of ischemic stroke patients we are able to confirm previously established predictors of swallowing impairment as a consequence of acute ischemic stroke, like age and stroke severity [5–7]. Furthermore, we demonstrate a clear correlation between various selected comorbidities and post-stroke dysphagia.

The Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI), a well-established and validated tool to quantify comorbidities combined with age in stroke research, showed an independent association with post-stroke dysphagia. Other cardiovascular comorbidities and lifestyle factors not covered by this index such as arterial hypertension, dyslipidemia, obesity, smoking and atrial fibrillation are not independently associated with swallowing impairment in our cohort.

The mean CCI values in our cohort were consistent with previous studies, including one study focused on post-stroke depression that reported similar CCI values among stroke patients with and without dysphagia [14, 15].

Looking at individual comorbidities included in the CCI, differences in patients with and without dysphagia in acute ischemic stroke emerged for pre-existing cardiovascular diseases (myocardial infarction, heart failure, and peripheral artery disease), diabetes mellitus, moderate-to-severe liver disease as well as moderate-to-severe chronic kidney disease. After adjusting for age, sex, NIHSS, study cohorts, arterial hypertension, atrial fibrillation, smoking (and stroke type including small vs. large-vessel disease – data not shown), significant associations with myocardial infarction and heart failure were lost.

The association with diabetes has been well described previously [6, 7], and is most likely linked to a higher probability of atherosclerotic microangiopathy – which is known to increase the risk for dysphagia in patients with small subcortical strokes [16]. This could be attributed to the subclinical damage to the swallowing neuronal network and an elevated risk of insufficient compensatory capacity following an acute stroke, as observed in older adults [17]. This hypothesis is consistent with our findings that atherosclerotic cardiovascular diseases, especially peripheral artery disease, as well as chronic kidney disease – which is known as a systemic manifestation of atherosclerotic microangiopathy [18] – appear to be linked to dysphagia, possibly through a similar pathophysiological mechanism. We are the first to report an association of stroke related dysphagia with chronic liver disease. One can only speculate about the underlying processes. Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease is strongly associated with vascular risk factors [19] and hepatic insufficiency can lead to chronic brain injury [20, 21]. In addition, higher serum bilirubin levels appear to play a role in the pathophysiology and severity of ischemic stroke [22].

In our study, we could not confirm other factors that have been postulated previously like sex [7] or hypertension [6]. The link between sex and post-stroke dysphagia emerged in the meta-analysis that also included hemorrhagic stroke patients [7] and was not found in the meta-analysis with ischemic stroke patients only [6]. Moreover, the association between dysphagia and arterial hypertension was not independent of important covariates in our cohort.

The main limitation of our study comes from the diagnosis of dysphagia, that was mainly based on screening tests and clinical swallowing examination, which is known to result in lower prevalence rates (13–49% [6]) of post-stroke dysphagia than in studies using instrumental diagnostics (64–78% [23]). Furthermore, we do not have sufficient details on stroke localization or stroke volume to explore its impact on prevalence of dysphagia. Moreover, a proportion of our stroke cohort with persistent severe disability (mRS = 5) at discharge and/or unable to give informed consent were excluded. Although these 410 severely disabled patients totaled only 10.4% of all available stroke patients (with similar proportions in both SCT and SCR cohorts), the rate of dysphagia and the association with comorbidities might be underestimated. Our tissue-based definition of TIA/stroke might have skewed our population slightly towards milder stroke symptoms. Lastly, since over 99% of this cohort consists of patients of European descent, our results may not be generalizable to more ethnically diverse populations and regions.

Our study has several strengths. We provide data from two large, prospective cohorts that consecutively enrolled patients with ischemic stroke in a reference center in Western Austria and report important additional results regarding the influence of pre-existing comorbidities and the risk of developing clinically relevant swallowing impairment after stroke. Components of the CCI were prospectively evaluated using face-to-face interviews as well as digital medical records and individual comorbidities showed similar prevalences compared to other stroke cohorts [14].

Conclusions

Patients with multiple comorbidities are more likely to develop dysphagia after acute ischemic stroke. Therefore, these patients should be thoroughly examined for dysphagia at an early stage.

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge the efforts of the entire language and speech therapy team of the Department of Neurology, Innsbruck, for the great support. The STROKE-CARD Study Group Markus Anliker, Gregor Broessner, Julia Ferrari, Martin Furtner, Andrea Griesmacher, Ton Hanel, Viktoria Hasibeder, Katharina Kaltseis, Gerhard Klingenschmid, Theresa Köhler, Stefan Krebs, Florian Krismer, Clemens Lang, Christoph Mueller, Wolfgang Nachbauer, Anna Neuner, Anja Perfler, Thomas Porpaczy, Gerhard Rumpold, Christoph Schmidauer, Theresa Schneider, Lisa Seekircher, Uwe Siebert, Christine Span, Martin Sojer, Lydia Thiemann, Lena Tschiderer, Marlies Wichtl, Karin Willeit.

The STROKE-CARD Study Group

Markus Anliker, Gregor Broessner, Julia Ferrari, Martin Furtner, Andrea Griesmacher, Ton Hanel, Viktoria Hasibeder, Katharina Kaltseis, Gerhard Klingenschmid, Theresa Köhler, Stefan Krebs, Florian Krismer, Clemens Lang, Christoph Mueller, Wolfgang Nachbauer, Anna Neuner, Anja Perfler, Thomas Porpaczy, Gerhard Rumpold, Christoph Schmidauer, Theresa Schneider, Lisa Seekircher, Uwe Siebert, Christine Span, Martin Sojer, Lydia Thiemann, Lena Tschiderer, Marlies Wichtl, Karin Willeit.

Abbreviations

- ABI

Ancle brachial index

- AIDS

Acquired immunodeficiency syndrome

- BMI

Body mass index

- CCI

Charlson comorbidity index

- mRS

Modified rankin scale

- NIHSS

National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale

- SCT

Stroke card trial

- SCR

Stroke card registry

Authors’ contributions

AK: Writing – original draft; investigation; conceptualization; methodology; data curation; formal analysis; visualization; writing – review and editing. VB: Conceptualization; data curation; investigation; writing – review and editing. KM: Writing – review and editing; data curation; conceptualization. LB: Conceptualization; data curation; investigation; writing – review and editing. BD: Conceptualization; data curation; investigation; writing – review and editing. SiK: Writing – review and editing; data curation; conceptualization. MTE: Writing – review and editing; data curation; conceptualization. TT: Writing – review and editing; data curation; supervision. LMS: Data curation; supervision; writing – review and editing. RP: Writing – review and editing; supervision; data curation. JG: Writing – review and editing; data curation; conceptualization. SS: Data curation; supervision; writing – review and editing. SR: Supervision; writing – review and editing. GS: Data curation; supervision; writing – review and editing. JW: Writing – review and editing; supervision. PW: Writing – review and editing; supervision. WL: Writing – review and editing; supervision. SK: Writing – review and editing; supervision; project administration. MK: Project administration; writing – review and editing; supervision; data curation; formal analysis; methodology; conceptualization; writing – original draft. CB: Writing – review and editing; data curation; supervision; formal analysis; project administration; methodology; conceptualization; writing – original draft.

Funding

Stroke CARD trial: The Medical University of Innsbruck served as the sponsor of this study and received financial support from the university hospital (Tirol Kliniken), Tyrolean Health Insurance Company (TGKK), the Tyrol Health Care Funds (TGF), and unrestricted research grants from Boehringer Ingelheim, Nstim Services, and Sanofi. The study centre in Vienna additionally received a grant from Bayer Healthcare. CB and SKi were supported by the excellence initiative VASCage (Centre for Promoting Vascular Health in the Ageing Community, project number 868624), an R&D K-Centre of the Austrian Research Promotion Agency (COMET program—Competence Centers for Excellent Technologies) funded by the Austrian Ministry for Transport, Innovation and Technology, the Austrian Ministry for Digital and Economic Affairs and the federal states Tyrol, Salzburg, and Vienna. The study sponsor and funders had no influence on the study design and clinical decisions, and no role in data analysis, interpretation, and publication.

STROKE-CARD registry: This study is supported by VASCage – Research Centre on Clinical Stroke Research. VASCage is a COMET Centre within the Competence Centers for Excellent Technologies (COMET) programme and funded by the Federal Ministry for Climate Action, Environment, Energy, Mobility, Innovation and Technology, the Federal Ministry of Labour and Economy, and the federal states of Tyrol, Salzburg and Vienna. COMET is managed by the Austrian Research Promotion Agency (Österreichische Forschungsförderungsgesellschaft). FFG Project number: 898252.

Availability of data and materials

The data collected within this study can be accessed from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Both STROKE-CARD studies (SCR and SCT) received approval from the local ethics committee of the Medical University of Innsbruck. All required patient consents were obtained, and the corresponding institutional forms were archived.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

PW reports consultancy fees from Novartis Pharmaceuticals unrelated to this manuscript. None of the other authors reported conflicts of interest relevant to this work.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Michael Knoflach, Email: michael.knoflach@i-med.ac.at.

Christian Boehme, Email: christian.boehme@i-med.ac.at.

for the STROKE-CARD study group:

Markus Anliker, Gregor Broessner, Julia Ferrari, Martin Furtner, Andrea Griesmacher, Ton Hanel, Viktoria Hasibeder, Katharina Kaltseis, Gerhard Klingenschmid, Theresa Köhler, Stefan Krebs, Florian Krismer, Clemens Lang, Christoph Mueller, Wolfgang Nachbauer, Anna Neuner, Anja Perfler, Thomas Porpaczy, Gerhard Rumpold, Christoph Schmidauer, Theresa Schneider, Lisa Seekircher, Uwe Siebert, Christine Span, Martin Sojer, Lydia Thiemann, Lena Tschiderer, Marlies Wichtl, and Karin Willeit

References

- 1.Collaborators GS. Global, regional, and national burden of stroke and its risk factors, 1990–2019: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet Neurol. 2021;20(10):795–820. 10.1016/S1474-4422(21)00252-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nikbakht H-A, Shojaie L, Niknejad N, et al. Mortality rate of acute stroke in iran: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Caspian J Neurol Sci. 2022;8(4):252–67. 10.32598/cjns.4.31.338.1. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cohen DL, Roffe C, Beavan J, et al. Post-stroke dysphagia: A review and design considerations for future trials. Int J Stroke. 2016;11(4):399–411. 10.1177/1747493016639057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yang S, Choo YJ, Chang MC. The preventive effect of dysphagia screening on pneumonia in acute stroke patients: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Healthcare (Basel) 2021;9(12), 10.3390/healthcare9121764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 5.Jones CA, Colletti CM, Ding MC. Post-stroke dysphagia: recent insights and unanswered questions. Curr Neurol Neurosci Rep. 2020;20(12):61. 10.1007/s11910-020-01081-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yang C, Pan Y. Risk factors of dysphagia in patients with ischemic stroke: A meta-analysis and systematic review. PLoS ONE. 2022;17(6):e0270096. 10.1371/journal.pone.0270096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Banda KJ, Chu H, Kang XL, et al. Prevalence of dysphagia and risk of pneumonia and mortality in acute stroke patients: a meta-analysis. BMC Geriatr. 2022;22(1):420. 10.1186/s12877-022-02960-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Willeit P, Toell T, Boehme C, et al. STROKE-CARD care to prevent cardiovascular events and improve quality of life after acute ischaemic stroke or TIA: A randomised clinical trial. EClinicalMedicine 2020;25(100476), 10.1016/j.eclinm.2020.100476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 9.Brott T, Adams HP, Olinger CP, et al. Measurements of acute cerebral infarction: a clinical examination scale. Stroke. 1989;20(7):864–70. 10.1161/01.str.20.7.864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Quinn TJ, Dawson J, Walters MR, et al. Reliability of the modified Rankin Scale: a systematic review. Stroke. 2009;40(10):3393–5. 10.1161/STROKEAHA.109.557256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, et al. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J Chronic Dis. 1987;40(5):373–83. 10.1016/0021-9681(87)90171-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jiménez Caballero PE, López Espuela F, Portilla Cuenca JC, et al. Charlson comorbidity index in ischemic stroke and intracerebral hemorrhage as predictor of mortality and functional outcome after 6 months. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis. 2013;22(7):e214–8. 10.1016/j.jstrokecerebrovasdis.2012.11.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Thygesen K, Alpert JS, Jaffe AS, et al. Fourth Universal Definition of Myocardial Infarction (2018). J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018;72(18):2231–64. 10.1016/j.jacc.2018.08.1038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Horn J, Simpson KN, Simpson AN, et al. Incidence of poststroke depression in patients with poststroke dysphagia. Am J Speech Lang Pathol. 2022;31(4):1836–44. 10.1044/2022_AJSLP-21-00346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hall RE, Porter J, Quan H, et al. Developing an adapted Charlson comorbidity index for ischemic stroke outcome studies. BMC Health Serv Res. 2019;19(1):930. 10.1186/s12913-019-4720-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fandler S, Gattringer T, Eppinger S, et al. Frequency and predictors of dysphagia in patients with recent small subcortical infarcts. Stroke. 2017;48(1):213–5. 10.1161/STROKEAHA.116.015625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Muhle P, Wirth R, Glahn J, et al. [Age-related changes in swallowing. Physiology and pathophysiology]. Nervenarzt. 2015;86(4):440–51. 10.1007/s00115-014-4183-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pantoni L. Cerebral small vessel disease: from pathogenesis and clinical characteristics to therapeutic challenges. Lancet Neurol. 2010;9(7):689–701. 10.1016/S1474-4422(10)70104-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Alkagiet S, Papagiannis A, Tziomalos K. Associations between nonalcoholic fatty liver disease and ischemic stroke. World J Hepatol. 2018;10(7):474–8. 10.4254/wjh.v10.i7.474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ochoa-Sanchez R, Rose CF. Pathogenesis of Hepatic Encephalopathy in Chronic Liver Disease. J Clin Exp Hepatol. 2018;8(3):262–71. 10.1016/j.jceh.2018.08.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.L’Écuyer S, Charbonney E, Carrier FM, et al. Implication of hypotension in the pathogenesis of cognitive impairment and brain injury in chronic liver disease. Neurochem Res. 2023. 10.1007/s11064-022-03854-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Soleimanpour H. Bilirubin: from a disease predictor to a potential therapeutic in stroke. Int J Aging. 2023;1(1):e1–e1. 10.34172/ija.2023.e1. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Martino R, Foley N, Bhogal S, et al. Dysphagia after stroke: incidence, diagnosis, and pulmonary complications. Stroke. 2005;36(12):2756–63. 10.1161/01.STR.0000190056.76543.eb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data collected within this study can be accessed from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.