Abstract

Chronic stress is associated with anxiety and cognitive impairment. Repeated social defeat (RSD) in mice induces anxiety-like behavior driven by microglia and the recruitment of inflammatory monocytes to the brain. Nonetheless, it is unclear how microglia communicate with other cells to modulate the physiological and behavioral responses to stress. Using single-cell (sc)RNAseq, we identify novel, to the best of our knowledge, stress-associated microglia in the hippocampus defined by RNA profiles of cytokine/chemokine signaling, cellular stress, and phagocytosis. Microglia depletion with a CSF1R antagonist (PLX5622) attenuates the stress-associated profile of leukocytes, endothelia, and astrocytes. Furthermore, RSD-induced social withdrawal and cognitive impairment are microglia-dependent, but social avoidance is microglia-independent. Furthermore, single-nuclei (sn)RNAseq shows robust responses to RSD in hippocampal neurons that are both microglia-dependent and independent. Notably, stress-induced CREB, oxytocin, and glutamatergic signaling in neurons are microglia-dependent. Collectively, these stress-associated microglia influence transcriptional profiles in the hippocampus related to social and cognitive deficits.

Subject terms: Neuroimmunology, Microglia

Single-cell transcriptomics reveal that RSD induces novel stress-associated microglia affects astrocyte and endothelial cell functions, as well as social and short-term spatial memory.

Introduction

Psychosocial stress is associated with increased anxiety, social withdrawal, and cognitive deficits1. In a study of chronically stressed caregivers, monocyte transcriptional profiling demonstrated increased inflammation, and this was associated with increases in self-reported indices of depressive symptoms2. In mice, repeated social defeat (RSD) induces long-term stress-sensitization of microglia3, monocytes4, and neurons5. Stress-sensitization after RSD is associated with activation of neurons, microglia and endothelia that results in the recruitment of IL-1β-producing monocytes to the brain regions of fear and threat appraisal6–8. Moreover, stress-sensitized mice exposed to subthreshold stress (acute defeat) at 24 days caused the recurrence of microglia reactivity, monocyte recruitment, and anxiety-like behavior6,9,10. Furthermore, long-term sensitization of microglia is characterized by an amplified neuroinflammatory response with exposure to a secondary stressor11. Collectively, microglia and monocytes are critical in promoting anxiety-like behavior and cognitive deficits after RSD.

Microglia, the immune cells of the brain, play a key role in the communication between the central and peripheral immune system9. In human studies, microglia reactivity, as measured by IBA1 immunoreactivity, was implicated in anxiety and depression by modulating levels of kynurenic acid and the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis, as measured in blood and cerebrospinal fluid12. In mice, RSD resulted in microglia reactivity within regions of fear and threat appraisal, including the hippocampus, with increased chemokine and cytokine (IL-1β, CCL2) production6. Moreover, microglia depletion with PLX5622 blocked stress-induced monocyte recruitment, interleukin (IL)-1β RNA expression, and anxiety-like behavior in the open field6,11. RSD also results in the recruitment of pro-inflammatory Ly6Chi monocytes to the brain vasculature6 due to increased expression of adhesion molecules (ICAM-1, VCAM-1), prostaglandin signaling genes (Ptgs2, Lrg1, Ackr1), chemokine, and IL-1 receptor (IL-1R1)8. Collectively, microglia activation after RSD has profound effects on other cell types that underlie anxiety-like behavior and cognitive deficits. The degree to which microglia influence the RNA profile of key cells (endothelia, astrocytes, leukocytes and neurons) at a single-cell level after stress is unknown.

There is also neuronal activation in specific regions associated with fear and threat appraisal after RSD (14 h and 24 days)6,11. Neuronal activation after RSD precedes the activation of microglia6. In fact, microglia respond to ATP produced by neurons resulting in monocyte recruitment7. The hippocampus is involved in anxiety-like behavior and memory formation13 and is relevant to neuronal sensitization and post-traumatic stress disorder14,15. Neuronal sensitization is characterized by increased neuronal phospho-cAMP-response element binding protein (pCREB) induction in the dentate gyrus following an acute stressor 24 days after RSD10,14. In addition, stress-sensitized mice have an enhanced contextual fear response 24 days later with an amplified pCREB response in the hippocampus16. In mice, IL-1R1 signaling in hippocampal neurons mediates social withdrawal, and cognitive deficits after RSD10,14. RSD also increases CREB signaling, glutamatergic signaling, and neurotrophic signaling in excitatory neurons of the hippocampus dependent on IL-1R1 in Vglut2+ neurons, which has a profound effect on fear memory16. While microglia are essential for anxiety-like behavior after RSD, several behavioral responses, including social avoidance of a novel aggressor6 and enhanced fear memory, are independent of microglia16. Thus, there are clear microglia-dependent and -independent influences on behavioral responses to RSD. Understanding the degree to which microglia are involved in stress-induced neuronal sensitization and behavioral deficits is important and biologically relevant.

The goal of this study was to determine the influence of RSD on the transcriptional profile of single cells in the hippocampus (microglia, astrocytes, endothelia, and neurons), in the presence or absence of microglia. Furthermore, we aimed to relate these RNA profiles to the behavioral responses induced by RSD. Here, stress induced a novel, to the best of our knowledge, stress-associated microglia profile that directly influenced the profiles of endothelia, astrocytes, and leukocytes in the hippocampus. Moreover, microglia mediated social withdrawal and cognitive deficits after RSD, which was paralleled by selective RNA profiles in excitatory neurons of the hippocampus.

Results

Single-cell RNA sequencing of the hippocampus after RSD

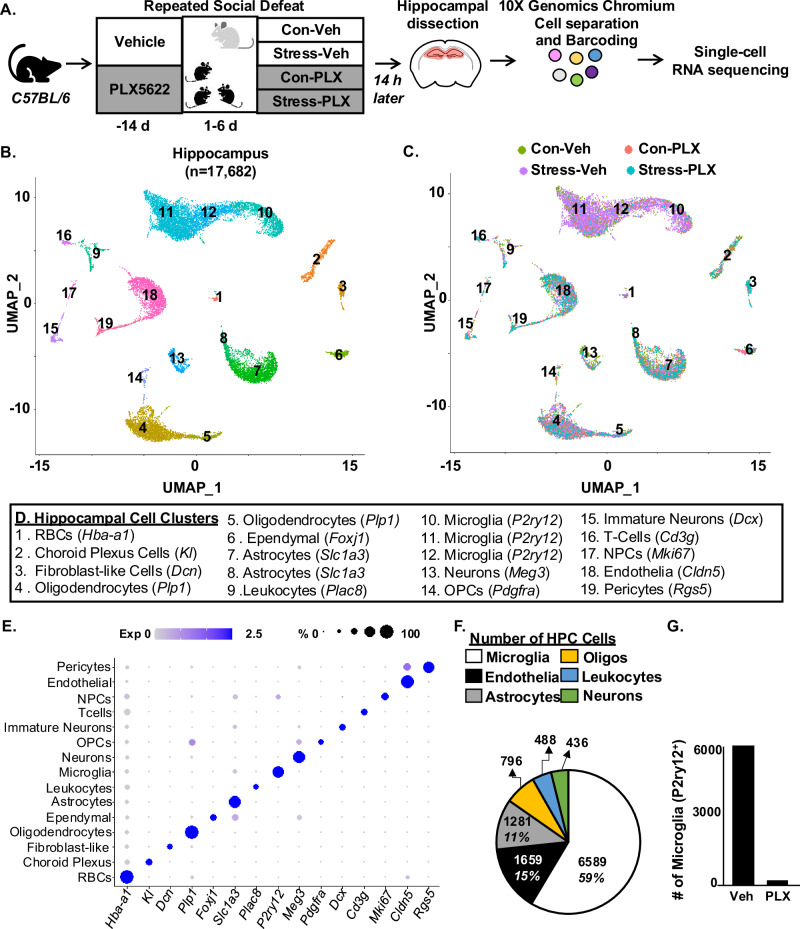

Here, single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNAseq) was used to determine the transcriptomic profile of hippocampal cells after RSD with or without microglia. In this design (Fig. 1A), vehicle (Veh) or CSF1R antagonist (PLX5622) was administered 14 days prior to RSD. Fourteen hours after RSD, brains were perfused, the hippocampus was collected, pooled, and RNA was isolated from single cells. The scRNAseq sequencing data were represented by pooled samples (3 hippocampi) and two independent experiments (n = 6).

Fig. 1. Single-cell RNA sequencing of the hippocampus after RSD.

A Male C57BL/6 mice were administered diets supplemented with Vehicle (Veh) or PLX5622 (PLX) for 14 days. Next, mice were subjected to RSD (stress) or left undisturbed (control). Mice were on diets for the duration of the experiment. Fourteen hours after RSD, mice were perfused, the hippocampus was dissected, pooled (3 mice per group), and processed for scRNAseq. Single cells were separated using a 10X Genomics Chromium controller, RNA was barcoded, and cDNA libraries were generated, sequenced, and aligned to the mouse genome. B UMAP clustering of 17,682 cells from the hippocampus resolved 19 distinct cell clusters. C The distribution of cells with UMAP clustering based on the four experimental groups (Con-Veh, Stress-Veh, Con-PLX, and Stress-PLX). D Annotation of the hippocampal cell clusters identified by cell-specific markers detected by the Conserved Marker function of Seurat. E Dot plot of relative and proportional expression of cell-specific RNA in the 19 cell clusters, including microglia (P2yr12), astrocytes (Slc1a3), endothelia (Cldn5), leukocytes (Plac8), and oligodendrocytes (Plp1). F Pie chart shows the percentage of cell-specific clusters captured and sequenced using scRNAseq. G The number of P2yr12+ microglia in PLX groups compared to vehicle groups. Clustering and differential expression were determined using Seurat in R. Pooled samples for 3 replicates and data represent two independent experiments (n = 6 mice, per group).

There were 17,682 cells sequenced from the hippocampus of Con-Veh, Con-PLX, Stress-Veh, and Stress-PLX groups, and 19 cell clusters were identified17 (Fig. 1B, C). The denotation and expression of cell-specific genes across the clusters are highlighted (Fig. 1D, E). Consistent with our previous scRNAseq data17,18, there was an enrichment of RNA captured from microglia (59%), astrocytes (11%), and endothelia (15%) compared to other cell types (Fig. 1F). Notably, scRNAseq had a low resolution of neurons19. As expected18, PLX5622 intervention reduced the number of P2ry12+ microglia (Fig. 1G). Overall, RNA was captured from single cells in the hippocampus after RSD with or without microglia depletion.

Single-cell sequencing identifies unique stress-associated microglial RNA profiles after RSD

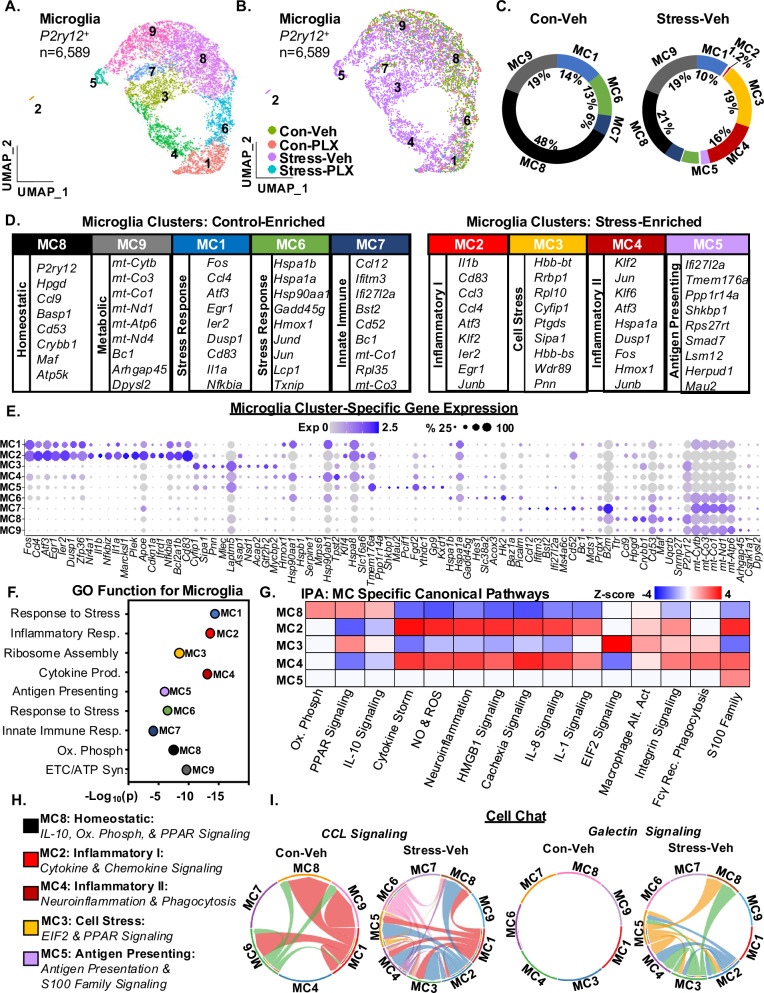

Microglia (P2ry12+) were subclustered (n = 6589), and nine distinct microglia clusters (MC1-MC9) were evident and distributed by condition (Fig. 2A, B). Notably, there were limited microglia to analyze in the PLX groups11,20. MC2 (0% to 1.2%), MC3 (0% to 19%), MC4 (0% to 16%) and MC5 (0% to 3%) were increased by stress and MC8 (48% to 21%) was decreased by stress (Fig. 2C). The top genes expressed (Log2FC) in each cluster are shown (Fig. 2D). Figure 2E shows unique genes expressed in each cluster compared to the other microglia clusters. For example, the stress-associated cluster, MC2, had high expression of Il1b, Cd83, Ccl3, Ccl4, and Nfkbia. MC4 had enriched expression of immediate early genes (IEGs) including Jun, Atf3, Fos, and Junb. The homeostatic-associated cluster, MC8, had high expression of P2ry12, Ttr, Maf, and Crybb1. In conclusion, stress promoted unique RNA profiles in microglia.

Fig. 2. Single-cell RNA sequencing identifies unique stress-associated microglial RNA profiles after RSD.

Continuing with the scRNAseq analysis in Fig. 1, A UMAP subclustering of P2y12+ microglia (6589 cells) revealed nine distinct clusters. B The distribution of microglia with UMAP clustering based on the four experimental groups (Con-Veh, Stress-Veh, Con-PLX, and Stress-PLX). C Circle charts represent the proportion of each microglial cluster in Con-Veh and Stress-Veh groups. D The top genes expressed (Log2FC, p-adj < 0.05) in each microglia cluster. E Dot plot shows relative and proportional expression of the top genes (Log2FC, p-adj < 0.05) differentially expressed across the microglial (MC) clusters (MC1-9). F GO Function pathways for differentially expressed genes (DEG) in each MC (p-adj < 0.05) G IPA of canonical pathways of differentially expressed genes (DEG) across clusters MC2-5 and MC8 (p-adj < 0.05, z-score ≥ ±1.5). H Classification of plausible function of selected microglia clusters based on IPA and GO analyses. I CellChat analyses of CCL and galectin signaling in the microglia clusters.

All cluster genes were entered into GO (Gene Ontology) analysis and IPA. Figure 2F shows GO functions for: MC1 (Response to stress), MC2 (Inflammatory Response), MC3 (Ribosome Assembly), MC4 (Cytokine Production), MC5 (Antigen Presentation), MC6 (Response to Stress), MC7 (Innate Immune Response), MC8 (Oxidative Phosphorylation) and MC9 (Electron Transport Chain/ATP Synthesis). IPA canonical pathways (z-score ≥ ±1.5) from the clusters enriched in Con-Veh (MC8) and Stress-Veh (MC2-5) are shown (Fig. 2G). Using these analyses, functional classifications were given to each enriched cluster (Fig. 2D, H). For instance, MC8, homeostatic cluster, was enriched for oxidative phosphorylation, PPAR, and IL-10 signaling. Of the stress-associated inflammatory clusters, MC2 was enriched for cytokine storm, cytokine and IL-1 signaling, MC3 was enriched for EIF2 signaling and PPAR signaling, MC4 was enriched for cytokine storm signaling and Fcγ-mediated phagocytosis, and MC5 was enriched for antigen presentation and S100 family signaling. Last, CellChat was used to assess overexpressed paracrine signaling after stress in microglia clusters (Fig. 2I). CCL and Galectin signaling were two pathways that were enhanced in Stress-Veh compared to Con-Veh. The stress-associated microglia (MC2-5) were robust contributors to both CCL and galectin signaling. Overall, there was a robust effect of stress on microglia profiles, with enhanced cytokine and chemokine expression (MC2), phagocytosis (MC4), and antigen presentation (MC5).

Microglial RNA profiles after RSD are associated with the accumulation of IL-1β+ leukocytes in the hippocampus

Differentially expressed genes (DEGs) were determined between Stress-Veh and Con-Veh in the hippocampus. Combined MC1-9 were used in this comparison. DEGs (p-adj < 0.05; Log2FC > 0.25) were used in IPA and (z-score ≥ ±1.5) canonical pathways (Fig. 3A) and upstream regulators (Fig. 3B) influenced by stress are shown. For canonical pathways, myriad microglia clusters had increased Th2 pathway, autophagy, EIF2 signaling, P2YR signaling, clatherin-mediating endocytosis, and IL-6 signaling after RSD (Fig. 3A). For upstream regulators, microglia had increased EIF4E, ZBTB16, MLXIPL, MYC, HNF4A, IL1B and IL6. Thus, along with cluster-specific profiles, there was an overall effect of stress across all microglia clusters.

Fig. 3. Microglial RNA profiles after RSD are associated with the accumulation of IL-1β+ leukocytes in the hippocampus.

Continuing with the P2y12+ microglia (6589 cells) analysis in Fig. 2, A IPA of canonical pathways influenced by stress in MC1, 6–9 and all clusters (MC1-9). B IPA of upstream regulators influenced by stress in MC1, 6–9 and all clusters (MC1-9). C Dot plots of relative and proportional expression of DEGs associated with homeostatic genes, stress-associated microglia, and disease-associated microglia (DAM) across all microglia clusters and selected clusters as a function of stress. D Continuing with the scRNAseq analysis in Fig. 1, UMAP subclustering of Plac8+ or CD3g+ leukocytes (488 total cells) resolved seven distinct clusters. E Dot plot of relative and proportional expression of leukocyte-related genes in each cluster (LC1-9). F Number of Plac8+ and CD3g+ leukocytes between vehicle and PLX5622 groups combined. G Circle charts represent the proportion of each leukocyte cluster (LC) in Con-Veh and Stress-Veh groups. H Dot plots of relative and proportional expression of Il1b in leukocyte clusters as a function of stress (top) and cluster (bottom).

Next, the expression of homeostatic (P2ry12, Sall1, Mef2c, Tgfbr1, Tmem119, Il10, and Csf1r), stress-associated (Csf1, Ptprc, Lyz2, Itgam, Cd14, Ccl2, Ccl4, Il1a, Il1b, C1qa, Nfkbia, and Tnf), and disease-associated microglia (DAMs) 1&2 genes (Cx3cr1, Spp1, Card9, Lpl, Apoe, Tyrobp, Axl, and Trem2)21,22 were assessed in the clusters as a function of either stress (top) or cluster (bottom) (Fig. 3C). Overall stress reduced homeostatic genes (P2ry12, Sall1, Mef2c, Tgfbr1, Tmem119) and increased cytokine, chemokine and complement genes (Ccl2, Ccl4, Il1a, Il1b, C1qa, Tnf) (Fig. 3C). Conserved DAMs (Cx3cr1, Spp1, Card9, Lpl), DAM1 (Tyrobp, Apoe), and DAM2 genes (Axl, Trem2)21,22 (except Apoe) were higher in controls. MC2 had enriched expression of pro-inflammatory genes (Il1b, Lyz2, Il1a, and Nfkibia). MC3-5 had increased expression of C1qa, Csf1r, Itgam, and Ptprc. Again, stress-associated microglia did not share genes associated with DAMs. Thus, there was a unique stress-associated profile of microglia, especially MC2, MC4 and MC5.

One key aspect of RSD is the microglia-mediated recruitment of IL-1β+ monocytes to the brain6,11. These IL-1β-producing monocytes interact with endothelia and enhance IL-1R1 and prostaglandin signaling to promote anxiety-like behavior6,8,23. Here, leukocytes (Plac8+ or CD3g+, n = 466 total) were examined (Fig. 3D) and seven clusters were determined based on leukocyte-specific markers17,24 (Fig. 3E). Notably, PLX groups (control and RSD) had ~60% less leukocytes compared to Veh (Fig. 3F, G) so there was an insufficient number of leukocytes with PLX5622 intervention for analysis. Stress increased the percentage of neutrophils (LC1, 14% to 23%) and MΦ/Monocytes (LC7, 0% to 10%) and decreased the percentage of border-associated macrophages (BAMs) (LC5, 41% to 21%) and monocytes (LC6, 18% to 8%). There was higher expression of Il1b in leukocytes after RSD (Fig. 3H) in neutrophils (LC1) and MΦ/Monocytes (LCs 5–7). Collectively, RSD induced unique RNA profiles of microglia in the hippocampus that were associated with the accumulation of IL-1β-expressing monocytes/macrophages and neutrophils.

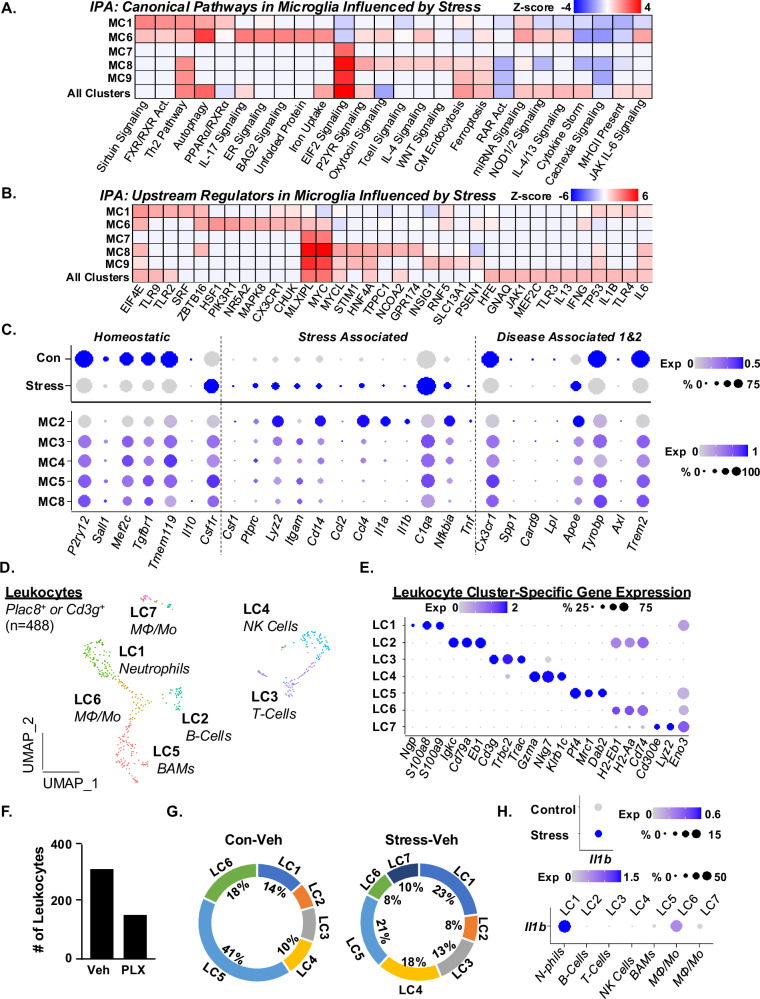

RNA profiles of astrocytes after RSD were dependent on microglia

Astrocytes are critical in maintaining the blood-brain barrier25, coordinating with microglia, and are influenced by stress26. Thus, we investigated the influence of RSD and microglia activation on the RNA profile of astrocytes. Slc1a3+ cells were subsclustered (n = 1281), and four distinct astrocyte (AC) clusters were identified (Fig. 4A–C). In a comparison of cluster distribution (Fig. 4B, C), stress increased AC3 (44% to 70%) and AC4 (11% to 25%) and decreased AC1 (36% to 3%) and AC2 (9% to 3%). These alterations in astrocyte clusters by stress were influenced by microglia depletion (Stress-Veh vs Stress-PLX). The enhancement in AC3&4 with stress was prevented by microglia depletion.

Fig. 4. RNA profiles of astrocytes after RSD were dependent on microglia.

Continuing with the scRNAseq analysis in Fig. 1, A UMAP subclustering of Slc1a3+ astrocytes (1281 cells) shows four distinct clusters of astrocytes. B Distribution of the four astrocyte clusters within the four groups: Con-Veh, Stress-Veh, Con-PLX, and Stress-PLX. C Pie charts reflect the proportion of each astrocyte cluster of the total within the four groups. D The top genes expressed (Log2FC) in each astrocyte cluster are shown (p-adj < 0.05). E GO function for each AC. F IPA of canonical pathways of differentially expressed genes between clusters AC1-4. G Percentage of stress-induced DEG in astrocytes reversed by microglia depletion. H Dot plot shows relative and proportional expression of the top genes differentially expressed between the four groups across all astrocytes. I IPA of canonical pathways of differentially expressed genes between Stress-Veh and Stress-PLX. J GO pathways of genes influenced by stress and reversed by microglia.

Furthermore, AC3 had high expression (Log2FC, p-adj < 0.05;) of neuronal support genes including Spry2, Gria2, Slitrk2 and Malat127–29 (Fig. 4D). AC4 had high expression of gliogenesis genes including Gfap, Gpm6b, Sparc, Dner, and S100a630,31. GO analysis (Fig. 4E) indicated: ATP metabolism (AC1), Oxidative phosphorylation (AC2), Synaptic organization (AC3), and Gliogenesis (AC4). IPA (Fig. 4F) showed that AC1 was enriched for mitochondria dysfunction and synaptogenesis, AC2 was enriched for electron transport and oxidative phosphorylation, AC3 was enriched for granzyme A signaling and vascular wall interaction, and AC4 was enriched for oxidative phosphorylation, IL-8 signaling, and CXCR4 signaling. Thus, there were unique astrocyte profiles induced by stress.

Next, the influence of stress and microglia depletion on astrocyte profiles was assessed. Overall, 100 DEGs were influenced by stress and 78 DEGs were reversed by microglia depletion (Fig. 4G). Representative DEGs, influenced by stress and microglia depletion, are shown (Fig. 4H). Using IPA (Fig. 4I), RAR activation, oxytocin signaling, IL-8 signaling were increased by stress and S100 family signaling and sirtuin signaling were decreased. All these pathways were dependent on microglia. Increased oxidative phosphorylation and reduced mitochondrial dysfunction pathways in astrocytes with stress were microglia-independent. GO (Fig. 4J) demonstrated that stress increased MAPK signaling, β-catenin independent WNT signaling, receptor internalization, and non-canonical NFκB signaling in a microglia-dependent manner. Collectively, microglia depletion prevented the majority of RSD-induced alterations in astrocytes.

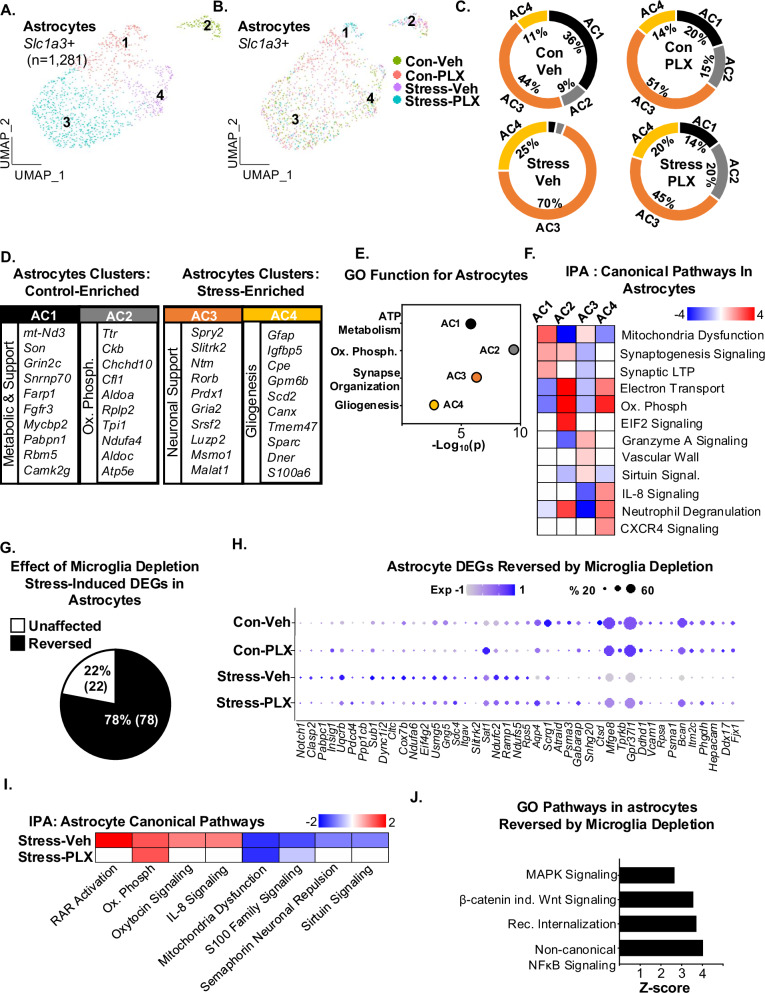

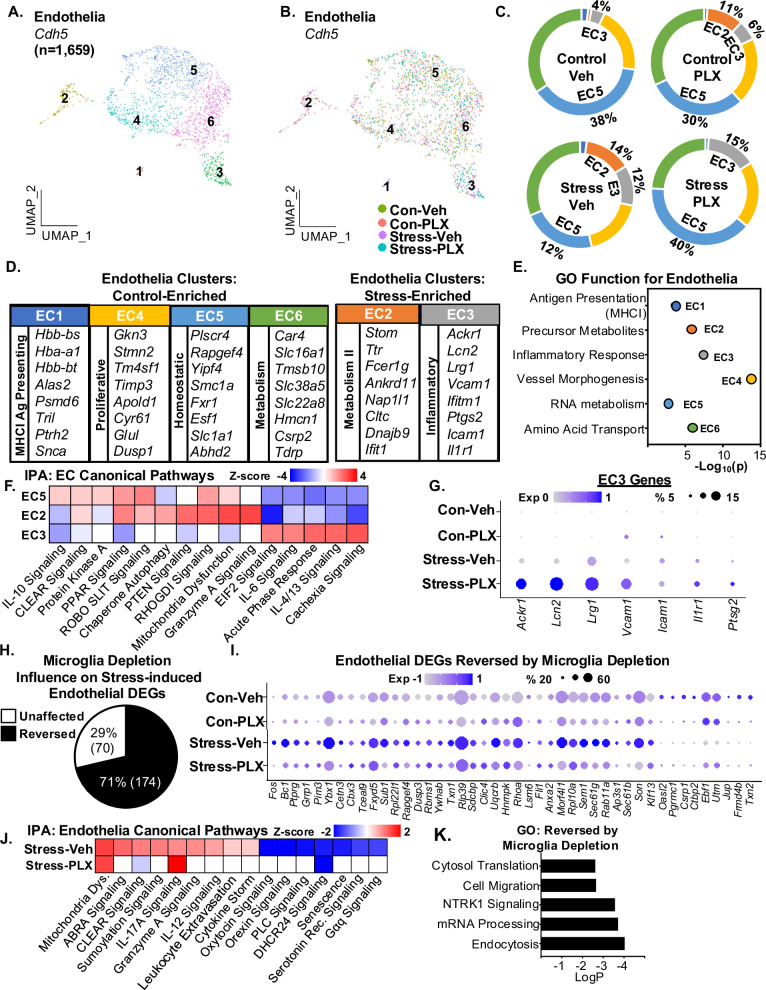

RNA profiles of endothelia after RSD were dependent on microglia

Reactive endothelia with increased adhesion molecule expression mediate leukocyte recruitment to the brain following RSD8,14,32. Moreover, IL-1R1+ endothelia are important for monocyte-to-brain communication after RSD using IL-1β6,33. Thus, we sought to determine the influence of stress and microglia activation on endothelia. Cdh5+ endothelia were subsclustered (n = 1281), and six unique clusters were identified (Fig. 5A, B). Stress increased EC2 (1% vs 14%) and EC3 (4% vs 12%) and decreased EC4 (38% vs 12%). The stress-associated changes in EC2 (14% vs 0%) and EC5 (12% vs 40%) were prevented by microglia depletion. The percentage of EC3 enhanced by stress was independent of microglia (Fig. 5C, D).

Fig. 5. RNA profiles of endothelia after RSD were dependent on microglia.

A Continuing with the scRNAseq analysis in Fig. 1, UMAP subclustering of Cdh5+ endothelia (1659 cells) shows six distinct clusters. B Distribution of the Cdh5+ endothelia clusters within the four groups: Con-Veh, Stress-Veh, Con-PLX, and Stress-PLX. C Pie charts reflect the proportion of each endothelia cluster of the total within the four groups. D The top genes expressed (Log2FC) in each endothelia cluster are shown (p-adj < 0.05). E GO function for each AC. F IPA of canonical pathways of differentially expressed genes between clusters EC 2,3, and 5. G Dot plot of selected genes from EC3 across all four groups. H Percentage of stress-induced DEGs in endothelial reversed by microglia depletion. I Dot plot shows relative and proportional expression of the top genes differentially expressed between the four groups across the endothelia clusters (EC1-6). J IPA of canonical pathways of differentially expressed genes between Stress-Veh and Stress-PLX in endothelia clusters. K GO pathways of differentially expressed genes between Stress-Veh and Stress-PLX.

Continuing with the analyses of endothelia, EC3 (stress-enriched) had increased expression of Ackr1, Lcn2, Lrg1, Vcam1, Ptgs2, Icam1, and Il1r1 and EC2 (stress-enriched) had increased expression of Stom, Ttr, Fcer1g, Ankrd11, Nap1l1, Cltc, and Ifit1. GO (Fig. 5E) indicated: protein catabolism (EC1), Precursor metabolites (EC2), Inflammatory response (EC3), vessel morphogenesis (EC4), RNA metabolism (EC5), and amino acid transport (EC6). Using IPA (Fig. 5F), EC5 had increased IL-10, PKA, and PPAR signaling. The stress-enriched EC2 had increased PTEN and granzyme A signaling. The stress-enriched EC3 had increased inflammatory pathways (IL-6, IL-4/13, cachexia). EC3 is notable due to the expression of IL-1 signaling and prostaglandin, which is consistent with previous studies8. Nonetheless, microglia depletion did not prevent the stress-induced expression of the top genes, including Lcn2, Lrg1, Vcam1 and Il1r1 (Fig. 5G).

Next, the influence of stress and microglia depletion on endothelia was assessed. Overall, there were 244 DEGs that were influenced by stress. Of these, 71% (174) were microglia dependent (Fig. 5H). Representative DEGs in endothelia, influenced by stress and microglia depletion, are shown (Fig. 5I). In addition, the DEGs in endothelia were used in IPA (Fig. 5J) and GO (Fig. 5K). For IPA (z-score ≥ ±1.5), inflammatory signaling (IL-12 and cytokine storm) and leukocyte extravasation were increased by stress, while oxytocin and PLC signaling were decreased. These pathways, and others, in the endothelia were dependent on microglia. Notably, increased mitochondria dysfunction and IL-17a signaling in endothelia with stress were microglia-independent. According to GO (Fig. 5K) stress-induced cell migration, NTRK1 signaling, and endocytosis were microglia dependent. Collectively, microglia depletion prevented the majority of the stress-induced alterations in endothelia.

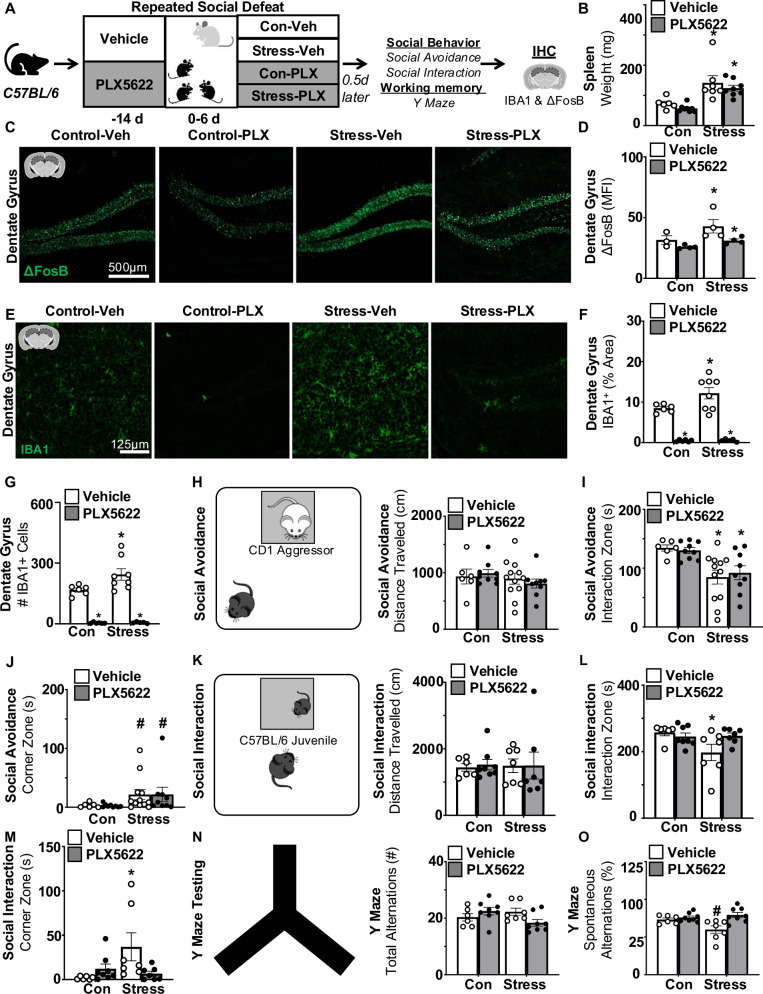

Stress-induced social withdrawal and impaired short-term spatial memory were microglia-dependent

We have reported that microglia depletion with PLX5622 blocked RSD-induced monocyte recruitment, IL-1β expression, and anxiety-like behavior in the open field6,11. In this experiment (Fig. 6A), vehicle (Veh) or CSF1R antagonist (PLX) was administered 14 days prior to RSD. Fourteen hours after RSD, social behavior, cognition, microglia reactivity (IBA1), and neuronal activation (ΔFosB), and spleen weight were assessed. Splenomegaly is a conserved response to RSD, it is used as validation and is caused by the increased presence/expansion of monocytes and erythrocytes in the spleen4. As expected, spleen weight was increased after RSD (F(1,25) = 26.13, p < 0.0001) (Fig. 6B) in both Stress-Veh and Stress-PLX groups (p < 0.05), and this increase was independent of intervention. For neuronal activation (ΔFosB), there was a main effect of stress (F(1,11) = 5.702, p = 0.0360; Fig. 6C, D) and intervention (F(1,11) = 6.529, p = 0.0267). The Stress-Veh group tended to have the highest ΔFosB compared to all other groups (p = 0.1). Collectively, microglia depletion did not attenuate splenomegaly or neuronal activation in the hippocampus (ΔFosB) after RSD.

Fig. 6. Stress-induced social withdrawal and impaired spatial memory were microglia-dependent.

A Male C57BL/6 mice were administered diets supplemented with Vehicle (Veh) or PLX5622 (PLX) for 14 d. Next, mice were subjected to RSD (stress) or left undisturbed (control). Mice were on diets for the duration of the experiment. Fourteen hours after RSD, social avoidance of a CD1 aggressor, social interaction with a novel juvenile, and working memory (Y-Maze) were assessed. After testing, samples were collected. B Spleen weight 14 h after RSD (n = 6–10). C Representative images and D mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) of ΔFosB labeling in the hippocampus (n = 4). E Representative images, F percent area and G count of IBA1+ cells in the hippocampus (n = 6–8). H Social avoidance of a CD1 aggressor mouse and total distance (cm) traveled during testing (n = 6–8). I Time spent in the interaction zone with the CD1 aggressor mouse during social avoidance testing. J Time spent in the corner zone during social avoidance testing. In a separate experiment, social interaction with a novel juvenile and Y-Maze were determined. K Social interaction with a novel C57BL/6 juvenile mouse and distance total distance (cm) traveled during testing (n = 8–10). L Time spent in the interaction zone with the C57BL/6 juvenile mouse. M Time spent in the corner zone during social interaction testing. In the same mice, working memory in the Y-Maze was also determined (n = 6–10). N Y-Maze assessment and total arm alternation during testing. O The percentage of successful spontaneous alternations during Y-Maze testing. Graphs represent the mean ± SEM, and individual data points are provided. Means with (*) are significantly different from controls (p < 0.05). Means with (#) tended to be different from controls (p = 0.06).

For microglia analyses, IBA1 percent area (F(1,11) = 10.8, p = 0.0073) and number of IBA1+ microglia (F(1,21) = 4.144, p = 0.05; Fig. 6G) were increased by stress. Post hoc confirmed that Stress-Veh had the highest percent area of IBA1 microglia and number of microglia compared to all groups (Fig. 6E–G, p < 0.05). In addition, there was a main effect of intervention, where PLX5622 mice had far fewer IBA1+ cells compared to vehicle (F(1,21) = 108.6, p < 0.001). Stress increased microglia reactivity and number in the DG, and these increases were ablated by PLX5622 intervention.

For social avoidance (aggressor), distance traveled was similar across all groups (Fig. 6H). As expected, time spent in the interaction zone with the CD1 mouse was decreased by RSD (F(1,32) = 16.6, p < 0.05; Fig. 6I). Post hoc confirmed that the Stress-Veh and Stress-PLX groups spent less time in the interaction zone compared to control groups (p < 0.05). This finding is consistent with previous results6. Time spent in the corner was increased by RSD (F(1,32) = 4.512, p < 0.05; Fig. 6J) independent of microglia. Post hoc indicates that stress groups tended to have decreased increased time in the corner zone compared to controls (p = 0.1). Overall, social avoidance of an aggressor mouse after RSD was microglia-independent.

In a separate experiment, social interaction (juvenile) and short-term spatial memory in the Y-Maze were assessed. For social interaction, the distance traveled was similar across all groups (Fig. 6K). Interaction time with the juvenile tended to be reduced by RSD (F(1,24) = 3.749, p = 0.06), and this reduction was microglia dependent (interaction, F(1,24) = 4.289, p = 0.0493; Fig. 6L). Post hoc confirmed that the Stress-Veh group had the lowest social interaction compared to all groups (p < 0.05). Time spent in the corner tended to be increased by stress (F(1,24) = 2.917, p = 0.1) and was dependent on microglia interaction (F(1,24) = 5.557, p = 0.0269; Fig. 6M). Post hoc confirmed that the Stress-Veh group spent the most time in the corner compared to all groups (p < 0.05). For the Y-Maze, total arm entries were similar across all groups (Fig. 6N). For spontaneous alternation, there was an interaction effect (F(1,25) = 6.028, p < 0.05; Fig. 6O). Post hoc analysis indicates that Stress-Veh mice tended to have the fewest spontaneous alternations compared to all groups (p = 0.06). The stress effect here is consistent with our previous studies14. Overall, stress-associated social withdrawal and short-term spatial memory deficits were microglia-dependent.

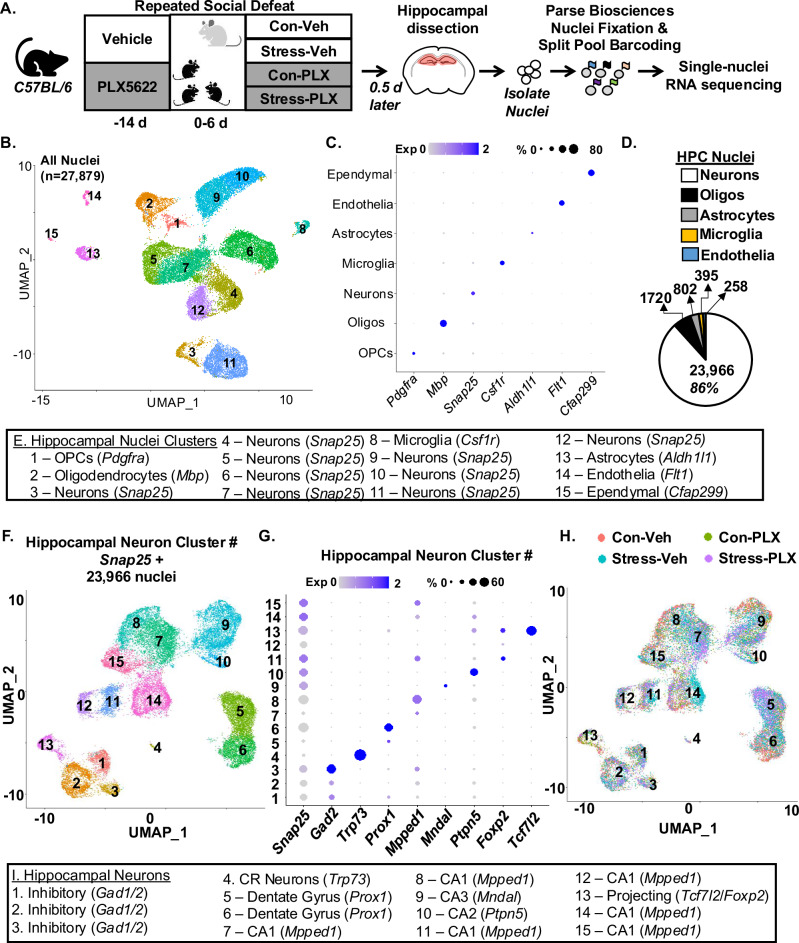

Single-nuclei RNA sequencing in the hippocampus after RSD

The RNA profiles of microglia, astrocytes, endothelia, and leukocytes in the hippocampus were robustly influenced by RSD and microglia. There was enrichment of RNA captured from microglia, astrocytes, and endothelia by scRNAseq compared to neurons. Moreover, our previous data indicate some RSD-induced behavioral deficits are microglia dependent (e.g., anxiety and spatial memory)6,34 and others are microglia independent (e.g., social avoidance of the aggressor and conditioned fear memory)16,35. This is consistent with the data shown here. Thus, single-nuclei RNA sequencing (snRNAseq) was used to analyze neuronal RNA profiles in the hippocampus with and without microglia. Here, PLX5622 administration was used 14 days prior to RSD. Fourteen hours after RSD, hippocampal nuclei were isolated, fixed, and barcoded; 27,879 cells were sequenced from the hippocampi (Fig. 7A). There were 15 unique cell clusters identified and annotated (Fig. 7B, C, E) using cell-specific genes36,37. As expected37,38, the majority of RNA sequenced was derived from neurons (86%). Snap25+ neurons were subclustered (Fig. 7F, n = 23,955), and 15 unique clusters were identified (Fig. 7G, J) using previously reported neuronal markers36,38,39. Figure 7H shows the distribution of clusters based on treatments. Consistent with previous snRNAseq data37, there was an overall enrichment of RNA captured and sequenced from neurons.

Fig. 7. Single-nuclei RNA sequencing in the hippocampus after RSD.

A Male C57BL/6 mice were administered diets supplemented with Vehicle (Veh) or PLX5622 (PLX) for 14 d. Next, mice were subjected to RSD (stress) or left undisturbed (control). Mice were on diets for the duration of the experiment. Fourteen hours after RSD, the hippocampus was dissected and pooled (3 mice per group). Nuclei were collected, fixed, barcoded and nucleus RNA profiles were determined by snRNAseq. B UMAP clustering from a total of 27,897 nuclei identified 15 unique cell clusters. C Dot plot shows the expression of cell-specific markers in the 15 cell clusters. D Pie chart showing the distribution of nuclei identities across all sequenced nuclei. E Annotation of each cell cluster based on markers detected within the ConservedMarkers function. F UMAP clustering from a total of 23,966 Snap25+ neuronal nuclei identified 15 unique neuronal clusters. G Expression of neuronal-specific markers found within the ConservedMarkers function: neuron (Snap25), inhibitory (Gad2), Cajal-Retzius (Trp73), dentate gyrus (Prox1), CA1 (Mpped1), CA3 (Mndal), CA2 (Ptpn5), projecting (Foxp2 and Tcfl2). H Neuronal cluster distribution for each group: Con-Veh, Stress-Veh, Con-PLX, and Stress-PLX. I Annotation of neuronal subtype based on the ConservedMarkers function. Clustering and differential expression were determined using uniform manifold approximation and projections (UMAP) clustering command in Seurat. Pooled samples for 3 replicates.

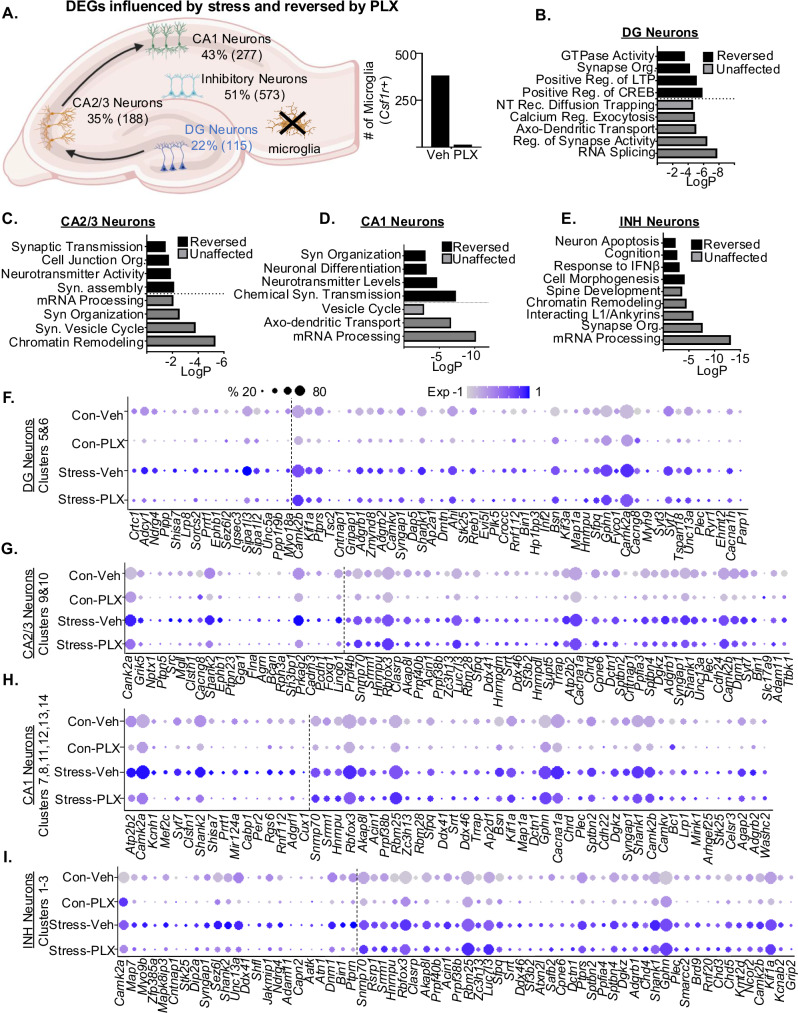

Both microglia-dependent and -independent profiles of hippocampal neurons were evident after RSD

DEGs (p-adj < 0.05) were used to assess the influence of stress and microglia depletion on major subtypes of neurons (DG, CA2/3, CA1, and INH). Figure 8A shows that 22% of DEGs in the DG neurons, 35% of DEGs in CA2/3, 43% of DEGs in the CA1, and 51% of DEGs in inhibitory neurons were influenced by stress and were prevented by microglia depletion. In addition, there was a reduced number of microglia in the PLX5622 groups compared to vehicle (Fig. 8A). These DEGs were entered into GO to determine biological functions in neuronal-specific clusters that were prevented (black bar) and unaffected (gray bar) by microglia depletion (Fig. 8B–E). In DG neurons (Fig. 8B), the stress-associated increase in synapse organization and regulation of LTP and CREB were microglia-dependent, and the enhanced calcium regulation of exocytosis and axo-dendritic transport were unaffected. The corresponding DEGs associated with the GO biological function in DG neurons are shown (Fig. 8F). In CA2/3 neurons (Fig. 8C), the stress-associated increase in neurotransmitter activity and synaptic transmission were microglia dependent and increased chromatin remodeling and mRNA processing were microglia independent. The corresponding DEGs associated with the GO pathways in CA2/3 neurons are shown (Fig. 8G). In CA1 neurons (Fig. 8H), stress-associated increase in neurotransmitter levels and chemical synaptic transmission were microglia dependent and the increase in axo-dendritic transport and mRNA processing were unaffected. The corresponding DEGs associated with the GO pathways in CA1 neurons are shown (Fig. 8H). In INH neurons (Fig. 8D), stress-associated increases in IFNβ and cell morphogenesis were microglia-dependent, and increases in synapse organization and mRNA processing were unaffected. The corresponding DEGs associated with the GO pathways in INH neurons are shown (Fig. 8I). Collectively, RSD influenced DEGs and pathways in all major subtypes of hippocampal neurons, and a subset of neuronal responses to stress (~38%) were microglia-dependent.

Fig. 8. Both microglia-dependent and independent profiles of hippocampal neurons were evident after stress.

Continuing with the snRNAseq of Snap25+ neurons, differentially expressed genes (DEG) were assessed. A Hippocampal diagram with the number of (DEG) influenced by RSD and dependent on microglia in DG, CA2/3, CA1 and INH neurons. Number of microglia nuclei in snRNAseq data set for the control and PLX5622 groups are shown. B Gene Ontology (GO) function analysis for stress-induced DEGs (p-adj < 0.05) in DG neurons reversed or unaffected by microglia depletion (PLX). C GO function analysis for stress-induced DEGs (p-adj < 0.05) in CA2/3 neurons reversed or unaffected by microglia depletion (PLX). D GO function for stress-induced DEGs (p-adj < 0.05) in CA1 neurons reversed or unaffected by microglia depletion (PLX). E GO function analysis for stress-induced DEGs (p-adj < 0.05) in INH neurons reversed or unaffected by microglia depletion (PLX). Dot plot shows relative and proportional expression of stress-induced DEGs (p-adj < 0.05) that were reversed or unaffected by microglia depletion (PLX) in F DG neurons, G CA2/3 neurons, H CA1 neurons, and I INH neurons.

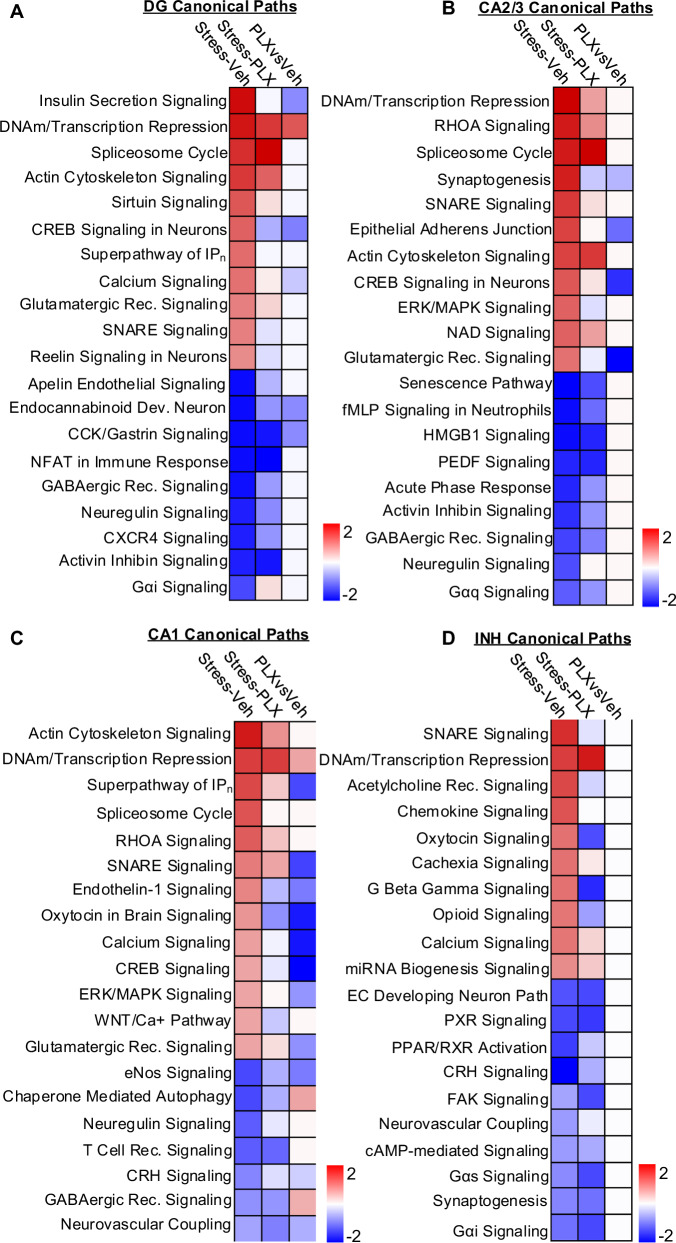

Canonical pathways enriched in hippocampal neurons after RSD were both microglia-dependent and independent

DEGs (p-adj < 0.05) were used in IPA to determine canonical pathways influenced by stress and microglia depletion. In DG neurons (Fig. 9A), stress increased DNA methylation transcription repression and spliceosome cycle. These increases were independent of microglia. Stress also increased CREB signaling and reelin signaling in DG neurons that were dependent on microglia. In CA2/3 neurons (Fig. 9B), RSD increased DNA methylation transcription repression and Spliceosome cycle, and these increases were unaffected by microglia depletion. Also, in CA2/3 neurons, stress increased in CREB signaling and Glutamatergic receptor signaling, and this increase was microglia-dependent. In CA1 neurons, stress increased DNA methylation transcription repression and RHOA signaling, and this increase was unaffected by microglia depletion. Stress also increased calcium signaling and endothelin-1 signaling in CA1 neurons that were microglia-dependent (Fig. 9C). In INH neurons (Fig. 9D), stress increased DNA methylation transcription repression and spliceosome cycle, which was unaffected by microglia depletion. Stress also increased chemokine and oxytocin signaling in INH neurons that were microglia-dependent (Fig. 9D). Collectively, myriad activation pathways in hippocampal neurons were influenced by RSD, and these influences were both microglia-dependent and independent.

Fig. 9. Canonical pathways enriched in hippocampal neurons after stress were both microglia-dependent and independent.

Continuing of the snRNAseq of Snap25+ neurons, DEGs (p-adj < 0.05) were used in IPA to determine significant (z-score ≥ ±1.5) canonical pathways in DG, CA2/3, CA1 and INH neurons with Stress-Veh, Stress-PLX, and Stress-PLX vs Stress-Veh comparisons. A Heatmap of significant (z-score ≥ ±1.5) canonical pathways for Stress-Veh, Stress-PLX, and Stress-PLX vs Stress-Veh in hippocampal dentate gyrus (Prox1) neurons. B Heatmap of significant (z-score ≥ ±1.5) canonical pathways for Stress-Veh, Stress-PLX, and Stress-PLX vs Stress-Veh in hippocampal CA2/3 (Ptpn5 or Mndal), neurons. C Heatmap of significant (z-score ≥ ±1.5) canonical pathways for Stress-Veh, Stress-PLX, and Stress-PLX vs Stress-Veh in hippocampal CA1 (Mpped1) neurons. D Heatmap of significant (z-score ≥ ±1.5) canonical pathways for Stress-Veh, Stress-PLX, and Stress-PLX vs Stress-Veh in hippocampal inhibitory (Gad1/2) neurons.

Discussion

The purpose of this study was to determine the influence of RSD on the transcriptional profile of cells in the hippocampus. Moreover, we aimed to relate these RNA profiles to the microglia-dependent and independent behavioral responses induced by RSD. Single-cell (scRNAseq) and single-nuclei (snRNAseq) RNA sequencing approaches were used with microglial depletion (PLX5622) to determine the influence of stress and microglia on the transcriptional profiles within the hippocampus. Consistent with previous work6, PLX5622 ablated microglia. The mice were on vehicle or PLX5622 for the duration of the experiments (21 days). New data shows that stress-associated microglia (SAM) was evident in the hippocampus with distinct chemokine, phagocytosis, or antigen presentation profiles. In addition, there was a notable influence of stress-activated microglia on leukocytes, endothelia, and astrocytes. The majority of DEGs, canonical pathways, and biological functions elicited in these cells by RSD were microglia-dependent. When comparing these RNA signatures to behavior, stress-induced social withdrawal and cognitive impairment were microglia-dependent, but social avoidance was microglia-independent. In hippocampal neurons, snRNAseq showed robust responses to stress, which were both microglia-dependent and independent. Furthermore, stress-induced CREB, calcium, and glutamatergic receptor signaling in excitatory neurons were microglia-dependent. Thus, the influence of stress-activated microglia on neurons of the hippocampus was linked to social withdrawal and spatial memory deficits.

One novel finding, to the best of our knowledge, of this study was the identification and profiling of SAMs in the hippocampus. Microglia are critical in mediating monocyte recruitment to the brain, neuroinflammation, and anxiety-like behavior after RSD7,11. Here, we extend these findings and identify four unique microglia clusters enriched in the hippocampus after RSD compared to controls. These microglia clusters were associated with inflammation: cytokine and chemokine signaling (MC2), ER stress (MC3), phagocytosis (M4), and antigen presentation (MC5). MC2 were enriched for Il1b, Ccl3, Ccl4, and IPA showed enriched pathways of cytokine storm signaling, neuroinflammation, IL-1 signaling, and integrin signaling. The increased IL-1β RNA profile of microglia is consistent with the profile detected by previous FAC sorting/nanoString RNA analysis and RNAScope analysis 14 h after RSD6,7,16,40. This, however, is the first time unique RNA profiles of microglia clusters have been reported with stress. Notably, aside from increased APOE expression, these stress-associated microglia (SAM) did not have increased expression of the disease-associated microglia (DAM) 1&2 genes21,22 (Spp1, Card9, Lpl, Tyrobp, Axl, and Trem2). Using CellChat, SAMs enhanced paracrine pathways in microglia following RSD for CCL3/4-CCR5 signaling. Another report showed that CCR5 was increased in microglia in the prefrontal cortex (PFC) after chronic stress and was associated with microglia activation, phagocytosis, and social deficits41. Thus, these stress-associated microglia express a pro-inflammatory/chemoattraction profile that was transcriptionally different than DAMs.

Related to the above profiles of SAMs, RSD increased the proportion of Il1b+ leukocytes (monocytes and neutrophils) in the hippocampus. This was dependent on microglia. These data are consistent with our previous data showing that microglia facilitate the recruitment of IL-1β-producing monocytes/macrophages to the brain6,9. These monocytes produce active IL-1β6 that interacts with IL-1R1 on endothelia8,33 to enhance prostaglandin signaling. There was no difference in the number of monocytes between stress and control groups. Nonetheless, single-cell isolation and sequencing do not provide accurate information on absolute cell number, especially compared to FAC sorting approaches6,42. Notably, four leukocyte clusters had increased expression of IL-1β RNA, including neutrophils and mature (Lyz2+) macrophages. Our previous analyses with flow cytometry, transgenic reports, and histology indicate more monocyte/macrophages accumulate in the brain after RSD6,9. In fact, other studies of stress show increased mature neutrophil mobilization in the blood, spleen, bone marrow, and hypothalamus43,44. Thus, it is plausible that neutrophils are also recruited to the brain after RSD and contribute to the increased IL-1β signaling. One caveat is that PLX5622 affects long-lived tissue-derived macrophages45. Notably, it has been reported that PLX5622 effects on circulating myeloid cells46. Nonetheless, we and others have not seen PLX5622 affect myeloid cells in circulation6,47. Overall, the chemokine signature of MC2 is associated with increased IL-1β expression of distinct myeloid populations in the hippocampus.

Another relevant finding was that stress induced microglia profiles associated with ER stress (MC3), phagocytosis (MC4), and antigen presentation (MC5). For instance, MC3 had high expression of Eukaryotic Initiation Factor 2 (EIF2) signaling. EIF2 facilitates oxidative stress and endoplasmic reticular stress. This is consistent with another study of RSD showing that microglia-mediated ER stress induced phosphorylated eIF2α in the hippocampus48. Moreover, in a model of neurodegeneration, this pathway was enhanced by ER stress and resulted in increased neuroinflammation and memory impairment49. In addition, MC4 was associated with Fcy receptor-mediated phagocytosis. Work with chronic unpredictable stress (CUS) shows that microglia phagocytosis mediated neuronal restructuring50,51. Furthermore, enhanced microglia phagocytosis of dendritic spines and axon segments in the CA1 after CUS facilitated depressive-like anhedonia52. CUS also induced microglial P2Y12-mediated phagocytosis of dendritic elements in the PFC associated with depressive-like behavior and cognitive deficits53. Here, CellChat showed increased galectin-9 (Gal-9-CD45) signaling in stress-associated microglia. Gal-9 signaling promotes a pro-inflammatory and phagocytic profile in microglia following a brain hemorrhage54 or with neurodegeneration55. Last, MC5 had increased S100b family signaling. This signaling pathway is a “danger signal” to downstream RAGE and TLR4-mediated neuroinflammation56. CUS also induces microglia-derived S100a8 and S100a9, facilitating NFκB and IL-1 signaling and depressive-like behavior57. Furthermore, S100a9 inhibition prevents depressive-like behavior and neuroinflammation57. Collectively, stress-associated microglia had RNA profiles consistent with ER stress, phagocytosis of dendrites, and S100b signaling.

RSD increased inflammatory pathways (Th2, IL-17, IL-4/13, JAK IL-6), phagocytosis (autophagy, unfolded protein response, clatherin-mediated endocytosis), and hormone signaling (estrogen receptor and oxytocin signaling) in all MCs. RSD also increased upstream regulators associated with inflammation (TLR9, TLR2, CHUK, IL1B, IL6, and TLR4) across all MCs. We and others have reported on these pathways in hippocampi and microglia acutely (14 h after RSD) and chronically (24 days after RSD)11,14,58. Several reports on stress in rodents show increased IL-17, IL-1, and IL-6-related signaling in microglia3,59. One caveat is that MC1 and MC6 may be a confound of enzymatic digestion in the cell isolation protocol, based on the enhanced expression of immediate early genes (Atf3, Junb, and Egr1) and heat shock proteins (Hsp90ab1 and Hsp90aa1)60. Collectively, stress enhanced several inflammatory, phagocytic, and hormone-related pathways across all microglia clusters.

Another notable finding was that RSD promoted novel, to the best of our knowledge, transcriptional profiles in hippocampal astrocytes and endothelia that were dependent on microglia. Over seventy percent of the DEGs influenced by stress in astrocytes and endothelia were prevented with microglia depletion. For astrocytes, the two unique stress-induced profiles were associated with neuronal support (AC3) and gliogensis (AC4). AC3 had increased pathways/functions associated with synapse organization, vascular wall interaction, neutrophil degranulation, and mitochondrial dysfunction. AC4 had pathways increased pathways/functions associated with oxidative phosphorylation, IL-8 signaling, and CXCR4 signaling. RSD notably increased oxytocin signaling, retinoic acid receptor (RAR) activation, and IL-8 signaling dependent on microglia. This is relevant because previous studies indicate that astrocyte-to-neuron oxytocin signaling modifies social behavior after stress61–63. MAPK and non-canonical NFκB signaling were also activated by stress and were microglia-dependent. Notably, the transcriptional profile induced by stress paralleled the reported A2 neuroprotective profile of astrocytes64. For endothelia, the two primary stress-induced unique profiles were associated with metabolism (EC2) and inflammatory response (EC3). Consistent with the metabolic profile, EC2 had increased pathways/functions associated with PTEN, RHOGDI, and Granzyme A signaling. EC3 had increased pathways/functions associated with profiles of vascular remodeling, leukocyte extravasation, and IL-1R1/prostaglandin signaling8. The top DEGs in EC3 were Lcn2, Icam, Ptgs2, Lrg1, and Il1r1. These same DEGs were increased in endothelia after RSD as detected using endothelial Ribotag (Tie2-Cre) mice8. Notably, these genes were unaffected by microglia depletion. Nonetheless, IPA of all ECs showed that stress enhanced cytokine storm signaling and leukocyte extravasation dependent on microglia. These data are consistent with previous studies with RSD6,8. The majority of the stress-induced alterations to astrocytes and endothelia were dependent on microglia.

Another component here was the effect of RSD on the RNA profiles of hippocampal neurons. These stress-induced influences on hippocampal neurons were both microglia-dependent and independent. Less than half of DEGs in hippocampal neurons were prevented by microglia depletion. For instance, DNA methylation transcription repression and spliceosome cycle were influenced by stress independent of microglia. Several pathways in excitatory neurons were increased by stress and prevented by microglia depletion. In DG neurons, stress increased CREB, glutamatergic, calcium, SNARE, and reelin signaling. Microglia depletion prevented only 22% of the DEGs, but the identified pathways were all dependent on microglia. In addition, microglia depletion reversed DEGs in the DG associated with synapse organization, CREB, and LTP. There are several examples of stress influencing LTP in the hippocampus65,66. In CA1 and CA2/3 neurons, stress increased excitatory, glutamatergic, and CREB signaling. Microglia depletion prevented 40% of the stress-induced DEGs in CA1 neurons and several stress-induced pathways related to neuronal potentiation (i.e., synapse organization, neuronal differentiation, neurotransmitter levels, and synapse transmission). Thus, RSD enhanced neuronal activity in the CA1 and CA2/3 that was dependent on microglia. In INH neurons, microglia depletion prevented 51% of the stress-induced DEGs and prevented several stress-induced pathways involving interferon-β and neuron apoptosis. In IPA, stress-enhanced chemokine, opioid, and acetylcholine signaling were also dependent on microglia. Notably, subtypes of inhibitory neurons could not be delineated here, thus further studies are needed to assess specific INH subtypes affected by stress and microglia depletion. Overall, key pathways induced in neurons after stress were dependent on microglia.

When comparing these hippocampal RNA signatures to behavior, RSD-induced social withdrawal (juvenile) and short-term spatial memory (Y-Maze) were dependent on microglia, but social avoidance (aggressor) and increased spleen weight were microglia-independent. Moreover, previous studies indicate that Y-Maze spatial memory was dependent on CA132,67,68. Following stress, lack of attenuation to spatial information and alterations to AMPA expression were associated with short-term spatial memory deficits Y-Maze deficits69,70. Thus, the effect of microglia depletion on CA1 neurons aligns with the Y-Maze data above. While deficits in short-term spatial memory (Y-Maze) were prevented with microglia depletion, long-term spatial memory (i.e., Morris water maze) and reference memory tasks (i.e., novel object localization) following RSD and microglia depletion were not assessed in this study. In a recent study, stress-enhanced fear memory was independent of myeloid cells but dependent on neuronal-IL-1R1 signaling16. In snRNAseq, there was a robust effect of RSD on hippocampal neurons, but less than half of the DEGs were reversed by microglia depletion. Conversely, 80% of the RSD effects on the neuronal transcriptome were reversed by neuronal-IL-1R1−/−16. Thus, the microglia versus neuronal-IL-1R1-dependent reversals highlight pathways that represent neuronal-dependent or microglia-dependent communication with RSD. One limitation of this study was that only male mice were used. Nonetheless, we and others have used genetically modified male aggressors for studies involving females with Cre-conditional ‘designer receptors exclusively activated by designer drugs (DREADD)71–73. In our previous studies of RSD with female mice, the data paralleled males with splenomegaly, increased plasma IL-6, and myelopoiesis, microglia reactivity, monocyte accumulation, and anxiety-like behavior71. RSD has face validity and elicits similar neuroimmune and behavioral responses in both males and females. Further investigation of single-cell microglia profiles in females after RSD is warranted. Additionally, recent advancements in single-cell resolution of the morphology of microglia74 represent a future direction that may allow for further characterization of the stress-associated microglia. Overall, stress elicited a robust neuronal response in the hippocampus that was partially mediated by microglia. These stress-associated microglia influenced transcriptional profiles in the hippocampus that are closely linked to social withdrawal and spatial memory deficits.

In conclusion, these data augment the understanding of how SAMs communicate (paracrine signaling) with endothelia, astrocytes, leukocytes, and neurons after stress. Microglia mediate a majority of transcriptional changes in endothelia, astrocytes, and leukocytes after RSD. Stress also induced myriad changes to the neuronal transcriptome in the hippocampus, both dependent and independent of microglia. Last, the microglia-dependent influence on hippocampal neurons after stress coincided with the reversal of social withdrawal of a novel juvenile and short-term spatial memory deficits in the Y-Maze. Overall, we provide single-cell-specific influences of stress-induced microglia reactivity on the hippocampus, specifically with new insight into the neuronal pathways that influence social behavior and spatial memory.

Materials and methods

Mice

Male C57BL/6 (6–8 weeks) and CD-1 aggressors were purchased from Charles River Laboratories. Only male mice were used in this study. All behavior and biological measures were obtained 14 h after RSD. All procedures were in accordance with NIH Guidelines and the OSU Institutional Laboratory Animal Care and Use Committee.

PLX5622 administration

PLX5622 was provided by Plexxikon Inc. (Berkley, CA) and formulated in AIN-76A rodent chow by Research Diets (1200 mg/kg). Standard AIN-76A diet was given as vehicle. Mice were provided ad libitum access to PLX5622 or vehicle diet for 14 days to deplete microglia prior to RSD. This dose and time for depletion was previously validated to deplete ~96% of microglia6.” The mice were on vehicle or PLX5622 for the duration of the experiments (21 days).

Repeated social defeat (RSD)

Mice were subjected to RSD as previously described8. In brief, a male CD-1 aggressor mouse was placed into the home cage of experimental mice (3 mice/cage) for 2 h (between 16:00 and 18:00) per night for six consecutive nights. Mice were randomly assigned to cages of three for each experiment. During the 2 h, submissive behaviors (e.g., upright posture, fleeing, crouching) were observed to ensure experimental mice showed signs of defeat. A new CD-1 aggressor was introduced to the cage if no attack occurred within 3–5 min or if an experimental mouse defeated the CD-1 aggressor. To avoid habituation, different aggressors were used on consecutive nights. Resilience is uncommon in this version of repeated social defeat compared to other models of social defeat (paired fighting)75. The health of the experimental mice was monitored carefully throughout the experiments. Experimental mice that were significantly wounded, injured or moribund were removed from the study. Similar to previous studies, less than 5% of mice met the early removal criteria16. Specifically, five experimental mice in the current study met the exclusion criteria and were removed prior to the behavioral analysis for social interaction. Control mice were left undisturbed in their home cages.

Social behaviors

Social interaction and social avoidance were assessed14. Separate cohorts of mice were used for social interaction with the juvenile (n = 6–8) and social avoidance of the aggressor (n = 8–10). For social interaction, a novel juvenile C57BL/6 mouse was placed into an 18 × 8 × 8 cm metal wire enclosure, placed on one side of the open field apparatus (40 × 40 × 25 cm; Plexiglas box). For social avoidance, a novel CD-1 aggressor mouse was placed into the metal wire enclosure within the open field apparatus. In both assessments of social behavior, distance traveled (cm), activity and time spent in areas proximal to the cage or corners were recorded for 5 min using an automated digital beam break system attached to a computer containing an open field software (Omnitech Electronics).

Y-Maze

Working memory behavior was determined using the Y-Maze as previously described14. In brief, mice were placed into the center of a 7 × 40 × 12 cm Y-Maze (San Diego Instruments, Inc). Behavior was recorded (5 min), and entries into each arm were counted. A spontaneous alternation was defined as entering all three arms before revisiting a previously entered arm. The spontaneous alternations by each mouse were determined and shown as a percentage of total 3-entry sets. Experimenters were blinded to the groups during behavioral scoring.

ΔFosB and IBA1 detection

Immunohistochemical analyses were completed as described7,8. In brief, after CO2 asphyxiation, mice were transcardially perfused with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) followed by 4% formaldehyde. Brains were postfixed for 24 h, frozen (−80 °C), and sectioned (30 μm). Sections were stored in cryoprotectant at −20 °C. Hippocampal sections (Bregma: −1.70 mm to −1.94 mm) were washed with PBS, blocked (5% normal donkey serum, 5% bovine serum albumin, 0.1% Trition-X100), and incubated with primary antibodies: anti-IBA1 (1:1000; Wako Chemicals, cat# 019–19741) or anti-ΔFosB (1:1000; Abcam, cat# ab184938) overnight. Separate sections were used for each label and 2–3 sections were used per sample. Next, sections were washed and incubated with fluorochrome-conjugated secondary antibodies (1:500; AlexaFluor 488; Thermo Fisher Scientific). Labeled sections were washed with PBS, mounted on slides with DAPI, and imaged using an EVOS M7000 system at 10× or 20× magnification. Percent area (IBA1) of the dentate gyrus indicative of reactive, dystrophic, and phagocytizing microglia76 was used. Based on the cumulative nature ΔFosB77, mean fluorescent intensity (ΔFosB) of the granule cell layer of the dentate gyrus was assessed. ImageJ images were pseudo-colored green in the relevant figures. Experimenters were blinded to the treatments during image capture and analysis.

Hippocampal dissociation

Mice mice underwent CO2 asphyxiation and were perfused with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). The hippocampus was dissected and dissociated using the Miltenyi Adult Mouse Brain Dissociation Kit per the manufacturer’s instructions with minor modifications. Tissue was immediately placed into Enzyme P solution (37 °C), Enzyme A solution was added, and tissue was dissociated in C-tubes using a gentleMACS dissociator. Density centrifugation was used to remove myelin debris, remaining red blood cells were lysed, and cell viability and concentration were determined using a hemocytometer. Hippocampi from three mice per group were pooled into each sample. This experiment was performed in two replicates, with six mice per group total, and approximately 3000–5000 cells were recovered from each sample.

10X genomics single-cell RNA sequencing

Single-cell suspension was loaded onto a 10X chip and run on a Chromium Controller to generate gel-bead emulsions. Protocols for UMI barcoding, cDNA amplification, and library construction followed the Chromium Next GEM Single Cell 3’ GEM, Library & Gel Bead Kit v3.1 kit protocol (10X Genomics; 1000121). Library quality was determined by Agilent High Sensitivity DNA BioAnalyzer chip and was sequenced using an Illumina HiSeq. Sequencing reads were aligned to the mm10 mouse genome, and count matrices were generated using CellRanger (10X Genomics). Low-quality cells (doublets, low counts, high counts) were filtered using the Seurat package in R78. Cells expressing >20% mitochondria RNA were excluded from analysis. Clustering was performed using Uniform Manifold Approximation and Projection (UMAP) and cell identification was performed with established markers18,79: microglia (P2ry12), astrocytes (Gja1), endothelia (Cldn5), ependymal (Foxj1), oligodendrocytes (Plp1), red blood cells (Hba-a1), oligodendrocyte progenitor cells (Pdgfra), choroid plexus cells (Kl), fibroblast-like cells (Dcn), Leukocytes (Plac8), neurons (Meg3), immature neurons (Dcx), neural precursor cells (Mki67), T-cells (CD3g), and pericytes (Rgs5). Cluster-specific expression and differential expression between experimental groups were determined using Model-based Analysis of Single-cell Transcriptomics (MAST; p-adj < 0.05; FC ≥ |0.25|).

Nuclei isolation

Mice underwent CO2 asphyxiation and hippocampi (n = 3) were extracted and pooled. Pooled samples were homogenized using dounce homogenizers and a homogenization buffer (1.5 M NIM1 Buffer with 250 mM sucrose, 25 mM KCl, 5 mM MgCl2, 10 mM Tris Buffer pH 8, 1 μM DTT, 0.4 U/μL Enzymatics RNAase-Inhibitor (#Y9240L), 0.2 U/μL Superase-Inhibitor (Thermo Fisher Scientific, #AM2694), and 0.1% Triton X-100). Hippocampi homogenates were filtered (40 μM strainer) and clarified. Resulting homogenates were resuspended in a PBS buffer with RNase Inhibitors (0.05 U/μL of Enzymatics RNAase-Inhibitor and Superase-Inhibitor) and re-pelleted. To remove myelin debris, homogenates were incubated with Myelin Removal Beads II (Miltenyi Biotec, #130-096-731) for 15 min at 4 °C. Homogenates were washed (50% PBS and 50% PBS+1% BSA) and re-pelleted. Supernatant was removed and samples were resuspended in wash buffer. One LS column (Miltenyi Biotec, # 130-042-401) per sample was used to filter the samples, followed by pelleting and resuspending in wash buffer. Nuclei were counted with AO/PI (Logos Biosystems, #F23001) on a Luna-FL Cell Counter and fixed with a Nuclei Fixation Kit (Parse Biosciences, #SB1003) per the manufacturer’s instructions, followed by freezing at −80 °C in a Mr. Frosty (Thermo Fisher Scientific, #5100-001)37.

Single-nuclei barcoding and sub-library generation

The Parse Biosciences Whole Transcription Kit was used to barcode and generate eight separate sub-libraries with 12,500 nuclei each according to the manufacturer’s instructions. DNA concentration was measured by Qubit 4 Fluorometer and a Qubit dsDNA HS Assay Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific, #Q32851). A Bioanalyzer 2100 with a High Sensitivity DNA Assay chip was used to control the quality of sub-libraries before samples were sequenced at a depth of 40,000 reads per nuclei using a NovaSeq S4 at the Advanced Genomics Core at the University of Michigan Advanced Genomics Core37.

SnRNAseq data processing

Each fastq.gz file was downloaded and aligned to the Genome Reference Consortium Mouse Reference 39 (mm39) using the Parse Biosciences pipeline. Matrices were filtered in RStudio using Seurat (v4.1.1)80. Nuclei showing >20% mitochondrial RNA were filtered out prior to clustering. After UMAP clustering, cell identification was performed with established markers36,81,82: endothelia (Flt1), astrocytes (Aldh1l1), ependymal cells (Cfap299), oligodendrocytes (Mbp), Microglia (Csf1r), oligodendrocyte progenitor cells (Pdgfra), and neurons (Snap25), CA1 neurons (Mpped1), CA2/3 (Mndal, Ptpn5), Dentate gyrus neurons (Prox1), inhibitory neurons (Gad2,), Cajal-Retzius cells (Trp73), and projecting neurons (Tcf7l2, Foxp2). Differential gene expression from p-adj values was performed using the FindMarkers feature of Seurat with MAST83. Pathway, regulator, and gene ontology (GO) analysis was performed with Ingenuity Pathway Analysis (IPA; Qiagen)84 and Metascape85. Z-scores greater than ±1.5 were used.

Statistical analysis and rigor

Data are expressed as treatment mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM). To determine significant main effects and interactions between main factors in multiple-group comparisons, data were analyzed using two-way ANOVA in GraphPad Prism (v10.0.2). In the event of a main effect of experimental treatment, differences between group-means were evaluated by Tukey’s HSD test. Post hoc analyses are graphically presented in figures. The threshold for statistical significance was set at p < 0.05. Trends for differences between groups were defined as p ≤ 0.10. Experimenters were blinded to treatment groups during behavior, scoring, and image analysis. Grubbs outlier test was used to determine outliers (Q = 1%), which were removed from all analyses.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Supplementary information

Description of Additional Supplementary File

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by NIMH R01-MH-119670 and NIMH R01-MH-116670 (to J.P.G. and J.F.S.).

Author contributions

E.J.G., D.J.D., J.F.S., and J.P.G. contributed to the study conception and design. E.J.G. and D.J.D. contributed to data collection. E.J.G., D.J.G., and J.P.G. contributed to the analysis and interpretation of results. E.J.G., D.J.D., J.F.S., and J.P.G. contributed to manuscript preparation. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Biology thanks Marie-Eve Tremblay and the other anonymous reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Primary handling editors: Christoph Anacker and Benjamin Bessieres.

Data availability

Raw values (Supplementary Data 1) and code (Supplementary Data 2) are included in Supplementary Data. The sequencing data discussed have been deposited in NCBI’s Gene Expression Omnibus and are accessible through GEO Series accession GSE253687 (snRNAseq) and GSE275205 (scRNAseq).

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

John F. Sheridan, Email: John.Sheridan@osumc.edu

Jonathan P. Godbout, Email: jonathan.godbout@osumc.edu

Supplementary information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s42003-024-06898-9.

References

- 1.Ressler, K. J. Amygdala activity, fear, and anxiety: modulation by stress. Biol. Psychiatry67, 1117–1119 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Miller, G. E. et al. Greater inflammatory activity and blunted glucocorticoid signaling in monocytes of chronically stressed caregivers. Brain Behav. Immun.41, 191–199 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Weber, M. D. et al. The influence of microglial elimination and repopulation on stress sensitization induced by repeated social defeat. Biol. Psychiatry85, 667–678 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 4.McKim, D. B. et al. Social stress mobilizes hematopoietic stem cells to establish persistent splenic myelopoiesis. Cell Rep.25, 2552–2562.e3 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 5.Biltz, R. G., Sawicki, C. M., Sheridan, J. F. & Godbout, J. P. The neuroimmunology of social-stress-induced sensitization. Nat. Immunol.23, 1527–1535 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.McKim, D. B. et al. Microglial recruitment of IL-1β-producing monocytes to brain endothelium causes stress-induced anxiety. Mol. Psychiatry23, 1421–1431 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Biltz, R. G. et al. Antagonism of the brain P2X7 ion channel attenuates repeated social defeat induced microglia reactivity, monocyte recruitment and anxiety-like behavior in male mice. Brain Behav. Immun.115, 356–373 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 8.Yin, W. et al. Unique brain endothelial profiles activated by social stress promote cell adhesion, prostaglandin E2 signaling, hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal axis modulation, and anxiety. Neuropsychopharmacology47, 2271–2282 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wohleb, E. S. et al. Re-establishment of anxiety in stress-sensitized mice is caused by monocyte trafficking from the spleen to the brain. Biol. Psychiatry75, 970–981 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.DiSabato, D. J. et al. IL-1 receptor-1 on Vglut2+ neurons in the hippocampus is critical for neuronal and behavioral sensitization after repeated social stress. Brain Behav. Immun. Health26, 100547 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Weber, M. D. et al. The influence of microglial elimination and repopulation on stress sensitization induced by repeated social defeat. Biol. Psychiatry85, 667–678 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Baharikhoob, P. & Kolla, N. J. Microglial dysregulation and suicidality: a stress-diathesis perspective. Front. Psychiatry11, 781 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Blanchard, R. J., McKittrick, C. R. & Blanchard, D. C. Animal models of social stress: effects on behavior and brain neurochemical systems. Physiol. Behav.73, 261–271 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.DiSabato, D. J. et al. Interleukin-1 receptor on hippocampal neurons drives social withdrawal and cognitive deficits after chronic social stress. Mol. Psychiatry26, 4770–4782 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 15.McEwen, B. S., Nasca, C. & Gray, J. D. Stress effects on neuronal structure: hippocampus, amygdala, and prefrontal cortex. Neuropsychopharmacology41, 3–23 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Goodman, E. J. et al. Enhanced fear memory after social defeat in mice is dependent on interleukin-1 receptor signaling in glutamatergic neurons. Mol. Psychiatry10.1038/s41380-024-02456-1 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 17.O’Neil, S. M., Hans, E. E., Jiang, S., Wangler, L. M. & Godbout, J. P. Astrocyte immunosenescence and deficits in interleukin 10 signaling in the aged brain disrupt the regulation of microglia following innate immune activation. Glia70, 913–934 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Witcher, K. G. et al. Traumatic brain injury causes chronic cortical inflammation and neuronal dysfunction mediated by microglia. J. Neurosci.41, 1597–1616 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kulkarni, A., Anderson, A. G., Merullo, D. P. & Konopka, G. Beyond bulk: a review of single cell transcriptomics methodologies and applications. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol.58, 129–136 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bray, C. E. et al. Chronic cortical inflammation, cognitive impairment, and immune reactivity associated with diffuse brain injury are ameliorated by forced turnover of microglia. J. Neurosci.42, 4215–4228 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pettas, S. et al. Profiling microglia through single-cell RNA sequencing over the course of development, aging, and disease. Cells11, 2383 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schwabe, T., Srinivasan, K. & Rhinn, H. Shifting paradigms: the central role of microglia in Alzheimer’s disease. Neurobiol. Dis.143, 104962 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wohleb, E. S., Powell, N. D., Godbout, J. P. & Sheridan, J. F. Stress-induced recruitment of bone marrow-derived monocytes to the brain promotes anxiety-like behavior. J. Neurosci.33, 13820–13833 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Van Hove, H. et al. A single-cell atlas of mouse brain macrophages reveals unique transcriptional identities shaped by ontogeny and tissue environment. Nat. Neurosci.22, 1021–1035 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Heithoff, B. P. et al. Astrocytes are necessary for blood–brain barrier maintenance in the adult mouse brain. Glia69, 436–472 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Luarte, A. et al. Astrocyte-derived extracellular vesicles in stress-associated mood disorders. Does the immune system get astrocytic? Pharmacol. Res.194, 106833 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gross, I. et al. Sprouty2 inhibits BDNF-induced signaling and modulates neuronal differentiation and survival. Cell Death Differ.14, 1802–1812 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Batiuk, M. Y. et al. Identification of region-specific astrocyte subtypes at single cell resolution. Nat. Commun.11, 1220 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhang, Y. et al. Overexpression of long noncoding RNA Malat1 ameliorates traumatic brain injury induced brain edema by inhibiting AQP4 and the NF‐κB/IL‐6 pathway. J. Cell. Biochem.120, 17584–17592 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Steiner, B. et al. Differential regulation of gliogenesis in the context of adult hippocampal neurogenesis in mice. Glia46, 41–52 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Liu, J., Wu, X. & Lu, Q. Molecular divergence of mammalian astrocyte progenitor cells at early gliogenesis. Development149, dev199985 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Menard, C. et al. Social stress induces neurovascular pathology promoting depression. Nat. Neurosci.20, 1752–1760 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wohleb, E. S. et al. Knockdown of interleukin-1 receptor type-1 on endothelial cells attenuated stress-induced neuroinflammation and prevented anxiety-like behavior. J. Neurosci.34, 2583–2591 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.McKim, D. B. et al. Neuroinflammatory dynamics underlie memory impairments after repeated social defeat. J. Neurosci.36, 2590–2604 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ramirez, K., Niraula, A. & Sheridan, J. F. GABAergic modulation with classical benzodiazepines prevent stress-induced neuro-immune dysregulation and behavioral alterations. Brain Behav. Immun.51, 154–168 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rosenberg, A. B. et al. Single-cell profiling of the developing mouse brain and spinal cord with split-pool barcoding. Science360, 176–182 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Packer, J. M. et al. Impaired cortical neuronal homeostasis and cognition after diffuse traumatic brain injury are dependent on microglia and type I interferon responses. Glia72, 300–321 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 38.Del-Aguila, J. L. et al. A single-nuclei RNA sequencing study of Mendelian and sporadic AD in the human brain. Alzheimer’s Res. Ther.11, 1–16 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zhong, S. et al. Single-nucleus RNA sequencing reveals transcriptional changes of hippocampal neurons in APP23 mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem.84, 919–926 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Niraula, A., Witcher, K. G., Sheridan, J. F. & Godbout, J. P. Interleukin-6 induced by social stress promotes a unique transcriptional signature in the monocytes that facilitate anxiety. Biol. Psychiatry85, 679–689 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 41.Lin, H.-Y. et al. Chemokine receptor 5 signaling in PFC mediates stress susceptibility in female mice. Preprint at bioRxiv10.1101/2023.08.18.553789 (2023).

- 42.Baron, C. S. et al. Cell type purification by single-cell transcriptome-trained sorting. Cell179, 527–542.e519 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ishikawa, Y. et al. Repeated social defeat stress induces neutrophil mobilization in mice: maintenance after cessation of stress and strain‐dependent difference in response. Br. J. Pharmacol.178, 827–844 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Pflieger, F. J. et al. The role of neutrophil granulocytes in immune-to-brain communication. Temperature5, 296–307 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Vichaya, E. G. et al. Microglia depletion fails to abrogate inflammation-induced sickness in mice and rats. J. Neuroinflammation17, 1–14 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bosch, A. J. et al. CSF1R inhibition with PLX5622 affects multiple immune cell compartments and induces tissue-specific metabolic effects in lean mice. Diabetologia66, 2292–2306 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Green, K. N. & Hume, D. A. On the utility of CSF1R inhibitors. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA118, e2019695118 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Tang, J., Yu, W., Chen, S., Gao, Z. & Xiao, B. Microglia polarization and endoplasmic reticulum stress in chronic social defeat stress induced depression mouse. Neurochem. Res.43, 985–994 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Bond, S., Lopez-Lloreda, C., Gannon, P. J., Akay-Espinoza, C. & Jordan-Sciutto, K. L. The integrated stress response and phosphorylated eukaryotic initiation factor 2α in neurodegeneration. J. Neuropathol. Exp. Neurol.79, 123–143 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Song, X. et al. Fcγ receptor I-and III-mediated macrophage inflammatory protein 1α induction in primary human and murine microglia. Infect. Immun.70, 5177–5184 (2002). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Cao, S., Standaert, D. G. & Harms, A. S. The gamma chain subunit of Fc receptors is required for alpha-synuclein-induced pro-inflammatory signaling in microglia. J. Neuroinflammation9, 1–11 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Milior, G. et al. Fractalkine receptor deficiency impairs microglial and neuronal responsiveness to chronic stress. Brain Behav. Immun.55, 114–125 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Bollinger, J. L. et al. Microglial P2Y12 mediates chronic stress-induced synapse loss in the prefrontal cortex and associated behavioral consequences. Neuropsychopharmacology48, 1347–1357 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Liang, T. et al. Galectin-9 promotes neuronal restoration via binding TLR-4 in a rat intracerebral hemorrhage model. Neuromolecular Med.23, 267–284 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Liu, J., Huang, S. & Lu, F. Galectin-3 and Galectin-9 may differently regulate the expressions of microglial M1/M2 markers and T helper 1/Th2 cytokines in the brains of genetically susceptible C57BL/6 and resistant BALB/c mice following peroral infection with Toxoplasma gondii. Front. Immunol.9, 1648 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Xia, C., Braunstein, Z., Toomey, A. C., Zhong, J. & Rao, X. S100 proteins as an important regulator of macrophage inflammation. Front. Immunol.8, 1908 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Gong, H. et al. Hippocampal Mrp8/14 signaling plays a critical role in the manifestation of depressive-like behaviors in mice. J. Neuroinflammation15, 1–13 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]