Abstract

Background

The Polish educational system for nurses has undergone a substantial transformation over the past two decades, with the introduction of a mandatory university education that encompasses humanization in medicine. Consequently, nurses who had been licensed to practice before the implementation of the reform returned to universities to pursue master’s degrees alongside their younger colleagues who had only recently obtained bachelor’s degrees. This distinctive learning environment, in which nurses of varying ages and years of practice study together, offers an opportunity to gain insight into their perspectives on the educational process. Accordingly, the present study aims to examine the opinions of Polish postgraduate nursing students at one university regarding medical humanization courses, focusing on the extent to which these opinions are shaped by age, years of service, and specialty of nursing care.

Methods

From February to June 2023, an anonymous survey was conducted on the university’s online platform, involving 89 out of 169 participants in the master’s degree nursing program. The newly designed questionnaire comprised 15 primary questions and 11 metric questions.

Results

The study population consisted of registered nurses with a mean age of 35 years (ranging from 22 to 54 years). The majority of participants were women (97.8%). The analysis revealed that older students (Spearman’s rho 0.480, p < 0.001) and those with more years of professional experience (Spearman’s rho 0.377, p < 0.001) perceived humanizing classes as a vital component of nurse training and work. Younger and less experienced students did not share this perspective. Specialization status was also identified as a differentiating factor (Chi² = 10.830, p < 0.05). However, other characteristics, including the number of positions held during the survey, the type of position, the primary employer, and the nature of work (shift or non-shift), did not exhibit statistically significant differentiation among participants.

Conclusions

This study found age- and work-experience-related differences in nursing students’ opinions toward courses teaching humanization in health care. The results suggest that changing the teaching format and involving older and more experienced students in sharing experiences with younger and less experienced students could potentially improve the implementation of learned skills in clinical practice.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12909-024-06079-6.

Keywords: Curriculum, Nursing, Humanities, Quality of education, Medical humanities

Introduction

Nursing practice standards, competency frameworks, and curricula integrate humanistic values such as compassion, empathy, and caring, along with other related concepts [1]. Humanism has accompanied nursing since its inception, historically associated with “charity, compassion, sacrifice and mercy” [2]. Despite the values passed down from generation to generation, the increasing role of science, technology, and the professionalization of nursing have caused it to change [3]. For many years, the humanistic content of nursing curricula was neglected because nursing was seen as a “caring profession.” Such content seemed unnecessary [5] since those who chose this profession already had certain predispositions. Létourneau et al. [1] argue that nowadays, nurses cannot be “just nice”, as the media portrays them. Studies also suggest that nurses may dehumanize patients [4, 5], which can have negative consequences. However, it is also a way for them to cope with a very stressful job [5]. Conversely, research indicates that implementing humanization in nursing education benefits the quality of nursing care. One such study employed Watson’s Theory of Human Caring to assess the influence of humanizing nursing education on nurses and nursing students [6]. The authors concluded that the participants developed or strengthened several essential skills, including active listening and improved teamwork, contributing to an enhanced quality of nursing care in the hemodialysis units. Another study indicated that humanization courses offered to nurses caring for hypertensive patients may contribute to lowering patients’ blood pressure and improving their quality of life [7]. Additionally, a recently described humanizing approach that employed visual arts in pediatric wards was found to be an effective intervention for reducing parental distress. Furthermore, nursing staff perceived the approach as beneficial, as evidenced by the affective quality attributed to place [8]. Finally, a systematic review that focused on humanized care from the perspectives of nurses and hospitalized patients has confirmed the necessity of humanized nursing care, particularly in critical care [9]. This highlights the importance of humanization education, as this approach is advantageous for both patients and nurses. Thus, it seems reasonable to suggest that nursing education, which encompasses the humanistic dimensions, may be linked to superior healthcare outcomes. Hence, nurses should receive sufficient education in medicine’s humanization principles.

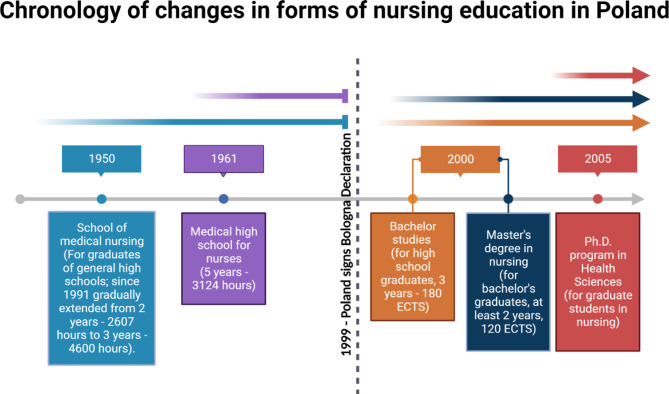

In 2022, there were 310,000 professionally active nurses in Poland [10], with 5.1 nurses per 1,000 inhabitants. According to a report by the Main Chamber of Nurses and Midwives (Polish: NIPiP), in April 2022, 36% of Polish nurses were aged 51–60, and 19.5% of active nurses were aged 61–70, with 4% of those over 70 still working. According to projections, 65% of currently employed nurses will reach retirement age by 2030 [11], which creates a crisis in the nursing workforce, a problem observed for years and not unique to Poland [12]. One of the reasons is the restrictions on admission to nursing studies [12]. Currently, nursing education in Poland is regulated by the European Union and Polish legislation [13–16]. The most significant changes in nursing education occurred after the socio-economic transformation in 1989 (Fig. 1). In 1999, Poland adopted the “WHO European Strategy for Nursing and Midwifery Education,” which set the direction for changes in education and signed the Bologna Declaration [17]. Consequently, three nursing programs were established: a Bachelor of Nursing, a Master of Nursing, and a doctoral program [18].

Fig. 1.

Schematic representation of the types of nursing education offered in Poland after World War II. Created with BioRender.com. Partly based on information published in [18]

As in other countries (e.g., the UK, Australia, and Canada), introducing nursing into higher education has increased the number of more mature people with previous work experience and internships entering these programs [19]. The number of Polish nurses with secondary education has been steadily decreasing for several years, and the number of nurses with a bachelor’s or master’s degree has been increasing (NIPIP, 2023). Due to this exceptional situation in Polish nursing education, there is currently a unique population of nursing students that includes very young students with limited work experience and mature students with extensive work experience. All of them have taken courses related to medical humanities during their education, e.g., psychology, sociology, pedagogy, law, public health, philosophy, and ethics of the nursing profession [18].

In Poland, issues of health care humanization generally refer to professional ethics and have been addressed in nursing education since 1911 [18]. However, the content and implementation of ethics issues in nursing education have usually been based on traditional views and consisted mainly of describing a perfect nurse, a model that has unfortunately rarely been achieved [20]. In recent decades, the Polish higher education system has introduced humanization courses in most medical schools [21]. The curriculum for these courses and medical students’ opinions on teaching humanization have recently been analyzed. This has revealed significant discrepancies among medical schools and conflicting medical student perspectives on the efficacy of such courses and their pedagogical and assessment approaches [22, 23]. However, there is a paucity of information regarding nursing students’ perceptions of the humanization of medicine, and this is not only the case in Poland. This includes whether they find the humanization courses beneficial, whether they consider investing time in learning humanization to be worthwhile and essential for better nursing practice, and whether they believe that the humanization of medicine should be a priority in nursing education. The transitional phase in Polish nursing education permits the collective attendance of nursing programs by students from disparate age groups with varying nursing experience. Therefore, we surveyed this distinctive cohort of nursing students at one university to ascertain their opinions on the necessity of learning and the professional usefulness of humanization classes. The objective of our study is exploratory, intending to gain insight into the current situation at a Polish university to enhance the quality of medical humanization classes. To accomplish this goal, the study was not designed with specific hypotheses; rather, it was guided by the research question of whether nurses differ in their approach to humanization issues based on sociodemographic characteristics.

Materials and methods

The study was designed as an observational-analytical online survey (CAWI—Computer-Assisted Web Interview). The authors (J.H.-A, M.L.-P., A.J.S.) developed the questionnaire comprising 15 primary questions (10 closed-ended and five open-ended) and 11 metric questions. The four domains addressed in the questionnaire were as follows: (1) opinions about humanistic courses, (2) types of humanistic courses attended, (3) the nursing ethical code of practice, and (4) suggestions for improving humanistic courses. The responses were measured on a Likert scale, ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree).

The survey was administered to students enrolled in the Master of Science in Nursing program during the 2022/2023 academic year. All students attended the 15-hour lectures on the humanization of medicine. The content of the lectures (as presented in the curriculum) includes issues related to the subjectivity and dignity of human beings in health and illness, communication, and understanding between health professionals and patients as an integral part of the art of medical care.

From 02/01/2023 to 06/30/2023, nursing students received an invitation with a link to https://elearning.cm.uz.zgora.pl/. Students were informed that participation in the survey was anonymous and voluntary. A relatively high response rate of 53% was achieved. There were 169 nursing students enrolled in the program at the time of the survey, and 89 completed the questionnaire.

The questionnaire took an average of 15 min to complete. Answers to the questions were not mandatory; respondents could skip a question if they did not wish to answer it. A translation of the questionnaire is provided in the Supplementary Information. The original questionnaire and database are available on request from the corresponding author. The study was approved by the Ethics Committee; approval number RCM-CM-KBUZ.031.16.2023.

The survey defined courses of interest as “Humanization of Medicine,” “Interpersonal Communication in Medicine,” or “Other” (sociology, psychology, education, philosophy, and ethics of the nursing profession). “Humanization of Medicine” and “Interpersonal Communication in Medicine” were part of the respondents’ master’s curriculum, while others were compulsory during their undergraduate studies.

Results were analyzed using IBM SPSS Statistics 28.0 software. Despite a reasonably high response rate, the final number of questionnaires analyzed was not very high due to the small target group. Therefore, the statistical analysis focused mainly on frequency analysis and non-parametric statistical tests (Pearson’s chi-square, rho Spearman, Kruskal-Wallis and Dunn’s multiple comparisons test).

Results

Master’s level nursing students were predominantly female, making up 97.8% of the study population. A significant characteristic of the sample is that 39.3% of the nurses were over 40 years of age, of which 13.5% were over 50. The mean age was 35.1 years (SD 10.9; min. 22, max. 54). As many as 29.2% of the respondents had more than 20 years of professional experience; 51.1% had a nursing specialty certification. Other sociodemographic characteristics that differentiate the sample are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Socio-demographic characteristics of the survey participants

| Profile characteristics | n | % |

|---|---|---|

| sex | ||

| female | 87 | 97.8% |

| male | 2 | 2.2% |

| Total | 89 | 100.0% |

| age | ||

| 18–29 | 39 | 43.8% |

| 30–39 | 15 | 16.9% |

| 40–49 | 23 | 25.8% |

| 50+ | 12 | 13.5% |

| Total | 89 | 100.0% |

| professional experience | ||

| Up to 5 years | 41 | 46.1% |

| 5–10 years | 13 | 14.6% |

| 11–20 years | 9 | 10.1% |

| 20 years and more | 26 | 29.2% |

| Total | 89 | 100% |

| specialization | ||

| Yes | 45 | 51.1% |

| No | 43 | 48.9% |

| Total | 88* | 100.0% |

| number of jobs at the time of the survey | ||

| One | 55 | 61.8% |

| Two | 26 | 29.2% |

| Three or more | 8 | 9.0% |

| Total | 89 | 100.0% |

| main employer | ||

| Hospital | 76 | 85.4% |

| Health center | 5 | 5.6% |

| Other | 8 | 9.0% |

| Total | 89 | 100.0% |

| position | ||

| Nursing leadership | 6 | 6.9% |

| Unit nurse | 81 | 93.1% |

| Total | 87* | 100.0% |

| type of work (shift or not) | ||

| Shift work | 68 | 76.4% |

| Daytime | 21 | 23.6% |

| Total | 89 | 100.0% |

* N is not equal to 89, as there were missing answers

The results of the survey indicated that nursing students’ opinions leaned in a positive direction about the fact that humanization in medicine is a valuable addition to the curriculum (question A) and that the content taught is relevant to their profession (question B) (Table 2). Moreover, the participants expressed satisfaction with the time allocated for the lessons (question C) and indicated that the content was not superfluous (question D). Finally, they were cautiously positive about including humanization courses in their continuing education (question E).

Table 2.

Descriptive analysis of the survey results

| Question text | N | Mean | SD | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| A. | Do you think that humanization/medical humanities classes are necessary for training as a nurse? | 88 | 3.58 | 1.229 |

| B. | Is the content of humanization courses useful for nursing practice? | 89 | 3.64 | 1.264 |

| C. | Do you think that the time allotted for implementing the Humanization Classes is sufficient? | 89 | 4.16 | 0.976 |

| D. | Do you think there was unnecessary content in the humanization classes? | 89 | 2.84 | 1.214 |

| E. | In your opinion, should medical humanities content be systematically recalled in the form of on-the-job training? | 89 | 3.43 | 1.096 |

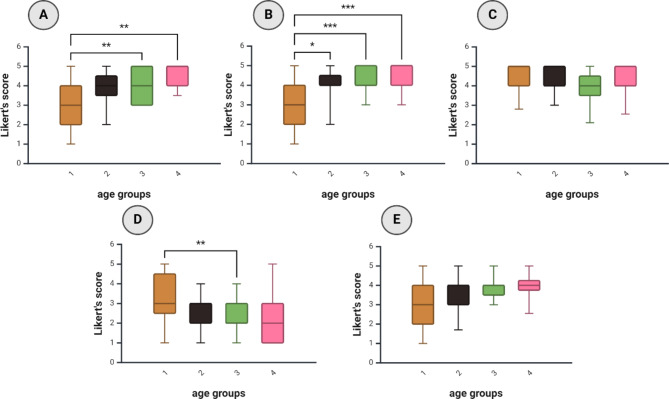

However, differences were observed between the older and younger students when the analysis was divided into age groups (18–29, 30–39, 40–49, and 50+). The older students demonstrated a greater appreciation for the humanities courses and their content than the younger students (Fig. 2A)., exhibiting less criticism regarding the superfluous content of the classes (Fig. 2B). There was a consensus among all students that the time allotted to the course was sufficient (Fig. 2C). Younger students were more likely to feel that the medical humanities curriculum contained unnecessary material (Fig. 2D). Finally, older students, but not younger students, thought it would be a good idea to include humanization courses in professional development (Fig. 2E). However, the differences between the groups did not reach a statistically significant level. (Fig. 2E).

Fig. 2.

Box plots (5–95 percentile) showing the scores obtained in response to questions A - E in the age groups. 2 A, Do you think that humanization/medical humanities classes are necessary for training as a nurse?; 2B, Is the content of humanization courses useful for nursing practice?; 2 C, Do you think that the time allotted for implementing the Humanization Classes is sufficient?; 2D, Do you think there was unnecessary content in the humanization classes?; 2E, In your opinion, should medical humanities content be systematically recalled in the form of on-the-job training? Age groups: 1 (18–29 years), 2 (30–39 years), 3 (40–49 years), 5 (50 + years). The between-group differences were calculated using Kruskal-Wallis and Dunn’s multiple comparisons test. *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.005; ***, p < 0.001. Created with BioRender.com

Next, correlation analyses were performed to ascertain the nature of the relationship between age and the variables in question. The age of the nursing students correlated positively with the Likert scale scores for questions indicating the importance of humanization courses in nursing education and negatively with the score indicating the presence of excessive content and the appropriateness of the time allocated to humanization courses (Table 3). A strong statistically significant correlation exists between age and professional experience (Spearman’s rho 0.868, p < 0.001). Not surprisingly, there is also a relationship between age and seniority, although Spearman’s rho correlation coefficients are slightly higher for age.

Table 3.

Correlation between nursing students’ age, seniority, and opinions on medical humanities courses

| Age | Seniority | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Agreement with (Likert 5-point scale) |

Spearman’s rho | p-value | Spearman’s rho | p-value |

| Do you think that humanization/medical humanities classes are necessary for training as a nurse? | 0.480 | p < 0.001 | 0.377 | p < 0.001 |

| Is the content of humanization courses useful for nursing practice? | 0.557 | p < 0.001 | 0.510 | p < 0.001 |

| Do you feel that the time allotted for implementing the Humanization Classes is sufficient? | -0.288 | p = 0.004 | -0.248 | p = 0.019 |

| Do you think there was unnecessary content in the humanization classes? | -0.394 | p < 0.001 | -0.383 | p < 0.001 |

| In your opinion, should medical humanities content be systematically recalled in the form of on-the-job training? | 0.345 | p < 0.001 | 0.300 | p = 0.004 |

N = 89

The data indicated that nurses with a certified specialization were more likely to hold positive views regarding the value of humanization courses, particularly in three key areas. These nurses were more likely to agree that the content presented was beneficial for their professional practice, to report utilizing the skills acquired in humanization courses in their professional role, and to express less agreement with the assertion that some content in humanization courses was superfluous (Table 4).

Table 4.

Professional nursing specialization and opinions on medical humanities courses

| Question | Definitely yes and somewhat yes % (n) | Hard to say % (n) |

Rather not and definitely not % (n) | Ch2 test | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Do you think that humanization/medical humanities classes are necessary for training as a nurse? | Has specialization | 68.2% (30) | 18.2% (8) | 13.6% (6) | Chi2 = 5.248 p = 0.73 |

| No specialization | 46.5% (20) | 20.9% (9) | 32.6% (14) | ||

| Total N = 87 | 57.5% (50) | 19.5% (17) | 23.0% (20) | ||

| Is the content of humanization courses practical for nursing practice? | Has specialization | 77.8% (35) | 15.6% (7) | 6.7% (3) | Chi2 = 10.830 p = 0.04 |

| No specialization | 46.5% (20) | 23.3% (10) | 30.2% (13) | ||

| Total N = 88 | 62.5% (55) | 19.3% (17) | 18.2% (16) | ||

| Do you feel that the time allotted for implementing the Humanization Classes is sufficient? | Has specialization | 80.0% (36) | 15.6% (7) | 4.4% (2) | Chi2 = 0.502 p = 0.778 |

| No specialization | 81.4% (35) | 11.6% (5) | 7.0% (3) | ||

| Total N = 88 | 80.7% (71) | 13.6% (12) | 5.7% (5) | ||

| Do you think there was unnecessary content in the humanization classes? | Has specialization | 15.6% (7) | 31.1% (14) | 53.3% (24) | Chi2 = 6.910 p = 0.032 |

| No specialization | 39.5% (17) | 27.9% (12) | 32.6% (14) | ||

| Total N = 88 | 27.3% (24) | 29.5%% (26) | 43.2% (38) | ||

| In your opinion, should medical humanities content be systematically recalled in the form of on-the-job training? | Has specialization | 62.2% (28) | 24.4% (11) | 13.3% (6) | Chi2 = 2.876 p = 0.237 |

| No specialization | 51.2% (22) | 20.9% (9) | 27.9% (12) | ||

| Total N = 88 | 56.8% (50) | 22.7% (20) | 20.5% (18) |

Discussion

This study aimed to determine nurses’ opinions toward the need for medical humanities education in nursing and the usefulness of the acquired knowledge in nursing practice. The main research question was whether nurses’ opinions towards medical humanities courses differ according to socio-demographic characteristics. The results suggest that the value placed on humanistic subjects (such as the humanization of medicine and communication with the patient or others) or the integration of acquired competencies into professional practice tends to increase with nurses’ age, seniority, and specialization. Older and more professionally advanced students tend to express more positive views regarding integrating medical humanities/humanization of medicine into the curriculum and utilizing the acquired skills in their professional practice. Our results are corroborated by those of Zhang and Thian (2024), who analyzed the opinions of 107 advanced undergraduate nursing students on humanistic education with a survey and a 5-point Likert scale [24]. One of their survey statements was, “It’s essential to provide nursing students with humanistic education”, which is similar to our question A (“Do you think that humanization/medical humanities classes are necessary for training as a nurse?”). The mean score in the study by Zhang and Thian in response to that statement was 4.59 ± 0.513, similar to the score of 4.45 ± 0.688 obtained in the present study for the oldest (50+) group of nurses (Fig. 2A). However, the younger groups in our study exhibited lower scores, despite obtaining a Bachelor of Science degree in nursing and at least a minimum of professional experience, such as mandatory internship. Interestingly, the age range of the participants in the study by Zhang and Thian was 17–24 years, with an average age of 20.9 ± 2.1 years. This discrepancy may indicate a divergence in cultural norms between the two countries, which agrees with the differences in perceptions of carrying between countries observed by Pajnkihar et al. [25] or result from other factors, such as differences in curricula.

The observed age-dependent students’ appreciation for humanization/humanities courses suggests a promising avenue of research that could be explored to potentially enhance teaching efficacy. While prior research has indicated that nurses tend to hold favorable views of humanization courses [26, 27], it would be beneficial to further examine these perceptions concerning age. Kevern and Webb observed a dearth of literature on educating older nurses [19]. Moreover, Andrew et al. noted an influx of mature individuals into the nursing profession and a need to adapt pedagogical strategies for this particular student population [28].

One strategy for expanding the scope of knowledge covered in humanization courses at different stages of life is implementing humanization in a specialized form of education. “Specialization and subspecialization are now inevitable due to the rapid development of medical knowledge (.) Specialized nurses have developed primarily because patients need more specific and detailed information about their health problems” [29]. According to the Polish Main Chamber of Nurses and Midwives, 78,625 nurses in Poland have a specialization [11]. The most popular specialties are anesthesiology, intensive care, surgery, and internal medicine. In our sample, there were more participants with a specialization than those without. The correlation between the perceived significance of humanization classes and specialization was less pronounced than between age and seniority. Nevertheless, individuals with a specialization demonstrated a statistically significant greater likelihood of reporting that the content presented in class was and continues to be beneficial in their professional endeavors compared to those without a specialization. Specialization offers the potential for acquiring work-related advantages. Tsirigoti et al. (2024) indicate that nurses pursue continuing professional education primarily to advance their careers and assure job security [30]. Additionally, some factors may act as barriers to pursuing professional development. These include the high cost of education, a lack of financial motivation following the completion of courses, a lack of suitable positions for those who have raised their qualifications, and the extensive time commitment required for education. This latter factor may be of particular importance for more mature individuals. Female students may encounter challenges in pursuing their studies if they bear the primary responsibility for family care, such as childrearing or caring for elderly parents [18]. One potential solution to this problem is to provide education in a more modern format. In agreement with that, a study by Stoddard and Schonfeld [31] showed that older nurses were likelier to choose an online form of ethics education over face-to-face education. Soafer suggests the material should be tailored to their needs when creating ethics courses for practicing mature nurses [32]. A recent study by Mangold et al. (2018) that examined general learning patterns among nursing staff supported the concept of tailored nursing education. The study found that nurses with professional experience exceeding 26 years preferred verbal learning. The same study demonstrated that male nurses and nursing staff who expressed satisfaction with the current educational system exhibited a proclivity for visual learning [33]. In a similar vein, Hallin (2014) examined the learning preferences of 263 nursing students (79.5% female) ranging in age between 21 and 48 years (mean 26.84; SD 5.27). Among other sex-related differences, the study revealed that women preferred verbal learning but did not identify age-related differences [34]. The emergence of novel training modalities, such as virtual reality or online sessions, may foster a greater inclination among nurses to pursue specialties. Nurses with specializations have unique skills and knowledge that distinguish them from nurses without specializations [35], possibly contributing to their greater ability to appreciate the practical aspects of using the knowledge taught in humanization courses. In support of these observations, nurses with specializations were significantly less likely to report redundant content in humanization courses than nurses without specializations. The results of our study indicate a correlation between the possession of a specialty and the positive opinions regarding humanization courses. This finding highlights the necessity for further comprehensive investigation.

According to Richardson, it is a myth that older students perform worse academically; in his opinion, more mature students have a deeper approach to academic work, and their learning is more purposeful [36]. Similar results were obtained in our study, as the feeling that humanization courses are essential in nursing education increased with age and seniority. The more senior the nurses, the more frequently they felt that their knowledge of humanization topics should be updated and that their practical application should be reinforced. With increasing age and seniority, they were also less critical of the unnecessary content of humanization courses and less likely to feel that the time allotted for learning was sufficient. This “appreciation” of the knowledge imparted in humanization courses by nurses with increasing age and seniority indicates that they recognize its relevance to their work. A meta-analysis of 11 studies by Hu et al. [37], that evaluated the effects of nursing education courses that included topics related to compassion and empathic communication concluded that such courses could improve humanizing care. Individual studies have reached similar conclusions [38–40]. Chiao and coworkers suggest that humanities courses may help retain nurses in the workplace by improving their psychological satisfaction [38].

This raises the question of what measures might be taken to enhance the appreciation of humanization issues among younger nurses. We assert that this objective could be achieved if senior colleagues shared their experiences and situations during the course, providing illustrative examples of challenging scenarios and strategies for addressing such difficulties, drawing upon the competencies acquired during the course. It would, therefore, be advisable for the university to consider incorporating interactive elements into the curriculum when devising courses designed to enhance humanization. One potential format for such a course would be a workshop. Furthermore, pedagogical approaches such as peer teaching, which has been demonstrated to be effective for nursing education, could be employed [41]. An excellent practice, now expected in medical schools, is conducting high-fidelity simulation learning sessions as best practices require. This method can allow nursing students to train and develop humanizing competencies, i.e., a greater sense of understanding, empathy, and caring. For younger nurses, the proposal to learn humanization through simulation can improve the nurse-patient relationship and increase awareness of the importance of the topic [42].

In the next few years, significant age differences among Polish nursing students are expected to disappear, and mainly young people will be educated in nursing faculties. This will result in a lack of opportunities for students to exchange experiences. Our study shows that experienced nurses could be invited to participate in humanization courses as tutors. It would also be worthwhile to create a platform for students to exchange experiences in the form of Balint groups or to develop graduate nursing associations that offer discussions and joint outings to museums, the cinema, or the theater. Previous research with nursing students of different ages has shown that they prefer other forms of learning [31, 43], which academics should also consider, considering the needs of both older and younger students.

It should be noted that the present study is not without limitations. The primary limitation is the participation of only one university’s nursing faculty. The specific context of a single institution, including the content delivered, may not fully represent the broader population of nursing students, and thus the results cannot be generalized. Furthermore, the study did not consider the qualifications of instructors, which could also be a significant factor influencing students’ perceptions of courses. It is also essential to consider that respondents may have had varying previous experiences with humanities courses, which could have influenced their responses. Finally, as discussed in the introduction, their educational experiences may have differed due to their varying ages.

A subsequent survey would be beneficial, employing a larger sample size and ideally drawn from multiple universities. However, it is essential to note that the participation of nurses-students of different ages and seniority is currently limited. Soon, there will be no more secondary vocational school graduates, as these individuals will have reached the age at which they are eligible for retirement. Furthermore, it would be advantageous to ascertain the respondents’ previous exposure to humanization courses.

In light of our survey findings, we present a few recommendations about practice and education. The initial recommendation for Poland and countries with comparable nursing education profiles includes incorporating sociodemographic characteristics into humanization courses for nurses. Furthermore, educators are advised to modify the content and pedagogical approaches to align with the diverse learning requirements of the learners. This will ensure that the material remains engaging, avoids repetition, and is not perceived as redundant. Additionally, it is recommended that the transfer of knowledge and experience from experienced, practicing nurses to their younger colleagues be recognized as a universal value, as it is a crucial aspect of professional development.

Conclusions

We conclude that the education of nurses on the humanization of medicine is crucial for the future healthcare system and is considered as such, especially by nursing students who are older and have more professional experience. Furthermore, nursing students’ professional experience and age should be considered when planning and implementing humanization courses. Older students could share their knowledge and experience with the younger ones. Such a partnership could be implemented by using an appropriate form of teaching, such as simulations or workshops, to create an opportunity for discussion and sharing of insights. Even if the age gap between nursing students disappears in the future, this type of activity would retain its desirable integrative character.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Author contributions

Conceptualization and methodology: A.J.S., J.H-A. and M.L-P., formal analysis, M.M. and A.J.S.; writing—original draft preparation, M.M., A.J.S., J.H-A. and M.L-P., writing—review and editing, M.M., A.J.S., and A.J.S prepared the figures. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Funding

This study received no funding.

Open Access funding was enabled by the Institute of Health Sciences, University of Zielona Góra.

Data availability

The datasets used are available from the corresponding author on request.

Declarations

Ethical approval and consent to participate

Ethics approval was obtained from the Bioethics Committee of the Medical College of the University of Zielona Góra (approval number RCM-CM-KBUZ.031.16.2023). The study was performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. Informed consent was obtained from all participants of the study.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing interest.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Létourneau D, Goudreau J, Cara C. Nursing students and nurses’ recommendations aiming at improving the development of the Humanistic Caring Competency. Can J Nurs Res. 2022;54(3):292–303. 10.1177/08445621211048987 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nyborg VN, Hvalvik S. Revealing historical perspectives on the professionalization of nursing education in Norway-Dilemmas in the past and the present. Nurs Inq. 2022;29(4):e12490. 10.1111/nin.12490 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.McCaffrey G. A humanism for nursing? Nurs Inq. 2019;26(2):e12281. 10.1111/nin.12281 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fontesse S, Demoulin S, Stinglhamber F, Maurage P. Dehumanization of psychiatric patients: experimental and clinical implications in severe alcohol-use disorders. Addict Behav. 2019;89:216–23. 10.1016/j.addbeh.2018.08.041 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Trifiletti E, Di Bernardo GA, Falvo R, Capozza D. Patients are not fully human: a nurse’s coping response to stress. J Appl Soc Psychol. 2014;44(12):768–77. 10.1111/jasp.12267 [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bellier-Teichmann T, Roulet-Schwab D, Antonini M, Brandalesi V, O’Reilly L, Cara C, et al. Transformation of clinical nursing practice following a caring-based Educational intervention: a qualitative perspective. SAGE Open Nurs. 2022;8:23779608221078100. 10.1177/23779608221078100 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Erci B, Sayan A, Tortumluoǧlu G, Kiliç D, Şahin O, Güngörmüş Z. The effectiveness of Watson’s Caring Model on the quality of life and blood pressure of patients with hypertension. J Adv Nurs. 2003;41(2):130–9. 10.1046/j.1365-2648.2003.02515.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Godino L, La Malfa E, Ricco M, Mancin S, Ambrosi E, De Rosa M, et al. Parents’ and nurses’ affective perception of a pictorial intervention in a pediatric hospital environment: quasi-experimental design pre-post-testing. J Pediatr Nurs. 2024;77:89–95. 10.1016/j.pedn.2024.03.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Meneses-La-Riva ME, Suyo-Vega JA, Fernández-Bedoya VH. Humanized Care from the nurse-patient perspective in a hospital setting: a systematic review of experiences disclosed in Spanish and Portuguese scientific articles. Front Public Health. 2021;9:737506. 10.3389/fpubh.2021.737506 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.GUS. Human resources in selected medical professions based on administrative sources in 2022. 2023. https://stat.gov.pl/en/topics/health/health/human-resources-in-selected-medical-professions-based-on-administrative-sources-in-2022,20,1.html. Accessed 29.10.2023.

- 11.NIPIP. [Report of the Main Chamber of Nurses and Midwives. Nurses and midwives - deficit professions in the Polish Health Care System]. Polish Main Chamber of Nurses and Midwives. 2022. https://nipip.pl/wp-content/uploads/2022/06/2022_Raport-NIPiP-struktura-wiekowa-kadr.pdf. Accessed 29.10.2023 2023.

- 12.Marć M, Bartosiewicz A, Burzyńska J, Chmiel Z, Januszewicz P. A nursing shortage - a prospect of global and local policies. Int Nurs Rev. 2019;66(1):9–16. 10.1111/inr.12473 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Directive. 2005/36/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 7 September 2005 on the recognition of professional qualifications, 02005L0036-20231009 (2005).

- 14.Directive 2013/55/EU of the European Parliament. Council L. 2013;354:132. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Act of 15 July 2011 on the occupation of nurses and midwives. (2012).

- 16.Act of 27 July 2005 on Higher Education. (2005).

- 17.Davies R. The Bologna process: the quiet revolution in nursing higher education. Nurse Educ Today. 2008;28(8):935–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ślusarska B, Zarzycka D, Dobrowolska B, Marcinowicz L, Nowicki G. Nursing education in Poland - the past and new development perspectives. Nurse Educ Pract. 2018;31:118–25. 10.1016/j.nepr.2018.05.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kevern J, Webb C. Mature women’s experiences of preregistration nurse education. J Adv Nurs. 2004;45(3):297–306. 10.1046/j.1365-2648.2003.02890.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Walewska E, Radzik T, [Stefania Poznanska. (1923–2010) - a teacher, nursing tutor]. Problemy Pielęgniarstwa. 2011;19(2).

- 21.Dec-Pietrowska J, Szczepek AJ. A study of differences in Compulsory Courses Offering Medicine Humanization and Medical Communication in Polish Medical schools: content analysis of secondary data. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(24). 10.3390/ijerph182413326 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 22.Makowska M, Dec-Pietrowska J, Szczepek AJ. Expectations of Polish undergraduate medical students for medical humanities classes: a survey-based pilot study. BMC Med Educ. 2023;23(1):775. 10.1186/s12909-023-04771-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Makowska M, Szczepek AJ, Nowosad I, Weissbrot-Koziarska A, Dec-Pietrowska J. Perception of Medical Humanities among Polish Medical students: qualitative analysis. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;20(1). 10.3390/ijerph20010270 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 24.Zhang J, Tian Y. Final-year nursing students’ perceptions of humanistic education in nursing: a cross-sectional descriptive study. BMC Med Educ. 2024;24(1):392. 10.1186/s12909-024-05377-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pajnkihar M, Kocbek P, Musović K, Tao Y, Kasimovskaya N, Štiglic G, et al. An international cross-cultural study of nursing students’ perceptions of caring. Nurse Educ Today. 2020;84:104214. 10.1016/j.nedt.2019.104214 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Marnocha S, Marnocha M. Windows open: humanities teaching during undergraduate clinical experiences. J Nurs Educ. 2007;46(11):518–21. 10.3928/01484834-20071101-07 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Darbyshire P. Understanding caring through arts and humanities: a medical/nursing humanities approach to promoting alternative experiences of thinking and learning. J Adv Nurs. 1994;19(5):856–63. 10.1111/j.1365-2648.1994.tb01161.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Andrew L, Dare J, Robinson K, Costello L. Nursing practicum equity for a changing nurse student demographic: a qualitative study. BMC Nurs. 2022;21(1):37. 10.1186/s12912-022-00816-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Castledine G. Are specialist nurses deskilling general nurses? Br J Nurs. 2000;9(11):738. 10.12968/bjon.2000.9.11.6265 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tsirigoti A, León-Mantero C, Jiménez-Fanjul N. Motivation for continuing education in nursing. Educación Médica. 2024;25(2):100877. 10.1016/j.edumed.2023.100877 [Google Scholar]

- 31.Stoddard HA, Schonfeld T. A comparison of student performance between two instructional delivery methods for a healthcare ethics course. Camb Q Healthc Ethics. 2011;20(3):493–501. 10.1017/s0963180111000181 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sofaer B. Enhancing humanistic skills: an experiential approach to learning about ethical issues in health care. J Med Ethics. 1995;21(1):31–4. 10.1136/jme.21.1.31 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mangold K, Kunze KL, Quinonez MM, Taylor LM, Tenison AJ. Learning style preferences of practicing nurses. J Nurses Prof Dev. 2018;34(4):212–8. 10.1097/nnd.0000000000000462 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hallin K. Nursing students at a university - a study about learning style preferences. Nurse Educ Today. 2014;34(12):1443–9. 10.1016/j.nedt.2014.04.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Fairweather C, Gardner G. Specialist nurse: an investigation of common and distinct aspects of practice. Collegian. 2000;7(2):26–33. 10.1016/s1322-7696(08)60362-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Richardson JTE. Mature students in higher education: I. A literature survey on approaches to studying. Stud High Educ. 1994;19(3):309–25. 10.1080/03075079412331381900 [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hu JX, Chang R, Du JQ, He M. Effect of training on the ability of nurses to provide Humanistic Care: systematic review and Meta-analysis. J Contin Educ Nurs. 2023;54(9):430–6. 10.3928/00220124-20230816-12 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chiao LH, Wu CF, Tzeng IS, Teng AN, Liao RW, Yu LY, et al. Exploring factors influencing the retention of nurses in a religious hospital in Taiwan: a cross-sectional quantitative study. BMC Nurs. 2021;20(1):42. 10.1186/s12912-021-00558-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kuo YL, Lee JT, Yeh MY. Intergenerational narrative learning to Bridge the Generation gap in humanistic care nursing education. Healthc (Basel). 2021;9(10). 10.3390/healthcare9101291 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 40.Létourneau D, Goudreau J, Cara C. Humanistic caring, a nursing competency: modelling a metamorphosis from students to accomplished nurses. Scand J Caring Sci. 2021;35(1):196–207. 10.1111/scs.12834 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Dikmen Y, Ak B, Yildirim Usta Y, Ünver V, Akin Korhan E, Cerit B, et al. Effect of peer teaching used in nursing education on the performance and competence of students in practical skills training. Int J Educational Sci. 2017;16(1–3):14–20. 10.1080/09751122.2017.1311583 [Google Scholar]

- 42.Jiménez-Rodríguez D, Pérez-Heredia M, Molero Jurado MDM, Pérez-Fuentes MDC, Arrogante O. Improving humanization skills through Simulation-based computers using simulated nursing video consultations. Healthc (Basel). 2021;10(1). 10.3390/healthcare10010037 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 43.Walker JT, Martin T, White J, Elliott R, Norwood A, Mangum C, et al. Generational (age) differences in nursing students’ preferences for teaching methods. J Nurs Educ. 2006;45(9):371–4. 10.3928/01484834-20060901-07 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used are available from the corresponding author on request.