Abstract

A possible role in RNA replication for interactions between conserved complementary (cyclization) sequences in the 5′- and 3′-terminal regions of Flavivirus RNA was previously suggested but never tested in vivo. Using the M-fold program for RNA secondary-structure predictions, we examined for the first time the base-pairing interactions between the covalently linked 5′ genomic region (first ∼160 nucleotides) and the 3′ untranslated region (last ∼115 nucleotides) for a range of mosquito-borne Flavivirus species. Base-pairing occurred as predicted for the previously proposed conserved cyclization sequences. In order to obtain experimental evidence of the predicted interactions, the putative cyclization sequences (5′ or 3′) in the replicon RNA of the mosquito-borne Kunjin virus were mutated either separately, to destroy base-pairing, or simultaneously, to restore the complementarity. None of the RNAs with separate mutations in only the 5′ or only the 3′ cyclization sequences was able to replicate after transfection into BHK cells, while replicon RNA with simultaneous compensatory mutations in both cyclization sequences was replication competent. This was detected by immunofluorescence for expression of the major nonstructural protein NS3 and by Northern blot analysis for amplification and accumulation of replicon RNA. We then used the M-fold program to analyze RNA secondary structure of the covalently linked 5′- and 3′-terminal regions of three tick-borne virus species and identified a previously undescribed additional pair of conserved complementary sequences in locations similar to those of the mosquito-borne species. They base-paired with ΔG values of approximately −20 kcal, equivalent or greater in stability than those calculated for the originally proposed cyclization sequences. The results show that the base-pairing between 5′ and 3′ complementary sequences, rather than the nucleotide sequence per se, is essential for the replication of mosquito-borne Kunjin virus RNA and that more than one pair of cyclization sequences might be involved in the replication of the tick-borne Flavivirus species.

Despite its essential role in the virus replication cycle as a template for the synthesis of minus-strand RNA, the conformation of the genomic RNA of Flavivirus species has not been defined. Particularly important is the mode of its presentation to the RNA-dependent RNA polymerase NS5, and possibly other components of the replicase complex (RC) (28, 51), in order for copying to commence correctly from the 3′ end. The size of the Flavivirus genome is about 11 kb, and the complete nucleotide sequence is available for a range of species, (7, 12, 14–16, 18, 25, 27, 29, 33, 40, 45, 54). All sequences share a common gene order (5′-C prM E NS1 NS2A NS2B NS4A NS4B NS5-3′), i.e., structural (C, prM, and E) followed by nonstructural (NS) genes, and are flanked by 5′ and 3′ untranslated regions (UTR) of about 100 and 600 nucleotides, respectively (39). Conserved complementary cyclization sequences (CS) of 8 nucleotides in the 5′ region of the core, or capsid, gene, and in the 3′ UTR, were noted in genomic RNA for several mosquito-borne species (20). Hahn et al. (20) suggested that cyclization of Flavivirus genomic RNA could “help ensure that virus RNA molecules that are replicated are full-length RNA, if a viral replicase were required to bind to both 5′ and 3′ regions simultaneously in order to initiate RNA replication.” For Kunjin virus (KUN) RNA, these CS are located at nucleotides 137 to 144 in the 5′ region and at nucleotides 97 to 104 from the 3′ terminus (see Fig. 1A). Another important sequence in replication may be the conserved pentanucleotide loop 5′-CACAG(A/U)-3′ (49) in the upper half of the 3′-terminal stem-loop, also described as the 3′ long stable hairpin structure (37).

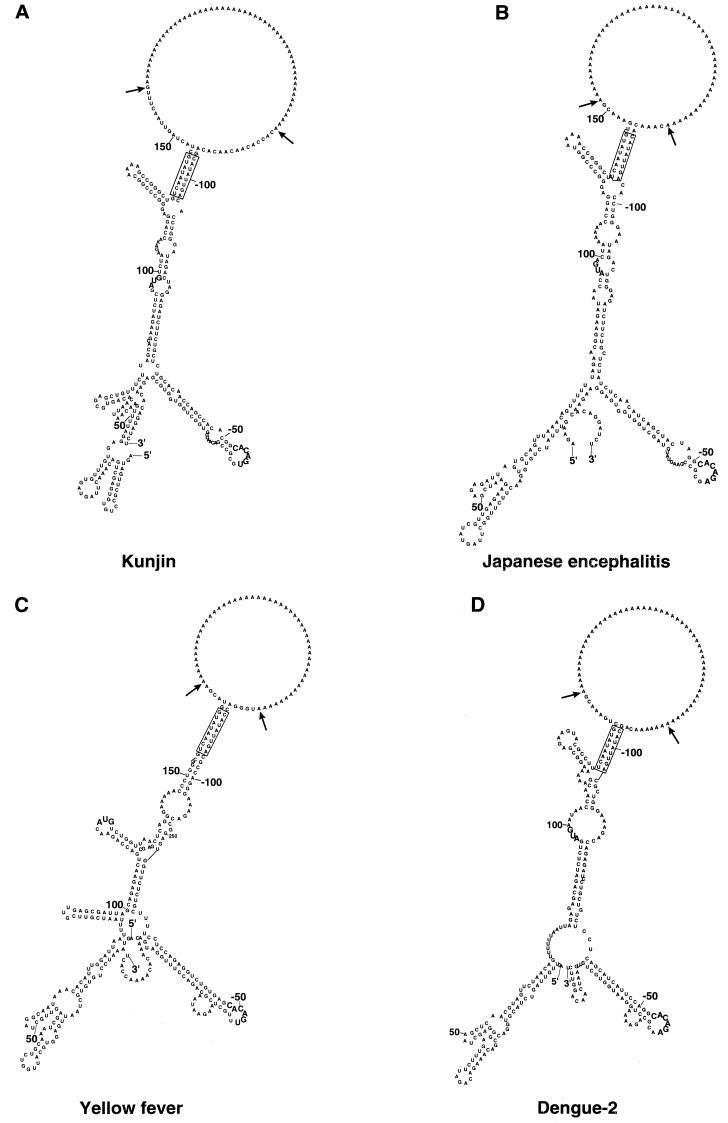

FIG. 1.

Computer-generated secondary-structure analysis of the interaction between the genomic plus-strand RNA at the 5′ and 3′ ends for four mosquito-borne flaviviruses. The predicted secondary structures of the proposed CS and some flanking sequences connected by a poly(A) insert were produced using version 3.0 of the M-fold program (31, 55). The conserved putative CS are boxed. The arrows indicate insertion points for the stuffer poly(A) sequence. The AUG initiation codon and the conserved pentanucleotide loop [5′-CACAG(A/U)-3′] in the 3′-terminal stem-loop are shown in bold. Nucleotides are numbered from the 5′ and 3′ termini. (A) KUN (12, 25); (B) Japanese encephalitis virus (45); (C) yellow fever virus vaccine strain 17D (40); (D) DEN-2 (15). The relevant GenBank accession numbers are shown in Table 1.

During the initial copying of KUN genomic RNA, double-stranded RNA was formed, and on completion, this replicative form (RF) was shown to function as a recycling template from which progeny RNA plus strands were copied in an asymmetric and semiconservative manner via a replicative intermediate with an average of only one nascent RNA strand (9, 11, 50). At least during replication of KUN replicon RNA, no free minus-strand RNA appears to be present in the cells (26). In order to analyze minus-strand RNA synthesis in vitro, the putative RNA polymerase (NS5) of dengue virus type 1 (DEN-1), West Nile virus, and KUN has been expressed either in Escherichia coli or from recombinant baculoviruses (19, 43, 47). These purified NS5 proteins exhibited relatively weak RNA-dependent RNA polymerase activity on RNA templates representing the homologous RNA templates and also on nonspecific RNA templates (19, 43, 47). Using the endogenous DEN-2 RC in infected cell lysates and exogenous truncated viral RNA templates, You and Padmanabhan (52) showed that self-primed RNA synthesis occurred by elongation of the authentic 3′ end of the template RNA. Interestingly, the RNA synthesis required both 5′- and 3′-terminal regions containing the conserved cyclization motifs, either connected in one molecule or with the isolated (not linked) 5′-terminal region added in trans to the 3′-terminal region. Mutation of the conserved CS in either the 5′ or 3′ region blocked this elongation, but elongation ability was restored when both regions contained compensatory mutations that allowed interaction between them. Because these experiments measured only 3′-terminal elongation and copy back of the 3′-terminal plus-strand RNA to yield predominantly a double-stranded hairpin molecule, no evidence was obtained of de novo minus-strand RNA synthesis, the first and essential prerequisite for enabling subsequent synthesis of progeny plus-strand RNA during the normal replication cycle.

The most convincing evidence for an essential role of the CS must come from analyses of Flavivirus RNA replication in cells. For this purpose we used the KUN replicon RNA, which has a deletion of most of the structural gene region but is still able to replicate autonomously after transfection into cells (26). The results obtained using RNAs with wild-type and mutated CS, or RNAs with compensatory mutations in these 5′ and 3′ sequences, showed that complementary cyclization motifs are essential for viral RNA replication in vivo.

Computer-generated conformation of the linked 5′ and 3′ regions of KUN RNA.

We first verified that the covalently linked CS, each flanked by longer sequences representing the 5′ region (first 150 to 170 nucleotides) and part of the 3′ UTR (last 110 to 120 nucleotides) of genomic RNA from four mosquito-borne Flavivirus species and separated from each other by a stuffer poly(A) sequence, could hybridize to form a proposed panhandle RNA structure using the M-fold program (31, 55) (Fig. 1). Base-pairing of the proposed CS clearly occurred for all four species of RNA. Because of base-pairing elsewhere between the 5′ and 3′ sequences, i.e., upstream and downstream of the CS, respectively, the conformations differ from those obtained previously from comparable regions analyzed only as either the 5′ or 3′ sequence of several other mosquito-borne species. The previous analyses of secondary structures for isolated 5′- or 3′-terminal regions, obtained either by computer predictions or by biochemical analyses, uniformly showed the presence of terminal stem-loops, each of about 100 nucleotides. The 3′ stem-loop was reported to be particularly well conserved in structure (although variants were noted) in all publications reviewed (3, 4, 17, 18, 20, 29, 30, 35–38, 40–42, 46, 49, 53). Only the upper half of the 3′-terminal stem-loop (nucleotides −15 to −66 for KUN) in the conserved secondary structure of the isolated 3′ UTR was retained (Fig. 1). This upper half comprises the previously reported secondary structure shown to be important for the replication of DEN-2 (53). Pertinently, NS3 and NS5 of Japanese encephalitis virus were shown to cooperatively bind to the 3′-terminal stem-loop by Chen et al. (8), who suggested that this binding may facilitate the process for minus-strand RNA synthesis. Furthermore, in gel shift assays the 3′-terminal stem-loop of DEN-1 RNA containing the pentanucleotide loop bound to NS3 (13). The binding of NS3 to the N-terminal regions of NS5 during their translation was suggested by complementation experiments involving deletion analyses of the KUN genome (24). Such binding, possibly involving other components of the assembling RC, such as NS2A (23) and/or cellular proteins (1, 2), to the upper portion of the 3′ stem-loop, e.g., the conserved pentanucleotide loop, may facilitate the cyclization process. There appears to be no opportunity in our M-fold-program-predicted models of 5′ and 3′ interactions (Fig. 1) for formation of the pseudoknot involving the lower half of the 3′-terminal stem-loop, as was proposed in the computer-predicted secondary structures of the isolated 3′ UTR of West Nile virus, yellow fever virus, and DEN-3 RNAs (41).

Computer-generated secondary structures of the 5′-terminal region of RNA of several Flavivirus species contain a terminal stem-loop incorporating a nonconserved loop and bulges (4). Cahour et al. (5) showed that most of several small (5- or 6-nucleotide) deletions between nucleotides 55 and 98 in the 5′ UTR of DEN-4 RNA were lethal. This region varied in secondary structure for the four viruses shown in Fig. 1. In the present analyses, two small stem-loops appeared in the first 70 nucleotides of the 5′ region, and thereafter, base-pairing occurred with 3′-terminal sequences, interspersed with an additional one or two stem-loops involving only the 5′ nucleotide sequence. To obtain viable KUN replicon RNA, it was essential to include the first 60 nucleotides of the core gene, which incorporates the 5′ CS (26). Overall, the patterns of structures produced by the M-fold program and shown in Fig. 1 have only limited similarity apart from the base-pairing of the CS. Notably, all stem-loops are formed by base-pairing only within an individual sequence of a 5′ or 3′ region; none involve direct interaction between the 5′ and 3′ regions. The secondary structures produced by the M-fold program and shown in Fig. 1 require confirmation using analyses of the whole genome, as employed for topological organization of picornaviral genomes (34). However, the large size of the Flavivirus RNA (11 kb) precludes such analyses at present.

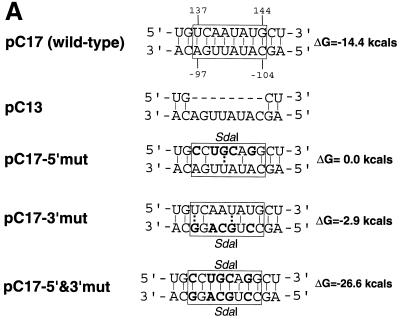

Having established in principle that base-pairing of the CS is feasible in the KUN replicon RNA sequence, we mutated them in order to observe the effects on conformation (using the M-fold program) and replication in transfected cells. Figure 2A shows the relevant mutations and the designations of plasmids containing the cDNA for transcription. The wild-type sequence copied from pC17 includes both the conserved 5′ and 3′ CS (20) with flanking sequences as shown in Fig. 1A. In pC13, the 5′ cyclization motif has been deleted. In pC17-5′mut and pC17-3′mut, five mutations were introduced that left only three of the original eight base-pairings in the CS. Both sets of mutations were combined in pC17-5′&3′mut as compensatory mutations so as to restore the original number of base-pairings in the CS. When the secondary-structure analyses of the interactions between the wild-type and mutated 5′ and 3′ ends were compared by the M-fold program as shown in Fig. 1 and 2B, it was found that only the sequence with combined compensatory mutations (pC17-5′&3′mut) was able to achieve the base-pairing conformation and structure comparable to those of the wild-type sequence pC17. The structures of the mutants pC17-5′mut and pC17-3′mut showed drastic changes in the M-fold pattern (Fig. 2B); the deletion mutant pC13 also obviously differed substantially in structure from the wild type (result not shown).

FIG. 2.

Nucleotide sequence and secondary-structure analysis of wild-type and mutant KUN replicon RNAs. (A) Interaction between 5′ and 3′ ends of the putative cyclization motif (shown in boxes). Mutated nucleotides are shown in bold. Dashes indicate deleted nucleotides. The ΔG values shown are for base-pairing of the boxed CS. (B) Computer-generated secondary-structure analysis of the interaction between the genomic plus-strand RNA at the 5′ and 3′ ends of wild-type and mutant KUN replicon RNAs. The predicted secondary structures of the proposed CS and some flanking sequences connected by a poly(A) insert were produced using the M-fold program as for Fig. 1. The boxes enclose either the conserved cyclization motifs or the relevant mutated sequences. The arrows indicate insertion points for the stuffer poly(A) sequence. The AUG initiation codon and the conserved pentanucleotide loop [5′-CACAC(A/U)-3′] in the 3′-terminal stem-loop are shown in bold. Nucleotides are numbered from the 5′ and 3′ termini.

Effects of mutations in CS on RNA replication in vivo.

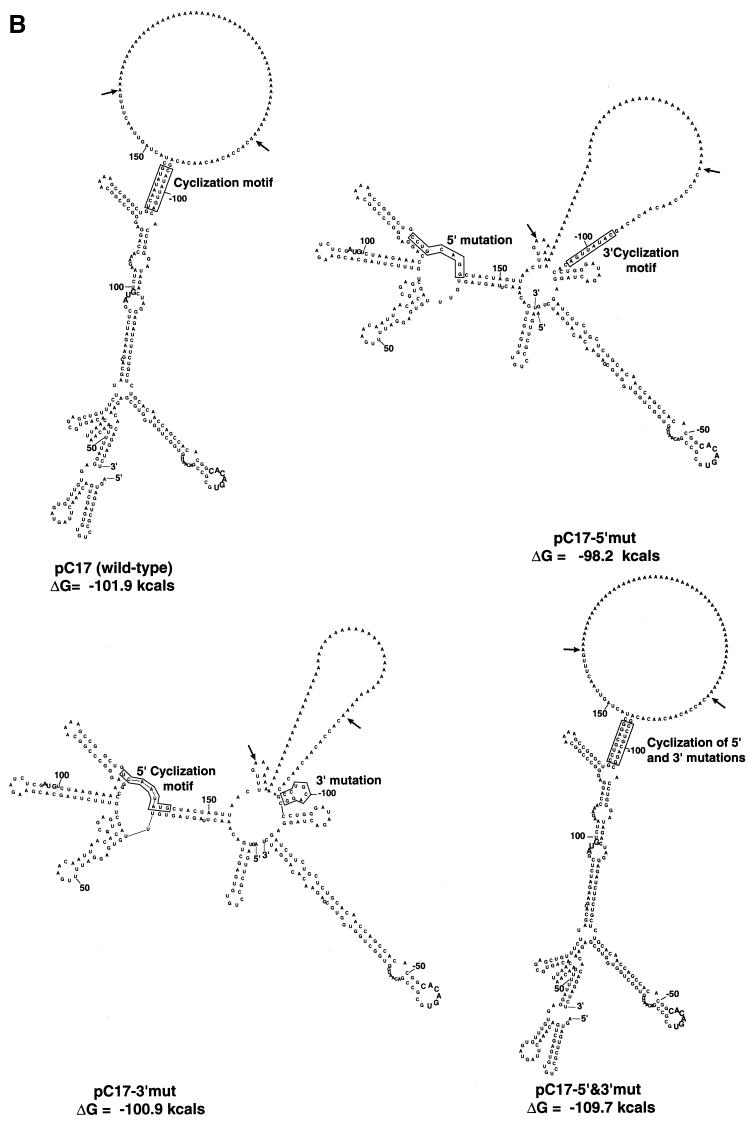

In order to ascertain the effect of the mutations on replication, KUN replicons incorporating the mutations shown in Fig. 2 into the wild-type replicon sequence of the plasmid pC17 (derivative of C20DXrep) were constructed (22). Briefly, cDNA fragments containing mutated KUN 5′ and/or 3′ regions were obtained by PCR amplification, using the appropriate primers with incorporated mutations and restriction sites, and cloned into pC17, replacing the wild-type sequences. (Further details of plasmid construction can be obtained from the corresponding author upon request.) Replicon RNAs were transcribed in vitro and subsequently transfected by electroporation into BHK cells as previously described (26). Amplification and expression of the replicon RNAs were initially monitored by immunofluorescence (IF) using antibodies to KUN NS3 at various time intervals as described previously (51). Most of the cells were strongly positive by IF at 24 h after transfection with the wild-type KUN replicon pC17, compared with only a small number of cells for the compensatory mutant pC17-5′&3′mut (Fig. 3). However, the number of strongly positive cells increased severalfold later in transfection with pC17-5′&3′mut RNA, and nearly all cells were strongly positive by 36 and 48 h after transfection. No positive cells were observed at 48 or 72 h after transfection for any of the other mutants.

FIG. 3.

Detection of replication and expression of the wild-type and mutated KUN replicon RNAs by IF analysis. BHK cells were electroporated with ∼5 to 10 μg of in vitro-transcribed wild-type and mutated replicon RNAs as described previously (26) and assayed for expression of the NS3 protein by IF analysis with anti-NS3 antibodies (51) at 24, 36, and 48 h after electroporation. Panels 1 to 3 show the results of IF analysis of the wild-type (pC17) RNA, and panels 4 to 6 show the corresponding results for cells transfected with RNA containing simultaneous compensatory mutations in the 5′ and 3′ CS (pC17-5′&3′mut). Transfection with RNAs containing mutations only in the 5′- and 3′-terminal regions (pC17-5′mut and pC17-3′mut, respectively) (Fig. 2A) did not result in the detection of NS3-positive cells.

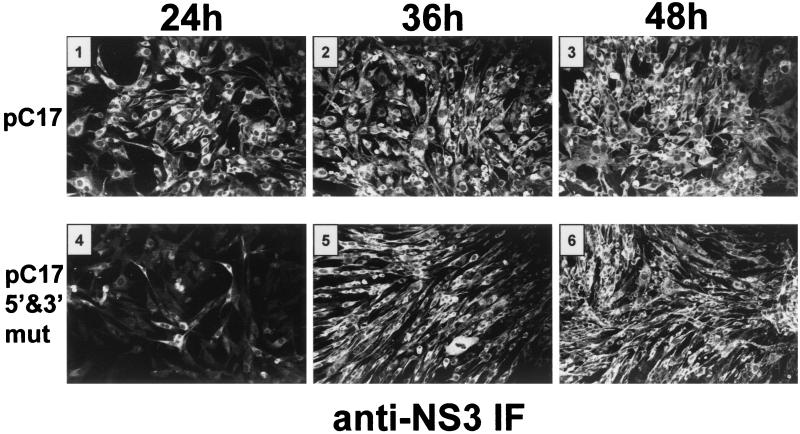

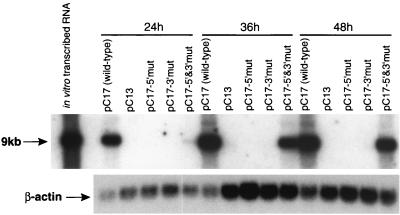

We next examined the accumulation of replicating RNA by Northern blot assay. RNA was extracted from the transfected BHK cell cultures at 24, 36, and 48 h and assayed for viral RNA content by Northern blot analysis (Fig. 4) as described previously (26). No viral RNA was detected in cells transfected with the mutated RNAs designated pC13, pC17-5′mut, and pC17-3′mut, in accord with the IF results showing the lack of expression of NS3. A positive signal was obtained at 24 h with the compensatory mutant pC17-5′&3′mut, although the signal was very weak. However, the signal shown by Northern blotting from the compensatory mutant increased dramatically by 36 and 48 h; this increase correlated well with the increase in the number of positive cells and the intensity of IF staining. The low signal shown by Northern blotting and the small number of IF-positive cells at 24 h for the compensatory mutant indicate inefficient early RNA replication leading to an extended delay in expression and attainment of the threshold of protein (NS3) required for detection by IF. The retention of introduced mutations in both the 5′ and 3′ ends of pC17-5′&3′mut RNA during its amplification in transfected cells was confirmed by restriction digest analysis with SdaI restrictase of the DNA fragments obtained by reverse transcription-PCR amplification with appropriate primers of a total cellular RNA isolated 48 h after transfection (data not shown).

FIG. 4.

Northern blot showing effects of mutations in the cyclization motifs on replication of KUN replicon RNA. BHK cells were electroporated with ∼5 to 10 μg of in vitro-transcribed wild-type and mutated replicon RNAs as described previously (26), and total cellular RNA was harvested with Trizol (Gibco BRL) at 24, 36, and 48 h postelectroporation. Fifteen micrograms of total cellular RNA was separated electrophoretically in a 1% agarose gel under fully denaturing conditions and transferred to nylon (Hybond-N; Amersham), and the blot was probed simultaneously with two 32P-labeled cDNA fragments encompassing either the entire KUN 3′ UTR or 291 nucleotides of human β-actin sequence. The upper panel was exposed to X-ray film for 22 h; the arrow indicates the position of RNA of ca. 9 kb. The lower panel was exposed for 2 h, and it indicates the relative abundance of the β-actin transcript in each RNA sample.

In earlier in vivo experiments, deletions of as many as 352 nucleotides after the stop codon in the KUN replicon, which left the 3′-terminal 272 nucleotides (including the 3′ CS) intact, partially inhibited RNA replication but were not lethal (26). Deletions in the DEN-4 3′ UTR of 30 to 262 nucleotides, including all but the 113 3′-terminal nucleotides, still permitted the recovery of progeny virus (32). However, a deletion of an additional 30 nucleotides was lethal; this region included the DEN-4 3′ CS (3′-terminal nucleotides −92 to −99) equivalent to those shown in Fig. 1 for other mosquito-borne viruses.

Comparisons with possible cyclization motifs in RNA of Flavivirus species not transmitted by mosquitoes.

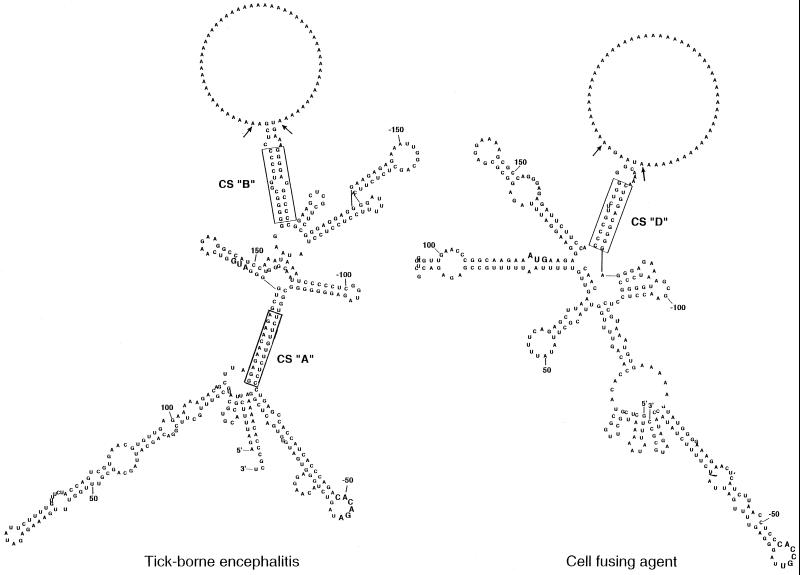

The genus Flavivirus includes a total of about 60 species (21). In addition to the numerous mosquito-borne Flavivirus species, there are a number of tick-borne viruses and some other species with no known vector. The conserved cyclization motifs first reported by Hahn et al. (20) for mosquito-borne viruses are absent in the other reported sequences. Putative CS were proposed in tick-borne encephalitis (TBE) virus RNA located at nucleotides 114 to 124 (5′ region) and at nucleotides 11061 to 11071 in the 3′ UTR (29). As successive deletions in the 3′ UTR progressed downstream from the variable region (nucleotides 10376 to 10795) into the core element, a deletion terminating at nucleotide 10919 severely impaired replication and a further deletion extending to nucleotide 10994 was lethal (29). In this last deletion mutant the proposed 3′ CS was still retained in the terminal sequence from nucleotides 10995 to 11141. We therefore scanned the TBE virus RNA sequence between nucleotides 10795 and 10994 and continued to the 3′-terminal nucleotide 11141 using the M-fold program as used for Fig. 1 for any base-pairing with the 5′ region (Fig. 5). In addition to base-pairing in the CS, proposed by Mandl et al. (30) and shown here as CS “A,” interactions were also observed between nucleotides 164 to 174 (5′ region) and nucleotides 10949 to 10958 (3′ UTR), shown as CS “B” in Fig. 5. These complementary sequences were conserved at corresponding locations in several TBE virus strains as well as in Powassan (POW) and louping ill viruses (Table 1) (18, 29, 48).

FIG. 5.

Computer-generated secondary structures of the interaction between the RNA at the 5′ and 3′ ends of TBE virus (29) and of CFA (6). The predicted secondary structures of the proposed CS and some flanking sequences connected by a poly(A) insert were produced using the M-fold program as for Fig. 1. The putative CS are boxed. The arrows indicate insertion points for the stuffer poly(A) sequence. The AUG initiation codon and the conserved pentanucleotide loop [5′-CACAG(A/U)-3′] in the 3′-terminal stem-loop are shown in bold. Nucleotides are numbered from the 5′ and 3′ termini.

TABLE 1.

Relative locations of proposed CS in genomic RNA of Flavivirus species

| Virus | Translation initiationa | Proposed CS and locationb | GenBank accession no. | Reference for CS |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mosquito-borne | 5′-UCAAUAUG——| | 20 | ||

| 3′-AGUUAUAC◂— | ||||

| KUN | 97 | 5′(137) (−104)3′ | D00246, L24511, L24512 | Fig. 1 |

| Japanese encephalitis virus | 96 | 5′(136) (−111)3′ | M10370 | Fig. 1 |

| Murray Valley encephalitis virus | 96 | 5′(136) (−111)3′ | NC000943 | 20 |

| West Nile virus | 97 | 5′(137) (−105)3′ | M12294 | 20 |

| DEN-1 | 81 | 5′(118) (−103)3′ | M87512 | Compare Fig. 1 |

| DEN-2 | 97 | 5′(134) (−103)3′ | M20558 | Fig. 1 |

| DEN-3 | 94 | 5′(132) (−103)3′ | M93130 | Compare Fig. 1 |

| DEN-4 | 102 | 5′(136) (−99)3′ | M14931 | Compare Fig. 1 |

| Yellow fever virus | 119 | 5′(156) (−112)3′ | NC002031 | Fig. 1 |

| CFA | 114 | 5′(169)CCCCGUUCUGG | M91671 | Fig. 5, CS “D” |

| 3′ GGGGCA-GGUC(−134) | ||||

| 114 | 5′(149)GCCAGGG | M91671 | 6; CS “C” | |

| 3′ CGGUCCC(−471) | ||||

| Tick-borne | ||||

| TBE virus | 133 | 5′(164)GGGGCGGUCCC | U27495 | Fig. 5, CS “B” |

| 3′ CCCCGGAGGG(−193) | ||||

| POW virus | 112 | 5′(136)GGGGGCGGUCC | L06436 | Fig. 5, CS “B” |

| 3′ CCCCCG––AGG(−189) | ||||

| Louping ill virus | 130 | 5′(160)GGGGGCGGUCC | Y07863 | Fig. 5, CS “B” |

| 3′ CCCCCGGAGG(−193) | ||||

| TBE virus | 133 | 5′(115)GGAGAACAAGA | U27495 | 29; Fig. 5, CS “A” |

| 3′ CCUCUUGUUCU(−81) | ||||

| POW virus | 112 | 5′ (88)GGAGAACAAGA | L06436 | 29 |

| 3′ CCUCUUGUUCU(−81) | ||||

| Louping ill virus | 130 | 5′(112)GGAGAACAAGA | Y07863 | 18 |

| 3′ CCUCUUGUUCU(−81) |

Numbered position of first nucleotide in the AUG codon.

The 5′ and 3′ CS shown are base-paired. The first nucleotide of each of the CS is shown in bold. Additional but nonconserved base pairs flanking the CS of the mosquito-borne viruses are not shown. Positions of the first nucleotide of each CS in relation to the 5′ terminus or the 3′ terminus of each genome are shown in bold within parentheses.

Cell fusing agent (CFA) was isolated from a mosquito cell line (44) and is classified as a tentative Flavivirus species (21). In the CFA genome, three sequences of 6, 7, and 12 nucleotides (designated A, B, and C, respectively) in the 5′ region, which are complementary to three sequences in the 3′ UTR, were noted by Cammisa-Parks et al. (6). Of these putative CS, two (CS “A” and CS “B”) were base-paired in the 5′ region within the first 45 nucleotides, unlike all other CS examined; the 3′ component of the third (CS “C”) commenced at nucleotide −471, nearly 200 bases upstream of all those described above (Table 1). However, other possible CS (now described as CS “D”) were base-paired at nucleotides 169 to 179 (5′) and 10563 to 10572 (−134 to −125 in 3′ end) as shown in Fig. 5, in locations similar to those in the CS of the mosquito-borne viruses, especially in the 3′ UTR (commencing in the region from −99 to −112 [Table 1]).

In all secondary structures of Flavivirus RNA generated by the M-fold program which showed base-pairing of the proposed CS, the upper half of the 3′-terminal stem-loop and the conserved pentanucleotide loop were retained. The latter is uniformly located for all species, viz., at −46 to −48 (mosquito borne), −49 (tick borne), or −45 (CFA) nucleotides from the 3′ terminus. However, the CFA pentanucleotide loop is changed at the fourth base (C instead of A). Table 1 summarizes the proposed CS and their relative locations within the nucleotide sequences of genomic RNA for the range of Flavivirus species for which data are available. There is remarkable uniformity among the nine mosquito-borne viruses. The conserved 5′ CS always commence 37 to 40 nucleotides downstream from the start of the initiation codon. The 3′ CS always commence 99 to 112 nucleotides before the 3′ terminus. The corresponding locations in CFA virus RNA that appear to best match the mosquito-borne viruses according to the M-fold program (Fig. 5) are newly defined CS “D” rather than CS “C” (6). However, the CS show no resemblance to the order of nucleotides in the mosquito-borne species. For the 5′ CS of the tick-borne species, the reference locations for CS “A,” as proposed by Mandl et al. (29), for both the TBE and POW viruses commence 18 to 20 nucleotides before the initiation codon, whereas those of the mosquito-borne viruses commence about 40 nucleotides downstream of this codon, as noted above. The location of the proposed 3′ CS of the tick-borne viruses appears to be anomalous; each of these is located within the lower half of the 3′-terminal conserved stem-loop predicted when the 3′ UTR is analyzed in isolation from the remainder of the genome (29, 37). In contrast, the newly proposed 3′ CS “B” for both viruses is located further upstream, as for the mosquito-borne viruses. For louping ill virus, the CS and their locations conform to those described above for the TBE and POW viruses (Table 1). Whether or not our proposed CS in RNA of the tick-borne viruses and the CFA virus (Fig. 5; Table 1) are essential for replication remains to be tested experimentally.

The ΔG values for the conserved base paired CS for the mosquito-borne viruses, as cited by Hahn et al. (20), increase to as much as −33 kcal when four to six base pairs upstream are included, but those for DEN-2 remain at −12 kcal. The ΔG values of CS for the other viruses in Table 1 are −22.9 and −24.2 kcal for CS “C” and CS “D,” respectively, of the CFA virus and −19.8 and −30.9 kcal for CS “A” and CS “B,” respectively, of tick-borne viruses. ΔG values for the five or six-base pairs in Table 1 preceding the mismatch or bulge region in CS “B” of tick-borne viruses are −19.2 or −24.0 kcal, respectively. These values compare favorably with those of the mosquito-borne viruses for stability of the CS.

Conclusions.

All previous analyses of the conformation and possible role of 5′- and 3′-terminal nucleotide sequences of a range of Flavivirus species defined a variety of stem-loop structures (37), including a pseudoknot formed about 90 nucleotides from the 3′ terminus (41). However, all these analyses examined the structure of each 5′- or 3′-terminal region in isolation, and hence the possible interactions or base-pairing between the proposed CS when covalently linked with flanking 5′ and 3′ sequences have not hitherto been examined, either by the M-fold program or in infectivity testing of genomes with mutated CS. Our results with the KUN replicon establish the essential role of both the 5′ and 3′ CS in replication. Other functions of the CS in addition to the role in replication proposed by Hahn et al. (20) may be postulated. Cyclization of genomic RNA during or immediately after formation of the RC on, e.g., the 3′-terminal loop may allow ribosomes involved in translation to complete their traverse of the genomic RNA and their subsequent release but prevent their reattachment at the 5′ terminus for reinitiation. Assuming that a short delay occurs during cyclization and assembly of the RC before its commencement of copying, the risk of collision between the ribosome and RC moving along the template towards each other would be eliminated. It was proposed previously that during the initial assembly of the RC on the 3′ UTR of the plus-strand RNA template, it is transported to the membrane site of replication by the affinity of hydrophobic regions of components of the RC (24). Such binding may provide a sequestered environment that prevents the reattachment of ribosomes when the base-pairing of the CS is disrupted during the copying of the RNA template. In this scenario, cyclization of the RNA template is required only for minus-strand RNA synthesis, which is a relatively infrequent event throughout infection compared to synthesis of plus-strand RNA. There is a continuing major need for genomic RNA to function early and late as mRNA for synthesis of components of the RC and of the structural proteins, respectively. Hence, the M-fold-program-predicted structures shown in Fig. 1, 2, and 5 cannot be representative of the total viral RNA population, but they may be essential for providing the appropriate template conformation for minus-strand RNA synthesis. The presumably rigid structure of the double-stranded RNA in RF would not allow cyclization to occur when RF is being converted to the replicative intermediate during the initiation of synthesis of progeny RNA plus strands (9, 10). Proutski et al. (37) suggested that the essential role of cyclization of the Flavivirus genome may be in virion packaging rather than in RNA replication. However, the latter role is strongly supported by our results with the KUN replicon RNA which has a deletion in the structural genes, and hence, effects on replication do not involve packaging.

We believe that the results obtained by mutation analysis with the KUN replicon unequivocally establish the essential requirement of complementary CS in the 5′ region and 3′ UTR for replication in vivo. Because of the conservation of these motifs, the results can be extrapolated to other mosquito-borne flaviviruses. Clearly the results obtained with the inactive pC17-5′mut and the pC17-3′mut RNAs show that a single 5′ or 3′ cyclization motif is inadequate for replication. Results with the compensatory mutant pC17-5′&3′mut, show that base pairing of the CS provides the essential element rather than the nucleotide sequences per se. The slow initial amplification of the double mutant pC17-5′&3′mut, may indicate that the wild-type sequence confers some early advantage in replication, but this is only transient. Further definition of the role of CS in Flavivirus RNA replication will be possible when efficient systems are established for in vitro assays of Flavivirus RNA synthesis using specific RNA templates and the purified RC.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grant no. 981442 from the National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia.

Footnotes

Publication no. 132 from the Sir Albert Sakzewski Virus Research Centre.

REFERENCES

- 1.Blackwell J L, Brinton M A. BHK cell proteins that bind to the 3′ stem-loop structure of the West Nile virus genome RNA. J Virol. 1995;69:5650–5658. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.9.5650-5658.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Blackwell J L, Brinton M A. Translation elongation factor-1 alpha interacts with the 3′ stem-loop region of West Nile virus genomic RNA. J Virol. 1997;71:6433–6444. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.9.6433-6444.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brinton M A, Dispoto J H. Sequence and secondary structure analysis of the 5′-terminal region of flavivirus genome RNA. Virology. 1988;162:290–299. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(88)90468-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brinton M A, Fernandez A V, Dispoto J H. The 3′-nucleotides of flavivirus genomic RNA form a conserved secondary structure. Virology. 1986;153:113–121. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(86)90012-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cahour A, Pletnev A, Vazielle-Falcoz M, Rosen L, Lai C J. Growth-restricted dengue virus mutants containing deletions in the 5′ noncoding region of the RNA genome. Virology. 1995;207:68–76. doi: 10.1006/viro.1995.1052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cammisa-Parks H, Cisar L A, Kane A, Stollar V. The complete nucleotide sequence of cell fusing agent (CFA): homology between the nonstructural proteins encoded by CFA and the nonstructural proteins encoded by arthropod-borne flaviviruses. Virology. 1992;189:511–524. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(92)90575-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Castle E, Leidner U, Nowak T, Wengler G. Primary structure of the West Nile flavivirus genome region coding for all nonstructural proteins. Virology. 1986;149:10–26. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(86)90082-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chen C-J, Kuo M-D, Chen L-J, Hsu S-L, Wang Y-M, Lin J-H. RNA-protein interactions: involvement of NS3, NS5, and 3′ noncoding regions of Japanese encephalitis virus genomic RNA. J Virol. 1997;71:3466–3473. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.5.3466-3473.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chu P W, Westaway E G. Characterization of Kunjin virus RNA-dependent RNA polymerase: reinitiation of synthesis in vitro. Virology. 1987;157:330–337. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(87)90275-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chu P W, Westaway E G. Molecular and ultrastructural analysis of heavy membrane fractions associated with the replication of Kunjin virus RNA. Arch Virol. 1992;125:177–191. doi: 10.1007/BF01309636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chu P W, Westaway E G. Replication strategy of Kunjin virus: evidence for recycling role of replicative form RNA as template in semiconservative and asymmetric replication. Virology. 1985;140:68–79. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(85)90446-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Coia G, Parker M D, Speight G, Byrne M E, Westaway E G. Nucleotide and complete amino acid sequences of Kunjin virus: definitive gene order and characteristics of the virus-specified proteins. J Gen Virol. 1988;69:1–21. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-69-1-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cui T, Sugrue R J, Xu Q, Lee A K, Chan Y C, Fu J. Recombinant dengue virus type 1 NS3 protein exhibits specific viral RNA binding and NTPase activity regulated by the NS5 protein. Virology. 1998;246:409–417. doi: 10.1006/viro.1998.9213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dalgarno L, Trent D W, Strauss J H, Rice C M. Partial nucleotide sequence of the Murray Valley encephalitis virus genome. Comparison of the encoded polypeptides with yellow fever virus structural and non-structural proteins. J Mol Biol. 1986;187:309–323. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(86)90435-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Deubel V, Kinney R M, Trent D W. Nucleotide sequence and deduced amino acid sequence of the nonstructural proteins of dengue type 2 virus, Jamaica genotype: comparative analysis of the full-length genome. Virology. 1988;165:234–244. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(88)90677-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fu J, Tan B H, Yap E H, Chan Y C, Tan Y H. Full-length cDNA sequence of dengue type 1 virus (Singapore strain S275/90) Virology. 1992;188:953–958. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(92)90560-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Grange T, Bouloy M, Girard M. Stable secondary structures at the 3′-end of the genome of yellow fever virus (17 D vaccine strain) FEBS Lett. 1985;188:159–163. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(85)80895-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gritsun T S, Venugopal K, Zanotto P M, Mikhailov M V, Sall A A, Holmes E C, Polkinghorne I, Frolova T V, Pogodina V V, Lashkevich V A, Gould E A. Complete sequence of two tick-borne flaviviruses isolated from Siberia and the UK: analysis and significance of the 5′ and 3′-UTRs. Virus Res. 1997;49:27–39. doi: 10.1016/s0168-1702(97)01451-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Guyatt K J, Westaway E G, Khromykh A A. Expression and purification of enzymatically active recombinant RNA-dependent RNA polymerase (NS5) of the flavivirus Kunjin. J Virol Methods. 2001;92:37–44. doi: 10.1016/s0166-0934(00)00270-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hahn C S, Hahn Y S, Rice C M, Lee E, Dalgarno L, Strauss E G, Strauss J H. Conserved elements in the 3′ untranslated region of flavivirus RNAs and potential cyclization sequences. J Mol Biol. 1987;198:33–41. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(87)90455-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Heinz F X, Collet M S, Purcell R H, Gould E A, Howard C R, Houghton M, Moormann R J M, Rice C M, Thiel H-J. Family Flaviviridae. In: van Regenmortel M H V, Fauquet C M, Bishop D H L, et al., editors. Virus taxonomy; classification and nomenclature of viruses. Seventh report of the International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses. London, England: Academic Press; 2000. pp. 859–879. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Khromykh A A, Kenney M T, Westaway E G. trans-complementation of flavivirus RNA polymerase gene NS5 by using Kunjin virus replicon-expressing BHK cells. J Virol. 1998;72:7270–7279. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.9.7270-7279.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Khromykh A A, Sedlak P L, Guyatt K J, Hall R A, Westaway E G. Efficient trans-complementation of the flavivirus Kunjin NS5 protein but not of the NS1 protein requires its coexpression with other components of the viral replicase. J Virol. 1999;73:10272–10280. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.12.10272-10280.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Khromykh A A, Sedlak P L, Westaway E G. trans-complementation analysis of the flavivirus Kunjin ns5 gene reveals an essential role for translation of its N-terminal half in RNA replication. J Virol. 1999;73:9247–9255. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.11.9247-9255.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Khromykh A A, Westaway E G. Completion of Kunjin virus RNA sequence and recovery of an infectious RNA transcribed from stably cloned full-length cDNA. J Virol. 1994;68:4580–4588. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.7.4580-4588.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Khromykh A A, Westaway E G. Subgenomic replicons of the flavivirus Kunjin: construction and applications. J Virol. 1997;71:1497–1505. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.2.1497-1505.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lee E, Fernon C, Simpson R, Weir R C, Rice C M, Dalgarno L. Sequence of the 3′ half of the Murray Valley encephalitis virus genome and mapping of the nonstructural proteins NS1, NS3, and NS5. Virus Genes. 1990;4:197–213. doi: 10.1007/BF00265630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mackenzie J M, Khromykh A A, Jones M K, Westaway E G. Subcellular localization and some biochemical properties of the flavivirus Kunjin nonstructural proteins NS2A and NS4A. Virology. 1998;245:203–215. doi: 10.1006/viro.1998.9156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mandl C W, Holzmann H, Kunz C, Heinz F X. Complete genomic sequence of Powassan virus: evaluation of genetic elements in tick-borne versus mosquito-borne flaviviruses. Virology. 1993;194:173–184. doi: 10.1006/viro.1993.1247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mandl C W, Holzmann H, Meixner T, Rauscher S, Stadler P F, Allison S L, Heinz F X. Spontaneous and engineered deletions in the 3′ noncoding region of tick-borne encephalitis virus: construction of highly attenuated mutants of a flavivirus. J Virol. 1998;72:2132–2140. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.3.2132-2140.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mathews D H, Sabina J, Zuker M, Turner D H. Expanded sequence dependence of thermodynamic parameters improves prediction of RNA secondary structure. J Mol Biol. 1999;288:911–940. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1999.2700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Men R, Bray M, Clark D, Chanock R M, Lai C-J. Dengue type 4 virus mutants containing deletions in the 3′ noncoding region of the RNA genome: analysis of growth restriction in cell culture and altered viremia pattern and immunogenicity in rhesus monkeys. J Virol. 1996;70:3930–3937. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.6.3930-3937.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Osatomi K, Sumiyoshi H. Complete nucleotide sequence of dengue type 3 virus genome RNA. Virology. 1990;176:643–647. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(90)90037-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Palmenberg A C, Sgro J-Y. Topological organization of picornaviral genomes: statistical prediction of RNA structural signals. Semin Virol. 1997;8:231–241. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pletnev A G, Yamshchikov V F, Blinov V M. Nucleotide sequence of the genome and complete amino acid sequence of the polyprotein of tick-borne encephalitis virus. Virology. 1990;174:250–263. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(90)90073-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Proutski V, Gaunt M W, Gould E A, Holmes E C. Secondary structure of the 3′-untranslated region of yellow fever virus: implications for virulence, attenuation and vaccine development. J Gen Virol. 1997;78:1543–1549. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-78-7-1543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Proutski V, Gould E A, Holmes E C. Secondary structure of the 3′ untranslated region of flaviviruses: similarities and differences. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25:1194–1202. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.6.1194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rauscher S, Flamm C, Mandl C W, Heinz F X, Stadler P F. Secondary structure of the 3′-noncoding region of flavivirus genomes: comparative analysis of base pairing probabilities. RNA. 1997;3:779–791. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rice C M. Flaviviridae: the viruses and their replication. In: Fields B N, Knipe D M, Howley P M, et al., editors. Fields virology. 3rd ed. Vol. 1. Philadelphia, Pa: Lippincott-Raven Publishers; 1996. pp. 931–960. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rice C M, Lenches E M, Eddy S R, Shin S J, Sheets R L, Strauss J H. Nucleotide sequence of yellow fever virus: implications for flavivirus gene expression and evolution. Science. 1985;229:726–733. doi: 10.1126/science.4023707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Shi P Y, Brinton M A, Veal J M, Zhong Y Y, Wilson W D. Evidence for the existence of a pseudoknot structure at the 3′ terminus of the flavivirus genomic RNA. Biochemistry. 1996;35:4222–4230. doi: 10.1021/bi952398v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Shi P Y, Sklyarevskaya T, Kebbekus P, Brinton M, Wilson W D. Analysis of the structure and folding of the 3′ genomic RNA of flaviviruses. Nucleic Acids Symp Ser. 1997;36:52–55. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Steffens S, Thiel H J, Behrens S E. The RNA-dependent RNA polymerases of different members of the family Flaviviridae exhibit similar properties in vitro. J Gen Virol. 1999;80:2583–2590. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-80-10-2583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Stollar V, Thomas V L. An agent in the Aedes aegypti cell line (Peleg) which causes fusion of Aedes albopictus cells. Virology. 1975;64:367–377. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(75)90113-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sumiyoshi H, Mori C, Fuke I, Morita K, Kuhara S, Kondou J, Kikuchi Y, Nagamatu H, Igarashi A. Complete nucleotide sequence of the Japanese encephalitis virus genome RNA. Virology. 1987;161:497–510. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(87)90144-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Takegami T, Washizu M, Yasui K. Nucleotide sequence at the 3′ end of Japanese encephalitis virus genomic RNA. Virology. 1986;152:483–486. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(86)90152-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Tan B H, Fu J, Sugrue R J, Yap E H, Chan Y C, Tan Y H. Recombinant dengue type 1 virus NS5 protein expressed in Escherichia coli exhibits RNA-dependent RNA polymerase activity. Virology. 1996;216:317–325. doi: 10.1006/viro.1996.0067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wallner G, Mandl C W, Kunz C, Heinz F X. The flavivirus 3′-noncoding region: extensive size heterogeneity independent of evolutionary relationships among strains of tick-borne encephalitis virus. Virology. 1995;213:169–178. doi: 10.1006/viro.1995.1557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wengler G, Castle E. Analysis of structural properties which possibly are characteristic for the 3′-terminal sequence of the genome RNA of flaviviruses. J Gen Virol. 1986;67:1183–1188. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-67-6-1183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Westaway E G, Khromykh A A, Mackenzie J M. Nascent flavivirus RNA colocalized in situ with double-stranded RNA in stable replication complexes. Virology. 1999;258:108–117. doi: 10.1006/viro.1999.9683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Westaway E G, Mackenzie J M, Kenney M T, Jones M K, Khromykh A A. Ultrastructure of Kunjin virus-infected cells: colocalization of NS1 and NS3 with double-stranded RNA, and of NS2B with NS3, in virus-induced membrane structures. J Virol. 1997;71:6650–6661. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.9.6650-6661.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.You S, Padmanabhan R. A novel in vitro replication system for Dengue virus. Initiation of RNA synthesis at the 3′-end of exogenous viral RNA templates requires 5′- and 3′-terminal complementary sequence motifs of the viral RNA. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:33714–33722. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.47.33714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Zeng L, Falgout B, Markoff L. Identification of specific nucleotide sequences within the conserved 3′-SL in the dengue type 2 virus genome required for replication. J Virol. 1998;72:7510–7522. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.9.7510-7522.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Zhao B, Mackow E, Buckler-White A, Markoff L, Chanock R M, Lai C J, Makino Y. Cloning full-length dengue type 4 viral DNA sequences: analysis of genes coding for structural proteins. Virology. 1986;155:77–88. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(86)90169-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Zuker M, Mathews D H, Turner D H. Algorithms and thermodynamics for RNA secondary structure prediction: a practical guide. In: Barciszewski J, Clark B F C, editors. RNA biochemistry and biotechnology. Amsterdam, The Netherlands: Kluwer Academic Publishers; 1999. pp. 11–43. [Google Scholar]