Abstract

For high-risk patients with complex aortic aneurysms and post-dissection aneurysms, fenestrated and branched endovascular aortic repair (F/BEVAR) offers minimally invasive options customized to each individual’s anatomy. Company-manufactured devices or physician-modified endovascular grafts performed under the purview of an investigational device exemption are two United States Food and Drug Administration-approved avenues to perform fenestrated and branched endovascular aortic repair. This case report describes a creative use of physician-modified endograft to salvage renal function in a solitary kidney with a near immediate bifurcation of the renal artery in a patient with post-dissection extent II thoracoabdominal aortic aneurysm. In our patient, the immediate bifurcation (2 mm distal to the common left renal artery orifice) of the left renal artery in the setting of a known long-standing occlusion of a remotely placed right renal stent presented a clinical and technical challenge to maintaining this patient’s kidney function without sacrificing a significant portion of his remaining solitary kidney. Additionally, each branch was sizeable (5 and 7 mm), perfusing the cranial and caudal half of the kidney, respectively. Early bifurcation of renal arteries often results in sacrifice of the smaller branch to obtain adequate target vessel seal. Although some analyses have shown no change in glomerular filtration rate from coverage of accessory renal arteries, more recent studies have indicated clinically significant drops in both glomerular filtration rate and kidney length at 2-year follow-up. Herein, we describe use of a combination of an inner and external branch modification to stent both branches to preserve renal parenchyma and function. The patient has provided written informed consent for publication of this case report and their associated imaging studies.

Keywords: Physician modified endograft (PMEG), Renal preservation, Solitary kidney, Early bifurcation

A 53-year-old man with a post dissection extent II thoracoabdominal aortic aneurysm with multiple previous aortic interventions presented with degeneration of his paravisceral aorta and bilateral common iliac arteries to 6 cm, 5.2 cm, and 4.4 cm, respectively. His previous surgical interventions included ascending aortic aneurysm repair for type A aortic dissection, followed by a carotid subclavian bypass and thoracic endovascular aortic repair (EVAR). A right renal stent was placed at the time, presumably for malperfusion. This stent has since occluded, and the right kidney was atrophic, measuring only 4 cm. The patient subsequently underwent an attempted open descending thoracic repair over 10 years prior to his current presentation. However, extensive adhesions and hostile abdomen precluded completion of repair, leaving the visceral aortic segment untreated at that time. This has since resulted in further aneurysmal degeneration. Pertinent medical history includes medically controlled chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, and chronic kidney disease stage 3 with a glomular filtration rate (GFR) of 45 mL/min.

At the time of presentation, he underwent a high-resolution computed tomography angiography (CTA), which demonstrated aneurysmal degeneration of his untreated distal descending thoracic aorta involving the viscero-renal segment as well as bilateral common iliac artery aneurysms. The CTA was imported into Aquarius iNuition software (TeraRecon), to create a centerline of flow.

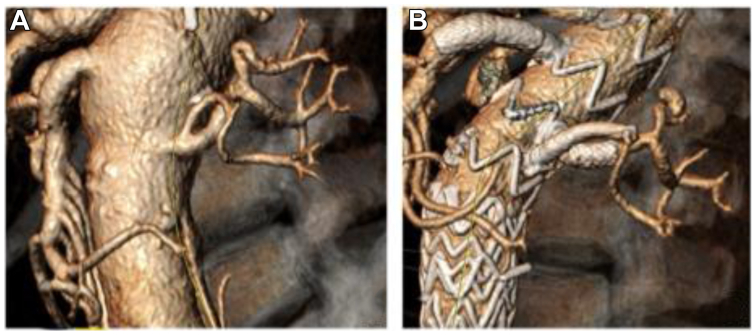

This was used to plan a three-stage repair, given the complexity of his anatomy and as a strategy for spinal cord protection. A thoracic endovascular aortic repair piece was extended to the level of the celiac followed by planned fenestrated and branched endovascular aortic repair (F/BEVAR) under the purview of the United States Food and Drug Administration-approved Investigational Device Exemption (G190192). The device modification was customized to accommodate the early branching of the left renal artery to preserve both branches (5 and 7 mm) (Fig 1, A and B). A 38 × 34 × 167 mm Zenith Alpha stent graft (Cook Medical) was modified. A fenestration was created for the celiac trunk, given the proximity of the stent graft to the target vessel, and branch was created for the superior mesenteric artery. To preserve both the renal branches, a combination of a caudally directed inner branch and a cranially directed external branch were created (Fig 1, B; Fig 2).

Fig 1.

A, Early branching of the left renal artery. B, Left renal artery post-stent implantation.

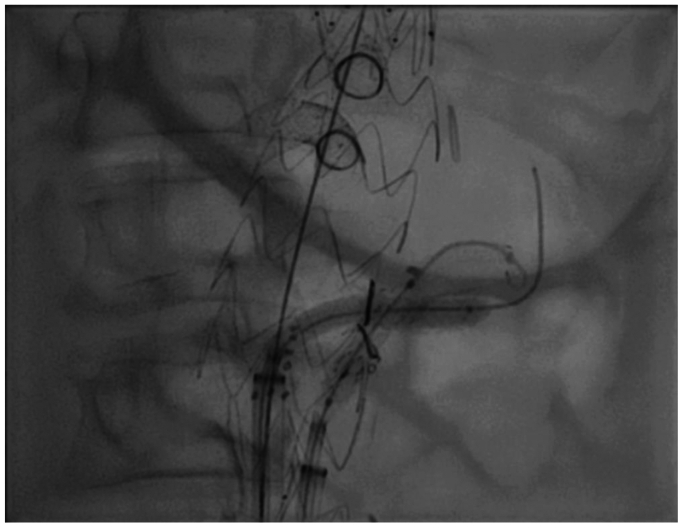

Fig 2.

Modified endograft with caudally directed inner branch and a cranially directed external branch.

Device design

To construct the inner branch, a Viabahn (W.L. Gore and Associates) self-expanding covered stent was deployed through an anatomically specific fenestration and tacked longitudinally to the aortic stent graft. The inner branch was then reinforced to the fenestration circumferentially using a platinum wire and a running 5-0 Ethibond suture. Radiopaque gold markers were placed at the outlet of the inner branch. The external branch Viabahn stent graft (W. L. Gore and Associates) was cut oblong and sutured to the fenestration created caudal to the fenestration of the inner branch with adequate fabric to allow for flaring. Using platinum wire and 5-0 Ethibond suture, the branch is secured, directed cranially. Both the inner and external branch were kept approximately 1.5 cm long, to allow adequate overlap with the mating branch stent. Gold markers were sutured at the origin and at the distal end of the branch to allow for visualization under fluoroscopy (Fig 2). The graft was constrained and re-sheathed.

Operative technique

It is the authors’ practice to use CT fusion and intravascular ultrasound to confirm device orientation and positioning prior to deployment. Total femoral approach was utilized for this procedure, with a left-sided 18 French Gore Dryseal (W.L. Gore and Associates) sheath for physician-modified endograft device delivery and a right-sided 14 French Gore Dryseal (W.L. Gore and Associates) sheath for target vessel cannulation and stenting. A TourGuide steerable sheath (Medtronic) was used along with a stiff angled glidewire (Terumo) for initial cannulation and exchanged for a Rosen (Cook Medical) wire in preparation for target vessel stent delivery. After all branches and their respective target vessels were cannulated sequentially, the graft was deployed completely and ballooned to ensure apposition to the aortic wall across the seal zones. This was followed by sequential target vessel stenting. The caudally directed larger branch was stented with a 7-mm VBX stent (Gore Medical). The cranially directed smaller branch was first stented with a 5-mm Viabahn stent (Gore Medical) and then a 5-mm VBX stent (Gore Medical) proximally. At the junction of the two VBX stents (Gore Medical), balloon angioplasty was then performed in a kissing fashion to ensure adequate luminal opening in both branches without compression. There was excellent opacification of the entirety of the renal parenchyma on digital subtraction angiography (Figs 3 and 4). Intravascular ultrasound was then used to ensure adequate luminal patency and circumference. An EVAR was then performed in a conventional fashion using Gore Excluder, with bilateral 20 mm iliac limbs as a set up for final stage with bilateral iliac branch endoprosthesis (Gore Medical). Completion angiogram demonstrated robust filling of the celiac trunk, superior mesenteric artery, and both renal branch stents. The subsequent iliac branch operations were performed 2 weeks after the FEVAR as planned for staging.

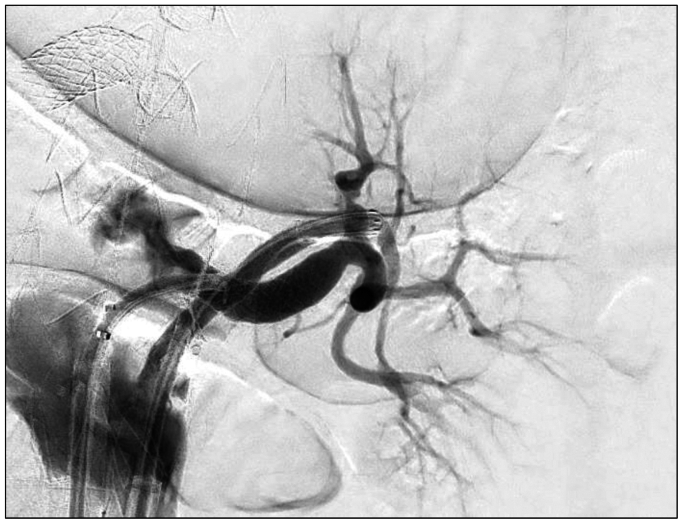

Fig 3.

Kissing balloon angioplasty of both left renal artery branches.

Fig 4.

Complete left renal parenchymal opacification post-stenting.

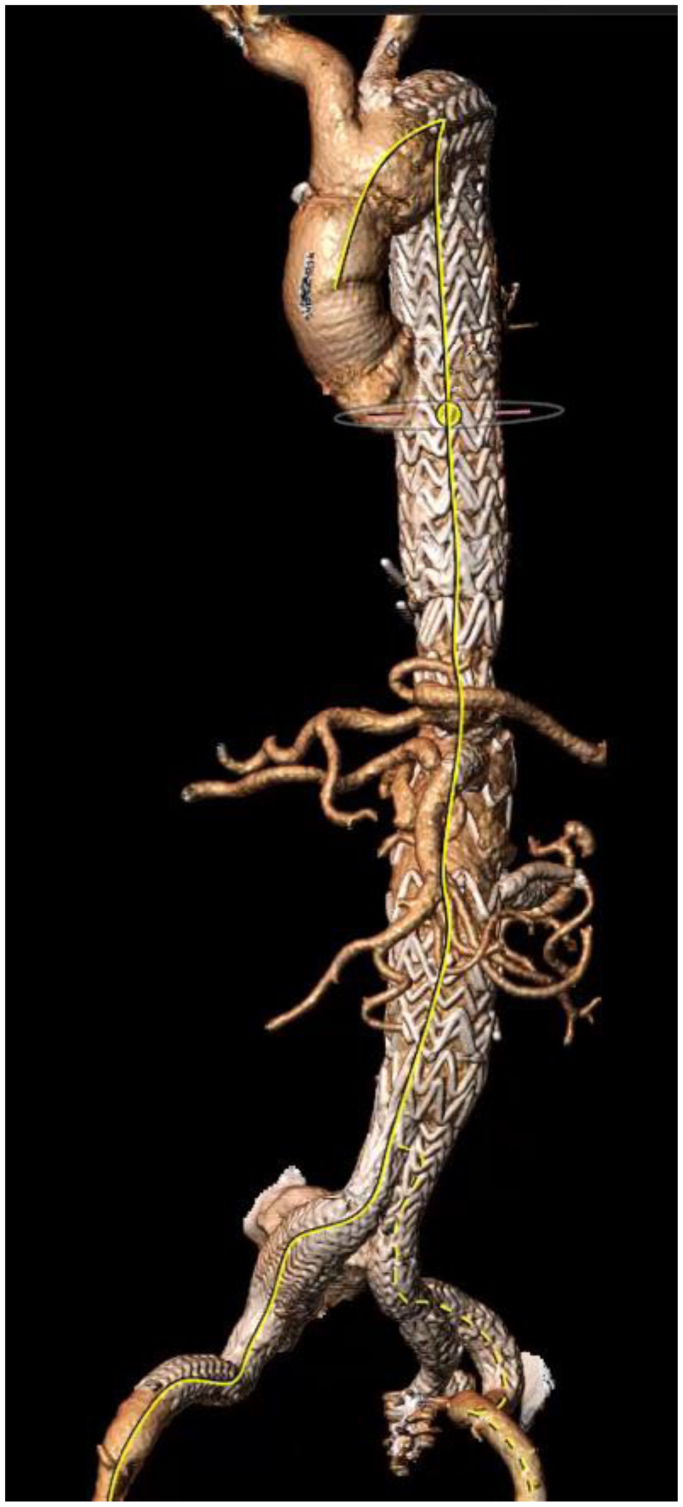

Postoperative CTA at 1 year demonstrates widely patent branches with excellent architectural integrity and no evidence of any kinks, fractures, or stenosis (Fig 5). His kidney function remains preserved with GFR ranging from 39 to 44 mL/min at chronic kidney disease stage 3.

Fig 5.

Postoperative computed tomography reconstruction demonstrating widely patent branches.

Discussion

Coverage of accessory renal arteries and branches of major renal branches during EVAR has been demonstrated to lead to deterioration of renal function in the short- and long-term after the initial coverage.1,2 Torrealba et al examined patients undergoing F/BEVAR for similar outcomes, but also included kidney length. Their analysis demonstrated an increase in renal function deterioration at 2 years and a decrease in kidney length in patients that had covered accessory renal arteries.3 Loss of renal function and worsening GFR directly correlates with increase in mortality after F/BEVAR.4 Another study by Tenorio et al confirmed that intentional coverage of accessory renal arteries among F/BEVAR patients led to more kidney infarcts and loss of >25% of kidney parenchyma volume, contributing to a three-fold higher incidence of acute kidney injury (AKI).1 Among patients who develop renal ischemia with or without AKI, silent inflammatory changes may trigger fibrosis of the kidney parenchyma, leading to permanent structural and functional damage.5 The general consensus is to preserve vessels that are at least 4 mm in diameter.6

These data emphasize that preservation of renal branches is critical to preserve renal function. Therefore, loss of renal branches, whether accessory or early bifurcation branches, should not be considered benign, and every option should be considered to incorporate them whenever technically feasible.

Multiple anatomic variances may be noted in renal arteries, posing challenges in their preservation specially when considering EVARs. These include separate origins but with close proximity of branches to each other, take off of renal arteries from narrow aortic lumens, or in angulated segments of the aorta, and as noted in our patient, early bifurcation of the main renal artery. Traditional alternatives have been sacrificing the accessory branch, or the smaller of the two branches in cases of immediate bifurcation to ensure adequate target vessel seal, or consideration of surgical renal debranching, which has its own inherent physiologic stress to these high-risk patients, higher rates of AKI, and risk of dialysis. Hybrid repair with surgical debranching was considered prohibitive in our patient, given previous open repair with hostile abdomen. Therefore, use of an inner branch along with an external branch and use of kissing deployment of target artery stents across the crossing point was used to optimize renal parenchymal preservation fed by both branches of this solitary kidney. Inner branches have been an instrumental add-on to the armamentarium of modifications designed to specifically address some challenging anatomic situations as described above. They allow for creation of a stagger and prevent shuttering within aortic lumen for branches in close proximity and can be used in combination with fenestrations or external branches, as in our case, to create effective seal while maintaining precision in deployment and without compromise to the bridging stents. Initial reports of use of inner branches have shown promising results.3,4 This report emphasizes a combination of inner and external branches to successfully preserve the immediate branching of a solitary renal artery.

Our patient, given his decreased GFR and his solitary kidney, needed every bit of renal parenchyma we could preserve. He had several advantageous anatomic factors that made this unique configuration of the physician-modified endograft to be technically feasible. First, the ostium of the renal artery, although short, was wide enough to accommodate two VBX stents (Gore Medical). Second, the diameter of the aorta at the level of the left renal (4.4 cm) was wide enough to allow construction of an external branch; however, the combination of an inner branch with a fenestration could have been a reasonable alternative if the aortic lumen was small. Third, the renal branches themselves were large enough (>4 mm) to be stented. The construct design is key to ensuring a seal. Creation of two fenestrations would have been fraught without enough aortic graft fabric between them, causing shuttering and inability to adequately flare the stents, increasing the risk of a type IIIC endoleak. Creating two branches, one inner and one outer, added a landing zone to create a durable seal.

Conclusion

Preservation of major renal branches in a renal artery with an early bifurcation can be accomplished with careful planning, endograft modification customized to the patient’s individual anatomy, and precise deployment. Interval surveillance imaging is necessary along with long-term follow-up to ensure durability.

Disclores

None.

Footnotes

The editors and reviewers of this article have no relevant financial relationships to disclose per the Journal policy that requires reviewers to decline review of any manuscript for which they may have a conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Tenorio E.R., Karkkainen J.M., Marcondes G.B., et al. Impact of intentional accessory renal artery coverage on renal outcomes after fenestrated-branched endovascular aortic repair. J Vasc Surg. 2021;73:805–818.e2. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2020.06.123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Greenberg J.I., Dorsey C., Dalman R.L., et al. Long-term results after accessory renal artery coverage during endovascular aortic aneurysm repair. J Vasc Surg. 2012;56:291–296. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2012.01.049. discussion 6-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Torrealba J.I., Kolbel T., Rohlffs F., Heidemann F., Spanos K., Panuccio G. The preservation of accessory renal arteries should be considered the treatment of choice in complex endovascular aortic repair. J Vasc Surg. 2022;76:656–662. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2022.02.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dossabhoy S.S., Simons J.P., Crawford A.S., et al. Impact of acute kidney injury on long-term outcomes after fenestrated and branched endovascular aortic aneurysm repair. J Vasc Surg. 2020;72:55–65.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2019.09.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hodgkins K.S., Schnaper H.W. Tubulointerstitial injury and the progression of chronic kidney disease. Pediatr Nephrol. 2012;27:901–909. doi: 10.1007/s00467-011-1992-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Karkkainen J.M., Tenorio E.R., Pather K., et al. Outcomes of small renal artery targets in patients treated by fenestrated-branched endovascular aortic repair. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2020;59:910–917. doi: 10.1016/j.ejvs.2020.02.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]