Abstract

Heterotrophic nitrification remains a mystery for decades. It has been commonly hypothesized that heterotrophic nitrifiers oxidize ammonia to hydroxylamine and then to nitrite in a way similar to autotrophic AOA and AOB. Recently, heterotrophic nitrifiers from Alcaligenes were found to oxidize ammonia to hydroxylamine and then to N2 (“dirammox”, direct ammonia oxidation) by the gene cluster dnfABC with a yet-to-be-reported mechanism. The role of a potential glutamine amidotransferase DnfC clues the heterotrophic ammonia oxidation might involving in glutamine. Here, we found Alcaligenes faecalis JQ135 could oxidize amino acids besides ammonia. We discovered that glutamine is an intermediate of the dirammox pathway and the glutamine synthetase gene glnA is essential for both A. faecalis JQ135 and the Escherichia coli cells harboring dnfABC gene cluster to oxidize amino acids and ammonia. Our study expands understanding of heterotrophic nitrifiers and challenges the classical paradigm of heterotrophic nitrification.

Keywords: Heterotrophic nitrification, Alcaligenes faecalis, Heterotrophic ammonia oxidation, dirammox, dnfABC

Introduction

Microbial ammonia oxidation plays a key role in the biogeochemical nitrogen cycle. Two ammonia oxidation pathways in chemolithotrophs have been extensively studied, i.e., nitrification that is usually referred as the oxidation of ammonia to nitrite and nitrate via the intermediate hydroxylamine, and anammox that is referred as the oxidation of ammonia using nitrite as the electron acceptor to generate dinitrogen gas [1–4]. Heterotrophic nitrification, the oxidation of ammonia and any other reduced nitrogenous compounds in heterotrophs has been discovered for over a century, occurs widely across Proteobacteria, Bacteroidetes, Firmicutes, Actinobacteria, and fungi, and yet remains a mystery in the nitrogen cycle [5–10]. Most heterotrophic nitrifiers were observed to produce hydroxylamine, nitrite, and/or nitrate, mirroring the nitrification process in ammonia-oxidizing archaea and bacteria (AOA and AOB), but they cannot obtain energy to fix carbon dioxide from this process as AOA and AOB can [11–16]. Although the accumulations of nitrite/nitrate were limited, the productions of N2 and N2O were confirmed. Additionally, it was discovered that the majority of heterotrophic nitrifiers possess the complete set of enzymes necessary for a denitrification pathway, enabling the conversion of nitrite or nitrate to N2. Therefore, it was proposed that heterotrophic nitrifiers first oxidized ammonia to nitrite/nitrate via the heterotrophic nitrification pathway and then reduced nitrite/nitrate to gas products under aerobic conditions [14, 17]. Productions of hydroxylamine and nitrite were also observed when some heterotrophic nitrifiers were cultured with organic nitrogenous compounds [12, 18–24]. These differences indeed suggested that the oxidation of ammonia in heterotrophs and autotrophs may recruit different enzymes, intermediates, pathways, and mechanisms.

Alcaligenes has attracted significant attention in wastewater treatment for its superior nitrogen removal efficiency compared to autotrophs. It is known for its highly active heterotrophic nitrification, capable of oxidizing ammonia, hydroxylamine, and pyruvic oxime, and possesses all the enzymes required for denitrification, despite not encoding known AMO and HAO enzymes [7, 16, 23, 25–32]. Recently, Alcaligenes species, including Alcaligenes ammonioxydans HO-1 and A. faecalis JQ135, were found to perform direct ammonia oxidation (“dirammox”) which contributed to almost all of the N2 production (about half of the initial ammonium amounts) of Alcaligenes cells under aerobic conditions. This process involves oxidization of ammonia to hydroxylamine and then directly to N2 via a gene cluster dnfABC in the presence of organic carbon sources. The enzyme DnfA was predicted as a di-iron oxidase, related to ammonia oxidation, and also identified as the oxidase responsible for oxidizing hydroxylamine to N2 with the assistance of an electron shuttle protein DnfB [32–34]. Actually, the DnfA homologs, CmlI and AurF, could oxidize the amino group of amines to the nitro group via their diiron centers [35, 36], agreeing with the potential dual role of DnfA in ammonia (or amine) oxidation and hydroxylamine oxidation. DnfC was predicted as a potential glutamine amidotransferase. Miao and colleagues suggested that DnfABC oxidized glutamine to dinitrogen gas in vitro, though lacking direct biochemical evidence to support the oxidation of glutamine by DnfA [37]. A recent study also proposed that A. faecalis produced hydroxylamine from an unidentified organic intermediate [38]. Nevertheless, those findings clued that heterotrophic nitrification by Alcaligenes might recruit a different pathway from those in AOA and AOB.

Here, we investigated whether the natural heterotrophic nitrifier A. faecalis JQ135 and the engineered heterotrophic nitrifier E. coli cells harboring dnfABC could oxidize amino acids through the dirammox pathway and identified the possible common intermediate in the ammonia and amine oxidation by the dirammox pathway. Our findings reveal that heterotrophic nitrifier A. faecalis JQ135 can oxidize ammonia and amines using glutamine as a shared intermediate. This discovery challenges the traditional paradigm regarding heterotrophic nitrification.

Materials and methods

Strains, plasmids, media, and cultivation

All bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study are listed in Supplementary Table 1. The construction of plasmid pBAD-dnfABC, preparation of media and cultivation of A. faecalis JQ135 and E. coli cells followed the established protocols as previously described [32, 33]. The HNM media contains (per liter) 0.66 g (NH4)2SO4, 4.72 g sodium succinate, 0.50 g KH2PO4, 1.25 g Na2HPO4·12H2O, 0.20 g MgSO4·7H2O, 2.00 ml trace element solution at pH 7.5–8.0. The trace element solution contains (per liter) 57.10 g EDTA·2Na, 3.90 g ZnSO4·7H2O, 7.00 g CaCl2·2H2O, 1.00 g MnCl2·4H2O, 5.00 g FeSO4·7H2O, 1.10 g (NH4)6Mo7O24·4H2O, 1.60 g CuSO4·5H2O, 1.60 g CoCl2·6H2O at pH 6.0. In the modified HNM media, 10 mM of various amino acids were utilized as the nitrogen source instead of ammonia.

Oxidation of organic nitrogen sources

For growth-dependent assays, A. faecalis JQ135 was cultivated in HNM medium or modified HNM medium. The flasks were incubated at 30°C with a shaking speed of 160 rpm and an inoculation amount of 1% (v/v). Samples were harvested periodically to measure OD600 and the accumulation of hydroxylamine.

For the whole cell transformation (growth-independent) assays, JQ135 and JQ135ΔglnA::glnA cells were cultured overnight with HNM media, harvested, and transferred into the media containing different nitrogen sources with a final OD600 of 1. JQ135ΔglnA cells were cultured with HNM where ammonia was replaced by 10 mM glutamine and subjected on the assays. E. coli and variant cells harboring pBAD-dnfABC were cultured in LB medium, induced by arabinose, harvested, and subsequently transferred into the media with a final OD600 of 1, as previously described [32].

Gene deletion and complementation

The genetic deletion mutant JQ135ΔglnA and the complementary strain JQ135ΔglnA::glnAAfe were constructed via a two-step homologous recombination method as previously described [33]. The single gene knockout E. coli mutants were derived from E. coli BW25113 strain, as a part of Keio collection obtained from the National Institute of Genetics, Japan [39]. The complementary strain E.coliΔglnA::glnAEco was constructed as described in JQ135. All primers used in this study are listed in Supplementary Table 2.

Analytical methods

Bacterial growth was monitored by spectrophotometrically measured at 600 nm. Quantitative detections of hydroxylamine were measured by the method as previously described [32, 40]. The expression of DnfA/DnfC in JQ135 was assessed by western blotting when the yield of hydroxylamine reached its highest or the cells entered the logarithmic phase. The sample cells used for western blotting were harvest and their concentrations were adjusted to OD600 of 1.0 before lysis. 15N2 was determined by GC–MS as previously described [32].

Results

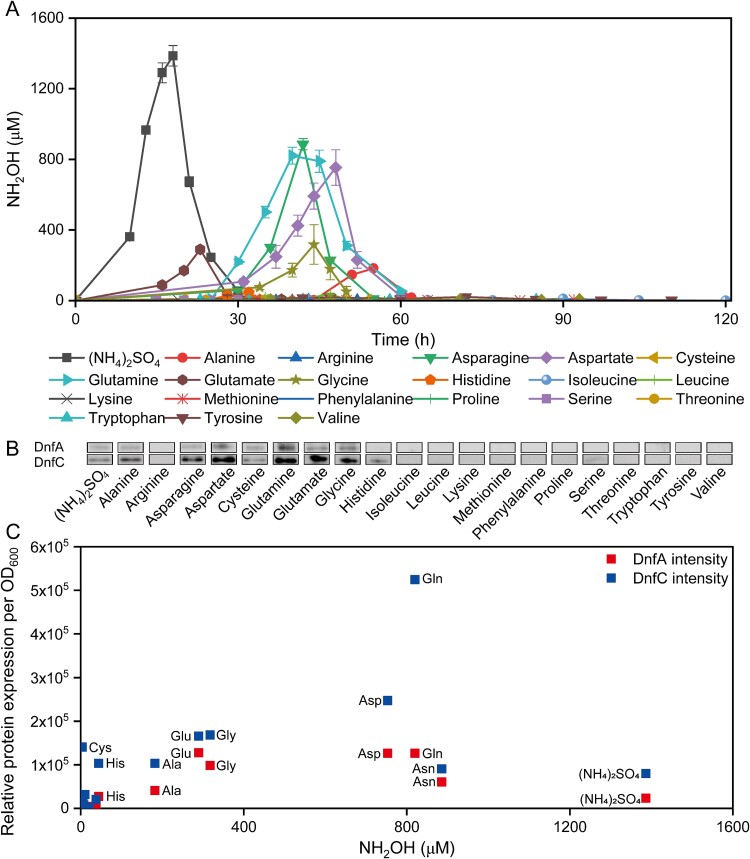

Amino acids could be oxidized to hydroxylamine by A. faecalis JQ135

To investigate the potential nitrogen sources that could be oxidized to hydroxylamine by the dirammox pathway, A. faecalis JQ135 was cultured with modified HNM media where the nitrogen source (ammonia) was substituted with 20 different amino acids. JQ135 cells exhibited growth in these media, reaching a maximum OD600 of ~0.8–1.2 within 26–100 h (Fig. 1A, Supplementary Fig. 1). Significant hydroxylamine accumulations, with a maximum of ~800 μM, were observed in media containing asparagine (885.8 ± 31.8 μM at 42 h), aspartate (753.3 ± 100.5 μM at 48 h), or glutamine (820.4 ± 48.2 μM at 40 h), respectively, which were comparable to that in medium containing ammonia (1386.7 ± 58.6 μM at 18 h) (Fig. 1A, Supplementary Fig. 1). Moderate level of hydroxylamine accumulations, ~200–300 μM, were observed in media containing alanine (182.5 ± 5.4 μM at 55 h), glutamate (289.6 ± 10.9 μM at 23 h) or glycine (317.5 ± 112.0 μM at 44 h). Limited hydroxylamine accumulations were observed in media containing histidine (44.6 ± 11.3 μM at 32 h) or leucine (37.9 ± 3.6 μM at 47 h) (Fig. 1A, Supplementary Fig. 1). No significant hydroxylamine accumulation was observed in media containing other amino acids (Fig. 1A, Supplementary Fig. 1). Since hydroxylamine is only an intermediate, no hydroxylamine accumulation for those amino acids did not exclude the possibility that JQ135 oxidized those amino acids to hydroxylamine and then quickly to N2. Further experimental evidence demonstrated that the deletion of dnfA abolished the ability to produce hydroxylamine when utilizing different amino acids (Supplementary Fig. 2A). Therefore, we conclude that JQ135 oxidizes amino acids to hydroxylamine through the dirammox pathway.

Figure 1.

A. faecalis JQ135 cells oxidize amino acids besides ammonia in growth-dependent assays. (A, B) hydroxylamine accumulation curves (A) and expressions of DnfA/DnfC (B) in JQ135 cells cultured with ammonia or amino acids. (C) the plot between the hydroxylamine accumulation and the relative expression levels of DnfA/DnfC under various nitrogen sources. The data are represented as the mean ± s.d. of biological triplicates.

The expression levels of DnfA/DnfC in different samples were assayed by western blotting, with bacterial samples collected at the point of maximal hydroxylamine accumulation for those amino acids that yielded hydroxylamine or at the time when the maximum OD600 was reached for those amino acids that did not yield hydroxylamine (Fig. 1B). Cells cultured with alanine, asparagine, aspartate, glutamine, glutamate, or glycine exhibited comparable or higher expression levels of DnfA/DnfC compared to cells cultured with ammonia, indicating significant hydroxylamine accumulation associated with these amino acids. In contrast, cells cultured with histidine displayed similar expression levels of DnfA/DnfC as those with ammonia despite limited hydroxylamine accumulation. Cells cultured with cysteine or serine exhibited significant expressions of DnfA and/or DnfC despite not producing hydroxylamine. The other amino acids neither induced the expression of DnfA/DnfC nor were oxidized to hydroxylamine (Fig. 1B). These findings indicate that the expression of DnfA/DnfC is a prerequisite for hydroxylamine accumulation. However, a positive correlation between hydroxylamine accumulation and the expression of DnfA/DnfC was not observed (Fig. 1C), indicating that the production of hydroxylamine is likely influenced by additional factors beyond the expression of dnfABC.

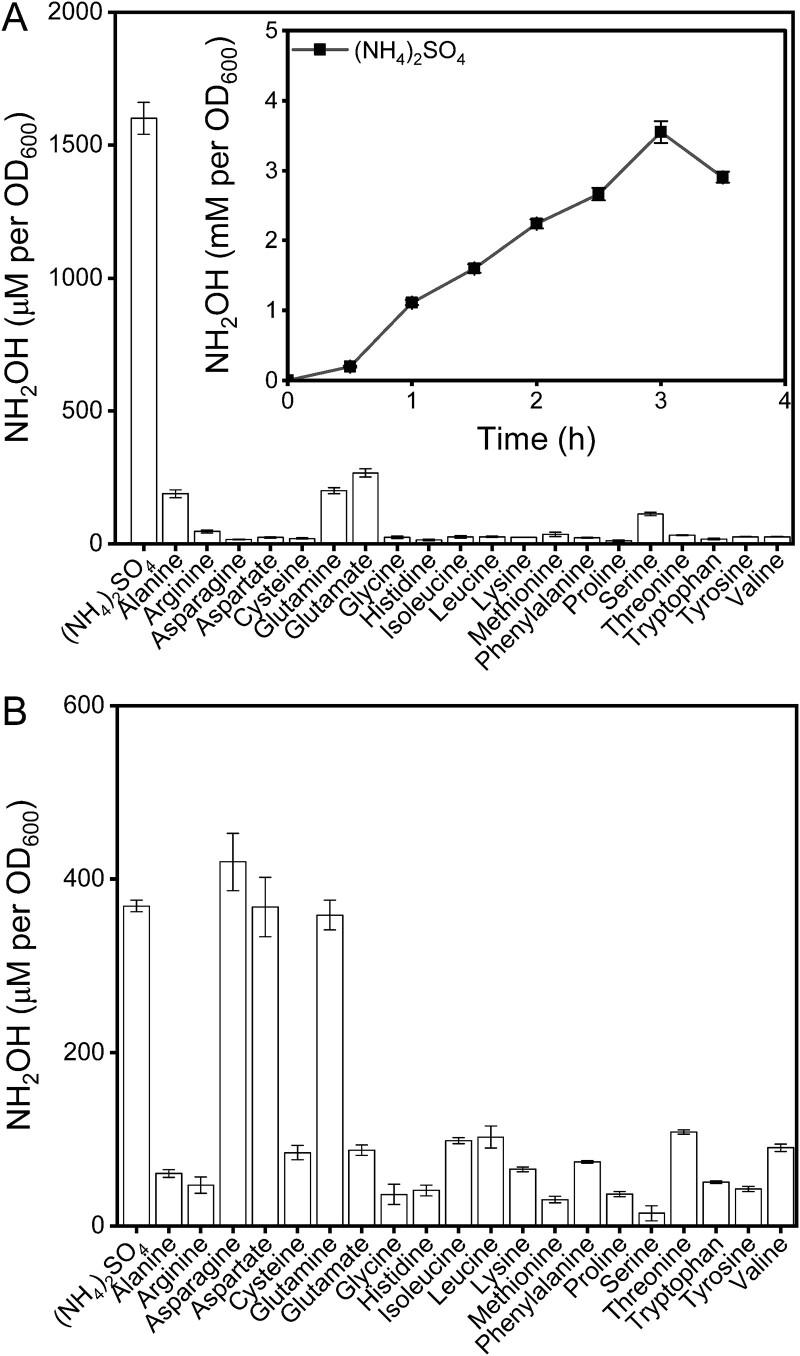

In the whole cell transformation assays, A. faecalis JQ135 and E. Coli harboring dnfABC oxidized amino acids to hydroxylamine

To mitigate the potential impact of varying DnfA/DnfC expression levels, whole cell transformation assays were conducted to directly assess the oxidation of amino acids to hydroxylamine. JQ135 cells cultured overnight were collected and then transferred into media containing either ammonia or various amino acids, with a final cell concentration adjusted to an OD600 of 1. Cells incubated with ammonia produced hydroxylamine with a linear accumulation rate of 20.6 ± 1.4 μM min−1, reaching a maximum hydroxylamine concentration of 3550 μM ± 157.3 μM at 180 min (Fig. 2A). The observed linear rate in hydroxylamine accumulation over a 180- min period indicates that the expression of DnfA/DnfC in resting cells is not significantly regulated by the presence of ammonia within a short timeframe. Substantial hydroxylamine accumulations were observed in media containing alanine (188.8 ± 14.5 μM), glutamine (200.0 ± 11.3 μM), glutamate (266.3 ± 15.2 μM) or serine (111.3 ± 6.5 μM), whereas limited hydroxylamine accumulations (11.25 ± 4.0 μM – 46.25 ± 5.4 μM) were observed with other amino acids at 90 min (Fig. 2A, Supplementary Fig. 3A). The hydroxylamine accumulation was substantially lower than that for ammonia (1601.3 ± 60.5 μM at 90 min), indicating a preference of JQ135 for oxidizing ammonia over amino acids (Fig. 2A, Supplementary Fig. 3A). Further experimental evidence demonstrated that cells with a deletion of dnfA did not produce hydroxylamine when incubated with ammonia or various amino acids, further supporting the idea that JQ135 recruits DnfABC to oxidize amino acids (Supplementary Fig. 2B).

Figure 2.

A. faecalis JQ135 and E. Coli cells harboring dnfABC oxidize amino acids besides ammonia in whole cell transformation assays. (A, B) the accumulations of hydroxylamine in JQ135 cells (A) and E. Coli cells harboring dnfABC (B) cultured with various nitrogen sources at 90 min. The insert panel shows hydroxylamine accumulation curve of JQ135 cells cultured with ammonia. The data are represented as the mean ± s.d. of biological triplicates.

To confirm the potential nitrogen sources for the dirammox pathway, an artificial nitrifier, engineered E. coli cells harboring dnfABC, was used in whole cell transformation assays. Cells cultured and induced in LB medium were collected and then transferred into media containing ammonia or various amino acids, with a final cell concentration adjusted to an OD600 of 1. The E. coli cells harboring dnfABC efficiently oxidized both ammonia and amino acids to hydroxylamine at 90 min (Fig. 2B). Significant hydroxylamine accumulations were observed in media containing asparagine (419.9 ± 33.2 μM), aspartate (367.9 ± 34.4 μM), or glutamine (358.6 ± 17.2 μM), respectively, which were comparable to that in medium containing ammonia (369.0 ± 6.7 μM) and significantly higher than those in media containing the other amino acids (14.8 ± 8.7 μM – 108.4 ± 2.3 μM) (Supplementary Fig. 3B). These findings indicate that the engineered heterotrophic nitrifier E. coli cells are capable of oxidizing ammonia and amino acids to hydroxylamine via DnfABC.

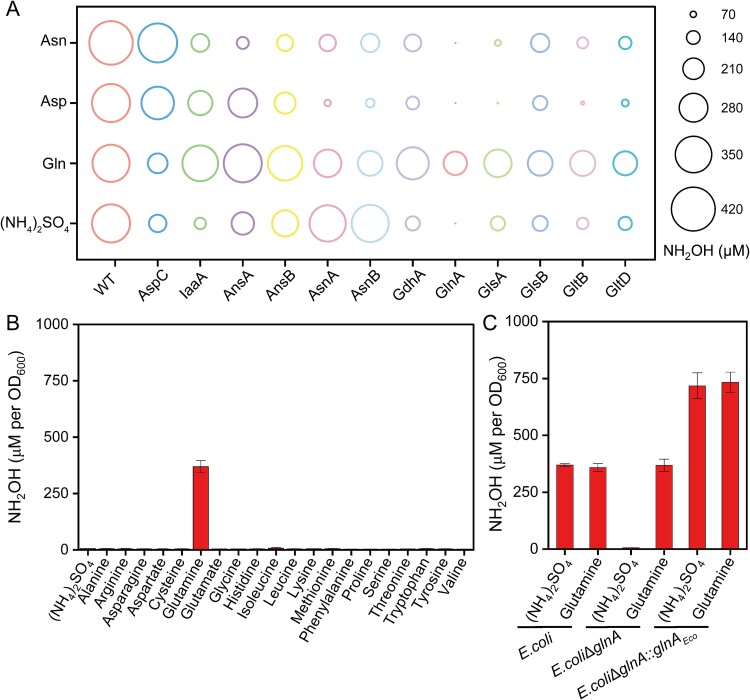

Gene glnA is the only one essential for ammonia and amino acid oxidation among those well-studied nitrogen metabolism genes

In the above assays, it was observed that JQ135 and E. coli cells harboring dnfABC were capable of oxidizing ammonia, glutamine, and some other amino acids, resulting in a significant accumulation of hydroxylamine. This implies the possibility for interconversion between these compounds, where some may transform into one another before undergoing oxidation to produce hydroxylamine. The nitrogen metabolism in E. coli has been extensively studied and the enzymes involved in the transformation of ammonia, asparagine, aspartate, and glutamine have been investigated, including aspartate transaminase AspC, asparaginase amidohydrolase IaaA, AnsA and AnsB, aspartate ammonia ligase AsnA and AsnB, glutamate dehydrogenase (GDH) GdhA, glutamine synthetase GlnA, glutaminase GlsA and GlsB, and glutamate synthase (glutamine-oxoglutarate amidotransferase [GOGAT]) GltBD (Supplementary Fig. 4A). To explore the potential heterotrophic nitrification pathway and the roles of these genes in the ammonia and amine oxidation, E. coli cells with individual gene deletion were transformed with the plasmid carrying dnfABC and subjected to hydroxylamine accumulation assays using ammonia, asparagine, aspartate, or glutamine as substrates.

The deletions of individual genes had diverse effects on the ability to oxidize ammonia and amino acids (Fig. 3A, Supplementary Fig. 4B). The deletion of glnA, as opposed to other genes, completely eliminated the ability to oxidize ammonia, aspartate, asparagine, and the other amino acids, whereas still maintained the ability to oxidize glutamine with the hydroxylamine accumulation of 232.4 ± 3.4 μM (65% of WT) (Fig. 3A and 3B). The complementary strain (E. coliΔglnA::glnAEco-dnfABC) restored the ability to oxidize ammonia (Fig. 3C). The higher hydroxylamine accumulation of the complementary strain, compared to the wildtype E. coli strain, was presumed to be related to the higher glnA expression in the plasmid vector than in the chromosome. Among the tested genes, glnA was the only gene that abolished the ammonia oxidation ability. Meanwhile, the deletion of any tested gene did not eliminate the ability to oxidize glutamine (Fig. 3A). Considered that GlnA plays an essential role in the ammonia assimilation and nitrogen metabolism, we propose that GlnA could catalyze the conversion of ammonia, that were transported into cells from outsides or released from other amino acids inside cells, into glutamine, followed by subsequent oxidation to hydroxylamine via DnfABC. It was also noticed that the deletion of some genes almost abolished or substantially reduced the hydroxylamine production based on some amino acids, such as the asnA, asnB, glsA, gltB, and gltD mutants cultured with aspartate and the glsA mutant cultured with asparagine. We thought those mutants weakened bacterial ability to convert those amino acids to ammonia inside cells and then reduced the hydroxylamine production.

Figure 3.

E. Coli cells harboring dnfABC require glnA to oxidize ammonia and amino acids, except glutamine. (A) the accumulation of hydroxylamine in E. Coli mutant strains harboring dnfABC cultured with ammonia, glutamine, asparagine or aspartate. (B) the accumulations of hydroxylamine in E. coliΔglnA harboring dnfABC with various nitrogen sources. (C) the accumulations of hydroxylamine in E. Coli, E. coliΔglnA, and E. coliΔglnA::glnA harboring dnfABC cultured with ammonia or glutamine. The data are represented as the mean ± s.d. of biological triplicates.

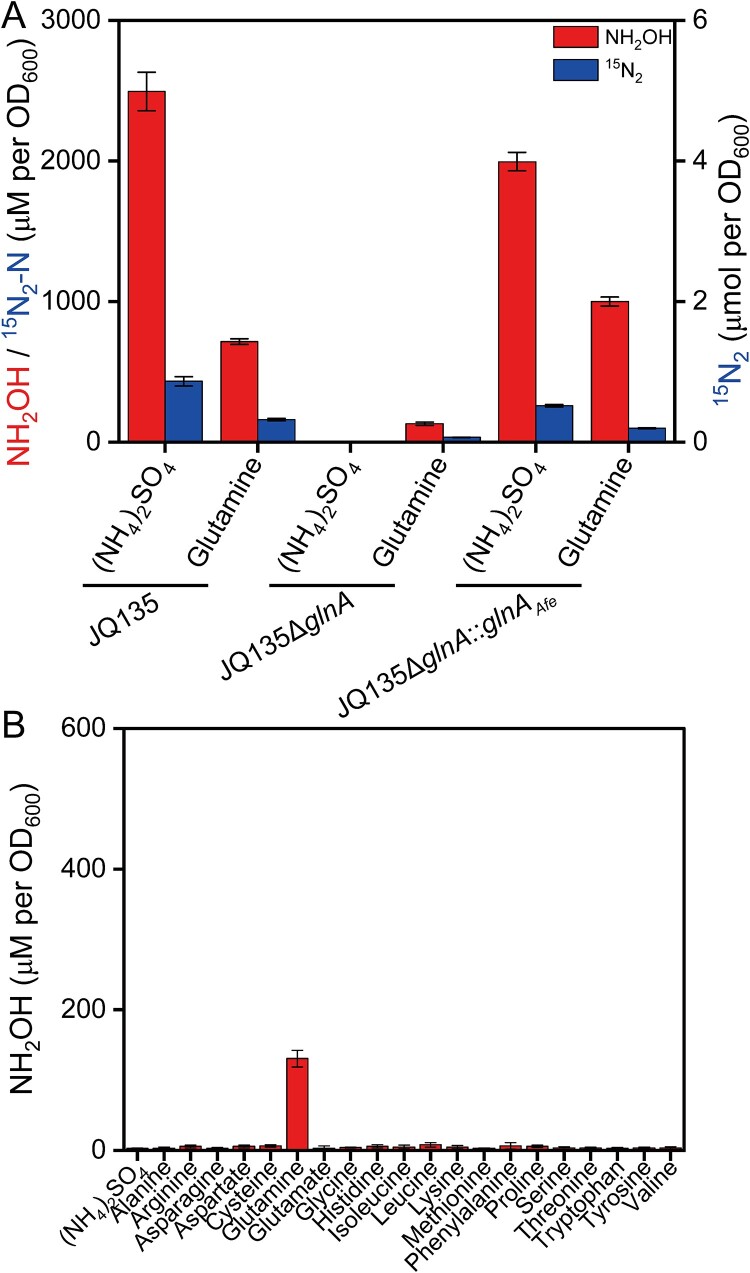

Knockout of glnA in A. faecalis JQ135 resulted in the loss of heterotrophic ammonia oxidation ability but kept the ability to oxidize glutamine

To assess the role of glnA in Alcaligenes, we constructed the JQ135 cell with the glnA gene deletion (JQ135ΔglnA) and then tested its ammonia and amino acid oxidation ability in both growth-dependent and -independent assays. In the growth-dependent assays, it was challenging to evaluate the role of glnA in ammonia oxidation because JQ135ΔglnA was unable to grow with ammonia as the sole nitrogen source. In contrast, JQ135ΔglnA was able to grow using glutamine as the sole nitrogen source, and produced 129.6 ± 6.7 μM hydroxylamine, although with a prolonged lag phase and slower growth compared to JQ135 (Supplementary Fig. 5).

JQ135ΔglnA cells were cultured, harvested and then incubated with media containing 15N-isotype labelled ammonia and amide-15N-isotype labelled glutamine for 90 min in a sealed bottle filled with 80% He and 20% O2 to conduct a whole cell transformation assay (growth-independent). No hydroxylamine accumulation or 15N2 production was detected when JQ135ΔglnA cells were incubated with 15N-isotype labeled ammonia (Fig. 4A). In contrast, JQ135 and the complementary strain JQ135ΔglnA::glnAAfe showed hydroxylamine accumulations of 2495.6 ± 136.7 μM (9.98 ± 0.55 μmol) and 1995.6 ± 65.5 μM (7.98 ± 0.26 μmol), respectively, along with 0.86 ± 0.06 μmol and 0.52 ± 0.02 μmol 15N2 (Fig. 4A). The stoichiometries of hydroxylamine and N2-N accumulation by JQ135 and the complementary strain JQ135ΔglnA::glnAAfe were 5.8: 1 and 7.7: 1, respectively. When incubated with media containing 10 mM amide-15N-isotype labelled glutamine, JQ135, JQ135ΔglnA, and JQ135ΔglnA::glnAAfe produced 715.2 ± 20.4 μM (2.86 ± 0.08 μmol), 130.4 ± 12.1 μM (0.52 ± 0.05 μmol), and 1000.0 ± 31.1 μM (4.00 ± 0.12 μmol) of hydroxylamine and 0.32 ± 0.02 μmol, 0.07 ± 0.005 μmol, and 0.20 ± 0.01 μmol of 15N2 (Fig. 4A). The stoichiometries of hydroxylamine and N2-N accumulation by JQ135, JQ135ΔglnA, and JQ135ΔglnA::glnAAfe were 4.5: 1, 4.0: 1, and 10.0: 1, respectively. These results indicate that the deletion of glnA abolished the ammonia oxidation ability and somehow weakened the glutamine oxidation ability instead of completely abolishing it. To assess the role of glnA in the oxidation of other amino acids, JQ135ΔglnA cells were incubated with media containing various amino acids for 90 min to conduct a whole cell transformation assay (growth-independent). It was observed that the other amino acids could not be oxidized by the cells lacking glnA, indicating the role of GlnA in the amino acid oxidation (Fig. 4B). Taken together, glnA is necessary for JQ135 to oxidize ammonia and most amino acids except glutamine. The DnfA/B/C multienzyme system has been reported to could convert glutamine to N2, yet there was no evidence to support DnfA directly oxidizing glutamine [37]. Actually, DnfA did not interact with glutamine but with hydroxylamine [37]. DnfC could hydrolyze glutamine and L-glutamic acid γ-hydroxamate (L-GlnγHXM), a common characteristic of amidotransferases. We thus propose a hypothesis that ammonia and amino acids are first converted into glutamine by GlnA along with some deaminases, then to some unidentified intermediate by DnfC, and oxidized to hydroxylamine and finally to dinitrogen gas by DnfAB (Fig. 5).

Figure 4.

The glnA gene is essential for A. faecalis JQ135 to oxidize ammonia. (A) the accumulations of hydroxylamine and nitrogen gas of JQ135, JQ135ΔglnA and JQ135ΔglnA::glnAAfe cells cultured with 15N-labelled ammonia or 15N-labelled glutamine in whole cell transformation assays. 15N2-N stands for the concentration of ammonia-N that has been converted to 15N2. (B) the hydroxylamine accumulation of JQ135ΔglnA cultured with various nitrogen sources in whole cell transformation assays. The data are represented as the mean ± s.d. of biological triplicates.

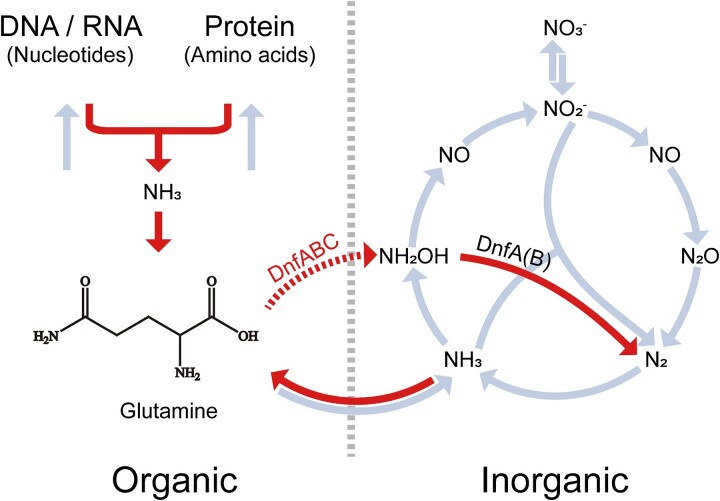

Figure 5.

The proposed dirammox pathway by A. faecalis JQ135. The interconversion of DNA/RNA/proteins and glutamine are shown in left panel and the nitrogen cycle in right. The proposed dirammox pathway includes the conversion of ammonia to glutamine, then to NH2OH, and finally to N2. The conversion of glutamine to hydroxylamine (the dotted arrow) lacks the direct evidence and its mechanism remains unclear.

Discussion

Heterotrophic nitrification has been defined more broadly than the strict definitions of nitrification and anammox. Ammonia has been considered as the primary substrate for most studied microorganisms and has received significant attention in research on heterotrophic nitrification. In contrast, some microorganisms have displayed a wider range of substrates, including hydroxylamine, pyruvic oxime, and organic nitrogen [12, 18–26]. It was proposed that some organic nitrogen compounds such as pyridine and quinoline were converted to ammonia, then oxidized to nitrite and/or nitrate and finally reduced to dinitrogen gas in Shinella zoogloeoides and Pseudomonas sp. [41, 42]. To assess the substrate range of A. faecalis JQ135, tests were conducted using various amino acids, revealing the ability to oxidize different amino acids to hydroxylamine, regardless of whether the assays were growth-dependent or -independent. The deletion of dnfA gene, which abolished the organic nitrogen oxidation ability, suggested that cells recruit dnfABC to oxidize organic nitrogen, similar to the oxidation of ammonia (Supplementary Fig. 2). This was further supported by E. coli cells harboring dnfABC, which also exhibited the ability to oxidize amino acids, confirming the role of dnfABC in organic nitrogen oxidation. These findings suggest A. faecalis possesses a broader substrate range than previously known, as it is capable of oxidizing both ammonia and organic nitrogen via gene cluster dnfABC that was proposed to mediate the oxidation of ammonia to dinitrogen gas (the dirammox pathway). This observation provides support for considering the use of A. faecalis to remove organic nitrogen in wastewater treatment. The dnfABC homologs have been found in strains across different bacterial genera [33], such as Microvigula aerodenitrificans BE2.4, Pseudomonas cedrina LMG23661, Delftia lacustris HQS1, Burkholderia pyrrocinia LWK2, Xanthobacter sp. R2A-8, Verminephrobacter aporrectodeae At4, Andreprevotia sp. IGB-42, Jeongeupia chitinilytica KCTC23701, and Pokkaliibacter plantistimulans L1E11 (Supplementary Fig. 6). Furthermore, it is believed that other heterotrophic nitrifiers, including those encoded dnfABC or not, may also possess broader substrate range than previously known. A comprehensive survey of the substrates of heterotrophic nitrifiers would provide valuable insights for investigating heterotrophic nitrification and expanding the potential applications of these microorganisms.

Currently, there is limited information available regarding the enzymes involved in heterotrophic nitrification, especially those involved in ammonia oxidation. Among the enzymes that have been characterized, only HAO, cytochrome P460, and pyruvic oxime dioxygenase have been well studied for their biochemical, genetic, and physiological properties [6, 25, 26, 43–46]. However, there is currently no biochemical evidence supporting that ammonia or the tested organic nitrogen compounds are direct substrates for these potential ammonia oxidizing enzymes in heterotrophic nitrifiers. In contrast, enzymes involved in the oxidation of hydroxylamine or pyruvic oximes, including HAO, P460, POD, and DnfA, have been experimentally demonstrated to directly act on hydroxylamine or pyruvic oxime [34, 45, 46]. Our assays indicated that the deletion of glutamine synthetase gene glnA abolished the ability of A. faecalis JQ135 and E. coli cells harboring dnfABC to oxidize ammonia and organic nitrogen, except glutamine. This finding excludes the possibility that ammonia and most of those tested amino acids are the direct substrates for DnfABC. Instead, it suggests that ammonia transported into cells from outsides or released from organic nitrogen inside cells were converted into glutamine and finally oxidized to hydroxylamine and dinitrogen gas by DnfABC (Fig. 5). Miao et al. observed that DnfABC converted glutamine to nitrogen gas in vitro and proposed that glutamine was oxidized to L-glutamic acid γ-hydroxamate (L-GlnγHXM) by DnfAB, hydrolyzed to hydroxylamine by DnfC and then oxidized to dinitrogen gas by DnfAB. Yet it lacked direct biochemical evidence for DnfA oxidizing glutamine [37]. Until now, we did not obtain direct evidence of DnfA oxidizing glutamine. We observed that DnfA interacted with hydroxylamine but not with glutamine using ITC and DSF assays [34]. Miao et al. also reported that DnfA did not interact with glutamine but with hydroxylamine [37]. We therefore concluded that DnfA oxidizes some unidentified intermediate rather than glutamine. DnfC was predicted to be a potential glutamine amidotransferase and essential for ammonia oxidation. The reported hydrolysis activity of glutamine and L-glutamic acid γ-hydroxamate (L-GlnγHXM) by DnfC was possibly an intrinsic feature of glutamine amidotransferases. Additionally, the expression levels of DnfC varied significantly in JQ135 cells cultured with glutamine, asparagine, and aspartate, yet the hydroxylamine accumulations of those cells were comparable to each other. This observation contradicts the hypothesis proposed by Miao et al., which suggested that a high concentration of DnfC would inhibit hydroxylamine production. Some Alcaligenes members encoding dnfABC were observed not to oxidize ammonia to hydroxylamine [31], suggesting DnfABC enzymes and substrate glutamine were necessary but insufficient. Based on these observations, it can be inferred that glutamine is not a direct substrate of DnfA, emphasizing the intricate biochemical and physiological characteristics involved in heterotrophic nitrification. Although direct evidence to confirm or exclude glutamine as the direct substrate of DnfA was not provided, it is plausible that glutamine undergoes conversion into an unidentified organic nitrogen compound before oxidation occurs. Recently, Lenferink et al. observed that addition of 2.5 mM 14NH4Cl, 500 μM Na14NO2, and then 250 μM 15NH2OH (added 1.5 h after the addition of 14NH4Cl and 14NaNO2) generated ~10 μM 30N2-N (4% of 15NH2OH-N) after 4–8 h in sterile medium or medium containing heat-killed Alcaligenes cells, and only 1–2 μM 30N2-N in medium containing Alcaligenes cells, with conversion of hydroxylamine to N2 being considered an abiotic process [38]. 14NH2OH was produced at 1.5 h in media containing living cells in these assays and hydroxylamine concentrations (14NH2OH and 15NH2OH) were maintained at 500 μM from 4 to 8 h after the addition of 250 μM 15NH2OH [38]. The added 15NH2OH would react with 14NH2OH produced from 14NH4+ to generate 29N2, which complicated the interpretation. We believe Lenferink observed an abiotic conversion of hydroxylamine as with our biochemical assays, but this did not conclusively demonstrate a lack of biotic oxidation of hydroxylamine to N2 by DnfA that might dominate the conversion of hydroxylamine to N2 under some conditions.

In the growth-dependent assays, it was observed that the expression of DnfA/DnfC was not consistently correlated with hydroxylamine accumulation during the oxidation of ammonia and amino acids by JQ135, indicating that the presence of a regulatory mechanism independent of gene expression that influenced hydroxylamine production. The assimilation of ammonia into glutamine by GlnA could potentially be one of the processes involved in regulating ammonia oxidation. Furthermore, we noticed that the oxidation of ammonia in JQ135 was significantly faster than that of glutamine in the growth-independent assay despite the established role of glutamine as an essential intermediate for ammonia oxidation, whereas the oxidation velocities of ammonia and glutamine were found to be similar in E. coli cells harboring dnfABC. The faster oxidation rate observed for ammonia suggests the involvement of unidentified rate-limiting steps specific to ammonia oxidation pathway, which differ from those associated with glutamine. The different ammonia and glutamine transporters might be one rate-limited step. Also, the synthesis of the proposed unidentified intermediate might be another rate-limiting step. We believe the presence of ammonia, rather than glutamine, likely enhances the synthesis of those rate-limiting intermediates.

The assimilation of ammonia requires energy, which could account for one of the reasons why heterotrophic nitrification necessitates the presence of additional organic matter. Furthermore, the absence of autotrophic amoA genes in the genomes of identified heterotrophic nitrifiers supports ammonia assimilation prior to oxidation. The reported heterotrophic amoA gene in Pseudomonas sp. has been discredited as associated with heterotrophic nitrification due to its sequence containing fragments from two neighboring genes [33]. Furthermore, the fact that the deletion of its homolog had no impact on the ammonia oxidation ability of A. faecalis JQ135 lends further support to this conclusion [33, 47]. Therefore, we propose a hypothesis that ammonia-oxidizing heterotrophic nitrifiers assimilate ammonia and subsequently oxidize unidentified amines to hydroxylamine and finally to dinitrogen gas, nitrite or nitrate, just like A. faecalis JQ135 and the artificially engineered heterotrophic nitrifier E. coli cells did. The other two enzymes involved in ammonia assimilation were not necessary for ammonia oxidation, i.e. GDH that catalyzes the reversible formation of 2-oxoglutarate to glutamate and that GOGAT catalyzes the formation of two glutamate molecules from 2-oxoglutarate and glutamine. Additional challenging and direct evidence is required to understand the intricate mechanism of ammonia oxidation fully. The single gene knockout approach used here is not enough for identifying those genes involved in dirammox. A mutagenesis library should be a much more appropriate choice to reveal all the genes involved in the dirammox pathway. Multi-omics assays would highlight those genes, proteins, and metabolites important for dirammox. Further, the identification of the DnfR and/or DnfC ligands via co-purification would provide us a direct clue for the substrate of DnfABC. Nonetheless, we remain committed to uncovering the ammonia oxidation pathway in the following study.

Converting glutamine to hydroxylamine by DnfABC shunts the organic nitrogen metabolism to the inorganic nitrogen one. Until now, the precise role of heterotrophic nitrification in the nitrogen cycle remains unclear, apart from its speculated involvement in specific niches. For example, heterotrophic nitrification has been proposed to respond to produce N2O in acid soils where the autotrophic nitrifiers were inhibited by low pH and could not produce N2O [48]. Previously, heterotrophic nitrification has been proposed to occur as an inorganic pathway or an organic pathway [49]. Some studies have also shown the effect of organic nitrogen on heterotrophic nitrification and the production of N2O during heterotrophic nitrification [50]. In this study, we present compelling biological evidence to establish a direct link between organic nitrogen metabolism and the nitrogen biogeochemical cycle with glutamine identified as the intermediary compound in this linkage. Our findings have identified an additional pathway connects organic and inorganic nitrogen metabolism, which was previously though to primarily involve ammonization and ammonia assimilation. Given the prevalence of organic nitrogen and the wide distribution of heterotrophic nitrifiers Alcaligenes in the environment [31], it is imperative that we pay closer attention to the shunt from central nitrogen metabolism to inorganic nitrogen to fully assess the role of dirammox pathway in the nitrogen cycle.

The adaptive advantage is an obvious question for understanding dirammox. In contrast to the obvious role in energy generation of nitrification and anammox, the advantage of dirammox remains mystery. It has been speculated that bacteria could balance electron transfer and neutralize the toxicity of high concentrations of ammonia via dirammox [32]. Bacteria could also inhibit the growth of other strains via hydroxylamine and then adapt to environments with competitors [51, 52]. We found that hydroxylamine inhibited the growth of JQ135 and DnfA deletion mutant (JQ135ΔdnfA) with IC50 values of 2.5 ± 0.2 mM and 2.5 ± 0.3 mM, respectively (Supplementary Fig. 7). The IC50 values are higher than the hydroxylamine accumulation concentrations during growth, suggesting that JQ135 could tolerate the hydroxylamine itself produced via some unknown mechanisms. The sequential conversion of hydroxylamine to N2 could prevent accumulation of high concentration hydroxylamine. The oxidation of ammonia to hydroxylamine, using glutamine as an intermediate, could be easily regulated by the bacterial carbon/nitrogen ratio, preventing the consumption of excess nitrogen sources beyond bacterial growth.

In summary, our study revealed that heterotrophic nitrifier A. faecalis JQ135 oxidized ammonia and amines by first converting them to glutamine. We therefore hypothesized most heterotrophic nitrifiers that did not encode any AMO homologs might oxidize ammonia after it has been assimilation. This hypothesis challenges the paradigm of heterotrophic nitrification. The conversion from glutamine to hydroxylamine by dirammox enzymes DnfABC introduces an additional pathway connecting organic and inorganic nitrogen metabolisms, supplementing the existing ammonization and ammonia assimilation routes (Fig. 5). Consequently, further investigation is warranted to explore the role of this shunt in the nitrogen cycle.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (92351302, 32370041, 92051101) and the National Key R&D Program of China (2019YFA0905501). We thank Professor Ji-Guo Qiu and Dr. Si-Qiong Xu from Nanjing Agricultural University for generously providing the bacteria and plasmids used in this study.

Contributor Information

Ya-Ling Qin, State Key Laboratory of Microbial Resources, Institute of Microbiology, Chinese Academy of Sciences, No. 1 Beichen West Road, Chaoyang District, Beijing 100101, P. R. China; School of Life Sciences, University of Chinese Academy of Sciences, No. 1 Yanqihu East Road, Huairou District, Beijing 100049, P. R. China.

Zong-Lin Liang, State Key Laboratory of Microbial Resources, Institute of Microbiology, Chinese Academy of Sciences, No. 1 Beichen West Road, Chaoyang District, Beijing 100101, P. R. China; School of Life Sciences, University of Chinese Academy of Sciences, No. 1 Yanqihu East Road, Huairou District, Beijing 100049, P. R. China.

Guo-Min Ai, State Key Laboratory of Microbial Resources, Institute of Microbiology, Chinese Academy of Sciences, No. 1 Beichen West Road, Chaoyang District, Beijing 100101, P. R. China.

Wei-Feng Liu, State Key Laboratory of Microbial Resources, Institute of Microbiology, Chinese Academy of Sciences, No. 1 Beichen West Road, Chaoyang District, Beijing 100101, P. R. China.

Yong Tao, State Key Laboratory of Microbial Resources, Institute of Microbiology, Chinese Academy of Sciences, No. 1 Beichen West Road, Chaoyang District, Beijing 100101, P. R. China; School of Life Sciences, University of Chinese Academy of Sciences, No. 1 Yanqihu East Road, Huairou District, Beijing 100049, P. R. China.

Cheng-Ying Jiang, State Key Laboratory of Microbial Resources, Institute of Microbiology, Chinese Academy of Sciences, No. 1 Beichen West Road, Chaoyang District, Beijing 100101, P. R. China; School of Life Sciences, University of Chinese Academy of Sciences, No. 1 Yanqihu East Road, Huairou District, Beijing 100049, P. R. China.

Shuang-Jiang Liu, State Key Laboratory of Microbial Resources, Institute of Microbiology, Chinese Academy of Sciences, No. 1 Beichen West Road, Chaoyang District, Beijing 100101, P. R. China; School of Life Sciences, University of Chinese Academy of Sciences, No. 1 Yanqihu East Road, Huairou District, Beijing 100049, P. R. China.

De-Feng Li, State Key Laboratory of Microbial Resources, Institute of Microbiology, Chinese Academy of Sciences, No. 1 Beichen West Road, Chaoyang District, Beijing 100101, P. R. China; School of Life Sciences, University of Chinese Academy of Sciences, No. 1 Yanqihu East Road, Huairou District, Beijing 100049, P. R. China.

Author contributions

D-FL and S-JL designed the project. Y-LQ and Z-LL performed the experiments and prepared tables and figures. W-FL and Y-T contributed to bacterial resources from Keio collection. Y-LQ and D-FL performed analysis and visualization of data and wrote the original draft. C-YJ, S-JL, and D-FL contributed to reviewing and editing the final manuscript. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Funding

The National Natural Science Foundation of China (92351302, 32370041, 92051101) and the National Key R&D Program of China (2019YFA0905501).

Data availability

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article and its supplementary information files.

References

- 1. Kuypers MMM, Marchant HK, Kartal B. The microbial nitrogen-cycling network. Nat Rev Microbiol 2018;16:263–76. 10.1038/nrmicro.2018.9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. van Kessel MA, Speth DR, Albertsen M et al. Complete nitrification by a single microorganism. Nature 2015;528:555–9. 10.1038/nature16459 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Daims H, Lebedeva EV, Pjevac P et al. Complete nitrification by Nitrospira bacteria. Nature 2015;528:504–9. 10.1038/nature16461 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Kartal B, Maalcke WJ, de Almeida NM et al. Molecular mechanism of anaerobic ammonium oxidation. Nature 2011;479:127–30. 10.1038/nature10453 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Stein LY. Heterotrophic nitrification and nitrifier denitrification. In: Ward BB, Arp DJ, Klotz MG (eds.),Nitrification. Washington, DC: ASM Press. 2011;95–114. 10.1128/9781555817145.ch5 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Jetten MS, de Bruijn P, Kuenen JG. Hydroxylamine metabolism in Pseudomonas PB16: involvement of a novel hydroxylamine oxidoreductase. Antonie van Leeuwenhoek 1997;71:69–74. 10.1023/A:1000145617904 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. van Niel EW, Braber KJ, Robertson LA et al. Heterotrophic nitrification and aerobic denitrification in Alcaligenes faecalis strain TUD. Antonie van Leeuwenhoek 1992;62:231–7. 10.1007/BF00582584 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Robertson LA, Kuenen JG. Combined heterotrophic nitrification and aerobic denitrification in Thiosphaera pantotropha and other bacteria. Antonie van Leeuwenhoek 1990;57:139–52. 10.1007/BF00403948 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Yang Y, Lin E, Huang S. Heterotrophic nitrogen removal in Bacillus sp. K5: involvement of a novel hydroxylamine oxidase. Water Sci Technol 2017;76:3461–7. 10.2166/wst.2017.510 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Zhang S, Sun X, Fan Y et al. Heterotrophic nitrification and aerobic denitrification by Diaphorobacter polyhydroxybutyrativorans SL-205 using poly (3-hydroxybutyrate-co-3-hydroxyvalerate) as the sole carbon source. Bioresour Technol 2017;241:500–7. 10.1016/j.biortech.2017.05.185 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Ralt D, Gomez RF, Tannenbaum SR. Conversion of acetohydroxamate and hydroxylamine to nitrite by intestinal microorganisms. Eur J Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 1981;12:226–30. 10.1007/BF00499492 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12. van Gool AP, Schmidt EL. Nitrification in relation to growth in Aspergillus flaws. Soil Biol Biochem 1973;5:259–65. 10.1016/0038-0717(73)90009-6 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Zhao B, An Q, He YL et al. N2O and N2 production during heterotrophic nitrification by Alcaligenes faecalis strain NR. Bioresour Technol 2012;116:379–85. 10.1016/j.biortech.2012.03.113 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Chen J, Gu S, Hao H et al. Characteristics and metabolic pathway of Alcaligenes sp. TB for simultaneous heterotrophic nitrification-aerobic denitrification. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 2016;100:9787–94. 10.1007/s00253-016-7840-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Castignetti D, Palutsis D, Turley J. An examination of proton translocation and energy conservation during heterotrophic nitrification. FEMS Microbiol Lett 1990;54:175–81. 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1990.tb03992.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Castignetti D, Gunner HB. Sequential nitrification by an Alcaligenes sp. and Nitrobacter agilis. Can J Microbiol 1980;26:1114–9. 10.1139/m80-184 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Zhang Q, Zhu Y, Yuan C et al. Nitrogen removal and mechanism of an extremely high-ammonia tolerant heterotrophic nitrification-aerobic denitrification bacterium Alcaligenes faecalis TF-1. Bioresour Technol 2022;361:127643. 10.1016/j.biortech.2022.127643 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Nemergut DR, Schmidt SK. Disruption of narH, narJ, and moaE inhibits heterotrophic nitrification in Pseudomonas strain M19. Appl Environ Microbiol 2002;68:6462–5. 10.1128/AEM.68.12.6462-6465.2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Molina JAE, Alexander M. Oxidation of nitrite and hydroxylamine by Aspergillus flavus, peroxidase and catalase. Antonie van Leeuwenhoek 1972;38:505–12. 10.1007/BF02328117 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Schimel JP, Firestone MK, Killham KS. Identification of heterotrophic nitrification in a sierran forest soil. Appl Environ Microbiol 1984;48:802–6. 10.1128/aem.48.4.802-806.1984 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Stroo HF, Klein TM, Alexander M. Heterotrophic nitrification in an acid forest soil and by an acid-tolerant fungus. Appl Environ Microbiol 1986;52:1107–11. 10.1128/aem.52.5.1107-1111.1986 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Spiller H, Dietsch E, Kessler E. Intracellular appearance of nitrite and nitrate in nitrogen-starved cells of Ankistrodesmus braunii. Planta 1976;129:175–81. 10.1007/BF00390025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Joo HS, Hirai M, Shoda M. Characteristics of ammonium removal by heterotrophic nitrification-aerobic denitrification by Alcaligenes faecalis No. 4. J Biosci Bioeng 2005;100:184–91. 10.1263/jbb.100.184 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Castignetti D, Hollocher TC. Heterotrophic nitrification among denitrifiers. Appl Environ Microbiol 1984;47:620–3. 10.1128/aem.47.4.620-623.1984 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Ono Y, Enokiya A, Masuko D et al. Pyruvic oxime dioxygenase from the heterotrophic nitrifier: purification, and molecular and enzymatic properties. Plant Cell Physiol 1999;40:47–52. 10.1093/oxfordjournals.pcp.a029473 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Otte S, Schalk J, Kuenen JG et al. Hydroxylamine oxidation and subsequent nitrous oxide production by the heterotrophic ammonia oxidizer Alcaligenes faecalis. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 1999;51:255–61. 10.1007/s002530051390 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Joo HS, Hirai M, Shoda M. Nitrification and denitrification in high-strength ammonium by Alcaligenes faecalis. Biotechnol Lett 2005;27:773–8. 10.1007/s10529-005-5634-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Castignetti D, Gunner HB. Nitrite and nitrate synthesis from pyruvic-oxime by an Alcaligenes sp. Curr Microbiol 1981;5:379–84. 10.1007/BF01566754 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Castignetti D, Petithory JR, Hollocher TC. Pathway of oxidation of pyruvic oxime by a heterotrophic nitrifier of the genus Alcaligenes: evidence against hydrolysis to pyruvate and hydroxylamine. Arch Biochem Biophys 1983;224:587–93. 10.1016/0003-9861(83)90246-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Castignetti D, Hollocher TC. Nitrogen redox metabolism of a heterotrophic, nitrifying-denitrifying Alcaligenes sp. from soil. Appl Environ Microbiol 1982;44:923–8. 10.1128/aem.44.4.923-928.1982 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Hou TT, Miao LL, Peng JS et al. Dirammox is widely distributed and dependently evolved in Alcaligenes and is important to nitrogen cycle. Front Microbiol 2022;13:864053. 10.3389/fmicb.2022.864053 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Wu MR, Hou TT, Liu Y et al. Novel Alcaligenes ammonioxydans sp. Nov. from wastewater treatment sludge oxidizes ammonia to N2 with a previously unknown pathway. Environ Microbiol 2021;23:6965–80. 10.1111/1462-2920.15751 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Xu SQ, Qian XX, Jiang YH et al. Genetic foundations of direct ammonia oxidation (dirammox) to N2 and MocR-like transcriptional regulator DnfR in Alcaligenes faecalis strain JQ135. Appl Environ Microbiol 2022;88:e0226121. 10.1128/aem.02261-21 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Wu MR, Miao LL, Liu Y et al. Identification and characterization of a novel hydroxylamine oxidase, DnfA, that catalyzes the oxidation of hydroxylamine to N2. J Biol Chem 2022;298:102372. 10.1016/j.jbc.2022.102372 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Makris TM, Vu VV, Meier KK et al. An unusual peroxo intermediate of the arylamine oxygenase of the chloramphenicol biosynthetic pathway. J Am Chem Soc 2015;137:1608–17. 10.1021/ja511649n [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Choi YS, Zhang H, Brunzelle JS et al. In vitro reconstitution and crystal structure of p-aminobenzoate N-oxygenase (AurF) involved in aureothin biosynthesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2008;105:6858–63. 10.1073/pnas.0712073105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Miao LL, Hou TT, Ma L et al. N-hydroxylation and hydrolysis by the DnfA/B/C multienzyme system involved in the aerobic N2 formation process. ACS Catal 2023;13:11963–76. 10.1021/acscatal.3c02412 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Lenferink WB, Bakken LR, Jetten MSM et al. Hydroxylamine production by Alcaligenes faecalis challenges the paradigm of heterotrophic nitrification. Sci Adv 2024;10:eadl3587. 10.1126/sciadv.adl3587 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Baba T, Ara T, Hasegawa M et al. Construction of Escherichia coli K-12 in-frame, single-gene knockout mutants: the Keio collection. Mol Syst Biol 2006;2:2006–0008. 10.1038/msb4100050 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Frear DS, Burrell RC. Spectrophotometric method for determining hydroxylamine reductase activity in higher plants. Anal Chem 1955;27:1664–5. 10.1021/ac60106a054 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Bai Y, Sun Q, Zhao C et al. Aerobic degradation of pyridine by a new bacterial strain, Shinella zoogloeoides BC026. J Ind Microbiol Biotechnol 2009;36:1391–400. 10.1007/s10295-009-0625-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Bai Y, Sun Q, Zhao C et al. Quinoline biodegradation and its nitrogen transformation pathway by a Pseudomonas sp. strain. Biodegradation 2010;21:335–44. 10.1007/s10532-009-9304-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Wehrfritz JM, Reilly A, Spiro S et al. Purification of hydroxylamine oxidase from Thiosphaera pantotropha. Identification of electron acceptors that couple heterotrophic nitrification to aerobic denitrification. FEBS Lett 1993;335:246–50. 10.1016/0014-5793(93)80739-H [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Moir JW, Wehrfritz JM, Spiro S et al. The biochemical characterization of a novel non-haem-iron hydroxylamine oxidase from Paracoccus denitrificans GB17. Biochem J 1996;319:823–7. 10.1042/bj3190823 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Bergmann DJ, Zahn JA, Hooper AB et al. Cytochrome P460 genes from the methanotroph Methylococcus capsulatus bath. J Bacteriol 1998;180:6440–5. 10.1128/JB.180.24.6440-6445.1998 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Wehrfritz J, Carter JP, Spiro S et al. Hydroxylamine oxidation in heterotrophic nitrate-reducing soil bacteria and purification of a hydroxylamine-cytochrome c oxidoreductase from a Pseudomonas species. Arch Microbiol 1996;166:421–4. 10.1007/BF01682991 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Daum M, Zimmer W, Papen H et al. Physiological and molecular biological characterization of ammonia oxidation of the heterotrophic nitrifier Pseudomonas putida. Curr Microbiol 1998;37:281–8. 10.1007/s002849900379 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Zhang Y, Zhao W, Cai Z et al. Heterotrophic nitrification is responsible for large rates of NO emission from subtropical acid forest soil in China. Eur J Soil Sci 2018;69:646–54. 10.1111/ejss.12557 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Kuenen JG, Robertson LA. Combined nitrification-denitrification processes. FEMS Microbiol Rev 1994;15:109–17. 10.1111/j.1574-6976.1994.tb00129.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Zhang JB, Müller C, Cai ZC. Heterotrophic nitrification of organic N and its contribution to nitrous oxide emissions in soils. Soil Biol Biochem 2015;84:199–209. 10.1016/j.soilbio.2015.02.028 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Gao XY, Xie W, Liu Y et al. Alcaligenes ammonioxydans HO-1 antagonizes Bacillus velezensis via hydroxylamine-triggered population response. Front Microbiol 2022;13:920052. 10.3389/fmicb.2022.920052 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Shoda M. Chapter 2-Alcaligenes. In: Amaresan N., Senthil Kumar M., Annapurna K. et al. (eds.), Beneficial Microbes in Agro-Ecology. Amsterdam: Academic Press, 13–26. Retreived from https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/B9780128234143000022 [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article and its supplementary information files.