Abstract

Background

Colony stimulating factors (CSFs), also called haematopoietic growth factors, regulate bone marrow production of circulating red and white cells, and platelets. Some CSFs also mobilise the release of bone marrow stem cells into the circulation. CSFs have been shown to be neuroprotective in experimental stroke.

Objectives

To assess (1) the safety and efficacy of CSFs in people with acute or subacute ischaemic or haemorrhagic stroke, and (2) the effect of CSFs on circulating stem and blood cell counts.

Search methods

We searched the Cochrane Stroke Group Trials Register (last searched September 2012), the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) (The Cochrane Library 2012, Issue 4), MEDLINE (1985 to September 2012), EMBASE (1985 to September 2012) and Science Citation Index (1985 to September 2012). In an attempt to identify further published, unpublished and ongoing trials we contacted manufacturers and principal investigators of trials (last contacted April 2012). We also searched reference lists of relevant articles and reviews.

Selection criteria

We included randomised controlled trials recruiting people with acute or subacute ischaemic or haemorrhagic stroke. CSFs included stem cell factor (SCF), erythropoietin (EPO), granulocyte colony stimulating factor (G‐CSF), granulocyte‐macrophage colony stimulating factor (GM‐CSF), macrophage‐colony stimulating factor (M‐CSF, CSF‐1), thrombopoietin (TPO), or analogues of these. The primary outcome was functional outcome at the end of the trial. Secondary outcomes included safety at the end of treatment, death at the end of follow‐up, infarct volume and haematology measures.

Data collection and analysis

Two review authors (TE and NS) independently extracted data and assessed trial quality. We contacted study authors for additional information.

Main results

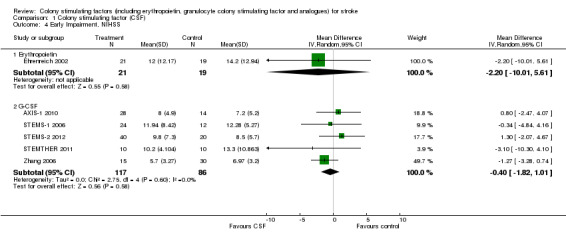

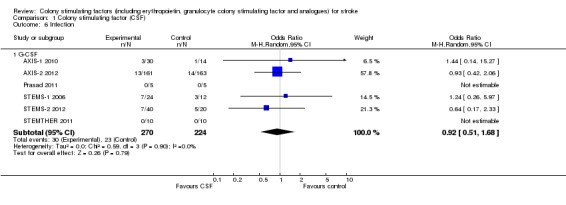

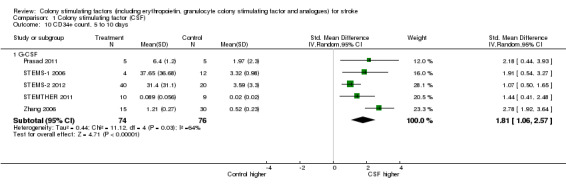

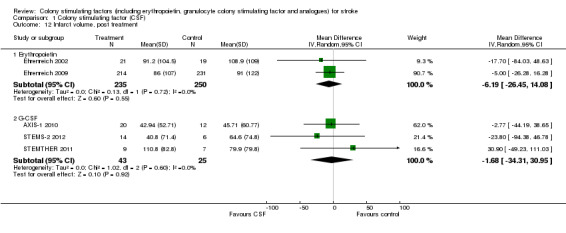

We included a total of 11 studies involving 1275 participants. In three trials (n = 782), EPO therapy was associated with a significant increase in death by the end of the trial (odds ratio (OR) 1.98, 95% confidence interval (CI) 1.19 to 3.3, P = 0.009) and a non‐significant increase in serious adverse events. EPO significantly increased the red cell count with no effect on platelet or white cell count, or infarct volume. Two small trials of carbamylated EPO have been completed but have yet to be reported. We included eight small trials (n = 548) of G‐CSF. G‐CSF was associated with a non‐significant reduction in early impairment (mean difference (MD) ‐0.4, 95% CI ‐1.82 to 1.01, P = 0.58) but had no effect on functional outcome at the end of the trial. G‐CSF significantly elevated the white cell count and the CD34+ cell count, but had no effect on infarct volume. Further trials of G‐CSF are ongoing.

Authors' conclusions

There are significant safety concerns regarding EPO therapy for stroke. It is too early to know whether other CSFs improve functional outcome.

Keywords: Humans, Colony‐Stimulating Factors, Colony‐Stimulating Factors/adverse effects, Colony‐Stimulating Factors/therapeutic use, Erythropoietin, Erythropoietin/adverse effects, Erythropoietin/therapeutic use, Granulocyte Colony‐Stimulating Factor, Granulocyte Colony‐Stimulating Factor/adverse effects, Granulocyte Colony‐Stimulating Factor/therapeutic use, Randomized Controlled Trials as Topic, Stroke, Stroke/drug therapy

Plain language summary

Colony stimulating factors (including erythropoietin, granulocyte colony stimulating factor and analogues) for stroke

Colony stimulating factors (CSFs) are naturally occurring hormones that control the production of circulating blood cells by the bone marrow. Some CSFs also release stem cells from the bone marrow into the blood stream; these could help the brain repair itself after stroke. In experiments of stroke, CSFs show the potential to improve disability caused by a stroke. In this analysis, we assessed the effect of CSFs on outcome after stroke using data from clinical trials of people with recent stroke. We included a total of 11 studies and 1275 participants. A higher death rate was observed in participants treated with erythropoietin (EPO) in three trials (782 participants); whether further trials of EPO will be performed early after stroke remains unclear. In eight small trials involving 548 participants, patterns of improvement after a stroke were observed using granulocyte colony stimulating factor (G‐CSF) and further trials are ongoing. Currently, there is insufficient evidence to support the use of CSFs in the treatment of people with recent stroke.

Background

Description of the condition

Stroke is one the commonest causes of disability worldwide (Murray 2012), ranked third in all causes of global disability life‐years. There are very few effective treatments for acute stroke: aspirin, thrombolysis and hemicraniectomy for ischaemic stroke, and none for haemorrhagic stroke. Colony stimulating factors (e.g. erythropoietin, granulocyte colony stimulating factor) show promise for therapeutic use in experimental stroke and in early human clinical trials.

Description of the intervention

Colony stimulating factors (CSFs), also called haemopoietic growth factors, regulate the bone marrow production of circulating red cells, white cells and platelets. CSFs act on stem cells leading to lineage‐specific differentiation. Stem cell factor (SCF) regulates the differentiation of CD34+ stem cells whilst other factors modulate the synthesis of more specific cell types: erythropoietin (EPO) for red cells; granulocyte colony stimulating factor (G‐CSF) for neutrophils; granulocyte‐macrophage colony stimulating factor (GM‐CSF) for macrophages and neutrophils; macrophage colony stimulating factor (M‐CSF, or colony‐stimulating factor‐1, CSF‐1) for monocytes; and thrombopoietin (TPO) for megakaryocyte maturation and platelet synthesis. Evidence now suggests that these factors may be candidate treatments for stroke, either as potential neuroprotectants or as neuroreparative agents (Sprigg 2004).

How the intervention might work

SCF is a haemopoietic cytokine produced by bone marrow stromal cells. It has limited clonogenic activity when used alone but augments other CSFs, including G‐CSF (Gabrilove 1994). When administered following middle cerebral artery occlusion in pre‐clinical studies, SCF induced neuroproliferation and neurogenesis (Jin 2002), the former by a combination of inducing migration of bone marrow derived cells to the peri‐infarct area and stimulating proliferation of intrinsic neural progenitor cells (Kawada 2006). Alone and in combination with G‐CSF, SCF can reduce infarct size and induce functional improvement in rat models of acute stroke (Zhao 2007a). Similarly, in experimental chronic stroke (3.5 months post ictus), SCF plus G‐CSF treated rats had an improved outcome and a reduced infarct volume when compared with control (Zhao 2007b).

EPO controls red cell production and has been available in recombinant form since 1985; it has been utilised for the treatment of anaemia in people with end‐stage renal disease since 1988. EPO was neuroprotective in experimental stroke (Brines 2000) and increased functional recovery (Wang 2004), effects possibly mediated by inhibiting apoptosis in the penumbra (Siren 2001). In a small clinical trial, EPO was safe and well tolerated (Ehrenreich 2002) but in the following phase III trial safety concerns were raised (Ehrenreich 2009). Derivatives of EPO, e.g. carbamylated EPO, which do not alter red cell kinetics but retain their neuroprotective activity, have been developed (Erbayraktar 2003; Leist 2004); small clinical studies of these have been completed but have yet to be reported.

G‐CSF acts on haemopoietic stem (CD34+) cells to regulate neutrophil progenitor proliferation and differentiation. It is used routinely to mobilise stem cells in humans for transplantation into patients with haematological malignancies, or in the patients themselves. Pre‐clinical studies have found that G‐CSF modulates the regenerative ability of cells in the brain and enhances their capacity to acquire neuronal characteristics. When given to mice following intravenous bone marrow transplantation, G‐CSF increased the number of neuronal cells derived from bone marrow precursors (Corti 2002). Administration of G‐CSF to mice (Six 2003) or rats (Schabitz 2003; Shyu 2004) improved survival and reduced cerebral infarct size in experimental studies. Functional recovery was also enhanced, with mice demonstrating improved cognition (Gibson 2005a; Gibson 2005b), and rats demonstrating improved neurological behaviour (Shyu 2004). A recent meta‐analysis observed that these effects occur in transient but not permanent models of cerebral ischaemia (England 2009). Neuroprotective effects are thought to relate to an anti‐inflammatory action, with up‐regulation of transcription protein STAT‐3. G‐CSF also appeared to reduce apoptosis and enhance neurogenesis (Schneider 2005a). Interestingly, G‐CSF deficient mice have larger infarcts, effects that are reversed by G‐CSF administration (Sevimli 2009). G‐CSF induced improvements in functional outcome appeared to be preserved in aged stroke rats (Popa‐Wagner 2010) and no deleterious effects were seen with co‐administration of thrombolysis in one study (Kollmar 2010). Although G‐CSF increases total leukocyte counts, there was no evidence of neutrophils infiltrating the stroke lesion, important since this might lead to microvessel occlusion and the release of free radicals and interleukins (Schabitz 2003). G‐CSF improved sensorimotor recovery in a rat model of cerebral haemorrhage (Park 2005) and in vitro can protect human cerebral neurons from ischaemia (Jung 2006). G‐CSF is a candidate treatment for stroke (Schneider 2005b) and has been assessed in phase II and III clinical trials.

GM‐CSF can be used to mobilise stem cells (CD34+) and activate macrophages, and has been shown to induce vascular proliferation. GM‐CSF improved collateral flow in people with coronary artery disease (Seiler 2001). In people with stroke, baseline GM‐CSF levels have been seen to be higher when compared with control, but no correlation has been found with clinical or neurological outcome (Navarro‐Sobrino 2009). Pre‐clinical studies have found that GM‐CSF stimulates arteriogenesis, improves cerebral blood flow (Buschmann 2003) and protects against haemodynamic injury in a rat model of cerebral artery occlusion (Schneeloch 2004). Intra‐carotid injection of GM‐CSF increased numbers of activated microglial cells and protected against neuronal apoptosis after transient middle cerebral artery ischaemia in rats (Nakagawa 2006); GM‐CSF, given intravenously, crosses the blood‐brain barrier and counteracts programmed cell death (Schabitz 2008); intra‐peritoneal administration decreases infarct volume and improves locomotor recovery in rats with ischaemic stroke (Kong 2009).

M‐CSF (CSF‐1) selectively stimulates the proliferation and differentiation of monocytes, as well as granulocytes and platelets, indirectly through the generation of interleukin‐6 and G‐CSF. M‐CSF has also been reported to prevent the progression of atherosclerosis. Serum levels of M‐CSF were elevated in people with previous cerebral infarction compared with healthy people (Suehiro 1999). In vitro, M‐CSF is neuroprotective, inhibiting excitotoxic neuronal apoptosis (Vincent 2002). In mice, recombinant M‐CSF increased neuronal survival and reduced the size of the cerebral infarct (Berezovskaya 1996).

Why it is important to do this review

The physiological actions of CSFs and positive data relating to their use in experimental stroke justify the assessment of recombinant haemopoietic growth factors in clinical stroke. This review reports the effects of CSFs in people with acute or subacute stroke.

Objectives

Hypothesis

Colony stimulating factors (haemopoietic growth factors) may improve functional outcome after ischaemic or haemorrhagic stroke.

Aims

To assess:

the safety and efficacy of CSFs in people with acute or subacute ischaemic or haemorrhagic stroke;

the effect of CSFs on circulating stem and blood cell counts.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

Unconfounded randomised controlled trials.

Types of participants

People with recent (within 30 days of onset) ischaemic or haemorrhagic stroke. This time period allowed us to include studies investigating either acute neuroprotection (for example, through possible anti‐inflammatory or anti‐apoptotic effects) or recovery enhancement (for example, through putative stem cell‐mediated events).

Types of interventions

We considered unconfounded randomised trials of:

stem cell factor (SCF) or analogue versus control;

erythropoietin (EPO) or analogue versus control;

granulocyte colony stimulating factor (G‐CSF) or analogue versus control;

granulocyte‐macrophage colony stimulating factor (GM‐CSF) or analogue versus control;

macrophage‐colony stimulating factor (M‐CSF, CSF‐1) or analogue versus control; and

thrombopoietin (TPO) or analogue versus control.

We excluded trials involving combination therapies since it would not be clear which drug was responsible for any effects observed.

Types of outcome measures

Primary outcomes

Functional outcome at end of follow‐up, assessed as combined death or dependency/disability (using scales including the modified Rankin Scale and Barthel Index).

Secondary outcomes

At end of treatment: death, impairment (using a stroke severity scale, for example the Scandinavian Stroke Scale (SSS) or the National Institute of Health Stroke Scale (NIHSS)), deterioration (death or worsening in stroke severity scale), extension or recurrence, number of people with a serious adverse event, number of people with an infection and stroke lesion volume.

At end of follow‐up: death.

Haematology measures (during or soon after treatment): CD34+ count; red cell count (RCC); white cell count (WCC); platelet count (PC).

Search methods for identification of studies

See the 'Specialized register' section in the Cochrane Stroke Group module. We searched for trials in all languages and arranged translation of articles if necessary.

Electronic searches

We searched the Cochrane Stroke Group Trials Register, which was last searched by the Managing Editor in September 2012. In addition, we performed electronic searches of MEDLINE (1985 to September 2012) (Appendix 1), EMBASE (1985 to September 2012) (Appendix 1), the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) (The Cochrane Library 2012, Issue 4) (Appendix 2) and Science Citation Index (1985 to September 2012). These searches commenced from 1985, the date when EPO (the first recombinant CSF) became available.

In September 2012, we also searched all major registries including ClinicalTrials.gov (www.clinicaltrials.gov), Stroke Trials Registry (www.strokecenter.org/trials), Current Controlled Trials (www.controlled‐trials.com), WHO International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (www.who.int/ictrp/en), Australian New Zealand Clinical Trials Registry (www.anzctr.org.au) and the UK Clinical Research Network Study Portfolio (http://public.ukcrn.org.uk/search).

Searching other resources

We contacted the manufacturers of SCF, EPO, G‐CSF, GM‐CSF, M‐CSF/CSF‐1 and TPO for the first version of this review (2006) and we contacted the manufacturer of carbamylated erythropoietin (CEPO) (H Lundbeck A/S) in 2011. We also contacted the principal investigators of any newly identified trials (last approach April 2012). We searched the reference lists of relevant articles and clinical reviews of these colony stimulating factors.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

Two review authors (TE and NS) screened the titles and abstracts of the records obtained from the electronic searches and excluded obviously irrelevant articles. We then obtained the full text of the remaining papers and two authors (TE and NS) assessed these for inclusion based on the criteria detailed previously. These two review authors resolved any disagreements by discussion and consultation with a third review author (PB) if necessary.

Data extraction and management

We (TE, NS) independently extracted data from publications on quality parameters (as above), drug, dose, route and timing, the numbers of events or status at the end of treatment and the end of follow‐up (including death and dependency), and haematological measures. If necessary, we sought additional information from the chief investigators of identified trials and pharmaceutical companies.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

We assessed the risk of bias of included studies using the 'Risk of bias' methodology described in Chapter 8 of the Cochrane Handbook of Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Cochrane Handbook 2011). We assessed the methodological quality of trials, determining methods of randomisation, concealment of allocation, blinding of outcome assessment, analysis by intention‐to‐treat (ITT) and participants lost to follow‐up.

Measures of treatment effect

We defined the primary outcome to be poor if there was a modified Rankin Score score greater than 2 (eight of nine trials) or a Barthel Index score less than 60 (one trial, Shyu 2006). Early neurological impairment included data collected between three and 10 days post randomisation and data extracted on mortality was defined as early (within 14 days of randomisation) or 'end of trial'.

Unit of analysis issues

To enable comparison of neurological impairment, we converted data in one trial (STEMS‐1 2006) from the Scandinavian Neurological Stroke Score to the National Institutes of Health Stroke Score using a published formula (Gray 2009).

Dealing with missing data

We analysed data by ITT where available, where the ITT population consisted of participants who were randomised, took at least one dose of the assigned study medication, and provided at least one post baseline assessment. We sought missing or additional data directly from the trial authors.

Assessment of heterogeneity

We tested for heterogeneity using the I2 statistic, and calculated a weighted estimate of the typical treatment effect across trials. We used random‐effects models since we expected between‐trial sources of heterogeneity, for example, due to biological differences in CSFs, and clinical and statistical differences in the trials.

Assessment of reporting biases

We did not assess reporting bias using funnel plots due to the small number of included trials.

Data synthesis

We determined treatment effects using the odds ratio (OR) for dichotomous data and mean difference (MD) or standardised mean difference (SMD) for continuous data. We used RevMan 5.2 for data entry and analysis (RevMan 2012).

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

We did not perform subgroup analysis as there were not enough meaningful data.

Sensitivity analysis

We did not perform an intended sensitivity analysis assessing the primary outcome in high‐quality trials alone since data were only available for three small EPO trials and eight small G‐CSF trials.

Results

Description of studies

Results of the search

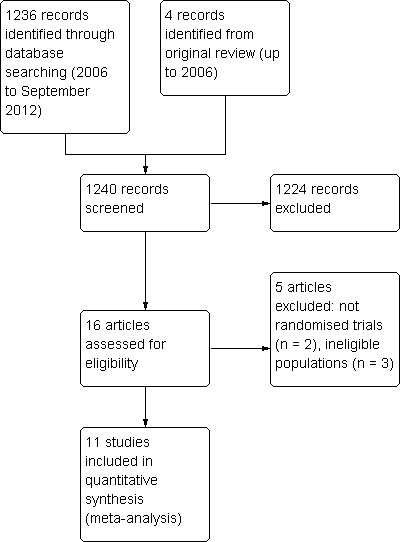

From 1236 records identified, 11 studies were appropriate for inclusion and we excluded five studies (Figure 1). All studies were published in English.

1.

Trial identification process

Included studies

Erythropoietin

We identified three completed trials of EPO. The first involved 40 participants with hyperacute ischaemic stroke (less than seven hours since stroke onset) (Ehrenreich 2002). We excluded data from 13 participants treated in an uncontrolled phase of this study. A further phase III trial of EPO included 522 people with middle cerebral artery ischaemic stroke within six hours of onset (Ehrenreich 2009). A third trial assessing EPO randomised 220 people with ischaemic stroke within 48 hours of symptom onset (Yip 2011).

Granulocyte colony stimulating factor

We found eight completed trials of G‐CSF (AXIS‐1 2010; AXIS‐2 2012; Prasad 2011; Shyu 2006; STEMS‐1 2006; STEMS‐2 2012; STEMTHER 2011; Zhang 2006): Shyu 2006 recruited 10 participants within seven days of ischaemic stroke; STEMS‐1 2006 involved 36 participants from seven to 30 days post ischaemic stroke; STEMS‐2 2012 recruited 60 participants from three to 30 days post ischaemic or haemorrhagic stroke; Zhang 2006 involved 45 participants within seven days of ischaemic stroke (information available in abstract form only); AXIS‐1 2010 recruited 44 participants within 12 hours of onset of ischaemic stroke; AXIS‐2 2012 involved 328 participants within nine hours of onset of ischaemic stroke; STEMTHER 2011 involved 20 participants randomised within 48 hours of ischaemic stroke; and Prasad 2011 recruited 10 participants within seven days of stroke onset.

Other CSFs

We did not identify any completed or ongoing studies of SCF, GM‐CSF, M‐CSF or TPO in people with stroke.

Excluded studies

Erythropoietin

We excluded two trials assessing combined therapy of EPO and human chorionic gonadotrophin (hCG) (REGENESIS CA; REGENESIS‐LED). REGENESIS CA was terminated and no results are available. REGENESIS‐LED is available in abstract form only: due to financial constraints, recruitment was reduced to 96 participants from 18 Indian sites. In this dose‐escalation trial, participants were randomised to active:placebo in a 3:1 ratio. There were eight deaths in total (of unclear group distribution) and no difference in the primary outcome (change in NIHSS) was evident between groups after 90 days' follow‐up. We excluded BETAS 2010 as it was an open‐label, non‐controlled trial assessing the combination of EPO and beta‐hCG.

Granulocyte colony stimulating factor

We excluded Boy 2011 as it was not a randomised trial. We also excluded a trial assessing G‐CSF in chronic stroke (Floel 2011).

Ongoing studies

Erythropoietin

Two small safety trials of carbamylated erythropoietin, a derivative of EPO without haematopoietic activity, have been completed (CEPO 2008; CEPO 2009) but their data have not yet been reported.

Granulocyte colony stimulating factor

STEMS‐3, assessing G‐CSF in 60 people with motor impairment for more than 90 days due to stroke, is ongoing. Three other safety trials of G‐CSF in acute or subacute stroke are ongoing: GENESIS‐2 (n = 100); GIST 2008 (n = 20) and Nilanont 2010 (n = 36).

Studies awaiting classification

Erythropoietin

Two studies await classification, one assessing EPO in 40 people with putaminal haemorrhage (Farhoudi 2010) and another evaluating EPO in 90 people with ischaemic stroke (Kalra 2012).

Risk of bias in included studies

Allocation

The three published trials of EPO (Ehrenreich 2002; Ehrenreich 2009; Yip 2011) and five of the G‐CSF trials (AXIS‐1 2010; AXIS‐2 2012; STEMS‐1 2006; STEMS‐2 2012; Zhang 2006) provided adequate allocation concealment. Three studies were open‐label, randomised trials with no placebo (Prasad 2011; Shyu 2006; STEMTHER 2011).

Blinding

The three published trials of EPO (Ehrenreich 2002; Ehrenreich 2009; Yip 2011) and five of the G‐CSF trials (AXIS‐1 2010; AXIS‐2 2012; STEMS‐1 2006; STEMS‐2 2012; Zhang 2006) were triple‐blind, with treatment compared with placebo; measures were made blinded to treatment assignment. Shyu 2006 was single‐blind (blinded outcome assessments) whereas both the participants and the investigator were unblinded in Prasad 2011 and STEMTHER 2011.

Incomplete outcome data

Yip 2011 excluded 24% of participants from the analysis due to protocol violations and 5% were lost to follow‐up.

Selective reporting

Selective reporting was not evident in the majority of included trials. Yip 2011 provided per‐protocol analysis only. Zhang 2006 was abstract data (and direct author contact) only.

Other potential sources of bias

In three trials (AXIS‐1 2010; AXIS‐2 2012; Ehrenreich 2009), investigators held a patent on the effects of the respective colony stimulating factor in the treatment of stroke. Sample size justification was given in three trials (Ehrenreich 2009; STEMS‐2 2012; Yip 2011).

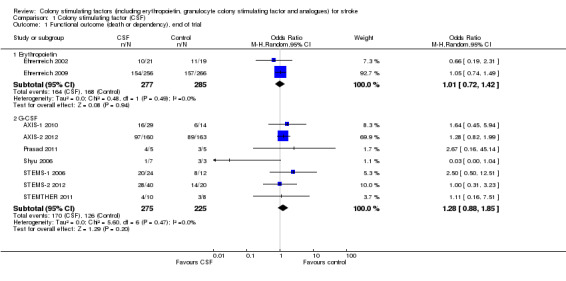

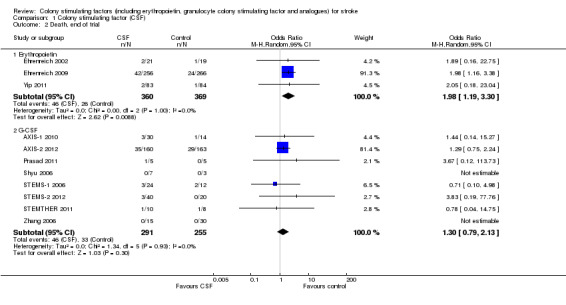

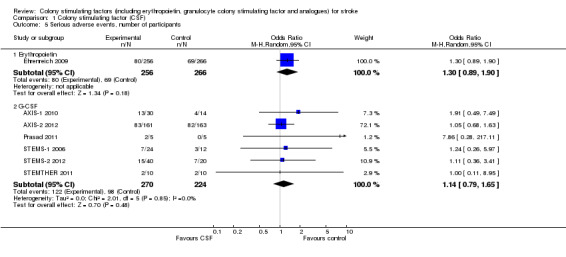

Effects of interventions

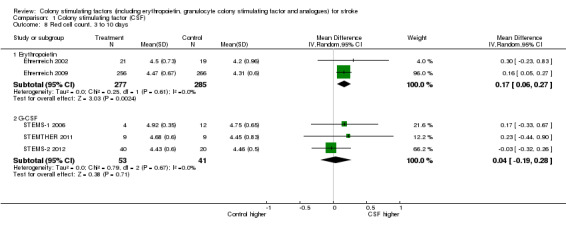

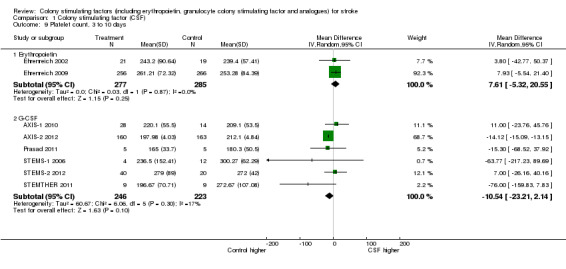

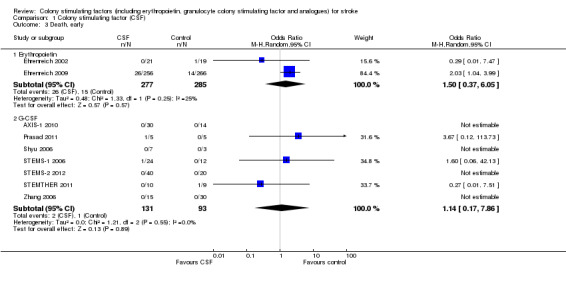

Erythropoietin (EPO) non‐significantly reduced combined death or dependency, as measured by the modified Rankin Scale, in two trials (Ehrenreich 2002; Ehrenreich 2009) (Analysis 1.1) including 562 participants, but with 92% of the weight resulting from the later phase III trial. Conversely, death by end of the trial was increased two‐fold (odds ratio (OR) 1.98, 95% confidence interval (CI) 1.17 to 3.33, P = 0.01; Analysis 1.2). There was also a non‐significant trend towards an increased number of serious adverse events in the EPO group (Analysis 1.5). EPO significantly increased red cell count (Analysis 1.8) with no effect on platelet or white cell count (Analysis 1.7; Analysis 1.9). EPO had no discernable effect on stroke infarct volume.

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Colony stimulating factor (CSF), Outcome 1 Functional outcome (death or dependency), end of trial.

1.2. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Colony stimulating factor (CSF), Outcome 2 Death, end of trial.

1.5. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Colony stimulating factor (CSF), Outcome 5 Serious adverse events, number of participants.

1.8. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Colony stimulating factor (CSF), Outcome 8 Red cell count, 3 to 10 days.

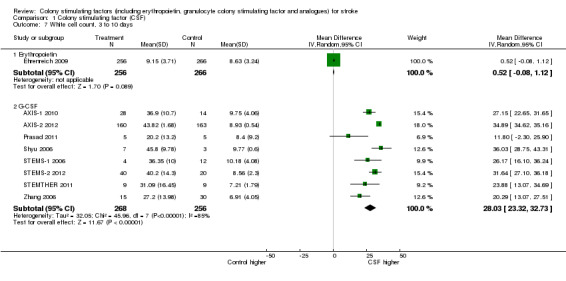

1.7. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Colony stimulating factor (CSF), Outcome 7 White cell count, 3 to 10 days.

1.9. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Colony stimulating factor (CSF), Outcome 9 Platelet count, 3 to 10 days.

Granulocyte colony stimulating factor (G‐CSF) did not significantly alter combined death or dependency at end of trial (Analysis 1.1), early death (Analysis 1.3) or end of trial death (Analysis 1.2). A trend to a reduction in early impairment as measured by the National Institute of Health Stroke Scale (NIHSS) was seen in G‐CSF treated participants (Analysis 1.4). G‐CSF was associated with a non‐significant increase in serious adverse events, but had no effect on the rate of infection (Analysis 1.6). It increased white cell (Analysis 1.7) and CD34+ count (Analysis 1.10) but had no effect on other blood count variables (red blood cells, platelets). It also had no discernable effect on stroke infarct volume (Analysis 1.12) or serum levels of S100ß (Analysis 1.11).

1.3. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Colony stimulating factor (CSF), Outcome 3 Death, early.

1.4. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Colony stimulating factor (CSF), Outcome 4 Early Impairment, NIHSS.

1.6. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Colony stimulating factor (CSF), Outcome 6 Infection.

1.10. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Colony stimulating factor (CSF), Outcome 10 CD34+ count, 5 to 10 days.

1.12. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Colony stimulating factor (CSF), Outcome 12 Infarct volume, post treatment.

1.11. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Colony stimulating factor (CSF), Outcome 11 Serum S100‐ß, 7 to 10 days.

Discussion

Summary of main results

Although there are several types of bone marrow‐modulating colony stimulating factors (CSFs), only erythropoietin (EPO) and granulocyte colony stimulating factor (G‐CSF) have been studied in completed trials in people with acute or subacute stroke. Most studies were small, studying safety, except for one phase III trial of EPO (Ehrenreich 2009) and a phase II/III trial of G‐CSF (AXIS‐2 2012). EPO did not show a significant effect on combined death and dependency but there was an increase in death rate. The trial authors suggest that mortality was related to the abnormally high number of recruits receiving thrombolysis (63%), of which half demonstrated contraindications to recombinant tissue plasminogen activator (rt‐PA) administration. Although no particular mechanism of death was apparent, an EPO/rt‐PA interaction could not be ruled out. Additionally, the significant rise in red cell count caused by EPO might be a contributing factor.

Non‐haematopoietic derivatives of EPO, which do not increase red cell count and haematocrit (and a subsequent procoagulant state), are in clinical development: two trials of carbamylated EPO have been completed and their results are awaited (CEPO 2008; CEPO 2009).

G‐CSF did not significantly alter functional outcome or death, although its administration was associated with a non‐significant reduction in early impairment. G‐CSF was well tolerated in all eight trials and appeared to be safe, although it significantly increased white cell count.

Overall completeness and applicability of evidence

It is apparent that at least two paradigms are being studied with CSFs in the treatment of stroke. First, CSFs such as EPO and G‐CSF are neuroprotective in animal models of acute stroke and this potential mechanism has been investigated in people with acute stroke (AXIS‐1 2010; AXIS‐2 2012; Ehrenreich 2002; Ehrenreich 2009). Second, stem cell mobilising CSFs (e.g. SCF, G‐CSF and GM‐CSF) could contribute to brain repair through neurogenic‐related mechanisms, again as has been seen in experimental models of stroke: six trials have investigated this approach (Prasad 2011; Shyu 2006; STEMS‐1 2006; STEMS‐2 2012; STEMTHER 2011; Zhang 2006). All of these studies focus on recent stroke. Floel 2011 was a trial of G‐CSF in chronic stroke (n = 41) reporting safe and feasible administration. Another trial in chronic stroke is ongoing (STEMS‐3).

Quality of the evidence

All included studies were randomised controlled trials and most were small safety studies. Two studies were of poor quality (unblinded) (Prasad 2011; STEMTHER 2011) but their contribution to the weight of the evidence was minimal (n = 28 of 1275 participants).

Potential biases in the review process

We used an extensive search strategy and it is unlikely that any high‐quality randomised controlled trials were missed. It is feasible, however, that we did not identify small trials published in less well‐known journals. Further bias is introduced from clinical heterogeneity that exists between the studies (e.g. drug dose, timing of outcome measures). This was accounted for, in part, by use of a random‐effects model.

Agreements and disagreements with other studies or reviews

There are no other systematic reviews assessing colony stimulating factors in stroke.

Authors' conclusions

Implications for practice.

No conclusive evidence suggests that any type of colony stimulating factor (CSF) should be used in the routine management of stroke.

Implications for research.

The completed trials provide evidence for the practicality and feasibility of administering CSFs. However, questions have arisen regarding the safety of erythropoietin (EPO) in the context of acute stroke, especially in people who have received thrombolysis (Ehrenreich 2009). The mechanism explaining an EPO/rt‐PA interaction is unclear: an increase in blood brain barrier permeability may contribute (Zechariah 2010) but further experimental work in stroke models is required. Further clinical studies using EPO in stroke should be avoided at least until safety aspects are explored further experimentally. Whether this applies to non‐haematopoietic derivatives of EPO (e.g. carbamylated EPO) is unclear, and results of CEPO 2008 and CEPO 2009 are awaited.

The mechanisms by which CSFs might work in acute or subacute stroke are unclear. Although CSFs could be neuroprotective, reductions in stroke lesion size were not seen in trials of EPO or granulocyte colony stimulating factor (G‐CSF). This may reflect the difficulties in translating experimental stroke models into clinical medicine with animal models not being sufficiently representative of human stroke (STAIR 1999). G‐CSF may also be neuroreparative since its administration in the sub‐acute period was associated with a non‐significant reduction in early impairment. Similar results have been seen in preclinical studies and mobilised stem cells could enhance neurogenesis and angiogenesis. One clinical trial of G‐CSF attempted to track the migration of CD34+ cells into the brain (STEMS‐2 2012).

Further studies need to address mechanisms by which CSFs might work, for example, using alternative cell labelling techniques or cerebral perfusion imaging. Understanding potential mechanisms of action will help investigators decide when to administer treatment relative to stroke onset. Whether CSFs aid recovery in chronic stroke also needs to be addressed, as is being done in one trial (STEMS‐3).

Feedback

Potential data error, 28 August 2012

Summary

In Forest Plot 1.1, for the Shyu study, the figures are 0/7 and 3/3. It is not clear from the review exactly which outcome this relates to in the Shyu 2006 paper (Shyu WC et al. Canadian Medical Association Journal 2006;174:927–33). However, if the information comes from Table 2 of the Shyu paper, then it looks as if the numbers should be 1/7 and 3/3.

This potential error will not change the conclusions, but as it involved the primary outcome of the review, I thought I should make you aware of it.

Reply

The error has been corrected in this version of the review.

Contributors

Steff Lewis (commenter): I have modified the conflict of interest statement below to declare my interests: I am not doing this on behalf of any company. The finding arose as part of a methodology project funded by the UK MRC.

Tim England (responder)

What's new

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 16 November 2012 | New search has been performed | We have added seven trials to this updated review. A total of 11 studies and 1275 participants are now included |

| 16 November 2012 | New citation required but conclusions have not changed | All literature searches have been updated and new data included. The conclusions are unchanged |

| 16 November 2012 | Feedback has been incorporated | The Feedback received in August 2012 has been incorporated and the data updated |

History

Protocol first published: Issue 2, 2005 Review first published: Issue 3, 2006

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 10 September 2012 | Feedback has been incorporated | Feedback has been received for this review; the authors are currently updating the review and will respond to the feedback in the next version |

| 22 October 2008 | Amended | Contact details updated |

| 4 August 2008 | Amended | Converted to new review format |

| 9 November 2006 | New search has been performed | Three trials have been added as included studies in this updated review |

Acknowledgements

We thank the authors of the completed and ongoing trials for sharing information on their studies. We also thank the referees for commenting on this review.

Appendices

Appendix 1. MEDLINE and EMBASE search strategy

MEDLINE and EMBASE (Ovid)

Hematopoietic Cell Growth Factors/

colony‐stimulating factors/ or exp colony‐stimulating factors, recombinant/ or exp erythropoietin/ or exp granulocyte colony‐stimulating factor/ or exp granulocyte‐macrophage colony‐stimulating factor/ or interleukin‐3/ or macrophage colony‐stimulating factor/

Stem Cell Factor/

Thrombopoietin/

(haematopoieti$ or hematopoieti$ or erythropoietin or epoetin or darbepoetin or colony stimulating factor or colony‐stimulating factor or interleukin‐3 or filgrastim or thrombopoietin or stem cell factor).tw.

(G‐CSF or M‐CSF or GM‐CSF or CSF‐1 or HGFs or IL‐3 or MGI‐1 or TPO or SCF or E21R).tw.

or/1‐6

cerebrovascular disorders/ or exp basal ganglia cerebrovascular disease/ or exp brain ischemia/ or exp carotid artery diseases/ or exp cerebrovascular accident/ or exp hypoxia‐ischemia, brain/ or exp intracranial arterial diseases/ or intracranial arteriovenous malformations/ or exp "intracranial embolism and thrombosis"/ or exp intracranial hemorrhages/ or vasospasm, intracranial/ or vertebral artery dissection/

((brain or cerebr$ or cerebell$ or vertebrobasil$ or hemispher$ or intracran$ or intracerebral or infratentorial or supratentorial or middle cerebr$ or mca$ or anterior circulation) adj5 (isch?emi$ or infarct$ or thrombo$ or emboli$ or occlus$ or hypoxi$)).tw.10. ((brain$ or cerebral or cerebell$ or intracranial or subarachnoid) adj5 (haemorrhage or hemorrhage or hematoma or haematoma or bleed$ or aneurysm)).tw.

or/8‐10

7 and 11

limit 11 to human

limit 12 to clinical trials

Appendix 2. CENTRAL search strategy

MeSH descriptor: [Hematopoietic Cell Growth Factors] explode all trees

MeSH descriptor: [Stroke] explode all trees

(brain or cerebr$ or cerebell$ or vertebrobasil$ or hemispher$ or intracran$ or intracerebral or infratentorial or supratentorial or middle cerebr$ or mca$ or anterior circulation) near/5 (isch?emi$ or infarct$ or thrombo$ or emboli$ or occlus$ or hypoxi$ or haemorrhage or hemorrhage or hematoma or haematoma or bleed$ or aneurysm):ti,ab,kw

(#2 or #3) and #1

Data and analyses

Comparison 1. Colony stimulating factor (CSF).

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Functional outcome (death or dependency), end of trial | 9 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 1.1 Erythropoietin | 2 | 562 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.01 [0.72, 1.42] |

| 1.2 G‐CSF | 7 | 500 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.28 [0.88, 1.85] |

| 2 Death, end of trial | 11 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 2.1 Erythropoietin | 3 | 729 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.98 [1.19, 3.30] |

| 2.2 G‐CSF | 8 | 546 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.30 [0.79, 2.13] |

| 3 Death, early | 9 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 3.1 Erythropoietin | 2 | 562 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.50 [0.37, 6.05] |

| 3.2 G‐CSF | 7 | 224 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.14 [0.17, 7.86] |

| 4 Early Impairment, NIHSS | 6 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 4.1 Erythropoietin | 1 | 40 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐2.20 [‐10.01, 5.61] |

| 4.2 G‐CSF | 5 | 203 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐0.40 [‐1.82, 1.01] |

| 5 Serious adverse events, number of participants | 7 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 5.1 Erythropoietin | 1 | 522 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.30 [0.89, 1.90] |

| 5.2 G‐CSF | 6 | 494 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.14 [0.79, 1.65] |

| 6 Infection | 6 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 6.1 G‐CSF | 6 | 494 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.92 [0.51, 1.68] |

| 7 White cell count, 3 to 10 days | 9 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 7.1 Erythropoietin | 1 | 522 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 0.52 [‐0.08, 1.12] |

| 7.2 G‐CSF | 8 | 524 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 28.03 [23.32, 32.73] |

| 8 Red cell count, 3 to 10 days | 5 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 8.1 Erythropoietin | 2 | 562 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 0.17 [0.06, 0.27] |

| 8.2 G‐CSF | 3 | 94 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 0.04 [‐0.19, 0.28] |

| 9 Platelet count, 3 to 10 days | 8 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 9.1 Erythropoietin | 2 | 562 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 7.61 [‐5.32, 20.55] |

| 9.2 G‐CSF | 6 | 469 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐10.54 [‐23.21, 2.14] |

| 10 CD34+ count, 5 to 10 days | 5 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 10.1 G‐CSF | 5 | 150 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 1.81 [1.06, 2.57] |

| 11 Serum S100‐ß, 7 to 10 days | 2 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

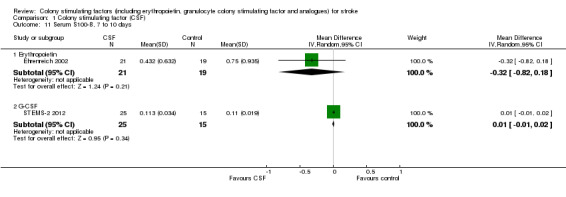

| 11.1 Erythropoietin | 1 | 40 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐0.32 [‐0.82, 0.18] |

| 11.2 G‐CSF | 1 | 40 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 0.01 [‐0.01, 0.02] |

| 12 Infarct volume, post treatment | 5 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 12.1 Erythropoietin | 2 | 485 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐6.19 [‐26.45, 14.08] |

| 12.2 G‐CSF | 3 | 68 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐1.68 [‐34.31, 30.95] |

Characteristics of studies

Characteristics of included studies [ordered by study ID]

AXIS‐1 2010.

| Methods | National, multicentre, randomised, placebo‐controlled, dose‐escalation study | |

| Participants | 44 participants (6 German centres) with acute (< 12 hours of onset) ischaemic MCA‐territory stroke and diffusion/perfusion 'mismatch' on MRI | |

| Interventions | G‐CSF, dose‐escalation (4 levels, cumulative dose range between 30 µg/kg and 180 µg/kg over 3 days) versus control | |

| Outcomes | (1) Thromboembolic complications by day 4 (2) Severe infection, SAEs, function (NIHSS, mRS, BI) at 4 weeks and day 90, lesion growth on MRI at day 90 |

|

| Notes | Started December 2004 | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | Central computer‐generated allocation |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | Computer‐generated randomisation in multicentre study |

| Blinding (performance bias and detection bias) All outcomes | Low risk | Adequate |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Low risk | 1 participant replaced when severe violation of inclusion criteria noted. No losses to follow‐up |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Unclear risk | All outcomes in the methods are reported. It would be difficult to rule out |

| Other bias | High risk | Investigators are inventors on patent applications claiming the use of granulocyte colony stimulating factor for the treatment of stroke. Funded by a pharmaceutical company |

AXIS‐2 2012.

| Methods | Randomised, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled, multicentre trial | |

| Participants | 328 participants (in 51 active centres) with acute (< 9 hours of onset) ischaemic MCA‐territory stroke, DWI lesion > 15 cm3, age < 86 years | |

| Interventions | iv G‐CSF 135 µg/kg over 72 hours (1/3 of the total dose given as a priming dose over 30 minutes) | |

| Outcomes | (1) mRS day 90 (2) NIHSS day 90, infarct growth, adverse events, mortality | |

| Notes | Started August 2009 | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Awaiting publication |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Awaiting publication |

| Blinding (performance bias and detection bias) All outcomes | Unclear risk | Awaiting publication |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Unclear risk | Awaiting publication |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Unclear risk | Awaiting publication |

| Other bias | Unclear risk | Awaiting publication |

Ehrenreich 2002.

| Methods | Double‐blind, placebo‐controlled trial | |

| Participants | 40 participants (1 German centre) with acute (< 8 hours of onset) ischaemic stroke | |

| Interventions | rhEPO 3.3E4 IU iv x 3, or saline placebo | |

| Outcomes | (1) NIHSS, SSS, BI, mRS (day 30) (2) serum (EPO); impairment (NIHSS, SSS); function (BI, mRS); imaging (MRI: DWI, FLAIR); biomarker (S‐100β) | |

| Notes | Started: December 1998 | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Randomised sequence generation but methods unclear |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | Numbered, identical vials prepared by the pharmacist |

| Blinding (performance bias and detection bias) All outcomes | Low risk | Adequate |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Low risk | No losses to follow‐up in primary outcomes (neurological score and functional outcome) |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Unclear risk | All outcomes in the methods are reported. It would be difficult to rule out |

| Other bias | High risk | None reported |

Ehrenreich 2009.

| Methods | Randomised, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled | |

| Participants | 522 participants (German multicentre trial) with acute ischaemic stroke within 6 hours of onset | |

| Interventions | Epoetin‐alpha 40,000 IU iv within 6 hours of symptom onset, at 24 and 48 hours | |

| Outcomes | (1) NIHSS, BI, mRS (day 30 and day 90) (2) Lesion volume (MRI); adverse events | |

| Notes | Start: February 2003 | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | Stratified block randomisation, generated by a random number table |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | Vials containing study drug were numbered and given to a blinded investigator |

| Blinding (performance bias and detection bias) All outcomes | Low risk | Adequate |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Low risk | For missing data (4% lost to follow‐up), functional and neurological outcomes were imputed by using "last observation carried forward". If no post baseline value was available, worst possible outcome was imputed |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | High risk | All outcomes in the methods are reported. Multiple analyses including intention‐to‐treat population, per protocol population and those who received thrombolysis |

| Other bias | High risk | High thrombolysis rates and violation of thrombolysis contraindications potentially influencing the negative outcome of the study. Investigator holds a patent on the use of EPO for treatment of cerebral ischaemia |

Prasad 2011.

| Methods | Randomised, open‐label, parallel group | |

| Participants | 10 participants with acute ischaemic stroke, within 7 days of onset | |

| Interventions | G‐CSF (Filgrastim) 10 µg/kg sc for 5 days | |

| Outcomes | (1) Safety; efficacy (NIHSS, BI, mRS at 1, 6 and 12 months) | |

| Notes | Participants recruited between January and May 2008 | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Computer‐generated randomisation table. Randomisation performed by and independent co‐ordinator |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | High risk | Investigators not blinded to allocation |

| Blinding (performance bias and detection bias) All outcomes | High risk | Unblinded |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Low risk | |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | 2 primary outcomes. All outcomes reported |

| Other bias | Unclear risk | None reported |

Shyu 2006.

| Methods | Single‐blind controlled trial | |

| Participants | 10 participants (1 Taiwanese centre) with acute ischaemic stroke within 7 days of onset | |

| Interventions | G‐CSF (Filgrastim) 15 µg/kg sc for 5 days | |

| Outcomes | (1) NIHSS, ESS, EMS, BI (12months) (2) FDG‐PET | |

| Notes | Start date not reported. No placebo | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | High risk | "The clinician responsible for the patient selected an opaque envelope that contained the treatment assignment. The envelopes were prepared by one person who was responsible for treatment assignment and was unfamiliar with the patients" |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | High risk | Inadequate |

| Blinding (performance bias and detection bias) All outcomes | Low risk | Blinded analysis of data only. Treating clinician and participants unblinded |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Low risk | No losses to follow‐up |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Unclear risk | All outcomes in the methods are reported. It would be difficult to rule out |

| Other bias | Unclear risk | None reported |

STEMS‐1 2006.

| Methods | Double‐blind, placebo‐controlled, dose‐escalation trial | |

| Participants | 36 participants (2 UK centres) with acute ischaemic stroke between 7 and 30 days of onset | |

| Interventions | G‐CSF (Filgrastim) 1 to 10 µg/kg sc for 1 or 5 doses | |

| Outcomes | (1) CD34+ (0 to 10 days) (2) Safety, laboratory and clinical, efficacy, SSS (day 10), BI, mRS (day 90) | |

| Notes | Started: August 2003 | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | Computerised randomisation with minimisation for baseline prognostic values |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | Adequate |

| Blinding (performance bias and detection bias) All outcomes | Low risk | Investigator, participants and analysis all blinded to treatment |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Low risk | No losses to follow‐up |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | All outcomes in the methods reported |

| Other bias | Low risk | No conflicts of interest |

STEMS‐2 2012.

| Methods | Single‐centre, double‐blind, randomised, placebo‐controlled, phase IIb trial | |

| Participants | 60 participants (1 UK centre), 3 to 30 days post ischaemic or haemorrhagic stroke | |

| Interventions | G‐CSF (Filgrastim) 10 µg/kg versus normal saline sc for 5 days | |

| Outcomes | (1) Serious adverse events (2) Efficacy (SSS, mRS, BI, EADL), lesion volume (MRI) | |

| Notes | Started: July 2007 | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | Computerised randomisation with minimisation for baseline prognostic values |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | Adequate |

| Blinding (performance bias and detection bias) All outcomes | Low risk | Investigator, participants and analysis all blinded to treatment |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Low risk | No losses to follow‐up |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | All outcomes reported |

| Other bias | Low risk | No conflicts of interest |

STEMTHER 2011.

| Methods | Prospective, single‐centre, unmasked, randomised controlled trial | |

| Participants | 20 participants (1 Russian centre) < 48 hours post ischaemic stroke | |

| Interventions | G‐CSF (Leukostim) 10 µg/kg for 5 days versus control (no placebo) | |

| Outcomes | (1) Safety (2) Efficacy (NIHSS, mRS, BI), lesion volume (MRI) and laboratory measures | |

| Notes | Start date: June 2007 | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | High risk | Investigators prepared opaque envelopes for the treating physician to select |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | High risk | Randomisation results were known to the examining physician |

| Blinding (performance bias and detection bias) All outcomes | High risk | Participants and physician unblinded |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | High risk | 2 losses to follow‐up in the placebo group not clearly addressed in the results |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | All outcomes reported |

| Other bias | High risk | No conflicts of interest reported |

Yip 2011.

| Methods | Prospective, double‐blind, randomised, placebo‐controlled trial | |

| Participants | 220 participants with acute ischaemic stroke (NIHSS > 2) | |

| Interventions | 5000 IU EPO or normal saline sc at 48 and 72 hours post ischaemic stroke | |

| Outcomes | (1) Safety and efficacy (combined outcome: recurrent stroke and death) (2) EPC levels, composite endpoint (NIHSS > 8, recurrent stroke or death), NIHSS, mRS | |

| Notes | Start date: October 2008 | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Not described |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | "The medication was given by a clinician blinded to the patients' clinical condition" |

| Blinding (performance bias and detection bias) All outcomes | Low risk | A neurologist blinded to treatment allocation assessed the outcomes |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | High risk | 24% of randomised participants excluded for protocol violations |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | High risk | Analysis performed per protocol and 5% loss to follow‐up |

| Other bias | Unclear risk | Not entered onto a trial register until 10 months after the inclusion of the last participant |

Zhang 2006.

| Methods | Double‐blind, placebo‐controlled trial | |

| Participants | 45 participants (1 Chinese centre) with acute ischaemic stroke within 7 days | |

| Interventions | G‐CSF (Filgrastim) 2 µg/kg sc for 5 days | |

| Outcomes | (1) NIHSS (2) WCC (3) CD34+ cell count | |

| Notes | Started: February 2005 | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | Computerised randomisation |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | Adequate |

| Blinding (performance bias and detection bias) All outcomes | Low risk | Double‐blind trial |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Unclear risk | Abstract data only |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Unclear risk | Abstract data only |

| Other bias | Unclear risk | Abstract data only |

BI: Barthel index CD34+: CD34+ cell count DWI: diffusion weighted imaging EADL: extended activities of daily living EMS: European Motor Scale EPC: endothelial progenitor cells ESS: European Stroke Scale EPO: erythropoietin FDG‐PET: fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography FLAIR: fluid‐attenuated inversion recovery G‐CSF: granulocyte colony stimulating factor iv: intravenous MCA: middle cerebral artery MRI: magnetic resonance imaging mRS: modified Rankin Scale NIHSS: National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale rhEPO: recombinant human erythropoietin SAE: severe adverse event sc: subcutaneous SSS: Scandinavian Stroke Scale WCC: white cell count

Characteristics of excluded studies [ordered by study ID]

| Study | Reason for exclusion |

|---|---|

| BETAS 2010 | Not a randomised controlled trial |

| Boy 2011 | Not a randomised controlled trial |

| Floel 2011 | Assessment of G‐CSF in participants with chronic stroke |

| REGENESIS CA | Combined treatment: HCG and epoetin alpha |

| REGENESIS‐LED | Combined treatment: HCG and epoetin alpha |

G‐CSF: granulocyte colony stimulating factor HCG: human chorionic gonadotrophin

Characteristics of studies awaiting assessment [ordered by study ID]

Farhoudi 2010.

| Methods | Randomised trial |

| Participants | 40 participants with putaminal haemorrhage |

| Interventions | Intravenous EPO 5000 U/kg, "or not" |

| Outcomes | NIHSS Score |

| Notes | World Stroke Conference 2010, abstract PO20022 |

Kalra 2012.

| Methods | Randomised trial |

| Participants | 90 participants with ischaemic stroke |

| Interventions | Intravenous EPO 40000 IU given early (1, 3 and 5 days) or late (7, 14 and 21 days) or control |

| Outcomes | Functional recovery and MRI |

| Notes | Trial ID: EUCTR2011‐000123‐33‐GB, URL: https://www.clinicaltrialsregister.eu/ctr‐search/search?query=eudract_number:2011‐000123‐33 |

EPO: erythropoietin MRI: magnetic resonance imaging NIHSS: National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale

Characteristics of ongoing studies [ordered by study ID]

CEPO 2008.

| Trial name or title | Safety study of carbamylated erythropoietin (CEPO) to treat patients with acute ischaemic stroke |

| Methods | Randomised, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled, single‐dose, dose‐escalation study |

| Participants | 16 participants aged 50 to 90 years, within 12 to 48 hours of ischaemic stroke onset |

| Interventions | Dose‐escalation (0.005 µg/kg to 50.0 µg/kg) trial of Lu AA24493 or placebo |

| Outcomes | Safety, National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale and the modified Rankin Scale |

| Starting date | October 2007 |

| Contact information | LundbeckClinicalTrials@lundbeck.com |

| Notes | ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT00756249 Completed but not published |

CEPO 2009.

| Trial name or title | Safety and pharmacokinetic study of carbamylated erythropoietin (CEPO) to treat patients with acute ischaemic stroke |

| Methods | A randomised, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled, dose‐escalation study |

| Participants | Participants aged 50 to 90 years, within 0 to 48 hours of ischaemic stroke onset |

| Interventions | Dose‐escalation (0.005 µg/kg to 50.0 µg/kg) trial of Lu AA24493 or placebo |

| Outcomes | Safety, National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale and the modified Rankin Scale, pharmacokinetics, immunogenicity and biomarkers |

| Starting date | 2009 |

| Contact information | LundbeckClinicalTrials@lundbeck.com |

| Notes | ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT00870844 Ongoing, but not recruiting participants |

GENESIS‐2.

| Trial name or title | G‐CSF employing neuroprotection study for ischaemic stroke ‐ Phase 2 clinical trial (GENESIS‐2) |

| Methods | Randomised trial |

| Participants | 100 participants with ischaemic stroke, age 45 to 80 years, at 24 hours after onset |

| Interventions | Intravenous G‐CSF (75 µg/kg or 150 µg/kg) or placebo (saline), bd for 5 days |

| Outcomes | Safety (leukocyte count, size of spleen), clinical outcome at 3 months after the onset (mRS, BI) |

| Starting date | 1 December 2011 |

| Contact information | Shunya Takizawa, shun@is.icc.u‐tokai.ac.jp |

| Notes | UMIN‐CTR Search Clinical Trials identifier UMIN000006607 |

GIST 2008.

| Trial name or title | Granulocyte‐colony stimulating factor in ischaemic stroke (GIST): a pilot study |

| Methods | Randomised, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled trial |

| Participants | 20 participants, non‐dominant ischaemic stroke (> 3 cm3) with hemiparesis |

| Interventions | G‐CSF 10 µg/kg sc once daily for 4 days, repeated once 6 weeks later, or placebo (normal saline) |

| Outcomes | Safety, feasibility, efficacy |

| Starting date | July 2006 |

| Contact information | Michael Sharma, The Ottawa Hospital, Ottawa, Ontario, Canada, K1Y 4E9 msharma@ottawahospital.on.ca |

| Notes | ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT00809549 |

Nilanont 2010.

| Trial name or title | A randomised, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled trial of granulocyte‐colony stimulating factor (G‐CSF) for the treatment of acute ischaemic stroke |

| Methods | Block randomised according to stroke severity |

| Participants | 36 participants, acute ischaemic stroke within 7 days of stroke onset |

| Interventions | G‐CSF 15 µg/kg sc once daily for 5 days |

| Outcomes | Safety and efficacy |

| Starting date | Unknown |

| Contact information | Nilanont Y, Siriraj Hospital, Mahidol University, Bangkok, Thailand |

| Notes | Presented at World Stroke Congress 2010 |

STEMS‐3.

| Trial name or title | Stem cell Trial of recovery EnhanceMent after Stroke 3 (STEMS‐3) |

| Methods | Randomised, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled trial |

| Participants | 60 participants with motor impairment (arm or leg) with residual disability (mRS > 1) due to stroke > 90 days post onset |

| Interventions | G‐CSF (sc 10 µg/kg for 5 days) or placebo |

| Outcomes | Primary: tolerability, feasibility, acceptability, adverse events Secondary: haematological (FBC, WCC, CD34, PLT), post‐therapy intervention (day 45 and end of follow‐up day 90), motor function, change in dependency (mRS shift), change in disability (change in BI), quality of life (EuroQoL), care giver burden |

| Starting date | November 2011 |

| Contact information | nikola.sprigg@nottingham.ac.uk |

| Notes |

bd: twice daily BI: Barthel index EPO: erythropoietin FBC: full blood count G‐CSF: granulocyte colony stimulating factor mRS: modified Rankin Scale NIHSS: National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale PLT: platelet count SAE: serious adverse event SNSS: Scandinavian Neurological Stroke Scale sc: subcutaneous WCC: white cell count

Contributions of authors

PB conceived and wrote the first version of the review, performed electronic searches, reviewed this version and is the guarantor. TE and NS updated this version of the review and performed searches.

Sources of support

Internal sources

No sources of support supplied

External sources

The Stroke Association, UK.

BUPA Foundation, UK.

The Medical Research Council, UK.

Declarations of interest

The authors (PB, NS, TE) performed two phase II trials of G‐CSF (STEMS‐1 2006; STEMS‐2 2012) funded by The Stroke Association and UK Medical Research Council. NS and PB are doing a trial of G‐CSF in chronic stroke (STEMS‐3). PB acted as a consultant to Axaron/Sygnis (who are developing EPO) and was a member of the Steering Committee for Lundbeck's trials of carbamylated EPO; no consultancy fees from Axaron or Lundbeck were used in any way for the development of this review, and neither company had any influence over the initiation, planning or production of the review, or interpretation of data.

New search for studies and content updated (no change to conclusions), comment added to review

References

References to studies included in this review

AXIS‐1 2010 {published and unpublished data}

- Schabitz WR, Laage R, Vogt G, Koch W, Kollmar R, Schwab S, et al. AXIS: a trial of intravenous granulocyte colony‐stimulating factor in acute ischemic stroke. Stroke 2010;41:2545‐51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

AXIS‐2 2012 {unpublished data only}

- AXIS 2 investigators. AX200 for the treatment of acute ischemic stroke. International Stroke Conference, New Orleans, USA February 2012.

Ehrenreich 2002 {published data only}

- Ehrenreich H, Hasselblatt M, Dembowski C, Cepek L, Lewczuk P, Stiefel M, et al. Erythropoietin therapy for acute stroke is both safe and beneficial. Molecular Medicine 2002;8:495‐505. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Ehrenreich 2009 {published data only}

- Ehrenreich H, Weissenborn K, Prange H, Schneider D, Weimar C, Wartenberg K, the EPO Stroke Trial Group. Recombinant human erythropoietin in the treatment of acute ischaemic stroke. Stroke 2009;40(12):647‐56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Prasad 2011 {published data only}

- Prasad K, Kumar A, Sahu JK, Srivastava MV, Mohanty S, Bhatia R, et al. Mobilization of stem cells using G‐CSF for acute ischemic stroke: a randomized controlled, pilot study. Stroke Research and Treatment 2011 Oct 11 [Epub ahead of print]. [DOI: 10.4061/2011/283473] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

Shyu 2006 {published data only}

- Shyu WC, Lin SZ, Lee CC, Liu DD, Li H. Granulocyte colony‐stimulating factor for acute ischemic stroke: a randomized controlled trial. Canadian Medical Association Journal 2006;174:927‐33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

STEMS‐1 2006 {published and unpublished data}

- Sprigg N, Bath PMW, Zhao L, Willmot M, Gray LJ, Walker M, et al. Granulocyte‐colony stimulating factor mobilises bone marrow stem cells in patients with sub‐acute ischaemic stroke: the 'Stem cell Trial of recovery EnhanceMent after Stroke' (STEMS) pilot randomised controlled trial. Stroke 2006;37:2979‐83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

STEMS‐2 2012 {published and unpublished data}

- England TJ, Auer D, Abaei M, Lowe J, Russell N, Jones R, et al. Granulocyte‐colony stimulating factor for mobilising bone marrow stem cells in sub‐acute stroke: the Stem Cell Trial of Recovery EnhanceMent after Stroke 2 (STEMS2) randomised controlled trial (ISRCTN 63336619). Stroke 2012;43(2):405‐11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

STEMTHER 2011 {published and unpublished data}

- Alasheev A, Belkin A, Leiderman I, Ivanov R, Isakova T. Granulocyte‐colony stimulating factor for acute ischemic stroke: a randomized controlled trial of safety and efficacy (STEMTHER). Translational Stroke Research 2011;2:358‐65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Yip 2011 {published data only}

- Yip HK, Tsai TH, Lin HS, Chen FS, Sun CK, Leu S, et al. Effect of erythropoietin on level of circulating endothelial progenitor cells and outcome in patients after acute ischaemic stroke. Critical Care 2011;15(1):R40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Zhang 2006 {published and unpublished data}

- Zhang JJ, Deng M, Zhang Y, Sui W, Wang L, Sun A, et al. A short‐term assessment of recombinant human granulocyte‐stimulating factor (RHG‐CSF) in treatment of acute cerebral infarction. Cerebrovascular Diseases 2006;21 Suppl 4:143. [Google Scholar]

References to studies excluded from this review

BETAS 2010 {published data only}

- Cramer SC, Fitzpatrick C, Warren M, Hill MD, Brown D, Whitaker L, et al. The beta‐hCG + erythropoietin in acute stroke (BETAS) study: a 3‐center, single‐dose, open‐label, noncontrolled, phase IIa safety trial. Stroke 2010;41(5):927‐31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Boy 2011 {published data only}

- Boy S, Sauerbruch S, Kraemer M, Schormann T, Schlachetzki F, Schuierer G, et al. Mobilisation of hematopoietic CD34+ precursor cells in patients with acute stroke is safe: results of an open‐labeled non randomized phase I/II trial. PLOS One 2011;6(8):e23099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Floel 2011 {published data only}

- Floel A, Warnecke T, Duning T, Lating Y, Uhlenbrock J, Schneider A, et al. Granulocyte‐colony stimulating factor (G‐CSF) in stroke patients with concomitant vascular disease‐a randomised controlled trial. PLOS One 2011;6(5):e19767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

REGENESIS CA {published data only}

- Cramer SC, Hill MD. REGENESIS (CA): a study of NTx™‐265: human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG) and epoetin alfa (EPO) in acute ischemic stroke patients. http://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT00663416.

REGENESIS‐LED {published data only}

- Cramer SC, Hill MD. A phase IIb prospective randomised double blind placebo controlled study of NTx‐265: human chorionic gonadotrophin (hCG) and epoetin alpha (EPO) in acute ischaemic stroke patients (REGENESIS trial). Stroke 2011;42(3):e268. [Google Scholar]

References to studies awaiting assessment

Farhoudi 2010 {published data only}

- Farhoudi M, Sadraddini S, Pashapour A, Altafi D, Ardalan M, Nayebpour M, et al. Effect of intravenous erythropoietin on functional status in putaminal hemorrhage: a randomized clinical trial. International Journal of Stroke 2010;5 Suppl 2:231. [Google Scholar]

Kalra 2012 {published data only}

- Kalra L. Erythropoietin to facilitate stroke recovery. http://public.ukcrn.org.uk/search/StudyDetail.aspx?StudyID=10503.

References to ongoing studies

CEPO 2008 {published data only}

- Lundbeck H. Randomised, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled, single‐dose, dose‐escalation study of the safety, tolerability, and pharmacokinetics of Lu AA24493 in acute ischemic stroke. ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT00756249.

CEPO 2009 {published data only}

- Lundbeck H. A randomised, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled, multiple‐dose, dose‐escalation study of the safety, tolerability, and pharmacokinetics of Lu AA24493 in patients with acute ischemic stroke. ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT00870844.

GENESIS‐2 {published data only}

- Takizawa S. G‐CSF employing neuroprotection study for ischemic stroke ‐Phase 2 clinical trial‐(GENESIS‐2). UMIN‐CTR Search Clinical Trials identifier UMIN000006607.

GIST 2008 {published data only}

- Sharma M. Granulocyte‐colony stimulating factor in ischemic stroke (GIST): a pilot study. ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT00809549.

Nilanont 2010 {published data only}

- Nilanont Y, Limsoontarakul S, Komoltri C, Chiewit P, Isaragrisil S, Poungvarin N. A randomized, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled trial of granulocyte colony stimulating factor (G‐CSF) for the treatment of acute ischemic stroke. International Journal of Stroke 2010;5 Suppl 2:192‐3. [Google Scholar]

STEMS‐3 {published data only}

- Sprigg N, Bath P. Stem cell trial of recovery enhancement after stroke 3: a randomised controlled trial. www.controlled‐trials.com/ISRCTN16714730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

Additional references

Berezovskaya 1996

- Berezovskaya O, Maysinger D, Fedoroff S. Colony stimulating factor‐1 potentiates neuronal survival in cerebral cortex ischemic lesion. Acta Neuropathology (Berlin) 1996;92(5):479‐86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Brines 2000

- Brines ML, Ghezzi P, Keenan S, Agnello D, Lanerolle NC, Cerami C, et al. Erythropoietin crosses the blood‐brain barrier to protect against experimental brain injury. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences USA 2000;97:10526‐31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Buschmann 2003

- Buschmann IR, Busch H‐J, Mies G, Hossmann K‐A. Therapeutic induction of arteriogenesis in hypoperfused rat brain via granulocyte macrophage colony‐stimulating factor. Stroke 2003;108:610‐5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Cochrane Handbook 2011

- Higgins JPT, Green S, editors. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions Version 5.1.0 [updated March 2011]. The Cochrane Collaboration, 2011. Available from www.cochrane‐handbook.org.

Corti 2002

- Corti S, Locatelli F, Strazzer S, Salani S, Bo R, Soligo D, et al. Modulated generation of neuronal cells from bone marrow by expansion and mobilization of circulating stem cells with in vivo cytokine treatment. Experimental Neurology 2002;177:443‐52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

England 2009

- England TJ, Gibson CL, Bath PM. Granulocyte‐colony stimulating factor in experimental stroke and its effects on infarct size and functional outcome: a systematic review. Brain Research Reviews 2009;62(1):71‐82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Erbayraktar 2003

- Erbayraktar S. Asialoerythropoietin is a nonerythropoietic cytokine with broad neuroprotective activity in vivo. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences USA 2003;100:6741‐6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Gabrilove 1994

- Gabrilove JL. Stem cell factor and basic fibroblast growth factor are synergistic in augmenting committed myeloid progenitor cell growth. Blood 1994;83:907‐10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Gibson 2005a

- Gibson CL, Bath PMW, Murphy SP. G‐CSF reduces infarct volume and improves functional recovery after transient focal cerebral ischemia in mice. Journal of Cerebral Blood Flow & Metabolism 2005;25:431‐9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Gibson 2005b

- Gibson CL, Jones NC, Prior MJW, Bath PMW, Murphy SP. G‐CSF suppresses edema formation and reduces interleukin‐1 expression following cerebral ischemia in mice. Journal of Neuropathology & Experimental Neurology 2005;64:1‐7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Gray 2009

- Gray LJ, Ali M, Lyden PD, Bath PM. Interconversion of the National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale and Scandinavian Stroke Scale in acute stroke. Journal of Stroke and Cerebrovascular Diseases 2009;18(6):466‐8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Jin 2002

- Jin K. Stem cell factor stimulates neurogenesis in vitro and in vivo. Journal of Clinical Investigation 2002;110:311‐9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Jung 2006

- Jung KH, Chu K, Lee ST, Kim SU, Kim M, Roh JK. G‐CSF protects human cerebral hybrid neurons against in vitro ischemia. Neuroscience Letters 2006;394:168‐73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Kawada 2006

- Kawada H, Takizawa S, Takanashi T, Morita Y, Fujita J, Fukuda K, et al. Administration of hematopoietic cytokines in the subacute phase after cerebral infarction is effective for functional recovery facilitating proliferation of intrinsic neural stem/progenitor cells and transition of bone marrow‐derived neuronal cells. Circulation 2006;113:701‐10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Kollmar 2010

- Kollmar R, Henninger N, Urbanek C, Schwab S. G‐CSF, rt‐PA and combination therapy after experimental thromboembolic stroke. Experimental & Translational Stroke Medicine 2010;2:9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Kong 2009

- Kong T, Choi JK, Park H, Choi BH, Snyder BJ, Bukhari S, et al. Reduction in programmed cell death and improvement in functional outcome of transient focal cerebral ischemia after administration of granulocyte‐macrophage colony‐stimulating factor in rats. Laboratory investigation. Journal of Neurosurgery 2009;111(1):155‐63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Leist 2004

- Leist M. Derivatives of erythropoietin that are tissue protective but not erythropoietic. Science 2004;305:239‐42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Murray 2012

- Murray CJ, Vos T, Lozano R, Naghavi M, Flaxman AD, Michaud C, et al. Disability‐adjusted life years (DALYs) for 291 diseases and injuries in 21 regions, 1990‐2010: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. Lancet 2012;380(9859):2197‐223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Nakagawa 2006

- Nakagawa T, Suga S, Kawase T, Toda M. Intra‐carotid injection of granulocyte‐macrophage colony stimulating factor induces neuroprotection in a rat transient middle cerebral artery occlusion model. Brain Research 2006;1089:179‐85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Navarro‐Sobrino 2009

- Navarro‐Sobrino M, Rosell A, Penalba A, Ribo M, Alvarez‐Sabin J, Fernandez‐Cadenas I, et al. Role of endogenous granulocyte‐macrophage colony stimulating factor following stroke and relationship to neurological outcome. Current Neurovascular Research 2009;6(4):246‐51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Park 2005

- Park HK, Kon Chu K, Lee ST, Jung KH, Kim EH, Lee KB, et al. Granulocyte colony‐stimulating factor induces sensorimotor recovery in intracerebral haemorrhage. Brain Research 2005;1041:125‐31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Popa‐Wagner 2010

- Popa‐Wagner A, Stocker K, Balseanu AT, Rogalewski A, Diederich K, Minnerup J, et al. Effects of granulocyte‐colony stimulating factor after stroke in aged rats. Stroke 2010;41(5):1027‐31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

RevMan 2012 [Computer program]

- The Nordic Cochrane Centre, The Cochrane Collaboration. Review Manager (RevMan). Version 5.2. Copenhagen: The Nordic Cochrane Centre, The Cochrane Collaboration, 2012.

Schabitz 2003

- Schabitz WR, Kollmar R, Schwaninger M, Juettler E, Bardutzky J, Scholzke MN, et al. Neuroprotective effect of granulocyte colony‐stimulating factor after focal cerebral ischemia. Stroke 2003;34:745‐6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Schabitz 2008

- Schabitz WR, Kruger C, Pitzer C, Weber D, Laage R, Gassler N, et al. A neuroprotective function for the hematopoietic protein granulocyte‐macrophage colony stimulating factor (GM‐CSF). Journal of Cerebral Blood Flow & Metabolism 2008;28(1):29‐43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Schneeloch 2004

- Schneeloch E, Mies G, Busch H‐J, Buschmann IR, Hossmann K. Granulocyte‐macrophage colony‐stimulating factor‐induced arteriogenesis reduces energy failure in hemodynamic stroke. Proceedings of the National Academy of Science USA 2004;101:12730‐5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Schneider 2005a

- Schneider A, Kruger C, Steigleder T, Weber D, Pitzer C, Laage R, et al. The hematopoietic factor G‐CSF is a neuronal ligand that counteracts programmed cell death and drives neurogenesis. Journal of Clinical Investigation 2005;115:2083‐98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Schneider 2005b

- Schneider A, Kuhn HG, Schabitz WR. A role for G‐CSF (granulocyte‐colony stimulating factor) in the central nervous system. Cell Cycle 2005;4:1753‐7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Seiler 2001

- Seiler C. Promotion of collateral growth by granulocyte‐macrophage colony‐stimulating factor in patients with coronary artery disease: a randomized, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled study. Circulation 2001;104:2012‐7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Sevimli 2009

- Sevimli S, Diederich K, Strecker JK, Schilling M, Klocke R, Nikol S, et al. Endogenous brain protection by granulocyte‐colony stimulating factor after ischemic stroke. Experimental Neurology 2009;217:328‐35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Shyu 2004

- Shyu WC, Lin SZ, Yang HI, Tzeng YS, Pang CY, Yen PS, et al. Functional recovery of stroke rats induced by granulocyte colony‐stimulating factor‐ stimulated cells. Circulation 2004;110:1847‐54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Siren 2001

- Siren AL. Erythropoietin prevents neuronal apoptosis after cerebral ischemia and metabolic stress. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences USA 2001;98:4044‐9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Six 2003

- Six I, Gasan G, Mura E, Bordet R. Beneficial effect of pharmacological mobilization of bone marrow in experimental cerebral ischemia. European Journal of Pharmacology 2003;458:327‐8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Sprigg 2004

- Sprigg N, Bath P. Pharmacological enhancement of recovery from stroke. Stroke Review 2004;8:33‐40. [Google Scholar]

STAIR 1999

- Stroke Therapy Academic Industry Roundtable. Recommendations for standards regarding preclinical neuroprotective and restorative drug development. Stroke 1999;30(12):2752‐8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Suehiro 1999