Abstract

There is some evidence that delta-opioid receptors may be involved in the brain processes related to neuroprotection. The aim of the present studies was to test the hypothesis that endogenous opioid peptides acting via delta-opioid receptors can protect against stress-induced changes in factors related to brain plasticity and stress hormone release. Forty male adult Wistar rats were used. Half of the animals were exposed to sustained partial restraint stress (hypokinesis) lasting 48 h. Rats were treated with vehicle (isotonic saline) or the delta-opioid receptor antagonist naltrindole (3 mg/kg/ml, s.c.) six times a day. The stressfulness of the model was confirmed by increased plasma concentrations of corticosterone and prolactin, the increase in anxiety behavior in the open field test, as well as the reduction of BrdU incorporation into newly formed DNA in the hippocampus. Treatment with naltrindole potentiated the stress-induced rise in aldosterone concentrations. The blockade of delta-opioid receptors resulted in a decrease in hippocampal BDNF gene expression independently of control or stress conditions. Treatment with naltrindole enhanced plasma concentrations of copeptin, a stable precursor of vasopressin. In conclusion, these results suggest that endogenous opioid peptides might play an inhibitory role in aldosterone release under stress conditions and in the control of vasopressin release independently of stress exposure. Endogenous opioids might stimulate hippocampal gene expression of the important neurotrophic factor BDNF via delta-opioid receptors.

Keywords: Delta-opioid peptides, Neuroprotection, Naltrindole, Hypokinesis

Introduction

Opioids have traditionally been associated with central analgesia. All three types of opioid receptors (mu, kappa, and delta) have been, at least to some degree, linked also to other brain processes, such as neuroprotection (Sheng et al. 2018). In particular, increasing evidence links delta-opioid receptors to major depressive disorder and anxiety (Fujii et al. 2020). Such evidence is based mainly on pharmacological action of delta-opioid agonists in a variety of animal models of depression and in few clinical studies (Richards et al. 2016; Dripps and Jutkiewicz 2018; Nagase and Saitoh 2020).

Delta-opioid agonists are of dominant importance as potential antidepressants or anxiolytics. Less attention has been given to the investigation of the role of endogenous delta-opioid system in the pathophysiology of mood disorders and their risk factors, such as stress and neuroendocrine dysbalance.

A decreased expression of brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF), acting via tyrosine receptor kinase B (TrkB) receptor, has been unequivocally related to chronic stress and depressive states (Karatas et al. 2018; Nunes et al. 2018). Pharmacological studies with delta-opioid agonists showed an upregulation of BDNF, which was reversible by delta-opioid receptor antagonists (Torregrossa et al. 2006). The data on the action of delta-opioid receptor antagonists themselves are very rare. The treatment with the delta antagonist naltrindole deepened the consequences of ischemic cerebral injury on BDNF/TrkB signaling, indicating a neuroprotective role of delta-opioid receptors (Sheng et al. 2018).

Another process associated with chronic stress and depressive states is the reduction of cell proliferation suggesting reduced brain plasticity, particularly in the hippocampus (Malberg and Duman 2003; Babic et al. 2012). The information of the importance of endogenous opioid peptides, which can be revealed by delta-opioid receptor blockade, is limited. A treatment of voluntary running spontaneously hypertensive rats with naltrindole failed to modify the running-induced rise in newly generated cells in the hippocampus but naltrindole increased hippocampal proliferation in non-running rats (Persson et al. 2004).

The relationship between delta-opioid receptors and glutamatergic neurotransmission is not well understood. The knowledge available has mainly been obtained in studies using delta agonists (Dripps and Jutkiewicz 2018). The selective delta-opioid receptor antagonist naltrindole affected glutamate AMPA receptor subunits in an animal model of hyperalgesia (Liu et al. 2018). The data suggesting an influence of delta-opioid peptides on glutamate transporters are inconsistent (Wu et al. 2013; Guo et al. 2015).

Classical stress hormones, namely glucocorticoids, were thought to be markers of depression states a long time ago. Endogenous opioid peptides are implicated in the control of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenocortical (HPA) axis but the exact nature of their role is still controversial (Jezova et al. 1982; Degli Uberti et al. 1995). With respect to delta-opioid peptides, studies using naltrindole (Kitchen and Pinker 1990) or ICI 154,129 (Kitchen and Rowan 1984) as antagonists failed to modify stress-induced corticosterone release in rodents. Other authors observed developmental consequences of early postnatal treatment with naltrindole on corticosterone response to swim stress in young rats (Fernandez et al. 1999).

Several other hormones known to be released in response to stress situations are associated with psychopathologies but almost neglected in endogenous opioid research. Thus, adrenocortical hormone aldosterone has been implicated in the development of anxiety and depression in animal models (Hlavacova and Jezova 2008; Jezova et al. 2019) and recently has been shown to be a state marker of major depressive disorder (Segeda et al. 2017; Izakova et al. 2020). Adenopituitary stress hormone prolactin is under the control by central dopamine and thus closely related to the effects and side effects of antipsychotic drug (Dehelean et al. 2020). Patients with major depression and several anxiety disorders exhibited enhanced concentrations of stress hormone vasopressin in plasma or cerebrospinal fluid (Merali et al. 2006). Copeptin, a stable precursor of vasopressin, has recently been reported in a pilot study as potential peripheral hypothalamic-level biomarker of antidepressant treatment response in major depressive disorder (Agorastos et al. 2020).

The aim of the present study was to test the hypothesis that endogenous opioid peptides acting via delta-opioid receptors can protect against stress-induced changes in neurochemical and hormonal markers. To test this hypothesis, the blockade of delta-opioid receptors by naltrindole and a subchronic hypokinetic stress model was used.

Methods

Animals

Forty male Wistar rats (Velaz, Prague, Czech Republic) weighing 220–250 g at the beginning of the experiments were used in this study. The rats were allowed to habituate to the housing facility for at least 7 days before testing. They were kept under standard housing conditions with a constant 12/12 h light/dark cycle (lights on at 07.00 h), temperature (22 ± 2 °C), and humidity (55 ± 10%). Animals were grouped two per cage with free access to rat chow and tap water. All experimental procedures were approved by the Animal Health and Animal Welfare Division of State Veterinary and Food Administration of the Slovak Republic (permission No. Ro 1914/17-221) and conformed to the NIH Guidelines for Care and Use of Laboratory Animals.

Study Design

The animals were randomly assigned to two treatment groups (n = 20 rats/group), naltrindole- and vehicle-treated rats. Half of the animals from each treatment group were exposed to stress of hypokinesis. According to the treatment and stress exposure, rats were finally assigned to four experimental groups (n = 10): 1. no stress-vehicle, rats treated with vehicle without stress exposure; 2. no stress-naltrindole, rats treated with naltrindole without stress exposure; 3. stress-vehicle, rats treated with vehicle with stress exposure; and 4. stress-naltrindole, rats treated with naltrindole with stress exposure. A scheme of the experiments with necessary timelines is given in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Scheme of a new subchronic stress model based on hypokinesis and the study design. Male Wistar rats were treated with naltrindole or vehicle every 4 h for 48 h. Half of the animals were exposed to hypokinesis (see Fig. 2), namely partial movement restriction for 48 h. OFT: Open Field Test, BrdU: 5-bromo-2´-deoxyuridine

Stress Model

A new subchronic stress model based on hypokinesis, namely partial movement restriction, for 48 h was developed. The model represents a modification of an old model aimed to simulate the conditions of space flight hypokinesis (Macho et al. 1989). The hypokinesis was performed by placing the rat to an adjustable plastic horseshoe-shaped cage (20 × 5 × 8.5 cm) (Fig. 2). The cage was adjusted so that the movement of the rat was strongly limited, but the animal was not entirely restrained. These hypokinetic cages were previously used also for repeated restraint for 10 days (Babic et al. 2015). As the peak corticosterone response was observed within 24 h and signs of adaptation were found few days thereafter (Macho et al. 1989), the behavioral testing was performed at 25 h and the exposure to hypokinesis was shortened to 48 h. The stressfulness of the new subchronic stress model was verified in previous experiments (Chomanic et al. 2020).

Fig. 2.

A new subchronic stress model based on partial movement restriction using a hypokinetic cage for 48 h. The hypokinesis was performed by placing the rat into the cage (20 × 5 × 8.5 cm). The movement of the rat was strongly limited, but the animal was not entirely restrained

Naltrindole and Vehicle Treatment

Delta-opioid receptor antagonist naltrindole (naltrindole hydrochloride, Sigma-Aldrich, Germany) was administered subcutaneously (s.c.) at a dose of 3 mg/kg (Saitoh et al. 2005) every 4 h for 48 h. Such frequent treatment was chosen to achieve sufficient and sustained drug concentrations throughout the 48 h. Control rats were treated with vehicle (saline). Low-intensity red light was used during the nocturnal administrations of naltrindole or vehicle.

5-Bromo-2´-deoxyuridine Administration

Twenty-seven and thirty-one hours from the beginning of experimental procedures, all animals were treated with 5-bromo-2´-deoxyuridine (BrdU) (Roche, Mannheim, Germany), an indicator of cell proliferation. BrdU was injected twice at the dose of 100 mg/kg intraperitoneally (i.p.). The time difference between the first and second injections was 4 h. Animals were killed approximately 17 h after the last BrdU injection, as described previously (Babic et al. 2015).

Open Field Test

Twenty-five hours from the beginning of treatments and stress exposure, the animals were subjected to an open field test for 5 min. The rats were allowed to habituate in the test room for 1 h before testing. The tests were performed between 9 and 11 am. The open field apparatus consisted of a rubber square area of 90 × 90 cm surrounded by a plastic 37 cm high walls. The apparatus was illuminated by dim light with the intensity of 40–45 lx in the central area, and 25–30 lx in the peripheral area. At the beginning of the test, the animal was placed in the corner of the open field (Hlavacova and Jezova 2008). The number of entries and time spent in the central zone were used as measures of the anxiety level. A central zone entry was defined as two paws entering.

Blood and Organ Collection

Following 48 h of experimental procedures, rats were quickly moved to an adjacent room and immediately decapitated. The trunk blood was collected into polyethylene tubes containing EDTA as anticoagulant and spun immediately at 4 °C to separate plasma, which was stored at − 20 °C until analyzed. The brain was quickly removed from the skull. The hippocampus was dissected, frozen in liquid nitrogen, and stored at − 80 °C until analyzed.

Isolation of DNA and RNA

The hippocampus was homogenized (Heidolph Homogenizer DIAX 900, Burladingen, Germany) in TRIzol® Reagent (Life technologies, California, USA − 1 ml/100 mg tissue sample). The extraction of DNA was performed as described previously (Buzgoova et al. 2019). The extracted DNA was dissolved in nuclease-free water and stored at 4 °C. The total mRNA was isolated according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Concentration and purity of mRNA preparations was measured by absorption spectroscopy (Nanodrop 2000).

Analysis of BrdU Incorporation into DNA

BrdU incorporation into DNA in the hippocampus was measured by sandwich enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA). The BrdU ELISA was performed as described previously (Babic et al. 2012). Primary monoclonal anti-BrdU antibody (formalin grade, Roche, Mannheim, Germany) was purified on high-trap affinity columns (1 ml rProtein A FF, Amersham Biosciences, Uppsala, Sweden). The secondary anti-BrdU antibody was conjugated with peroxidase. Peroxidase activity was determined by adding 3,3′,5,5′-tetramethylbenzidine substrate (Roche, Mannheim, Germany). The reaction was stopped with H2SO4 and the reaction product was determined by absorption at 450 nm.

Reverse Transcription and Quantitative Real-Time Polymerase Chain Reaction (RT–PCR)

The isolated hippocampal mRNA (1 µg) was reverse transcribed to cDNA using oligo (dT) nucleotides by M-MuLV reverse transcription system (ProtoScript First Strand cDNA Synthesis Kit, New England Biolabs, Ipswich, Massachusetts, United States). Primer BLAST NCBI software (Ye et al. 2012) was used to design primers specific for studied genes (Table 1). Quantitative PCR was used for evaluation of mRNA concentrations. Analysis was performed in a reaction volume of 10 µl by GoTaq quantitative PCR Master Mix (Promega, USA) as described previously (Balagova et al. 2019). Primers (Table 1) were used at a concentrations of 0.25 pmol/µl. In the case of the BDNF gene, 15 ng cDNA was added to the final reaction volume of 10 µl. For VGluT3 and GLT-1 genes, 30 ng cDNA was added to the final reaction volume (Graban et al. 2017). Quantitative PCR was performed by QuantStudio 5 Fast Real-Time PCR System (ThermoFisher, USA). All data obtained by quantitative PCR analysis were evaluated as ng of mRNA (cDNA) according to a standard curve and were normalized to gene expression of peptidylprolyl isomerase A (PPIA) and Ribosomal Protein S29 (RPS29) as reference genes. Gene expressions were evaluated by ∆∆Ct calculation and normalized to PPIA and RPS29 housekeeping genes as arbitrary units.

Table 1.

Nucleotide sequence of primers used for gene expression measurements

| Gene | Forward primer | Revers primer |

|---|---|---|

| BDNF | AGCAGAGGAGGCTCCAAGG | ACCATAAGGACGCGGACTTG |

| VGlut3 | TCCACGATATGCCAGCATCC | CTCCACTGTAGTGCACCAGG |

| GLT-1 | GGTCAATGTAGTGGGCGATT | GGACTGCGTCTTGGTCATTT |

| PPIA | AAGCATACAGGTCCTGGCATCT | CATTCAGTCTTGGCAGTGCAG |

| RPS29 | GCTGAACATGTGCCGACAGT | GGTCGCTTAGTCCAACTTAATGAA |

Plasma Hormone Measurements

Plasma corticosterone concentrations were measured by radioimmunoassay (RIA) kit (MP Biomedicals, Orangeburg, NY). The detection limit of the assay was 0.77 μg/100 ml. The corticosterone assay had intra- and inter-assay coefficients of variation of 4.4% and 7.2%, respectively. Plasma aldosterone concentrations were measured by RIA using commercially available kit (ZenTech, RIAZENco, Belgium). The intra- and inter-assay coefficients of variation were 3.8% and 7.5%, respectively. The detection limit was 1.4 pg/ml. Plasma prolactin and copeptin concentrations were measured by ELISA kits (FineTest®, Wuhan, China). The detection limits of the prolactin and copeptin assays were 0.781 ng/ml and 3.12 pg/ml, respectively. The intra- and inter-assay coefficients of variation were 8% and 10%, respectively, for both hormones measured.

Statistical Analysis

All data were first checked for the normality of distribution using the Shapiro-Wilk test. In the case of BrdU the data were not normally distributed and were subjected to decimal logarithm transformations for normalization of their distributions before analyses. Statistical significance was determined by two-way ANOVA with stress and treatment as main factors. Whenever interaction reached significance, the Tukey post hoc test was performed. Results are expressed as mean ± SEM. Values were winsorized when necessary. Overall level of significance was defined as p < 0.05.

Results

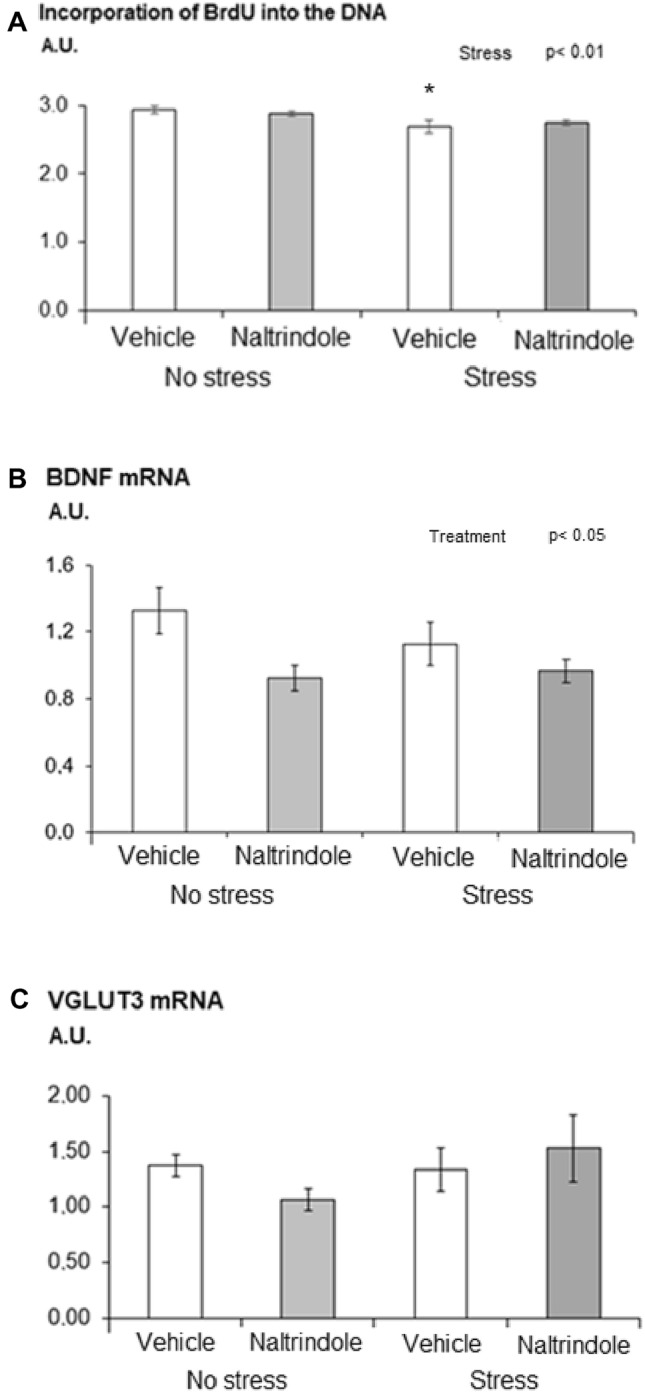

Statistical analysis of data on the incorporation of BrdU into DNA in the hippocampus revealed a stress-induced decrease in BrdU incorporation in both vehicle- and naltrindole-treated rats (Fig. 3a). Two-way ANOVA showed a significant main effect of stress [F(1, 36) = 9.93, p < 0.01, η2 = 0.22] on the incorporation of BrdU into DNA in the hippocampus in both vehicle- and naltrindole-treated rats.

Fig. 3.

Effect of naltrindole treatment and stress exposure on a incorporation of BrdU into DNA, b gene expression of BDNF and c gene expression of vesicular transporter VGluT3 in the hippocampus. Each value represents the mean ± S.E.M. (n = 10 rats/group). Statistical significance as revealed by two-way ANOVA with main factors of naltrindole treatment and stress. Statistical significance by Tukey post hoc test: ⁎p < 0.05 versus appropriate no stress group

Exposure of rats to stress of hypokinesis failed to modify gene expression of the BDNF. Statistical analysis of data on the BDNF mRNA in the hippocampus revealed a treatment-induced decrease in BDNF mRNA in both stressed and non-stressed rats (Fig. 3b). Two-way ANOVA showed a significant main effect of treatment [F(1, 36) = 6.87, p < 0.05, η2 = 0.16] on the BDNF mRNA in the hippocampus independent of the stress exposure.

Two-way ANOVA of data on the VGluT3 mRNA in the hippocampus did not reveal any significant stress- or treatment-induced changes (Fig. 3c). Statistical analysis of data on the GLT-1 mRNA in the hippocampus failed to reveal any significant changes (data not shown).

Two-way ANOVA revealed a significant main effect of stress [F(1, 36) = 15.42, p < 0.001, η2 = 0.30] on plasma corticosterone concentrations. Exposure to hypokinesis resulted in an increase in plasma corticosterone (Fig. 4a).

Fig. 4.

Effect of naltrindole treatment and stress exposure on plasma a corticosterone, b aldosterone, c prolactin, and d copeptin concentrations. Each value represents the mean ± S.E.M. (n = 10 rats/group). Statistical significance as tested by two-way ANOVA showing significant main factor of stress and stress × treatment interaction. Statistical significance by Tukey post hoc test: ⁎p < 0.05, ⁎⁎⁎p < 0.001 versus appropriate no stress group; x p < 0.05, xxp < 0.01, xxxp < 0.001 versus appropriate vehicle group

There was a significant main effect of stress [F(1, 36) = 25.71, p < 0.001, η2 = 0.42] and a significant stress × treatment interaction [F(1, 36) = 6.91, p < 0.01, η2 = 0.16] on plasma aldosterone concentrations (Fig. 4b). Tukey post hoc test showed that plasma aldosterone concentrations in stressed rats treated with naltrindole were significantly higher (p < 0.01) compared to those in stressed rats treated with vehicle.

There was a significant main effect of stress [F(1, 36) = 79.62, p < 0.001, η2 = 0.69] on plasma prolactin concentrations (Fig. 4c). Exposure to hypokinesis resulted in an increase in plasma prolactin concentrations in both vehicle- and naltrindole-treated rats.

Exposure of rats to stress of hypokinesis failed to modify copeptin concentrations in plasma. Two-way ANOVA showed a significant main effect of treatment [F(1, 36) = 32.53, p < 0.001, η2 = 0.47] on plasma copeptin concentrations (Fig. 4d). The delta-opioid receptor blockade by naltrindole resulted in an increase in plasma copeptin concentrations in both stressed and non-stressed rats compared to the vehicle-treated rats.

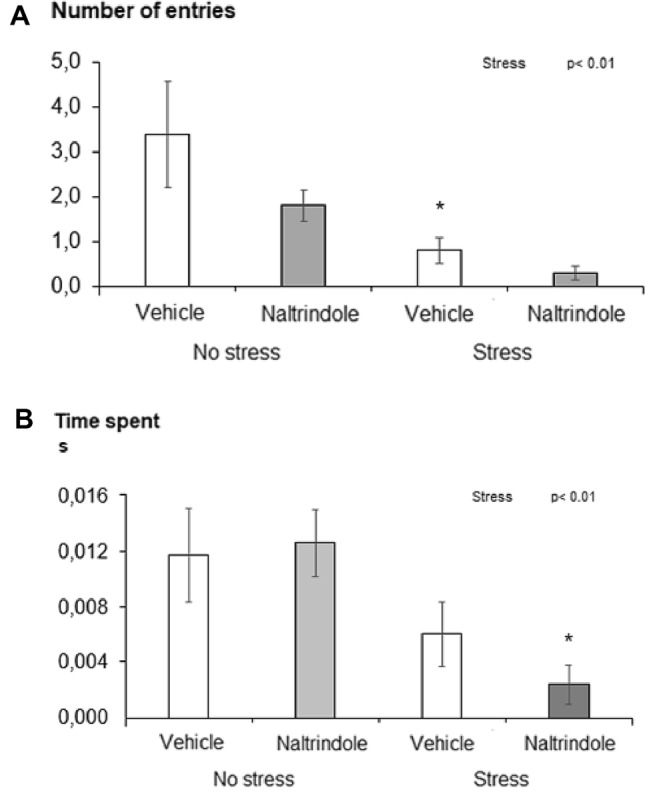

Two-way ANOVA revealed a significant main effect of stress on the frequency of entries [F(1, 36) = 11.71, p < 0.01, η2 = 0.25] and the percentage of time spent in the central area of the open field [F(1, 36) = 10.27 p < 0.01, η2 = 0.22]. The stressed rats entered less often and spent less time in the central area of the open field than the unstressed animals (Fig. 5a, b). The results of statistical analyses by ANOVA for the main factors and their interaction for all parameters measured are given in Table 2.

Fig. 5.

Effect of naltrindole treatment and stress exposure on anxiety-like behavior measured in the open field test: a number of entries into the central zone and b time spent in the central zone. Each value represents the mean ± S.E.M. (n = 10 rats/group). Statistical significance as revealed by two-way ANOVA with main factors of naltrindole treatment and stress. Statistical significance by Tukey post hoc test: ⁎p < 0.05 versus appropriate no stress group

Table 2.

The results of statistical analyses by ANOVA for the main factors and their interaction

| Parameter measured | Stress | Treatment | Stress*treatment |

|---|---|---|---|

| BrdU | p = 0.003 | p = 0.979 | p = 0.364 |

| BDNF | p = 0.488 | p = 0.013 | p = 0.270 |

| VGluT3 | p = 0.217 | p = 0.839 | p = 0.158 |

| Corticosterone | p = 0.000 | p = 0.317 | p = 0.841 |

| Aldosterone | p = 0.000 | p = 0.145 | p = 0.001 |

| Prolactin | p = 0.000 | p = 0.836 | p = 0.103 |

| Copeptin | p = 0.652 | p = 0.000 | p = 0.215 |

| OFT number of entries | p = 0.003 | p = 0.110 | p = 0.396 |

| OFT time spent | p = 0.003 | p = 0.578 | p = 0.373 |

Statistically significant differences are given in bold

Discussion

The present results show that the treatment with naltrindole potentiated the stress-induced rise in aldosterone concentrations, suggesting that endogenous opioid peptides have an inhibitory role on aldosterone release under stress conditions. The blockade of delta-opioid receptors resulted in a decrease in hippocampal BDNF gene expression independently of control or stress conditions, indicating a positive role of delta-opioid receptor activation on this neurotrophic factor. Endogenous opioid peptides acting via delta-receptors appear to play an inhibitory role in the control of vasopressin release as the treatment with naltrindole enhanced plasma concentrations of copeptin. The rise in plasma corticosterone and prolactin concentrations, the reduction of BrdU incorporation into newly formed DNA in the hippocampus, as well as increase in anxiety behavior confirmed the stressfulness of the stress model used.

Naltrindole treatment failed to modify aldosterone secretion under non-stress conditions, but it significantly enhanced aldosterone response to the subchronic stressor used. That is consistent with newly described anxiogenic and depressogenic effects of aldosterone (Hlavacova and Jezova 2008; Jezova et al. 2019) and the anxiolytic effects of delta-opioid receptor agonists (Dripps and Jutkiewicz 2018). To our knowledge, no information on delta-opioid receptor antagonist or agonist effects on aldosterone release can be found in the literature available. Thus, the present findings represent first piece of evidence on possible involvement of delta-opioid receptors in the control of aldosterone release, namely under subchronic stress conditions.

The reduction in BDNF gene expression in the hippocampus induced by delta-opioid receptor blockade observed in the present study is in agreement with pharmacological studies investigating delta-opioid agonists showing an upregulation of BDNF in the frontal cortex (Torregrossa et al. 2006). BDNF is well known to induce positive influence on brain plasticity together with a neuroprotective role under stress-related pathological states (Nunes et al. 2018). The present findings failed to get support for a neuroprotective role of delta-opioid receptors during stress exposure. A neuroprotective effect was reported following ischemic cerebral injury (Sheng et al. 2018). A negative influence of delta-opioid receptor blockade by naltrindole was not observed on cell proliferation, another marker of brain plasticity. It could be argued that the short 48 h treatment was not sufficient to modify hippocampal cell proliferation. The same time period was, however, sufficiently long to provoke stress-induced decrease in cell proliferation as measured by BrdU incorporation into newly formed DNA.

In spite of the known interaction between delta-opioid system and glutamate neurotransmission, naltrindole treatment did not influence hippocampal gene expression of vesicular and membrane glutamate transporters VGluT3 and GLT-1, respectively. Under non-stress conditions, naltrindole treatment led to a mild reduction in VGluT3 gene expression, which, however, failed to be statistically significant with the statistical analysis used. In the literature available, few in vitro studies showed increased expression of GLT-1 after activation of delta-opioid receptors by agonists (Liang et al. 2014). A possible influence of endogenous opioids on glutamate transporters has not been approached as yet.

An intriguing finding of the present study is the stimulatory effect of delta-opioid receptor blockade on plasma concentrations of copeptin, which represents a new, original finding. The only information available is that a single injection of a delta-opioid antagonist ICI 154,129 failed to modify vasopressin release (Iwasaki et al. 1994). An inhibitory role of endogenous opioid peptides via delta-opioid receptors in the control of vasopressin release has not been revealed so far. Van de Heijning et al. (1991) presented evidence for an involvement of μ- and к-opioid receptors, and not of delta-receptors, in the control of vasopressin release. These authors, however, used a single and not repeated treatment with a lower doses of naltrindole compared to the present study.

The present study failed to find support for a role of endogenous delta-opioid peptides in the control of prolactin and corticosterone release. No effect of delta-opioid antagonist on prolactin concentrations in male rats is consistent with the limited data in the literature showing no effect of delta-opioid agonist on prolactin release in female ovariectomized rats (Leadem and Yagenova 1987) or centrally administered delta-opioid receptor antagonist in pregnant or lactating rats (Andrews and Grattan 2003; Valdez et al. 2014). With respect to corticosterone, no effect of naltrindole treatment is in agreement with previous data using single antagonist (ICI 154,129 and low-dose naltrindole, respectively) injection (Kitchen and Rowan 1984; Kitchen and Pinker 1990). A single treatment with the same dose of naltrindole to Lewis rats, that are known to exhibit hypoactivity of the HPA axis (Moncek et al. 2001), led to clearly enhanced corticosterone release in response to an acute stressor (Saitoh et al. 2005). Interestingly, single injection of low-dose (1 mg/kg s.c.) naltrindole stimulated adrenocortical activity induced by a very short stressor (Marin et al. 2003). So far, chronic or subchronic treatment with naltrindole, as used in the present study, has not been investigated.

Behavior measured in the present study using open field test showed a tendency to higher anxiety in naltrindole-treated Wistar rats, but the differences failed to be statistically significant. In contrast to intensive research on anxiolytic effects of delta-opioid agonists, almost nothing is known on potential anxiolytic effects of endogenous opioid peptides acting via this receptor subtype. A single injection of the same dose of naltrindole to above-mentioned Lewis rats with HPA axis hypoactivity that are also addiction prone induced an anxiogenic effect in the elevated plus maze test (Saitoh et al. 2005). In NMRI mice, a single naltrindole injection was without effect on both anxiety and depression-like behavior (Haj-Mirzaian et al. 2019).

Conclusions

In conclusion, the results of experiments with blockade of delta-opioid receptors by repeated treatment with naltrindole and exposure of rats to a subchronic hypokinetic stress lasting 48 h provided support to the hypothesis that endogenous opioid peptides acting via delta-opioid receptors have a positive influence on selected neurochemical and hormonal markers associated with anxiety behavior. Endogenous opioids acting via delta-opioid receptors can induce neuroprotective effects as shown by changes in hippocampal gene expression of the important neurotrophic factor BDNF. Endogenous opioid peptides acting via delta-opioid receptors are likely to exert an inhibitory action on vasopressin release irrespectively of stress or non-stress conditions. Most importantly, stress-induced release of the anxiogenic hormone aldosterone seems to be under an inhibitory control by endogenous opioid peptides acting via delta-opioid receptors.

Acknowledgements

The authors are thankful to Ludmila Zilava for her perfect laboratory assistance.

Funding

The study was supported by Scientific Grant Agency of Ministry of Education of Slovak Republic (Grant Number VEGA 2/0042/19), the Slovak Research and Development Agency (APVV-15-0388), and ERA-NET-NEURON I/2018/569/UNMET.

Data Availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflict of interest

There is no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- Agorastos A, Sommer A, Heinig A, Wiedemann K, Demiralay C (2020) Vasopressin surrogate marker copeptin as a potential novel endocrine biomarker for antidepressant treatment response in major depression: a pilot study. Front Psychiatry 11:453. 10.3389/fpsyt.2020.00453 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andrews ZB, Grattan DR (2003) Opioid receptor subtypes involved in the regulation of prolactin secretion during pregnancy and lactation. J Neuroendocrinol 15(3):227–236. 10.1046/j.1365-2826.2003.00975.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Babic S, Ondrejcakova M, Bakos J, Racekova E, Jezova D (2012) Cell proliferation in the hippocampus and in the heart is modified by exposure to repeated stress and treatment with memantine. J Psychiatr Res 46:526–532. 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2012.01.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Babic S, Pokusa M, Danevova V, Ding ST, Jezova D (2015) Effects of atosiban on stress-related neuroendocrine factors. J Endocrinol 225(1):9–17. 10.1530/JOE-14-0560 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balagova L*, Graban J*, Puhova A*, Jezova D (2019) Opposite effects of voluntary physical exercise on β3-adrenergic receptors in the white and brown adipose tissue. Horm Metab Res 51(09): 608–617. 10.1055/a-0928-0758. *equally contributed [DOI] [PubMed]

- Buzgoova K, Graban J, Balagova L, Hlavacova N, Jezova D (2019) Brain derived neurotrophic factor expression and DNA methylation in response to subchronic valproic acid and/or aldosterone treatment. Croat Med J 60(2):71–77. 10.3325/cmj.2019.60.71 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chomanic P, Karailevova L, Graban J, Török B, Zelena D, Jezova D (2020) Effect of subchronic restraint and delta opioid receptor blockade on selected neuroendocrine factors in rats. In: Lukacova N, Galik J (ed) Proceedings of a conference of early career researchers in Slovakia, Kosice, pp 37–40

- Degli Uberti EC, Petraglia F, Bondanelli M, Guo AL, Valentini A, Salvadori S, Criscuolo M, Nappi RE, Genazzani AR (1995) Involvement of mu-opioid receptors in the modulation of pituitary-adrenal axis in normal and stressed rats. J Endocrinol Invest 18(1):1–7. 10.1007/BF03349688 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dehelean L, Romosan AM, Papava I, Bredicean CA, Dumitrascu V, Ursoniu S, Romosan RS (2020) Prolactin response to antipsychotics: an inpatient study. PLoS ONE 15(2):e0228648. 10.1371/journal.pone.0228648 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dripps IJ, Jutkiewicz EM (2018) Delta opioid receptors and modulation of mood and emotion. Handb Exp Pharmacol 247:179–197. 10.1007/164_2017_42 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernandez B, Antelo MT, Guaza C, Alberti I, Pinillos ML, Viveros MP (1999) Naltrindole administration during the preweanling period and manipulation affect adrenocortical reactivity in young rats. Brain Res Dev Brain Res 112(1):135–137. 10.1016/s0165-3806(98)00154-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujii H, Uchida Y, Shibasaki M, Nishida M, Yoshioka T, Kobayashi R, Honjo A, Itoh K, Yamada D, Hirayama S, Saitoh A (2020) Discovery of δ opioid receptor full agonists lacking a basic nitrogen atom and their antidepressant-like effects. Bioorg Med Chem Lett 30(12):127176. 10.1016/j.bmcl.2020.127176 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graban J, Hlavacova N, Jezova D (2017) Increased gene expression of selected vesicular and glial glutamate transporters in the frontal cortex in rats exposed to voluntary wheel running. J Physiol Pharmacol 68(5):709–714 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo M, Cao D, Zhu S, Fu G, Wu Q, Liang J, Cao M (2015) Chronic exposure to morphine decreases the expression of EAAT3 via opioid receptors in hippocampal neurons. Brain Res 1628(Pt A):40–49. 10.1016/j.brainres.2015.03.037 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haj-Mirzaian A, Nikbakhsh R, Ramezanzadeh K, Rezaee M, Amini-Khoei H, Haj-Mirzaian A, Ghesmati M, Afshari K, Haddadi NS, Dehpour AR (2019) Involvement of opioid system in behavioral despair induced by social isolation stress in mice. Biomed Pharmacother 109:938–944. 10.1016/j.biopha.2018.10.144 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hlavacova N, Jezova D (2008) Chronic treatment with the mineralocorticoid hormone aldosterone results in increased anxiety-like behavior. Horm Behav 54(1):90–97. 10.1016/j.yhbeh.2008.02.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iwasaki Y, Gaskill MB, Robertson GL (1994) The effect of selective opioid antagonists on vasopressin secretion in the rat. Endocrinology 134(1):55–62. 10.1210/endo.134.1.8275969 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Izakova L, Hlavacova N, Segeda V, Kapsdorfer D, Morovicsova E, Jezova D (2020) Salivary aldosterone, cortisol and their morning to evening slopes in patients with depressive disorder and healthy subjects: acute episode and follow up six months after reaching remission. Neuroendocrinology. 10.1159/000505921.10.1159/000505921 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jezova D, Vigas M, Jurcovicová J (1982) ACTH and corticosterone response to naloxone and morphine in normal, hypophysectomized and dexamethasone-treated rats. Life Sci 31(4):307–314. 10.1016/0024-3205(82)90407-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jezova D, Balagova L, Chmelova M, Hlavacova N (2019) Classical steroids in a new fashion: focus on testosterone and aldosterone. Curr Protein Pept Sci 20(11):1112–1118. 10.2174/1389203720666190704151254 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karatas H, Yemisci M, Eren-Kocak E, Dalkara T (2018) Brain peptides for the treatment of neuropsychiatric disorders. Curr Pharm Des 24(33):3905–3917. 10.2174/1381612824666181112112309 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kitchen I, Pinker SR (1990) Antagonism of swim-stress-induced antinociception by the delta-opioid receptor antagonist naltrindole in adult and young rats. Br J Pharmacol 100(4):685–688. 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1990.tb14076.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kitchen I, Rowan KM (1984) Differences in the effects of mu- and delta-opioid receptor antagonists upon plasma corticosterone levels in stressed mice. Eur J Pharmacol 101(1–2):153–156. 10.1016/0014-2999(84)90042-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leadem CA, Yagenova SV (1987) Effects of specific activation of mu-, delta- and kappa-opioid receptors on the secretion of luteinizing hormone and prolactin in the ovariectomized rat. Neuroendocrinology 45(2):109–117. 10.1159/000124712 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liang J, Chao D, Sandhu HK, Yu Y, Zhang L, Balboni G, Kim DH, Xia I (2014) δ-Opioid receptors up-regulate excitatory amino acid transporters in mouse astrocytes. Br J Pharmacol 171(23):5417–5430. 10.1111/bph.12857 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu A, Wang X, Wang H, Lv G, Li Y, Li H (2018) Δ-opioid receptor inhibition prevents remifentanil-induced post-operative hyperalgesia via regulating GluR1 trafficking and AMPA receptor function. Exp Ther Med 15(2):2140–2147. 10.3892/etm.2017.5652 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macho L, Kvetnansky R, Fickova M (1989) Activation of the sympathoadrenal system in rats during hypokinesia. Exp Clin Endocrinol 94(1–2):127–132. 10.1055/s-0029-1210888 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malberg JE, Duman RS (2003) Cell proliferation in adult hippocampus is decreased by inescapable stress: reversal by fluoxetine treatment. Neuropsychopharmacology 28(9):1562–1571. 10.1038/sj.npp.1300234 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marin S, Marco E, Biscaia M, Fernández B, Rubio M, Guaza C, Schmidhammer H, Viveros MP (2003) Involvement of the kappa-opioid receptor in the anxiogenic-like effect of CP 55,940 in male rats. Pharmacol Biochem Behav 74(3):649–656. 10.1016/s0091-3057(02)01041-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merali Z, Kent P, Du L, Hrdina P, Palkovits M, Faludi G, Poulter MO, Bedard T, Anisman H (2006) Corticotropin-releasing hormone, arginine vasopressin, gastrin-releasing peptide, and neuromedin B alterations in stress-relevant brain regions of suicides and control subjects. Biol Psychiatry 59(7):594–602. 10.1016/j.biopsych.2005.08.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moncek F, Kvetnansky R, Jezova D (2001) Differential responses to stress stimuli of Lewis and Fischer rats at the pituitary and adrenocortical level. Endocr Regul 35(1):35–41 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagase H, Saitoh A (2020) Research and development of κ opioid receptor agonists and δ opioid receptor agonists. Pharmacol Ther 205:107427. 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2019.107427 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nunes PV, Nascimento CF, Kim HK, Andreazza AC, Brentani HP, Suemoto CK, Leite REP, Ferretti-Rebustini EL, Pasqualucci CA, Nitrini R, Grinberg LT, Yong LT, WilsonJacob-Filho W, Lafer B (2018) Low brain-derived neurotrophic factor levels in post-mortem brains of older adults with depression and dementia in a large clinicopathological sample. J Affect Disord 241:176–181. 10.1016/j.jad.2018.08.025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Persson AI, Naylor AS, Jonsdottir IH, Nyberg F, Eriksson PS, Thorlin T (2004) Differential regulation of hippocampal progenitor proliferation by opioid receptor antagonists in running and non-running spontaneously hypertensive rats. Eur J Neurosci 19(7):1847–1855. 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2004.03268.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richards EM, Mathews DC, Luckenbaugh DA, Ionescu DF, Machado-Vieira R, Niciu MJ, Duncan WC, Nolan NM, Franco-Chaves JA, Hudzik T, Maciag C, Li S, Cross A, Smith MA, Zarate CA Jr (2016) A randomized, placebo-controlled pilot trial of the delta opioid receptor agonist AZD2327 in anxious depression. Psychopharmacology 233(6):1119–1130. 10.1007/s00213-015-4195-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saitoh A, Yoshikawa Y, Onodera K, Kamei J (2005) Role of delta-opioid receptor subtypes in anxiety-related behaviors in the elevated plus-maze in rats. Psychopharmacology 182(3):327–334. 10.1007/s00213-005-0112-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Segeda V, Izakova L, Hlavacova N, Bednarova A, Jezova D (2017) Aldosterone concentrations in saliva reflect the duration and severity of depressive episode in a sex dependent manner. J Psychiatr Res 91:164–168. 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2017.04.011 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Sheng S, Huang J, Ren Y, Zhi F, Tian X, Wen G, Ding G, Xia TC, Hua F, Xia Y (2018) Neuroprotection against hypoxic/ischemic injury: δ-opioid receptors and BDNF-TrkB pathway. Cell Physiol Biochem 47(1):302–315. 10.1159/000489808 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torregrossa MM, Jutkiewicz EM, Mosberg HI, Balboni G, Watson SJ, Woods JH (2006) Peptidic delta opioid receptor agonists produce antidepressant-like effects in the forced swim test and regulate BDNF mRNA expression in rats. Brain Res 1069(1):172–181. 10.1016/j.brainres.2005.11.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valdez SR, Pennacchio GE, Gamboa DF, de Di Nasso EG, Bregonzio C, Soaje M (2014) Opioid modulation of prolactin secretion induced by stress during late pregnancy. Role of ovarian steroids. Pharmacol Rep 66(3):386–393. 10.1016/j.pharep.2013.12.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van de Heijning BJ, Koekkoek-Van den Herik I, Van Wimersma Greidanus TB (1991) The opioid receptor subtypes mu and kappa, but not delta, are involved in the control of the vasopressin and oxytocin release in the rat. Eur J Pharmacol 209(3):199–206. 10.1016/0014-2999(91)90170-u [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu Q, Xia S, Lin J, Cao D, Chen W, Liu L, Fu I, Liang J, Cao M (2013) Effects of the altered activity of δ-opioid receptor on the expression of glutamate transporter type 3 induced by chronic exposure to morphine. J Neurol Sci 335(1–2):174–181. 10.1016/j.jns.2013.09.026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ye J, Coulouris G, Zaretskaya I, Cutcutache I, Rozen S, Madden TL (2012) Primer-BLAST: a tool to design target-specific primers for polymerase chain reaction. BMC Bioinform 13:134. 10.1186/1471-2105-13-134 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.