Abstract

Introduction

Despite people with haematological malignancies being particularly vulnerable to severe COVID-19 infection and complications, vaccine hesitancy may be a barrier to optimal vaccination. This study explored attitudes towards COVID-19 vaccination in people with haematological malignancies.

Methods

People with haematological malignancies at nine Australian health services were surveyed between June and October 2021. Sociodemographic and clinical characteristics were collected. Attitudes towards COVID-19 vaccination were explored using the Oxford COVID-19 Vaccine Hesitancy Scale, the Oxford COVID-19 Vaccine Confidence and Complacency Scale, and the Disease Influenced Vaccine Acceptance Scale-Six. Open-ended comments were qualitatively analysed.

Results

A total of 869 people with haematological malignancies (mean age 64.2 years, 43.6% female) participated. Most participants (85.3%) reported that they had received at least one COVID-19 vaccine dose. Participants who were younger, spoke English as a non-dominant language, and had a shorter time since diagnosis were less likely to be vaccinated. Those who were female or spoke English as their non-dominant language reported greater vaccine side-effect concerns. Younger participants reported greater concerns about the vaccine impacting their treatment.

Conclusion

People with haematological malignancies reported high vaccine uptake; however, targeted education for specific participant groups may address vaccine hesitancy concerns, given the need for COVID-19 vaccine boosters.

Keywords: COVID-19, COVID-19 vaccines, Hematological malignancies, Vaccination

Introduction

Globally, there have been over 768 million infections and 6.9 million deaths during the COVID-19 pandemic as of August 2023 [1]. People with haematological malignancies are particularly vulnerable to severe COVID-19 infection due to the immunosuppressive effects of the underlying disease, compounded by chemotherapy and B-cell depletion therapies, as well as the older age associated with many haematological conditions [2, 3].

In the absence of COVID-19 vaccination, people with haematological malignancies experienced a case fatality rate of over 30%, significantly higher than individuals without cancer [3, 4]. Unsurprisingly, people with haematological malignancies were prioritised in vaccination programmes [5–7]. COVID-19 vaccination in people with haematological malignancies is complicated by lower vaccine responsiveness compared to the general population and people with solid organ malignancies [8, 9]. Protection attained from two vaccine doses against COVID-19-related hospitalisation was attenuated among immunocompromised patients (77%) compared to the general population (90%) [10]. Vaccine responsiveness is influenced by the specific haematological disease, type, and recency of therapy. People with lymphoid disorders having received anti-CD20 therapy within the last 6 months are less likely to develop a serologic response after two vaccine doses [8]. A third primary vaccine dose in patients with haematological malignancies was shown to augment vaccine responsiveness [8]. These issues highlight the need for a clear focus on vaccine acceptance to maximise uptake in this population.

Vaccine hesitancy has been defined as “a psychological state of indecisiveness that people may experience when making a decision regarding vaccination” [11]. People with cancer report lower vaccine hesitancy than in the general population, although disease-specific concerns have been identified [12, 13]. Individual concerns relating to adverse vaccine effects on the disease and treatment, as well as interference with the vaccine from the cancer treatment, have been identified [14–16].

There is a paucity of research exploring COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy and attitudes in people with haematological malignancies [17–20]. As new variants arise and continuing vaccination schedules evolve, a better understanding of patient attitudes to vaccination and vaccine hesitancy will facilitate optimum adherence in this highly vulnerable group of people. This study sought to assess attitudes to COVID-19 vaccination and vaccine hesitancy, in people with haematological malignancies, by exploring how the disease-specific context of these malignancies impacts attitudes and behaviour, through the development and use of a statistically validated composite questionnaire with a free-text comment item.

Materials and Methods

Study Design

This cross-sectional survey study was conducted at nine Australian health services, encompassing four metropolitan and five regional/rural areas. The survey was open between June 30 and October 5, 2021. The study was approved by the Monash Health Human Research Ethics Committee (RES-21-0000-364L – 76466) and registered with the Australian New Zealand Clinical Trials Registry (ACTRN12621001467820).

Study Participants

Adults with a haematological malignancy and receiving care at a participating health service were eligible to participate. They were invited by text message, with a link to the participant information and electronic consent, if they had a scheduled medical appointment in the next 6 months. Potential participants were also invited to their medical appointments by their haematologist. After providing informed consent, participants were directed to complete the survey, which was hosted online using the Qualtrics® secure data capture platform. The survey was presented in English.

Measures

The 42-item survey was developed by the research team, which included clinicians, researchers, and consumer representatives (online suppl. Table S1; for all online suppl. material, see https://doi.org/10.1159/000536548). All items in the three validated scales were presented on a 5-point Likert scale with an additional “don’t know” option. Permission to use the scales was received. The survey was completed anonymously, so no identifiable information was collected.

Vaccine Uptake Status, Demographics, and Clinical History

The number of COVID-19 vaccine doses received was collected along with gender, age, highest education level, annual household income, Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander status, and whether English was the participant’s dominant language. Clinical history items included diagnosis, duration, and current treatment.

Oxford COVID-19 Vaccine Hesitancy Scale

This is a scale developed to evaluate intent to receive a COVID-19 vaccine. Higher scores suggest greater COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy [21].

Oxford COVID-19 Vaccine Confidence and Complacency Scale

This is a scale that assesses attitudes relating to vaccine confidence and complacency. It is comprised of four factors: collective importance of a vaccine, belief that the COVID-19 vaccine will work against COVID-19 infection, speed of vaccine development, and side-effects [21]. Higher scores indicate greater negative attitudes.

Disease-Influenced Vaccine Acceptance Scale-6

This is a scale that evaluates vaccine-associated attitudes relating to concerns about the patient’s disease and treatment [22]. It is comprised of two factors: disease complacency and vaccine vulnerability. Higher scores for the Disease Complacency subscale suggest greater vaccine complacency. For the vaccine vulnerability subscale, higher scores are indicative of greater perceived disease-related vaccine concerns [22].

Qualitative Responses

At the end of the survey, participants were invited to answer a free-text comment item: “Please include any comments about your feelings and thoughts about your cancer and COVID-19 vaccination that you would like to share. If you have no comments to include, please type “Nil”.”

Statistical Analysis

Incomplete, duplicate, and ineligible responses were removed prior to analysis. No imputation of missing data was conducted.

Summary and subscale scores were calculated for each scale. “Don’t know” responses were excluded from scoring [21]. The summary and subscale scores and clinico-demographic data were summarised using descriptive statistics. Variables with too few classifications were either combined or removed for analysis. Analysis of the proportion of participant agreement with the Disease-Influenced Vaccine Acceptance Scale-6 (DIVAS-6) items involved combining the “somewhat agree” and “strongly agree” responses.

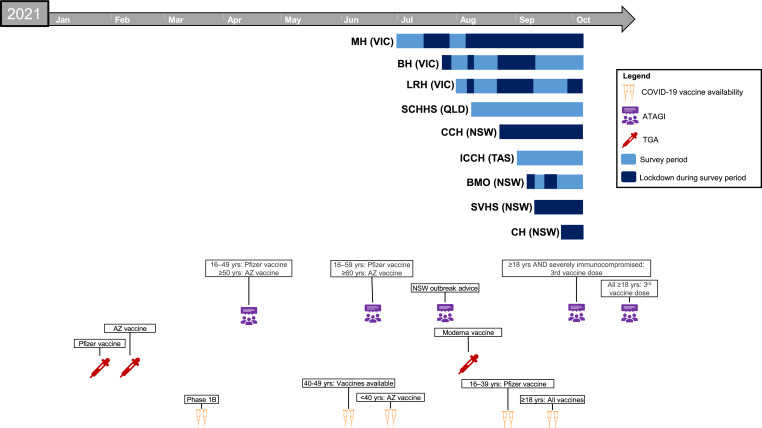

Time since study commencement was controlled for in regression analyses to account for public health restriction and vaccine rollout milestones (Fig. 1). Clinico-demographic variables were included in regression analyses if they were significant (p < 0.05) and had a bivariate correlation of r > 0.10 (using Pearson’s and Spearman’s Rho). Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS Version 27.0 (IBM, USA).

Fig. 1.

Timeline of study including survey period relative to state-wide strict lockdowns for COVID-19. People with haematological malignancies were eligible for COVID-19 vaccination from the commencement of the Australian Government Rollout Phase 1B. MH, Monash Health; VIC, Victoria; BH, Bendigo Health; LRH, Latrobe Regional Hospital; SCHHS; Sunshine Coast Hospital and Health Service; QLD; Queensland; CCH, Central Coast Haematology; NSW, New South Wales; ICCH, Icon Cancer Centre Hobart; TAS, Tasmania; BMO, Border Medical Oncology; SVHS, St Vincent’s Hospital Sydney; CH, Campbelltown Hospital; ATAGI, Australian Technical Advisory Group on Immunisation; TGA, Therapeutic Goods Administration – COVID-19 Vaccine Provisional Registration; AZ, AstraZeneca; yrs, years.

Qualitative Data Analysis and Interpretative Framework

Spelling errors within the free-text comments were corrected as part of data cleaning. Qualitative content analysis using NVivo 20 (QSR International, Australia) identified key themes from the free-text survey comments. Comments were coded and grouped into categories. Coding results were reviewed by three researchers (L.G., A.K., T.C.) and there was unanimous consensus on all common themes identified.

Results

Participant Characteristics

A total of 869 people with haematological malignancies completed the survey, with a mean age of 64.2 (SD 12.6) years and 379 females (43.6%). Participant characteristics are presented in Table 1. University was the most common level of education (387, 44.5%), and <50 K Australian Dollars (AUD) was the most reported annual household income (255, 29.3%). Of all participants, 366 (42.1%) reported they were diagnosed more than 5 years ago, and 302 (34.8%) indicated they were receiving treatment for their haematological malignancy.

Table 1.

Participant characteristics

| Total, n = 869 (%) | Vaccinated, n = 741 (85.3%) | Unvaccinated, n = 128 (14.7%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender* | |||

| Male | 485 (55.8) | 420 (86.6) | 65 (13.4) |

| Female | 379 (43.6) | 318 (83.9) | 61 (16.1) |

| Age, years | |||

| Mean (SD) | 64.2 (12.6) | 65.4 (12.0) | 57.4 (13.3) |

| 18–49 | 114 (13.1) | 84 (73.7) | 30 (26.3) |

| 50–69 | 420 (48.3) | 345 (82.1) | 75 (17.9) |

| ≥70 | 335 (38.6) | 312 (93.1) | 23 (6.9) |

| Highest level of education** | |||

| No formal/primary school | 18 (2.1) | 14 (77.8) | 4 (22.2) |

| Secondary school | 244 (28.1) | 205 (84.0) | 39 (16.0) |

| Vocational/trade | 217 (25.0) | 179 (82.5) | 38 (17.5) |

| University | 387 (44.5) | 341 (88.1) | 46 (11.9) |

| Annual household income (AUD) | |||

| <50K | 255 (29.3) | 221 (86.7) | 34 (13.3) |

| 50K – 100K | 201 (23.1) | 169 (84.1) | 32 (15.9) |

| 100K – 150K | 98 (11.3) | 77 (78.6) | 21 (21.4) |

| >150K | 157 (18.1) | 143 (91.1) | 14 (8.9) |

| Prefer not to say | 158 (18.2) | 131 (82.9) | 27 (17.1) |

| Aboriginal/Torres Strait Islander*** | |||

| Yes | 13 (1.5) | 8 (61.5) | 5 (38.5) |

| English as first language | |||

| Yes | 811 (93.3) | 705 (86.9) | 106 (13.1) |

| No | 58 (6.7) | 36 (62.1) | 22 (37.9) |

| Location | |||

| Metropolitan | 472 (54.3) | 393 (83.3) | 79 (16.7) |

| Regional/rural | 397 (45.7) | 348 (87.7) | 49 (12.3) |

| Time since diagnosis**** | |||

| <6 months | 64 (7.4) | 42 (65.6) | 22 (34.4) |

| 6–24 months | 184 (21.2) | 149 (81.0) | 35 (19.0) |

| >2 years | 621 (71.4) | 550 (88.6) | 71 (11.4) |

| Current anti-cancer treatment | |||

| Yes | 302 (34.8) | 243 (80.5) | 59 (19.5) |

| No | 567 (65.2) | 498 (87.8) | 69 (12.2) |

AUD, Australian Dollars; K, 1,000.

*Does not include “Non-binary/prefer not to say,” n = 5 (0.6%).

**Does not include “Other,” n = 3 (0.3%).

***Does not include “prefer not to say,” n = 7 (0.8%).

****The time since diagnosis categories of 2–5 years and >5 years were combined for all analyses.

Vaccine Uptake

Vaccination rate was 85.3%. Of those who were unvaccinated, 73 (57.0%) were likely to accept a vaccination, 29 (22.7%) were unsure, and 26 (20.3%) were unlikely to accept a vaccination. Participants who were younger, spoke English as a non-dominant language, or had a shorter time since diagnosis were less likely to be vaccinated (online suppl. Table S2). On multivariable regression, these relationships remained significant, except for a diagnosis time of 6 to 24 months, which was no longer associated with unvaccinated status (online suppl. Table S3).

Oxford COVID-19 Vaccine Hesitancy Scale

Higher vaccine hesitancy was associated with younger age, as was vocational/trade qualification (Table 2). On multivariable regression, these relationships remained significant (online suppl. Table S4).

Table 2.

Linear regression analysis predicting the Oxford COVID-19 Vaccine Hesitancy Scale summary score with sociodemographic and clinical characteristics

| Variable (reference, n) | Step 1 | Step 2 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adj. R2 | Adj. R2 | Δ Adj. R2 | B (SE) | p value | |

| Age (n = 830) | 0.025 | 0.036 | 0.011 | −0.04 (0.01) | 0.002 |

| Highest level of education (no formal/primary school/secondary school, n = 827) | 0.025 | 0.037 | 0.012 | ||

| Vocational/trade | 1.06 (0.41) | 0.01 | |||

| University | −0.22 (0.36) | 0.55 | |||

Step 1, time since study commencement is the only predictor variable entered into the model; Step 2, the clinico-demographic is the predictor variable entered into the model. These variable categories were excluded due to <20 responses: “other”’ educational level. Adj. R2, adjusted R2; B (SE), unstandardised coefficient (standard error).

Oxford COVID-19 Vaccine Confidence and Complacency Scale

Younger age was associated with a higher summary score, indicating greater negative attitudes around vaccine confidence and complacency (online suppl. Table S5). Female gender was associated with greater negative beliefs about the efficacy of the COVID-19 vaccine (online suppl. Table S5). Compared with secondary education or less, vocational/trade qualifications and university education were associated with more negative attitudes towards the speed of COVID-19 vaccine development (online suppl. Table S5), as was reporting an annual household income of ≥AUD 50K, when compared with participants who reported an annual household income <AUD 50K. Similarly, participants of a younger age reported more negative attitudes towards the speed of vaccine development. On multivariable regression, the relationships remained significant between the speed of development score and with vocational/trade qualifications, university education, and age, but not income (online suppl. Table S6). Younger age, female gender, and English as a non-dominant language were related to greater negative attitudes towards vaccine side-effects (online suppl. Table S5). On multivariable regression, younger age and English as a non-dominant language remained significantly associated with higher vaccine side-effect concerns (online suppl. Table S7). No significant demographic or clinical-related associations were observed with the collective importance subscale score.

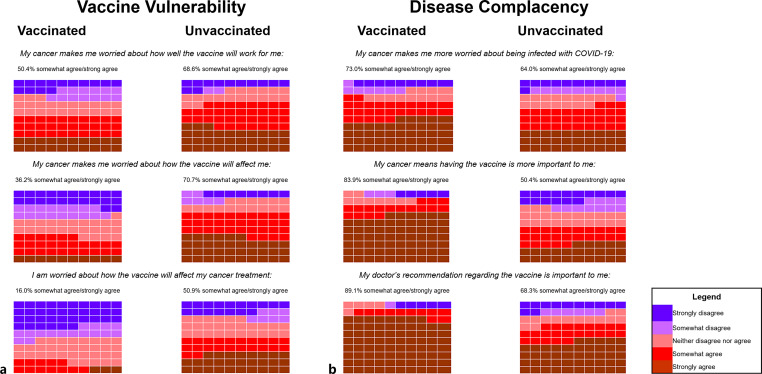

DIVAS-6

Significantly higher summary and subscale scores were observed in unvaccinated participants compared with vaccinated participants. When analysing the frequency of participant agreement for each DIVAS-6 item by vaccination status, a higher proportion of unvaccinated participants reported concerns about vaccine efficacy (68.6% vs. 50.4%), side-effects (70.7% vs. 36.2%), and interactions with anti-cancer treatment (50.9% vs. 16.0%) (Fig. 2a). In contrast, a higher proportion of vaccinated participants reported agreement that cancer made them worry about COVID-19 infection (71.6% vs. 64.0%), that having cancer means getting the vaccine is more important to them (83.9% vs. 50.4%), and that their doctor’s recommendation regarding the vaccine is important to them (89.1% vs. 68.3%) (Fig. 2b).

Fig. 2.

Response frequencies for the DIVAS-6 subscales: disease complacency (a) and vaccine vulnerability (b). Each box represents 1% of responses. The proportion of participants who either responded with “somewhat agree” or “strongly agree” are presented for each statement, by vaccination status. DIVAS-6, Disease Influenced Vaccine Acceptance Scale-6.

Participants who spoke English as a non-dominant language reported a higher summary scale score compared with those who spoke English as their dominant language (online suppl. Table S8). Younger participants reported a higher vaccine vulnerability subscale score, suggesting greater concerns about the vaccine impacting their haematological malignancy and treatment. No significant demographic or clinical-related associations were observed with the disease complacency subscale score.

Qualitative Analysis of Comments

Of the 869 survey respondents, 354 (40.7%) provided free-text comments able to be qualitatively analysed. Participants who provided comments were significantly more likely to be female and university educated than those who did not provide comments (online suppl. Table S9). They were also significantly less likely to be vaccinated, express intent to be vaccinated, believe they will be infected with COVID-19 in the next 12 months, and have an annual household income less than 50K AUD than participants who did not comment. Six themes emerged from the data analysis, with representative verbatim quotes (Table 3):

Table 3.

Representative quotes from the qualitative content analysis

| Theme | Representative quotes |

|---|---|

| Theme 1: Thrombosis concerns with the AstraZeneca Vaxzevria vaccine | Main concern is how my cancer and drug regime influence my chances of getting blood clots from [the] AstraZeneca [vaccine]. I know the percentages but that is for healthy people (age 66, male, diagnosed 6–24 months ago, unvaccinated) |

| I am worried about the AstraZeneca [vaccine] and have been trying to get an appointment for the Pfizer [vaccine] with no luck so far (age 39, male, diagnosed 2–5 years ago, unvaccinated) | |

| I think it’s very important to get vaccinated. I am immunocompromised so I’m vulnerable either way. I already take birth control which may cause blood clots so I don’t see the issue with taking a vaccine which might cause them. The risk is already there. I am more at risk of dying from COVID-19 than I am dying of the COVID-19 vaccine. (age 20, female, diagnosed <6 months ago, unvaccinated) | |

| Theme 2: Confusion, fear, and uncertainty | After having to put so much poison in my body for the cancer, why would I want to keep being a guinea pig with these experimental drugs? (age 58, female, diagnosed >5 years ago, vaccinated with one dose) |

| My cancer experience has confused me about what vaccine to have and when best to have it (age 63, female, diagnosed <6 months ago, unvaccinated) | |

| Just really confused and scared! (age 58, female, diagnosed 2–5 years ago, unvaccinated) | |

| Theme 3: Concerns about reduced vaccine efficacy and limited research in blood cancer | Vaccine efficacy |

| I am reading that no one knows how much protection it will give me. Some recent articles say it could be as low as 30% protection. I believe research of those similar to myself should be undertaken and YES I would gladly participate (age 66, female, diagnosed 6–24 months ago, unvaccinated) | |

| I am very aware that all current COVID-19 vaccines available are not as effective in regards to leukaemia patients but still, they help a lot, especially [the] Pfizer [vaccine] (age 50, female, diagnosed 2–5 years ago, vaccinated with two doses) | |

| My general practitioner and haematologist recommended [me] to have vaccination. I am glad now. I have heard that it might not work as well for immunosuppressant people, time will tell (age 67, female, diagnosed >5 years ago, vaccinated with two doses) | |

| Limited blood cancer research | |

| I was worried about how many tests were done on people with my medical history and condition (age 42, female, diagnosed >5 years ago, vaccinated with two doses) | |

| Does it trigger [a] cancer gene? (age 62, female, diagnosed >5 years ago, unvaccinated) | |

| I am concerned about the lack of research about the effects of the vaccination (in world-wide clinical trials) on people with multiple myeloma or other blood cancers. Will it cause a shorter time before [disease] relapse? (age 52, female, diagnosed 2–5 years ago, unvaccinated) | |

| Theme 4: Treatment timing | I had my first COVID-19 AstraZeneca [vaccine] injection prior to commencing chemotherapy treatment, with little or no reaction. My second injection is booked in for the third week after my third treatment or just prior to my fourth treatment (as advised by my oncologist) (age 63, female, diagnosed <6 months ago, vaccinated with one dose) |

| Somewhat concerned about how soon I should be vaccinated to ensure it works well. Last immunotherapy [treatment] was only on July 6th so feel I should wait a while but [I] don't know how long (age 63, female, diagnosed <6 months ago, unvaccinated) | |

| I am unable to receive the vaccine until my platelets are working properly. I do not know how long this will take but hopefully it happens soon. (Age 49, female, diagnosed 6–24 months ago, unvaccinated) | |

| Theme 5: Feeling safer having had the COVID-19 vaccine | Blood disorder, Stem cell transplant, Cancer, GVHD [Graft versus host disease]. All constitute high risk and I have/had them all. Vaccine [is] good (it will greatly assist the likelihood that I WON'T die) (age 70, male, diagnosed >5 years ago, vaccinated with two doses) |

| I feel that the vaccination [is] for extra protection for me as my haematological condition and treatment lower my body resistance to any virus (age 64, male, diagnosed 2–5 years ago, vaccinated with two doses) | |

| I feel braver and more protected now [that] I have had both doses (age 50, female, diagnosed 2–5 years ago, vaccinated with two doses) | |

| Regardless of any conditions we all should get immunised to safeguard ourselves and others (age 74, male, diagnosed >5 years ago, vaccinated with two doses) | |

| Theme 6: Consistent and targeted haematological malignancy-specific information and advice | I would like to know if and when I am able to have the COVID-19 vaccine (age 61, female, diagnosed <6 months ago, unvaccinated) |

| Current literature relating to COVID-19 vaccines and blood cancers should be made available to patients so that they [can] make an informed decision regarding the treatment available to them (age 70, female, diagnosed 2–5 years ago, vaccinated with two doses) |

Theme 1: Thrombosis Concerns with the AstraZeneca Vaccine

The concerns about blood clots from the AstraZeneca vaccine (Vaxzevria) were a common theme for people who were and were not vaccinated. Some unvaccinated people commented that they were not comfortable accepting Vaxzevria because of the potential thrombotic events. Some concerns were due to a family history of thrombosis, while others expressed concern regarding the small risk of thrombosis might be larger due to their illness and therapy, with limited research available to this population. Several people who accepted Vaxzevria commented that they would have preferred the Pfizer BioNTech Comirnaty vaccine and were uncomfortable with their lack of choice in the context of their haematological condition. Those who had accepted Vaxzevria often commented that this was on medical advice or that they had rationalised that the risk of thrombosis was less of a concern than the risk of dying if they contracted COVID-19.

Theme 2: Confusion, Fear, and Uncertainty

There was a theme of confusion, fear, and uncertainty that appeared to be linked to a compounding effect of the participant’s cancer experience. A few unvaccinated participants commented that the experience of chemotherapy side-effects contributed to their hesitancy, both because it has made them less trusting of medical advice and due to the relatively limited research related to long-term vaccine implications.

Theme 3: Concerns about Reduced Vaccine Efficacy and Limited Research in Blood Cancer

Concerns about vaccine effectiveness were present in vaccinated and unvaccinated participants. In unvaccinated participants, this was cited as a barrier to accepting the COVID-19 vaccination. In vaccinated participants, similar concerns regarding uncertainty of vaccine effectiveness in the context of their condition were prevalent.

Theme 4: Treatment Timing

Some unvaccinated participants reported being unable to accept the COVID-19 vaccination due to their current stage of treatment, including being in a treatment phase, but also those who had recently completed treatment. A number of participants in this situation were keen to receive the COVID-19 vaccination as soon as their treating physician allowed.

Theme 5: Feeling Safer Having Had the COVID-19 Vaccine

A number of participants commented that they felt safer once they had been vaccinated. This was often stated in the context of their higher risk of severe COVID-19 outcomes due to their haematological condition, as well as generally due to the risk of COVID-19 and for the greater good of the community.

Theme 6: Consistent and Targeted Haematological Malignancy-Specific Information and Advice

Some participants commented that they did not know if and when they were able to get the COVID-19 vaccine. Others stated that they had been “recommended” to take only a specific vaccination, so they were waiting for it to become available. There was clear indication about the importance of the healthcare team, specifically haematologists and general practitioners, in the decision-making around vaccination. Some participants reported receiving conflicting advice from their general practitioner and haematologist, both about whether to get vaccinated at the current time and which vaccination they should receive.

Discussion

This study comprehensively evaluated attitudes to COVID-19 vaccination in people with haematological malignancies using validated measures and free-text responses. It is the first to report both qualitative and quantitative insight into the perceptions and attitudes of people with haematological malignancies. The study commenced 3 months (Fig. 1) into Australia’s vaccination rollout, with the first two vaccines available, the AstraZeneca vaccine (Vaxzevria) and the Pfizer BioNTech vaccine (Comirnaty).

Participants reported concerns regarding COVID-19 infection, as well as vaccine effectiveness, safety, and interaction of vaccines with their disease and treatment. In this study, 14.7% of respondents remained unvaccinated, although more than half reported being likely to accept vaccination; only 20.3% of those unvaccinated were unlikely to accept vaccination. Consistent with other studies, a significant proportion of vulnerable patients exhibited a willingness to proceed with vaccination [17–20].

The fear of thrombotic events associated with Vaxzevria was a key vaccination concern [23–25]. Our qualitative analysis found this was compounded by concerns that their haematological malignancy would interact poorly with Vaxzevria and increase the risk of thrombosis. Vaxzevria was the most readily available vaccine during the survey period [26]. The heightened concerns about Vaxzevria, particularly among those who are unvaccinated, were also identified in an Australian qualitative study conducted with people with underlying health conditions [27]. These concerns highlight the impact of vaccine side-effects on hesitancy, which continues to be relevant as vaccine development evolves. For example, the subsequent identification of rare cardiac complications from Comirnaty is likely to manifest similar fears within the general community [28]. Our qualitative analysis highlights the importance of addressing vaccine side-effect concerns in a disease-specific context.

The importance of specialist healthcare provider advice about vaccination in the context of disease has been highlighted in other severe chronic diseases, such as cancer and multiple sclerosis [13, 29, 30]. Receiving COVID-19 vaccine information from oncologists specifically has been highlighted as a preferred approach for people with cancer [31]. Consistent and targeted information between all members of each patient’s healthcare team, including haematologists, will ensure hesitancy is minimised. On a larger scale, patients with haematological malignancies were regrettably not represented in initial safety and efficacy studies. The benefits of shared decision-making in healthcare are well established and require a greater focus to maximise uptake of COVID-19 boosters in vulnerable medical populations [32].

Varying attitudes towards vaccination are noted in different subgroups, and while there is a broad sample of individuals included across age, gender, financial, educational, language, and indigenous groups in this study, it is worth noting some variation in demographic factors. Those with university educations are enriched in this study (44.5% vs. 32% Australia-wide) [33], there are fewer people who speak English as a second language (6% vs. 28% Australia-wide) [34], and more participants were from non-metropolitan regions (45.7% vs. 28% Australia-wide) [35]. It is difficult to determine the effect these differences have on vaccination attitudes; however, the higher hesitancy and more negative attitudes towards vaccination that are observed for different subgroups are likely multifactorial. Higher vaccine hesitancy and lower vaccine uptake have been previously documented in younger people, including in other chronic diseases [12, 17, 36]. Despite the significant risk due to haematological malignancy, younger people may perceive they have greater protection if they were to contract COVID-19, given that severe adverse outcomes have been broadly publicised to affect older people [37]. Concurrently, they may fear potential side-effects of the vaccine, as the thrombotic risk associated with Vaxzevria was specific to younger individuals, altering their perception of their own overall risk-benefit profile [38, 39]. The increased risk of myocarditis in young males, following the administration of Comirnaty, may also compound hesitancy in younger individuals [40, 41].

For people who speak English as a non-dominant language, language barriers may contribute to less awareness that they were prioritised for the COVID-19 vaccine and strengthened their reliance on their intimate social network for medical advice [42]. Indeed, the language that COVID-19 information is presented in has been shown to increase trust in vaccine safety and efficacy in one study, highlighting the power of language in reducing vaccine hesitancy [43].

Addressing COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy and COVID-19 vaccine concerns is fundamental to optimising uptake of future vaccine doses. Booster vaccinations have been shown to be effective in people with haematological malignancies [44]. A population-level study conducted on people with haematological malignancies in England reported that vaccine uptake has declined from the first dose [45]. As COVID-19 vaccination remains a vital preventative measure against infection in this population group, strategies to address their concerns are essential.

This is a large study of COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy in people with haematological malignancy, sampling across diverse demographics. We used validated assessment scales and disease-specific questions to comprehensively explore participant attitudes regarding vaccination. The qualitative analysis provides an in-depth understanding about vaccine hesitancy in this cohort. During the study period, there were varying COVID-19 transmission rates across time and regions and different public health and social measures, which provided information spanning the range of pandemic experiences.

This study has some limitations. The survey-based design with participant-reported responses might lead to recall and misclassification bias. As discussed above, the study sample may not be fully representative due to the likely greater participation of people with higher health literacy, English language proficiency, and internet access. An interest in COVID-19 and related matters may have also impacted sample representativeness. We did not evaluate haematological malignancy type, cultural, and political factors but focussed on broad disease-related influences. The participants’ attitudes towards non-COVID-19 vaccinations were not captured in the survey, so it is unclear whether the study’s findings on the participants’ attitudes are unique to COVID-19 vaccination. Therefore, further research exploring the attitudes towards vaccines in people with haematological malignancies more broadly is warranted. Additionally, the epidemiology of COVID-19 in Australia at the time of the study, with comparably low prevalence and disease burden, may limit direct comparisons with other world regions. Similarly, data collection for the current study was at a time when thrombosis concerns about taking Vaxzevria were prevalent, and some participants may have experienced difficulty with accessing another option. Despite this, our qualitative analysis highlights the impact of vaccine side-effects on hesitancy, which continues to be relevant given that side-effects are inherent in all medications.

In conclusion, people with haematological malignancies express COVID-19 vaccine concerns and hesitancy that are related to their diagnosis. Medical vulnerability to COVID-19 due to disease or treatment status can promote COVID-19 vaccination. In contrast, concerns regarding the potential negative impact of the vaccine on health, haematological malignancy, or treatments can contribute to vaccine hesitancy. These complex concerns must be comprehensively addressed by individual haematologists to optimise COVID-19 vaccination, particularly in this medically vulnerable population with the ongoing need for additional and future vaccine doses.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank our consumer representative, Janne Williams, and the recruitment teams at each study site for their contributions to this study.

Statement of Ethics

This study protocol was approved by the Monash Health Human Research Ethics Committee (approval number RES-21-0000-364L – 76466). Written informed consent was obtained from participants to participate in the study.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Funding Sources

This study was not funded from any external source.

Author Contributions

E.S. was the chief investigator, conceived the study, and led the design. D.D., L.G., M.N., and N.B. contributed to the design. R.B., N.H., C.F., J.J., S.O., S.H., B.A.C., M.N., and N.B. were part of the investigation. L.G., A.K., and T.C. analysed the data and accessed and verified the underlying data. R.B., and N.H. drafted the initial manuscript. R.B., N.H., L.G., A.K., T.C., C.F., J.J., S.O., S.H., B.A.C., M.N., N.B., D.D., and E.S. revised the manuscript critically for important intellectual content, had access to the data, gave final approval, and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Funding Statement

This study was not funded from any external source.

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this article and its online supplementary material. Further enquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Supplementary Material.

References

- 1. World Health Organisation . WHO Coronavirus (COVID-19) Dashboard [updated 2023 Aug 2; cited 2023 Aug 6]. Available from: https://covid19.who.int/.

- 2. Zorzi M, Guzzinati S, Avossa F, Fedeli U, Calcinotto A, Rugge M. SARS-CoV-2 infection in cancer patients: a population-based study. Front Oncol. 2021;11:11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Zhang H, Han H, He T, Labbe KE, Hernandez AV, Chen H, et al. Clinical characteristics and outcomes of COVID-19–infected cancer patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2020;113(4):371–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Pagano L, Salmanton-García J, Marchesi F, Busca A, Corradini P, Hoenigl M, et al. COVID-19 infection in adult patients with hematological malignancies: a European Hematology Association Survey (EPICOVIDEHA). J Hematol Oncol. 2021;14(1):168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Department of Health . Priority groups for COVID-19 vaccination program: phase 1b. Australian Government; [updated March 18 2021; cited 2023 May 14]. Available from: https://www.health.gov.au/sites/default/files/documents/2021/03/priority-groups-for-covid-19-vaccination-program-phase-1b_1.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 6. Anesi J. The advisory Committee on Immunization practices’ updated interim recommendation for allocation of COVID-19 vaccine-United States, December 2020. Am J Transplant. 2021;21(2):897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. UK Government . COVID-19 vaccination first phase priority groups. [updated 2021 23 Apr; cited 2023 Aug 6]. Available from: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/covid-19-vaccination-care-home-and-healthcare-settings-posters/covid-19-vaccination-first-phase-priority-groups.

- 8. Fendler A, de Vries EGE, GeurtsvanKessel CH, Haanen JB, Wörmann B, Turajlic S, et al. COVID-19 vaccines in patients with cancer: immunogenicity, efficacy and safety. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2022;19(6):385–401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Haematology Society of Australia and New Zealand . Australia and New Zealand consensus position statement: use of COVID-19 therapeutics in patients with haematological malignancies. 2022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Embi PJ, Levy ME, Naleway AL, Patel P, Gaglani M, Natarajan K, et al. Effectiveness of two-dose vaccination with mRNA COVID-19 vaccines against COVID-19–associated hospitalizations among immunocompromised adults—nine States, January–September 2021. Am J Transplant. 2022;22(1):306–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Bussink-Voorend D, Hautvast JLA, Vandeberg L, Visser O, Hulscher MEJL. A systematic literature review to clarify the concept of vaccine hesitancy. Nat Hum Behav. 2022;6(12):1634–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Tsai R, Hervey J, Hoffman K, Wood J, Johnson J, Deighton D, et al. COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy and acceptance among individuals with cancer, autoimmune diseases, or other serious comorbid conditions: cross-sectional, internet-based survey. JMIR Public Health Surveill. 2022;8(1):e29872. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Butow P, Shaw J, Bartley N, Milch V, Sathiaraj R, Turnbull S, et al. Vaccine hesitancy in cancer patients: a rapid review. Patient Educ Couns. 2023;111:107680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Mejri N, Berrazega Y, Ouertani E, Rachdi H, Bohli M, Kochbati L, et al. Understanding COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy and resistance: another challenge in cancer patients. Support Care Cancer. 2022;30(1):289–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Nguyen M, Bain N, Grech L, Choi T, Harris S, Chau H, et al. COVID-19 vaccination rates, intent, and hesitancy in patients with solid organ and blood cancers: a multicenter study. Asia Pac J Clin Oncol. 2022;18(6):570–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Brodziak A, Sigorski D, Osmola M, Wilk M, Gawlik-Urban A, Kiszka J, et al. Attitudes of patients with cancer towards vaccinations—results of online survey with special focus on the vaccination against COVID-19. Vaccines. 2021;9(5):411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Akesson J, Weiss ES, Sae-Hau M, Gracia G, Lee M, Culp L, et al. COVID-19 vaccine–related beliefs and behaviors among patients with and survivors of hematologic malignancies. JCO Oncol Pract. 2023;19(2):e167–75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Sweiss K, Russell M, Calip GS, Nguyen R, Khan M, Shah E, et al. Social and demographic factors contributing to COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy in patients with hematologic malignancies. Blood. 2021;138(Suppl 1):841. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Narinx J, Houbiers M, Seidel L, Beguin Y. Adherence to Sars-CoV2 vaccination in hematological patients. Front Immunol. 2022;13:994311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Güven ZT, Çelik S, Keklik M, Ünal A. Coronavirus anxiety level and COVID-19 vaccine attitude among patients with hematological malignancies. Cureus. 2023;15(5):e38618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Freeman D, Loe BS, Chadwick A, Vaccari C, Waite F, Rosebrock L, et al. COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy in the UK: the Oxford coronavirus explanations, attitudes, and narratives survey (Oceans) II. Psychol Med. 2020;52(14):3127–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Grech L, Loe BS, Day D, Freeman D, Kwok A, Nguyen M, et al. The Disease Influenced Vaccine Acceptance Scale-Six (DIVAS-6): validation of a measure to assess disease-related COVID-19 vaccine attitudes and concerns. Behav Med. 2022;49(4):402–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Danchin M, Buttery J. COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy: a unique set of challenges. Intern Med J. 2021;51(12):1987–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Di Noia V, Renna D, Barberi V, Di Civita M, Riva F, Costantini G, et al. The first report on coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) vaccine refusal by patients with solid cancer in Italy: early data from a single-institute survey. Eur J Cancer. 2021;153:260–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Leask J, Carlson SJ, Attwell K, Clark KK, Kaufman J, Hughes C, et al. Communicating with patients and the public about COVID-19 vaccine safety: recommendations from the Collaboration on Social Science and Immunisation. Med J Aust. 2021;215(1):9–12.e1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Australian Government . Australia’s vaccine agreements: Australian Government Department of Health and Aged Care; [updated 2023 Jun 27; cited 2023 Aug 6]. Available from: https://www.health.gov.au/our-work/covid-19-vaccines/about-rollout/vaccine-agreements?language=und.

- 27. Steffens MS, Bullivant B, King C, Bolsewicz K. “I’m scared that if I have the vaccine, it’s going to make my lung condition worse, not better.” COVID-19 vaccine acceptance in adults with underlying health conditions – a qualitative investigation. Vaccine X. 2022;12:100243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Heidecker B, Dagan N, Balicer R, Eriksson U, Rosano G, Coats A, et al. Myocarditis following COVID-19 vaccine: incidence, presentation, diagnosis, pathophysiology, therapy, and outcomes put into perspective. A clinical consensus document supported by the Heart Failure Association of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) and the ESC Working Group on Myocardial and Pericardial Diseases. Eur J Heart Fail. 2022;24(11):2000–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Kalron A, Dolev M, Menascu S, Aloni R, Givon U, Magalashvili D, et al. Overcoming COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy in people with multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler J. 2021;27(2 Supp):218. [Google Scholar]

- 30. Wu H, Ward M, Brown A, Blackwell E, Umer A. COVID-19 Vaccine intent in appalachian patients with multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler Relat Disord. 2022;57:103450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Prabani KIP, Weerasekara I, Damayanthi HDWT. COVID-19 vaccine acceptance and hesitancy among patients with cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Public Health. 2022;212:66–75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Thistlethwaite J, Evans R, Tie RN, Heal C. Shared decision making and decision aids: a literature review. Aust Fam Physician. 2006;35(7):537–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Australian Bureau of Statistics . Education and work. Australia Canberra: ABS. [updated 2022 May; cited 2023 Oct 18]. Available from: https://www.abs.gov.au/statistics/people/education/education-and-work-australia/latest-release. [Google Scholar]

- 34. Australian Bureau of Statistics . Cultural diversity: census canberra. ABS. [updated 2021; cited 2023 Sep 28]. Available from: https://www.abs.gov.au/statistics/people/people-and-communities/cultural-diversity-census/latest-release. [Google Scholar]

- 35. Australian Institute of Health and Welfare . Profile of Australia’s population Canberra. Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. [updated 2023; cited 2023 September 28]. Available from: https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/australias-health/profile-of-australias-population. [Google Scholar]

- 36. Edwards B, Biddle N, Gray M, Sollis K. COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy and resistance: correlates in a nationally representative longitudinal survey of the Australian population. PLoS One. 2021;16(3):e0248892. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Mueller AL, McNamara MS, Sinclair DA. Why does COVID-19 disproportionately affect older people? Aging. 2020;12(10):9959–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Australian Government . ATAGI Statement on AstraZeneca vaccine in response to new vaccine safety concerns. Australian Government Department of Health and Aged Care; 2021. [updated 2021 Apr 8; cited 2023 May 28]. Available from: https://www.health.gov.au/news/atagi-statement-on-astrazeneca-vaccine-in-response-to-new-vaccine-safety-concerns. [Google Scholar]

- 39. Andrews NJ, Stowe J, Ramsay MEB, Miller E. Risk of venous thrombotic events and thrombocytopenia in sequential time periods after ChAdOx1 and BNT162b2 COVID-19 vaccines: a national cohort study in England. Lancet Reg Health Eur. 2022;13:100260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Mevorach D, Anis E, Cedar N, Bromberg M, Haas EJ, Nadir E, et al. Myocarditis after BNT162b2 mRNA vaccine against covid-19 in Israel. N Engl J Med. 2021;385(23):2140–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Marshall M, Ferguson ID, Lewis P, Jaggi P, Gagliardo C, Collins JS, et al. Symptomatic acute myocarditis in 7 adolescents after pfizer-BioNTech COVID-19 vaccination. Pediatrics. 2021;148(3):e2021052478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Seale H, Heywood AE, Leask J, Sheel M, Durrheim DN, Bolsewicz K, et al. Examining Australian public perceptions and behaviors towards a future COVID-19 vaccine. BMC Infect Dis. 2021;21(1):120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Geipel J, Grant LH, Keysar B. Use of a language intervention to reduce vaccine hesitancy. Sci Rep. 2022;12(1):253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Lim SH, Stuart B, Joseph-Pietras D, Johnson M, Campbell N, Kelly A, et al. Immune responses against SARS-CoV-2 variants after two and three doses of vaccine in B-cell malignancies: UK PROSECO study. Nat Cancer. 2022;3(5):552–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Hirst J, Mi E, Copland E, Patone M, Coupland C, Hippisley-Cox J. Uptake of COVID-19 vaccination in people with blood cancer: population-level cohort study of 12 million patients in England. Eur J Cancer. 2023;183:162–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this article and its online supplementary material. Further enquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.