Abstract

Lead (Pb) is one of the most common heavy metal urban soil contaminants with well-known toxicity to humans. This incubation study (2–159 d) compared the ability of bone meal (BM), potassium hydrogen phosphate (KP), and triple superphosphate (TSP), at phosphorus:lead (P:Pb) molar ratios of 7.5:1, 15:1, and 22.5:1, to reduce bioaccessible Pb in soil contaminated by Pb-based paint relative to control soil to which no P amendment was added. Soil pH and Mehlich 3 bioaccessible Pb and P were measured as a function of incubation time and amount and type of P amendment. XAS assessed Pb speciation after 30 and 159 d of incubation. The greatest reductions in bioaccessible Pb at 159 d were measured for TSP at the 7.5:1 and 15:1 P:Pb molar ratios. The 7.5:1 KP treatment was the only other treatment with significant reductions in bioaccessible Pb compared to the control soil. It is unclear why greater reductions of bioaccessible Pb occurred with lower P additions, but it strongly suggests that the amount of P added was not a controlling factor in reducing bioaccessible Pb. This was further supported because Pb-phosphates were not detected in any samples using XAS. The most notable difference in the effect of TSP versus other amendments was the reduction in pH. However, the relationship between increasing TSP additions, resulting in decreasing pH and decreasing Pb bioaccessibility was not consistent. The 22.5:1 P:Pb TSP treatment had the lowest pH but did not significantly reduce bioaccessible Pb compared to the control soil. The 7.5:1 and 15:1 P:Pb TSP treatments significantly reduced bioaccessible Pb relative to the control and had significantly higher pH than the 22.5:1 P:Pb treatment. Clearly, impacts of P additions and soil pH on Pb bioaccessibility require further investigation to decipher mechanisms governing Pb speciation in Pb-based paint contaminated soils.

Keywords: Contamination, Remediation, Lead, Phosphorus, Immobilization, Bioaccessible

GRAPHICAL ABSTRACT

1. Introduction

Lead (Pb) is a ubiquitous heavy metal in the urban soil environment with well-known toxicity to humans, and especially children (CDC, 2022b; Ryan et al., 2004). Approximately half a million children in the U.S. have blood Pb concentrations above the CDC’s recommended threshold of 3.5 μg/L (CDC, 2022a). A common exposure pathway is inhalation and/or inadvertent ingestion (especially children) through hand-to-mouth activity of Pb contaminated dust (Mielke and Reagan, 1998; Zia et al., 2011), which is often contaminated via weathering of Pb-based paint from buildings and subsequent deposition into surrounding soils (Mielke and Reagan, 1998; O’Connor et al., 2018; Thompson et al., 2014; Turner and Lewis, 2018; Wu et al., 2010). Once Pb enters the soil, it reacts to form compounds of various mobilities and bioavailabilities. Thus, controlling soil Pb mobility and reducing the quantity of bioavailable soil Pb is critical in preventing Pb exposure and reducing the deleterious effects of Pb to humans and the environment.

The use of Pb in paints became popular because of its ability to make paints more durable, improve adherence to substrates/surfaces, enhance colors, and help paint stay tough and flexible relative to non-Pb amended paints. Lead-based paint use in the U.S. legally ended in 1978; thus, there is a higher chance of Pb contamination in soil surrounding buildings built pre-1978 from weathering/chipping of the paint and subsequent deposition in surrounding soils than younger/newer buildings (O’Connor et al., 2018). Moreover, Pb can quickly transform into relatively soluble and mobile cerrusite (PbCO3; Ksp ≈ 10−12.8) and more sparingly soluble and mobile hydrocerrusite (Pb3(CO3)2(OH)2; Ksp ≈ 10−24.1), which are common Pb compounds associated with Pb-based paint contamination in soils (Mendoza-Flores et al., 2017; Ruby et al., 1994; Sowers et al., 2021; Traina and Laperche, 1999). Therefore, remediation techniques must be implemented to stabilize and immobilize soil Pb contaminated by Pb-based paints to prevent further environmental degradation.

Immobilization techniques involving the addition of P amendments to Pb-enriched soils is a widely accepted strategy used to shift Pb species from mobile and bioavailable forms to strongly bonded Pb-phosphate complexes or insoluble Pb-phosphate minerals (Hettiarachchi and Pierzynski, 2004; Mahar et al., 2015; Mendoza-Flores et al., 2017; Palansooriya et al., 2020; Scheckel et al., 2013; Zeng et al., 2017). Experimentation of phosphorus treatments on soil Pb contamination suggest that soluble P amendments (e.g. H3PO4, triple superphosphate, ammonium/diammonium phosphate, etc.) and low pH create efficient conditions to reduce the bioavailability of Pb in soils due to the formation of highly immobile Pb-phosphates that can form upon P addition to Pb-enriched soils (Cao et al., 2002, 2008; Huang et al., 2016; Knox et al., 2006; Obrycki et al., 2016; Ruby et al., 1994; Seshadri et al., 2017; Zhu et al., 2004). For example, chloropyromorphite (Pb5(PO4)3Cl) is a highly stable Pb-phosphate across the typical pH range of most soils [pH ≈ 3–7; Ksp ≈ 10−25.05 (Lindsay, 1979); pH ≈ 7.21–12 Ksp ≈ 10−46.9 (Baker, 1964)] that can form from the addition of P amendments (Baker et al., 2014; Moon et al., 2013; Obrycki et al., 2017; Shen et al., 2018). The majority of studies assessing Pb stabilization using P addition invoke the use of inorganic P amendments (e.g. see studies above) whereas fewer studies have assessed the efficacy of organic P amendments to immobilize Pb in contaminated soils.

Incubation time along with rate of P amendment can have a profound impact on Pb bioaccessibility (Bradham et al., 2018, Cao et al., 2002, 2008; Hettiarachchi et al., 2001; Moseley et al., 2008), a proxy for bioavailability (Judy et al., 2022; Minca et al., 2013; Plunkett et al., 2018; USEPA, 2021), in contaminated soils. It may be expected that bioaccessible lead should decrease with incubation time after P addition, assuming a negligible change in pH, due to continuous immobilization reactions of Pb (Scheckel et al., 2013). However, the results on this are mixed. In a field study conducted by Cao et al. (2002) in Pb-contaminated soil from batteries, data suggested chloropyromorphite formation increased from 0 to 220 d after H3PO4 addition alone or in combination with Ca(H2PO4)2 and decreased from 220 to 480 d. Moreover, the conversion of non-residual to residual Pb increased with the same P additions over the same time period and levelled off after 220 d. Moseley et al. (2008) assessed the impacts of various P amendments [triple superphosphate, rock phosphate, and VolCanaPhos (insoluble natural rock)] at rates of 1%wt to 5%wt on Pb bioaccessibility in Pb-contaminated soil over a period of 365 d. In general, increased P additions decreased bioaccessible soil Pb over time up to one year. The efficacy of Pb bioaccessibility reduction varied by treatment and solid phase Pb-phosphates were not detected in this study; thus, ascertaining the mechanism of Pb retention with P loading over time warrants further investigation.

Cao et al. (2008) and Hettiarachchi et al. (2001) in batch studies, on the other hand, found incubation time of P-treated soil did not enhance the immobilization of Pb in contaminated soil. Incubation time in the Cao et al. (2008) study was up to 28 d and P was added at rates between 0.6%wt to 2.5%wt as Ca(H2PO4)2•H2O to the soil. No decrease was found in bioaccessible (measured by Toxicity Characteristic Leaching Procedure; TCLP) Pb from 1 to 28 d of incubation. This phenomenon was thought to be caused by the fast reaction rate of Pb conversion from cerussite (PbCO3) to Pb hydrogen phosphate (PbHPO4) in the shooting range soils analyzed in their study. Hettiarachchi et al. (2001) found that increases in triple superphosphate, phosphate rock, and phosphoric acid addition (0.25%wt P and 0.5%wt P) to Pb-contaminated soil decreased bioaccessible (measured via Physiologically Based Extraction Test; PBET) Pb after 3 d. Incubation time from 3 to 365 d did not change bioaccessible Pb measurements suggesting that reactions between P and Pb did not change much after the first 3 d of incubation and/or the formation of insoluble pyromorphite was facilitated by the PBET extraction and did not necessarily form under soil incubation conditions. These studies demonstrate the impact of incubation time of P amendments on Pb stabilization in Pb-contaminated soils is not understood and merits further study.

The objective of this study was to assess the influence of P amendments on Pb bioaccessibility in a Pb contaminated soil. Specifically, samples of Pb contaminated soil from a site adjacent to a building painted with Pb-based paint were amended at three P:Pb molar ratios (7.5:1, 15:1, and 22.5:1) with an organic P amendment (bone meal – BM) and two inorganic P amendments (potassium hydrogen phosphate – KP and triple superphosphate – TSP) and incubated for a little over 5 months. Soil pH and bioaccessible P and Pb were measured after 2, 9, 16, 23, 30, 99, and 159 d of incubation at field capacity. These measurements were coupled with extended x-ray absorption near edge (XANES) spectra to elucidate Pb species after 30 and 159 d of incubation.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Materials

2.1.1. Soil sampling and characterization

Approximately 5000 g of soil representing the 0–5 cm depth was obtained from several locations within 0.5 m of the south-facing wall of the Chase Hall building (35.297753, −120.663733) on the California Polytechnic State University, San Luis Obispo campus. Chase Hall was constructed in 1931 and painted with several coats of Pb-based paint of varying Pb concentrations (Montgomery and Mathee, 2004) as pXRF (Vanta M Series, Rh anode, Olympus America, Inc., Waltham, MA) measurements of the south-facing painted wall of this building were on average (n = 10) ≈ 1% Pb (unpublished data). The soil was air-dried, homogenized, and passed through a 2 mm sieve.

The soil type, as mapped by the Natural Resources Conservation Service (2001, 2017), is Los Osos-Diablo Complex. As is typical for the built environment, the native soil was mixed with coarse-grained fill soil that was likely added when Chase Hall was built. The Los Osos soil series is classified as fine, smectitic, thermic Typic Argixerolls. The Diablo soil series is classified as fine, smectitic, thermic Aridic Haploxererts. Characterization data of the sampled soil used in this experiment is found in Supplemental Table 1. The total quantities of Pb and P were 1321.14 ± 64.55 and 693.43 ± 64.55 mg kg-1 soil (n = 7) while the Mehlich 3 concentrations of these elements (n = 7) were 480.83 ± 73.58 mg Pb kg-1 soil and 66.34 ± 4.89 mg P kg-1 soil.

2.1.2. Soil amendments: bone meal, potassium hydrogen phosphate, triple superphosphate

Bone meal (BM), potassium hydrogen phosphate (KP), and triple superphosphate (TSP) were the P amendments used in this study. Bone meal (6–8-0; W. Atlee Burpee & Co., Warminster, PA) is an organic, apatite-rich (Ca5(PO4)3OH) (Glæsner et al., 2019), inexpensive fertilizer derived from slaughterhouse animal bones crushed and ground into a fine powder with relatively low P solubility (Park et al., 2011; Valsami-Jones et al., 1998). The relative abundance of BM coupled with actual and potential shortages of synthetic P sources (e.g. rock phosphate and derived from rock phosphate) worldwide now and in the future, suggest BM is an important P source (Glæsner et al., 2019) that merits investigation in remediation studies like this one. Potassium hydrogen phosphate (K2HPO4, 0–40-54; Mallinckrodt Pharmaceuticals, Inc., St. Louis, MO) is a highly soluble synthetic fertilizer (Ren et al., 2018; W. H. Wu et al., 2013) created from the reaction of H3PO4 with KOH. Triple superphosphate (Ca(H2PO4)2•H2O, 0–45-0; Easy Peasy Plants, Inc.,Alvin, IL) is a highly soluble synthetic fertilizer made from phosphate rock mixed with H3PO4 (Hettiarachchi et al., 2001). All fertilizer materials were used as purchased from the suppliers with no pretreatments.

2.2. Methods

2.2.1. Soil treatments

Sieved and homogenized soil was divided into 9 subsamples of 450 g each and placed in stainless steel bowls. Bone meal, KP, and TSP were added to the soil subsamples to produce samples with 7.5:1, 15:1, and 22.5:1 P:Pb molar ratios as these ratios far exceed the P:Pb molar ratio of common Pb-phosphate solid phases (e.g. pyromorphite = 0.6) and are less and within the range of P:Pb molar ratios used in other studies (Cao et al., 2002, 2008; Hettiarachchi et al., 2001; Huang et al., 2016). The concentration of total Pb in soil was assumed to be 1321 mg kg-1 (Supplemental Table 1) as determined experimentally while the concentration of soil P for the purposes of BM, KP, and TSP addition was not considered as the aim was to assess the impacts of added P on soil Pb derived from Pb-based paint and not that of native soil P. After addition of the amendments, the soil samples were hand homogenized in stainless steel bowls for 30 s. Deionized water (DI H2O) was then added to each amended soil to bring the samples to 25%wt moisture, approximately field capacity conditions. Samples were mixed for approximately 25 min until the added water had uniformly wetted the soil. The 450 g subsamples were then split into quadruplicates of 100 g each and placed into inert plastic beakers and covered with Saran™ Wrap (low-density polyethylene), which was attached to the beakers with a rubber band. All samples were stored in the dark at ≈ 25 °C and monitored once per week for moisture loss. Any moisture lost from the samples was reapplied via a spray bottle such that the moisture content was maintained at 25%wt throughout the course of the experiment.

2.2.2. Control soil

Soil samples (n = 7) representing the 0–5 cm depth and within 0.5 m of the south-facing wall of the Chase Hall building were obtained from several locations over approximately 2 years for soil pH, P, and Pb. These samples were used as control samples for this experiment for measurement of soil pH, P, and Pb as explained below.

2.2.3. Soil measurements

Soil pH and bioaccessible Pb and P were measured after 2, 9, 16, 23, 30, 99, and 159 d of incubation in the dark at 25%wt and ≈25 °C.

2.2.3.1. Soil pH.

Soil solutions were prepared at a1:2 oven dry soil equivalent:DI H2O ratios, mixed with a glass stir rod for 5 min, allowed to settle for 5 min, and then soil pH was measured with an Accumet AB150 Potentiometer (Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA) and Accumet Combination Glass Electrode (Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA). Measurements were recorded after the instrument reading had stabilized for a count of 10 s.

2.2.3.2. Bioaccessible P and Pb.

Bioaccessible P and Pb were extracted via the Mehlich 3 (M3; 0.25 M H4NO3, 0.015 M NH4F, 0.2 M CH3COOH, 0.013 M HNO3, 0.001 M (HOOCCH)2NCH2CH2N(CH2COOH)2, EDTA) extraction protocol (Mehlich, 1984). The M3 extraction was largely developed to estimate plant available P (Mehlich, 1984; Pittman et al., 2007), which in this study is referred to as bioaccessible P. Moreover, the M3 extraction has been shown to correlate with estimates of Pb bioaccessibility using USEPA Method 1340 (in vitro bioaccessibilty, IVBA) (Judy et al., 2022; Minca et al., 2013; Plunkett et al., 2018). While, USEPA Method 1340, and by extension the M3 extraction, may not be suitable for assessing IVBA in (phosphate) amended soils (Ryan et al., 2004), it is the only method considered acceptable by the US EPA for measuring IVBA Pb at this time (USEPA, 2021). Specifically, 20 mL M3 extracting solution was added to 2 g oven dry equivalent soil in a centrifuge tube and placed on a reciprocating shaker (Innova 2100 Platform Shaker, New Brunswick Scientific, Midland, ON, Canada) at 180 cycles/min for 5 min. These samples sat for 5 min and were then syringe filtered through 0.45 μm polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF) filters. Filtrates were stored in scintillation vials at 4 °C until analysis on an inductively coupled plasma-optical emission spectrophotometer for analysis of P and Pb (ICP-OES; HORIBA Ultima 2, Jobin Yvon Inc., Edison, NJ).

2.2.4. Pb speciation by X-ray absorption spectroscopy (XAS)

Incubated samples representative of days 30 and 159 were analyzed for Pb speciation using XAS. Lead L3-edge XAS measurements were conducted at the Materials Research Collaborative Access Team (MRCAT) Sector 10-ID beamline at the Argonne National Lab’s Advanced Photon Source (APS) with the synchrotron operating at 7 GeV in top-up mode, and a Si(111) double crystal monochromator was used to select the energies. Samples were prepared as pellets by grinding each sample in an agate mortar and pestle, mixing with polyvinyl propylene (PVP) and pressing each sample in a 7 mm diameter die. Sample pellets were sealed between Kapton tape and mounted on an autosampler rack. Samples were mounted in the beam path at 45° to the incident beam and measured at room temperature. Measurements were conducted simultaneously in transmission with ion chambers and in fluorescence mode utilizing a Lytle detector, all with N2 gas. Each scan was energy calibrated setting the 1st derivative maximum of Pb(0) foil to 13035 eV.

Samples were analyzed by linear combination fitting (LCF) of Pb XAS standards using Athena (Ravel and Newville, 2005). Identification of Pb species and quantification of relative abundances were modelled by LCF of 1st derivative XANES data. Parameters of LCF are −50 to 100 eV from e0, all sample e0 set to 13038 eV, weights restricted to sum to 1, and e0 shift allowed ±0.65 eV, within energy resolution at edge energy. The wellness of fit parameter is reported as R-factor (Kelly, 2009). The inherent error in any LCF analysis is generally accepted to be between 5 and 10% (Gräfe et al., 2014).

2.3. Statistical analysis

The experiment was set up so that at the start of the incubation each treatment had four separate containers (quadruplicates) of 100 g each of treated and moistened soil. Over the course of the experiment, four of the treatments had one of the quadruplicate samples that was compromised as the Saran™ Wrap failed and the soil in that sample subsequently dried out between extractions. When this occurred, that sample was removed from the experiment going forward.

Means of generally four duplicate samples with standard errors (SE) were presented. In six cases, one outlier duplicate sample was excluded from data analysis in a set of duplicates when the measurements of both bioaccessible P and Pb in that duplicate sample were >5 standard deviations from the mean of the other duplicates in the sample set. Two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) coupled with Tukey’s honest significance test (HSD) was used to compare the effects of incubation time, amendment type and amount, and their interaction on the determination of soil pH and the concentrations of bioaccessible P and Pb. Differences between means were assessed using p ≤ 0.05. Each response variable mean (soil pH, bioaccessible P, or bioaccessible Pb) for a given incubation time, amendment type, and amendment amount was compared to mean control values for these response variables (Supplemental Table 1) using general linear regression t-tests. Since multiple t-tests were performed (36), the Bonferroni correction (0.05/# t-tests) was used to assess differences between the control and treatment means and p ≤ 0.0014 was used. All analyses were performed using JMP Statistical Software (JMP 16.0 Pro, 2021; SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC).

2.4. Quality control

Quality assurance and quality control (QC) measures were implemented throughout the course of the experiment in order to produce data of known and defensible quality. The coefficient of variations of the generally quadruplicate measures of pH, bioaccessible P, and bioaccessible Pb ranged from 0.06 to 7.82, 1.61–67.60, 1.34–114.31, respectively. Instrument QC of the pH meter and the ICP-OES fell within acceptable ranges.

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Incubation days 9, 16, 23

Incubation days 9, 16, and 23 were not included in the presentation of data as, with the exception of soil pH in the BM and TSP treated soils, few important changes (p > 0.05) occurred in the determination of bioaccessible P or bioaccessible Pb (Cao et al., 2008; Hettiarachchi et al., 2001) within an amendment type at a given P:Pb molar ratio.

3.2. Soil pH

Phosphorus amendments impacted soil pH in this experiment (Fig. 1). These impacts were largely predicated on the amount and type of amendment with less influence of incubation time. Soil pH measurements from high to low followed the order of BM > KP > TSP and increasing concentrations of P changed pH values according to the P:Pb molar ratios 7.5:1, 15:1, and 22.5:1.

Fig. 1.

Soil pH as a function of incubation time (day). P:Pb molar ratios A) 7.5:1, B) 15:1, and C) 22.5:1. Control pH = 7.16 ± 0.10 (n = 7). Columns with different letters are significantly different (p < 0.05) than each other and columns with an asterisk are significantly different than the control (p < 0.0014). For color reproduction on the web and in print. (For interpretation of the references to color in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the Web version of this article.)

3.2.1. Influence of P amendment type on soil pH

In general, BM addition raised soil pH relative to the control (p < 0.0014) and the other phosphorus amended (KP and TSP) soils (p < 0.05). Mean (±SE) BM, KP, and TSP soil pH values across treatments and treatment days presented in Fig. 1 were 8.13 ± 0.11, 7.37 ± 0.04, and 5.76 ± 0.06, respectively while the control soil pH was 7.16 ± 0.04. The BM soil pH was likely higher than the other treatments and the control because it is rich in poorly crystalline apatite - Ca5(PO4)3OH (Glæsner et al., 2019). Dissolution of apatite consumes protons and releases Ca and P according to Eq. [1] (Lindsay, 1979); thus, raising the pH of a soil depending on the soil’s buffering capacity (Sneddon et al., 2006).

| [1] |

Potassium hydrogen phosphate (KP, K2HPO4) had an alkaline effect on the soil across P:Pb molar ratios on 5 of 12 d of measurement relative to the control (p < 0.0014). Moreover, KP produced soil pH values that were, in general, significantly different and in between those of the BM and TSP amended soils (p < 0.05) when added at P:Pb molar ratios of 15:1 and 22.5:1. The KP amendment is highly water soluble and it’s pH in 1:5 KP:DI H2O is 9.5 (Hong et al., 2010), which is consistent with the predicted pH of in DI H2O based on the thermodynamic equilibrium acid dissociation constants for H3PO4 (Strawn et al., 2020). Additions of KP (K2HPO4) can buffer soil pH via Eq. [2], thereby consuming acid and increasing soil pH.

| [2] |

The addition of TSP (Ca(H2PO4)2•H2O) decreased soil pH relative to the control soil (p < 0.0014) as has been observed by others (Aide et al., 2008; Atuah and Hodson, 2011; Hettiarachchi et al., 2001). Soil pH for TSP amended soils was, in most cases, significantly lower (p < 0.05) than soil pH values in BM and KP amended soils. Triple superphosphate lowers soil pH as a result of release during dissolution, which according to thermodynamic equilibrium acid dissociation constants for H3PO4 (Strawn et al., 2020) would have a pH of ≈4.5 in DI H2O acting as a weak acid, consuming OH−, and lowering soil pH (Eq. (3)) relative to the control soil pH of 7.16

| [3] |

3.2.2. Influence of P amendment amount on soil pH

The P:Pb molar ratios caused predictable changes in soil pH within a P amendment type (BM, KP, TSP) when all incubation days were compiled. As expected, as the concentration of a base-forming (BM and KP) or an acid-forming (TSP) phosphorus amendment increased, soil pH changed correspondingly (Fig. 1) as has been observed by others (Aide et al., 2008; Atuah and Hodson, 2011; Hettiarachchi et al., 2001).

3.2.3. Influence of soil pH on Bioaccessible Pb

Though it was not the aim of the present study to manipulate pH directly, it is widely accepted from sorption envelope and similar studies that the mobility of Pb decreases with increasing soil pH largely due to the increase in negative charge on variable charge soil colloids (e.g. hydroxide) surface functional groups) and subsequent increased Pb2+ sorption and/or due to the formation of Pb solid phases [e.g. Pb(OH)2; Ksp ≈ 10−19.9 and PbCO3; Ksp ≈ 10−12.8 (Appel and Ma, 2002; Ngole-Jeme, 2019; Nguyen and Manning, 2003; Scheckel et al., 2013);]. The interest of the present study in regards to pH was to evaluate how addition of P amendments at varying P:Pb molar ratios changed soil pH, which in turn affected the amount of bioaccessible Pb. The addition of soluble P amendments, like KP or TSP, and soil pH that favors both species (pH < 7.2) and available Pb2+ (pH < 4), creates a soil environment where both P and Pb are available to react and form highly stable Pb-phosphate compounds [e.g. chloropyromorphite (Pb5(PO4)3Cl); Ksp = 10−25.05 (Lindsay, 1979)] in Pb-enriched soils like the one used in this study (Cao et al., 2008; Scheckel et al., 2013). Thus, if soil pH were the only factor to consider, the TSP amended soils at P:Pb molar ratios of 22.5:1 yielded conditions most likely to facilitate the formation of pyromorphite species. As described above, the mean (±SE) TSP P:Pb molar ratios of 15:1 and 22.5:1 produced soil pH values (all incubation days together) of 5.66 ± 0.06 and 5.41 ± 0.06, respectively; whereas the TSP amended soil at a Pb:P molar ratio of 7.5:1 produced mean soil pHs of ≈6.2 while all BM and KP treated soils along with the control had mean pH levels above 7 (Fig. 1). This leads to conditions much less conducive for the formation of Pb-phosphate compounds than the TSP amended soils at high P:Pb molar ratios (Scheckel et al., 2013).

3.3. Bioaccessible P

3.3.1. Influence of P amendment type and amount on bioaccessible P

It was expected that addition of P via BM, KP, and TSP amendments would significantly increase bioaccessible P in the treated soils relative to the control. This was because the range of P added (P:Pb molar ratio of 7.5:1 to 22.5:1) was equivalent to ≈ 1500–4500 mg P kg-1 soil and the soil was only moderately buffered as manifested by the moderate CEC (22.90 cmolc/kg), sandy clay loam texture (Supplemental Table 1), and the fact that the soil allowed for significant changes (p < 0.0014) in soil pH relative to the control (Fig. 1). However, this was only the case for the BM and KP amended soils within the first month after P addition (Supplemental Fig. 1). With the exception of the KP amended soil at the highest P:Pb ratio of 22.5:1, after 30 d of incubation and up to the end of our study (159 d), the moderate buffering capacity of the soil likely lead to the bioaccessible P concentrations becoming similar to the control (p > 0.0014) in all other treatments via soil sorption reactions due in part to phosphate’s high reactivity in soils (Appel et al., 2013). The KP amended soil at a P:Pb molar ratio of 22.5:1 had more bioaccessible P than the control likely due to this amendment’s high solubility and subsequent high availability of P (Park et al., 2011; Valsami-Jones et al., 1998).

The ability of the soil environment to transform Pb to a stable Pb–P phase, like pyromorphite, is critically dependent on the bioaccessibility of P (Eq. (4); Lindsay, 1979).

| [4] |

As previously mentioned in the Moseley et al. (2008) study, increasing the quantity of P added to Pb-contaminated soils decreased the amount of bioaccessible soil Pb when P was added at P:Pb molar ratios from 13.7 to 316, which has been observed by others (Cao et al., 2002, 2008; Hettiarachchi et al., 2001; Huang et al., 2016). Thus, if creating a soil environment with high bioaccessible P concentrations was the main factor being considered for the express purpose of decreasing bioaccessible Pb via the formation of stable pyromorphite species, KP at P:Pb molar ratios of 22.5:1 would be the recommended treatment. However, problems with high levels of available/bioaccessible P may arise if the added P makes its way to a body of water via erosion or leaching, which leads to eutrophication and this was not expressly considered in this study.

3.4. Bioaccessible Pb

3.4.1. Influence of P amendment type on Bioaccessible Pb

The mean (±SE) aggregated bioaccessible Pb concentrations across all incubation days and P:Pb molar ratios for the BM, KP, and TSP amended soils were 352.63 ± 19.88 mg Pb/kg, 393.52 ± 20.80 mg Pb/kg and 298.20 ± 20.09 mg Pb/kg, respectively. The TSP lowered bioaccessible Pb significantly (p < 0.05) compared to KP, while BM was not significantly different than either other amendment (Fig. 2). This is unexpected as KP and TSP are both highly soluble sources of phosphate, while BM is only slightly soluble. It also suggests that the amount of available P was not the most important factor in reducing bioaccessible Pb. Scheckel et al. (2013) identified lowering soil pH as an important factor when using phosphate to immobilize Pb, as dissolving existing Pb-mineral phases increased the rate of reaction for forming new Pb–P phases in their study. Given the acidifying effect of TSP, it likely affected Pb speciation through the dissolution of existing Pb-mineral phases coupled with the subsequent formation of new Pb phases in this soil that were less soluble than those present in the KP and BM treatments.

Fig. 2.

Bioaccessible Pb as a function of incubation time (day). P:Pb molar ratios A) 7.5:1, B) 15:1, and C) 22.5:1. Control bioaccessble Pb = 484.52 ± 90.02 mg Pb/kg (n = 7). Columns with different letters are significantly different (p < 0.05) than each other and columns with an asterisk are significantly different than the control (p < 0.0014). For color reproduction on the web and in print. (For interpretation of the references to color in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the Web version of this article.)

3.4.2. Influence of incubation time and P amendment amount on Bioaccessible Pb

High variability within a given P:Pb ratio and treatment, along with the small p-value (p < 0.00014) necessary for any treatment to be considered significantly different than the control, limited the detection of significant differences. While pyromorphite forms rapidly in solution, it may not be instantaneous in soils (Cao et al., 2002; Moseley et al., 2008; Ryan et al., 2001). All amendments showed similar trends with respect to incubation time and P amendment amount on Pb bioaccessibility (Fig. 2).

Generally, bioaccessible Pb did not differ significantly from the control in all treatments from day 0–30 (p > 0.00014), except for 15:1 TSP on day 2 and 15:1 BM on day 30. Bioaccessible Pb decreased through day 99 and 159 for TSP and KP, but only 7:5:1 and 15:1 TSP on days 99 and 159 and 7.5:1 KP on day 159 were significantly lower (p < 0.0014) than the control soil. Changes in bioaccessible Pb over time for BM varied based on the amount added but did not fluctuate substantially.

Further discussion regarding the amount of amendment added focuses on day 159 of the incubation because no treatment experienced a significant rebounding increase in bioaccessible Pb over time. For BM, the 7.5:1 and 15:1 P:Pb ratios had similar concentrations of bioaccessible Pb, at approximately 280 mg Pb/kg, while the 22.5:1 ratio had a concentration of 360 mg Pb/kg. The 7.5:1 ratio for KP had the greatest reductions in bioaccessible Pb at 130 mg Pb/kg. For TSP, the 7.5:1 and 15:1 ratio had very similar reductions of bioaccessible Pb by day 159 with a concentration of approximately 90 mg Pb/kg. For all amendment types, the 22.5:1 ratio reduced bioaccessible Pb the least, and no treatment was significantly different from the control at this ratio. At least two studies have reported greater reductions in bioaccessible Pb with lower P additions. Obrycki et al. (2016) observed almost double the reduction in bioaccessible Pb using TSP at a P:Pb molar ratio near 12:1 in comparison to a 40:1 ratio. Kastury et al. (2019) saw greater reduction in bioaccessible Pb with lower P additions in two soils when using monoammonium phosphate and one soil when using TSP. Studies have also reported only marginally greater reductions in bioaccessible Pb with increasing amounts of P (Hettiarachchi and Pierzynski, 2002; Tang et al., 2004). In addition, a number of studies have added P at molar ratios in excess of 100:1 of P:Pb and showed reductions of less than 25% of bioaccessible Pb relative to a control (Basta and Gradwohl, 2000; Geebelen et al., 2003; Sanderson et al., 2016). In comparison, the least effective treatment in this study, which was 22.5:1 BM, also lowered bioaccessible Pb by approximately 25% on average, although it was not significantly different than the control. This evidence further supports that decreasing soil pH relative to the control, and not the amount of P added, was the most important factor affecting the reduction in bioaccessible Pb in this study.

3.5. XAS determination solid-phase Pb species

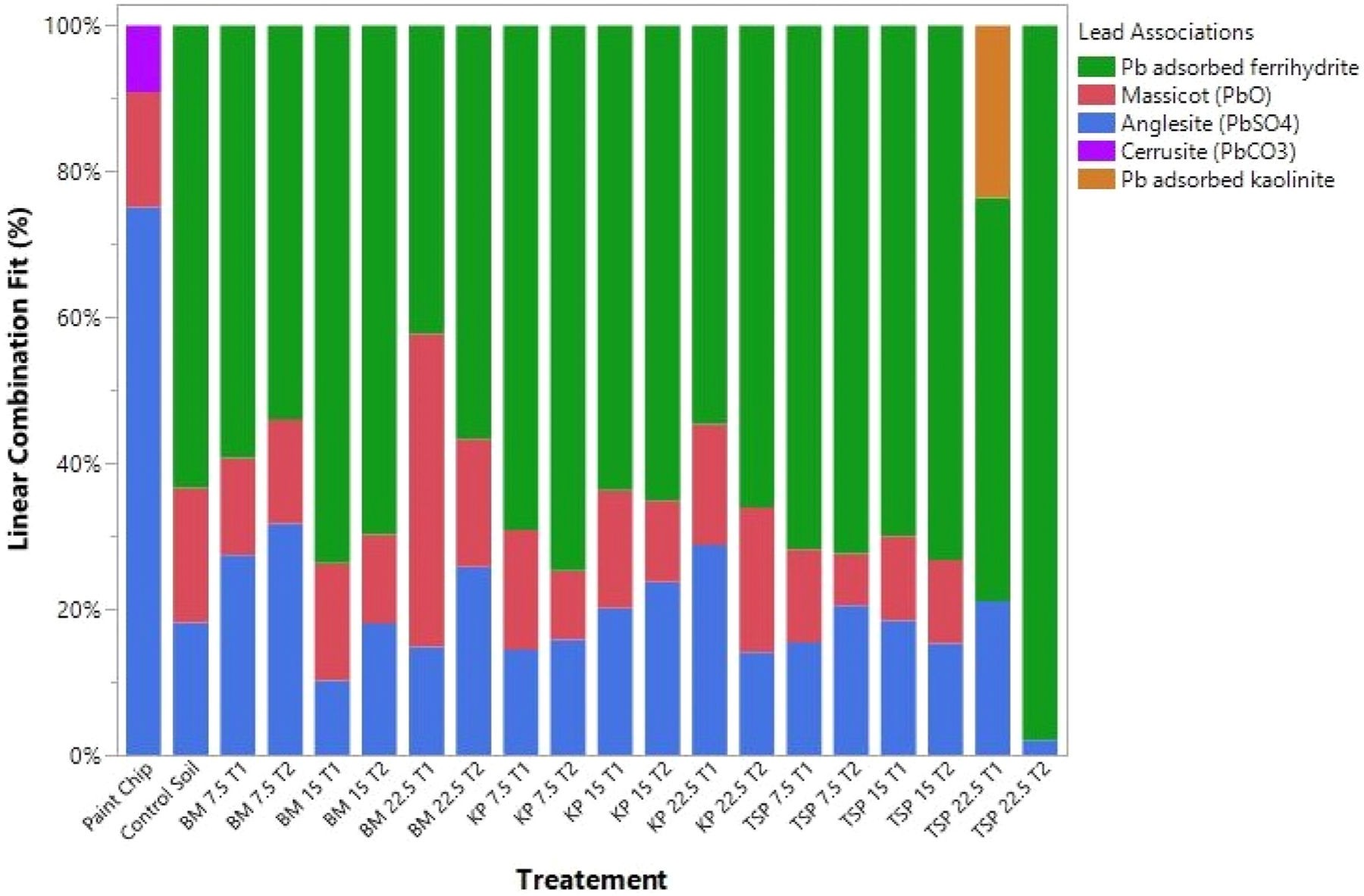

The suspected soil contamination source of Pb in this study was lead paint chips, which contained the lead species anglesite (75.1%), cerussite (9.1%) and massicot (α-PbO) (15.8%) (Fig. 3). Cerussite (PbCO3) has been used as the white pigment in ‘white lead’ and is possibly the Pb species in the original paint. The presence of massicot (β-PbO) can be interpreted as a deliberately used pigment, an impurity derived from ‘red lead’ or, based on Vagnini et al. (2020), a secondary phase from ‘white lead’. Anglesite (PbSO4) is a natural mineral found in oxidized zones of lead deposits, in paint most occurrences are secondary weathering products of the initial Pb paint species (Gliozzo and Ionescu, 2022). The high proportion of secondary products anglesite and massicot to primary phase cerussite in the paint chips indicate the paint had undergone a high degree of weathering and alteration. This alteration process is controlled by environmental parameters, namely humidity, temperature and sulfate concentration, which depend on the oxidative dissolution of atmospheric SO2 (Aze et al., 2007).

Fig. 3.

Pb Linear Combination Fit (LCF) results in soils treated with phosphorus sources bone meal (BM), potassium phosphate (KP), and triple super phosphate (TSP) at incubation times of T1 (30 d) and T2 (159 d) as a function of P:Pb molar ratios 7.5:1, 15:1, and 22.5:1. For color reproduction on the web and in print. (For interpretation of the references to color in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the Web version of this article.)

Samples were measured for Pb speciation at two incubation time points, after 30 d and 159 d (T1 and T2, respectively in Fig. 3). In the control soil, massicot and anglesite were identified but cerussite was not present, replaced by the alteration products of Pb(II) adsorbed to Fe oxides (Fig. 3). Overall, the effects of soil amendments on Pb speciation appeared to be minor and was most significant in high P loading of TSP. This effect appears to be conversion of massicot and anglesite to purely Pb(II) adsorbed to Fe oxides which may have been caused by the lowering of soil pH from TSP additions (Fig. 1b and c) and subsequent dissolution of Pb minerals only observed under high P loading in this treatment (P:Pb = 22.5:1). Other treatments, BM and KP, showed no significant effect on Pb speciation relative to the control. This may have been caused by the relatively unchanged soil pH relative to the control at low P loadings (P:Pb = 7.5:1) and significantly raised soil pH at high P loadings (P:Pb > 15:1), which reduced Pb mobility and reactivity (Appel and Ma, 2002; Ngole-Jeme, 2019; Nguyen and Manning, 2003; Scheckel et al., 2013). As previously mentioned, mean (±SE) combined soil pH values of the 15:1 and 22.5:1 P:Pb molar ratio additions for BM and KP were 8.48 ± 0.10, 7.52 ± 0.04, respectively, which may have prevented acidic dissolution of Pb minerals anglesite and massicot. No evidence for Pb-phosphate minerals was observed in any treatment despite including four related phases (hydroxypyromorphite, lead-adsorbed hydroxyapatite, lead phosphate, and pyromorphite) as candidates in our spectral library.

4. Conclusions

This study examined the ability of bone meal (BM), potassium hydrogen phosphate (KP), and triple superphosphate (TSP), at P:Pb molar ratios of 7.5:1, 15:1, and 22.5:1, to reduce bioaccessible Pb in a soil contaminated by Pb-based paint. The Mehlich-3 extraction procedure was used to measure bioaccessible P and Pb. Soils were incubated for a total of 159 d, with subsamples being collected and analyzed on days 2, 9,16, 23, 30, 99, and 159. Bone meal and KP tended to maintain or increase soil pH while TSP lowered pH relative to the control. Bone meal had the lowest bioaccessible P, followed by TSP, while KP had the highest concentration of bioaccessible P. The greatest reductions in bioaccessible Pb by the end of the incubation were measured for TSP at the 7.5:1 and 15:1 P:Pb molar ratios. The 7.5:1 KP treatment was the only other treatment that showed significant reductions in bioaccessible Pb compared to the control soil. It is unclear why greater reductions of bioaccessible Pb occurred with lower P additions, but it strongly suggests that the amount of P added was not a controlling factor in reducing bioaccessible Pb. This was further supported because Pb-phosphates were not detected in any samples using XAS. The most notable difference in the effect of TSP versus other amendments was the reduction in pH. However, the relationship between increasing TSP additions, resulting in decreasing pH and decreasing Pb bioaccessibility was not consistent. The 22.5:1 P:Pb TSP treatment had the lowest pH but did not significantly reduce bioaccessible Pb compared to the control soil. However, both the 7.5:1 and 15:1 P:Pb TSP treatments significantly reduced bioaccessible Pb relative to the control and had significantly higher pH than the 22.5:1 P:Pb treatment.

It is important to note bioaccessible Pb (M3 in this study) and Pb relative bioavailability (RBA) have been shown to be related in many different lead phases, site conditions, and types of soil (USEPA, 2021). However, in phosphate-amended soils, as evaluated in this study, the relationship between bioaccessible Pb and Pb RBA requires further testing to be validated. Until more lead phases and amendments are assessed by both in vitro and in vivo methods, changes in bioaccessible Pb may be considered to be indicative of directional shifts in bioaccessible Pb and potentially related Pb RBA changes achieved at steady state (Ryan et al., 2004; USEPA, 2021). Thus, further research is needed to develop correlations between these two measures of soil Pb and to better understand the conditions required to form stable Pb-phosphate phases post P amendment application to Pb contaminated soils. This study and others indicated lowering soil pH via acid-forming P application was an important step to create favorable soil conditions for stabilizing Pb via some type of Pb-solid formation, which we predicted to be pyromorphite-like. However, no Pb-phosphate phase was observed in our study (Fig. 3), even after P additions that exceeded the P:Pb molar ratio of pyromorphite by ≈ 12x to 37x. This indicates much research is needed to address the roles of soil pH, bioaccessible P, and if the sequence of these two variables impacts the formation of highly stable Pb-phosphate phases in soils contaminated by Pb paint, which are ubiquitous worldwide.

Supplementary Material

HIGHLIGHTS.

High levels of Pb were found in urban soil near lead-based paint use.

Main decreases in M3 Pb occurred in samples with moderate P (TSP and KP) addition.

Amount P added didn’t control M3 Pb reduction as Pb-phosphates not detected with XAS.

Relationship of increasing TSP, leading to lower pH and lower M3 Pb not consistent.

More research needed to decipher impacts of soil pH and P additions on M3 Pb.

Acknowledgements

The authors gratefully acknowledge Lilly Fulton for her assistance in the design of the graphical abstract as well as several cohorts of Cal Poly Environmental Soil and Water Chemistry undergraduate students who participated in data collection. MRCAT operations are supported by the Department of Energy (DOE) and the MRCAT member institutions. This research used resources of the APS, a DOE Office of Science User Facility operated for the DOE Office of Science by Argonne National Laboratory under Contract No. DE-AC02-06CH11357. Although EPA contributed to this article, the research presented was not performed by or funded by EPA and was not subject to EPA’s quality system requirements. Consequently, the views, interpretations, and conclusions expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect or represent EPA’s views or policies.

Abbreviations:

- BM

Bone meal

- KP

potassium hydrogen phosphate

- TSP

triple superphosphate

- pXRF

portable x-ray fluorescence spectrometer

- Pb

lead

- P

phosphorus

- DI H2O

deionized water

- M3 Pb

Mehlich 3 Pb

- PVDF

polyvinylidene difluoride

- ICP-OES

inductively coupled plasma-optical emission spectrophotometry

- XAS

x-ray absorption spectroscopy

- QC

quality control

- SE

standard error

Footnotes

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Julia Madsen: Writing – original draft, Investigation, Formal analysis, Data curation, Conceptualization. Zoe Dascalos: Investigation, Formal analysis, Data curation, Conceptualization. Kristina Ramsey: Investigation, Data curation. Freddie Mayer: Writing – original draft, Formal analysis, Data curation, Conceptualization. Connie Wong: Writing – original draft, Formal analysis, Data curation. Zach Raposo: Writing – original draft, Formal analysis, Data curation. Rachel Hunter: Writing – original draft, Formal analysis, Data curation. Mac Reinhart: Writing – original draft, Formal analysis, Data curation. Alexandra Carlson: Writing – original draft, Formal analysis, Data curation. Austin Catlin: Writing – original draft, Formal analysis, Data curation. Tanner Mihelic: Writing – original draft, Formal analysis, Data curation. Zoe Pfahler: Writing – original draft, Formal analysis, Data curation. Alec Carroll: Writing – original draft, Formal analysis, Data curation. Kyle Angelich: Writing – original draft, Formal analysis, Data curation. Craig Stubler: Investigation, Formal analysis, Data curation, Conceptualization. Dennis Sun: Formal analysis. Aaron Betts: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Methodology, Investigation, Formal analysis, Data curation, Conceptualization. Chip Appel: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Supervision, Project administration, Methodology, Investigation, Formal analysis, Data curation, Conceptualization.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare the following financial interests/personal relationships which may be considered as potential competing interests:

Aaron Betts reports equipment, drugs, or supplies was provided by US Department of Energy. If there are other authors, they declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chemosphere.2024.142645.

Data availability

Data will be made available on request.

References

- Aide M, Whitener K, Westhoff E, Kelley J, 2008. Effectiveness of triple superphosphate amendments in alleviating soil lead accumulation in Missouri Alfisols. Soil Sediment Contam 17, 630–642. 10.1080/15320380802426533. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Appel C, Ma L, 2002. Concentration, pH, and surface charge effects on cadmium and lead sorption in three tropical soils. J. Environ. Qual 31, 581–589. 10.2134/jeq2002.0581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Appel C, Rhue D, Kabengi N, Harris W, 2013. Calorimetric investigation of the nature of sulfate and phosphate sorption on amorphous aluminum hydroxide. Soil Sci 178, 180–188. 10.1097/SS.0b013e3182979e93. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Atuah L, Hodson ME, 2011. A comparison of the relative toxicity of bone meal and other P sources used as remedial treatments to the earthworm Eisenia fetida. Pedobiologia 54, S181–S186. 10.1016/J.PEDOBI.2011.07.009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Aze S, Vallet JM, Pomey M, Baronnet A, Grauby O, 2007. Red lead darkening in wall paintings: natural aging of experimental wall paintings versus artificial aging tests. Eur. J. Mineral 19 (6), 883–890. [Google Scholar]

- Baker LR, Pierzynski GM, Hettiarachchi GM, Scheckel KG, Newville M, 2014. Micro-x-ray fluorescence, micro-x-ray absorption spectroscopy, and micro-x-ray diffraction investigation of lead speciation after the addition of different phosphorus amendments to a smelter-contaminated soil. J. Environ. Qual 43, 488–497. 10.2134/jeq2013.07.0281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker WE, 1964. Mineral equilibrium studies of the pseudo-morphism of pyromorphite by hinsdalite. Am. Mineral 49, 6–7, 613. [Google Scholar]

- Basta N, Gradwohl R, 2000. Estimation of Cd, Pb, and Zn bioavailability in smelter-contaminated soils by a sequential extraction procedure. J. Soil Contam 9, 149–164. [Google Scholar]

- Cao XD, Ma LQ, Chen M, Singh SP, Harris WG, 2002. Impacts of phosphate amendments on lead biogeochemistry at a contaminated site. Environ. Sci. Technol 36, 5296–5304. 10.1021/es020697j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao XD, Ma LQ, Singh SP, Zhou QX, 2008. Phosphate-induced lead immobilization from different lead minerals in soils under varying pH conditions. Environ. Pollut 152, 184–192. 10.1016/j.envpol.2007.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CDC, 2022a. Blood lead levels in children - lead. https://www.cdc.gov/nceh/lead/prevention/blood-lead-levels.htm.

- CDC, 2022b. Health effects of lead exposure - lead. https://www.cdc.gov/nceh/lead/prevention/health-effects.htm.

- Geebelen W, Adriano DC, van der Lelie D, Mench M, Carleer R, Clijsters H, Vangronsveld J, 2003. Selected bioavailability assays to test the efficacy of amendment-induced immobilization of lead in soils. Plant Soil 249, 217–228. 10.1023/A:1022534524063. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Glæsner N, Hansen HCB, Hu Y, Bekiaris G, Bruun S, 2019. Low crystalline apatite in bone char produced at low temperature ameliorates phosphorus-deficient soils. Chemosphere 223, 723–730. 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2019.02.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gliozzo E, Ionescu C, 2022. Pigments - lead-based whites, reds, yellow and oranges and their alteration phases. Archaeological and Anthropological Sciences 14 (1), 1–66. [Google Scholar]

- Gräfe M, Donner E, Collins RN, Lombi E, 2014. Speciation of metal(loid)s in environmental samples by X-ray absorption spectroscopy: a critical review. Anal. Chim. Acta 822, 1–22. 10.1016/j.aca.2014.02.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hettiarachchi GM, Pierzynski GM, 2002. In situ stabilization of soil lead using phosphorus and manganese oxide: influence of plant growth. Environ. Sci. Technol 31, 564–572. 10.2134/jeq2002.0564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hettiarachchi GM, Pierzynski GM, 2004. Soil lead bioavailability and in situ remediation of lead-contaminated soils: a review. Environ. Prog 23, 78–93. 10.1002/ep.10004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hettiarachchi GM, Pierzynski GM, Ransom MD, 2001. In situ stabilization of soil lead using phosphorus. J. Environ. Qual 30, 1214–1221. 10.2134/jeq2001.3041214x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hong CO, Chung DY, Lee DK, Kim PJ, 2010. Comparison of phosphate materials for immobilizing cadmium in soil. Arch. Environ. Contam. Toxicol 58, 268–274. 10.1007/S00244-009-9363-2/TABLES/3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang G, Su X, Rizwan MS, Zhu Y, Hu H, 2016. Chemical immobilization of Pb, Cu, and Cd by phosphate materials and calcium carbonate in contaminated soils. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res 23, 16845–16856. 10.1007/s11356-016-6885-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Judy JD, Sarchapone J, Gravesen C, Hettiarachchi G, Buchanan C, LaMontagne D, Pachon J, 2022. Correlating soil nutrient test lead with bioaccessible lead in highly-contaminated soils receiving lead-immobilizing amendments. Sci. Total Environ 807 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2021.150658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knox AS, Kaplan DI, Paller MH, 2006. Phosphate sources and their suitability for remediation of contaminated soils. Sci. Total Environ 357, 271–279. 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2005.07.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindsay WL, 1979. Chemical Equilibria in Soils. John Wiley and Sons, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Mahar A, Wang P, Li RH, Zhang ZQ, 2015. Immobilization of lead and cadmium in contaminated soil using amendments: a review. Pedosphere 25, 555–568. 10.1016/S1002-0160(15)30036-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mehlich A, 1984. Mehlich 3 soil test extractant: a modification of Mehlich 2 extractant. Commun. Soil Sci. Plan 12, 1409–1416. [Google Scholar]

- Mendoza-Flores A, Villalobos M, Pi-Puig T, MartÍNez-Villegas NV, 2017. Revised aqueous solubility product constants and a simple laboratory synthesis of the Pb(II) hydroxycarbonates: plumbonacrite and hydrocerussite. Geochem. J 51, 315–328. 10.2343/GEOCHEMJ.2.0471. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mielke HW, Reagan PL, 1998. Soil is an important pathway of human lead exposure. Environ. Health Perspect 106, 217–229. 10.2307/3433922. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minca KK, Basta NT, Scheckel KG, 2013. Using the Mehlich-3 soil test as an inexpensive screening tool to estimate total and bioaccessible lead in urban soils. J. Environ. Qual 42, 1518. 10.2134/jeq2012.0450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moon DH, Cheong KH, Khim J, Wazne M, Hyun S, Park J-H, Chang Y-Y, Ok YS, 2013. Stabilization of Pb2+ and Cu2+ contaminated firing range soil using calcined oyster shells and waste cow bones. Chemosphere 91, 1349–1354. 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2013.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moseley RA, Barnett MO, Stewart MA, Mehlhorn TL, Jardine PM, Ginder-Vogel M, Fendorf S, 2008. Decreasing lead bioaccessibility in industrial and firing range soils with phosphate-based amendments. J. Environ. Qual 37, 2116–2124. 10.2134/JEQ2007.0426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ngole-Jeme VM, 2019. Fire-induced changes in soil and implications on soil sorption capacity and remediation methods. Appl. Sci 9 10.3390/APP9173447. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen QT, Manning BA, 2003. Spectroscopic and modeling study of lead adsorption and precipitation reactions on a mineral soil. In: Cai Y, Braids OC (Eds.), Biogeochemistry of Environmentally Important Trace Elements: Vol. 835. Issue Symposium on Biogeochemistry of Trace Elements Held at the 221st National Meeting of the American Chemical Society. ACS Publications, pp. 388–403. [Google Scholar]

- NRCS, 2001. Official Series Description - Los Osos Series. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Natural Resources Conservation Service. https://soilseries.sc.egov.usda.gov/OSD_Docs/L/LOS_OSOS.html. [Google Scholar]

- NRCS, 2017. Official Series Description - Diablo Series. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Natural Resources Conservation Service. https://soilseries.sc.egov.usda.gov/OSD_Docs/D/DIABLO.html. [Google Scholar]

- Obrycki JF, Basta NT, Scheckel K, Stevens BN, Minca KK, 2016. Phosphorus amendment efficacy for in situ remediation of soil lead depends on the bioaccessible method. J. Environ. Qual 45, 37. 10.2134/jeq2015.05.0244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Obrycki JF, Scheckel KG, Basta NT, 2017. Soil solution interactions may limit Pb remediation using P amendments in an urban soil. Environ. Pollut 220, 549–556. 10.1016/j.envpol.2016.10.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Connor D, Hou DY, Ye J, Zhang YH, Ok YS, Song YN, Coulon F, Peng TY, Tian L, 2018. Lead-based paint remains a major public health concern: a critical review of global production, trade, use, exposure, health risk, and implications. Environ. Int 121, 85–101. 10.1016/j.envint.2018.08.052WE-ScienceCitationIndexExpanded(SCI-EXPANDED)WE-SocialScienceCitationIndex(SSCI). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palansooriya KN, Shaheen SM, Chen SS, Tsang DCW, Hashimoto Y, Hou DY, Bolan NS, Rinklebe J, Ok YS, 2020. Soil amendments for immobilization of potentially toxic elements in contaminated soils: a critical review. Environ. Int 134 10.1016/j.envint.2019.105046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park JH, Bolan NS, Chung JW, Naidu R, Megharaj M, 2011. Environmental monitoring of the role of phosphate compounds in enhancing immobilization and reducing bioavailability of lead in contaminated soils. J. Environ. Monitor 13, 2234–2242. 10.1039/c1em10275c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pittman JJ, Zhang H, Schroder JL, Payton ME, 2007. Differences of phosphorus in Mehlich 3 extracts determined by colorimetric and spectroscopic methods. Commun. Soil Sci. Plan 36, 1641–1659. 10.1081/CSS-200059112. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Plunkett SA, Wijayawardena MAA, Naidu R, Siemering GS, Tomaszewski EJ, Ginder-Vogel M, Soldat DJ, 2018. Use of routine soil tests to estimate Pb bioaccessibility. Environ. Sci. Technol 52, 12556–12562. 10.1021/acs.est.8b02633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ravel B, Newville M, 2005. ATHENA, artemis, hephaestus: data analysis for X-ray absorption spectroscopy using IFEFFIT. J. Synchrotron Radiat 12, 537–541. 10.1107/S0909049505012719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ren J, Zhang Z, Wang M, Guo G, Du P, Li F, 2018. Phosphate-induced differences in stabilization efficiency for soils contaminated with lead, zinc, and cadmium. Front. Environ. Sci. Eng 12 10.1007/S11783-018-1006-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ruby MV, Davis A, Nicholson A, 1994. In-situ formation of lead phosphates in soils as a method to immobilize lead. Environ. Sci. Technol 28, 646–654. 10.1021/es00053a018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryan JA, Scheckel KG, Berti WR, Brown SL, Casteel SW, Chaney RL, Hallfrisch J, Doolan M, Grevatt P, Maddaloni M, Mosby D, 2004. Reducing children’s risk from lead in soil. Environ. Sci. Technol 38, 18A–24A. 10.1021/es040337r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryan JA, Zhang PC, Hesterberg D, Chou J, Sayers DE, 2001. Formation of chloropyromorphite in a lead-contaminated soil amended with hydroxyapatite. Environ. Sci. Technol 35, 3798–3803. 10.1021/es010634l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanderson P, Naidu R, Bolan N, 2016. The effect of environmental conditions and soil physicochemistry on phosphate stabilisation of Pb in shooting range soils. J. Environ. Manag 170, 123–130. 10.1016/j.jenvman.2016.01.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheckel KG, Diamond GL, Burgess MF, Klotzbach JM, Maddaloni M, Miller BW, Partridge CR, Serda SM, 2013. Amendind soils with phosphate as means to mitigate soil lead hazard: a critical review of the state of the science. J. Toxicol. Environ. Health B (16), 337–380. 10.1080/10937404.2013.825216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seshadri B, Bolan NS, Choppala G, Kunhikrishnan A, Sanderson P, Wang H, Currie LD, Tsang DCW, Ok YS, Kim G, 2017. Potential value of phosphate compounds in enhancing immobilization and reducing bioavailability of mixed heavy metal contaminants in shooting range soil. Chemosphere 184, 197–206. 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2017.05.172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen Z, Tian D, Zhang X, Tang L, Su M, Zhang L, Li Z, Hu S, Hou D, 2018. Mechanisms of biochar assisted immobilization of Pb2+ by bioapatite in aqueous solution. Chemosphere 190, 260–266. 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2017.09.140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sneddon IR, Orueetxebarria M, Hodson ME, Schofield PF, Valsami-Jones E, 2006. Use of bone meal amendments to immobilise Pb, Zn and Cd in soil: a leaching column study. Environ. Pollut 144 (3), 816–825. 10.1016/j.envpol.2006.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sowers TD, Nelson CM, Diamond GL, Blackmon MD, Jerden ML, Kirby AM, Noerpel MR, Scheckel KG, Thomas DJ, Bradham KD, 2021. High lead bioavailability of indoor dust contaminated with paint lead species. Environ. Sci. Technol 55, 402–411. 10.1021/acs.est.0c06908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strawn DG, Bohn HL, O’Connor GA, 2020. Soil Chemistry, fifth ed. John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. [Google Scholar]

- Tang XY, Zhu YG, Chen SB, Tang LL, Chen XP, 2004. Assessment of the effectiveness of different phosphorus fertilizers to remediate Pb-contaminated soil using in vitro test. Environ. Int 30, 531–537. 10.1016/j.envint.2003.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson MR, Burdon A, Boekelheide K, 2014. Practice-based evidence informs environmental health policy and regulation: a case study of residential lead-soil contamination in Rhode Island. Sci. Total Environ 468, 514–522. 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2013.07.094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Traina SJ, Laperche V, 1999. Contaminant bioavailability in soils, sediments, and aquatic environments. P. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 96, 3365–3371. 10.1073/pnas.96.7.3365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turner A, Lewis M, 2018. Lead and other heavy metals in soils impacted by exterior legacy paint in residential areas of south west England. Sci. Total Environ 619, 1206–1213. 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2017.11.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- USEPA, 2021. SW-846 Test Method 1340: in Vitro Bioaccessibility Assay for Lead in Soil. U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. https://www.epa.gov/hw-sw846/sw-846-test-method-1340-vitro-bioaccessibility-assay-lead-soil. [Google Scholar]

- Vagnini M, Vivani R, Sgamellotti A, Miliani C, 2020. Blackening of lead white: study of model paintings. J. Raman Spectrosc 51, 1118–1126. 10.1002/jrs.5879. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Valsami-Jones E, Rggnarsdottir KV, Putnis A, Bosbach D, Kemp AJ, Cressey G, 1998. The dissolution of apatite in the presence of aqueous metal cations at pH 2–7. Chem. Geol 151, 215–233. 10.1016/S0009-2541(98)00081-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wu J, Edwards R, He XQ, Liu Z, Kleinman M, 2010. Spatial analysis of bioavailable soil lead concentrations in Los Angeles, California. Environ. Res 110, 309–317. 10.1016/j.envres.2010.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu WH, Xie ZM, Xu JM, Wang F, Shi JC, Zhou R. Bin, Jin ZF, 2013. Immobilization of trace metals by phosphates in contaminated soil near lead/zinc mine tailings evaluated by sequential extraction and TCLP. J. Soil Sediment 13, 1386–1395. 10.1007/S11368-013-0751-X/TABLES/3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zeng GM, Wan J, Huang DL, Hu L, Huang C, Cheng M, Xue WJ, Gong XM, Wang RZ, Jiang DN, 2017. Precipitation, adsorption and rhizosphere effect: the mechanisms for Phosphate-induced Pb immobilization in soils-A review. J. Hazard Mater 339, 354–367. 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2017.05.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu YG, Chen SB, Yang JC, 2004. Effects of soil amendments on lead uptake by two vegetable crops from a lead-contaminated soil from Anhui, China. Environ. Int 30, 351–356. 10.1016/j.envint.2003.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zia MH, Codling EE, Scheckel KG, Chaney RL, 2011. In vitro and in vivo approaches for the measurement of oral bioavailability of lead (Pb) in contaminated soils: a review. Environ. Pollut 159, 2320–2327. 10.1016/j.envpol.2011.04.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available on request.