Abstract

Use of both cannabis and tobacco has surpassed use of tobacco alone among young adults in California. To better understand why, we collected data with 32 young adults ages 18–30 in Northern California who regularly used cigarettes and cannabis and had diverse sexual, gender, racial, and ethnic identities. Geographically-explicit ecological momentary assessment (EMA; 30 days) was integrated with qualitative mapping interviews. We found contrasting situations of use for cannabis (e.g., around other people) versus cigarettes (e.g., recent discrimination) and different reasons for why participants chose one substance over the other (e.g., enhancing experiences vs. stepping away). Understanding when and why diverse young adults choose cannabis versus cigarettes as they navigate everyday environments helps explain how cannabis and tobacco retail markets shape substance use disparities over time.

Keywords: young adults, tobacco, cannabis, ecological momentary assessment, mixed methods

Introduction

The practice of using both tobacco and cannabis (i.e., dual use) is a growing public health concern (Roberts et al., 2022, Cohn et al., 2019). In the United States, daily cannabis use is more prevalent among current cigarette smokers (8.0–9.0%) than former (2.8%) and never (1.1%) smokers (Goodwin et al., 2018). Individuals who use tobacco and cannabis report worse mental (e.g., depression, anxiety) and physical (e.g., headaches, respiratory symptoms) health compared to users of either substance in isolation (Meier and Hatsukami, 2016, Tucker et al., 2019, Nguyen et al., 2023), highlighting the need for research on dual-use practices and motivations.

Hakkarainen and colleagues (2019) ‘drug use repertoires’ and ‘drug use combinations’ terminology is helpful in conceptualizing different forms of dual use. Cannabis and tobacco use ‘repertoires’ refer to the ingestion of both tobacco and cannabis during a particular timeframe, such as a month (Boys et al., 1999). This can include substitution, meaning using one when the other is not available. In contrast, cannabis and tobacco use ‘combinations’ refer to simultaneous ingestion of both substances at the same time (e.g., cigar wrappers filled with cannabis) and sequential use where overlapping psychoactive effects occur (e.g., ‘chasing’ cannabis with tobacco use). This paper aims to understand when and why young adults with cannabis and tobacco use repertoires choose to use one substance over the other as they go about their daily lives.

In California, non-medical cannabis has been commercially available since 2018 (California Office of the Secretary of State, 2016). Just prior to commercial legalization, young adults in California (aged 15–22; 2016–2017) (Nguyen et al., 2019) more commonly reported use of both tobacco and cannabis (7–11%) than of tobacco alone (3–7%), and use of any tobacco product increased the likelihood of cannabis use in all forms. Early research found minimal impact of legalization on the frequency of use among young adults in the state, but increased cannabis use was reported among some groups, particularly women and e-cigarette users (Doran et al., 2021). Additionally, sexual and/or gender minoritized (SGM) individuals in the U.S. have particularly high rates of both cannabis (Barger et al., 2021, Struble et al., 2024) and tobacco use (Li et al., 2021), warranting greater inclusion of this group in research on cannabis and tobacco dual use practices as cannabis markets continue to evolve.

Event-level predictors of cannabis and tobacco use

Ecological Momentary Assessment (EMA) uses in-the-moment assessments multiple times per day of substance use situations to pinpoint drivers of use as they occur in the natural environment. (Shiffman, 2009). Research on event-level predictors of substance use tends to examine tobacco and cannabis use separately, examining event-level tobacco use among those who use tobacco and event-level cannabis use among those who use cannabis. Event-level predictors of tobacco use include negative affect (Cerrada et al., 2016, Shiffman et al., 2007), boredom (Berg et al., 2019), recent alcohol use (Piasecki et al., 2011), socializing/being around other tobacco users (Shiffman et al., 2007), and nicotine craving (Mead et al., 2018, Nguyen et al., 2018). Event-level predictors of cannabis include positive affect (Sznitman et al., 2022), cannabis use disorder symptomology (e.g., craving) (Buckner et al., 2012, Buckner et al., 2015), pain and nausea (Wardell et al., 2023), and peer cannabis use (Phillips et al., 2018).

It is not yet established whether or not the situations and motives of use for cannabis and for cigarettes are the same or different for people who dual use as compared to those who only use one or the other substance. For example, compared to those who only use tobacco, adults in a national U.S. study who use both cannabis and tobacco were more likely to be Black, younger, and have lower income (Cohn and Chen, 2022). Moreover, a study in Southeastern U.S. found that those who co-use cannabis and tobacco were more likely to be older and have more years of cannabis use than those who only use cannabis (Akbar et al., 2019). Given these demographic differences, it is worth exploring whether patterns and motives for use also differ among those who use both products.

A few EMA studies have examined event-level predictors of simultaneous use of cannabis and tobacco, finding associations with perceived reward value and/or synergistic effects (Berg et al., 2018, Thrul et al., 2021, Wilhelm et al., 2020, Chen-Sankey et al., 2019). Less attention has been paid to identifying event-level predictors of tobacco use versus cannabis use among persons using both substances. For example, how do the situational characteristics (e.g., location) and internal states (e.g., affect) that incline an individual to smoke a cigarette compare to those factors that influence the same individual to use cannabis instead?

Experiences and motives of cannabis and tobacco use

A handful of qualitative and mixed methods studies have begun to understand young adults’ motives for using both cannabis and tobacco (Berg et al., 2018, McDonald et al., 2016, Pedersen et al., 2021, Popova et al., 2017, Schauer et al., 2016, Seaman et al., 2019). These include liking the act and sensory experience of smoking (Schauer et al., 2016). Motives for sequential use include feeling triggered by habit and/or addiction, enhancing the cannabis high, and counterbalancing the psychoactive effects of one substance with the other. Reasons for substituting include wanting to smoke something rather than nothing, limitations on when/where tobacco or cannabis can be used, and attempting to quit or cut down use. Young adults may choose one substance over the other in different social contexts (Berg et al., 2018), and motives specific to each substance may also shape when young adults choose to use cannabis versus tobacco. For example, young adults report that cannabis is better suited than tobacco to the role of coping with depression and anxiety, for medicinal purposes (e.g., attention-deficit disorder), and to feeling more connected to one’s internal world and/or external things or activities. Tobacco, on the other hand, is experienced as useful for ‘neutralizing’ bad moods.

Clarity is still lacking regarding: (1) Event-level, situational predictors of young adults’ use of one substance over the other; and (2) The place-based roles that these substances can play for young adults as they navigate the social contexts and routines of their everyday lives. To this end, the current study employed a geographically-explicit ecological momentary assessment mixed method (AUTHOR et al., 2018) with diverse young adults in Northern California, USA, who use both substances to quantitatively investigate event-level internal and external predictors of cannabis use versus tobacco cigarette use and to qualitatively identify the use contexts and experiences that may help explain why one substance is chosen over the other.

Methods

Procedure

The design and use of this EMA mixed method is reported elsewhere (AUTHOR et al., 2018, 2019, 2021), including a mixed methods integration figure (AUTHOR et al., 2018). The current study was conducted in the San Francisco Bay Area, California in 2019 and 2020. It followed an explanatory, sequential mixed methods design (Curry and Nunez-Smith, 2014, Creswell and Clark, 2017) wherein geographically-explicit EMA data were integrated into subsequent qualitative mapping interviews to quantitatively characterize the types of situations that participants frequently used cannabis versus cigarettes, and qualitatively identify the place-based experiences and motives of use that may help explain those use patterns.

At baseline, participants completed an online survey regarding demographics, smoking history, and other health behaviors, including substance use. Participants then began a 30-day EMA phase and were asked to report every time they smoked a cigarette (cigarette reports) or used any type of cannabis product (cannabis use reports) immediately before smoking/using. They did so by pushing a button on the study app which randomly prompted them to complete an assessment (up to 2 smoking surveys and up to 2 cannabis use surveys per day). Participants were also prompted randomly to complete surveys in non-use situations (2 random surveys). To limit participant burden, participants were sent a maximum of 6 EMA surveys total per day. Participants were asked to differentiate between tobacco products in their cigarette reports, but situational sampling focused exclusively on combustible cigarettes and did not differentiate between cannabis products or route of administration to limit participant burden. Lastly, participants completed a retrospective survey each morning reporting their cigarette and cannabis use from the day prior (daily diaries). The study app collected continuous location tracking data throughout the 30-day EMA period and participant responses were logged with Global Positioning System (GPS) coordinates. All data were time and date-stamped. For the current study, only cannabis use surveys and cigarette smoking surveys were analyzed.

Upon completion of the EMA data collection period, participants’ EMA data were visualized in ArcGIS to create map layers of where participants went during the data collection period (using passive location tracking data) and where they reported high cravings, and use of cannabis and cigarettes. Map layers were made for the entire 30-day EMA data collection period, one weekday, and one weekend day as close to the interview date as possible.

Semi-structured, in-depth interviews were held as close to EMA data collection completion as possible (range: 1–7 days) and lasted about an hour. Interviews with culturally-competent SGM-identified team members (AUTHOR and AUTHOR) were conducted in person until COVID-19 restrictions required us to conduct the interviews via share screen on Zoom. During interviews, the participant was shown the map layers of their EMA data in Google Earth following the order and question prompts in the interview guide. The interview protocol is described in greater detail below. Incentives of up to $180 in electronic gift cards were provided based on compliance with study procedures. Ethics approval for this study was granted by the [UNIVERSITY] Institutional Review Board.

Participants

Participants were recruited through Facebook, Instagram, and physical flyers distributed to local SGM-serving organizations. Ads contained a link to the study’s Qualtrics eligibility survey. Eligible participants were 18–30 years of age, currently smoked cigarettes weekly and used cannabis weekly, and made daily use of a smartphone with GPS capabilities. Participants with SGM identities were oversampled to facilitate comparative analyses between sexual and gender identity groups. Electronic informed consent was obtained on the study’s website. Eligible participants were required to send a picture of their ID to verify their identity.

Overall, 221 individuals met inclusion criteria, 87 completed informed consent, 45 completed the baseline assessment, and 37 responded to at least one EMA survey. One additional individual was excluded due to completing only a single EMA survey. 32 participants with medium or high EMA data collection compliance (completed >50% of prompted EMA surveys) were invited to and completed qualitative interviews. Included participants differed from those excluded from analysis after baseline completion on sexual orientation (Fisher’s Exact Test p=.040), with more included participants identifying as gay/lesbian or bi/pan/queer. There were no significant differences on any other demographic characteristics or baseline substance use (data not shown).

Measures

Outcome variables (EMA).

Cannabis use surveys (triggered by cannabis use reports) of real-time cannabis use situations were compared to cigarette smoking surveys (triggered by cigarette reports) of real-time cigarette smoking situations. Therefore, we created a binary outcome variable of cannabis use vs. cigarette smoking.

Independent variables (EMA).

Based on several theories of smoking motives (Best and Hakstian, 1981, Russell et al., 1974) and previous EMA studies (Shiffman et al., 2009, Thrul et al., 2014), we developed items capturing cannabis use and cigarette smoking antecedents in naturalistic settings. Each EMA survey asked about both internal and external factors of the situation the participant was in the time of the survey.

Five items were used to assess internal factors including affect, arousal, craving intensity (separate questions for cannabis and cigarettes/tobacco), and level of intoxication (“Intoxicated and/or drunk?”). The response for each item was coded on a 7-point Likert scale (from 1-Very unpleasant to 7-Very pleasant for affect; 1-Very low to 7-Very high for arousal and craving intensity; and 1-No!! to 7-Yes!! for intoxication).

External situational factors included whether smoking of cannabis or cigarettes was forbidden at the participant’s current location (yes/no), type of current location (e.g., work, home), and current activity (e.g., working, inactivity). Moreover, participants were asked about the presence of others (e.g., alone, unknown person, family member), the number of others present (1, 2–4, 5–20, and more than 20), and if these other persons were smoking cigarettes (yes/no) or using cannabis (yes/no), and the number of others who were smoking cigarettes (1, 2–4, 5–20, and more than 20) or using cannabis (1, 2–4, 5–20, and more than 20). To approximate a continuous number of other smokers for analysis, midpoints of categories were used and 23.5 was used for the highest category, as suggested by previous EMA studies (Thrul and Kuntsche, 2015, Thrul et al., 2017). Participants were also asked whether specific cannabis or tobacco use triggers were present (e.g., seeing a cannabis or tobacco product). Finally, participants were asked if they had experienced any discrimination since the last survey (yes/no), and if endorsed, two follow up questions about the main reason for discrimination (e.g., age, gender, race/ethnicity, etc.) and who discriminated against them (e.g., family member, stranger, acquaintance, employer, etc.). There were a limited number of endorsements of experiences of discrimination and most pertained to race, ethnicity, or nationality. Thus, reasons for discrimination were grouped into two categories: 1. Race, ethnicity, or nationality; and 2. Other reasons. Responses to the question of who discriminated against them were dichotomized into stranger vs. familiar person.

Baseline characteristics.

All of the following variables were assessed in the baseline survey. Data on demographic characteristics included age (continuous), gender (male, female, trans/other), sexual orientation (straight, gay/lesbian, bi/pan/queer), education (no college or dropped out, in college or graduated), and race/ethnicity (non-Hispanic (NH) White, NH Black, NH Asian, Hispanic, NH other/multi-racial).

Additionally, we assessed self-reported cigarette smoking and cannabis use behaviors. For cigarette smoking we assessed number of days of smoking in the past 30 days and number of cigarettes per smoking day. Time to first cigarette (smoking a cigarette within first 30 minutes of waking v. smoking first cigarette more than 30 minutes after waking) was included as a measure of nicotine dependence. We also assessed any use of other tobacco products in the past 30 days for a range of products (cigarillos, smokeless tobacco, hookah, blunts, electronic cigarettes) and combined these into a single variable to reflect any other tobacco use in the past month (yes/no).

We also assessed the number of days of cannabis use in the past 30 days and the average number of times cannabis was used per day, and primary method and form of use, using the DFAQ-CU (Cuttler and Spradlin, 2017). We also assessed any alcohol use and the number of alcohol use days in the past 30 days.

Qualitative mapping interview protocol.

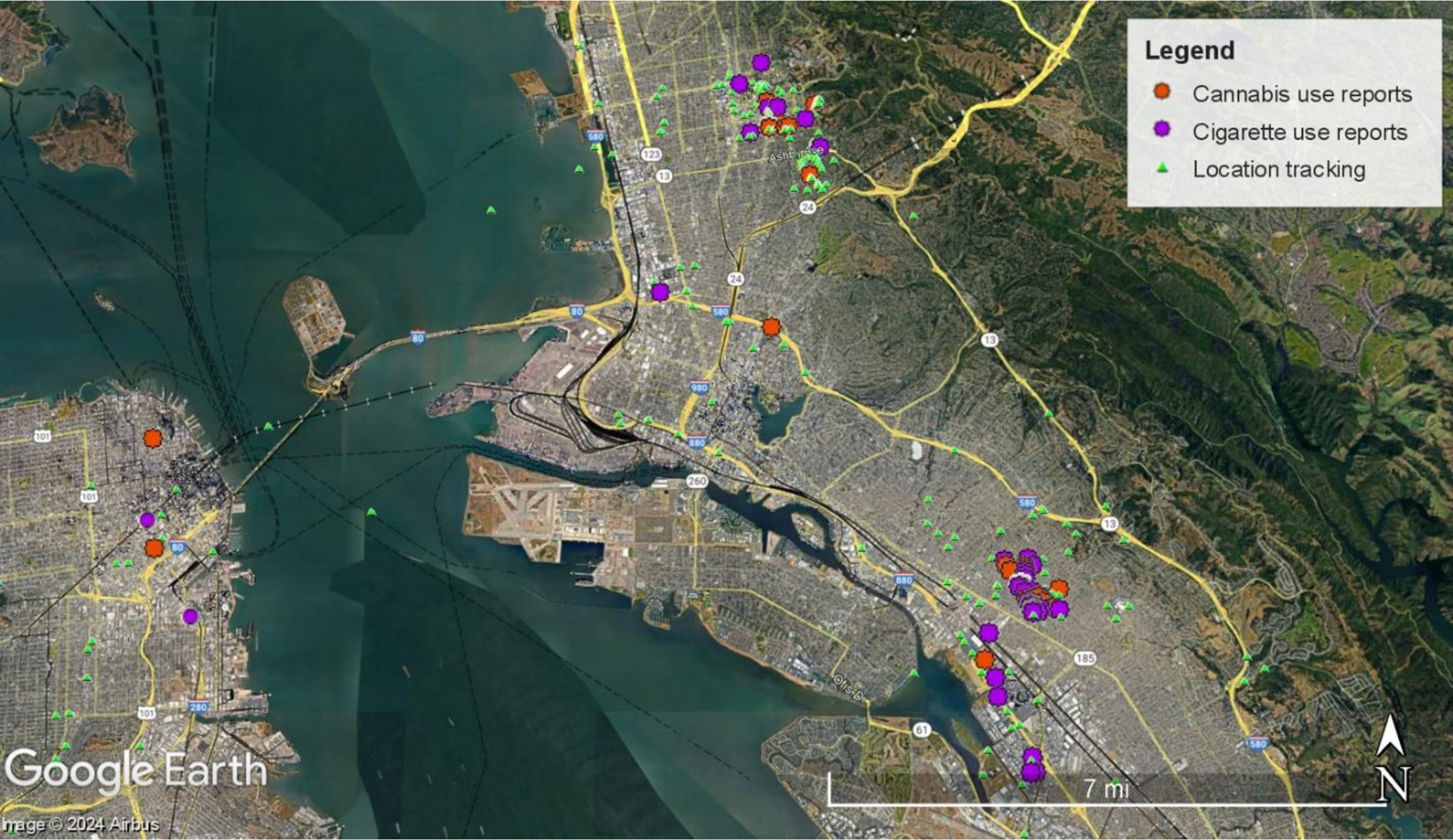

Spatial visualizations of participants’ own EMA real-time self-reports of cigarette and cannabis use were explored and discussed during the interviews on a laptop in Google Earth following a semi-structured interview guide (see Figure 1; data from multiple participants are displayed to protect confidentiality). The interviewer (and/or participant) toggled between and zoomed in and out of the map layers and discussed apparent spatial clusters of cigarette smoking and cannabis use as well as places where participants had spent time but did not report use.

Figure 1:

Cannabis and cigarette EMA reports were displayed in Google Earth during interviews

For example, after viewing and discussing map layers of the participant’s cigarette and cannabis use reports separately, both map layers were pulled up simultaneously. This section of the interview elicited comparison of cannabis and cigarette use places, experiences and practices by toggling between the two layers and provided prompts like: “Do you notice any differences in where you smoke cigarettes versus where you use cannabis? How does it happen that you tend (not) to use cigarettes in the same places and situations as cannabis?” Following review of the map layers showing data from all 30 days of EMA data collection, maps of two recent sample days were shown. The participant was asked to ‘lead’ the interviewer through each sample day, providing vivid ‘play-by-play’ detail of their activities, movements, and experiences, including cigarette and cannabis use and craving.

Data analyses

Quantitative analyses.

Descriptive statistics of baseline characteristics were summarized. To examine situational predictors of cannabis use vs. cigarette smoking (binary outcome), we employed generalized estimating equations (GEE) with autoregressive correlation structure (AR1) to account for the nesting of multiple observations within each participant and the logit link function appropriate for binary outcomes (Zeger et al., 1988, Shiffman et al., 2014). First, we fit unadjusted GEE models to assess crude relationships between predictors and the outcome, followed by adjusted GEE models controlling for potential confounders based on previous research (Nguyen et al., 2018, Shiffman et al., 2009, Thrul et al., 2014). GEE models for internal factors were adjusted for drinking alcohol, the presence of other people smoking cigarettes, and the presence of other people using cannabis. Models for external factors were adjusted for cigarette smoking forbidden, cannabis smoking forbidden, the presence of other people smoking cigarettes, and the presence of other people using cannabis.

Qualitative analyses.

Interviews were audio recorded, transcribed verbatim, and coded in NVIVO. Memos of initial impressions of the data were kept throughout data collection and initial coding. Thematic analysis followed an integrative inductive-deductive approach (Bradley et al., 2007) with the aim of using interview content to help contextualize and explain the quantitative EMA findings. The initial coding scheme was derived from the EMA survey domains and the literature (AUTHOR et al., 2020, AUTHOR et al., 2019, Sanders et al., 2020, Antin et al., 2018) to facilitate integration of the qualitative and quantitative data: (a) type of substance (tobacco product type, as in cigarettes, cannabis, alcohol, MDMA/ecstasy, cocaine, methamphetamine, opioids, other substance), (b) location of use (school/work, partner’s house, friend’s house, walking, car, public transit stop), (c) social identity (sexual identity, gender identity, racial/ethnic identity, socioeconomic status, other social identity), and (d) roles of substance use (e.g., step away from uncomfortable situations, transition between activities, cope with overwhelming emotion, facilitate social interaction, facilitate belonging, stay awake).

[AUTHOR] applied the initial coding scheme to all transcripts. Then, [AUTHOR, [AUTHOR], [AUTHOR], and [AUTHOR] employed a tandem reading method used successfully in the past (AUTHOR et al., 2020) to identify emergent codes for roles of substance use. First, we ranked the transcripts according to semantic richness, meaning the extent to which they provided well-elaborated and rich narrative content relevant to the study aims. Then, in weekly team meetings, we performed tandem readings of content coded for any type of substance use from the 8 richest transcripts to identify additional/emergent roles of use. All 8 transcripts contained content pertaining both cigarette and cannabis use. Then, we finalized the codebook by integrating the emergent codes and applied the final codebook to all 32 transcripts. No additional codes were identified in this final step, indicating saturation.

To identify the niche and overlapping roles of use for cannabis and for cigarettes, we ran frequency queries in NVIVO to identify the extent of overlap of interview content coded for ‘cannabis’ with each of the ‘roles of substance use’ and then repeated this step for ‘cigarette’. We exported query results into Excel and sorted the roles of use for each substance by (a) the number of transcripts containing at least one mention of the role, and then (b) the average number of mentions per transcript. In doing so we identified 10 most salient roles of use for cannabis and for cigarettes.

Mixed methods integration.

The quantitative and qualitative findings were integrated in a mixed methods matrix (O’Cathain et al., 2010, Saldaña, 2012). We listed the statistically significant situational predictors of cannabis use (e.g., with a romantic partner) and of cigarette use (e.g., being alone) according to the EMA data and mapped on the niche roles of use for cannabis (e.g., enhancing experiences) and for cigarettes (e.g., stepping away) to help contextualize and explain the situational predictors of use for each substance. We examined interview content to characterize participants experiences of use situations and explain their tendency to report one substance over the other in those situations. Participant identification numbers are used to protect participant confidentiality.

Results

We first present the quantitative EMA and qualitative interview findings separately and then integrate them in the final section of the Results.

Sample description

The average age of participants was 24.2 years (SD = 3.2). The majority of the sample identified as male (56.2%), 40.6% identified as gay/lesbian, and 25.0% as bisexual/pan/queer. Most of participants (62.5%) were enrolled in college or had graduated. Participants were mostly Non-Hispanic White (43.8%) or Hispanic (37.5%).

Regarding cigarette smoking, 43.8% of participants reported daily cigarette smoking in the past month. The mean number of days of cigarette smoking within the past month was 22.3 (SD=9.1), and the mean number of cigarettes per smoking day was 5.1 (SD=3.5). Cigarette smoking within 30 minutes of waking was reported by 50.0% of participants, and 81.3% reported non-cigarette tobacco product use in the past month.

Regarding cannabis use, 50.0% of participants reported using cannabis daily in the past month. The mean number of days of cannabis use within the past month was 23.5 (SD=9.1). On cannabis use days, the mean number of times cannabis was used was 4.5 (SD=6.1). The most frequently reported primary methods of use were joints (25.0%), bong (21.9%), and hand pipe (15.6%). The primary forms of cannabis use reported were marijuana (78.1%), edibles (12.5%), and concentrates (9.4%). See Table 1 for full breakdown of participant characteristics, including cigarette, cannabis, and alcohol use.

Table 1:

Participant characteristics (N=32)

| Characteristics | Total N (%), M (SD) |

|---|---|

| Demographics | |

| Age (years), mean (sd) | 24.3 (3.3) |

| Gender | |

| Male | 18 (56.2%) |

| Female | 11 (34.4%) |

| Trans/Other | 3 (9.4%) |

| Sexual orientation | |

| Straight | 11(34.4%) |

| Gay/Lesbian | 13 (40.6%) |

| Bi/Pan/Queer | 8 (25.0%) |

| Participants’ highest education | |

| No college or dropped out | 12 (37.5%) |

| In college or graduated | 20 (62.5%) |

| Race/Ethnicity | |

| Non-Hispanic White | 14 (43.8%) |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 3 (9.4%) |

| Non-Hispanic Asian | 1 (3.1%) |

| Hispanic | 12 (37.5%) |

| Non-Hispanic Other/Multi-racial | 2 (6.3%) |

| Smoking history | |

| Daily smoking in past month | |

| Yes | 14 (43.8%) |

| No | 18 (56.2%) |

| Smoking days in past month, mean (sd) | 22.3 (9.1) |

| Cigarettes per smoking day, mean (sd) | 5.1 (3.5) |

| Smoke during 30 minutes of waking | |

| Yes | 16 (50.0%) |

| No | 16 (50.0%) |

| Used any other tobacco in past month | |

| Yes | 26 (81.3%) |

| No | 6 (18.7%) |

| Cannabis use history | |

| Daily cannabis use in past month | |

| Yes | 16 (50.0%) |

| No | 16 (50.0%) |

| Cannabis use days in past month, mean (sd) | 23.5 (9.1) |

| Number of times cannabis use per day, mean (sd) | 4.5 (6.1) |

| Other | |

| Used any alcohol in past month | |

| Yes | 29 (90.6%) |

| No | 3 (9.4%) |

| Alcohol use days in past month, mean (sd) | 9.9 (8.8) |

Real time predictors of cannabis use vs. cigarette smoking situations

Overall, 913 EMAs were analyzed. Of these, 524 (57.4%) were cannabis use situations and 389 (42.6%) were cigarette smoking situations.

Table 2 presents the results of GEE models examining internal predictors of cannabis use vs. cigarette smoking. Participants were more likely to use cannabis when experiencing higher cannabis craving (aOR=1.87, 95%CI=1.49–2.33) and less likely to use cannabis when experiencing higher cigarette or tobacco cravings (aOR=0.60, 95%CI=0.53–0.67). Participants were also more likely to use cannabis with increasing levels of being intoxicated or drunk (aOR=1.22, 95%CI=1.01–1.46).

Table 2:

Internal predictors of cannabis use vs. cigarette smoking situations

| Predictors | Cannabis use n=524 (57.4%) |

Cigarette smoking n=389 (42.6%) |

aOR (95%CI) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Affect, mean (sd) | 4.7 (1.5) | 4.3 (1.6) | |

| Linear | 1.16 (0.99, 1.37)a | ||

| Quadratic | 1.60 (0.93, 2.74)a | ||

| Arousal, mean (sd) | 4.2(1.5) | 4.0 (1.7) | |

| Linear | 1.07 (0.86, 1.33)a | ||

| Quadratic | 1.74 (0.86, 3.52)a | ||

| Craving cannabis, mean (sd) | 5.2 (1.4) | 3.5 (2.1) | 1.87*** (1.49, 2.33)a |

| Craving cigarette or tobacco, mean (sd) | 3.5 (2.0) | 5.2 (1.5) | 0.60*** (0.53, 0.67)a |

| Intoxicated/drunk, mean (sd) | 1.6 (1.1) | 1.4 (0.9) | 1.22* (1.01, 1.46)b |

Note:

p<0.05

p<0.01

p<0.001; aOR: adjusted odds ratio; CI: Confidence interval.

aORs adjusted for recent alcohol consumption, other people present smoking cigarettes and other people present using cannabis.

aORs adjusted for cigarette smoking restrictions at the current location, cannabis use restrictions (smoking) at the current location, other people present smoking cigarettes and other people present using cannabis.

Table 3 presents the results of GEE models examining external predictors of cannabis use vs. cigarette smoking. Regarding location, estimates indicated that participants were more likely to use cannabis in a place where cigarette smoking was forbidden (aOR=2.26, 95%CI=1.16–4.39).

Table 3:

External predictors of cannabis use situations

| Predictors | Cannabis use n=524 (57.4%) |

Cigarette smoking n=389 (42.6%) |

aOR (95%CI) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cannabis smoking ban (vs. permitted) (%) | 23.3 | 22.4 | 1.03 (0.50, 2.11)a |

| Cigarette smoking ban (vs. permitted) (%) | 47.5 | 32.9 | 2.26* (1.16, 4.39)a |

| Location type (%) | |||

| Home | 67.8 | 49.6 | 1.70 (0.94, 3.06)b |

| Workplace | 6.1 | 12.1 | 0.73 (0.42, 1.26)b |

| Vehicle | 3.2 | 9.5 | 0.36 (0.12, 1.08)b |

| Other’s home | 8.2 | 6.4 | 1.17 (0.50, 2.73)b |

| Bar | 1.1 | 2.1 | 0.63 (0.26, 1.55)b |

| Restaurant | 0.4 | 1.3 | 0.37 (0.10, 1.39)b |

| Walking between places | 6.9 | 12.9 | 0.72 (0.38, 1.37)b |

| Public transit stop | 1.5 | 3.1 | 0.66 (0.36, 1.19)b |

| Other place | 4.8 | 3.1 | 1.50 (0.60, 3.77)b |

| Activity (%) | |||

| Working | 16.8 | 22.9 | 0.85 (0.51, 1.40)b |

| Inactive/leisure | 54.6 | 36.8 | 1.66 (0.96, 2.86)b |

| Interacting with others | 17.6 | 12.3 | 1.42 (0.90, 2.23)b |

| Eating/drinking | 11.3 | 7.7 | 1.44 (0.75, 2.76)b |

| Between activities | 27.5 | 34.2 | 0.77 (0.55, 1.09)b |

| Other activity | 5.1 | 5.9 | 0.92 (0.46, 1.87)b |

| Presence of others (%) | |||

| Alone | 55.9 | 71.2 | 0.48*** (0.31, 0.73)b |

| Unknown person | 1.3 | 0.5 | 3.00 (0.94, 9.64)b |

| Family member | 9.9 | 3.1 | 3.63* (1.35, 9.74)b |

| Friends | 16.2 | 13.6 | 0.97 (0.60, 1.56)b |

| Acquaintances | 2.1 | 2.3 | 0.78 (0.30, 2.05)b |

| Coworkers | 4.0 | 5.1 | 1.34 (0.54, 2.38)b |

| Partner | 24.1 | 13.9 | 1.74* (1.04, 2.90)b |

| Number of others present, mean (sd) | 1.3 (2.8) | 1.0 (2.8) | 1.03 (0.97, 1.10)c |

| Presence of others using cannabis (%) | 18.5 | 8.5 | 2.64** (1.39, 5.02)d |

| Number of others using cannabis, mean (sd) | 0.5 (1.8) | 0.3 (1.2) | 1.11 (0.92, 1.34)d |

| Presence of others smoking cigarettes (%) | 11.8 | 9.5 | 0.90 (0.46, 1.76)e |

| Number of others smoking cigarettes, mean (sd) | 0.3 (1.3) | 0.2 (0.8) | 1.06 (0.91, 1.23)e |

| Seen any cannabis use trigger (%) | |||

| Cannabis product | 42.8 | 20.3 | 2.79*** (1.66, 4.68)b |

| Cannabis product packaging | 25.2 | 12.6 | 2.78** (1.25, 3.78)b |

| Media | 3.1 | 2.6 | 1.49 (0.66, 3.40)b |

| Advertisement | 0.6 | 0.8 | 0.68 (0.08, 5.62)b |

| Cannabis smoking | 4.6 | 3.9 | 0.74 (0.32, 1.69)b |

| Other | 9.4 | 6.4 | 1.35 (0.78, 2.35)b |

| Seen any cigarette smoking trigger (%) | |||

| Cigarette | 21.2 | 30.6 | 0.66 (0.40, 1.09)b |

| Lighter | 31.5 | 30.9 | 1.06 (0.60, 1.86)b |

| Cigarette pack | 10.9 | 16.7 | 0.72 (0.36, 1.43)b |

| Ashtray | 17.4 | 12.9 | 1.37 (0.75, 2.49)b |

| Media | 1.2 | 1.5 | 0.64 (0.17, 2.35)b |

| Cigarette smoking | 4.8 | 3.9 | 1.22 (0.79, 1.90)b |

| Other | 2.9 | 4.1 | 0.83 (0.45, 1.54)b |

| Experienced discrimination (%) | 6.3 | 10.0 | 0.54* (0.32, 0.89)c |

| Reason for discrimination (%) | |||

| Race, ethnicity, or nationality | 4.6 | 8.0 | 0.44* (0.24, 0.83)c |

| Other reason | 1.9 | 3.1 | 0.67 (0.28, 1.57)c |

| Experienced discrimination by whom (%) | |||

| Stranger | 5.0 | 8.2 | 0.49* (0.28, 0.86)c |

| Familiar person | 1.0 | 1.8 | 0.51 (0.15, 1.80)c |

Note:

p<0.05

p<0.01

p<0.001; aOR: adjusted odds ratio; CI: Confidence interval.

aORs adjusted for other people present smoking cigarettes and other people present using cannabis.

aORs adjusted for cigarette smoking restrictions at the current location, cannabis use restrictions (modes other than smoking) at the current location, other people present smoking cigarettes and other people present using cannabis. Cannabis use restrictions (smoking) at the current location variable was dropped from this model due to detected multicollinearity.

aORs adjusted for cigarette smoking restrictions at the current location, cannabis use restrictions (smoking) at the current location, other people present smoking cigarettes and other people present using cannabis.

aORs adjusted for cigarette smoking restrictions at the current location, cannabis use restrictions(smoking) at the current location and other people present smoking cigarettes.

aORs adjusted for cigarette smoking restriction at this location, cannabis use restrictions (modes other than smoking) at the current location and other people present using cannabis.

Regarding persons present, participants were less likely to use cannabis compared to smoking cigarettes when they were alone (aOR=0.48, 95%CI=0.31–0.73), but more likely when they were around family members (aOR=3.63, 95%CI=1.35–9.74), or a romantic partner (aOR=1.74, 95%CI=1.04–2.90). They were also more likely to use cannabis vs. cigarettes while around a greater number of people who were using cannabis (aOR=2.64, 95%CI=1.39–5.02).

Regarding external triggers, participants were more likely to use cannabis vs. cigarettes when they had seen a cannabis product (aOR=2.79, 95%CI=1.66–4.68) or product packaging (aOR=2.78, 95%CI=1.25–3.78).

Lastly, participants were less likely to use cannabis compared to smoking cigarettes when they had experienced recent discrimination in general (aOR=0.54, 95%CI=0.32–0.89), discrimination due to their race, ethnicity, or nationality specifically (aOR=0.44, 95%CI=0.24–0.83), or discrimination by a stranger (aOR=0.49, 95%CI=0.28–0.86).

Roles of cannabis and cigarette use in everyday life

Participants’ interviews revealed substantial overlap between the 10 most salient roles of use for cannabis and for cigarettes (Table 4). Seven (7) roles were most salient for both cannabis and cigarettes: Coping with overwhelming emotion (e.g., acute stress), self-soothing (e.g., with boredom), experiencing pleasure or fun, facilitating social interaction and/or belonging, modifying the psychoactive effects of another substance, and helping to structure and pace the spatial and temporal organization of activities during the day. We further examined cannabis and cigarette content coded for ‘modifying the psychoactive effects of another substance’ to determine if the apparent role overlap was actually a reflection of interview content describing cigarettes as modifying the psychoactive effects of cannabis (e.g., chasing a joint with a cigarette). Instead we found that cigarettes and cannabis both played their own roles in modifying experiences of other substances when used simultaneously or in sequence. Cigarettes were most often described as controlling the psychoactive effects of alcohol, cannabis, and less often, other drugs like MDMA and mushrooms, while cannabis was most often described as reducing anxiety while using highly intoxicating drugs (e.g., acid).

Table 4:

Most salient roles for cannabis and cigarettes

| Overlap between cannabis and cigarettes | |

|---|---|

| Coping with overwhelming emotion | Provides immediate comfort in response to overwhelming emotion or crisis |

| Self-soothing | Provides sustained sensory engagement that allows the individual to redirect or focus attention, as in from boredom |

| Pleasure or fun | Pleasure and/or fun are experienced as a result of use |

| Facilitate social interaction or belonging | Provides contact and an excuse to interact with others, a shared experience and a medium of exchange; sense of belonging to community |

| Modify other substance | Intentionally enhance, modify, or otherwise change psychoactive effects of another substance |

| Structuring activities | Shapes the rhythm, pacing, and space-time organization of activities over the course of the day |

| Uniquely salient roles of cannabis | |

| Enhance experiences | Enhances a sensory experience or activity (e.g., makes playing video games or chores more fun; music sounds better or more intense) |

| Therapeutic or medicinal | Mitigates, reduces, or otherwise improves physical ailments and/or their symptoms |

| Space-time opener | Characteristics of the substance allow it to be consumed in places and at times wherein other substances are prohibited/discouraged |

| Uniquely salient roles of cigarettes | |

| Break | Provides a protected time to pause from an activity (e.g., work, studying) |

| Satisfy addiction | Satisfies a physiological craving or urge to use that is related to the need to satisfy addiction after a period of time of not using (e.g., craving a cigarette after the body has cleared a certain amount of nicotine) |

| Step away | Facilitates stepping away from uncomfortable situations (e.g., discrimination) |

Participant narratives also revealed roles that were uniquely salient to cannabis use but not to cigarettes, and vice versa. Unlike cigarettes, cannabis appears especially well-suited to enhancing experiences or activities, providing therapeutic or medicinal benefit, and serving as a space-time opener, meaning characteristics of the substance allow it to be consumed in places and at times wherein other substances are prohibited/discouraged (McQuoid et al., 2020) (McQuoid et al., 2020). Cigarettes were uniquely suited to providing a break or protected time (e.g., from work), satisfying addiction (i.e., physiological cravings or urges), and providing an excuse to step away from uncomfortable situations as they emerge (e.g., discrimination).

Mixed methods integration

The roles of use that appeared uniquely salient for each substance may help explain the differences in situational predictors of cannabis and cigarette use identified in the EMA data. In Table 5, the most salient roles of use for cannabis and cigarettes identified in the interview data are mapped onto the situational characteristics that predicted cannabis use over cigarette use, and those that predicted cigarette use over cannabis use, in order to help explain and contextualize why those situational characteristics were linked to use of one substance over the other.

Table 5:

Situations and roles of use for cannabis and cigarettes

| Ecological Momentary Assessment data | Qualitative mapping interview data | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Situational predictors of use | Salient role(s) of use that help explain predictors | Role definitions | Exemplar quotes |

| Cannabis more likely than cigarette | |||

|

| |||

| Higher cannabis craving | None applicable | n/a | n/a |

|

| |||

| More intoxicated or drunk | Enhance experiences | Use enhances a sensory experience or activity (e.g., makes playing video games or chores more fun; music sounds better or more intense) |

We were out there for a long time not really catching any fish, so we just smoked a joint […] just to, you, know keep us more - just relaxing us. We were already drinking anyway, so just keeping us nice and buzzed. (T021)

It really just depends on my mood, like if I’m trying to go like hard and I just wanna like dance and be wild and fun, that’s when I mix [cannabis and alcohol]. (T021) |

|

| |||

| Cigarette smoking ban | Space-time opener | Characteristics of the substance facilitate use where nicotine/tobacco use is prohibited or discouraged (e.g., indoors, around other people not currently using the substance) | [I]n general I try to be more mindful of where […] I am in relation to people and places when I’m smoking cigarettes compared to weed. […] It seems more harmful to inhale secondhand cigarette smoke than cannabis smoke. And I personally feel more annoyed when I’m inhaling other people’s cigarette smoke when I don’t want to smoke compared to weed. (T025) |

| Therapeutic or medicinal | Use mitigates, reduces, or otherwise improves physical ailments and/or their symptoms; beneficial rather than harmful effects. | I prefer to self-medicate [with cannabis]. I definitely do like counseling. I feel like it definitely helps, you know, take a load off. But at the end of the day I’m not the biggest fan of traditional medicine. (T048) | |

|

| |||

| Family member present Romantic partner present | Space-time opener | See definition above. |

P: No, they [family members] don’t mind that [smoking cannabis indoors]. They actually enjoy the smell of marijuana, so.

I: Okay, yeah. So, it’s sort of accepted at the house – P: It is totally accepted. (T020) |

|

| |||

| Around a greater number of people using cannabis | Enhance experiences | See definition above. | It’s a very social thing. It’s in a group – smoking with a group is completely different experience than smoking by yourself. […] when I smoke in a group with my best friends it’s silly and fun and we’ll play video games and it’ll be a different experience than when you play video games sober. (T026) |

|

| |||

| Saw a cannabis product/product packaging | None applicable | n/a | n/a |

|

| |||

| Cannabis less likely than cigarette | |||

|

| |||

| Higher cigarette or tobacco craving | Satisfy addiction | Use satisfies a physiological craving for the substance |

Because I’m a cigarette smoker, if I don’t have one, yes, I’m going to be stressed but I’m going to find some butts and make my own cigarette, ya know? (T003)

I have a cigarette after I’m done, before I start cooking. […] To prevent the craving later. To not have to worry about it when I’m in the middle of cooking. Like it’s… it’s kind of, like I said it’s compulsive and for efficiency sake like that’s kind of disgusting to think about. I just don’ want to like worry about it while I’m in the middle of cooking. Like, oh, I need to go outside now. (T012) |

|

| |||

| Alone | Break | Use provides a protected time to pause from an activity or situation (e.g., from work) | If I have an essay I’ll like do some of it, take a break, go [outside the college dorm] have a cigarette, come back to it, and then try to finish it. And then, if I finish it, I’ll reward myself with a cigarette. (P074) |

| Step away | Use facilitates stepping away from uncomfortable or overly intense situations |

If I’m like anxious, like my mind is racing a mile a minute, if one of my roommates says something stupid, the immediate response is ‘I really need a cigarette’. Which I don’t, but it’s very calming and relaxing and I’ve definitely trained my brain to think immediately after something bad happens, ‘Oh, a cigarette is going to calm me down’.

So that’s usually when I step out for a cigarette. It’s just to turn off my brain and stop thinking for a little bit. (T026) |

|

|

| |||

| Experienced recent discrimination (general) Experienced discrimination by a stranger Experience recent discrimination due to race, ethnicity, or nationality specifically |

Step away | See definition above. |

P: I’ve used them [cigarettes] to get out of difficult situations, situations that feel difficult, and like if I’m trying to hold on to a sense of like comfort or like, uh, yeah, feeling of, of just a good feeling; trying to like reintegrate that or pull that back into me. […] I’m thinking of like a cocoon or something. Like a safety blanket or something of like putting on some sort of armor-like protection or something. […] If I’m in a situation I can use like ‘I’m gonna go smoke a cigarette’ as an excuse to jet out of there for a second.. (T041)

Working at Hooters, um, when we would get a break or even just get any relief of just being out on the floor with the little purvey guys was smoking a cigarette. So, yea, I’ll go out there and smoke. I started buying packs of cigarettes. (T021) [Reflecting on high smoking rates among SGM communities] I’m Black and Puerto Rican but I don’t feel like I have tons of Black and Puerto Rican friends right now like kicking it with me. And sometimes I feel stupid alone, so maybe they could feel alone. Maybe their journey is different than another gay man or a lesbian woman or whatever their journey is. (T034) |

Situations of cannabis (not cigarette) use

The EMA finding that higher cannabis craving was a predictor for cannabis use over cigarette use was not reflected in the interview discussions wherein participants overwhelmingly described cigarettes as more related to satisfying addiction than cannabis. An exception was participant T025 who described a keen awareness of their cannabis dependence. This participant was a young gay man who moved to San Francisco to escape the homophobic environment of his childhood and started using cannabis to cope with the coming out process:

I think around like February or March I felt there was kind of a – there was kind of a change […] I like felt this need to like smoke just to get high and like it was, like just being sober it was just too much. And I just had to get high to get away from it. And since then, I like, I like developed kind of a habit. […] Maybe if I had grown up in San Francisco in communities that are completely accepting of gay people and like don’t pit like religion against sexuality, maybe I wouldn’t have the same experience and wouldn’t have gone through that period where I felt like I needed to use cannabis to cope with everything kind of coming apart. But, yeah, because I think I still use cannabis because I kind of developed a habit during that time [of coming out]. (T025)

Participants described cannabis as being uniquely suited for enhancing experiences via the sensory alterations from its psychoactive effects, which may help explain the EMA finding that cannabis use was linked to being more intoxicated or drunk. For example, participant T021 described smoking a joint and drinking alcohol with a friend to keep them “nice and buzzed” while fishing on an ocean dock south of San Francisco. For participant T021 mixing cannabis and alcohol was especially suited for enhancing night life experiences where they wanted to “dance and be wild and fun”. In a final example, participant T039 described being ‘crossfaded’ from using cannabis and alcohol at the same time while having fun doing online gaming with friends in a virtual communal space facilitated by video-chat.

The EMA finding that cannabis use was more likely than cigarette use in places where cigarette smoking was forbidden may be partly explained by the space-time opener role that cannabis was described as playing for many participants. Cigarette use is most often banned in indoor environments in Northern California, either officially (e.g., apartment building policy) or normatively (e.g., household members agree not to smoke inside). Cannabis was often described as acceptable for consumption in places like indoors or in public around other people where cigarette smoking is forbidden, as in participant T025’s example of using cannabis rather than cigarettes in a neighborhood park in San Francisco, largely because cannabis secondhand smoke was described as safe or safer relative to cigarette second hand smoke (participant T025), and because the smell does not linger in spaces and materials the way cigarette smoke does. As participant T002 explained it, he and his husband do not smoke cigarettes in their house in the East Bay “[be]cause it like sticks to the paint and your clothes,” but will occasionally smoke cannabis indoors because: “That’s easier to get rid of smell wise.” Moreover, many participants experienced therapeutic or medicinal benefits from cannabis, which likely reinforce the perception of cannabis as safe or safer than cigarettes to consume around others. For example, participant T048 described living with ADHD, anxiety, and substantial financial precarity. When he and his brother’s family were on the verge of losing their rented apartment in the East Bay, he stayed temporarily in a homeless shelter in a neighboring state to work a short-term job that ultimately kept them housed. Within this challenging life context, he prefers to “self-medicate” his mental health symptoms with cannabis and describes himself as “not the biggest fan of traditional medicine.”

These qualities lend cannabis to consumption indoors where much time is spent with family members and/or romantic partners, meaning that the function of cannabis in serving as a space-time opener may also help explain the frequent presence of family members and/or romantic partners, especially when family members and romantic partners also use cannabis. For example, T020 explained that their cannabis use inside their San Francisco apartment remained unchanged during EMA data collection despite having family members visiting them. This was because their family members also smoke cannabis, enjoy the smell, and view it as “totally accepted” for use indoors with loved ones.

Participants described many situations where cannabis helped enhance experiences like hanging out at the park, watching a movie, and doing house chores when family members, partners, and/or friends were present. When these were joint activities, cannabis was often used together to enhance shared experiences, which may help explain the EMA finding of cannabis use being more likely around greater numbers of people using cannabis. For example, participant T026 described using cannabis with other people as a “very social thing” that made activities like playing video games more “silly and fun.” It can be noted that while facilitating social interaction and sense of belonging were highly salient roles for cannabis, this role was also highly salient for cigarette use, reducing its potential to explain this EMA finding.

The interviews did not reveal a role of use for cannabis that would help explain why cannabis use was more likely than cigarette use when participants had seen cannabis products or packaging. However, participants’ narratives about where and how they obtain cannabis sheds light on the importance of cannabis products and marketing to these young adults. Most participants described sourcing their cannabis as pre-rolls, dabs, and other packaged products from brick-and-mortar dispensaries and online deliver services, but a few participants described obtaining cannabis from dispensary employees, ‘pop-up’ dispensaries, and the informal market (i.e., a dealer). The formal (versus informal) cannabis market was largely described as convenient and providing more consistent products that were transparent about their origin and contents. Packaging and other marketing were important to some participants for assessing the product quality, as in the cannabis company “origin story” on product packaging materials that T050 used to judge the quality and safety of the product (e.g., absence of “detrimental additives”).

Finally, the dispensary/cannabis club environment also seemed to shape participants’ perceptions of the products. For example, T002 described a certain cannabis club in San Francisco as “super classy, very chic”, and participant T012 compared an East Bay dispensary where they can “get consistent quality” to an “Apple Store” with the outside covered in greenery and the inside containing orderly, large screens displaying all the products.

Situations of cigarette (not cannabis) use

The EMA finding that cannabis use was less likely than cigarette use in situations where participants experienced higher levels of cigarette or tobacco cravings maps easily onto the qualitative finding that cigarettes were well-suited to the role of satisfying addiction, meaning that participants’ descriptions of many cigarette use situations as they explored their maps seemed more linked to relief of physiological craving for nicotine than any other motive. For example, participant T003, who lives in subsidized housing with her girlfriend and girlfriend’s mother, described becoming “stressed” when she is out of cigarettes and cannot buy more, and at times will make cigarettes from tobacco remains in cigarette butts. Participant T012 described preemptively smoking a cigarette before starting to cook to prevent having to go outside their multi-story apartment building to smoke in the middle of food preparation, describing this planning as “compulsive and for efficiency’s sake.”

In contrast to the highly social contexts that predicted cannabis use over cigarette use, the EMA findings showed cannabis use as less likely than cigarette use when participants were alone. The may be explained by cigarettes’ strong role in taking a break from an activity or stepping away from uncomfortable situations. People usually have to leave their current location to smoke if they are indoors and/or around others and move to a separate location outdoors due to cigarette smoking’s highly regulated and socially discouraged status and public awareness about the dangers of second-hand tobacco smoke.

For example, participant P074 described using cigarette smoking to reward herself and take breaks from writing essays by meeting friends who also smoke at a table under a large tree near the designated smoking area at her university. Participant T026 described how cigarettes allow them to step away from uncomfortable roommate interactions by going outside; they “step out for a cigarette” to “turn off [their] brain and stop thinking for a bit”.

Finally, participants were more likely to report smoking a cigarette than using cannabis when they had recently experienced discrimination of any kind, especially if it was by a stranger, as well as when they had experienced discrimination specifically related to their race, ethnicity, and/or nationality. Discrimination from a stranger is most likely to happen in the public sphere, as in being discriminated against by a customer at one’s workplace. In these situations, cigarettes may have offered a way to step away and escape the uncomfortable situation by moving to a more acceptable location to smoke, such as outside the building or to a designated smoking area. Additionally, the role of coping with overwhelming emotion readily applies to the experience of smoking a cigarette after being discriminated against. While this role was highly salient for both cigarettes and for cannabis, the sheer frequency and intensity of participants’ descriptions of using cigarettes to cope with overwhelming emotion largely outweighed descriptions of using cannabis to cope with overwhelming emotion.

Participant T041 used descriptors like “cocoon,” “safety blanket”, and “armor-like protection” to describe the role cigarettes play to “get out of difficult situations,” in part because cigarettes offer an excuse to physically move to another location due to social norms regarding where and when people can smoke. They contrasted their “habituated” morning cigarette smoked while walking to the bus stop with nighttime cigarettes that were sometimes smoked after stepping outside of their San Francisco apartment building due to “feelings that are not tolerable” related to lost family members. In these situations, the solitary and stationary cigarette smoked on the dark sidewalk provided an opportunity for participant T041 to “recompose myself” and “a sense of stillness that I’m looking for.”

Two participants specifically mentioned gender-related discrimination in relation to their cigarette smoking. Participant T021 described smoking more frequently during her time working at Hooters, a themed restaurant featuring female servers wearing tight and revealing shirts, because taking a cigarette smoking break served to “get any relief of just being out on the floor with the little purvey guys.” Participant T044 linked their own and other transgender individuals’ cigarette smoking to the emotional labor required to educate cisgender people and combat transphobia. T044 described the effort to demand for respect for themselves as a transgender person as a “a weight on my shoulders;” a sense of responsibility to “break [cisgender people] in first” for other transgender people who may not have the confidence or capacity to demand respect for themselves.

While not describing their own personal experiences, three participants linked cigarette smoking to social minority stress related to race and ethnicity, including mention of the intersections of race and ethnicity with sexual orientation. When asked to reflect on the high cigarette smoking rates among SGM communities, participant T034 described their experience as a Black and Puerto Rican person as sometimes feeling “stupid alone,” and suggested that some racially- and ethnically-minoritized SGM people may smoke because they feel the same way. Participant P074 also talked about the unique stressors experienced by racially- and ethnically-minoritized people within SGM communities when asked to comment on high SGM cigarette smoking rates. She gave the example of a report she had read about the cultural pressures that some Asian-American lesbians experience that produce internalized stigma for these individuals. In a final example, participant T034 described another way that racial and ethnic discrimination may influence participants’ cigarette smoking behavior. She described stepping outside of her office building for a smoking break to relieve stress during her job in the Financial District. Because she is “the only Brown and Black girl there” she feels that she cannot be associated with cannabis at work, eluding to the racialized stigma associated with cannabis (Reid, 2020). In part for this reason, she chooses to smoke a cigarette rather than cannabis when stressed at work, explaining: “I already look different, I don’t wanna smell different, too. I just kinda wanted to blend in as much as I can.”

A final point that may help explain the situational predictors of cigarette use according to the EMA data relates to the intoxicating effects of cannabis, which may make the mild psychoactive effects of cigarettes more compatible than cannabis with public places like work or at school. This may incline participants to use a cigarette to cope with discrimination in public rather than cannabis. For example, participant T051 described cannabis as leaving them incapable of going back to work, while they can use nicotine throughout their day “and not feel like there’s a restriction on something that I can do.”

Discussion

This study employed a geographically-explicit EMA mixed method with young adults to quantitatively characterize event-level predictors of cannabis use versus tobacco cigarette use, and to qualitatively contextualize these predictors by eliciting young adults’ descriptions of the contexts and experiences linked to cannabis and cigarette use as they navigate the micro-environments and routines of their everyday lives. In doing so, it was among the first to identify distinct use situations and complementary use motives for cannabis versus cigarettes among people who regularly use both substances, rather than among people who exclusively use one or the other substance. Participants’ EMA data depicted contrasting situational characteristics for cannabis use as compared to cigarette use, with more socially-oriented situations appearing to initiate the choice of cannabis over cigarettes. Cannabis use tended to happen when participants were more intoxicated or drunk, where cigarette smoking was banned, around family, romantic partners or a greater number of people using cannabis, and after they had seen a cannabis product or product packaging. Our findings follow prior EMA studies among cannabis users where peer cannabis use predicted cannabis use (Phillips et al., 2018), but depart from prior EMA findings of positive affect (Sznitman et al., 2022) and illness symptomology (e.g., pain) (Wardell et al., 2023) as cannabis use predictors.

In contrast, for cigarettes, the EMA data showed more solitary, emotionally-distressing situations as aligning with the choice to smoke a cigarette rather than use cannabis. These situations often involved being alone and having recently experienced discrimination, especially by a stranger and with regards to race, ethnicity, or nationality. Our findings are thematically similar to a prior EMA study of tobacco use that identified negative affect (Cerrada et al., 2016, Shiffman et al., 2007) as an event-level predictor of tobacco use, but differ in that we did not find boredom (Berg et al., 2019), recent alcohol use (Piasecki et al., 2011), or socializing/being around other tobacco users (Shiffman et al., 2007) as use predictors of cigarettes over cannabis.

The qualitative mapping interviews offered possible explanations for many of these situational differences between cannabis and cigarette use; they revealed niche roles that each substance appears to play for participants. For example, the social contexts of cannabis use might be explained by the way participants described cannabis as enhancing group experiences (e.g., playing video games with friends). This echoes prior young adult reports that cannabis makes them feel more connected to their internal world and/or external things or activities (Seaman et al., 2019).

Participants also described how the characteristics of cannabis facilitated its use in places like residential homes where cigarettes are typically banned or discouraged, similar to prior findings that young adults may substitute cannabis for tobacco (or vice versa) when there are limitations on when/where each can be used (Schauer et al., 2016). Participants described the smell of cannabis as not lingering like cigarette smell does. They also perceived cannabis smoke as less harmful than secondhand cigarette smoke and many used cannabis for therapeutic or medicinal purposes as observed in prior studies (Seaman et al., 2019). This may reinforce the perception of cannabis as harmless to use around others indoors or in close proximity. The use of cannabis for therapeutic or medicinal purposes echoes prior mixed methods findings on young adult dual use that reported cannabis as better suited than tobacco for coping with symptoms (Seaman et al., 2019).

The niche roles of cigarettes that participants described as they explored maps of their cigarette reports during interviews helped explain why cigarettes were more often chosen than cannabis in more solitary and emotionally-distressing situations. They described cigarettes as useful for creating a protected time or break from activities and as an excuse to step away from uncomfortable situations, as identified in prior studies of young adult tobacco use (AUTHOR et al., 2020, AUTHOR et al., 2019). Given the formal and normative restrictions on where and around whom cigarettes can be smoked (Thompson et al., 2007), it is not surprising that participants often reported smoking alone in their EMA reports. Interview narratives described relocating to places, like outside an office building, to smoke a cigarette to gain reprieve or rest from stressful situations. Participants provided sometimes vivid accounts of the protective qualities of cigarette smoking practices and their utility for escaping upsetting situations. This finding builds upon prior mixed methods findings that young adults perceive tobacco as useful for “neutralizing bad moods” (Seaman et al., 2019).

Experiences of discrimination, especially by a stranger and with regards to race, ethnicity, or nationality, emerged as a specific situational predictor of cigarette use over cannabis use in the EMA data. Although discrimination has been found to share associations with dual use of tobacco and cannabis (Mattingly et al., 2023, Jacobs et al., 2024), use of our mixed-methods approach discovered that cigarettes, specifically, were chosen over cannabis for some dual users in order to step away from environments in which discrimination is experienced.

As our sample was diverse in sexual orientation and gender identity as well as race and ethnicity, it is perhaps surprising that discrimination related to sexual and/or gender identity did not also emerge as a situational predictor of use (Livingston et al., 2017). This may be due, in part, to more accepting attitudes toward SGM people in our San Francisco Bay Area study setting. Moreover, in their interviews, participants provided examples of smoking cigarettes in response to gender discrimination, but not racial or ethnic discrimination. Examples were the cisgender female participant who used cigarette breaks to escape harassment by men at work, and the transgender participant who linked their cigarette smoking to the emotional burden of correcting others’ misconceptions about gender expansive identities. When race and ethnicity were discussed during interviews in relation to cigarette smoking situations, it came up primarily in response to an interview question asking participants to reflect on the disproportionately high smoking rates among SGM people. The entanglements of identity constructs within these responses highlight the importance of engaging with intersectionality in the SGM community when researching substance use disparities (Mereish and Bradford, 2014). It also points to the potential complexities of EMA survey measurement of discrimination due to the intersecting nature of these minoritized identity constructs.

While cannabis and tobacco had unique roles and functions in our participants’ daily lives, interviews also identified several overlapping roles between cannabis and cigarettes (e.g., experiencing pleasure or fun, facilitating social interaction and/or belonging). These add to existing explanations of substitution as a pattern of cannabis and cigarette dual use among young adults (Berg et al., 2018, Schauer et al., 2016, Chen-Sankey et al., 2019, Thrul et al., 2021, Wilhelm et al., 2020), as overlapping roles help explain ways that these substances can be interchangeable in young adults’ everyday lives. However, the rich interview data facilitated a more nuanced understanding of what, at first, appeared to be an interchangeable role between cannabis and cigarettes. ‘Modifying the psychoactive effects of another substance’ emerged as a salient role for both cannabis and for cigarettes in the interview data. Given existing literature, the team at first assumed that most of these use situations would consist of sequential or combined use of cannabis with cigarettes for the purpose of modifying the effects of one or the other substance (Berg et al., 2018). Upon further examination of the interview content, however, it became clear that cigarettes and cannabis both played their own unique roles in modifying experiences of other substances when used simultaneously or in sequence, as in the use of cannabis to reduce anxiety during use of highly intoxicating drugs like acid. Future EMA studies among people who dual use cannabis and tobacco should employ fine-grain survey response options regarding use of cannabis and of cigarettes to modify psychoactive effects of other substances to better understand these use practices.

Cannabis and cigarette use situations were both strongly associated with high level of substance craving in our EMA data. Craving and dependence symptomology were also identified as event-level predictors for cannabis (Buckner et al., 2012, Buckner et al., 2015) and for cigarettes (Mead et al., 2018, Nguyen et al., 2018) in prior EMA studies that have examined these substances in isolation. Our interviews, however, did not entirely reflect this, as participants described a highly salient role for cigarettes in satisfying physiological urges and cravings for cigarettes or tobacco when exploring maps of their use reports, but did not describe the same for cannabis in relieving craving for cannabis. This may be because, while cannabis can be addictive (Zehra et al., 2018), the rates of progression from first use and regular use to use disorder tend to be higher for nicotine than for cannabis use (Wittchen et al., 2008), which may reflect lower reinforcing potential for cannabis compared to nicotine. Thus, while craving was reported in the EMA data for both, our participants’ experiences of nicotine craving may have been more intense and remarkable to them as compared to cannabis. Moreover, the differing social meanings (Blue et al., 2016) and addiction discourses linked to cannabis and tobacco use practices and may also have shaped how participants framed their use experiences during interviews. Cigarettes are now widely perceived as highly addictive, stigmatized, and harmful (Keane, 2014, Thompson et al., 2007, Evans-Polce et al., 2015). Cannabis use practices, on the other hand, have counter-cultural roots in social justice movements, alternative medicine, and spiritual practices (Sandberg, 2013). Therefore, young adults may frame experiences of physiological cravings for cannabis differently and perhaps more favorably than cigarette cravings, leading them to discount experiences of cannabis cravings during interviews.

This divergence of quantitative and qualitative findings regarding cravings speaks to the tensions between emic and etic insights on substance use facilitated by this study’s mixed methods approach. From an etic perspective (i.e., researcher-defined), the quantitative EMA data illuminated patterned relationships between in-the-moment stimuli and behavioral responses, regardless of whether or not participants also perceived these patterns in their use behavior. From an emic perspective (i.e., participant-defined), the qualitative map-led interview data illuminated the sense-making that participants engaged in to understand and explain their own substance use practices in the context of their broader lived experience. While achieving balance and resolving discrepancies between emic and etic perspectives in mixed methods research can be challenging (Perez et al., 2023), these perspectives are both important for identifying, explaining, and understanding patterns of cannabis use versus tobacco use in individuals using both of these substances

Limitations

These findings should be interpreted with the following limitations in mind. First, this study was designed to compare a specific tobacco product (i.e., cigarettes) to all modes of cannabis ingestion (vape, combustible, dab, etc.). This was done to limit EMA data collection burden given the number of EMA surveys that would be required each day to sample use situations for every possible type of cannabis product reported. As a result, the salience of ‘space-time opener’ role for cannabis in interview data may be inflated by the inclusion of edibles and vaped forms of cannabis that are more discreet to use than smoked forms of cannabis. Future studies on event-level predictors of cannabis and tobacco use should examine more specific pairings of tobacco and cannabis products, as in examining tobacco cigarettes and smoked cannabis (e.g., joint, spliff), or vaped tobacco/nicotine and vaped cannabis products, and should include more specific cannabis use questions EMA surveys (products used, route of administration, etc.). Considering the range of cannabis products available in the marketplace in many U.S. states and young adults’ different perceptions toward cannabis products (Nguyen et al., 2022), future studies should collect more detailed information on cannabis products and routes of administration. Second, data were collected with a relatively small sample in single metropolitan area in Northern California among diverse young adults. Future studies should examine how these results may or may not apply to other places and groups of people. For example, while many of our findings on dual use may be transferable to dual use practices of diverse young adults in other settings, the situational predictors and roles of use may differ according to the sociopolitical contexts that young adults are navigating in everyday life (e.g., environments with different levels of stigma against minoritized groups). Third, these findings compare antecedents of cigarette use events versus those of cannabis use events, but do not compare antecedents of non-use events. While antecedents of tobacco use versus no use are already well-examined in literature (e.g., Shiffman et al., 2009), understanding of antecedents of use versus no use of cannabis use is limited, and future research should further examine and compare antecedents of use versus no use for cannabis. Finally, self-report data may be subject to social desirability bias, and real-time cigarette and cannabis use events were underreported compared to the numbers participants indicated at baseline and in daily diaries (data not shown). It remains unclear if this underreporting systematically biased our findings, but future studies may want to employ objective measures for real time data collection of use events, including smart or wearable devices.

Conclusions

The reasons why cannabis and tobacco dual use practices have surpassed use of tobacco alone among young adults in places like California are still poorly understood. This study advances knowledge about cannabis and tobacco dual use practices by providing insight into contrasting situations and roles for cannabis and tobacco cigarettes where young adults choose to use these substances on separate occasions for different reasons, suggesting that the products are not wholly acceptable substitutes for each other. This offers insight into a separate and complementary relationship between these two substances within young adults’ substance use repertoires, in addition to the substitution, simultaneous, and sequential use patterns most often emphasized in the literature. Although discrimination was not a particularly prevalent driver of overall cannabis or cigarette smoking situations, the fact that it was significant in shaping how this diverse group of young adults used one substance over the other signals the need for future research on the situations and motives of dual use practices among diverse populations. Such findings can inform equitable public health and behavioral interventions in places where cannabis retail is increasingly accessible alongside established tobacco retail markets, and inform targets for intervention efforts to reduce co-use of both substances (e.g., target similar antecedents of cannabis and cigarettes) as well as reduce use of single substances (e.g., target unique antecedents of each substance). Finally, contextually-engaged mixed methods, such as the one employed here, may help advance the conceptual and methodological precision of research examining different forms and aspects of cannabis and tobacco dual use practices.

Research Highlights:

Young adult cannabis and tobacco cigarette dual use is prevalent

We explored everyday roles and situations of use for each substance

Real-time surveys, location tracking, and map-led interviews were employed

Findings explain the use of cannabis vs. cigarettes in different situations

Acknowledgements:

We are grateful to the individuals who participated in this study and generously shared their time and experiences with the research team.

Funding:

This project was funded by the California Tobacco Related Disease Research Program (TRDRP; 27IR-0042C, PI: Pamela M. Ling, MD MPH; T29FT0436, PI: Julia McQuoid, PhD). Manuscript preparation was supported by the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA; T32 DA007292), the Oklahoma Tobacco Settlement Endowment Trust (TSET) Grant STCST00400_FY24 and NCI Cancer Center Support Grant P30CA225520 awarded to the Stephenson Cancer Center.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Declaration of interests: None to declare.

References

- Akbar SA, Tomko RL, Salazar CA, Squeglia LM, Mcclure EA, 2019. Tobacco and cannabis co-use and interrelatedness among adults. Addict. Behav 90, 354–361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Antin TM, Hunt G, Sanders E, 2018. The “here and now” of youth: the meanings of smoking for sexual and gender minority youth. Harm Reduct. J 15, 1–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barger BT, Obedin-Maliver J, Capriotti MR, Lunn MR, Flentje A, 2021. Characterization of substance use among underrepresented sexual and gender minority participants in the Population Research in Identity and Disparities for Equality (PRIDE) Study. Subst. Abuse 42, 104–115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berg CJ, Payne J, Henriksen L, Cavazos-Rehg P, Getachew B, Schauer GL, Haardörfer R, 2018. Reasons for marijuana and tobacco co-use among young adults: a mixed methods scale development study. Subst. Use Misuse 53, 357–369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berg CJ, Haardörfer R, Payne JB, Getachew B, Vu M, Guttentag A, Kirchner TR, 2019. Ecological momentary assessment of various tobacco product use among young adults. Addict. Behav 92, 38–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Best JA, Hakstian AR, 1981. A situation-specific model for smoking behavior. The Psychology of Social Situations. Elsevier. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blue S, Shove E, Carmona C, Kelly MP, 2016. Theories of practice and public health: understanding (un)healthy practices. Crit. Publ. Health 26, 36–50. [Google Scholar]

- Boys A, Marsden J, Fountain J, Griffiths P, Stillwell G, Strang J, 1999. What influences young people’s use of drugs? A qualitative study of decision-making. Drugs Educ. Prev. Pol 6, 373–387. [Google Scholar]

- Bradley EH, Curry LA, Devers KJ, 2007. Qualitative data analysis for health services research: developing taxonomy, themes, and theory. Health Serv. Res 42, 1758–1772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buckner JD, Crosby RD, Silgado J, Wonderlich SA, Schmidt NB, 2012. Immediate antecedents of marijuana use: an analysis from ecological momentary assessment. J. Behav. Ther. Exp. Psychiatr 43, 647–655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]