Abstract

The organization and transcriptional regulation of porcine endogenous retrovirus (PERV) long terminal repeats (LTRs) are unknown. We have studied the activity of LTRs from replication-competent molecular clones by performing luciferase reporter assays. The LTRs differ in the presence and number of 39-bp repeats located in U3 that confer strong promoter activity in human, simian, canine, feline, and porcine cell lines, whereas for LTRs devoid of the repeats, the promoter strength was significantly reduced. As the activity of a heterologous simian virus 40 promoter and a homologous repeat-deficient LTR was elevated by four 39-bp repeats independently of its orientation and location, the repeat box complies with the definition of an enhancer. During serial virus passaging of molecular PERV clones on human 293 cells, proviral LTRs demonstrated adaptation of transcriptional activity by dynamic changes of the number of 39-bp repeats in the course of up to 12 passaging cycles.

The discovery of porcine endogenous retroviruses (PERV) (25) and other pig microorganisms, such as herpesviruses (9), has strengthened objections to the clinical use of pig xenografts (11, 21, 28), which is intended to alleviate the limited supply of allografts for the treatment of human disorders. PERV display approximately 50 proviral integration sites in the pig genome (1, 25), and recent reports have demonstrated that PERV which are released from different pig cell lines infect human cells in vitro (19, 25, 34, 33).

The organization and transcriptional regulation of PERV long terminal repeats (LTRs), particularly those of human-tropic viruses, are unknown. We have studied the promoter activity of a number of distinct PERV LTRs in transiently transfected mammalian cell lines by using a Dual-Luciferase Reporter Assay System (Promega, Mannheim, Germany). LTRs were derived from different PERV molecular clones, including those replication-competent and human-tropic viruses that we have described recently (7, 14, 30). LTR sequences of clones 293-PERV-A(42) [hereafter, clones derived from cell line 293 PERV-PK (18) will be referred to as 293-PERV-(A)42, 293-PERV-B(33), 293-PERV-B(43), 293-PERV-B(43)-746, 293-PERV-B(43)-590, 293-PERV-B(43)-Δ, and 293-PERV-B(43)-Zero], 293-PERV-B(33), and 293-PERV-B(43) differ by distinct numbers of a 39-bp repeat box which is located in U3. The existence of repeat elements in viral promoters which often act as enhancer elements is well known (10). In this report, we demonstrate that the level of promoter activity correlates with the number of 39-bp repeat boxes, which fluctuates in the course of serial passaging of PERV in human cells. In addition, the repeat box represents a viral enhancer that modulates the activity of heterologous and homologous promoters.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cloning of PERV LTRs.

LTRs were isolated from replication-competent molecular clones 293-PERV-A(42), 293-PERV-B(33)/ATG, 293-PERV-B(43) (7), and PK15-PERV-A(58) (14) by PCR using oligonucleotides 5′-PERV-LTR I and 3′-PERV-LTR/PBS I (Fig. 1). A PERV-C LTR was isolated from minipig genomic DNA by using primers 5′-PERV-C-LTR and 3′-PERV-C-LTR (Fig. 1). To generate LTR 293-PERV-B(43)-Zero lacking the repeat box, primers 5′-PERV-LTR I and 3′-PERV-Zero were used, as well as oligonucleotides 5′-PERV-Zero and 3′-PERV-LTR/PBS I. Both amplification products were fused by PCR using primers 5′-PERV-LTR I and 3′-PERV-LTR/PBS I. The 293-PERV-B(43)-Δ LTR containing one 18-bp subrepeat was produced by using oligonucleotides 5′-PERV-LTR I and 3′-PERV-Del I in a first step. The generated amplification product was used as the template for a PCR using primers 5′-PERV-LTR I and 3′-PERV-Del II in a second step. Together with the amplification product generated by primers 5′-PERV-Del II and 3′-PERV-LTR/PBS I, that second product was fused by using primers 5′-PERV-LTR I and 3′-PERV-LTR/PBS I. The sequences of the oligonucleotides used for PCR are available upon request.

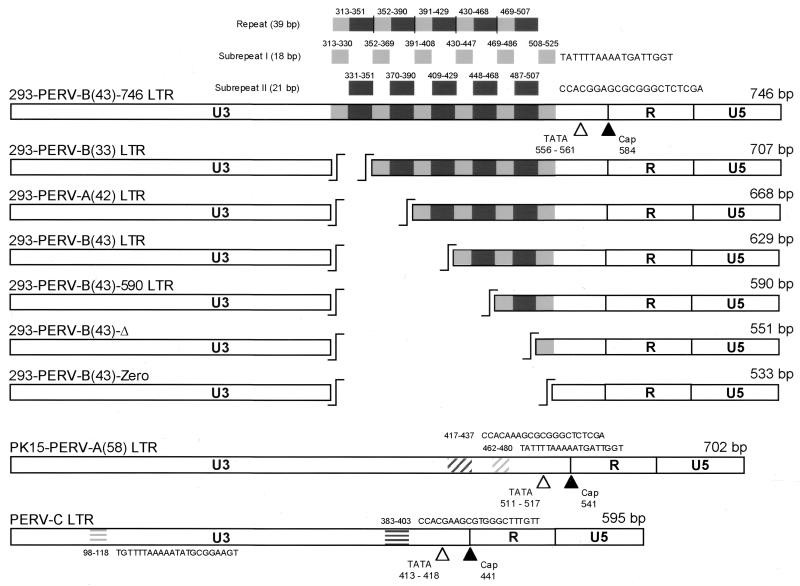

FIG. 1.

Organization and structure of PERV LTRs used for the Dual-Luciferase Reporter Assay. Except for those of the PERV-C, PK15-PERV-A(58), and deletion mutant 293-PERV-B(43)-Zero and 293-PERV-B(43)-Δ LTRs, U3 regions harbor different numbers of the same 39-bp repeat, consisting of an 18-bp subrepeat and a 21-bp subrepeat. U3, R, and U5 are shown as open boxes, and repeats are shown as gray (18-bp subrepeat) and dark gray (21-bp subrepeat) boxes. The cap site (black triangle) and TATA box (open triangle) are indicated. Numbers indicate the locations of elements in the LTRs. Nucleotide positions refer to 293-PERV-B(33) (7).

Construction of expression vectors.

To construct PERV LTR reporter vectors, primers 5′-PERV-LTR II bearing a KpnI site and 3′-PERV-LTR/PBS II bearing a BglII site were used. In addition to the LTRs mentioned above, LTR sequences 293-PERV-B(43)-590 and 293-PERV-B(43)-746 were amplified with the same primers by using as templates PCR products that were generated after serial passages of molecular clones in 293 cells (see below). As a control, a Rous sarcoma virus (RSV) LTR was derived from pREP4 (Invitrogen, Groningen, The Netherlands) by using primers 5′-RSV-LTR and 3′-RSV-LTR, bearing KpnI and BglII sites, respectively. All PCR products were subcloned into pGEM-T Easy (Promega). KpnI and BglII inserts were further cloned into the luciferase reporter vector pGL3 Basic (Promega).

Furthermore, the four 39-bp repeats of the 293-PERV-B(33) LTR (Fig. 1) were cloned into vector pGL3 Control (Promega) (see Fig. 4) in the forward and reverse orientations upstream of the simian virus 40 (SV40) promoter and downstream of the gene for luciferase by using primers 5′-Repeat and 3′-Repeat, both containing KpnI and BamHI or BglII and SalI sites, respectively.

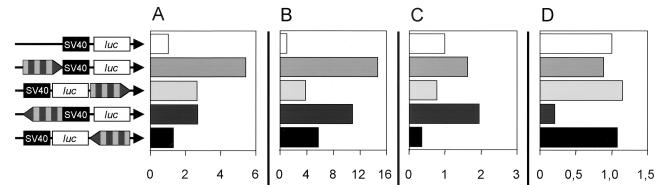

FIG. 4.

Modulation of a heterologous promoter by the 39-bp repeat box. The repeat box was inserted upstream of the SV40 promoter and downstream of the luc gene in both orientations. The mean value of pGL3 Control luciferase activity was set as 1, and the relative increase or decrease for the given construct is shown as fold activation. (A) 293 cells; (B) A3.01 cells; (C) HeLa cells; (D) MRC-5 cells. The SV40 promoter (black box), the luciferase gene (open box), and the 39-bp repeat box (alternately light and dark gray-striped box; arrow indicates orientation) are depicted.

Cloning of the repeat box upstream of the 293-PERV-B(43)-Zero LTR (see Fig. 5) was performed by using primers 5′-Repeat and 3′-Repeat, both containing a KpnI site. Cloning downstream of the LTR was performed by using the same primers containing BamHI and BglII sites, respectively. Those primers were also used for cloning of the repeat box into pGL3 Basic. All PCR amplification products were subcloned into pGem-T Easy. Subsequently, inserts were cloned into the corresponding restriction sites of pGL3 Control, pGL3 Basic/293-PERV-B(43)-Zero, and pGL3 Basic, respectively.

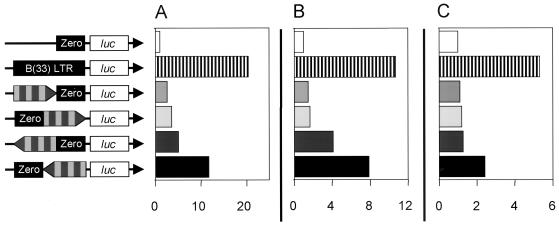

FIG. 5.

Modulation of the homologous promoter 293-PERV-B(43)-Zero LTR by the 39-bp repeat box. The repeat box was cloned into the vector pGL3 Basic/293-PERV-B(43)-Zero upstream and downstream of the PERV LTR in both orientations. The mean value of pGL3 Basic/293-PERV-B(43)-Zero luciferase activity was set as 1, and the relative increase or decrease for the given construct is shown as fold activation. (A) 293 cells; (B) A3.01 cells; (C) HeLa cells. The 293-PERV-B(43)-Zero LTR (black box), the 293-PERV-B(33) LTR (black box), the luciferase gene (open box), and the 39-bp repeat box (alternately light and dark gray-striped box; arrow indicates orientation) are depicted.

Sequence analyses.

DNA sequences of both strands of constructs were confirmed by primer walking with the double-stranded dideoxy-chain termination method using Thermo Sequence fluorescent dye terminator cycle sequencing and precipitation kits (Amersham-Pharmacia, Freiburg, Germany). Sequencing reactions were performed with a Vistra DNA Labstation 625 (Molecular Dynamics, Krefeld, Germany), and cycle sequencing was done on an ABI 373A or 377 DNA sequencing system (Applied Biosystems, Weiterstadt, Germany). Putative transcription factor binding sites were analyzed by using MatInspector software (Genomatix, Munich, Germany).

Cell lines and transfection.

The cell lines 293, ST-Iowa, and PK 15 were kindly provided by R. Weiss (London, England), and cell line A3.01 was obtained from E. Flory at our institute. HeLa cells were purchased from the European Collection of Cell Cultures (ECACC 93021013), as were MRC-5 cells (ECACC 84101801), Cos-7 cells (ECACC 87021302), PG-4 cells (ECACC 94102703), and D17 cells (ECACC 8909043). All cell lines tested negative for mycoplasms. Plasmids used for transfection were prepared by using the EndoFree system (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany). Transfection was carried out with Lipofectamine (Life Technologies, Karlsruhe, Germany) for adherent cells, while DMRIE-C (Life Technologies) was used for the suspension cell line A3.01. Transfection was performed with six-well plates by using 1 μg of plasmid DNA cotransfected with 333 pg of internal standard pRL-CMV (Promega). At 5 h posttransfection, the transfection medium was replaced with appropriate culture medium and the cells were grown for 43 h.

Serial passaging of molecular PERV clones.

Replication-competent molecular clones 293-PERV-B(33)/ATG and 293-PERV-B(43) (7) were used to transfect the human embryonic kidney cell line 293. Cell-free supernatants filtered through membranes (0.45-μm pore size; Sartorius, Göttingen, Germany) were analyzed for reverse transcriptase (RT) activity by using the type C RT activity assay (protocol B; Cavidi Tech AB, Uppsala, Sweden). Cells were tested for expression of viral proteins by an indirect immunofluorescence assay using PERV Gag p10 antibody (15). Supernatants of productively infected cells were transferred to fresh 293 cells every 4 weeks for up to 12 months. At those time points, genomic nuclear DNA was purified from infected 293 cells and integrated proviral LTRs were amplified by PCR using primers 5′-PERV-LTR I and 3′-PERV-LTR/PBS I.

Dual-Luciferase Reporter Assay System.

The Dual-Luciferase Reporter Assay System (Promega) was used to investigate LTR activities. Transfected cells were washed with phosphate-buffered saline and lysed with 300 or 100 μl (adherent or suspension cells, respectively) of passive lysis buffer (Promega) at room temperature for 10 min. Cell lysates were centrifuged at 13,000 × g for 1 min at room temperature, and supernatants were stored at −20°C for testing. The luciferase assay was performed with a MicroLumat Plus LB 96 V (EG&G Berthold, Bad Wildbad, Germany). Each measurement was carried out by using 20 μl of cell lysate after addition of 50 μl of LAR II (Promega) and 50 μl of Stop & Glo (Promega) for a light-counting time of 10 s. For indication of luciferase reactions exceeding the linear range, the luminometer was adjusted to a diagnostic warning level.

Statistical analysis.

For each cell line and each vector, at least three separate transfection experiments were carried out in triplicate. To normalize the activity of the experimental reporter with regard to the activity of the internal control (pRL-CMV), the values of the internal control were set as 1 and the ratio RLUexperimental reporter/RLUpRL-CMV (RLU is relative light units) was calculated. For each triplicate experiment, the mean value and standard deviation were calculated. To assess the modulation of the SV40 promoter and the 293-PERV-B(43)-Zero LTR by insertion of four 39-bp repeats, the mean values of both were set as 1 and the relative increase or decrease in luciferase activity was calculated. Formal statistical comparisons were not performed, as, due to the small number of observations per construct and cell line, the power of the corresponding tests was considered to be too low.

Nucleotide sequence accession numbers.

LTR nucleotide sequences of 293-PERV-B(43)-746 (AJ298073), 293-PERV-B(43)-590 (AJ298074), and PERV-C (AJ298075) have been deposited in GenBank. Clones 293-PERV-A(42) (AJ133817), PK15-PERV-A(58) (AJ293656), 293-PERV-B(33) (AJ133816), and 293-PERV-B(43) (AJ133818) were used for generation of LTRs. PERV-MSL (AF038600) was used for homology studies.

RESULTS

Structure and organization of PERV LTRs.

The structure and organization of PERV LTRs are identical to those of other type C retroviruses, containing U3, R, and U5 regions (Fig. 1). Among the investigated PERV LTRs, the greatest homologies are found in R and U5. These are identical in 293-PERV-A(42), 293-PERV-B(33), and 293-PERV-B(43). The LTR of PK15-PERV-A(58) differs by 2 nucleotides (nt) in R and by 9 nt in U5 compared to that of 293-PERV-B(33), while the PERV-C LTR shows 1 nt difference in R and 18 nt differences in U5. The R and U5 regions of the 293-PERV-B(33) LTR are 76 and 55% homologous to those of typical mammalian type C retroviruses, as established by appropriate sequence alignments (5). In U3, only the extreme 5′ (nt 1 to 6) and 3′ (nt 538 to 544) ends of 293-PERV-B(33) show homologies to LTR sequences highly conserved among mammalian type C retroviruses (5, 12); a TATA box exists, while a CCAAT box could not be identified. The LTRs of 293-PERV-B(33) (total length, 707 bp) (7), 293-PERV-A(42) (668 bp) (7, 14), and 293-PERV-B(43) (629 bp) (7) contain four, three, and two copies of a 39-bp repeat, respectively; otherwise, they are identical (Fig. 1). The repeat comprises an 18-bp subrepeat located upstream of a 21-bp subrepeat. An additional 18-bp subrepeat is located downstream of the 39-bp repeat box. The LTR of PK15-PERV-A(58) (702 bp) (14) contains motifs homologous to the 18-bp repeat (2 nt differences; nt 462 to 480) and to the 21-bp subrepeat (2 nt differences; nt 417 to 437) but separated from each other in U3. The U3 region of the PERV-C LTR (595 bp) harbors sequences resembling those repeats with an 18-bp subrepeat (nt 98 to 118) and a 21-bp subrepeat (nt 383 to 403) (Fig. 1). Comparison of the LTR of 293-PERV-B(33) with those of PK15-PERV-A(58) and PERV-C shows homologies of 68 and 61%, respectively. The proviral PERV-C LTR displays close (97%) homology to the PERV-MSL sequence (1) for a segment including the 3′ end of U3, R, and U5, whereas the upstream part of the U3 region is different.

Serial passaging of molecular PERV-B clones.

PERV molecular clones 293-PERV-B(33)/ATG and 293-PERV-B(43) (7) were transfected into cell line 293, and the viruses produced thereafter were serially passaged. Both viruses displayed a steep increase in RT activity in the first 2 weeks of each passage and the development of a plateau in week 4. With regard to the complete course, 293-PERV-B(33)/ATG showed maximum RT activity (400 mU/ml) during the first two passages whereas 293-PERV-B(43) yielded almost unchanged activities of up to 550 mU/ml (data not shown).

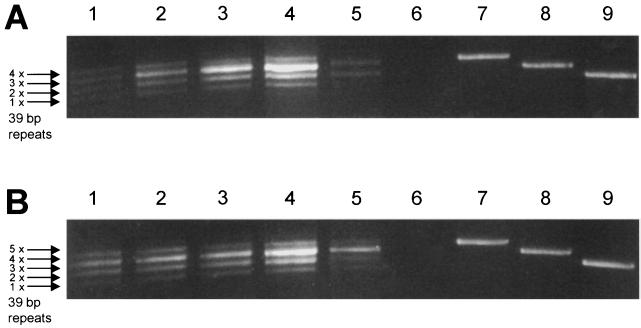

Proviral LTRs were amplified by PCR using genomic DNA at the end of each passage (week 4). The amplification products revealed multiple bands for both clones at each time point. PCR products represented LTRs which differed in length (Fig. 2A and B) because they had different numbers of 39-bp repeats, as revealed by sequence analysis. The LTR of molecular clone 293-PERV-B(33)/ATG contains four 39-bp repeats (Fig. 1 and 2A, lane 7). The multiple bands (Fig. 2A, lane 1) demonstrating products corresponding to the original proviral LTR, to the LTR of 293-PERV-A(42) (three 39-bp repeats; Fig. 1 and 2A, lane 8), and to the LTR of 293-PERV-B(43) (two 39-bp repeats; Fig. 1 and 2A, lane 9). Furthermore, an LTR representing one 39-bp repeat (total length, 590 bp) was detected in lower abundance (Fig. 1). From the second passage on, smaller LTRs corresponding to the 293-PERV-A(42) and 293-PERV-B(43) LTRs were detectable in larger amounts while the other LTRs still existed in smaller amounts (Fig. 2A, lanes 2 to 5).

FIG. 2.

PCR of PERV LTR DNA sequences originating from molecular virus clones 293-PERV-B(33)/ATG (A) and 293-PERV-B(43) (B) upon passaging in 293 cells. Multiple LTR bands are denoted (arrows). Lanes: 1, virus passage 1 (4 weeks postinfection [p.i.]); 2, virus passage 2 (8 weeks p.i.); 3, virus passage 3 (12 weeks p.i.); 4, virus passage 4 (16 weeks p.i.); 5, virus passage 10 (40 weeks p.i.); 6, negative control (water); 7 to 9, LTR PCR amplification products derived from plasmids pPERV-B(33), pPERV-A(42), and pPERV-B(43) (7), respectively.

The molecular clone 293-PERV-B(43) revealed a very similar pattern of LTR distribution during serial passaging (Fig. 2B, lanes 1 to 5). Descendants of that clone comprised an additional provirus that bears a previously unknown LTR containing five 39-bp repeats (total length, 746 bp) (Fig. 1), which was barely detectable after the first passage (Fig. 2B, lane 1).

Promoter activity of PERV LTRs.

The Dual-Luciferase Reporter Assay System was used to investigate the activities of different PERV LTRs. Native and deletion-containing LTRs were investigated, and an RSV LTR and an SV40 promoter were used as controls. In all of the human (A3.01, 293, HeLa, and MRC-5), simian (Cos-7), canine (D17), feline (PG-4), and porcine (PK 15 and ST-Iowa) cell lines tested, PERV LTRs demonstrated significant promoter activities (Fig. 3; Table 1).

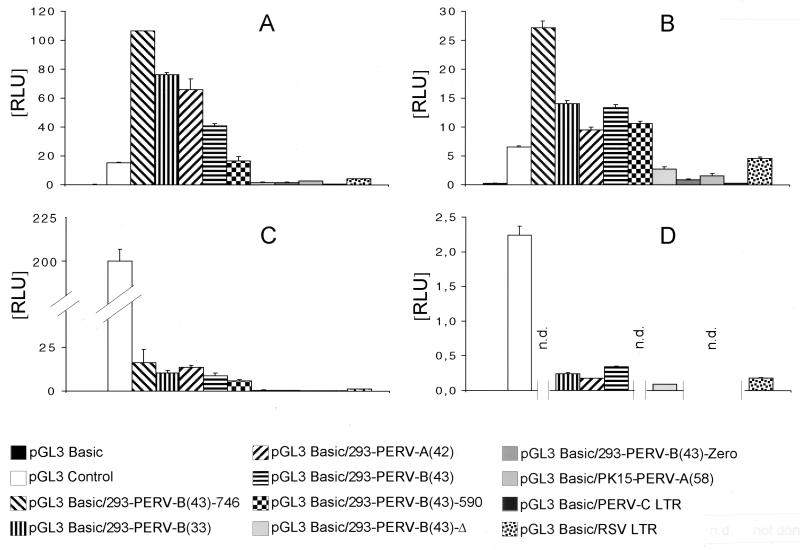

FIG. 3.

Activities of PERV LTRs cloned into luciferase reporter gene vector pGL3 Basic and of control vectors with respect to that of the internal control, pRL-CMV. (A) 293 cells; (B) A3.01 cells; (C) HeLa cells; (D) MRC-5 cells. n.d., not done. RLU, relative light units.

TABLE 1.

Activities of control vectors and retroviral LTRs cloned into luciferase reporter gene vector pGL3 Basic, with respect to that of internal control pRL-CMV, in nonhuman mammalian cells

| Vector | Mean no. of RLUa ± SD in cell line:

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Simian Cos-7 | Canine D-17 | Feline PK15 | Porcine ST-Iowa | Porcine PK15 | |

| pGL3 Basic | 0.02 ± 0.00 | 0.08 ± 0.00 | 0.05 ± 0.00 | 0.21 ± 0.02 | 0.07 ± 0.00 |

| pGL3 Control | 63.49 ± 11.91 | 9.04 ± 0.46 | 22.12 ± 0.22 | 177.59 ± 2.34 | 51.69 ± 1.94 |

| PERV-B(43)-746 | NDb | ND | 74.53 ± 9.77 | 47.59 ± 5.67 | 58.70 ± 0.10 |

| PERV-B(33) | 23.82 ± 0.60 | 9.37 ± 0.10 | 19.58 ± 0.26 | 31.14 ± 1.07 | 27.44 ± 0.00 |

| PERV-A(42) | 17.63 ± 0.26 | 10.62 ± 0.22 | 24.68 ± 1.46 | 29.01 ± 1.02 | 27.33 ± 0.93 |

| PERV-B(43) | 11.98 ± 0.61 | 9.45 ± 0.23 | 17.12 ± 0.60 | 48.45 ± 1.37 | 27.85 ± 3.64 |

| PERV-B(43)-Δ | 0.14 ± 0.01 | 0.55 ± 0.03 | ND | ND | ND |

| PERV-B(43)-Zero | ND | ND | 32.34 ± 2.29 | 39.25 ± 4.75 | 21.66 ± 0.84 |

| PERV-A(58) | ND | ND | 0.85 ± 0.01 | 2.47 ± 0.15 | 1.28 ± 0.06 |

| RSV | 1.94 ± 0.16 | 0.40 ± 0.02 | ND | ND | ND |

Luciferase activity relative to that of internal standard pRL-CMV is shown.

ND, not done.

In human cell lines 293, A3.01, and HeLa, the activities of PERV LTRs containing the 39-bp repeat, i.e., 293-PERV-B(43)-746, 293-PERV-B(33), 293-PERV-A(42), 293-PERV-B(43), and 293-PERV-B(43)-590, were higher than the activities of the RSV LTR [up to 25-fold and 7-fold in 293 and A3.01 cells in the case of 293-PERV-B(43)-746, respectively; Fig. 3A to C]. In 293 and A3.01 cells, those PERV LTRs displayed activities even higher than that of the SV40 promoter (Fig. 3A and B). In contrast, native LTRs lacking the 39-bp repeat, PK15-PERV-A(58) and PERV-C, showed promoter activities that were clearly reduced compared to that of the RSV LTR. In MRC-5 cells, PERV LTRs showed moderate activity similar to that of the RSV LTR (Fig. 3D). In all of the human cell lines, the activities of the LTR deletion mutants 293-PERV-B(43)-Δ and 293-PERV-B(43)-Zero were clearly reduced compared to that of the parental LTR. Reduction was up to 67-fold for 293-PERV-B(43)-Δ compared with the 293-PERV-B(43)-746 LTR in 293 cells and 33-fold for 293-PERV-B(43)-Zero compared with the 293-PERV-B(43)-746 LTR in HeLa cells (Fig. 3A and C). In Cos-7 and D17 cells, the activities of LTRs resembled those in human cells (Table 1). Native PERV LTRs, in contrast to the mutant 293-PERV-B(43)-Δ LTR, showed activities clearly higher than that of the RSV LTR. The SV40 promoter showed stronger activity than PERV LTRs in Cos-7 cells, whereas in D17 cells, the activities of PERV LTRs were almost equal to that of the SV40 promoter (Table 1).

In contrast to these results, in feline (PG-4) and porcine cells (ST-Iowa and PK 15), the deletion mutant 293-PERV-B(43)-Zero showed strong activity, reaching levels similar to those of the native LTRs, except for the 293-PERV-B(43)-746 LTR, which demonstrated the highest activity in these cell lines (Table 1). In contrast, the PK15-PERV-A(58) LTR, naturally lacking the 39-bp repeat, showed weak activity compared to those of the other PERV LTRs.

Modulation of heterologous and homologous promoter activities.

The repeat box (four 39-bp repeats plus an additional 18-bp subrepeat) of the 293-PERV-B(33) LTR was cloned into the luciferase vector pGL3 Control upstream and downstream of the heterologous SV40 promoter and the gene for luciferase in both orientations to evaluate possible enhancer properties of the sequence motif.

In human 293 and A3.01 cells, these vector constructs showed markedly increased promoter activity compared to that of the unmodified vector, independently of the location and orientation of the repeat box (Fig. 4A and B). The strongest activation of the SV40 promoter was found for the upstream forward construct, resulting in 5.4-fold-increased activity in 293 cells and 14.7-fold-increased activity in A3.01 cells. The weakest activation was observed for the downstream forward construct in A3.01 cells and the downstream reverse construct in 293 cells. In HeLa cells, only the upstream constructs elevated the activity 1.6-fold in the forward orientation and 1.9-fold in the reverse orientation. Reduced activities were observed when the repeat box was cloned downstream of the SV40 promoter (0.8-fold in the forward orientation and 0.4-fold in the reverse orientation) (Fig. 4C). In MRC-5 cells, only a moderate increase in promoter activity was detectable for the downstream forward construct (1.2-fold) and the downstream reverse construct (1.1-fold), respectively (Fig. 4D).

Further luciferase vectors contained the four 39-bp repeats cloned upstream and downstream of the 293-PERV-B(43)-Zero LTR in both orientations. In 293, A3.01, and HeLa cells, the repeat box mediated an increase in 293-PERV-B(43)-Zero LTR activity independently of location and orientation, yielding a uniform pattern for all of the cell lines tested (Fig. 5). The strongest activation was found for the downstream reverse vector, while the lowest level of activation was found for the upstream forward construct. In 293 cells, the maximum activation of the homologous promoter was stronger than that of the heterologous SV40 promoter, while in A3.01 cells, the opposite pattern was found (Fig. 4A and B and 5A and B). In HeLa cells, the activation by the repeat box was almost the same for both the homologous and heterologous promoters (Fig. 4C and 5C).

When the four 39-bp repeats were inserted directly upstream of the promoterless luciferase-encoding gene in both orientations, weak promoter activity, compared to that of the PERV LTRs, was observed (data not shown).

DISCUSSION

In this investigation, we have studied the transcriptional activity of a variety of LTRs derived from PERV-A and PERV-B molecular clones that are replication competent in human cells. A 39-bp repeat box in U3 was identified which multimerizes dynamically upon replication and acts as a viral enhancer.

The number of 39-bp repeats in PERV LTRs fluctuates upon serial virus passaging.

Except for LTRs of PK15-PERV-A(58) and PERV-C, the native LTRs studied here differ only in the number of 39-bp repeats, consisting of 18- and 21-bp subrepeats, located in U3 (Fig. 1). The existence of repeat elements in viral promoters is well known (10); repeats have been described for retroviruses such as Moloney murine leukemia virus (31), human T-cell leukemia virus types I and II (24, 27), and Mus dunni endogenous retrovirus (35).

Serial passages of PERV-B clones in human 293 cells revealed adaptation to the new host on the transcriptional level. Virus clones 293-PERV-B(33)/ATG and 293-PERV-B(43), bearing four and two 39-bp repeats, respectively, yielded proviral LTRs that showed reduced or multiplied numbers of 39-bp repeats (Fig. 2A and B). The multimerization of specific U3 elements in PERV LTRs and their arrangement as repeats do not necessarily originate from virus passaging on human cells, since analysis of PERV sequences in BAC clones derived from the porcine genome revealed that clone PERV-B (Bac-192B9) contains a complete PERV-B sequence whose LTR is very closely related to the LTR of 293-PERV-A(42) and thus bears the three 39-bp repeats in U3 (30; M. Niebert et al., unpublished data). In addition, PCR analysis of PK15 cellular DNA demonstrated the presence of LTRs bearing up to four 39-bp repeats (14).

However, the modulation of repeat numbers during serial passaging of PERV, indeed, reflects adaptation to the new host, as late passages appear to yield one or two types of LTRs in majority, possibly representing the optimal number of 39-bp repeats for PERV replication in vivo (Fig. 2A and B, lanes 5). Although LTRs bearing a large number of 39-bp repeats showed increased activity in transient-transfection assays (Fig. 3; Table 1), those expanded LTRs might be disadvantageous for viral replication upon serial passaging, as negative selection, for example, by interference with viral RNA packaging, may occur (20).

The mechanism of repeat multimerization is unknown. In contrast to the hypothesis which suggests the slippage of RT, as described for SL3 (20), we suppose that the mechanism causing repeat multimerization in PERV is similar to that described for Mus dunni endogenous retrovirus (35). This hypothesis suggests a homologous misannealing during reverse transcription which requires the availability of other short repeat sequences flanking the repeat region, a pattern which, indeed, is found for PERV where an additional 18-bp subrepeat is located downstream of the 39-bp repeat box (Fig. 1). In fact, the multimerization or reduction of PERV U3 repeats generating a panel of different proviral LTRs already occurred during the first 4 weeks of virus passaging (Fig. 2A and B, lanes 1), revealing no mutation in the repeat sequence.

The number of 39-bp repeats in PERV LTRs modulates promoter activity.

According to the different activities of PERV LTRs in human and mammalian cell lines (Fig. 3; Table 1), we suggest that PERV LTR expansion is caused by enhancer multimerization.

We have demonstrated that PERV LTRs containing up to five copies of a 39-bp repeat (Fig. 1) showed strong promoter activity in human and mammalian cell lines, while the activity of LTRs devoid of the repeat was clearly decreased (Fig. 3; Table 1). The remaining activity of deletion-containing LTR constructs might result in a basal activity of the enhancerless promoter. Furthermore, the existence of additional enhancer elements located outside the repeats, as described for Moloney murine sarcoma virus (16), is conceivable.

With regard to the activities of different viral promoters in lymphoid T-cell lines (37), we conclude that the 293-PERV-B(43)-746 LTR, showing stronger activity than the RSV LTR in human lymphoid A3.01 T cells, might be a useful tool for gene transfer applications that depend on the level of expression.

The 293-PERV-B(43)-Zero LTR, however, showed strong activities in porcine and feline cells (Table 1). Obviously, in those cell lines, the promoter activity is not influenced by the repeat unless the threshold of four 39-bp repeats is exceeded, since the 293-PERV-B(43)-746 LTR (five 39-bp repeats) demonstrated significantly stronger activity. As porcine cells harbor endogenous PERV-LTRs, this effect could be due to competition for specific transcription factors. Alternatively, the threshold effect might be due to the existence of negative regulatory elements located outside of the enhancer sequence, as shown for murine leukemia virus (4).

Different LTR activities cause different cell tropisms.

The cell-specific activity of viral LTRs is responsible for viral cell tropism, as described for Jaagsiekte sheep retrovirus (23) and RSV (26). PERV-A and PERV-B released from pig cells infect human cells in vitro (19, 25, 33, 34), and molecular PERV-A and PERV-B clones are replication competent in 293, HeLa, and D17 cells (7, 14) and at lower levels in A3.01 cells (data not shown). PERV LTRs show strong activity in those cell lines, which is a prerequisite for productive infection in conjunction with the existence of PERV-specific receptors. In contrast, MRC-5 cells could not be infected with PERV (data not shown), which is consistent with the weak activity of PERV LTRs and the low susceptibility of these cells to pseudotyped murine leukemia virus (29). Conversely, Cos-7 cells demonstrated strong promoter activity for PERV; however, these cells lack PERV-specific receptors (29). Furthermore, feline PG-4 cells show strong replication rates for PERV-A (14), although the 293-PERV-A(42) LTR did not demonstrate activity higher than those of the other PERV LTRs.

The U3 repeat box acts as an enhancer.

As the repeatless 293-PERV-B(43)-Δ and 293-PERV-B(43)-Zero LTRs showed clearly decreased promoter activity in human cells compared to those of LTRs bearing the 39-bp repeat (Fig. 1 and 3), we supposed that the repeat comprises enhancer elements. A preliminary statistical transcription factor analysis revealed putative binding sites for nucleus factor Y in the 39-bp sequence (data not shown). The functional role of such repeats as enhancers is a common feature (10). For example, in the RSV LTR, deletion of enhancer elements led to a 94% reduction from the original promoter activity (6). In our studies, the four 39-bp repeats, indeed, mediated increased SV40 promoter activity independently of its orientation and location over a distance of 2,200 bp in the case of the downstream constructs in human 293 and A3.01 cells (Fig. 4A and B). Thus, the 39-bp repeat bears known properties of classical enhancers (2, 13). In contrast, in HeLa cells, only weak activation of the SV40 promoter was found for both upstream constructs (Fig. 4C). These results may be due to the fact that the SV40 promoter itself showed extremely strong activity in HeLa cells that was caused by the major role of transcription factor Sp1, which triggers SV40 promoter activity (8), possibly not allowing significant modulation. In MRC-5 cells, all of the PERV LTRs tested showed weak activity (Fig. 3D). Likewise, the 39-bp repeat box did not activate the heterologous SV40 promoter (Fig. 4D).

The influence of the 39-bp repeat box on a homologous repeat-free LTR, i.e., 293-PERV-B(43)-Zero, was further studied to substantiate the enhancer hypothesis. The promoter constructs correspond to the 293-PERV-B(33) LTR but bear a dislocated 39-bp repeat box (Fig. 1 and 5). In all of the cell lines tested, the dislocated repeat box increased the activity of the deletion mutant, irrespectively of location and orientation, which is additional proof of the enhancer properties of the repeat box (Fig. 5). According to these results, the orientation and location of the repeat box in the LTRs are important for promoter activity and the different levels of activation reflect spacing effects, possibly leading to enhancer silencing (3).

The 39-bp repeat box itself, cloned in the promoterless luciferase vector pGL3 Basic upstream of the gene for luciferase in both orientations, revealed weak promoter activity (data not shown). Weak transcriptional initiation in the absence of a promoter is a typical feature of enhancer elements (17) and has been described, e.g., for the SV40 72-bp enhancer repeat (22, 32).

Possible consequences of PERV integration into the human genome.

The activity of PERV LTRs specifically correlates with the presence of a 39-bp repeat box in U3 which represents a viral enhancer that activates heterologous, as well as homologous, promoters independently of orientation and location.

Specific questions about the safety of porcine xenografts arise from these results. As proviral DNA integrates itself into the host genome, replicating PERV may elicit pathogenic effects mediated by the LTRs, as described for exogenous retroviruses (11, 13), endogenous retroviruses (18), and transposons in general (36). In the case of xenotransplantation, the recipient would be immunosuppressed to avoid rejection of the donor organ. As no steroid hormone-responsive element or NF-κB sites could be identified in the PERV LTRs, it remains to be shown whether immunosuppressive drugs such as prednisolone and cyclosporine have direct or indirect effects on LTR activities which might add to the safety concerns about PERV.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This study was supported by a grant from the German Ministry of Health (Bundesministerium für Gesundheit), Bonn, Germany.

We thank Egbert Flory for support regarding promoter assays and Peter Volkers for consultation about statistical analysis. The technical assistance of Gundula Braun is gratefully acknowledged.

REFERENCES

- 1.Akiyoshi D E, Denaro M, Zhu H, Greeenstein J L, Banerjee P T, Fishman J A. Identification of full-length cDNA for an endogenous retrovirus of miniature swine. J Virol. 1998;72:4503–4507. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.5.4503-4507.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Blackwood E M, Kadonaga J. Going the distance: a current view of enhancer action. Science. 1998;281:60–63. doi: 10.1126/science.281.5373.60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bonifer C. Developmental regulation of eukaryotic gene loci—which cis-regulatory information is required? Trends Genet. 2000;16:310–315. doi: 10.1016/s0168-9525(00)02029-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ch'ang L-Y, Yang W K, Myer F E, Yang D-M. Negative regulatory element associated with potentially functional promoter and enhancer elements in the long terminal repeats of endogenous murine leukemia virus-related proviral sequences. J Virol. 1989;63:2746–2757. doi: 10.1128/jvi.63.6.2746-2757.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chen H R, Baker W C. Nucleotide sequences of the retroviral long terminal repeats and their adjacent regions. Nucleic Acids Res. 1984;12:1767–1778. doi: 10.1093/nar/12.4.1767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cullen B R, Raymond K, Ju G. Functional analysis of the transcription control region located within the avian retroviral long terminal repeat. Mol Cell Biol. 1985;5:438–447. doi: 10.1128/mcb.5.3.438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Czauderna F, Fischer N, Boller K, Kurth R, Tönjes R R. Establishment and characterization of molecular clones of porcine endogenous retroviruses replicating on human cells. J Virol. 2000;74:4028–4038. doi: 10.1128/jvi.74.9.4028-4038.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dynan W S, Tjian R. The promoter-specific transcription factor Sp1 binds to upstream sequences in the SV40 early promoter. Cell. 1983;35:79–87. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(83)90210-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ehlers B, Ulrich S, Golz M. Detection of two novel porcine herpesviruses with high similarity to gammaherpesviruses. J Gen Virol. 1999;80:971–978. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-80-4-971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fan H. Influences of the long terminal repeats on retrovirus pathogenicity. Semin Virol. 1990;1:165–174. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fishman J A. Xenosis and xenotransplantation: addressing the infectious risks posed by an emerging technology. Kidney Int. 1997;51(Suppl. 58):41–45. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Golemis E A, Speck N A, Hopkins N. Alignment of U3 region sequences of mammalian type C viruses: identification of highly conserved motifs and implications for enhancer design. J Virol. 1990;64:534–542. doi: 10.1128/jvi.64.2.534-542.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Khoury G, Gruss P. Enhancer elements. Cell. 1983;33:313–314. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(83)90410-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Krach U, Fischer N, Czauderna F, Tönjes R R. Comparison of replication-competent molecular clones of porcine endogenous retrovirus class A and class B derived from pig and human cells. J Virol. 2001;75:5465–5472. doi: 10.1128/JVI.75.12.5465-5472.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Krach U, Fischer N, Czauderna F, Kurth R, Tönjes R R. Generation and testing of highly specific anti-serum directed against porcine endogenous retrovirus nucleocapsid. Xenotransplantation. 2000;7:221–229. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-3089.2000.00070.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Laimins L A, Gruss P, Pozzatti R, Khoury G. Characterization of enhancer elements in the long terminal repeat of Moloney murine sarcoma virus. J Virol. 1984;49:183–189. doi: 10.1128/jvi.49.1.183-189.1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lang J C, Spandidos D A. The structure and function of eukaryotic enhancer elements and their role in oncogenesis. Anticancer Res. 1986;6:437–450. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Löwer R. The pathogenic potential of endogenous retroviruses: facts and fantasies. Trends Microbiol. 1999;7:350–356. doi: 10.1016/s0966-842x(99)01565-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Martin U, Kiessig V, Blusch J H, Haverich A, von der Helm K, Herden T, Steinhoff G. Expression of pig endogenous retrovirus by primary porcine endothelial cells and infection of human cells. Lancet. 1998;352:692–694. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(98)07144-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Martiney M J, Rulli K, Beaty R, Levy L S, Lenz J. Selection of reversion and suppressors of a mutation in the CBF binding site of a lymphomagenic retrovirus. J Virol. 1999;73:7599–7606. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.9.7599-7606.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Michaels M G, Simmons R L. Xenotransplant-associated zoonoses. Transplantation. 1994;57:1–7. doi: 10.1097/00007890-199401000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Moreau P, Hen R, Wasylyk B, Everett R, Gaub M P, Chambon P. The SV40 72 base pair repeat has a striking effect on gene expression both in SV40 and other chimeric recombinants. Nucleic Acids Res. 1981;9:6047–6068. doi: 10.1093/nar/9.22.6047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Palmarini M, Datta S, Omid R, Murgia C, Fan H. The long terminal repeat of Jaagsiekte sheep retrovirus is preferentially active in differentiated epithelial cells of the lungs. J Virol. 2000;74:5776–5787. doi: 10.1128/jvi.74.13.5776-5787.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Paskalis H, Felber B K, Pavlakis G N. Cis-acting sequences responsible for the transcriptional activation of the human T-cell leukemia virus type I constitute a conditional enhancer. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1986;83:6558–6562. doi: 10.1073/pnas.83.17.6558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Patience C, Takeuchi Y, Weiss R A. Infection of human cells by an endogenous retrovirus of pigs. Nat Med. 1997;3:282–286. doi: 10.1038/nm0397-282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ruddell A. Transcription regulatory elements of the avian retroviral long terminal repeat. Virology. 1995;206:1–7. doi: 10.1016/s0042-6822(95)80013-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shimotohno K, Golde D W, Miwa M, Sugimura T, Chen I S Y. Nucleotide sequence analysis of the long terminal repeat of human T-cell leukemia virus type II. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1984;81:1079–1083. doi: 10.1073/pnas.81.4.1079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Stoye J P, Coffin J M. The danger of xenotransplantation. Nat Med. 1995;1:1100. doi: 10.1038/nm1195-1100a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Takeuchi Y, Patience C, Magre S, Weiss R A, Banerjee P T, Le Tissier P, Stoye J P. Host range and interference studies of three classes of pig endogenous retrovirus. J Virol. 1998;72:9986–9991. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.12.9986-9991.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tönjes R R, Czauderna F, Fischer N, Krach U, Boller K, Chardon P, Rogel-Gaillard C, Niebert M, Scheef G, Werner A, Kurth R. Molecularly cloned porcine endogenous retroviruses replicate on human cells. Transplant Proc. 2000;32:1158–1161. doi: 10.1016/s0041-1345(00)01165-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.van Beveren C, Rands E, Chattopadhyay S K, Lowy D R, Verma I M. Long terminal repeat of murine retroviral DNAs: sequence analysis, host-proviral junctions, and preintegration site. J Virol. 1982;41:542–556. doi: 10.1128/jvi.41.2.542-556.1982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wasylyk B, Wasylyk C, Augereu P, Chambon P. The SV40 72 bp repeat preferentially potentiates transcription starting from proximal natural or substitute promoter elements. Cell. 1983;32:503–514. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(83)90470-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wilson C A, Wong S, van Brocklin M, Federspiel M J. Extended analysis of the in vitro tropism of porcine endogenous retrovirus. J Virol. 2000;74:49–56. doi: 10.1128/jvi.74.1.49-56.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wilson C A, Wong S, Muller J, Davidson C E, Rose T M, Burd P. Type C retrovirus released from porcine primary peripheral blood mononuclear cells infects human cells. J Virol. 1998;72:3082–3087. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.4.3082-3087.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wolgamot G, Miller A D. Replication of Mus dunni endogenous retrovirus depends on promoter activation followed by enhancer multimerization. J Virol. 1999;73:9803–9809. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.12.9803-9809.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yoder J A, Walsh C P, Bestor T H. Cytosine methylation and the ecology of intragenomic parasites. Trends Genet. 1997;13:335–340. doi: 10.1016/s0168-9525(97)01181-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zarrin A A, Malkin L, Fong I, Duke K D, Ghose A, Berinstein N L. Comparison of CMV, RSV, SV40 viral and Vλ1 cellular promoters in B and T lymphoid and non-lymphoid cell lines. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1999;1446:135–139. doi: 10.1016/s0167-4781(99)00067-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]